Abstract

Background

Septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint is rare. It can be associated with serious complications such as osteomyelitis, chest wall abscess, and mediastinitis. In this report, we describe a case of an otherwise healthy adult with septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint with chest wall abscess.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old Japanese man presented to our hospital complaining of pain and erythema near the right sternoclavicular joint. Despite 1 week of oral antibiotics, his symptoms did not improve. Computed tomography revealed an abscess with air around the right pectoralis major muscle. After being transferred to a tertiary hospital, emergency surgery was performed. Operative findings included necrotic tissue around the right sternoclavicular joint and sternoclavicular joint destruction, which was debrided and packed open. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus was identified in blood and wound cultures. Negative pressure wound therapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy were performed for infection control and wound healing. The patient’s general condition improved, and good granulation tissue developed. The wound was closed using a V-Y flap on hospital day 48. The patient has been free of relapse for 3 years.

Conclusions

Septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint is an unusual infection, especially in otherwise healthy adults. Because it is associated with serious complications such as chest wall abscess, prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are required.

Keywords: Sternoclavicular joint septic arthritis, Chest wall abscess, Sepsis, Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO2)

Background

The sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) is an unusual site of septic arthritis. It is involved in only 0.5–1.0 % of all joint infections and in less than 0.5 % of joint infections in healthy patients [1–4]. Common risk factors for SCJ septic arthritis include intravenous drug use (21 %), infection at a distant site (15 %), diabetes mellitus (13 %), trauma (12 %), and an infected central venous line (9 %). No risk factors were found in 23 % of patients with SCJ septic arthritis [1]. SCJ septic arthritis may lead to serious complications such as osteomyelitis [5], chest wall abscess [6–8], mediastinitis [9], or myositis [4]. Management of SCJ septic arthritis consists of surgical debridement and intravenous antibiotics [3, 11]. In this report, we describe a case of an otherwise healthy adult with SCJ septic arthritis with chest wall abscess.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old Japanese man presented to our hospital complaining of pain and erythema near the right SCJ. He had no risk factors for SCJ septic arthritis such as intravenous drug use, infection at a distant site, diabetes mellitus, trauma, laceration, or valvular heart disease. His past medical history and family history were noncontributory. Oral levofloxacin was started. One week later, he went to another hospital for medical care because his symptoms had not improved. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed an abscess with air around the right pectoralis major muscle. He was transferred to a tertiary center for surgical care.

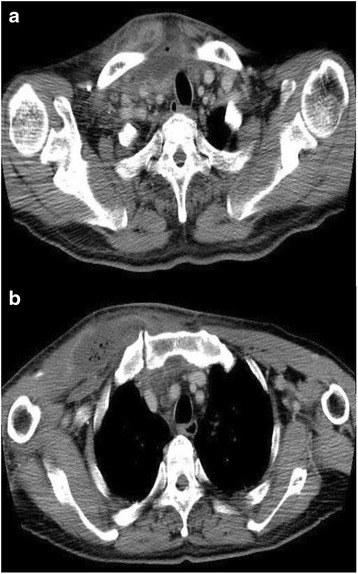

His physical examination revealed a body temperature of 39.3 °C, heart rate of 100 beats per minute, and blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg. Signs of inflammation such as redness, swelling, and tenderness over the right SCJ (Fig. 1) were present. His white blood cell count was 14,060/μl, and his C-reactive protein level was 17.5 mg/dl (Table 1). Repeat CT revealed an extensive abscess with air, involving the right pectoralis major muscle, right SCJ, retrosternal region, and right sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Chest findings on admission. Redness and swelling of skin localizing to the sternoclavicular joint are shown

Table 1.

