Abstract

Oceanic islands of volcanic origin provide useful templates for the study of evolution because they are subjected to recurrent perturbations that generate steep environmental gradients that may promote adaptation. Here we combine population genetic data from nuclear genes with the analysis of environmental variation and phenotypic data from common gardens to disentangle the confounding effects of demography and selection to identify the factors of importance for the evolution of the insular pine P. canariensis. Eight nuclear genes were partially sequenced in a survey covering the entire species range, and phenotypic traits were measured in four common gardens from contrasting environments. The explanatory power of population substrate age and environmental indices were assessed against molecular and phenotypic diversity estimates. In addition, neutral genetic variability (FST) and the genetic differentiation of phenotypic variation (QST) were compared in order to identify the evolutionary forces acting on these traits. Two key factors in the evolution of the species were identified: (1) recurrent volcanic activity has left an imprint in the genetic diversity of the nuclear genes; (2) aridity in southern slopes promotes local adaptation in the driest localities of P. canariensis, despite high levels of gene flow among populations.

Introduction

Discerning the effects of demography and selection on the evolution of organisms has been a key research goal in population genetics since the development of the neutral theory of molecular evolution (Kimura, 1968). One way to demonstrate the action of selection and thus local adaptation is to test for clinal genetic variation along environmental gradients (Grivet et al., 2011; Mosca et al., 2012). Genetic patterns of local adaptation can be detected by identifying correlations between patterns of allele frequencies and environmental variables, which can act as selective agents promoting natural selection (Hancock et al., 2010). Robust signatures of local adaptation can also be estimated from the association of environmental variables with phenotypic characters obtained from common gardens, or with non-neutral coding regions of candidate genes. The argument for selection becomes particularly strong if a correlation can also be shown between the phenotype/genotype of interest (for example, time of bud set) and a measure of fitness (for example, number of surviving offspring; Hancock and Di Rienzo, 2008).

However, detecting environmental associations of genotypes and phenotypes depends on the spatial scale examined, and the associations have to be controlled for clines generated by neutral processes (for example, Hancock et al., 2008; Coop et al., 2010). Patterns of variation in neutrally evolving genomic regions are mainly influenced by the demographic history of a population.

Oceanic islands have long been recognized as natural laboratories for the study of evolutionary processes (Emerson, 2002). The volcanic origin of oceanic archipelagos generates extremely heterogeneous environments that may promote diversification of organisms through adaptive radiation (Schluter, 2000). In such landscapes, environmental conditions can drastically vary among adjacent localities and steep environmental gradients can be generated, potentially shaping the distribution of genetic diversity across populations (Savolainen et al., 2007). Classical population genetics theory predicts that heterogeneous environments can selectively maintain more variation within populations of the same species than non-heterogeneous environments (Levene, 1953; Dempster, 1955; Hedrick, 2006). However, although volcanism has been invoked as one of the main factors driving the evolution of organisms inhabiting oceanic islands (Juan et al., 2000), few studies provide apparent demographic or selective signatures of volcanic activity on genetic diversity (for example, bottlenecks or local adaptation to newly created ecological niches) of plant species.

The Canary Islands form an archipelago subjected to active volcanism since at least 20.6 My BP (Carracedo et al., 1998). The intensity and recurrence of volcanic events vary widely among and within islands (Juan et al., 2000; see references in Table 1) and, along with habitat heterogeneity and erosional events, are thought to be the main historical determinants of both the genetic diversity and ecology of the Canarian biota (Emerson, 2003; Navascués et al., 2006; de Nascimento et al., 2009; López de Heredia et al., 2010). Environmental clines are evident in the Canary Islands: (1) latitudinal clines are related to the exposure to the trade winds in the north-facing slopes that induces changes in humidity (Climent et al., 2002); (2) xericity varies to some extent along a longitudinal cline. The emergence of the islands followed an approximately E-W chronology since the c. 23 My BP uplift of Fuerteventura until the c. 1 My BP emergence of El Hierro (Table 1), with much intervening volcanic activity affecting the evolution of the Canarian biota. Recent volcanic activity has been reported in El Hierro (2012, La Restinga), La Palma (1971, Teneguía) and Tenerife (1909, Chinyero). In the last 500 years, no volcanic activity has been evidenced in Gran Canaria (Anguita et al., 2002), which has long been subjected to intensive erosive processes since the Roque Nublo eruptions c. 5.5-3.5 My BP.

Table 1. Geographical coordinates, sample size and chronostratigraphy of the substrate where Canary Island pine natural populations occur.

| Island (emergence date in My BP) | Code | Population | N | X_UTM | Y_UTM | Chronostratigraphy (My BP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gran Canaria (15) | Arg | Arguineguín | 26 | 434 941 | 3 077 536 | 11.77a (van den Bogaard and Schmincke 1998) |

| Gl | Gáldar | 3 | 439 376 | 3 099 201 | 0.0029 (Pérez Torrado, 1992) | |

| I | Inagua | 10 | 433 324 | 3 089 930 | 3.5 (Pérez Torrado, 1992) | |

| M | Mogán | 24 | 430 833 | 3 087 207 | 3.5 (Pérez Torrado, 1992) | |

| S | Barranco de Soria | 9 | 434 530 | 3 088 373 | 3.89 (van den Bogaard and Schmincke 1998) | |

| Sb | Tirajana | 24 | 441 718 | 3 089 646 | 3.69 (Guillou et al., 2004); 3.80 (Pérez-Torrado et al., 1995) | |

| T | Tamadaba | 24 | 431 978 | 3 103 714 | 3.5 (Pérez Torrado, 1992) | |

| Tenerife (12) | A | Arico | 24 | 347 929 | 3 123 062 | 0.69-0 (Carracedo, 1979) |

| Ana | Anaga | 24 | 373 332 | 3 159 843 | 5.4 (Carracedo, 1979), 4.5 (Ancochea et al., 1990) | |

| Ar | Arafo | 24 | 359 227 | 3 137 506 | 1.2 (Carracedo, 1979) | |

| Ch | Chío | 24 | 326 893 | 3 130 161 | 0.69-0 (Carracedo, 1979); 3620+-70 (Carracedo et al., 2003) | |

| Chir | Esperanza | 24 | 364 449 | 3 144 184 | 0-0.69 (Carracedo, 1979) | |

| G | Guancha | 24 | 338 033 | 3 136 348 | 0.69-0 (Carracedo, 1979) | |

| If | Ifonche | 24 | 334 324 | 3 113 839 | 1.2 (Carracedo, 1979) | |

| V | Vilaflor Alto | 24 | 336 661 | 3 119 757 | 0.69-0 (Carracedo, 1979) | |

| Vv | Vilaflor Bajo | 24 | 339 148 | 3 116 789 | 0.69-0 (Carracedo, 1979) | |

| La Gomera (9) | Ima | Imada | 5 | 278 913 | 3 108 478 | 8.6-7.8 (Ancochea et al., 2006, Llanes et al., 2009) |

| La Palma (2) | Csc | Fuencaliente | 24 | 220 535 | 3 163 050 | <0.0001 |

| Ctb | Caldera de Taburiente | 24 | 218 606 | 3 180 918 | 0.5 (Guillou et al., 1998, 2001; Carracedo et al., 2001) | |

| Fay | Punta Gorda | 24 | 210 305 | 3 186 846 | 0.531 (Guillou et al., 1998, 2001; Carracedo et al., 2001) | |

| Gar | Garafía | 24 | 219 189 | 3 189 233 | 1.65 (Guillou et al., 1998, 2001; Carracedo et al., 2001) | |

| Tag | Punta Llana | 24 | 225 438 | 3 181 505 | 0.5 (Guillou et al., 1998, 2001; Carracedo et al., 2001) | |

| Vp | El Paso | 25 | 222 932 | 3 174 530 | 0.659 (Guillou et al., 1998, 2001; Carracedo et al., 2001) | |

| El Hierro (1) | Hmo | Hoyo del Morcillo | 24 | 203 934 | 3 068 731 | 0.02 (Fúster et al., 1993, Gee et al., 2001) |

| Jul | El Julán | 24 | 199 963 | 3 069 239 | 0.02 (Fúster et al., 1993, Gee et al., 2001); Landslide >0.0133 (Carracedo et al., 1998); >0.015 (Carracedo et al., 2009) | |

| Tordesillas (Central Spain) | Ppa | Pinus pinea | 7 | 133 535 | 4 640 965 | n.a. |

| Commercial seed lot | Rox | Pinus roxburghii | 6 | — | — | n.a. |

The emergence date of the island is also indicated.

