Abstract

Palladium-catalysed C(sp2)–N cross-coupling (that is, Buchwald–Hartwig amination) is employed widely in synthetic chemistry, including in the pharmaceutical industry, for the synthesis of (hetero)aniline derivatives. However, the cost and relative scarcity of palladium provides motivation for the development of alternative, more Earth-abundant catalysts for such transformations. Here we disclose an operationally simple and air-stable ligand/nickel(II) pre-catalyst that accommodates the broadest combination of C(sp2)–N coupling partners reported to date for any single nickel catalyst, without the need for a precious-metal co-catalyst. Key to the unprecedented performance of this pre-catalyst is the application of the new, sterically demanding yet electron-poor bisphosphine PAd-DalPhos. Featured are the first reports of nickel-catalysed room temperature reactions involving challenging primary alkylamine and ammonia reaction partners employing an unprecedented scope of electrophiles, including transformations involving sought-after (hetero)aryl mesylates for which no capable catalyst system is known.

The development of highly effective Earth-abundant catalysts for C(sp

2)-N cross-coupling represents an on-going challenge in synthetic chemistry. Here, the authors report a nickel complex containing a bisphosphine ancillary ligand allowing room-temperature couplings of amines and ammonia with a range of electrophiles.

The development of highly effective Earth-abundant catalysts for C(sp

2)-N cross-coupling represents an on-going challenge in synthetic chemistry. Here, the authors report a nickel complex containing a bisphosphine ancillary ligand allowing room-temperature couplings of amines and ammonia with a range of electrophiles.

Homogeneous transition metal catalysis is employed broadly in synthetic organic chemistry, including in the pharmaceutical industry for the preparation of active pharmaceutical ingredients on bench-top and production scales1. The development of useful catalysts of this type that offer broad substrate scope is often made possible through the application of appropriately designed ancillary ligands; when coordinated to the reactive metal of interest, such ligands can dramatically enhance catalytic performance (for example, activity, selectivity and lifetime). The palladium-catalysed cross-coupling of NH substrates and (hetero)aryl (pseudo)halides (that is, Buchwald–Hartwig amination2,3,4,5,6, BHA; Fig. 1a) is a well-established C(sp2)-N bond-forming methodology whose rapid evolution can be attributed in large part to advances in ancillary ligand design. Indeed, BHA chemistry is now employed widely the synthesis of biologically active molecules and functional materials, including in the pharmaceutical industry with applications ranging from the rapid diversification of small-molecule libraries to larger-scale production1,7,8,9.

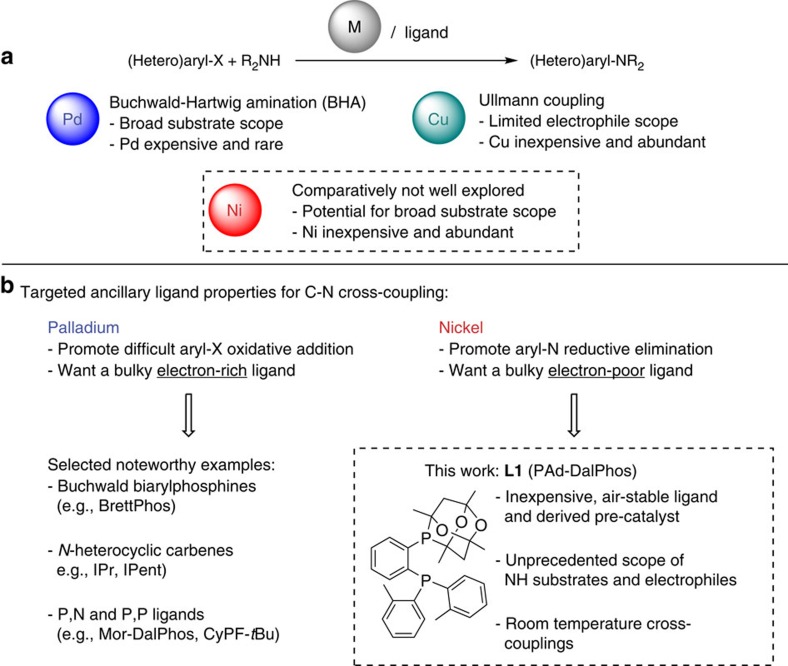

Figure 1. Approaches to metal-catalysed C–N cross-coupling.

(a) Generic equation for Buchwald–Hartwig amination and Ullmann C–N coupling to form a (hetero)aniline. (b) Ancillary ligand design strategies for palladium and nickel, along with the new ancillary ligand L1 (PAd-DalPhos).

In the years following the initial development of BHA chemistry, the preponderance of empirical data revealed that optimally configured ancillary ligands must be chosen when using challenging substrates such as (hetero)aryl chlorides, so as to promote the formation of electron-rich Pd(0) complexes that are activated towards otherwise challenging C(sp2)–Cl oxidative additions10,11, whereas also enabling C–N bond reductive elimination to afford the (hetero)aryl amine product. The steric demands of these two key mechanistic steps suggest the application of bulky ancillary ligands, to favour low-coordination12 and to encourage reductive elimination. However, the ancillary ligand electronic requirements for oxidative addition and reductive elimination are orthogonal, with strongly electron-donating ligands favouring oxidative addition, and less electron-donating ligands favouring reductive elimination13. Nonetheless, electron-rich and sterically demanding alkylphosphine and N-heterocyclic carbene ancillary ligands have in general proven to be most effective in challenging BHA chemistry, collectively giving rise to palladium catalysts that are capable of promoting the cross-coupling of a useful spectrum of aryl electrophiles and NH substrates6.

However, in recent years, there has been a shift in focus away from the use of catalysts based on rare and expensive precious metals such as palladium14, including in the pharmaceutical industry where the cost of both palladium and the required electron-rich ancillary ligands, as well as the potential for bulk palladium supply limitations, can be problematic. Notwithstanding some selected recent reports of copper-catalysed C(sp2)–N cross-couplings (that is, Ullmann C–N coupling) of ammonia15 or primary alkylamines16 at elevated temperatures (>100 °C), which are of relevance to our work presented herein, copper catalysis is typically not effective with low-cost and widely available (hetero)aryl chlorides or sulfonates17. Conversely, nickel catalysis offers the potential to supplant BHA protocols, being significantly less rare and expensive than palladium and having a proven track-record in alternative cross-couplings involving such challenging electrophiles18,19,20,21,22,23. The first report of nickel-catalysed C(sp2)–N cross-couplings involving aryl chlorides followed shortly after the establishment of BHA protocols24; nonetheless, nickel has received scant attention relative to palladium in such applications, due in part to the perception that the accessible oxidation state range for nickel21,25 would lead to complex reactivity profiles. However, recent studies support a Ni(0)/Ni(II) catalytic cycle in C(sp2)–N cross-couplings involving phosphine-ligated nickel species with aryl (pseudo)halides, much like that traversed by palladium in BHA chemistry26,27,28. This augers well for the application of rational ancillary ligand design as a means of developing highly effective nickel catalysts that are competitive with, and ideally superior to, palladium in such synthetically important amination reactions.

Despite such opportunities, the design of ancillary ligands specifically for use in enabling nickel-catalysed C(sp2)–N cross-couplings has not been reported. Rather, the most common strategy employed has involved the screening of ancillary ligands that have proven useful in related palladium catalysis. Such an approach has proven to be reasonably effective for the cross-coupling of some secondary amine substrates, with nickel catalyst systems based on triphenylphosphine29, 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene24,30, N-heterocyclic carbenes31,32, including 1,3-bis-(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene (IPr)33, and also phenanthrolines24,34 exhibiting desirable performance. Conversely, nickel catalysts capable of promoting the cross-coupling of alternative high-value NH substrates (for example, primary alkylamines, ammonia, azoles and others) are rare, limited in scope, and commonly require forcing reaction conditions.

Given the smaller atomic radius and distinct electronic properties of nickel, it is unlikely that the ‘re-purposing' of ancillary ligands that function well with palladium will be a universally effective strategy in the pursuit of superlative nickel catalysts for challenging C(sp2)–N cross-couplings; the design and application of new ancillary ligands targeted specifically for use in nickel catalysis represents a promising and complementary approach. More specifically, unlike the bulky electron-rich ancillary ligands that have proven optimal for use with palladium, we envisioned that sterically demanding yet relatively electron-poor bisphosphines might be well-suited for use with nickel, given the greater propensity for C(sp2)-Cl oxidative additions to Ni(0) versus Pd(0)10,35,36, and the associated potential for rate-limiting C(sp2)–N reductive elimination (Fig. 1b).

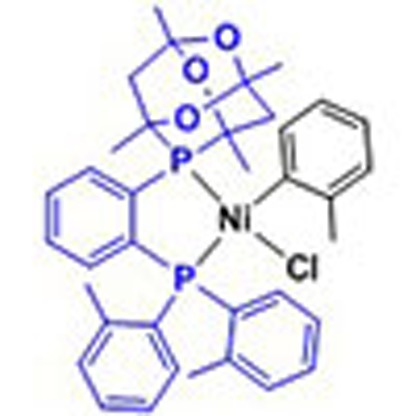

We report here on the development of the inexpensive, air-stable ortho-phenylene bisphosphine ligand L1 (PAd-DalPhos) that embodies these design criteria (Fig. 1b). The derived air-stable pre-catalyst (L1)Ni(o-tolyl)Cl (C1) is remarkably useful in otherwise challenging C(sp2)–N cross-coupling chemistry at relatively low catalyst loadings, accommodating the broadest combination of (hetero)aryl (pseudo)halide and NH coupling partners reported to date for any single nickel catalyst, without the need for precious metal co-catalysts or other additives. Included herein are the first reports of room-temperature nickel-catalysed cross-couplings involving primary alkylamines and ammonia, as well as examples of sought-after ammonia monoarylations employing (hetero)aryl mesylate electrophiles, for which no capable catalyst system of any type is known. Furthermore, we demonstrate the unusual versatility of C1 in the cross-coupling of carbazole, indole and 7-azaindole.

