Abstract

Objective To assess the effect of decreased sodium intake on blood pressure, related cardiovascular diseases, and potential adverse effects such as changes in blood lipids, catecholamine levels, and renal function.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, Embase, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, the Latin American and Caribbean health science literature database, and the reference lists of previous reviews.

Study selection Randomised controlled trials and prospective cohort studies in non-acutely ill adults and children assessing the relations between sodium intake and blood pressure, renal function, blood lipids, and catecholamine levels, and in non-acutely ill adults all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and coronary heart disease.

Study appraisal and synthesis Potential studies were screened independently and in duplicate and study characteristics and outcomes extracted. When possible we conducted a meta-analysis to estimate the effect of lower sodium intake using the inverse variance method and a random effects model. We present results as mean differences or risk ratios, with 95% confidence intervals.

Results We included 14 cohort studies and five randomised controlled trials reporting all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, or coronary heart disease; and 37 randomised controlled trials measuring blood pressure, renal function, blood lipids, and catecholamine levels in adults. Nine controlled trials and one cohort study in children reporting on blood pressure were also included. In adults a reduction in sodium intake significantly reduced resting systolic blood pressure by 3.39 mm Hg (95% confidence interval 2.46 to 4.31) and resting diastolic blood pressure by 1.54 mm Hg (0.98 to 2.11). When sodium intake was <2 g/day versus ≥2 g/day, systolic blood pressure was reduced by 3.47 mm Hg (0.76 to 6.18) and diastolic blood pressure by 1.81 mm Hg (0.54 to 3.08). Decreased sodium intake had no significant adverse effect on blood lipids, catecholamine levels, or renal function in adults (P>0.05). There were insufficient randomised controlled trials to assess the effects of reduced sodium intake on mortality and morbidity. The associations in cohort studies between sodium intake and all cause mortality, incident fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease were non-significant (P>0.05). Increased sodium intake was associated with an increased risk of stroke (risk ratio 1.24, 95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.43), stroke mortality (1.63, 1.27 to 2.10), and coronary heart disease mortality (1.32, 1.13 to 1.53). In children, a reduction in sodium intake significantly reduced systolic blood pressure by 0.84 mm Hg (0.25 to 1.43) and diastolic blood pressure by 0.87 mm Hg (0.14 to 1.60).

Conclusions High quality evidence in non-acutely ill adults shows that reduced sodium intake reduces blood pressure and has no adverse effect on blood lipids, catecholamine levels, or renal function, and moderate quality evidence in children shows that a reduction in sodium intake reduces blood pressure. Lower sodium intake is also associated with a reduced risk of stroke and fatal coronary heart disease in adults. The totality of evidence suggests that most people will likely benefit from reducing sodium intake.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases are the leading cause of death globally.1 In 2005, cardiovascular diseases accounted for 30% of all deaths, the equivalent of infectious disease, nutritional deficiency, and maternal and perinatal conditions combined.2 Raised blood pressure and hypertension are major risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and are estimated to contribute to 49% of all coronary heart disease and 62% of all stroke events.3 Hypertension currently affects nearly half of adults globally, with an even greater number experiencing raised blood pressure.4 Thus raised blood pressure, hypertension, and related non-communicable diseases are among the most important public health problems globally, and renewed efforts (including non-drug approaches) are urgently required to tackle this major public health burden. Increased sodium consumption is associated with increased blood pressure,5 whereas reduced sodium consumption decreases blood pressure.6,7,8,9 Sodium is an essential nutrient necessary for maintenance of plasma volume, acid-base balance, transmission of nerve impulses, and normal cell function,10,11 and the minimum daily required intake is estimated at 200-500 mg.10,12 Data from around the world suggest that average sodium consumption is well above that needed for physiological function and in many countries is greater than 2 g/day (equivalent to 5 g of salt daily), the value recommended by the 2002 joint World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations expert consultation9,13 and the 2007 WHO guideline.14 Many dietary components contain sodium, and cultural context and dietary habits determine the primary contributors to a population’s sodium intake.13,15 In addition to being a main chemical component in common table salt, sodium is found naturally in foods such as milk, meat, and shellfish. Many condiments such as soy and fish sauces, and processed foods such as breads, crackers, meats, and snack foods often contain high amounts of sodium. Thus a diet high in processed foods and low in fresh fruits and vegetables is often high in sodium, putting people at risk for raised blood pressure and related non-communicable diseases.

Several recent systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials concluded that reducing sodium intake decreases blood pressure in adults with or without hypertension.8,16,17,18,19 Increased sodium intake has also been associated with cardiovascular diseases.14,20 A recent meta-analysis of 13 cohort studies concluded that there was a direct relation between increased sodium consumption and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke.20 Recently published cohort studies not incorporated in that review were not consistent with those results21,22; however, they had methodological limitations.23,24,25 Additionally, a recent systematic review of randomised controlled trials detected no relation between sodium consumption and cardiovascular disease.26 However, the analysis was underpowered to detect a relation, as few long term randomised controlled trials have been conducted with these outcomes.24,25 In addition to these inconsistent results, some researchers have expressed concern that reduced sodium intake might also lead to adverse effects on health such as unhealthy changes in blood lipids, catecholamine levels, and renal function.18,27,28

To clarify the relation between sodium consumption and related non-communicable diseases, the WHO Nutrition Guidance Expert Advisory Group Subgroup on Diet and Health was requested to assess all available epidemiological and clinical evidence to review and, if necessary, revise and update the WHO guideline on sodium intake for adults and to establish a guideline for children. We therefore systematically compiled results from randomised controlled trials and cohort studies and conducted meta-analyses to quantify the effect of lower compared with higher sodium intake on blood pressure, all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, coronary heart disease, and potential adverse effects such as changes in blood lipids, catecholamine levels, and renal function in adults and on blood pressure, blood lipids, and catecholamine levels in children. We also assessed whether the absolute amount of sodium consumed or the relative reduction in sodium intake differentially affected these outcomes.

Methods

The protocol for this review was agreed by the WHO Nutrition Guidance Expert Advisory Group Subgroup on Diet and Health. This review used the methods recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration29 and was written in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement for reporting systematic reviews.30

Search strategy and selection criteria

Firstly, we searched the literature for recent systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials or cohort studies on the effect of lower sodium intake relative to higher sodium intake. If the inclusion criteria were in agreement with, or were broader than, the inclusion criteria defined for the specific objectives of the current literature review, we reviewed each of the original references and compared them against the inclusion criteria for the current review.

We then searched the literature on sodium intake and the outcomes of interest published since the data search of the identified systematic reviews. We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (24 August 2011), Medline (6 July 2011), Embase (2 August 2011), WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (23 August 2011), and the Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Literature Database (LILACS) (6 August 2011). See the supplementary file for the complete data search terms. No language or additional limits were applied. We examined the reference lists of included studies and contacted researchers in the specialty to identify any additional studies. Two reviewers independently screened the output of the search to identify potentially eligible studies.

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (both individual and cluster randomised). In the case of insufficient numbers of trials (<3), we included quasirandomised trials, non-randomised trials, and prospective, observational cohort studies.

We included randomised controlled trials that allocated at least one group of participants to decreased sodium intake and one group to higher sodium intake (the control group), had a duration of four or more weeks, achieved an intake difference of 40 or more mmol/day between intervention and control, and measured sodium intake with 24 hour urinary sodium excretion; and cohort studies with a prospective design that measured sodium intake in any way, had a duration of one or more years, and reported on an outcome of interest. The controlled trials could not have concomitant interventions (that is, non-drug interventions, antihypertensives, or other drugs) in the intervention group unless those interventions also applied to the control group, and thus the only difference between the groups was the level of sodium intake. We excluded studies targeting people who were acutely ill (including those with type 1 diabetes or acute heart failure), positive for HIV antibodies, or admitted to hospital.

Outcome data

Outcomes of interest in adults were blood pressure, all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, coronary heart disease, and potential adverse effects such as changes in blood lipids (total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride), catecholamine levels, renal function, and any side effect reported by the study authors. Outcomes in children were blood pressure, blood lipids, catecholamine levels, and any side effects reported by the study authors.

Data extraction, risk of bias, and quality assessment

Two reviewers used a standard data extraction form to independently extract relevant characteristics of the populations and interventions of each study. A third reviewer checked the data and disagreements were resolved through consensus. Any relevant missing information was requested from the study authors. In the case of duplicate publications and companion papers of a primary study, we maximised the yield of information by simultaneously evaluating all available data.

