Abstract

DNA polymerase ι (Polι) is a member of the Y family of DNA polymerases, which promote replication through DNA lesions. The role of Polι in lesion bypass, however, has remained unclear. Polι is highly unusual in that it incorporates nucleotides opposite different template bases with very different efficiencies and fidelities. Since interactions of DNA polymerases with the DNA minor groove provide for the nearly equivalent efficiencies and fidelities of nucleotide incorporation opposite each of the four template bases, we considered the possibility that Polι differs from other DNA polymerases in not being as sensitive to distortions of the minor groove at the site of the incipient base pair and that this enables it to incorporate nucleotides opposite highly distorting minor-groove DNA adducts. To check the validity of this idea, we examined whether Polι could incorporate nucleotides opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct, which is formed from an initial reaction of acrolein with the N2 of guanine. We show here that Polι incorporates a C opposite this adduct with nearly the same efficiency as it does opposite a nonadducted template G residue. The subsequent extension step, however, is performed by Polκ, which efficiently extends from the C incorporated opposite the adduct. Based upon these observations, we suggest that an important biological role of Polι and Polκ is to act sequentially to carry out the efficient and accurate bypass of highly distorting minor-groove DNA adducts of the purine bases.

Replicative DNA polymerases synthesize DNA with high fidelity, and because of their intolerance of geometric distortions in DNA, they are blocked by DNA lesions. The DNA polymerases belonging to the Y family, however, are low-fidelity enzymes, able to promote replication through DNA lesions. DNA polymerase η (Polη) from both the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and humans can efficiently and accurately replicate through a cis-syn thymine-thymine dimer (16, 19, 43, 45), and genetic studies in yeast and humans have also indicated a role for Polη in the error-free replication through cyclobutane dimers formed at 5′-TC-3′ and CC sites (39, 49). Consequently, mutational inactivation of Polη in humans causes the variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum (15, 28), characterized by a greatly enhanced predisposition for sunlight-induced skin cancers. Polη can also efficiently replicate through other DNA lesions, such as 8-oxoguanine and O6-methylguanine (11, 14). Polη, however, is inhibited by the N2-guanine adducts of 1,3-butadiene or benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide (30, 37).

In addition to Polη, humans contain two other Y-family DNA polymerases, Polι and Polκ. By contrast to Polη, which promotes lesion bypass both by efficiently inserting the nucleotide opposite the lesion and by extending from the inserted nucleotide, Polι and Polκ are apparently more specialized in their roles in lesion bypass (36). For example, while Polι can incorporate nucleotides opposite the 3′ T of a (6-4) TT photoproduct or opposite an abasic site, it is unable to carry out the subsequent extension reaction (18). A role for Polκ in the extension step has been suggested from its ability to proficiently extend from nucleotides opposite the 3′ T of a TT dimer or from nucleotides incorporated opposite an O6-methylguanine; Polκ, however, is very inefficient at incorporating nucleotides opposite both these DNA lesions (10, 42).

The evidence for the involvement of Polι and Polκ in lesion bypass, however, remains rather limited, and it is unlikely that they make a major contribution to the replicative bypass of the above-mentioned DNA lesions, where they have been implicated to have a role at the nucleotide incorporation or the extension step of lesion bypass. For example, opposite an abasic site, we expect the replicative polymerase, Polδ, to be much more effective at the nucleotide incorporation step than Polι (12), and at cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, Polη and not Polκ would be the major contributor to their bypass.

By contrast to most DNA polymerases, including Polη and Polκ, which exhibit nearly similar efficiencies and fidelities of nucleotide incorporation opposite each of the four template bases (17, 19, 44), Polι is unusual in that the efficiency and fidelity of nucleotide incorporation by this polymerase is dependent on the identity of the template base. Polι exhibits a higher efficiency of correct nucleotide incorporation opposite purine template bases than opposite pyrimidine templates (9, 18, 40). Opposite template A, Polι incorporates nucleotides with a high efficiency and fidelity, misincorporating nucleotides with frequencies of 10−4 to 10−5. Opposite template T, however, Polι incorporates nucleotides with a very low efficiency and fidelity, preferring to misincorporate a G opposite T ∼10 times more efficiently than it incorporates the correct nucleotide, A.

