Abstract

This meta-analysis included eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with the aim of determining whether probiotic supplementation can improve H. pylori eradication rates. PUBMED, EBSCO, Web of Science, and Ovid databases were searched. We included RCTs that investigated the effect of combining probiotics, with or without a placebo, with standard therapy. A total of 21 RCTs that reported standard therapy plus probiotics were included. Compared to the placebo group, the probiotics group was 1.21(OR 1.21, 95% CI: 0.86, 1.69) and 1.28 (OR 1.28, 95% CI: 0.88, 1.86) times more likely to achieve eradication of H. pylori infection in intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis and per protocol (PP) analysis, respectively. Probiotics with triple therapy plus a 14-day course of treatment did not improve the eradication of H. pylori infection (OR 1.44, 95% CI: 0.87, 2.39) compared to the placebo. Moreover, the placebo plus standard therapy did not improve eradication rates compared to standard therapy alone (P = 0.816). However, probiotics did improve the adverse effects of diarrhea and nausea. These pooled data suggest that the use of probiotics plus standard therapy does not improve the eradication rate of H. pylori infection compared to the placebo.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a Gram-negative microaerophilic bacterium that dwells in the human gastric mucosa. It is commonly associated with gastroduodenal diseases in humans such as gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma1, peptic ulcer disease2, and even gastric cancer3,4. Almost 50% of the worldwide human population is infected, with people living in developing countries showing higher rates of infection5. Triple therapy, which has been proposed as a first approach for H. pylori eradication, includes a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), clarithromycin and either amoxicillin or metronidazole. Other choices include sequential therapy and quadruple therapy6. However, the eradication rate using standard therapy was reported to be unsatisfactory using first-line or second-line treatments due to increased resistance to antibiotics and patient non-compliance7,8,9. Probiotics appear to be promising supplements for standard therapy of H. pylori infection.

Probiotics are defined as living microbial species that can induce anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative mechanisms that may improve bowel microecology and general health10,11. Probiotics contain Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces boulardii, Bifidobacterium, and other bacteria and yeasts. Some meta-analyses have reported that probiotic supplementation can improve the eradication rate of H. pylori compared to standard therapy alone12,13,14. It is widely accepted that probiotics can improve H. pylori eradication and reduce side effects during standard therapy.

However, we found that the control groups in RCTs in previous meta-analyses were mostly without a placebo. Placebo preparations matched the probiotic preparation in color, size, shape and weight, and had no pharmacological effect. Surprisingly, we found that the eradication rate of H. pylori had no statistical significance between probiotic supplementation groups and placebo supplementation groups in most studies. A placebo may also influence the eradication rate of H. pylori by a placebo effect acting through the alteration of systemic and enteric levels of hormones15. Nevertheless, there is no direct research on placebo and H.pylori to support this viewpoint.

This study aimed to select RCTs, and establish whether probiotic supplementation could improve tolerance to H. pylori standard triple eradication therapy compared to the placebo. We included RCTs without a placebo for comparison.

