Abstract

The knotless barbed suture is an innovative type of suture that can accelerate the placement of sutures and eliminate knot tying. However, the outcomes of previous studies are still confounding. This study reviewed the application of different types of barbed sutures in different surgeries. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, CENTRAL and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the application of barbed sutures up to Feb. 2015. Two reviewers independently screened the literature and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. Then meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 software. Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis was performed. Seventeen RCTs (low to moderate risk of bias) involving 1992 patients were included. Compared with conventional sutures, the barbed suture could reduce suture time (SMD=−0.95, 95%CI −1.43 to −0.46, P = 0.0001) and the operative time (SMD=−0.28, 95%CI −0.46 to −0.10, P = 0.003), not significantly increase the estimated blood loss (SMD=−0.09, 95%CI −0.52 to 0.35, P = 0.70), but could lead to more postoperative complications (OR = 1.43, 95%CI 1.05 to 1.96, P = 0.03), These results varied in subgroups. Thus, barbed sutures are effective in reducing the suture and operative time, but the safety evidences are still not sufficient. It need be evaluated based on special surgeries and suture types before put into clinical practice.

The knotless barbed suture is a relatively new type of suture that has been widely used in both skin and deeper structures. It is a specifically designed monofilament suture with barbs orientated in the opposite direction to the needle. Generally, complications of conventional knot tying are well recognized; conventional knot tying requires time and training, and the knots may easily break or extrude. Infection related to knots is also frequently observed1. By contrast, the novel barbs on the ligatures make the suture grab the tissue, without allowing the suture to slide back.

Since their invention in 19642, barbed sutures have now been applied in various fields, including cosmetic, urological, general, orthopedic, obstetric, gynecological, and other surgeries. Specifically, barbed sutures are available in both absorbable and non-absorbable monofilament materials. Currently, three types of barbed sutures3 are commercially available: the Quill SRS (Quill Self-Retaining System; Angiotech Pharmaceuticals, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), which is a bidirectional barbed suture; the V-Loc Absorbable Wound Closure device (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA), which is a unidirectional barbed suture that has only 1 needle and a loop at the end; and the Stratafix (STRATAFIX Knotless Tissue Control Devices, Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA), which presents a spiral distribution of the barbs and anchors.

Although an increasing number of studies have reported the advantages of this technique, the outcomes of previous clinical trials are still confounding, and no studies have comprehensively examined the benefits. Thus, we present the available evidence in terms of the efficacy and safety of different types of knotless barbed sutures in different surgeries by performing a systematic review and meta-analysis of the current literature.

