Abstract

Objectives:

Occupational injuries remain an important unresolved issue in many of the developing and developed countries. We aimed to outline the causes, characteristics, measures and impact of occupational injuries among different ethnicities.

Materials and Methods:

We reviewed the literatures using PUBMED, MEDLINE, Google Scholar and EMBASE search engine using words: “Occupational injuries” and “workplace” between 1984 and 2014.

Results:

Incidence of fatal occupational injuries decreased over time in many countries. However, it increased in the migrant, foreign born and ethnic minority workers in certain high risk industries. Disproportionate representations of those groups in different industries resulted in wide range of fatality rates.

Conclusions:

Overrepresentation of migrant workers, foreign born and ethnic minorities in high risk and unskilled occupations warrants effective safety training programs and enforcement of laws to assure safe workplaces. The burden of occupational injuries at the individual and community levels urges the development and implementation of effective preventive programs.

Keywords: Injury prevention, occupational injuries, workplace

INTRODUCTION

Occupational or work-related injuries became more common after the industrial revolution. Over time, in response to great demand for better working conditions, the first occupational laws were enacted in 19th century in England.[1] Occupational injuries are associated with lots of suffering and loss at individual, community, societal and organizational levels. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO); occupational injuries and diseases represented 4% of total Gross National Product (GNP).[2,3] Since occupational injuries may occur by dangerous actions of workers, the prevention programs should focus on the human performance, behavior and factors in terms of better training, education and motivation of workers.[4] However, certain industrial sectors with high risk of injury have central role in the global burden of occupational injuries and should be a part of the prevention strategy. Nearly half of the worker population in highly industrialized countries and even more in newly industrialized and developing countries are exposed to the risk of fatal injuries.[4] Occupational fatal injuries therefore still remain as worldwide problem.

With the globalization, the burden of fatal occupational injuries is not limited to the native worker population. Many industries around the world depend on low-cost labor supplied by millions of people who cross borders in response to the unemployment and lack of economic, social and political stability in their home countries. Due to the ease of international travel coupled with the economic opportunism, the movement of laborers between countries and continents has become a permanent feature of global economy.[5,6,7] Combined the numbers of migrants around the globe would equate to the fifth most populous country in the world.[2] Although the immigration is associated with positive outcomes in host countries such as low inflation and higher Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the large and diverse workforce influx may cause unwanted social frictions and increased burden on public services to facilitate integration with host population.[1,3] Evidence suggests that migrant workers along with ethnic minorities are at greater risk for fatal occupational injuries than native workers and these disparities exist even among the workers of the same occupational category.[1,2,3,4,5] We do believe that identification of personal and workplace characteristics that determine the vulnerability of migrant and ethnic minority workers will contribute to the injury prevention programs and draw the attention of policy makers and trauma prevention researchers. Herein, the current review addresses the occupational injuries in workers from different ethnicities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This paper reviewed the published literature and official reports on occupational injuries worldwide. We reviewed the literatures using PUBMED, MEDLINE, Google Scholar and EMBASE search engines using key words: “occupational injuries”, “workplace” between 1984 and 2014. Abstract, articles in non-English language and those related to occupational diseases were excluded. We aim to provide an overview of differential burden of fatal occupational injuries by regions and countries and to explore the key factors that make the migrant workers and ethnic minorities more vulnerable to the fatal occupational injuries.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Electronic database search method yielded 1,655 citations. One hundred twenty seven articles were found relevant which included research studies as well as official statistics produced by different countries. A large part of the relevant studies (n = 59) were from USA. Similarly, the majority (n = 57) were retrospective studies which aggregated and analyzed national and large regional datasets collected by governmental and private firms. Nine studies were based on population characteristics such as citizenship, place of birth or ethnicity. Retrospective and cross sectional studies utilized data sources such as official labor statistics (n = 23), national injury surveillance system (n = 19), questionnaire/interview based surveys (n = 18), worker's compensation claims (n = 17), hospital records (n = 15), national surveys (n = 9) and death certificates (n = 6). Most of the published studies included employees as study subjects regardless of the demographic profile, mechanism of injury or occupational sector. However, some authors have confined their study population to young (n = 3 articles), old (n = 3), male (n = 2) or female (n = 2) employees. Some authors reported workplace injuries by industry sectors such as agricultural/farm/fisheries (n = 10), healthcare (n = 10), other services (n = 4), mining/quarrying/oil extraction (n = 6), wholesale/retail trade (n = 5), construction (n = 4) and transportation (n = 3). Moreover, we found different terminologies could cause confusion when used for describing common topics such as workplace injury, workplace related commuting accident, and occupational injuries, injuries or diseases (communicable or non-communicable). For clarity, the following definitions were used: “An occupational injury is defined as any personal injury, disease or death resulting from an occupational accident; an occupational disease, is a disease contracted as a result of an exposure over a period of time to risk factors arising from work activity; an occupational accident is an unexpected and unplanned occurrence, including acts of violence, arising out of or in connection with work”.[2]