Results

Study characteristics

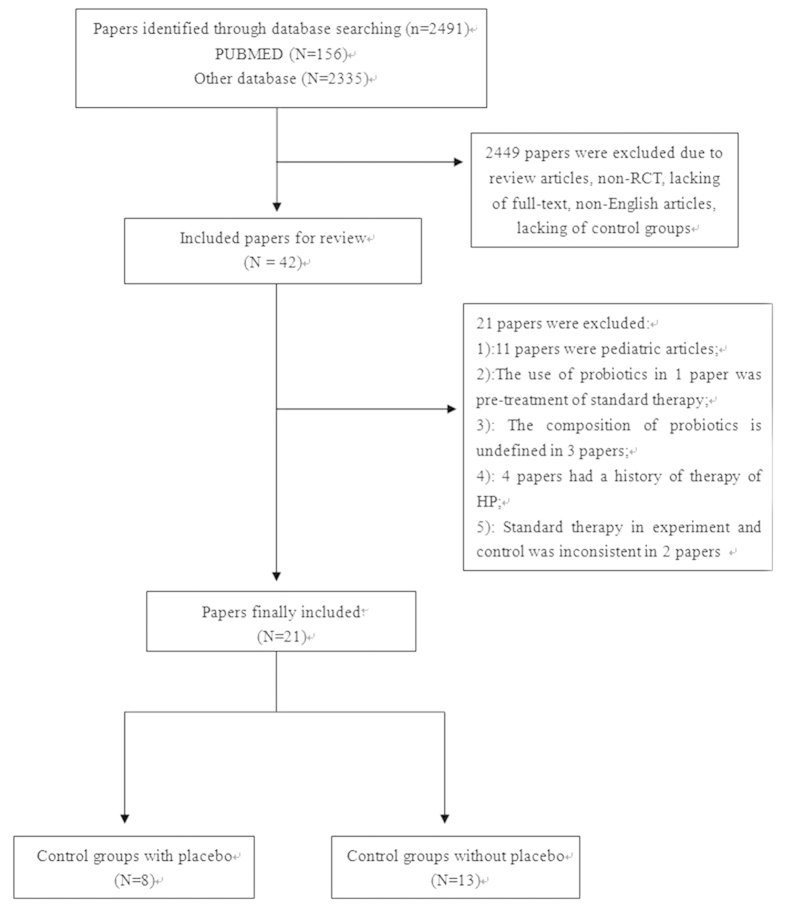

Our search identified 2,491 references, of which eight studies with placebo groups16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 and 13 studies without placebo groups24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Reasons for exclusion are shown in Fig. 1. Study characteristics of therapeutic regimens are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Geographically, studies mainly originated from Europe (13/21), with other studies originating from South America (1/21) and Asia (7/21). Twenty studies used standard triple therapy and one used bismuth-quadruple therapy. 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) was the main diagnostic method selected. A total of 3,520 participants were included in our research, in which 3,349 participants completed their respective trial. The terminal point of follow-up was reexamination of H. pylori infection after standard therapy, which ranged from 4 weeks to 10 weeks after the end of treatment. Characteristics of age, gender and type of patients are shown in Table 3. We found no significant difference in age (SMD = −0.05, 95% CI = −0.19, 0.09) or gender (OR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.8, 1.06) between the two groups. Ten studies used a single probiotic and 11 used compound probiotics. Placebos were administered in the same number of sachets as the probiotics. Boxes containing active study treatments, and placebos were identical in color, size, shape, weight and taste, and contained the same number of sachets. No trademark identifications were present, either on the probiotic or the placebo sachets. The composition of a placebo in one study was capsules of acidified milk powder (skim milk biologically acidified by commercial yogurt culture)21, of which no therapeutic effect was mentioned.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for searching studies.

Table 1. Study characteristics with placebo.

| Author/year | Country | Case number (probiotics/placebo) | Diagnostic Methods | Probiotics composition | Eradication Therapy | % Eradication in ITT (probiotics/placebo) | % Eradication in PP (probiotics/placebo) | Review of H. pylori |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nista et al.22 | Italy | 120 (60/60) | 13C-UBT | Bacillus clausii (B. clausii) | (rabeprazole 20 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × seven days + (probiotics or placebo) × 14 days | 72.22/71.15 | 78/74 | 13C-UBT six weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Navarro- Rodriguez et al.21 | Brazil | 107 (55/52) | 13C-UBT or histology | Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum and Streptococcus faecium | (lansoprazole 30 mg bid + tetracycline 500 mg bid + furazolidone 200 mg bid) × seven days + (probiotics or placebo) × 30 days | 81.82/76.92 | 88.24/81.63 | 13C-UBT eight weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Cremonini et al.18 | Italy | 42 (21/21) | 13C-UBT | Lactobacillus GG and S. boulardii | (rabeprazole 20 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + tinidazole 500 mg bid) x seven days + (probiotics or placebo) × 14 days | 81.82/72.73 | 85.71/80 | 13C-UBT 5–7 weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Cindoruk et al.17 | Turkey | 124 (62/62) | histology | S. boulardii | (lansoprazole 30 mg bid + Clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × 14 days + (probiotics or placebo) × 14 days | 70.97/59.68 | 70.97/59.68 | 13C-UBT six weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Manfredi et al.19 | Italy | 149 (73/76) | 13C-UBT or SAT | Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria | (esomeprazole 20 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × first five days + (esomeprazole 20 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + tinidazole 500 mg bid) × next five days + (probiotics or placebo) × 10 days (total) | 89.04/88.16 | 92.86/94.37 | SAT 8–10 weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Myllyluoma et al.20 | Finland | 47 (23/24) | 13C-UBT | Lactobacillus rhamnosus, L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium breve and Propionibacterium freudenreichii) | (lansoprazole 30 mg bid + Clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × seven days + (probiotics or placebo) × 28 days | 91.30/79.17 | 91.30/79.17 | 13C-UBT four weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Armuzzi et al.24 | Italy | 60 (30/30) | 13C-UBT | Lactobacillus GG | (rabeprazole 20 mg bid + Clarithromycin 500 mg bid + tinidazole 500 mg bid) × seven days + (probiotics or placebo) × 14 days | 83.33/80 | 83.33/80 | 13C-UBT six weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Shavakhi et al.23 | Iran | 180 (90/90) | RUT or histology | Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium | (omeprazole 20 mg bid + Clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid + bismuth 240 mg bid) × 14 days + (probiotics or placebo) × 14 days | 76.67/81.11 | 82.14/84.88 | 13C-UBT four weeks after the end of treatment. |

Table 2. Study characteristics without placebo.

| Author/year | Country | Case number (probiotics/control) | Diagnostic Methods | Probiotics composition | Eradication Therapy | % Eradication in ITT (probiotics/control) | % Eradication in PP (probiotics/control) | Review of H. pylori |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ziemniak et al.36 | Poland | 245 (53/192) | UBT | Lactobacillus acidophilus; Lactobacillus rhamnosus | (pantoprazole 40 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × 10 days + (probiotics or not) × 10 days | 96.23/85.94 | 96.23/85.94 | UBT six weeks after the end of treatment. |

