Abstract

Human exposure to trans-cinnamic aldehyde [t-CA; cinnamaldehyde; cinnamal; (E)-3-phenylprop-2-enal] is common through diet and through the use of cinnamon powder for diabetes and to provide flavor and scent in commercial products. We evaluated the likelihood of t-CA to influence metabolism by inhibition of P450 enzymes. IC50 values from recombinant enzymes indicated that an interaction is most probable for CYP2A6 (IC50 = 6.1 µM). t-CA was 10.5-fold more selective for human CYP2A6 than for CYP2E1; IC50 values for P450s 1A2, 2B6, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4 were 15.8-fold higher or more. t-CA is a type I ligand for CYP2A6 (KS = 14.9 µM). Inhibition of CYP2A6 by t-CA was metabolism-dependent; inhibition required NADPH and increased with time. Glutathione lessened the extent of inhibition modestly and statistically significantly. The carbon monoxide binding spectrum was dramatically diminished after exposure to NADPH and t-CA, suggesting degradation of the heme or CYP2A6 apoprotein. Using a static model and mechanism-based inhibition parameters (KI = 18.0 µM; kinact = 0.056 minute−1), changes in the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) for nicotine and letrozole were predicted in the presence of t-CA (0.1 and 1 µM). The AUC fold-change ranged from 1.1 to 3.6. In summary, t-CA is a potential source of pharmacokinetic variability for CYP2A6 substrates due to metabolism-dependent inhibition, especially in scenarios when exposure to t-CA is elevated due to high dietary exposure, or when cinnamon is used as a treatment of specific disease states (e.g., diabetes).

Introduction

Dietary and herbal agents can profoundly impact the nature of drug response. Consequently, drug-diet/drug-herbal interactions are an important consideration for the effective use of medications. Modulation of drug metabolism by diet/herbs can significantly alter drug clearance, resulting in toxicity or reduced efficacy. For example, grapefruit juice inhibits the metabolism of terfenadine, elevating concentrations that ultimately affect cardiac rhythm (Benton et al., 1996). Other examples include leafy green vegetables with warfarin (O'Reilly and Rytand, 1980; Suttie et al., 1988), St. John’s wort with CYP3A substrates (Borrelli and Izzo, 2009), and tyramine-containing foods with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Blackwell et al., 1967; Flockhart, 2012).

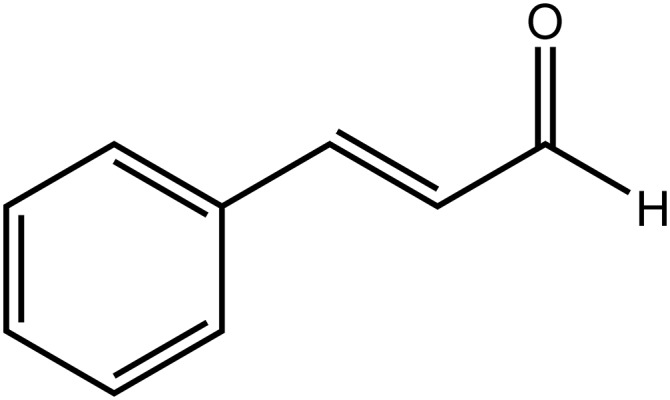

Phenylpropanoids are a major class of plant secondary metabolites with diverse functions (Yu and Jez, 2008). Due to their ubiquity, phenylpropanoids are a potential cause of drug-diet interactions. There are several low-molecular-weight phenylpropanoids present in cinnamon, most notably trans-cinnamic aldehyde (t-CA) (Fig. 1), which contributes to cinnamon’s flavor and aroma and is the major component of cinnamon oil. Human exposure to t-CA is common due to routine use in fragrances and food (Peters and Caldwell, 1994). The concentration of t-CA in commercial cinnamon powder ranges from 8.2 to 27.5 mg per gram (Friedman et al., 2000). Doses from 1 to 10 g of encapsulated cinnamon powder are used for diabetes mellitus to lower blood sugar (Pham et al., 2007; Crawford, 2009; Akilen et al., 2010), corresponding, therefore, to exposure of 8 to 275 mg of t-CA (Friedman et al., 2000; Kirkham et al., 2009). There are also reports of cinnamon exhibiting antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, lipid-lowering, anticancer, and amyloid plaque-reducing effects (George et al., 2013; Long et al., 2015). The growing use of cinnamon as a complementary treatment, in addition to dietary exposure, increases the likelihood of drug interactions with t-CA.

Fig. 1.

t-Cinnamic aldehyde (cinnamaldehyde).

Metabolism by CYP2A6 is a major clearance route for nicotine (Nakajima et al., 1996; Messina et al., 1997) and letrozole (Desta et al., 2009, 2011; Murai et al., 2009), an aromatase inhibitor used to treat breast cancer. CYP2A6 exhibits extensive genetic diversity (http://www.cypalleles.ki.se/cyp2a6.htm). With letrozole, CYP2A6 genetic variation contributes to as large as 12-fold differences in steady-state plasma concentrations in postmenopausal breast cancer patients (Desta et al., 2011). For nicotine, variations in metabolism contribute to differences in smoking behavior, including smoking cessation rates (Rao et al., 2000; Ariyoshi et al., 2002; Minematsu et al., 2003; Fujieda et al., 2004; Iwahashi et al., 2004; Schoedel et al., 2004; Ray et al., 2009; Chenoweth et al., 2013, 2015). However, nicotine addiction is a complex disease, and genetics alone does not fully explain interindividual differences in smoking addiction/cessation (Berrettini and Doyle, 2012; Bergen et al., 2013). Similarly, there are unaccounted factors that contribute to the noteworthy variability in letrozole pharmacokinetics (Desta et al., 2011). A potential contributor to the variation in metabolism and drug response is modulation of CYP2A6 activity by dietary and herbal substances. However, unlike drugs, which undergo thorough analysis for risk of drug-drug interactions (Food and Drug Administration, 2012), most herbal or dietary agents have not undergone such an intense level of scrutiny. Thus, there is a substantial knowledge gap regarding the risk of drug-herb and drug-diet interactions (Brantley et al., 2014a,b).

Given the abundant chemical diversity in herbs and the human diet, there are still many unknowns about the extent to which herbs/food affect CYP2A6 activity. Previously, isoflavones (Nakajima et al., 2006), menthol (MacDougall et al., 2003; Kramlinger et al., 2012), menthofuran (Khojasteh-Bakht et al., 1998), isothiocyanates (Nakajima et al., 2001; von Weymarn et al., 2007), and several others (Di et al., 2009) were studied and found to inhibit CYP2A6. Based on the structural and biophysical studies of CYP2A6, low-molecular-weight phenylpropanoids, such as t-CA (Fig. 1), are reasonable candidates as CYP2A6 inhibitors, since structural evidence indicates that the active site volume of CYP2A6 is more restricted (Yano et al., 2005) and “less flexible” (Wilderman et al., 2013) than other cytochrome P450s (P450s). The goals of this study were to investigate inhibition of CYP2A6 by t-CA, evaluate selectivity in comparison with other drug-metabolizing P450s, and assess the likelihood of drug interactions with t-CA by estimating changes in nicotine and letrozole area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) using a model that accounts for mechanism-based inhibition, variability in the fraction metabolized by CYP2A6, and intrinsic degradation rates of CYP2A6 (Mayhew et al., 2000; Venkatakrishnan and Obach, 2007; Grimm et al., 2009; Mohutsky and Hall, 2014).

Materials and Methods

Materials.

CYP2A6 Supersomes (with P450 reductase and cytochrome b5), human liver microsomes (50-donor pool), and P450 High Throughput Screening Kits were obtained from Corning Gentest (Woburn, MA). The human liver microsomes included male (53%) and female (47%) donors with an age distribution of 19–77. Glutathione, coumarin, 7-hydroxycoumarin, methoxylamine hydrochloride, methoxypsoralen, ketoconazole, letrozole, 1-aminobenzotriazole, trans-cinnamic aldehyde, and chlorzoxazone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). NADPH tetrasodium salt, 6-hydroxychlorzoxazone, and 4,4′-methanol-bisbenzonitrile were purchased from EMD Chemicals (San Diego, CA), U.S. Biologicals (Marblehead, MA), and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX), respectively.

Inhibition of Major Xenobiotic-Metabolizing P450s by t-CA.

