Abstract

Anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) are causing ocean acidification, lowering seawater aragonite (CaCO3) saturation state (Ωarag), with potentially substantial impacts on marine ecosystems over the 21st Century. Calcifying organisms have exhibited reduced calcification under lower saturation state conditions in aquaria. However, the in situ sensitivity of calcifying ecosystems to future ocean acidification remains unknown. Here we assess the community level sensitivity of calcification to local CO2-induced acidification caused by natural respiration in an unperturbed, biodiverse, temperate intertidal ecosystem. We find that on hourly timescales nighttime community calcification is strongly influenced by Ωarag, with greater net calcium carbonate dissolution under more acidic conditions. Daytime calcification however, is not detectably affected by Ωarag. If the short-term sensitivity of community calcification to Ωarag is representative of the long-term sensitivity to ocean acidification, nighttime dissolution in these intertidal ecosystems could more than double by 2050, with significant ecological and economic consequences.

The oceanic uptake of CO2 has increased due to anthropogenic CO2 emissions1. This process, often referred to as ‘ocean acidification’, has decreased global surface ocean pH by ~0.1 since the preindustrial era2 and is projected to further decrease pH by 0.07 to 0.33 units by 21003. The ongoing reduction of the calcium carbonate saturation state of seawater, contemporaneous with ocean acidification4, is likely to affect the ability of many marine calcifiers to form their calcium carbonate shells or skeletons and is projected to have significant impacts on ocean ecosystems on decadal to millennial timescales5,6.

Calcification rates are a common indicator of individual or ecosystem health7. In laboratory manipulations, many calcifying species, including temperate macroalgae6,8,9 and invertebrates10,11,12, exhibit reduced rates of calcification in response to a reduction in the seawater saturation state. Consequently, in situ observations of the sensitivity of calcifying communities to natural saturation state variability are increasingly valued13, as they incorporate complex species interactions, and capture the carbonate chemistry conditions to which communities are acclimatised. Such analyses may therefore better represent the community level sensitivity to long-term ocean acidification. Studies have typically focused on sites with volcanic CO2 seeps that produce strong spatial gradients in calcium carbonate saturation state13,14. However, an alternative approach has been applied at sites that are isolated from the open ocean during low tides and can therefore experience large temporal (hourly) variability in calcium carbonate saturation state due to localised photosynthesis and respiration15,16. It is this approach that is utilised in this study to investigate the sensitivity of calcifiers to saturation state variability in temperate intertidal ecosystems. The main difference between the two methodologies is that the sensitivity of a community exposed to large short-term variability in carbonate saturation state may differ from that community’s sensitivity to ocean acidification which operates over much longer decadal to centennial timescales. As such, greater care is required when making long-term inferences from temporally isolated study sites.

Here, we assess the community level sensitivity of temperate tide pool calcification rates to variability in the calcium carbonate saturation state. Our intertidal study site at Bodega Marine Reserve in Northern California experiences extreme variation in calcium carbonate saturation state at low tide due to photosynthetic activity and respiration occurring after the time at which the pools become isolated from the open ocean. As photosynthetic activity is largely dependent on temperature and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), which vary on a diurnal timescale, whereas tide pool isolation is predominantly a function of tidal phase, we were able to separate the influence of calcium carbonate saturation state on calcification from the influence of temperature and PAR. This system therefore provides a unique opportunity to characterise the in situ short-timescale sensitivity of tide pool community calcification rates to changes in saturation state.

