Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion of young, healthy myopic subjects with spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) angiography.

Design

A prospective comparative study was conducted from December 2014 to January 2015.

Setting

Participants recruited from a population-based study performed by the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai.

Participants

A total of 78 Chinese normal subjects (78 eyes) with different refraction were included. Myopia was divided into 4 groups on the basis of the refractive status: 20 eyes with emmetropia (mean spherical equivalent (MSE) 0.50D to −0.50D), 20 eyes with mild myopia (MSE −0.75D to −2.75D), 20 eyes with moderate myopia (MSE −3.00D to −5.75D), and 18 eyes with high myopia (MSE≤−6.00D).

Main outcome measures

Peripapillary and parafoveal retinal and choroidal perfusion parameters and their relationships with axial length (AL) and retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness were analysed.

Results

Significant differences were found for the retinal flow index and vessel density in the peripapillary area among the 4 groups, but not in the parafoveal area. The high myopia group had the lowest peripapillary retinal flow index and vessel density. In addition, there was a negative correlation (β=−0.002, p=0.047) between the AL and peripapillary retinal flow index and a positive correlation between RNFL thickness and the peripapillary retinal perfusion parameters (flow index: β=0.001, p=0.006; vessel density: β=0.350, p=0.002) even after adjustment for other variables.

Conclusions

Highly myopic eyes have a decreased peripapillary retinal perfusion compared with emmetropic eyes. Such vascular features might increase the susceptibility to vascular-related eye diseases.

Keywords: optic coherence tomography angiography, peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion, Myopia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The present study first explored the peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion of young, healthy myopic subjects with spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) angiography.

The novel technology of OCT angiography makes it possible to visualise the ocular circulation even to the capillary level.

This study was limited by its cross-sectional design, in that the number of participants was not very large and all were from the same racial background.

The potential mechanism of the reduced peripapillary perfusion in highly myopic eyes still needs further investigation.

Introduction

Myopia is one of the most common ocular disorders in the world. There is a higher prevalence in the Asian population (40–70%) than in the North American and European populations (20–30%),1–6 especially in China.7–9 The prevalence of myopia in young adults aged between 16 and 18 years increased from 74% in 1983 to 84% in 2000, and, in addition, the prevalence of high myopia (over −6.0D) in 18-year-old students increased from 10.9% in 1983 to 21% in 2000 in Taiwan.10 Retinal detachment, macular hole, choroidal neovascularisation, posterior staphyloma, macular atrophy and lacquer cracks are more frequent in high myopia. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that vascular dysfunction might also be one of the complications of myopia.11–15 Therefore, it is of importance to study the retinal perfusion in myopic eyes, because it can provide baseline information on physiological variations among different stages of myopia, and also because it is helpful for the early diagnosis and monitoring of chorioretinal atrophy in those eyes with high myopia.

It has been reported that the retinal or choroidal blood flow in myopic eyes was decreased using different techniques.11–15 Of those studies, Colour Doppler Imaging (CDI) has been used to obtain precise measurements of choroid blood flow calculated from the Doppler frequency shift of backscattered light.11 However, it is not sensitive enough to accurately measure the low velocities of the small vessels that make up the peripapillary or parafoveal microcirculation.

The recent development of split-spectrum amplitude-decorrelation angiography (SSADA) has made quantitative observation of retinal and choroidal perfusion possible.16–21 Previous studies found that optical coherence tomography (OCT) angiography with SSADA offers great intravisit repeatability and intervisit reproducibility in the measurement of the disc flow18 19 and good reliability for the observation of retinal perfusion in the region of the macula.20 21

The purpose of this study was to investigate the peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion of young, healthy myopic individuals with OCT angiography and to determine possible relationships with axial length (AL) and retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness.