Fluorescent assays were used to evaluate the selectivity of t-CA for CYP2A6 and many of the major drug-metabolizing human P450s. Corning Gentest P450 High Throughput Screening Kits were used to measure t-CA inhibition of CYP2A6, CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 essentially according to the manufacturer’s directions. All assays used P450 Supersomes with P450 reductase (and cytochrome b5 for CYP2A6, 2B6, 2C9, 2C19, and 3A4) and an NADPH-regenerating system. The substrates were 3 µM coumarin (CYP2A6), 1 µM 7-ethoxyresorufin (CYP1A2), 2.5 µM 7-ethoxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (CYP2B6), 75 µM 7-methoxy-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin (CYP2C9), 25 µM 3-cyano-7-ethoxycoumarin (CYP2C19), 1.5 µM 3-[2-(N,N-diethyl-N-methylamino)ethyl]-7-methoxy-4-methylcoumarin (CYP2D6), and 50 µM 7-benzyloxy-trifluoromethylcoumarin (CYP3A4). t-CA stocks were prepared in acetonitrile in accordance with the manufacturer’s directions. The final concentration of acetonitrile in assays was 0.05%. Positive control inhibitors were 1-aminobenzotriazole (CYP1A2), tranylcypromine (CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and CYP2C19), sulfaphenazole (CYP2C9), quinidine (CYP2D6), and ketoconazole (CYP3A4). Assays were conducted in 96-well plates, and the fluorescent intensity was measured using a Synergy2 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Each experiment was conducted in triplicate on at least three different days (i.e., at least three trials; N ≥ 9). The mean IC50 was determined from taking the antilog of the mean of the logIC50 values for the trials. The mean of the logIC50 values from the trials was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) to generate the 95% confidence intervals displayed in Table 1. The logIC50 value for CYP2A6 was compared with each logIC50 value for the other P450 isoforms using a t test (two-tailed; unequal variance) to evaluate the probability that differences in logIC50 values were due to coincidence.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition of xenobiotic-metabolizing P450 isoforms by t-CA

IC50 values are the mean of at least three experiments conducted on separate days. Values in parenthesis represent the 95% confidence interval (lower limit–upper limit).

| P450 Isoform | IC50 | N | Fold Difference Compared with CYP2A6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| µM | |||

| 2A6 | 6.1*** (2.9–12.7) | 15 | — |

| 1A2 | 106.3 (68.5–164.8) | 12 | 17.4 |

| 2B6 | 107.3 (88.3–130.3) | 12 | 17.6 |

| 2C9 | 96.2 (57.0–162.5) | 9 | 15.8 |

| 2C19 | 212.8(132.7–349.2) | 9 | 34.9 |

| 2D6 | > 2000a | 9 | Not determined |

| 2E1 | 64.0 (56.9–71.9) | 8 | 10.5 |

| 3A4 | 116.1 (51.1–263.0) | 9 | 19.0 |

Fifty percent inhibition was only observed at concentrations ≥2000 µM; the IC50 for quinidine (positive control) was <1 µM (N = 9).

P < 0.001 in the comparison of logIC50 for CYP2A6 to logIC50 for CYP1A2, 2B6, 2C9, 2C19, 2E1, and 3A4.

CYP2E1 activity was measured using the formation of 6-hydroxychlorzoxazone as previously reported, with modification (Peter et al., 1990; Elbarbry et al., 2007). Incubation mixtures consisted of 60 µM chlorzoxazone, 0.1 µM CYP2E1 Supersomes with cytochrome b5, and 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a final volume of 150 µl. After a preincubation period of 3 minutes at 37°C, the reaction was started by addition of NADPH (final concentration = 1 mM) and incubated at 37°C for 9 minutes in a shaking water bath. The reaction was terminated by addition of trichloroacetic acid (6 µl), followed by the addition of 7-hydroxycoumarin (internal standard). The supernatant was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), as described later. Each experiment was conducted in duplicate over four different days (N = 8). Standard curves for 6-hydroxychlorzoxazone were generated from serially diluted standards suspended in incubation buffer, 0.1 µM CYP2E1 Supersomes, trichloroacetic acid, chlorzoxazone (60 µM), and NADPH (1 mM) that were processed similar to experimental samples, except that trichloroacetic acid was added prior to NADPH. The mean IC50 value, variability, 95% confidence interval, and statistical comparison with the CYP2A6 IC50 value were determined by the same method as described earlier for the other P450 isoforms. Experiments were conducted in microcentrifuge tubes.

IC50 Measurement for Inhibition of 7-Hydroxycoumarin Formation by t-CA in Human Liver Microsomes.

Human liver microsomes (50-donor pool; 0.2 mg/ml), coumarin (3 μM), incubation buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate; pH = 7.4), and t-CA (0–500 μM; dissolved in incubation buffer) were preincubated for 5 minutes at 37°C in a shaking water bath. Following the addition of NADPH (1 mM), the samples (100 μl) were heated at 37°C for 6 minutes, terminated with 4 µl of trichloroacetic acid, mixed with a vortex mixer, and centrifuged at 11,000 rpm (11,228g) for 5 minutes in a 5415D centrifuge (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The concentration of 7-hydroxycoumarin in the supernatant was measured by HPLC-fluorescence as described later. Stock solutions of coumarin were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide and diluted in incubation buffer prior to experiments. The final concentration of dimethylsulfoxide in incubations was 0.25% (v/v). Standard curves were generated by serial dilution of 7-hydroxycoumarin in incubation buffer for quantification. Experiments were conducted in microcentrifuge tubes.

NADPH- and Time-Dependent Inhibition of 7-Hydroxycoumarin Formation with Recombinant CYP2A6 and Human Liver Microsomes.

CYP2A6 Supersomes (0.2 μM) or human liver microsomes (50-donor pool; 2 mg/ml) were preincubated for 5 minutes at 37°C in incubation buffer. Select samples contained t-CA (0–120 μM), NADPH (1 mM), glutathione (5 mM), and methoxylamine (1 mM) or a combination thereof. Incubations were initiated by addition of NADPH and heated at 37°C. At specific time points (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 minutes), 20-µl aliquots were removed from the primary incubation and diluted to 200 µl in a secondary incubation containing buffer, coumarin (3 µM), and NADPH (1 mM). The concentration of CYP2A6 or microsomal protein in the secondary incubation was 0.02 µM and 0.2 mg/ml, respectively. After heating at 37°C for 5.5 minutes, the incubations were terminated with 8 µl of trichloroacetic acid, mixed with a vortex mixer, and centrifuged at 11,288g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was analyzed by HPLC-fluorescence, as described later. Preliminary experiments conducted under the same conditions as the secondary incubations showed 7-hydroxycoumarin formation was linear to at least 14 and 18 minutes in recombinant and microsomal systems, respectively. Product formation was also within the linear range as a function of protein concentration for both systems. All experiments were conducted in microcentrifuge tubes. The percentage of remaining activity was determined by comparing to control samples that did not contain NADPH and t-CA in the primary incubation.

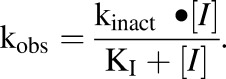

KI and kinact values were determined using nonlinear regression via GraphPad Prism 5 and eq. 1 (Silverman, 1988):

|

(1) |

The partition ratio for t-CA inhibition of CYP2A6 was determined from recombinant CYP2A6 (i.e., Supersomes). The percentage of remaining activity was graphed versus the molar ratio of t-CA to CYP2A6. The partition ratio was estimated from the intersection point of the two lines generated from linear regression of the low and high molar ratio regions of the graph (Silverman, 1988; Ghanbari et al., 2006).

NADPH- and Time-Dependent Inhibition of Letrozole Metabolism in Human Liver Microsomes.

Human liver microsomes (50-donor pool; 7.5 mg/ml) were preincubated in a total volume of 250 µl for 5 minutes at 37°C in buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH = 7.4). Select samples also contained NADPH (1 mM) and t-CA (8 and 80 µM) or a combination thereof; stocks were prepared in incubation buffer. At 9 minutes, 30-µl aliquots were removed from the primary incubation, diluted to 300 µl in incubation buffer containing letrozole (0.5 µM) and NADPH (1 mM), and incubated for an additional 30 minutes at 37°C. Incubations were terminated with trichloroacetic acid (12 µl) and centrifuged at 11,228g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was removed and transferred to a vial for HPLC analysis. 4,4′-Methanol-bisbenzonitrile formation was linear for at least 90 minutes as a function of time, and linear up to 1 mg/ml as a function of microsomal protein concentration in the secondary incubation. Standard curves for 4,4′-methanol-bisbenzonitrile were generated from serially diluted standards suspended in incubation buffer, human liver microsomes (0.75 mg/ml), trichloroacetic acid (12 µl), letrozole (0.5 µM), and NADPH (1 mM) that were processed similar to experimental samples, except that trichloroacetic acid was added prior to NADPH. The percentage of remaining activity was determined by comparing to control samples that did not contain NADPH and t-CA in the primary incubation.

Effect of Methoxylamine on NADPH-Dependent Inhibition of Letrozole Metabolism with Recombinant CYP2A6 and Human Liver Microsomes.

CYP2A6 Supersomes (0.5 μM) were preincubated for 5 minutes at 37°C in incubation buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH = 7.4). Select samples contained t-CA (80 μM), NADPH (1 mM), and methoxylamine (1 mM) or a combination thereof. Incubations were initiated by addition of NADPH and heated at 37°C. Aliquots (40 μL) were removed from the primary incubation, after incubating for 18 minutes, and diluted to 200 µl in a secondary incubation containing buffer, letrozole (0.5 µM), and NADPH (1 mM). The concentration of CYP2A6 the secondary incubation was 0.1 µM. After heating at 37°C for 72 minutes, the incubations were terminated with 8 µl of trichloroacetic acid, mixed with a vortex mixer, and centrifuged at 11,288g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was analyzed by HPLC-fluorescence, as described later. Preliminary experiments conducted under the same conditions as the secondary incubations showed metabolite (4,4′-methanol-bisbenzonitrile) formation was linear to at least 120 minutes. The experiments were conducted in microcentrifuge tubes.

For microsomal studies, human liver microsomes (50-donor pool; 7.5 mg/ml) were preincubated for 5 minutes at 37°C in incubation buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH = 7.4). Select samples contained t-CA (80 μM), NADPH (1 mM), and methoxylamine (1 mM) or a combination thereof. Incubations were initiated by addition of NADPH and heated at 37°C. Aliquots (30 μL) were removed from the primary incubation, after incubating for 18 minutes, and diluted to 300 µl in a secondary incubation containing buffer, letrozole (0.5 µM), and NADPH (1 mM). The protein concentration in the secondary incubation was 0.75 mg/ml. After heating at 37°C for 30 minutes, the incubations were terminated with 12 µl of trichloroacetic acid, mixed with a vortex mixer, and centrifuged at 11,288g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was analyzed by HPLC-fluorescence, as described later. Preliminary experiments, as described earlier for the NADPH/time-dependent experiment, showed metabolite formation in the secondary incubations was in the linear range with respect to time and protein concentration. All experiments were conducted in microcentrifuge tubes.

