Abstract

Daily ambulatory activity is associated with health and functional status in older adults; however, assessment requires multiple days of activity monitoring. The objective of this study was to determine the relative capabilities of self-selected walking speed (SSWS), maximal walking speed (MWS), and walking speed reserve (WSR) to provide insight into daily ambulatory activity (steps per day) in community-dwelling older adults. Sixty-seven older adults completed testing and activity monitoring (age 80.39(6.73) years). SSWS (R2 = 0.51), MWS (R2 = 0.35), and WSR calculated as a ratio (R2 = 0.06) were significant predictors of daily ambulatory activity in unadjusted linear regression. Cutpoints for participants achieving <8,000 steps/day were identified for SSWS (≤0.97 m/s, 44.2% sensitivity, 95.7% specificity, 10.28 +LR, 0.58 −LR) and MWS (≤1.39 m/s, 60.5% sensitivity, 78.3% specificity, 2.79 +LR, 0.50 −LR). SSWS may be a feasible proxy for assessing and monitoring daily ambulatory activity in older adults.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical measures that identify older adults who would benefit from increased daily ambulatory activity are needed, as daily ambulatory activity is associated with health and functional status (de Melo, Menec, & Ready, 2014; Ewald, Attia, & McElduff, 2014; Lee et al., 2013; Mosallanezhad, Salavati, Sotoudeh, Nilsson Wikmar, & Frandin, 2014; Petrella & Cress, 2004). Daily ambulatory activity can be quantified as steps per day. Higher average steps per day is associated with decreased cardiovascular and metabolic disease risk factors, improved hip bone mineral density, and better psychosocial health in older adults (Ewald et al., 2014; Ewald, McEvoy, & Attia, 2010; Foley, Quinn, & Jones, 2010; Newton et al., 2013; Park et al., 2008; Sisson et al., 2010; Tudor-Locke et al., 2008; Vallance, Eurich, Lavallee, & Johnson, 2013). Both normative data and daily step count recommendations are available in the literature, allowing clinicians and researchers to determine if an individual is meeting age norms and/or recommended thresholds to achieve health benefits (Ewald et al., 2014; Tudor-Locke et al., 2011; Tudor-Locke et al., 2013). Although recommendations on steps per day varies for older adults, achieving an average of 8,000 steps per day is associated with reduced risk of metabolic syndrome and is above the threshold for receiving at least 80% of the benefit steps per day confers on BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, insulin sensitivity, HDL levels, white cell count, and fibrinogen levels in this population (Ewald et al., 2014; Park et al., 2008). Additionally, 8,000 steps has been recommended as a goal for older adults on days they are attempting to achieve 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (Tudor-Locke et al., 2011).

Measurement of steps per day requires activity monitoring via a pedometer or accelerometer. The device must be worn for several days in order to get an accurate reflection of average ambulatory behavior. In previous studies on older adults, activity monitoring has ranged in length from four to eight days, with the majority monitoring for seven days (Boyer, Andriacchi, & Beaupre, 2012; Brach, VanSwearingen, Newman, & Kriska, 2002; Garcia-Ortiz et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2013; Schimpl et al., 2011; Wanner, Martin, Meier, Probst-Hensch, & Kriemler, 2013). The utility of activity monitoring is limited by the time required. However, it is plausible that a more efficient measure may provide insight. An individual’s performance on clinical measures of gait and mobility may be indicative of their daily ambulatory activity.

A reliable, responsive measure of gait and mobility is walking speed (WS) (Goldberg & Schepens, 2011; Peters, Fritz, & Krotish, 2013). Due to the wealth of information the measure provides and the ease of administration (i.e. minimal space, time, and equipment requirements), WS has earned recognition as the “sixth vital sign” and is recommended in comprehensive geriatric assessment (Fritz & Lusardi, 2009; Middleton, Fritz, & Lusardi, 2014; Peel, Kuys, & Klein, 2013). Walking speed can be measured at either an individual’s self-selected (SSWS) or maximal (MWS) walking speed and is appropriate for use with a wide range of populations, including older adults (Bowden, Balasubramanian, Behrman, & Kautz, 2008; Cesari et al., 2005; Paltamaa, Sarasoja, Leskinen, Wikstrom, & Malkia, 2008; Quinn et al., 2013; Ries, Echternach, Nof, & Gagnon Blodgett, 2009; Williams, Schache, & Morris, 2013). SSWS provides insight into an older adult’s current and future health and function (Elbaz et al., 2013; Rosano, Newman, Katz, Hirsch, & Kuller, 2008; Shimada et al., 2013), and is associated with risk of adverse outcomes such as fracture, stroke, dementia, hospitalization and institutionalization, and mortality (Cesari et al., 2005; Cooper et al., 2011; Elbaz et al., 2013). Whether SSWS provides insight into daily ambulatory activity (steps per day) in this population has not been determined. The measure shows promise, though, as it is predictive of ambulatory activity in individuals with stroke (Bowden et al., 2008; Perry, Garrett, Gronley, & Mulroy, 1995) and incomplete spinal cord injury (Stevens, Fuller, & Morgan, 2013). Maximal WS may also be reflective of daily ambulatory activity in older adults, as MWS is associated with physical health status and level of physical activity in this population (Sallinen et al., 2011; Sartor-Glittenberg et al., 2013).

Although WS provides insight into health and functional status, meeting steps per day guidelines is how one can maintain or improve health and functional status (Fox et al., 2015; Tudor-Locke et al., 2011). Individuals not meeting recommended daily step counts may benefit from increased ambulatory activity. The gold standard for assessing daily ambulatory activity is activity monitoring. However, in order to get an accurate reflection of average ambulatory activity, multiple days of monitoring are required. At screening events, when goal-setting in clinical practice, or when an individual is self-assessing, waiting multiple days for results is not always practical. Reliable, responsive, easily administered measures that provide insight into daily ambulatory activity are needed. Walking speed meets these criteria and demonstrates potential in this capacity.