Incidence and trends of occupational fatalities

To the best of our knowledge, the first global estimate of fatal occupational injuries in 1999 showed that approximately 700,000 deaths occur annually.[8] At the same time, Takala added that 335,000 fatalities occur per year from occupational injuries and 158,000 fatalities from work-related commuting injuries.[9] In 2005, Concha-Barrientos estimated around 312,000 unintentional occupational fatal injuries takes place annually.[10] Recently, World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 20-50% of workers are exposed to hazards at work in industrialized countries and this rate may be higher in the developing and newly industrialized counties.[4] Estimates based on ILO and the World Bank Group data in 2013, show 2.34 million occupational fatalities occur per year in a global workforce of 3.3 billion, with an incidence rate of 71 per 100,000 workers per year.[2]

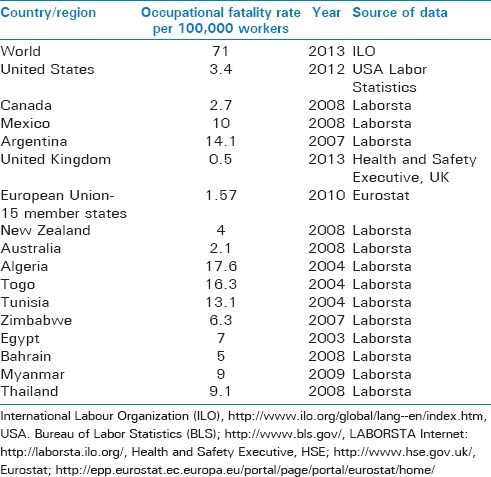

Hamalainen et al. in 2009 published fatality rates from different countries based on WHO regions and the ILO published statistics (Laborsta). The authors reported fatality rates in USA. per 100,000 workers in 1998, 2001 and 2003 as 5.2, 4.9 and 5 respectively.[3] The USA. bureau of Labor statistics reported 4.2 and 3.4 fatal occupational injuries per 100,000 workers in 2006 and 2012 respectively.[11,12] Similarly, Laborsta in 2001 (4.9 per 100,000 workers) and the USA. Labor Statistics in 2011 (3.5 per 100,000 workers) demonstrated a nearly 30 percent decrease in the incidence of fatal occupational injuries over ten years duration.[13,14,15] Therefore, these data indicate a downward trend in incidence of fatal occupational injuries over time.

Laborsta showed a fatality rate of 0.8 per 100,000 workers in UK in 2003, whereas, the Health and Safety Executive revealed a rate of 0.5 per 100,000 workers per year across the period from 2012 to 2013.[3,16] This difference in ten year duration shows 40 percent decrease in the incidence of fatal occupational injuries in UK.

The statistical authority for the European Union (Eurostat) reported an average fatal occupational injury rate of 1.57 per 100,000 workers across more than 15 European countries in 2010.[16] Eight countries, namely Slovakia, Netherlands, Great Britain, Germany, Denmark, Ireland, Finland and Sweden reported fatality rates below this average. The highest fatality rate was reported in Cyprus followed by Romania, Luxembourg, Lithuania and Portugal; all with fatality rate higher than 3 per 100,000 workers in 2010.[13,16] In Cyprus, the Laborsta estimations in 1998 and 2001 were 15.5 and 12.9 which dropped to 3 per 100,000 workers in 2003. Similarly, countries such as Romania, Luxembourg, Lithuania and Portugal showed a higher fatality rate in 2003 when compared to 2010 data.[13,16]