| de Bortoli et al.26 | Italy | 206 (105/101) | 13C-UBT, SAT, RUT | Lactobacillus plantarum; L. reuterii; Bifidobacterium infantis, etc. | (esomeprazole 20 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × seven days | 88.57/72.27 | 92.08/76.04 | 13C-UBT eight weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Sheu et al.33 | China | 160 (80/80) | Histology, RUT | Lactobacillus-; Bifidobacterium- | (lansoprazole 30 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × 28 days | 91.25/78.75 | 94.81/87.5 | 13C-UBT eight weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Song et al.34 | Korea | 661 (330/331) | Histology, RUT | S. boulardii | (omeprazole 20 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × 28 days | 80/71.6 | 85.44/80.07 | 13C-UBT four weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Park et al.31 | Korea | 352 (176/176) | Histology | Bacillus subtilis; Streptococcus faecium | (omeprazole 20 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × 56 days | 83.52/73.3 | 85.47/78.66 | 13C-UBT four weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Kim et al.29 | Korea | 347 (168/179) | 13C-UBT, histology, RUT | L. acidophilus; L. casei; L. casei; S. thermophilus | (PPI bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × 21 days | 79.17/72.07 | 87.5/78.66 | 13C-UBT four weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Yasar et al.35 | Turkey | 76 (38/38) | Histology | Bifidobacterium | (pantoprazole 40 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × 14 days + (probiotics or not) × 14 days | 65.79/52.63 | 65.79/52.63 | 13C-UBT four weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Canducci et al.25 | Italy | 120 (60/60) | 13C-UBT, histology | Lactobacillus acidophilus | (Rabeprazole 20 mg bid + clarithromycin 250 mg tid + amoxicillin 500 mg tid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × 10 days | 86.67/70 | 88.14/72.41 | 13C-UBT four weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Armuzzi et al.16 | Italy | 120 (60/60) | 13C-UBT | Lactobacillus | (pantoprazole 40 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + tinidazole 500 mg bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × 14 days | 80/76.6 | 80/80.7 | 13C-UBT six weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Medeiros et al.30 | Portugal | 62 (31/31) | Culture | Lactobacillus acidophilus | (esomeprazole 20 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × eight days + (probiotics or not) × eight days | 83.87/80.65 | 83.87/80.65 | 13C-UBT 6–7 weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Scaccianoce et al.32 | Italy | 31 (15/16) | Histology | Lactobacillus plantarum; L. reuteri; Bifidobacterium Longum, etc. | (lansoprazole 30 mg bid + clarithromycin 500 mg bid + amoxicillin 1 g bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × 14 days | 53.33/62.5 | 53.33/66.67 | 13C-UBT 4–6 weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Deguchi et al.27 | Japan | 229 (115/114) | Culture, histology, RUT | L. gasseri | (rabeprazole 10 mg bid + clarithromycin 200 mg bid + amoxicillin 750 mg bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × 28 days | 82.61/69.3 | 85.59/74.53 | 13C-UBT 8 weeks after the end of treatment. |

| Imase et al.28 | Japan | 14 (7/7) | Not mentioned | CBM588 | (lansoprazole 30 mg bid + clarithromycin 400 mg bid + amoxicillin 750 mg bid) × seven days + (probiotics or not) × seven days | 100/87 | 100/87 | Not mentioned |

Table 3. Basic characteristics of the included studies.

| Author of study | Age (probiotics group) | Age (control group)* | M/F (probiotics group) | M/F (control group)* | Type of patients included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nista et al. | 46 ± 13 | 43 ± 13 | 33/27 | 22/38 | Free of gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Navarro- Rodriguez et al. | 50.4 | 48.4 | 21/34 | 19/33 | 51 PU patients and 56 dyspepsia patients |

| Cremonini et al. | – | – | – | – | Free of gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Cindoruk et al. | 45.82 ± 13.35 | 47.56 ± 13.53 | 26/36 | 18/44 | Dyspepsia patients |

| Manfredi et al. | 46.4 | 50.6 | 39/34 | 37/39 | Free of gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Shavakhi et al. | 42.3 ± 13.3 | 42.2 ± 13.2 | 49/41 | 60/30 | Patients with history of PU |

| Myllyluoma et al. | 57.3 | 53.8 | 10/13 | 8/16 | Free of gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Armuzzi et al. | – | – | – | – | Free of gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Ziemniak et al. | 44.4 ± 13.3 | 43.7 ± 10.3 | 14/39 | 78/114 | Patients with PU or gastritis |

| de Bortoli et al. | 51.5±13.7 | 50.1 ± 15.2 | 56/49 | 54/47 | Free or mild of gastrointestinal symptoms, among 25 PU patients |

| Sheu et al. | 47.8 | 45.9 | 40/40 | 38/42 | 84 PU patients and 76 dyspepsia patients |

| Song et al. | 49.76±11.7 | 49.84 ± 11.4 | 185/145 | 219/112 | Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms, among 492 PU patients |

| Park et al. | 45.2±19.8 | 47.6 ± 18.5 | 96/80 | 95/81 | Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms, among 142 PU patients |

| Kim et al. | 48.1 ± 12.4 | 53.7 ± 12.0 | 71/97 | 89/90 | 113 PU patients and 234 dyspepsia patients |

| Yasar et al. | 38.32 ± 10.66 | 36.95 ± 8.62 | 11/27 | 14/24 | Dyspepsia patients |

| Canducci et al. | – | – | – | – | Dyspepsia patients or patients with history of PU |

| Armuzzi et al. | – | – | – | – | Free of gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Medeiros et al. | 50.7 | 53.8 | 18/13 | 14/17 | Patients with history of PU |

| Scaccianoce et al. | 50 | 48 | 7/8 | 6/10 | Free of gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Deguchi et al. | 55.9 | 57.8 | 76/39 | 68/46 | Patients with history of PU |

| Imase et al. | – | – | – | – | Patients with history of PU |

*In this table, the control group contains groups with or without a placebo.