For randomised controlled trials, we assessed the risk of bias associated with the method of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, selective reporting, loss to follow-up, and completeness of reporting outcome data. In addition, in cohort studies we evaluated the risk of bias associated with the method of measuring exposure, collecting outcome data, and selecting participants. We rated the risk of bias as low, unclear, or high according to established criteria.31,32

We used funnel plots to assess whether there was small study bias.33,34 For each study type separately in adults and children we generated figures for a “risk of bias graph” and “risk of bias summary.” We assessed the quality to the entire body of evidence using the GRADE methodology35 and GRADEProfiler software (version 3.6, 2011). The WHO Nutrition Guidance Expert Advisory Group Subgroup on Diet and Health gave guidance to further refine and finalise the GRADE assessment.

Statistical analysis

One reviewer entered data into Review Manager software (Copenhagen, 2011) and a second reviewer checked data entry for accuracy. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted and a conclusion made based on consensus.

An overall effect estimate for all dichotomous data was calculated as a risk ratio with 95% confidence interval. Dichotomous data were extracted from each original study in the form of a risk ratio or hazard ratio calculated from the statistical model that controlled for the most number of covariates (to reduce bias), without controlling for blood pressure because blood pressure explains some of the effect sodium has on non-communicable disease related outcomes. In the analyses of data from cohort studies, the overall effect estimate was generated comparing the risk of each outcome in the lowest sodium intake (reference) group with the highest sodium intake group. When appropriate, we used the comparison of different intake groups with the reference group from the same study in different subgroup analyses, but the subgroups were not pooled.

We expressed the overall effect estimate for all continuous variables as the difference in means with 95% confidence interval between the lower sodium (intervention) group and the higher sodium (control) group. When there was more than one intervention group but only one control group, we used the group with the lowest sodium intake in the analysis. When appropriate we compared each intervention group with the control in different subgroup analyses and did not pool the subgroups. When there were multiple intervention groups with multiple control groups reported in the same study, we included all comparisons of an intervention group with the appropriate control in the pooled analysis.

Sodium intake was estimated to equal 24 hour urinary sodium excretion.36 When outcomes were assessed at more than one time point, we used data from the latest time point available except for subgrouping by study duration, in which we used all relevant time points. To combine data and generate the overall effect estimate we used the inverse variance method, random effects meta-analysis in Review Manager software.32 We considered results to be statistically significant at an α=0.05.

We considered evidence as conclusive of either benefit or harm from decreased sodium intake if the point estimate suggested a benefit or harm and the 95% confidence interval did not overlap a threshold of relevance. If the point estimate was near the null value and the confidence intervals did not overlap a threshold of relevance we considered evidence conclusive of no effect. In such cases, we considered the point estimates to be precise. Conversely, we considered evidence to be inconclusive if the point estimate suggested a benefit or harm but the confidence intervals crossed a threshold of relevance. In such cases, the point estimates were imprecise.

We assessed heterogeneity through visual inspection of the forest plots and with the I2 statistic quantifying inconsistency across studies.37,38 An I2 statistic of 75% or greater was considered an important level of inconsistency. When important heterogeneity was found we combined the data in meta-analyses taking note of the heterogeneity and we attempted to explain the heterogeneity by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

We considered several subgroups for testing specific objectives and exploring potential reasons for heterogeneity: relative achieved sodium intake in intervention group (reduction in intake of less than one third relative to control versus one third or more relative to control); absolute achieved sodium intake in intervention group (<2 g/day v ≥2 g/day; <1.2 g/day v ≥1.2 g/day); hypertensive status of participants at baseline (with hypertension versus without hypertension versus mixed or unspecified); sex (male v female v mixed); type of device used to measure blood pressure (automatic v manual); method of measurement of blood pressure (supine office v seated office v standing office v combination office v combination home v unspecified); study design (parallel v crossover); and duration of intervention (<3 months v 3-6 months v >6 months).

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of removing studies at high risk of bias from the analysis. A randomised controlled trial was considered to be at high risk of bias if it was graded as inadequate in both the randomisation and the allocation concealment and in either blinding or loss to follow-up. We considered a cohort study to be at high risk of bias if the measurement method for estimating sodium intake was a single 24 hour dietary recall or if the study was at high risk for confounding for both measurement method and another reason.

Results

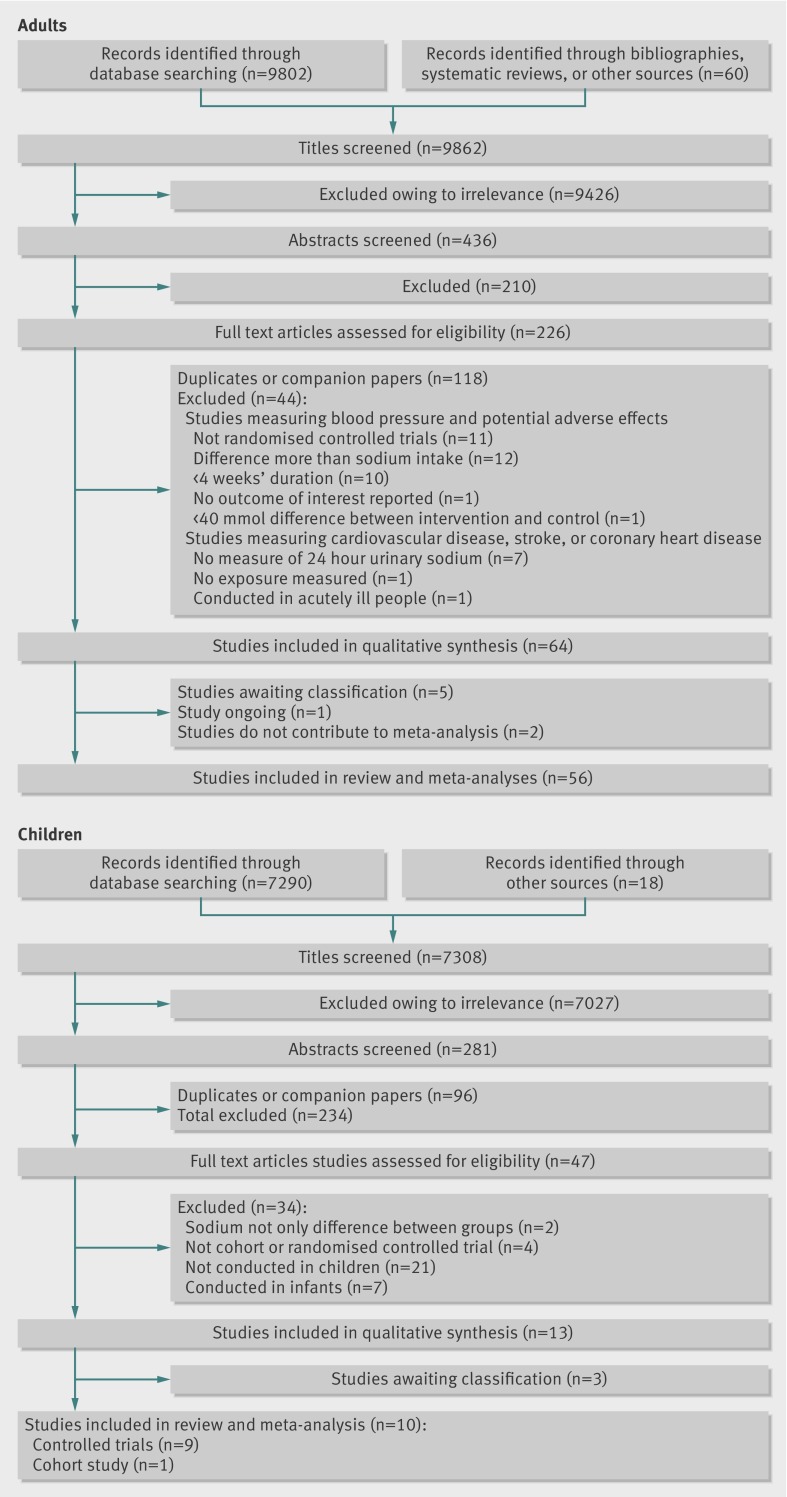

Overall, 9862 publications reporting on sodium and at least one outcome of interest in adults were identified (fig 1 ). Of these, 60 were found in the reference lists of recent systematic reviews8,20 or through other sources and 9802 in the electronic search. After elimination of irrelevant studies and abstracts not reaching inclusion criteria, 226 full text publications were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 118 were duplicates or companion papers of primary studies and 44 were excluded on full text review. Five studies had key methodological information not available from published manuscripts and additional information was requested but not received,39,40,41,42,43 one study is ongoing,44 and two studies did not contain the complete quantitative data needed for meta-analysis.45,46 Thus 64 studies contributed to the systematic review and 56 contributed to the meta-analyses: 37 randomised controlled trials reporting blood pressure, blood lipids, catecholamine levels, or renal function47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93; 14 cohort studies reporting all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, or coronary heart disease21,22,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107; and five randomised controlled trials reporting all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, or coronary heart disease.86,91,108,109,110

