Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is an important global health problem worldwide. There is still scarce information on the population structure of S. aureus strains in Asia, where the majority of the world population lives. This study characterized the diversity of S. aureus strains in northern Vietnam through multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Eighty-five carriage isolates from the community and 77 invasive isolates from the clinical setting were selected and tested for meticillin resistance and the presence of Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL). MLST was performed on these isolates, of which CC59 (25.4 %), CC188 (17.3 %) and CC45 (16.7 %) were the predominant clonal complexes (CCs). CC59 carriage isolates had significantly lower rates of meticillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) than their corresponding clinical group isolates (32 vs 83 %). There were no significant differences in rates of MRSA between carriage isolates and clinical isolates of CC45 and CC188. CC59 carriage isolates were significantly lower in rates of PVL+ than CC59 clinical isolates (32 vs 83 %), but the converse was shown in CC45 isolates (14 vs 0 %, respectively). This study revealed vast differences in the molecular epidemiology and population structure of S. aureus in community and clinical settings in Vietnam. Nevertheless, the data underline the spread of virulent and/or resistant strains (MRSA and/or PVL+) in the community, suggesting the necessity for further surveillance to determine the mechanism of transmission of these strains (i.e. MRSA/PVL+) outside clinical settings.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a common bacterium that colonizes about 20–30 % of the human population but can also cause a variety of infections from localized to systemic, including skin infections, deep abscesses, endocarditis, pneumonia and sepsis (Wertheim et al., 2005a; van Belkum et al., 2009; Gonzalez et al., 2005). In many cases, carriage of specific S. aureus strains is associated with subsequent infection when the opportunity arises (Wertheim et al., 2005a). Worldwide there has also been an increase in meticillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), with a shift from being mainly a hospital-acquired pathogen to a common cause of community-acquired skin and soft tissue infections (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999; Witte et al., 1997; Udo et al., 1993). In Vietnam, outbreaks of severe community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) infections have occurred, as reported among nine children in 2006 (Tang et al., 2007). Another report revealed that 19 % of S. aureus bloodstream infections from Vietnam were methicillin resistant and often not managed well (Song et al., 2011). This is relevant because significantly heightened mortality has been associated with MRSA bloodstream infection compared with meticillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) infection (Cosgrove et al., 2003).

In order to understand the clinical epidemiology of S. aureus and the spread of antibiotic resistance, it is important to investigate the overall population structure of S. aureus for both colonizing and invasive isolates. Considering that the majority of the global population lives in Asia and that S. aureus is a common pathogen throughout this continent, more data are needed from this region. Several molecular methods have been developed to compare S. aureus populations in various regions, of which multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and S. aureus protein A (spa) typing are the most commonly used (Tenover et al., 2006; Enright et al., 2000; Kondo et al., 2007). Through MLST, different clonal complexes (CCs) have been found to predominate in a variety of geographical regions. Clinical studies conducted in Asian countries have found that sequence type 59 (ST59), ST30 and ST72 dominate over MRSA in both community- and hospital-acquired isolates (Song et al., 2011). In the current Vietnamese study, we aimed to identify and describe the major S. aureus CCs, the meticillin resistance and the presence of the virulence determinant, Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) in isolates from invasive bloodstream infections and compare these with carriage isolates in urban and rural healthy individuals in the catchment area of the hospital.

Methods

Sample collection

From February to May 2012, samples were collected from healthy individuals living in the Dong Da and Ba Vi districts in northern Vietnam (community setting). Dong Da district is an urban district with a population of 352 000 people and a typical urban Vietnamese socioeconomic structure. Ba Vi is a rural district with farming as the main occupation. Nasal swabs of the anterior nares and throat swabs of the posterior pharynx and tonsillar areas were collected using sterile Dacron swabs (Copan, Italy). Subsequently, all swabs were transported in bacterial transport medium to the microbiological laboratory of the National Hospital of Tropical Diseases (NHTD) within 24 h of collection time and were plated on agar for pathogen identification as described previously (Van Nguyen et al., 2014). Clinical invasive S. aureus isolates were obtained from positive blood cultures in the period from November 2009 to December 2012 from patients admitted to NHTD as described elsewhere (Thwaites, 2010). A total of 591 S. aureus isolates [216 nasal swabs (36.5 %); 293 throat swabs (49.5 %); 82 blood samples (13.9 %)] were collected, from which 162 S. aureus isolates, one per individual, were randomly selected for this study (85 carriage isolates and 77 invasive ones).

Microbiology

Blood cultures were performed at NHTD using the automated Bactec system (Becton Dickinson). In the case of a positive blood culture, Gram staining and a subculture on Columbia blood agar were performed. Nasal and throat swabs were cultured on phenyl mannitol agar plates (Oxoid). Suspected S. aureus colonies from blood and swab cultures were identified by colony morphology, Gram stain, and coagulase and catalase testing. Meticillin resistance was determined by cefoxitin disk diffusion on Mueller–Hinton agar plates according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute criteria (CLSI, 2012).

Molecular testing and typing

S. aureus identity and meticillin resistance were confirmed by PCR amplification of the coagulase gene and mecA gene, as described elsewhere (Sabet et al., 2007). We also tested for the presence of the PVL gene by PCR according to a previously described method (McClure et al., 2006).

