Abstract

Is nucleotide exchange sufficient to activate K-Ras4B? To signal, oncogenic rat sarcoma (Ras) anchors in the membrane and recruits effectors by exposing its effector lobe. With the use of NMR and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we observed that in solution, farnesylated guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP)-bound K-Ras4B is predominantly autoinhibited by its hypervariable region (HVR), whereas the GTP-bound state favors an activated, HVR-released state. On the anionic membrane, the catalytic domain adopts multiple orientations, including parallel (∼180°) and perpendicular (∼90°) alignments of the allosteric helices, with respect to the membrane surface direction. In the autoinhibited state, the HVR is sandwiched between the effector lobe and the membrane; in the active state, with membrane-anchored farnesyl and unrestrained HVR, the catalytic domain fluctuates reinlessly, exposing its effector-binding site. Dimerization and clustering can reduce the fluctuations. This achieves preorganized, productive conformations. Notably, we also observe HVR-autoinhibited K-Ras4B-GTP states, with GDP-bound-like orientations of the helices. Thus, we propose that the GDP/GTP exchange may not be sufficient for activation; instead, our results suggest that the GDP/GTP exchange, HVR sequestration, farnesyl insertion, and orientation/localization of the catalytic domain at the membrane conjointly determine the active or inactive state of K-Ras4B. Importantly, K-Ras4B-GTP can exist in active and inactive states; on its own, GTP binding may not compel K-Ras4B activation.—Jang, H., Banerjee, A., Chavan, T. S, Lu, S., Zhang, J., Gaponenko, V., Nussinov, R. The higher level of complexity of K-Ras4B activation at the membrane.

Keywords: KRAS, GDP/GTP exchange, farnesyl insertion, signaling, phospholipids

Ras is a small guanosine triphosphatase, controlling signal transduction pathways and promoting cell proliferation and survival (1, 2). Kirsten Ras viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) is a frequently mutated oncogene in Ras-driven cancers (3). The Ras family includes splice variants of KRAS (KRAS4A, KRAS4B), HRAS, and NRAS. Their catalytic domains (residues 1–166) share highly homologous sequences and structures but not their flexible C-terminal HVRs (residues 167–188/189). Apart from different HVR sequences, Ras isoforms are distinguished by their HVR post-translational modification (PTM) prenylation, methylation, and acylation states (4). HVR lipidations promote Ras anchoring in the plasma membrane (5, 6). In addition to a single farnesyl prenylation, which is common in all Ras isoforms, there are 2 palmitoyl acylations in the HVR of H-Ras (7) and 1 single palmitoyl in the HVR of N-Ras and K-Ras4A. With no palmitoylation, K-Ras4B HVR is unique. Furthermore, unlike other Ras isoforms, K-Ras4B HVR is polybasic. With half of its residues as positively charged Lys, it could overcome the palmitoylation deficiency that allows it to target specific membrane mircodomains (8). The different lipidation states act to locate Ras isoforms preferentially at different membrane microdomains (9, 10) and modulate isoform-specific functional pathways (11).

Cascading signals of GTP-bound Ras stimulate cell proliferation and growth through the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways (12–14). Ras/Ras-related protein is another major signaling axis in cancer (15). Regulation of Ras downstream signals requires membrane localization, which promotes specific recruitment and activation of effector kinases. The frequencies of oncogenic Ras isoforms differ across cancer/tissue types (3), pointing to effector-selective states across isoforms at the membrane surface. However, how Ras localizes and orients on the plasma membrane, what are the preferred states, and how these relate to Ras active/inactive population, signaling, and effector selectivity are still important open questions in Ras biology. Computational studies on isolated HVR lipid anchors (residues 180–186 for H-Ras and N-Ras and residues 175–185 for K-Ras4B) were able to delineate the complexity of Ras-membrane interactions (16–18). Prenylated HVRs of Ras isoforms drive specific membrane anchoring. The K-Ras4B HVR (residues 167–185) preferentially binds the membrane in the liquid phase and spontaneously inserts the farnesyl moiety into the loosely packed phospholipid bilayers (19). Phosphorylation at S181 and the phosphomimetic S181D mutant prevent spontaneous membrane insertion of the farnesyl (19). Simulations of HVRs with the lipid anchor portions and with full sequence provided useful insight into the peptide-membrane interactions in atomic detail and highlighted the next essential step of modeling full-length Ras in the membrane. Membrane-interacting, full-length H-RasG12V molecules were modeled in a 1,2-dimyristoylglycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) bilayer (20). Depending on the nucleotide types, 2 distinct models were proposed. In the first, H-Ras-GTP is in a parallel orientation to the bilayer surface, with α4 and α5 helices in direct contact with the bilayer and H-Ras-GDP in an orientation perpendicular to the bilayer surface, with the β2–β3 loop interacting with lipids (20). With the use of the same computational protocol as for H-RasG12V, simulations of K-Ras4BG12V showed that the K-Ras HVR stably anchored in the DMPC bilayer with distinct orientations of the catalytic domain compared with the H-Ras case (21). In both GTP- and GDP-bound states of the K-Ras, the catalytic domain exhibited similar membrane orientations; helix α4 does not stably contact the membrane in both states. In contrast to the active H-Ras with its membrane orientation stabilized by helix α4, K-Ras4BG12V was stabilized by the HVR (21). These isoform-specific membrane orientations may determine effector selectivity and recruitment rate. Taken together, even though through modeling efforts, mechanistic details of membrane interactions for the H-Ras and K-Ras mutants have emerged, conformational ensembles representing the diversity of Ras functional roles when associated with the membrane and insight into their differential actions are still limited.

With the use of extensive MD simulations, we studied full-length, post-translationally modified wild-type K-Ras4B in solution and on an anionic lipid bilayer composed of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine:1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (DOPC:DOPS; mole ratio 4:1). NMR predicted the farnesyl-binding interfaces on the catalytic domain. Exploiting these, we investigated the nucleotide-dependent roles of the farnesylated HVR in the conformational dynamics of K-Ras4B in different environments aiming to elucidate the consequences for K-Ras4B activation and signaling. In our previous studies, we observed that in solution, the nonfarnesylated C-terminal HVR of GDP-bound K-Ras4B directly interacts with the catalytic domain, yielding an autoinhibited form of K-Ras4B (22). The binding interfaces of the HVR overlapped the binding site of the effectors. The HVR autoinhibition tends to be released in the GTP-bound state. The HVR presents looser interaction with the catalytic domain, exposing the active-site region. Here, we observe that the farnesylated HVR of K-Ras4B-GDP reflects the autoinhibited state in solution. The diverse farnesyl interactions with the catalytic domain reveal binding interfaces located in a wide area across the effector lobe surface, consistent with the NMR observations. When on the membrane, K-Ras4B exhibits distinct interaction modes with lipids. Importantly, we also observe a similar pattern of behavior for some conformers of the K-Ras4B-GTP-bound state, with the HVR covering the effector-binding lobe. In the inactive K-Ras4B states of both GDP/GTP, the axes of the allosteric helices are perpendicular to the bilayer normal. In contrast, in the active, HVR-released, K-Ras4B-GTP-bound state, the allosteric helices are aligned in parallel to the bilayer normal.

Taken together, we propose that in GTP-bound K-Ras4B, the HVR-capped effector-binding site corresponds to an inactive state. We believe that this HVR-autoinhibited conformation, which is highly populated in the GDP—but also populated on the membrane by GTP-bound states—plays a significant role in the determination of the functional state of K-Ras4B; that is, we suggest a scenario where a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF)-catalyzed nucleotide exchange may lead to a GTP-bound, inactive state. The binding to the membrane (or an effector) may trigger a population shift toward the active state exposing the binding site and switching the catalytic domain orientation.

Importantly, for the GTP-bound catalytic domain, we observed 2 states—active and inactive—with the inactive the more populated state. Oncogenic mutations at G12, G13, and Q61 shifted the equilibrium toward the active state (23). Thus, the HVR not only anchors Ras in the membrane; it also plays a key regulatory role in deciding the K-Ras4B signaling state on the membrane. The emerging mechanism for K-Ras4B activation advocates not only GDP/GTP nucleotide exchange; GTP-bound states may still be inactive. Instead, it reasons that complex mechanisms and competing catalytic domain/lipid interactions, including HVR sequestration, farnesyl insertion, and orientation and localization of the catalytic domain on the membrane, act in concert to determine the functional state of K-Ras4B, regardless of the type of nucleotide binding. Notably, even when K-Ras4B-GDP autoinhibition is released, the lipids can still inhibit the effector lobe. Our composite model emphasizes a higher level of complexity of K-Ras4B activation than believed to date.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NMR experiments