Results

Tide pool community structure

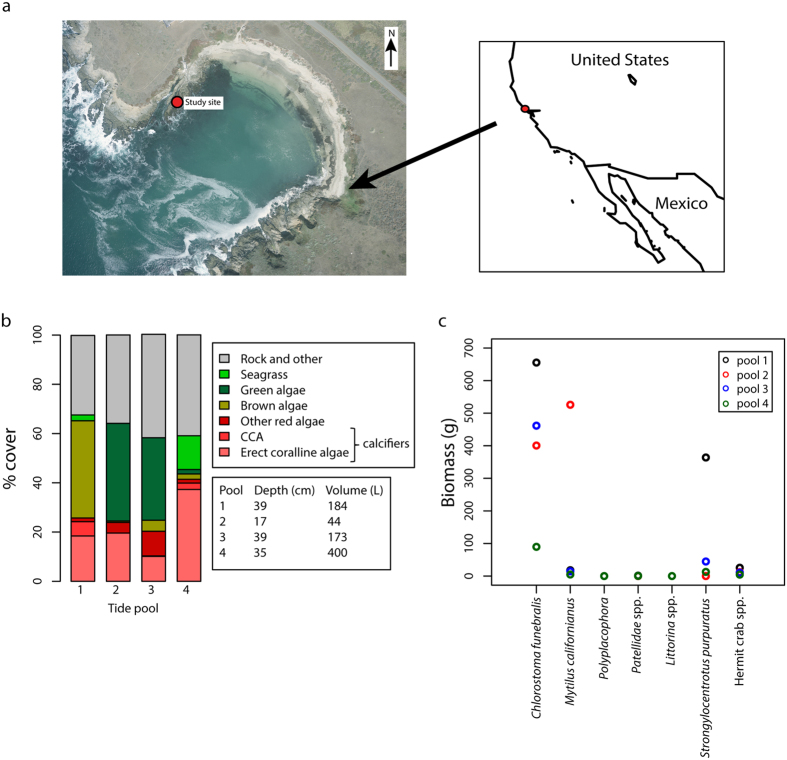

The mean depths, volumes, and community structure of the pools are given in Fig. 1. Mean pool depth varied from 17 cm to 39 cm while pool volume covered the range 44 L to 400 L. The dominant autotrophic calcifiers in the pools were coralline algae (e.g. Corallina vancouveriensis and Calliarthron sp.; 10.1–37.3% benthic cover) and crustose coralline algae (CCA; 0–5.8% benthic cover). The tide pool communities included various non-calcifying red algae (Prionitis sp. and Mastocarpus sp.; 1.5–10% benthic cover), brown algae (e.g. Fucus vesiculosus; 0.6–39.5% benthic cover), green algae (Cladophora sp. and Enteromorpha sp.; 0.04–39.6% benthic cover) and seagrasses (Phyllospadix torreyi.; 0.01–13.7% benthic cover). We note that pools also contained a diverse calcifying invertebrate community, including bivalves (i.e., Mytilus californianus) and gastropods (i.e., Chlorostoma funebralis, Littorina spp., Polyplacophora spp., and limpets). In the majority of pools, the dominant component of calcifying invertebrate biomass was Chlorostoma funebralis (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1. Study site characterisation.

(a) An aerial photo of Horseshoe Cove, Bodega Marine Reserve, California and the location of the tide pool study site on the Northern California coast (38.3°N, 123.1°W), (b) the mean depth, volume and primary producer community cover and (c) the invertebrate community in each of the tide pools. The map is produced using R version 3.0.3 software (https://www.r-project.org/).