It is unknown whether an older adult’s SSWS or MWS is more predictive of their daily ambulatory activity, or whether a combination of these two values may be the most informative. SSWS and MWS can be combined to quantify an individual’s ability to adapt their WS. Adaptability of WS may be tied to outcomes, independent of the ones associated with SSWS or MWS, as changing speed is more challenging than maintaining steady-state WS (Peterson, Kautz, & Neptune, 2011). Termed “walking speed reserve” (WSR), this value can be calculated as either a difference (MWS – SSWS) or a ratio (MWS/SSWS).The primary objective of this study was to determine if SSWS, MWS, and WSR are significant predictors of daily ambulatory activity, quantified as steps per day, in community-dwelling older adults, and if so, which measure is the most informative. Findings from the primary objective were used to inform the secondary objective, which was to establish WS cutpoints that distinguish those meeting a steps per day threshold (8,000 steps) relevant to this population from those not meeting the threshold. The cutpoints established can be used to identify individuals who would benefit from increased daily ambulatory activity and to set objective, easily measurable WS goals.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study design was used to investigate the relationship between SSWS, MWS, and WSR and daily ambulatory activity in community-dwelling older adults. All study procedures were approved by the University of South Carolina’s Institutional Review Board, and all participants signed an approved informed consent form prior to participation. Data collection was performed by a single investigator, a physical therapist trained on the standardized procedures.

Participants

A convenience sample of community-dwelling older adults was recruited via flyer and word of mouth from local retirement communities and senior centers. To be eligible, participants had to be 65 years of age or older and able to complete the walking speed assessments. Individuals who presented with unresolved, but temporary musculoskeletal problems that affected ambulation (e.g. recent sprain or fracture); history of a neurologic condition (e.g. stroke, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease); or required a prosthetic device of any sort for ambulation were excluded. Results from a power analysis indicated that a sample size of 60 would provide 87% power to determine the relationship between SSWS and steps per day (α = 0.05) using linear regression (Bohannon, 2007; Cesari et al., 2005).

Questionnaires

Information regarding exercise frequency, fall history, and pain was collected from each participant. Participants self-reported exercise frequency by answering the following questions: “Do you exercise regularly? If yes, how often (times/week) and for how long (minutes/session)? What type of activities do you engage in?” To determine fall history, participants were asked: “Have you fallen in the last 12 months? A fall is an unplanned, unexpected contact with a supporting surface. If yes, please describe each fall.” Finally, pain was assessed by asking participants: “Do you currently have pain anywhere? If yes, where is your pain located? List all areas where you experience pain along with cause of pain, if known.”

Walking Speed

To determine SSWS and MWS, participants performed two trials of the 10 meter walk test under two different conditions (4 trials total) (Peters et al., 2013). For assessment of SSWS, participants were instructed to walk at their “usual, comfortable speed”. For MWS, the instructions were to walk as “quickly, but safely as possible, for example, as if you are hurrying to get somewhere.” The two trials under each condition were then averaged to determine SSWS and MWS (m/s), respectively. A stopwatch was used to time participants over the 10 meter path. Timing started when the participant’s lead leg broke the plane of the marker at the beginning of the path and stopped when their lead leg broke the plane of the marker at the end of the ten meter path. Five meters were provided prior to and following the timed portion to allow acceleration and deceleration to occur outside the timed region and ensure that steady-state self-selected and maximal WSs were captured for analyses (Graham, Ostir, Fisher, & Ottenbacher, 2008; Lindemann et al., 2008). Assistive devices and/or orthoses typically used during community ambulation were permitted during testing.

Daily Ambulatory Activity (Steps per Day)

To determine steps per day, participants wore an ActiGraph GT3X+ triaxial accelerometer on their right ankle for seven consecutive days, except during water-based activities (Korpan, Schafer, Wilson, & Webber, 2014). Ankle placement has been validated for collecting step count data in this population (Korpan et al., 2014). Participants were instructed to record time along with reasons the activity monitor was removed on an Activity Monitoring Log. To improve compliance, participants were contacted on Day 2 and Day 4 of activity monitoring to answer any questions and/or address any concerns. Participants were also encouraged to contact the investigator at any time during the seven days if questions arose. ActiLife 6.0 software was used to initialize the devices prior to distribution to participants and to download and process data once the devices were returned. Sampling frequency was set at 30Hz, and data was collected in 60 second epochs (Garcia-Ortiz et al., 2014). Sixty consecutive epochs with no activity counts was classified as non-wear time (Hart, Swartz, Cashin, & Strath, 2011). In order to be considered a “complete day”, at least 600 minutes of wear time had to be recorded (Barreira, Brouillette, Foil, Keller, & Tudor-Locke, 2013). Participants with less than 5 complete days of activity monitoring were excluded from data analysis (Hart et al., 2011).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables, and normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the level of association between each WS measure and steps per day. Linear regression analyses were performed to determine if SSWS, MWS, and/or WSR (diff and ratio) could be used as predictors of daily ambulatory activity (steps per day as continuous variable). Prior to performing regression, a between sex comparison (male versus female) of steps per day was performed. If steps per day differed between sexes, all regression analyses would be performed separately for males and females. Unadjusted models were constructed first, using each WS measure (SSWS, MWS, WSRdiff, or WSRratio) as the independent variable. Age-adjusted models were then constructed for each WS measure. Comparison of the amount of variability in steps per day (R2) explained by the regression models was used to identify which of the WS measures provided the greatest value (highest R2) as a predictor of daily ambulatory activity.