HPLC Analysis of 6-Hydroxychlorzoxazone, 7-Hydroxycoumarin, and 4,4′-methanol-bisbenzonitrile.

The metabolites were quantified with a Prominence HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), which included the following: two LC-20AD pumps, degasser, autosampler, column oven, communication bus module, diode array detector, and fluorescence detector. For 6-hydroxychlorzoxazone, chromatographic separation was carried out on a reversed-phase C18 column (150 × 4.6-mm i.d., 3.5-μm particle size; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) that was kept at 40°C based on a previously reported method (Elbarbry et al., 2007). 6-Hydroxychlorzoxazone, 7-hydroxycoumarin (internal standard), and chlorzoxazone were eluted under isocratic conditions at retention times of 3.5, 5, and 15 minutes, respectively, using a mobile phase composed of acetonitrile and 0.25% acetic acid (20:80 v/v) with a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Peaks were detected by absorbance at 287 nm (bandwidth = 4 nm); 7-hydroxycoumarin was also detected by fluorescence (excitation = 370 nm; emission = 450 nm). To quantify coumarin hydroxylase activity, the supernatant (25 µl) from incubations with coumarin was injected onto a Gemini column (100 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). 7-Hydroxycoumarin was eluted with 35% acetonitrile (flow rate = 0.6 ml/min) and detected by fluorescence. Analysis of 4,4′-methanol-bisbenzonitrile, as an indicator of letrozole metabolism, was based on a method reported previously with some modifications (Marfil et al., 1996). Supernatant (100 μL) was injected onto a Phenomenex Kinetix C18 column (100 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) using a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC (10 mM potassium phosphate, pH = 2.1 with 25% acetonitrile; 1.3 ml/min). 4,4′-Methanol-bisbenzonitrile and letrozole were detected by fluorescence (excitation = 230 nm; emission = 295 nm); a representative HPLC trace is available (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Spectral Binding Studies with t-CA and Purified CYP2A6.

CYP2A6 was expressed and purified as previously reported, with some slight modifications (Stephens et al., 2012). Spectral ligand binding assays were conducted using modified recombinant human CYP2A6, which had an N-terminal transmembrane sequence truncation (∆2–23) and a C-terminal His4-tag. The recombinant protein was expressed from pKK2A6dH (gift from Emily Scott, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS) in TOPP3 or DH5α Escherichia coli with a 48- or 72-hour induction time in δ-amino levulinic acid–supplemented Terrific Broth media. The protein was purified using Ni affinity chromatography, followed by carboxymethyl sepharose cation-exchange chromatography (Stephens et al., 2012). P450 content was determined from the carbon monoxide difference spectrum (Omura and Sato, 1962, 1964; Guengerich et al., 2009).

For the ligand binding titrations, samples of 1 µM purified CYP2A6, in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), were titrated with aliquots of t-CA dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer. Difference spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu UV-1601 spectrophotometer, and the difference in absorbance between the minimum and maximum, ∆A, was measured. Equilibrium dissociation constants were determined from nonlinear least-squares fits to the equation for one-site specific ligand binding using GraphPad Prism 5.

CYP2A6 Carbon Monoxide Binding Spectra in the Presence of t-CA and NADPH.

CO binding assays were conducted using modified recombinant human CYP2A6, which had an N-terminal transmembrane sequence truncation (∆2–23) and a C-terminal His4-tag, as described earlier. Rat P450 reductase was expressed and purified as previously reported (Shen et al., 1989). CYP2A6 and rat P450 reductase were combined in a 1:4 ratio (final sample concentrations 0.4 and 1.6 µM, respectively) and left at room temperature for 10 minutes. Following the addition of buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), NADPH (1 mM) and/or t-CA (80 µM) samples were incubated for 18 minutes at 37°C, and then CO-binding spectra were acquired using established methods (Omura and Sato, 1962, 1964; Guengerich et al., 2009).

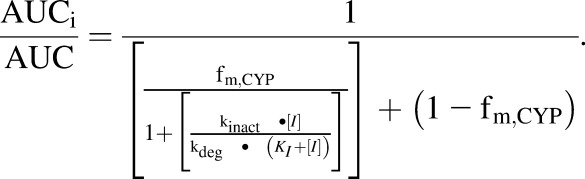

Prediction of t-CA–Mediated Changes in Nicotine and Letrozole AUC.

To estimate the potential for interactions between t-CA and CYP2A6 drug substrates, a model (eq. 2) was selected that takes into account mechanism-based inhibition (MBI) parameters (KI and kinact), the fraction of the dose metabolized by CYP2A6 (fm), and the in vivo degradation rate of CYP2A6 (kdeg) (Mayhew et al., 2000; Venkatakrishnan and Obach, 2007; Grimm et al., 2009; Mohutsky and Hall, 2014). AUCi and AUC refer to the AUC in the presence and absence of inhibitor, respectively:

|

(2) |

Nicotine and letrozole were selected because CYP2A6 metabolism has been reported as a primary route of elimination for both. The magnitude of kdeg can vary; low and high values from the literature were used to estimate the potential variation in t-CA–induced AUC changes. The in vivo half-life (t1/2) for CYP2A6 ranges from 19 to 37 hours (Renwick et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2008). Values of kdeg were determined from the relationship kdeg = 0.693/t1/2, generating kdeg values of 0.00031–0.00061 minute−1. High and low values for fm were selected to account for genetic variability in CYP2A6 activity. For nicotine, the fm values were based on a pharmacogenetic study that evaluated the fm of high (fm = 0.77) and intermediate (fm = 0.60) metabolizers, which was consistent with previous observations that 70–80% of a nicotine dose is metabolized to cotinine (Benowitz and Jacob, 1994), with CYP2A6 responsible for 90% of this pathway. For letrozole, a high fm of 0.80 was selected, based on reports that at least 85% of a letrozole dose is eliminated by P450-mediated metabolism, with CYP2A6 being the enzyme responsible for approximately 93% of metabolism at therapeutic letrozole concentrations. The low fm of 0.31 was selected based on in vitro studies of letrozole metabolism involving microsomes with reduced CYP2A6 activity (Sioufi et al., 1997; Murai et al., 2009; Desta et al., 2011).

Based on our literature searches, the systemic t-CA concentration in human blood following oral administration has yet to be reported. To estimate the blood concentrations of t-CA that could be expected for humans upon oral dosing, a body surface area normalization method (Food and Drug Administration, 2005; Reagan-Shaw et al., 2008) was used. The method utilizes an animal dose and accounts for differences in body weight and body surface area between species to estimate a human dose. A 250-mg/kg dose of t-CA in rats was used for the estimation; this dose resulted in blood concentrations on the order of 1 µg/ml (≈ 7.6 µM) in rats (Yuan et al., 1992).

Statistical Analysis.

The t test (paired; two-tailed distribution) was used to evaluate the probability that differences between mean values were due to coincidence.

Results

Inhibition of Major Xenobiotic-Metabolizing P450s by t-CA.

The selectivity of t-CA was evaluated by measuring inhibition of the major drug-metabolizing P450s using recombinant enzymes. IC50 values for t-CA inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 are shown in Table 1. The IC50 value for CYP2A6 (6.1 µM) was 10.5-fold lower than the next-lowest IC50, which was for CYP2E1. IC50 values for all other P450s were 15.8-fold higher or more than the IC50 value for CYP2A6. Substantial inhibition of CYP2D6 was not observed except at the highest concentrations of t-CA used in the study (e.g., 95% activity was observed at 666 µM t-CA). Based on these results, t-CA was evaluated further for inhibition of coumarin hydroxylase activity in human liver microsomes, resulting in an IC50 of 14.2 ± 1.1 µM (mean ± standard deviation) and a 95% confidence interval of 7.6–26.6 µM (from two trials conducted in triplicate; N = 6).

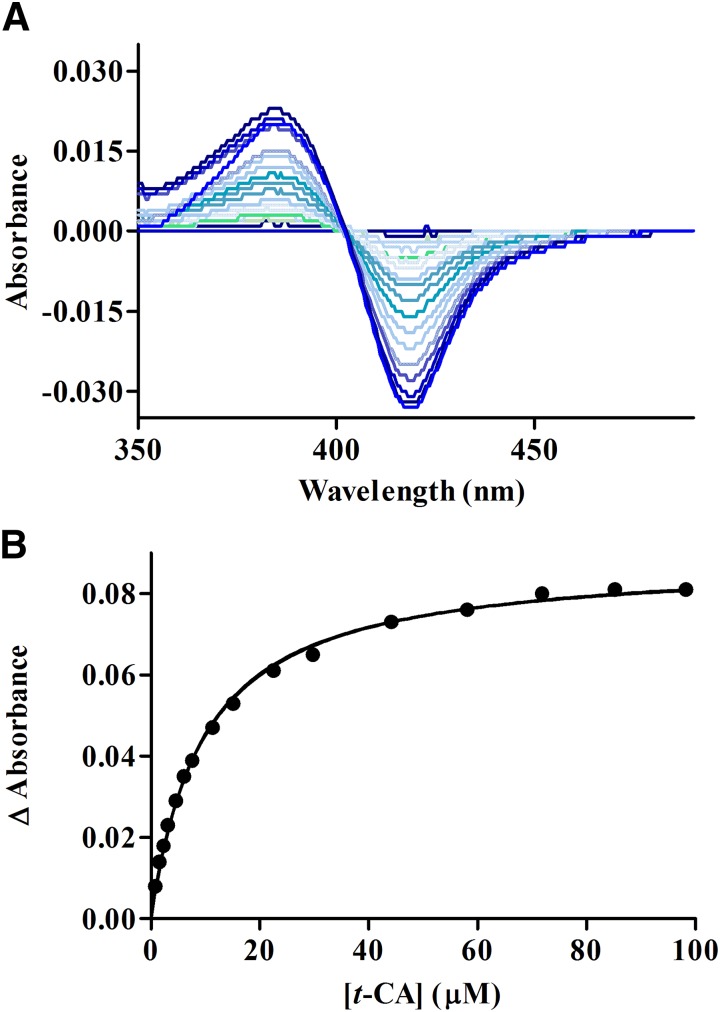

Spectral Analysis of t-Cinnamic Aldehyde Binding to Human CYP2A6.