Results

Study selection process and characteristics

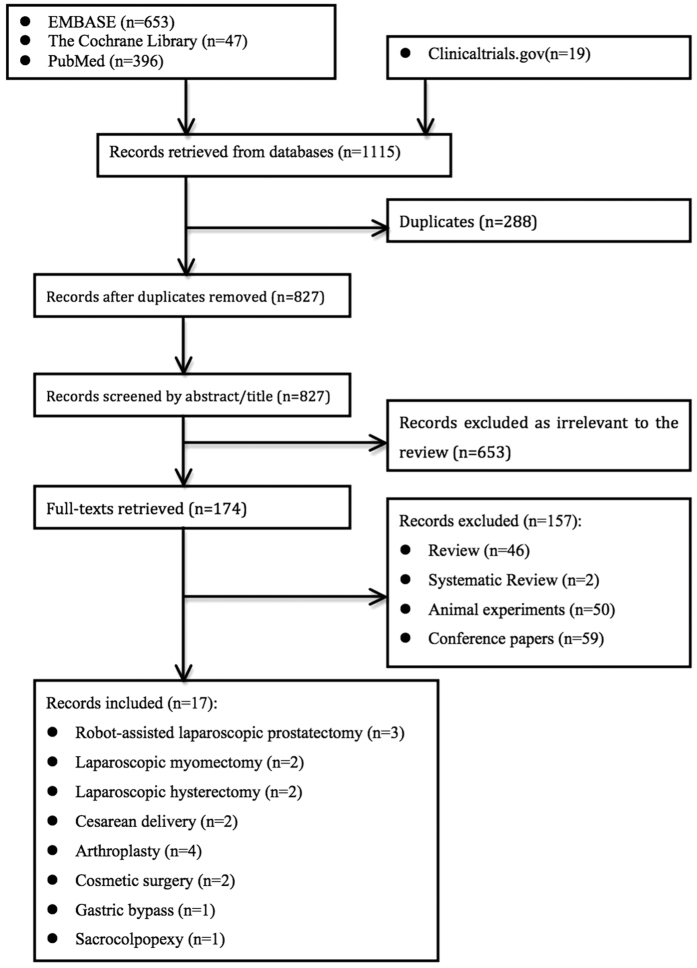

A total of 1115 records were identified after an initial search of selected electronic databases. A flow diagram of the detailed selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Finally, 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 1992 surgical patients were included for further meta-analyses4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Among these studies, 3 were related to robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy7,8,10, 2 were related to laparoscopic myomectomy5,11, 2 were related to laparoscopic hysterectomy12,13, 2 were related to cesarean delivery4,6, 4 were related to arthroplasty9,16,18,20, 2 were related to cosmetic surgery14,17, 1 was related to gastric bypass15, and 1 was related to sacrocolpopexy19. Table 1 provides the baseline characteristics of all studies.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the detailed selection process.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of all pooled studies in the meta-analysis.

| Author/Year | Type of surgery | Country | Barbed type | Sample size (barbed/control) | Cost |

Complications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbed | Conventional | ||||||

| Murtha 20065 | Cesarean delivery | USA | B | 127/61 | NS | NS | Wound dehiscence, incisional infection, surgical complication, seroma, hematoma, others |

| Alessandri 20106 | Laparoscopic myomectomy | Italy | U | 22/22 | € 20 | €7.30 | Ureteric injury, bladder injury, or bowel injury |

| Naki 20107 | Cesarean delivery | Turkey | U | 39/39 | NS | NS | Wound dehiscence, incisional infection, seroma, hematoma |

| Williams 20108 | Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy | USA | U | 45/36 | $51.52 | $8.44 | cystogram leak |

| Sammon 20119 | Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy | USA | B | 31/33 | NS | NS | Leaked urine, urinated blood, had pain or burning with urination |

| Ting 201210 | Arthroplasty | USA | B | 31/29 | THA:$52.75±$19.96; TKA:$52.84 ±$19.96 | THA:$12.79 ±$1.95; TKA:$9.43 ± $1.91, | Wound related or not complications |

| Zorn 201211 | Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy | Canada | U | 33/33 | $48.05 | $70.25 | Urinary retention, clinical urinary VUA leakage, anastomotic stricture, prolonged haematuria (>2 days) |

| Ardovino 201312 | Laparoscopic myomectomy | Italy | B | 36/81 | NS | NS | Wound dehiscence, bleeding |

| Ardovino 201313 | Laparoscopic hysterectomy | Italy | B | 18/43 | NS | NS | Bleeding, dyspareunia, and ureteric, bladder, or bowel injury occurred. |

| Einarsson 201314 | Laparoscopic hysterectomy | USA | B | 32/31 | NS | NS | Dehiscence, infection, bleeding, others |

| Grigoryants 201315 | Comestic surgery | USA | U | 30/30 | $47 or 94.6 | $45.69 or 91.38 | Wound infection, wound dehiscence, and suture extrusion, |

| Milone 201316 | Gastric bypass | Italy | U | 30/30 | €26 | €39.9±5.2 | Incidence of leak, bleeding, and stenosis |

| Gililland 201417 | Arthroplasty | USA | B | 191/203 | $324± $118 | $419 ±$116 | Broken sutures, needle sticks, stitch abscess, cellulitis, lymphangitis, sepsis systemic symptoms, pulmonary embolism |

| Rubin 201418 | Comestic surgery | USA& Germany | U | 229/229 | NS | NS | Wound dehiscence, suture extrusion, granuloma,and local wound infection |

| Smith 201419 | Arthroplasty | USA | B | 18/16 | $106.33 | $14.4 | Superficial wound infections, prominent suture |

| Tan-Kim 201420 | Sacrocolpopexy | USA | B | 32/32 | $38 | $32 – 96 | Developed back pain, mesh erosion, vaginal pain |

| Sah 201521 | Arthroplasty | USA | B | 50/50 | NS | NS | Wound dehiscence or disruption of the arthrotomy, suture irritation, suture end extrusion |

B: Bidirectional; U: Unidirectional.

