Abstract

The traditional view of the structure-function paradigm is that a protein's function is inextricably linked to a well defined, three-dimensional structure, which is determined by the protein's primary amino acid sequence. However, it is now accepted that a number of proteins do not adopt a unique tertiary structure in solution and that some degree of disorder is required for many proteins to perform their prescribed functions. In this review, we highlight how a number of protein functions are facilitated by intrinsic disorder and introduce a new protein structure taxonomy that is based on quantifiable metrics of a protein's disorder.

Keywords: biophysics, conformational change, intrinsically disordered protein, protein folding, protein structure

How Do Folded Proteins Differ from Unfolded Proteins?

Proteins are dynamic biological molecules that are involved in virtually all cellular processes (1). At physiologic temperatures, proteins, like all polymers, sample a range of conformations that are a function of the macromolecular environment and the primary amino acid sequence of the protein in question. These considerations argue that a protein's “structure” is best described as a distribution over a conformational ensemble consisting of its thermally accessible structures. In this sense, a protein's conformational ensemble is intimately linked to its function.

Typically, proteins are characterized as being either folded or unfolded. This classification scheme is best understood from an analysis of the corresponding conformational ensembles. Folded proteins have thermally accessible states that are similar to the ensemble average, whereas unfolded (or disordered) proteins sample a relatively vast array of dissimilar conformations during their biological lifetime (2). The native state of a folded protein corresponds to a global energy minimum that is well separated from a panoply of high energy states. The flexibility of a folded protein is related to the width of this minimum energy well (Fig. 1A). Disordered proteins, by contrast, have energy surfaces that contain many local energy minima that are separated by low barriers (on the order of kBT), thereby ensuring rapid transition between structurally dissimilar states during the protein's biological lifetime (Fig. 1B). The result is a heterogeneous ensemble of thermally accessible conformations.

FIGURE 1.

Order and structure in proteins. A and B, schematic of an energy landscape for an ordered protein (A) and a disordered protein (B). Red tones indicate relatively high energy conformations, and blue tones indicate low energy conformations. C, order-structure continuum. Proteins with varying degrees of order and secondary structure propensity are shown in their approximate position on an order-structure continuum. Helices are shown in red, β-strands are shown in purple, and turns and unstructured regions are shown in green. Red, purple, and blue lines are used to indicate location along helical content, β-strand content, and order axes in three dimensions. Protein Data Bank (PDB) IDs left to right are: 2k3j (71), 1bh4 (72), PED Entry 9AAA (73), 1k7b (74), PED Entry 7AAA (75), 2kac (76), 2k3g (77), and 1qjp (78). PED refers to the Protein Ensemble Database (79).

Although the terms folded and unfolded provide a useful framework for everyday discourse among specialists, classifying proteins in this way does not capture the rich and beautiful complexity that underlies protein structure (3–5). Indeed, a more accurate description would entail a characterization of a protein's conformational ensemble. The importance of this realization is highlighted by the fact that not all folded proteins are created equal; i.e. some “folded” ensembles are more heterogeneous than others. Similarly, disordered proteins may have ensembles that exhibit preferences for particular structural features. These considerations reinforce the notion that quantitative metrics describing the heterogeneity within a protein's ensemble would provide a more comprehensive assessment of protein structure.

In a prior work, we introduced a continuous order parameter that describes the conformational heterogeneity in a structural ensemble using a quantitative metric of structural dissimilarity (3). The order parameter is 0 when the root mean square deviation (in terms of the Cartesian coordinates) between any two structures in an ensemble is infinite; i.e. each structure in the ensemble is infinitely different from every other structure. Conversely, the parameter is 1 when each structure in the ensemble is identical to every other structure. Although these upper and lower bounds are clearly theoretical, the notion is instructive. Proteins that are disordered have values close to 0, and those that are folded have values close to 1. Although a protein that is classified as being disordered necessarily falls on the low end of the disorder-order spectrum, it may very well be more ordered than another similarly classified protein.

An Order-Structure Continuum for Describing Protein Structure

Proteins that fall on the low end of the spectrum, by definition, sample a vast set of dissimilar structures in solution. However, such systems are not necessarily devoid of any secondary structural preferences, and therefore are not “unstructured.” This point is important because the nomenclature in the literature with respect to disordered proteins can be confusing. In our view, the term “unstructured” should be used to indicate a lack of regular secondary structure (e.g. α-helix or β-strand), whereas the term “disordered” should indicate a high level of conformational heterogeneity in the conformational ensemble. The fact that proteins can be ordered and yet be devoid of helical or β-strand structure speaks to the fact that these notions are not the same (6–8).

Disordered proteins can contain regions of local and/or transient residual secondary structure despite a lack of tertiary structure. Indeed, a number of disordered proteins fold into stable conformations upon binding their partners, and residually structured regions may act as binding sites that nucleate such reactions (9, 10). Hence, both the degree of order and the amount of secondary structure propensity impact a protein's function.

To more fully capture the complexity inherent to a macromolecule that needs varying degrees of flexibility to perform its biological function, a taxonomy is needed that goes past the binary descriptors of folded and unfolded (3, 11–13). A qualitative protein taxonomy that emphasizes the importance of both conformational plasticity and secondary structure formation in protein function is depicted in Fig. 1C. In this representation, the degree of order refers to the degree of conformational heterogeneity; i.e. proteins with a low degree of order can adopt a wide range of different conformations at equilibrium. The other axes quantify the ensemble average secondary structure content. Folded proteins are found within the high order realm of the continuum (which lies along the z axis). In the middle of the continuum, we find states that are typically referred to as molten globules (14, 15). These loosely defined proteins have more secondary structure but lack a stable tertiary fold. Near the origin of the three-dimensional order-structure continuum, we find a class of proteins that are natively disordered, the so-called intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs)2 (2, 16, 17). Although the axes in this continuum are qualitative, quantitative metrics have been proposed to quantify ensemble heterogeneity, either using atomistic representations for the structural ensemble (3, 18), or from a topological analysis of the energy surface (19). Additionally, secondary structure content can be computed as the percentage of amino acids in a protein with determined or predicted secondary structure, using a variety of metrics. Such metrics form a quantitative basis for a continuous classification scheme for protein structure.

