Abstract

Background

Living in neighborhoods with a high density of alcohol outlets and socioeconomic disadvantage may increase residents’ alcohol use. Few researchers have studied these exposures in relation to multiple types of alcohol use, including beverage-specific consumption, and how individual demographic factors influence these relationships.

Objective

To examine the relationships of alcohol outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage with alcohol consumption, and to investigate differences in these associations by race/ethnicity and income.

Methods

Using cross-sectional data (N=5,873) from the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis in 2002, we examine associations of residential alcohol outlet density and neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage with current, total weekly and heaviest daily alcohol use in gender specific regression models, as well as moderation by race/ethnicity and income.

Results

Drinking men living near high densities of alcohol outlets had 23–29% more weekly alcohol use than men in low density areas. Among women who drank, those living near a moderate density of alcohol outlets consumed approximately 40% less liquor each week than those in low density areas, but higher outlet densities were associated with more wine consumption (35–49%). Living in highly or moderately disadvantaged neighborhoods was associated with a lower probability of being a current drinker, but with higher rates of weekly beer consumption. Income moderated the relationship between neighborhood context and weekly alcohol use.

Conclusions/Importance

Neighborhood disadvantage and alcohol outlet density may influence alcohol use with effects varying by gender and income. Results from this research may help target interventions and policy to groups most at risk for greater weekly consumption.

Keywords: alcohol use, neighborhood, alcohol availability, alcohol outlet, neighborhood disadvantage, race/ethnicity, income

INTRODUCTION

Excessive daily or lifetime alcohol use is a significant contributor to premature morbidity and mortality (Rehm, Greenfield & Rogers, 2001, Mokdad, 2004). Over 25,000 people died of direct alcohol-related causes in 2010; this excludes indirect alcohol deaths from accidents, unintentional injuries or homicides (Murphy, Xu & Kochanek, 2013). While low or moderate alcohol use may protect individuals from cardiovascular disease (Di Castelnuovo, Costanzo, Donati, Iacoviello & de Gaetano, 2010), it is also related to increased injury, violence, and sexual risk behavior (Galea 2004). Heavy drinking has been associated with increased risk for several chronic diseases, psychiatric problems and premature mortality (Gutjahr 2001, Rehm 2003). While individual-level contributors of alcohol use are well established (Galea 2004), the neighborhood environment has received increased attention as another important contributor (Galea, Ahern, Tracy & Vlahov, 2007).

Neighborhoods may influence drinking through alcohol availability. Increased alcohol outlet density has been associated with greater alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems (e.g., liver cirrhosis, sexually transmitted infections, motor vehicle crashes), and crime/violence, after adjustment for individual-level characteristics (Theall et al., 2009, Truong and Sturm 2009, Kavanagh et al., 2011, Theall et al., 2011, Toomey et al., 2012, Ahern, Margerison-Zilko, Hubbard & Galea, 2013). Results have not always been consistent, with some studies finding no association between alcohol outlet density and alcohol use (Pollack, Cubbin, Ahn & Winkleby, 2005, Schonlau et al., 2008, Tobler, Komro & Maldonado-Molina, 2009, Picone, MacDougald, Sloan, Platt & Kertesz, 2010), suggesting that availability may not fully explain consumption patterns (Livingston, Chikritzhs & Room, 2007).

Neighborhood disadvantage may also influence drinking (Karriker-Jaffe 2011). Social disorganization theory posits that economically disadvantaged neighborhoods lack the necessary social control and resources to maintain safety and order, (Sampson, Raudenbush & Earls, 1997) exposing residents to more frequent and severe stressors (Ross, Reynolds & Geis, 2000, Latkin and Curry 2003) such as violence and crime (Scribner, MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1995, Toomey et al., 2012). Residents living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods also may have fewer resources available for coping with stressors (Wen, Cagney & Christakis, 2005, Burgard and Lee-Rife 2009), and more permissive social norms towards alcohol use (Scribner 2007), and hence may be more likely to use alcohol as a coping mechanism (Conger 1956).

Several researchers have found that neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with greater alcohol use (Jones-Webb, Snowden, Herd, Short & Hannan, 1997, Galea 2004, Cerdá, Diez-Roux, Tchetgen, Gordon-Larsen & Kiefe, 2010, Karriker-Jaffe 2011, Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2012), although not all have found support for this relationship (Pollack et al., 2005, Galea et al., 2007, Stockdale et al., 2007, Karriker-Jaffe 2011, Mulia and Karriker-Jaffe 2012). One possible explanation for the mixed results is that the effects of neighborhood alcohol availability and socioeconomic disadvantage depend on individual-level factors such as gender, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES) (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2012, Mulia and Karriker-Jaffe 2012). Drinking patterns vary significantly by gender (Holmila and Raitasalo 2005), and gender may influence the way in which individuals interact with their environment to impact their health (Matheson, White, Moineddin, Dunn & Glazier, 2010, Kershaw, Albrecht & Carnethon, 2013). Gender influences access to social, psychological, and economic resources (Matheson et al., 2010), coping responses (Pearlin 1989, Cooper, Russell, Skinner, Frone & Mudar, 1992), and the quantity and quality of time spent in the neighborhood (Matheson et al., 2006), making gender a potential modifier in the association between neighborhood context and alcohol use. Theories of compound disadvantage posit that living in a stressful environment and also experiencing additional stressors due to social disadvantage generates the greatest risk for harmful health behaviors like alcohol use (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2012). Racial/ethnic minorities who are exposed to stressors in their neighborhood, in addition to the burden of racism and discrimination may be more likely to use alcohol to cope with stress than their non-minority counterparts (Borrell et al., 2010, Borrell, Kiefe, Diez-Roux, Williams & Gordon-Larsen, 2012). Finally, income could be an important effect modifier, as low income individuals have higher odds of risky drinking regardless of the SES of their neighborhoods of residence (Mulia and Karriker-Jaffe 2012). Mulia and Karriker-Jaffe (2012) found that low SES individuals living in high SES neighborhoods had the greatest odds of risky drinking, but that low SES individuals in low SES neighborhoods also had higher odds of risky use. Limited research indicates that neighborhood factors may interact with gender, race/ethnicity, and SES to differentially influence alcohol use, but these interactions have not been studied systematically (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2012), particularly with regards to alcohol outlet density.