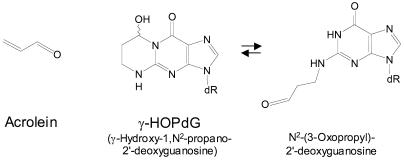

Extensive interactions with the DNA minor groove provide classical DNA polymerases with the ability to incorporate the correct nucleotide opposite different template bases with nearly similar efficiencies, and therefore, any distortion of the DNA minor groove is inhibitory to synthesis by these polymerases (see reference 47 for a discussion and references). Because of the preference of Polι for incorporating nucleotides opposite template purines, we reasoned that Polι might not be as sensitive to DNA minor-groove distortions at the site of the incipient base pair and that this could allow Polι to incorporate nucleotides opposite minor-groove DNA adducts. Since the minor-groove N2 group of guanine is highly reactive, able to conjugate with a variety of endogenously formed adducts, we sought an N2dG binding adduct that is a frequently formed product of inborn metabolism. Acrolein, an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde, is generated in vivo as the end product of lipid peroxidation and during metabolic oxidation of polyamines, and it is a ubiquitous environmental pollutant formed by the incomplete combustion of organic materials (3, 4, 26, 35). The reaction of acrolein with the N2 of dG followed by ring closure at N-1 leads to the formation of the cyclic adduct γ-hydroxy-1,N2-propano-2′deoxyguanosine (γ-HOPdG) (Fig. 1), and this adduct has been shown to be present in the DNAs of human and rodent tissues at comparatively high levels (2, 4, 32, 33). In the nucleoside and in single-stranded DNA, γ-HOPdG exists primarily in its ring-closed form (25, 34). However, nuclear magnetic resonance studies have shown that in duplex DNA, the exocyclic ring opens to form N2-(3-oxopropyl)-2′-deoxyguanosine when γ-HOPdG is paired with a C (Fig. 1). For this isomer, the adducted G participates in a normal Watson-Crick base pairing with C, and the N2-propyl chain stays in the minor groove pointing toward the solvent (5, 22, 24).

FIG. 1.

Structure of acrolein and its N2 deoxyguanosine adducts.

γ-HOPdG presents a strong block to synthesis by DNA polymerases (20). Although both yeast and human Polη can weakly replicate through the γ-HOPdG adduct, DNA synthesis is inhibited right before the lesion and also opposite from it, and steady-state kinetic analyses have indicated that the efficiency of C incorporation opposite γ-HOPdG with yeast and human Polη is ∼200 and 100-fold lower, respectively, than C incorporation opposite an undamaged G. The inhibition at the extension step was less severe, with incorporation being reduced ∼10- to 20-fold (29).

Here we have examined the ability of Polι and Polκ to replicate through the γ-HOPdG adduct. Using steady-state kinetics, we showed that Polι is highly efficient at incorporating a C opposite this lesion, and in fact, the efficiency of C incorporation opposite the adduct is nearly the same as that opposite the nondamaged G residue. Furthermore, we found that Polκ efficiently extends from a C paired with the γ-HOPdG adduct. From these observations, we conclude that Polι and Polk act sequentially to efficiently and accurately bypass the γ-HOPdG adduct, and we propose that an important biological function of Polι is to incorporate nucleotides opposite minor-groove DNA adducts of purines and that of Polκ is to carry out the subsequent extension reaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Substrates.

Nonadducted oligodeoxynucleotides were obtained from Midland Certified Reagent Co. (Midland, Tex.). Oligodeoxynucleotides containing a site-specific γ-HOPdG were synthesized as previously described (34) and have been extensively characterized (22-24). The −1 primer was a 21-mer oligodeoxynucleotide with the sequence 5′-AGCCC AAGCT TGGCG CGGAC T, and 0 primer-T and 0 primer-C were 21-mer oligodeoxynucleotides with the sequence 5′-GCCC AAGCT TGGCG CGGAC TN, where N is T or C, respectively. The template strands were 38-mer oligodeoxynucleotides with the sequence 5′-GCT AGCGA GTCCG CGCCA AGCTT GGGCT GCAGC AGGTC, where the underlined G is either a nondamaged G or a γ-HOPdG. Construction of template oligodeoxynucleotides was done according to the previously published procedure (20). The primer strands were 32P 5′-end labeled with polynucleotide kinase (Roche Diagnostic Corporation) and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Life Sciences). The 32P-, 5′-end-labeled primer strands (100 nM) were annealed to the template strands (100 nM) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 100 mM NaCl by heating to 90°C for 2 min and slowly cooling to room temperature over several hours. Solutions of dGTP, dATP, dTTP, and dCTP (0.1 M each) were purchased as the sodium salt, pH 8.3, from Roche and were stored at −80°C until use.

Purification of human Polι and Polκ.