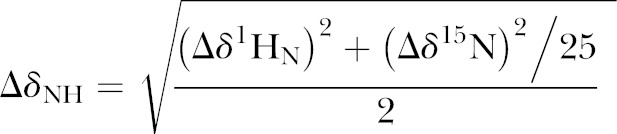

We previously published a semisynthetic method for production of farnesylated and methylated K-Ras4B (24). A modification of this method was used here. The alterations made to the protein sequence were as described previously (24). In addition, cysteine residues 118 and 80 were mutated to serines. Cys51 was left intact, as it is inaccessible to solvent (25). The S-farnesyl-l-cysteine methyl ester in 100% DMSO was reacted with 2 mg no-weigh sulfosuccinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate. The reaction product was dissolved thoroughly so as to dissolve the entire sulfosuccnimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxylate. 50 µl of 50% (w/v) of N-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside was added to the above solution, preceded by 381 μl of phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and 1 μl of 50 mM di-tert-amyl peroxide (DTAP). This reaction mixture was incubated for 1.5 h followed by dilution to a final volume of 8 ml with phosphate buffer. The solution was then centrifuged at 3000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then discarded and pellet was dissolved in 150 μl of 100% ethanol. After an overnight reaction at room temperature, the protein was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-citrate, pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM 2-ME. The modification of K-Ras4B was verified by mass spectrometry. Before NMR experiments, 10% 2H2O was added to the samples. To record 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR spectra of unmodified or farnesylated and methylated K-Ras4B, we used 900 Mhz and 600 Mhz Avance spectrometers (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA), equipped with cryogenic probes. The NMR experiments were conducted at a temperature of 25°C. NMRPipe software (26) was used for processing and analyzing the data. The chemical shift assignments were taken from the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB) database (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu) by use of the 17785 and 18529 BMRB identification numbers. The assignments for the HVR were made by use of HNCA, HNCACB, and CBCACOHN experiments. The mean chemical shift difference was calculated as follows:

|

Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) higher than the sum of the average and 1 sd were considered to be statistically significant.

Membrane fractions

U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) 3T3 fibroblasts were grown to 90% confluence at 37°C under the 5% CO2 atmosphere in DMEM media (Life Technologies–Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies–Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies–Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cells were harvested by scraping and lysed in a sucrose-based lysis buffer [150 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM Na3Vo4, 1 mM NaF, and 1 protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA)] by sonication. The nuclear fraction was removed by centrifugation at 15,300 g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in PBS in the presence of 0.01% Triton X-100.

Raf-1 Ras-binding domain-binding assay

K-Ras4B1–188 wild-type G12D and G12V mutants, with a polyhistidine tag at the C-terminal, were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as published previously (24). Bl 21 AI cells (Life Technologies–Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for the protein preps. The protein expression was induced after the cell cultures reached an optical density of 0.6–0.8, with a final isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside concentration of 0.2 mM, and grown at 18°C with shaking for 24 h. The purified samples against the nucleotide exchange buffer contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM 2-ME. After dialysis, the protein solutions were incubated at 30°C for 30 min with the addition of 20 μl 0.5 M EDTA/ml and GTP, to a final concentration of 1 mM. The nucleotide exchange reaction was stopped by addition of 32.5 μl/ml 2 M MgCl2. The extent of GTP loading was determined by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry to be >90%. The GTP-loaded protein samples were used in the Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase (Raf-1) Ras-binding domain (RBD) assay, following the manufacturer’s instructions (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Raf-1 RBD agarose beads (5 μl) were added to 10 µM protein in the presence of membrane from the membrane fraction (containing 30 μg total membrane-associated protein). This mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight. The beads were washed 3 times with the lysis buffer, provided by the manufacturer, and pelleted by centrifugation at 15,300 g at 4°C for 30 s. The same procedure was also followed in the absence of the membranes. Next, 40 μl 2× Laemmli-reducing sample buffer was added to the beads, followed by boiling at 95°C for 5 min and addition of 2 μl 1 M DTT to facilitate further the release of Ras from the beads. An SDS-PAGE was performed, followed by blotting the proteins onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed for Ras by use of the antihistidine primary antibody, followed by the anti-mouse secondary antibody. Both antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA).

Generating initial configurations of K-Ras4B

Nonfarnesylated wild-type K-Ras4B1–185 proteins were constructed previously by use of 2 crystal structures (PDB Codes 4EPT and 3GFT) (22). In the construction, the covalently attached HVR was folded onto the catalytic domain based on the NMR CSP data by use of interactive MD (27) in a molecular visualization program (28) with the nanoscale MD (NAMD) (29) code. Four different initial configurations for each GDP- and GTP-bound state were created. Then, PTMs were implemented by adding the farnesyl to the Cys185 side-chain and the methylated C-terminus to the carboxyl group. A molecular topology was created for the farnesyl by use of the Avogadro software (30). Parameters, including partial charges, bond lengths, angles, and torsional angles for the atoms in the farnesyl group, were calculated by use of the Gaussian 09 program (31) on a Biowulf cluster at NIH. The calculated parameters can be adopted directly in the Chemistry at Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics (CHARMM) (32) program.

Atomistic MD simulations

The initial configurations of K-Ras4B were subject to simulations in water and membrane environments. For the water simulations, the initial configurations were solvated by the modified TIP3P water model (33) and gradually relaxed with the proteins held rigid. The unit cell box of 121 Å3 contains almost 180,000 atoms, 50 Na+, 4 Mg2+, and 62 Cl− for the GDP-bound and 61 Cl− for the GTP-bound K-Ras4B. For the membrane simulations, the same initial configurations of K-Ras4B for the water simulations were modeled on the surface of an anionic lipid bilayer containing DOPC:DOPS (mole ratio 4:1). Initial contacts of K-Ras4B with the bilayer were determined by the NMR CSP data of K-Ras4B binding to nanodiscs (22). In the GDP-bound state, nanodiscs induced chemical shift changes in the effector lobe and the N-terminal portion of the HVR. In the GTP-bound state, the C-terminal portion of the HVR predominantly experienced the CSPs. In the initial modeling, no portion of the protein, including the HVR and the farnesyl group, was inserted into the lipid bilayer before the start of the simulations, ensuring that only the HVR backbone marginally touched the surface of the bilayer at the starting points. Lipid bilayers were generated by use of the bilayer-building protocol involving dynamics of pseudospheres through the van der Waals force field (34, 35). This method was exploited extensively to generate various lipid bilayer systems for MD simulations (36–54). For DOPC and DOPS, the cross-sectional area per lipid and the headgroup distance across the bilayer are 72.4 Å2 and 36.7 Å and 65.3 Å2 and 38.4 Å at 30°C, respectively (55, 56). With a choice for the number of lipid molecules, the optimal value for lateral cell dimensions can be determined. A unit cell containing a total of 300 lipids constitutes the bilayer with TIP3P waters, added at both sides with a lipid/water ratio of ∼1/120. The updated CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids (C36) (57) and the modified TIP3P water model (33) were used to construct the set of starting points and to relax the systems to a production-ready stage. To neutralize the system and also to obtain a salt concentration near 100 mM, 60 Na+, 5 Mg2+, and 14 Cl− for the GDP-bound and 13 Cl− for the GTP-bound K-Ras4B were added to the bilayer systems.

In the pre-equilibrium stages, a series of minimization and dynamics cycles were performed with the harmonically restrained K-Ras4B proteins. At the final pre-equilibrium stage, the protein was relaxed gradually by removing the harmonic restraints through dynamic cycles with the full Ewald electrostatics calculation that was adapted to the surrounding heat bath. In the production runs of 200 ns, the Langevin temperature control was used to maintain the constant temperature at 310 K. Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston pressure control was used to sustain the pressure at 1 atm. For the water simulations, we used the constant number of atoms, pressure, and temperature (NPT) ensemble. The membrane simulations used the constant number of atoms, pressure, surface area, and temperature ensemble with constant surface area and with a constant normal pressure applied in the direction perpendicular to the membrane in the production runs to 30 ns, and then the simulations switched to the NPT ensemble from the NPAT ensemble in the production runs from 30 to 200 ns. We used the NAMD parallel-computing code (29) for the production runs on a Biowulf cluster at NIH. Averages were taken after 30 ns, discarding initial transients trajectories, with the CHARMM programming package (32).

