Abstract

The growth hormone (GH) and its downstream mediator, the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), construct a pleotropic axis affecting growth, metabolism, and organ function. Serum levels of GH/IGF-1 rise during pubertal growth and associate with peak bone acquisition, while during aging their levels decline and associate with bone loss. The GH/IGF-1 axis was extensively studied in numerous biological systems including rodent models and cell cultures. Both hormones act in an endocrine and autocrine/paracrine fashion and understanding their distinct and overlapping contributions to skeletal acquisition is still a matter of debate. GH and IGF-1 exert their effects on osteogenic cells via binding to their cognate receptor, leading to activation of an array of genes that mediate cellular differentiation and function. Both hormones interact with other skeletal regulators, such as sex-steroids, thyroid hormone, and parathyroid hormone, to facilitate skeletal growth and metabolism. In this review we summarized several rodent models of the GH/IGF-1 axis and described key experiments that shed new light on the regulation of skeletal growth by the GH/IGF-1 axis.

Keywords: Growth hormone (GH) Growth hormone receptor (GHR), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), growth plate, periosteum, endosteum, perichondrium, chondrocyte, osteocyte, osteoblast, mineralization, micro-CT, histomorphometry, mechanical stimuli

Introduction

The skeleton is a rigid connective tissue that except for providing protection and support for the body also functions as an endocrine organ and interacts with other internal organs via secretion of hormones and micronutrients. Both long and flat bones of the skeleton are vital tissues containing osteocytes, the bone resident cells, and osteoblasts, the bone matrix-lining cells. During life, bones undergo processes of modeling (shaping) and remodeling (damage correcting), mediated by osteoblasts and osteoclasts, the bone resorbing cells. Bones are composed of two major compartments: the cortical bone, which is a compact dense structure of mineralized collagen; and the trabecular compartment, which is spongy, less compact, and is irregular in structure. Cortical bone has two surfaces: the periosteum, which is a fibrous layer with osteogenic potential allowing radial bone growth (also called periosteal bone apposition); and the endosteum, which borders with the marrow. Longitudinal bone growth occurs at the growth plates via endochondral ossification where pre-chondrocytes/resting cells first differentiate, proliferate, undergo hypertrophy, and subsequently mineralize. Both the periosteum and the endosteum layers contain blood vessels and nerve fibers connecting them to other organs in the body.

Bone metabolism refers to the complex functions of the skeleton in maintaining whole body homeostasis. Bone acts as a calcium and phosphate reservoir and responds to hormonal stimuli to release or deposit minerals according to systemic needs. Releasing of alkaline salts from bone buffers the blood, and absorbing/depositing heavy metals and other extraneous elements assists in whole body detoxification. Bone matrix functions as a repository for cytokines and growth factors that are released upon bone resorption and act locally in their microenvironment. Lastly, bone acts as an endocrine organ releasing fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23), a peptide regulating phosphate metabolism; osteocalcin, a hormone contributing to glucose/lipid metabolism; and sclerostin, a hormone regulating bone formation whose functions in other organs are yet to be discovered. There are several hormones/growth factors that regulate bone metabolism. These include the 1) parathyroid hormone (PTH), which regulates calcium and phosphate metabolism via its receptors (PTH1Rs) found on osteoblasts, osteocytes, cells of the intestine, and the kidney; 2) calcitonin, a peptide secreted from the thyroid and neuroendocrine cells that inhibits bone resorption; and 3) vitamin D, a secosterol hormone, which promotes calcium absorption by the intestine and decreases calcium and phosphorus excretion by the kidney. During development, linear and radial bone growth and modeling are regulated mainly by the growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis and sex steroids, which also protect the skeleton from age-related bone loss.

Summary of the literature about the GH/IGF-1 axis is overwhelming. The effects of these two hormones on cellular proliferation, differentiation and function have been tested in almost all cell systems and in numerous animal models. Thus, we have reviewed herein only a limited number of papers. We focused on regulation of skeletal growth by the GH/IGF-1 axis in mouse models, and emphasized specifically in vivo findings obtained from wild-type, global gene ablation, as well as data from cell-specific inactivation of GH/IGF-1 and members of its axis in mice.

The GH/IGF-1 axis

The GH/IGF-1 is an anabolic, pleotropic axis that includes several members; The GH releasing hormone (GHRH) that regulates GH secretion, GH, the GH receptor (GHR), IGF-1, and the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R). Downstream mediators of the GHR, such as the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 5 (STAT5), Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), and the suppressors of cytokine signaling 1–3 (SOCS1–3) are often included in that axis. Incorporated also are the IGF-binding proteins (IGFBPs) and the acid labile subunit (ALS) that carry IGF-1 in circulation, prolong its half-life, and regulate its bioavailability.

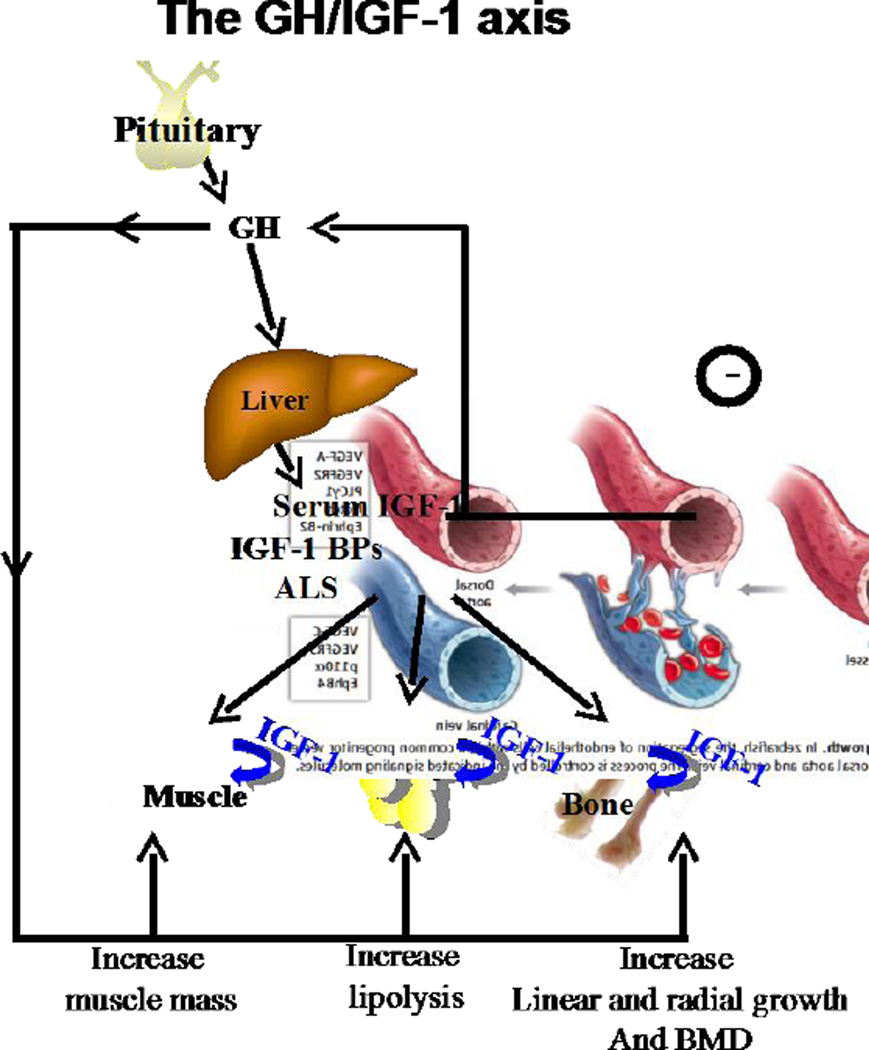

The synthesis and secretion of GH from the pituitary is promoted by GHRH, while inhibition of GH secretion is regulated largely by somatostatin, but also by other central and peripheral signals (1). Pituitary GH is the prime regulator of IGF-1 production in the liver (Figure 1). The liver is the major contributor to the circulating pool of IGF-1 (75%) while other tissues such as fat and muscle contribute ∼25% of IGF-1 in serum. In the circulation IGF-1 is bound to the IGFBPs and the ALS, which prolong IGF-1 half-life in serum and tissues and determine its bioavailability. IGFBP-3, the most abundant IGFBP in serum, and the IGFBP-5, form ternary complexes with IGF-1 and the ALS which have a half-lives of ∼16 hours. Binary complexes of IGFBPs and IGF-1 have half-lives of ∼90 minutes, while the half-life of free IGF-1 in serum is only ∼10 minutes. IGF-1 in serum acts in an endocrine fashion and provides negative feedback at the pituitary level to inhibit GH secretion. Importantly, IGF-1, which is produced by virtually all tissues, also acts in an autocrine/paracrine fashion at different local sites of production. IGF-1 binds to its tyrosine-kinase receptor, namely the IGF-1R. Upon binding to its receptor IGF-1 activates receptor autophosphorylation and recruitment of adaptor proteins, such as insulin receptor substrate (IRS) family, and the proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase Src, to activate cellular proliferation, differentiation, and organ function. GH effects on the liver, as well as on other organs, such as muscle, fat, cartilage, and bone, are mediated via the GHR, a cytokine-like receptor found in almost all tissues and which acts in an IGF-dependent or independent manner. Upon GH binding to the GHR, there is a conformational change in the intracellular domain of the receptor (2, 3), concomitant phosphorylation of the JAK2 proteins, and transduction of the signal to the STAT5 proteins that activate gene transcription (among them is igf-1). Suppression of this signaling cascade occurs through proteosomal degradation of the receptor, dephosphorylation of the JAK2 proteins (4), and their promotion to proteosomal degradation (5) by the SOCS proteins.

Figure 1. The GH/IGF-1 axis.