This date assumes that the Roque Nublo volcanic episode had no incidence in this population after Emerson et al., (2002), López de Heredia et al., (2010) and Anderson et al., (2009).

The Canary Island pine (Pinus canariensis Chr. Sm. Ex DC in Buch) has one of the most restricted distributions of any of the more of the 100 species of the genus Pinus. It is endemic to the Canary Islands, growing across contrasting habitats, from xeric conditions, with barely 300 mm of annual rain in the southwestern slopes, to mixed forest with the monteverde (that is, humid forest of laurel-like trees and shrubs) in northeastern slopes, influenced by the humid trade winds and with >1200 mm of annual rain. It has an altitudinal range from 200 to 2400 m a.s.l., and it is able to live in volcanic lava flows or pyroclastic deposits of salic nature (del Arco et al., 1992; Pérez de Paz et al., 1994; Climent et al., 2002). P. canariensis exhibits a remarkable propensity for colonization, particularly in open forests resulting from disturbed pinewoods (López de Heredia et al., 2010) or during the early stages of newly developed bare soils. The invasive character of the species results in extensive gene flow (Schiller et al., 1999; Gómez et al., 2003; Navascués et al., 2006; Vaxevanidou et al., 2006; Navascués and Emerson, 2007) and a lack of population genetic structure. The most accepted theory is that P. canariensis colonized individual islands as they emerged, following E-W colonization pattern (Navascués et al., 2006). However, local extinctions of the Gran Canarian populations due to catastrophic volcanic episodes are commonly acknowledged (Emerson, 2003; but see Anderson et al., 2009 for an alternative hypothesis), and W-E re-introductions are also possible.

The environmental heterogeneity and recurrent disturbance within the Canary Islands provide fertile ground for selective pressures, which may lead to long-term local adaptation (Savolainen et al., 2007). To disentangle the effect of neutral demographic and selective processes, the comparison of differentiation of neutral markers (FST; Wright, 1951) and quantitative trait divergence (QST; Spitze, 1993) has been widely used.

In this study we combine a population genetics approach using nuclear genes with the analysis of environmental variation and phenotypic trait data from field trials to disentangle the confounding effects of demography and selection for P. canariensis to identify the process of importance within the evolution of the species. Our first hypothesis is that the volcanic history of the Canarian archipelago leaves signatures of demographic processes linked to colonization within genes belonging to basal metabolic pathways. We assess this hypothesis using a coalescent approach to estimate effective population size and migration parameters. Our second hypothesis is that there will be signatures of local adaptation to aridity within P. canariensis. We assess this hypothesis by comparing neutral differentiation (FST) from putative neutral nuclear genes with phenotypic differentiation (QST) from phenotypic traits measured in four common gardens, and by testing for correlations of survival with climatic variables obtained from existing databases.

Materials and methods

Landscape characterization

Twenty-four populations of P. canariensis were chosen across the natural range of the species (Table 1). Altitude (Al) and UTM coordinates were scored for each population with a GPS (Trimble, GeoExplorer 2005 series). Chronostratigraphic dating of the lava flows or landslides supporting the pine forests were estimated as a proxy of substrate age (Sa) where populations occur, based on the available literature (see references in Table 1). Environmental variables of sampled populations were obtained from the Spanish network of meteorological stations AEMET and from the Canarian GIS database GRAFCAN (Del-Arco et al., 2006). These data included Al, average seasonal precipitation (Psp, Psum, Pau, Pwin), maximum precipitation in 24 h (Pmax24), mean ™, minimum (Tmin) and maximum temperature (Tmax), average seasonal temperature (Tsp, Tsum, Tau, Twin), annual temperature range (Tar), seasonal potential evapotranspiration (ETPsp, ETPsum, ETPau, ETPwin), solar radiation, ground frost frequency, potential soil erosion and length of drought period (LDP). Since many of these variables are strongly correlated, principal component analysis was used to reduce the number of dimensions for the whole set of climate variables with a Varimax rotation as implemented in the software STATISTICA 7.0 (StatSoft Inc., Oklahoma, USA). We examined the correlations between the principal component (PC) scores, the longitude, the latitude and Sa using the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

Sampling and sequencing

Only old mature trees with a diameter at breast height >50 cm were sampled, as they are considered to be older than the reforested plantations that have occurred from 1950 (del Arco et al., 1992; Pérez de Paz et al., 1994). Needles from 24–26 trees in 20 central populations and from 3–10 trees in four marginal populations were collected for DNA extraction and nuclear gene sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted from the needles using the Invisorb Spin Plant Mini Kit (STRATEC Molecular, Berlin, Germany). Amplicons from eight nuclear genes (Table 2) were obtained using previously published primer pairs transferred from P. pinaster (Grivet et al., 2011), P. sylvestris (Palmé et al., 2008), P. taeda (Brown et al., 2004) and from several species of subgenus Strobus (Tsutsui et al., 2009). Most genes are involved in basal metabolic pathways, such as lignin development (pal: phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene; cad: cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase gene; and CCoAOMT: caffeolyl CoA O-methyltransferase gene), photosynthesis (phy: phytocyanin gene; and GapCp: NAD-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene) or protein synthesis (rps10: ribosomal protein S10 gene). We also used two genes involved in drought response (lp3-3: water stress inducible protein 3 gene) and response to pathogen attack (eph: epoxide hydrolase gene). Primer information and amplification conditions are described in Supplementary Material Appendix 1, Supplementary Table A1. PCR products were directly sequenced in the Secugen S.L. sequencing service (Madrid, Spain).

Table 2. Description of the eight nuclear genes analysed in this study: GeneBank Acession No, Functional Category, total number of haploid sequences (N) and sequence length screened in the coding and non-coding regions (bp).

| Gene ID | GENEBANK Accession | Functional category | N |

Length screened (bp) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Coding region | Non-coding region | ||||

| rps10 | KF044382—KF044915 | Protein synthesis | 1068 | 392 | 298 | 94 |

| phy | KF044916—KF045449 | Blue copper proteins involved in electron transport | 1068 | 484 | 223 | 261 |

| pal | KF045450—KF045975 | Biosynthesis of phenylpropanoid compounds in lignin development | 1052 | 408 | 283 | 125 |

| lp3-3 | JX089129—JX089315; KF045976—KF046312 | Drought stress (belong to the ASR gene family) | 1048 | 404 | 237 | 167 |

| GapCp | KF046313—KF046837 | Photosynthetic Calvin cycle and cytosolic glycolysis. A role in root development | 1058 | 566 | 197 | 369 |

| eph | KF046838—KF047348 | Response to pathogen attack | 1050 | 642 | 332 | 310 |

| CCoAOMT | JX088938—JX089128; KF047349—KF047688 | Lignin biosynthesis (cell wall reinforcement) | 1062 | 511 | 264 | 247 |

| cad | JX088746—JX088937; KF047689—KF048027 | Lignin biosynthesis (end of the monolignol biosynthetic pathway) | 1064 | 412 | 301 | 111 |

Haplotype inference and genetic diversity

After Sanger sequencing, multiple sequence alignments were obtained using CLUSTALW on the BIOEDIT software (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/page2.html). Data for the eight nuclear loci were obtained from diploid individuals that often included multiple heterozygous positions. Potential biases in heterozygote detection or sequencing errors were checked visually. The program PHASE (Stephens et al., 2001) was used to estimate the two haplotypes in the case of heterozygous individuals. Molecular diversity statistics was computed for each nuclear gene region, population and island with DnaSAM 5.1 (Eckert et al., 2010a). Nucleotide diversity was estimated with both θπ (Nei, 1987), based on the average number of pairwise differences between sequences, and θW (Watterson, 1975), based on the number of segregating sites (S). Haplotype diversity was estimated using Hd statistics of Nei (1987). The frequency of rare haplotypes (γrare) within populations was scored as the sum of frequencies of those haplotypes with γ<0.1. The frequency of SNPs in the coding and non-coding regions of the genes was computed for further correlation with environmental variables (see below).