Fig 1 Flow of records in adults and children

In total, 7308 potential publications reported on blood pressure, blood lipids, or catecholamine levels in children. Eighteen were from reference lists of previous reviews111,112 or other sources, and 7290 were from the electronic search. After excluding studies that were irrelevant or did not meet basic inclusion criteria based on the review of titles and abstracts, 57 full text publications were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 24 were duplicates and 29 were excluded. Key methodological information was not available from the published manuscripts of three studies and requested information was not provided.39,40,43 No randomised controlled trials but one cohort study113 could contribute to the review. Because of the sparseness of data in children, the 281 potentially eligible abstracts in children were re-evaluated with broader inclusion criteria, including duration of more than three weeks, any controlled design, any difference in sodium intake between intervention and control, and any method of measuring intake. Ninety six duplicates were removed and 138 abstracts excluded (fig 1). Forty seven full text articles were assessed for eligibility. One study was the previously identified cohort study that reached inclusion criteria,113 and three were those previously identified but lacking key information.39,40,43 Thirty four studies were excluded and nine controlled trials included in the review.114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122 These studies did not reach the original inclusion criteria because three were non-randomised controlled trials,114,115,116 two were of three week’s duration,117,118 three did not measure 24 hour urinary sodium excretion,119,120,121 and one did not achieve a 40 mmol difference in sodium intake between intervention and control.122 Ten studies in children were included in the review: six randomised controlled trials, three non-randomised controlled trials, and one cohort study.

Study characteristics

Randomised controlled trials in adults were conducted in Australia, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These studies measured blood pressure, renal function, blood lipids, and catecholamine levels between lower and higher sodium intake (control) groups. The one ongoing study is being undertaken in Italy.44 Length of intervention ranged from four weeks to 36 months; however, most studies (n=31) were less than three months. In total the studies included 5508 participants, with individual study sizes ranging from 16 to 2382. There were 1478 participants with hypertension, 3263 without hypertension, and 767 with undisclosed hypertensive status at baseline. The intervention in 12 randomised controlled trials was dietary advice or education and one trial supplied participants with food of a known sodium level. Most studies (n=24) had a run-in period where all participants achieved a reduced sodium intake through some combination of dietary advice, education, counselling, or provision of key foods with reduced sodium content (for example, butter, bread), and participants received either sodium or placebo tablets. See the supplementary file for details of the study characteristics.

Five randomised controlled trials and 15 cohort studies in adults reported cardiovascular disease, stroke, or coronary heart disease incidence, morbidity or mortality, or all cause mortality. The characteristics of the randomised controlled trials have been described previously.26 The cohort studies were undertaken in Australia, Belgium, Finland, Japan, the Netherlands, Scotland, Taiwan, and the United States; and one study included participants from 40 countries. Nine studies utilised representative data from a large geographical region and relied on health statistics for measuring outcomes. One study was a worksite based study. One study followed participants who had previously participated in a randomised controlled trial of a dietary intervention to reduce sodium intake. Two studies measured baseline variables and followed up directly with participants over the course of the study. The duration of follow-up varied from 3.8 to 22 years. One study did not report variance estimates and was therefore not included in the meta-analysis.105 All studies divided the sample population according to sodium intake at baseline and calculated the risk of outcome by sodium intake group.

In children, the nine controlled trials were conducted in Australia and the United States and the cohort study was undertaken in the Netherlands. The controlled trials included a total of 1299 male and female children and adolescents aged 2.6 to 19.8 years. The cohort study measured a total of 596 children aged 5-17 years at baseline and followed them for seven years. Two hundred and thirty three children completed the study and were included in the analysis.

Effect estimates

Blood pressure, renal function, blood lipids, and catecholamine levels in adults

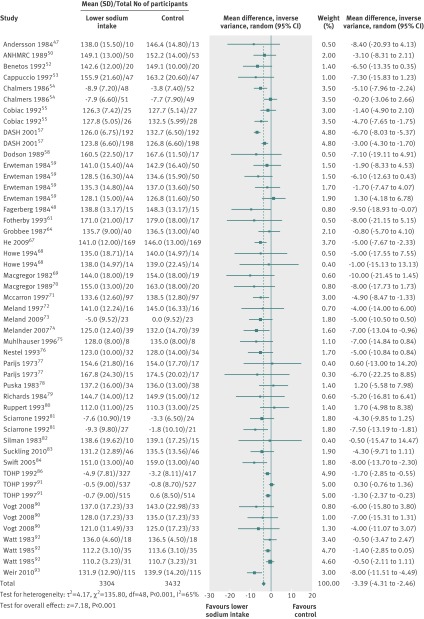

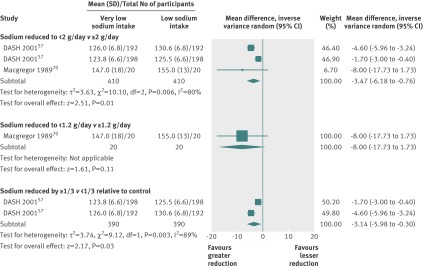

The meta-analysis of 36 studies contributing 49 comparisons found that a reduction in sodium intake significantly reduced resting systolic blood pressure by 3.39 mm Hg (95% confidence interval 2.46 to 4.31 mm Hg) (fig 2 ) and resting diastolic blood pressure by 1.54 mm Hg (0.98 to 2.11). Two studies had multiple intervention arms in which participants were randomly assigned to lower sodium or very low sodium or control allowing for direct comparisons of various levels of sodium intake relative to control (fig 3 ). The meta-analysis of three comparisons showed a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure by 3.47 mm Hg (0.76 to 6.18 mm Hg) and diastolic blood pressure by 1.81 mm Hg (0.54 to 3.08 mm Hg) when sodium intake was <2 g/day compared with ≥2 g/day. There was only one comparison of <1.2 g/day versus ≥1.2 g/day and it reported a non-significant decrease in systolic blood pressure of 8.00 mm Hg (−1.73 to 17.73 mm Hg) and diastolic blood pressure of 4.00 mm Hg (−1.58 to 9.58 mm Hg). The meta-analysis of two comparisons detected a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure by 3.14 mm Hg (0.30 to 5.98 mm Hg) and diastolic blood pressure by 1.70 mm Hg (0.33 to 3.07 mm Hg) when the relative reduction in sodium intake was one third or more of control compared with less than one third of control.

Fig 2 Effect of reduced sodium intake on resting systolic blood pressure in adults

Fig 3 Direct comparisons of effect of sodium consumption of <2 g/day v >2g/day, <1.2 g/day v >1.2 g/day, and a reduction by one third or more versus less than one third relative to control on systolic blood pressure in adults

The test for heterogeneity in the previous analyses suggested some level of heterogeneity among the studies. Subgrouping reduced heterogeneity in most cases and the results showed that reduced sodium intake reduced blood pressure regardless of subgroup (table 1). The reduction in systolic blood pressure was greater in studies of participants with hypertension (4.06 mm Hg, 2.96 to 5.15 mm Hg) than in studies of those without hypertension (1.38 mm Hg, 0.02 to 2.74 mm Hg). The reduction in systolic or diastolic blood pressure in subgroups based on absolute sodium intake in the intervention group (<2 g/day v ≥2 g/day, <1.2g/day v ≥1.2 g/day) did not differ significantly. The subgroup of studies in which the relative reduction in sodium intake was one third or more of control had a significantly greater decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared with a relative reduction of less than one third of control. Reduced sodium intake significantly decreased systolic blood pressure in studies of less than three months or 3-6 months, and non-significantly decreased systolic blood pressure in the three studies of more than six months. Reduced sodium intake lowered systolic blood pressure regardless of sex, measurement device or method, status of drug to control blood pressure, or study design. Reductions in diastolic blood pressure were less pronounced, but patterns based on subgroups were similar to those for systolic blood pressure.

Table 1.