Before moving on, we note that the location of a protein on this three-dimensional continuum has consequences for how that protein can be studied. Experimentally determined crystal structures of proteins correspond to an ensemble average. Because the conformational ensemble of folded proteins (low heterogeneity) contains structures that are similar to their average conformation, crystallographic structures of folded proteins provide great insight into the structural ensemble itself, and that protein's function. By contrast, crystallizing a disordered protein is not possible precisely because the process of crystallization requires the protein in question to adopt similar structures within the crystal environment (20–22). Structural modeling has therefore played an essential role in the study of very disordered systems (20, 23, 24). Dynamical simulations, for example, combined with restraints derived from NMR and/or SAXS experiments can be used to model important structural features of these proteins (21, 25, 26).

Moving forward, we illustrate how proteins at the far end of the order-structure continuum accomplish a variety of different functions. The examples presented below are by no means intended to be all-inclusive. Nevertheless, they do describe novel and interesting ways that proteins use disorder to accomplish tasks that would be difficult to perform without the considerable flexibility that disorder imparts.

Colicin E9

Colicins are a class of proteins produced by some Escherichia coli strains that provide a mechanism for bacteria to compete against similar or related strains when limited environmental resources are available (27, 28). After binding receptors on the surface of the outer membrane of the target cell, colicins are transported via specific translocators on the cell surface to the periplasmic space (27). Colicins then promote bacterial death either via destruction of important components of the peptidoglycan wall, via pore formation in the inner membrane, or by cleaving nucleic acids in the cytoplasmic space (27). Conformational disorder plays a crucial role in ensuring efficient translocation through target cell membranes.

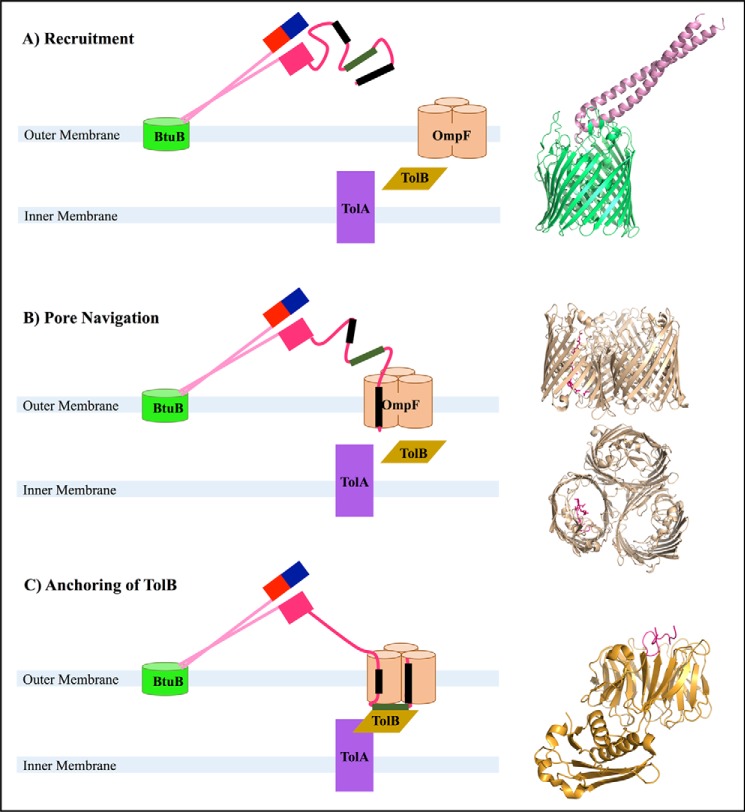

Colicins all have a common structure consisting of an N-terminal translocation domain (T), a receptor-binding domain (R), and a C-terminal cytotoxic domain (C) (27). After binding their cognate outer-membrane receptors, colicins recruit and assemble a translocon, a protein complex that facilitates translocation through the outer membrane surface (Fig. 2). Two proteins that are central components of the translocon are OmpF, which is found in the outer membrane, and TolB, which is found in the periplasmic space. Therefore, proper translocon assembly requires the extracellular protein, colicin, to recruit proteins in the outer membrane as well as periplasmic proteins, which are found on the other side of the outer membrane.

FIGURE 2.

Roles of colicin E9's intrinsically unstructured region within its T-domain (IUTD). In each panel, the domains of ColE9 are shown in pink tones: R, pale pink; C, red; T, carnation pink. The immunity protein, Im9, which inhibits the cytotoxic function of ColE9 in the extracellular space, is shown in blue bound to C. The ColE9-binding sites for OmpF are shown as black rectangles, and the binding site for TolB is shown as a green rectangle. A, after binding BtuB, the BtuB-ColE9 complex diffuses along the membrane to locate and bind OmpF, aided by the extended search radius provided by the IUTD. A structure of BtuB bound to the receptor domain from the similar protein ColE3 is shown to the right (PDB ID: 1ujw (80)). B, the IUTD forms an initial complex with one OmpF pore. Side and top views of IUTD residues 2–16 bound to OmpF are shown to the right (PDB ID: 3O0e chains A, C, E, and L (33)). C, the IUTD passes further through OmpF into the periplasm and weaves back into OmpF, binding OmpF in two pores. The TolB-binding site is now exposed to the periplasm, allowing it to bind TolB, which in turn binds TolA, forming the translocon. The structure of the TBE bound to TolB is shown to the right (PDB ID: 2ivz chains D and H (37)).