Results

Ancillary ligand design and catalyst screening

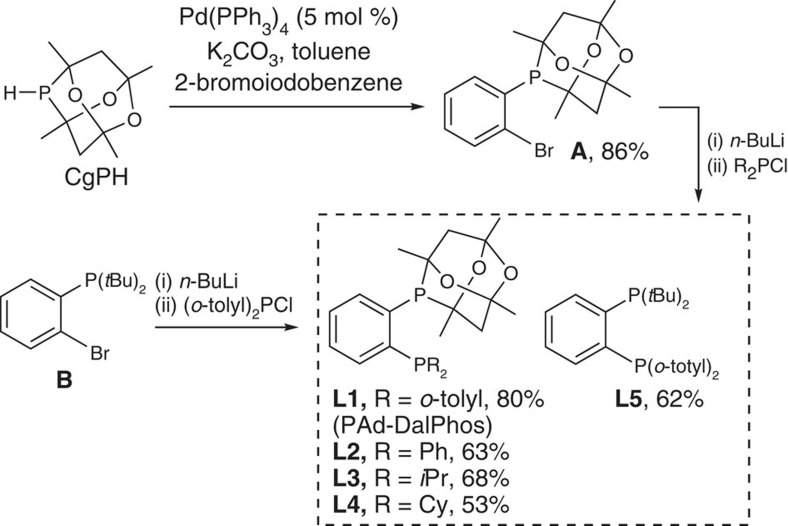

In the pursuit of bulky electron-poor bisphosphine ancillary ligands that would function well in nickel-catalysed amination chemistry, possibly by promoting C(sp2)–N reductive elimination, we sought tunable ortho-phenylene bisphosphines featuring the 1,3,5,7-tetramethyl-2,4,8-trioxa-6-phosphaadamantane (CgP) group with an adjacent phosphorus donor fragment that could be modified easily. Prior structural analyses have established that CgP is as sterically demanding as a P(tBu)2 fragment, while also being a relatively electron-poor phosphorus donor comparable to a P(OR)2 group37, thus making such a fragment well-suited to our ancillary ligand design interests. The use of CgPPh and related monophosphine ancillary ligand derivatives in palladium-catalysed cross-couplings dates to 2003 (ref. 38), with subsequent reports involving (carbonylative) BHA chemistry featuring only a limited scope of secondary amines and anilines39,40. Conversely, journal publications documenting the application of CgP-based ligands in nickel catalysis are limited to a single report focused on CgPOR-type phosphinites for the hydrocyanation of 3-pentenenitrile41. The new air-stable phosphaadamantane ligands L1–L4 (Fig. 2) were prepared straightforwardly in a two-step synthesis from relatively inexpensive, commercially available components via the common synthetic intermediate A. The new air-stable bisphosphine L5, a complementary variant of L1 featuring a P(tBu)2 donor in place of the CgP group, was prepared analogously from synthon B.

Figure 2. Synthesis of the bisphosphine ligands L1–L5.

L1–L4 are prepared from A, while L5 is prepared from B.

Ammonia ranks among the most widely produced commodity chemicals42, and selective ammonia monoarylation is sought-after as an atom-economical and scalable route to (hetero)anilines, including in the pharmaceutical industry. However, the development of such transformations has proven to be extremely challenging43,44 owing to uncontrolled polyarylation arising due to the primary (hetero)aniline products acting as contending substrates versus ammonia. Our group45, as well as Hartwig and co-workers28, independently disclosed the first and only examples of nickel-catalysed ammonia monoarylation, in which relatively electron-rich JosiPhos-type ligands were employed. Notwithstanding such progress, the failure of other top-performing bulky and electron-rich ancillary ligands45 from the domain of palladium-catalysed ammonia monoarylation (for example, CyPF-tBu JosiPhos46,47, Mor-DalPhos48, BippyPhos49) underscores the inconsistent nature of simply re-purposing ancillary ligands from palladium chemistry in the pursuit of nickel catalysts for such challenging C(sp2)–N cross-couplings. Moreover, there are a number of drawbacks associated with the reported Ni/JosiPhos catalyst systems28,45, including: the costly nature of the unnecessarily enantiopure JosiPhos ligand class; negligible demonstrated scope involving synthetically useful phenol-derived electrophiles (for example, sulfonates); and the need for elevated reaction temperatures (⩾100 °C).

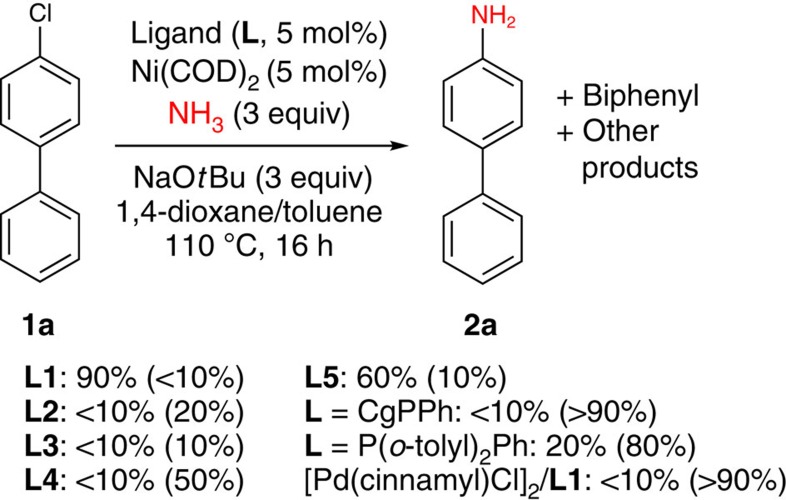

Against this background, we selected the monoarylation of ammonia with 4-chlorobiphenyl (1a) as a testing ground on which to evaluate the catalytic abilities of L1–L5 and related ligands (Fig. 3). Although Ni(COD)2/L2-L4 mixtures (COD=1,5-cyclooctadiene) performed poorly, use of Ni(COD)2/L1 afforded high conversion to the desired 4-aminobiphenyl (2a). These findings are in keeping with our view that sterically demanding yet relatively electron-poor bisphosphine ancillary ligands should support particularly effective nickel catalysts for such challenging cross-couplings (vide supra). Nonetheless, the competent performance of the P(tBu)2/P(o-tolyl)2 ancillary ligand L5, although inferior to the CgP/P(o-tolyl)2 variant L1 in the test reaction employed (Fig. 3), suggests that ancillary ligand sterics is particularly important in engendering useful catalytic behaviour within the nickel-catalysed C(sp2)–N cross-couplings under scrutiny herein. The poor performance of both CgPPh38 and P(o-tolyl)2Ph50, which did not vary when using Ni:L=1:1 or 1:2, confirms the benefit of bisphosphine ligation by L1. Finally, the observation that [Pd(cinnamyl)Cl]2/L1 mixtures afforded no conversion of 1a under analogous conditions underscores that the design of L1 (PAd-DalPhos) is particularly well-matched to the properties of nickel, rather than those of palladium, in this reaction setting.

Figure 3. Preliminary ligand screen in the nickel-catalysed monoarylation of ammonia.

Reactions employed 4-chlorobiphenyl (0.12 mmol), 0.5 M stock solutions of ammonia in 1,4-dioxane (0.72 ml) and toluene (1.00 ml). Conversions estimated on the basis of gas chromatographic data, reported as % 4-aminobiphenyl (% 4-chlorobiphenyl unreacted); mass balance attributable to biphenyl and/or other unidentified products; COD, 1,5-cyclooctadiene.

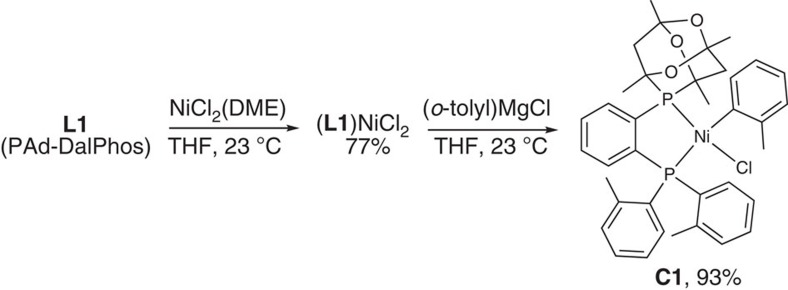

We subsequently sought to circumvent the use of costly and air/temperature-sensitive Ni(COD)2. Notwithstanding the reactivity benefits associated with the use of nitriles as co-ligands/additives27,28,30, and the utility of precious metal/nickel photoredox dual catalysis51, in an effort to facilitate end-user uptake we intentionally targeted operationally simple, air-stable nickel pre-catalysts, without recourse to the aforementioned experimental modifications. We thus turned our attention to the synthesis of (L1)Ni(o-tolyl)Cl (C1), which could be reduced to a requisite (L1)Ni(0) species under the amination conditions employed without the formation of inhibiting by-products30,52. Combination of L1 with NiCl2(DME) afforded (L1)NiCl2 in 77% isolated yield, and subsequent treatment with (o-tolyl)MgCl afforded (L1)Ni(o-tolyl)Cl (C1) in 93% isolated yield (Fig. 4). Each complex was obtained as an analytically pure solid, and was characterized by use of spectroscopic and crystallographic techniques (Fig. 5; solution and refinement information are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The κ2-P,P-bidentate nature of L1 is evident in the solid-state structures of both complexes, which are best described as exhibiting a distorted square planar geometry at nickel (Σangles at Ni∼360°). The catalytic performance of C1 was found to be identical to that of Ni(COD)2/L1 mixtures in the test reaction featured in Fig. 3, with no loss of performance observed following storage of L1 or C1 in air for an extended period (months). Moreover, the performance of C1 was found to be vastly superior to that of Ni(COD)2/L1 under more challenging reaction conditions (that is, room temperature, lower catalyst loadings), in keeping with catalyst inhibition by COD53.

