Abstract

The outgrowth of many neurons within the central nervous system is initially directed towards or away from the cells lying at the midline. Recent genetic evidence suggests that a simple model of differential sensitivity to the conserved Netrin attractants and Slit repellents is insufficient to explain the guidance of all axons at the midline. In the Drosophila embryonic ventral nerve cord, many axons still cross the midline in the absence of the Netrin genes (NetA and NetB) or their receptor frazzled. Here we show that mutation of mushroom body defect (mud) dramatically enhances the phenotype of Netrin or frazzled mutants, resulting in many more axons failing to cross the midline, although mutations in mud alone have little effect. This suggests that mud, which encodes a microtubule-binding coiled-coil protein homologous to NuMA and LIN-5, is an essential component of a Netrin-independent pathway that acts in parallel to promote midline crossing. We demonstrate that this novel role of Mud in axon guidance is independent of its previously described role in neural precursor development. These studies identify a parallel pathway controlling midline guidance in Drosophila and highlight a novel role for Mud potentially acting downstream of Frizzled to aid axon guidance.

KEY WORDS: Drosophila, Axon guidance, Midline, Mud, NuMA, LIN-5, Netrin

Summary: Mud/NuMA/LIN-5 is a signal transduction component, potentially acting downstream of Frizzled to mediate netrin-independent axon guidance towards the midline.

INTRODUCTION

In the central nervous system (CNS) of vertebrates and invertebrates most neurons extend across the midline to form commissures, while the remainder extend on their own side (Tear, 1999; Kaprielian et al., 2001; Garbe and Bashaw, 2004; Evans and Bashaw, 2010). This decision depends in part on the responsiveness of the growth cone to Netrin attractants and Slit repellents, both secreted from cells at the midline, although additional mechanisms also exist to direct axons across the midline (Andrews et al., 2008; Dickson and Zou, 2010; Evans and Bashaw, 2010; Spitzweck et al., 2010; Organisti et al., 2015).

The Netrins act as chemoattractants to bring axons to the midline in flies, worms and vertebrates. In all these organisms, Netrin loss-of-function causes defects in the projection of axons towards the midline (Hedgecock et al., 1990; Harris et al., 1996; Mitchell et al., 1996; Serafini et al., 1996), and the same is true of mutations in the Netrin receptors unc-40, DCC and frazzled (Hedgecock et al., 1990; Kolodziej et al., 1996; Fazeli et al., 1997). However, their activity does not fully account for the guidance of all commissural axons across the midline, suggesting the existence of additional mechanisms (Brankatschk and Dickson, 2006).

In Drosophila, a number of components of Netrin-independent mechanisms that attract axons to the midline have been identified. Removal of either Dscam, fmi (stan – FlyBase) or robo2 significantly enhances the failure of midline crossing caused by the absence of frazzled alone (Andrews et al., 2008; Spitzweck et al., 2010; Organisti et al., 2015). However, the loss of any of these genes individually does not lead to a significant midline guidance defect. Thus, the role of these additional pathways in directing commissural axons across the midline is only revealed in the absence of Netrin signalling.

Here we show that Mushroom body defect (Mud) also has a role in a Netrin-independent signalling pathway directing commissural axons to the midline in Drosophila. Mud has previously been identified to function within neuroblasts and sensory organ precursors to couple the orientation of the mitotic spindle to both intrinsic and extrinsic cues (Bowman et al., 2006; Izumi et al., 2006; Siller et al., 2006; Siller and Doe, 2009; Segalen et al., 2010). We show that its role in axon outgrowth is independent of its activity within neuroblasts. Mud is expressed within postmitotic neurons, where it may act downstream of Frizzled to influence intrinsic neuronal polarity necessary for axonal outgrowth.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Netrin deficiencies reveal the presence of an additional activity mediating axon guidance across the midline