Estimates of effect of reduced sodium on systolic and diastolic blood pressure in adults overall and by subgroup

| Subgroup | No of studies | No of participants* | Systolic blood pressure | Diastolic blood pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | Effect estimate: mean difference (95% CI)†‡ | I2 | Effect estimate: mean difference (95% CI) | ||||

| Overall | 36 | 6736 | 65 | −3.39 (−4.31 to −2.46) | 60 | −1.54 (−2.11 to −0.98) | |

| Blood pressure status at baseline: | |||||||

| No hypertension | 7 | 3067 | 61 | −1.38 (−2.74 to −0.02) | 38 | −0.58 (−1.29 to 0.14) | |

| Hypertension | 24 | 2273 | 13 | −4.06 (−5.15 to −2.96) | 29 | −2.26 (−3.02 to −1.50) | |

| Absolute sodium intake in intervention group (g/day): | |||||||

| <2 | 16 | 2415 | 68 | −3.39 (−4.69 to −2.09) | 71 | −1.54 (−2.46 to −0.63) | |

| ≥2 | 22 | 5141 (5147) | 48 | −2.68 (−3.66 to −1.70) | 31 | −1.21 (−1.72 to −0.70) | |

| <1.2 | 3 | 209 | 0 | −6.39 (−9.53 to −3.25) | 65 | −2.47 (−5.86 to 0.92) | |

| ≥1.2 | 34 | 6567 (6480) | 65 | −3.23 (−4.17 to −2.28) | 62 | −1.58 (−2.17 to −0.99) | |

| Relative sodium reduction in intervention group: | |||||||

| <1/3 of control | 8 | 3995 (4001) | 46 | −1.45 (−2.29 to −0.60) | 38 | −0.74 (−1.28 to −0.19) | |

| ≥1/3 of control | 30 | 3521 | 55 | −3.79 (−4.82 to −2.75) | 55 | −1.68 (−2.34 to −1.02) | |

| Trial duration (months): | |||||||

| <3 | 31 | 3351 | 51 | −4.07 (−5.12 to −3.02) | 49 | −1.67 (−2.33 to −1.02) | |

| 3-6 | 5 | 2817 | 67 | −1.91 (−3.60 to −0.23) | 67 | −1.33 (−2.50 to −0.15) | |

| >6 | 3 | 2862 | 59 | −0.88 (−2.00 to 0.23) | 56 | −0.45 (−1.25 to 0.34) | |

| Sex: | |||||||

| Male§ | 2 | 53 | 0 | −9.10 (−16.63 to −1.57) | 0 | −4.83 (−8.98 to −0.68) | |

| Mixed | 34 | 6749 | 65 | −3.34 (−4.25 to −2.42) | 60 | −1.50 (−2.07 to −0.94) | |

| Device used to measure blood pressure: | |||||||

| Automatic | 17 | 1678 | 3 | −4.04 (−5.10 to −2.97) | 33 | −1.75 (−2.54 to −0.95) | |

| Manual | 19 | 5048 | 76 | −2.93 (−4.15 to −1.71) | 70 | −1.40 (−2.18 to −0.62) | |

| Method used to measure blood pressure: | |||||||

| Supine office | 15 | 1127 | 0 | −4.69 (−6.33 to −3.06) | 0 | −2.03 (−3.03 to −1.03) | |

| Seated office | 18 | 5542 | 76 | −2.91 (−3.99 to −1.82) | 74 | −1.38 (−2.07 to −0.68) | |

| Standing office | 8 | 705 | 0 | −4.44 (−6.92 to −1.96) | 0 | −1.86 (−3.34 to −0.38) | |

| Combination office¶ | 1 | 16 | NA | −7.00 (−14.84 to 0.84) | NA | −1.00 (−6.00 to 4.00) | |

| Combination home** | 1 | 16 | NA | −9.00 (−18.32 to 0.32) | NA | −1.00 (−5.44 to 3.44) | |

| Drug consumption to control blood pressure: | |||||||

| Not taking drugs | 27 | 5456 | 71 | −3.66 (−4.85 to −2.47) | 62 | −1.70 (−2.37 to −1.04) | |

| Taking drugs | 6 | 927 | 9 | −4.55 (−6.59 to −2.51) | 6 | −2.05 (−3.19 to −0.91) | |

| Mixed or not specified | 6 | 419 | 27 | −1.67 (−3.01 to −0.34) | 58 | −0.45 (−1.93 to 1.03) | |

| Study design: | |||||||

| Parallel | 16 | 4147 | 44 | −2.47 (−3.51 to −1.43) | 52 | −1.33 (−2.04 to −0.62) | |

| Crossover | 22 | 2849 | 63 | −4.04 (−5.27 to −2.81) | 54 | −1.70 (−2.43 to −0.97) | |

*Values in brackets relate to diastolic blood pressure.

†Inverse variance, random effects model.

‡Negative mean differences represent greater decreases in intervention versus control.

§No studies reported results for women only.

¶Average of measurement from multiple types of methods such as sitted, supine, or standing all taken in a clinic or office setting.

**Average of measurement from multiple types of methods such as sitted, supine, or standing all taken in the home.

In the meta-analyses of 11 studies (2339 participants) reporting changes in blood lipids, reduced sodium intake had no significant adverse effect on total cholesterol (mean difference 0.02 mmol/L, 95% confidence interval −0.03 to 0.07 mmol/L), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (0.03 mmol/L, −0.02 to 0.08 mmol/L), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (−0.01 mmol/L, −0.03 to 0.00 mmol/L), or triglyceride levels (0.04 mmol/L, −0.04 to 0.09 mmol/L, table 2).

Table 2.

Estimates of effect of reduced sodium on potential adverse effects in adults

| Outcome | No of studies | No of participants | I2 | Effect estimate: mean difference (95% CI)* † |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 11 | 2339 | 0 | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.07) |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 6 | 1909 | 0 | 0.03 (−0.02 to 0.08) |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol cholesterol (mmol/L) | 9 | 2031 | 0 | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.00) |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 8 | 2049 | 0 | 0.04 (−0.04 to 0.09) |

| Urinary adrenaline (epinephrine, pg/mL) | 1 | 18 | NA | −13.10 (−29.24 to 3.04) |

| Urinary noradrenaline (norepinephrine, pg/mL) | 2 | 53 | 0 | 17.13 (−34.06 to 68.33) |

| Plasma adrenaline (pg/mL) | 4 | 168 | 0 | 6.90 (−2.17 to 15.96) |

| Plasma noradrenaline (pg/mL) | 7 | 265 | 32 | 8.23 (−27.84 to 44.29) |

| Urinary protein excretion (µmol/L) | 1 | 198 | NA | −76.61 (−154.20 to 0.97) |

| Protein:creatinine ratio (mg protein:mmol creatinine) | 1 | 198 | NA | −0.40 (−0.73 to −0.07) |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 2 | 232 | 0 | −7.67 (−16.17 to 0.83) |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 5 | 728 | 0 | 1.68 (−0.65 to 4.00) |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 1 | 78 | NA | −5.00 (−15.25 to 5.25) |

NA=not applicable.

*Inverse variance, random effects model.

†Negative mean differences represent greater decreases in intervention versus control.

The one randomised controlled trial reporting urinary adrenaline (epinephrine) and two randomised controlled trials reporting urinary noradrenaline (norepinephrine) detected no effect of reduced sodium intake on these indicators (mean differences, adrenaline −13.10 pg/mL, −29.24 to 3.04 pg/mL; noradrenaline 17.13 pg/mL, −34.06 to 68.33 pg/mL). The four randomised controlled trials reporting plasma adrenaline and seven randomised controlled trials reporting plasma noradrenaline also detected no effect of reduced sodium on catecholamine levels (adrenaline 6.90 pg/mL, −2.17 to 15.96 pg/mL; noradrenaline 8.23 pg/mL, −27.84 to 44.29 pg/mL).

Several studies reported renal function with various indicators. The meta-analysis of three comparisons, all from the same randomised controlled trial, detected a non-significantly lower urinary protein excretion with reduced sodium intake (−76.61 µmol/L, −0.97 to −154.2 µmol/L). One other randomised controlled trial, which could not be combined in the meta-analysis because of the way the results were presented, also reported lower urinary protein excretion with lower sodium intake.39 Three randomised controlled trials reported urinary albumin excretion but could not be combined in a meta-analysis owing to the highly skewed distribution of this variable. The results were consistent with a beneficial effect of lower sodium intake on renal function.61,65,83

All cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and coronary heart disease in adults

Two recent systematic reviews reported all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, or coronary heart disease20,26: one included randomised controlled trials and the other cohort studies. Two of the studies included in the systematic review of randomised controlled trials were excluded from the current review: one was conducted in acutely ill patients123 and one manipulated both sodium and potassium intake in the intervention group.124 The number of stroke events (n=4) and coronary heart disease events (n=7) were insufficient in the remaining studies to generate meaningful effect estimates. The meta-analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials with two comparisons reporting cardiovascular events was inconclusive (risk ratio 0.84, 95% confidence interval 0.57 to 1.23). (In the analyses of data from randomised controlled trials, a risk ratio less than 1 signifies a decreased risk with decreased sodium intake, whereas a risk ratio greater than 1 signifies an increased risk with decreased sodium intake.)