Materials and methods

Participants

This was a prospective, comparative study of 78 eyes of 78 Chinese healthy volunteers with different refractive status recruited from a population-based study from December 2014 to January 2015. The study was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Volunteers had no known eye diseases as determined by a complete ophthalmic examination. One eye from each participants was chosen randomly for further examination. Inclusion criteria included best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 16/20 or better, intraocular pressure (IOP) <21 mm Hg and eye with normal RNFL and ganglion cell complex (GCC) thickness. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) history of intraocular surgery or ocular injury; (2) having other ocular or systemic diseases such as glaucoma or diabetes mellitus which might affect the ocular circulation; (3) medication usage within 2 weeks of measurements and (4) exhibiting any sign of pathological myopia at funduscopic examination (chorioretinal atrophy, lacquer cracks, lattice degeneration, staphylomas or pavingstone degeneration). One eye of each participant was assigned to one of four groups according to refraction: emmetropia (mean spherical equivalent (MSE) 0.50D to −0.50D), mild myopia (MSE −0.75D to −2.75D), moderate myopia (MSE −3.00D to −5.75D) and high myopia (MSE≤−6.00D). The participants were asked to refrain from consuming alcohol and caffeine and from smoking for 12 h prior to the study, since alcohol, caffeine and nicotine have been reported to affect the ocular blood flow (OBF).22 23

Examination

All participants were interviewed regarding their medical history, and underwent a complete ophthalmic examination, included measurement of BCVA, refractive status using an auto refractometer (Auto Kerato-refractometer KR-8800; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan), AL using an IOLMaster (Carl Zeiss Inc, Jena, Germany), IOP using non-contact tonometer measurements (Full Auto Tonometer TX-F; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan), slip-lamp biomicroscopy examination, fundus examination (TRC-NW200, Topcon), together with measurements of RNFL and GCC thickness (RTVue-XR OCT; Optovue Inc, Fremont, California, USA). Calculation of the mean spherical equivalence (MSE) using the spherical dioptre plus one-half of the cylindrical dioptric power for later analysis. IOP, pulse rate (PR) and blood pressure (BP) were measured at the time of OCT imaging. BP amplitude was calculated as the systolic BP (SBP) minus the diastolic BP (DBP). The mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated with the following formula: MAP=DBP+0.42 (SBP−DBP).24–26 The ocular perfusion pressure (OPP) was calculated by subtracting the IOP from the two-third of the MAP.27

Peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion measurements using OCT angiography

OCT angiography scans were obtained by the spectral domain system RTVue-XR OCT (Optovue Inc, software V.2014.2.0.65). This system has an A-scan rate of 70 kHz scans per second using a light source centred on 840 nm and a bandwidth of 45 nm. One eye of each participant was examined and scanned within the same visit. Three dimensional (3D) OCT angiography scans were acquired by using two repeated B-scans at 304 raster positions, with each B-scan consisting of 304 A-scans. With a B-scan frame rate of 210 frames per second, each OCT angiography volume scan can be acquired in approximately 3 s. Two volumetric raster scans, including one horizontal priority (x-fast) and one vertical priority (y-fast), were obtained consecutively. The volumetric scans were processed by the SSADA algorithm, and any motion artefacts were removed by 3D orthogonal registration and the merging of two scans. An en face retinal angiogram was created by projecting the flow signal internally to the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The exclusion criterion for OCT angiography scans was signal strength index (SSI) <45, and if a scan contains severe artefacts, it will be excluded from the analysis. All of this processing can be achieved using the contained software (Optovue Inc, software V.2014.2.0.65).