The role of disorder in colicin translocation has been best studied for the colicin ColE9 (29). Although both the R-domains and the C-domains of ColE9 are folded, NMR studies of the ColE9 T-domain suggest that its 83-residue N-terminal region is disordered and contains little to no appreciable propensity for secondary structure, findings that place this region at the very far end of the order-structure continuum (29). The R-domain of ColE9 forms a long coiled-coiled structure that binds the outer-membrane receptor, BtuB, of the target cell. When bound to BtuB, ColE9 forms an acute angle with the bacterial outer membrane in a manner such that the disordered region of the T-domain is projected off the outer membrane (Fig. 2A). In this orientation, the disordered region of the T-domain is optimally positioned to recruit, or seek out and bind, the translocator protein, OmpF (30).

The colicin receptor, BtuB, slowly diffuses laterally along the outer membrane, providing ColE9 with a vehicle for its search (31). A useful analogy is to view BtuB as a fishing boat, OmpF as fish, the R-domain of ColE9 as a fishing rod, and the disordered region of the T-domain as the fishing line (Fig. 2A) (32). The disordered T-domain region provides a search radius of ∼300 Å, which is centered at the end of the R-domain (33), and its rapid sampling of conformations allows ColE9 to search a much broader surface area for OmpF than would be possible through diffusion alone. Thus, the disordered region of the T-domain provides the same benefits for colicin's search for OmpF as recasting lines provides to anglers looking for fish. Indeed, early theoretical studies of the role of disorder in molecular recognition suggest that unfolding increases the effective capture radius of the molecule, thereby facilitating the fast formation of relatively weak contacts at large distances (34). Subsequent studies suggest that unfolded proteins need fewer encounter events (relative to folded proteins) to form stable complexes, and that this explains the relatively fast kinetic rates associated with disordered proteins (35). These observations argue that inherent disorder in the T-domain helps to ensure that OmpF is recruited quickly to ensure efficient translocation of ColE9 (36).

After binding OmpF, the T-domain must pass through the narrow porin to reach the periplasm. OmpF is a trimer containing three identical pores small enough to allow at most a 600-Da molecule to pass through at a time. Because of its intrinsic disorder, the 9-kDa disordered region of the T-domain is able to weave through a pore of OmpF into the periplasm (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the disordered region of the T-domain contains two OmpF interaction sites, residues 2–18 (OBS1) and 54–63 (OBS2), and a TolB-binding site, residues 32–47 (TBE), that facilitate pore entry (33, 37). As the OmpF pores are negatively charged, and OBS1 and OBS2 are positively charged, it has been proposed that an electrostatic interaction drives the entry of OBS1 into the pore and the formation of the initial complex between OBS1 and OmpF (33). Although the subsequent steps in pore navigation are not well understood, eventually the TBE site finds its way into the periplasmic space and to TolB (37). In later stages, OBS2 forms a lower affinity interaction with the initial pore using the same binding site as OBS1 initially used (33), and OBS1 winds back into a different pore on OmpF, likely limiting the movement of the now periplasmic TBE (Fig. 2C) (38).

Whether the TBE binds TolB before or after OBS1 winds back into OmpF is not yet known. However, it has been shown that ColE9 is more lethal to target cells when both OBS1 and OBS2 are present, indicating that the presence of both interactions with OmpF likely stabilizes the contact between the TBE and TolB, thereby also helping to stabilize the complex between TolA and TolB (38). Without disorder, it would not be possible for the T-domain to thread through the porin, bind the periplasmic protein TolB, and then re-enter the OmpF to stabilize the complex. The upshot is that the disordered T-domain helps to ensure that proteins on the periplasmic side of the outer membrane are stabilized in a position that is optimal for colicin translocation.

The interaction of colicin with TolA triggers the protein motive force, which is thought to drive subsequent unfolding of ColE9. The remaining steps of colicin C entry into the cytoplasm are not understood. It is clear, however, that disorder plays a role in the initial steps of ColE9 entry, and similar pathways are thought to be used by related colicins for cell entry.

4E-binding Protein 2

The 4E-binding protein 2 (4E-BP2; also known as PHAS-II, phosphorylated heat and acid stable protein regulated by insulin 2 (39)) protein acts as a switch to regulate translation and is critical for development and growth across all cell types (40). This protein converts between an unphosphorylated state, which inhibits translation, and a phosphorylated state, which allows translation (41). NMR studies have shown that this 120-residue protein is disordered in its unphosphorylated state (40). The unphosphorylated protein binds to and inhibits the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E, eIF4E, which is responsible for initiating translation during cell growth (42). 4E-BP2 competes with the scaffolding protein eIF4G for binding eIF4E; eIF4G promotes translation by facilitating the assembly of translation machinery, whereas 4E-BP2 inhibits translation by sterically blocking the binding site on eIF4E for eIF4G (43). Specifically, eIF4G and 4E-BP2 have a common 7-residue primary sequence motif (YXXXXLΦ, where Φ represents a hydrophobic amino acid and X represents any amino acid) that binds eIF4E (43–45). These competing proteins bind to overlapping sites on eIF4E, so that both cannot bind simultaneously (46, 47). Phosphorylation of 4E-BP2 weakens its binding affinity for eIF4E, which leads to increased binding of eIF4G to eIF4E, and an increased rate of translation (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