An independent taskforce on workplace health and safety in New Zealand (NZ) compared the fatal occupational injury rates in nine countries over the period 2005-2008 and reported the highest fatal occupational injury rate in NZ, with more than 4 fatalities per 100,000 person years.[17] This high rate in NZ was followed by Spain and France where more than 3 fatalities per 100,000 person years reported. Canada and Australia had more than 2 fatalities per 100,000 person years, whereas Norway along with Finland, Sweden and UK, as shown by Eurostat data, reported best rates below 2 fatalities per 100,000 person years.[16,17] Laborsta showed high rates of fatalities in African countries like Algeria, Togo and Tunisia with 17.6, 16.3 and 13.1 fatalities per 100,000 workers respectively, in 2004.[13,18] However, the fatality rates in Egypt and Zimbabwe were lower compared to other African countries. Egypt reported 7 deaths per 100,000 workers in 2003 while in Zimbabwe it was 6.3 deaths per 100,000 workers in 2007.[13]

In Asian countries; Bhutan (31.9), Nepal (28.8), Myanmar (26.2), Bangladesh (21.8) and Afghanistan (21.7) reported high occupational fatality rates in 2003.[3] India ranks the second largest workforce in the world (473,200,000 economically active populations in 2003) showed comparatively less occupational fatality rate of 9.9 per 100,000 workers. Meanwhile, China being the most populous country (737,060,000 economically active populations in 2003) reported fatality rate of 13.2 per 100,000 workers.[3] Data from the Middle East countries including the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries also show variation in the occupational fatality rates. In 2003, among the GCC countries; UAE (9.8) Qatar (9.2) and Bahrain (8.3) had similarly high fatality rates, while Saudi Arabia (7.9), Oman (7.1) and Kuwait (5.9) showed fatality rate lower than the average of the region (8 per 100,000 workers).[3] A recent data from Qatar showed that the overall case fatality was 3.7% among workers who were presented to the trauma unit between 2010 and 2012.[19]

The WHO uses six major regions to describe the global burden of diseases; AFRO (Africa), AMRO (Americas), SEARO (South-East Asia), EURO (Europe), EMRO (Eastern Mediterranean) and WPRO (Western Pacific).[3] These regions are divided into 14 sub-regions. In 2003, economically active populations of the world were around 3 billion, out of which around 1.86 billion was employed and around 3, 57,948 fatal injuries were recorded. The majority of the fatalities were reported in WPRO B region (30% of total fatalities) where the proportion of workers was highest (40% of all workers). However, the fatality rates were highest for AFRO D and SEARO D regions with 22.9 and 22.8 per 100,000 workers respectively. This rate was followed by AFRO E and AMRO D regions.[3] Table 1 shows recently available estimations of fatal occupational injuries in some countries and regions. Laborsta data were not available for most of the countries and the recent update of Laborsta was in 2008 for many countries.

Table 1.

Occupational fatality rates in different countries and regions

Fatal injury statistics -methodological issues

Initially epidemiological studies aimed at prevention of injuries were limited to certain developed countries. Industrialization and urbanization coupled with increased health and safety problems worldwide required better compilation of statistics to make global and regional comparisons and thereby develop appropriate preventive measures.[3,4,8,11] Currently, some limitations exist and cause uneasiness of data comparisons because of the variation of the definitions and coding systems worldwide. For example, fatal occupational injuries in Netherlands are registered when the victim dies on the same day of the accident whereas in Germany it is recorded if victim dies within 30 days.[3] In some countries, this time limit is extended to one year and in some others there is no such limit.

Underreporting is another issue in occupational injury statistics that may identify some countries with weaker safety measures to gain unfair advantage over the countries with strict regulations.[3,17] The average reporting levels in different countries were shown by the European commission in 2001 as; Sweden 52%, Denmark 46%, UK 43%, Greece 39% and Ireland 38%.[3] Moreover, missing or lack of published data on occupational injuries in addition to the variations in estimates in different reports are commonly encountered in the developed and developing countries.[3] The annual incidence of fatalities from occupational injuries and diseases in USA. was reported as 66,822 in 1997 which was higher when compared to official figures.[11] In 2003, Steenland et al. reported this annual incidence as 55,254 deaths.[12] Nurmine and Karjalainen in 2001 showed the annual incidence of deaths attributed to occupational injuries in Finland were 1810 deaths while the official figures showed less than 200 deaths.[20] Underreporting was also recognized in countries like Malaysia[21] and Argentina[22] in the last decade.