NS: Not stated; THA:total hip arthroplasty;TKA:total knee arthroplasty;USA: the United States of America.

Of the 17 trials, 16 trials were performed using computer-generated randomization, 1 used the coin toss; 9 performed allocation concealment through central randomization; 5 applied blinding only to patients and 1 was open labeled; and 4 applied blinding to outcome assessors while 1 did not. The loss to follow-up occurred in 0 to 14.1% of patients. In general, the risk of bias was low to moderate in RCTs (Supplementary Table 1).

Quantitative data synthesis

The heterogeneity of barbed suture vs. conventional suture for all 17 studies was individually assessed and focused on different outcomes. Subgroup analyses were performed using different types of surgeries and barbed suture types (Table 2, Supplementary Figures 1–8).

Table 2. Pooled outcomes of all the subgroups.

| Outcomes | No. of Studies | No. of cases: Barbed/Control | SMD/MD/OR | 95%CI | Heterogeneity: | P value for effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUTURE TIME | ||||||

| Laparoscopic myomectomy¶ | 2 | 58/103 | −5.50 | [−7.03, −3.96] | P = 0.66; I2 = 0% | Z = 7.04 (P < 0.00001) |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy¶ | 2 | 50/74 | −1.10 | [−4.52, 2.32] | P = 0.02; I2 = 83% | Z = 0.63 (P = 0.53) |

| Arthroplasty¶ | 3 | 259/269 | −0.66 | [−4.43, 3.11] | P < 0.00001; I2 = 97% | Z = 0.34 (P = 0.73) |

| Cosmetic surgery¶ | 2 | 259/259 | −6.76 | [−8.72, −4.79] | P= 0.25; I2 = 25% | Z = 6.73 (P < 0.00001) |

| Sacrocolpopexy¶ | 1 | 32/32 | −13.60 | [−20.63, −6.57] | N/A | Z = 3.79 (P = 0.0001) |

| Gastric bypass¶ | 1 | 30/30 | −11.30 | [−12.23, −10.37] | N/A | Z =23.73 (P < 0.00001) |

| Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy¶ | 1 | 45/36 | −0.10 | [−0.19, −0.01] | N/A | Z = 2.24 (P = 0.03) |

| Cesarean delivery¶ | 1 | 127/61 | 0.60 | [−0.30, 1.50] | N/A | Z = 1.31 (P = 0.19) |

| Unidirectional barbed§ | 5 | 356/347 | −1.75 | [−2.69, −0.81] | P < 0.00001; I2 = 95% | Z = 3.65 (P = 0.0003) |

| Bidirectional barbed§ | 7 | 454/467 | −0.28 | [−0.89, 0.32] | P < 0.00001; I2 = 94% | Z = 0.92 (P = 0.36) |

| OPERATIVE TIME | ||||||

| Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy¶ | 2 | 76/69 | −6.85 | [−14.87, 1.17] | P = 0.90; I2 = 0% | Z = 1.68 (P = 0.09) |

| Laparoscopic myomectomy¶ | 2 | 58/103 | −2.73 | [−5.32, −0.14] | P = 0.43; I2 = 0% | Z = 2.07 (P = 0.04) |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy¶ | 2 | 50/74 | −4.48 | [−13.40, 4.43] | P = 0.31; I2 = 3% | Z = 0.32 (P = 0.99) |

| Gastric bypass¶ | 1 | 30/30 | −11.70 | [−22.83, −0.57] | N/A | Z = 2.06 (P = 0.04) |

| Unidirectional barbed§ | 4 | 128/121 | −0.35 | [−0.60, −0.09] | P = 0.85; I2 = 0% | Z = 2.70 (P = 0.007) |

| Bidirectional barbed§ | 3 | 86/155 | −0.20 | [−0.55, 0.16] | P = 0.19; I2 = 39% | Z = 1.09 (P = 0.28) |

| ESTIMATE THE INTRAOPERATIVE BLOOD LOSS | ||||||

| Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy§ | 2 | 78/69 | 0.03 | [−0.29, 0.36] | P = 0.55; I2 = 0% | Z = 0.19 (P = 0.85) |