GH, secreted from the pituitary, is the prime regulator of igf-1 gene in liver, which contributes ∼75% ofserum IGF-1. GH act via its receptor that is found on almost all cells and increase muscle mass, fat lipolysis, linear and radial bone growth, and bone mineralization. IGF-1 in serum is bound to the IGF-BPs and the ALS, which regulate its half-life and deliver it to the tissues leading also to increased muscle mass, and bone mineral content. Serum IGF-1 serves also as a negative regulator of GH secretion from the pituitary. IGF-1 is produced by all tissues and acts in an autocrine/paracrine manner.

The feedback regulation between serum IGF-1 levels and pituitary GH secretion, as well as the diverse activities of both GH and IGF-1 in multiple tissues, affecting not only body size but also body composition and metabolism, posed many challenges in understanding the relative contribution of each hormone to skeletal growth. Furthermore, based on experimental evidence showing that GH stimulates igf-1 gene expression not only in liver but also in several other tissues, IGF-1 has long been regarded as the mediator of GH effects. However, as will be noted in this review, GH has both IGF-1-dependent and independent effects. Lastly, we mention that interpretation of data on skeletal growth from mouse models of the GH/IGF axis has to be done carefully, taking into account the complex interactions between these two hormones and their pleotropic effects on whole body homeostasis including bone.

Global impairment of the GH/IGF-1 axis affects body size and skeletal acquisition

Excess of GH

The GH/IGF-1 is an anabolic axis and as such, it is expected that models of excess GH/IGF-1 would lead to growth enhancement. Indeed, several models of overexpression of GHRH (6, 7), the human (h) (8–14) or bovine (b) GH in mice have demonstrated increased body size and skeletal gigantism (10, 15–21). In this review we will focus on the skeletal phenotype of models overexpressing bGH, which activates the endogenous mouse GHR, as opposed to the hGH transgene, which activates both the GHR and the prolactin receptor. All studies of transgenic mice with excess endogenous or transgenic bGH reported increases in bone size (length and diameter) and overall increases in bone mineral density (BMD). However, detailed analyses of skeletal properties revealed that systemic GH overexpression resulted in sex-specific and age-specific effects on the skeleton and impaired bone architecture and mechanical properties (15, 17, 19, 21). Overexpression of the hGHRH (20) resulted in systemic stimulation of endogenous GH and IGF-1 leading to initial increase in bone mass. However, later on, excess GH levels in that model were associated with increases in bone resorption, thinning of the bone cortexes, and the compromise of mechanical properties. Studies with mice overexpressing the bGH under the global metallothionein (MMT-1) promoter (MMT-1-bGH mice) have shown increases in cortical bone cross-sectional area with thinner cortexes, effects that were more profound in male mice (17, 19, 21). With respect to the trabecular bone compartment most studies showed increases in trabecular bone volume predominantly in females (17, 19, 21), while a recent study indicates reductions in trabecular bone in male mice (15). With respect to increased/excess GH activity we should note that the SOCS2 null mice, which exhibit aberrant GH signaling due to lack of feedback inhibition, are larger than controls despite normal levels of circulating IGF-1 (22). These mice show increased linear and radial bone growth, increased trabecular bone volume, as well as increased height of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the growth plate (23). Inhibition of GH excess in the SOCS2 null mice, by means of crossing them with the lit/lit mice (which have no GH production), normalized growth (24). Overall, the studies mentioned above, together with in vitro studies (that were not discussed herein), show that excess in GH activity increased linear and radial bone growth in the growing mice but was also associated with increased bone resorption during adulthood.

Excess of IGF-1

Overexpression of the GH mediator, IGF-1, under the same MMT-1 promoter (MTT-1-hIGF-1 mice) also showed enhanced body size, albeit to a lesser extent than bGH transgenic mice (25). The authors reported ∼50% increases in serum IGF-1 levels and suppressed endogenous GH secretion, as well as selective organomegaly in tissues sensitive to IGF-1 (spleen, pancreas, brain). With respect to skeletal growth, detailed analysis was not done at the time. However, radiographs of the tibia and radius revealed no differences in length between controls and the MTT-1-hIGF-1 mice (26). Parallel comparison between the MTT-1-bGH and the MTT-1-hIGF-1 showed that while GH stimulated ∼2fold increases in body size starting at ∼3 weeks of age, the IGF-1 transgene enhanced growth only by ∼30% that was apparent at 6–8 weeks of age. Together, data from MTT-1-bGH and the MTT-1-hIGF-1 mice suggest that GH has IGF-1-independent effects on somatic and skeletal growth. However, despite the valuable information deduced from these early experiments, we should keep in mind that the copy number of the bGH or the hIGF-1 transgenes inserted into the mouse genome, as well as the insertion sites, were not controlled and may have influenced the outcomes.

Global inactivation of the GHR

Mouse models of GH/IGF-1 deficiency, on the other hand, exhibit a dwarf phenotype and reduced skeletal acquisition. A mutation in the mouse GHRH gene (lit/lit) (24, 27–29), ablation of somatotropes (GH secreting cells) (30), or gene ablation of the GHR (31) (32) result in mice that are born with normal body weight. However, these animal models show growth retardation early post-natally, and reach ∼50–60% of normal adult body size. Likewise, transgenic mice overexpressing a GH antagonist (33) which causes blunted activation of the GHR, exhibit ∼45% reductions in body size. GH deficiency, as seen in the lit/lit mice, leads to significant decreases in BMD and reduced periosteal circumference (27). Similarly, the GHR null mice show severe retardation in longitudinal growth, reductions in trabecular bone volume, and reductions in all cortical bone traits (total cross-sectional area, bone area, cortical bone thickness, and periosteal/endosteal circumference) (31) (32). Reduced longitudinal growth in the GHR null mice were associated with premature growth plate contraction and reduced chondrocyte proliferation. Likewise, bone turnover in the GHR null mice was severely reduced and periosteal bone apposition prematurely ceased. Ablation of the GHR mediator, STAT5ab in mice (32) (34), associated with a 50% decrease in serum IGF-1 and ∼10% decreases in bone length in adult mice. Reduced linear growth in the STAT5ab null mice appeared to relate to developmental defects, since abnormalities in the growth plate were seen early at 2 weeks of age but not thereafter. Both GHR and the STAT5ab null mice showed decreased cortical bone area and width. However, unlike the GHR null, STAT5ab null mice exhibited normal periosteal bone apposition, suggesting that some of the GH effects are STAT5ab-independent (32). Gene ablation of the GHR mediator, JAK2, in mice (35, 36) was embryonically lethal (E12.5) and the skeletal phenotype was not reported.

Global inactivation of the IGF-1R

Inactivations of IGF-1 and IGF-1R in mice in the early 1990s (37–40) have advanced our understanding of the GH/IGF-1 axis and later allowed the unraveling of the distinct contribution of each hormone to body size, body composition, and metabolism. IGF-1R null mice are born 45% of normal size and exhibit severe growth retardation (41). These mice die after birth and show organ hypoplasia and delayed ossification. IGF-1R haploinsufficient mice (IGF-1R+/−) show reductions in serum IGF-1 levels, which correlate with reductions in body weight. These (IGF-1R+/−) mice present significant decreases in IGF-1 gene expression in the liver, bone, testicles, and brain, while GHR gene expression significantly increased in the liver, but markedly reduced in bone, and associated with significant reductions in cortical bone thickness (42). The use of the cre/loxP strategy in mouse genetics advanced our capabilities of genetic manipulations in mice (43). Generation of the IGF-1Rlox mice (44) opened a new era in our understanding of the GH/IGF-1 axis in bone (findings that will be described below). IGF-1Rnull mice generated using the cre/loxP system (using the EIIa-derived Cre) (44) have confirmed previous findings (41) and produced severely growth-retarded mice that died soon after birth. This model was further used to generate mosaic-early embryonic ubiquitous (meu) IGF-1R gene deletion producing a gradient of whole body IGF-1R gene deletion (45). This study showed that the cre-lox/P mediated dosage of the floxed IGF-1R gene correlated with overall body size, such that fewer receptors resulted in more severe growth retardation. Unfortunately, detailed bone analyses were not done on that model.

Global inactivation of the IGF-1

Ablation of IGF-1 in mice caused severe growth retardation reaching ∼30% of normal adult size (if these mice survived, depending on the genetic background) (39, 41). Assessment of embryonic skeletal development revealed that IGF-1 null mice exhibited markedly reduced chondrocyte proliferation, increased chondrocyte apoptosis, and abnormal chondrocyte differentiation leading to severe decreases in linear bone growth in the appendicular skeleton and significant reductions in BMD in the spinal column (46). Further characterization of adult IGF-1 null mice on the CD-1 genetic background (47) showed ∼26–30% reductions in bone size and ∼27% reductions in bone formation rates. Surprisingly, trabecular bone volume increased and periosteal bone formation and mineral apposition rates were normal (when adjusted to bone size). Double mutant mice of the IGF-1/IGF-1R resulted in a developmental phenotype that was similar to the IGF-1R null mice (41), suggesting that IGF-1R mediates all the effects of IGF-1. Lastly, the IGF-1 null mice remained responsive to GH and showed increases in bone formation rates when treated with exogenous GH, suggesting that GH has IGF-1-independent effects on the skeleton.

Studies of the IGF-1 haploinsufficient mice (IGF-1+/−) showed that moderate reductions in serum and tissue IGF-1 levels correlate with reductions in body weight, bone length, bone geometrical parameters (total cross-sectional area and cortical bone area), and BMD (48, 49). Another mouse model with global reductions in IGF-1 levels is the IGF-1 MIDI mouse (with an insertion of a targeting construct that led to low levels of IGF-1 expression). The IGF-1 MIDI mice are growth retarded and reach intermediate size between wild type and IGF-1 null mice. These mice, like the IGF-1+/− mice, show reductions in bone length and BMD (50).