Logistic regression was used to determine if SSWS, MWS, WSRdiff, and/or WSRratio could be used to distinguish between those averaging <8,000 steps per day and those exceeding this threshold. Both unadjusted and adjusted analyses were performed. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed for the WS measures found to be significant predictors in logistic regression. ROC curves were also used to identify a cutpoint which maximized combined sensitivity and specificity for the included measure. Positive and negative likelihood ratios (+LR = sensitivity/(1 - specificity), -LR = (1 - sensitivity)/specificity) were calculated from the sensitivity and specificity at the selected cutpoint. The magnitude of the shifts in probability provided by positive and negative LRs indicate how useful the diagnostic measure is to clinicians. The following guidelines can be used to interpret LRs: +LRs >10 and -LRs <0.1 result in shifts in probability that are “large and conclusive”, +LRs between 5 and 10 and -LRs between 0.1 and 0.2 result in “moderate” shifts, +LRs from 2 to 5 and -LRs from 0.5 to 0.2 result in “small” shits, and +LRs from 1 to 2 and -LRs from 0.5 to 1 result in shifts that are “rarely important” (Jaeschke, Guyatt, & Sackett, 1994). LRs in isolation indicate the “magnitude” of the pre-test to post-test probability shift the cutpoint provides. LRs also have clinical applicability and can be used in combination with a Fagan’s nomogram to calculate actual post-test probabilities.

A straight-edge and Fagan’s nomogram were used to apply the +LR and -LR to the sample’s pre-test probability and calculate post-test probability (Fagan, 1975). To determine post-test probabilities from the nomogram, a straight edge is placed on the diagram as a line through the pre-test probability and the LR. The value corresponding to the point where the straight edge crosses the third vertical line on the diagram is the post-test probability. Post-test probabilities calculated with the nomogram were compared to post-test probabilities calculated using the DocNomo iPhone application (“DocNomo,” 2014) to ensure correct reporting of results. The DocNomo application is freely available to clinicians and offers an alternative to the paper and pencil nomogram. The shifts in probability from pre- to post-test for both positive (WS below identified cutpoint) and negative (WS above identified cutpoint) test results were calculated. The nomogram derived post-test probabilities allowed comparison of the actual shifts in probabilities that the WS cutpoints provided. All data analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS 22 and SAS® 9.3.

RESULTS

Participants

Sixty seven older adults meeting inclusion criteria enrolled in the study. Participants were recruited via flyer and word of mouth from four locations: three retirement communities and one senior center. Forty eight participants lived in a retirement community; 14 were members of the wellness facility at a retirement community, but did not live in a home or apartment associated with the site; and five were recruited through a senior center. One participant returned the activity monitor with only 4 days of wear time and was excluded from data analysis (n=66). Sixty three (95.5%) participants self-reported regular engagement in exercise, with the majority reporting either participation in group fitness classes 59.1% or walking 63.6% as the mode. Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Age (years) | 80.39 (6.7) |

| Female* | 49 (74.2) |

| Assistive Device* | |

| None | 59 (89.4) |

| Single Point Cane | 4 (6.0) |

| 4-Wheeled Rolling Walker | 3 (4.5) |

| Living in Retirement Community†* | 47 (71.2) |

| Number in household* | |

| Alone | 24 (36.4) |

| Spouse | 37 (56.1) |

| NR | 5 (7.8) |

| Exercise Regularly* | 63 (95.5) |

| Frequency (sessions/week) | 4.20 (1.7) |

| Duration (minutes/session) | 49.96 (25.3) |

| Report pain* | 29 (43.9) |

| Fall over previous year* | |

| No Fall | 52 (78.8) |

| 1 Fall | 10 (15.2) |

| >1 Fall | 4 (6.1) |

| Self-selected walking speed (SSWS, m/s) | 1.07 (0.23) |

| Maximal walking speed (MWS, m/s) | 1.41 (0.31) |

| Walking Speed Reserve | |

| Difference (MWS – SSWS, m/s) | 0.34 (0.16) |

| Ratio (MWS/SSWS) | 1.33 (0.17) |

| Days of Activity Monitoring (>10 hours) | 6.91 (0.34) |

| Average steps/day | 7261.16 (2903.95) |

Values are n (percentage); otherwise mean (SD) presented

Those not living in a retirement community lived in home/apartment in general community

