Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is a major source of cellular ATP. The fluorescent probe JC-1 allows visualization of changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential produced by oxidative phosphorylation. JC-1-labeled H9 cells under an overconfluent condition were highly differentiated after subculture, suggesting that monitoring oxidative phosphorylation in live cells might facilitate the prediction of induced pluripotent stem cells and ES cells destined to lose their undifferentiated potency.

Keywords: Undifferentiated potency, Oxidative phosphorylation, Embryonic stem cells, JC-1-labeled cells

Abstract

Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is a major source of cellular ATP. Its usage as an energy source varies, not only according to the extracellular environment, but also during development and differentiation, as indicated by the reported changes in the flux ratio of glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation during embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation. The fluorescent probe JC-1 allows visualization of changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential produced by oxidative phosphorylation. Strong JC-1 signals were localized in the differentiated cells located at the edge of H9 ES colonies that expressed vimentin, an early differentiation maker. The JC-1 signals were further intensified when individual adjacent colonies were in contact with each other. Time-lapse analyses revealed that JC-1-labeled H9 cells under an overconfluent condition were highly differentiated after subculture, suggesting that monitoring oxidative phosphorylation in live cells might facilitate the prediction of induced pluripotent stem cells, as well as ES cells, that are destined to lose their undifferentiated potency.

Significance

Skillful cell manipulation is a major factor in both maintaining and disrupting the undifferentiation potency of human embryonic stem (hES) cells. Staining with JC-1, a mitochondrial membrane potential probe, is a simple monitoring method that can be used to predict embryonic stem cell quality under live conditions, which might help ensure the future use of hES and human induced pluripotent stem cells after subculture.

Introduction

Human embryonic stem (hES) cells can be maintained in an undifferentiated state by highly skilled researchers and engineers [1, 2]. In addition to skill development, reagents and automated instruments (e.g., kinase inhibitors [3, 4] and time-lapse analyses [2, 5]) have been developed to maintain the undifferentiated potencies of stem cells.

The flux ratio of glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation is a proposed indicator for undifferentiated/differentiated status in stem cells [6, 7]. Although oxidative phosphorylation is capable of producing larger amounts of ATP than glycolysis, most growing stem cells are considered to preferentially use glycolysis, rapidly producing ATP even under dense and anaerobic conditions [8]. Recent advances in instrumentation allow real-time monitoring of fluctuations in oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis by measuring the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR; acidification by lactate caused by glycolysis), respectively [9].

Oxidative phosphorylation occurs in mitochondria, with electron transfer chains producing a proton gradient between the mitochondrial membrane space and the inner matrix, which is ultimately used for ATP production [10]. JC-1, a fluorescent chemical probe, aggregates in mitochondria depending on their membrane potential, which produces aggregate-dependent red fluorescence [11]. We report the use of a simple method of monitoring cellular energy to identify hES cells that are destined to lose their undifferentiated potency.

Methods and Materials

Cell Manipulation

The hES cell line H9 [12] (WA09; WISC Bank, WiCell Research Institute, Madison, WI, http://www.wicell.org) and human induced pluripotent stem (hiPS) cell line 201B7 [13] (provided by Professor Shinya Yamanaka, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) were routinely maintained on mouse embryo fibroblast feeder cells, as previously described [4, 14–16]. For feeder-free culture, H9 cells were transferred onto 2 μg/cm2 fibronectin in a xeno-free hESF-FX medium (PCT/JP2011/004691) that is essentially a modified hESF-9 medium [4, 17, 18].

When the cells were passaged for an undifferentiated state, differentiated cell colonies were carefully removed under the microscope (carefully maintained). When the cells were passaged for the experiments, the cell colonies were dissociated into smaller clumps without any handling (poorly maintained).

All use of hES cells was approved by the ethical review board at our institute and adhered to the guidelines from the Japanese Ministries. Because hepatic cells are helpful to examine nutritional responses, the mouse hepatoma cell line AML-12 was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, http://www.atcc.org) and was maintained as previously described [2, 16, 19].