Carbonate chemistry

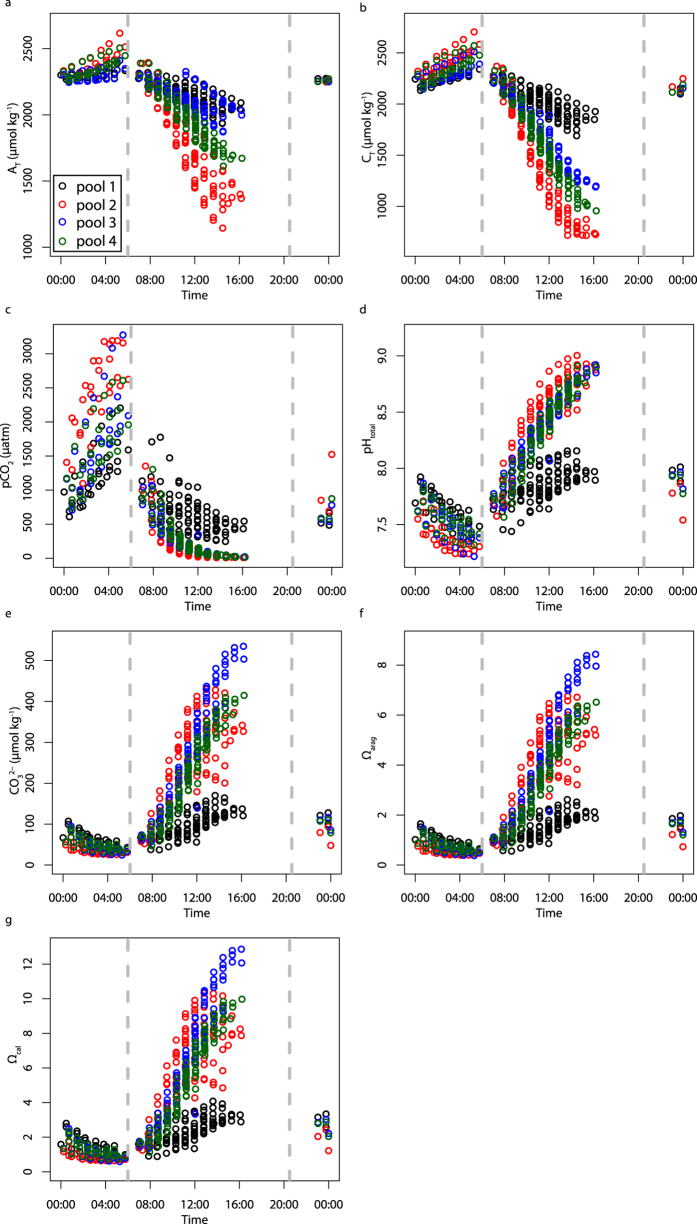

The carbonate chemistry of seawater in the tide pools varied substantially throughout the day in all pools studied (Fig. 2). Total alkalinity (AT) and dissolved inorganic carbon (CT) were highest before sunrise (maximum value of AT = 2616 μmol kg−1; CT = 2512 μmol kg−1) and decreased through the course of the day to minimum values in the late afternoon (minimum value of AT = 1144 μmol kg−1; CT = 715 μmol kg−1). The pCO2 showed similar declines, with a peak pre-sunrise value of 3276μatm and a minimum value of <10 μatm by mid-to-late afternoon. The pH, CO32− and Ωarag all show large concurrent decreases through the night and increases during the day, with pH increasing from a minimum value before sunrise of 7.22 to a maximum late afternoon value of 9.00, and Ωarag increasing through the day from a minimum value of 0.38 before sunrise to a maximum of 8.43. As discussed in greater detail below, the variation in carbonate chemistry parameters can be largely attributed to patterns of calcification, net primary production and changes in tide pool temperature.

Figure 2. Carbonate chemistry parameters.

(a) total alkalinity (AT; μmol kg−1), (b) dissolved inorganic carbon (CT; μmol kg−1), (c) pCO2 (μatm), (d) pH, (e) CO32− concentration (μmol kg−1), (f) aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) and (g) calcite saturation state (Ωcal) against time of day for all experimental time periods in each of the tide pools. Dashed grey lines show the approximate times of sunrise and sunset. Daytime data were collected in 2014 and nighttime data in 2015.

While all four tide pools had broadly similar directional trends in carbonate chemistry parameters throughout the day, the magnitude of these trends shows large differences among pools. These differences are due to tide pool depth and the relative abundance of calcifying and photosynthesising taxa, in addition to the relative exposure of pools to incoming solar radiation. Pool 1, in particular, shows diel ranges in carbonate chemistry parameters of a much lower magnitude than the other pools (Fig. 2). Greater shading from incoming solar radiation and therefore lower pool temperature and PAR levels in Pool 1 may have enhanced the stability of its carbonate chemistry. The magnitude of carbonate chemistry changes in Pools 2, 3 and 4 seems to largely reflect pool depth, with shallower pools characterised by more substrate per pool volume (and thus greater benthic biomass per volume) exhibiting the largest daily reductions in AT and CT (Fig. 2).

Daytime calcification

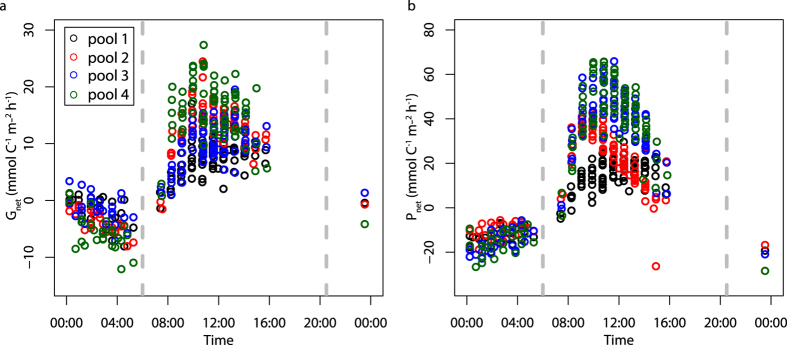

Rates of daytime calcification are predominately positive, indicating net community calcification during daylight hours. Net community calcification (Gnet) shows similar diel trends to net community production (Pnet), with peak rates typically occurring between 11:00 and 13:00 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Temporal cycles in community calcification (Gnet) and production (Pnet).

(a) Gnet (mmol C−1 m−2 h−1) and (b) Pnet (mmol C−1 m−2 h−1) against time of day in each of the tide pools. Dashed grey lines show the approximate times of sunrise and sunset. Daytime data were collected in 2014 and nighttime data in 2015.

In all pools, Gnet is linearly correlated with Pnet (p < 0.05). Gnet is linearly correlated to PAR, achieving statistical significance (p < 0.01) in all pools except for Pool 4 (p = 0.11). This is likely an artefact of the fewer measurements made at low light levels in Pool 4. While linearly correlated, the data suggest that the relationship between Gnet and PAR can be better described by a Michaelis-Menten function with the positive influence of PAR on Gnet saturating at PAR values >1000 μmol m−2 s−1 (Supplementary Fig. S4). Gnet is linearly correlated to temperature (p < 0.05) and Ωarag (p < 0.05) in all pools with the exception of Pool 4.

Pnet, PAR, and a Gaussian function of temperature (Tf) explain 33–71% of the variation in daytime Gnet in the tide pools studied (Table 1). Ωarag offers no additional explanatory power in the prediction of daytime Gnet for any of the tide pools, if variation in Pnet, PAR, and Tf is taken into account (Table 1).