Correlation

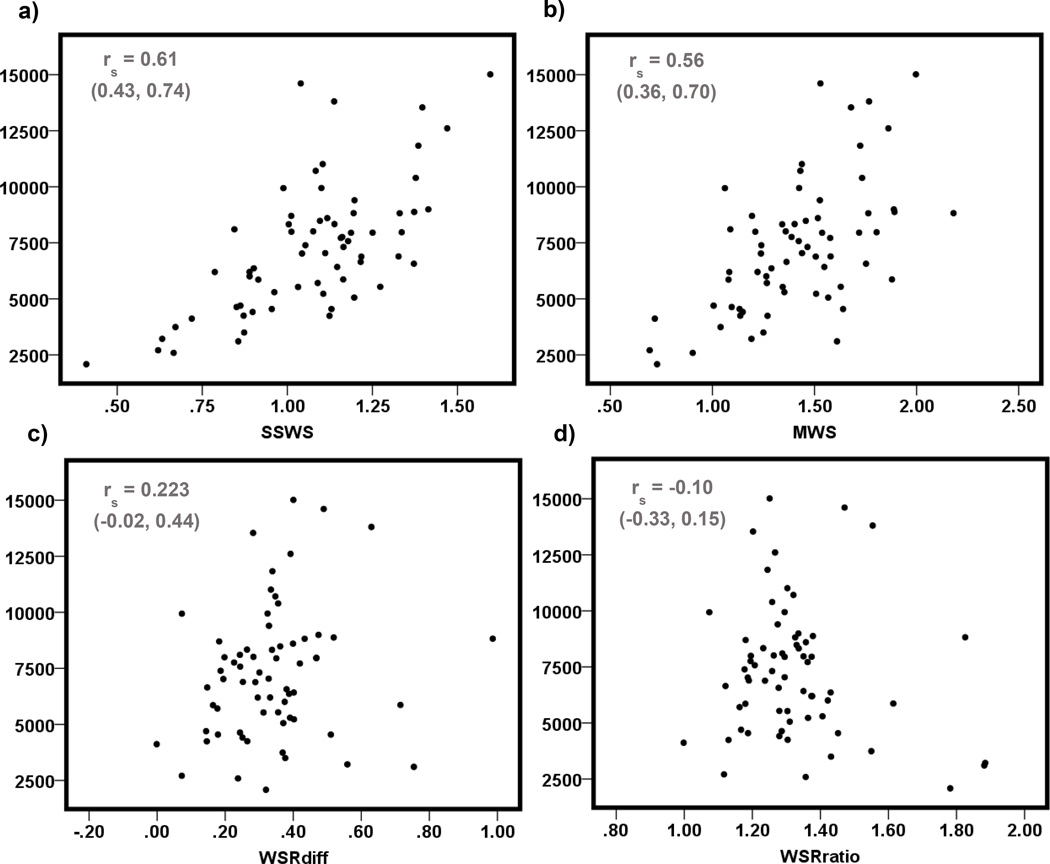

Scatter plots for steps per day and each WS measure (SSWS, MWS, WSRdiff, and WSRratio) are displayed in Figure 1. Neither WSR variable (difference and ratio) nor steps per day were normally distributed, so Spearman Rank Sum correlation coefficients were calculated for all analyses that included these variables.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots of steps per day (vertical axes) by a) self-selected walking speed (SSWS), b) maximal walking speed (MWS), c) walking speed reserve calculated as a difference (MWS – SSWS), d) walking speed reserve calculated as a ratio (MWS/SSWS)

Linear Regression

Steps per day did not vary between males and females (p = 0.10); therefore, sex was not accounted for in regression analysis (i.e. separate models were not constructed for males and females). SSWS, MWS, and WSRratio were all significant predictors of steps per day in the unadjusted models (Table 2). SSWS explained the greatest proportion of the variation in steps per day (51%), while the WSRratio model explained the least (6%). Residuals were not normally distributed for the unadjusted models predicting steps per day as a function of SSWS or WSRratio. To normalize residuals in the SSWS model, one outlier visually identified on a scatter plot of steps per day by SSWS was removed (14,608.86 steps per day and SSWS = 1.04 m/s), and steps per day were log transformed in order to normalize residuals for the WSRratio model.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Linear Regression Models for Steps per Day

| n |

p-value for F |

R2 | β | 95% CI for β | Standardized β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSWS* | 65 | <0.001 | 0.51 | 8703.80 | (6558.84, 10848.76) | 0.715 |

| MWS | 66 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 5554.00 | (3652.88, 7455.12) | 0.589 |

| WSRdiff | 66 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 3317.39 | (−1104.30, 7739.09) | 0.184 |

| WSRratio† | 66 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.54 | (0.30, 0.98) | 0.558 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SSWS, self-selected walking speed; MWS, maximal walking speed; WSRdiff, walking speed reserve calculated as a difference (MWS – SSWS); WSRratio, walking speed reserve calculated as a ratio (MWS/SSWS)

One outlier removed (14,608.86 steps per day and SSWS = 1.04 m/s) in order to normalize residuals for SSWS model

Steps per day log transformed in order to normalize residuals for WSRratio model

Age adjusted models were constructed for the WS measures found to be significant predictors of steps per day in unadjusted analyses- SSWS, MWS, and WSRratio. The only model age remained in as a significant predictor (p = 0.02) was the model predicting steps per day as a function of MWS. The model including both MWS and age as predictors explained 5% more of the variability in steps per day than the model including only MWS (R2 of 0.40 versus 0.35). Of the models, the unadjusted model for SSWS best explained steps per day in our sample. The equation for this model was steps per day = −2186.37 + (8703.80*SSWS).

Logistic Regression

Both SSWS and MWS were significant predictors of not meeting the 8,000 steps per day threshold, while both WSRdiff and WSRratio were not. In unadjusted analysis, age was a significant predictor (p = 0.004) of steps per day, but sex (p = 0.261) was not. Therefore, age was the only covariate adjusted for in multivariate analyses. Age was a significant predictor in both the SSWS (p = 0.04) and MWS (p = 0.02) models. The logit equations for these models with exponentiated coefficients were: <8000 steps/day = 0.07 + (0.02*SSWS) + (1.10*age) and <8,000 steps/day = 0.03 + (0.06*MWS) + (1.11*age).