Spectral binding studies were conducted with recombinant CYP2A6 to evaluate the binding affinity between t-CA and CYP2A6. The spectra indicated that t-CA is a type I ligand of CYP2A6, consistent with a compound deficient in sp2 hybridized nitrogen atoms. As shown in Fig. 2, fitting the spectral data from seven experiments to a one-site ligand binding model generated a KS = 14.9 ± 6.6 µM (N = 7).

Fig. 2.

(A) A representative binding spectra of purified rCYP2A6 with increasing concentrations of t-CA. (B) A representative curve generated from fitting changes in absorbance (A386 nm–A418 nm) to a one-site ligand binding model as a function of t-CA concentration.

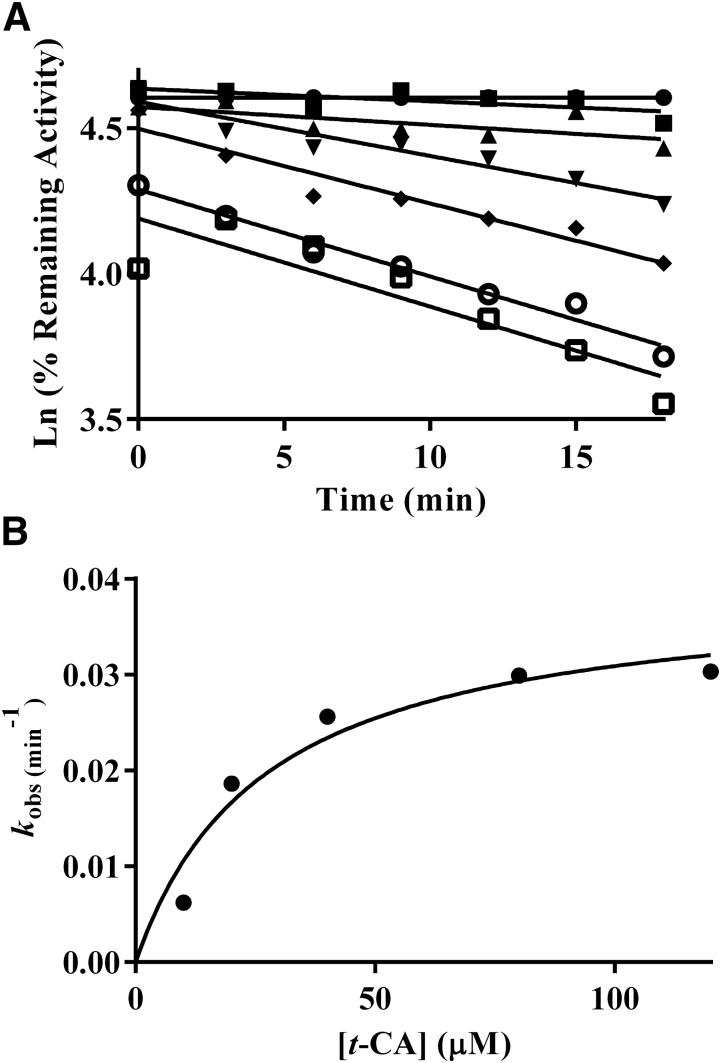

Mechanism-Based Inhibition of CYP2A6-Mediated Coumarin Hydroxylation by t-CA.

Mechanism-based inactivation was evaluated in two systems: recombinant CYP2A6 with cytochrome P450 reductase and cytochrome b5 (Fig. 3) and human liver microsomes (Fig. 4). In both systems, inhibition was time- and NADPH-dependent (Table 2). The mechanism-based inhibition parameters generated from fitting kobs and t-CA concentration to eq. 1 using nonlinear regression were KI = 27.2 µM and kinact = 0.039 minute−1 in recombinant CYP2A6 (rCYP2A6), and KI = 18.0 µM and kinact = 0.056 minute−1 in human liver microsomes. The partition ratio for rCYP2A6 was 2600 (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

(A) Inactivation of coumarin hydroxylase activity as a function of t-CA concentration, preincubation period, and NADPH in a recombinant CYP2A6 system (●, buffer; ▪, NADPH; ▴, 10 µM t-CA; ▾, 20 µM t-CA; ♦, 40 µM t-CA; ○, 80 µM t-CA; □, 120 µM t-CA). Data points are the mean of three individual experiments conducted on separate days (N = 3 for each point). The percentage of control activity was determined by comparing the activity to the average activity of samples with CYP2A6 that did not contain NADPH or t-CA. (B) Determination of kinact and KI by fitting kobs (min−1) to eq. 1.

Fig. 4.

(A) Inactivation of coumarin hydroxylase activity as a function of t-CA concentration, preincubation period, and NADPH in human liver microsomes (●, buffer; ▪, NADPH; ▴, 10 µM t-CA; ▾, 20 µM t-CA; ♦, 40 µM t-CA; ○, 80 µM t-CA; □, 120 µM t-CA). Each point is the mean of three individual experiments conducted on separate days (N = 3 for each point). The percentage of control activity was determined by comparing the activity to the average activity of samples with human liver microsomes that did not contain NADPH or t-CA. (B) Determination of kinact and KI by fitting kobs (min−1) to eq. 1.

TABLE 2.

Coumarin hydroxylase activity following an 18-minute preincubation in rCYP2A6 and human liver microsomes

Data points are the mean ± standard deviation of individual experiments conducted on three separate days (N = 3). Control activity (i.e., samples that did not contain NADPH or t-CA) for rCYP2A6 = 6.1 ± 0.4 pmol/min/pmol; control activity in human liver microsomes = 879 ± 55 pmol/mg protein/min.

| Percentage of Control Activity |

||

|---|---|---|

| Preincubation Components | rCYP2A6 | HLM |

| rCYP2A6 or HLM | 100 | 100 |

| + NADPH | 91.6 ± 3.5 | 75.8 ± 2.8*** |

| + 80 µM t-CA | 79.8 ± 3.4** | 82.2 ± 10.9** |

| + NADPH + 10 µM t-CA | 84.1 ± 4.2** | 73.4 ± 3.5*** |

| + NADPH + 20 µM t-CA | 69.3 ± 10.8*** | 60.8 ± 5.8*** |

| + NADPH + 40 µM t-CA | 56.6 ± 3.9*** | 48.2 ± 6.8*** |

| + NADPH + 80 µM t-CA | 41.1 ± 3.5*** | 33.3 ± 2.0*** |

| + NADPH + 120 µM t-CA | 34.9 ± 3.4*** | 29.1 ± 5.3*** |

HLM, human liver microsomes.

P < 0.01 in comparison with controls without NADPH and t-CA; ***P < 0.001 in comparison with controls without NADPH and t-CA.

Inhibition of CYP2A6-Mediated Letrozole Metabolism by t-CA.

Since substrate-dependent inhibition is often observed with the xenobiotic-metabolizing P450s (VandenBrink et al., 2012), a second substrate was selected to evaluate NADPH-dependent inhibition of CYP2A6 by t-CA. Similar to observations with coumarin hydroxylase activity, formation of 4,4′-methanol-bisbenzonitrile from letrozole was inhibited by t-CA in human liver microsomes, and this effect was concentration-dependent (Table 3). Inhibition was greatest in the presence of both NADPH and t-CA, supportive of mechanism-based inhibition, as well as a competitive component, based on the activity loss with t-CA in the absence of NADPH.

TABLE 3.

4,4′-Methanol-bisbenzonitrile formation from letrozole following a 9-minute preincubation in human liver microsomes (HLM)

Data points are the mean ± standard deviation of individual experiments conducted on two separate days (N = 6; control activity = 0.74 ± 31 pmol/mg protein/min). Percentage of control activity was determined by comparing the activity to samples with HLM that did not contain NADPH or t-CA.

| Preincubation Components |

Percentage of Control Activity |

|---|---|

| HLM | 100 |

| + NADPH | 80.8 ± 9.9** |

| + NADPH + 8 µM t-CA | 79.2 ± 5.3** |

| + 80 µM t-CA | 70.9 ± 4.8*** |

| + NADPH + 80 µM t-CA | 51.9 ± 6.9*** |

P < 0.01 in comparison with controls without NADPH and t-CA; ***P < 0.001 in comparison with controls without NADPH and t-CA.

Impact of Nucleophilic Trapping Agents on CYP2A6 Inhibition by t-CA.