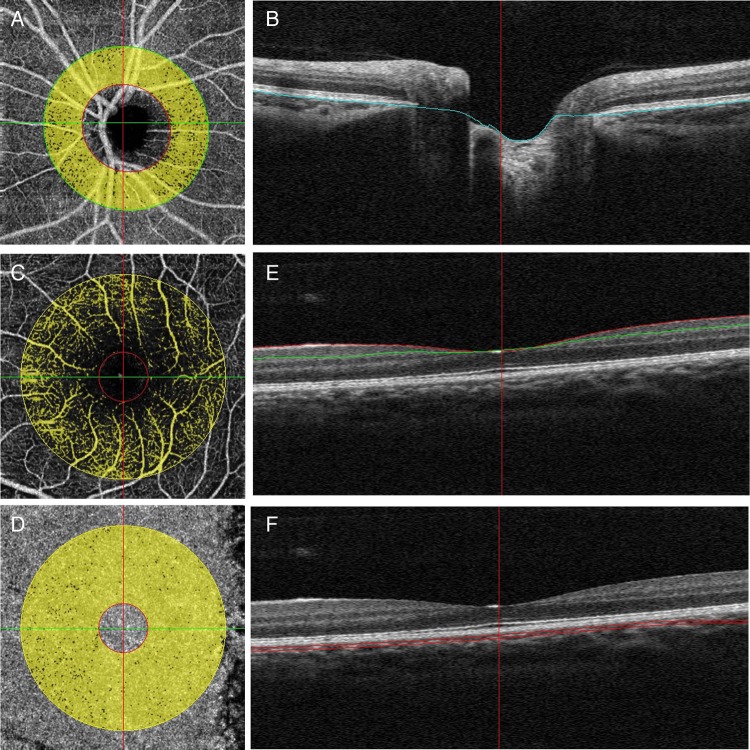

The scan pattern used was optimised for SSADA. Each set of scans comprised two 4.5×4.5 mm images of the optic disc and 3×3 mm images of the parafoveal area. The peripapillary region was defined as a 700 µm wide elliptical annulus extending outward from the optic disc boundary (figure 1A). The RPE was used as the dividing boundary between the retina and the choroid for isolating retinal blood flow (figure 1B). The parafoveal perfusion was measured using a masking procedure. The masking overlay consisted of an annulus, defined by an inner diameter of 0.6 mm and an outer diameter of 2.5 mm (figure 1C, D). The superficial layer of the parafoveal area was defined as being from the inner limiting membrane with an offset of 3 µ to the inner plexiform layer with an offset of 29 µ (figure 1E). The choroid part of the parafoveal area was defined as being from the RPE reference with an offset of 29–59 µ (figure 1F). The peripapillary flow index was defined as the average decorrelation value in the peripapillary region of the en face retinal angiogram. The peripapillary vessel density was defined as the proportion of the total area occupied by vessels. The blood vessels were defined as pixels with the decorrelation values over the threshold in the noise region, which were two SDs higher than the mean decorrelation value.16

Figure 1.

Peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion was measured by optical coherence tomography angiograms of the emmetropic eye. (A) The peripapillary region was defined as a 700 µm wide elliptical annulus extending outward from the optic disc boundary in optical coherence tomography (OCT) retinal angiograms. (B) The boundaries used for segmentation are indicated by the blue lines (retinal pigment epithelium) on cross-sectional OCT reflectance. (C and D) A masking procedure of measuring parafoveal retinal (C) and choroidal (D) perfusion consisted of an annulus defined by an inner diameter of 0.6 mm and an outer diameter of 2.5 mm. (E) The superficial area of parafovea was defined as from inner limiting membrane with offset of 3 µ to inner plexiform layer with offset of 29 µ. (F) The choroid area of parafoveal was defined as from retinal pigmental epithelium reference with offset of 29–59 µ.

Repeatability and reproducibility

Intravisit repeatability of peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion was calculated from a subset of 15 patient with emmetropia with two sets of scans performed in a single visit. The same subset of normal subjects was used to calculate intervisit reproducibility obtained from two sets of scans performed on two separate visits. The coefficient of variation (CV) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were calculated by comparing two measurements obtained at the same location by the same operator on separate visits of the participants. The subset of normal subjects used to calculate intravisit repeatability was also used to calculate intervisit reproducibility and was obtained from two sets of scans performed on two separate visits.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package (SPSS for windows, V. 20.0; SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Data are shown as mean±SD. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare the differences among the four groups. A χ2 test was applied to analyse the frequency data on gender. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to analyse the effect of other independent variables on the peripapillary retinal flow index parameters. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

Among the 87 participants recruited, 9 individuals were excluded from the analysis because of the poor signal quality (SSI<45) or blink artefacts. A total of 78 eyes from 78 participants (89.66%) were analysed in the study, and 20, 20, 20 and 18 eyes were in the emmetropia, mild myopia, moderate myopia and high myopia groups, respectively. The demographics of these participants are shown in table 1. There were no significant differences in age, gender, IOP, DBP, SBP, BP amplitude, MAP, PR or OPP among the four groups. However, the highly myopic eyes had a longer AL (23.85±0.62 mm, 24.22±0.77 mm, 25.66±0.81 mm and 26.58±0.87 mm in the emmetropia, mild myopia, moderate myopia and high myopia groups, respectively, p<0.001) and thinner RNFL thickness (107.1±5.8 µm, 103.6±7.2 µm, 99.7±7.1 µm and 98.3±6.9 µm in the emmetropia, mild myopia, moderate myopia and high myopia groups, respectively, p=0.001) compared with the other three groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and ocular characteristics of the participants in the four groups