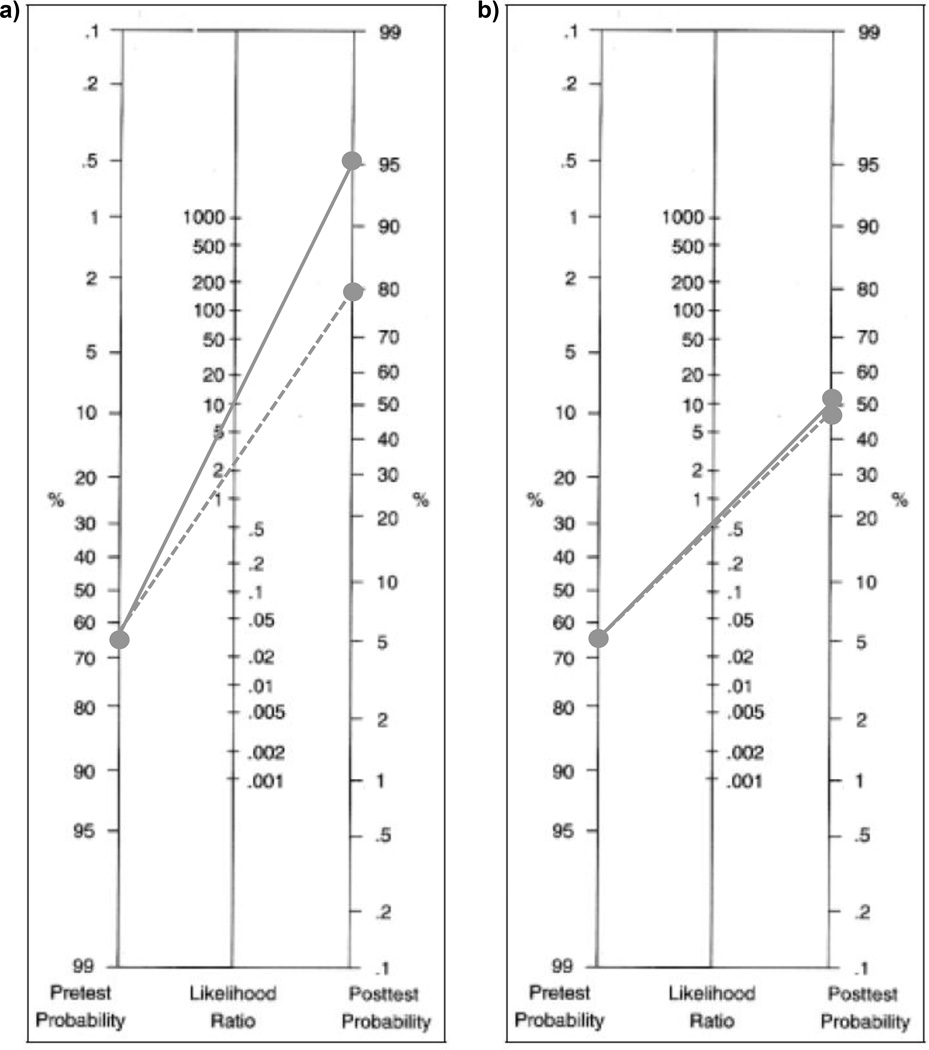

The pre-test probability of not achieving an average of 8,000 steps per day in the sample was 65.2% (43 with <8,000 steps/66 total). The SSWS and MWS cutpoints maximizing sensitivity and specificity for identifying participants not meeting the threshold, along with the associated +LRs and -LRs are presented in Table 3. Applying the associated +LR (10.28) for SSWS shifted the probability that a participant was not averaging at least 8,000 steps per day by 29.9% (pre-test probability 65.2%, post-test probability 95.1%). The -LR (0.58) for SSWS shifted probability by 13.0% (pre-test probability 65.2%, post-test probability 52.2%). The +LR (2.79) associated with the MWS cutpoint shifted the probability that a participant was not averaging at least 8,000 steps per day by 18.7% (pre-test probability 65.2%, post-test probability 83.9%). The -LR for the cutpoint shifted probability by 16.6% (pre-test probability 65.2%, post-test probability 48.6%). See Figure 2.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, Specificity, and Likelihood Ratios for <8,000 steps per day

| SSWS | MWS | |

|---|---|---|

| AUC | 0.71 | 0.72 |

| (0.58, 0.84) | (0.60, 0.85) | |

| Cutpoint (m/s) | ≤0.97 | ≤1.39 |

| Sensitivity | 44.2% | 60.5% |

| (29.4, 60.0) | (44.5, 74.6) | |

| Specificity | 95.7% | 78.3% |

| (76.0, 100.0) | (55.8, 91.7) | |

| +LR | 10.28 | 2.79 |

| (1.45, 71.15) | (1.23, 6.27) | |

| −LR | 0.58 | 0.50 |

| (0.45, 0.76) | (0.34, 0.75) | |

Abbreviations: SSWS, self-selected walking speed; MWS, maximal walking speed; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; m/s, meters per second; +LR, positive likelihood ratio; −LR, negative likelihood ratio

Figure 2.

Nomograms presenting post-test probabilities for “<8,000 steps per day” when individual a) below cutpoint (positive likelihood ratio) and b) above cutpoint (negative likelihood ratio). Cutpoints: 0.97 m/s for self-selected walking speed (solid line) and 1.39 m/s for maximal walking speed (dashed line)

DISCUSSION

Both SSWS and MWS provided insight into daily ambulatory activity in this sample of older adults. A relationship between SSWS and daily ambulatory activity was hypothesized given the measure’s association with ambulatory activity in individuals with stroke and incomplete spinal cord injury (Bowden et al., 2008; Perry et al., 1995; Stevens et al., 2013), as well as with self-reported levels of ambulatory activity in older adults (Talkowski, Brach, Studenski, & Newman, 2008). Although the relationship between MWS and daily ambulatory activity has received less attention, we hypothesized that MWS would also be predictive of steps per day based on the association between MWS and health status and physical activity in older adults (Sallinen et al., 2011; Sartor-Glittenberg et al., 2013). Our findings indicate that there is a relationship between both SSWS and MWS and daily ambulatory activity; individuals with faster SSWSs and MWSs engage in greater ambulatory activity than those with slower speeds.

We also hypothesized that combining SSWS and MWS to quantify an individual’s ability to increase their WS might prove to be a better predictor of daily ambulatory activity than SSWS or MWS alone. WSR is an indicator of adaptability of gait. However, WSR calculated as a difference was not a significant predictor of daily ambulatory activity in this sample of older adults. A potential explanation for the lack of association between WSR calculated as a difference and ambulatory activity may be the strong correlation observed between SSWS and MWS (r = 0.863, 95% C.I. 0.782–0.913). Since WSR is a function of SSWS and MWS, which are both increasing across steps per day, the resultant WSR values are going to be fairly consistent (i.e. low variability) across steps per day (see Figure 1). Due to the strong correlation, an individual with a slow SSWS is likely to have a slow MWS (low WSR as a difference), and an individual with a fast SSWS is likely to have a fast MWS (again, low WSR as a difference). Perhaps in a lower functioning sample, SSWS and MWS would not have been as strongly correlated, and WSR calculated as a difference would have been an informative measure. Although WSR calculated as a difference was not predictive of steps per day, WSR calculated as a ratio was predictive. WSR calculated as a ratio is unit-less and represents an individual’s ability to increase speed relative to their SSWS. For example, individual A may present with a SSWS of 0.2 m/s and a MWS of 0.4 m/s, and individual B with a SSWS of 1.4 m/s and a MWS of 1.6 m/s. Calculated as a difference, both individuals would have WSRs of 0.2 m/s. However, calculated as a ratio, individual A would have a WSR of 2.0 and Individual B would have a WSR of 1.14, indicating that individual A has the ability to double their WS (100% increase) while individual B only has the ability to increase their speed by 14%. Based on our findings it appears the relative increase in WS is more informative than the absolute increase when daily ambulatory activity is the outcome of interest.