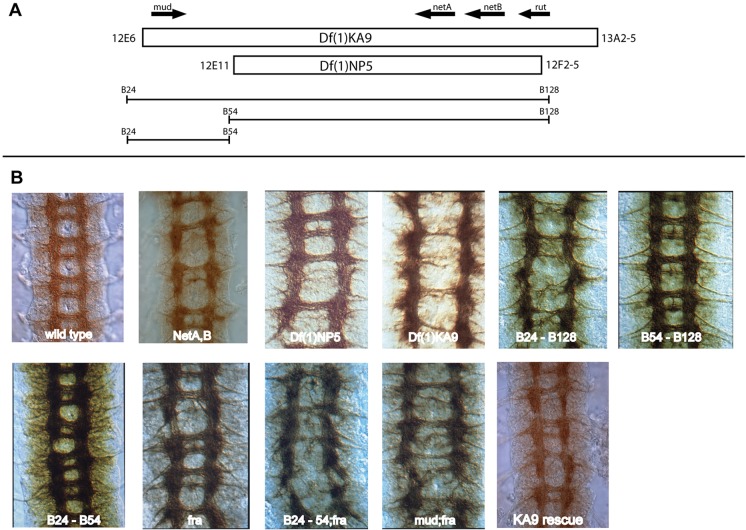

Drosophila has two Netrin genes, NetA and NetB, which are adjacent on the X chromosome (Fig. 1A). The original studies investigating the role of the Drosophila Netrins reported a difference in phenotype between a small deficiency Df(1)NP5 that removed both Netrin genes and a slightly larger deficiency, Df(1)KA9, that extends further than NP5 (Fig. 1A) (Harris et al., 1996; Mitchell et al., 1996). Embryos hemizygous for the smaller deficiency Df(1)NP5 have thinner or occasionally absent axon commissures in the ventral nerve cord, with the posterior commissure being more strongly affected, and occasional breaks in the longitudinal connectives (Fig. 1B, Table 1). This phenotype is similar to that seen in embryos where only NetA and NetB have been removed (Fig. 1B, Table 1) (Brankatschk and Dickson, 2006), although Df(1)NP5 is slightly more severe (Andrews et al., 2008). By contrast, embryos hemizygous for the slightly larger deficiency Df(1)KA9 exhibit a more severe phenotype, with a near complete loss of midline crossing in some commissures (Fig. 1B, Table 1). The larger deficiency affects the guidance of anterior and posterior commissural axons at the midline.

Fig. 1.

Identification of Mud as an additional axon guidance factor required for commissure formation in the Drosophila CNS. (A) Regions of the X chromosome deleted by the deficiencies Df(1)KA9 and Df(1)NP5 (boxes) used to remove the two Netrin genes NetA and NetB. Distal is to the left. Bracketed lines beneath represent the extents of the synthetic deficiencies used in this study that identify the location of an additional activity required for midline crossing distal to the Netrin genes. (B) Drosophila embryos immunostained with the CNS axon marker BP102. Anterior is up. In the wild-type embryo axon pathways extend in an orthogonal pattern with longitudinal tracts positioned either side of the midline and a pair of commissural tracts that connect the two sides of the nervous system within each segment. In embryos bearing double mutations for NetA and NetB commissure formation is disrupted, with fewer axons attracted across the midline, with the posterior commissure affected more severely. Embryos homozygous for a chromosomal deficiency, Df(1)NP5, that removes the Netrin genes have a phenotype similar to that of NetA,B animals, while the slightly larger deficiency Df(1)KA9 has a stronger BP102 phenotype with fewer axons attracted to the midline, suggesting that an additional activity has been removed. The synthetic deficiency Df(1)B24-B128 that is deficient for the Netrin genes and a distal region displays the stronger phenotype. Embryos deficient for the distal region alone, Df(1)B24-B54, display very little disruption to the axon pathways. Mutations that remove the attractive Netrin receptor frazzled (fra) have a similar phenotype to that of embryos lacking the Netrin genes. When loss of fra is combined with removal of the distal material in Df(1)B24-54;fra, this causes the increased midline crossing failure phenotype. mud is a candidate gene for the additional activity removed in Df(1)B24-54, and mud;fra double mutants display the same enhanced phenotype as Df(1)KA9 embryos. Reintroduction of mud as a transgene into Df(1)KA9 embryos reverts the midline phenotype to that seen when the Netrin genes are removed alone and also rescues the mild phenotype seen in mud mutant animals, confirming that mud encodes the additional midline attractive activity.