The effect of glutathione and methoxylamine on CYP2A6 inhibition by t-CA was conducted to evaluate whether the reactive metabolite formed from t-CA disassociated from the enzyme (Table 4). Also, differences between the two traps can provide indicators of the chemical nature of the inhibitor, as glutathione and methoxylamine are “soft” and “hard” nucleophiles, respectively. For example, methoxylamine reacts with aldehydes to generate stable adducts via Schiff base formation, and glutathione is more likely to react via conjugate addition at the β carbon of an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl (Coles, 1984–1985; Prakash et al., 2008; Lopachin et al., 2012). Glutathione (5 mM) moderately prevented CYP2A6 inactivation of coumarin hydroxylase activity; the effect was statistically significant. However, controls (without t-CA) were still substantially more active than the glutathione-containing samples (43 and 29% greater for the recombinant and microsomal systems, respectively). Attempts were made to detect glutathione and N-acetyl cysteine conjugates from incubations with rCYP2A6 and t-CA using tandem mass spectrometry and scanning for neutral loss; no conjugates were identified following 60-minute incubations containing CYP2A6 (20 pmol), t-CA (20 µM), and the respective trapping agent (data not shown). Unexpectedly, the addition of methoxylamine with t-CA enhanced inhibition compared with t-CA alone, so a second substrate was evaluated. Methoxylamine had a similar effect on letrozole metabolism. Also, methoxylamine inhibited CYP2A6 in the absence of t-CA. Methoxylamine-containing samples exhibited 28.2 ± 7.1% coumarin hydroxylase activity (5.6 ± 1.4 pmol/min/pmol) compared with control activity (20.0 ± 4.0 pmol/min/pmol; three individual experiments conducted in triplicate; N = 9; p < 0.000001).

TABLE 4.

Effect of nucleophilic trapping agents, glutathione or methoxylamine, on the inhibition of CYP2A6 by t-CA in microsomal and recombinant systems

Data points are the mean ± standard deviation of individual experiments conducted on three separate days (N = 3 and 9) or two separate days (N = 6). The value of N is shown in parentheses.

| Percentage of Remaining Activity |

||

|---|---|---|

| Substrate/Trapping Agent | rCYP2A6 | HLM |

| Coumarin (80 µM t-CA) | ||

| None | 41.1 ± 3.5 (3)a | 31.7 ± 1.9 (6)b |

| Glutathione (5 mM) | 57.4 ± 9.5 (3)** | 67.5 ± 10.9 (6)*** |

| Methoxylamine (1 mM) | 0.8 ± 0.2 (9)*** | 9.5 ± 1.5 (9)*** |

| Letrozole (80 µM t-CA) | ||

| None | 48.9 ± 17.2 (9)c | 70.8 ± 5.0 (9)d |

| Methoxylamine (1 mM) | 8.2 ± 13.9 (9)*** | 45.0 ± 16.0 (9)*** |

HLM, human liver microsomes.

Control activity = 5.7 pmol/min/pmol P450.

Control activity = 924.0 ± 49.9 pmol/min/mg protein.

Control activity = 0.62 ± 0.04 pmol/min/nmol P450.

Control activity = 0.30 ± 0.03 pmol/min/mg protein.

P < 0.01 in comparison with samples without trapping agent (i.e., with t-CA and NADPH); ***P < 0.001 in comparison with samples without trapping agent (i.e., with t-CA and NADPH).

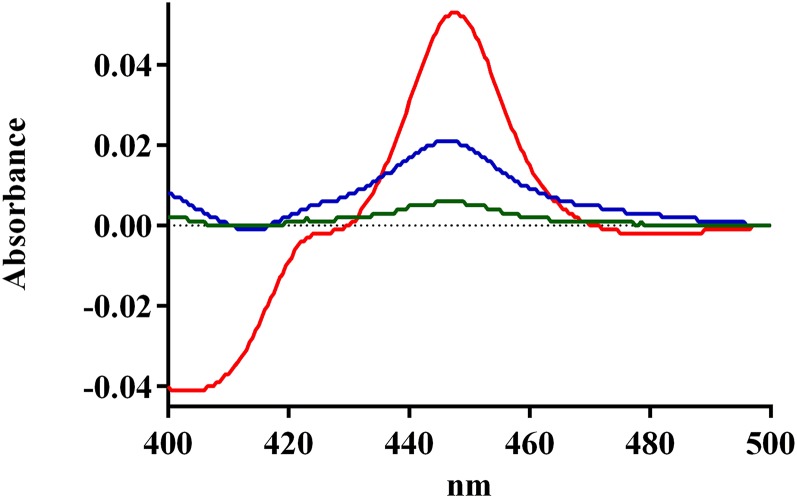

Effect of t-CA and NADPH on CYP2A6 CO-Binding Spectra.

The CO-binding spectrum was measured using a reconstituted system to investigate how the metabolism of t-CA impacts the level of functional CYP2A6 (Fig. 5). The intensity of CO-binding spectra from incubations containing both t-CA and NADPH (A448–A490 = 0.004; A448–A490 = absorbance at 448 nm minus absorbance at 490 nm) was diminished to 8.5% of the intensity of spectra from incubations with t-CA and no NADPH (A448–A490 = 0.047). NADPH in the absence of t-CA also diminished the peak intensity of the CO-binding spectrum, but to a lesser degree (A448–A490 = 0.018), analogous to observations from the activity assays (Tables 2 and 3). The effect of NADPH alone was greater in the reconstituted system, likely due to decreased protein stability, as compared with the more lipophilic environment present in microsomes.

Fig. 5.

Effect of t-CA and NADPH on CYP2A6 CO-binding spectra: 2A6 with t-CA (red line), 2A6 with NADPH (blue line), and 2A6 with t-CA and NADPH (green line).

Prediction of t-CA–Mediated Changes in Nicotine and Letrozole AUC.

The potential for a drug–t-CA interaction with CYP2A6 substrates was estimated with a mechanistic model (Mayhew et al., 2000; Venkatakrishnan and Obach, 2007; Grimm et al., 2009; Mohutsky and Hall, 2014) that accounts for MBI parameters (KI and kinact), the fraction of the dose metabolized (fm), and the in vivo degradation rate of CYP2A6 (kdeg) (Yang et al., 2008). High and low values of both kdeg and fm were used to estimate the range of possible AUC changes.

Estimated changes in AUC for nicotine and letrozole in the presence of unbound t-CA are shown in Tables 5 and 6. A 1.6-fold change was predicted for both nicotine and letrozole in the presence of unbound 0.1 µM t-CA, and this increased to 3.3- and 3.7-fold, respectively, at unbound 1 µM t-CA. Based on our literature search, the systemic t-CA concentration in human blood following oral administration has yet to be reported. In rats, a dose of 250 mg/kg t-CA generated blood concentrations on the order of ≈7.6 µM (1 µg/ml) (Yuan et al., 1992). Using these data and the body surface area normalization method (Food and Drug Administration, 2005; Reagan-Shaw et al., 2008), the human equivalent dose to generate a similar blood concentration was estimated to be 40.5 mg/kg or 2430 mg of t-CA per day for a 60-kg human. t-CA doses of 32 and 320 mg per day were estimated to achieve concentrations of 0.1 and 1 µM in humans.

TABLE 5.

Prediction of AUC changes for nicotine in the presence of increasing concentrations of t-CA

Predictions are based on mechanism-based inhibition parameters determined in human liver microsomes.

| AUC Fold Increase |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| fm | kdeg = 0.00061 min−1 (t1/2 = 19 hours) | kdeg = 0.00031 min−1 (t1/2 = 37 hours) | Range |

| 0.01 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.77 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 1.03–1.08 |

| 0.60 | 1.03 | 1.06 | |

| 0.1 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.77 | 1.35 | 1.62 | 1.25–1.62 |

| 0.60 | 1.25 | 1.43 | |

| 1 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.77 | 2.77 | 3.29 | 1.99–3.29 |

| 0.60 | 1.99 | 2.19 | |

| 10 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.77 | 3.96 | 4.14 | 2.39–4.14 |

| 0.60 | 2.39 | 2.44 | |

| 100 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.77 | 4.17 | 4.25 | 2.45–4.25 |

| 0.60 | 2.45 | 2.48 | |

TABLE 6.

Prediction of AUC changes for letrozole in the presence of increasing concentrations of t-CA

Predictions are based on mechanism-based inhibition parameters determined in human liver microsomes.

| AUC Fold Increase |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| fm | kdeg = 0.00061 min−1 (t1/2 = 19 hours) | kdeg = 0.00031 min−1 (t1/2 = 37 hours) | Range |

| 0.01 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.80 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 1.01–1.08 |

| 0.31 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

| 0.1 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.80 | 1.37 | 1.66 | 1.06–1.66 |

| 0.31 | 1.06 | 1.11 | |

| 1 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.80 | 2.97 | 3.61 | 1.27–3.61 |

| 0.31 | 1.27 | 1.34 | |

| 10 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.80 | 4.47 | 4.71 | 1.41–4.71 |

| 0.31 | 1.41 | 1.43 | |

| 100 µM [t-CA] | |||

| 0.80 | 4.76 | 4.87 | 1.44–4.87 |

| 0.31 | 1.44 | 1.45 | |

Discussion

Human exposure to t-CA is common due to its presence in the diet, fragrances, electronic cigarettes, and use as a complementary treatment of diabetes and other maladies (Friedman et al., 2000; Adams et al., 2004; Bickers et al., 2005; Crawford, 2009). From a toxicological perspective, it contains a well known structural alert (i.e., α,β-unsaturated carbonyl), reacts with skin proteins (Elahi et al., 2004), and is implicated in contact dermatitis (Seite-Bellezza et al., 1994). However, considering the presence of two electrophilic sites, the risk of toxicity upon oral administration is relatively low. For example, the no-observed-adverse-effect dose in chronic studies was 550 mg/kg per day, and oral LD50 values ranged from 1160 to 2200 mg/kg in studies of acute toxicity (Bickers et al., 2005). Differences in metabolic capacity and blood perfusion rates of skin versus liver likely contribute to toxicity being associated more often upon dermal exposure rather than oral administration. The characterization of t-CA metabolism upon oral administration has been reported in several species (Bickers et al., 2005). The major metabolic route involves oxidation to cinnamic acid, β-oxidation, and conjugation of the acid metabolites. Aldehyde dehydrogenase has been suggested as the enzyme responsible for the conversion to cinnamic acid (Bickers et al., 2005), but there are also many examples of P450-mediated metabolism of aldehydes (Raner et al., 1996; Amunom et al., 2007, 2011; Kaspera et al., 2012).