GST-Polι and GST-Polκ were expressed in S. cerevisiae strain BJ5464 carrying either plasmid pPOL114 or pPOL42, respectively, as described previously (9, 13, 17, 18). These glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were purified as described before for Polη (41, 46). Briefly, the GST fusion proteins were bound to a glutathione 4B Sepharose matrix (Amersham Pharmacia), washed, and removed from the matrix by treatment with PreScission protease (Amersham Pharmacia), which removes the GST protein from the enzyme, leaving full-length Polι or Polκ fused to a seven-amino-acid N-terminal peptide.

DNA polymerase assays.

DNA polymerase activity was measured in the presence of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml. Either Polι, Polκ, or both Polι and Polκ (1 nM each) were incubated at 22°C with the DNA substrate (5 or 10 nM) and a 20 μM concentration of either dGTP, dATP, dTTP, dCTP, or all four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) for 30 min. Reactions were quenched by the addition of 10 volumes of formamide loading buffer, and the products were run on a 15% polyacrylamide sequencing gel containing 8 M urea.

Steady-state kinetics.

The efficiency of nucleotide incorporation (kcat/Km) was measured under the conditions described above, except that the concentration of the dNTP was varied from 0 to 500 μM and the incubation time ranged from 2 to 10 min. The components of the quenched reactions were analyzed by separating the unreacted substrates and the products by 15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and determining the gel band intensities with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The observed rate of nucleotide incorporation was graphed as a function of dNTP concentration, and the kcat and Km steady-state parameters were obtained from the best fit of the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation: vobs = kcat[E][dNTP]/(Km + [dNTP]), where [E] is enzyme concentration.

RESULTS

Replication through γ-HOPdG by the sequential action of Polι and Polκ.

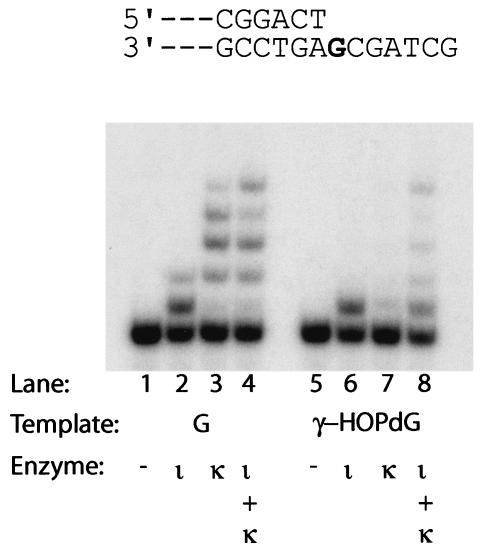

To examine the ability of Polι and Polκ to bypass γ-HOPdG, we incubated 1 nM Polι and 1 nM Polκ either individually or together with a 5 nM standing-start DNA substrate in which the 3′ terminus of the primer is located one nucleotide before the γ-HOPdG adduct (−1 primer), and 20 μM concentrations of each of the four dNTPs. Polι incorporates a nucleotide opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct nearly as well as opposite the nonadducted G (Fig. 2, compare lanes 2 and 6). By contrast, Polκ is very poor at incorporating a nucleotide opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct, and consequently, it is unable to replicate through this DNA adduct (Fig. 2, compare lanes 3 and 7). Replication through the γ-HOPdG adduct, however, occurred when both Polι and Polκ were combined (Fig. 2, compare lanes 4 and 8). These observations suggested that replication through the γ-HOPdG adduct can be achieved by the sequential action of Polι and Polκ, where Polι incorporates a nucleotide opposite the adduct and Polκ extends from this nucleotide.

FIG. 2.

Replicative bypass of the γ-HOPdG adduct by Polι and Polκ. DNA substrate (5 nM) with either a template G or γ-HOPdG was incubated with all four dNTPs (20 μM each) and 1 nM Polι (lanes 2 and 6), 1 nM Polκ (lanes 3 and 7), or both Polι and Polκ (lanes 4 and 8) for 30 min at 22°C. A bold G indicates the position of the undamaged G or γ-HOPdG adduct in the template.

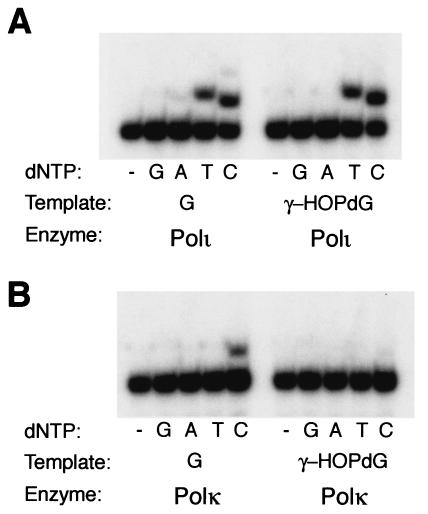

Nucleotide incorporated by Polι opposite γ-HOPdG.