Global inactivation of IGF-2

Ablation of IGF-2 in mice led to intrauterine growth retardation (51). The fetuses showed decreased body weight towards the end of gestation (96% and 78% of wild type at E16 and E19, respectively). At birth, however, IGF-2 null pups were 69% of normal birth weight, but a post-natal ‘catch-up’ growth was completed by three months of age. Comparison of body weight and bone length between the GH deficient mice (lit/lit) and the IGF-1 null or the IGF-2 null mice (28) revealed that IGF-2 regulates prenatal growth, while IGF-1 plays significant roles during postnatal stages, where pubertal and post pubertal growth phases are GH-dependent, effects that are IGF-1 dependent or independent. Additionally, IGF-1 null mice exhibit a more severe skeletal phenotype than that of the GH deficient (lit/lit) mice, suggesting that pubertal increases in BMD are largely GH-IGF-1-dependent effects. Generation of a double knockout mouse of both GHR and IGF-1 (52), resulted in a mouse that was smaller than each knockout alone and reached ∼10–15% of adult body size. This study has clearly shown that there are distinct and overlapping effects of GH and IGF-1 on body size, growth, and development.

Generation of the aforementioned global gene inactivated mouse models (table 1) significantly advanced our understanding of the GH/IGF-1 axis in skeletal growth. However, we should remember that using this approach, all tissues are affected, including the skeleton. We now know that interactions between the skeleton and other organs play significant roles in bone homeostasis and thus more sophisticated approaches had to be developed (as described below) to dissect tissue specific effects of the GH/IGF-1 on skeletal growth.

Table 1.

Global impairment of the GH/IGF-1 axis in mice.

| Mouse model | GH/IGF-1 status | Body size | Skeletal phenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GH excess | MTT-1- hGHRH (Tg) (6, 7, 20) |

Elevations in serum GH and serum and tissue IGF-1 |

∼25% increase in body size | Increased longitudinal and radial bone growth, increased bone resorption, and decreased mechanical properties. |

| PEPCK-bGH (Tg) (18, 158, 159) |

Elevations in serum and tissue GH/IGF-1 |

∼50% increase in body size | The femora and vertebrae of the transgenic animals showed obvious differences in size, shape, and trabecular arrangement compared with the control animals. Total bone mass increased by 2–3 fold. The PEPCK-bGH mice showed elevated trabecular bone volume fraction. Cortical bone thickness was lower in the transgenic animals. |

|

| MTT-1-bGH (Tg) (10–17, 19, 21) |

∼30–50% increase in body size | Increased bone length, decreased trabecular bone volume, decreased relative cortical bone area, increased bone turnover, and compromised mechanical strength. |

||

| Impaired GH action |

GHKO (GHTK Tg) (30, 160) |

Complete ablation of GH secretion, significant reductions in serum/tissue IGF-1 |

∼30% decreases in body size | Decreased tail length. Skeletal phenotype was not reported. |

| Lit/lit, ghrh gene mutation (24, 27, 28) |

Undetectable GH, reductions in serum and tissue IGF-1 |

∼30–40% reductions in body size | At 8 weeks of age the mice show ∼25% decrease in femur length, ∼30% decrease in BMD, and slender bones (∼20% decrease in periosteal circumference). |

|

| GHRKO (31, 32) |

Blunted activation of the GHR, reductions in serum and tissue IGF-1 |

∼30–40% reductions in body size | Decreased linear bone growth manifested also by the decreased width of the growth plates. Mice show decreased areal-BMD, decreased radial bone growth, and diminished trabecular bone volume. |

|

| GH antagonist (Tg) (33) | ||||

| STAT5abKO (34) |

∼50% reductions in serum IGF-1. | ∼30–40% reductions in body size | Skeletal phenotype was not reported. | |

| JAK2KO (35, 36) |

NA | Embryonic lethality (d12.5) due to the absence of definitive erythropoiesis |

Skeletal phenotype was not reported. | |

| IGF-1 excess | MTT-1-IGF-1 (Tg) (25, 26, 160) |

Elevations in serum and tissue IGF-1, ∼50% suppression of GH secretion. |

∼20–30% increase in body size apparent at 6–8 weeks of age. |

No increases in linear or skeletal growth, as assessed by measurements of tail lengths, cumulative tibial width growth, or long bone lengths. |

| Impaired IGF-1 action |

IGF-1RKO (41, 44) |

NA | Sever growth retardation, born at 45% of normal size, die at birth. |

Lag of about 2 embryonic days in ossification of cranial and facial bones, delay of about 4 days in the ossification of the interparietal bone, delay of about 2 days in ossification of the bones of the trunk and extremities. |

| IGF-1KO (28, 39, 41, 46, 47) |

Undetectable IGF-1 in serum and tissues. Elevated GH |

70% reductions in overall body size. |

∼40% decrease in linear bone growth, ∼50% decrease in areal-BMD, ∼30% decrease in cortical BMD, and ∼50% decrease in periosteal bone circumference. |

|

| Midi-mouse (IGF-1 mutation) (50, 161, 162) |

Reductions (∼70%) in serum and tissue IGF-1. GH levels not reported |

Skeletal phenotype not reported | ||

| IGF-1 +/− (42, 48, 49) |

20–30% lower serum IGF-I levels in both genders. |

significant reductions in body weight ∼10–20%. |

Reduced femur length (∼5%), reduced femoral BMD (∼7–12%), reduced cortical bone area (∼7- 20%) and periosteal circumference (∼5–13%) with no consistent pattern of change in trabecular bone measurements. |

|

| IGF-1R +/− (gradient of expression) (45) |

Normal serum IGF-1 levels (reduced by 8% only in the extra small mice). |

Gradual decrease in body size with gradual reductions in IGF- 1R gene expression |

Skeletal phenotype was not reported. | |

| IGF-2KO (28, 163) |

Normal GH/IGF-1 levels in serum. | Intra-uterus growth retardation. Catch up of BW post-natally at ∼12 weeks of age. |

At 8 weeks of age, IGF-2 null mice show ∼10% decrease in femoral length, ∼20% decrease in BMD, decrease in radial bone growth (∼10% decrease in periosteal circumference), no changes in cortical BMD. |

|

| Impaired GH/IGF-1 |

GHRKO/IGF- 1KO (52) |

Blunted activation of the GHR, undetectable IGF-1 in serum and tissues. |

∼10–15% of adult body size | Severely decreased linear growth, reductions in the heights of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the growth plate (as compared to single KO alone). Delayed primary and secondary ossification. |

Serum IGF-1 regulates radial bone growth

Congenital reductions in serum IGF-1

Initial studies with IGF-1 haploinsufficient mice strongly suggested that serum IGF-1 is a predictor of body size and skeletal acquisition. Likewise, studies of congenital mice provided in vivo evidence for a functional relationship between allelic differences in IGF-1, serum IGF-1 levels, and bone acquisition (53), such that increases in serum IGF-1 levels associated with increased overall BMD. However, to unravel the contribution of serum versus tissue IGF-1 to skeletal growth new models had to be developed. The first goal was addressing the roles of endocrine IGF-1 (serum IGF-1) in bone mineral acquisition and skeletal growth. To that end, two laboratories independently targeted igf-1 gene expression in the major organ contributing to serum IGF-1, namely the liver. Using the cre/loxP system where the cre recombinase was expressed under the Mx1 promoter (54, 55) the authors showed that ablation of liver-derived IGF-1 (Mx1-IGF-1KO) resulted in significant reductions in serum IGF-1 levels (∼80%) that associated with reductions in total cross-sectional area with no effects on trabecular bone (by pQCT), and minimal effects (∼−6%) on longitudinal bone growth. Similarly, liver-specific IGF-1-defficient (LID) mice were generated using the albumin promoter-derived cre (56, 57) and showed congenital deletion of the igf-1 gene in the liver with 75% reductions in serum IGF-1 levels. LID mice are born in normal in size and show similar body weight to controls up to10 weeks of age. At this point they start falling off and their body weight becomes significantly lower (∼5–10%) than controls (56). Skeletal growth assessed during several ages using micro computed tomography (microCT) showed reductions in total cross-sectional area, cortical bone area, cortical thickness, and BMD, while effects on linear bone growth were minimal (∼−5–6%). Using the same albumin-driven cre the ghr gene was deleted in the liver (Liver-GHRKO mice) (58). Despite >90% decreases in serum IGF-1 levels, Liver-GHRKO mice showed normal tibia and femur lengths, but exhibited marked reductions in BMD and significantly reduced trabecular bone volume (by microCT). Inactivation of the GHR downstream mediators, STAT5ab (59) or JAK2 (60, 61), specifically in the liver (using the same Albumin-driven cre derived) resulted in marked reductions in serum IGF-1. Liver-JAK2KO mice exhibited reduced body weight, body length, and BMD (60, 61). microCT analyses of femurs from 16 week-old mice revealed significant decreases in total cross-sectional area, bone area and cortical thickness (Yakar S, personal statement). Similar to the Liver-GHRKO mice, Liver-STAT5ab mice did not show reductions in body weight despite 50% reductions in serum IGF-1 (59). Unfortunately, their detailed bone phenotype was not reported. Finally, the ALS knockout mice (ALSKO) (62), which showed ∼60% reductions in serum IGF-1 levels, were also used as a model to study the roles of endocrine IGF-1 in skeletal growth. ALSKO mice are born at normal weight but show decreases in body size during early post-natal growth (3 weeks) and remain ∼20% smaller than controls throughout life (63). Detailed morphology of the femurs by microCT revealed reduced total cross-sectional area, cortical bone area, polar moment of inertia, and reduced mechanical properties (by 4-point bending assay). Taken together, the Mx1-IGF-1KO, LID, Liver-GHRKO, and the ALSKO mice show significant decreases in serum IGF-1 levels with compromised cortical bone morphology evident by marked reductions in total cross-sectional area with minor reductions in bone lengths, resulting in slender bones, which are mechanically inferior when compared to controls. The Mx1-IGF-1KO, LID, Liver-GHRKO, and the ALSKO mouse models have taught us that liver-derived IGF-1 (endocrine IGF-1) regulates mainly radial bone growth and has little effects on longitudinal bone growth. It is conceivable that elevations in serum GH levels in the Mx1-IGF-1KO, LID, and the Liver-GHRKO mouse models, allowed GH to retain its ability to activate chondrocytes in the growth plate (evident by only minor reductions in bone length), but was insufficient to compensate radial bone growth, which likely requires normal levels of IGF-1 in serum.