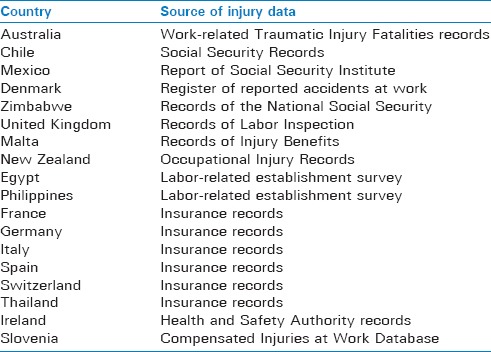

Evidence suggests that while making comparison between countries, the standardized coding system and harmonization of occupational injury statistics are required. Incomplete data or ignoring the documentation of certain occupational group of workers may lead to underestimation of the actual occupational injuries and fatalities.[3] According to the Laborsta, Australian data are based on workers covered by the Australian Workers Compensation Schemes, which exclude defense force workers and self-employed workers in the agricultural industry.[13,23] It is evident that agricultural sector largely contributes to the fatal injuries worldwide. Similarly, the insurance derived data influence the coverage of workers since the insurance scheme may exclude important groups of workers. Non-claiming of compensable injuries and non-inclusion of non-compensable injuries may lead to underestimation of occupational fatal injury rate.[24] Other methodological issues in place that prevent fair comparisons between different countries in which self-employed workers and road traffic occupational fatal injuries may be excluded from their database.[17] Moreover, countries like NZ did not discriminate fatalities due to occupational diseases and injuries.[17] So far, only few countries are able to conduct international comparative studies. Feyer et al. compared the work-related fatal injuries in the USA., Australia and NZ in 2001.[25] Spangenberg et al. in 2003 compared the fatal injuries in the construction sectors in Sweden and Denmark.[26] In 2008, Nishikitani and Yano compared the fatal injuries in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.[27] Recently, Lilley et al. compared and analyzed data of the Laborsta fatal injury rates of NZ with eight countries such as Australia, Canada, and UK.[17]

The comparative studies showed wide variations in the socioeconomic status in correlation to occupational fatal injury data. Appropriate denominator data, i.e., the estimated working population seems to be an important factor while making comparisons, and should have the same coverage of workers as the numerator (count of fatal injuries).[17] In other words, if the numerator excludes self-employed workers, the denominator should exclude these workers. The differences in industry composition within a country should be taken into account while analyzing the data. Certain industries are associated with high fatal occupational injuries and high proportion of workers and therefore the difference in industry composition and activities between countries should be adjusted to give valid comparative results.[17] Sorensen et al. showed that employees in small sized firms have a greater risk of occupational fatal injury.[28] Countries with large proportion of small sized firms, like NZ where 97% of all firms are small sized firms with 20 or fewer workers, may show high fatality rates.[29] Table 2 shows sources of Laborsta injury data in different countries.

Table 2.

Sources of laborsta injury data from different countries

Differentials in fatalities in migrants and ethnic minorities

Migrant workers, according to the UK definition, are those who arrived in the country in last five years, which includes both stocks (resident migrants) and flows (new migrants).[30,31] This definition also includes the illegal workers. Foreign born workers are defined as those who are born outside the country and over 16 years of age. In 2007, more than one third of foreign born in the total workforce were UK nationals. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between foreign workers and migrant workers.[31] The Labour Force Survey (LFS) in 2008 estimated that foreign workers constitute 12.5% of total work force, i.e. 3.68 million.[31] Injuries and fatalities in different ethnicities were discussed in many studies in different countries. For example, the USA. based studies used White/Black; Hispanic/non-Hispanic classification of ethnicities.