Factors associated with the frequency and quantity, as well as the type of alcohol consumed may vary (Ahern et al., 2013, Smart 1996, Mulia and Karriker-Jaffe 2012). This may be partially attributed to variation in beverage strength by type of alcohol (World Health Organization, 2000), as higher levels of blood alcohol concentration can be reached more quickly by drinking wine and liquor compared to beer (Smart 1996). Additionally, differential effects of alcohol content and beverage type on risk behavior like drinking and driving have been documented (Smart and Walsh 1995), and there is limited evidence that beverage types may influence emotional responses like aggression and affect (Smart 1996). Rabow & Watts found, for example, that beer outlets, but not other types of outlets, were associated with public drunkenness and drunk driving arrests (Rabow and Watts 1982). Studies that include contextual influences on drinking rarely assess multiple drinking outcomes and beverage types, and do not examine the extent to which neighborhood factors are differentially related to specific types of alcohol use. Using data from the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), we examined the relationships of alcohol outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage with alcohol use in gender-specific models. We examined alcohol use by type of use (e.g., current, heavy, weekly use, wine vs. beer vs. liquor). In addition, we investigated differences in the relationships between neighborhood exposures and alcohol use based on race/ethnicity and income.

METHODS

The Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is a population-based, prospective cohort study of the risk factors and subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease. The original cohort included 6,814 men and women between the ages of 45 and 84 free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline (38% white, 28% African American, 22% Hispanic, 12% Asian). MESA participants were recruited from six field sites in the US (Forsyth County, NC; New York City, NY; Baltimore, MD; St Paul, MN; Chicago, IL; and Los Angeles, CA), and the baseline assessment was conducted from 2000 to 2002, with three follow-up assessments conducted at approximately 1.5–2 year intervals (Bild et al., 2002). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each site, and all participants gave written informed consent. In this cross-sectional study we included 5,783 participants who were included in a neighborhood sub-study, had non-missing data for income (N=232), education (N=18), job status (N=26), marital status (N=22) and for current alcohol use at Exam 2 (N=10). Additional participants were excluded from analyses of weekly (N=10) and heaviest daily alcohol (N=25) use based on missing outcome data.

Individual measures

Alcohol use outcomes

Alcohol use outcomes included current use, weekly use and heaviest daily use. Current alcohol use was assessed as a binary variable by asking participants if they “presently drink alcoholic beverages”. Current drinkers provided information on weekly and heaviest daily alcohol use based on counts of drinks consumed during the time period specified in the survey. For weekly alcohol use, participants reported the average number of drinks of beer, red wine, white wine, and liquor they typically consumed per week. We examined all weekly alcohol use combined and beer, wine (red and white combined) and liquor consumption separately. Participants also reported their heaviest daily alcohol use as the largest number of drinks consumed in a single day in the past month. Analyses of weekly and heaviest daily alcohol use were restricted to current drinkers.

Neighborhood measures

Information on alcohol outlets was obtained from the National Establishment Time Series (NETS) data from Walls and Associates for 2002. Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes for liquor stores and on-site drinking places (restaurants and bars) were used to identify alcohol outlets. SIC is a commercial classification system that categorizes businesses by 4-digit codes (Paquet, Daniel, Kestens, Léger & Gauvin, 2008), which can be further refined by sub-category. Alcohol outlets were derived from SIC coding for food stores, and sub-codes representing liquor stores and drinking places (consumption on-site) were selected. SIC codes for grocery stores were not included due to large variation in alcohol-sale laws. Alcohol outlet densities were created based on straight-line buffer zones around participants’ homes, and a one mile buffer Silverman kernel (Silverman 1986) was used as a reasonable buffer size for accessing alcohol by foot or car, and because it has been found to result in the largest effect sizes in similar studies (Scribner, Cohen & Fisher, 2000, Schonlau et al., 2008). Kernel densities, unlike simple densities, assign greater weight to alcohol outlets that are closer to participants’ homes (Silverman 1986). Densities were linked to the address of each MESA participant at the time of Exam 2. Alcohol outlet density was operationalized as a total outlet density score by standardizing liquor store density and drinking place density and then summing the scores. Liquor store and drinking place density were also examined separately in models.

Neighborhood disadvantage was assessed using data collected in the 2000 US Census (US Census, 2001). A previously developed composite index: median household income, household wealth (composed of median value of housing units and percent of households with interest, dividend, or net rental income), education (high school degree or higher and Bachelor’s degree or higher), and percent of employed persons 16 and older in executive, managerial, or professional occupation was used to characterize neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage for each census tract (Diez-Roux et al., 2001). Several items were log-transformed to improve the distribution before being standardized and summed to create the neighborhood disadvantage measure. Higher scores indicate more socioeconomic advantage. To allow for the possibility of non-linear or threshold effects, both alcohol outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage were categorized in three groups based on tertiles of their respective distributions.

Covariates

Covariates include current age, gender, race/ethnicity, study site, marital status, education, current job status and income. Race/ethnicity was assessed by four racial/ethnic categories: White/Caucasian, Chinese American, Black/African American or Hispanic. Participants denoted their highest level of education completed based on nine choices ranging from “no schooling” to “graduate or professional.” A continuous variable was created to assess total years of education by assigning each participant the interval midpoint of the selected category. Marital status (single, married/living with partner) was not assessed at Exam 2, so data for Exam 2 were imputed from exams 1 and 3 based on the closet date of the exam. Participants were asked whether they were currently married or living with a partner. A job status measure was created to characterize individuals as currently working or not working. Participants selected their gross family income over the past year by choosing from 13 categories that ranged from less than $5,000 to over $100,000. A continuous measure of annual income was created by assigning participants the interval midpoint of the selected category.

Analyses

We examined descriptive statistics for men and women stratified by current alcohol use and levels of weekly and daily alcohol use in current drinkers. Gender-stratified Poisson models with robust standard errors were used to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) of current alcohol use at Exam 2 (N=2,762 men; N=3,021 women) associated with alcohol outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage. Next, we estimated the associations of alcohol outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage with total, and beverage-specific weekly consumption among current users using gender stratified negative binomial regression models to account for overdispersion in the count of weekly alcohol use (N= 1,619 men, N=1229 women). A similar approach was used to examine associations of the neighborhood factors with heaviest daily alcohol consumption among drinkers (N=1,610 men; N=1,226 women). Model coefficients from the negative binomial regression models were exponentiated and are interpreted as ratios of the number of drinks (per week or on the heaviest day). Models accounted for clustering at the census tract level, and were adjusted for current age, race/ethnicity, site, marital status, education, current job status and income. Although we separately examined liquor store and bar/drinking place density in analyses, most results were similar to using a combined alcohol outlet density measure. We focus on total outlet density in the results and tables, but note specific analyses in which results varied by the type of outlet density.