In an attempt to further reduce serum IGF-1 levels, LID mice were crossed with the ALSKO mice to generate double gene disruption of LID/ALSKO (64). Indeed, LID/ALSKO mice exhibited further reductions (85–90%) in serum IGF-1 levels. However, in this case, the mice showed significant reductions in longitudinal bone growth. This was evident by 20% decreases in total height as well as in the heights of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the proximal growth plates of the tibiae in LID/ALSKO mice as compared to controls. Note that the height of the germinal zone (GZ) of the growth plate increased, indicating that with very low levels of serum IGF-1 and extremely high levels of GH, pre-chondrocytes population is increased but proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes is impaired (via mechanisms that were not addressed in that study). MicroCT revealed a 10% decrease in BMD and greater than 35% decreases in periosteal circumference and cortical thickness in the LID/ALSKO mice, suggesting that a threshold concentration of circulating IGF-1 is necessary for normal longitudinal and radial bone growth.

Temporal reductions in serum IGF-1

Note that one of the limitations of the LID, ALSKO, and the Liver-GHRKO mouse models is that they exhibit congenital serum IGF-1 deficiency and thus we cannot separate the effects of serum IGF-1 on the growing skeleton from those on the aging skeleton. To do that we have generated a mouse model which allows temporal deletion of the liver Igf-1 gene. This model is based on the cre/loxp system where the cre recombinase expressed under the trypsin 1 alpha promoter, specifically in the liver, and can be induced by tamoxifen. The inducible liver IGF-1 deficient (iLID) mouse model was used to assess how reductions in serum IGF-1 affect the growing versus the aging skeleton (65). Using the iLID model, we depleted serum IGF-1 at pre- (3.5 weeks of age) and post-puberty (8 weeks of age), at adulthood (16–32 weeks of age), and during aging (52–104 weeks of age) (66) and tested how reductions in serum IGF-1 affected the skeleton, independent of developmental effects. We have found that when serum IGF-1 depleted during early or late growth (4, 8 weeks, respectively), skeletal acquisition was compromised evident by reduced total cross-sectional area, cortical bone area, and cortical bone thickness. When serum IGF-1 was depleted after peak bone acquisition (at 16–32 weeks of age), no changes in skeletal parameters were detected during adulthood. However, reductions in serum IGF-1 throughout aging (52–104 weeks of age) impaired bone integrity in the iLID mice, which was manifested by reductions in all cortical properties and BMD (65). Overall, the iLID mouse model taught us that serum IGF-1 levels play significant roles in establishment of peak bone mass pre and during puberty, and have considerable effects on maintaining a healthy skeleton during aging.

Increases in serum IGF-1

The effects of increases in endocrine IGF-1 on skeletal growth were studied using the hepatic IGF-1 transgenic (HIT) mice, which express the rat-IGF-1 transgene exclusively in liver (under the TTR promoter) and show 2–3 fold increases in serum IGF-1 with normal expression/production of IGF-1 in peripheral tissues. Elevations in liver production of IGF-1 in the HIT mice associate with ∼10% increase in body weight and relative lean mass (67–70) as compared to controls (when mice are on FVB/N genetic background). Linear growth was enhanced on FVB/N genetic background (67–69) but not on C57Bl6/J background (70). All cortical bone traits, measured at the femoral mid-diaphysis, increased in both males and females on FVB/N background effects that were milder on C57Bl6/J background (70). Increases in serum IGF-1 had minimal effects on the trabecular bone compartment, which was dependent on sex and genetic background of the mice.

Mouse models of reductions or elevations in liver-derived IGF-1 have established that diaphysial radial bone growth is regulated by serum IGF-1 (Figure 2). However, we note that in models of IGF-1 reductions in serum (table 2) GH secretion is increased and we cannot rule out the effects of increases in GH on radial bone growth. In fact, inhibition of GH in the LID mice, using a GH antagonist (pegvisomant), reduced femoral total cross-sectional area and cortical bone area, resulting in mechanically inferior bones, suggesting that compensatory increases in GH in states of IGF-1 deficiency (directly through GHR inhibition in bone, or indirectly through further reductions in serum/tissue IGF-1 levels) act to protect against a severe inhibition of bone modeling during growth (71). Lastly, we should mention that serum IGF-1 deficiency, as seen in Mx1-IGF-1KO, LID, and Liver-GHRKO is associated with insulin resistance and some times dyslipidemia, which also impacts bone acquisition.

Figure 2. Mouse models with serum IGF-1 deficiency or excess.

Serum IGF-1 levels (measured by RIA) and microCT 3D images taken at the femoral mid-diaphysis of 2 years old mice. A. Liver-IGF-1 gene deletion (LID) in mice (Albumin-driven cre). B. Liver-GHR gene deletion in mice (Albumin-driven cre). C. ALS gene deletion in mice (ALSKO). D. Hepatic IGF-1 transgene (HIT) expression in mice (TTR-driven rIGF-1).

Table 2.

Mouse models with reductions or elevations in circulating (serum) IGF-1.

| Mouse model (Ref.) | GH/IGF-1 status | Body weight (BW) | Skeletal phenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reductions in serum IGF-1 |

Liver-IGF-1KO (LID), Mx1-IGF-1KO, (54, 55, 57, 114) |

∼75% reductions in serum IGF-1, ∼4fold increase in serum GH. |

∼10% decrease in BW during adulthood. |

∼5% reductions in bone length, ∼20% reduction in total cross-sectional bone area, minimal effects on trabecular bone volume. |

| Liver-GHRKO (58, 164) |

90% reductions in serum IGF-1, ∼10–20 fold increase in serum GH. |

One study show normal BW, another study that followed the mice up to 2 years of age shows a fall of ∼15–50% in BW from 6 months old. Our studies show no change in BW between controls and Liver- GHRKO mice up to 1 year (Yakar personal comment). |

No changes in bone length, ∼10% reductions in total cross-sectional bone area, ∼15% decreases in cortical bone thickness, 20% reductions in trabecular bone (Yakar personal comment). |

|

| ALSKO (62, 63) | ∼60% reductions in serum IGF-1, ∼3fold increase in serum GH (detected only during aging). |

∼15% decrease in BW throughout life span. |

∼10% reductions in femur length, ∼20% reduction in total cross-sectional bone area, 10% reductions in trabecular bone volume. |

|

| LID/ALSKO (64) | ∼85% reductions in serum IGF-1, ∼5fold increase in serum GH. |

∼30% decrease in BW | ∼20% reductions in femur length, ∼50% reduction in total cross-sectional bone area, 40% reductions in trabecular bone volume. |

|

| iLID (65, 66) | Upon induction ∼60% reductions in serum IGF-1 and ∼4fold increase in serum GH. |

No differences in BW when serum IGF-1 depleted at 4, 8, or 16 weeks of age. |

Reductions before 16 weeks of age reduce femoral total cross-sectional area and lead to decreases in trabecular bone volume. Reductions in serum IGF-1 during aging significantly reduce all cortical traits, minimal effects seen in trabecular bone. |

|

| Liver-STAT5KO (59) | ∼60% reductions in serum IGF-1, ∼5–10fold increase in serum GH |

∼20% reductions in BW (up to 3–4 months of age), ∼20% increase in BW (by 17 months) due to increased body adiposity. |

Skeletal phenotype was not reported. | |

| Liver-JAK2KO (60, 61) |

∼80% reductions in serum IGF-1, ∼3fold increase in serum GH |

∼20% reductions in BW (up to 6 months of age) |

No changes in bone length, ∼15% reductions in total cross-sectional bone area, ∼15% decreases in cortical bone thickness, no significant differences in trabecular bone (Yakar personal comment). |

|

|

Elevations in serum IGF-1 |

Congenic models (53) |

∼20% increase in serum IGF-1, GH levels were not reported. |

No differences in BW between controls and congenic mice. |

Congenic mice showed ∼10% increases in trabecular bone, differences in cortical bone parameters did not reach significance. |

| HIT (67–70) | ∼2fold increase in serum IGF-1 levels, no detectable differences in GH levels between controls and HIT. |

∼25% increase in BW depends on the genetic background. |

∼5% increase in femoral length, ∼10% increase in total cross-sectional area, increased tissue mineral density. |

Bone tissue GH/IGF-1 axis plays fundamental roles in skeletal acquisition

Approaches to study the contribution of autocrine/paracrine IGF-1 to skeletal growth in more detail became feasible in the last 10 years and significantly advanced our understanding of bone accrual, maintenance, and aging (table 3). We will discuss first the impairment of the whole body autocrine/paracrine route of GH/IGF-1, and move on to bone cell-specific increases/decreases in GH/IGF-1 action.

Table 3.