Information about the impact of t-CA on human P450 enzymes and the risk for P450-mediated drug–t-CA diet interactions is limited. Our results indicate a metabolism-mediated interaction with cinnamon or t-CA would be markedly more probable for CYP2A6 substrates than for drugs metabolized by the other P450 isoforms typically evaluated during drug discovery (Food and Drug Administration, 2012). Even though CYP2A6 and CYP2E1 exhibit overlap in substrate selectivity (Yoo et al., 1990; Yamazaki et al., 1992; Chen et al., 1998; Harrelson et al., 2007), t-CA was 10.5-fold more selective for CYP2A6. The IC50 values for other major drug-metabolizing P450s were at least 16-fold higher or more, and in some cases, substantially higher (i.e., 2D6 and 2C19).

The inhibitory mechanism is important in evaluating the likelihood of a metabolism-mediated interaction between a drug and a coadministered substance (Wienkers and Heath, 2005; Food and Drug Administration, 2012; Brantley et al., 2014a). Competitive/reversible inhibition was a minor contributor to CYP2A6 inhibition by t-CA. Time- and metabolism-dependent inhibition was a major contributor; this is notable because, even though an inhibitor may not appear to be potent as a reversible inhibitor, clinically relevant interactions can occur due to prolonged inactivation (Mohutsky and Hall, 2014). Time- and metabolism-dependent inhibition often falls into the category of MBI. MBI can involve metabolites coordinating to the heme iron and the formation of a metabolite-intermediate complex; alkyl amines or methylenedioxybenzene groups, which are not present in t-CA, are most often implicated in metabolite-intermediate complex formation. t-CA could also be bioactivated by CYP2A6 to a reactive metabolite (Fig. 6) that covalently binds to the enzyme. The presence of two electrophilic regions in t-CA suggests that direct covalent modification (i.e., metabolism independent) of CYP2A6 by t-CA is also a reasonable possibility.

Fig. 6.

Potential mechanisms for reactions of t-CA with CYP2A6. I. Direct reactions by conjugate addition with a cysteine residue of CYP2A6 (A) and reaction with a lysine residue (B) to form an imine (Schiff base). II. Reactions involving bioactivation of t-CA to form an uncharacterized reactive metabolite that reacts with and inactivates CYP2A6.

t-CA contains an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde and is susceptible to conjugate-addition reactions (also known as Michael addition) at the β carbon, or reactions with the carbonyl carbon of the aldehyde, via Schiff base formation (Prakash et al., 2008). Although CYP2A6 could be inactivated by direct reaction with one of the enzyme’s nucleophilic side chains and t-CA, the results from this study indicate that direct inactivation is not a major factor. Both NADPH and t-CA were required for potent inhibition of CYP2A6 in two different systems and independent of substrate identity. CO-binding experiments also support a metabolism-dependent mechanism where a greater than 90% decrease in CO-binding spectra, indicative of a loss of functional CYP2A6, was only observed in samples containing both t-CA and NADPH.

The results from experiments with glutathione support a metabolism-dependent mechanism for inactivation of CYP2A6, rather than reaction with a cysteine residue in CYP2A6 and the parent compound. A “soft” nucleophile, glutathione could be expected to react with the β carbon of t-CA in the absence of a bioactivation step, similar to a cysteine residue in CYP2A6; however, even high concentrations (5 mM) only had a modest effect. Notably, the concentration of t-CA used here was 12.5-fold lower than the concentration that reacts spontaneously with glutathione and the cytotoxic threshold concentration of t-CA (Swales and Caldwell, 1996).

The mechanism for CYP2A6 degradation, as indicated by the loss in CO-binding spectra, could occur through covalent binding of the metabolite to the apoprotein, to the heme prosthetic group, or destruction of the heme (Hollenberg et al., 2008). Several aldehydes, including the structural analog of t-CA, 3-phenylpropionaldehyde, are susceptible to P450-catalyzed reactions that result in heme modification by radical mechanisms (Raner et al., 1997; Kuo et al., 1999). The decrease in CO-binding spectra without a simultaneous increase in P420 absorption supports a mechanism where it is degradation of the heme rather than covalent modification of the apoprotein (Foti et al., 2011). Recently, evidence for a t-CA epoxide that forms cysteine adducts with a model hexapeptide was reported (Niklasson et al., 2014). The relevance of the epoxide metabolite to CYP2A6 inhibition is uncertain since the conditions used to generate adducts in that study were different than the more physiologically relevant conditions used here.

Other important considerations for predicting potential drug-drug/drug-herb interactions are the fraction of the “victim” drug metabolized by the inhibited enzyme (fm) and the concentration of the “perpetrator” at the site of inhibition (Brantley et al., 2014a). Due to challenges associated with accurately measuring the concentration of a perpetrator at the site of inhibition, a conservative approach is to use systemic plasma concentrations—that is, total concentration of free plus bound drug (Food and Drug Administration, 2012)—whereas unbound concentrations typically provide more accurate predictions (Grime and Riley, 2006). Presently, the availability of human pharmacokinetic data involving t-CA is unavailable. Thus, a range of concentrations was used for estimating AUC changes for CYP2A6 substrates. A 1.6-fold change was predicted for both nicotine and letrozole in the presence of 0.1 µM t-CA, and over 3.2-fold change at 1 µM t-CA. The guidance for drug interaction studies recommends an in vivo clinical study for AUC changes >1.25 (Food and Drug Administration, 2012).

A remaining question is whether humans are exposed to t-CA in sufficient quantities to generate meaningful changes in AUC for CYP2A6 substrates. Human pharmacokinetic data are not available for t-CA. The oral doses estimated here (32–320 mg) to achieve blood concentrations of 0.1–1 μM in humans are within the t-CA exposure range when cinnamon powder is used for diabetes, based on a method (Reagan-Shaw et al., 2008) to extrapolate pharmacokinetic data from rats (Yuan et al., 1992) to humans. The estimated range of exposure when cinnamon powder (1–10 g/day) is used for diabetes (Kirkham et al., 2009) is 8–275 mg of t-CA, based on the concentration of t-CA in cinnamon powder (Friedman et al., 2000). Considering dietary exposure, t-CA concentrations in cinnamon-containing foods range from 0.05 to 31.1 mg per 100 g. Based on these estimates, a diet high in t-CA could also represent a reasonable risk for CYP2A6 modulation. For example, 30 g of food (a mass corresponding to approximately a slice of bread) with high t-CA content is estimated to generate an exposure between 7 and 9 mg of t-CA (Friedman et al., 2000). Four to five servings of food containing high amounts of t-CA could achieve the 32-mg dose threshold necessary to generate a blood concentration of 0.1 μM.

In summary, t-CA selectively inhibits CYP2A6 by a metabolism-dependent mechanism that involves degradation of the functional enzyme. Substantial changes in AUC were predicted for nicotine and letrozole at low t-CA concentrations. A population more likely to experience a drug–t-CA interaction are individuals with diabetes who use cinnamon powder as an approach to lower blood sugar and who also smoke cigarettes or use nicotine replacement therapy, since CYP2A6 activity is known to modulate smoking behavior and cessation (described earlier). Similarly, the results suggest patients with diabetes who use cinnamon and are being treated with letrozole for breast cancer may be at risk for changes in letrozole metabolism that could lead to elevated letrozole plasma concentrations. Letrozole is typically dosed daily for several years, and although it is effective, many patients experience musculoskeletal effects that adversely influence medication adherence (Henry et al., 2012). The contribution of variable pharmacokinetics to these processes is an active area of research (Desta et al., 2011). Although the mechanisms are poorly understood, individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus have a greater risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer (Hardefeldt et al., 2012). Important next steps for determining the relevance and mechanism of the interaction between t-CA and CYP2A6 include determining the concentration of t-CA (total and unbound) in humans upon oral administration of t-CA and/or cinnamon powder, the influence of cytosolic enzymes on t-CA stability/potency, and further characterization of CYP2A6 degradation and t-CA metabolism by CYP2A6.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kara Ebisuya for assistance with the ligand binding studies, Dr. Michael Mohutsky for comments on the manuscript, and Dr. Emily Scott for the CYP2A6 plasmid.

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the concentration-time curve

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- MBI

mechanism-based inhibition

- P450

cytochrome P450

- rCYP2A6

recombinant CYP2A6

- t-CA

trans-cinnamic aldehyde

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Chan, Elbarbry, Harrelson.

Conducted experiments: Chan, Oshiro, Thomas, Higa, Black, Todorovic, Elbarbry, Harrelson.