Interactions of neighborhood factors with race/ethnicity and income were tested in gender-stratified models for current, weekly, and heaviest daily alcohol consumption. We retained and reported interactions if the global interaction test (Wald Test) resulted in p<0.05. We then examined significant individual contrasts (e.g. comparing the association in each race/ethnic group to the association in a reference category) and graphed the results. We conducted a total of 24 global interaction tests for race/ethnicity and neighborhood context (2 neighborhood factors interacted with race/ethnicity for 6 outcomes for men and women) and 24 global interaction tests for individual-level income and neighborhood context (2 neighborhood factors interacted with income for 6 outcomes for men and women).

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of current alcohol users by levels of alcohol use are displayed in Table 1. The average age of participants was 64 years, 48% were male, 39% were White, 27% were Black, 22% were Hispanic, and 12% were Chinese. The average annual income of participants was approximately $50,000. Most participants had at least a high school education, and 46% were employed. Approximately 49% of participants were current drinkers. Compared to non-drinkers, current drinkers were more likely to be younger, male, White, have higher SES, be married, and live in a neighborhood with higher SES and more alcohol outlets. Among men and women drinkers who consumed the most alcohol weekly and daily (>75th percentile), most were White. Male drinkers above the 75th percentile of weekly consumption were higher income and lived in areas with a higher density of alcohol outlets. Female drinkers above the 75th percentile had higher incomes, more education and lived in neighborhoods with a higher density of alcohol outlets and less socioeconomic disadvantage (Table 1). Male and female drinkers above the 75th percentile of daily use were younger on average than those who consumed less alcohol on a heavy drinking day, were more likely to be employed, and lived in areas with a higher density of alcohol outlets. Men above the 75th percentile of daily consumption also had lower education levels and lived in areas with more neighborhood disadvantage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the full sample and of drinkers by type and degree of alcohol use (mean, standard deviation/percent) at Exam 2

| Non- drinker | Current drinker | <=75th percentile, weekly use a | >75th percentile, weekly use | <=75th percentile, daily use b | >75th percentile, daily use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEN | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| N=1136 | N=1724 | N=1060 | N=663 | N=1159 | N=553 | |

|

| ||||||

| Age | 64.41 (10.03) | 63.11 (10.03)* | 63.30 (10.17) | 62.91 (9.81) | 64.52 (10.00) | 60.21 (9.44)* |

| Race (%) | ||||||

| White | 27.0 | 49.8* | 44.3 | 56.4* | 49.4 | 47.9* |

| Black | 29.6 | 23.0 | 24.7 | 20.8 | 24.3 | 20.8 |

| Hispanic | 25.4 | 19.2 | 19.3 | 18.9 | 14.9 | 28.0 |

| Chinese | 18.1 | 8.0 | 11.7 | 3.9 | 11.4 | 3.3 |

| Annual income ($US 10,000) | 4.49 (3.19) | 6.19 (3.56)* | 5.80 (3.52) | 6.63 (3.57)* | 6.12 (3.58) | 6.11 (3.53) |

| Education (years) | 12.83 (4.21) | 14.21 (3.57)* | 14.08 (3.64) | 14.27 (3.50) | 14.48 (3.41) | 13.46 (3.83)* |

| Employed (%) | 45.2 | 53.3* | 52.4 | 53.9 | 50.0 | 59.5* |

| Married/living w/ partner (%) | 72.3 | 74.4 | 74.8 | 73.8 | 75.6 | 72.2 |

| Alcohol outlet density b | 5.94 (8.67) | 7.17 (11.63)* | 6.10 (10.22) | 8.28 (12.59)* | 6.30 (10.90) | 8.12 (11.76)* |

| Neighborhood disadvantage c | −0.98 (5.77) | 1.24 (5.91)* | 1.03 (6.22) | 1.55 (6.26) | 1.57 (6.18) | 0.55 (6.30)* |

|

| ||||||

| WOMEN | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| N=1801 | N=1359 | N=507 | N=851 | N=921 | N=433 | |

|

| ||||||

| Age | 64.40 (10.08) | 62.02 (9.95)* | 61.91 (10.02) | 62.18 (9.95) | 63.07 (10.16) | 60.0 (9.24)* |

| Race (%) | ||||||

| White | 25.9 | 58.1* | 43.0 | 63.2* | 53.6 | 60.3* |

| Black | 32.2 | 23.1 | 29.8 | 21.2 | 25.3 | 22.2 |

| Hispanic | 25.9 | 14.4 | 20.5 | 11.2 | 13.9 | 16.2 |

| Chinese | 16.0 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 4.5 | 7.2 | 1.4 |

| Annual income ($US 10,000) | 3.63 (2.87) | 5.71 (3.50)* | 5.02 (3.23) | 6.01 (3.58)* | 5.56 (3.42) | 5.85 (3.63) |

| Education (years) | 11.93 (4.22) | 14.28 (3.15)* | 13.59 (3.67) | 14.49 (2.95)* | 14.15 (3.32) | 14.19 (3.10) |

| Employed (%) | 40.7 | 49.7* | 49.7 | 50.2 | 47.5 | 55.7* |

| Married/living w/ partner (%) | 37.6 | 53.2 | 52.7 | 53.0 | 54.3 | 49.9 |

| Alcohol outlet density c | 6.24 (9.31) | 9.34 (13.64)* | 6.76 (10.20) | 10.39 (14.38)* | 8.28 (12.55) | 10.65 (14.29)* |

| Neighborhood disadvantage d | −1.25 (5.65) | 1.60 (6.06)* | 0.20 (6.12) | 2.30 (6.43)* | 1.53 (6.23) | 1.57 (6.71) |

Low/moderate weekly alcohol use as defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) is <=14 drinks/week for men and <=7 drinks/week for women. Weekly alcohol use in the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) ranges from 0–104 drinks; Men above the 75th percentile consumed more than 6 drinks per week, and women above the 75th percentile consumed greater than 1 drink per week.