The 4E-BP2 protein (green, with the primary eIF4E-binding site shown in violet) is disordered in its unphosphorylated, unbound state. Upon binding eIF4E (shown in white), its primary binding site adopts a helical conformation, but the remaining residues remain largely disordered and exposed for phosphorylation (PDB ID: 3am7, 4E-BP2 residues 47–65). Phosphorylation of 4E-BP2 causes it to fold into a binding-incompetent β-strand structure (PDB ID: 2mx4, 4E-BP2 residues 47–62 (41)). The disordered ensemble was generated with Mollack with chemical shift data from Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) 19114 for non-phosphorylated 4E-BP2 residues 1–120 with an N-terminal MPLGSPEF tag (46).

Analyses of NMR chemical shifts indicate that the 7-residue eIF4E-binding site (residues 54–60) in unphosphorylated 4E-BP2 has transient helical structure when not bound to eIF4E, and is flanked by two small segments that have residual extended structure (46). Four other small regions (residues 1–5, 33–37, 86–89, and 96–105) are also predicted to have transient helicity (46). NMR heteronuclear NOEs are consistent with these observations, as their values are higher in these regions than expected for entirely disordered proteins, indicating transient local or tertiary structure (46). Thus, unphosphorylated 4E-BP2 has low order, but higher levels of secondary structure than the discussed region of ColE9, placing it farther from the origin in the helical content and β-strand content directions of the order-structure continuum.

Upon binding eIF4E, residues 54–60 in 4E-BP2 fold into an α-helix and residues 78–82 also form a transient interaction with eIF4E (46). NMR studies show that the rest of 4E-BP2 remains disordered in the eIF4E-bound state, and some regions actually become more disordered upon binding (40, 46). Despite remaining disordered, some changes in chemical shifts upon binding eIF4E are observed (46), and SAXS experiments suggest that 4E-BP2 becomes more compact upon binding (48).

Extracellular signaling for phosphorylation of 4E-BP2 by cellular kinases, e.g. through growth factors or mitogens, leads to a reduction in affinity of 4E-BP2 for eIF4E (41, 42, 49). Thus, phosphorylation disrupts eIF4E binding to 4E-BP2, thereby allowing eIF4G to bind free eIF4E, a process that promotes translation. 4E-BP2 is phosphorylated initially on residues Thr37 and Thr46 and later on residues Ser65 and Thr70 (49). The initial phosphorylation on Thr37 and Thr46 greatly weakens the interaction between 4E-BP2 and eIFE4, and subsequent phosphorylation of residues Ser65, Thr70, and Ser83 further lowers the affinity between 4E-BP2 and eIFE4 (41, 49)). Accompanying studies suggest that 4E-BP2 forms a four-strand β-structure upon phosphorylation of residues Thr37 and Thr46, and that this structure is further stabilized by the phosphorylation of Ser65, Thr70, and Thr83 (41). Residues 54–56, which form part of a helix when bound to eIFE4, are incorporated in one of the β-strands, and residues 58–60 form a disordered loop (Fig. 3) (41). Thus, phosphorylation of the disordered 4E-BP2 triggers its transformation into a conformation that is unfavorable for binding eIF4E (Fig. 3).

Although many IDPs fold into a stable complex upon binding their partners, 4E-BP2 is an example of a protein that remains largely disordered in its bound state, and this disorder is crucial to its function. The disorder of 4E-BP2 in both its unbound and eIF4E-bound state allows its phosphorylation sites to remain exposed (41, 46, 49). Phosphorylation of 4E-BP2 causes 4E-BP2 to fold into a β-structure, in which one of the β-strands involves residues that form a helix when bound to eIFE4 (41). The release of 4E-BP2 from eIF4E upon phosphorylation of 4E-BP2 is likely due to this conformational change, and thus phosphorylation can result in the rapid release of 4E-BP2 from eIFE4, permitting initiation of translation. In this way, the intrinsic disorder of 4E-BP2 when bound permits it to react quickly to hormonal signals calling for the initiation of translation.

NCBD

The nuclear co-activator-binding domain (NCBD) of the CREB-binding protein (CBP) is a transcriptional co-activator. This 59-residue domain within CBP (residues 2058–2116 of human CBP) interacts with a diverse set of proteins, including transcription factors and various elements of the transcriptional machinery (50, 51). Several experimental observations suggest that NCBD has poorly dispersed chemical shifts and weak long-range NOEs, features associated with a lack of stable tertiary structure (52–54). Despite this, circular dichroism spectra suggest that NCBD retains significant helical content (50). Given NCBD's high degree of native secondary structure coupled with its lack of a stable fold, this protein has been classified as a molten globule (52, 53, 55). A number of studies, however, suggest that the situation is likely more complex. NCBD has a hydrophobic core that has a sigmoidal unfolding curve in the presence of urea, and NMR relaxation data argue that it slowly interconverts between several conformations on the NMR time scale (54, 56). Unlike traditional IDPs that rapidly fluctuate between dissimilar conformations corresponding to local energy minima separated by low barriers, NCBD samples states separated by relatively large barriers, leading to longer transition times. In our parlance, the fact that NCBD samples distinct conformational states in solution on the millisecond time scale places it in the low order (relative to archetypal folded proteins) and high structure region of the order-structure continuum.