Figure 4. Synthesis of the L1-derived nickel complexes (L1)NiCl2 and C1.

Isolated yields are provided; DME, 1,2-dimethoxyethane.

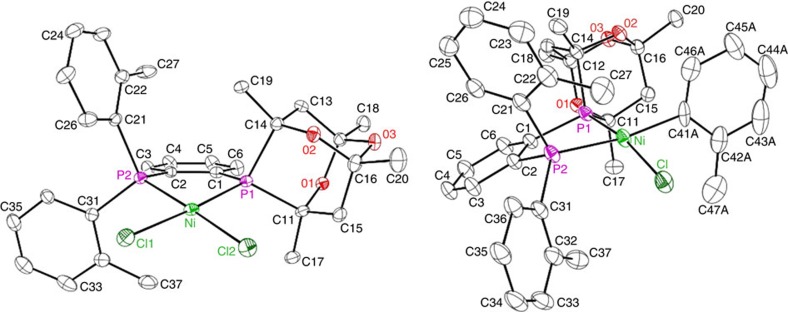

Figure 5. Single-crystal X-ray structures of (L1)NiCl2 and C1 depicted with hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity.

Selected interatomic distances (Å) and angles (°): for (L1)NiCl2 Ni-P1 2.1903(12), Ni-P2 2.1691(13), Ni-Cl1 2.2195(13), Ni-Cl2 2.1865(13), P1-Ni-P2 86.74(5), P1-Ni-Cl2 94.03(5), P2-Ni-Cl1 88.88(5), Cl1-Ni-Cl2 90.37(5); for C1: Ni-P1 2.1766(8), Ni-P2 2.2263(8), Ni-Cl 2.1916(8), Ni-C(aryl) 1.971(3), P1-Ni-P2 86.52(3), P1-Ni-C(aryl) 95.79(10), P2-Ni-C1 92.72(3), Cl-Ni-C(aryl) 87.53(10).

Ammonia monoarylation substrate scope using C1

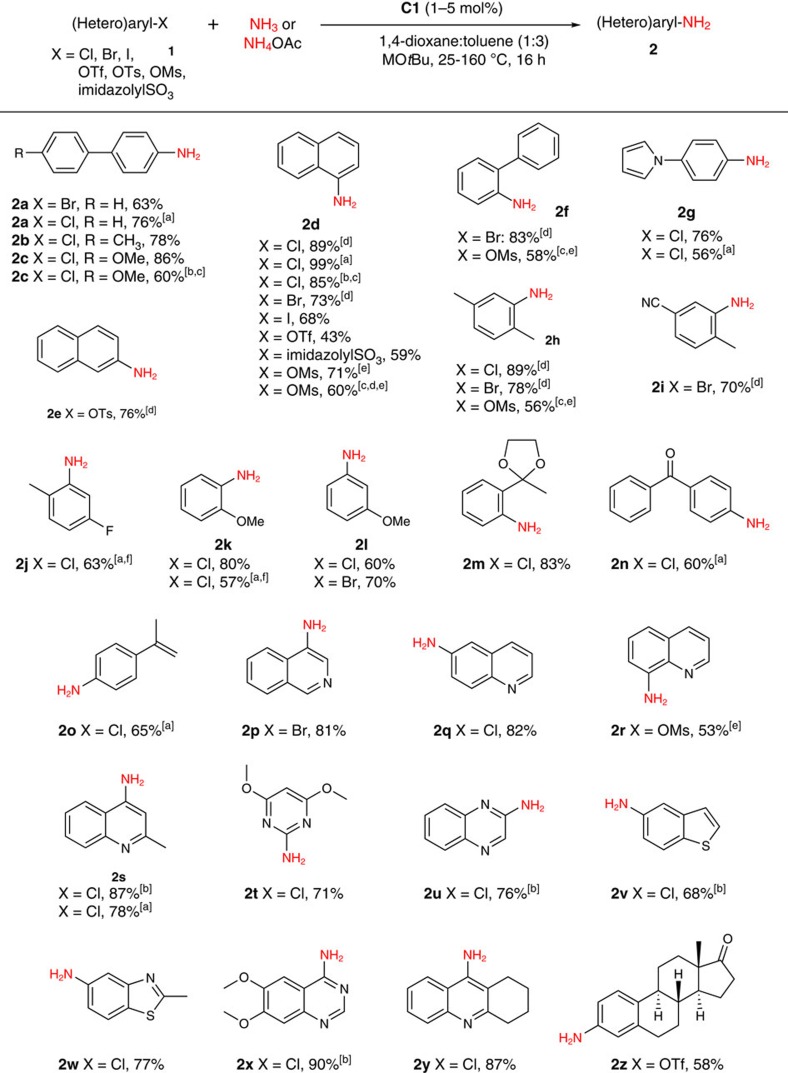

The scope of reactivity exhibited by C1 in the monoarylation of ammonia (Fig. 6), both in terms of the breadth of electrophilic partner (for example, chlorides, bromides, iodides, mesylates, tosylates, triflates and imidazolylsulfonates54) and the varied reaction conditions (for example, room temperature; microwave conditions; use of gaseous ammonia), exceeds that demonstrated previously for any catalyst (that is, palladium, copper, nickel or other). In keeping with the preliminary ligand screening experiments (Fig. 3), 4-aminobiphenyl monoarylation products (2a-c) were isolated in synthetically useful yields, as were 1- or 2-naphthylamines (2d,e) derived from an unprecedentedly wide array of 1- or 2-(pseudo)halonaphthalenes. Electrophiles featuring or lacking ortho-substitution were also accommodated, including variants incorporating pyrrole, cyano, fluoro, methoxy, dioxolane, ketone and alkene functionalities (2f-o). Given the importance of biologically active (hetero)anilines in pharmaceutical chemistry, we turned our attention to C1-catalysed ammonia monoarylations employing (hetero)aryl (pseudo)halide electrophiles. We were pleased to find that quinoline, isoquinoline, quinaldine, pyrimidine, quinoxaline, quinazoline, benzothiophene and benzothiazole core structures each proved compatible in this chemistry (2p-y). Notably, the quinazoline 2x represents the core structure found within a series of commercialized drugs, including doxazosin which is employed for the treatment of symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Moreover, the quinoline 2y (tacrine) has been used as a cholinesterase inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, whereas 3-aminoestrone (2z) has been identified as a key synthon for the construction of non-natural C-18 steroids for use in the treatment of prostate and breast cancers55.

Figure 6. Scope of ammonia monoarylation using C1.

Unless stated otherwise, reactions were conducted employing C1 (1–5 mol%), MOtBu (M=Li or Na; 1.5–2.0 equiv), NH3 (from 0.5 M solutions in 1,4-dioxane; 3–8.3 equiv), in toluene for 16 h (unoptimized), with yields of isolated products reported; throughout, see the Supplementary Information for complete experimental details. [a] 110–160 °C for 5–30 min under microwave conditions using NH4OAc (5 equiv) and NaOtBu (6.5 equiv) in CPME. [b] Conducted using gaseous ammonia (114 psi initial pressure). [c] Yield on the basis of 1H NMR data relative to ferrocene as an internal standard. [d] 25 °C. [e] K3PO4 (6 equiv) used as base at 110 °C without toluene co-solvent. [f] Isolated as the N-tosylated derivative.

Other distinguishing facets of the above-mentioned reactivity warrant further commentary. Whereas room temperature C(sp2)–N cross-couplings are attractive in terms of operational simplicity and reduced energy footprint, ammonia monoarylation has proven difficult; only a small number of such transformations have been achieved using palladium catalysis44, and none involving nickel catalysis. The remarkable ability of C1 to catalyse room temperature ammonia monoarylations is demonstrated in entries 2d-f,h,i, covering chloride, bromide, tosylate and mesylate electrophiles. Furthermore, the ability to conduct such room temperature ammonia monoarylation reactions on gram-scale was confirmed in the reaction of 1-chloronaphthalene with ammonia leading to 2d (2 mol% C1, 2.285 g, 76% isolated yield). Although we did not make an effort to optimize the reaction times, the monoarylation of ammonia using 1-chloronaphthalene was found to be complete (>90% conversion to 2d on the basis of GC data) after only 15 min when using 5 mol% C1, thereby underscoring the highly active nature of C1 under room temperature conditions. Although no loss in catalytic activity was observed in the monoarylation of ammonia using 1-chloronaphthalene when the solid reaction components including C1 were handled in air, followed by delivery of the ammonia stock solution on the benchtop within a nitrogen-purged glove-bag, analogous reactions conducted under an atmosphere of air were unsuccessful. The first examples of ammonia monoarylation employing (hetero)aryl mesylates (2d,f,h,r) involving any catalyst system are also reported. There is significant interest in the development of cross-couplings involving such electrophiles, given their low cost and greater atom economy relative to (hetero)aryl tosylates and triflates, and in the context that the methanesulfonic acid generated upon workup is naturally occurring and can undergo biodegradation under conventional waste-water processing56,57. Finally, scalability issues in ammonia monoarylation would suggest the use of gaseous ammonia, whereas the application of ammonium salts28 offers operational simplicity in bench-scale syntheses. The ability of C1 to function effectively both when using high pressures of gaseous ammonia (2c,d,s,u,v,x), and alternatively ammonium acetate under microwave reaction conditions at elevated reaction temperatures (2a,d,g,j,k,n,o,s), is unique among all previously reported catalyst systems for ammonia monoarylation.