Laboratory data on admission

| Laboratory parameters | Test results |

|---|---|

| TP | 4.2 g/dl |

| Alb | 2.2 g/dl |

| CPK | 127 IU/L |

| AST | 45 IU/L |

| ALT | 28 IU/L |

| LDH | 239 IU/L |

| ALP | 538 IU/L |

| γ-GTP | 81 IU/L |

| Amy | 16 IU/L |

| Cre | 0.80 mg/dl |

| BUN | 15.7 mg/dl |

| TG | 122 mg/dl |

| T-Chol | 85 mg/dl |

| T-Bil | 2.9 mg/dl |

| D-Bil | 1.7 mg/dl |

| Na+ | 139 mEq/L |

| K+ | 3.2 mEq/L |

| Cl− | 103 mEq/L |

| Mg | 1.9 mg/dl |

| Ca2+ | 7.1 mg/dl |

| IP | 3.1 mg/dl |

| CRP | 17.5 mg/dl |

| HbA1c | 5.7 % |

| Arterial blood gas | |

| FiO2 | 0.6 |

| pH | 7.51 |

| pCO2 | 33.0 mmHg |

| pO2 | 116.0 mmHg |

| BE | 3.2 mmol/L |

| Lactate | 7 mg/dl |

| WBC | 14,060/μl |

| RBC | 356 × 104/μl |

| Hb | 11.0 g/dl |

| Hct | 31.9 % |

| Plt | 14.6 × 104/μl |

| PT | 15.0 seconds |

| aPTT | 33.5 seconds |

| Fibrinogen | 683 mg/dl |

| FDP | 14.2 μg/dl |

| d-dimer | 7.2 μg/dl |

| AT-III | 49 % |

| Antinuclear antibody | Negative |

| Rheumatoid factor | Negative |

Alb albumin, ALP alkaline phosphatase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, Amy amylase, aPTT activated partial thromboplastin time, AST aspartate aminotransferase, AT-III antithrombin III, BE base excess, BUN blood urea nitrogen, Ca 2+ calcium, Cl − chloride, CPK creatine phosphokinase, Cre creatinine, CRP C-reactive protein, D-Bil direct bilirubin, FDP fibrin degradation products, FiO 2 fraction of inspired oxygen, γ-GTP γ-glutamyl transferase, Hb hemoglobin, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin A1c, Hct hematocrit, IP inorganic phosphorus, K + potassium, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, Mg magnesium, Na + sodium, pCO 2 partial pressure of carbon dioxide, Plt platelets, pO 2 partial pressure of oxygen, PT prothrombin time, RBC red blood cells, T-Bil total bilirubin, T-Chol total cholesterol, TG triglycerides, TP total protein, WBC white blood cells

Fig. 2.

Computed tomographic scans of the chest on admission. Computed tomography of the chest detected an abscess with air located below the thyroid gland and involving the right pectoral major muscle around the right sternoclavicular joint (a, b), as well as disaggregation of the right sternoclavicular joint (b)