Low/moderate daily alcohol use is defined as <=4 drinks/day for men and <=3 drinks/day for women (NIAAA). The number of drinks consumed on the heaviest drinking day in MESA ranges from 0–30; in the MESA sample men above the 75th percentile consumed more than 3 drinks/day and women above the 75th percentile consumed greater than 2 drinks per day.

Measured in kernel density units.

Higher values represent less disadvantage.

Denotes a difference(s) between categories of type of alcohol use, based on F-tests for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables (p<0.05).

We report associations between tertiles of neighborhood disadvantage and alcohol outlet density and alcohol use and not between continuous measures of disadvantage and outlet density and alcohol use due to evidence of non-linear associations in initial analyses.

Current alcohol use

Alcohol outlet density was not associated with the prevalence of current alcohol use in men or women (Table 2), but living in a neighborhood in the highest disadvantage tertile (compared to the lowest) was associated with a lower probability of current alcohol use (PR = 0.87, 95% CI [0.79, 0.96], p<0.01 for men; PR = 0.86, 95% CI [0.74, 0.99], p=0.04 for women) (Table 2). Interactions between neighborhood characteristics and race/ethnicity or individual income were not significant.

Table 2.

Prevalence ratios (95% confidence intervals) of current alcohol use and ratios of the average number of drinks per week and day (on heaviest drinking day) among current drinkers associated with neighborhood context for men and women a,b

| Prevalence ratios of drinking | Ratio of the number of drinks/week | Ratio of the highest number of drinks/day | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||

|

| |||

| N=3021 | N=1229 | N=1226 | |

| Alcohol outlet density | |||

| Low c | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 1.15 (0.1.00,1.32)d | 0.87 (0.71,1.07) | 1.07 (0.95,1.19) |

| High | 1.10 (0.95,1.28) | 1.14 (0.92,1.41) | 1.09 (0.94,1.26) |

| p-value for trend | 0.15 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | |||

| Low c | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 0.93 (0.83,1.05) | 1.12 (0.90,1.40) | 0.95 (0.85,1.06) |

| High | 0.86 (0.74,0.99) | 1.08 (0.84,1.39) | 0.98 (0.86,1.11) |

| p-value for trend | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.20 |

|

| |||

| Men | |||

|

| |||

| N=2762 | N=1619 | N=1610 | |

| Alcohol outlet density | |||

| Low c | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 1.05 (0.96,1.14) | 1.15 (0.95,1.39) | 0.99 (0.90,1.01) |

| High | 0.94 (0.84,1.04) | 1.16 (09.92,1.46)e | 1.07 (0.95,1.20) |

| p-value for trend | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.29 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | |||

| Low c | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 0.98 (0.91,1.07) | 1.13 (0.97,1.32) | 1.04 (0.95,1.05) |

| High | 0.87 (0.79,0.96) | 1.11 (0.92,1.33) | 1.10 (0.97,1.25) |

| p-value for trend | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.15 |

All models are adjusted for age, race, marital status, income, education, job status and study site

Model includes both outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage

Reference category

p-value <0.05 in models of drinking place density

p-value <0.05 in models of liquor store density and drinking place density, separately

Note: Bolded values are significant at p<0.05

Overall weekly alcohol use

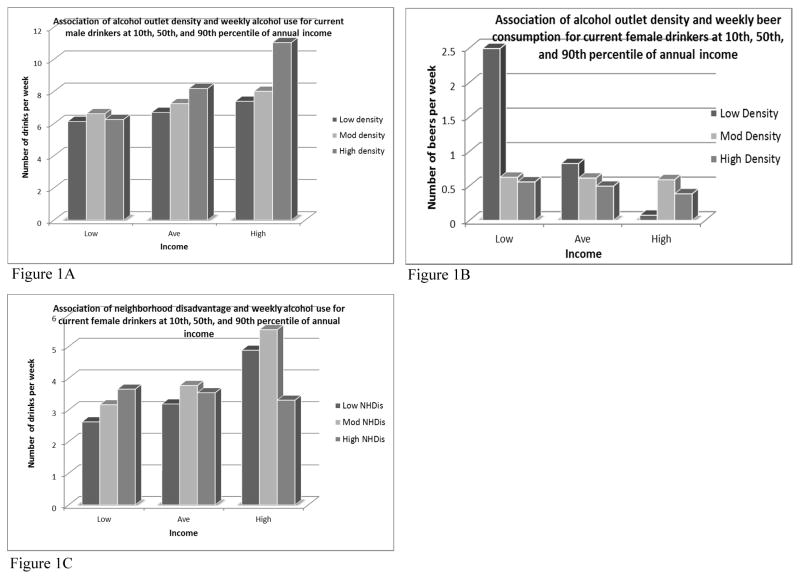

There was a significant trend towards increased weekly alcohol consumption for current male drinkers with increasing alcohol outlet density. Male drinkers who lived in the highest density areas of liquor outlets consumed 23% more per week, and those in the highest density areas of drinking places consumed 29% more than men in low outlet density areas (RR=1.23, 95% CI [1.03, 1.48], p=0.02; RR=1.29, 95% CI [1.09, 1.52], p<0.01 respectively) (Table 2 includes only combined alcohol outlet density, which did not reach statistical significance). Income moderated this relationship such that at low income levels outlet density was not related to the number of drinks consumed per week, whereas at high income levels, higher outlet density was associated with more weekly alcohol consumption (global p-value for effect modification=0.00) (Figure 1A). This pattern was even more pronounced for weekly wine consumption. Alcohol outlet density was not associated with the overall number of drinks consumed each week by women, although trends were similar to those in men.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A represents the relationship between tertiles of alcohol outlet density around residents’ homes and the average number of drinks consumed per week by drinking men, by strata of individual income (10th, 50th, 90th percentiles). Figure 1B represents the relationship between tertiles of alcohol outlet density around residents’ homes and the average number of beers consumed per week by drinking women, by strata of individual income (10th, 50th, 90th percentiles). Figure 1C represents the relationship between tertiles of neighborhood disadvantage and the average number of drinks consumed per week by drinking women, by strata of individual income (10th, 50th, 90th percentiles).