Reagents

H9 cell OCR and ECAR were monitored in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 0.5 mM glutamine using an extracellular flux analyzer (FX24e; Seahorse Biosciences, North Billerica, MA, http://www.seahorsebio.com). Oligomycin, rotenone, antimycin A, and carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) were also obtained from Seahorse Biosciences (Billerica, MA). H9 cells in hESF-FX medium were incubated with 0.5 μM JC-1 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, http://www.lifetechnologies.com) for 15 minutes. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed using a cell sorter (SH800Z; Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan, http://www.sony.com). Immunocytochemistry was performed using anti-OCT3/4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, http://www.scbt.com) and vimentin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com) antibodies, as previously described [4, 16]. Time-lapse imaging was performed using Biostation CT (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan, http://www.nikon.com). Each signal was taken using a monochrome CCD camera and colored using Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, http://www.adobe.com).

Results

Monitoring OCR/ECAR in H9 Cells

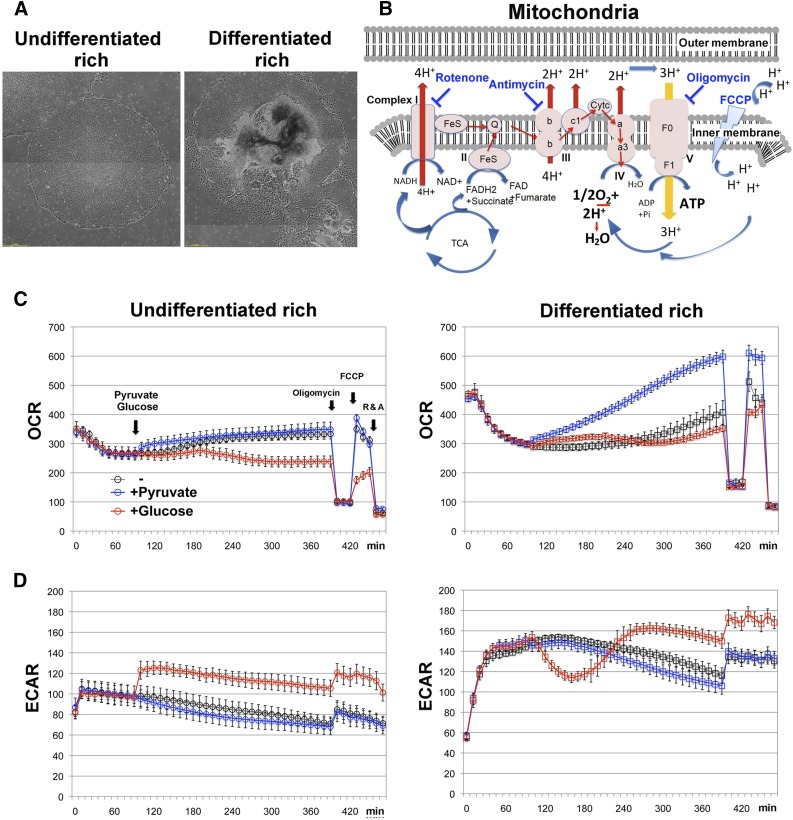

Using feeder-free H9 hES cells, we examined whether the glycolysis/oxidative phosphorylation ratio was influenced by the quality of cell manipulation (carefully or poorly maintained, described in the Materials and Methods section). Two populations were prepared from different subcultures (typically, undifferentiated-rich and differentiated-rich cell populations; Figure 1A), and then OCR and ECAR were monitored. To confirm whether oxygen consumption was the result of mitochondrial electron transfer, a mito-stress test (oligomycin-FCCP-rotenone/antimycin; Figure 1B) was conducted after the OCR measurements.

Figure 1.

OCR and ECAR in feeder-free H9 hES cells. (A): Phase-contrast images of H9 cells that were either carefully or poorly maintained, which potentially produced undifferentiated- or differentiated-enriched cell populations, respectively. (B): Mitochondrial electron transport chain oxidative phosphorylation. Respiratory toxin target sites are indicated. OCR (C) and ECAR (D) were measured in semiconfluent H9 cells in a glucose/pyruvate-free medium. After 10-cycle measurements, 5 mM glucose or 4 mM pyruvate was added to the culture medium, and the cells were subjected to a mito-stress test (oligomycin-FCCP-rotenone and antimycin A). Two days before assay, the cells were plated in 24-well plates specialized for the extracellular flux analyzer (eight wells per condition). Because some wells accidentally produced extraordinary values, data (four of eight wells) in every midrange under each condition were selected. Data are reported as the mean ± SEM. Abbreviations: ECAR, extracellular acidification rate; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone; OCR, oxygen consumption rate.