Primary alkylamine monoarylation substrate scope using C1

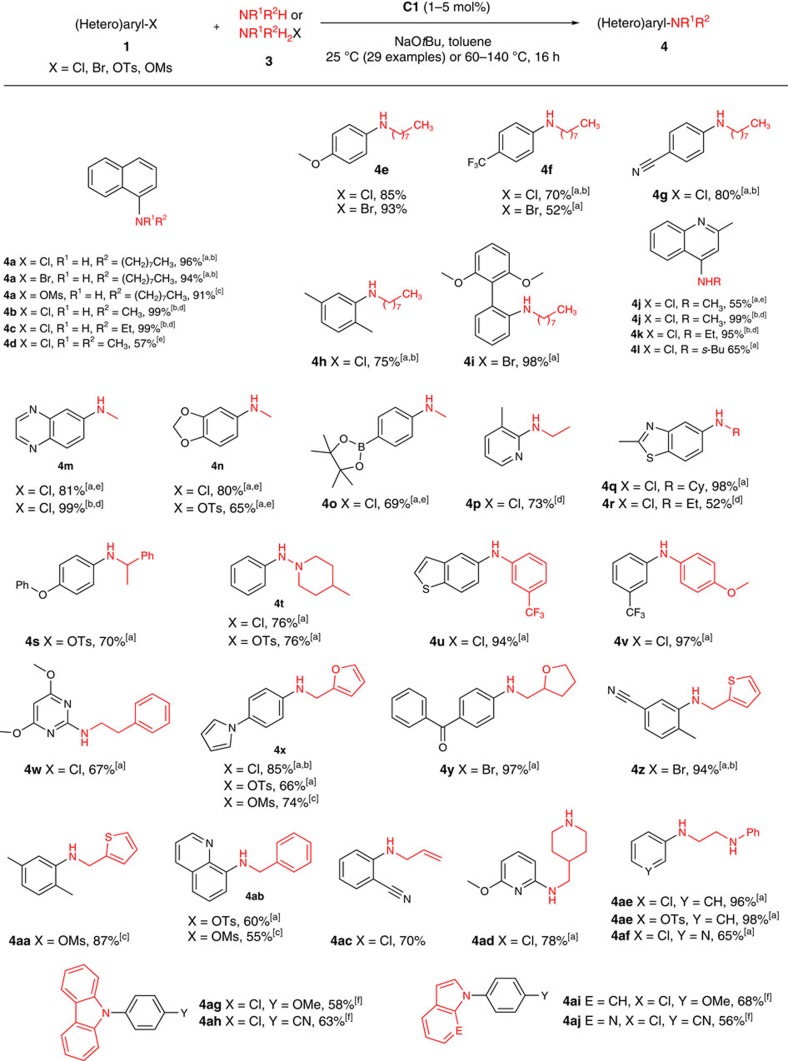

Primary alkylamines represent an important yet relatively challenging class of substrates in C(sp2)–N cross-coupling chemistry6. As in the case of ammonia monoarylation, palladium complexes featuring bulky electron-rich ancillary ligands are the catalysts of choice for such transformations. The state-of-the-art nickel pre-catalyst for the monoarylation of primary alkylamines is (rac-BINAP)Ni(η2-NC-Ph) (rac-BINAP=racemic 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl) reported by Hartwig and co-workers27. However, a number of notable limitations exist, including: the air-sensitive nature of this nickel(0) pre-catalyst; the lack of electrophile scope beyond (hetero)aryl chlorides; the use of 50% excess of the alkylamine versus the electrophile; and the absence of demonstrated room temperature catalysis. Use of the air-stable pre-catalyst C1 addressed these shortcomings, with the observed reaction scope (Fig. 7) rivaling that achieved by use of the best palladium catalysts. A diversity of electron-rich and electron-poor (hetero)aryl (pseudo)halides were successfully cross-coupled with linear and branched primary alkylamines featuring in some cases heterocyclic addenda, as well as a hydrazine derivative and primary anilines. Remarkably, 29 of the reported entries proceeded efficiently at room temperature, covering chloride, bromide and tosylate electrophiles. The gram-scale cross-coupling of 1-chloronaphthalene and octylamine at room temperature leading to 4a was also achieved (3 mol% C1, 2.703 g, 90% isolated yield). Included in the substrate scope are the first examples of nickel-catalysed primary alkylamine monoarylation employing (hetero)aryl mesylates (4a,x,aa,ab); related palladium-catalysed transformations are limited to a single report58. In an effort to evaluate whether C(sp2)–N cross-couplings employing C1 and chiral amines could be conducted without racemization59, the room-temperature cross-coupling of racemic and separately enantiopure α-methylbenzylamine leading to 4s was conducted; 1H NMR analysis, employing a europium chiral shift reagent, of the 4s product thus formed indicated the absence of racemization when using enantiopure α-methylbenzylamine. Reactions involving small nucleophilic reagents such as methylamine and ethylamine employing commercial stock solutions of these amines, or alternatively alkylammonium salts under microwave conditions, proceeded successfully. The formation of the pinacolborane derivative 4o demonstrated the feasibility of conducting C1-catalysed C(sp2)–N cross-couplings in the presence of a potentially reactive pinacolborane moiety, which may be exploited subsequently in an orthogonal cross-coupling step. The preferred arylation of a primary alkylamine fragment in the presence of contending secondary amine groups by C1 was demonstrated in the chemoselective formation of 4ad-af. These transformations are in keeping with our observation that secondary dialkylamines (for example, morpholine) are not suitable substrates for C1 under the conditions outlined in Fig. 7, despite our successful arylation of dimethylamine leading to 4d. Finally, we sought to evaluate the ability of C1 to catalyse the N-arylation of carbazole, indole and 7-azaindole—a class of nickel-catalysed transformations that was reported for the first time in 2015 by Belderrain, Nicasio and co-workers employing IPr60. These nucleophiles were successfully N-arylated employing electron-rich and electron-poor electrophiles, affording 4ag-aj. The successful C(sp2)–N cross-coupling of ammonia, primary alkylamines and indoles by use of C1 is particularly remarkable, given that these compounds span more than 20 orders of magnitude in terms of NH acidity.

Figure 7. Scope of amine monoarylation using C1.

Unless stated otherwise, reactions were conducted employing C1 (1–5 mol%), NaOtBu (1.5 equiv), amine (1.1 equiv), in toluene for 16 h (unoptimized), with yields of isolated products reported; throughout, see the Supplementary Information for complete experimental details. [a] 25 °C. [b] 1 mol% C1. [c] K3PO4 (6 equiv) used as base, in CPME at 110 °C. [d] 110–140 °C for 5–30 min under microwave conditions using NaOtBu (6.5 equiv) and MeNH3Cl or EtNH3Cl (5 equiv) in CPME. [e] 3–7 equiv amine. [f] 10 mol% C1, NaOtBu (3 equiv), amine (1 equiv) in 1,4-dioxane at 110 °C.

Discussion

The pre-catalyst C1, featuring the sterically demanding and electron-poor bisphosphine ancillary ligand L1 (PAd-DalPhos), enables unprecedented nickel-catalysed C(sp2)–N cross-coupling chemistry under mild conditions and without the need for a precious metal co-catalyst. The utility of C1 is showcased in the first reports of room-temperature nickel-catalysed reactions involving primary alkylamines and ammonia, including reactions involving (hetero)aryl mesylates, for which no capable catalyst system of any type had been described previously. The unusual versatility of this pre-catalyst is further demonstrated in the cross-coupling of (hetero)indoles.

The ‘re-purposing' of ancillary ligands that function well with palladium has in some cases proven useful in the development of nickel catalysts for use in cross-coupling chemistry. A complementary approach involves the design of new ancillary ligands whose structural features take into account the specific reactivity properties of nickel, as compared with those of palladium. Using this latter approach, our results presented herein confirm that sterically hindered and relatively electron-poor bisphosphines, as exemplified by L1, represent promising ancillary ligand candidates in the quest to address outstanding challenges in nickel-catalysed C(sp2)–N cross-coupling chemistry and beyond. Unlike palladium chemistry, the applicability of diverse ancillary ligand strategies for use in enabling varied nickel-catalysed cross-couplings is crucial not only in terms of promoting elementary catalytic steps, but also as a means of favouring desired oxidation states of nickel, given the established viability of both Ni(0)/Ni(II) and Ni(I)/Ni(III) catalytic cycles. In this regard, we envision that the ancillary ligand design strategies employed herein will contribute towards the development of high-performing nickel catalysts for use in a range of synthetically important cross-coupling applications, so as to enable more sustainable chemical practices that circumvent the use of precious metals such as palladium.

Methods

General considerations

Unless otherwise stated, all reactions were setup inside a nitrogen-filled inert atmosphere glovebox, and were worked up in air using benchtop procedures. Toluene was deoxygenated by sparging with nitrogen followed by passage through a double column solvent purification system packed with alumina and copper-Q5 reactant, and storage over activated 4 Å molecular sieves. Cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) was degassed by use of three repeated freeze–pump–thaw cycles and was stored over activated 4 Å molecular sieves. 1,4-Dioxane used in General Procedure I (GPI) was dried over Na/benzophenone followed by distillation under a nitrogen atmosphere. Otherwise, all reagents, solvents and materials were used as received from commercial sources. Column chromatography was carried out using Silicycle SiliaFlash 60 silica (particle size 40–63 μm; 230–400 mesh) or using neutral alumina (150 mesh; Brockmann-III; activated), as indicated. Preparatory thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on Silicycle plates (TLG-R1001B-341, silica glass-backed TLC Extra Hard Layer, 60 Å, thickness 1 mm, indicator F-254). Unless stated, NMR spectra were recorded at 300 K in CDCl3 with chemical shifts expressed in parts per million (p.p.m.) using the residual CHCl3 solvent signal (1H, 7.26 p.p.m.; 13C, 71.4 p.p.m.) as an internal reference or H3PO4 as an external reference (31P, 0.00 p.p.m.). Splitting patterns are indicated as follows: br, broad; s, singlet; d, doublet; m, multiplet, with all coupling constants (J) reported in Hertz (Hz). In some cases, fewer than expected independent 13C NMR resonances were observed despite prolonged acquisition times. For NMR analysis of the compounds in this article, see the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figs 1–142. Mass spectra were obtained using ion trap electrospray ionization (ESI) instruments operating in positive mode, and gas chromatography (GC) data were obtained on an instrument equipped with a SGE BP-5 column (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d.).