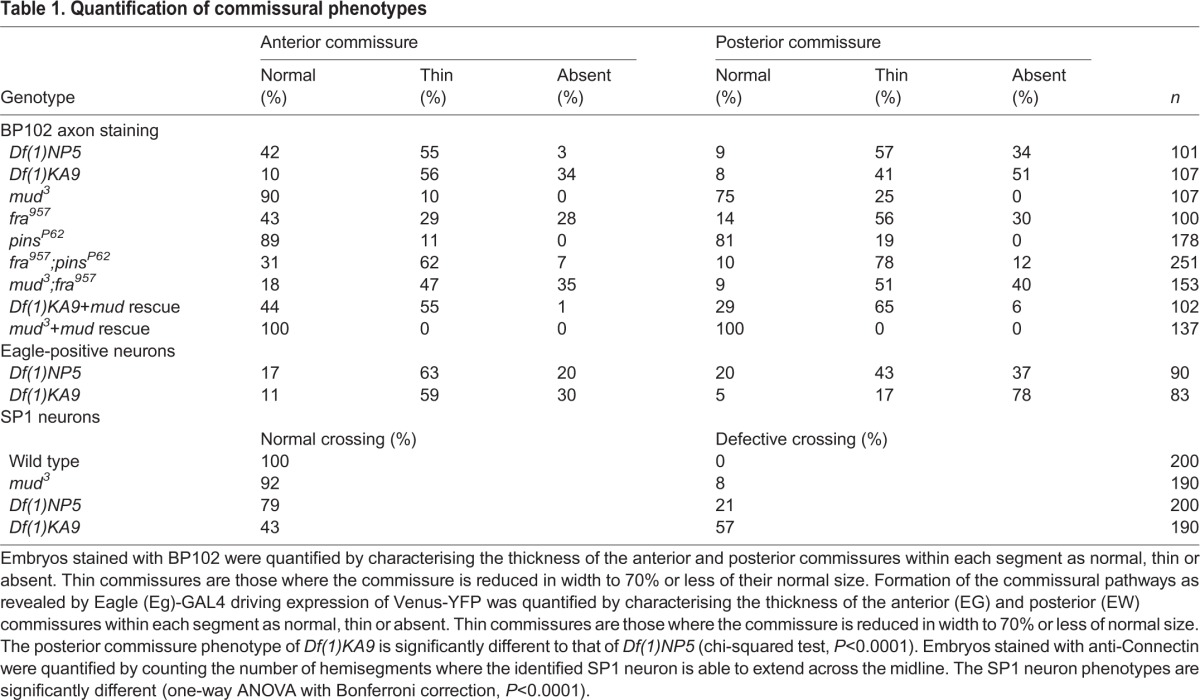

Table 1.

Quantification of commissural phenotypes

Restoration of either Netrin gene at the midline is sufficient to completely rescue the Df(1)NP5 phenotype, while rescuing the Df(1)KA9 to near wild type (Harris et al., 1996; Mitchell et al., 1996). These findings indicate the existence of a gene activity, also deleted in Df(1)KA9, that enhances midline crossing defects caused by the absence of the Netrins, but which has a mild phenotype when removed alone.

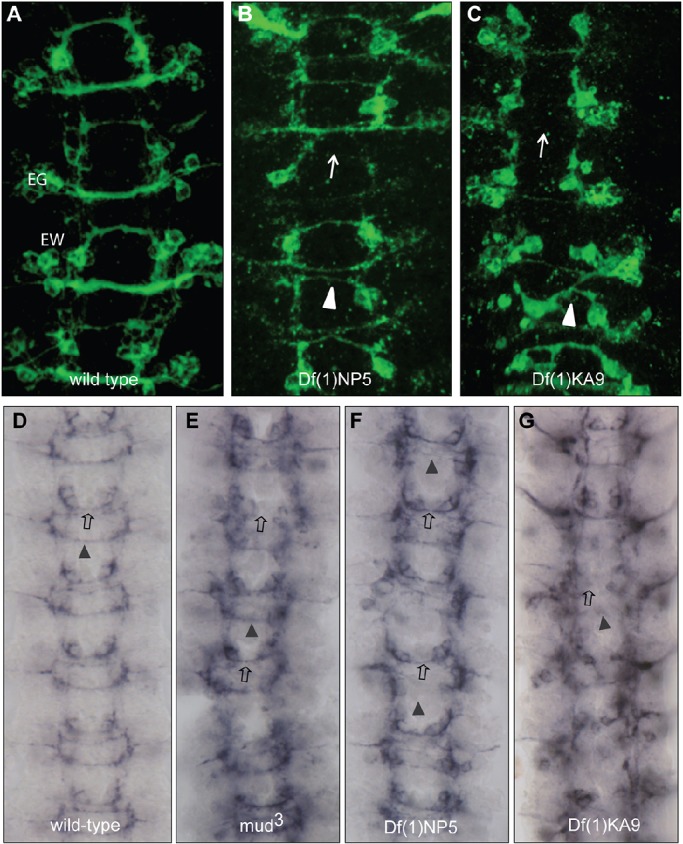

Markers for specific subsets of commissural neurons confirm the increased severity of commissural defects in Df(1)KA9 compared with Df(1)NP5 embryos (Table 1, Fig. 2). The Eg-GAL4 driver identifies the EG cluster of 10-12 cells that extend axons in the anterior commissure and the EW cluster of four cells that project in the posterior commissure (Higashijima et al., 1996; Dittrich et al., 1997; Garbe and Bashaw, 2007). Midline crossing by Eagle-positive EG and EW neurons is significantly more disrupted in Df(1)KA9 than in Df(1)NP5, due both to stalling of axons prior to midline crossing and to misguidance, where axons extend across the midline along an aberrant trajectory (Table 1, Fig. 2). In Df(1)NP5 embryos the EW axons fail to cross the midline in 37% of segments, while 20% of the EG axons do not cross. In Df(1)KA9 embryos the number of segments where EW axons fail to cross the midline is increased to 78% (Fig. 2). The outgrowth of the SP1 neuron, one of the earliest axons to cross the midline in the anterior commissure, was examined using anti-Connectin (Meadows et al., 1994). Behaviour of the SP1 neurons mirrors that of the EG axons, with significantly more failing to cross the midline in Df(1)KA9 (57%) compared with Df(1)NP5 (21%).