Departure from neutrality for each gene was evaluated considering all sequenced gametes in each amplicon, using as outgroup one sequence from P. pinea from a common garden in Central Spain. Tajima's D (Tajima, 1989), normalized H (Fay and Wu, 2000) and normalized E (Zeng et al., 2006) summary statistics was calculated to detect departures of the site frequency spectrum from neutral expectations. The significance of each test statistic was determined by comparing them with the distribution of 50 000 coalescent simulations under Wright's island model using the package ms (Hudson, 2002). Expectations of Tajima's D and normalized E are nearly zero in a constant-size population; significant negative values indicate a sudden expansion in population size, whereas significant positive values indicate processes such as a population subdivision or recent population bottlenecks. Conversely, normalized H is not sensitive to population expansions, and combining both statistics allows one to distinguish between population expansions and purifying selection.

In addition to site frequency spectrum statistics, we used the MFDM test (Li, 2011) to detect positive selection. This test has proven to be analytically and empirically free from the confounding effect of varying population size, including recent expansions. The test uses the maximum frequency of derived mutation in the sample to detect the presence of an unbalanced tree at a locus, which implies that a nearby locus may have experienced positive selection.

Population genetic structure and gene flow

Multilocus phased data were analysed with BAPS 6.0 (Corander et al., 2008), which implements a Bayesian clustering algorithm to estimate the number of genetic clusters. The program was ran 10 times for K=1–6 groups on the phased haplotypes across all genes. A Neighbor-Joining tree of the significant genetic clusters was constructed with the Nei divergence matrix provided as output with BAPS, and the frequencies of the inferred clusters within populations were mapped.

To assess partitioning of genetic variability between individuals, populations and islands, we used Arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier and Lischer, 2010) to perform hierarchical analyses of molecular variance for each locus and compute matrices of pairwise FST values between populations. We tested for isolation-by-distance (that is, the regular increase in genetic differentiation among individuals with geographical distance due to limited dispersal) with Mantel tests between the matrices of geographic distance and FST between populations for each gene (significance over 1000 permutations).

Unphased sequences were entered in MIGRATE 3.2.1. (Beerli, 2012) in order to jointly estimate the effective population size (□i) and the number of immigrants (Mij) and emigrants (Mji) for each population i using a maximum likelihood approach based on coalescence. An identical migration potential was assumed because the Mantel test showed no geographic structure (see Results). Migration parameters were scaled by mutation rates estimated from the data. We ran 10 short chains and three long chains with 4 × 105 sampled and 4 × 103 recorded genealogies, and discarded 25% of them as burn-in at the beginning of a chain. After assessing chain convergence, multiple chains were combined for final parameter estimates.

Environmental variation of genetic diversity

We examined the correlations between population diversity parameters (Hd and π), haplotype and single nucleotide length polymorphism (SNP) frequencies, PC scores, geographic variables and chronostratigraphic dating of the substrate where pine populations occurred to detect gradients of genetic diversity. Only SNPs with significant among-population changes in frequencies (>5%) were considered as being potentially subjected to selection. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used because it does not assume a linear relationship between the variables. The Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison tests was applied with a bootstrap of 10 000 iterations. In order to detect spurious correlations between SNPs and environmental variables that could be due to population history rather than selection, we used the Bayesian approach described by implemented in the program BayeScan (Foll and Gaggiotti, 2008). BayeScan assumes an island model of demography and scans for local adaptation in SNP frequency data by separately modelling a population-specific effect β and a locus-specific effect α that is sensitive to the strength of selection acting on a particular locus. For each SNP, BayeScan estimates the posterior distribution under neutrality (α=0) and separately allowing for selection (α≠0). The posterior odds ratio is a measure of support for the model of local adaptation relative to neutral demography and may be interpreted according to the scale of Jeffreys (1961). We used the following parameters: prior odds ratio=10; pilot runs=20; a burn-in of 50 000 iterations followed by 50 000 output iterations with a thinning interval of 10 resulting in 5000 iterations for posterior estimation; false discovery ratio is 1%.

Evidence for local adaptation

Evidence for local adaptation based on phenotypic measurements can be obtained by comparing neutral differentiation (FST) from neutral nuclear genes with phenotypic differentiation (QST) from traits measured in common gardens. Nineteen out of the 24 populations sampled were represented in four common gardens in the Canary Islands. Survival and growth parameters (height, basal diameter and frequency of second flush) were measured during the first 6 years after trial establishment (López et al., 2007). QST was calculated for phenotypic traits, partitioning the total additive genetic variance into the among-population (σB) and the within-population (σw) components:

|

where h2 is narrow sense heritability and n is the number of common gardens. There are no published values of heritability for P. canariensis; thus, we implemented a simulation procedure to evaluate the influence of heritability values in the range 0.2–0.8 on the QST.

The variance components—variance of the population (Vα), variance of the population × common garden interaction (Vαβ) and residual variance (Vɛ) for height and diameter—were estimated using the residual maximum likelihood option of the VARCOMP procedure in SAS 9.1 (SAS/STAT Software, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The variance components for survival and frequency of second flush were calculated with the glimmix macro of SAS assuming binomial error distribution and a logit-link function following the model:

where Yij stands for the value of the ith population (α) at the jth common garden (β) in the kth block (γ). The populations were arranged following a randomized complete block desing; μ is the overall mean and ɛ is the experimental error.

Confidence intervals and distribution for QST estimations were assessed with a parametric bootstrap procedure (1000 samples) outlined in Whitlock (2008) with replacement at the individual level within population. In addition, confidence intervals for FST were determined by bootstrapping over loci. For each bootstrap replicate, the mean FST value was calculated from the neutral loci sampled, and from that the predicted χ2 distribution of FST was determined from the Lewontin–Krakauer approach (Lewontin and Krakauer, 1973). QST was considered to be statistically different from FST when 95% confidence intervals of QST did not overlap 95% confidence intervals of FST (Sahli et al., 2008). The mean survival and growth values per population in the last year of measurement were calculated in the four common gardens to detect spatial and climate patterns of genetic differentiation using regression analyses.

Results

Landscape characterization

The chronostratigraphy of the sampling locations for P. canariensis showed significantly younger geological events than the accepted dates for the emergence of the islands (Table 1). The oldest substrates are located in the South of Gran Canaria (Arguineguin, 11.6 My BP), assuming that the lavae and pyroclastic emissions of the Roque Nublo volcanic episode (c. 5.5-3.5 My BP) did not cover the entire south of the island (Anderson et al., 2009). In Tenerife, the oldest substrates with pines are at the NE, in the region of the Anaga Massif (5.4-4.5 My BP). The remainder of the Tenerife pine populations occur in substrates that date back to ∼1.2 My BP, in areas of low Al, or in areas, associated with the Cañadas volcanic episode (c. 0.7 My BP). The few pines in La Gomera occur in old substrates of c. 8 My BP. La Palma and El Hierro are the youngest Canary Islands. La Palma has two types of substrates, 1.6 My BP in the North and <0.65 My BP corresponding to the collapse of the Caldera de Taburiente and historical volcanic activity. Recent active volcanism and landslides (>0.02 My BP) characterize the geology of El Hierro.