| Laparoscopic myomectomy§ | 1 | 22/22 | −0.83 | [−1.45, −0.21] | N/A | Z = 2.64 (P = 0.008) |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy§ | 1 | 32/31 | 0.31 | [−0.18, 0.81] | N/A | Z = 1.23 (P = 0.22) |

| Unidirectional barbed§ | 3 | 100/91 | −0.22 | [−0.74, 0.29] | P = 0.04; I2 = 68% | Z = 0.85 (P = 0.40) |

| Bidirectional barbed§ | 1 | 32/31 | 0.31 | [−0.18, 0.81] | N/A | Z = 1.23 (P = 0.22) |

| COMPLICATIONS | ||||||

| Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy* | 3 | 109/102 | 2.79 | [0.89, 8.79] | P = 0.10; I2 = 62% | Z = 1.75 (P = 0.08) |

| Laparoscopic myomectomy* | 2 | 58/103 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy* | 2 | 50/74 | 0.70 | [0.24, 2.08] | N/A | Z = 0.63 (P = 0.53) |

| Cesarean delivery* | 2 | 166/100 | 0.69 | [0.34, 1.38] | P = 0.26; I2 = 20% | Z = 1.05 (P = 0.29) |

| Arthroplasty* | 4 | 290/298 | 1.19 | [0.58, 2.41] | P = 0.12; I2 = 48% | Z = 0.48 (P = 0.63) |

| Cosmetic surgery* | 2 | 259/259 | 2.47 | [1.50, 4.06] | P = 0.01; I2 = 83% | Z = 3.56 (P = 0.0004) |

| Gastric bypass* | 1 | 30/30 | 0.50 | [0.05, 5.02] | N/A | Z = 0.59 (P = 0.56) |

| Sacrocolpopexy* | 1 | 32/32 | 1.53 | [0.25, 9.38] | N/A | Z = 0.46 (P = 0.64) |

| Unidirectional barbed* | 7 | 428/419 | 2.13 | [1.35, 3.35] | P = 0.007; I2 = 72% | Z = 3.25 (P = 0.001) |

| Bidirectional barbed* | 9 | 516/529 | 0.96 | [0.61, 1.50] | P=0.63; I2 = 0% | Z = 0.17 (P = 0.86) |

¶MD= mean difference.

§SMD=standardized mean difference.

*OR=Odds ratio.

NA: Not applicable.

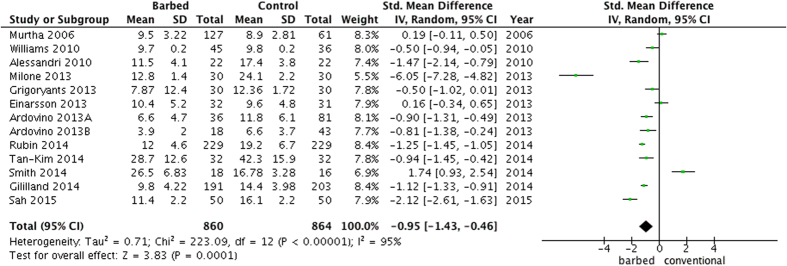

Suture time

With regard to the suture time (Fig. 2), a barbed suture could significantly reduce the suture time (SMD =−0.95, 95%CI −1.43 to −0.46, P = 0.0001), but the heterogeneity was high (P < 0.00001, I2 =95%) among 8 surgeries4,5,7,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. In the subgroup analysis by different surgeries, a shorter suture time in the barbed suture group was observed in laparoscopic myomectomy (MD =−5.50, 95%CI −7.03 to −3.97, P < 0.0001), cosmetic surgery (MD =−6.76, 95%CI −8.72 to −4.79, P < 0.00001), sacrocolpopexy (MD =−13.60, 95%CI −20.63 to −6.57, P = 0.0001), gastric bypass (MD =−11.30, 95%CI −12.23 to −10.37, P < 0.00001) and robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (MD =−0.10, 95%CI −0.19 to −0.01, P = 0.03). In the subgroup analysis by different types of barbed suture, a significantly decreased suture time (SMD =−1.75, 95%CI −2.69 to −0.81, P = 0.0003) was found in the unidirectional barbed suture groups.