RESULTS

PTMs of K-Ras4B-GDP contribute to HVR binding to the catalytic domain

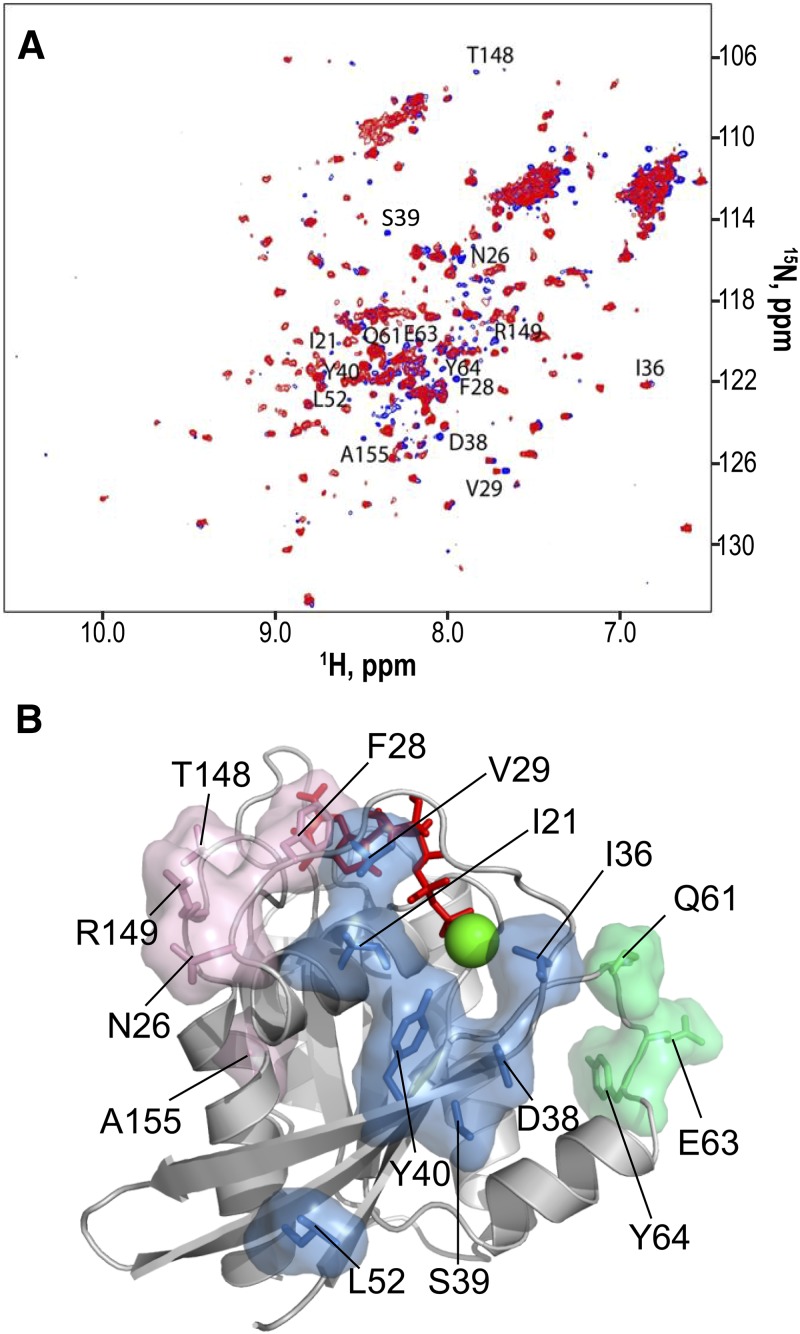

We previously found that nonfarnesylated K-Ras4B HVR interacts extensively with the catalytic domain when the protein is GDP loaded and that the HVR interaction with the catalytic domain is dismissed when the protein is GTP loaded (22). However, PTMs on Cys185, with the prenylated side-chain, may alter the interaction of the HVR with the catalytic domain. To validate our previous observations, we compared the 15N HSQC NMR spectra of K-Ras4B-GDP and fully processed K-Ras4B-GDP (Fig. 1A). We observed significant CSPs in the Switch I, Switch II, and G5 loop regions (see the Ras sequence and domain structure shown in Supplemental Fig. 1), caused by the farnesylated HVR. These highly perturbed residues resulted from the contribution of the atomic interaction between the farnesyl and the catalytic domain. The catalytic domain residues, interacting with the farnesyl, are widely dispersed. However, these residues are clustered and can be grouped into 3 distinct regions: region 1 (I21, V29, I36, D38, S39, Y40, L52), region 2 (Q61, E63, Y64), and region 3 (N26, F28, T148, R149, A155; Fig. 1B). The farnesyl-binding sites are mainly located at the effector lobe of K-Ras4B, consistent with the nonfarnesylated HVR-binding sites. For the GTP-bound state, however, our previous experiments did not reveal significant chemical shift changes caused by the HVR, suggesting that K-Ras4B-GTP tends to release the autoinhibition by the HVR and allow membrane binding (unpublished results).

Figure 1.

NMR CSPs of residues in K-Ras4B-GDP by the farnesyl and their mapping onto a crystal structure. A) Superimpositions of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 0.28 mM K-Ras4B-GDP with the PTMs (red) and 0.28 mM K-Ras4B-GDP with the non-PTMs (blue). Examples of CSPs as a result of farnesyl and methyl groups are marked. B) Mapping of the perturbed residues on the structure of the GDP-bound K-Ras4B catalytic domain. In the structure, residues with high CSPs are marked. The CSP residues are grouped; region 1 (blue surface; I21, V29, I36, D38, S39, Y40, L52), region 2 (green surface; Q61, E63, Y64), and region 3 (pink surface; N26, F28, T148, R149, A155).