Fig. 2.

Loss of mud enhances axon outgrowth defects at the CNS midline in Netrin-deficient embryos. (A) Eagle-positive axons extend in the anterior (EG) and posterior (EW) commissures at the midline of the CNS. (B) Upon loss of Netrin signalling [Df(1)NP5] there is a reduction in the ability of Eagle-positive axons to cross the midline, leading to a thinning of commissures (arrowhead) or complete loss of midline crossing (arrow). (C) Loss of both Mud and Netrin activity [Df(1)KA9] results in a greater disruption of midline crossing, with many axons failing to cross in both anterior and posterior commissures (arrow) or taking aberrant trajectories (arrowhead). (D) Anti-Connectin reveals SP1 axons that extend in the anterior commissure (open arrow) and additional axons extending in the posterior commissure (arrowhead). (E) Loss of mud alone leads to mild defects, with 7% of segments showing failure of SP1 axons to cross. (F) Loss of Netrin signalling results in increased disruption, with axons failing to cross in both anterior (open arrow) and posterior (arrowhead) commissures. (G) Removal of both Mud and Netrin signalling leads to an enhanced phenotype in which midline crossing in the posterior commissure is severely affected and there is an increase in the failure of SP1 axons to cross the midline.

Mud is the enhancer of Netrins

We used overlapping synthetic deficiencies in the region (Livingstone, 1985) to map the enhancer activity (Fig. 1A). Df(1)B24-B128, which deletes both NetA and NetB plus distal material, displays the stronger axon guidance phenotype suggesting that the gene responsible lies distal to NetA. The synthetic deficiency Df(1)B24-B54 selectively removes this distal genetic material – which includes a candidate gene, mushroom body defect (mud), and a small number of additional genes – while leaving the Netrin genes intact. Embryos hemizygous for this deficiency display a subtle CNS axon pathway phenotype. There is a general but weak irregularity in the usually orthogonal organisation of axon tracts as revealed by BP102 staining, with occasionally thinner commissures and rare breaks in the longitudinals. This phenotype is indistinguishable from that observed in embryos hemizygous for any of several alleles of mud (Fig. 1B).

To test whether mud encodes the additional midline guidance activity removed in Df(1)KA9 we examined embryos double mutant for mud and frazzled (fra). fra embryos have a similar commissural axon guidance phenotype to small Netrin deficiencies (Fig. 1B) (Kolodziej et al., 1996). When mud alleles, or the small deficiency Df(1)B24-B54 that deletes the mud region, are combined with fra alleles the double-mutant embryos fail to form the majority of commissures – a phenotype indistinguishable from that of Df(1)KA9.

Confirmation that mud is necessary for the formation of the commissures that form in Df(1)NP5 embryos was demonstrated by reintroducing mud as a transgene into Df(1)KA9 embryos, using a BAC construct that contains the mud genomic region. This resulted in a rescue of the BP102 phenotype in Df(1)KA9 embryos to one resembling that of the smaller Df(1)NP5 deficiency (Fig. 1B). Thus, mud encodes the enhancer activity that accounts for the more severe phenotype observed in the larger Df(1)KA9 deficiency and is necessary to enable axons to cross the midline in this background. This places Mud as a component within an additional signalling pathway that directs axons to the midline, the role of which becomes apparent in the absence of Netrin signalling.