When H9 cells were incubated with pyruvate- and glucose-free media, OCR initially decreased and then gradually recovered (Fig. 1C, left). The addition of pyruvate to these cells slightly upregulated OCR, but the addition of glucose inhibited OCR recovery and upregulated ECAR (Fig. 1D). However, the results of these trials were very different using H9 cells that were poorly manipulated. In these cells, the addition of pyruvate strongly enhanced OCR in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1C, right). Curiously, supplemental glucose also enhanced OCR in poorly manipulated H9 cells but decreased ECAR at an early phase (Fig. 1D, right), suggesting that the poorly manipulated H9 cells preferentially used mitochondria, irrespective of the energy sources.

H9 Cell Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

OCR enhancement is the result of activated oxidative phosphorylation accompanied by an increase in mitochondrial membrane potential, which can be monitored in living cells using the fluorescent probe JC-1 (supplemental online Fig. 1A). Examples of its use in mouse hepatoma AML-12 cells are shown in supplemental online Figure 1B and 1C. JC-1 produces a red fluorescence when it forms multimers within the mitochondria in response to an elevated membrane potential. In contrast, free JC-1 produces a green fluorescence in the cell cytoplasm.

Next, we used JC-1 to stain H9 cell populations that were either classified into potentially undifferentiation-rich (supplemental online Fig. 1D) or differentiation-rich (supplemental online Fig. 1E). The cells located at the edge of colonies were strongly positive for JC-1 (multimers), indicating that the cells having high membrane potential. Potentially differentiated cells that were located outside colonies (supplemental online Fig. 1D, arrow) and in aggregate-like structures (supplemental online Fig. 1E) were also positive for JC-1 (multimers). FACS analyses indicated that differentiation-rich populations contained cells with a wide range of mitochondrial membrane potentials compared with undifferentiation-rich populations. In later experiments, we monitored only JC-1 multimers’ red signals.

Because H9 cell OCR depends on the specific medium conditions (Fig. 1C), we examined JC-1 signal intensity after medium refreshment (supplemental online Fig. 2). Mitochondrial membrane potentials (JC-1 signal intensity) in H9 cells was elevated after the medium change, suggesting that the medium change might obfuscate the evaluation of cell quality expected by JC-1 staining. Thus, JC-1 was added just at the medium change and removed after 20 minutes in later experiments.