**PU = peptic ulcer.

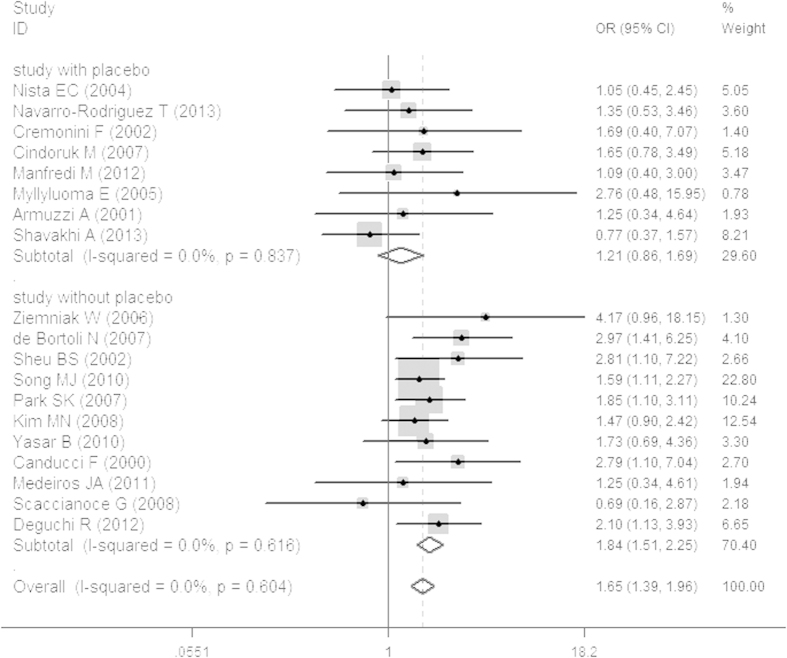

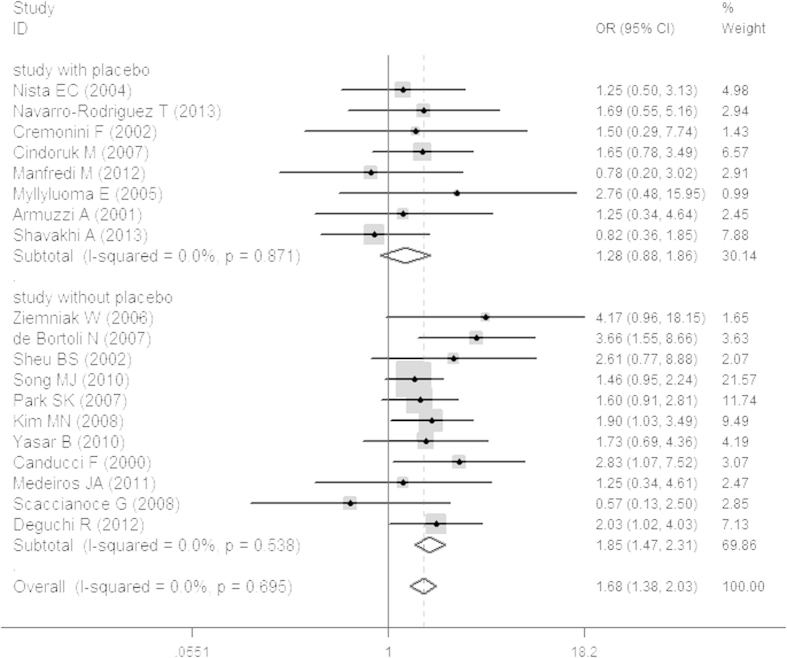

Eradication Rates

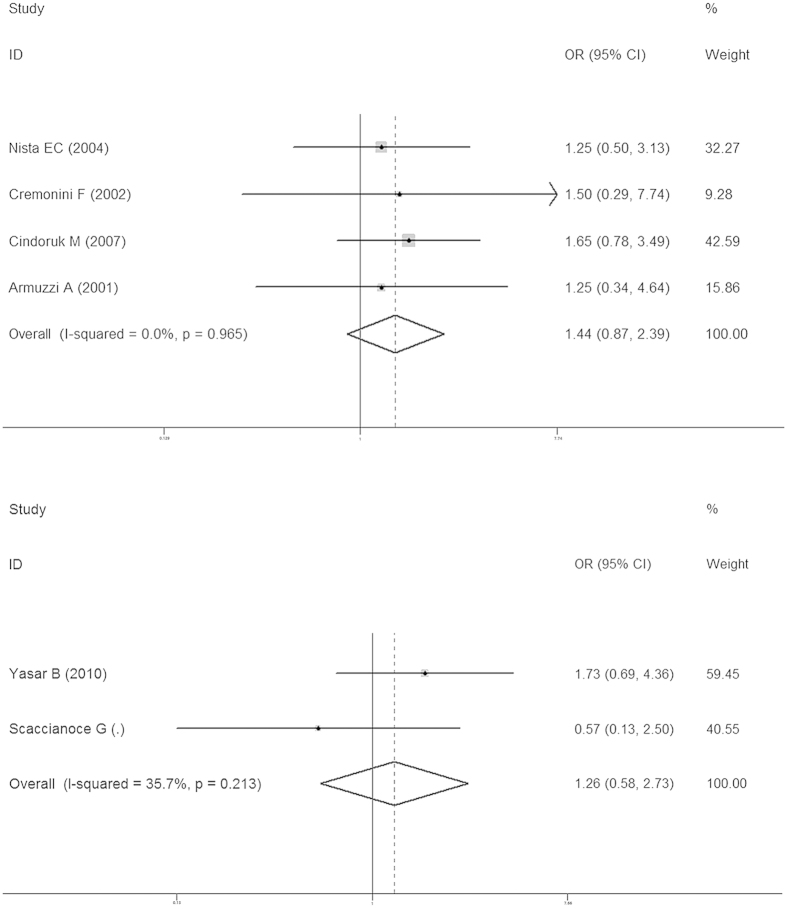

PP results were used to represent the final eradication rates. Total eradication rates were 84.32 ± 10.66% and 77.87 ± 9.39% in the probiotics and control groups, respectively. In the studies with a placebo, the eradication rate was 84.07 ± 14.09% in the probiotics group and 79.22 ± 9.84% in the placebo group. In studies without a placebo, the eradication rate of was 84.48 ± 12.61% in the probiotics group and 77.04 ± 9.4% in the non-placebo group. In addition, our study revealed that in ITT analysis the probiotics group was 1.21 times more likely than the placebo group to achieve eradication of H. pylori infection (OR 1.21, 95% CI: 0.86, 1.69; Fig. 2) and 1.84 times more likely than the standard-therapy-alone group (OR 1.84, 95% CI: 1.51, 2.25; Fig. 2). In PP analysis, the probiotics group was 1.28 times more likely than the placebo group to achieve eradication of H. pylori infection (OR 1.28, 95% CI: 0.88, 1.86; Fig. 3) and 1.85 times more likely than the standard-therapy-alone group (OR 1.85, 95% CI: 1.47, 2.31; Fig. 3). Both ITT and PP analyses showed no statistically significant effect on eradication rates when the probiotics group was compared to the placebo group, but the probiotics group had a significantly higher eradication rate when compared to standard therapy alone. To avoid bias caused by the anti-H. pylori therapy scheme or the duration of probiotic use, we also conducted a sub-group analysis on treatment using probiotics with triple therapy plus a 14-day course of treatment. This showed that the probiotics group was not more likely to achieve the eradication of H. pylori infection (OR 1.44, 95% CI: 0.87, 2.39; Fig. 4) without statistical significance. In standard-therapy-alone groups, sub-group analysis on triple therapy plus a 14-day course of treatment also showed no statistical significance (OR 1.74, 95% CI: 0.96, 3.16; Fig. 4). Moreover, both ITT (P > Z = 0.108; P > Z = 0.436) and PP (P > Z = 0.108; P > Z = 0.640) meta-analyses had no publication bias under Begg’s funnel plot test.

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of studies reporting on the eradication rate of H. pylori infections in the probiotics group vs. the placebo and non-placebo groups in ITT analysis and estimated the OR with a 95% confidence interval and weight percentage.