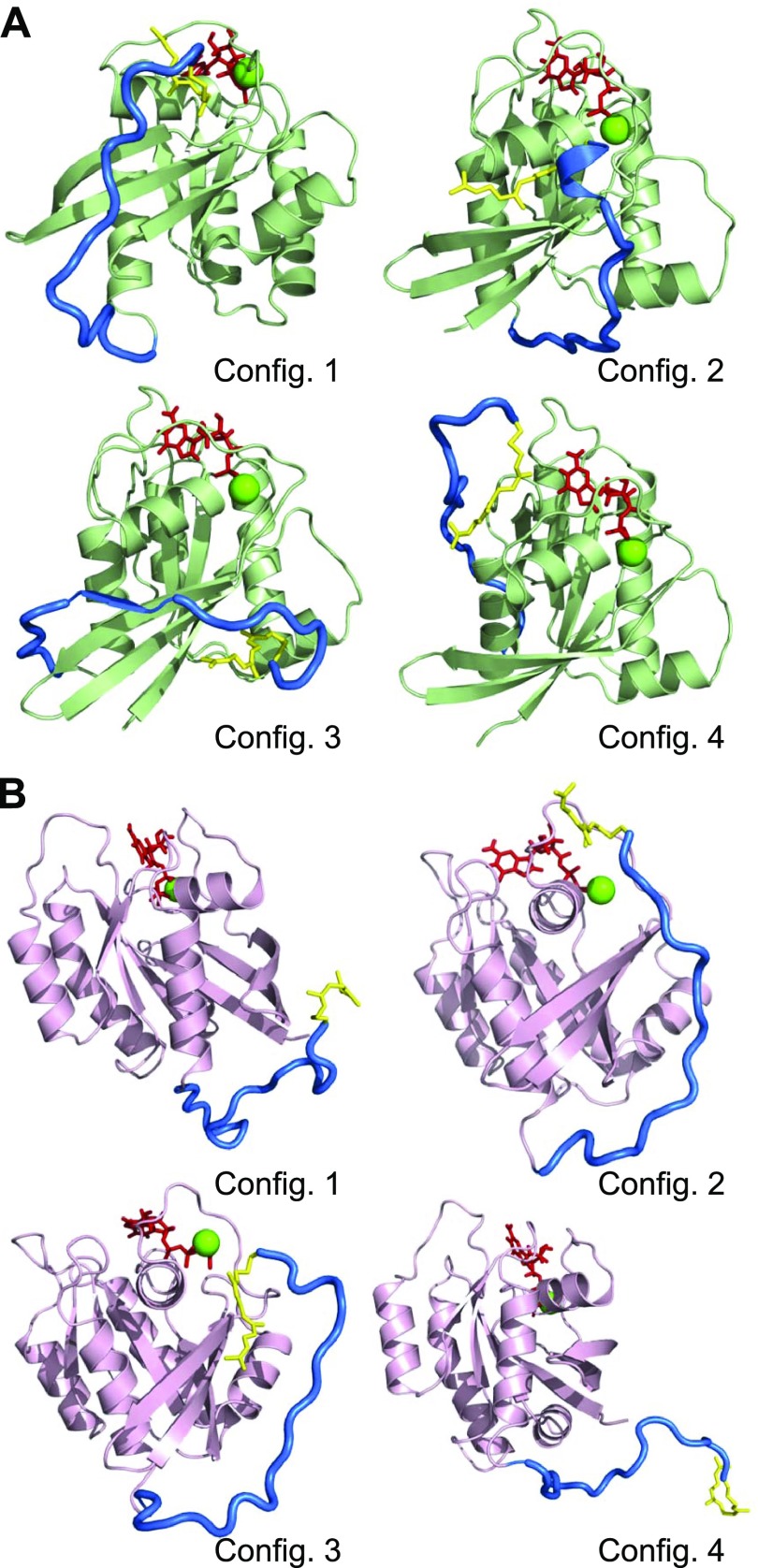

To obtain structural details of the farnesylated K-Ras4B in solution, we performed MD simulations on K-Ras4B in an aqueous environment. To render all possible ensembles from the NMR observations for the farnesylated HVR interaction with the catalytic domain, we generated 4 independent, initial configurations for each Ras state as the starting points in the simulations. In the GDP-bound state, we observed that the farnesylated HVR is sequestered by the catalytic domain (Fig. 2A). In the HVRs, transient α-helical and extended β-sheet secondary structures can be observed for configurations 2 and 3 of K-Ras4B-GDP, respectively. For configurations 1, 2, and 3, the HVRs bind tightly to the effector lobe, covering the binding site of the effectors (such as Raf and PI3K) at the Switch I and β2 regions. The buried effector-binding site by the HVR suggests that K-Ras4B-GDP is autoinhibited by the HVR, which can be lifted when the HVR locates at the allosteric lobe, as in configuration 4 of K-Ras4B-GDP. In K-Ras4B-GDP, the farnesyl can be located at different regions of the catalytic domain, consistent with the NMR ensembles (Fig. 1). For configurations 1 and 2 of K-Ras4B-GDP, the farnesyl is located at region 1. For configurations 3 and 4, it is located at regions 2 and 3, respectively. However, in the GTP-bound state, 2 out of 4 configurations still retain the farnesyl on the catalytic domain. In configurations 2 and 3 of K-Ras4B-GTP, the farnesyls are located at region 1, with the HVR marginally interacting with the catalytic domain (Fig. 2B). For configurations 1 and 4 of K-Ras4B-GTP, the farnesylated HVR is released from the catalytic domain. To quantify the HVR interaction, we calculated the interaction energies of the catalytic domain with the HVR and the farnesyl separately (Supplemental Fig. 2A, C). In K-Ras4B-GDP, the interaction of farnesylated HVR with the catalytic domain is slightly stronger compared with the GTP-bound state. Compared with the HVR-catalytic domain interaction, the farnesyl-catalytic domain interaction can be negligible, almost 20-fold weaker. The strong interactions of the HVR with the catalytic domain are attributed to the involvement of electrostatic attractions between the lysines in the polybasic region (residues 175–180) and the negatively charged residues, E37 and D38, in Switch I and E62 and E63 in Switch II. Formation of secondary structure in the HVR of configurations 2 and 3 further stabilizes the HVR interaction, causing strong attraction toward the catalytic domain. However, K-Ras4B-GTP tends to release the HVR from the catalytic domain, exposing the effector-binding site. The tendencies to release the autoinhibition by the HVR in some of the K-Ras4B-GTP states suggest that the GTP-bound conformational ensembles are more populated in the functional state than the GDP bound. However, not all GTP-bound states release the inhibition, as shown by configurations 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Snapshots representing relaxed structures of K-Ras4B with the PTMs in the aqueous environment for the GDP-bound (A) and GTP-bound (B) states. Cartoons for the catalytic domains are shown in green and pink for the GDP- and GTP-bound states, respectively. The HVR in the tube representation is blue, and the farnesyl as a stick is yellow. In the catalytic domain, the red sticks and green spheres represent the nucleotide and Mg2+ ions, respectively. Config., configuration.

To observe the effects of HVR autoinhibition on protein dynamics, we calculated the cross-correlation of the atomic fluctuations obtained from the simulations and presented them in a 3-dimensional (3D) dynamical cross-correlation map (DCCM; Fig. 3). Positively correlated residues, moving in the same direction, yield a correlation coefficient C(i,j) → 1, whereas anticorrelated (negatively correlated) residues, moving in the opposite direction, yield a correlation coefficient C(i,j) → −1. As the HVR mainly interacts with the effector lobe of the catalytic domain, the allosteric lobe does not directly involve the HVR interaction. However, we observed that the HVR sequestration by the effector lobe significantly affects the motions of the helices in the allosteric lobe. As indicated in Fig. 2, the HVRs in configurations 1–3 of K-Ras4B-GDP tightly bound the effector lobe. In the GTP-bound molecule, the HVRs marginally bound the effector lobe in configurations 2 and 3. These configurations can be regarded as in the autoinhibition state, with the HVR bound to the effector lobe. Remarkably, for the autoinhibited K-Ras4B proteins, the helix-to-helix motions (α3-α4, α3-α5, and α4-α5) are uncorrelated. On the other hand, when the HVR did not bind the effector lobe, the motions of the helices are highly correlated, as in configuration 4 of K-Ras4B-GDP and configurations 1 and 4 of K-Ras4B-GTP. For the HVR-unbound state, highly correlated motions across the residues in K-Ras4B are apparent (Supplemental Fig. 2B, D), suggesting that the HVR autoinhibition freezes the conformational dynamics in K-Ras4B. Without the HVR, the catalytic domain of K-Ras4B also exhibits frozen motions in the conformational dynamics across the residues (Supplemental Fig. 2E, F).

Figure 3.

3D DCCM of the helix-to-helix motions, including α3-α4, α3-α5, and α4-α5 helices in the allosteric lobe for the GDP-bound (A) and GTP-bound K-Ras4B (B) in the aqueous environment. Positively correlated residues with correlation coefficient C(i,j) = 0.6 (red); anticorrelated (negatively correlated) residues with C(i,j) = −0.6 (dark purple); and uncorrelated residues with C(i,j) = 0 (dark green) are shown.

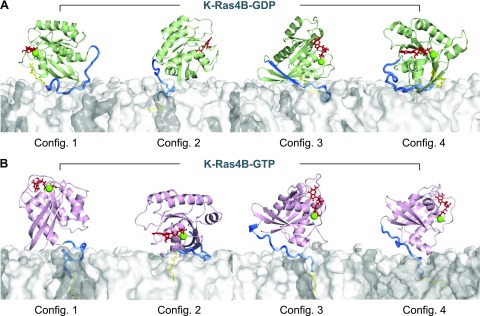

The HVR mediates distinct conformational states of membrane-bound K-Ras4B

To observe the impact of the autoinhibition by the HVR in the presence of membrane phospholipids, we simulated K-Ras4B with the PTMs on the surface of an anionic lipid bilayer composed of DOPC:DOPS (mole ratio 4:1). In the initial model constructions, we used the same initial configurations as used in the water simulations (as in Fig. 2), arranging the polybasic region of the HVR facing toward the surface of the lipid bilayer. It is reasonable that the positively charged HVR preferentially interacts with the anionic lipid bilayer. Four different initial configurations for each GDP- and GTP-bound state ensure that any portion of the protein, including the HVR and the farnesyl group, was not inserted into the lipid bilayer before the start of the simulations. During the simulation, we observed that the autoinhibition state by the HVR, as observed in the water environment, was altered significantly in the presence of lipids (Fig. 4). In the GDP-bound state, the HVR autoinhibition can be observed in configurations 1, 3, and 4, whereas the HVR is released from the effector lobe in configuration 2. In the GTP-bound state, the HVR still binds the effector lobe in configuration 2, retaining the autoinhibition state, whereas other configurations release the HVR from the catalytic domain. For the GDP-bound state, the autoinhibition state occurs in a similar way, with 3 out of 4 configurations autoinhibited in water and lipid environments. In contrast, lipids release the HVR autoinhibition in K-Ras4B-GTP, but 1 out of the 4 configurations is autoinhibited in the lipid environment. In the autoinhibited state, the catalytic domain competes with lipids for the interaction with the farnesylated HVR. To shift toward the functional state, K-Ras4B needs to abolish the HVR autoinhibition. However, even the elimination of the HVR autoinhibition does not implicate K-Ras4B in the functional state. For example, although K-Ras4B-GDP in configuration 2 removed the HVR autoinhibition, the lipids inhibited the effector lobe. The functional state of K-Ras4B can be determined by spontaneous membrane insertion of the farnesyl group and proper orientations of the catalytic domain, which expose the effector-binding site. In the functional state of K-Ras4B, the farnesylated HVR solely interacts with the lipid bilayer, whereas the catalytic domain is reluctant to interact with the HVR and lipids, suggesting that the HVR is a significant factor in the mechanism of membrane activation of K-Ras4B.

Figure 4.

Snapshots representing relaxed structures of K-Ras4B with the PTMs on the anionic lipid bilayer composed of DOPC:DOPS (mole ratio 4:1) for the GDP-bound (A) and GTP-bound (B) states. Cartoons for the catalytic domains are shown in green and pink for the GDP- and GTP-bound states, respectively. The HVR in the tube representation is blue, and the farnesyl as a stick is yellow. In the catalytic domain, the red sticks and green spheres represent the nucleotide and Mg2+ ions, respectively. For the lipid bilayer, white surface denotes DOPC, and gray surface represents DOPS.

To observe the correlated motions of the residues as a function of the HVR autoinhibition in the lipid environment, we calculated the cross-correlation of the atomic fluctuations obtained from the simulations (Supplemental Fig. 3A, C). Highly correlated residues, with positive [C(i,j) → 1] and negative [C(i,j) → −1] correlations, are apparent in configuration 2 of K-Ras4B-GDP and in configurations 1, 3, and 4 of K-Ras4B-GTP. It can be obviously seen that these configurations released the HVR autoinhibition from the effector lobe (Fig. 4). In contrast, configurations in the HVR-autoinhibited state yield uncorrelated residue motions with C(i,j) → 0, suggesting that the HVR sequestration by the effector lobe significantly constrains the protein dynamics with reduced residue motions. This also includes the helix-to-helix motions in the allosteric lobe. Rugged surfaces in the 3D DCCM represent the highly correlated helix-to-helix motions, mainly observed in the GTP-bound state with the HVR not bound to the effector lobe (Fig. 5). The effector lobe, especially Switch I and II regions, where the HVR binds, significantly affects the motions of entire residues across the allosteric lobe (Supplemental Fig. 3B, D). Large, residual fluctuations of the Switch I and II regions in the HVR-unbound states accentuate the highly correlated motions of the residues (Supplemental Fig. 4A, D). We expect that the dynamic motions of residues in the allosteric lobe are responsible for the functional K-Ras4B dimer formation with the helical interface (58) that induces the Raf dimer formation in the MAPK pathway and possibly interaction with other Ras effectors.