Hispanics/Latinos contribute to the major workforce in USA. The fatal injury rate reported in USA. during 2006 to 2008 was 4 per 100,000 full time equivalent employees (FTE) whereas the rate corresponding to the Hispanic or Latino workers were 4.8 per 100,000 FTEs.[7,32] This means that a 20% high rate of fatal injuries incurred by Hispanic/Latinos. Although the overall rate and the rate incurred by Hispanics/Latinos decreased over time, the fatal injury rate was higher in Hispanics/Latinos in all years when compared to the overall rate.[7]

Moreover, 54% of these Hispanic/Latino workers (11 million) were foreign-born whereas 34% (9 million) represented USA.-born workers. More interestingly, 66% of the total fatal injuries reported in Hispanics/Latinos were incurred by foreign born Hispanics/Latinos in 2008 and most of them (46%) were born in Mexico.[14,15] The Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) data also showed this disproportionate share of foreign-born Hispanics/Latinos in fatal injuries in the following years; in 2011 it was reported as 68 percent.[7,15] The average fatality rate in foreign-born and USA.-born Hispanics/Latinos in the duration of 2006-2008 was recorded as 5.7 and 3.6 per 100,000 FTEs respectively.[7]

In Spain, the 2003 data revealed the disparities in incidence of occupational fatal injuries between Spanish workers and foreign workers. Foreign workers had an increased risk (43 per 100,000 workers) in every age group and in both genders when compared with Spanish workers (8.5 per 100,000 workers). Foreign women had a risk over six times higher than Spanish women workers. Older workers with age 55 years or above had fatal injuries almost 15-fold higher than their Spanish counterparts.[33]

Occupations and fatal occupational injuries

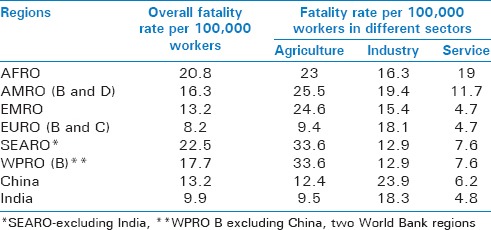

Agricultural, forestry and fishing are considered as high injury risk industries. The fatal injury data by region in 2003 showed agricultural sector largely contributed to the fatalities in most of the WHO regions including AFRO, AMRO, EMRO, SEARO and WPRO.[3] However, in EURO region, India and China; industrial sector was the major contributor, suggesting the differences in industrial composition by region or countries.[3] Agriculture was the leading sector in fatal injury rates in UK with a fatality rate of 8.8 per 100,000 workers in 2012-2013.[16] In Ghana, Mock et al. showed that 76% of the total occupational injuries were in farm workers in rural areas.[34]

Table 3 shows fatality rates reported in different sectors in WHO and World Bank regions in 2003. Construction and oil/gas industries are associated with high case fatalities. USA. reports showed increase in fatalities in oil and gas extraction industries; rose 23 percent in 2012 compared to previous year.[14] Transport sector also carries significant fatality rates. In 2012, transportation incidents accounted for 42 percent of total fatal occupational injuries in USA.[14] In Australia, transport sector recorded 11-fold increase in the mortality rate in comparison to the other sectors which equated to a rate of nearly 21 deaths per 100,000 workers.[23] To a lesser extent, the agriculture sector accounted for 15 deaths per 100 000 workers.[23] Truck related incidents including crash on public road caused death of many workers and recorded as 27% of the total worker mortality in 2010-2011.[23]

Table 3.

Fatality rates reported in different sectors in WHO and World Bank regions in 2003

The mechanisms of injuries vary with the nature of occupations and industries. Fall in industrial locations was the strongest contributor to fatal injuries in USA. According to recent USA reports, fall accounts for 15 percent of the total fatalities in occupations.[14] Nearly 16 percent of the total occupational fatalities in USA were due to contact with objects and equipments.[14] The UK reports revealed that fall accounted for 59% of fatal injuries in construction industry in UK in 2012-2013.[16] In UAE the majority of hospital admissions and fatalities were due to occupational injuries in terms of fall from height and falling of heavy objects.[35] More than half of the occupational injury mechanisms reported in Qatar during 2010-2012 was fall from height and majority of the victims represented the construction sector.[19]

Migrants and ethnic minorities in high risk occupations

By reviewing data from 2003 to 2005 in USA, Orrenius and Zavondy reported that migrants are more likely to work in high risk industries when compared to native workers.[6] They also demonstrated a difference in the rate of occupational fatalities at 1.79 deaths per 100,000 workers between migrant and native workers.[6] Occupations in healthcare sector in USA are considered as high risk industries. Arnold pointed out that 20% of the occupations in USA healthcare industry are occupied by African-American women who constitute only 6.8% of the total workforce.[36] In addition, Robinson reported on the continuous exposure of occupational hazards in Hispanics and Blacks regardless of education and experience.[37] Moreover, a 33% increased risk of occupational injuries were observed in Hispanic males whereas it was 17% in Black males.[37]