| EM | MIM | MOM | HM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | (N=20) | (N=20) | (N=20) | (N=18) | p Value* | Post hoc† |

| Gender (male:female) | 9:11 | 11:09 | 10:10 | 9:09 | 0.940 | / |

| Age (years) | 16.6±0.9 | 16.8±0.7 | 16.8±0.8 | 16.3±0.5 | 0.172 | / |

| BCVA | 1.3±0.3 | 1.3±0.3 | 1.1±0.2 | 1.1±0.2 | 0.004 | EM>MOM; EM>HM |

| IOP (mm Hg) | 14.6±2.5 | 15.4±3.2 | 15.9±3.6 | 16.9±2.7 | 0.138 | / |

| MSE (dioptres) | −0.11±0.39 | −1.7±0.55 | −4.6±0.81 | −8.0±0.83 | <0.001 | EM>MIM>MOM>HM |

| Axial length (mm) | 23.85±0.62 | 24.22±0.77 | 25.66±0.81 | 26.58±0.87 | <0.001 | EM<MOM<HM; MIM<MOM<HM |

| DBP(mm Hg) | 75±7 | 74±9 | 73±9 | 74±9 | 0.831 | / |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 121±12 | 116±11 | 118±13 | 119±15 | 0.633 | / |

| BP amplitude (mm Hg) | 45±13 | 42±11 | 45±10 | 45±13 | 0.694 | / |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 94.3±7.0 | 91.4±8.1 | 91.7±9.3 | 92.7±9.9 | 0.707 | / |

| Mean OPP (mm Hg) | 48.3±5.2 | 45.5±5.9 | 45.2±5.7 | 44.9±6.3 | 0.239 | / |

| Pulse rate (bpm) | 76±10 | 79±9 | 82±11 | 83±11 | 0.104 | / |

| RNFL thickness (µm) | 107.1±5.8 | 103.6±7.2 | 99.7±7.1 | 98.3±6.9 | 0.001 | EM>MOM; EM>HM |

| GCC thickness (µm) | 98.6±4.3 | 97.3±5.0 | 97.5±5.5 | 95.2±4.9 | 0.217 | / |

| Rim area (mm2) | 1.56±0.29 | 1.47±0.32 | 1.39±0.24 | 1.31±0.32 | 0.066 | / |

| C/D area ratio | 0.3±0.2 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.3±0.1 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.870 | / |

Numbers displayed are mean±SD.

*All calculated by the One-way analysis of variance, except the values in bold, which were calculated by χ2 test.

†Multiple comparisons among the four refraction groups.

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; BP, blood pressure; C/D, cup/disc; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EM, emmetropia; GCC, ganglion cell complex; HM, high myopia; IOP, intraocular pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MIM, mild myopia; MOM, moderate myopia; MSE, mean spherical equivalent; OPP, ocular perfusion pressure; RNFL, retinal nerve fibre layer; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Repeatability and reproducibility of peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion measurements

As shown in online supplementary table S1, regarding intravisit repeatability, the CV values ranged from 1.10% to 4.60%, and ICC values ranged from 0.81 to 0.99 for peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion parameters. Regarding inter-visit repeatability, the CV values ranged from 1.39% to 7.81%, and ICC values ranged from 0.69 to 0.96 for peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion parameters. These values were based on measurements from 15 patient with emmetropia.

bmjopen-2015-010791supp_tableS1.pdf (92.7KB, pdf)

Peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion of the four groups

Significant differences among the four groups were found for the retinal flow index (p<0.001) and retinal vessel density (p=0.002) in the peripapillary area, but not for the choroidal perfusion in the peripapillary area (table 2). In addition (see online supplementary figure S1), the highly myopic eyes had lower peripapillary retinal flow index (p=0.002) (see online supplementary figureS1A–E) and peripapillary retinal vessel density (p=0.006) (see online supplementary figure S1A–D, F) than the emmetropic eyes. The highly myopic eyes also had lower peripapillary retinal flow index (p=0.016) (see online supplementary figure S1B–E) and peripapillary retinal vessel density (p=0.016) (see online supplementary figure S1B–D, F), than the mild myopia). Furthermore, statistical analysis revealed that there were no significant differences in the parafoveal parameters, including retinal flow index (p=0.762), retinal vessel density (p=0.823), choroidal flow index (p=0.440) and choroidal vessel density (p=0.316) among the four groups (table 2).