Climate data from available databases were summarized in three PCs that explained 84.9% of the variance of the complete data set (Supplementary Material Appendix 1, Supplementary Tables A2 and 3). PC1 (55.1%) was similar to an aridity index, with mild, wet climates at one end and dry, hot climates at the other. PC2 (20%) was positively related to Al, Tar, maximum temperatures (Tmax) and summer potential evapotranspiration (ETPsum) and was negative for all the measures of rainfall, Psp, Psum, Pau, Pwin, Tmin and ETPwin. PC3 (12%) reflected mainly solar radiation, Tsum and Tmax. The Sa was strongly correlated with longitude (ρ=0.86; P<0.001); therefore, we considered that they were redundant variables. PC1 was correlated with both latitudes (ρ=−0.61; P<0.01), evidencing the contrasting habitats in N and S slopes of the islands, and Sa (ρ=0.55; P<0.05), with the oldest locations being the most arid. PC2 was also correlated with latitude (ρ=0.55; P<0.05).

Haplotype estimation and genetic diversity

The total combined length of nuclear genome screened was 3819 bp, of which 1684 bp corresponded to introns and 2135 bp were in coding regions (Table 2). A total of 163 SNPs were identified, of which 30 exhibited significant variation in their frequencies among populations (Table 3). One hundred nine SNPs corresponded to silent mutations (synonymous substitutions and SNPs in non-coding positions), with 54 non-synonymous mutations. GapCp, eph and cad sequences showed indels at very low frequency and they were not considered in haplotype estimations.

Table 3. Summary of diversity indices and results of the neutrality tests for the entire set of Canary Island pine populations.

| Gene | N | θπ | θW | S | h | Hd (s.d.) | Nsyn | Silent | Tajima's D | normH | normE | MFDM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rps10 | 1068 | 0.003480 | 0.005406 | 17 | 16 | 0.609 (0.009) | 5 (0) | 11 (4) | −0.882 | 0.435 | −1.034 | n.s. |

| phy | 1068 | 0.000533 | 0.005747 | 21 | 25 | 0.227 (0.017) | 6 (0) | 15 (0) | −2.124*** | 0.120 | −1.835*** | n.s. |

| pal | 1052 | 0.004248 | 0.009078 | 23 | 39 | 0.653 (0.015) | 15 (4) | 9 (3) | −1.130 | −0.093 | −0.866 | n.s. |

| lp3-3 | 1048 | 0.005035 | 0.008526 | 17 | 24 | 0.653 (0.010) | 4 (0) | 13 (4) | −0.305 | 0.231 | −0.416 | n.s. |

| GapCp | 1058 | 0.002223 | 0.008006 | 17 | 21 | 0.563 (0.014) | 2 (0) | 14 (2) | −1.497* | 0.255 | −1.404* | n.s. |

| eph | 1050 | 0.002935 | 0.010227 | 34 | 43 | 0.597 (0.014) | 12 (1) | 27 (3) | −1.734*** | 0.137 | −1.561* | n.s. |

| CCoAOMT | 1062 | 0.004080 | 0.007239 | 14 | 25 | 0.592 (0.013) | 4 (0) | 11 ( (5) | −0.306 | −1.376 | 0.848 | 0.040 |

| cad | 1064 | 0.002371 | 0.005374 | 12 | 24 | 0.603 (0.016) | 2 (0) | 9 (4) | −0.900 | 0.541 | −1.107 | n.s. |

Abbreviations: h, number of haplotypes; Hd, haplotype diversity; N, number of haploid sequences; n.s., nonsignificant; Nsyn, number of non-synonymous SNPs; θπ, nucleotide diversity per site based on the average number of pairwise differences between sequences (Nei, 1987); θW, nucleotide diversity per site based on the number of segregating sites S (Watterson, 1975; Silent, number of synonymous and SNPs in non-coding positions (the number of SNPs with significant among-population changes in frequencies >5% is indicated in brackets); SNP, single nucleotide length polymorphism; Tajima's D (Tajima, 1989), normalized H (Fay and Wu, 2000) and normalized E (Zeng et al., 2006), neutrality test statistics; MFDM, significance of the MFDM test (Li, 2011).

***P<0.001; **P<0.01; *P<0.05.

After removing potentially biased sequences of low quality, a total of 1050–1068 phased haplotypes were inferred for each gene (total number of sequences=8470) covering the entire distribution of P. canariensis. Two haplotypes per gene per sampled tree were obtained in each population, resulting in 48–52 sequences per population per gene in the 21 densely sampled populations (Table 3). Whereas nucleotide diversity per site based on the number of segregating sites ranged between θW=0.005374 for cad and θW=0.010227 for eph, nucleotide diversity per site based on the average number of pairwise differences between sequences only varied between θπ=0.000533 for phy and θπ=0.005035 for lp3-3 (Table 3). As for the nucleotide diversity estimates, the number of haplotypes h and the haplotypic diversity Hd were variable between genes and populations (Table 3; Supplementary Material Appendix 1, Supplementary Tables A4–11). The gene with the highest number of haplotypes was eph (h=43) and the gene with the fewest haplotypes was rps10 (h=16). For all genes, with the exception of phy, two to three very frequent haplotypes and a variable number of rare haplotypes (γ<0.1) were scored in all populations (Supplementary Material Appendix 2, Supplementary Figures A1–8). The median joining networks (Supplementary Material Appendix 2, Supplementary Figures A1–8) were estimated independently for each gene.

Neutrality tests performed for gene sequences generated contrasting results depending on the method of choice (Table 3). Whereas Tajima's D and normalized E resulted in negative and significant values for phy (P<0.001), eph (P<0.001) and GapCp (P<0.05), normalized H was not significant for any gene, indicating a sudden expansion of P. canariensis size rather than purifying selection or recent selective sweeps for those genes. The MFDM test only resulted in significant deviation from neutrality for CCoAOMT (P<0.05; Table 3).

Population genetic structure and gene flow

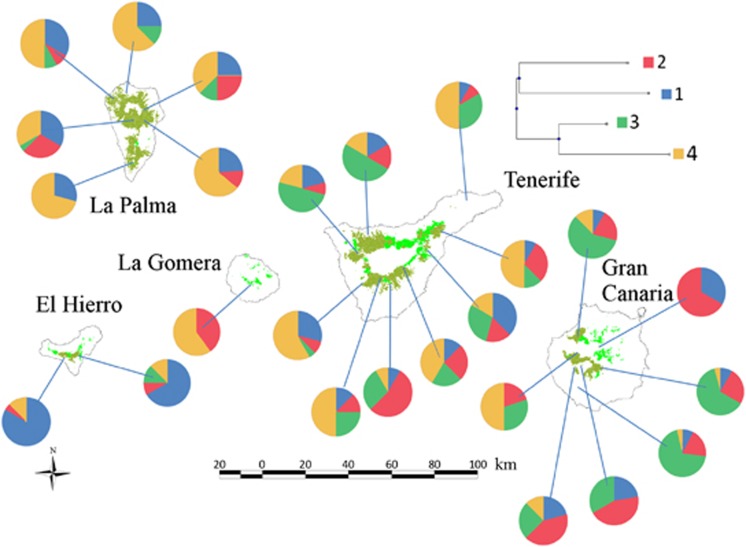

Mixture analysis across all genes with BAPS showed the presence of four genetic clusters that occur in all the islands (Figure 1), with some degrees of spatial structure. Cluster 1 was found predominantly in El Hierro but was also present in the other islands. Clusters 2 and 3 were more frequent in Gran Canaria and Tenerife than in La Palma and El Hierro. Cluster 4 was very infrequent in Gran Canaria.

Figure 1.

Neighbor-joining tree and map showing pie charts with the population frequencies of the four genetic clusters inferred with BAPS for Pinus canariensis.