Table 1. Statistical model parameter estimates for daytime and nighttime calcification.

| Pool | Variable | Coefficient | Standard error | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime Calcification | ||||

| 1 | PARmm | 25.74 | 4.00 | 0.34 |

| 2 | Pnet | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.71 |

| PARmm | 8.62 | 1.60 | ||

| Tf | 0.55 | 0.11 | ||

| 3 | PARmm | 25.43 | 4.16 | 0.33 |

| 4 | Pnet | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| Nighttime Calcification | ||||

| 1 | Ωarag | 6.16 | 1.32 | 0.47 |

| Pnet | 0.37 | 0.12 | ||

| 2 | Ωarag | 7.91 | 1.45 | 0.53 |

| 3 | Ωarag | 4.17 | 1.11 | 0.62 |

| Tf | 0.60 | 0.22 | ||

| 4 | Ωarag | 8.70 | 1.66 | 0.53 |

| Pnet | 0.26 | 0.08 | ||

The optimal models of daytime and nighttime net calcification (Gnet) in each of the tide pools. During the night Ωarag is the only potential explanatory variable in the optimal model of each tide pool. However during the day Ωarag is found to offer no additional explanatory power in any of the tide pools. In each model all explanatory variables are significant at the p < 0.01 level.

Nighttime calcification

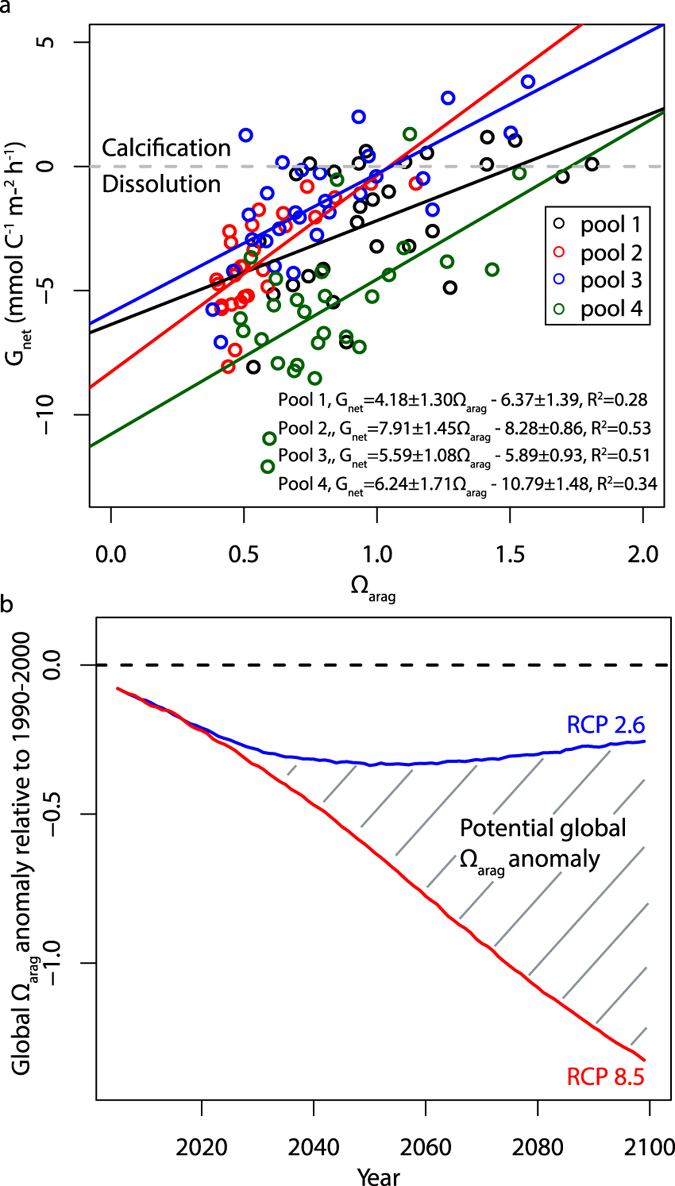

Nighttime community calcification (Gnet) is found to be strongly influenced by Ωarag, with higher nighttime Gnet at higher Ωarag values in all tide pools. This is in contrast to the Ωarag insensitivity described for daytime Gnet. Nighttime Gnet typically occurs at lower Ωarag values (0.38–2.06) than those present during the day (0.56–8.43), and is predominately negative, indicating net CaCO3 dissolution (Fig. 3). Ωarag can explain 28–53% of the variability in nighttime calcification rates (Fig. 4a). Regression analyses indicate that the transition from net calcification to net dissolution occurs at Ωarag values of 1.52, 1.05, 1.05 and 1.73 for Pools 1–4 respectively (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4. Nighttime community calcification and Ωarag sensitivities/projections.