One study that had been included in the recent systematic review of cohort studies was excluded owing to lack of quantification of sodium use.125 Two additional recently completed studies were also included21,22 in the current review, totalling 15 studies. One study did not report a variance estimate and thus could not contribute to the meta-analyses.45 The meta-analysis of seven studies with 10 comparisons reporting all cause mortality was inconclusive (risk ratio 1.06, 0.94 to 1.20) (table 3). (In the analyses of data from cohort studies, a risk ratio greater than 1 signifies an increased risk with increased sodium intake.)

Table 3.

Estimates of effect associated with sodium intake on risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and coronary heart disease calculated from cohort studies in adults overall and by subgroup of outcome type

| Outcome or subgroup | No of studies | No of participants | I2 | Effect estimate: risk ratio (95% CI)*† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cause mortality21 22 96 97 100 101 106 | 7 | 21 515 | 61 | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.20) |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

| All events‡21 22 94 96 100 101 106 107 | 9 | 46 483 | 78 | 1.12 (0.93 to 1.34) |

| Combined fatal and non-fatal events§21 22 94 97 | 4 | 8698 | 77 | 1.08 (0.78 to 1.47) |

| Fatal events21 22 96 100 101 106 107 | 7 | 41 881 | 80 | 1.08 (0.87 to 1.33) |

| Non-fatal events | 0 | 0 | NA | — |

| Stroke: | ||||

| All events21 22 100-104 106 107 | 10 | 72 878 | 49 | 1.24 (1.08 to 1.43) |

| Combined fatal and non-fatal events21 22 100-103 106 | 8 | 28 974 | 20 | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.26) |

| Fatal events101 104 107 | 3 | 48 645 | 33 | 1.63 (1.27 to 2.10) |

| Non-fatal events | 0 | 0 | NA | — |

| Coronary heart disease: | ||||

| All events22 94 100 101 106 107 | 6 | 37 343 | 68 | 1.04 (0.86 to 1.24) |

| Combined fatal and non-fatal events22 94 100 101 106 | 5 | 13 851 | 72 | 1.02 (0.83 to 1.24) |

| Fatal events101 106 107 | 3 | 30 670 | 0 | 1.32 (1.13 to 1.53) |

| Non-fatal events | 0 | 0 | NA | — |

*Inverse variance, random effects model.

†Risk ratios >1 calculated from cohort studies signify increased risk with increased sodium intake.

‡Pooled analysis included combined fatal and non-fatal or fatal or non-fatal event outcome reported in original studies. If multiple outcomes were reported in the same study, only one was used in calculation of pooled estimate with priority given to outcomes in the order: combined fatal and non-fatal events, fatal events, non-fatal events.

§A composite indicator reported by original study authors that combined all events occurring in study.

The meta-analysis of 10 studies with 14 comparisons reporting incidence of stroke detected an increased risk of stroke with higher sodium intake (1.24, 1.08 to 1.43). When only fatal events were considered, the risk ratio was 1.63 (1.27 to 2.10). The meta-analyses of sodium intake and cardiovascular disease or coronary heart disease were inconclusive (1.12, 0.93 to 1.34 and 1.04, 0.86 to 1.24, respectively). The meta-analysis of three studies with five comparisons of sodium intake and coronary heart disease mortality detected an increased risk of fatal coronary heart disease events with higher sodium intake (1.32, 1.13 to 1.53).

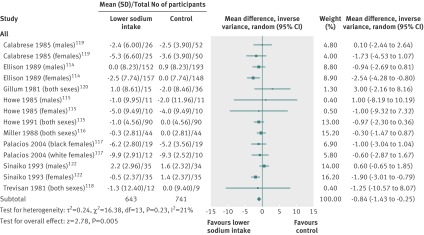

Blood pressure, blood lipids, and catecholamine levels in children

The meta-analysis of nine controlled trials with 14 comparisons in children found that reducing sodium intake decreased resting systolic blood pressure by 0.84 mm Hg (0.25 to 1.43 mm Hg) (fig 4 ). The meta-analysis of eight controlled trials with 12 comparisons found that reducing sodium intake decreased resting diastolic blood pressure by 0.87 mm Hg (0.14 to 1.60 mm Hg). The cohort study reported a non-significant higher rate of increase in blood pressure over time in the group of children consuming the highest amount of sodium compared with the group consuming the lowest. None of the studies that reached the inclusion criteria for this review reported the effect of lower sodium intake on blood lipids, catecholamine levels, or side effects in children.

Fig 4 Effect of reduced sodium intake on resting systolic blood pressure in children

Quality of body of evidence

Funnel plots indicated little risk of publication bias from randomised controlled trials or cohort studies in adults or from controlled trials in children (see supplementary file). The risk of bias summaries and risk of bias graphs (see supplementary file) suggest that the entire body of evidence from randomised controlled trials in adults was not at risk of serious problems as a result of bias; and although some bias is present in many cohort studies, the entire body of evidence is possibly not at risk of serious problems beyond the inherent risk of bias in observational studies. The body of evidence for children, however, was possibly at risk of problems as a result of bias: four studies did not have random sequence generation,114,115,119,120 five had inadequate allocation concealment,114,115,118,119,120 and three had unclear allocation concealment.117,121,122 Blinding of participants and staff was not present in four studies,114,115,118,120 and blinding of outcome assessors was reported in only one study.119 There was little indication of bias due to selective reporting or attrition. Three studies were considered to be at high risk of bias.114,115,120

According to the GRADE criteria,35 the evidence for a decreased sodium intake reducing blood pressure in adults was of high quality (table 4). The evidence for no effect of reduced sodium intake on blood lipids, catecholamine levels, and renal function was also high quality. The quality of the direct evidence for a positive association between sodium intake and risk of stroke from cohort studies was very low when all outcomes were combined, and of low quality when incident events and fatal incident events were analysed separately. The quality of evidence of a direct relation between sodium intake and fatal coronary heart disease events was also low. The low and very low quality of this evidence reflects that the GRADE methodology defines observational evidence from cohort studies as low quality. Recognising the limitations of any biomarker, the current review considered data from change in systolic blood pressure as indirect evidence for the effect of sodium intake on risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Blood pressure is recognised as a reliable biomarker for estimating risk of cardiovascular disease126,127 because of the well established causal relation between increasing blood pressure and increasing risk of cardiovascular diseases, especially coronary heart disease and stroke.3,128

Table 4.

GRADE summary of findings table showing quality of evidence of an effect of reduced sodium intake on selected health outcomes in adults

| Outcomes | Effect (95% CI) | No of participants (No of studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease* (directly assessed; RR >1 indicates increased risk with higher sodium intake) | RR 1.12 (0.93 to 1.34) | 46 483 (9) | Very low | Data from cohort studies begin with a GRADE of low; downgraded owing to imprecision because 95% confidence interval crossed threshold of relevance of benefit or harm |

| Cardiovascular disease* (directly assessed; RR <1 indicates decreased risk with decreased sodium intake) | RR 0.84 (0.57 to 1.23) | 720 (2) | Moderate | Data from randomised controlled trials, only two studies; downgraded owing to imprecision because 95% confidence interval crossed threshold of relevance of benefit or harm |

| Stroke all (directly assessed: RR >1 indicates increased risk with higher sodium intake) | RR 1.24 (1.08 to 1.43) | 72 878 (10) | Very low | Data from cohort studies begin with GRADE of low; downgraded owing to inconsistency |

| Stroke combined fatal and nonfatal (directly assessed: RR >1 indicates increased risk with higher sodium intake) | RR 1.13 (1.01 to 1.26) | 28 974 (8) | Low | Data from cohort studies begin with GRADE of low; data not downgraded |

| Stroke fatal (directly assessed: RR >1 indicates increased risk with higher sodium intake) | RR 1.63 (1.27 to 2.10) | 48 645 (3) | Low | Data from cohort studies begin with GRADE of low; data not downgraded |

| Coronary heart disease all (directly assessed: RR >1 indicates increased risk with higher sodium intake) | RR 1.04 (0.86 to 1.24) | 37 343 (6) | Very low | Data from cohort studies begin with GRADE of low; downgraded owing to imprecision because 95% confidence interval crossed threshold of relevance of benefit or harm |