Neighborhood disadvantage was not associated with weekly alcohol consumption for men or women. Income moderated the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and weekly consumption in female drinkers: weekly alcohol consumption increased with increasing neighborhood disadvantage for women with low and moderate incomes, but stayed relatively constant across levels of disadvantage for higher income women (global p-value for effect modification <0.01; Figure 1C).

Weekly beer consumption

Drinkers who lived in neighborhoods with high disadvantage had higher beer consumption than drinkers in less disadvantaged neighborhoods (RR=1.40, 95% CI [0.96, 2.04], p= 0.08 for men; RR=2.86, 95% CI [1.59, 5.12], p<0.01 for women) (Table 3). Additionally, income moderated the association of outlet density and weekly beer consumption for women. Beer consumption decreased markedly as income increased for women in low outlet density areas but remained stable for women living in moderate or high density areas (Figure 1B).

Table 3.

Ratios (95% confidence intervals) of weekly beer, liquor, and wine consumption associated with neighborhood context among current drinkers a,b

| Beer | Liquor | Wine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men N=1618 | Women N=1224 | Men N=1615 | Women N=1226 | Men N=1617 | Women N=1228 | |

| Neighborhood | ||||||

| Disadvantage | ||||||

| Low c | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 1.14 (0.84,1.57) | 1.67 (0.93,3.01) | 1.17 (0.89,1.53) | 1.01 (0.68,1.50) | 1.12 (0.86,1.45) | 1.16 (0.89,1.51) |

| High | 1.40 (0.96,2.04) | 2.86 (1.59,5.12) | 0.97 (0.72,1.31) | 1.13 (0.74,1.72) | 0.86 (0.63,1.17) | 0.82 (0.60,1.13) |

| p-value for trend | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.38 | 0.16 |

| Alcohol outlet density | ||||||

| Low c | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | 1.03 (0.78,1.38) | 0.87 (0.54,1.42) | 1.03 (0.74,1.44) | 0.63 (0.42,0.94) | 1.25 (0.98,1.59) | 0.96(0.72, 1.28) |

| High | 1.37 (0.94,2.00) | 0.73 (0.43,1.24) | 1.04 (0.72,1.49) | 0.91 (0.58,1.43) | 1.31 (0.94,1.82) | 1.30 (0.96,1.78)d |

| p-value for trend | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.83 | 0.66 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

All models are adjusted for age, race, marital status, income, education, job status and study site

Model includes both outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage

Reference category

p-value <0.05 in models of liquor store density and drinking place density, separately

Bolded values are significant at p<0.05

Weekly liquor consumption

Women in moderate alcohol outlet density areas had lower weekly liquor consumption than women in low or high outlet density areas (RR=0.63, 95% CI [0.42, 0.94], p= 0.02).

Weekly wine consumption

Although total outlet density was not associated with weekly wine consumption for drinking women (Table 3), associations of liquor outlet density and drinking place density and wine consumption were significant. Women who lived near the highest densities of liquor outlets and drinking places consumed more wine each week (RR= 1.35, 95% CI [1.01, 1.81], p<0.05; RR= 1.49, 95% CI [1.13, 1.96], p<0.01). The total outlet density measure was likely not significant despite significant associations for the separate outlet density measures due to the weighting of the two distributions when they were added to create the total density measure. When the liquor and drinking place density measures were standardized and then summed (giving equal weight to each density measure), total outlet density was significant associated with weekly wine consumption in women.

Largest number of drinks on heaviest drinking day

Alcohol outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage were not associated with the number of drinks current drinkers consumed on their heaviest drinking day, although there are trends towards greater consumption for women living in the most disadvantaged areas (Table 2). Neighborhood context did not interact with race/ethnicity or income to influence heaviest daily consumption.

DISCUSSION

We found that neighborhood disadvantage and the density of alcohol outlets around individuals’ homes were associated with alcohol use, although these relationships varied by beverage type and socio-demographic characteristics. Alcohol outlet density was not associated with current use, but among men who were current drinkers, living in areas of high outlet density was associated with more weekly alcohol consumption. Additionally, among female drinkers, living in high liquor or drinking place density areas was associated with more weekly wine consumption. Finally, living in census tracts with high compared to low economic disadvantage was associated with a lower probability of drinking for men and women, although current drinkers consumed more beer each week than drinkers in less disadvantaged neighborhoods. While only a few significant associations emerged between neighborhood context and alcohol use outcomes, results were in the expected direction with consistent patterns for current drinkers.

Consistent with previous research (Truong and Sturm 2007, Connor, Kypri, Bell & Cousins, 2011, Kavanagh et al., 2011, Ahern et al., 2013, Halonen et al., 2013), we found that men who drank, and lived in areas of high alcohol outlet density consumed more alcohol each week than men in lower outlet density areas. These results support alcohol availability theories, where greater access to alcohol is hypothesized to result in more use (Gruenewald and Treno 2000, Fone et al., 2012). We did not find evidence for an association between alcohol outlet density and the probability of current use or heaviest daily consumption, although living in areas with the highest outlet densities trended towards drinking more alcohol on the heaviest drinking day for men and women.

Women living in areas of moderate alcohol outlet density had lower weekly liquor consumption than women in low or high density areas. The direction of the association between alcohol outlet density and weekly liquor consumption is contrary to our hypotheses and some previous research (Truong and Sturm 2007, Picone et al., 2010, Ahern et al., 2013, Pereira, Wood, Foster & Haggar, 2013), although other researchers did not examine gender-specific models. Men and women may not interact the same way with their environments, which may differentially influence alcohol use. Limited research indicates that neighborhood norms about drinking may more strongly affect women’s alcohol use compared to men’s use (Ahern, Galea, Hubbard, Midanik & Syme, 2008). We also found some gender differences in the associations of neighborhood context and beverage-specific weekly alcohol use, which offers further support that the neighborhood exerts different influences on drinking for men versus women. Given the relative dearth of evidence for gender differences in how neighborhood exposures affect health (Matheson et al., 2010, Osypuk 2013), future research should more closely examine processes through which neighborhood context differentially relates to alcohol use for men and women.