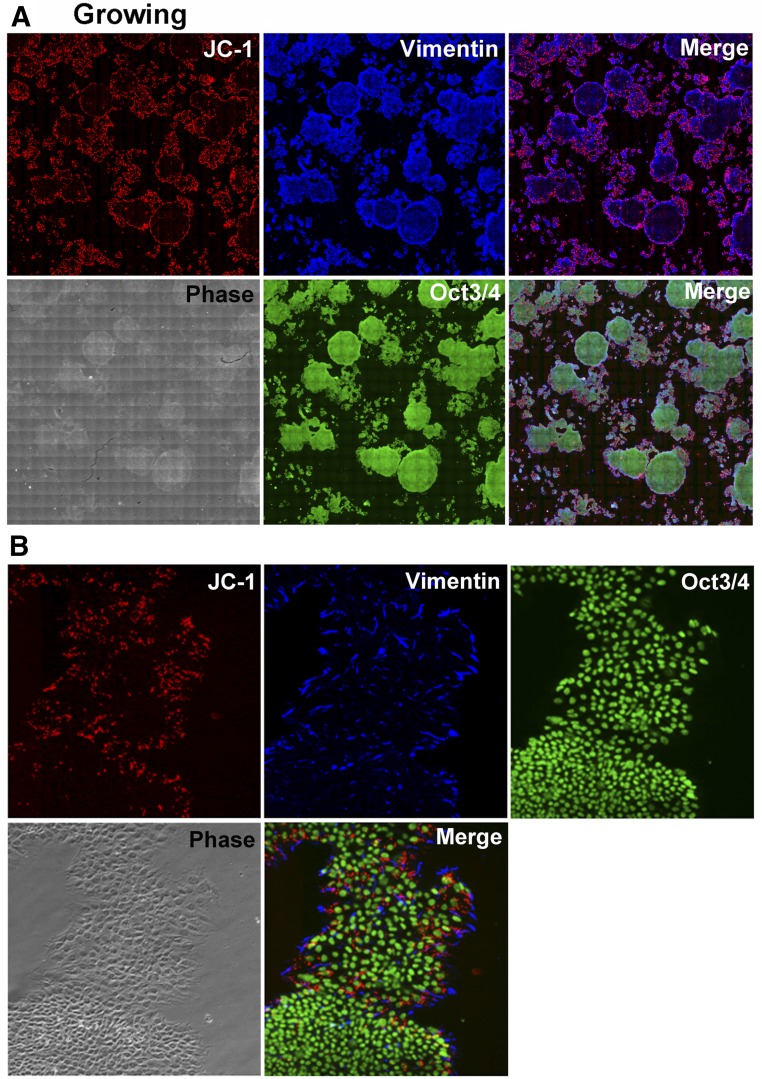

To define the relationship between JC-1 intensity and cell differentiation status, H9 cells were stained with anti-vimentin (an early differentiation maker [15, 20]) and anti-OCT-3/4 (a differentiation maker [13]). The JC-1 signals were highly overlapped with those of vimentin (Fig. 2A). High magnification (Fig. 2B) suggested that despite obvious differences in cell appearance in a phase contrast image, OCT-3/4 could not distinguish between the two cell populations. However, JC-1 and vimentin could identify large-type cells (the upper population) and cells located at edge of the lower colony.

Figure 2.

A variety of mitochondrial membrane potential in H9 cell population. (A): JC-1-labeled H9 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline and subjected to vimentin and OCT-3/4 staining. One image was constructed of 400 images (magnification, ×100). The upper merge is JC-1 (multimers) and vimentin, and the lower is triple. (B): High magnification (magnification, ×100).

Fate of JC-1-Positive Cells

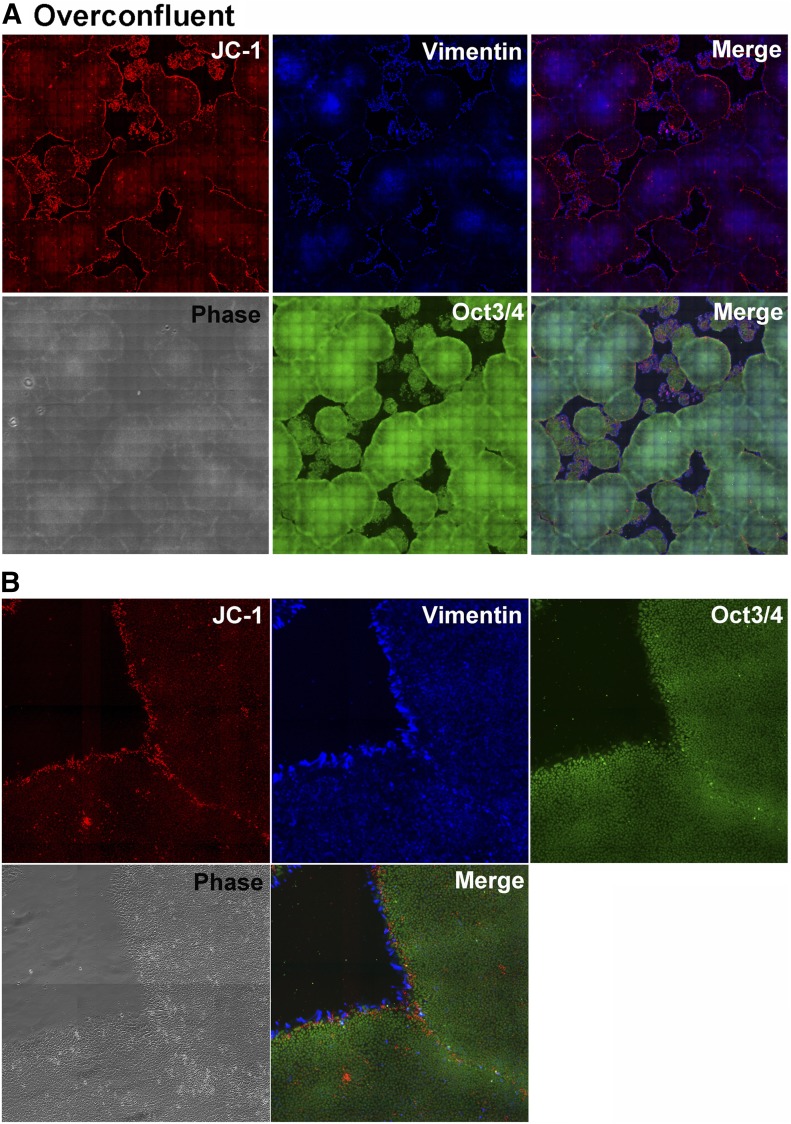

When H9 cells were in an overconfluent condition, the cells located inside undifferentiated colonies were negative for JC-1 (Fig. 3A). In contrast, some boundaries between colonies revealed JC-1 signals (Fig. 3B). When the boundaries were obviously observed under a phase-contrast image (supplemental online Fig. 3), JC-1 signal intensity increased. However, when the cells labeled with JC-1 in an overconfluent condition were subcultured onto a new dish, the JC-1-positive cells had converted into potentially differentiated cells and had drifted away from the colonies (supplemental online Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