Analyses of molecular variance for each gene showed very high within-population diversity (>88% of variation) and very low diversity among populations (<6% of variation). The percentage of genetic variation among islands ranged from 0.76% for eph to 8.14% for GapCp. This weak geographic structuring of genetic diversity is in agreement with the nonsignificant Mantel values between the matrices of pairwise FST and of spatial distances (P>0.3) and with the results of the MIGRATE software. The estimated migration parameters were very high among all populations (Mmean=195.4; s.d.=78.5), irrespective of their geographic distance. Effective population sizes were estimated to be higher in the more recent and less stable islands and showed some significant positive correlations with latitude (ρ=0.45; P<0.033). The complete migration matrix and effective population size estimates are in Supplementary Material Appendix 3, Supplementary Table A1.

Environmental and temporal variation of genetic diversity

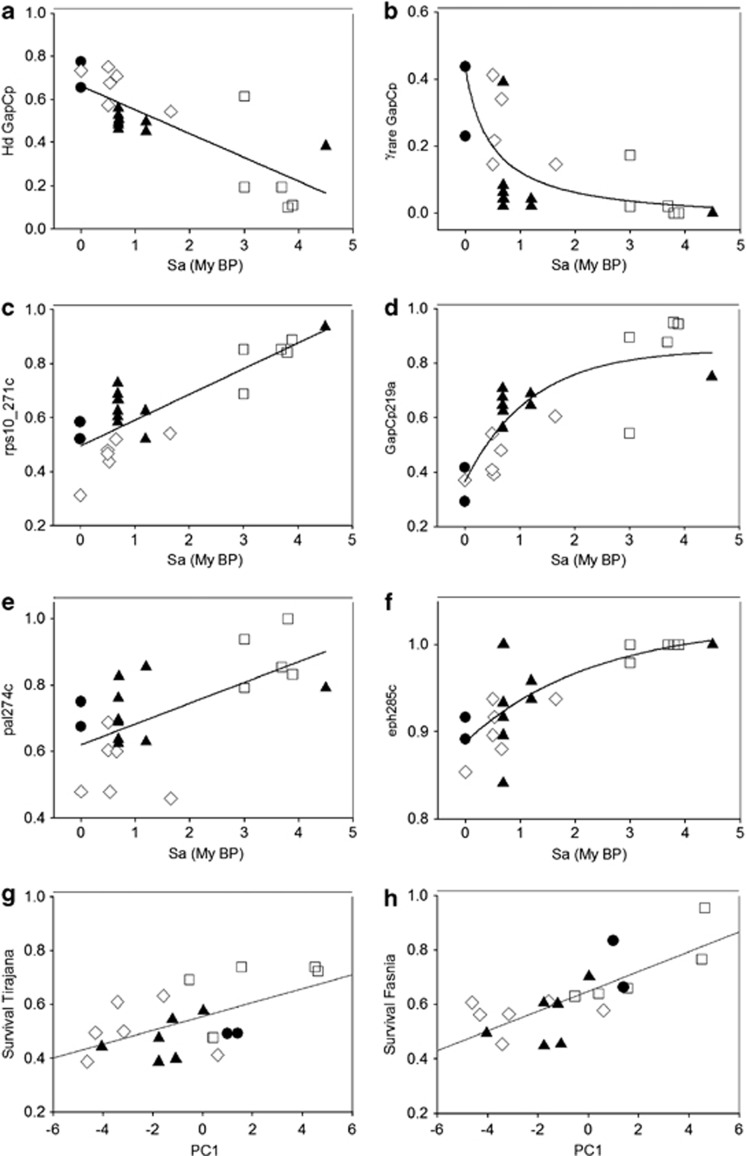

Strong negative correlations between Sa and both Hd and γrare were found for both GapCp (ρ=−0.83; P<0.0001; ρ=−0.77; P<0.0003; Figures 2a and b) and eph (ρ=−0.50; P<0.019; ρ=−0.53; P<0.012). For the other six genes, the Spearman Rank correlation coefficient between Sa and Hd was nonsignificant (ρ<0.50). Eleven SNPs in the coding region and 19 SNPs in the non-coding region showed significant among-population variation in frequency (>5%). The frequency of six SNPs showed highly significant Spearman's Rank correlation coefficients with Sa: rps10_271c (Figure 2c), rps10_327t, GapCp219a (Figure 2d) in the intron regions; and pal73c, pal274c (Figure 2e) and eph285c (Figure 2f) in the coding region. The SNPs rps10_271c, rps10_327t, pal73c and pal274c also showed significant correlations (ρ>0.50) with the environmental component related to aridity PC1. Two SNPs (cad203g and cad248t) were found to be correlated with the environmental component PC3 (ρ>0.60). The BayeScan analysis identified four SNPs (pal31, pal355, lp3-3_107 and lp3-3_108) showing negative values of α, suggesting that they were potentially subjected to balancing or purifying selection. However, none of these SNPs showed significant correlations with environmental components or Sa. Therefore, we cannot discard the null hypothesis of historical demographic events, such as genetic drift associated with bottlenecks, driving the geographic structure of genetic diversity.

Figure 2.

(a–f) Predicted and observed patterns of variation of haplotype diversity Hd (a), frequency of rare haplotypes γrare (b) and frequencies of SNPs from genes rps10 (c), GapCp (d), pal (e) and eph (f) with the age of the substrate (Sa). (g–h) Predicted and observed patterns of clinal variation of survival with aridity PC1 estimated in the common gardens of Tirajana (g) and Fasnia (h), respectively. Open squares: Gran Canaria; Black triangles: Tenerife; Open diamonds: La Palma; Black circles: El Hierro.

Evidence for local adaptation

Whereas selection and local adaptation processes could not be inferred from landscape analyses of nuclear genetic variation, growth and survival were found to differ among populations in the drier common gardens (Supplementary Material Appendix 1, Supplementary Table A12). QST values ranged between 0.077 (0.12; P<0.001) for height and 0.225 (0.08; P<0.001) for survival considering the narrow sense heritability of 0.2. QST and FST values did not differ significantly for height, diameter and frequency of second flush; however, for survival the average QST value was significantly higher than FST in the range (0.2–0.8) of heritability, suggesting that populations displayed more differentiation than would be expected by drift alone.

The correlation analysis with environmental traits revealed strong, significant clines in the drier common gardens: xeric populations showed higher survival rates than populations from wet locations (P<0.001; Figures 2g and h). Moreover, height in the driest common garden increased significantly with aridity of the population.

Discussion

The combined use of nuclear gene sequences and phenotypic measures from common gardens offers new insights on the evolution and ecology of P. canariensis on the Canary Islands. The analysis of nuclear genes from many individuals per population across the entire range of the species has revealed the effect of geological events on the E-W directional colonization of the islands as new substrates were generated by volcanic activity or landslides. Phenotypic measures in common gardens have evidenced local adaptation in response to aridity, despite the high levels of gene flow among populations.