Although we hypothesized that neighborhood disadvantage would be positively associated with alcohol use, we found that higher neighborhood disadvantage resulted in a lower probability of alcohol use. Other researchers have found similar results, however (Pollack et al., 2005, Galea et al., 2007, Matheson et al., 2012, McKinney, Chartier, Caetano & Harris, 2012, Karriker-Jaffe, Roberts & Bond, 2013, Kuipers et al., 2013), which suggests that theories other than stress and coping may explain neighborhood influences on current alcohol use. Alternatively, neighborhood context may not influence current alcohol use, as using versus abstaining from alcohol is strongly related to individual and interpersonal factors like alcohol expectations, affect, health status and drinking norms (Cooper, Frone, Russell & Mudar, 1995, Ruchlin 1997). In an older sample like MESA, health status may be a particularly important predictor of current alcohol use (Ruchlin 1997). Among current male drinkers, however, neighborhood disadvantage was associated with higher weekly consumption. This supports theories of stress and coping as a mechanism through which neighborhood SES might influence alcohol use. Researchers have hypothesized that exposure to stressors may result in more alcohol use for coping specifically in men, while women may cope in more passive, internal ways resulting in higher rates of depression (Cooper et al., 1992). We did find, however, an association between living in a highly disadvantaged neighborhood and greater weekly beer consumption for women. More research is necessary to unpack differences in coping with neighborhood stressors for men and women, and whether gender and beverage type plays a role in these processes.

We did not find an association between neighborhood context and heaviest daily alcohol consumption for current drinkers, although our results were mainly in the expected direction. Heavy daily alcohol consumption in MESA is minimal, and the small variation may limit our ability to detect associations between neighborhood context and heavy daily alcohol use. Although other researchers have found strong associations between alcohol outlet density and neighborhood disadvantage and heavy or risky alcohol use (Cerdá et al., 2010, Kavanagh et al., 2011, Fone, Farewell, White, Lyons & Dunstan, 2013, Kuipers et al., 2013, Shimotsu et al., 2013), most of these studies assessed binge drinking, or heavy alcohol use based on levels of weekly consumption. These measures may more accurately characterize heavy use than asking participants to report the number of drinks they consumed on their heaviest drinking day in the past 30 days. Additionally, the populations included in these studies were younger on average than our older sample, and heavy alcohol use decreases with age (Moos, Schutte, Brennan & Moos, 2009). It is also possible that other neighborhood factors are more important for influencing heavy alcohol use than neighborhood disadvantage or alcohol outlet density in older populations. Shimotsu et al., for example, found that the mix of alcohol outlets and grocery stores had a greater influence on binge drinking than the density of alcohol outlets alone (2013). Retail mix may be an important neighborhood feature to consider in research, as individuals drinking choices are likely to depend on both access to alcohol and to other non-alcoholic resources like food.

While limited research indicates that alcohol use and alcohol problems for Black and Hispanic Americans are more strongly affected by the neighborhood context than that of White Americans (Jones-Webb et al., 1997, Mulia, Ye, Zemore & Greenfield, 2008, Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2012), we found no evidence for moderation by race/ethnicity. We did find that income moderated the relationship between neighborhood context and weekly alcohol consumption. Men living in neighborhoods with the greatest access to alcohol, and who also had the most economic resources to purchase alcohol had the highest rates of weekly alcohol consumption. This may indicate that the combination of having the easiest access to alcohol and the resources by which to purchase alcohol results in the most alcohol use. For women, the combination of lack of access to alcohol around their home and financial resources resulted in low beer consumption, suggesting that interventions may be most efficient when targeted towards lower income women, but men with the most access to alcohol.

We found a different effect of income on the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and weekly alcohol consumption. Weekly alcohol consumption for female drinkers increased with increasing neighborhood disadvantage in general, but the opposite was true for the highest income women. Living in a highly disadvantaged neighborhood resulted in lower weekly alcohol use for high income women. This also highlights the importance of targeting intervention and policy towards lower income women who may be most influenced by their neighborhood.

Our results highlight the complexity of neighborhood influences on alcohol use. We used a multi-site, multi-ethnic sample, which strengthens the generalizability of our results. We were also able to investigate variation in the relationship between neighborhood exposures and alcohol use by gender, race/ethnicity and income. These interactions are seldom investigated despite evidence that individual-level factors may moderate relationships between neighborhood context and alcohol use (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2012, Mulia and Karriker-Jaffe 2012). One of the strengths of our study was the focus on multiple patterns of alcohol use and types of alcohol consumed. Only two studies of which we are aware examined neighborhood effects on beverage-specific alcohol use (Picone et al., 2010, Jones-Webb and Karriker-Jaffe 2013). Developing a better understanding of how neighborhood context influences beverage-specific alcohol use has several important public health implications. First, if certain types of beverage consumption are more strongly associated with alcohol outlet density, zoning and policies related to alcohol sales such as taxation and restrictions on hours of sales could be more targeted to efficiently and effectively reduce alcohol-related harm. Given limited evidence that preferences for the type of alcohol consumed vary by individual attributes (Caetano, Clark & Tam, 1998, Johnson, Gruenewald, Treno & Taff, 1998), and also that alcohol type may be differently associated with alcohol harm (Smart and Walsh 1995), additional research is warranted. Additionally, if neighborhood context is more strongly associated with certain types of beverage consumption, this could have public health implications for alcohol-related problems like violence and drunk driving that may be likely to occur in neighborhoods with higher disadvantage or more alcohol outlets. Although our results only provide very limited evidence that neighborhood context may differently influence beverage-specific use, future research could offer additional information for policy-makers on how neighborhood context might affect potential consequences of specific types of alcohol use.