(a) Nighttime Gnet (mmol C−1 m−2 h−1) against aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) in each of the tide pools. Regression lines are significant at the p < 0.05 level. (b) Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) global Ωarag anomalies relative to 1990–2000 mean values for the Representative Concentration Pathways 2.6 (RCP 2.6; blue) and 8.5 (RCP 8.5; red). Ωarag anomalies are multimodel ensemble mean values calculated from 8 CMIP5 models with fully coupled ocean biogeochemistry schemes. RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5 respectively represent the most extreme mitigation and business-as-usual RCP scenarios conducted in CMIP5.

In the absence of other potential explanatory variables temperature was found to explain 20–45% of variability in nighttime Gnet in 3 of the 4 pools (Fig. S6). Pnet is found to only explain 21% of the variability in nighttime Gnet in Pool 2 (Fig. S6) and none of the variability in nighttime Gnet in the other tide pools. Pnet is not present in the optimal nighttime model of Pool 2 (Table 1).

The dominant driver of nighttime Gnet variability is Ωarag, with greater dissolution rates at lower values. Ωarag is the only explanatory variable in the optimal model of calcification in each pool (Table 1) and explains 28 ± 9% of additional variability in nighttime Gnet that is unaccounted for by Pnet and Tf. In total 47–62% of the variability in nighttime Gnet can be explained by Ωarag, Pnet and Tf. Ωarag has a coefficient of 6.16 ± 1.32, 7.91 ± 1.45 4.17 ± 1.11, and 8.70 ± 1.66 for Pools 1–4 respectively. As such, the Ωarag sensitivity of nighttime calcification is broadly indistinguishable between tide pools although Pool 3 is less sensitive to Ωarag variability than Pools 2 and 4.

Discussion

The finding that Ωarag offers no additional explanatory power in the prediction of daytime Gnet, if variation in Pnet, PAR, and temperature is taken into account (Table 1), suggests that at least in the short-term, daytime net calcification rates of intertidal communities are resilient to a very broad range of Ωarag values (0.56–8.43). Daytime calcification rates could exhibit some dependency on Ωarag as has been shown for individual species in laboratory manipulations that encompass a similar Ωarag range10,12,17 but due to multicollinearity between Ωarag and other potential explanatory variables such as PAR, this dependence may not be detectable in situ18,19. Such dependency however is highly unlikely given that the multicollinearity between explanatory variables is weak in our study (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

The positive correlations between Gnet and Pnet during the daytime imply that calcification and photosynthesis are intimately linked in these tide pools. This suggests that photosynthesis could enhance calcification processes during daylight hours20,21 and promote greater calcification resilience to variability in Ωarag. In the intertidal communities studied here, photosynthetic calcifiers (i.e., calcifying algae) may have a larger influence on carbonate chemistry dynamics than non-photosynthetic calcifying species, such as molluscs, during daylight hours. While we did not assess the extent to which individual taxa contribute to net community calcification in the tide pools, our results allow for predictions about the vulnerability of net daytime community calcification to variability in Ωarag across a range of community compositions.

As shown in Fig. 4b, the decline of global mean Ωarag as projected by an ensemble of current-generation Earth System Models, is highly dependent on the economic and environmental pathway taken. Under a business-as-usual scenario (RCP 8.5), global mean Ωarag is projected to decline by 1.32 by the year 2100, relative to global mean Ωarag in 1990–2000. Even under an extremely ambitious pathway aimed to limit global mean temperature rise to 2 °C (RCP 2.6), which assumes full participation in emission reductions by all countries, and the possibility of negative emissions22, Ωarag is still expected to decline by up to 0.33 throughout the 21st Century, relative to 1990–2000 mean Ωarag. Although the extent to which global declines in Ωarag are reflected in intertidal zones will vary regionally and be mediated by local processes23, it is apparent that projected declines in Ωarag are considerably smaller than our measured diel variability due to photosynthesis and respiration. The impact of ocean acidification in intertidal ecosystems will therefore be a consequence of the sensitivity of communities already exposed to a wide Ωarag range experiencing a relatively smaller decline in mean background Ωarag24.

The statistical models derived for nighttime calcification all contain Ωarag, with Pnet and a Gaussian function of temperature (Tf) found to offer additional explanatory power in certain tide pools. Ωarag coefficients in these models are between 4.17 ± 1.11 and 8.70 ± 1.66 depending on the tide pool. Therefore, a decline in background Ωarag values of 0.5, which is highly likely by 2050 under even optimistic scenarios of future climate change (Fig. 4b)4,25, would reduce nighttime calcification (increase nighttime dissolution) by approximately 2.09–4.35 mmol C−1 m−2 h−1. Given that we measure mean nighttime calcification rates of −3.24 mmol C−1 m−2 h−1, this represents a decline in net community calcification of approximately 65–134% based on the statistical relationships derived in our experiment. It should be noted that our in-situ methodology does not distinguish between organism and sediment CaCO3 dissolution. Therefore additional controlled lab and mesocosm studies are required to isolate the biotic community sensitivity to Ωarag variability and demonstrate that it does not significantly differ from the aggregate community sensitivity observed in situ.