Evolution of P. canariensis is driven by volcanic activity

The volcanism responsible for the formation of islands has had a major impact on the genetic diversity and demography of P. canariensis, as shown by the fossil record and patterns of variation among nuclear genes. The oldest pine fossils in the Canarian Archipelago have been found as early as 13.5 My BP in Tirajana, soon after the emergence of Gran Canaria (García Talavera et al., 1995). Pleistocene fossils have been found in La Palma (1.2 My BP), suggesting quick colonization after the island emergence, and in Tenerife −0.6 My BP, roughly at the time of the Phase III of the central Cañadas Edifice (Ancochea Soto et al., 1999). The correlations between diversity parameters and haplotype/SNP frequencies with Sa suggest that the volcanic history of the Canary Archipelago is a major factor of the evolution of P. canariensis. The effective population size and both haplotype diversity and the frequency of rare haplotypes for the genes that showed correlations with Sa (GapCp and eph) were higher in the youngest (La Palma, El Hierro and Tenerife) than in the oldest substrates of the Canary Islands (Gran Canaria). However, a statistical association between environmental heterogeneity and genetic polymorphism does not necessarily mean that the polymorphism is adaptive (Pamilo, 1988). Our results with the MFDM test (Li, 2011) revealed that indirect demographic effects, such as a probable bottleneck produced by the catastrophic volcanic episodes of the Roque Nublo eruptive period (c. 5.5–3.5 My BP), may have shaped observed genetic diversity patterns in P. canariensis. Since the Roque Nublo episode, Gran Canaria has been more stable in terms of volcanic activity (Anguita et al., 2002); however, the impact of human activity and xericity on pine populations is higher than in the other islands (López de Heredia et al., 2010). High pollen and seed dispersal ability allow for a fast recovery of the genetic diversity of P. canariensis populations after volcanic disturbance (Navascués and Emerson, 2007). Moreover, recent dendroecological analysis of buried trunks in the volcano of San Juan in La Palma points to the possibility of the maintenance local populations close to an emission cone, given the ability to re-sprout when the depth of the pyroclast layer does not completely bury the trees (Rodríguez Martín et al., 2013).

Despite the small area covered by the species, BAPS has shown that there is not a single genetic pool but four genetic groups that are not clearly geographically structured. A similar pattern was also found for nuclear gene analysis in P. sylvestris in Scotland (Wachowiak et al., 2011), suggesting that admixture of populations with different demographic histories has played a role in shaping current genetic diversity patterns.

In recent times, P. canariensis has undergone population expansion processes. Using chloroplast microsatellites, Navascués et al. (2006) estimated the expansion times of several P. canariensis populations using as calibration points the time of emergence of the islands and the time of expansions of a pine specialist endemic weevil Brachyderes rugatus (<2.6 My BP; Emerson et al., 2000, 2006). Consistently, our comparison of Tajima's D test and normalized H has shown evidence of recent range expansions. P. canariensis is a colonizing species with high dispersal potential (López de Heredia et al., 2010) that invades poor soils—that is, salic volcanic substrates with very dry environments that arboreal angiosperms are unable to inhabit (Aboal et al., 2000) and where competition is very low. The reduction of the laurisilva forests (Parsons, 1981); the disappearance of the thermophilous forest (de Nascimento et al., 2009) and the gradual rise of the timberline (Leuschner, 1996) enable pine to colonize ecological niches that formerly could not be occupied (VVAA, 2011).

Local adaptation to arid environments despite high levels of gene flow

Weak patterns of population structure and high historical gene flow estimates between distant populations were found for P. canariensis, consistent with high contemporary gene flow by pollen and seed (López de Heredia et al., 2010) and for other coniferous species (González-Martínez et al., 2006; Eckert et al., 2010b). Molecular studies based on chloroplast DNA variation have revealed that gene flow is significant along elevational transects (Navascués and Emerson, 2007) but that some level of genetic differentiation, suggested by the presence of private chloroplast DNA haplotypes, was maintained among valleys (Gómez et al., 2003). Nuclear genes have shown the same pattern of one or two very frequent haplotypes and many private haplotypes in each population, resulting in equally very high migration parameter estimates between both close and distant populations. In addition, analyses of molecular variance revealed that only a small amount of genetic diversity was related to differences among islands, suggesting high gene flow at a regional scale. Despite that some bias may exist in gene flow estimation due to the lack of mutation-drift-migration equilibrium for P. canariensis, results are consistent with the high local seed and pollen dispersal for the species (López de Heredia et al., 2010). Despite gene flow being commonly viewed as a homogenizing force for genomic variation, long distance gene flow can also promote adaptive evolution in novel environments by increasing genetic variation for fitness (Kremer et al., 2012). As genetic variance increases, local populations are better able to respond to local selection (Barton, 2001), and this would seem to be a plausible explanation for P. canariensis.

A recent analysis of hydraulic traits and three of the genes used in the present study (CCoAOMT, lp3-3 and cad) among eight populations growing in two common gardens has demonstrated that divergent selection is operating on hydraulic traits, particularly in vulnerability to cavitation, in response to aridity (López et al., 2013). Other traits, such as heteroblasty (Climent et al., 2006) or biomass allocation (López et al., 2009), have also shown some degrees of correlation with xericity. In the present study, we provide additional support for local adaptation to arid conditions by the analysis of survival across 19 populations tested in four common gardens and by testing the neutrality of eight nuclear genes in order to perform comparisons between FST and QST values.

Neutrality tests did not reveal deviation from neutral patterns that could be attributed to selection. This lack of signature of selection is not unexpected because most of the analysed genes code for basal metabolic pathways, such as lignin development in the cell wall formation (pal, CCoAOMT, cad), photosynthesis (phy and GapCp) or protein synthesis (rps10). We have already shown that the correlation of some nuclear genetic diversity patterns with the climatic and chronostratigraphic variables tested in this study is compatible with demographic events associated with historical events, particularly with volcanic episodes. An alternative hypothesis to explain the correlations between aridity and some of the SNP frequencies is genetic hitch-hiking—that is, positive directional selection operating at a single locus that is partially linked to a neutral polymorphism (Maynard Smith and Haigh, 1974). It is noteworthy that two genes involved in the responses to drought (lp3-3) and lignin development showed two SNPs each, potentially subjected to balancing selection. These SNPs did not show any correlation with aridity gradients in agreement with the lack of selection evidence found for this candidate gene in the Mediterranean pines P. pinaster and P. halepensis (Grivet et al., 2011).

However, despite the lack of signatures of selection on the nuclear genes and the high gene flow levels, the correlation of survival with PC1 and the comparisons between phenotypic QST and neutral FST estimates evidence some degree of local adaptation for P. canariensis related to aridity. Survival was higher in the populations from arid environments than in those populations from mesic locations. Contemporary clinal variation in adaptive traits along environmental gradients shown in many tree species suggests that local adaptation can occur during rapid migration over just a few generations (Mimura and Aitken, 2007) and is inherent to the colonization process. It should be noted that because of climate changes and population movements over evolutionary time, the current values of climate variables may be only partially correlated with the long-term climatic conditions experienced by each population. Hence, it is very likely that the local adaptation processes that we have detected are due to recent climatic changes towards more xeric conditions (VVAA, 2011) or to the colonization of new habitats.

Perspectives in a global change scenario

We have demonstrated two key determinant variables in the ecology and evolution of P. canariensis: (1) volcanic activity and (2) aridity. Both factors are still operating in the Canary Islands. Volcanic activity has been recorded in Tenerife and La Palma in the last century and very recently in El Hierro. When the effects of such volcanic events are not overly destructive, P. canariensis is one of the plant species in the islands that benefits most, due to its resiliency and colonizing character. Interestingly, new ecological niches created by volcanic activity (that is, salic soils) are related to edaphic aridity because water from precipitation percolates. In these sites, P. canariensis is more competitive than other arboreal species in the Canary Islands.

The humid environment produced by the sea of clouds may mitigate the effect of edaphic drought in the northern slopes of the islands. However, in southern slopes at low Al, aridity has a major role. The ability of P. canariensis to locally adapt is essential for the maintenance of the species in those areas. Further research should be focused on the identification of candidate genes implied in the mechanisms to face the increasing xeric scenarios that will become more and more abundant in the near future in the Canary Islands (VVAA, 2011).