Several limitations temper the conclusions we can draw from this research. Most notably, our analyses were cross-sectional and we cannot be certain that our neighborhood exposures preceded our outcome. Researchers have found that alcoholics are more likely to live in lower SES neighborhoods (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2012). Additionally, we were not able to account for the length of time residents lived in their current neighborhood, which makes it impossible to determine the dose of the exposure. Although we used a diverse, multi-site sample, MESA participants are typically healthier than non-MESA participants living in similar areas because they had to be free of cardiovascular disease to be eligible for the study (Bild et al., 2002). It is possible that non-participation and attrition were higher among heavier drinkers compared to non- or lighter drinkers. This could result in bias if heavier drinkers are more likely to live in more disadvantaged and alcohol outlet-dense neighborhoods, although the bias would likely be towards the null. Although use of SIC codes for identifying commercial businesses is common, with precedent for doing so in studies of alcohol availability (Theall et al., 2011, Theall et al., 2012), SIC codes may less accurately identify alcohol retailers than other commercial businesses. This could result in differential identification of alcohol outlets by MESA site, as subtle differences in alcohol laws can influence the completeness of alcohol outlet listings. Despite these limitations, researchers have used SIC codes to identify alcohol outlets (Theall et al., 2011, Theall et al., 2012), as they have several advantages including availability and cost-effectiveness (Handy and Clifton 2001). Finally, the p-values for our results should be interpreted with caution, as we performed multiple comparisons in our analysis, and tested multiple interactions. We did find evidence of some consistent patterns, however, which increases confidence in our results despite multiple tests.

Our research contributes to prior work by exploring two potential theories that may connect neighborhood context to alcohol use. We found some support for increased access to alcohol resulting in higher rates of alcohol use as outlined by alcohol availability theories, and we found partial support for a neighborhood stress and coping model. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the associations between alcohol outlet density, neighborhood disadvantage and alcohol use for different types of alcohol. We found some evidence that living in areas with higher alcohol outlet density was related to greater consumption, but that this relationship varied by type of alcohol consumed and gender. Developing a more thorough understanding of the effect of alcohol availability on alcohol use may be a more logical point of intervention than focusing on neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, as access to alcohol is more amenable to policy interventions.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING This research was supported by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants UL1-RR-024156 and UL1-RR-025005 from NCRR and R01 HL071759 from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Contributor Information

Allison B. Brenner, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Ana V. Diez Roux, School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Tonatiuh Barrientos-Gutierrez, National Institute of Public Health, Cuernavaca, Morales, Mexico.

Luisa N. Borrell, Department of Health Sciences, Lehman College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York, New York, USA

References

- Ahern J, Galea S, Hubbard A, Midanik L, Syme SL. “Culture of drinking” and individual problems with alcohol use. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167(9):1041–1049. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern J, Margerison-Zilko C, Hubbard A, Galea S. Alcohol outlets and binge drinking in urban neighborhoods: the implications of nonlinearity for intervention and policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(4):e81–e87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;156(9):871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR, Jr, Shea S, Jackson SA, Shrager S, Blumenthal RS. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, smoking and alcohol consumption in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Preventive Medicine. 2010;51(3):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Diez-Roux AV, Williams DR, Gordon-Larsen P. Racial discrimination, racial/ethnic segregation, and health behaviors in the CARDIA study. Ethnicity & Health. 2012;18(3):227–243. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.713092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard S, Lee-Rife S. "Community characteristics, sexual initiation, and condom use among young Black South Africans.". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:293–309. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL, Tam T. Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1998;22(4):233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Diez-Roux AV, Tchetgen ET, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe C. The relationship between neighborhood poverty and alcohol use: estimation by marginal structural models. Epidemiology. 2010;21(4):482–489. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e13539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Alcoholism: Theory, problem and challenge: II. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JL, Kypri K, Bell ML, Cousins K. Alcohol outlet density, levels of drinking and alcohol-related harm in New Zealand: a national study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2011;65(10):841–846. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.104935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, Mudar P. Stress and alcohol use: moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101(1):139. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Prevention of cardiovascular risk by moderate alcohol consumption: epidemiologic evidence and plausible mechanisms. Internal and emergency medicine. 2010;5(4):291–297. doi: 10.1007/s11739-010-0346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux A, Merkin S, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto J, Sorlie P, Szklo M, Tyroler H, Watson R. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):99–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fone D, Dunstan F, White J, Webster C, Rodgers S, Lee S, Shiode N, Orford S, Weightman A, Brennan I, Sivarajasingam V, Morgan J, Fry R, Lyons R. Change in alcohol outlet density and alcohol-related harm to population health (CHALICE) BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):428–437. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fone DL, Farewell DM, White J, Lyons RA, Dunstan FD. Socioeconomic patterning of excess alcohol consumption and binge drinking: a cross-sectional study of multilevel associations with neighbourhood deprivation. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S. The social epidemiology of substance use. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26(1):36–52. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M, Vlahov D. Neighborhood income and income distribution and the use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(6 Suppl):S195–S202. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, Treno AJ. Local and global alcohol supply: Economic and geographic models of community systems. Addiction. 2000;95(12s4):537–549. doi: 10.1080/09652140020013764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr E. Relation between average alcohol consumption and disease: an overview. European Addiction Research. 2001;7(3):117–127. doi: 10.1159/000050729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halonen JI, Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Pentti J, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I, Vahtera J. Proximity of off-premise alcohol outlets and heavy alcohol consumption: A cohort study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132(1–2):295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handy SL, Clifton KJ. Evaluating neighborhood accessibility: Possibilities and practicalities. Journal of Transportation and Statistics. 2001;4(2/3):67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Holmila M, Raitasalo K. Gender differences in drinking: why do they still exist? Addiction. 2005;100(12):1763–1769. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson FW, Gruenewald PJ, Treno AJ, Taff GA. Drinking over the life course within gender and ethnic groups: A hyperparametric analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1998;59(5):568–580. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, Karriker-Jaffe K. Neighborhood disadvantage, high alcohol content beverage consumption, drinking norms, and drinking consequences: A mediation analysis. Journal of Urban Health. 2013;90(4):667–684. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9786-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, Snowden L, Herd D, Short B, Hannan P. Alcohol-related problems among black, Hispanic and white men: the contribution of neighborhood poverty. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1997;58(5):539–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K. Areas of disadvantage: A systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30(1):84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Roberts SCM, Bond J. Income inequality, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(4):649–656. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Zemore SE, Mulia N, Jones-Webb R, Bond J, Greenfield TK. Neighborhood Disadvantage and Adult Alcohol Outcomes: Differential Risk by Race and Gender [OPEN ACCESS] Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(6):865–873. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh AM, Kelly MT, Krnjacki L, Thornton L, Jolley D, Subramanian S, Turrell G, Bentley RJ. Access to alcohol outlets and harmful alcohol consumption: a multi-level study in Melbourne, Australia. Addiction. 2011;106(10):1772–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw KN, Albrecht SS, Carnethon MR. Racial and ethnic residential segregation, the neighborhood socioeconomic environment, and obesity among blacks and Mexican Americans. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;177(4):299–309. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers MA, Jongeneel-Grimen B, Droomers M, Wingen M, Stronks K, Kunst AE. Why residents of Dutch deprived neighbourhoods are less likely to be heavy drinkers: the role of individual and contextual characteristics. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2013;67(7):587–594. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C, Curry A. Stressful neighborhoods and depression: A prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(1):34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston M, Chikritzhs T, Room R. Changing the density of alcohol outlets to reduce alcohol-related problems. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2007;26(5):557–566. doi: 10.1080/09595230701499191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Creatore MI, Gozdyra P, Glazier RH. Urban neighborhoods, chronic stress, gender and depression. Social science & medicine. 2006;63(10):2604–2616. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson FI, White HL, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Glazier RH. Neighbourhood chronic stress and gender inequalities in hypertension among Canadian adults: a multilevel analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2010;64(8):705–713. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.083303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson FI, White HL, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Glazier RH. Drinking in context: the influence of gender and neighbourhood deprivation on alcohol consumption. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2012;66(6):e4–e12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.112441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney CM, Chartier KG, Caetano R, Harris TR. Alcohol availability and neighborhood poverty and their relationship to binge drinking and related problems among drinkers in committed relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(13):2703–2727. doi: 10.1177/0886260512436396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, MJSSDFGJL Actual causes of death in the united states, 2000. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Schutte KK, Brennan PL, Moos BS. Older adults' alcohol consumption and late-life drinking problems: a 20-year perspective. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1293–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Interactive Influences of Neighborhood and Individual Socioeconomic Status on Alcohol Consumption and Problems. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47(2):178–186. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Zemore S, Greenfield T. Social disadvantage, stress, and alcohol use among Black, Hispanic, and White Americans: Findings from the 2005 U.S. National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:824–833. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, Xu J, Kochanek K. Deaths: Final data for 2010. National vital statistics reports. Vol. 61. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. pp. 1–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W. H. International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Osypuk TL. Invited Commentary: Integrating a life-course perspective and social theory to advance research on residential segregation and health. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;177(4):310–315. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquet C, Daniel M, Kestens Y, Léger K, Gauvin L. Field validation of listings of food stores and commercial physical activity establishments from secondary data. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008;5(1):58. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30(3):241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G, Wood L, Foster S, Haggar F. Access to alcohol outlets, alcohol consumption and mental health. PloS one. 2013;8(1):e53461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picone G, MacDougald J, Sloan F, Platt A, Kertesz S. The effects of residential proximity to bars on alcohol consumption. International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics. 2010;10(4):347–367. doi: 10.1007/s10754-010-9084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack CE, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby M. Neighbourhood deprivation and alcohol consumption: does the availability of alcohol play a role? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabow J, Watts R. Alcohol availability, alcoholic beverage sales and alcohol-related problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1982;43(7):767–801. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J. Alcohol as a risk factor for global burden of disease. European addiction research. 2003;9(4):157–164. doi: 10.1159/000072222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Greenfield TK, Rogers JD. Average Volume of Alcohol Consumption, Patterns of Drinking, and All-Cause Mortality: Results from the US National Alcohol Survey. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;153(1):64–71. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Reynolds JR, Geis KJ. The contingent meaning of neighborhood stability for residents' psychological well-being. American Sociological Review. 2000;65(4):581–597. [Google Scholar]