Table 2.

Peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion of the four groups

| Emmetropia | Mild myopia | Moderate myopia | High myopia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (N=20) | (N=20) | (N=20) | (N=18) | p Value* |

| Peripapillary perfusion | |||||

| Retinal flow index | 0.097±0.012 | 0.093±0.009 | 0.085±0.009 | 0.083±0.008 | <0.001 |

| Retinal vessel density (%) | 89.0±5.4 | 87.9±4.3 | 84.5±5.9 | 82.3±5.8 | 0.002 |

| Choroid flow index | 0.091±0.015 | 0.088±0.014 | 0.085±0.009 | 0.082±0.013 | 0.103 |

| Choroid vessel density (%) | 82.7±6.9 | 82.1±7.2 | 81.1±5.3 | 77.6±7.6 | 0.114 |

| Parafoveal perfusion | |||||

| Superficial flow index | 0.022±0.006 | 0.025±0.006 | 0.025±0.007 | 0.024±0.007 | 0.760 |

| Superficial vessel density (%) | 26.6±6.1 | 28.9±6.3 | 29.0±7.2 | 28.2±3.7 | 0.848 |

| Choroid flow index | 0.085±0.019 | 0.083±0.011 | 0.088±0.009 | 0.083±0.010 | 0.440 |

| Choroid vessel density (%) | 88.4±10.9 | 89.0±5.8 | 91.3±4.4 | 88.0±5.8 | 0.316 |

Numbers displayed are mean±SD.

*Differences between groups were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis test.

bmjopen-2015-010791supp_figure.pdf (249.6KB, pdf)

Correlation between AL and peripapillary perfusion parameters

By multiple linear regression analysis, AL was shown to be negatively correlated with the peripapillary retinal flow index (β=−0.003, p=0.001) and peripapillary retinal vessel density (β=−1.75, p<0.001). However, after the compounding factors including age, gender, OPP, RNFL thickness, cup/disc (C/D) area ratio and rim area were adjusted, only the peripapillary retinal flow index (β=−0.002, p=0.047) was found to be negatively correlated with AL (table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate regression models of axial length affecting peripapillary perfusion in respondents

| Retinal flow index |

Retinal vessel density |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model | Standardised β (SE) | Adjusted R2 | p Value | Standardised β (SE) | Adjusted R2 | p Value |

| Axial length | 1* | −0.376 (0.001) | 0.130 | 0.001 | −0.39 (0.47) | 0.144 | <0.001 |

| Axial length | 2 | −0.366 (0.001) | 0.116 | 0.001 | −0.37 (0.47) | 0.151 | 0.001 |

| Axial length | 3 | −0.375 (0.001) | 0.108 | 0.001 | −0.37 (0.48) | 0.14 | 0.001 |

| Axial length | 4 | −0.235 (0.001) | 0.205 | 0.048 | −0.22 (0.51) | 0.245 | 0.052 |

*Model 1 for crude; model 2, adjustment for age and gender; model 3, further adjustment for ocular perfusion pressure; model 4, further adjustment for retinal nerve fibre layer thickness, cup/disc area ratio and rim area.

Correlation between RNFL thickness and peripapillary perfusion parameters

RNFL thickness was shown by multiple linear regression analysis to be significantly positively correlated with the peripapillary retinal flow index (β=0.001, p<0.001) and vessel density (β=0. 39, p<0.001). After adjustment with the compounding factors age, gender, OPP, AL, C/D area ratio and rim area, RNFL thickness was still significantly positively correlated with the peripapillary retinal flow index (β=0.001, p=0.006) and peripapillary retinal vessel density (β=0.350, p=0.002) (table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate regression models of RNFL thickness affecting peripapillary perfusion in respondents

| Retinal flow index |

Retinal vessel density |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model | Standardised β (SE) | Adjusted R2 | p Value | Standardised β (SE) | Adjusted R2 | p Value |

| RNFL thickness | 1* | 0.440 (0.000) | 0.183 | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.08) | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| RNFL thickness | 2 | 0.444 (0.000) | 0.164 | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.08) | 0.217 | <0.001 |

| RNFL thickness | 3 | 0.450 (0.000) | 0.155 | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.09) | 0.207 | <0.001 |

| RNFL thickness | 4 | 0.404 (0.000) | 0.205 | 0.006 | 0.45 (0.11) | 0.245 | 0.002 |

*Model 1 for crude; model 2, adjustment for age and gender; model 3, further adjustment for OPP; model 4, further adjustment for axial length, cup/disc area ratio and rim area.