Mouse models with bone expression/ablation of members of the GH/IGF-1 axis.

| Mouse model (Ref.) |

GH/IGF-1 status | Body size | Skeletal phenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Autocrine/ paracrine actions of IGF-1 |

KID/KIR (72) | ∼90% reductions in seum IGF-1, increases in GH, Enhanced IGF-1 actions in tissues |

10–20% increase in BW. | Increased bone length. Increased total-cross-sectional area, cortical bone area, cortical thickness, and increased trabecular bone volume |

| IGF-1KO-HIT (67– 69) |

2–3 fold increase in serum IGF-1, no changes in serum GH levels, no tissue IGF-1 expression |

Normal BW. | Decreased bone length and cortical bone parameters up to 4 weeks. Catch-up growth (linear and cortical bone parameters) seen at 8–16 weeks of age. |

|

| GHRKO-HIT (70) | Normal IGF-1 levels in serum, no GHR action in all tissues, decreased IGF-1 gene expression in all tissues |

∼20% decrease in BW (intermediate between GHRKO and control mice). |

Decreased bone length (∼20%). Cortical bone parameters decrease by 30–40%. Trabecular volume decreased in males, no change detected in females. |

|

|

Bone cell- specific overexpression of members of the GH/IGF axis |

Osteoblast -IGF-1 Tg (osteocalcin promoter) (96) |

Normal IGF-1 levels in serum. IGF-1 levels increased in osteoblasts. |

Normal BW. | Increased trabecular bone volume (∼30%) accompanied by increased bone formation rate. No effects on cortical bone. |

| Osteoblast -IGF-1 Tg (col1a1–3.6 promoter) (97, 98) |

A few lines showed increase in serum IGF-1 levels. IGF-1 levels increased in osteoblasts. |

A few lines showed increase in BW. |

Femur length, cortical width and cross-sectional area were increased in transgenic femurs of the highest expressing line. Femoral trabecular bone volume was not affected. Bone remodeling increased. |

|

| Osteoblast -hGH Tg (osteocalcin promoter) (9, 95) |

Serum levels of GH/IGF-1 were not reported. hGH levels increased in osteoblasts. |

20% increase in BW. | Increased bone length (∼8%). Increased total-cross-sectional area (15%), and increased cortical bone thickness (∼10%). Bone mineral content significantly reduced. |

|

|

Bone cell specific ablation of members of the GH/IGF axis |

Chondrocyte-IGF- 1R (Col2a1-cre, Tam-Col2a1-cre) (90, 91) |

Serum levels of GH/IGF-1 were normal. |

∼10% reductions in BW. | Decreased linear-growth, disorganized growth plate, hyporoliferation and increased apoptosis of chondrocytes. |

| Chondrocyte -IGF- 1, (Col2a1-cre) (89) |

Serum levels of IGF-1 were normal. |

∼10% reductions in BW. | Decreased bone length (∼3.5%), no difference in total vBMD. Reduced periosteal and endosteal circumferences. |

|

| Osteoblast-IGF- 1RKO (osteocalcin-cre) (102, 103) |

Serum levels of GH/IGF-1 were not reported. |

Normal BW. | Decreased trabecular bone volume, and decreased trabecular bone mineralization rate. Reduced cortical bone thickness and BMD. |

|

| Osteoblast -IGF- 1KO (Col1a2-cre) (100, 101) |

Serum levels of IGF-1 were normal. |

∼30% reductions in BW. | Decreased bone length (18–24%). Reduced femur areal BMD (10–25%), reduced periosteal circumference (30%), reduced mineral apposition rate (14–30%) and bone formation rate (35–57%). |

|

| Osteocyte-IGF- 1KO (DMP-1-cre) (104, 153) |

Serum levels of GH/IGF-1 were normal. |

∼15% reductions in BW (Yakar personal comment; Normal BW in our hands,). |

Decreased bone length (∼5%). Reduced femoral total cross-sectional area (20%), no effects on trabecular bone. (Yakar personal comment; we found normal bone length, reductions in total cross-sectional area (15%) in males only, no effects on trabecular bone were noted). |

|

| Osteocyte-IGF- 1RKO (DMP-1-cre) |

Serum levels of GH/IGF-1 were normal. |

Normal BW. | Yakar personal comment; Normal bone length. Reduced relative cortical bone area (20%) and cortical bone thickness (8%) and reduced trabecular bone volume in females. |

|

| Osteocyte-GHRKO (DMP-1-cre) |

Serum levels of GH/IGF-1 were normal. |

Normal BW. | Yakar personal comment; Normal bone length. Reduced femoral total cross-sectional area (∼15%) and reduced trabecular bone volume (∼25%). |

Impairment of the whole body autocrine/paracrine route of GH/IGF-1

To unravel the contribution of tissue IGF-1 to overall body growth, two knock-in mouse models of mutated IGF-1 were generated. The first, a knock-in mouse of Des-IGF-1 (KID), which express an IGF-1 peptide with a three amino acid truncation at the N-terminus; and the second, a knock-in mouse of R3-IGF-1 (KIR), which express an IGF-1 where the glutamine at position 3 was substituted with arginine (R) (72). Both IGF-1 mutants have several times lower affinity to IGFBP-3 and significant reductions in binding to all other IGFBPs. The KID and KIR mice expressed the mutant IGF-1s under the endogenous IGF-1 promoter and allowed the study of the autocrine/paracrine effects of IGF-1, independent of the IGFBPs. KID and KIR mice had almost undetectable levels of IGF-1 in serum, due to decreased IGF-1 stability and half-life. However, in tissues, IGF-1 bioavailability increased (as it was not bound to IGFBPs), evident by significant increases in body weight, body length, and relative lean mass, in both male and female mice. Surprisingly, all cortical bone traits, trabecular bone volume and mechanical properties increased in KID and KIR mice relative to controls. These models have demonstrated that autocrine/paracrine IGF-1 can enhance skeletal growth independent of serum IGF-1.

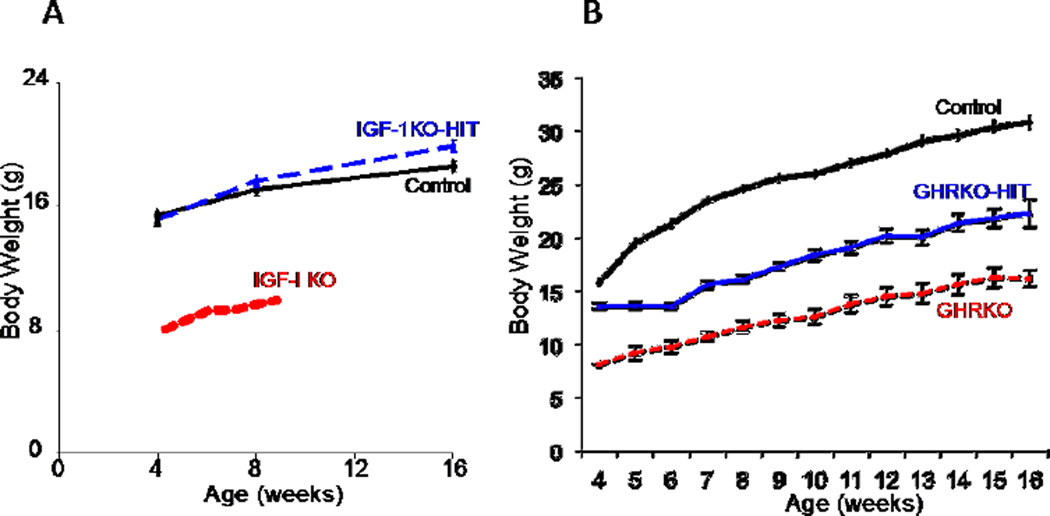

Using a crossing strategy we generated an IGF-1 null mouse (IGF-1KO) where the endocrine IGF-1 was restored via a hepatic IGF-1 transgene (HIT), namely IGF-1KO-HIT mice (67–69). The IGF-1KO-HIT mice have no IGF-1 production in any tissues but express the hepatic IGF-1 transgene (HIT) and thus show 2–3 fold increases in serum levels of IGF-1. Unlike the IGF-1KO mice, which are severely growth retarded, the IGF-1KO-HIT mice showed normal body size. Bone length of the IGF-1KO-HIT mice was similar to that of controls at 8 and 16 weeks of age. Likewise, radial bone growth assessed by total cross-sectional area and cortical bone area was similar between controls and IGF-1KO-HIT mice at 8 and 16 weeks. Nonetheless, notably at 4 weeks of age, cortical skeletal traits of the IGF-1KO-HIT mice decreased as compared to controls and a catch-up growth was seen during puberty. The IGF-1KO-HIT model strengthened our previous conclusion that tissue IGF-1 is critical for early postnatal growth. However, this model also shows that elevated serum IGF-1 can fully compensate for a postnatal absence of tissue IGF-1 both morphologically and mechanically (67–69). We should also note that the GHR and the IGF-1R were intact in all tissues of the IGF-1KO-HIT mice. Thus, we cannot exclude the contribution of both receptors to skeletal acquisition. Lastly, the effects of increases in serum IGF-1 in the IGF-1KO-HIT mice on skeletal acquisition do not hold during advanced adulthood, when bone loss becomes more prevalent (69). The rate of trabecular bone loss during aging in the IGF-1KO-HIT mice was similar or greater than controls, suggesting that tissue/bone igf-1 gene expression is also essential for skeletal integrity during aging. In this context we mention a study, which used a similar crossing strategy to generate an IGF-1 null mouse that expressed IGF-2 under the ubiquitous phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase promoter (PEPCK) (73). However, despite wide expression of IGF-2 in tissues and increased IGF-2 levels in serum, postnatal growth of the IGF-1KO/IGF-2 mice was not rescued, suggesting that IGF-1 is the main growth factor postnatally.