Our sample was relatively high-functioning and active for their age. All participants were recruited through retirement communities and senior centers. These sites promote “active lifestyles” and provide members with access to wellness facilities. Average steps per day for our sample was 7261(2904), which is higher than would be expected based on comparison to normative data and similar samples. The steps per day observed in our sample falls within the “Highest” quintile for their average age 80(7) years (Tudor-Locke et al., 2013). Other studies have reported average steps per day ranging from 5600 to 6500 for older adults (Harris et al., 2009; Schuna et al., 2013). Therefore, our results may only be generalizable to active older adults.

Previous studies investigating the relationship between WS and daily ambulatory activity have primarily focused on SSWS and on populations with mobility restrictions (Fulk, Reynolds, Mondal, & Deutsch, 2010; Mudge & Stott, 2009; Stevens et al., 2013). Evidence supports the association between SSWS and ambulatory activity quantified as steps per day in these populations (Fulk et al., 2010; Mudge & Stott, 2009; Stevens et al., 2013). Our findings indicate that the measure may be informative for active, community-dwelling older adults, as well. Boyer et al. 2012, selectively included only active older adults (>7500 steps per day) in a study investigating whether engaging in high levels of activity (steps per day) was protective against age-related declines in selected parameters of gait. Although cadence, step length, and joint kinematics differed between the “Young” (age 29.0(4.9) years) and active “Older” (age 71.2(4.4) years) samples, SSWS did not. The authors conclude that older adults who engage in “a high level of walking activity” maintain SSWSs similar to healthy, young individuals (Boyer et al., 2012). These active older adults also have faster SSWSs than would be predicted by normative data for their age. The SSWS of the “Older” sample in the Boyer et al study was 1.44(0.03) m/s. Based on normative data, a SSWS of 1.1–1.3 m/s would be expected (Bohannon & Williams Andrews, 2011). This study provides further support for an association between SSWS and daily ambulatory activity in active older adults.

When using WS as a screening tool to identify clients who may benefit from increased ambulatory activity, both SSWS and MWS are informative. In our sample, both measures were significant predictors of whether or not a participant averaged <8,000 steps per day. Averaging greater than 8,000 steps per day is associated with reduced risk of metabolic syndrome and is above the threshold for receiving at least 80% of the benefit steps per day confers on BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, insulin sensitivity, HDL levels, white cell count, and fibrinogen levels in individuals similar to the included sample (Ewald et al., 2014; Park et al., 2008). Since both SSWS and MWS were predictive, the clinical usefulness of these measures was compared.

Using LR guidelines, the LRs associated with the SSWS (0.97 m/s) and MWS (1.39 m/s) cutpoints were compared to determine which measure was more informative for predicting daily ambulatory activity in active older adult clients (Jaeschke et al., 1994). The -LRs associated with both measures were close to 0.5, corresponding to “small”/”rarely important” shifts in probability. The +LR associated with SSWS was greater than 10, and therefore, considered “large and conclusive”, while the +LR associated with MWS (2.79) resulted in only a “small” shift in probability. The +LRs indicate that SSWS provides greater insight than MWS into whether a client is achieving an average of at least 8,000 steps per day. Nomograms are valuable clinical tools, as they can be used in combination with LRs to determine a specific patient’s post-test probability of having the outcome of interest. To demonstrate the utility of the nomogram, consider the following example. If a client similar to those included in our sample presents with a SSWS ≤ 0.97 m/s, the probability that they are not meeting the 8,000 steps per day threshold is 95% (see Figure 2). These clients would benefit from increasing their ambulatory activity. As there is a dose-response relationship between steps per day and numerous health markers, any increase in walking activity may be beneficial (Ewald et al., 2014). Therefore, even if clients are falsely identified as not averaging at least 8,000 steps per day, they may still benefit from additional walking.

Combining findings from all analyses indicates that SSWS provides the greatest insight into an older adult client’s daily ambulatory activity when compared to MWS and WSR. The measure demonstrates the strongest correlation with steps per day, explains the greatest variability in steps per day, and a cutpoint of 0.97 m/s provides “large and conclusive” shifts in the probability that the individual being assessed is averaging <8,000 steps per day.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study was the use of an objective measure of daily ambulatory activity, steps per day, rather than reliance on self-report. Although activity monitors collect data on multiple parameters, steps per day was chosen as the outcome of interest. A wealth of evidence supports the relationship between steps per day and health outcomes (Ewald et al., 2014; Tudor-Locke et al., 2011). Time spent engaged in various levels of activity intensity (e.g. sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous) is also captured via activity monitors; however, steps per day is a simple construct that can be easily understood and modified by a typical older adult. Another strength of the study was the monitoring of ambulatory activity over seven days, which captures all days of the week.