A variety of mitochondrial membrane potentials in an H9 cell population in overconfluent condition. (A): JC-1-labeled H9 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS and subjected to vimentin and Oct3/4 staining. One image was constructed of 400 images (magnification, × 100). The upper merge is JC-1 (multimers) and vimentin, and the lower is triple. (B): High magnification (magnification, × 100).

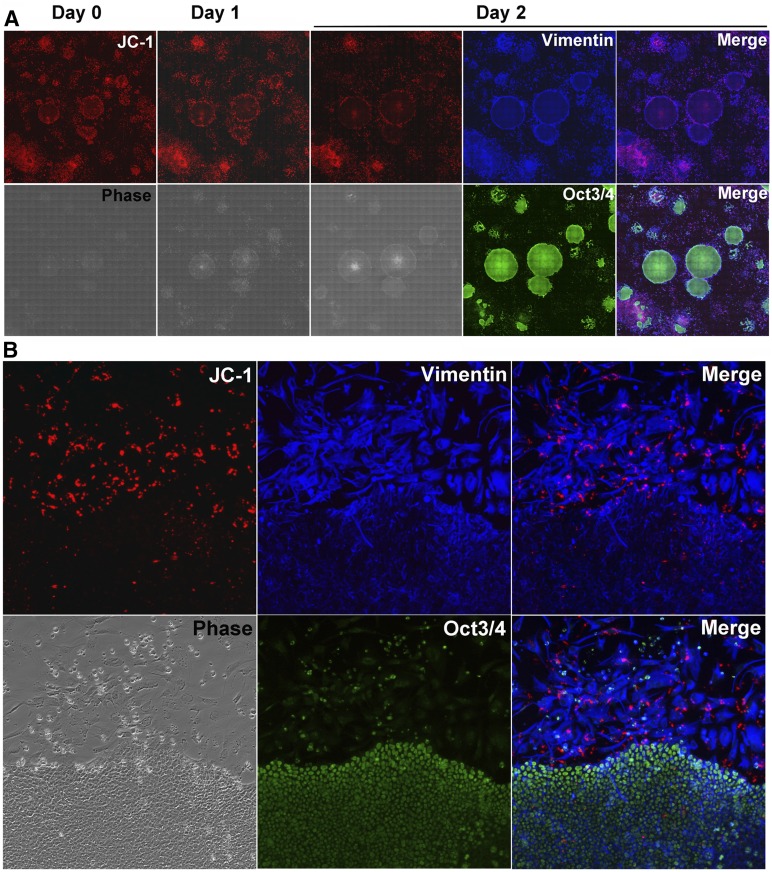

Finally, we traced JC-1-labeled H9 cells using time-lapse imaging (Fig. 4A). JC-1-labeled cells that had been located at the edge of colonies nestled along with the edge of growing colonies were finally identified as vimentin-positive and OCT-3/4-negative cells (Fig. 4B). JC-1 labeling might also be helpful for labeling hiPS cells (supplemental online Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Time-lapse imaging of JC-1-positive cells. (A): The JC-1 (multimers)-stained cells that were monitored every 24 hours and fixed at day 2 for vimentin and OCT-3/4 staining. (B): High magnification (magnification, ×100).

Discussion

A general evaluation of the flux ratio of glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation was monitored over approximately 1 hour to determine the relationship between preferential glycolysis and cell undifferentiation status [21, 22]. The measurement of OCR/ECAR over a longer period of approximately 6 hours revealed a dynamic hES cell adaptation to the culture conditions that was also dependent on their undifferentiation/differentiated state (i.e., the “cell quality of hES cells”). As expected, low-quality H9 cells, typically overgrown, or early differentiated cells characterized by vimentin staining preferentially used oxidative phosphorylation. However, high-quality H9 cells that were undifferentiated in freshly prepared media were also capable of using oxidative phosphorylation and adapting their mitochondria to lower nutrient conditions (glucose and pyruvate-free media).