To understand whether GH-mediated bone accrual depends on serum IGF-1 levels, we crossed the GHRKO mice with HIT mice to generate GHRKO-HIT mice (70). The GHRKO-HIT do not possess any GHR activity (due to gene deletion), however their serum IGF-1 levels are similar to controls (owing to the HIT expression). Restoration of serum IGF-1 levels in the GHRKO-HIT were insufficient to fully restore body size when GHR is ablated (Figure 3). Skeletal phenotype of the GHRKO-HIT corresponded to body size. Cortical bone parameters of the GHRKO-HIT mice were intermediate between the GHRKO and control mice. As such, total cross-sectional area, cortical bone area, and cortical bone thickness in GHRKO-HIT mice were larger than those in the GHRKO mice but smaller than in controls. To understand better why the liver igf-1 transgene (HIT) that restored body and bone size in IGF-1KO-HIT mice cannot restore body size in the GHRKO mice, we measured serum levels of the IGFBP-3 and the ALS carrier proteins. We found that although IGF-1 levels in serum of the GHRKO-HIT mice normalized, their IGFBP-3 and ALS levels were undetectable, suggesting that the IGF-1 delivery system was compromised and that IGF-1 was delivered to tissues in a “short-living” binary complex or free form (70). Additionally, we found that bone/tissue igf-1 gene expression was not restored in the GHRKO-HIT mice, again suggesting that bone IGF-1 is important for skeletal acquisition. Importantly, the GHRKO-HIT model reinforced the importance of IGF-1-independent effects of GH on skeletal acquisition. Linear growth inhibition in the GHRKO-HIT mice may result from the lack of GHR activation in cells at the growth plate (prechondocytes/resting cells) and perichondrium, which is required to promote the resting cells to differentiate and become responsive to IGF-1. This situation resembles the treatment of Laron’s dwarfs with IGF-1 that partially stimulated longitudinal bone growth but never normalized growth (74).

Figure 3. Endocrine IGF-1 restores growth retardation of the IGF-1 null mice, but is insufficient to restore growth in the GHR null mice.

A. Body weights of control, IGF-1KO-HIT and IGF-1 null (IGF-1KO) mice (FVB/N genetic background). B. Body weights of control, GHRKO-HIT and GHR null (GHRKO) mice (FVB/N genetic background).

GH/IGF-1 axis in the growth plate regulates linear growth

Most of skeletal bones (except the flat bones of the skull) mineralize via endochondral ossification, which involves replacement of a cartilage template by a bone tissue. The cartilage is formed by chondrocytes, which proliferate and undergo hypertrophy in the prospective mid-shaft of the bone. A primary ossification center is then formed by osteoblasts in the bone collar. In long bones, a secondary ossification center is formed at each end of the bone, leaving chondrocytes in the growth plate to proliferate and increase bone length until growth is ceased.

The growth plate is a multi-cellular complex structure, comprised of three zones: the resting/germinal zone, the proliferating zone, and the hypertrophic zone. The resting zone contains chondrocyte progenitor cells, which upon hormonal stimulation undergo proliferation. The proliferating zone is composed of replicating chondrocytes that form a column-like structure. Finally, the hypertrophic zone contains terminally differentiated chondrocytes, which undergo apoptosis, allowing resident osteoblasts and osteoclasts in the metaphysis to remodel and calcify the cartilage into a bone tissue. The rate of longitudinal bone growth is determined by the rate of chondrocyte entry from the germinal zone into the proliferating zone, multiplied by the maximal height of hypertrophied chondrocytes. A key to understanding longitudinal growth is defining the molecular regulation of chondrogenesis at the growth plate.

Chondrocytes express receptors for GH (75) and IGF-1 (76), and chondrocyte-derived IGF-1 has been proposed to play significant roles in longitudinal bone growth (77). In the early 1990s, Nilsson et al clearly demonstrated that in hypophysectomized rats the number of IGF-1-positive cells in the epiphysial growth plate significantly decreased and treatment with GH restored it (78). This group also showed that GH was able to stimulate local production of IGF-1 in the growth plate (79), studies that were supported by in vitro experiments with primary chondrocyte cultures (80, 81). However, the target cells at the growth plate, which respond to peaks of GH leading to enhanced chondrogenesis and ossification were a matter of debate for many years. Studies in the 1990s (82–85) have shown that GH stimulates cell division of pre-chondrocytes, residing at the germinal layer and at the perichondrial ring, driving them into a “clonal-expansion mode” that occurs at the proliferation zone. In the late 1990s, Wang J et al described detailed analyzes of the growth plate of the IGF-1 null mice (86). In that study it was found that chondrocyte proliferation and cell numbers in the IGF-1 nulls are preserved despite significant (∼35%) reductions in long bone growth, and could be attributed to the high levels of GH present in the IGF-1 nulls. The growth defect in those mice was attributed to an attenuation of chondrocyte hypertrophy, which associated with reduced chondrocyte metabolism and matrix production, suggesting that IGF-1 plays a role in chondrocyte hypertrophy. About 5 years later, histological mapping of the direct cellular targets for GH in the growth plate of normal, GH-deficient, and fasting mice and rats (87), revealed that GH stimulates pre- and early chondrocytes, and loses its effects as chondrocytes differentiate (with diminished effects on hypertrophic chondrocytes).

IGF-1R is present in a gradient along the growth plate, where the highest levels are found in the germinal zone (88). The ligand, IGF-1, is highly produced in the proliferating zone and its expression significantly reduced in hypertrophic chondrocytes. Chondrocyte-specific ablation of the IGF-1 gene (89) using the type II collagen I (Col2a1)-driven cre, resulted in decreased body length, areal BMD, and bone mineral content. Surprisingly, radial bone growth also decreased by ∼7%, and may be attributed to reductions in IGF-1 production by perichondrial cells, or decreased paracrine action of chondrocyte-derived IGF-1 on cells of the perichondrium. However, when the IGF-1R was ablated in chondrocytes using the same promoter (Col2a1) it resulted in a more severe phenotype with shorter bones, disorganized chondrocyte columns, delayed ossification and under-mineralized skeletons (90). Note that in the case of chondrocyte-specific IGF-1KO mice, circulating IGF-1 may compensate for the lack of local IGF-1 production, while in the case of chondrocyte IGF-1RKO this cannot happen, therefore leading to a more severe phenotype. In a recent study using tamoxifen inducible Col2a1-derived cre to delete the IGF-1R in the growing mice (91), the authors showed diminished body and tibial growth, and reduced chondrogenesis by histology (accompanied by hypoproliferation and increased chondrocyte apoptosis). Importantly, ablation of the IGF-1R in chondrocytes resulted in significant delay in chondrocyte terminal differentiation that was reflected by a shorter hypertrophic zone and reduced bone length, suggesting once again that IGF-1 plays important roles in chondrocyte hypertrophy. Lastly, studies on GHR inactivation in chondrocytes (using the Col2a1-derived cre) are on going, and will help us understand the interplay between IGF-1 and GH in the growth plate.

Collectively, the above in-vivo data strengthen the “dual effector hypothesis” suggested by Green et al (92). This hypothesis suggests that the resting cells of the growth plate, the perichondrium, and the groove of Ranvier are targets for GH, which drives pre-chondrocytes at this region to proliferate, while IGF-1, locally produced, has major roles in chondrocyte proliferation (clonal expansion at the proliferating zone) and possibly chondrocyte hypertrophy (Figure 4).

Figure 4. GH/IGF-1 axis controls longitudinal bone growth.

A. Coronal section of tibia viewed with Masson tri-chrome staining. Anatomical locations indicated, including the three zones of the growth plate: germinal zone (GZ), proliferating zone (PZ), and hypertrophic zone (HZ). Red arrows indicate the sites of GH or IGF-1 actions. B. A schematic representation of maximal GH or IGF-1 action along the three zones of the growth plate during growth. IGF-1 actions were reported mainly along the proliferative zone, while GH actions reported at the germinal zone.

GH/IGF-1 axis in osteoblasts and osteocytes regulates mineral acquisition and bone remodeling

Receptors for GH and IGF-1 are found on all osteogenic cells including osteoblasts, osteocytes and osteoclasts. Histological examination of bone sections revealed that IGF-1 expression associated with regions of ossification in the metaphysical trabecular bone as well as the endosteal surfaces (93, 94). Later on, in-vivo and in-vitro studies have shown that osteoblasts are major target of IGF-1 in bone. IGF-1 stimulates osteoblast recruitment and differentiation as evident by increased type 1 collagen production and enhanced alkaline-phosphatase activity. IGF-1 also plays roles in osteocyte function and response to mechanical stimuli (described below). On the other hand, the direct effects of GH on osteoblasts and osteocytes were not fully determined. As described below, there is evidence that GH affects diaphysial bone growth in an IGF-1-dependent manner.

Bone cell-specific overexpression of members of the GH/IGF-1 axis

One of the first attempts to understand the effects of the GH/IGF-1 axis specifically in osteogenic cells was creating mice that express the hGH under the osteocalcin promoter (OC-hGH mice) (9, 95). Although we now know that the hGH activates also the prolactin receptor in bone, we can learn how increases in local production of GH affects skeletal growth. Expression of the hGH transgene in the OC-hGH mice was limited to osteoblast, with negligible systemic effects. OC-hGH mice showed longer femora with significant increases in mid-diaphyseal cross-sectional area. However, this associated with a smaller fraction of ash, larger fractions of woven bone and cartilage islands, and a greater intracortical porosity. Thus, local increase in GH action in bone exerts anabolic effects but these are at the expense of bone integrity. Targeting the IGF-1 expression to osteoblasts via the osteocalcin promoter (OC-IGF-1 mice), did not lead to significant increases in systemic IGF-1 levels, but had anabolic effects on bone as was evident by 2fold increase in bone formation rate, increased trabecular bone volume, and increased BMD (96). Despite increase in bone formation, the number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts did not differ from controls, suggesting that in OC-IGF-1 mice, osteoblasts activity increased. In contrast, targeting the IGF-1 expression to osteoblasts via the Col1a1(3.6) promoter resulted in increased bone formation and bone resorption as evident by increased collagen content, cellular replication, and osteoclast number (97, 98). The authors reported thickening of the calvarial bone, increases in femoral length and cross-sectional bone area, and almost no effects on the trabecular bone compartment. The discrepancy between these studies are likely due to the different promoters used to drive the IGF-1 transgene and the resulting differences in the temporal and spatial pattern of the transgene expression. In that context, we should mention a study by Susan L Hall et al who transplanted sub-lethally irradiated wild type mice with Sca1+ stem cells overexpressing the hGH (99). The recipient mice showed 50% increases in serum IGF-1 levels however, increases in hGH gene expression in bone and the bone marrow associated with significant decreases in trabecular bone volume and 2.5fold increases in osteoclast number and osteoclastic surface per bone surface, suggesting that excess GH/IGF-1 signaling in bone enhances not only bone formation, but also bone resorption.