OPP, ocular perfusion pressure; RNFL, retinal nerve fiber layer.

Discussion

In this study, the eyes with high myopia were found to have a decreased peripapillary retinal perfusion, including flow index and vessel density, compared with the emmetropic eyes using OCT angiography. In addition, a significant negative correlation between the AL and peripapillary retinal flow index was demonstrated even after adjustments for age, gender, OPP, RNFL thickness, C/D area ratio and rim area. However, for the parafoveal retinal and choroidal perfusion, no significant difference was found between myopic and emmetropic eyes.

OCT angiography is not the first technique to be used to evaluate ocular perfusion in patients with myopia. The retinal blood flow of patients with myopia was previously investigated by fluorescein angiography (FA). Fluorescein transit times have been demonstrated to be delayed in high myopia.12 However, FA is not commonly used to monitor myopia because of its invasive nature and difficulty in quantification. Unlike FA, OCT angiography is a non-invasive technique that relies on the decorrelation of OCT signal amplitude reflected from non-static tissue. This allows for the quantification of flow that can be used to monitor retinal and choroidal perfusion while avoiding potential side effects of nausea and anaphylaxis associated with dye injection.28 29 CDI,11 15 the OBF analyser15 and laser Doppler velocimetry14 were three other non-invasive techniques that were reported to measure OBF in highly myopic eyes. With the use of CDI, Akyol et al11 found that the choroidal blood flow was decreased in patients with myopic eyes. With the use of CDI and OBF, Benavente-Pérez et al15 reported decreased pulse amplitude and central retinal artery blood velocity in high myopia when compared with emmetropes and low myopia. With laser Doppler velocimetry, Shimada et al14 found decreased retinal blood flow in high myopia. However, an obvious limitation of these three devices was that they mainly focused on large vessels and were not sensitive enough to measure the low velocities of small vessels accurately. Despite this, the study of peripapillary and parafoveal perfusion in eyes with high myopia has been rare. Anatomically, microvessels are closer to the optic nerve and macular fovea than the larger vessels, so it was of potential importance to study the peripapillary or parafoveal perfusion in highly myopic eyes.

The repeatability and reproducibility of SSADA OCT angiography techniques have been examined primarily in normal subjects. Jia et al18 reported that the intravisit repeatability and inter-reproducibility were 1.2% and 4.2% CV, respectively, for disc perfusion in four healthy subjects. Our study group previously reported that the mean ICC between two measurements from 15 eyes was 0.910 for vessel density, 0.925 for the flow index in parafoveal perfusion,21 and those were in agreement with the measurements of this study. Of note, the peripapillary perfusion parameters had better reproducibility and repeatability than the parafoveal perfusion parameters. A possible reason is that the macula is the most active local metabolism in the retina, and the fluctuation of blood flow may be greater than in the peripapillary area.

Using OCT angiography, eyes with high myopia were found to have a decreased peripapillary flow index and vessel density in the retina compared with emmetropic eyes in our study, and this result is in accordance with those of previous studies.11–15 Furthermore, peripapillary retinal flow index was found to be negatively correlated with AL, and positively correlated with RNFL thickness, even after adjustments for other factors in this study. What causes the decrease in peripapillary perfusion in highly myopic eyes? One possible mechanism is that excessive elongation of the eyeball could cause thinning of the retina, and the thinning of the retinal tissues might cause reduced oxygen demand and, as a result, the blood circulation could consequently decrease. Despite this, the mechanisms of the reduced blood flow in highly myopic eyes still require further study.