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of studies reporting on the eradication rate of H. pylori infection in the probiotics group vs. the placebo and non-placebo groups in PP analysis and estimated the OR with a 95% confidence interval and weight percentage.

Figure 4. Meta-analysis of studies reporting on the eradication rate of H. pylori infection in the probiotics group vs. the placebo and non-placebo groups (probiotics with triple therapy plus a 14-day course of treatment) and estimated the OR with a 95% confidence interval and weight percentage.

In addition, we compared the eradication rates in placebo administration plus standard therapy with the standard therapy group in order to determine whether placebo treatment can improve eradication rates. Results revealed no statistical significance (79.22 ± 9.84% vs. 77.04 ± 9.4%; P = 0.816). However, the trend still showed a potentially higher eradication rate in the placebo plus standard therapy group. Thus, RCTs on placebo plus standard therapy versus standard therapy alone are needed to verify our hypothesis.

Tolerance and adverse effects

The tolerance to the standard triple therapy itself may be affected by the probiotic supplementation. Among the included studies, only one clearly reported that there was no difference in tolerance between the probiotic and placebo groups (P = 0.833)23. Tolerance of standard therapy is affected by adverse effects. Therefore, we compared the adverse effects of diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, bloating, epigastric pain, constipation, headache and metallic taste. Between the probiotic group and the standard-therapy-alone group, we found that nausea (OR 0.43, 95% CI: 0.27, 0.7), vomiting (OR 0.3, 95% CI: 0.11, 0.86), diarrhea (OR 0.43, 95% CI: 0.21, 0.89), and constipation (OR 0.28, 95% CI: 0.13, 0.64) were improved in the probiotic group, whereas epigastric pain (OR 0.82, 95% CI: 0.48, 1.39), headache (OR 0.42, 95% CI: 0.11, 1.65), metallic taste (OR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.30, 1.58), and bloating (OR 0.54, 95% CI: 0.04, 6.64) were not different between the two groups (S1). Between the probiotic group and the placebo group, we found that nausea (OR 0.36, 95% CI: 0.21, 0.62), diarrhea (OR 0.33, 95% CI: 0.19, 0.57), and bloating (OR 0.5, 95% CI: 0. 3, 0.83) were improved in probiotic group, whereas epigastric pain (OR 0.58, 95% CI: 0.25, 1.32), vomiting (OR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.31, 1.62), and constipation (OR 0.56, 95% CI: 0.31, 1.01) were not different between the two groups (S2).