The mitochondrial membrane potential was higher in cells at the edge of colonies than in those within the colonies, suggesting that the cells at the edges of colonies can uptake nutrients or oxygen more easily compared with cells in tight contact with each other in the inner colonies. Alternatively, similar to occurrences in embryoid bodies [23], the collision and fusion of colonies through nutrient consumption can prompt cells that are located at the colony edge to use mitochondria. In contrast, cells within the colonies might downregulate their mitochondrial activity. These metabolic polarizations [24] can also be caused by poor cell handling. Cells that are destined to lose their undifferentiated state might voluntarily withdraw from colonies, suggesting that minimizing the generation of cells with excess mitochondrial capacity is important for hES maintenance, which might also be applicable for hiPS cells.

Conclusion

Skillful cell manipulation is a major factor in both maintaining and disrupting the undifferentiation potency of hES cells. JC-1 staining is a simple monitoring method that can be used to predict ES and iPS cell qualities that could help ensure the future use of these stem cells after subculture.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mai Kagawa for technical support. This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (Grant 2013-2017 to M.K.F., Grant 2014-2016 to H.T.).

Author Contributions

A.K. and Y.I.: embryonic stem cell characterization; M.S. and K.Y.: embryonic stem cell preparation; H.T.: data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; M.K.F.: data analysis and interpretation.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bhatia H, Sharma R, Dawes J, et al. Maintenance of feeder free anchorage independent cultures of ES and iPS cells by retinol/vitamin A. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:3002–3010. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suga M, Kii H, Niikura K, et al. Development of a monitoring method for nonlabeled human pluripotent stem cell growth by time-lapse image analysis. Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 2015;4:720–730. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watanabe K, Ueno M, Kamiya D, et al. A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:681–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinehara M, Kawamura S, Tateyama D, et al. Protein kinase C regulates human pluripotent stem cell self-renewal. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith ZD, Nachman I, Regev A, et al. Dynamic single-cell imaging of direct reprogramming reveals an early specifying event. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folmes CD, Dzeja PP, Nelson TJ, et al. Metabolic plasticity in stem cell homeostasis and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:596–606. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi HW, Kim JH, Chung MK, et al. Mitochondrial and metabolic remodeling during reprogramming and differentiation of the reprogrammed cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1366–1373. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito K, Suda T. Metabolic requirements for the maintenance of self-renewing stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:243–256. doi: 10.1038/nrm3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu M, Neilson A, Swift AL, et al. Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C125–C136. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koopman WJ, Distelmaier F, Smeitink JA, et al. OXPHOS mutations and neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2013;32:9–29. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smiley ST, Reers M, Mottola-Hartshorn C, et al. Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate-forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3671–3675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amit M, Carpenter MK, Inokuma MS, et al. Clonally derived human embryonic stem cell lines maintain pluripotency and proliferative potential for prolonged periods of culture. Dev Biol. 2000;227:271–278. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinehara M, Kawamura S, Mimura S, et al. Protein kinase C-induced early growth response protein-1 binding to SNAIL promoter in epithelial-mesenchymal transition of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:2180–2189. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mimura S, Suga M, Liu Y, et al. Synergistic effects of FGF-2 and activin A on early neural differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2015;51:769–775. doi: 10.1007/s11626-015-9909-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furue MK, Na J, Jackson JP, et al. Heparin promotes the growth of human embryonic stem cells in a defined serum-free medium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13409–13414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806136105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusuda Furue M, Tateyama D, Kinehara M, et al. Advantages and difficulties in culturing human pluripotent stem cells in growth factor-defined serum-free medium. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2010;46:573–576. doi: 10.1007/s11626-010-9317-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh Y, Sanosaka M, Fuchino H, et al. Salt inducible kinase 3 signaling is important for the gluconeogenic programs in mouse hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:17879–17893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.640821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ginis I, Luo Y, Miura T, et al. Differences between human and mouse embryonic stem cells. Dev Biol. 2004;269:360–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varum S, Rodrigues AS, Moura MB, et al. Energy metabolism in human pluripotent stem cells and their differentiated counterparts. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamai M, Yamashita A, Tagawa Y. Mitochondrial development of the in vitro hepatic organogenesis model with simultaneous cardiac mesoderm differentiation from murine induced pluripotent stem cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2011;112:495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gassmann M, Fandrey J, Bichet S, et al. Oxygen supply and oxygen-dependent gene expression in differentiating embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2867–2872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H, Jang H, Kim TW, et al. Core pluripotency factors directly regulate metabolism in embryonic stem cell to maintain pluripotency. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2699–2711. doi: 10.1002/stem.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.