Performed data analysis: Chan, Oshiro, Thomas, Higa, Black, Todorovic, Elbarbry, Harrelson.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Chan, Elbarbry, Harrelson.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon, the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust, the Pacific Research Institute for Science and Mathematics, and the Pacific University College of Health Professions and School of Pharmacy. The CYP2A6 plasmid, provided as a gift, was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant R01 GM076343].

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Adams TB, Cohen SM, Doull J, Feron VJ, Goodman JI, Marnett LJ, Munro IC, Portoghese PS, Smith RL, Waddell WJ, et al. (2004) The FEMA GRAS assessment of cinnamyl derivatives used as flavor ingredients. Food Chem Toxicol 42:157–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akilen R, Tsiami A, Devendra D, Robinson N. (2010) Glycated haemoglobin and blood pressure-lowering effect of cinnamon in multi-ethnic Type 2 diabetic patients in the UK: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Diabet Med 27:1159–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunom I, Dieter LJ, Tamasi V, Cai J, Conklin DJ, Srivastava S, Martin MV, Guengerich FP, Prough RA. (2011) Cytochromes P450 catalyze the reduction of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Chem Res Toxicol 24:1223–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunom I, Stephens LJ, Tamasi V, Cai J, Pierce WM, Jr, Conklin DJ, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava S, Martin MV, Guengerich FP, et al. (2007) Cytochromes P450 catalyze oxidation of alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes. Arch Biochem Biophys 464:187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyoshi N, Miyamoto M, Umetsu Y, Kunitoh H, Dosaka-Akita H, Sawamura Y, Yokota J, Nemoto N, Sato K, Kamataki T. (2002) Genetic polymorphism of CYP2A6 gene and tobacco-induced lung cancer risk in male smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11:890–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Jacob P., 3rd (1994) Metabolism of nicotine to cotinine studied by a dual stable isotope method. Clin Pharmacol Ther 56:483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton RE, Honig PK, Zamani K, Cantilena LR, Woosley RL. (1996) Grapefruit juice alters terfenadine pharmacokinetics, resulting in prolongation of repolarization on the electrocardiogram. Clin Pharmacol Ther 59:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen AW, Javitz HS, Krasnow R, Nishita D, Michel M, Conti DV, Liu J, Lee W, Edlund CK, Hall S, et al. (2013) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor variation and response to smoking cessation therapies. Pharmacogenet Genomics 23:94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini WH, Doyle GA. (2012) The CHRNA5-A3-B4 gene cluster in nicotine addiction. Mol Psychiatry 17:856–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickers D, Calow P, Greim H, Hanifin JM, Rogers AE, Saurat JH, Sipes IG, Smith RL, Tagami H, RIFM expert panel (2005) A toxicologic and dermatologic assessment of cinnamyl alcohol, cinnamaldehyde and cinnamic acid when used as fragrance ingredients. Food Chem Toxicol 43:799–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell B, Marley E, Price J, Taylor D. (1967) Hypertensive interactions between monoamine oxidase inhibitors and foodstuffs. Br J Psychiatry 113:349–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli F, Izzo AA. (2009) Herb-drug interactions with St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum): an update on clinical observations. AAPS J 11:710–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantley SJ, Argikar AA, Lin YS, Nagar S, Paine MF. (2014a) Herb-drug interactions: challenges and opportunities for improved predictions. Drug Metab Dispos 42:301–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantley SJ, Gufford BT, Dua R, Fediuk DJ, Graf TN, Scarlett YV, Frederick KS, Fisher MB, Oberlies NH, Paine MF. (2014b) Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling framework for quantitative prediction of an herb-drug interaction. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 3:e107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Koenigs LL, Thompson SJ, Peter RM, Rettie AE, Trager WF, Nelson SD. (1998) Oxidation of acetaminophen to its toxic quinone imine and nontoxic catechol metabolites by baculovirus-expressed and purified human cytochromes P450 2E1 and 2A6. Chem Res Toxicol 11:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth MJ, O’Loughlin J, Sylvestre MP, Tyndale RF. (2013) CYP2A6 slow nicotine metabolism is associated with increased quitting by adolescent smokers. Pharmacogenet Genomics 23:232–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth MJ, Schnoll RA, Novalen M, Hawk LW, Jr, George TP, Cinciripini PM, Lerman C, Tyndale RF. (2015) The nicotine metabolite ratio is associated with early smoking abstinence even after controlling for factors that influence the nicotine metabolite ratio. Nicotine Tob Res [published ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles B. (1984–1985) Effects of modifying structure on electrophilic reactions with biological nucleophiles. Drug Metab Rev 15:1307–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford P. (2009) Effectiveness of cinnamon for lowering hemoglobin A1C in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Board Fam Med 22:507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desta Z, Kreutz Y, Nguyen AT, Li L, Skaar T, Kamdem LK, Henry NL, Hayes DF, Storniolo AM, Stearns V, et al. (2011) Plasma letrozole concentrations in postmenopausal women with breast cancer are associated with CYP2A6 genetic variants, body mass index, and age. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90:693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desta Z, Tyndale R, Hoffman E, Kreutz Y, Nguyen A, Flockhart D. (2009) Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2A6 Genetic Variation Predicts Letrozole Plasma Concentrations in Postmenopausal Women with Breast Cancer. Cancer Res 69: 5160. [Google Scholar]

- Di YM, Chow VD, Yang LP, Zhou SF. (2009) Structure, function, regulation and polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2A6. Curr Drug Metab 10:754–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elahi EN, Wright Z, Hinselwood D, Hotchkiss SA, Basketter DA, Pease CK. (2004) Protein binding and metabolism influence the relative skin sensitization potential of cinnamic compounds. Chem Res Toxicol 17:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbarbry FA, McNamara PJ, Alcorn J. (2007) Ontogeny of hepatic CYP1A2 and CYP2E1 expression in rat. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 21:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flockhart DA. (2012) Dietary restrictions and drug interactions with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: an update. J Clin Psychiatry 73 (Suppl 1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration US (2005) Guidance for Industry: estimating the maximum safe starting dose in initial clinical trials for therapeutics in adult healthy volunteers, Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD.