Past research has reported that RNFL thickness was significantly lower in high myopia and that there was a negative correlation between RNFL thickness and AL.30–32 Our findings agree with the previous results. However, studies on RNFL thickness and peripapillary perfusion in myopic eyes are very limited. Multiple regression models (table 4) have suggested that there is a positive correlation between RNFL thickness and peripapillary retinal perfusion parameters that is not mediated by other variables such as age, gender, OPP, AL, C/D area ratio and rim area. This suggests that there might be a link between the structural and vascular changes in the peripapillary area of highly myopic eyes. Then the question arises: Which one happens first, structural change or vascular change? One plausible answer relates to the fact that if the demand is diminished, the supply is also reduced.33 34 There is a hypothesis stating that the loss of RNFL may affect regional oxygen demand or the need of vascular supply in the peripapillary area, which would trigger the retinal vascular adjustment via autoregulatory mechanisms. Another possible answer is that reduced RNFL thickness and peripapillary perfusion parameters are due to the elongation of the globe. Although this cross-sectional study could not answer this question, a follow-up study using OCT angiography might be able to improve our knowledge on this.

The comparison of parafoveal perfusion between myopic eyes and emmetropic eyes revealed no significant differences. This result, obtained by OCT angiography, was in accordance with that obtained by Heidelberg retinal flowmetry.15 The reason why the peripapillary and parafoveal areas have different changes in microvasculations is still not fully understood, but the following points might provide some insights. First, the arterial blood supply is different for the peripapillary and parafoveal retina, which may represent a reason for the different relationships. Second, the parafoveal area is a belt of 0.95 mm in width that surrounds the foveal margin. Only 4–6 layers of ganglion cells and 7–11 layers of bipolar cells were found in this area,35 while the peripapillary area was found to have all 10 layers of the retina. Third, the participants in our study were very young, and their myopic changes were mainly located in the peripapillary area instead of the parafoveal area. What is more, the participants in our study did not present as cases of pathological myopia. Thus, further studies focusing on pathologically myopic individuals may be needed.

This study was limited by its cross-sectional design, in that the number of participants was not very large and all were from the same racial background, so further long-term studies with larger samples and a greater age spectrum might tell us more about ocular perfusion in myopic eyes. Moreover, we found a decrease in peripapillary perfusion in highly myopic eyes in this study. However, the peripapillary atrophy (PPA) may play a role in the decreased peripapillary blood flow in myopic eyes, and the PPA area may be considered as a confounding factor. Therefore, the potential mechanism still needs further investigation.

In short, this study demonstrates a reduced peripapillary flow index and vessel density in the retina of highly myopic eyes using OCT angiography, which might be a possible reason for the formation of chorioretinal atrophy in high myopia. In addition, AL was shown to be negatively related to the peripapillary retinal flow index. However, whether the reduced peripapillary perfusion in high myopia is a cause or result of the axial elongation of the eyeball, together with the possible role in the pathology of high myopia, needs to be clarified in future studies.

Footnotes

Contributors: XW, XK and XS conceived of and designed the experiments. XW, ML and JY performed the experiments. XW, XK and CJ analysed the data. XW, XK and XS wrote the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Major Scientific Equipment programme (grant number 2012YQ12008003, China) and the Special Scientific Research Project of Health Professions (grant number 201302015, China). The authors were supported by the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (grant number 13430710500, China), the New Technology Research Project, Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (SHDC12014114 and 2013SY058) and the Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (number 14ZR1405400).