Hispanic/Latino workers in farming, forestry, and fishing sectors had high rate of occupational fatalities (19.4 per 100,000 FTEs) during the period of 2006-2008.[7] This rate was higher (32.6 per 100,000 FTEs) in native-born Hispanic/Latino workers when compared to foreign born counterparts (18 per 100,000 FTEs).[7] In terms of rate, the low fatality rate in foreign-born when compared to native-born reflect the large number of foreign-born involved in farming, forestry, and fishing sectors. Construction and extraction industry had the highest risk of fatalities which accounted for 35% of total Hispanic/Latino worker fatalities (74% foreign-born vs. 26% native-born) followed by transportation and material moving (All Hispanics/Latinos 20%; 58% foreign-born vs. 42% native-born).[7]

In 2011, Menéndez and Havea described the trends in occupational fatalities among foreign-born workers in USA. Fatalities in Hispanics increased (54% to 60%) but decreased in non-Hispanics (44% to 38%) in the period of 1992-2007.[38] Also, high growth in proportion of fatalities (by 117%) was reported in foreign-born workers in that period of time. The highest increase in the number of fatalities was reported in mining sector (243%) followed by construction industry (344%). The construction industry contained the greatest number of foreign-born workers (25%).[38]

Other countries also reported high risk for occupational fatalities among migrant or ethnic minority workers.[19,35,38] The hospital records based studies in the GCC countries also showed high rate of injuries in migrant workers as 69% of the patients presented at the trauma centers were migrant workers in UAE and Qatar.[19,35] Most of the patients in Qatar were involved in industrial work (43%) followed by transportation (18%).[19] Fall from height (51%) or contact with heavy objects (18%) were frequent causes of injury also indicated the increased risk of construction sector in the GCC countries.[19] Oil and gas industry in this region also possess increased risk of injuries. Reports from an oil field in Oman revealed 93% of the injured workers were migrants.[39] Notably, 94% of the total workforce in Qatar are migrant workers.[40]

Characteristics of subjects with fatal occupational injuries

The proportion of unskilled workers and low socioeconomic status in the migrant worker population is associated with increased occupational fatality rate. Bourdillon et al. reported migrant workers in the lowest socio-economic status groups in France often concentrate in unskilled occupations.[41] The majority of illegal immigrants also work in low-skill, low-wage occupations.[5,42] Cubbin et al. reported the association between blue collar occupations and risk of occupational injuries in USA.[42] Education was related to incidence and severity of the injury.[42,43]

Migrants are predominantly young males. Both young age and male gender were found to be associated with increased risk of occupational injuries.[5,6,42,43] All Hispanic males in USA are at increased risk of injuries.[35] Nearly 33% of the injured Hispanic males were under the age of 18 years whereas it was 20% in non-Hispanic males.[7,37] Similarly, majority of the occupational injury patients reported in GCC countries were young males.[19,35] Long hours of work and fatigue also contribute to occupational injuries.[42] A higher rate of injuries was reported in migrant workers in small factories when compared to large factories.[42,44]

Lack of language proficiency, poor communication and lack of on-the-job training, particularly in new migrants, may lead to higher rate of occupational injuries.[5,43] Lower levels of education and language ability act as barriers in understanding the risks associated with occupations. Nearly 32% of foreign-born adults over the age of 25 years in USA lack high school level education, while this was 11% in the case of natives.[32] Moreover, about 35% of migrants in USA have limited ability in English.[43] Similarly, lack of the needful skills was evident in the Pacific Island migrant workers in NZ who experienced higher rate of injuries.[44]

Selection of high risk occupations by the new migrant workers together with barriers in understanding of safety precautions result in disproportionately greater incidence of severe injuries. Therefore, appropriate communication in multicultural and multilingual workforce should be addressed properly to deliver effective health and safety measures. Racial differences in exposure may narrow over time with risk reduction, improvement in technology, better safety and prevention measures and increased awareness.[44] However, factors like poverty, lack of labor rights, opportunities for collective bargaining, health insurance, and access to family and other support systems make migrant workers more vulnerable to occupational injuries and fatalities.[5]