Our estimates of the sensitivity of intertidal communities to Ωarag responses recorded on hourly time scales only partially reflect the potential long-term response of ecosystems to decadal to millennial scale changes brought about by anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. Indeed, the sensitivity of intertidal organisms to Ωarag in manipulative experiments has been shown to exhibit dependence on experimental duration26,27 and therefore the short-term Ωarag sensitivity of the communities characterised here may differ from their long-term sensitivity to ocean acidification. Moreover, the overall impacts of ocean acidification and declining Ωarag on temperate calcifiers will be more diverse and extend beyond the processes we evaluated, including potential impacts on survival and reproduction7. Nonetheless, if the short-term sensitivity of community calcification to Ωarag conditions ranging from 0.38 to 8.43 described here is representative of the long-term sensitivity of these intertidal communities to ocean acidification, then one would expect daytime net calcification rates to be relatively resilient to future Ωarag declines. Nighttime net calcification rates however, would be expected to decline, reducing the long-term community calcification of these ecosystems, with important ecological and economic ramifications.

Materials and Methods

Oceanographic and geochemical measurements

Our study site consisted of 4 rocky tide pools located in Horseshoe Cove, Bodega Marine Reserve, California (38.3°N, 123.1°W; Fig. 1). Over 5 sampling periods in April, May and June 2014, and May and June 2015, instruments were deployed in each of the tide pools over low tide periods (~7 hours, during which the pools were isolated from the open ocean). The sampling periods in 2014 occurred during daylight hours, while the sampling periods in 2015 occurred at night. The influence of interannual variability on comparisons between the 2014 and 2015 datasets is assumed to be minimal. This is supported by the agreement between 2014 and 2015 carbonate chemistry measurements in the crepuscular periods. Monthly differences between the PAR levels at a given time of day were minimal once periods with overcast conditions are taken account of. We utilised conductivity-temperature-depth sensors (CTDs; YSI model 6600 and 6920) to measure pressure, temperature, conductivity, pH, and oxygen at intervals of 2 minutes. When oxygen levels were high and interfered with conductivity measurements, salinity values were estimated from contemporaneous measurements in other tide pools. Water pumps attached to CTDs were used to take 1 L bottle samples every 50 minutes over the course of instrument deployment for discrete geochemical analyses (below). Seawater samples were analysed immediately for alkalinity and pH and preserved with HgCl2 for dissolved inorganic carbon (CT) analysis.

In total, 566 seawater samples were analysed for total alkalinity (AT), pH, dissolved inorganic carbon (CT and nutrients (NO2− + NO3− and NH3 + NH4+). AT was measured using a Metrohm 855 autotitrator. Three replicates of each sample were run, and the mean value of the two closest replicates was used (<2 μmol kg−1 (1SD) instrument precision). Titrant was standardised using reference material supplied by the Dickson Lab (Batch 141). The pH and O2 values measured via CTD were calibrated using spectrophotometric pH measurements and Winkler titrations, respectively, conducted according to best practices28 on discrete water samples. CT was measured by infrared adsorption via a LICOR7000 CO2/H2O analyser coupled with a custom-made sample delivery system built by Stanford University’s Stable Isotope Laboratory (<2 μmol kg−1 (1SD) instrument precision). Nutrients were measured photometrically using a WestCo SmartChem 200 discrete analyser (~0.05 μmol L−1 instrument precision). The pCO2, CO32− and aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) values were calculated with AT and CT for 2014 data, and AT and pH for 2015 data, using the CO2SYS program29. The K1 and K2 constants of Mehrbach et al.30 refit by Dickson and Millero31 were utilised, and total boron was calculated using the B/chlorinity ratio of Uppstrom 197432.

Photosynthetically-active radiation (PAR) data were provided by the Bodega Ocean Observing Node, University of California, Bodega Marine Laboratory (http://bml.ucdavis.edu/boon/index.html). This record is measured within 100 m of the tide pools and is representative of local conditions. However, we note that local topography, water depth, and turbidity are additional influences on the direct PAR that tide pool communities received during the sample collection periods.

Quantification of tide pool volume and community composition

Tide pool volumes were measured by draining each of the 4 tide pools and measuring the volume of drained water. The species composition and community structure of each pool was measured by overlaying a flexible mesh net with 10 × 10cm grid cells over the bottom of the emptied tide pool. The percent cover of all autotropic species and key functional groups was estimated on a 0 to 4 scale in each grid cell, with 0 denoting absence, 1 = 25%, 2 = 50%, 3 = 75%, and 4 = 100% cover for each taxa. The numerical values were then summed to estimate the total percent cover of each taxa within a tide pool. Invertebrate biomass values were estimated by weighing a representative sample of each taxa.