To identify the nucleotide that is incorporated by Polι opposite γ-HOPdG, we performed single-nucleotide-incorporation experiments using the standing-start DNA substrate shown in Fig. 2. Polι (1 nM) was incubated with 10 nM of either the G or the γ-HOPdG DNA substrate in the presence of 20 μM of one of the four dNTPs. As shown in Fig. 3A, opposite both the nonadducted G and the γ-HOPdG adduct, Polι incorporates the T and C nucleotides. To verify the inability of Polκ to incorporate a nucleotide opposite γ-HOPdG, we examined whether Polκ could incorporate any of the four nucleotides under conditions similar to those used for Polι. However, by contrast to the incorporation of a C opposite the nonadducted G template, we observed no significant incorporation of any of the nucleotides opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct by Polκ (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide incorporation opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct by Polι and Polκ. DNA substrate (10 nM) with either a template G or γ-HOPdG was incubated with either 1 nM Polι (A) or Polκ (B) and the indicated dNTP substrate (20 μM) for 30 min at 22°C.

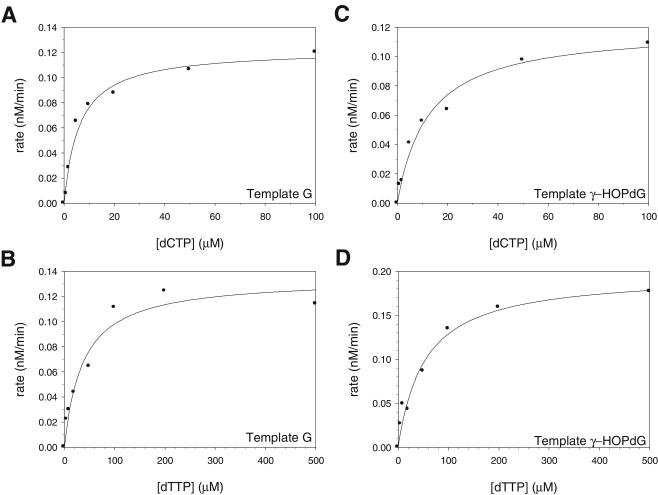

Steady-state kinetics of nucleotide incorporation opposite γ-HOPdG.

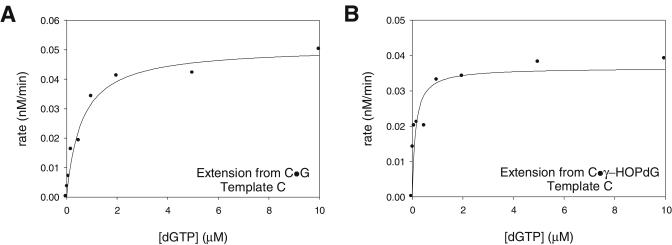

Next, we quantified the efficiency of nucleotide incorporation opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct by Polι using steady-state kinetics. Polι (1 nM) was incubated with a 10 nM concentration of the DNA substrate containing undamaged G or γ-HOPdG in the template and various concentrations of one of the four dNTPs. The rate of nucleotide incorporation was graphed as a function of nucleotide concentration, and the kcat and Km parameters were obtained from the best fit of these data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Fig. 4; Table 1). We detected no incorporation of dGTP or dATP opposite either template G or γ-HOPdG. Although Polι incorporates both dCTP and dTTP opposite template G, the incorporation of dCTP was about fivefold more efficient than that of dTTP (Fig. 4A and B; Table 1). Interestingly, the efficiency (kcat/Km) of dCTP incorporation opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct was only twofold lower than the efficiency of dCTP incorporation opposite the nonadducted G (Fig. 4A and C; Table 1). dTTP was also incorporated opposite γ-HOPdG, and the efficiencies of dTTP incorporation were the same opposite both the nonadducted and adducted template residues (Fig. 4B and D; Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Steady-state kinetics of nucleotide incorporation opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct by Polι. Steady-state rates of C incorporation opposite a template G (A), T incorporation opposite a template G (B), C incorporation opposite a template γ-HOPdG (C), and T incorporation opposite a template γ-HOPdG (D) were graphed as a function of dNTP concentration. The kcat and Km parameters were obtained from the best fit of the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation and are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for nucleotide incorporation by Polι opposite undamaged template G and γ-HOPdG