Figure 2. A forest plot of suturing time with or without barbed suture.

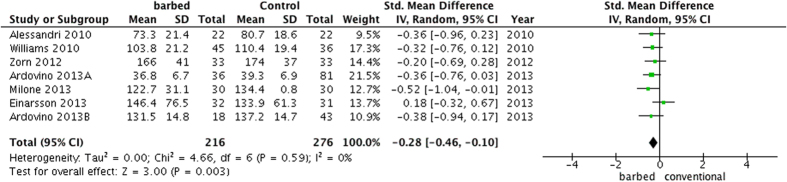

Operative time

In general, the operative time was significantly shorter (SMD =−0.28, 95%CI −0.46 to −0.10, P = 0.003) in the barbed suture group5,7,10,11,12,13,15 with lower heterogeneity (P = 0.59, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 3). In the subgroup analysis by different surgeries, a significantly shorter operative time in the barbed suture group was found in laparoscopic myomectomies (MD =−2.73, 95%CI −5.32 to −0.14, P = 0.04) and gastric bypass (MD = −11.70, 95%CI −22.83 to −0.57, P = 0.04). In the subgroup analysis by different types of barbed suture, a significant decreased operative time (SMD =−0.34, 95%CI −0.59 to −0.09, P = 0.001) was found in the unidirectional barbed suture groups.

Figure 3. A forest plot of operative time with or without barbed suture.

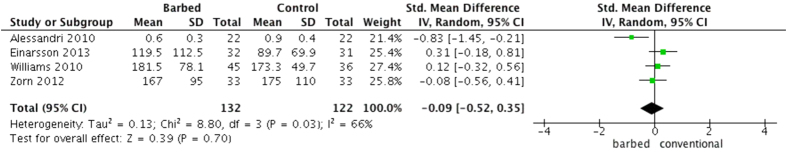

Estimated blood loss

The estimated blood loss (Fig. 4) changed insignificantly (SMD =−0.09, 95%CI −0.52 to 0.35, P = 0.70) with high heterogeneity (P = 0.03, I2 = 66%)5,7,10,13. In the subgroup analysis by different surgeries, estimated blood loss was significantly less in the barbed suture group only when referring to laparoscopic myomectomies (SMD =−0.83, 95%CI −1.45 to −0.21, P = 0.008). In the subgroup analysis by different types of barbed suture, no significant results were observed.

Figure 4. A forest plot of estimated blood loss with or without barbed suture.

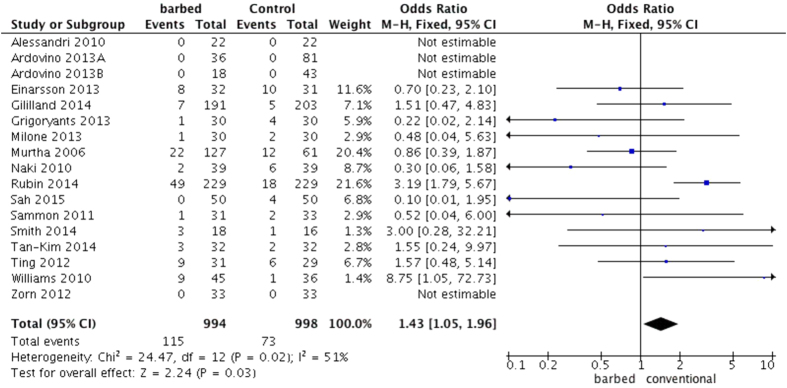

Postoperative complications

According to the pooled data, postoperative complications occurred more often in the barbed suture group than in the control group (OR = 1.43, 95%CI 1.05 to 1.96, P = 0.03)4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. (Heterogeneity: P = 0.02, I2 = 51%, Fig. 5) In the subgroup analysis by different surgeries, only cosmetic surgery appeared to significantly have more postoperative complications in the barbed suture group (SMD = 2.47, 95%CI 1.50 to 4.06, P = 0.0004). Rubin et al.17 suggested that suture extrusion was among the most common complications arising from mastopexy procedures (one of the cosmetic surgeries). In the subgroup analysis by different types of barbed suture, the unidirectional barbed suture groups had significantly more postoperative complications (OR = 2.13, 95%CI 1.35 to 3.35, P = 0.005). Because research performed by Rubin et al.17 involved more than one type of cosmetic surgery (abdominoplasty, mastopexy, and reduction mammoplasty) and William et al.7 had modified their technique for anastomosis of the bladder and urethral stump midway through the trials, we considered that these studies demonstrated more confounding variables. Moreover, a sensitivity analysis excluding these two studies showed no statistical change in postoperative complications between the conventional and unidirectional barbed sutures (OR = 0.30, 95%CI 0.09 to 0.98, P = 0.05, Supplementary Figure 9).