Bone cell-specific inactivation of members of the GH/IGF-1 axis

The role of IGF-1 in osteoblast function was studied in two conditional mouse models. In the first model IGF-1 was ablated using the Col1a2 promoter-driven cre (100, 101). Col1a2-IGF-1KO mice showed severe growth retardation and impaired bone mineralization. Additionally, bone formation in Col1a2-IGF-1KO mice reduced at the periosteal and endosteal surfaces due to decreased osteoblasts number/function. Note that analyses of gene recombination in the various tissues of the Col1a2-IGF-1KO mice revealed decreases in IGF-1 gene expression in the liver, kidney, heart and skeletal muscle, which could have impacted the skeletal phenotype. In the second model the authors used osteocalcin-derived cre to ablate the IGF-1R in osteoblasts (OC-IGF-1RKO mice) (102). OC-IGF-1RKO mice showed normal body weights, body lengths, and femoral lengths. However, OC-IGF-1RKO mice exhibited marked reductions in trabecular bone volume and showed significantly reduced trabecular bone mineralization rate (102, 103). Cortical bone in OC-IGF-1RKO mice was minimally affected, with reduced cortical thickness and cortical BMD (103).

Recent studies have focused on the roles of the GH/IGF-1 axis in the most abundant cells in bone, the osteocytes. Ablation of the GHR, IGF-1R, or the IGF-1 in osteocytes was achieved using the DMP-1 promoter-driven cre. Although this promoter is relatively specific to osteocytes and mature osteoblasts, there are reports that it is expressed in other cell types such as muscle and brain and thus conclusions should be drawn carefully. Ablation of GHR in osteocytes did not affect body weight, body composition or organ weights (Yakar, paper in review). Linear growth was not affected, evident by similar femoral lengths between controls and the DMP-GHRKO mice. MicroCT analyses revealed that inactivation of the GHR in osteocytes led to slender bones with reduced total cross-sectional area and cortical bone area in both sexes. The DMP-GHRKO mice exhibited significant reductions in trabecular bone (in both sexes) when compared to controls. Histomorphometry of femurs revealed significant reductions in endosteal mineral apposition and bone formation rates. To assess whether the reduced bone accrual in response to Dmp-1-mediated Ghr gene deletion was mediated by IGF-1, Dmp-1-mediated Igf-1 receptor (Igf-1r) gene deleted mice were generated (Yakar, paper in review). Ablation of the IGF-1R in osteocytes (DMP-IGF-1RKO) in mice did not affect body weight or organ weights in either sex. Likewise, serum IGF-1 levels in DMP-IGF-1RKO mice were similar to controls. Micro-CT analyses of femora from male and female mice revealed a significant reduction in cortical bone area and a reduced cortical bone thickness in both sexes. Notably, relative cortical bone area (RCA) decreased by ∼20% in both male and female mice. The decrease in RCA was accompanied by 40–50% increases in the marrow area compared with controls, suggesting that endosteal resorption was increased following IGF-1R ablation in osteocytes. The trabecular bone compartment exhibited a mild phenotype in females, where the %bone volume/total volume reduced. A similar approach was used to knockdown the IGF-1 in bone (DMP-IGF-1KO mice) (104). The DMP-IGF-1KO mice showed reduced body weight at 4, 8, and 16 weeks of age, with significant reductions in bone lengths. Here again, serum IGF-1 levels in DMP-IGF-1KO mice were similar to controls. Skeletal characterization revealed that the DMP-IGF-1KO mice exhibit slender bones with reduced total cross-sectional area and reduced cortical bone area in both sexes. The slender phenotype associated with reduced periosteal bone formation and mineral apposition rates during pre-pubertal and pubertal growth. Collectively, ablation of the GHR, IGF-1R, or the IGF-1, in osteocytes led to significant decreases in cortical bone with minimal (∼5%) effects on linear bone growth, suggesting that the GH/IGF-1 axis regulates not only the height of the growth plate, but also radial growth of the long bones diaphysis via its actions on osteocytes.

The effects of IGF-binding proteins on bone

Six IGFBPs were identified so far, with each having different tissue distribution, levels of expression, and post-translational modifications, as well as different proteases that act upon the IGFBPs which consequently liberate the IGFs. Most of the binding proteins possess IGF-1-dependent and independent effects, on cellular proliferation and apoptosis. Several mouse models of overexpressing IGFBPs ubiquitously or under cell specific promoters and several mouse models with IGFBPs gene ablation have been generated over the past two decades (Table 4). Expression of IGFBPs was detected in bone marrow (except for IGFBP-1), osteoprogenitors, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes (reviewed in (105)), clearly suggesting that they are involved in skeletal acquisition.

Table 4.

Mouse models with impaired IGFBP action

| Mouse model | GH/IGF-1 status | Body size | Skeletal phenotype | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic ablation of IGFBPs |

IGFBP-2KO (113, 165) | ∼10% increase in serum IGF-1. |

Normal | Gender-, age-, and compartment-specific effects of IGFBP-2KO mice. Males show diminished trabecular bone, while females show increased cortical bone parameters. |

| IGFBP-3KO (114, 115) | ∼30% reductions in serum IGF-1. |

∼5% increase in BW | No effects on the cortical bone compartment. Significant reductions in trabecular bone volume. |

|

| IGFBP-4KO (115, 166) | Not reported | ∼10% decrease in BW. | Not reported | |

| IGFBP-5KO (115, 167) | Normal | Normal | Not reported | |

| IGFBP-3-4-5KO (115) | ∼50% reductions in serum IGF-1. |

∼25% decrease in BW. | Not reported | |

| Over expression of the IGFBPs |

a1-antitrypsin-IGFBP-1 Tg (106, 107) |

∼50% reductions in serum IGF-1. |

∼20–30% decrease in BW. | Intrauterine growth retardation. Postnatal growth retardation and delayed mineralization (delayed suture closure at the skull, reduced BMD). |

| MTT-IGFBP-1 Tg (168) | Not reported. | |||

| PGK-IGFBP-1 Tg (169) | Not reported. | |||

| Endogenous promoter- IGFBP-1 Tg (170) |

Normal | |||

| AFP- IGFBP-1 Tg (mouse alpha-fetoprotein) (171) |

Normal | |||

| CMV-IGFBP-2 Tg (172) | Normal | ∼5–10% decrease in BW. | ∼3% decrease in femoral length, ∼20% reduced femoral volume but BMD was not affected. |

|

| CMV-IGFBP-3 Tg PGK-IGFBP-3 Tg (109, 173) |

∼2fold increase in serum IGF-1 (likely bound to IGFBP-3). |

∼10% decrease in BW. | Reduced cortical bone volume and BMD. Reduced trabecular bone volume. Reduced bone formation and increased bone resorption. |

|

| OB-IGFBP-4 Tg (110) | Not reported. | ∼25% decrease in BW. | Decrease in femoral length and total bone volume due to ∼50% reductions in bone turnover. Decreased BMD, decreased radial bone growth evident by decreased periosteal and endosteal circumference. |

|

| CMV-IGFBP-5 Tg (111), | Not reported. | ∼30% decrease in BW and body length. |

∼10% decrease in bone length, decrease in radial bone growth, ∼20–30% decrease in BMD. |

|

| OB-IGFBP-5 Tg (112) | Normal | ∼30% decrease in BW at 2–4 weeks, which was resolved in adulthood. |

Decreased trabecular bone volume and osteopenia during growth (4–5 weeks) resolved in older mice. |

|

| IGFBP- proteases |

PAPP-A KO (166, 174) | Normal | ∼40% decrease in BW. | Delay in embryonic skeletal ossification centers in the clavicle, facial and cranial bones, vertebrae, and the digits of the forelimbs and hind-limbs. Impaired chondrogenesis during fracture healing. |

| OB-PAPP-A Tg (175) | No differences in BW in adult mice (12 weeks). |

Increase in bone size at multiple skeletal sites due to increased bone formation. |

||

| IGFBP-4KO/PAPP-A KO (166) |

∼20% decrease in BW. | Not reported |

Excess of IGFBPs

Mice overexpressing the hIGFBP-1 in hepatocytes (under the a1 antitrypsin promoter) showed severe growth retardation (decreased linear growth) with mineralization defects and reduced BMD (106, 107), effects that were likely mediated by sequestering IGF-1. Ubiquitous overexpression of the IGFBP-2 did not affect linear growth, however, but rather resulted in slender bones with significantly reduced BMD (108). Two transgenic mouse models of the hIGFBP-3 mice were generated; one where the hIGFBP-3 expressed under the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and the other under the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter (109). Both models showed reduced total volumetric BMD and cortical BMD measured in the femur, as well as reduced mineral trabecular bone volume associated with increased osteoclast numbers. Targeted overexpression of IGFBP-4 in osteoblasts under the osteocalcin promoter resulted in reduced trabecular bone formation and severely impaired overall postnatal skeletal growth, effects that were attributed to the sequestration of IGF-1 by IGFBP-4 and consequent impairment of IGF-1 action in skeletal tissue (110). Overexpression of IGFBP-5 under the CMV promoter associated with reduced BMD in a gender and age dependent manner, with males affected more severely (111). Histomorphometry revealed that periosteal bone formation rate and mineralizing surface decreased in the IGFBP-5 transgenic mice, while at the endosteal surface these were increased. When IGFBP-5 was expressed in osteoblasts under the osteocalcin promoter it resulted in decreases in trabecular bone volume, impaired osteoblastic function, and osteopenia (112). Overall, transgenic overexpression of the IGFBPs ubiquitously or specifically in osteoblasts resulted in inhibitory effects on bone acquisition.