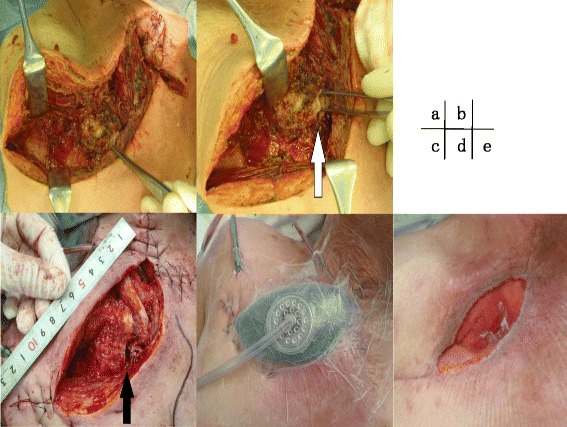

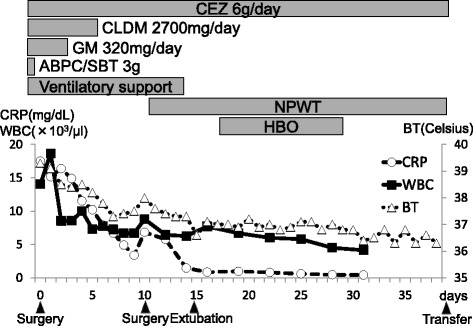

Emergency surgical debridement was performed. The skin incision began at the right border of the thyroid and extended to the head of the right clavicle. Operative findings included necrosis of parts of the right pectoralis major and minor muscles and the right SCJ. The patient also had right SCJ destruction. The necrotic pectoralis major and minor muscles and parts of the clavicle and manubrium near the SCJ that had become detached were debrided. The cavity was irrigated and packed open (Fig. 3). An initial Gram stain revealed gram-positive cocci. Ampicillin/sulbactam, which was given preoperatively, was changed to cefazolin (6 g/day), gentamicin (320 mg/day), and clindamycin (2700 mg/day) after surgery. On hospital day 6, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus was cultured from blood and wound specimens. Antibacterial therapy was tapered to intravenous cefazolin and continued for 6 weeks to treat osteomyelitis (Fig. 4). On postoperative day 10, residual necrotic tissue was debrided, and part of the wound edges was sutured together. After surgery, negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) and hyperbaric oxygen therapy were performed for infection control and wound healing. The patient’s general condition improved, and there was good granulation tissue formation. He was transferred to his hometown hospital, and the wound was closed using a V-Y flap on hospital day 48. The patient has been free of relapse for 3 years.

Fig. 3.

Wound-related findings. Operative findings on the day of admission (a, b) were necrotizing tissue around the sternoclavicular joint and the joint destruction (white arrow). When we debrided residual necrotizing tissue on postoperative day 10, the sternoclavicular joint was still exposed (black arrow) (c). We introduced negative pressure wound therapy on postoperative day 11 (d). On postoperative day 37, good granulation was observed (e)

Fig. 4.

Clinical course. WBC white blood cells, CRP C-reactive protein, BT body temperature, CEZ cefazolin, CLDM clindamycin, GM gentamicin, ABPC/SBT ampicillin/sulbactam, NPWT negative pressure wound therapy, HBO hyperbaric oxygen therapy

Discussion

Septic arthritis of the SCJ is rare, involving only 0.5–1.0 % of all joint infections. It occurs in less than 0.5 % of otherwise healthy adults [1–4]. It may cause serious complications such as osteomyelitis [5], chest wall abscess [6–8], mediastinitis [9], or myositis [4], with an increased risk of irreversible tissue damage and possibly death [4, 10].

Among 180 cases of SCJ septic arthritis, Ross et al. identified the following predisposing risk factors: intravenous drug use (21 %), distant site of infection (15 %), diabetes mellitus (13 %), trauma (12 %), and infected central venous line (9 %). No risk factor was found in 23 % of the patients [1]. The route of infection is often unknown, especially in otherwise healthy patients [3].

The clinical signs of SCJ septic arthritis are chest pain localizing to the SCJ (78 %), fever (65 %), and shoulder pain (24 %). SCJ septic arthritis infrequently presents with neck pain (2 %) [1, 2]. Therefore, septic arthritis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of chest and neck pain and fever.

CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be performed routinely in all cases of SCJ arthritis [1] to determine the severity of the infection and guide the surgical strategy [12–14]. CT and MRI can demonstrate joint subluxation, joint destruction, periarticular inflammation, and SCJ abscess.

The rate of positive cultures with needle aspiration is 77 %, compared with 36 % with surgical debridement and 13 % with blood culture [1]. S. aureus is responsible for 49 % of culture-positive infections, Pseudomonas aeruginosa for 10 %, Brucella melitensis for 7 %, and Escherichia coli for 5 %. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection occurs infrequently [1].

Management of SCJ septic arthritis consists of surgical debridement and intravenous antibiotics [3, 11]. Song et al. reported that complete SCJ resection and pectoralis flap closure resulted in no recurrences among patients with SCJ septic arthritis, while debridement and antibiotic therapy alone were associated with recurrence in five of six patients [12]. In our patient, because SCJ infection was limited to a small area, partial debridement was performed instead of complete resection. The cavity after debridement was relatively small, and NPWT was performed for wound granulation. After methicillin-susceptible S. aureus was identified in blood and wound cultures, broad-spectrum intravenous antimicrobial therapy was switched to intravenous cefazolin, which was continued for 6 weeks to treat osteomyelitis.