Figure 5. A forest plot of postoperative complications with or without barbed suture.

Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed using Begg’s funnel plots. The shape of the funnel plots appeared symmetric in the barbed vs. conventional suture, suggesting no evidence of publication bias (Supplementary Figures 10–13).

Discussion

Generally, barbed sutures reduced the suture time in nearly all types of surgeries, as well as the operative time. Although barbed sutures resulted in more postoperative complications, no significant change occurred concerning the estimated blood loss. Moreover, the results differed in different surgeries, and the bidirectional barbed suture appeared to be better than the unidirectional barbed suture.

To eliminate interference from confounding factors, we performed subgroup analysis by surgeries and barbed type, and the results were varied. First, our subgroup results showed a significant association between suture time and barbed suture in 5 types of surgeries (laparoscopic myomectomies, cosmetic surgeries, sacrocolpopexies, gastric bypasses and robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomies). Taken together, these findings suggested that the barbed suture significantly shortened the suture time in laparoscopic myomectomies (5.50 min), cosmetic surgeries (6.76 min), sacrocolpopexies (13.60 min), gastric bypasses (11.30 min) and robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomies (0.10 min). Thus the effectiveness need be evaluated based on particular surgeries.

In addition, although the overall effect of operative time decreased in barbed groups, a subgroup analysis suggested that only the operative time of laparoscopic myomectomies (2.73 min) and gastric bypasses (11.70 min) were significantly reduced, which was partially consistent with previous studies3,21 Furthermore, a subgroup analysis also indicated that the use of barbed sutures resulted in less blood loss in laparoscopic myomectomies, which differed from results obtained in a previous study21.

Regarding the postoperative complications, the subgroup analysis only indicated that the number of cosmetic surgeries was higher in the barbed suture groups than the control, whereas the pooled results obtained from other surgeries or studies reported no difference. This result may be due to the two studies14,17 of cosmetic surgeries, both of which had dermal closure performed on one side with the barbed suture and the conventional suture on the opposite side, which increased the risk of surgical site infection. Moreover, previous studies concerning gynecological surgeries reported that bowel obstruction might be attributable to the increased risk of either adhesions or inflammation caused by the barbs entrapped in the novel suture3,21.

Another concern our meta-analysis focused on is the comparison of different barbed suture types. Compared with the conventional suture, a unidirectional barbed suture decreased the suture and operative times significantly and also demonstrated more postoperative complications, whereas the pooled results of a bidirectional barbed suture did not statistically differ from the control in all outcomes. Thus, the bidirectional barbed suture appeared safer than the unidirectional sutures; although the pooled overall effect indicated no difference. Interestingly, the sensitivity analysis also showed no differences in postoperative complications between the control and either of the barbed groups. The most probable explanation for this result may be that the unidirectional barbed suture required more skillful surgeons. Because such sutures require cuts and re-stitches once suturing errors occurred, this can probably cause more damage to human tissue. Nevertheless, regarding the bidirectional barbed suture, when the barbs in one direction are in the wrong locations, then it can be modified using the other direction to maintain the tension.

Although there are three types of barbed suture commercially available, this study only identified research studies concerning the unidirectional barbed and bidirectional barbed suture; there were no RCTs on humans referring to the third type, Stratafix (STRATAFIX Knotless Tissue Control Devices, Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA). Thus, the feasibility and safety among different barbed sutures used in in vivo studies should be taken into consideration in the future22.

In addition to the favorable outcomes described above from pooled results, numerous other benefits of barbed sutures exist regardless of the patients or surgeons. For example, the barbed suture can eliminate knot tying and the speed of the placement of the sutures. Furthermore, eliminating the need for an assistant’s hand to follow the suture placement, enhancing the equal distribution of tension, and creating the possibility of improved scar cosmoses are also compelling validations for using this state-of-the-art technique.