Synthesis of A

To a glass screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar was added 2-bromoiodobenzene (0.73 ml, 5.7 mmol, 1.05 equiv), toluene (9.0 ml), Pd(PPh3)4 (0.330 g, 0.285 mmol), K2CO3 (1.571 g, 11.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv) and 1,3,5,7-tetramethyl-2,4,8-trioxaphosphaadamantane (1.14 g, 5.3 mmol). The vial was sealed with a poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE)-lined cap and was removed from the glovebox. The vial was placed in an oil bath set to 110 °C and magnetic stirring was initiated. After 48 h (unoptimized), the reaction mixture was cooled, diluted with CH2Cl2 (50 ml) and washed with distilled water (3 × 50 ml). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and the collected eluent solution was concentrated under reduced pressure by use of a rotary evaporator. The resulting yellow oil was filtered through an alumina plug (ca 50 g) eluting with 90% hexanes/CH2Cl2; the solvent was then removed from the collected eluent under reduced pressure by use of a rotary evaporator. The resulting yellow solid was purified by flash chromatography over silica, eluting with 10% ethyl acetate/hexanes to afford A as a white solid (1.69 g, 86% yield). 1H NMR: (CDCl3, 500 MHz) 8.29 (d, J=7.7, 1H), 7.66–7.64 (m, 1H), 7.37 (apparent t, J=7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (apparent t, J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 2.14 (m, 1H), 2.02-1.89 (m, 2H), 1.55–1.44 (m, 13H). 13C{1H} NMR: (CDCl3, 125.8 MHz) 135.3 (d, J=22.6 Hz), 135.2, 133.8 (d, J=2.5 Hz), 133.2 (d, J=37.7 Hz), 131.0, 127.5, 97.0, 96.2, 74.5 (d, J=10.1 Hz), 73.9 (d, J=25.2 Hz), 45.8 (d, J=20.1 Hz), 36.5, 28.7 (d, J=18.9 Hz), 28.2, 27.9, 26.7 (d, J=11.3 Hz). 31P{1H} NMR: (CDCl3, 202.5 MHz) −29.6. High resolution mass spectrometry-electrospray ionization (HRMS-ESI) (m/z): calculated for C16H2079BrNaO3P [M+ Na]: 393.0226; found: 393.0214.

General procedure for the synthesis of L1–L4

Compound A and diethyl ether (∼0.3 M in A) were added to a glass screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar. The vial was sealed with a cap featuring a PTFE septum. The solution was then cooled to −33 °C and magnetic stirring was initiated, followed by dropwise addition of n-butyllithium (1.5 equiv, 2.5 M in hexanes) via syringe. The resulting mixture was left to stir for 30 min while warming to ambient temperature. At this point, the appropriate chlorophosphine (R2ClP, R=o-tol, Ph, iPr, Cy; 1.2 equiv) was added dropwise via syringe with continued stirring. The resulting mixture was left to stir for 48 h (unoptimized) at ambient temperature, after which the crude reaction mixture was opened to air on the benchtop and was filtered through a short Celite plug; the collected eluent was concentrated by use of a rotary evaporator. The residue was adsorbed onto silica (ca 1 g) and was then concentrated to dryness by use of a rotary evaporator. The so-formed silica dry pack was added to a silica plug (ca 50 g), and 10% EtOAc/hexanes (ca 300 ml) was passed through the plug. The collected eluent was then concentrated to dryness by use of a rotary evaporator, was washed with cold pentane (3 × 1.5 ml) and was then dried in vacuo to afford the desired bisphosphine as a white to off-white solid (R=o-tolyl, L1: 80%; R=Ph, L2: 63%; R=iPr, L3: 68%; R=Cy, L4: 53%). Please note that the cyclohexyl variant L4 was purified by flash chromatography over silica (ca 50 g) eluting with 10% EtOAc/hexanes. Note that the NMR spectral assignments for L1–L4 and C1 in some cases was rendered complex by: the C1-symmetric nature of these species owing to the chiral (racemic) phosphaadamantane group; second-order coupling; dynamic behaviour (as evidenced in the temperature-dependent 31P{1H} NMR spectra of L1) and possibly in the case of C1 dynamic equilibria involving rotamers and/or between tetrahedral and square planar species.

Data for L1 PAd-DalPhos

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): 8.32 (m, 1H), 7.39 (m, 1H), 7.29–7.21 (m, 5H), 7.11–7.04 (m, 2H), 6.89–6.87 (m, 1H), 6.79 (dd, J=7.2, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 6.64 (m, 1H), 2.42 (s, 3H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 2.14–1.79 (m, 3H), 1.57–1.21 (m, 13H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125.8 MHz): 142.7–142.2 (m), 134.2, 133.5, 130.3-130.0 (m), 128.8-128.6 (m), 126.4, 125.8, 97.2, 96.3, 74.5–74.2 (m), 46.1 (d, J=18.9 Hz), 36.6, 28.4–28.0 (m), 26.3 (d, J=11.3 Hz), 21.7, 21.5. 31P{1H} NMR: (CDCl3, 202.5 MHz, 298 K) −24.1 (broad m), −37.7 (d, J=166 Hz). 31P{1H} NMR: (CDCl3, 121.5 MHz, 223 K) −23.8 (d, J=160 Hz, major species), −30.2 to −33.0 (broad m, minor species), −38.8 (d, J=177 Hz, minor species), −39.4 (d, J=160 Hz, major species). HRMS-ESI (m/z): calculated for C30H34NaO3P2 [M+Na]: 527.1881; found: 527.1875. Analysis calculated for C30H34O3P2: C, 71.42; H, 6.79. Found: C, 71.12; H, 6.84.

Data for L2

1H NMR: (CDCl3, 500 MHz): 8.36–8.33 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.30 (m, 10H), 7.23–7.19 (m, 2H), 7.02–6.99 (m, 1H), 2.12–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.94 (m, 1H), 1.56–1.53 (m, 1H), 1.49 (s, 3H), 1.43–1.40 (m, 6H), 1.33 (d, J=12.4 Hz, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125.8 MHz): 147.5–147.1 (m), 140.5–140.0 (m), 137.9–137.5 (m), 134.6 (m), 134.2 (m), 133.5 (m), 129.9, 128.9–128.6 (m), 128.4 (two signals), 97.1, 96.2, 74.6, 74.5 (m), 46.1 (d, J=18.9 Hz), 36.6, 28.4-28.0 (m), 26.5 (d, J=11.3 Hz). 31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 202.5 MHz): −12.5 (d, J=168 Hz, 1P), −37.6 (d, J=168 Hz, 1P). HRMS-ESI (m/z): calculated for C30H34NaO3P2 [M+Na]: 499.1562; found: 499.1562.

Data for L3

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): 8.36–8.31 (m, 1H), 7.59 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.36 (m, 2H), 2.42–2.36 (m, 1H), 2.20–1.87 (m, 4H), 1.46–1.36 (m, 13H), 1.24 (dd, J=15.4, 6.8 Hz, 3H), 1.14 (m, 3H), 1.01–0.90 (m, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125.8 MHz): 134.1, 133.5 (m), 132.4 (m), 129.1 (two signals), 128.7 (m), 97.1, 96.2, 74.8. 74.7, 74.3–74.0 (m), 46.3 (d, J=20.1 Hz), 36.4, 28.4–28.0 (m), 26.7 (d, J=11.3 Hz), 22.9 (m), 20.7–19.8 (m), 18.0. 31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 202.5 MHz): −38.5 to −39.2 (m). HRMS-ESI (m/z): calculated for C30H34 NaO3P2 [M+Na]: 431.1875; found: 431.1867.

Data for L4

1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): 8.35–8.33 (m, 1H), 7.68 (broad s, 1H), 7.42–7.40 (m, 2H), 2.19–1.09 (m, 38H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125.8 MHz): 134.0, 133.1, 128.8, 128.5, 97.1, 96.2, 74.7 (two signals), 74.2 (m), 46.4 (d, J=18.9 Hz), 37.0–36.4 (m), 33.0–32.8 (m), 31.1–30.0 (m), 28.4–26.6 (m). 31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 202.5 MHz): −14.0 (broad m), −39.6 (broad m). HRMS-ESI (m/z): calculated for C28H43O3P2 [M+H]: 489.2687; found: 489.2682.