mud mutation has direct effects on axon extension and guidance

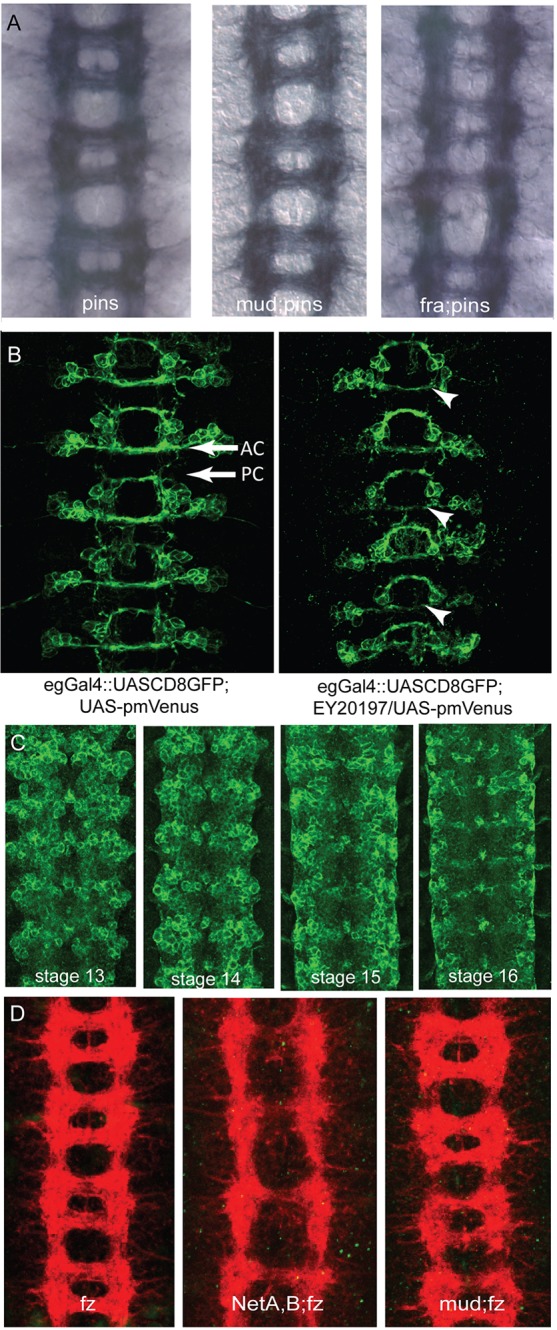

Mud has previously been shown to be required during the asymmetric division of embryonic neuroblasts, where it couples mitotic spindle orientation to cortical polarity at metaphase (Bowman et al., 2006; Izumi et al., 2006; Siller et al., 2006). Initial defects in this process in mud mutants are largely recovered by a realignment of the spindle during telophase, and only minor consequences have been reported on subsequent neuronal number and fate. The pattern of expression of Even-skipped is largely unchanged in mud mutants, Df(1)KA9 or Df(1)NP5 (Izumi et al., 2006) (data not shown). Similarly, the neurons identified by anti-Futsch (22C10) and anti-Fasciclin 2 (1D4) form as normal (data not shown), indicating little or no change in cell fate. To test further whether the roles of Mud during neuroblast division and axon outgrowth are separable, the ventral nerve cord phenotypes of fra;pins double mutants were examined. Pins functions with Mud in asymmetric neuroblast division (Siller et al., 2006) and if loss of mud during neuroblast division leads to defects in subsequent axon outgrowth, then a pins mutant should have a similar effect on axon guidance and would enhance fra phenotypes. However, the ventral nerve cord phenotype of fra;pins double mutants is no more severe than that of fra mutants alone (Fig. 3A). The effects on axon guidance due to the absence of Mud are thus not attributable to a disruption of cell fate.

Fig. 3.

Mud acts in neurons and its role in axon guidance is independent of Pins. (A) Mud has previously been identified to function in a Partner of inscuteable (Pins)-dependent pathway within neuroblasts. In common with the loss of mud, absence of pins does not lead to significant axon guidance deficits as revealed by the BP102 antibody. Embryos deficient for mud and pins also show no outgrowth defects. Absence of pins does not enhance the axon guidance defects associated with loss of fra, suggesting that Mud acts in a Pins-independent pathway to enhance the axon guidance defects caused by a loss of Netrin signalling. (B) Mud overexpression in Eagle-positive neurons causes a reduction of midline crossing by the EG neurons (arrowheads), which cross through the anterior commissure (AC), revealing that Mud can influence the guidance of neurons. PC, posterior commissure. (C) Venus-YFP-tagged Mud protein driven by the mud promoter is expressed widely within the CNS at stage 13 and becomes restricted to subsets of neurons and glia by stage 16. (D) Mud has been found to act downstream from Frizzled (Fz). Loss of fz has little impact on axon outgrowth at the midline as revealed by BP102, yet the double mutant NetA,B;fz is as severe as Df(1)KA9 or mud;fra. This suggests that Mud and Fz might act in the same pathway, which is supported by the fact that a mud;fz mutant phenotype resembles that of mud or fz single mutants.

We also examined the consequence of manipulating the levels of Mud activity within neuroblasts and neurons using the UAS-GAL4 system (Brand and Perrimon, 1993). We made use of a P-element insertion (EY20197) that inserts a UAS immediately upstream of mud. Increasing Mud expression in neuroblasts using the Sca-GAL4 driver did not result in axon outgrowth defects (data not shown). However, increasing Mud expression in Eagle-positive neurons caused a reduction in the number of axons extending across the midline through the anterior commissure (Fig. 3B) suggesting that Mud acts in a dose-dependent manner in axons. The decrease in axon number is not due to a loss of the cells. This disruption is consistent with a direct role of Mud in axonal projection or guidance in postmitotic neurons.

Mud is expressed in postmitotic neurons

Mud contains multiple coiled-coil domains and a microtubule-binding domain and shares similarity to the vertebrate protein NuMA (Numa1) and LIN-5 of C. elegans (Guan et al., 2000; Bowman et al., 2006; Izumi et al., 2006; Siller et al., 2006). The Drosophila gene encodes seven isoforms, and a probe that detects all isoforms shows that mud transcripts are expressed throughout embryonic development. Zygotic expression is restricted to the ventral nerve cord from stage 11 and mud remains expressed in the ventral nerve cord until the end of embryogenesis.