Figure 5.

3D DCCM of the helix-to-helix motions, including α3-α4, α3-α5, and α4-α5 helices in the allosteric lobe for the GDP-bound (A) and GTP-bound K-Ras4B (B) on the lipid bilayer. Positively correlated residues with correlation coefficient C(i,j) = 0.6 (red); anticorrelated (negatively correlated) residues with C(i,j) = −0.6 (dark purple); and uncorrelated residues with C(i,j) = 0 (dark green) are shown.

Composite interactions of the HVR with the surrounding environments determine the K-Ras4B functional state

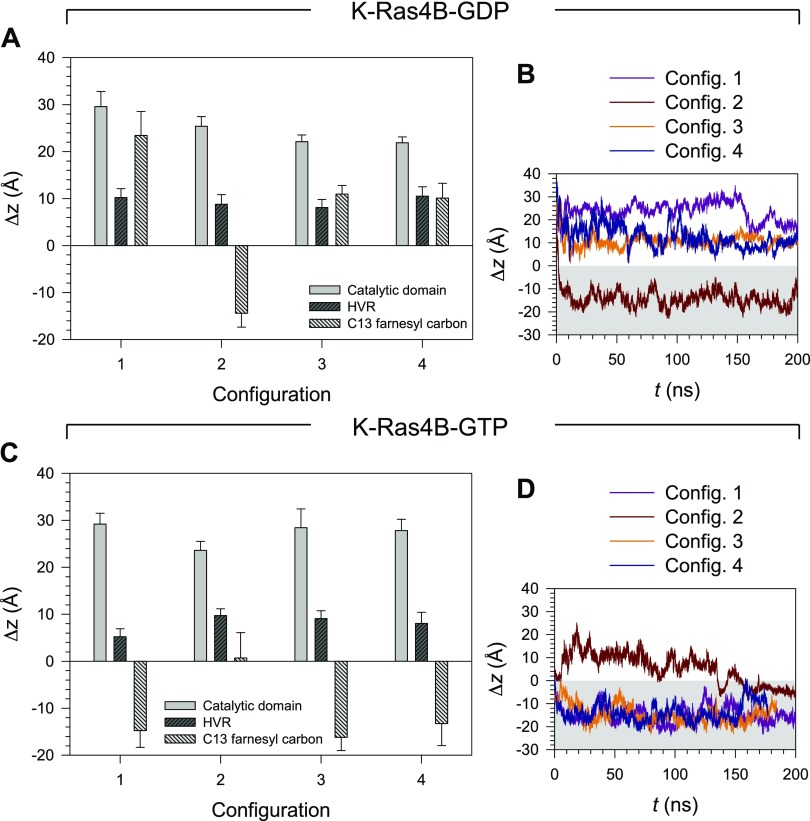

To quantify the K-Ras4B membrane localization as a function of the nucleotide types, we measured separately the deviations of the center of mass location from the bilayer surface for the catalytic domain, the HVR, and the farnesyl terminus (Fig. 6). Lower deviations from the bilayer surface for the catalytic domain in the GDP-bound state compared with the GTP-bound state suggest that K-Ras4B-GDP locates slightly toward the membrane surface. In contrast, the HVR is slightly elevated from the bilayer surface in the GDP bound. This decreases the lipid-accessible surface area in the configurations (Supplemental Fig. 4B, E). For the farnesyl, the negative deviation represents a spontaneous insertion of the farnesyl group into the lipid bilayer. In the GDP-bound state, only configuration 2 inserts the farnesyl, whereas all configurations of K-Ras4B-GTP insert the farnesyl into the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer. In the GTP-bound state, although for configuration 2-spontaneous farnesyl insertion occurred late in the simulation time, at t ∼160 ns, it occurred in <2 ns for the other configurations (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

The deviation (Δz) from the bilayer surface for the center of mass of selected domains of K-Ras4B. A) Time average of Δz from the bilayer surface for the center of mass of the catalytic domain, HVR, and farnesyl terminus for the GDP-bound state. B) Time series (t) of Δz for the farnesyl terminus for the GDP-bound state. C, D) The same time average (C) and time series (D) of Δz for the GTP-bound state.

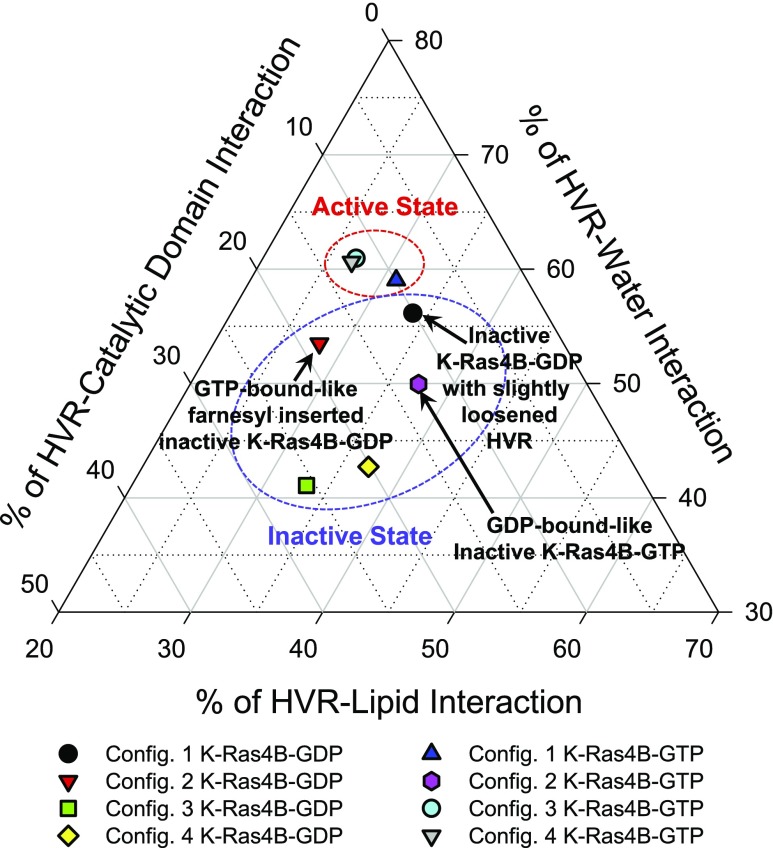

We expect that the protein conformations in configurations 1, 3, and 4 of K-Ras4B-GTP represent an active form K-Ras4B in the membrane. Configuration 2 of K-Ras4B-GTP yields a GDP-like behavior, representing an inactive form of K-Ras4B. Although it spontaneously inserts the farnesyl into the bilayer, the effector lobe is buried by the HVR (Fig. 4). Competing interactions of the HVR with the surrounding environments, including its own catalytic domain, lipids, and water, can determine the functional state of K-Ras4B (Fig. 7). In the active state, K-Ras4B inserts its farnesyl spontaneously into the bilayer and productively exposes the effector lobe to recruit the effectors. In contrast, the protein conformations in all configurations of K-Ras4B-GDP represent an inactive form of K-Ras4B in the membrane. Although configuration 2 of K-Ras4B-GDP spontaneously inserts the farnesyl into the bilayer, the effector lobe is still inaccessible as a result of the bilayer (Fig. 4). In the inactive state, the HVR is sandwiched between the effector lobe and the lipid bilayer, burying the effector lobe. Consequently, the catalytic domain in the inactive state configurations strongly interacts with the HVR, the farnesyl, and lipids compared with the active-state configurations (Supplemental Fig. 4C, F). Strong interactions of the catalytic domain with lipids indicate closer contacts with the bilayer surface (Fig. 6). For configuration 1 of K-Ras4B-GDP, the N-terminal portion of the HVR is slightly loosened from the catalytic domain, but the C-terminal portion of the HVR, including the farnesyl, interacts strongly with the catalytic domain. The HVR provides a tight interaction with lipids as a result of strong electrostatic attraction between the positively charged Lys residues and the anionic lipids. The HVR-lipid interaction is highly dynamic and depends on the distribution of the anionic lipids on the bilayer surface during the simulations.

Figure 7.

Interaction map representing the percentage of K-Ras4B HVR interactions with surrounding environments, including its own catalytic domain, lipid, and water. The interaction energies of each HVR with the catalytic domain, lipid, and water are calculated and then averaged over the time.