| Coronary heart disease combined fatal and nonfatal (directly assessed: RR >1 indicates increased risk with higher sodium intake) | RR 1.02 (0.83 to 1.24) | 13 851 (5) | Very low | Data from cohort studies begin with GRADE of low; downgraded owing to imprecision because 95% confidence interval crossed threshold of relevance of benefit or harm |

| Coronary heart disease fatal (directly assessed: RR >1 indicates increased risk with higher sodium intake) | RR 1.32 (1.13 to 1.53) | 30 670 (3) | Low | Data from cohort studies begin with GRADE of low; data not downgraded |

| All cause mortality (directly assessed: RR >1 indicates increased risk with higher sodium intake) | RR 1.06 (0.94 to 1.20) | 21 515 (7) | Very low | Data from cohort studies begin with GRADE of low; downgraded owing to inconsistency |

| Resting systolic blood pressure† (follow-up 1-36 months; units mm Hg; better indicated by lower values) | MD 3.39 lower‡ (4.31 to 2.46 lower) | 6736 (36) | High | Evidence suggests a dose response with greater benefit to blood pressure as sodium intake decreases |

| Total cholesterol§ (follow-up 1-2 months; units mmol/L; better indicated by lower values) | MD 0.02 higher (0.03 lower to 0.07 higher) | 2339 (11) | High | Not downgraded owing to imprecision because 95% confidence interval did not cross threshold of relevance of benefit or harm |

| Plasma noradrenaline¶ (follow-up 1-2.5 months; units pg/mL; better indicated by lower values) | MD 8.23 higher (27.84 lower to 44.29 higher) | 265 (7) | High | Not downgraded owing to imprecision because 95% confidence interval did not cross threshold of relevance of benefit or harm |

| Urinary protein excretion** (follow-up mean 1.5 months; units ng/mL filtrate; better indicated by lower values) | MD 76.6 lower (154.2 lower to 0.97 higher) | 189 (1) | High | Only one study with three comparisons included in meta-analysis to produce effect estimate |

| Minor side effects†† (better indicated by lower values) | — | 249 (3) | — | No quantitative data available |

RR=risk ratio; MD=mean difference.

*Composite cardiovascular disease as reported by original study authors. Variable included some or all of fatal and non-fatal stroke, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, congestive cardiac failure, episode of coronary revascularisation, bypass grafting, or angioplasty.

†Additional evidence from a meta-analysis of 36 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with 49 comparisons reporting resting diastolic blood pressure is supportive of a benefit of decreased sodium on blood pressure (mean difference 1.54 mm Hg lower, 2.11 to 0.98 lower) (quality of evidence high), and a meta-analysis of six RCTs with six comparisons reporting ambulatory systolic and diastolic blood pressure is supportive of a benefit of decreased sodium on blood pressure (systolic mean difference 5.51 mm Hg lower (7.87 to 3.16 lower); diastolic 2.94 mm Hg lower (4.36 to 1.51 lower)) (quality of evidence high).

‡A mean difference described as lower signifies a reduction in outcome in decreased sodium versus higher sodium group.

§Consistent with no effect of reduced sodium intake on total cholesterol levels, four additional RCTs qualitatively reported no statistically significant difference between reduced sodium and control groups in total cholesterol levels. A meta-analysis of 9 RCTs with 11 comparisons reporting high density lipoprotein (HDL) levels was consistent with a slight decrease in HDL which did not indicate a decrease of biological importance (mean difference 0.01 mmol/L lower, 0.03 lower to 0.00) (quality of evidence moderate). A meta-analysis of six RCTs with eight comparisons reporting low density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration was consistent with no effect of low sodium intake on LDL (mean difference 0.03 mmol/L higher, 0.02 lower to 0.08 higher) (quality of evidence high). A meta-analysis of eight RCTs with 10 comparisons reporting total triglyceride levels was consistent with no effect of low sodium on triglyceride concentration (mean difference 0.04 mmol/L lower, 0.01 lower to 0.09 higher) (quality of evidence high).

¶Meta-analysis of four RCTS with four comparisons reporting plasma adrenaline is supportive of no effect of reduced sodium on catecholamine levels (mean difference 6.90 pg/mL higher, 2.17 lower to 15.96 higher) (quality of evidence high).

**Consistent with a beneficial effect of reduced sodium on renal function, one study, which could not be combined in the meta-analysis due to the form of results, reported a reduction in urinary protein excretion with reduced sodium. Consistent with a beneficial effect of reduced sodium, one study with 169 participants in the low sodium group and 169 in the control group reported a significant reduction in urinary albumin levels with low sodium intake, one study with 46 participants in the low sodium group and 46 in the control group reported a non-significant decrease in urinary albumin with reduced sodium, and one study with 17 participants in the low sodium group and 17 in the control group reported no change. Consistent with a beneficial effect of reduced sodium, two studies reported reduced urinary albumin:creatinine ratio with low sodium intake.

††Minor adverse effects such as headache, oedema, dizziness, and muscle aches were reported in three studies and there was no difference in reported minor adverse effects between low sodium and control groups.

According to the GRADE criteria,35 the evidence in children that a lower sodium intake reduced blood pressure was moderate for systolic blood pressure and low for diastolic blood pressure (table 5). We considered the body of evidence to be at high risk of bias because two studies with four comparisons were not randomised. Only one study119 had clear blinding of participants, staff, and outcome assessors, and two studies clearly did not blind participants, staff, and outcome assessors.114,115 Blinding was unclear in the other studies. The evidence of the effect estimate for reduced sodium intake on diastolic blood pressure was downgraded a second time owing to inconsistency because the 95% confidence intervals of the studies did not always overlap with one another and were on both sides of zero. The data from the systematic review in adults were used as part of the evidence base for estimating the effect of reduced sodium intake on health outcomes in children. This evidence was downgraded from high to moderate because of indirectness—that is, use of a proxy population for the target population.

Table 5.

GRADE summary of findings table showing quality of evidence of an effect of lower sodium intake on selected health outcomes in children

| Outcomes | Effect (95% CI) | No of participants (No of studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting systolic blood pressure* (assessed in children, follow-up 1-36 months; units mm Hg; better indicated by lower values) | MD 0.84 lower† (1.43 to 0.25 lower) | 1384 (9) | Moderate | 2 studies with 4 comparisons were not randomised; downgraded owing to high risk of bias |

| Resting systolic blood pressure (assessed in adults, follow-up 1-36 months; units mm Hg; better indicated by lower values) | MD 3.39 lower (4.31 to 2.46 lower) | 6736 (36) | Moderate | Downgraded owing to indirectness |

| Total cholesterol (assessed in children) | — | — | — | No studies assessed this outcome in children |

| Total cholesterol‡ (assessed in adults; follow-up 1-2 months; units mmol/L; better indicated by lower values) | MD 0.02 higher (0.03 lower to 0.07 higher) | 2339 (11) | Moderate | Downgraded owing to indirectness |

| Plasma noradrenaline (assessed in children) | — | — | — | No studies assessed this outcome in children |

| Plasma noradrenaline‡ (assessed in adults; follow-up 1-2.5 months; units pg/mL; better indicated by lower values) | MD 8.23 higher (27.84 lower to 44.29 higher) | 265 (7) | Moderate | Downgraded owing to indirectness |

| Minor side effects (assessed in children) | — | — | — | No studies assessed this outcome in children |

| Minor side effects‡ (assessed in adults) | — | 249 (3) | — | No quantitative results available |

RR=risk ratio; MD=mean difference.

*Additional evidence from a meta-analysis of eight randomised controlled trials and non-randomised controlled trials with 12 comparisons measuring resting diastolic blood pressure was consistent with a benefit of reduced sodium on blood pressure (MD 0.87 mm Hg lower (1.60 to 0.14 lower))(quality of evidence low). One additional cohort study which could not be combined in meta-analysis was consistent with reduced diastolic blood pressure with reduced sodium intake in girls over time.

†A MD described as “lower” signifies a reduction in the outcome in the decreased sodium versus the higher sodium group.

‡Results from data collected in adults used as proxy for children.

Sensitivity analysis

As no studies in adults were considered to be at high risk of bias a sensitivity analysis for bias was not conducted. Removal of studies in people with comorbidities such as overweight, obesity, type 2 diabetes, or impaired glucose tolerance, or proteinuria had little effect on the results of the meta-analyses of blood pressure or adverse effects (data not shown).

Three cohort studies96,101,102 were removed from the analyses because of the high risk of confounding based on the measure of intake—that is, baseline sodium intake measured by one 24 hour dietary recall. The removal of these studies had little effect on any outcome.