Data archiving

GenBank accession numbers for the P. canariensis gene sequences analyzed in the present manuscript are: KF044382-KF044915 (rps10), KF044916-KF045449 (phy), KF045450-KF045975 (pal), JX089129-JX089315; KF045976-KF046312 (lp3-3), KF046313-KF046837 (GapCp), KF046838-KF047348 (eph), JX088938-JX089128; KF047349-KF047688 (CCoAOMT), JX088746-JX088937; KF047689-KF048027 (cad). Survival and growth data from common garden experiments are available from the Dryad Digital Repository; doi:10.5061/dryad.j774r.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Canary Islands Government, the Cabildos of Tenerife and Gran Canaria and the National Park of Caldera de Taburiente for long-standing support in the study of Canary Island pine; and to Drs J Climent, SC González-Martínez, E García-del-Rey and A Soto for their help in sample collection. We also thank all people involved in the plantation and measurements of the common gardens. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science in the Project AGL2009-10606 (VULCAN).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Heredity website (http://www.nature.com/hdy)

Supplementary Material

References

- Aboal JR, Jiménez MS, Morales MS, Gil P. (2000). Effect of thinning on throughfall in Canary Islands pine forest—the role of fog. J Hydrol 238: 218–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ancochea E, Muster JM, Ibarrola E, Cendrero A, Coello J, Hernan F et al. (1990). Volcanic evolution of the island of Tenerife (Canary Islands) in the light of new K-Ar data. J Volcanol Geoth Res 44: 231–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ancochea Soto E, Huertas C, Cantagrel MJ, Coello J, Fúster JM, Arnaud N et al. (1999). Evolution of the Cañadas edifice and its implications for the origin of the Cañadas Caldera (Tenerife, Canary Islands). J Volcanol Geoth Res 88: 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ancochea E, Hernán F, Huertas MJ, Brändle JL, Herrera R. (2006). A new chronostratigraphical and evolutionary model for La Gomera: implications for the overall evolution of the Canarian Archipelago. J Volcanol Geoth Res 157: 271–293. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CL, Channing A, Zamuner AB. (2009). Life, death and fossilization on Gran Canaria-implications for Macaronesian biogeography and molecular dating. J Biogeograph 36: 2189–2201. [Google Scholar]

- Anguita F, Márquez A, Castiñeiras P, Hernán F. (2002) Los Volcanes de Canarias, Guía geológica e itinerarios. Ministerio de Fomento, IGN: Rueda, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Barton NH. (2001). Adaptation at the edge of a species' range. In: Silvertown J, Antonovics J (eds) Integrating Ecology and Evolution in a Spatial Context. Blackwell Sciences: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Beerli P. (2012) Migrate version 3.0—a maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimator of gene flow using the coalescent (2012) (http://popgen.sc.fsu.edu/Migrate-n.html).

- Brown GR, Gill GP, Kuntz RJ, Langley CH, Neale DB. (2004). Nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium in loblolly pine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 15255–15260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo JC. (1979) Paleomagnetismo e historia volcánica de Tenerife. Aula de Cultura, Cabildo Insular de Tenerife.

- Carracedo JC, Day S, Guillou H. (1998). Hotspot volcanism close to a passive continental margin: the Canary Islands. Geol Mag 135: 591–604. [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo JC, Rodríguez Badiola E, Guillou H, De La Nuez J, Pérez Torrado FJ. (2001). Geology and volcanology of La Palma and El Hierro, Western Canaries. Estud Geol 57: 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo JC, Paterne M, Guillou H, Pérez Torrado FJ, Paris R, Rodríguez Badiola E et al. (2003). Dataciones radiométricas (14C y K/AR) del Teide y el Rift Noroeste, Tenerife, Islas Canarias. Estudios Geol 59: 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo JC, Pérez Torrado FJ, Paris R, Rodríguez Badiola E. (2009). Megadeslizamientos en las Islas Canarias. Enseñ Cienc Tierra 17: 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Climent J, Chambel MR, Pérez E, Gil L, Pardos J. (2002). Relationship between heartwood radius and early radial growth, tree age, and climate in Pinus canariensis. Can J Forest Res 32: 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Climent J, Chambel MR, López R, Mutke S, Alía R, Gil L. (2006). Population divergence for heteroblasty in the Canary Island pine (Pinus canariensis, Pinaceae). A J Bot 93: 840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop G, Witonsky D, Di Rienzo A, Pritchard JK. (2010). Using environmental correlations to identify loci underlying local adaptation. Genetics 185: 1411–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corander J, Marttinen P, Sirén J, Tang J. (2008). Enhanced Bayesian modelling in BAPS software for learning genetic structures of populations. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 539–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nascimento L, Willis KJ, Fernández-Palacios JM, Criado C, Whittaker RJ. (2009). The long-term ecology of the lost forests of La Laguna, Tenerife (Canary Islands). J Biogeogr 36: 499–514. [Google Scholar]

- del Arco MJ, Pérez de Paz PL, Rodríguez O, Salas M, Wildpret W. (1992) Atlas cartográfico de los pinares canarios: Tenerife, Viceconsejería de Medio Ambiente, Consejería de Política Territorial, Gobierno de Canarias, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain.

- Del-Arco M, Wildpret W, Pérez-de-Paz PL, Rodríguez-Delgado O, Acebes JR, García-Gallo A et al. (2006) Mapa de Vegetación de Canarias.— GRAFCAN. Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

- Dempster ER. (1955). Maintenance of heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 20: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert AJ, Liechty JD, Tearse BR, Pande B, Neale DB. (2010. a). DnaSAM: software to perform neutrality testing for large datasets with complex null models. Mol Ecol Resour 10: 542–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert AJ, van Heerwaarden J, Wegrzyn JL, Dana Nelson C, Ross-Ibarra J, González-Martínez SC et al. (2010. b). Patterns of population structure and environmental associations to aridity across the range of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L., Pinaceae). Genetics 185: 969–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson BC, Oromí P, Hewitt GM. (2000). Colonization and diversification of the species Brachyderes rugatus (Coleoptera) on the Canary Islands: evidence from mitochondrial DNA COII gene sequences. Evolution 54: 911–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson BC. (2002). Evolution on oceanic islands: molecular phylogenetic approaches to understanding pattern and process. Mol Ecol 15: 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson BC. (2003). Genes, geology and biodiversity: faunal and floral diversity on the island of Gran Canaria. Anim Biodiv Conserv 26: 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson BC, Forgie S, Goodacre S, Oromí P. (2006). Testing phylogeographic predictions on an active volcanic island: Brachyderes rugatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) on La Palma (Canary Islands). Mol Ecol 15: 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. (2010). Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour 10: 564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay C, Wu CI. (2000). Hitchhiking under positive Darwinian selection. Genetics 155: 1405–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foll M, Gaggiotti O. (2008). A genome-scan method to identify selected loci appropriate for both dominant and codominant markers: a Bayesian perspective. Genetics 180: 977–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fúster JM, Hernán F, Cendrero A, Coello J, Cantagrel JM, Ancochea E et al. (1993). Geocronología de la isla de El Hierro (Islas Canarias). Bol R Soc Esp Hist Nat Geol 88: 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- García Talavera F, Sánchez-Pinto L, Socorro S. (1995). Vegetales fósiles en el complejo traquítico-sienítico de Gran Canaria. Rev Acad Canar Cienc 7: 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gee MJR, Watts AB, Masson DG, Mitchell NC. (2001). Landslides and the evolution of El Hierro in the Canary Islands. Mar Geol 177: 271–293. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez MA, González-Martínez SC, Collada C, Climent J, Gil L. (2003). Complex population genetic structure in the endemic Canary Island pine revealed using chloroplast microsatellite markers. Theor Appl Genet 107: 1123–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Martínez SC, Ersoz E, Brown GR, Wheeler NC, Neale DB. (2006). DNA sequence variation and selection of tag singlenucleotide polymorphisms at candidate genes for droughtstress response in Pinus taeda L. Genetics 172: 1915–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivet D, Sebastiani F, Alía R, Bataillon T, Torre S, Zabal-Aguirre M et al. (2011). Molecular footprints of local adaptation in two Mediterranean conifers. Mol Biol Evol 28: 101–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillou H, Carracedo JC, Day S. (1998). Dating of the upper Pleistocene-Holocene volcanic activity of La Palma using the Unspiked K-Ar Technique. J Volcanol Geoth Res 86: 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Guillou H, Carracedo JC, Duncan R. (2001). K-Ar, 40Ar/39Ar Ages and magnetostratigraphy of Brunhes and Matuyama lava sequences from La Palma Island. J Volcanol Geoth Res 106: 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Guillou H, Pérez-Torrado FJ, Hansen A, Carracedo JC, Gimeno D. (2004). The Plio-Quatemary volcanic evolution of Gran Canaria based on new K-Ar ages and magnetostratigraphy. J Volcanol Geoth Res 135: 221–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock AM, Witonsky DB, Gordon AS, Eshel G, Pritchard JK, Coop G et al. (2008). Adaptations to climate in candidate genes for common metabolic disorders. PLoS Genet 4: e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock AM, Di Rienzo A. (2008). Detecting the signature of natural selection in human populations. Annu Rev Anthropol 37: 197–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock AM, Alkorta-Aranburu G, Witonsky DB, Di Rienzo A. (2010). Adaptations to new environments in humans: the role of subtle allele frequency shifts. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 365: 2459–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW. (2006). Genetic polymorphism in heterogeneous environments: The age of genomics. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S 37: 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. (2002). Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics 18: 337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys H. (1961) The Theory of Probability 3rd edn. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Juan C, Emerson BC, Oromí P, Hewitt GM. (2000). Colonization and diversification: towards a phylogeographic synthesis for the Canary Islands. Trends Ecol Evol 15: 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. (1968). Evolutionary rate at the molecular level. Nature 217: 6245–6626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer A, Ronce O, Robledo-Arnuncio JJ, Guillaume F, Bohrer G, Nathan R et al. (2012). Long-distance gene flow and adaptation of forest trees to rapid climate change. Ecol Lett 15: 378–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner C. (1996). Timberline and alpine vegetation on the tropical and warm-temperate oceanic islands of the world: elevation, structure and floristics. Vegetation 123: 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Levene H. (1953). Genetic equilibrium when more than one niche is available. Am Nat 87: 331–333. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin RC, Krakauer J. (1973). Distribution of gene frequency as a test of theory of selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74: 175–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (2011). A new test for detecting recent positive selection that is free from the confounding impacts of demography. Mol Biol Evol 28: 365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanes P, Herrera R, Gómez M, Muñoz A, Acosta J, Uchupi E et al. (2009). Geological evolution of the volcanic island La Gomera, Canary Islands, from analysis of its geomorphology. Mar Geol 264: 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- López R, Zehavi A, Climent J, Gil L. (2007). Contrasting ecotypic differentiation for growth and survival in Pinus canariensis. Aust J Bot 55: 759–769. [Google Scholar]