Proper membrane orientations of K-Ras4B are important for effector recruitment

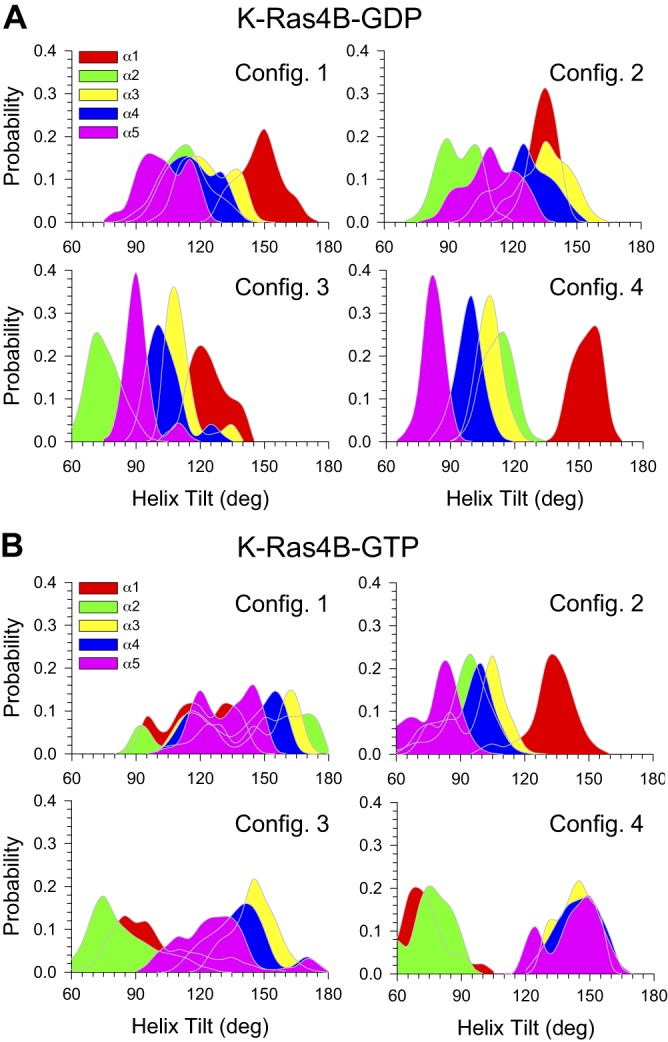

Ras proteins contain 5 α-helices (α1–α5). Two helices—α1 and α2—are in the effector lobe, whereas the other 3 are located in the allosteric lobe. The axes of the allosteric helices are almost parallel to each other but almost perpendicular to the effector helices. Thus, these helices are good probes to determine the protein orientation in the lipid bilayer. We calculated the helix tilt angle (θ) with respect to the bilayer normal. Depending on the direction of the helix axis, θ ∼90° indicates that the helix axis lies on a plain of the bilayer surface, whereas θ ∼0° or θ ∼180° indicates that the helix axis is parallel to the bilayer normal. For configurations 3 and 4 of K-Ras4B-GDP, which are the most representative of the inactive K-Ras4B, the sharp peaks in the probability distributions of the helix tilt suggest that the protein motion is constrained by the competing interaction of the catalytic domain/HVR/lipids (Fig. 8A). The θs for helices α3, α4, and α5 are close to 90° (Table 1), indicating that the helix axis is aligned perpendicular to the bilayer normal. Likewise, inactive-state helix orientations can be observed (59). In this orientation, the Raf-binding effector region is buried, facing the bilayer surface (Fig. 4). Configurations 1 and 2 of K-Ras4B-GDP are also in the inactive state as a result of the inaccessibility of the Raf-binding effector region. For configurations 1, 3, and 4 of K-Ras4B-GTP, which are the most representative of the active K-Ras4B, the catalytic domain reorients, aligning the axes of the allosteric helices parallel to the bilayer normal (Fig. 8B and Table 1). The Raf-binding effector region is clearly accessible (Fig. 4). Wide probability distributions of the helix tilt reflect the dynamic motions of the helices, as observed in the DCCM for the highly correlated motions (Fig. 5B). Configuration 2 of K-Ras4B-GTP behaves like the inactive GDP-bound state, showing inaccessible Raf-binding effector region as a result of the perpendicular alignment of the allosteric helices to the bilayer normal, even when the farnesyl inserts spontaneously into the bilayer. This suggests that composite mechanisms, including the HVR sequestration, the farnesyl insertion, and orientation and localization of the catalytic domain on the membrane, can determine the functional state of K-Ras4B, regardless of the types of nucleotide binding.

Figure 8.

Probability distribution functions for helix θ, with respect to the bilayer normal for the effector lobe helices—α1 and α2—and the allosteric lobe helices—α3, α4, and α5—for the GDP-bound (A) and GTP-bound K-Ras4B (B). The helix tilt was calculated for the angle between 2 vectors formed by the helix axis and normal axis of the bilayer.

TABLE 1.

Helix θ with respect to the membrane normal for the GDP- and GTP-bound K-Ras4B interacting with the anionic lipid bilayer composed of DOPC:DOPS (4:1 mole ratio)

| K-Ras4B | Helix | Helix θ (deg) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Config. 1 | Config. 2 | Config. 3 | Config. 4 | ||

| GDP bound | α1 | 147.7 ± 10.1 | 134.3 ± 6.2 | 128.8 ± 8.8 | 153.7 ± 6.4 |

| α2 | 112.9 ± 11.5 | 94.7 ± 9.2 | 75.2 ± 7.8 | 112.1 ± 7.2 | |

| α3 | 123.5 ± 11.3 | 135.7 ± 11.1 | 110.8 ± 8.0 | 108.2 ± 5.8 | |

| α4 | 116.1 ± 11.4 | 125.3 ± 12.3 | 103.6 ± 8.8 | 98.6 ± 6.1 | |

| α5 | 103.1 ± 11.0 | 109.9 ± 12.1 | 91.3 ± 7.1 | 81.9 ± 5.0 | |

| GTP bound | α1 | 118.7 ± 15.2 | 132.7 ± 10.6 | 99.0 ± 20.2 | 70.9 ± 11.7 |

| α2 | 139.9 ± 27.8 | 93.4 ± 10.4 | 83.6 ± 15.1 | 75.8 ± 9.6 | |

| α3 | 139.6 ± 21.1 | 97.6 ± 13.2 | 145.0 ± 10.3 | 143.1 ± 8.5 | |

| α4 | 137.3 ± 18.1 | 92.4 ± 12.4 | 138.7 ± 14.3 | 144.5 ± 9.8 | |

| α5 | 132.0 ± 12.8 | 76.7 ± 12.1 | 127.3 ± 17.7 | 142.1 ± 12.2 | |

Config., configuration.

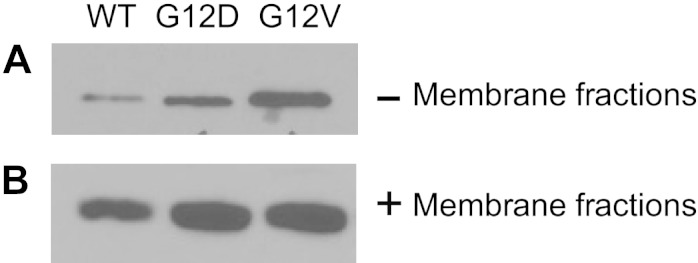

To test the model, we used the Raf-1 RBD-binding assay, performed in the presence and absence of membrane fractions, prepared from NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. We compared the ability of the same (10 µM) concentrations of full-length, GTP-bound wild-type and oncogenic G12D and G12V K-Ras4B to interact with Raf-1 RBD (Fig. 9). The G12D mutant was selected, as it is known to adopt a specific orientation on phospholipid bilayers (59). The wild-type and G12V oncogenic mutant proteins were chosen for comparison with G12D K-Ras4B. In the absence of membrane lipids, G12V K-Ras4B interacted with Raf-1 RBD with the highest affinity. G12D K-Ras4B bound Raf-1 RBD more efficiently than wild-type K-Ras4B but with lower affinity than G12V K-Ras4B. In the presence of membrane lipids, G12D K-Ras4B and G12V K-Ras4B interacted with Raf-1 RBD equally well. In both cases, the oncogenic mutants were more efficient Raf-1 RBD binders than wild-type K-Ras4B. The fact that G12D K-Ras4B-GTP changed its affinity for Raf-1 RBD in the presence of membrane lipids is in agreement with the MD simulations and suggests that orientation on the membrane bilayer plays an important role in activation of K-Ras4B.

Figure 9.

Comparison of effector-binding activity of GTP-bound wild-type, G12D, and G12V K-Ras4B1–188 by use of Raf-1 RBD-binding assay in the absence (A) and presence (B) of membrane fractions prepared from NIH 3T3 fibroblasts.