Mud protein expression has previously been described as localised to both the apical cortex and the centrosome of neuroblasts (Izumi et al., 2006). We find that Mud is also expressed within neurons, where it is localised within a punctate pattern within the soma. Mud is expressed in most, if not all, neurons and is also present within midline cells and members of the longitudinal glia (Fig. 3C). NuMA has similarly been reported to be expressed in a particulate distribution within the somatodendritic compartment of postmitotic sympathetic and hippocampal neurons, a distribution that requires intact microtubules (Ferhat et al., 1998). Mud, in common with its LIN-5 and NuMA homologues, is able to bind microtubules, has a conserved role in regulating mitotic spindle formation and is able to link intrinsic or extrinsic cues to orient spindle formation (Du et al., 2001; Segalen et al., 2010). Mud also has an ability to recruit dynein/dynactin (Siller and Doe, 2009) and functions in the planar cell polarity pathway (Segalen et al., 2010; Johnston et al., 2013), raising the possibility that Mud might function in neurons to link polarity information with the dynein/dynactin complex to orient microtubule structures within neurons to encourage directed outgrowth.

Commissure formation utilises a variety of partially redundant pathways

Multiple signalling pathways, in addition to Netrins, cooperate to direct axon outgrowth towards and across the midline. Mutations in the genes encoding the transmembrane proteins Dscam1, Robo2 and Fmi or the intracellular proteins Abl and Trio and now Mud can all dramatically enhance the reduction of axonal midline crossing in Netrin or fra mutants (Forsthoefel et al., 2005; Andrews et al., 2008; Spitzweck et al., 2010; Evans et al., 2015; Organisti et al., 2015).

Because Mud has previously been implicated in a signalling pathway downstream of Frizzled (Fz) in planar cell polarity (Segalen et al., 2010), we tested for genetic interactions between fz and Netrins and between fz and mud. We find, as recently independently reported (Organisti et al., 2015), that NetA,B;fz double mutants display a severe lack of commissures, similar to mud;fra or Df(1)KA9 mutants, whereas mud;fz mutants are not appreciably more severe than either mud or fz mutants alone (Fig. 3D). These data are consistent with a model whereby Fz and Mud both operate in a common, parallel pathway to the Netrins, possibly in concert with Fmi (Organisti et al., 2015). Double mutants of mud with Robo2 or with Dscam1 did not show a significant increase in midline crossing defects (data not shown), which formally suggests that Mud might also act in common pathways with these proteins, but this straightforward interpretation is complicated by the multiple functions demonstrated for Robo2 and Dscam1 in midline guidance (Andrews et al., 2008; Evans et al., 2015).

Further investigations are necessary to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms through which these multiple pathways are integrated within growth cones to enable the precise navigation of commissural axons at the midline.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetics

The following Drosophila stocks were used: (1) mud1/Fm7cβGal, (2) mud3/Fm7cβGal, (3) fra957/CyWglacZ, (4) Df-NP5/Fm7cβGal, (5) Df-KA9/Fm7cβGal, (6) NetA,B/Fm7βactin (courtesy of B. Dickson, IMP, Vienna), (7) fz1/Tm6bAbdAlacZ, (8) mud3/Fm7c;fra957/CyOwgβGal, (9) PinsP62/Tm6bAbdalacZ, (10) fra957/CyOwgβGal;PinsP62/Tm6bAbdalacZ, (11) mud3/Fm7cβGal;PinsP62/Tm6bAbdalacZ, (12) P{EPgy2}EY20197, (13) egGal4::UASCD8GFP, (14) elavGal4 on II, (15) egGal4, (16) Sca-GAL4, (17) mud3/Fm7kr::GFP and (18) fra957/CyODfdEYFP. X;Y translocation stocks with breakpoints in the 12E-13A region, originally constructed by Stewart and Merriam (1973), were used to generate deficiencies for defined regions of the X chromosome as described by Ashburner (1989). Unless otherwise stated, stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center.

Molecular biology

A genomic rescue construct for mud was created in P[acman] (Venken et al., 2006). 17.5 kb was retrieved from BAC CH322-147E14 (BACPAC Resources Center) (Venken et al., 2009) covering chromosome arm X from 14138384 to 14157868. The rescue construct includes the promoter region of mud, located 147 bp downstream of CG32599 to 1546 bp upstream of mud, the mud gene and region downstream to 363 bp upstream of the closest downstream gene, CG1461. 500 bp homology arms homologous to the left and right ends of the transgene were subcloned into P[acman] to create a targeting construct. MW005 cells [courtesy of Colin Dolphin, King's College, London; described in Westenberg et al. (2010)] were made competent for recombineering by inducing the Red recombinase essentially as described (Dolphin and Hope, 2006). After verification of the correct integration of genomic DNA into P[acman] by sequencing, transgenic flies containing this P[acman]-mud construct inserted into the VK6 attP site at 19E7 on the X chromosome were obtained by BestGene. A Venus-YFP tag was inserted at the N-terminus of Mud using Gibson assembly and the construct inserted at attP40 by BestGene.