- López R, Rodríguez-Calcerrada J, Gil L. (2009). Physiological and morphological response to water deficit in seedlings of five provenances of Pinus canariensis: potential to detect variation in drought-tolerance. Trees-Struct Funct 23: 509–519. [Google Scholar]

- López R, López de Heredia U, Collada C, Cano FJ, Emerson BC, Cochard H et al. (2013). On vulnerability to cavitation, hydraulic efficiency, growth and survival on an insular pine (Pinus canariensis). Ann Bot London 111: 1167–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López de Heredia U, Venturas M, López R, Gil L. (2010). High biogeographical and evolutionary value of Canary Island pine populations out of the elevational pine belt: the case of a relict coastal population. J Biogeogr 37: 2371–2383. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Smith H, Haigh J. (1974). The hitchhiking effect of a favorable gene. Genet Res 23: 23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura M, Aitken SN. (2007). Adaptive gradients and isolation by distance with postglacial migration in Picea sitchensis. Heredity 99: 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca E, Eckert AJ, Di Pierro E, Rocchini D, La Porta N, Belletti P et al. (2012). The geographical and environmental determinants of genetic diversity for four alpine conifers of the European Alps. Mol Ecol 21: 5530–5545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navascués M, Vaxevanidou Z, González-Martínez SC, Climent J, Gil L. (2006). Chloroplast microsatellites reveal colonisation and metapopulation dynamics in the Canary Island pine. Mol Ecol 15: 2691–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navascués M, Emerson BC. (2007). Restoration of genetic diversity in reforested areas of the endemic Canary Island pine, Pinus canariensis. Forest Ecol Manag 244: 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. (1987) Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Palmé A, Wright M, Savolainen O. (2008). Patterns of divergence among conifer ESTs and polymorphism in Pinus sylvestris identify putative selective sweeps. Mol Biol Evol 25: 2567–2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamilo P. (1988). Genetic variation in heterogeneous environments. Ann Bot Fenn 25: 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JJ. (1981). Human influence in the pine and laurel forest of the Canary Islands. Geogr Rev 71: 253–271. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez de Paz P, del Arco M, Rodríguez O, Wildpret WY, Salas M. (1994) Atlas cartográfico de los pinares canarios: Gran Canaria, Lanzarote y Fuerteventura. Dir. Gral de Medio Ambiente y Cons. De la Naturaleza, Gobierno de Canarias, Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Torrado FJ. (1992) Volcanoestratigrafa del Grupo Roque Nublo (Gran Canaria). Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Torrado FJ, Carracedo JC, Mangas J. (1995). Geochronology and stratigraphy of the Roque Nublo Cycle, Gran Canaria, Canary Islands. J Geol Soc London 152: 807–818. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Martín JA, Nanos N, Miranda JC, Carbonell G, Gil L. (2013). Volcanic mercury in Pinus canariensis. Naturwissenschaften 100: 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahli HF, Conner JK, Shaw FH, Howe S, Lale A. (2008). Adaptive differentiation of quantitative traits in the globally distributed weed, wild radish (Raphanus raphanistrum). Genetics 180: 945–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen O, Pyhäjärvi T, Knürr T. (2007). Gene flow and local adaptation in trees. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S 38: 595–619. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller G, Korol L, Ungar ED, Zehavi A, Gil L, Climent J. (1999). Canary islands pine (Pinus canariensis Chr. Sm. ex DC.). 1. Differentiation among native populations in their isoenzymes. For Genet 6: 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Schluter D. (2000) The Ecology of Adaptive Radiation. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Spitze K. (1993). Population structure in Daphnia obtusa: quantitative genetic and allozymic variation. Genetics 135: 367–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M, Smith N J, Donnelly P. (2001). A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet 68: 978–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. (1989). Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123: 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui K, Suwa A, Sawada K, Kato T, Ohsawa TA, Watano Y. (2009). Incongruence among mitochondrial, chloroplast and nuclear gene trees in Pinus subgenus Strobus (Pinaceae). J Plant Res 122: 509–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogaard P, Schmincke HU. (1998) Chronostratigraphy of Gran Canaria In Weaver PPE, Schmincke H-U, Firth JV, Duffield W (eds.) Proc. ODP, Sci. Results, 157: College Station, (Ocean Drilling Program): TX, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Vaxevanidou Z, González-Martínez SC, Climent J, Gil L. (2006). Tree populations bordering on extinction: a case study in the endemic Canary Island pine. Biol Conserv 129: 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- VVAA. (2011) Plan de Adaptación de Canarias al Cambio Climático. Agencia Canaria de Desarrollo Sostenible y Cambio Climático, Gobierno de Canarias: Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Wachowiak W, Salmela MJ, Ennos RA, Iason G, Cavers S. (2011). High genetic diversity at the extreme range edge: nucleotide variation at nuclear loci in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) in Scotland. Heredity 106: 775–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson GA. (1975). On the number of segregating sites in genetical models without recombination. Theor Popul Biol 7: 256–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock MC. (2008). Evolutionary inference from QST. Mol Ecol 17: 1885–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. (1951). The genetical structure of populations. Ann Eugen 15: 323–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng K, Fu YX, Shi S, Wu CI. (2006). Statistical tests for detecting positive selection by utilizing high-frequency variants. Genetics 174: 1431–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.