Synthesis of L5

To a glass screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar was added (2-bromophenyl)-di-tert-butylphosphine61 (B, 145.1 mg, 0.482 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and diethyl ether (1.5 ml). The vial was sealed with a cap featuring a PTFE septum. The solution was then cooled to −33 °C and magnetic stirring was initiated, followed by dropwise addition of n-butyllithium (0.29 ml, 2.5 M in hexanes, 1.5 equiv) via syringe. The resulting mixture was left to stir for 30 min while warming to ambient temperature. At this point, chlorodi(o-tolyl)phosphine (126 mg, 0.506 mmol, 1.05 equiv) was dissolved in diethyl ether (1.0 ml) and was added dropwise via syringe to the reaction vial with continued stirring. The resulting mixture was left to stir for 48 h (unoptimized) at ambient temperature, after which the crude reaction was opened to air on the benchtop and was filtered through a short Celite plug; the collected eluent was concentrated by use of a rotary evaporator. The residue was adsorbed onto silica (ca 1 g) and was then concentrated to dryness by use of a rotary evaporator. The so-formed silica dry pack was added to a silica plug (ca 50 g), and 1% EtOAc/hexanes (ca 200 ml) was passed through the plug. The collected eluent was then concentrated to dryness by use of a rotary evaporator, was washed with cold pentane (3 × 1.5 ml) and was then dried in vacuo to afford L5 as an off-yellow solid (0.130 g, 62% yield). 1H NMR (300.1 MHz, CDCl3): δ=7.78 (br s, 1H), 7.34–7.19 (m, 6H), 7.07–6.98 (m, 3H), 6.86–6.82 (m, 2H), 2.47 (br s, 6H), 1.11–1.07 (br d, J=10.5 Hz, 18H); 13C{ 1H} NMR (125.8 MHz, CDCl3): δ=143.1 (m), 135.4, 135.1, 133.2, 130.1, 129.2, 128.4, 127.4, 126.0, 33.3 (m), 30.7 (d, J=11.3 Hz), 21.8, 21.7; 31P{1H} NMR (121.5 MHz, CDCl3): δ=20.7 (d, J=167 Hz, 1P), −27.5 (d, J=166 Hz, 1P). HRMS-ESI (m/z): calculated for C28H37P2 [M+H]: 435.2292; found: 435.2365.

Synthesis of (L1)NiCl2

In a dinitrogen filled glovebox, a 100-ml oven-dried round bottom flask containing a magnetic stir bar was charged with NiCl2(DME) (1.78 g, 8.10 mmol) and L1 (PAd-DalPhos; 4.54 g, 9.00 mmol, 1.1 equiv). The solid mixture was dissolved in ca 90 ml of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and the resulting solution was stirred magnetically at room temperature for 1 h. The crude reaction mixture was poured directly onto a glass frit and was washed with pentane (5 × 30 ml). The remaining solid on the frit was dissolved by passing CH2Cl2 through the frit (ca 50 ml), followed by collection of the eluent. The solvent was removed in vacuo affording the desired product as a dark purple paramagnetic solid (3.93 g, 77%). Anal. calculated for C30H34Cl2NiO3P2 C, 56.82; H, 5.40. Found: C, 56.72; H, 5.65. A single crystal suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis was prepared by slow evaporation of pentane into a solution of CH2Cl2 at room temperature.

Synthesis of C1

(L1)NiCl2 (3.90 g, 6.15 mmol) and THF (62 ml) were added to an oven-dried 100 ml round-bottom flask containing a magnetic stir bar. Magnetic stirring was initiated and ortho-tolylmagnesium chloride was then added dropwise (7.40 ml, 7.40 mmol, 1.2 equiv, 1.0 M in THF) to the heterogeneous mixture, resulting in an immediate colour change from red to orange. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction mixture was subsequently treated with MeOH (5 ml) in air, and then was reduced to dryness in vacuo. The residue was treated with cold MeOH (0 °C, 15 ml), and the crude reaction mixture was then filtered through a glass frit, affording a retained orange solid that was washed with additional cold MeOH (0 °C, 3 × 10 ml), followed by pentane (3 × 50 ml). The orange solid on the frit was then dissolved via addition of CH2Cl2 (50 ml). Collection of the eluent followed by removal solvent afforded (L1)Ni(o-tolyl)Cl, C1, as an orange solid (3.95 g, 93% yield). The existence of a major and minor disastereomers (ca 2:1) in solution is suggested on the basis of 31P{1H} NMR data. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): 8.74 (m, 1H), 7.59–7.09 (m, 10H), 6.86–6.67 (m, 5H), 3.33–2.59 (m, 9H), 1.98–1.93 (m, 1H), 1.59–1.53 (m, 6H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.10–0.92 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 125.8 MHz): 145.9 (m), 145.8 (m), 143.4–143.2 (m), 136.7–133.1 (m), 132.0–130.9 (m), 129.6–128.6 (m), 126.3–125.8 (m), 124.7 (m), 123.8 (m), 122.7, 97.8–96.2 (m), 40.2–39.6 (m), 28.8–24.2 (m). 31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 202.5 MHz): 32.6 (d, J=4.3 Hz, minor species), 31.5 (d, J=4.6 Hz, major species), 27.6 (d, J=4.6 Hz, major species), 26.5 (d, J=4.3 Hz, minor species). On the basis of the observed positional disorder associated with the Ni-bound ortho-tolyl fragment within the X-ray structure of C1, arising from Ni-C(tolyl) bond rotation (80:20 occupancy ratio), we interpret the major and minor species as being rotamers of this type. Anal. calculated for C37H41ClNiO3P2 C, 64.42; H, 5.99. Found: C, 64.11; H, 5.84. A single crystal suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis was prepared by slow evaporation of pentane into a solution of CH2Cl2 at room temperature.

General catalytic procedure A (GPA)

Unless specified otherwise in the text, C1 (8.3–20.7 mg, 0.0012–0.030 mmol, 2–5 mol %), aryl (pseudo)halide (0.60 mmol, 1 equiv) and NaOtBu (115.3 mg, 1.20 mmol, 2.0 equiv) were added to a screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar, to which was added toluene (9 ml) and NH3 as a 0.5 M solution in 1,4-dioxane (1.8–4.2 mmol, 3–7 equiv, 3.0–8.4 ml). The vial was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum, was removed from the glovebox and placed in a temperature-controlled aluminum heating block set at 110 °C, and was allowed to react under the influence of magnetic stirring for 16 h (unoptimized). The vial was then removed from the heating block and was left to cool to ambient temperature, after which the reaction mixture was worked up as indicated.

General catalytic procedure for heteroaryl halides and ammonia (GPB)

Unless specified otherwise in the text, C1 (10.4 mg, 0.015 mmol, 3 mol %), aryl (pseudo)halide (0.5 mmol, 1 equiv) and LiOtBu (60.0 mg, 0.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were added to a screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar, followed by the addition of toluene (4.2 ml) and NH3 as a 0.5 M solution in 1,4-dioxane (3.5 mmol, 7 equiv). The vial was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum, was removed from the glovebox and placed in a temperature-controlled aluminum heating block set at 110 °C, and was allowed to react under the influence of magnetic stirring for 16 h (unoptimized). The vial was then removed from the heating block and was left to cool to ambient temperature. The crude reaction mixture was dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 ml) and poured onto brine (10 ml). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 ml). The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by use of column chromatography over silica.

General catalytic procedure for aryl mesylates and ammonia (GPC)

Unless specified otherwise in the text, C1 (4.14 mg, 0.006 mmol, 5 mol%), K3PO4 (152.8 mg, 0.72 mmol, 6.0 equiv) and aryl mesylate (0.12 mmol, 1.0 equiv), followed by NH3 as a 0.5 M solution in 1,4-dioxane (0.75 mmol, 6.25 equiv) were added to a screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar. The vial was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum, was removed from the glovebox and placed in a temperature-controlled aluminum heating block set at 110 °C, and was allowed to react under the influence of magnetic stirring for 16 h (unoptimized). The vial was then removed from the heating block and was left to cool to ambient temperature. The crude reaction mixture was dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 ml) and poured onto brine (10 ml). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 ml). The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by use of column chromatography over alumina or silica as specified.

General catalytic procedure for microwave reactions with ammonium salts (GPD)

C1 (6.9–34.5 mg, 0.01–0.05 mmol, 1–5 mol%), ammonium salt (5 equiv, 5 mmol), NaOtBu (6.5 equiv, 6.5 mmol) and aryl (pseudo)halide (1 mmol) were weighed into an oven-dried 20 ml microwave vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar. CPME (10 ml) was then added to the vial, the vial was sealed with an aluminum crimp cap featuring a PTFE/silicone septum, and was removed from the glovebox. The vial was then heated to the specified temperature in a Biotage Initiator+ microwave reactor for the specified time, using fixed-hold time. The vial was then removed from the microwave reactor and was left to cool to ambient temperature, at which point the reaction mixture was taken up in CH2Cl2 (ca 50 ml) and was washed with distilled water (3 × 50 ml). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by use of column chromatography using a Biotage Isolera One automated column using a EtOAc:hexanes gradient on a 25-g Biotage Snap cartridge. Notably, although NH4OAc proved effective as an ammonia source in these reactions; the use of NH4Cl, (NH4)2SO4, LiNH2 or LiN(TMS)2 afforded negligible conversion to product on the basis of gas chromatographic analysis.

General catalytic procedure for reactions using ammonia gas (GPE)

Unless specified otherwise in the text, a vial (1 dram, 3.696 ml) containing a magnetic stir bar was charged with C1 (0.018 mmol, 5 mol%), LiOtBu (43.2 mg, 0.54 mmol, 1.5 equiv), toluene (1.0 ml) and aryl (pseudo)halide (0.36 mmol, 1.0 equiv). The resulting solution was stirred briefly and then was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum; the septum was then punctured with a 26G1/2 PrecisionGlide needle and the needle was not removed until the final workup. The reaction vial was placed in a high-pressure reaction chamber purchased from the Parr Instrument Company (type 316 stainless steel, equipped with a thermocouple immersed in oil to allow for accurate external temperature monitoring within the reaction chamber proximal to the placement of the reaction vial), and the reaction chamber was sealed under nitrogen within the glovebox. The reaction chamber was removed from the glovebox, and was placed in an oil bath at room temperature that was mounted on top of a hot-plate/magnetic stirrer. The reaction chamber was fitted with a braided and PTFE-lined stainless steel hose designed for use with corrosive gases that was connected to a tank of anhydrous ammonia gas. Magnetic stirring was initiated and the reaction chamber was purged with ammonia for ∼5 min, after which time the reaction chamber was pressurized with ammonia (114 psi maintained for 30 min at room temperature). The reaction chamber was then sealed, disconnected from the ammonia tank, and was heated at 110 °C for 16 h; pressure was built up to 150 p.s.i. over the course of the reaction. The reaction chamber was allowed to cool to room temperature, after which the contents of the reaction chamber were vented slowly within a fumehood. The products were removed from the pressure reaction chamber, the crude reaction mixture was dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 ml) and poured onto brine (10 ml). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 ml). The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by use of column chromatography or over silica.