Limitations

Access to reliable data is vital to analyze trends and patterns in occupational injuries. Many countries have not yet provided or updated their occupational injury data with publicly available databases like laborsta. Particularly, occupational injury data from many African and Asian countries are not available and if available they are nearly a decade old or had inaccurate documentations. Therefore, the accuracy or even transparency of data documentation in most of the developing countries should be taken cautiously. Another limitation of the study is the lack of comparative studies to represent all WHO regions. Only few comparative studies are published till date. Methodological issues related to underreporting and source of data, as mentioned in this paper, could have influenced the results of comparative studies. Exclusion of workplace injuries associated with assaults and violent acts is of concern. These are the second most frequently occurring injury events in many countries. Lack of coverage on occupational diseases also limits the generalizability and utility of the study findings. Occupational diseases such as hearing loss, sleep disorder, occupational stress, skin disease, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders, respiratory diseases, cancer and disease acquired from animals are not well documented in many countries and are excluded in this paper.

CONCLUSIONS

Occupational injuries remain an important issue worldwide particularly after the economic globalization and industrialization. High risk nature of certain occupations and concentration of migrant workers and ethnic minorities in these high risk occupations contribute to the increased rate of fatal occupational injuries. Impacts at individual, community, societal and organizational levels warrant development and implementation of effective prevention programs and enforcement of laws to assure safe workplaces.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

All authors read and approved this manuscript with no conflict of interest and no financial issue to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hämäläinen P, Takala J, Saarela KL. Global estimates of fatal work-related diseases. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50:28–41. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Labour Organization, Safety and health at work, ILO, 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 20]. Available from: http://ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/langen/index.htm .

- 3.Hämäläinen P, Leena Saarela K, Takala J. Global trend according to estimated number of occupational accidents and fatal work-related diseases at region and country level. J Safety Res. 2009;40:125–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization, Global strategy on occupational health for all: The way to health at work, WHO. 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/globstrategy/en/index4.html .

- 5.Schenker M. Migration and Occupational Health: Understanding the Risks, Migration Policy Institute, MPI: USA. 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/migration-and-occupational-health-understanding-risks .

- 6.Orrenius PM, Zavodny M. Do immigrants work in riskier jobs? Demography. 2009;46:535–51. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byler CG. Fatal Injuries to Hispanic/Latino Worker, USA. Department of Labor. 2013. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/02/art2full.pdf .

- 8.Leigh J, Macaskill P, Kuosma E, Mandryk J. Global burden of disease and injury due to occupational factors. Epidemiology. 1999;10:626–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takala J. Global estimates of fatal occupational accidents. Epidemiology. 1999;10:640–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Concha-Barrientos M, Nelson DI, Fingerhut M, Driscoll T, Leigh J. The global burden due to occupational injury. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:470–81. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leigh JP, Markowitz SB, Fahs M, Shin C, Landrigan PJ. Occupational injury and illness in the United States. Estimates of costs, morbidity, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1557–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steenland K, Burnett C, Lalich N, Ward E, Hurrell J. Dying for work: The magnitude of USA mortality from selected causes of death associated with occupation. Am J Ind Med. 2003;43:461–82. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LABORSTA, Occupational Injuries.1996-2010, International Labour Organization, ILo. 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://laborsta.ilo.org/

- 14.USA. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries in 2012 (Preliminary Results), USA. Department of Labor. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsh SM, Menéndez CC, Baron SL, Steege AL, Myers JR. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fatal work-related injuries - United States, 2005-2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;6(Suppl 3):41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health and Safety Executive, Statistics on fatal injuries in the workplace in Great Britain 2013, HSE. 2013. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/pdf/fatalinjuries.pdf .

- 17.Lilley R, Samaranayaka A, Weiss H. International comparison of International Labour Organisation published occupational fatal injury rates: How does New Zealand compare internationally' Commissioned report for the Independent Taskforce on Workplace Health and Safety, 2013, Health and Safety Taskforce, New Zealand. [Last accessed on 2014 Sept 20]. Available from: http://www.hstaskforce.govt.nz/documents/comparison-of-ilo-published-occupational-fatal-injury-rates.pdf .