Nausea and diarrhea was clearly improved by probiotics, but it was not clear whether these two factors ultimately affected the curative effect.

Discussion

This meta-analysis analyzed whether probiotic supplementation can improve the eradication rate of H. pylori infection based on standard therapy. In contrast to previously published meta-analyses13,14,37, we studied control groups given a placebo in order to determine whether placebo administration can influence eradication rates compared to probiotics. Studies without placebos were included for comparison. Our results revealed that the inclusion of probiotics to standard therapy does not increase eradication rates of H. pylori compared to a placebo.

Triple therapy for eradication of H. pylori infection is unsatisfactory throughout the world. H. pylori is the best known microbe that colonizes the gastric mucosa, causing gastric related diseases, as shown by Marshall38. However, Walker et al. revealed that the imbalance of other gastric microbiota can play an important role in affecting human health39. This may be an important factor in the lack of efficacy of standard therapy. In addition, the increasing resistance to antibiotics such as clarithromycin6, the frequency and duration of drug administration, and the occurrence of side effects can influence a patient’s compliance40.

Many studies, including the meta-analysis mentioned above, have reported that probiotic supplementation can safely improve eradication rates of H. pylori infection and decrease side effects, although some probiotic products have been shown to increase the risk of complications in a minority of specific patient groups41. Probiotics have been shown to be useful in several illnesses such as reducing the duration and severity of rotavirus gastroenteritis42, reducing the incidence of traveler’s diarrhea43, preventing and reducing relapses of Clostridium difficile colitis44, and anti-inflammation benefits for inflammatory bowel disease45. The mechanisms by which probiotics play their role have not been clearly defined. Many possible mechanisms have been put forward, such as inhibiting the adhesion of pathogenic bacteria to the intestinal wall and competing with microbial pathogens for a limited number of receptors present on the surface epithelium46, altering cytokine expression and the activity of intestinal-associated lymphoid tissue and epithelial cells47,48, and enhancing intestinal barrier function49. Therefore, it seems that probiotics can provide powerful supplements for the eradication of H. pylori infection. However, our findings were not sufficient to justify such expectations.

A placebo is a simulated or otherwise medically ineffectual treatment for a disease or other medical condition that intends to deceive the recipient. It is well-known that psychological phenomena are closely associated with gastric diseases50. In addition, the placebo effect generates alterations in the levels of systemic and enteric hormones15, and subject-expectancy effects51. The use of a placebo seems to play a potential role in treating H. pylori infection. Nevertheless, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson and Peter C. Götzsche indicated that there is little evidence for placebos having a strong clinical impact and that the formation of the placebo effect is a subjective factor52,53. In our study, merged data revealed non-significant results on eradication rates, which may be due to population selection bias of the groups included for Student’s t-test. Thus, more evidence is needed. RCTs including standard therapy plus placebo compared to standard therapy alone are needed in order to analyze whether placebo supplementation can improve the eradication rate of H. pylori infection.

This is the first meta-analysis and systemic review to compare probiotics plus standard therapy with placebo plus standard therapy for H. pylori infection. Although we reviewed many reports to strengthen our study, several limitations of this meta-analysis were inevitable. First, we lacked a large sample size and RCTs with sufficient case numbers in the placebo group. More large-sample RCTs would have increased the power of this analysis. Second, it is not clear whether differences in probiotics dose or composition, or the course of treatment, as well as differences in the specificity and accuracy of the diagnostic tools for H. pylori infection would influence the results. Third, the influence of adverse effects of probiotics should not be ignored, which may contribute to the eradication of H. pylori infections. In addition, due to lack of data, potentially relevant confounders such as race, smoking, lifestyle, and gene polymorphisms were not analyzed.

In conclusion, all the published research on probiotics plus standard therapy indicates that probiotics improve the eradication rate of H. pylori infection. However, in our study, we found that a 14-day triple therapy plus probiotics cannot improve eradication rates. In addition, the pooled data of our meta-analysis suggest that the use of probiotics plus standard therapy does not improve the eradication rate of H. pylori infection compared to placebo plus standard therapy, although probiotic supplementation can improve eradication rates compared to standard therapy alone. A placebo may achieve the same curative effect for the eradication of H. pylori infection compared to probiotics. Future research should pay more attention to the role of placebo in H. pylori eradication.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

We searched studies published up to June 1, 2015, in PubMed, Ovid, EBSCO and Web of Science databases using the following terms: (Helicobacter pylori OR H. pylori OR Helicobacter infection OR Helicobacter* OR HP OR Helicobacter pylori (MeSH)), and (eradication OR treatment OR therapy OR disease eradication (MeSH)), and (probiotic OR probiotic* OR prebiotic OR yeast OR yogurt OR symbiotic OR Lactobacillus OR Bifidobacterium OR Saccharomyces OR Lactococcus OR Streptococcus OR Enterococcus OR probiotic(MeSH)). This study was limited to human and English-language randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In addition, the following criteria were used for selecting relevant studies: (1) study patients >18 years old; (2) study populations that have not been treated for H. pylori infection; (3) patients in the control group received standard therapy with or without a placebo; (4) patients in the experimental group received standard therapy with probiotics; (5) availability of relative information on H. pylori diagnosis and successful eradication rates; and (6) same administration of standard therapy for the experimental and control groups. Standard therapy was defined as triple treatment, sequential treatment, non-bismuth quadruple therapy, or bismuth-containing quadruple therapy6.