General catalytic procedure for aryl halides and primary amines (GPF)

Unless specified otherwise in the text, C1 (10.3 mg, 0.015 mmol, 3 mol%), NaOtBu (72.3 mg, 0.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv), aryl (pseudo)halide (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv), amine (0.55 mmol, 1.1 equiv) and toluene (4.7 ml) were added to a screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar. The vial was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum, was removed from the glovebox and placed in a temperature-controlled aluminum heating block set at the specified temperature, and was allowed to react under the influence of magnetic stirring for 16 h (unoptimized). The crude reaction mixture subsequently was dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 ml) and poured onto brine (10 ml). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 ml). The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by use of column chromatography over alumina or silica.

General catalytic procedure using methyl or dimethylamine (GPG)

Unless specified otherwise in the text, C1 (17.2 mg, 0.025 mmol, 5 mol%), NaOtBu (72.3 mg, 0.75 mmol, 1.5 equiv) and aryl (pseudo)halide (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv), followed by the addition of amine (2 M solution in THF, 1.75 ml, 3.5 mmol, 7.0 equiv) were added to a screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar. The vial was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum, was removed from the glovebox and placed in a temperature-controlled aluminum heating block set at the specified temperature, and was allowed to react under the influence of magnetic stirring for 16 h (unoptimized). The crude reaction mixture subsequently was dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 ml) and poured onto brine (10 ml). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 ml). The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by use of column chromatography over alumina or silica.

General catalytic procedure for aryl mesylates and primary amines (GPH)

Unless specified otherwise in the text, C1 (17.2 mg, 0.025 mmol 5 mol%), K3PO4 (636.8 mg, 3 mmol, 6.0 equiv), aryl mesylate (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv), amine (0.55 mmol, 1.1 equiv) and CPME (2.0 ml) were added to a screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar. The vial was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum, was removed from the glovebox and placed in a temperature-controlled aluminum heating block set at 110 °C, and was allowed to react under the influence of magnetic stirring for 16 h (unoptimized). The crude reaction mixture subsequently was dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 ml) and poured onto brine (10 ml). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 ml). The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by use of column chromatography over alumina or silica.

General catalytic procedure using carbazole or indole (GPI)

Unless specified otherwise in the text, C1 (13.8 mg, 0.02 mmol, 10 mol%), NaOtBu (57.6 mg, 0.60 mmol, 3.0 equiv), aryl halide (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), amine (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and 1,4-dioxane (2.0 ml) were added to a screw-capped vial containing a magnetic stir bar. The vial was sealed with a cap containing a PTFE septum, was removed from the glovebox and placed in a temperature-controlled aluminum heating block set at 110 °C, and was allowed to react under the influence of magnetic stirring for 16 h (unoptimized). The crude reaction mixture was dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 ml) and poured onto brine (10 ml). The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 ml). The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by use of preparatory silica TLC.

Room-temperature gram-scale synthesis of 2d

Following GPA, C1 (2 mol%, 0.42 mmol, 290 mg), 1-chloronapthalene (1 equiv, 21 mmol, 2.85 ml), NaOtBu (2 equiv, 42 mmol, 4.03 g), ammonia (0.5M in dioxane, 3 equiv, 63 mmol, 126 ml) and toluene (224 ml) were added to an oven dried 500 ml round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar. The reaction flask was sealed with a septum and stirring was initiated at room temperature. After 16 h (unoptimized), the solvent was removed with the aid of a rotary evaporator. The crude residue was dissolved in EtOAc (150 ml), washed with distilled water (2 × 150 ml) and once with brine (150 ml). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated with the aid of a rotary evaporator. The crude material was purified via automated column chromatography using a EtOAc:hexanes gradient 0–40% EtOAc, giving 2d (2.285 g, 76% yield).

Room-temperature gram-scale synthesis of 4a

Following GPF, C1 (3 mol%, 0.35 mmol, 241 mg), 1-chloronaphthalene (1 equiv, 11.7 mmol, 1.60 ml), octylamine (1.1 equiv, 12.9 mmol, 2.13 ml), NaOtBu (1.5 equiv, 17.6 mmol, 1.69 g) and toluene (120 ml) were added to an oven dried 250 round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar. The reaction flask was sealed with a septum and stirring was initiated at room temperature. After 16 h (unoptimized), the solvent was removed with the aid of a rotary evaporator. The crude residue was dissolved in EtOAc (150 ml), washed with distilled water (2 × 150 ml) and once with brine (150 ml). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated with the aid of a rotary evaporator. The crude material was purified via automated column chromatography using a EtOAc:hexanes gradient 0–20% EtOAc, giving 4a (2.703 g, 90% yield).

Crystallographic solution and refinement details

Crystallographic data for C1·0.5C5H12·0.5C4H8O and [(L1)NiCl2]·0.5CH2Cl2 were obtained at −100(±2) °C on a Bruker PLATFORM or D8/APEX II CCD diffractometer using graphite-monochromated Mo Kα (λ=0.71073 Å) radiation, employing samples that were mounted in inert oil and transferred to a cold gas stream on the diffractometer. Programmes for diffractometer operation, data collection and data reduction (including SAINT) were supplied by Bruker. Gaussian integration (face-indexed) was employed as the absorption correction method for C1, whereas multi-scan (TWINABS) was employed for (L1)NiCl2. The structure of C1 was solved by use of intrinsic phasing methods, whereas (L1)NiCl2 was solved by use of a Patterson/structure expansion; both were refined by use of full-matrix least-squares procedures (on F2) with R1 based on Fo2⩾2σ(Fo2) and wR2 based on Fo2⩾–3σ(Fo2). In the case of C1, attempts to refine peaks of residual electron density as disordered or partial-occupancy solvent pentane and/or tetrahydrofuran oxygen or carbon atoms were unsuccessful. The data were corrected for disordered electron density through use of the SQUEEZE procedure as implemented in PLATON. A total solvent-accessible void volume of 1,666 Å3 with a total electron count of 323 (consistent with 4 molecules of solvent pentane and 4 molecules of tetrahydrofuran, or 0.5 molecules each of pentane and tetrahydrofuran per formula unit of the Ni complex) was found in the unit cell. Positional disorder that was observed in the Ni-bound ortho-tolyl fragment during the solution and refinement of C1 was modelled in a satisfactory manner (80:20 occupancy ratio); only the larger of these is discussed in the text. In the case of (L1)NiCl2, the crystal used for data collection was found to display non-merohedral twinning. Both components of the twin were indexed with the programme CELL_NOW (Bruker AXS Inc., 2004). The second twin component can be related to the first component by 180° rotation about the [−0.2 −0.25 1] axis in real space and about the [0 0 1] axis in reciprocal space. Integrated intensities for the reflections from the two components were written into a SHELXL-2014 HKLF 5 reflection file with the data integration programme SAINT (version 8.34A), using all reflection data (exactly overlapped, partially overlapped and non-overlapped). The refined value of the twin fraction (SHELXL-2014 BASF parameter) was 0.4855(13). Furthermore, in the case of (L1)NiCl2 attempts to refine peaks of residual electron density as disordered or partial-occupancy solvent dichloromethane chlorine or carbon atoms were unsuccessful. The data were corrected for disordered electron density through use of the SQUEEZE procedure as implemented in PLATON. A total solvent-accessible void volume of 156.7 Å3 with a total electron count of 39 (consistent with one molecule of solvent dichloromethane, or one-half molecule of CH2Cl2 per formula unit of the Ni complex molecule) was found in the unit cell. Anisotropic displacement parameters were employed for all the non-hydrogen atoms. In all cases, non-hydrogen atoms are represented by Gaussian ellipsoids at the 30% probability level.

Additional information

Accession codes: The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1403891-1403892. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

How to cite this article: Lavoie, C. M. et al. Challenging nickel-catalysed amine arylations enabled by tailored ancillary ligand design. Nat. Commun. 7:11073 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11073 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-142, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada under the Discovery Grant award RGPIN-2014-04807. C.M.L. and P.M.M. thank the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada for Postgraduate Scholarships. N.L.R.-L. acknowledges receipt of a Nova Scotia Graduate Scholarship. Dalhousie University is also thanked for financial support of this work. We thank Cytec Industries for the gift of CgPH. S. Crawford, S. Pettipas and E. Cook are thanked for preliminary ligand syntheses, and C. Wiethan is thanked for helpful discussions. Dr M. Lumsden and Mr X. Feng (Dalhousie) are thanked for on-going technical assistance in the acquisition of nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectrometric data.

Footnotes

Dalhousie University has filed patents on the ligands/pre-catalysts used in this work, from which royalty payments may be derived.

Author contributions M.S. conceived of the ligand/pre-catalyst design and reactivity applications. C.M.L., P.M.M., N.L.R.-L., R.S.S., A.B. and M.S. designed the research. C.M.L., P.M.M., N.L.R.-L., R.S.S., A.B., A.J.C., and B.K.V.H. performed the synthetic experiments. R.M. and M.J.F. conducted the crystallographic analyses. M.S. drafted the manuscript, and all authors commented on the final draft of the manuscript and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data.