Limitations in study design must also be considered when interpreting results. In both linear and logistic regression analyses, covariates considered for entrance into the models were restricted to only a few (age, sex, assistive device use). The authors acknowledge that many other variables (e.g. comorbidities, socio-economic status) could explain daily ambulatory activity. However, the purpose of this study was not to construct a complicated model that maximally explained variability in steps per day in this sample. Rather, the goal was to provide clinicians with insight into which WS measure may be most informative in regards to their client’s community walking behavior. Another limitation is the generalizability of results. The sample was recruited through retirement communities and senior centers. All sites provided members access to wellness centers with exercise equipment and group fitness classes. The sample of older adults included in this study was very active. Caution should be exerted when generalizing results to a less active group. The nature of activity monitoring prevents blinding of subjects, which may have resulted in participants increasing their daily activity levels because they knew they were being observed (Hawthorne Effect). However, the device used for monitoring in this study had no display, so it did not provide the wearer with any feedback. This mitigated the impact knowledge of performance may have had on outcomes. Additionally, during instruction on the activity monitoring protocol, maintaining “normal” routines was emphasized.

Conclusions and Directions for Future Research

Self-selected WS is regarded as a “vital sign” and is a recommended assessment tool for older adults. Findings from this study indicate that in addition to its current uses, SSWS also provides insight into daily ambulatory activity in this population. Ambulatory activity is an important construct to assess, but the utility of activity monitoring is limited by the time required. Self-selected WS may be a feasible proxy for assessing and monitoring daily ambulatory activity in older adults. Future research in less active and lower functioning older adults is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially funded by NIH Grant # T32GM081740.

Contributor Information

Addie Middleton, Department of Exercise Science, Division of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

George D. Fulk, Department of Physical Therapy Chair, Clarkson University, Department of Physical Therapy, Potsdam, NY.

Michael W. Beets, Department of Exercise Science, Division of Health Aspects of Physical Activity, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC University of South Carolina, Department of Exercise Science, Division of Health Aspects of Physical Activity, Columbia, SC.

Troy M. Herter, Graduate Director & Head of the Rehabilitation Sciences Division, University of South Carolina, Department of Exercise Science, Division of Rehabilitation Sciences, Columbia, SC.

Stacy L. Fritz, Physical Therapy Program Director, Rehabilitation Laboratory Director, University of South Carolina, Department of Exercise Science, Division of Rehabilitation Sciences, Columbia, SC.

REFERENCES

- Barreira TV, Brouillette RM, Foil HC, Keller JN, Tudor-Locke C. Comparison of older adults’ steps per day using NL-1000 pedometer and two GT3X+ accelerometer filters. J Aging Phys Act. 2013;21(4):402–416. doi: 10.1123/japa.21.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW. Number of pedometer-assessed steps taken per day by adults: a descriptive meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2007;87(12):1642–1650. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW, Williams Andrews A. Normal walking speed: a descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2011;97(3):182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden MG, Balasubramanian CK, Behrman AL, Kautz SA. Validation of a speed-based classification system using quantitative measures of walking performance poststroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22(6):672–675. doi: 10.1177/1545968308318837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer KA, Andriacchi TP, Beaupre GS. The role of physical activity in changes in walking mechanics with age. Gait Posture. 2012;36(1):149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM, Newman AB, Kriska AM. Identifying early decline of physical function in community-dwelling older women: performance-based and self-report measures. Phys Ther. 2002;82(4):320–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, Nicklas BJ, Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Pahor M. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people--results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1675–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R, Kuh D, Cooper C, Gale CR, Lawlor DA, Matthews F, Teams HAS. Objective measures of physical capability and subsequent health: a systematic review. Age and Ageing. 2011;40(1):14–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo LL, Menec VH, Ready AE. Relationship of Functional Fitness With Daily Steps in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2014 doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e3182abe75f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DocNomo. from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/docnomo/id901279945?mt=8.