Our pooled outcome provides convincing evidence for the relationship between the barbed suture and some important surgical indicators. However, caution should be taken to explain the pooled results due to the limitations of our study. (1) Relatively high heterogeneity among studies was estimated for surgical related outcomes, particularly in suture time and estimated blood loss. (2) Although our literature search was extensive, it did not cover conference publications and letters to the editor. (3) There was a lack of cost-effectiveness, cost-benefit, and cost-utility analyses, and the descriptive economic analysis of this study was imperfect. (4) Considering the high heterogeneity of all of the research studies, we performed the SMD for most of the outcomes.

Nevertheless, our results renew a latest meta-analysis on barbed sutures. To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date investigating the association between barbed and traditional sutures.

In conclusion, with the advantages of shorter suture and operative times, postoperative complications were likely to occur more often when using unidirectional barbed sutures. Future studies should also be performed to comprehensively analyze the effect on cost-effectiveness.

Methods

Study identification and selection

The MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library databases were searched using the following terms: “barbed” OR “knotless” AND “suturing” OR “suture” (last updated in Feb. 2015). To modify the results and to avoid publication bias, we also searched clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (last updated in Feb. 2015).

All studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (a) study design had to be a RCT based on human subjects; (b) patients underwent surgical operation; (c) interventions had to be conventional suture vs. barbed suture; and (d) studies should report at least one of the outcomes with detailed data, such as suture time, estimated blood loss, operative time, and postoperative complications. The following exclusion criteria were also applied: (a) conventional sutures were other materials, such as mesh or staple rather than smooth sutures; (b) abstracts or overlapped studies; and (c) studies published in languages other than English. The computer search was supplemented with manual searches for references of included studies.

Data Extraction and Outcome Measures

We imported the search results into bibliographic citation management software (EndNote X7, Thomson Reuters, USA). Two reviewers independently collected the data and reached a consensus on all items. The following items were extracted from each study if available: first author’s surname, publication year, original country, sample size, type of suture, and postoperative complications.

The main outcome measures chosen for the current meta-analysis were operative time, suture time, estimated blood loss or change in hemoglobin level and postoperative complications. Heterogeneity of the outcomes was assessed to confirm the appropriateness of combining individual studies.

Definition

Operative time was defined as the total time of surgery. Suture time was defined as the time needed for the completion of the surgical site incision, anastomosis time, and closure time. Estimated blood loss (ml) or change in hemoglobin level (g/dL) (different studies reported different indices of blood loss) was defined as the blood loss during the operation, and it was usually obtained from both the anesthesia records and/or the surgeons’ operative reports. After surgeries, postoperative complications of the suture were also recorded. Both unidirectional and bidirectional barbed sutures were evaluated together as the barbed suture category.

Methodological Quality Assessment

The risk of bias of included RCTs and was assessed following Cochrane recommendations, considering random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting23. We searched the protocol of each trial to assess the selective reporting. Publication bias was evaluated using the funnel plot.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The studies were divided into seven subgroups according to the seven different surgeries, which were also divided into two subgroups according to the two types of barbed suture; in addition, separate meta-analysis was performed within different subgroups. In all analyses, we estimated the pooled mean difference (MD) and standardized mean difference (SMD) to assess continuous data, while the pooled odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for the assessment of dichotomous data (postoperative complications). The pooled estimations regarding outcomes expressed as either dichotomous or continuous variables were calculated using the random effect model (postoperative complications using fixed effect model). The existence of statistical heterogeneity between the included studies was assessed using the χ2 test and I2 test. In addition, we also performed sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of the estimates and assessed the risk of publication bias using Begg’s funnel plots. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the software programs Review Manager (Version 5.3).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lin, Y. et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Knotless Barbed Sutures in the Surgical Field: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sci. Rep. 6, 23425; doi: 10.1038/srep23425 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant No. 81403276 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and grant No. JH20140066 from the Technology Support Program of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.F.L., S.K.L., L.D. and J.H. have directly participated in the planning, execution, or analysis of the study. Y.F.L. and S.K.L., performed data analysis and wrote the article; L.D. and J.H. provided critical revisions to the article. Y.F.L., S.K.L., L.D. and J.H. of this paper have read and approved the final version submitted.