Combining the guideline6 and previous meta-analysis13, H. pylori infection diagnosed by at least one positive test result was considered confirmation of infection: (1) 13C/14C urea breath test (UBT); (2) rapid urease test (RUT); (3) H. pylori culture; (4) stool antigen test; or (5) histology of biopsy staining. The primary outcome of the study was the H. pylori eradication rate, which had to be confirmed by a negative 13C-UBT or other generally accepted method at least 4 weeks after the end of treatment. The secondary outcome measures were whether probiotics improve tolerance compared to the standard therapy. The adverse effects of interest were diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, bloating, epigastric pain, constipation, headache and metallic taste during anti-H. pylori therapy.

Eligibility of each study for inclusion was evaluated by two investigators. Any research-related disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. The quality of RCTs included in this study was assessed using the Jadad scale54.

Data abstraction

Two authors independently extracted data from all eligible studies, and a third author checked the results. Data were extracted into Microsoft Excel (2010 edition; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) to effectively organize the data. The following data were obtained from included studies: base characteristics of patients, authors, year of publication, country of research, details of H. pylori eradication therapy, details related to interventions, primary outcomes, and diagnostic methods of H. pylori infection.

Statistical Analysis

The ultimate goal of this study was to determine whether the probiotics group had a higher eradication rate than the placebo group. We also included groups without a placebo for comparison. Odds ratios (ORs) were used to measure the effect of probiotics plus standard therapy on H. pylori eradication rates in both intent-to-treat (ITT) and per protocol (PP). ORs were also used to measure the difference of adverse effects of interest between the probiotics group and the control group. Age and gender were analyzed by standardized mean difference (SMD) and OR, respectively. Statistical heterogeneity was analyzed with Chi-squared distribution, Chochran’s Q-test and I-squared statistics. A fixed-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel) was applied for meta-analysis if the I2 statistic was under 50% and/or the Q-test was not significant at P<0.05. We opted to stratify our analyses in this study with and without placebo. In addition, Begg’s funnel plot was used to assess publication bias. Data of eradication rates of standard therapy plus placebo and standard therapy alone were merged separately, and Student’s t-test analysis was conducted to compare these data. All analyses were carried out through the application of the commands metan and metabias in Stata 12.0 (Stata Corporation, Texas, USA), and Student’s t-tests were performed by SPSS 16.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Associated data were calculated and plotted using GraphPad Prism 5 (Graph Pad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lu, C. et al. Probiotic supplementation does not improve eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori infection compared to placebo based on standard therapy: a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 23522; doi: 10.1038/srep23522 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81400606) and the science and technology plan projects of Zhejiang Province (2015C33102).