| Template | dNTP | kcat (min−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Kma | fincb | Relative efficiencyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | dGTP | NDd | ND | <2 × 10−4 | ||

| dATP | ND | ND | <2 × 10−4 | |||

| dTTP | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 37 ± 10 | 3.5 ± 10−3 | 0.18 | ||

| dCTP | 0.12 ± 0.006 | 6.1 ± 1.1 | 2 × 10−2 | 1.0 | ||

| γ-HOPdG | dGTP | ND | ND | <2 × 10−4 | ||

| dATP | ND | ND | <2 × 10−4 | |||

| dTTP | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 53 ± 10 | 3.8 × 10−3 | 0.38 | 0.2 | |

| dCTP | 0.12 ± 0.006 | 12 ± 2 | 1 × 10−2 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

When no incorporation was detected, kcat/Km was below the detection limit for the assay, which is 2 × 10−4 μM−1 min−1.

finc = (kcat/Km)incorrect/(kcat/Km)correct.

Efficiency of nucleotide incorporation opposite γ-HOPdG relative to the efficiency of C incorporation opposite undamaged G.

ND, no incorporation detected.

Steady-state kinetics of extension of the primer terminus opposite from γ-HOPdG by Polκ.

Using steady-state kinetics, we examined the efficiency of extension by Polκ from a C or a T nucleotide placed opposite the nonadducted G or the γ-HOPdG adduct. Polκ (1 nM) was incubated with a 10 nM concentration of a DNA substrate containing a primer terminal T · G, C · G, T · γ-HOPdG, or C · γ-HOPdG base pair with various concentrations of dGTP, the nucleotide complementary to the first available template residue (Table 2). Interestingly, the efficiency of extension from the C · γ-HOPdG primer terminal pair was about threefold higher than the efficiency of extending from the nonadducted C · G base-pair (Fig. 5; Table 2). By contrast to the efficient extension from a C opposite γ-HOPdG, we observed no significant extension from a T opposite γ-HOPdG (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Steady-state kinetic parameters of extension from primer termini paired with a G or γ-HOPdG by Polκ

| Base pair at primer terminusa | kcat (min−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Kmb | Relative efficiencyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T · G | NDd | ND | <2 × 10−3 | |

| C · G | 0.051 ± 0.0024 | 0.60 ± 0.10 | 0.084 | |

| T · γ-HOPdG | ND | ND | <2 × 10−3 | |

| C · γ-HOPdG | 0.037 ± 0.0024 | 0.13 ± 0.042 | 0.28 | 3.33 |

Primer terminal base pairs are given in the form primer·template; incorporation was measured by using the next correct nucleotide, dGTP.

When no incorporation was detected, kcat/Km was below the detection limit for the assay, which is 2 × 10−3 μM−1 min−1.

Efficiency of extension from a C·γ-HOPdG primer terminal base pair relative to the efficiency of extension from a C·G primer terminal base pair.

ND, no incorporation detected.

FIG. 5.

Steady-state kinetics of extension from the nucleotide opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct by Polκ. Steady-state rates of dGTP incorporation opposite a template C following a primer terminal C · G base pair (A) or a primer terminal C · γ-HOPdG base pair (B) were graphed as a function of dGTP concentration. The kcat and Km parameters were obtained from the best fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation and are listed in Table 2. In the C · G and C · γ-HOPdG primer terminal base pairs, a C is placed opposite the undamaged G or the γ-HOPdG adduct in the template, respectively.

DISCUSSION

We show here that Polι efficiently incorporates nucleotides opposite γ-HOPdG, a predominant adduct formed from the reaction of acrolein with the N2 of guanine in DNA. DNA synthesis by Polι is highly error prone and opposite undamaged G, Polι incorporates a T with an efficiency that is only about fivefold lower than that of C incorporation. Remarkably, opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct, Polι incorporates the C and T nucleotides with nearly the same efficiency and fidelity as opposite the undamaged G template. Polι, however, is unable to carry out the subsequent extension reaction. Polκ, on the other hand, does not incorporate nucleotides opposite γ-HOPdG but can perform the extension reaction. Interestingly, Polκ extends from the C opposite γ-HOPdG about threefold more efficiently than the extension from C opposite undamaged G. Polκ, however, is highly inefficient at extending from a T inserted opposite γ-HOPdG by Polι. These observations suggest that efficient and error-free bypass of the γ-HOPdG adduct could occur by the sequential action of Polι and Polκ, in which following a C incorporation by Polι, Polκ performs the subsequent extension step. Even though Polι misincorporates a T opposite this adduct fairly frequently, since Polκ does not catalyze the extension from this nucleotide, the resultant mispaired primer terminus would be accessible to removal by proofreading exonucleases.