References

- Paul M. D. Bidirectional barbed sutures for wound closure: evolution and applications. J Am Col Certif Wound Spec 1, 51–57, doi: 10.1016/j.jcws.2009.01.002 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff G. L. The history of barbed sutures. Aesthet Surg J 33, 12s–16s, doi: 10.1177/1090820x13498505 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavazzo C., Mamais I. & Gkegkes I. D. The Role of Knotless Barbed Suture in Gynecologic Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Surg Innov, doi: 10.1177/1553350614554235 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtha A. P. et al. Evaluation of a novel technique for wound closure using a barbed suture. Plast Reconstr Surg 117, 1769–1780, doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000209971.08264.b0 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri F., Remorgida V., Venturini P. L. & Ferrero S. Unidirectional barbed suture versus continuous suture with intracorporeal knots in laparoscopic myomectomy: a randomized study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 17, 725–729, doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.06.007 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naki M. M. et al. Comparative study of a barbed suture, poliglecaprone and stapler in Pfannenstiel incisions performed for benign gynecological procedures: a randomized trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 89, 1473–1477, doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.516815 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. B. et al. Randomized controlled trial of barbed polyglyconate versus polyglactin suture for robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy anastomosis: technique and outcomes. Eur Urol 58, 875–881, doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.07.021 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammon J. et al. Anastomosis during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: randomized controlled trial comparing barbed and standard monofilament suture. Urology 78, 572–579, doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.03.069 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting N. T., Moric M. M., Della Valle C. J. & Levine B. R. Use of knotless suture for closure of total hip and knee arthroplasties: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty 27, 1783–1788, doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.05.022 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorn K. C. et al. Prospective randomized trial of barbed polyglyconate suture to facilitate vesico-urethral anastomosis during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: time reduction and cost benefit. BJU Int 109, 1526–1532, doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10763.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardovino M. et al. Bidirectional barbed suture in laparoscopic myomectomy: clinical features. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 23, 1006–1010, doi: 10.1089/lap.2013.0103 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardovino M. et al. Bidirectional barbed suture in total laparoscopic hysterectomy and lymph node dissection for endometrial cancer: technical evaluation and 1-year follow-up of 61 patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 23, 347–350, doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0079 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einarsson J. I. et al. Barbed versus standard suture: a randomized trial for laparoscopic vaginal cuff closure. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 20, 492–498, doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.02.015 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryants V. & Baroni A. Effectiveness of wound closure with V-Loc 90 sutures in lipoabdominoplasty patients. Aesthet Surg J 33, 97–101, doi: 10.1177/1090820x12467797 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milone M. et al. Safety and efficacy of barbed suture for gastrointestinal suture: A prospective and randomized study on obese patients undergoing gastric bypass. Journal of Laparoendoscopic and Advanced Surgical Techniques 23, 756–759 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gililland J. M. et al. Barbed versus standard sutures for closure in total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter prospective randomized trial. J Arthroplasty 29, 135–138, doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.01.041 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin J. P. et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing absorbable barbed sutures versus conventional absorbable sutures for dermal closure in open surgical procedures. Aesthet Surg J 34, 272–283, doi: 10.1177/1090820x13519264 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. L., DiSegna S. T., Shukla P. Y. & Matzkin E. G. Barbed versus traditional sutures: closure time, cost, and wound related outcomes in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 29, 283–287, doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.05.031 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan-Kim J. et al. A randomized trial of vaginal mesh attachment techniques for minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy. Int Urogynecol J, doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2566-8 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah A. P. Is There an Advantage to Knotless Barbed Suture in TKA Wound Closure? A Randomized Trial in Simultaneous Bilateral TKAs. Clin Orthop Relat Res, doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4157-5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulandi T. & Einarsson J. I. The use of barbed suture for laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 21, 210–216, doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.09.014 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M. C. et al. Suture material for flexor tendon repair: 3-0 V-Loc versus 3-0 Stratafix in a biomechanical comparison ex vivo. J Orthop Surg Res 9, 72, doi: 10.1186/s13018-014-0072-9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P. et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343, d5928, doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.