- Ruchlin HS. Prevalence and Correlates of Alcohol Use among Older Adults. Preventive Medicine. 1997;26(5):651–657. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson R, Raudenbush S, Earls F. Neighborhoods and crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonlau M, Scribner R, Farley TA, Theall KP, Bluthenthal RN, Scott M, Cohen DA. Alcohol outlet density and alcohol consumption in Los Angeles county and southern Louisiana. Geospatial Health. 2008;3(1):91–101. doi: 10.4081/gh.2008.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R. Determinants of social capital indicators at the neighborhood level: a longitudinal analysis of loss of off-sale alcohol outlets and voting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(6):934–943. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scribner RA, Cohen DA, Fisher W. Evidence of a structural effect for alcohol outlet density: A multilevel analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24(2):188–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scribner RA, MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. The risk of assaultive violence and alcohol availability in Los Angeles County. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(3):335–340. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimotsu ST, Jones-Webb RJ, MacLehose RF, Nelson TF, Forster JL, Lytle LA. Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics, the retail environment, and alcohol consumption: A multilevel analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132(3):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman BW. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Smart RG. Behavioral and social consequences related to the consumption of different beverage types. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1996;57(1):77. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart RG, Walsh GW. Do some types of alcoholic beverages lead to more problems for adolescents? Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 1995;56(1):35. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale S, Wells K, Tang L, Belin T, Zhang L, Sherbourne C. The importance of social context: Neighborhood stressors, stress-buffering mechanisms, and alcohol, drug, and mental health disorders. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:1867–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theall KP, Drury SS, Shirtcliff EA. Cumulative neighborhood risk of psychosocial stress and allostatic load in adolescents. American journal of epidemiology. 2012;176(suppl 7):S164–S174. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theall KP, Lancaster BP, Lynch S, Haines RT, Scribner S, Scribner R, Kishore V. The Neighborhood Alcohol Environment and At-Risk Drinking Among African-Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(5):996–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theall KP, Scribner R, Cohen D, Bluthenthal RN, Schonlau M, Lynch S, Farley TA. The Neighborhood Alcohol Environment and Alcohol-Related Morbidity. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44(5):491–499. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler AL, Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina MM. Relationship between neighborhood context, family management practices and alcohol use among urban, multi-ethnic, young adolescents. Prevention Science. 2009;10(4):313–324. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0133-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey T, Erickson D, Carlin B, Quick H, Harwood E, Lenk K, Ecklund A. Is the density of alcohol establishments related to nonviolent crime? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(1):21–25. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong KD, Sturm R. Alcohol outlets and problem drinking among adults in California. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(6):923–933. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong KD, Sturm R. Alcohol environments and disparities in exposure associated with adolescent drinking in California. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(2):264–270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen M, Cagney K, Christakis N. Effect of specific aspects of community social environment on the mortality of individuals diagnosed with serious illness. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1119–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]