References

- Crawley M. L. & Trost B. M. Applications of Transition Metal Catalysis in Drug Discovery and Development: An Industrial Perspective John Wiley & Sons (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Louie J. & Hartwig J. F. Palladium-catalyzed synthesis of arylamines from aryl halides. Mechanistic studies lead to coupling in the absence of tin reagents. Tetrahedron Lett. 36, 3609–3612 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Guram A. S., Rennels R. A. & Buchwald S. L. A simple catalytic method for the conversion of aryl bromides to arylamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 34, 1348–1350 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig J. F. Evolution of a fourth generation catalyst for the amination and thioetherification of aryl halides. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1534–1544 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surry D. S. & Buchwald S. L. Biaryl phosphane ligands in palladium-catalyzed amination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 6338–6361 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemen G. S. & Wolfe J. P. Palladium-catalyzed sp2 C–N bond forming reactions: Recent developments and applications. Top. Organomet. Chem. 46, 1–54 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T. W., Campbell I. B. & Macdonald S. J. Factors determining the selection of organic reactions by medicinal chemists and the use of these reactions in arrays (small focused libraries). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 8082–8091 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughley S. D. & Jordan A. M. The medicinal chemist's toolbox: An analysis of reactions used in the pursuit of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 54, 3451–3479 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busacca C. A., Fandrick D. R., Song J. J. & Senanayake C. H. The growing impact of catalysis in the pharmaceutical industry. Adv. Synth. Catal. 353, 1825–1864 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Grushin V. V. & Alper H. Transformations of chloroarenes, catalyzed by transition-metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 94, 1047–1062 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Littke A. F. & Fu G. C. Palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions of aryl chlorides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 4176–4211 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christmann U. & Vilar R. Monoligated palladium species as catalysts in cross-coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 366–374 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig J. F. Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis Univ. Science Books (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Bullock R. M. Catalysis Without Precious Metals Wiley-VCH (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fan M. Y., Zhou W., Jiang Y. W. & Ma D. W. Assembly of primary (hetero)arylamines via Cul/oxalic diamide-catalyzed coupling of aryl chlorides and ammonia. Org. Lett. 17, 5934–5937 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Fan M. G., Yin J. L., Jiang Y. W. & Ma D. W. CuI/oxalic diamide catalyzed coupling reaction of (hetero)aryl chlorides and amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11942–11945 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier F. & Taillefer M. Copper-catalyzed C(aryl)–N bond formation. Top. Organomet. Chem. 46, 173–204 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B. M. et al. Nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings involving carbon-oxygen bonds. Chem. Rev. 111, 1346–1416 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana R., Pathak T. P. & Sigman M. S. Advances in transition metal (Pd,Ni,Fe)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions using alkyl-organometallics as reaction partners. Chem. Rev. 111, 1417–1492 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesganaw T. & Garg N. K. Ni- and Fe-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of phenol derivatives. Org. Process Res. Dev. 17, 29–39 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J. Organonickel Chemistry. in Organometallics in Synthesis: Fourth Manual ed. Lipshutz B. H. 319–428Wiley (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Tasker S. Z., Standley E. A. & Jamison T. F. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 509, 299–309 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananikov V. P. Nickel: The ‘spirited horse' of transition metal catalysis. ACS Catal. 5, 1964–1971 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J. P. & Buchwald S. L. Nickel-catalyzed amination of aryl chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 6054–6058 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Camasso N. M. & Sanford M. S. Design, synthesis, and carbon-heteroatom coupling reactions of organometallic nickel(IV) complexes. Science 347, 1218–1220 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesganaw T. et al. Nickel-catalyzed amination of aryl carbamates and sequential site-selective cross-couplings. Chem. Sci. 2, 1766–1771 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S., Green R. A. & Hartwig J. F. Controlling first-row catalysts: amination of aryl and heteroaryl chlorides and bromides with primary aliphatic amines catalyzed by a BINAP-ligated single-component Ni(0) complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 1617–1627 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R. A. & Hartwig J. F. Nickel-catalyzed amination of aryl chlorides with ammonia or ammonium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3768–3772 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C.-Y., Cao X. & Yang L.-M. Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of diarylamines with haloarenes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 3922–3925 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N. H., Teverovskiy G. & Buchwald S. L. Development of an air-stable nickel precatalyst for the amination of aryl chlorides, sulfamates, mesylates, and triflates. Org. Lett. 16, 220–223 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. R., Nelson D. J., Meiries S., Slawin A. M. Z. & Nolan S. P. Efficient C-N and C-S bond formation using the highly active [Ni(allyl)Cl(IPr*OMe)] precatalyst. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 3127–3131 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Nathel N. F. F., Kim J., Hie L. N., Jiang X. Y. & Garg N. K. Nickel-catalyzed amination of aryl chlorides and sulfamates in 2-methyl-THF. ACS Catal. 4, 3289–3293 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias M. J. et al. Synthesis, structural characterization, and catalytic activity of (IPr)Ni(styrene)2 in the amination of aryl tosylates. Organometallics 31, 6312–6316 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Manolikakes G., Gavryushin A. & Knochel P. An efficient silane-promoted nickel-catalyzed amination of aryl and heteroaryl chlorides. J. Org. Chem. 73, 1429–1434 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidai M., Kashiwagi T., Ikeuchi T. & Uchida Y. Oxidative additions to nickel(0). Preparation and properties of a new series of arylnickel(II) complexes. J. Organometal. Chem. 30, 279–282 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Morvillo A. & Turco A. Reactions of organic halides and cyanides with bis(tricyclohexylphosphine)nickel(0). J. Organomet. Chem. 208, 103–113 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Pringle P. G. & Smith M. B. in Phosphorus(III) Ligands in Homogeneous Catalysis: Design and Synthesis eds Kamer P. C. J., van Leeuwen P.W.N.M. 391–404John Wiley & Sons Ltd. (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Adjabeng G. et al. Novel class of tertiary phosphine ligands based on a phospha-adamantane framework and use in the Suzuki cross-coupling reactions of aryl halides under mild conditions. Org. Lett. 5, 953–955 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerristma D., Brenstrum T., McNulty J. & Capretta A. Phospha-adamantanes as ligands for organopalladium chemistry. Aminations of aryl halides. Tetrahedron Lett. 45, 8319–8321 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Cao H., Robertson A. & Alper H. Synthesis of dibenzo[b,f][1,4]oxazepin-11(10H)-ones via intramolecular cyclocarbonylation reactions using PdI2/Cytop 292 as the catalytic system. J. Org. Chem. 75, 6297–6299 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhel I. S. et al. Cage phosphinites: ligands for efficient nickel-catalyzed hydrocyanation of 3-pentenenitrile. Organometallics 30, 974–985 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Appl M. Ammonia: Principles and Industrial Practice Wiley-VCH (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Klinkenberg J. L. & Hartwig J. F. Catalytic organometallic reactions of ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 86–95 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stradiotto M. in New Trends in Cross-Coupling: Theory and Application (ed. Colacot T. J. 228–253Royal Society of Chemistry (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Borzenko A. et al. Nickel-catalyzed monoarylation of ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3773–3777 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q. L. & Hartwig J. F. Palladium-catalyzed coupling of ammonia and lithium amide with aryl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 10028–10029 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo G. D. & Hartwig J. F. Palladium-catalyzed coupling of ammonia with aryl chlorides, bromides, iodides, and sulfonates: A general method for the preparation of primary arylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 11049–11061 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren R. J., Peters B. D., Alsabeh P. G. & Stradiotto M. A P,N-ligand for palladium-catalyzed ammonia arylation: Coupling of deactivated aryl chlorides, chemoselective arylations, and room temperature reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4071–4074 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford S. M., Lavery C. B. & Stradiotto M. BippyPhos: a single ligand with unprecedented scope in the Buchwald-Hartwig amination of (hetero) aryl chlorides. Chem. Eur. J 19, 16760–16771 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshaghani M. et al. Highly efficient Suzuki coupling using moderately bulky tolylphosphine ligands. J. Mol. Catal. A 273, 310–315 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Tasker S. Z. & Jamison T. F. Highly regioselective indoline synthesis under nickel/photoredox dual catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9531–9534 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley E. A., Smith S. J., Muller P. & Jamison T. F. A broadly applicable strategy for entry into homogeneous nickel(0) catalysts from air-stable nickel(II) complexes. Organometallics 33, 2012–2018 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley E. A. & Jamison T. F. Simplifying nickel(0) catalysis: an air-stable nickel precatalyst for the internally selective benzylation of terminal alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1585–1592 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albaneze-Walker J. et al. Imidazolylsulfonates: electrophilic partners in cross-coupling reactions. Org. Lett. 11, 1463–1466 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon U. et al. An improved synthesis of 3-aminoestrone. Tetrahedron Lett. 46, 7111–7115 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. C., Kelly D. P. & Murrell J. C. Microbial degradation of methanesulfonic acid: a missing link in the biogeochemical sulfur cycle. Nature 350, 627–628 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson M. C. ‘Greener' Friedel-Crafts acylations: A metal- and halogen-free methodology. Org. Lett. 13, 2232–2235 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsabeh P. G. & Stradiotto M. Addressing challenges in palladium-catalyzed cross-couplings of aryl mesylates: Monoarylation of ketones and primary alkyl amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 7242–7246 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagaw S., Rennels R. A. & Buchwald S. L. Palladium-catalyzed coupling of optically active amines with aryl bromides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 8451–8458 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Rull S. G., Blandez J. F., Fructos M. R., Belderrain T. R. & Nicasio M. C. C-N coupling of indoles and carbazoles with aromatic chlorides catalyzed by a single-component NHC-nickel(0) precursor. Adv. Synth. Catal. 357, 907–911 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Zhang Y. & Ding X. H. Synthesis, structure, and catalytic behavior of a PSiP pincer-type iridium(III) complex. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 14, 1306–1310 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-142, Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References