When non-randomised studies were removed from the meta-analyses of controlled trials in children, the reduction in blood pressure was no longer significant (0.62 mm Hg, −0.25 to 1.5 mm Hg). The test for subgroup differences comparing the group of randomised controlled trials with the group of non-randomised controlled trials was not significant for systolic or diastolic blood pressure (P=0.14 and P=0.17, respectively). Removal of studies identified as being at high risk of bias reduced the total number of participants from 1278 to 527; none the less, a significant reduction in systolic blood pressure of 0.71mm Hg (0.07 to 1.35 mm Hg) was detected.

Discussion

The results from our meta-analyses of 36 randomised controlled trials in adults show that a reduction in sodium intake reduces systolic and diastolic blood pressure. These results are consistent with five previous systematic reviews that reported reduced sodium intake decreased blood pressure in adults with and without hypertension.8,16,17,18,19 The quality of the evidence was high. A body of evidence from randomised controlled trials begins the GRADE categorisation at high quality and is then assessed on a set of characteristics that may reduce that quality. This body of evidence was not downgraded as there was no indication of serious risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, or imprecision across all studies. As heterogeneity was suggested in the meta-analyses we carefully examined the results. The χ2 test suggested the potential for considerable heterogeneity (large χ2, P<0.001).29 However, a large number of studies, as in this review, often leads to the detection of a statistically significant χ2 test for heterogeneity and in such cases the test may not be meaningful because heterogeneity is inevitable.129 Therefore we also examined the forest plot and carried out the I2 test. Although both suggested some degree of heterogeneity, there was no considerable variation in results or inconsistency in the direction of the effect across studies. Furthermore, we investigated potential sources of heterogeneity by subgrouping based on numerous variables identified a priori during the development of the protocol. Subgrouping of studies based on these criteria resulted in reduced heterogeneity in most analyses. The results across the subgroup analyses were consistent with decreased sodium intake reducing blood pressure, suggesting that differences in the extent of the decrease in blood pressure caused by reduced sodium intake among studies, and not the overall direction of the effect, caused the heterogeneity.

Randomised controlled trials of four or more weeks’ duration showed no indication that reducing sodium intake had any adverse effects on blood lipids or catecholamine levels. These results were consistent with a previous systematic review when it considered only the studies of four or more weeks.18 There was also no indication of an adverse effect of reducing sodium intake on renal function, and the results were even suggestive of a beneficial effect. The quality of evidence for these outcomes in adults was high.

Subgroup analyses suggest that reduced sodium intake decreases blood pressure in people both with and without hypertension. The reduction in blood pressure was greater in those with hypertension; none the less, the benefit was evident in all groups. The relatively small effect of decreased sodium intake on blood pressure reduction in people without high blood pressure is consistent with a previous review.18 Nevertheless, a modest decrease in blood pressure can have important public health benefits. The health risk attributable to raised blood pressure is present across the entire population distribution of blood pressure.128 Raised blood pressure is the leading modifiable risk factor for mortality, accounting for almost 13% of deaths globally.2 In the United States, a decrease of 2 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure in the population could result in an estimated 17% decrease in the prevalence of hypertension, 6% decrease in risk of coronary heart disease, and 15% decrease in risk of stroke, and prevent an estimated 67 000 coronary heart disease events and 34 000 stroke events every year.130 Researchers estimate that a 5 mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure in the population of the United Kingdom could reduce the prevalence of hypertension by 50% in that country.131 Additionally, the relation between blood pressure and risk of vascular mortality is positive, strong, and linear down to a systolic blood pressure of 115 mm Hg, below which there is no evidence128; and most averted vascular events owing to small reductions in blood pressure across the entire distribution will occur among people with moderately raised blood pressure levels, including those within the normal range for prehypertension.132 Thus almost all reductions in blood pressure are beneficial for health, and modest population-wide reductions in blood pressure can result in important reductions in mortality, substantial health benefits, and meaningful savings in healthcare costs.2,3,134

The meta-analyses of controlled trials showed that a reduction in sodium intake significantly decreases systolic and diastolic blood pressure in children. These results were supported by the results of the one cohort study that met the inclusion criteria for the review. That study suggested a lesser increase in blood pressure with age in children who consume less sodium, but the relation was only significant for the sodium to potassium ratio and not the absolute level of sodium intake.113 The results are also consistent with two systematic reviews of studies in participants from birth to age 18 years.111,112 Because fewer than three high quality randomised controlled trials met our inclusion criteria, we reassessed the list of potential studies identified in the original search using expanded inclusion criteria that included a three rather than four week minimum study duration, no minimum difference in sodium intake between groups, no restriction on method of measuring sodium intake, and inclusion of non-randomised controlled trials. Including studies that reached the broader criteria reduced the quality of the evidence by increasing the risk of bias from inadequate random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and measurement of sodium intake. The inclusion of these studies would, however, bias the results towards the null because of a decrease in effect expected from studies of shorter duration and smaller difference in intake between intervention and control; as well as less ability to detect a difference because of the less precise measurement of sodium intake. None the less, we still detected a significant decrease in blood pressure with reduced sodium intake. Moreover, the sensitivity analysis showed that the results changed little when only higher quality studies were included. The reduction in blood pressure detected in children was small; however, such an effect sustained throughout childhood and adolescence could result in an appreciable reduction in blood pressure and prevalence of hypertension in adults.133,134 As diet related non-communicable diseases are chronic and take years or decades to manifest, delaying the onset of these diseases could improve quality of lives and have substantial cost savings.134 Thus by tackling the problem of raised blood pressure during childhood, reducing sodium intake can be a crucial component in reducing the increase in blood pressure with age135 and preventing hypertension and related non-communicable diseases that manifest later in life.

Some have voiced concerns that a reduction in sodium intake might lead to adverse health effects such as increased total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride, and catecholamine levels, as well as adverse changes in renal function or adverse effects on cardiovascular risk.18,28 Reducing sodium intake reduces blood volume and thus activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems (indicated by increased adrenaline and noradrenaline levels), which help control blood volume.27 A reduction in blood volume without a concurrent reduction in blood lipids would increase blood lipid levels acutely. Our meta-analysis of 11 randomised controlled trials, all of four or more weeks’ duration, showed that reducing sodium intake did not adversely affect blood lipids or catecholamine levels. A recent systematic review reported an increase in total cholesterol, triglyceride, adrenaline, and noradrenaline levels, as well as renin and aldosterone with reduced sodium intake.18 However, consistent with the results of the current review, those changes in blood lipids and catecholamine levels were no longer present in studies of more than four weeks’ duration. They were only detected in studies of two or less weeks’ duration, including extreme and severe changes in sodium intake.18 These results suggest that the contraction in volume and ensuing haemoconcentration seen after large and rapid changes in salt intake does not occur with more moderate and sustained salt reduction. The previous systematic review also reported changes in renin and aldosterone levels that persisted with longer term lower sodium intake. However, the importance of these changes is unclear.136,137. The data regarding the association between increased renin or aldosterone levels and cardiovascular disease are not consistent,138,139,140,141 and the relation seems to be more consistent in high risk patients than in the general population.136,137 Unlike blood pressure, a change in these hormones is not currently recognised as a reliable biomarker for predicting future risk of disease.127,128,137 Moreover, diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers are all potent blood pressure lowering agents that cause a sustained rise in renin and aldosterone levels and, nevertheless, significantly reduce stroke and other cardiovascular events. Because of this continued uncertainty about the usefulness of these biomarkers to predict cardiovascular events in the general population, in the current review we did not compile data on renin, angiotensin, or aldosterone but rather focused on blood pressure and cholesterol level, which each have a well recognised and widely accepted relation with future disease risk.127,128

Furthermore, our systematic review also investigated disease outcomes. The meta-analyses of 14 cohort studies detected an association between increased sodium intake and increased risk of stroke but no significant relation with risk of incident cardiovascular disease or coronary heart disease. These results are consistent with a previous review and meta-analysis, which found a significant direct association between sodium intake and risk of both stroke and cardiovascular disease.20 The previous review was completed in 2009 and we built on that body of evidence with the incorporation into the current review and meta-analyses of three more recently published studies. Furthermore, our meta-analysis of the effect of sodium intake on incidence of fatal disease detected a significant association between higher sodium intake and increased risk of fatal stroke and fatal coronary heart disease. Data from randomised controlled trials lacked sufficient power to detect a relation between sodium intake and the outcomes of interest from studies of that design.26 The body of evidence on the relation between sodium intake and patient relevant disease outcomes would be strengthened if results were obtained from more large and long term randomised controlled trials reporting mortality and morbidity.