In experiments in which γ-HOPdG was site-specifically incorporated into a simian virus 40 origin-based double-stranded vector, in both HeLa cells and XP-V cells, this adduct was found to be only marginally miscoding (≤1% base substitutions) (48). With a single-stranded shuttle vector, the incidence of base substitutions was only slightly higher in XP-V cells than in normal human cells (29). These observations indicated that synthesis across γ-HOPdG is quite accurate in human cells and that Polη plays a minor, if any, role in γ-HOPdG bypass. This conclusion is in accord with the biochemical studies indicating that γ-HOPdG is a block to human Polη at both the nucleotide incorporation and extension steps and that it is more apt to misincorporate nucleotides opposite γ-HOPdG than opposite an undamaged G (29). Based upon the findings presented here, we suggest that error-free replication through the γ-HOPdG adduct in human cells could be achieved by the sequential action of Polι and Polκ.

An important feature shared by DNA polymerases is that they interact with their DNA substrates principally through the DNA minor groove. Hydrogen bonding interactions between specific Arg, His, Asn, Gln, and Lys hydrogen bonding donors in the protein and the N3 hydrogen bonding acceptor of purine bases and the O2 hydrogen bonding acceptor of pyrimidine bases in the DNA minor groove are observed in X-ray crystal structures of various DNA polymerases—bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase (6), Bacillus stearothermophilus DNA polymerase I (21), Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I (27), and bacteriophage RB69 DNA polymerase (8). In addition, the importance of these polymerase-DNA minor-groove interactions has been shown in studies using DNA base analogs lacking the N3 or O2 minor-groove hydrogen-bonding acceptors (31, 38). Presumably the disruption of these functionally important interactions by steric clashes with template minor-groove DNA lesions is responsible for the inability of classical DNA polymerases to incorporate nucleotides opposite such lesions. The proficient ability of Polι to incorporate nucleotides opposite γ-HOPdG suggests that this polymerase is refractory to distortions conferred upon the DNA minor groove by this adduct and that this may arise because Polι does not functionally interact with the DNA minor groove of the incipient base pair. The inability of Polι to extend from the nucleotide incorporated from opposite γ-HOPdG suggests, however, that this polymerase is sensitive to distortions conferred by this adduct at the primer terminus. Polκ, on the other hand, is inhibited at incorporating a nucleotide opposite the γ-HOPdG adduct but is proficient at extending the C · γ-HOPdG primer terminus. Polι and Polκ thus differ remarkably in their response to this minor-groove DNA adduct.

Because of the high reactivity of the N2 group of guanine, a variety of DNA adducts would form at this minor-groove position, which include the propano adducts and malondialdehyde-derived adducts. The propano adducts are formed from α,β-unsaturated aldehydes or enals, such as acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (3, 4). Lipid peroxidation, which becomes quite significant when cells are under oxidative stress, exposed to xenobiotics, or subjected to bacterial and viral infections, produces enals of various chain lengths ranging from acrolein to trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal as secondary products, as well as malondialdehyde (1, 7). These adducts are present in the DNAs of human and rodent tissues at relatively high levels (2, 4, 32, 33). Our finding that Polι is not inhibited when γ-HOPdG is the templating residue in the incipient base pair and that Polκ is not inhibited when γ-HOPdG is present in the template strand at the primer terminus leads us to propose that one major role of Polι and Polκ is to act sequentially at the nucleotide incorporation and extension steps, respectively, in the bypass of a wide range of minor-groove adducts of guanine.

DNA polymerases incorporate nucleotides opposite each of the four template bases with nearly equivalent efficiencies and fidelities, Polι being an exception to this rule. Since polymerase interactions with the DNA minor groove provide for the nearly equivalent efficiencies of nucleotide incorporation opposite different template bases, the presumed inability of Polι to functionally interact with the DNA minor groove of the incipient base pair might account for the unusual nucleotide incorporation specificities of this enzyme. Thus, we suggest that while the active site of Polι has become specialized for incorporating nucleotides opposite the highly distorting minor-groove adducts of purine bases, such as γ-HOPdG, one consequence of this is that Polι has lost the ability to efficiently and accurately incorporate nucleotides opposite pyrimidine bases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grants ES012411 (L.P.) and ES05355 (Michael Stone, PI).