Inactivation of IGFBPs

Ablation of IGFBP-2 (IGFBP-2KO) associated with a 10% increase in serum IGF-I levels and resulted in gender and compartment-specific changes in bone (113). Male mice had shorter femurs, reduced cortical bone area, and a 20% reduction in the trabecular bone volume fraction due to thinner trabeculae. The reduced trabecular bone fraction associated with reduced bone formation indices. However, female mice showed increased cortical thickness with a greater total cross-sectional area compared with controls, and no effect on trabecular bone (113). Unlike the striking effects of IGFBP-2 ablation on bone morphology and BMD, ablation of IGFBP-3 in mice (IGFBP-3KO) did not affect cortical bone morphology but resulted in 30% decrease in trabecular bone volume associated with increases in the expression of the osteoclasts inducer, RANKL (114). IGFBP-4, the most abundant IGFBP in bone, plays important roles in intrauterine growth. Surprisingly, ablation of IGFBP-4 in mice (IGFBP-4KO) led to prenatal growth-deficit (∼10%) that persisted postnatally (115), suggesting that IGFBP-4 regulates the extravascular pool of IGF-1 (protecting it from degradation) thus controlling IGF-1 activity. Liberation of IGF-1 from IGFBP-4 is controlled by the pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A), the IGFBP-4 protease. Ablation of PAPP-A does not allow liberation of the IGF-1 from its binary complex with IGFBP-4 and consequently lead to inhibition of in IGF-1 action. Ablation of PAPP-A in mice (PAPP-AKO (116) did not alter serum IGF-1 levels but reduced IGF-1 activity in tissues. Specifically, PAPP-AKO mice exhibited decreases in linear growth, cortical bone thickness, trabecular bone volume, and decreases in BMD, all associated with low-turnover osteopenia. IGFBP-4KO, IGFBP-4 transgenic, PAPP-A-resistant IGFBP-4, and the PAPP-AKO mouse models show again the importance of local/tissue IGF-1 in skeletal acquisition.

GH/IGF-1 axis in bone regulates anabolic response to loading

Mechanical loads on the skeleton are important in determining bone morphology and integrity. Loading exerts anabolic responses by increasing bone formation, while lack of mechanical loads, such as those seen in immobilization studies (117, 118) result in rapid bone loss. Loads on the skeleton produce strains in the bone matrix, which generate interstitial fluid flow via the lacunar/canalicular spaces that connect between osteocytes. The skeleton senses strain magnitude (119, 120), strain rate (121, 122), and strain gradients (123, 124) and responds by activation of signaling pathways leading to bone formation. The cells responsible for transducing mechanical stimuli are the osteoblasts and osteocytes, which reside on bone surfaces and in the bone matrix, respectively. Shortly after mechanical stimulus there are fluxes of calcium (125–129), production of prostaglandins (126, 127, 129), production of NO (125, 130–133), and the release of ATP (134–136) that trigger bone formation programs. The secondary strain-induced effects include activation of the Wnt/b-catenin pathway (137–140), activation of IGF-1 signaling (127, 141–145), TGF-b (146), the estrogen receptor (ER) (130, 141, 147) pathways, and inhibition of the sclerostin pathway (137). We should note that the bone adaptive response to mechanical loads does not depend on one pathway, but is a result of integrated network-pathways that ultimately determine the outcome. We focus below on the roles of IGF-1 signaling in bone adaptive response to mechanical loads.

There is considerable evidence that IGF-1 is a strong mediator of the anabolic response to mechanical loading. Both in vitro and in vivo models of mechanical loading showed an increase in Igf-1 gene expression after mechanical stimulation (139, 148, 149). 4-point bending of the tibia mid-shaft in naïve rats induced a rapid increase (after 6 hours) in IGF-1 mRNA in endocortical osteocytes (149). This was consistent with previous studies showing an increase in IGF-1 production 4 hours following 4-point bending on the periosteal surface of the rat tibia (150), and an increase in osteocyte IGF-1 mRNA 6 hours after using the invasive vertebra compression model (151). Using transgenic mice expressing the Igf-1 transgene specifically in osteoblast (under the osteocalcin promoter) loads were applied (noninvasively) at the proximal tibia and resulted in increased periosteal bone formation with 5fold increases in bone formation rate (152). Conversely, in a mouse model with conditional IGF-1KO in type-1α collagen (Col1α) expressing cells, Subburaman M et al demonstrated a blunted response to loading of the tibia, suggesting an essential role for local IGF-1 production in bone anabolic response to mechanical loads (100). Conditional ablation of the igf-1 gene in osteocytes compromised periosteal bone growth and resulted in blunted bone response to 4-point bending. This was associated with significant decreases in the expression levels of cox2, c-fos, and igf-1 (the early mechanosensitive genes) in bone and reduced Wnt signaling (153). Skeletal unloading, on the other hand, induces osteopenia. In a series of studies, Bikle DD et al showed that hind limb suspension in the rat inhibited activation of IGF-1R signaling pathways in normal (154) as well as in GH-deficient dwarf rats (155, 156). This inhibition associated with reduced osteoblast progenitors, their differentiation, and hence, reduced bone formation even following increases in IGF-1 levels in serum, suggesting that unloading induced resistance to IGF-1 in bone. Unloading of mice with ablation of the IGF-1R in osteoblasts (OC-IGF-1RKO, using the osteocalcin promoter-driven Cre) significantly reduced bone formation at the periosteal and endosteal surfaces. Further, while in control mice reloading recovered periosteal and endosteal bone formation rates, reloading of the OC-IGF-1RKO mice resulted in blunted response at the periosteal surface and a very minor response at the endosteum (157).

The exact mechanisms by which IGF-1R elicits bone formation are not yet resolved. However, recent studies indicate that interactions between the IGF-1R and the integrin aVb3 may be involved (155). Other studies have implicated that ephrins and Eph receptors in IGF-1-mediated anabolic response to loads in bone (100). Future studies will address how integrins or the Eph/ephrins are involved.

Summary/highlights

We have summarized above only a fraction of the extensive studies that were done to elucidate the roles of the GH/IGF-1 axis in skeletal growth and metabolism. In vitro studies with cell lines and primary cultures of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, chondrocytes, and osteocytes have significantly advanced our understanding of the molecular regulation of GH/IGF-1 and the molecular targets of this axis. However, these studies have only been reviewed to a small extent here. Likewise, studies on the interactions between the GH/IGF-1 axis and other hormones involved in skeletal regulation, such as sex steroid hormones, the thyroid hormone, and PTH were not discussed. Nonetheless, this review includes many mouse models that, together with earlier in vivo studies in rodents, aiming to differentiate between the effects of GH and IGF-1 on skeletal growth, have taught us the following:

GH and IGF-1 have distinct and overlapping effects on the skeleton. Both hormones elicit their effects on chondrocytes, osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes via binding to their cognate receptors.

Systemic excess of GH or IGF-1 enhances morphological skeletal traits but is associated with compromised tissue composition and skeletal integrity.

Global inactivation of GH or IGF-1 actions causes linear and radial skeletal growth retardation.

IGF-1 null mice exhibit a more sever growth retardation and skeletal abnormalities than GHR null mice, supporting GH-independent effects of IGF-1 on the skeleton.

Circulating (endocrine) IGF-1 regulates radial bone growth of the appendicular skeleton and has minimal effects on longitudinal bone growth under normal physiological conditions.

IGF-1 actions in bone tissue are crucial for neonatal and early postnatal bone growth and cannot be compensated for by increased serum IGF-1 levels early in development.

IGF-1 but not IGF-2 is critical for BMD acquisition during postnatal and pubertal growth.

Given that the GHR and the IGF-1R pathways in bone cells are intact, elevated serum IGF-1 can fully compensate for a postnatal absence of tissue IGF-1, both morphologically and mechanically, during puberty and adulthood.

Elevated serum IGF-1 cannot compensate for the absence of tissue GHR action due to; 1) total inactivation of IGF-1-independent effects of GH in bone (mostly at the growth plate), 2) compromised serum IGF-1 delivery into bone, and 3) reduced GH-mediated IGF-1 expression in bone.

Reductions in serum IGF-1 during postnatal growth compromise peak bone acquisition, while reductions in serum IGF-1 during aging impair skeletal integrity, suggesting the endocrine IGF-1 plays an import role in achieving and maintaining cortical bone mass and skeletal integrity.

Elevated serum IGF-1 levels cannot compensate bone loss in the absence of tissue IGF-1 during aging.

Skeletal growth pre-puberty is regulated largely by autocrine/paracrine IGF-1, while postnatal skeletal-growth and acquisition of BMD are regulated by GH (largely via IGF-1-dependent mechanisms, but also via IGF-1-independent effects of GH).

GH regulates linear bone growth via its direct actions on the resting cells/pre-chondrocytes in the growth plate and the perichondrial ossification Groove of Ranvier. GH drives resting chondrocytes to start to differentiate and, at the same time, stimulates local production of IGF-1 leading to clonal expansion of proliferative chondrocytes via autocrine/paracrine mechanisms.

IGF-1 actions in in trabecular bone control matrix deposition and mineralization.

Excess of GH or IGF-1 in osteoblasts stimulates both bone formation and bone resorption.

GH/IGF-1 actions in mature osteoblast/osteocytes determine radial bone growth and are crucial for maintaining normal trabecular bone volume (independent of serum IGF-1 levels).

Osteocyte-derived IGF-1 is involved in the early response to mechanical loading, likely interacting with other pathways to induce anabolic outcomes.