Immunochemistry

Embryos were collected, fixed and stained as previously described by Patel (1994). The following primary antibodies were used: monoclonal antibody BP102 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; 1:20), mouse anti-β-Gal (Promega, Z3781; 1:300), mouse anti-Connectin [courtesy of Robert White, University of Cambridge, UK (Meadows et al., 1994); 1:20] and rabbit anti-GFP (ThermoFisher Scientific, A6455; 1:300). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Molecular Probes. Stacks of images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope and processed using Volocity 5.2 imaging software (Improvision).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Corey Goodman for support and mentorship of K.J.M. during early stages of the project. G.T. thanks Nancy Carvajal for technical support.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

M.-S.C. and K.J.M. contributed equally to the experimental work. S.G. and S.A. also contributed to the experimental work. T.R. contributed reagents. K.J.M. and G.T. conceived the experiments, obtained funding and prepared the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [BB/K002031 and BB/F014287/1]. Deposited in PMC for immediate release.

References

- Andrews G. L., Tanglao S., Farmer W. T., Morin S., Brotman S., Berberoglu M. A., Price H., Fernandez G. C., Mastick G. S., Charron F. et al. (2008). Dscam guides embryonic axons by Netrin-dependent and -independent functions. Development 135, 3839-3848. 10.1242/dev.023739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M. (1989). Drosophila: a Laboratory Handbook. New York: Cold Spring Habor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman S. K., Neumuller R. A., Novatchkova M., Du Q. and Knoblich J. A. (2006). The Drosophila NuMA Homolog Mud regulates spindle orientation in asymmetric cell division. Dev. Cell 10, 731-742. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. H. and Perrimon N. (1993). Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brankatschk M. and Dickson B. J. (2006). Netrins guide Drosophila commissural axons at short range. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 188-194. 10.1038/nn1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson B. J. and Zou Y. (2010). Navigating intermediate targets: the nervous system midline. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a002055 10.1101/cshperspect.a002055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich R., Bossing T., Gould A. P., Technau G. M. and Urban J. (1997). The differentiation of the serotonergic neurons in the Drosophila ventral nerve cord depends on the combined function of the zinc finger proteins Eagle and Huckebein. Development 124, 2515-2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin C. T. and Hope I. A. (2006). Caenorhabditis elegans reporter fusion genes generated by seamless modification of large genomic DNA clones. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e72 10.1093/nar/gkl352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q., Stukenberg P. T. and Macara I. G. (2001). A mammalian Partner of inscuteable binds NuMA and regulates mitotic spindle organization. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1069-1075. 10.1038/ncb1201-1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T. A. and Bashaw G. J. (2010). Axon guidance at the midline: of mice and flies. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20, 79-85. 10.1016/j.conb.2009.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T. A., Santiago C., Arbeille E. and Bashaw G. J. (2015). Robo2 acts in trans to inhibit Slit-Robo1 repulsion in pre-crossing commissural axons. Elife 4, e08407 10.7554/elife.08407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli A., Dickinson S. L., Hermiston M. L., Tighe R. V., Steen R. G., Small C. G., Stoeckli E. T., Keino-Masu K., Masu M., Rayburn H. et al. (1997). Phenotype of mice lacking functional Deleted in colorectal cancer (Dec) gene. Nature 386, 796-804. 10.1038/386796a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferhat L., Cook C., Kuriyama R. and Baas P. W. (1998). The nuclear/mitotic apparatus protein NuMA is a component of the somatodendritic microtubule arrays of the neuron. J. Neurocytol. 27, 887-899. 10.1023/A:1006949006728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsthoefel D. J., Liebl E. C., Kolodziej P. A. and Seeger M. A. (2005). The Abelson tyrosine kinase, the Trio GEF and Enabled interact with the Netrin receptor Frazzled in Drosophila. Development 132, 1983-1994. 10.1242/dev.01736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbe D. S. and Bashaw G. J. (2004). Axon guidance at the midline: from mutants to mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 319-341. 10.1080/10409230490906797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbe D. S. and Bashaw G. J. (2007). Independent functions of Slit-Robo repulsion and Netrin-Frazzled attraction regulate axon crossing at the midline in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 27, 3584-3592. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0301-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Z., Prado A., Melzig J., Heisenberg M., Nash H. A. and Raabe T. (2000). Mushroom body defect, a gene involved in the control of neuroblast proliferation in Drosophila, encodes a coiled-coil protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8122-8127. 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R., Sabatelli L. M. and Seeger M. A. (1996). Guidance cues at the Drosophila CNS midline: identification and characterization of two Drosophila Netrin/UNC-6 homologs. Neuron 17, 217-228. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80154-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock E. M., Culotti J. G. and Hall D. H. (1990). The unc-5, unc-6, and unc-40 genes guide circumferential migrations of pioneer axons and mesodermal cells on the epidermis in C. elegans. Neuron 4, 61-85. 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90444-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashijima S., Shishido E., Matsuzaki M. and Saigo K. (1996). eagle, a member of the steroid receptor gene superfamily, is expressed in a subset of neuroblasts and regulates the fate of their putative progeny in the Drosophila CNS. Development 122, 527-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi Y., Ohta N., Hisata K., Raabe T. and Matsuzaki F. (2006). Drosophila Pins-binding protein Mud regulates spindle-polarity coupling and centrosome organization. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 586-593. 10.1038/ncb1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C. A., Manning L., Lu M. S., Golub O., Doe C. Q. and Prehoda K. E. (2013). Formin-mediated actin polymerization cooperates with Mushroom body defect (Mud)-Dynein during Frizzled-Dishevelled spindle orientation. J. Cell Sci. 126, 4436-4444. 10.1242/jcs.129544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprielian Z., Runko E. and Imondi R. (2001). Axon guidance at the midline choice point. Dev. Dyn. 221, 154-181. 10.1002/dvdy.1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej P. A., Timpe L. C., Mitchell K. J., Fried S. R., Goodman C. S., Jan L. Y. and Jan Y. N. (1996). frazzled encodes a Drosophila member of the DCC immunoglobulin subfamily and is required for CNS and motor axon guidance. Cell 87, 197-204. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81338-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone M. S. (1985). Genetic dissection of Drosophila adenylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 5992-5996. 10.1073/pnas.82.17.5992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows L. A., Gell D., Broadie K., Gould A. P. and White R. A. (1994). The cell adhesion molecule, connectin, and the development of the Drosophila neuromuscular system. J. Cell Sci. 107, 321-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell K. J., Doyle J. L., Serafini T., Kennedy T. E., Tessier-Lavigne M., Goodman C. S. and Dickson B. J. (1996). Genetic analysis of Netrin genes in Drosophila: Netrins guide CNS commissural axons and peripheral motor axons. Neuron 17, 203-215. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80153-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisti C., Hein I., Grunwald Kadow I. C. and Suzuki T. (2015). Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, cooperates with Netrin/Frazzled in Drosophila midline guidance. Genes Cells 20, 50-67. 10.1111/gtc.12202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N. H. (1994). Imaging neuronal subsets and other cell types in whole-mount Drosophila embryos and larvae using antibody probes. Methods Cell Biol. 44, 445-487. 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)60927-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segalen M., Johnston C. A., Martin C. A., Dumortier J. G., Prehoda K. E., David N. B., Doe C. Q. and Bellaiche Y. (2010). The Fz-Dsh planar cell polarity pathway induces oriented cell division via Mud/NuMA in Drosophila and zebrafish. Dev. Cell 19, 740-752. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini T., Colamarino S. A., Leonardo E. D., Wang H., Beddington R., Skarnes W. C. and Tessier-Lavigne M. (1996). Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell 87, 1001-1014. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81795-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller K. H. and Doe C. Q. (2009). Spindle orientation during asymmetric cell division. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 365-374. 10.1038/ncb0409-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller K. H., Cabernard C. and Doe C. Q. (2006). The NuMA-related Mud protein binds Pins and regulates spindle orientation in Drosophila neuroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 594-600. 10.1038/ncb1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzweck B., Brankatschk M. and Dickson B. J. (2010). Distinct protein domains and expression patterns confer divergent axon guidance functions for Drosophila Robo receptors. Cell 140, 409-420. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart B. and Merriam J. R. (1973). Segmental aneuploidy of the X-chromosome. Drosophila Information Service 50, 167-170. [Google Scholar]

- Tear G. (1999). Axon guidance at the central nervous system midline. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55, 1365-1376. 10.1007/s000180050377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venken K. J. T., He Y., Hoskins R. A. and Bellen H. J. (2006). P[acman]: a BAC transgenic platform for targeted insertion of large DNA fragments in D. melanogaster. Science 314, 1747-1751. 10.1126/science.1134426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venken K. J. T., Carlson J. W., Schulze K. L., Pan H., He Y., Spokony R., Wan K. H., Koriabine M., de Jong P. J., White K. P. et al. (2009). Versatile P[acman] BAC libraries for transgenesis studies in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Methods 6, 431-434. 10.1038/nmeth.1331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg M., Bamps S., Soedling H., Hope I. A. and Dolphin C. T. (2010). Escherichia coli MW005: lambda Red-mediated recombineering and copy-number induction of oriV-equipped constructs in a single host. BMC Biotechnol. 10, 27 10.1186/1472-6750-10-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]