DISCUSSION

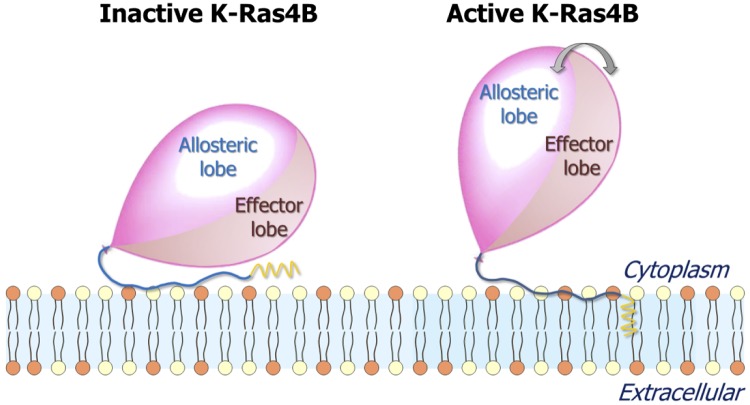

The functional state of K-Ras4B is determined by the nucleotide type, which is loaded onto the catalytic domains, GDP or GTP. Classically, when bound to GDP, K-Ras4B is inactive; when GTP bound, it is active. Here, however, we observe that on its own, GTP binding may not spell an active conformation, and conversely, GDP binding does not necessarily imply an inactive conformation. Significantly, our results indicate that the HVR modulates the orientation and interactions of the catalytic domain with the membrane lipids, thereby contributing to the determination of the active (or inactive) state. Regardless of the nucleotide that is bound, in the active state, the effector-binding site is exposed; in the inactive state, it is buried by the membrane-interacting HVR, thus unavailable to effector binding (Fig. 10). Thus, importantly, beyond the specific loaded nucleotide, the membrane plays a critical role in deciding the functional state. In solution, K-Ras4B-GDP is generally autoinhibited by its farnesylated HVR; however, when the GDP is exchanged by GTP, the autoinhibition tends to be freed. In contrast, at the membrane, composite interactions of the farnesylated HVR with the catalytic domain, the lipids, and water reconfigure the conformational and thus, functional states of K-Ras4B. Irrespective of whether the K-Ras4B is GDP or GTP loaded, the HVR can adopt autoinhibited conformations similar to those typically observed in GDP-bound K-Ras4B in solution (Fig. 10, left). In this K-Ras4B-inactive, membrane-bound mode, the HVR covers the effector lobe, hauling the effector-binding site to the membrane surface. In contrast, the typical conformations of membrane-bound, active K-Ras4B show that the catalytic domain liberates the HVR, which reorients itself to expose the effector lobe (Fig. 10, right). Although the inactive form of K-Ras4B with the HVR autoinhibition is populated in the GDP-bound state, K-Ras4B-GDP can shift to the active state. We observed that the inactive, GDP-bound K-Ras4B protein also exhibited the GTP-bound-like, spontaneous farnesyl insertion, and vice versa, GTP-bound K-Ras4B protein exhibited the GDP-bound-like, HVR-autoinhibited, inactive state. The autoinhibited K-Ras4B-GDP inserts the farnesyl to a lesser extent. The GDP-bound Ras is activated by GEFs, replacing GDP by GTP (60). HVR release from the catalytic domain and spontaneous slipping of the farnesyl group into the lipid bilayer are prerequisites to function.

Figure 10.

Diagrams representing the inactive (left) and active (right) states of K-Ras4B at the anionic membrane. The balloon represents the K-Ras4B catalytic domain, the blue thread tied to the balloon represents the HVR, and the yellow sawtooth represents the farnesyl. In the inactive state, the membrane-interacting HVR hauls the effector lobe to the membrane surface, burying the effector-binding site. In the active state, the catalytic domain liberates the HVR, exposing the effector-binding site and fluctuating reinlessly.

Our studies suggest a new paradigm for K-Ras4B oncogenic activity. They posit that even though GEF is the major actor determining the functional state, GEF is not the sole actor. GEF can activate the autoinhibited form of K-Ras4B to a lesser extent than its activation of the catalytic domain of K-Ras4B (22). The modes of the HVR interactions with the membrane and the catalytic domain are also important. Other Ras isoforms may represent alternative isoform-specific HVR modulations, as the HVRs are highly unique and significantly differ from each other, and the membrane composition that they favor differs as well. Therapeutically, this new understanding needs to be considered, although whether or how it may affect current approaches is still unclear.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous support from the American Cancer Society (Grant RGS-09-057-01-GMC) and the U.S. National Institutes of Health [NIH; Grants R01 CA135341, R01 CA188427 (National Cancer Institute), and R21 HL118588 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute); to V.G.]. This project has been funded, in whole or in part, with federal funds from the NIH Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, under Contract HHSN261200800001E. This research was supported, in part, by the NIH Intramural Research Program, Frederick National Lab, Center for Cancer Research. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. All simulations had been performed with the use of the high-performance computational facilities of the Biowulf PC/Linux cluster at the NIH (https://hpc.nih.gov/). H.J. and A.B. are co-first authors.