Net community calcification and production

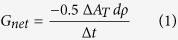

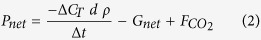

Net community calcification (Gnet; mmol C−1 m−2 h−1) was calculated in each tide pool using the salinity-normalised alkalinity anomaly method28:

|

where ΔAT is the change in salinity-normalised AT (μmol kg−1), d is the mean tide pool depth (m), ρ is the density of sea water (kg m−3)33 and Δt is the time period (h). Net community production (photosynthesis minus respiration; Pnet; mmol C−1 m−2 h−1) is calculated as:

|

where ΔCT is the change in salinity normalised CT (μmol kg−1) and  (μmol kg−1 m−2 h−1) is the air-sea flux of CO2 calculated using the wind speed-dependent gas transfer function of Ho et al. 200634, the temperature and salinity dependent solubility of CO2 according to Weiss 197435 and an atmospheric CO2 concentration of 401 ppm and 403 ppm for the 2014 and 2015 sampling periods respectively (the NOAA/ESRL Mauna Loa mean CO2 concentration over the sampling periods). Wind speed data were provided by the Bodega Ocean Observing Node, University of California, Bodega Marine Laboratory.

(μmol kg−1 m−2 h−1) is the air-sea flux of CO2 calculated using the wind speed-dependent gas transfer function of Ho et al. 200634, the temperature and salinity dependent solubility of CO2 according to Weiss 197435 and an atmospheric CO2 concentration of 401 ppm and 403 ppm for the 2014 and 2015 sampling periods respectively (the NOAA/ESRL Mauna Loa mean CO2 concentration over the sampling periods). Wind speed data were provided by the Bodega Ocean Observing Node, University of California, Bodega Marine Laboratory.

Statistical modelling

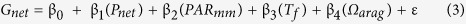

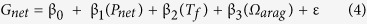

Linear least square regression models were used to determine the influence of Pnet, PAR, temperature, and Ωarag on the rate of community calcification (Gnet). Such an approach has been previously adopted in tropical environments (e.g. 16,36). Statistical issues involving multicollinearity between potential explanatory variables was assessed using Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs), which were all less than 6.5 (Supplementary Table S1). Model selection was based on minimising model AIC values with PAR-dependency assumed to follow a Michaelis-Menten function20 and temperature dependency assumed to follow a Gaussian function37 (Supplementary Fig. S4). The use of these functions as opposed to linear PAR and temperature relationships improved the explanatory power of models across tide pools. Thus, for each tide pool:

|

where Ωarag is the mean of the omega aragonite values measured in two consecutive sampling times, PARmm is a Michaelis-Menten function of the mean PAR between two consecutive sampling times and Tf is a Gaussian function of the mean temperature between two consecutive sampling times. PARmm and Tf are derived separately for each tide pool from Gnet-PAR and Gnet-temperature relationships respectively (Supplementary Fig. S4). Note that equation 3 simplifies to the following for statistical models of nighttime calcification rates:

|

Ωarag projections

Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) global mean Ωarag values are 2005–2100 annual anomalies calculated relative to the 1990–2000 mean values of the respective model. Values are GLobal Ocean Data Analysis Project (GLODAP)38, corrected and averaged across a multi-model ensemble of 8 CMIP5 Earth System Models which ran fully coupled ocean biogeochemistry schemes (CanESM2, GFDL-ESM2G, GFDL-ESM2M, IPSL-CM5A-LR, IPSL-CM5A-MR, MIROC-ESM, MPI-ESM-LR, MPI-ESM-MR). Ωarag anomalies are given for the Representative Concentration Pathways 2.6 and 8.539. RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5 respectively represent the most extreme mitigation and business-as-usual RCP scenarios conducted in CMIP5 and are therefore considered to encompass the range of future potential Ωarag values.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kwiatkowski, L. et al. Nighttime dissolution in a temperate coastal ocean ecosystem increases under acidification. Sci. Rep. 6, 22984; doi: 10.1038/srep22984 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank S. Shayegh, Brittany Jellison and D. Ross for fieldwork assistance, J. Orr for assistance with data processing, D. Mucciarone and D. Koweek for assistance with DIC measurements and E. Sanford and R. Albright for helpful insight. This work was funded by the Carnegie Institution for Science, UC Multicampus Research Initiatives and Programs and National Science Foundation (OCE 1220648 and OCE 1255194).

Footnotes

Author Contributions L.K., K.C., B.G. and T.H. conceived and designed the experiment. L.K., J.H., K.J.K., Y.N., A.N., A.R., E.B.R. and M.S. conducted sample analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript text.