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.L. and C.Y. designed the research; C.L. and J.S. performed the research; H.H., X.W. and Y.L. collected and analyzed the data; L.L. gave statistical support; Y.L. and C.Y. revised the manuscript; C.L. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Eck M. et al. MALT-type lymphoma of the stomach is associated with Helicobacter pylori strains expressing the CagA protein. Gastroenterology 112, 1482–1486 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek R. M. Jr. & Blaser M. J. Pathophysiology of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Am J Med. 102, 200–207 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. Q., Sridhar S., Chen Y. & Hunt R. H. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 114, 1169–1179 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., He Q. & Liu C. Correlations among Helicobacter pylori infection and the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in gastric mucosa with intestinal metaplasia or dysplasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25, 795–799 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suerbaum S. & Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 347, 1175–1186 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfertheiner P. et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection–the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut 61, 646–664 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D. Y. & Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut 59, 1143–1153 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J. M. et al. Levofloxacin-based and clarithromycin-based triple therapies as first-line and second-line treatments for Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomised comparative trial with crossover design. Gut 59, 572–578 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megraud F. Basis for the management of drug-resistant Helicobacter pylori infection. Drugs 64, 1893–1904 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller R. Probiotics in human medicine. Gut 32, 439–442 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Henry K. C. et al. Probiotics reduce bacterial colonization and gastric inflammation in H. pylori-infected mice. Dig Dis Sci 49, 1095–1102 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang Y., Reinhardt J. D., Zhou X. & Zhang G. The effect of probiotics supplementation on Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and side effects during eradication therapy: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 9, e111030 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szajewska H., Horvath A. & Piwowarczyk A. Meta-analysis: the effects of Saccharomyces boulardii supplementation on Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and side effects during treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 32, 1069–1079 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. M., Qian W., Qin Y. Y., He J. & Zhou Y. H. Probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 21, 4345–4357 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkotou E. et al. Serum correlates of the placebo effect in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 22, 285–e281 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armuzzi A. et al. The effect of oral administration of Lactobacillus GG on antibiotic-associated gastrointestinal side-effects during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 15, 163–169 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cindoruk M., Erkan G., Karakan T., Dursun A. & Unal S. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii in the 14-day triple anti- Helicobacter pylori therapy: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Helicobacter 12, 309–316 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremonini F. et al. Effect of different probiotic preparations on anti-helicobacter pylori therapy-related side effects: a parallel group, triple blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol 97, 2744–2749 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi M. et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in clinical practice: probiotics and a combination of probiotics + lactoferrin improve compliance, but not eradication, in sequential therapy. Helicobacter 17, 254–263 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllyluoma E. et al. Probiotic supplementation improves tolerance to Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy–a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 21, 1263–1272 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Rodriguez T. et al. Association of a probiotic to a Helicobacter pylori eradication regimen does not increase efficacy or decreases the adverse effects of the treatment: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol 13, 56 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nista E. C. et al. Bacillus clausii therapy to reduce side-effects of anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 20, 1181–1188 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavakhi A. et al. The effects of multistrain probiotic compound on bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomized placebo-controlled triple-blind study. Helicobacter 18, 280–284 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armuzzi A. et al. Effect of Lactobacillus GG supplementation on antibiotic-associated gastrointestinal side effects during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: a pilot study. Digestion 63, 1–7 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canducci F. et al. A lyophilized and inactivated culture of Lactobacillus acidophilus increases Helicobacter pylori eradication rates. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 14, 1625–1629 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de, Bortoli N. et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized prospective study of triple therapy versus triple therapy plus lactoferrin and probiotics. Am J Gastroenterol 102, 951–956 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi R. et al. Effect of pretreatment with Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 on first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 27, 888–892 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imase K. et al. Efficacy of Clostridium butyricum preparation concomitantly with Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in relation to changes in the intestinal microbiota. Microbiol Immunol. 52, 156–161 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. N. et al. The effects of probiotics on PPI-triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter 13, 261–268 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros J. A. et al. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori eradication by triple therapy plus Lactobacillus acidophilus compared to triple therapy alone. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 30, 555–559 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. K. et al. The effect of probiotics on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Hepatogastroenterology 54, 2032–2036 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaccianoce G. et al. Triple therapies plus different probiotics for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 12, 251–256 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu B. S. et al. Impact of supplement with Lactobacillus- and Bifidobacterium-containing yogurt on triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 16, 1669–1675 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. J. et al. The effect of probiotics and mucoprotective agents on PPI-based triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 15, 206–213 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasar B. et al. Efficacy of probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Turk J Gastroenterol 21, 212–217 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemniak W. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication taking into account its resistance to antibiotics. J Physiol Pharmacol 57 Suppl 3, 123–141 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Z. et al. Efficacy and safety of probiotics as adjuvant agents for infection: A meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 9, 707–716 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall B. J. & Warren J. R. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet 1, 1311–1315 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M. M. & Talley N. J. Review article: bacteria and pathogenesis of disease in the upper gastrointestinal tract–beyond the era of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 39, 767–779 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peura D. Helicobacter pylori: rational management options. Am J Med. 105, 424–430 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan K. & Myers C. E. Safety of probiotics in patients receiving nutritional support: a systematic review of case reports, randomized controlled trials, and nonrandomized trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 91, 687–703 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee do K. et al. Probiotic bacteria, B. longum and L. acidophilus inhibit infection by rotavirus in vitro and decrease the duration of diarrhea in pediatric patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 39, 237–244 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton E., Kolakowski P., Singer C. & Smith M. Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG as a Diarrheal Preventive in Travelers. J Travel Med 4, 41–43 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman G. The role of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 41, 763–779 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol H. et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA 105, 16731–16736 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack D. R., Michail S., Wei S., McDougall L. & Hollingsworth M. A. Probiotics inhibit enteropathogenic E. coli adherence in vitro by inducing intestinal mucin gene expression. Am J Physiol 276, G941–950 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller D. et al. Non-pathogenic bacteria elicit a differential cytokine response by intestinal epithelial cell/leucocyte co-cultures. Gut 47, 79–87 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. P., Sharma J., Babu S., Rizwanulla. & Singla A. Role of probiotics in health and disease: a review. J Pak Med Assoc 63, 253–257 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isolauri E. et al. Lactobacillus casei strain GG reverses increased intestinal permeability induced by cow milk in suckling rats. Gastroenterology 105, 1643–1650 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein S., Rosenstock S., Jacobsen R. K. & Jorgensen T. Psychological stress increases risk for peptic ulcer, regardless of Helicobacter pylori infection or use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13, 498–506 e491 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C. J., Mazzuca S. A. & McCabe G. P. Jr. How much of the placebo ‘effect’ is really statistical regression? Stat Med. 2, 417–427 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrobjartsson A. & Gotzsche P. C. Is the placebo powerless? An analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 344, 1594–1602 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrobjartsson A. & Gotzsche P. C. Is the placebo powerless? Update of a systematic review with 52 new randomized trials comparing placebo with no treatment. J Intern Med. 256, 91–100 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad A. R. et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17, 1–12 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.