We acknowledge Pam Tamura and Albena Kozekova (Department of Chemistry, Center in Molecular Toxicology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.) for synthesis of γ-HOPdG-adducted oligodeoxynucleotide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames, B. N., and L. S. Gold. 1991. Endogenous mutagens and the causes of aging and cancer. Mutat. Res. 250:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung, F.-L., H.-J. C. Chen, and R. G. Nath. 1996. Lipid peroxidation as a potential endogenous source for the formation of exocyclic DNA adducts. Carcinogenesis 17:2105-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung, F.-L., R. G. Nath, M. Nagao, A. Nishikawa, G.-D. Zhou, and K. Randerath. 1999. Endogenous formation and significance of 1,N2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts. Mutat. Res. 424:71-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung, F.-L., L. Zhang, J. E. Ocando, and R. G. Nath. 1999. Role of 1,N2-propanodeoxygunosine adducts as endogenous DNA lesions in rodents and humans. IARC Sci. Publ. 150:45-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de los Santos, C., T. Zaliznyak, and F. Johnson. 2001. NMR characterization of a DNA duplex containing the major acrolein-derived deoxyguanosine adduct γ-OH-1,-N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9077-9082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doublie, S., S. Tabor, A. M. Long, C. C. Richardson, and T. Ellenberger. 1998. Crystal structure of a bacteriophage T7 DNA replication complex at 2.2 A resolution. Nature 391:251-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esterbauer, H., R. J. Schaur, and H. Zollner. 1991. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 11:81-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franklin, M. C., J. Wang, and T. A. Steitz. 2001. Structure of the replicating complex of a Pol α family DNA polymerase. Cell 105:657-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haracska, L., R. E. Johnson, I. Unk, B. B. Phillips, J. Hurwitz, L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2001. Targeting of human DNA polymerase ι to the replication machinery via interaction with PCNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14256-14261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haracska, L., L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2002. Role of human DNA polymerase κ as an extender in translesion synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16000-16005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haracska, L., S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Replication past O6-methylguanine by yeast and human DNA polymerase η. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8001-8007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haracska, L., I. Unk, R. E. Johnson, E. Johansson, P. M. J. Burgers, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2001. Roles of yeast DNA polymerases δ and ζ and of Rev1 in the bypass of abasic sites. Genes Dev. 15:945-954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haracska, L., I. Unk, R. E. Johnson, B. B. Phillips, J. Hurwitz, L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2002. Stimulation of DNA synthesis activity of human DNA polymerase κ by PCNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:784-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haracska, L., S.-L. Yu, R. E. Johnson, L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2000. Efficient and accurate replication in the presence of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine by DNA polymerase η. Nat. Genet. 25:458-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, R. E., C. M. Kondratick, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. hRAD30 mutations in the variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum. Science 285:263-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson, R. E., S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. Efficient bypass of a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase, Polη. Science 283:1001-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, R. E., S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. The human DINB1 gene encodes the DNA polymerase Polθ○. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3838-3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, R. E., M. T. Washington, L. Haracska, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Eukaryotic polymerases ι and ζ act sequentially to bypass DNA lesions. Nature 406:1015-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson, R. E., M. T. Washington, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Fidelity of human DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 275:7447-7450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanuri, M., I. G. Minko, L. V. Nechev, T. M. Harris, C. M. Harris, and R. S. Lloyd. 2002. Error prone translesion synthesis past γ-hydroypropanodeoxyguanosine, the primary acrolein-derived adduct in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18257-18265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiefer, J. R., C. Mao, J. C. Braman, and L. S. Beese. 1998. Visualizing DNA replication in a catalytically active Bacillus DNA polymerase crystal. Nature 391:304-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, H.-Y. H., M. Voehler, T. M. Harris, and M. P. Stone. 2002. Detection of an interchain carbinolamine cross-link formed in a CpG sequence by the acrolein DNA adduct γ-OH-1,N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:9324-9325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozekov, I. D., L. D. Nechev, A. Sanchez, C. M. Harris, R. S. Lloyd, and T. M. Harris. 2001. Interchain cross-linking of DNA mediated by the principal adduct of acrolein. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14:1482-1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozekov, I. D., L. V. Nechev, M. S. Moseley, C. M. Harris, C. J. Rizzo, M. P. Stone, and T. M. Harris. 2003. DNA interchain cross-links formed by acrolein and crotonaldehyde. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:50-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtz, A. J., and R. S. Lloyd. 2003. 1,N2-deoxyguanosine adducts of acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and trans-4-hydroxynonenal cross-link to peptides via Schiff base linkage. J. Biol. Chem. 278:5970-5976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, Y., and L. M. Sayre. 