Conclusions

SCJ septic arthritis is a rare infection, especially in healthy adults. Because SCJ septic arthritis is associated with a risk of serious complications such as chest wall abscess, prompt diagnosis and appropriate surgical and antibacterial treatment are required.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- ABPC/SBT

ampicillin/sulbactam

- Alb

albumin

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- Amy

amylase

- aPTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- AT-III

antithrombin III

- BE

base excess

- BT

body temperature

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- Ca2+

calcium

- CEZ

cefazolin

- Cl−

chloride

- CLDM

clindamycin

- CPK

creatine phosphokinase

- Cre

creatinine

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CT

computed tomography

- D-Bil

direct bilirubin

- FDP

fibrin degradation products

- FiO2

fraction of inspired oxygen

- GM

gentamicin

- γ-GTP

γ-glutamyl transferase

- Hb

hemoglobin

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin A1c

- HBO

hyperbaric oxygen therapy

- Hct

hematocrit

- IP

inorganic phosphorus

- K+

potassium

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- Mg

magnesium

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- Na+

sodium

- NPWT

negative pressure wound therapy

- pCO2

partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- Plt

platelets

- pO2

partial pressure of oxygen

- PT

prothrombin time

- RBC

red blood cells

- SCJ

sternoclavicular joint

- T-Bil

total bilirubin

- T-Chol

total cholesterol

- TG

triglycerides

- TP

total protein

- WBC

white blood cells

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YT analyzed and interpreted the clinical data, wrote the case report, and revised the manuscript. HK, KS, YN, NY, HO, TY, IT, and SO supervised the case. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yoshihito Tanaka, Email: yoshihito910@gmail.com.

Hisaaki Kato, Email: hisaaki@gifu-u.ac.jp.

Kunihiro Shirai, Email: shu-chan@jf6.so-net.ne.jp.

Yasuhiro Nakajima, Email: runners-md@hotmail.co.jp.

Noriaki Yamada, Email: hokken@go2.enjoy.ne.jp.

Hideshi Okada, Email: hideshiokada@gmail.com.

Takahiro Yoshida, Email: taka_yomo_ayu@yahoo.co.jp.

Izumi Toyoda, Email: toyoda@gifu-u.ac.jp.

Shinji Ogura, Email: oguras@gifu-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Ross JJ, Shamsuddin H. Sternoclavicular septic arthritis: review of 180 cases. Medicine. 2004;83:139–48. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000126761.83417.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yood RA, Goldenberg DL. Sternoclavicular joint arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:232–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Natan M, Salai M, Sidi Y. Sternoclavicular infectious arthritis in previously healthy adults. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:189–95. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crisostomo RA, et al. Septic sternoclavicular joint: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:884–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tecce PM, Fishman EK. Spiral CT with multiplanar reconstruction in the diagnosis of sternoclavicular osteomyelitis. Skelet Radiol. 1995;24:275–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00198415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindhoudt DV, Velan F, Ott H. Abscess formation in sternoclavicular septic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:413–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wohlgethan JR, Newberg AH, Reed JI. The risk of abscess from sternoclavicular septic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1302–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuda T, Tamura K, Fujiwara M. Tuberculous arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint: a report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:136–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199501000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollack MS, et al. Staphylococcal mediastinitis due to sternoclavicular pyarthrosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990;14:924–7. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199011000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fordham S, et al. Optimal management of sternoclavicular septic arthritis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2009;228:275–8. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328311cdc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddad M, Maziak DE, Shamji FM. Spontaneous sternoclavicular joint infections. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:1225–7. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03815-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song HK, Guy TS, Kaiser LR, et al. Current presentation and optimal surgical management of sternoclavicular joint infections. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:427–31. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burkhart HM, Deschamps C, Allen MS, et al. Surgical management of sternoclavicular joint infections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:945–9. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nusselt T, Klinger HM, Freche S, Schultz W, Baums MH. Surgical management of sternoclavicular septic arthritis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:319–23. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1178-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]