- Elbaz A, Sabia S, Brunner E, Shipley M, Marmot M, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Association of walking speed in late midlife with mortality: results from the Whitehall II cohort study. Age (Dordr) 2013;35(3):943–952. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9387-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald B, Attia J, McElduff P. How many steps are enough? Dose-response curves for pedometer steps and multiple health markers in a community-based sample of older australians. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(3):509–518. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald B, McEvoy M, Attia J. Pedometer counts superior to physical activity scale for identifying health markers in older adults. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(10):756–761. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.048827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan TJ. Letter: Nomogram for Bayes theorem. New England Journal of Medicine. 1975;293(5):257. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197507312930513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley S, Quinn S, Jones G. Pedometer determined ambulatory activity and bone mass: a population-based longitudinal study in older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(11):1809–1816. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KR, Ku PW, Hillsdon M, Davis MG, Simmonds BA, Thompson JL, Coulson JC. Objectively assessed physical activity and lower limb function and prospective associations with mortality and newly diagnosed disease in UK older adults: an OPAL four-year follow-up study. Age and Ageing. 2015;44(2):261–268. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz S, Lusardi M. White paper: “walking speed: the sixth vital sign”. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2009;32(2):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulk GD, Reynolds C, Mondal S, Deutsch JE. Predicting home and community walking activity in people with stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(10):1582–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ortiz L, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Schmidt-Trucksass A, Puigdomenech-Puig E, Martinez-Vizcaino V, Fernandez-Alonso C, Group E. Relationship between objectively measured physical activity and cardiovascular aging in the general population - The EVIDENT trial. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233(2):434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A, Schepens S. Measurement error and minimum detectable change in 4-meter gait speed in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2011;23(5-6):406–412. doi: 10.1007/BF03325236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JE, Ostir GV, Fisher SR, Ottenbacher KJ. Assessing walking speed in clinical research: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(4):552–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TJ, Owen CG, Victor CR, Adams R, Ekelund U, Cook DG. A comparison of questionnaire, accelerometer, and pedometer: measures in older people. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2009;41(7):1392–1402. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31819b3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TL, Swartz AM, Cashin SE, Strath SJ. How many days of monitoring predict physical activity and sedentary behaviour in older adults? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users’ guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994;271(9):703–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpan SM, Schafer JL, Wilson KC, Webber SC. Effect of ActiGraph GT3X+ Position and Algorithm Choice on Step Count Accuracy in Older Adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2014 doi: 10.1123/japa.2014-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH, Nan H, Yu YY, McDowell I, Leung GM, Lam TH. For non-exercising people, the number of steps walked is more strongly associated with health than time spent walking. J Sci Med Sport. 2013;16(3):227–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann U, Najafi B, Zijlstra W, Hauer K, Muche R, Becker C, Aminian K. Distance to achieve steady state walking speed in frail elderly persons. Gait Posture. 2008;27(1):91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton A, Fritz SL, Lusardi M. Walking Speed: The Functional Vital Sign. J Aging Phys Act. 2014 doi: 10.1123/japa.2013-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosallanezhad Z, Salavati M, Sotoudeh GR, Nilsson Wikmar L, Frandin K. Walking habits and health-related factors in 75-year-old Iranian women and men. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58(3):320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudge S, Stott NS. Timed walking tests correlate with daily step activity in persons with stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(2):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RL, Jr, Han H, Johnson WD, Hickson DA, Church TS, Taylor HA, Dubbert PM. Steps/day and metabolic syndrome in African American adults: the Jackson Heart Study. Prev Med. 2013;57(6):855–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltamaa J, Sarasoja T, Leskinen E, Wikstrom J, Malkia E. Measuring deterioration in international classification of functioning domains of people with multiple sclerosis who are ambulatory. Phys Ther. 2008;88(2):176–190. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Park H, Togo F, Watanabe E, Yasunaga A, Yoshiuchi K, Aoyagi Y. Year-long physical activity and metabolic syndrome in older Japanese adults: cross-sectional data from the Nakanojo Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(10):1119–1123. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel NM, Kuys SS, Klein K. Gait speed as a measure in geriatric assessment in clinical settings: a systematic review. Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2013;68(1):39–46. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J, Garrett M, Gronley JK, Mulroy SJ. Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke. 1995;26(6):982–989. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters DM, Fritz SL, Krotish DE. Assessing the reliability and validity of a shorter walk test compared with the 10-Meter Walk Test for measurements of gait speed in healthy, older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2013;36(1):24–30. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e318248e20d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CL, Kautz SA, Neptune RR. Braking and propulsive impulses increase with speed during accelerated and decelerated walking. Gait Posture. 2011;33(4):562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrella JK, Cress ME. Daily ambulation activity and task performance in community-dwelling older adults aged 63-71 years with preclinical disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):264–267. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn L, Khalil H, Dawes H, Fritz NE, Kegelmeyer D, Kloos AD, Outcome Measures Subgroup of the European Huntington’s Disease, N. Reliability and Minimal Detectable Change of Physical Performance Measures in Individuals With Pre-manifest and Manifest Huntington Disease. Phys Ther. 2013;93(7):942–956. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries JD, Echternach JL, Nof L, Gagnon Blodgett M. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change scores for the timed “up & go” test, the six-minute walk test, and gait speed in people with Alzheimer disease. Phys Ther. 2009;89(6):569–579. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosano C, Newman AB, Katz R, Hirsch CH, Kuller LH. Association between lower digit symbol substitution test score and slower gait and greater risk of mortality and of developing incident disability in well-functioning older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(9):1618–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallinen J, Manty M, Leinonen R, Kallinen M, Tormakangas T, Heikkinen E, Rantanen T. Factors associated with maximal walking speed among older community-living adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2011;23(4):273–278. doi: 10.1007/BF03337753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor-Glittenberg C, Lehmann S, Okada M, Rosen D, Brewer K, Bay RC. Variables Explaining Health-Related Quality of Life in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2013 doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e3182a4791b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimpl M, Moore C, Lederer C, Neuhaus A, Sambrook J, Danesh J, Daumer M. Association between walking speed and age in healthy, free-living individuals using mobile accelerometry--a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):23299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuna JM, Jr, Brouillette RM, Foil HC, Fontenot SL, Keller JN, Tudor-Locke C. Steps per day, peak cadence, body mass index, and age in community-dwelling older adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2013;45(5):914–919. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31827e47ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada H, Suzuki T, Suzukawa M, Makizako H, Doi T, Yoshida D, Park H. Performance-based assessments and demand for personal care in older Japanese people: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson SB, Camhi SM, Church TS, Tudor-Locke C, Johnson WD, Katzmarzyk PT. Accelerometer-determined steps/day and metabolic syndrome. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(6):575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens SL, Fuller DK, Morgan DW. Leg strength, preferred walking speed, and daily step activity in adults with incomplete spinal cord injuries. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2013;19(1):47–53. doi: 10.1310/sci1901-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talkowski JB, Brach JS, Studenski S, Newman AB. Impact of health perception, balance perception, fall history, balance performance, and gait speed on walking activity in older adults. Phys Ther. 2008;88(12):1474–1481. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C, Bassett DR, Jr, Rutherford WJ, Ainsworth BE, Chan CB, Croteau K, Wojcik JR. BMI-referenced cut points for pedometer-determined steps per day in adults. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5(Suppl 1):126–139. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.s1.s126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Aoyagi Y, Bell RC, Croteau KA, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Blair SN. How many steps/day are enough? For older adults and special populations. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:80. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C, Schuna JM, Jr, Barreira TV, Mire EF, Broyles ST, Katzmarzyk PT, Johnson WD. Normative steps/day values for older adults: NHANES 2005-2006. Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2013;68(11):1426–1432. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallance JK, Eurich D, Lavallee C, Johnson ST. Daily pedometer steps among older men: associations with health-related quality of life and psychosocial health. Am J Health Promot. 2013;27(5):294–298. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120316-QUAN-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner M, Martin BW, Meier F, Probst-Hensch N, Kriemler S. Effects of filter choice in GT3X accelerometer assessments of free-living activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):170–177. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31826c2cf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G, Schache AG, Morris ME. Self-selected walking speed predicts ability to run following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2013;28(5):379–385. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182575f80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]