1998. Reaffirmation that metabolism of polyamines by bovine plasma amine oxidase occurs strictly at the primary amino termini. J. Biol. Chem. 273:19490-19494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Y., S. Korolev, and G. Waksman. 1998. Crystal structures of open and closed forms of binary and ternary complexes of the large fragment of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I: structural basis for nucleotide incorporation. EMBO J. 17:7514-7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masutani, C., R. Kusumoto, A. Yamada, N. Dohmae, M. Yokoi, M. Yuasa, M. Araki, S. Iwai, K. Takio, and F. Hanaoka. 1999. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η. Nature 399:700-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minko, I. G., M. T. Washington, M. Kanuri, L. Prakash, S. Prakash, and R. S. Lloyd. 2003. Translesion synthesis past acrolein-derived DNA adduct, γ-hydroxypropanodeoxyguanosine, by yeast and human DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 278:784-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minko, I. G., M. T. Washington, L. Prakash, S. Prakash, and R. S. Lloyd. 2001. Translesion DNA synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase η on templates containing N2-guanine adducts of 1,3-butadiene metabolites. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2517-2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morales, J. C., and E. T. Kool. 2000. A functional hydrogen-bonding map of the minor groove binding tracks of six DNA polymerases. Biochemistry 39:12979-12988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nath, R. G., and F.-L. Chung. 1994. Detection of exocyclic 1,N2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts as common DNA lesions in rodents and humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7491-7495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nath, R. G., J. E. Ocando, and F.-L. Chung. 1996. Detection of 1,N2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts as potential endogenous DNA lesions in rodent and human tissues. Cancer Res. 56:452-456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nechev, L. V., C. M. Harris, and T. M. Harris. 2000. Synthesis of nucleosides and oligonucleotides containing adducts of acrolein and vinyl chloride. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 13:421-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan, J., and F.-L. Chung. 2002. Formation of cyclic deoxyguanosine adducts from ω-3 and ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids under oxidative conditions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 15:367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prakash, S., and L. Prakash. 2002. Translesion DNA synthesis in eukaryotes: a one- or two-polymerase affair. Genes Dev. 16:1872-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rechkoblit, O., Y. Zhang, D. Guo, Z. Wang, S. Amin, J. Krzeminsky, N. Louneva, and N. E. Geacintov. 2002. Trans-lesion synthesis past bulky benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide N. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30488-30494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spratt, T. E. 2001. Identification of hydrogen bonds between Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) and the minor groove of DNA by amino acid substitution of the polymerase and atomic substitution of the DNA. Biochemistry 40:2647-2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stary, A., P. Kannouche, A. R. Lehmann, and A. Sarasin. 2003. Role of DNA polymerase η in the UV mutation spectrum in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:18767-18775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tissier, A., J. P. McDonald, E. G. Frank, and R. Woodgate. 2000. Polι, a remarkably error-prone human DNA polymerase. Genes Dev. 14:1642-1650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trincao, J., R. E. Johnson, C. R. Escalante, S. Prakash, L. Prakash, and A. K. Aggarwal. 2001. Structure of the catalytic core of S. cerevisiae DNA polymerase η: implications for translesion DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 8:417-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Washington, M. T., R. E. Johnson, L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2002. Human DINB1-encoded DNA polymerase κ is a promiscuous extender of mispaired primer termini. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1910-1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Washington, M. T., R. E. Johnson, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Accuracy of thymine-thymine dimer bypass by Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3094-3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Washington, M. T., R. E. Johnson, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 1999. Fidelity and processivity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 274:36835-36838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Washington, M. T., L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2003. Mechanism of nucleotide incorporation opposite a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase η. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:12093-12098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Washington, M. T., L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2001. Yeast DNA polymerase η utilizes an induced fit mechanism of nucleotide incorporation. Cell 107:917-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Washington, M. T., W. T. Wolfle, T. E. Spratt, L. Prakash, and S. Prakash. 2003. Yeast DNA polymerase η makes functional contacts with the DNA minor groove only at the incoming nucleoside triphosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:5113-5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang, I.-Y., F. Johnson, A. P. Grollman, and M. Moriya. 2002. Genotoxic mechanism for the major acrolein-derived deoxyguanosine adduct in human cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 15:160-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu, S.-L., R. E. Johnson, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2001. Requirement of DNA polymerase η for error-free bypass of UV-induced CC and TC photoproducts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:185-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]