Glossary

- BMRB

Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank

- CHARMM

Chemistry at Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics

- CSP

chemical shift perturbation

- DCCM

dynamical cross-correlation map

- DMPC

1,2-dimyristoylglycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOPC

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOPS

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine

- GDP

guanosine 5'-diphosphate

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- HVR

hypervariable region

- MD

molecular dynamics

- NAMD

nanoscale molecular dynamics

- NIH

U.S. National Institutes of Health

- NPT

constant number of atoms, pressure, and temperature

- PTM

post-translational modification

- Ras

rat sarcoma

- Raf-1

Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase

- RBD

rat sarcoma-binding domain

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karnoub A. E., Weinberg R. A. (2008) Ras oncogenes: split personalities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 517–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherfils J., Zeghouf M. (2013) Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol. Rev. 93, 269–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prior I. A., Lewis P. D., Mattos C. (2012) A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 72, 2457–2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahearn I. M., Haigis K., Bar-Sagi D., Philips M. R. (2012) Regulating the regulator: post-translational modification of RAS. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 39–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunsveld L., Waldmann H., Huster D. (2009) Membrane binding of lipidated Ras peptides and proteins—the structural point of view. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 273–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai F. D., Lopes M. S., Zhou M., Court H., Ponce O., Fiordalisi J. J., Gierut J. J., Cox A. D., Haigis K. M., Philips M. R. (2015) K-Ras4A splice variant is widely expressed in cancer and uses a hybrid membrane-targeting motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 779–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laude A. J., Prior I. A. (2008) Palmitoylation and localisation of RAS isoforms are modulated by the hypervariable linker domain. J. Cell Sci. 121, 421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hancock J. F., Paterson H., Marshall C. J. (1990) A polybasic domain or palmitoylation is required in addition to the CAAX motif to localize p21ras to the plasma membrane. Cell 63, 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy S., Luetterforst R., Harding A., Apolloni A., Etheridge M., Stang E., Rolls B., Hancock J. F., Parton R. G. (1999) Dominant-negative caveolin inhibits H-Ras function by disrupting cholesterol-rich plasma membrane domains. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 98–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright L. P., Philips M. R. (2006) Thematic review series: lipid posttranslational modifications. CAAX modification and membrane targeting of Ras. J. Lipid Res. 47, 883–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castellano E., Santos E. (2011) Functional specificity of ras isoforms: so similar but so different. Genes Cancer 2, 216–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennan D. F., Dar A. C., Hertz N. T., Chao W. C., Burlingame A. L., Shokat K. M., Barford D. (2011) A Raf-induced allosteric transition of KSR stimulates phosphorylation of MEK. Nature 472, 366–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castellano E., Downward J. (2011) RAS interaction with PI3K: more than just another effector pathway. Genes Cancer 2, 261–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mor A., Philips M. R. (2006) Compartmentalized Ras/MAPK signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24, 771–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guin S., Theodorescu D. (2015) The RAS-RAL axis in cancer: evidence for mutation-specific selectivity in non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 36, 291–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorfe A. A., Babakhani A., McCammon J. A. (2007) H-ras protein in a bilayer: interaction and structure perturbation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12280–12286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel A., Reuther G., Roark M. B., Tan K. T., Waldmann H., Feller S. E., Huster D. (2010) Backbone conformational flexibility of the lipid modified membrane anchor of the human N-Ras protein investigated by solid-state NMR and molecular dynamics simulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798, 275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janosi L., Gorfe A. A. (2010) Segregation of negatively charged phospholipids by the polycationic and farnesylated membrane anchor of Kras. Biophys. J. 99, 3666–3674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang H., Abraham S. J., Chavan T. S., Hitchinson B., Khavrutskii L., Tarasova N. I., Nussinov R., Gaponenko V. (2015) Mechanisms of membrane binding of small GTPase K-Ras4B farnesylated hypervariable region. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 9465–9477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorfe A. A., Hanzal-Bayer M., Abankwa D., Hancock J. F., McCammon J. A. (2007) Structure and dynamics of the full-length lipid-modified H-Ras protein in a 1,2-dimyristoylglycero-3-phosphocholine bilayer. J. Med. Chem. 50, 674–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abankwa D., Gorfe A. A., Inder K., Hancock J. F. (2010) Ras membrane orientation and nanodomain localization generate isoform diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1130–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chavan T. S., Jang H., Khavrutskii L., Abraham S. J., Banerjee A., Freed B. C., Johannessen L. Tarasov, S. G., Gaponenko, V., Nussinov, R., Tarasova, N. I. (2015) High-affinity interaction of the K-Ras4B hypervariable region with the Ras active site. Biophys. J. 109, 2602–2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu S., Banerjee A., Jang H., Zhang J., Gaponenko V., Nussinov R. (2015) GTP binding and oncogenic mutations may attenuate hypervariable region (HVR)-catalytic domain interactions in small GTPase K-Ras4B, exposing the effector binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 28887–28900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chavan T. S., Meyer J. O., Chisholm L., Dobosz-Bartoszek M., Gaponenko V. (2014) A novel method for the production of fully modified K-Ras 4B. Methods Mol. Biol. 1120, 19–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hildebrandt E. R., Davis D. M., Deaton J., Krishnankutty R. K., Lilla E., Schmidt W. K. (2013) Topology of the yeast Ras converting enzyme as inferred from cysteine accessibility studies. Biochemistry 52, 6601–6614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grayson P., Tajkhorshid E., Schulten K. (2003) Mechanisms of selectivity in channels and enzymes studied with interactive molecular dynamics. Biophys. J. 85, 36–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanwell M. D., Curtis D. E., Lonie D. C., Vandermeersch T., Zurek E., Hutchison G. R. (2012) Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 4, 17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., Scalmani, G., Barone, V., Mennucci, B., Petersson, G. A., Nakatsuji, H., Caricato, M., Li, X., Hratchian, H. P., Izmaylov, A. F., Bloino, J., Zheng, G., Sonnenberg, J. L., Hada, M., Ehara, M., Toyota, K., Fukuda, R., Hasegawa, J., Ishida, M., Nakajima, T., Honda, Y., Kitao, O., Nakai, H., Vreven, T., Montgomery, Jr., J. A., Peralta, J. E., Ogliaro, F., Bearpark, M. J., Heyd, J., Brothers, E. N., Kudin, K. N., Staroverov, V. N., Kobayashi, R., Normand, J., Raghavachari, K., Rendell, A. P., Burant, J. C., Iyengar, S. S., Tomasi, J., Cossi, M., Rega, N., Millam, N. J., Klene, M., Knox, J. E., Cross, J. B., Bakken, V., Adamo, C., Jaramillo, J., Gomperts, R., Stratmann, R. E., Yazyev, O., Austin, A. J., Cammi, R., Pomelli, C., Ochterski, J. W., Martin, R. L., Morokuma, K., Zakrzewski, V. G., Voth, G. A., Salvador, P., Dannenberg, J. J., Dapprich, S., Daniels, A. D., Farkas, Ö., Foresman, J. B., Ortiz, J. V., Cioslowski, J., and Fox, D. J. (2009) Gaussian 09, Revision D.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, USA [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks B. R., Bruccoleri R. E., Olafson B. D., States D. J., Swaminathan S., Karplus M. (1983) CHARMM—a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 4, 187–217 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Durell S. R., Brooks B. R., Bennaim A. (1994) Solvent-induced forces between two hydrophilic groups. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 2198–2202 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woolf T. B., Roux B. (1994) Molecular dynamics simulation of the gramicidin channel in a phospholipid bilayer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 11631–11635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woolf T. B., Roux B. (1996) Structure, energetics, and dynamics of lipid-protein interactions: a molecular dynamics study of the gramicidin A channel in a DMPC bilayer. Proteins 24, 92–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jang H., Crozier P. S., Stevens M. J., Woolf T. B. (2004) How environment supports a state: molecular dynamics simulations of two states in bacteriorhodopsin suggest lipid and water compensation. Biophys. J. 87, 129–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang H., Zheng J., Nussinov R. (2007) Models of β-amyloid ion channels in the membrane suggest that channel formation in the bilayer is a dynamic process. Biophys. J. 93, 1938–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jang H., Ma B., Lal R., Nussinov R. (2008) Models of toxic β-sheet channels of protegrin-1 suggest a common subunit organization motif shared with toxic alzheimer β-amyloid ion channels. Biophys. J. 95, 4631–4642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jang H., Michaud-Agrawal N., Johnston J. M., Woolf T. B. (2008) How to lose a kink and gain a helix: pH independent conformational changes of the fusion domains from influenza hemagglutinin in heterogeneous lipid bilayers. Proteins 72, 299–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang H., Arce F. T., Capone R., Ramachandran S., Lal R., Nussinov R. (2009) Misfolded amyloid ion channels present mobile β-sheet subunits in contrast to conventional ion channels. Biophys. J. 97, 3029–3037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mustata M., Capone R., Jang H., Arce F. T., Ramachandran S., Lal R., Nussinov R. (2009) K3 fragment of amyloidogenic β(2)-microglobulin forms ion channels: implication for dialysis related amyloidosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 14938–14945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capone R., Mustata M., Jang H., Arce F. T., Nussinov R., Lal R. (2010) Antimicrobial protegrin-1 forms ion channels: molecular dynamic simulation, atomic force microscopy, and electrical conductance studies. Biophys. J. 98, 2644–2652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang H., Arce F. T., Ramachandran S., Capone R., Azimova R., Kagan B. L., Nussinov R., Lal R. (2010) Truncated β-amyloid peptide channels provide an alternative mechanism for Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 6538–6543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jang H., Teran Arce F., Ramachandran S., Capone R., Lal R., Nussinov R. (2010) Structural convergence among diverse, toxic β-sheet ion channels. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 9445–9451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jang H., Arce F. T., Ramachandran S., Capone R., Lal R., Nussinov R. (2010) β-Barrel topology of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid ion channels. J. Mol. Biol. 404, 917–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connelly L., Jang H., Arce F. T., Ramachandran S., Kagan B. L., Nussinov R., Lal R. (2012) Effects of point substitutions on the structure of toxic Alzheimer’s β-amyloid channels: atomic force microscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry 51, 3031–3038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Connelly L., Jang H., Arce F. T., Capone R., Kotler S. A., Ramachandran S., Kagan B. L., Nussinov R., Lal R. (2012) Atomic force microscopy and MD simulations reveal pore-like structures of all-D-enantiomer of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide: relevance to the ion channel mechanism of AD pathology. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 1728–1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Capone R., Jang H., Kotler S. A., Kagan B. L., Nussinov R., Lal R. (2012) Probing structural features of Alzheimer’s amyloid-β pores in bilayers using site-specific amino acid substitutions. Biochemistry 51, 776–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capone R., Jang H., Kotler S. A., Connelly L., Teran Arce F., Ramachandran S., Kagan B. L., Nussinov R., Lal R. (2012) All-d-enantiomer of β-amyloid peptide forms ion channels in lipid bilayers. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 1143–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta K., Jang H., Harlen K., Puri A., Nussinov R., Schneider J. P., Blumenthal R. (2013) Mechanism of membrane permeation induced by synthetic β-hairpin peptides. Biophys. J. 105, 2093–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jang H., Arce F. T., Ramachandran S., Kagan B. L., Lal R., Nussinov R. (2013) Familial Alzheimer’s disease Osaka mutant (ΔE22) β-barrels suggest an explanation for the different Aβ1-40/42 preferred conformational states observed by experiment. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 11518–11529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jang H., Connelly L., Arce F. T., Ramachandran S., Kagan B. L., Lal R., Nussinov R. (2013) Mechanisms for the insertion of toxic, fibril-like β-amyloid oligomers into the membrane. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 822–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jang H., Arce F. T., Ramachandran S., Kagan B. L., Lal R., Nussinov R. (2014) Disordered amyloidogenic peptides may insert into the membrane and assemble into common cyclic structural motifs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6750–6764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gillman A. L., Jang H., Lee J., Ramachandran S., Kagan B. L., Nussinov R., Teran Arce F. (2014) Activity and architecture of pyroglutamate-modified amyloid-β (AβpE3-42) pores. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 7335–7344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kucerka N., Tristram-Nagle S., Nagle J. F. (2005) Structure of fully hydrated fluid phase lipid bilayers with monounsaturated chains. J. Membr. Biol. 208, 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petrache H. I., Tristram-Nagle S., Gawrisch K., Harries D., Parsegian V. A., Nagle J. F. (2004) Structure and fluctuations of charged phosphatidylserine bilayers in the absence of salt. Biophys. J. 86, 1574–1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klauda J. B., Venable R. M., Freites J. A., O’Connor J. W., Tobias D. J., Mondragon-Ramirez C., Vorobyov I., MacKerell A. D. Jr, Pastor R. W. (2010) Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 7830–7843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muratcioglu S., Chavan T. S., Freed B. C., Jang H., Khavrutskii L., Freed R. N., Dyba M. A., Stefanisko K., Tarasov S. G., Gursoy A., Keskin O., Tarasova N. I., Gaponenko V., Nussinov R. (2015) GTP-dependent K-Ras dimerization. Structure 23, 1325–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mazhab-Jafari M. T., Marshall C. B., Smith M. J., Gasmi-Seabrook G. M., Stathopulos P. B., Inagaki F., Kay L. E., Neel B. G., Ikura M. (2015) Oncogenic and RASopathy-associated K-RAS mutations relieve membrane-dependent occlusion of the effector-binding site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6625–6630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boguski M. S., McCormick F. (1993) Proteins regulating Ras and its relatives. Nature 366, 643–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.