Strengths and limitations of this review

Strengths of our review include the inclusion and synthesis of all available randomised controlled trial and epidemiological evidence on sodium intake for both positive and negative health outcomes; the transparent reporting of studies found, screened, and included and excluded; the evaluation of the entire body of evidence; the generation of overall effect estimates and conclusions across a large number and variety of studies; and the evaluation of the quality of evidence following the GRADE methodology.

Limitations include a limited number of outcomes, with the exclusion of acutely ill and special populations; and the constraints of the GRADE methodology on the low grading given to observational cohort studies. The GRADE methodology categorises a body of evidence from observational studies (for example, cohort studies) as low quality, and although the methodology liberally downgrades evidence it is conservative in upgrading evidence to a higher quality rating. Therefore the quality of evidence from cohort studies is almost exclusively low and very low using the GRADE methodology. Constraints on time and resources, as well as the deliberate scoping of the review to be relevant to public health guidance, led to the exclusion of cellular and animal studies and case studies on sodium intake and physiology. Likewise, outcomes that might be of interest, such as bone health or certain types of cancer, were also not included. Because the objective of the review was to inform the WHO guideline development process for the generation of a sodium intake guideline for most people globally, studies in unique populations such as patients with heart failure and other acute illnesses were also not included. The scoping of the review was completed in a systematic manner following the WHO guideline review committee handbook142 to ensure that all priority questions needed to review and potentially revise WHO guidelines on sodium intake were answered.

Conclusion

Our systematic review and meta-analyses show a clear benefit of lower sodium intake in both adults and children without acute illness. Overall results showed that a decrease in sodium intake reduced blood pressure. Although heterogeneity of the studies seemed to be considerable, subgroup analysis reduced such heterogeneity indicating that the effect is detectable in those with and without hypertension and, regardless of study design, sodium reduction achieved, blood pressure measurement method or device, or status of blood pressure drug use. Results from observational cohort studies also showed a significant association between sodium intake and all stroke, fatal stroke, and fatal coronary heart disease events. Owing to the study design, the quality of the evidence was not as high as that for blood pressure. Ideally, randomised controlled trials with these disease outcomes would be needed to strengthen the evidence base. Finally, we showed that a lower sodium intake has no adverse effect on blood lipids, catecholamine levels, or renal function.

What is already known on this topic

Increased sodium intake increases blood pressure and, according to WHO data, raised blood pressure is the number one modifiable risk factor for mortality

Systematic reviews have reported that lower sodium intake results in decreased blood pressure

Research suggests that lower sodium intake is associated with decreased risk of incident stroke and cardiovascular disease but whether there are adverse effects on blood lipids, catecholamine levels, and renal function is uncertain

What this study adds

This systematic review and meta-analyses found that lowering sodium intake reduces blood pressure in adults and children and has no adverse effect on blood lipids, catecholamine levels, or renal function

A synthesis of evidence including findings from recent cohort studies showed a positive association between sodium intake and incident stroke, fatal stroke, and fatal coronary heart disease events

This review evaluates the evidence using the GRADE methodology and generates conclusions based on the entirety of the compiled evidence in both adults and children

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Supplementary materials

We thank the members of the WHO Nutrition Guidance Expert Advisory Group (WHO NUGAG) for their input and comments on the manuscript; the stakeholders who provided their feedback on scoping the review; and Sharnali Das for screening manuscripts for inclusion and data extraction. PE is a senior investigator for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. FPC and JJM contributed equally to the study.

Contributors: The priority questions to be addressed for the review were discussed and developed by the WHO NUGAG Subgroup on Diet and Health in March 2011 and the protocol was subsequently developed to address the requested questions by the WHO NUGAG Subgroup on Diet and Health. NJA and AZ ran the searches, carried out the assessment of papers for inclusion, extracted data, did the validity assessment, and prepared the first draft of the report submitted for review by the WHO NUGAG Subgroup on Diet and Health. NJA completed the data analyses. NJA and JM developed the first GRADE evidence profiles. The WHO NUGAG Subgroup on Diet and Health reviewed earlier drafts and contributed to the analysis and GRADE assessment. NJA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LH, PE, FPC, and JJM provided substantial intellectual input on research methods and interpretation of results. All authors read, provided input, and agreed the final draft of the manuscript. WHO agreed with the publication of this systematic review in a scientific journal as it serves as the background evidence review for updating the WHO guideline on sodium intake for adults and for the establishment of a guideline on sodium intake in children and should therefore be widely available.

Funding: This review was supported by WHO funds, the Kidney Evaluation Association Japan, and the governments of Japan and Republic of Korea.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: LH, FPC, PE, and JJM received funding from WHO to attend NUGAG Subgroup of Diet and Health meetings, PE receives support from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London, FPC is an unpaid member of Consensus Action on Salt and Health (CASH), World Action on Salt and Health (WASH), unpaid advisor to the WHO and the PAHO, a member of the National Heart Forum and former member of the executive committee and trustee of the British Hypertension Society, PE is an unpaid member of CASH, WASH, and an unpaid advisor to WHO; no further financial support from any organisation for the submitted work that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. NJA was a staff member of WHO at the time this work was conducted. The author alone is responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of WHO.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: The datasets are available from the corresponding author at nancy.aburto@wfp.org.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f1326

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. WHO, 2010:164.

- 2.World Health Organization. Global health risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. WHO, 2009:62.

- 3.Mackay J, Mensah G. The atlas of heart disease and stroke. WHO, 2004.

- 4.World Health Organization. World health statistics 2012. WHO, 2012:176.

- 5.Elliott P, Stamler J, Nichols R, Dyer AR, Stamler R, Kesteloot H, at al for the INTERSALT Cooperative Research Group. INTERSALT revisited: further analyses of 24 hour sodium excretion and blood pressure within and across populations. BMJ 1996;312:1249-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutler JA, Follmann D, Allender PS. Randomized trials of sodium reduction: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65(suppl 2):S643-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He FJ, MacGregor GA. How far should salt intake be reduced? Hypertension 2003;42:1093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He FJ, MacGregor GA. Effect of longer-term modest salt reduction on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD004937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic disease. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. WHO, 2003.

- 10.Holbrook JT, Patterson KY, Bodner JE, Douglas LW, Veillon C, Kelsay JL, et al. Sodium and potassium intake and balance in adults consuming self-selected diets. Am J Clin Nutr 1984;40:786-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taal MW, Chertow GM, Marsden PA, Skorecki K, Yu ASL, Brenner BM, et al. Brenner and Rector’s the kidney. Saunders Elsevier, 2011.

- 12.He FJ, MacGregor GA. A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J Hum Hypertens 2009;23:363-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, Elliott P. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:791-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: guidelines for assessment and management of cardiovascular risk. WHO, 2007.

- 15.Anderson CAM, Appel LJ, Okuda N, Brown IJ, Chan QE, Zhao LC, et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP Study. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:736-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Cook JV. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens 2006;24:215-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Adults and sodium: what is the relationship between sodium and blood pressure in adults aged 19 years and older? Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Agriculture, 2010.

- 18.Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(11):CD004022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooper L, Bartlett C, Davey SG, Ebrahim S. Advice to reduce dietary salt for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(1):CD003656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2009;339:b4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Donnell MJ, Yusuf S, Mente A, Gao P, Mann JF, Teo K, et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion and risk of cardiovascular events. JAMA 2011;306:2229-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Kuznetsova T, Thijs L, Tikhonoff V, Seidlerová J, Richart T, et al. Fatal and nonfatal outcomes, incidence of hypertension, and blood pressure changes in relation to urinary sodium excretion. JAMA 2011;305:1777-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell N, Cappuccio FP, Tobe SW. Unnecessary controversy regarding dietary sodium. A lot about a little. Can J Cardiol 2011;27:404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell N, Correa-Rotter R, Neal B, Cappuccio FP. New evidence relating to the health impact of reducing salt intake. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011;21:617-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He FJ, Appel LJ, Cappuccio FP, de Wardener HE, MacGregor GA. Does reducing salt intake increase cardiovascular mortality? Kidney Int 2011;80:696-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor RS, Ashton KE, Moxham T, Hooper L, Ebrahim S. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(7):CD009217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alderman MH, Cohen HW. Dietary sodium intake and cardiovascular mortality: controversy resolved? Curr Hypertens Rep 2012;14:193-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alderman MH. Reducing dietary sodium: the case for caution. JAMA 2010;303:448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- 30.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]