Two models for the hydrophobic core of NCBD have been proposed, NCBD-1 (54) and NCBD-2 (50), where the structure of NCBD-1 corresponds to a more highly populated conformer in the unfolded ensemble. In both models, the NCBD core contains three helices, whose orientations and lengths vary depending on the identity of their binding partners (Fig. 4) (55). NMR studies of unbound NCBD suggest that the protein fluctuates on a millisecond time scale between two conformational states, including a dominant state similar to conformation NCBD-1, in which helices 1 and 2 form contacts, and a less prevalent state in which this contact is replaced by interactions between helix 1 and 3, more similar to the conformation bound to interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) (56, 57) (Fig. 4). Molecular dynamics simulations of the unbound state have shown that NCBD samples a wide variety of conformations characterized by different orientations and lengths of its helices (58, 59). Long time-scale simulations indicated that NCBD samples conformations similar to each known bound structure at low rates. These simulations argue that the IRF-3 bound conformation is only rarely accessible from the unbound state, indicating that the presence of that binding partner may be necessary for NCBD to sample that state (58). A separate molecular dynamics simulation study of NCBD binding to its interaction domain on the human activator for thyroid hormone and retinoid receptors protein (ACTR) or IRF-3 indicated that NCBD samples its bound conformation for each of these partners much more readily in the presence of that partner than in its absence (59).

FIGURE 4.

Conformations of NCBD. Available NMR and x-ray structures of NCBD are shown in complex with different binding partners or in isolation, aligned according to helix 1. NCBD is colored white, with helix 1 in purple, helix 2 in yellow, and helix 3 in green. Binding partners are shown in blue. For visibility of NMR models, only one conformation of each binding partner is shown, whereas all NCBD conformations are shown. Clockwise from upper left, the PDB IDs are 2kkj (54), 1jjs (50), 2c52 (82), 2l14 (84), 1zoq (83), and 1kbh (53). Figures were made in PyMOL (81).

NCBD is a hub domain of CBP that interacts with many binding partners, and is known to bind different partners using different arrangements of its helices (Fig. 4). Overall, the ability of NCBD to sample different helical lengths and orientations enables it to bind a repertoire of distinct binding partners. The intrinsic low order facilitates these interactions, and its high secondary structure content ensures that it does not incur the significant entropic losses that are associated with having to adopt a folded state upon binding.

Conclusion

Our understanding of protein disorder and the role that it plays in protein function has blossomed over the past several decades. Knowledge of the ways in which disorder can add to the rich complexity of proteins has evolved for a number of proteins, and the growth of research in this area ensures that the rate of progress in this burgeoning field will only increase. In this minireview, we have attempted to highlight a few examples that illustrate how disorder can expand the repertoire of protein functions.

In addition to playing an important role in many biochemical processes, disordered proteins have been implicated in a number of diseases, both as pathogens and as chaperones (60–66). Thus, a better understanding of these proteins may provide a platform for the engineering of novel therapeutic agents (67, 68). More generally, an improved understanding of the relationship between a protein's primary sequence and its structural ensemble is essential for the design of novel proteins that could be used in technology and medicine. A crucial step in this direction involves an expansion in methods for studying the energetic landscape of proteins. Recent adaptions to crystallography and NMR are providing insight into partially stable molecular states, thus providing new glimpses into protein ensembles, albeit for proteins that lie in the more ordered region of the continuum (69, 70).

Our discussion has been framed within the context of an order-structure continuum for protein structure classification. In doing so, we strive to reinforce the realization that a binary classification of proteins as either “folded” or “unfolded” does not capture the wide variety of flexible architectures available to proteins (4, 5, 13). Our order-structure continuum provides a qualitative overview of the varying degree of order and secondary structure content among proteins, and here we have discussed examples of functions carried out by proteins that have varying degrees of order and secondary structure. Going forward, experimental methods to quantify the amount of disorder in a protein, especially under various physiological conditions, would lead to a better classification system, provide important grounds for insight into how a protein's flexibility enables its function, and guide the design of further experiments to study that protein's conformational ensemble. Overall, the ability to relate a protein's sequence to its conformational ensemble and its range of functions would enable exciting advances in biomedicine and bioengineering.

This work was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation (Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology (to V. M .B.)), the Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education of Brazil and Science without Borders (CAPES/CSF), the Lemann Foundation, and a Steven G. and Renee Finn Research Innovation Fellowship. This is the fourth article in the Thematic Minireview series “Intrinsically Disordered Proteins.” The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- IDP

- intrinsically disordered protein

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering

- TBE

- TolB-binding epitope

- CBP

- CREB-binding protein

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein

- NCBD

- nuclear co-activator-binding domain

- IUTD

- intrinsically unstructured region within the T-domain

- T-domain

- translocation domain

- R-domain

- receptor-binding domain

- C-domain

- C-terminal cytotoxic domain.