Disclaimer: The sponsor or funding organisation had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Midelfart A, Midelfart S. Prevalence of refractive errors among adults in Europe. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:580 10.1001/archopht.123.4.580-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kempen JH, Mitchell P, Lee KE et al. The prevalence of refractive errors among adults in the United States, Western Europe, and Australia. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:495–505. 10.1001/archopht.122.4.495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose K, Smith W, Morgan I et al. The increasing prevalence of myopia: implications for Australia. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2001;29:116–20. 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2001.00389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawada A, Tomidokoro A, Araie M et al. Refractive errors in an elderly Japanese population: the Tajimi study. Ophthalmology 2008;115:363–70.e3. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong TY, Foster PJ, Hee J et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in adult Chinese in Singapore. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000;41:2486–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan CW, Wong TY, Lavanya R et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in Indians: the Singapore Indian Eye Study (SINDI). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:3166–73. 10.1167/iovs.10-6210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu HH, Xu L, Wang YX et al. Prevalence and progression of myopic retinopathy in Chinese adults: the Beijing Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2010;117:1763–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He M, Zheng Y, Xiang F. Prevalence of myopia in urban and rural children in mainland China. Optom Vis Sci 2009;86:40–4. 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181940719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang M, Li L, Chen L et al. Population density and refractive error among Chinese children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:4969–76. 10.1167/iovs.10-5424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin LL, Shih YF, Hsiao CK et al. Prevalence of myopia in Taiwanese schoolchildren: 1983 to 2000. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2004;33:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akyol N, Kükner AS, Ozdemir T et al. Choroidal and retinal blood flow changes in degenerative myopia. Can J Ophthalmol 1996;31:113–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avetisov ES, Savitzkaya NF. Some features in ocular microcirculation in myopia. Ann Ophthalmol 1977;9:1261–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James CB, Trew DR, Clark K et al. Factors influencing the ocular pulse-axial length. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1991;229:341–4. 10.1007/BF00170692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimada N, Ohno-Matsui K, Harino S et al. Reduction of retinal blood flow in high myopia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2004;242:284–8. 10.1007/s00417-003-0836-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benavente-Pérez A, Hosking SL, Logan NS et al. Ocular blood flow measurements in healthy human myopic eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010;248:1587–94. 10.1007/s00417-010-1407-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia Y, Morrison JC, Tokayer J et al. Quantitative OCT angiography of optic nerve head blood flow. Biomed Opt Express 2012;3:3127–37. 10.1364/BOE.3.003127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia Y, Tan O, Tokayer J et al. Split-spectrum amplitude-decorrelation angiography with optical coherence tomography. Biomed Opt Express 2012;20:4710–25. 10.1364/OE.20.004710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia Y, Wei E, Wang X et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography of optic disc perfusion in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1322–32. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Jiang C, Ko T et al. Correlation between optic disc perfusion and glaucomatous severity in patients with open-angle glaucoma: an optical coherence tomography angiography study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015;253:1557–64. 10.1007/s00417-015-3095-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei E, Jia Y, Tan O et al. Parafoveal retinal vascular response to pattern visual stimulation assessed with OCT angiography. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e81343 10.1371/journal.pone.0081343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J, Jiang C, Wang X et al. Macular perfusion in healthy Chinese: an optical coherence tomography angiogram study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:3212–17. 10.1167/iovs.14-16270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domino EF, Minoshima S, Guthrie S et al. Nicotine effects on regional cerebral blood flow in awake, resting tobacco smokers. Synapse 2000;38:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gdovinová Z. Blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery in heavy alcohol drinkers. Alcohol Alcohol 2001;36:346–8. 10.1093/alcalc/36.4.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaeser P, Orgul S, Zawinka C et al. Influence of change in body position on choroidal blood flow in normal subjects. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89:1302–5. 10.1136/bjo.2005.067884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Longo A, Geiser MH, Riva CE. Posture changes and subfoveal choroidal blood flow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004;45:546–51. 10.1167/iovs.03-0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sayegh FN, Weigelin E. Functional ophthalmodynamometry. Comparison between brachial and ophthalmic blood pressure in sitting and supine position. Angiology 1983;34:176–82. 10.1177/000331978303400303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riva CE, Grunwald JE, Petrig BL. Autoregulation of human retinal blood flow. An investigation with laser Doppler velocimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1986;27:1706–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayreh SS, Hayreh MS. Optic disc edema in raised intracranial pressure. II. Early detection with fluorescein fundus angiography and stereoscopic color photography. Arch Ophthalmol 1977;95:1245–54. 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450070143014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein MR, Parker CW. Reactions following intravenous fluorescein. Am J Ophthalmol 1971;72:861–8. 10.1016/0002-9394(71)91681-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung CK, Mohamed S, Leung KS et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer measurements in myopia: an optical coherence tomography study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:5171–6. 10.1167/iovs.06-0545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoh ST, Lim MC, Seah SK et al. Peripapillary retinal nerve fibre layer thickness variations with myopia. Ophthalmology 2006;113:773–7. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung CKS, Cheng ACK, Chong KKL et al. Optic disc measurements in myopia with optical coherence tomography and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:3178–83. 10.1167/iovs.06-1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kur J, Newman EA, Chan-Ling T. Cellular and physiological mechanisms underlying blood flow regulation in the retina and choroid in health and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 2012;31:377–406. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng L, Gong B, Hatala DA et al. Retinal ischemia and reperfusion causes capillary degeneration: similarities to diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:361–7. 10.1167/iovs.06-0510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermann D. Structure and Function of the Neural Retina. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 2rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Elsevier; 2008771–4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010791supp_tableS1.pdf (92.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010791supp_figure.pdf (249.6KB, pdf)