- 18.Machida S. System for collection and analysis of occupational accidents data. Afr Newslett Occup Health Safety. 2009;19:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Thani H, El-Menyar A, Abdelrahman H, Zarour A, Consunji R, Peralta R, et al. Workplace-related traumatic injuries: Insights from a rapidly developing middle eastern country. J Environ Public Health 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/430832. 430832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nurminen M, Karjalainen A. Epidemiologic estimate of the proportion of fatalities related to occupational factors in Finland. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2001;27:161–213. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abas AB, Said AR, Mohammed MA, Sathiakumar N. Occupational disease among non-governmental employees in Malaysia: 2002-2006. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2008;14:263–71. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2008.14.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werner AF. Occupational health in Argentina. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2000;73:285–9. doi: 10.1007/s004200000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safe Work Australia, Work-related Traumatic Injury Fatalities, Australia 2010-11, Australia. 2013. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/SWA/about/Publications/Documents/730/WorkRelatedTraumaticInjuryFatalities2010-11.pdf .

- 24.Driscoll T, Mitchell R, Mandryk J, Healey S, Hendrie L, Hull B. Coverage of work related fatalities in Australia by compensation and occupational health and safety agencies. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:195–200. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feyer AM, Williamson AM, Stout N, Driscoll T, Usher H, Langley JD. Comparison of work related fatal injuries in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand: Method and overall findings. Inj Prev. 2001;7:22–8. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spangenberg S, Baarts C, Dyreborg J, Jensen L, Kines P, Mikkelsen KL. Factors contributing to the differences in work related injury rates between Danish and Swedish construction workers. Safety Sci. 2003;41:517–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishikitani M, Yano E. Differences in the lethality of occupational accidents in OECD countries. Safety Sci. 2008;46:1078–90. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorensen OH, Hasle P, Bach E. Working in small enterprises - Is there a special risk? Safety Sci. 2007;45:1044–59. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Legg S, Battisti M, Harris LA, Laird I, Lamm F, Massey C, et al. Occupational Health in Small Businesses. NOHSAC Technical Report 12. Wellington, NOHSAC. 2009. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.dol.govt.nz/publications/nohsac/pdfs/technical-report-12.pdf .

- 30.Borden P, Rees P. Improving the reliability of estimates of migrant worker numbers and their relative risk of workplace injury and illness, Health and Safety Executive, HSE, UK. 2009. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr691.pdf .

- 31.Szczepura A, Gumber A, Clay D, Davies R, Elias P, Johnson M, et al. Review of the occupational health and safety of Britain's ethnic minorities. Sudbury, Suffolk: HSE Books, Health and Safety Executive research report. 2004. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/150/

- 32.The United States Census Bureau, State and County Quick Facts-USA, Census.gov, USA. 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html .

- 33.Ahonen EQ, Benavides FG. Risk of fatal and non-fatal occupational injury in foreign workers in Spain. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:424–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mock C, Adjei S, Acheampong F, Deroo L, Simpson K. Occupational injuries in Ghana. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2005;11:238–45. doi: 10.1179/107735205800246028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barss P, Addley K, Grivna M, Stanculescu C, Abu-Zidan F. Occupational injury in the United Arab Emirates: Epidemiology and prevention. Occup Med (Lond) 2009;597:493–8. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnold CW. The occupational health status of African-American women health care workers. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12:311–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson JC. Exposure to occupational hazards among Hispanics, blacks and non-Hispanic whites in California. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:629–30. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menéndez CK, Havea SA. Temporal patterns in work-related fatalities among foreign-born workers in the USA, 1992-2007. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:954–62. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Rubaee FR, Al-Maniri A. Work related injuries in an oil field in Oman. Oman Med J. 2011;26:315–8. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qatar Information eXchange, Labour Market, Qatar Statistics Authority. 2012. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 20]. Available from: http://www.qix.gov.qa/portal/page/portal/qix/subject_area/Statistics?subject_area=183 .

- 41.Bourdillon F, Lombrail P, Antoni M, Benrekassa J, Bennegadi R, Leloup M, et al. The health of foreign populations in France. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:1219–27. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90036-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cubbin C, Le Clere FB, Smith GS. Socioeconomic status and the occurrence of fatal and nonfatal injury in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:70–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grieco E. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2003. English Abilities of the USA Foreign-Born Population. Migration Information Source. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCracken S, Feyer AM, Langley J, Broughton J, Sporle A. Maori work-related fatal injury, 1985-1994. N Z Med J. 2001;114:395–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]