References

- 1. McCammon J. A., Gelin B. R., and Karplus M. (1977) Dynamics of folded proteins. Nature 267, 585–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wright P. E., and Dyson H. J. (1999) Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J. Mol. Biol. 293, 321–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fisher C. K., and Stultz C. M. (2011) Protein structure along the order-disorder continuum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10022–10025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uversky V. N. (2013) A decade and a half of protein intrinsic disorder: biology still waits for physics. Protein Sci. 22, 693–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marsh J. A., Teichmann S. A., and Forman-Kay J. D. (2012) Probing the diverse landscape of protein flexibility and binding. Curr. Opin Struct. Biol. 22, 643–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wood S. P., Tickle I. J., Treharne A. M., Pitts J. E., Mascarenhas Y., Li J. Y., Husain J., Cooper S., Blundell T. L., Hruby, et al. (1986) Crystal structure analysis of deamino-oxytocin: conformational flexibility and receptor binding. Science 232, 633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Savarin P., Guenneugues M., Gilquin B., Lamthanh H., Gasparini S., Zinn-Justin S., and Ménez A. (1998) Three-dimensional structure of κ-conotoxin PVIIA, a novel potassium channel-blocking toxin from cone snails. Biochemistry 37, 5407–5416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Skelton N. J., Garcia K. C., Goeddel D. V., Quan C., and Burnier J. P. (1994) Determination of the solution structure of the peptide hormone guanylin: observation of a novel form of topological stereoisomerism. Biochemistry 33, 13581–13592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee H., Mok K. H., Muhandiram R., Park K. H., Suk J. E., Kim D. H., Chang J., Sung Y. C., Choi K. Y., and Han K. H. (2000) Local structural elements in the mostly unstructured transcriptional activation domain of human p53. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29426–29432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Otieno S., and Kriwacki R. (2012) Probing the role of nascent helicity in p27 function as a cell cycle regulator. PLoS ONE 7, e47177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fuxreiter M., and Tompa P. (2012) Fuzzy complexes: a more stochastic view of protein function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 725, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dunker A. K., Babu M. M., Barbar E., Blackledge M., Bondos S. E., Dosztányi Z., Dyson H. J., Forman-Kay J., Fuxreiter M., Gsponer J., Han K.-H., Jones D. T., Longhi S., Metallo S. J., Nishikawa K., et al. (2013) What's in a name? Why these proteins are intrinsically disordered. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins 1, e24157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uversky V. N. (2013) Unusual biophysics of intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1834, 932–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ptitsyn O. (1987) Protein folding: hypotheses and experiments. J. Protein Chem. 6, 273–293 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohgushi M., and Wada A. (1983) 'Molten-globule state': a compact form of globular proteins with mobile side-chains. FEBS Lett. 164, 21–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dunker A. K., Bondos S. E., Huang F., and Oldfield C. J. (2015) Intrinsically disordered proteins and multicellular organisms. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 37, 44–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dunker A. K., Lawson J. D., Brown C. J., Williams R. M., Romero P., Oh J. S., Oldfield C. J., Campen A. M., Ratliff C. M., Hipps K. W., Ausio J., Nissen M. S., Reeves R., Kang C., Kissinger C. R., et al. (2001) Intrinsically disordered protein. J. Mol. Graph. Model 19, 26–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lyle N., Das R. K., and Pappu R. V. (2013) A quantitative measure for protein conformational heterogeneity. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 121907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chavez L. L., Onuchic J. N., and Clementi C. (2004) Quantifying the roughness on the free energy landscape: entropic bottlenecks and protein folding rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 8426–8432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burger V., Gurry T., and Stultz C. (2014) Intrinsically disordered proteins: where computation meets experiment. Polymers 6, 2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rauscher S., and Pomès R. (2010) Molecular simulations of protein disorder. Biochem. Cell Biol. 88, 269–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dyson H. J., and Wright P. E. (2004) Unfolded proteins and protein folding studied by NMR. Chem. Rev. 104, 3607–3622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tompa P., and Varadi M. (2014) Predicting the predictive power of IDP ensembles. Structure 22, 177–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rauscher S., Gapsys V., Gajda M. J., Zweckstetter M., de Groot B. L., and Grubmüller H. (2015) Structural ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins depend strongly on force field: a comparison to experiment. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 5513–5524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Varadi M., Vranken W., Guharoy M., and Tompa P. (2015) Computational approaches for inferring the functions of intrinsically disordered proteins. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eliezer D. (2009) Biophysical characterization of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kleanthous C. (2010) Swimming against the tide: progress and challenges in our understanding of colicin translocation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 843–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gratia A. (1925) On a remarkable example of antagonism between two stocks of colibacillus. C. R. Soc. Biol. 93, 1040–1041 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Collins E. S., Whittaker S. B., Tozawa K., MacDonald C., Boetzel R., Penfold C. N., Reilly A., Clayden N. J., Osborne M. J., Hemmings A. M., Kleanthous C., James R., and Moore G. R. (2002) Structural dynamics of the membrane translocation domain of colicin E9 and its interaction with TolB. J. Mol. Biol. 318, 787–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Housden N. G., Loftus S. R., Moore G. R., James R., and Kleanthous C. (2005) Cell entry mechanism of enzymatic bacterial colicins: porin recruitment and the thermodynamics of receptor binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 13849–13854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spector J., Zakharov S., Lill Y., Sharma O., Cramer W. A., and Ritchie K. (2010) Mobility of BtuB and OmpF in the Escherichia coli outer membrane: implications for dynamic formation of a translocon complex. Biophys. J. 99, 3880–3886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zakharov S. D., Sharma O., Zhalnina M., Yamashita E., and Cramer W. A. (2012) Pathways of colicin import: utilization of BtuB, OmpF porin and the TolC drug-export protein. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 1463–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Housden N. G., Wojdyla J. A., Korczynska J., Grishkovskaya I., Kirkpatrick N., Brzozowski A. M., and Kleanthous C. (2010) Directed epitope delivery across the Escherichia coli outer membrane through the porin OmpF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21412–21417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shoemaker B. A., Portman J. J., and Wolynes P. G. (2000) Speeding molecular recognition by using the folding funnel: the fly-casting mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8868–8873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang Y., and Liu Z. (2009) Kinetic advantage of intrinsically disordered proteins in coupled folding-binding process: a critical assessment of the “fly-casting” mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 393, 1143–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bonsor D. A., Grishkovskaya I., Dodson E. J., and Kleanthous C. (2007) Molecular mimicry enables competitive recruitment by a natively disordered protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 4800–4807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loftus S. R., Walker D., Maté M. J., Bonsor D. A., James R., Moore G. R., and Kleanthous C. (2006) Competitive recruitment of the periplasmic translocation portal TolB by a natively disordered domain of colicin E9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12353–12358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Housden N. G., Hopper J. T., Lukoyanova N., Rodriguez-Larrea D., Wojdyla J. A., Klein A., Kaminska R., Bayley H., Saibil H. R., Robinson C. V., and Kleanthous C. (2013) Intrinsically disordered protein threads through the bacterial outer-membrane porin OmpF. Science 340, 1570–1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu C., Pang S., Kong X., Velleca M., and Lawrence J. C. Jr. (1994) Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of PHAS-I, an intracellular target for insulin and growth factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 3730–3734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fletcher C. M., McGuire A. M., Gingras A. C., Li H., Matsuo H., Sonenberg N., and Wagner G. (1998) 4E binding proteins inhibit the translation factor eIF4E without folded structure. Biochemistry 37, 9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bah A., Vernon R. M., Siddiqui Z., Krzeminski M., Muhandiram R., Zhao C., Sonenberg N., Kay L. E., and Forman-Kay J. D. (2015) Folding of an intrinsically disordered protein by phosphorylation as a regulatory switch. Nature 519, 106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pause A., Belsham G. J., Gingras A. C., Donzé O., Lin T. A., Lawrence J. C. Jr., and Sonenberg N. (1994) Insulin-dependent stimulation of protein synthesis by phosphorylation of a regulator of 5′-cap function. Nature 371, 762–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mader S., Lee H., Pause A., and Sonenberg N. (1995) The translation initiation factor eIF-4E binds to a common motif shared by the translation factor eIF-4γ and the translational repressors 4E-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 4990–4997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marcotrigiano J., Gingras A. C., Sonenberg N., and Burley S. K. (1999) Cap-dependent translation initiation in eukaryotes is regulated by a molecular mimic of eIF4G. Mol. Cell 3, 707–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Altmann M., Schmitz N., Berset C., and Trachsel H. (1997) A novel inhibitor of cap-dependent translation initiation in yeast: p20 competes with eIF4G for binding to eIF4E. EMBO J. 16, 1114–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lukhele S., Bah A., Lin H., Sonenberg N., and Forman-Kay J. D. (2013) Interaction of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E with 4E-BP2 at a dynamic bipartite interface. Structure 21, 2186–2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Peter D., Igreja C., Weber R., Wohlbold L., Weiler C., Ebertsch L., Weichenrieder O., and Izaurralde E. (2015) Molecular architecture of 4E-BP translational inhibitors bound to eIF4E. Mol. Cell 57, 1074–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gosselin P., Oulhen N., Jam M., Ronzca J., Cormier P., Czjzek M., and Cosson B. (2011) The translational repressor 4E-BP called to order by eIF4E: new structural insights by SAXS. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 3496–3503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gingras A. C., Gygi S. P., Raught B., Polakiewicz R. D., Abraham R. T., Hoekstra M. F., Aebersold R., and Sonenberg N. (1999) Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism. Genes Dev. 13, 1422–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lin C. H., Hare B. J., Wagner G., Harrison S. C., Maniatis T., and Fraenkel E. (2001) A small domain of CBP/p300 binds diverse proteins: solution structure and functional studies. Mol. Cell 8, 581–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dyson H. J., and Wright P. E. (2005) Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Demarest S. J., Deechongkit S., Dyson H. J., Evans R. M., and Wright P. E. (2004) Packing, specificity, and mutability at the binding interface between the p160 coactivator and CREB-binding protein. Protein Sci. 13, 203–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Demarest S. J., Martinez-Yamout M., Chung J., Chen H., Xu W., Dyson H. J., Evans R. M., and Wright P. E. (2002) Mutual synergistic folding in recruitment of CBP/p300 by p160 nuclear receptor coactivators. Nature 415, 549–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kjaergaard M., Teilum K., and Poulsen F. M. (2010) Conformational selection in the molten globule state of the nuclear coactivator binding domain of CBP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12535–12540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ebert M. O., Bae S. H., Dyson H. J., and Wright P. E. (2008) NMR relaxation study of the complex formed between CBP and the activation domain of the nuclear hormone receptor coactivator ACTR. Biochemistry 47, 1299–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kjaergaard M., Poulsen F. M., and Teilum K. (2012) Is a malleable protein necessarily highly dynamic? The hydrophobic core of the nuclear coactivator binding domain is well ordered. Biophys. J. 102, 1627–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kjaergaard M., Andersen L., Nielsen L. D., and Teilum K. (2013) A folded excited state of ligand-free nuclear coactivator binding domain (NCBD) underlies plasticity in ligand recognition. Biochemistry 52, 1686–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Burger V. M., Ramanathan A., Savol A. J., Stanley C. B., Agarwal P. K., and Chennubhotla C. S. (2012) Quasi-anharmonic analysis reveals intermediate states in the nuclear co-activator receptor binding domain ensemble. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 70–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Knott M., and Best R. B. (2014) Discriminating binding mechanisms of an intrinsically disordered protein via a multi-state coarse-grained model. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 175102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Singh G. P. (2015) Association between intrinsic disorder and serine/threonine phosphorylation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PeerJ 3, e724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Olabode A. S., Jiang X., Robertson D. L., and Lovell S. C. (2015) Ebolavirus is evolving but not changing: no evidence for functional change in EBOV from 1976 to the 2014 outbreak. Virology 482, 202–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kumar S., Jena L., Daf S., Mohod K., Goyal P., and Varma A. K. (2013) hpvPDB: An Online Proteome Reserve for Human Papillomavirus. Genomics Inform. 11, 289–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Galvagnion C., Buell A. K., Meisl G., Michaels T. C. T., Vendruscolo M., Knowles T. P. J., and Dobson C. M. (2015) Lipid vesicles trigger α-synuclein aggregation by stimulating primary nucleation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 229–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Uversky V. N., Davé V., Iakoucheva L. M., Malaney P., Metallo S. J., Pathak R. R., and Joerger A. C. (2014) Pathological unfoldomics of uncontrolled chaos: intrinsically disordered proteins and human diseases. Chem. Rev. 114, 6844–6879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Uversky V. N., Roman A., Oldfield C. J., and Dunker A. K. (2006) Protein intrinsic disorder and human papillomaviruses: increased amount of disorder in E6 and E7 oncoproteins from high risk HPVs. J. Proteome Res. 5, 1829–1842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yadav L. R., Rai S., Hosur M. V., and Varma A. K. (2015) Functional assessment of intrinsic disorder central domains of BRCA1. J. Biomol Struct. Dyn. 33, 2469–2478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Srinivasan N., Bhagawati M., Ananthanarayanan B., and Kumar S. (2014) Stimuli-sensitive intrinsically disordered protein brushes. Nat. Commun 5, 5145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lotti M., and Longhi S. (2012) Mutual effects of disorder and order in fusion proteins between intrinsically disordered domains and fluorescent proteins. Mol. Biosyst. 8, 105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. van den Bedem H., and Fraser J. S. (2015) Integrative, dynamic structural biology at atomic resolution: it's about time. Nat. Methods 12, 307–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Keedy D. A., van den Bedem H., Sivak D. A., Petsko G. A., Ringe D., Wilson M. A., and Fraser J. S. (2014) Crystal cryocooling distorts conformational heterogeneity in a model Michaelis complex of DHFR. Structure 22, 899–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Banci L., Bertini I., Cefaro C., Ciofi-Baffoni S., Gallo A., Martinelli M., Sideris D. P., Katrakili N., and Tokatlidis K. (2009) MIA40 is an oxidoreductase that catalyzes oxidative protein folding in mitochondria. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 198–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Daly N. L., Koltay A., Gustafson K. R., Boyd M. R., Casas-Finet J. R., and Craik D. J. (1999) Solution structure by NMR of circulin A: a macrocyclic knotted peptide having anti-HIV activity. J. Mol. Biol. 285, 333–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mittag T., Marsh J., Grishaev A., Orlicky S., Lin H., Sicheri F., Tyers M., and Forman-Kay J. D. (2010) Structure/function implications in a dynamic complex of the intrinsically disordered Sic1 with the Cdc4 subunit of an SCF ubiquitin ligase. Structure 18, 494–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tonelli M., Peters R. J., James T. L., and Agard D. A. (2001) The solution structure of the viral binding domain of Tva, the cellular receptor for subgroup A avian leukosis and sarcoma virus. FEBS Lett. 509, 161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Weeks S. D., Baranova E. V., Heirbaut M., Beelen S., Shkumatov A. V., Gusev N. B., and Strelkov S. V. (2014) Molecular structure and dynamics of the dimeric human small heat shock protein HSPB6. J. Struct. Biol. 185, 342–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tadeo X., López-Méndez B., Trigueros T., Laín A., Castaño D., and Millet O. (2009) Structural basis for the aminoacid composition of proteins from halophilic archea. PLos Biol. 7, e1000257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Klages J., Kotzsch A., Coles M., Sebald W., Nickel J., Müller T., and Kessler H. (2008) The solution structure of BMPR-IA reveals a local disorder-to-order transition upon BMP-2 binding. Biochemistry 47, 11930–11939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pautsch A., and Schulz G. E. (2000) High-resolution structure of the OmpA membrane domain. J. Mol. Biol. 298, 273–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Varadi M., Kosol S., Lebrun P., Valentini E., Blackledge M., Dunker A. K., Felli I. C., Forman-Kay J. D., Kriwacki R. W., Pierattelli R., Sussman J., Svergun D. I., Uversky V. N., Vendruscolo M., Wishart D., Wright P. E., and Tompa P. (2014) pE-DB: a database of structural ensembles of intrinsically disordered and of unfolded proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D326–D335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kurisu G., Zakharov S. D., Zhalnina M. V., Bano S., Eroukova V. Y., Rokitskaya T. I., Antonenko Y. N., Wiener M. C., and Cramer W. A. (2003) The structure of BtuB with bound colicin E3 R-domain implies a translocon. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 948–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. DeLano W. L.(2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3r1., Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 82. Waters L., Yue B., Veverka V., Renshaw P., Bramham J., Matsuda S., Frenkiel T., Kelly G., Muskett F., Carr M., and Heery D. M. (2006) Structural diversity in p160/CREB-binding protein coactivator complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14787–14795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Qin B. Y., Liu C., Srinath H., Lam S. S., Correia J. J., Derynck R., and Lin K. (2005) Crystal structure of IRF-3 in complex with CBP. Structure 13, 1269–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lee C. W., Martinez-Yamout M. A., Dyson H. J., and Wright P. E. (2010) Structure of the p53 transactivation domain in complex with the nuclear receptor coactivator binding domain of CREB binding protein. Biochemistry 49, 9964–9971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]