References

- Doney S. C., Fabry V. J., Feely R. A. & Kleypas J. A. Ocean Acidification: The Other CO2 Problem. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 1, 169–192 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira K. & Wickett M. E. Oceanography: Anthropogenic carbon and ocean pH. Nature 425, 365–365 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp L. et al. Multiple stressors of ocean ecosystems in the 21st century: projections with CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 10, 6225–6245 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ricke K. L., Orr J. C., Schneider K. & Caldeira K. Risks to coral reefs from ocean carbonate chemistry changes in recent earth system model projections. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 034003 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Orr J. C. et al. Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 437, 681–686 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony K. R. N., Kline D. I., Diaz-Pulido G., Dove S. & Hoegh-Guldberg O. Ocean acidification causes bleaching and productivity loss in coral reef builders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 17442–17446 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker K. J. et al. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 1884–1896 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K. et al. Calcification in the articulated coralline alga Corallina pilulifera, with special reference to the effect of elevated CO2 concentration. Mar. Biol. 117, 129–132 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Jokiel P. L. et al. Ocean acidification and calcifying reef organisms: a mesocosm investigation. Coral Reefs 27, 473–483 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Gazeau F. et al. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine shelled molluscs. Mar. Biol. 160, 2207–2245 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Waldbusser G. G. et al. A developmental and energetic basis linking larval oyster shell formation to acidification sensitivity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2171–2176 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Waldbusser G. G. et al. Saturation-state sensitivity of marine bivalve larvae to ocean acidification. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 273–280 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Spencer J. M. et al. Volcanic carbon dioxide vents show ecosystem effects of ocean acidification. Nature 454, 96–99 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius K. E. et al. Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 165–169 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. et al. Carbon turnover rates in the One Tree Island reef: A 40-year perspective. J. Geophys. Res. 117 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Shaw E. C., Phinn S. R., Tilbrook B. & Steven A. Natural in situ relationships suggest coral reef calcium carbonate production will decline with ocean acidification. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 777–788 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Waldbusser G. G., Bergschneider H. & Green M. A. Size-dependent pH effect on calcification in post-larval hard clam Mercenaria spp. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 417, 171–182 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Andersson A. J. & Gledhill D. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs: Effects on Breakdown, Dissolution, and Net Ecosystem Calcification. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 5, 321–348 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokiel P. L., Jury C. P. & Rodgers K. S. Coral-algae metabolism and diurnal changes in the CO2-carbonate system of bulk sea water. PeerJ 2, e378 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubini F., Barnett H., Langdon C. & Atkinson M. J. Dependence of calcification on light and carbonate ion concentration for the hermatypic coral Porites compressa. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 220, 153–162 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Langdon C. et al. Effect of calcium carbonate saturation state on the calcification rate of an experimental coral reef. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 639–654 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. et al. Twenty-First-Century Compatible CO2 Emissions and Airborne Fraction Simulated by CMIP5 Earth System Models under Four Representative Concentration Pathways. J. Clim. 26, 4398–4413 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Andersson A. J., Yeakel K. L., Bates N. R. & de Putron S. J. Partial offsets in ocean acidification from changing coral reef biogeochemistry. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 56–61 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord B. et al. Ocean acidification through the lens of ecological theory. Ecology 96, 3–15 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski L., Cox P., Halloran P. R., Mumby P. J. & Wiltshire A. J. Coral bleaching under unconventional scenarios of climate warming and ocean acidification. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 777–781 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Ragazzola F. et al. Ocean acidification weakens the structural integrity of coralline algae. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 2804–2812 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragazzola F. et al. Phenotypic plasticity of coralline algae in a High CO2 world. Ecol. Evol. 3, 3436–3446 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riebesell U., Fabry V. J., Hansson L. & Gattuso J.-P. Guide to best practices for ocean acidification research and data reporting. 260 (Publications Office of the European Union, 2010).

- Lewis E. & Wallace D. W. R. Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations. (1998).

- Mehrbach C., Culberson C. H., Hawley J. E. & Pytkowicx R. M. Measurement of the apparent dissociation constants of carbonic acid in seawater at atmospheric pressure. Limnol. Oceanogr. 18, 897–907 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- Dickson A. G. & Millero F. J. A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep Sea Res. Part Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 34, 1733–1743 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Uppström L. R. The boron/chlorinity ratio of deep-sea water from the Pacific Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Oceanogr. Abstr. 21, 161–162 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Millero F. J. & Poisson A. International one-atmosphere equation of state of seawater. Deep Sea Res. Part Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 28, 625–629 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Ho D. T. et al. Measurements of air-sea gas exchange at high wind speeds in the Southern Ocean: Implications for global parameterizations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L16611 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R. F. Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: the solubility of a non-ideal gas. Mar. Chem. 2, 203–215 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Albright R., Benthuysen J., Cantin N., Caldeira K. & Anthony K. Coral reef metabolism and carbon chemistry dynamics of a coral reef flat. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 2015GL063488 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Marshall A. T. & Clode P. Calcification rate and the effect of temperature in a zooxanthellate and an azooxanthellate scleractinian reef coral. Coral Reefs 23, 218–224 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Key R. M. et al. A global ocean carbon climatology: Results from Global Data Analysis Project (GLODAP). Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 18, GB4031 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Vuuren D. et al. The representative concentration pathways: an overview. Clim. Change 109, 5–31 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.