- Food and Drug Administration (2012) Guidance for industry: drug interaction studies - study design, data analysis, implications for dosing, and labeling recommendations, Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Foti RS, Rock DA, Pearson JT, Wahlstrom JL, Wienkers LC. (2011) Mechanism-based inactivation of cytochrome P450 3A4 by mibefradil through heme destruction. Drug Metab Dispos 39:1188–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M, Kozukue N, Harden LA. (2000) Cinnamaldehyde content in foods determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem 48:5702–5709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujieda M, Yamazaki H, Saito T, Kiyotani K, Gyamfi MA, Sakurai M, Dosaka-Akita H, Sawamura Y, Yokota J, Kunitoh H, et al. (2004) Evaluation of CYP2A6 genetic polymorphisms as determinants of smoking behavior and tobacco-related lung cancer risk in male Japanese smokers. Carcinogenesis 25:2451–2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George RC, Lew J, Graves DJ. (2013) Interaction of cinnamaldehyde and epicatechin with tau: implications of beneficial effects in modulating Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Alzheimers Dis 36:21–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbari F, Rowland-Yeo K, Bloomer JC, Clarke SE, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Rostami-Hodjegan A. (2006) A critical evaluation of the experimental design of studies of mechanism based enzyme inhibition, with implications for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation. Curr Drug Metab 7:315–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grime K, Riley RJ. (2006) The impact of in vitro binding on in vitro-in vivo extrapolations, projections of metabolic clearance and clinical drug-drug interactions. Curr Drug Metab 7:251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm SW, Einolf HJ, Hall SD, He K, Lim HK, Ling KH, Lu C, Nomeir AA, Seibert E, Skordos KW, et al. (2009) The conduct of in vitro studies to address time-dependent inhibition of drug-metabolizing enzymes: a perspective of the pharmaceutical research and manufacturers of America. Drug Metab Dispos 37:1355–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich FP, Martin MV, Sohl CD, Cheng Q. (2009) Measurement of cytochrome P450 and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Nat Protoc 4:1245–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardefeldt PJ, Edirimanne S, Eslick GD. (2012) Diabetes increases the risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Endocr Relat Cancer 19:793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrelson JP, Henne KR, Alonso DO, Nelson SD. (2007) A comparison of substrate dynamics in human CYP2E1 and CYP2A6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 352:843–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry NL, Azzouz F, Desta Z, Li L, Nguyen AT, Lemler S, Hayden J, Tarpinian K, Yakim E, Flockhart DA, et al. (2012) Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:936–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg PF, Kent UM, Bumpus NN. (2008) Mechanism-based inactivation of human cytochromes p450s: experimental characterization, reactive intermediates, and clinical implications. Chem Res Toxicol 21:189–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahashi K, Waga C, Takimoto T. (2004) Whole deletion of CYP2A6 gene (CYP2A6AST;4C) and smoking behavior. Neuropsychobiology 49:101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspera R, Sahele T, Lakatos K, Totah RA. (2012) Cytochrome P450BM-3 reduces aldehydes to alcohols through a direct hydride transfer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 418:464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khojasteh-Bakht SC, Koenigs LL, Peter RM, Trager WF, Nelson SD. (1998) (R)-(+)-Menthofuran is a potent, mechanism-based inactivator of human liver cytochrome P450 2A6. Drug Metab Dispos 26:701–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham S, Akilen R, Sharma S, Tsiami A. (2009) The potential of cinnamon to reduce blood glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance. Diabetes Obes Metab 11:1100–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramlinger VM, von Weymarn LB, Murphy SE. (2012) Inhibition and inactivation of cytochrome P450 2A6 and cytochrome P450 2A13 by menthofuran, β-nicotyrine and menthol. Chem Biol Interact 197:87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CL, Raner GM, Vaz AD, Coon MJ. (1999) Discrete species of activated oxygen yield different cytochrome P450 heme adducts from aldehydes. Biochemistry 38:10511–10518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M, Tao S, Rojo de la Vega M, Jiang T, Wen Q, Park SL, Zhang DD, Wondrak GT. (2015) Nrf2-dependent suppression of azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium-induced colon carcinogenesis by the cinnamon-derived dietary factor cinnamaldehyde. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 8:444–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopachin RM, Gavin T, Decaprio A, Barber DS. (2012) Application of the Hard and Soft, Acids and Bases (HSAB) theory to toxicant--target interactions. Chem Res Toxicol 25:239–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall JM, Fandrick K, Zhang X, Serafin SV, Cashman JR. (2003) Inhibition of human liver microsomal (S)-nicotine oxidation by (-)-menthol and analogues. Chem Res Toxicol 16:988–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfil F, Pineau V, Sioufi A, Godbillon SJ. (1996) High-performance liquid chromatography of the aromatase inhibitor, letrozole, and its metabolite in biological fluids with automated liquid-solid extraction and fluorescence detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl 683:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew BS, Jones DR, Hall SD. (2000) An in vitro model for predicting in vivo inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 by metabolic intermediate complex formation. Drug Metab Dispos 28:1031–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina ES, Tyndale RF, Sellers EM. (1997) A major role for CYP2A6 in nicotine C-oxidation by human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282:1608–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minematsu N, Nakamura H, Iwata M, Tateno H, Nakajima T, Takahashi S, Fujishima S, Yamaguchi K. (2003) Association of CYP2A6 deletion polymorphism with smoking habit and development of pulmonary emphysema. Thorax 58:623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohutsky M, Hall SD. (2014) Irreversible enzyme inhibition kinetics and drug-drug interactions. Methods Mol Biol 1113:57–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai K, Yamazaki H, Nakagawa K, Kawai R, Kamataki T. (2009) Deactivation of anti-cancer drug letrozole to a carbinol metabolite by polymorphic cytochrome P450 2A6 in human liver microsomes. Xenobiotica 39:795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Itoh M, Yamanaka H, Fukami T, Tokudome S, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Yokoi T. (2006) Isoflavones inhibit nicotine C-oxidation catalyzed by human CYP2A6. J Clin Pharmacol 46:337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Yamamoto T, Nunoya K, Yokoi T, Nagashima K, Inoue K, Funae Y, Shimada N, Kamataki T, Kuroiwa Y. (1996) Role of human cytochrome P4502A6 in C-oxidation of nicotine. Drug Metab Dispos 24:1212–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Yoshida R, Shimada N, Yamazaki H, Yokoi T. (2001) Inhibition and inactivation of human cytochrome P450 isoforms by phenethyl isothiocyanate. Drug Metab Dispos 29:1110–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklasson IB, Ponting DJ, Luthman K, Karlberg AT. (2014) Bioactivation of cinnamic alcohol forms several strong skin sensitizers. Chem Res Toxicol 27:568–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T, Sato R. (1962) A new cytochrome in liver microsomes. J Biol Chem 237:1375–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T, Sato R. (1964) The Carbon Monoxide-Binding Pigment of Liver Microsomes. I. Evidence for Its Hemoprotein Nature. J Biol Chem 239:2370–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly RA, Rytand DA. (1980) “Resistance” to warfarin due to unrecognized vitamin K supplementation. N Engl J Med 303:160–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter R, Böcker R, Beaune PH, Iwasaki M, Guengerich FP, Yang CS. (1990) Hydroxylation of chlorzoxazone as a specific probe for human liver cytochrome P-450IIE1. Chem Res Toxicol 3:566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MM, Caldwell J. (1994) Studies on trans-cinnamaldehyde. 1. The influence of dose size and sex on its disposition in the rat and mouse. Food Chem Toxicol 32:869–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham AQ, Kourlas H, Pham DQ. (2007) Cinnamon supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacotherapy 27:595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash C, Sharma R, Gleave M, Nedderman A. (2008) In vitro screening techniques for reactive metabolites for minimizing bioactivation potential in drug discovery. Curr Drug Metab 9:952–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raner GM, Chiang EW, Vaz AD, Coon MJ. (1997) Mechanism-based inactivation of cytochrome P450 2B4 by aldehydes: relationship to aldehyde deformylation via a peroxyhemiacetal intermediate. Biochemistry 36:4895–4902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raner GM, Vaz AD, Coon MJ. (1996) Metabolism of all-trans, 9-cis, and 13-cis isomers of retinal by purified isozymes of microsomal cytochrome P450 and mechanism-based inhibition of retinoid oxidation by citral. Mol Pharmacol 49:515–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Y, Hoffmann E, Zia M, Bodin L, Zeman M, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. (2000) Duplications and defects in the CYP2A6 gene: identification, genotyping, and in vivo effects on smoking. Mol Pharmacol 58:747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Tyndale RF, Lerman C. (2009) Nicotine dependence pharmacogenetics: role of genetic variation in nicotine-metabolizing enzymes. J Neurogenet 23:252–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. (2008) Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J 22:659–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renwick AB, Watts PS, Edwards RJ, Barton PT, Guyonnet I, Price RJ, Tredger JM, Pelkonen O, Boobis AR, Lake BG. (2000) Differential maintenance of cytochrome P450 enzymes in cultured precision-cut human liver slices. Drug Metab Dispos 28:1202–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoedel KA, Hoffmann EB, Rao Y, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. (2004) Ethnic variation in CYP2A6 and association of genetically slow nicotine metabolism and smoking in adult Caucasians. Pharmacogenetics 14:615–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seite-Bellezza D, el Sayed F, Bazex J. (1994) Contact urticaria from cinnamic aldehyde and benzaldehyde in a confectioner. Contact Dermat 31:272–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen AL, Porter TD, Wilson TE, Kasper CB. (1989) Structural analysis of the FMN binding domain of NADPH-cytochrome P-450 oxidoreductase by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem 264:7584–7589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RB. (1988) Mechanism-based enzyme inactivation: chemistry and enzymology, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Sioufi A, Gauducheau N, Pineau V, Marfil F, Jaouen A, Cardot JM, Godbillon J, Czendlik C, Howald H, Pfister C, et al. (1997) Absolute bioavailability of letrozole in healthy postmenopausal women. Biopharm Drug Dispos 18:779–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens ES, Walsh AA, Scott EE. (2012) Evaluation of inhibition selectivity for human cytochrome P450 2A enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos 40:1797–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttie JW, Mummah-Schendel LL, Shah DV, Lyle BJ, Greger JL. (1988) Vitamin K deficiency from dietary vitamin K restriction in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 47:475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swales NJ, Caldwell J. (1996) Studies on trans-cinnamaldehyde II: Mechanisms of cytotoxicity in rat isolated hepatocytes. Toxicol In Vitro 10:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VandenBrink BM, Foti RS, Rock DA, Wienkers LC, Wahlstrom JL. (2012) Prediction of CYP2D6 drug interactions from in vitro data: evidence for substrate-dependent inhibition. Drug Metab Dispos 40:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatakrishnan K, Obach RS. (2007) Drug-drug interactions via mechanism-based cytochrome P450 inactivation: points to consider for risk assessment from in vitro data and clinical pharmacologic evaluation. Curr Drug Metab 8:449–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Weymarn LB, Chun JA, Knudsen GA, Hollenberg PF. (2007) Effects of eleven isothiocyanates on P450 2A6- and 2A13-catalyzed coumarin 7-hydroxylation. Chem Res Toxicol 20:1252–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienkers LC, Heath TG. (2005) Predicting in vivo drug interactions from in vitro drug discovery data. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4:825–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilderman PR, Shah MB, Jang HH, Stout CD, Halpert JR. (2013) Structural and thermodynamic basis of (+)-α-pinene binding to human cytochrome P450 2B6. J Am Chem Soc 135:10433–10440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Inui Y, Yun CH, Guengerich FP, Shimada T. (1992) Cytochrome P450 2E1 and 2A6 enzymes as major catalysts for metabolic activation of N-nitrosodialkylamines and tobacco-related nitrosamines in human liver microsomes. Carcinogenesis 13:1789–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Liao M, Shou M, Jamei M, Yeo KR, Tucker GT, Rostami-Hodjegan A. (2008) Cytochrome p450 turnover: regulation of synthesis and degradation, methods for determining rates, and implications for the prediction of drug interactions. Curr Drug Metab 9:384–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano JK, Hsu MH, Griffin KJ, Stout CD, Johnson EF. (2005) Structures of human microsomal cytochrome P450 2A6 complexed with coumarin and methoxsalen. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12:822–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo JS, Ishizaki H, Yang CS. (1990) Roles of cytochrome P450IIE1 in the dealkylation and denitrosation of N-nitrosodimethylamine and N-nitrosodiethylamine in rat liver microsomes. Carcinogenesis 11:2239–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu O, Jez JM. (2008) Nature's assembly line: biosynthesis of simple phenylpropanoids and polyketides. Plant J 54:750–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JH, Dieter MP, Bucher JR, Jameson CW. (1992) Toxicokinetics of cinnamaldehyde in F344 rats. Food Chem Toxicol 30:997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.