MLST was performed on the 162 selected isolates using the protocol and primers described on the MLST website for S. aureus (http://saureus.mlst.net) (Enright et al., 2000). The allelic profiles were identified based on this database, and the STs were then classified into CCs by the eBURST version 3 program (http://saureus.mlst.net/eburst/, accessed 20 July 2014). STs that shared at least six identical alleles of seven MLST loci were grouped in a CC according to the most stringent definition in the eBURST program.

Data analysis

Univariate analysis was performed using Pearson's χ2 test and Fisher's exact test where appropriate. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. All calculations were performed using r (version 3.0.1).

Phylogenetic analysis

We examined phylogenetic relationships among the 162 isolates using the data from all seven genetic regions, concatenated into a single sequence (no partitioning between regions). The sequences were aligned using clustal Omega, as implemented in SeaView (Galtier et al., 1996; Sievers et al., 2011). Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis was implemented with PhyML (version 3.0), using a generalized time reversible mutation model (Guindon et al., 2010). Bootstrap support was determined using 100 replicates. The resulting tree was then viewed in SeaView for subsequent analysis.

Results

Study population and S. aureus population structure

Of the 162 isolates on which molecular typing (MLST) was performed, 27 (16.7 %) were from females and 111 (68.6 %) were from males [there were no data on gender for 24 isolates (14.8 %)]. Samples were from participants ranging in age from 3 to 87 years. The median age was 29 years (interquartile range 13.5–41.5; Table 1). Fifty-three of the 162 MLST typed isolates were MRSA (32.7 %) and 109 strains were MSSA (67.3 %). The number of MRSA isolates was 28 (32.9 %) and 23 (29.9 %) in the carriage group (Dong Da and Ba Vi) and invasive group (NHTD), respectively. The PVL gene was present in 19 (22.4 %) of 85 carriage isolates and in 25 (32.5 %) of 77 invasive isolates (P = 0.16).

Table 1. Population profiles by study site.

| Study site | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Dong Da (n = 31; nasopharyngeal swabs) | Ba Vi (n = 54; nasopharyngeal swabs) | NHTD (n = 77; blood isolates) |

| Female/male (%) | 25.8/54.8 | 24.1/59.3 | 7.8/80.5 |

| Age [median (interquartile range)] | 13 (9–23) | 17 (11–37) | 36 (28–49) |

| MRSA (%) | 19.4 | 40.7 | 32.5 |

| PVL+(%) | 19.4 | 22.2 | 33.8 |

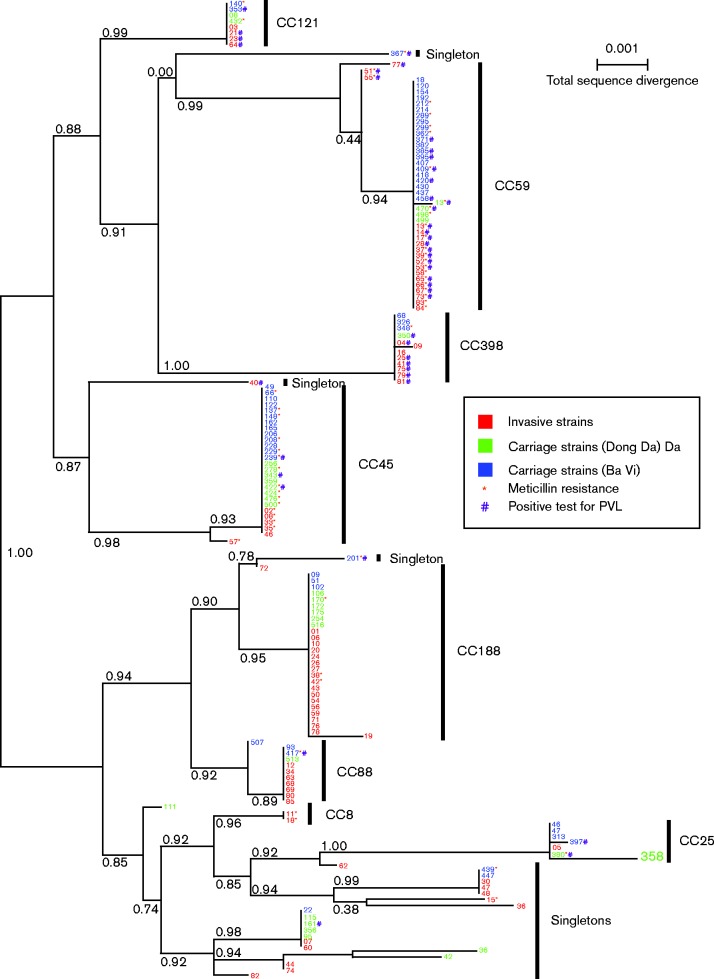

Overall, 29 different STs were detected, including 12 singleton STs (Table 2, Fig. 1). The most dominant CCs were CC59 (43 isolates, 26.5 %), CC188 (28 isolates, 17.3 %), CC45 (27 isolates, 16.7 %), followed by CC88 (11 isolates, 6.8 %), CC398 (12 isolates, 7.4 %), CC25 (seven isolates, 4.3 %), CC121 (eight isolates, 4.9 %) and CC8 (three isolates, 1.9 %). Singletons consisted of 23 isolates (14.2 %).

Table 2. Molecular attributes of the S. aureus isolates.

| CC | ST (n) | Total isolates [n (%)] | Carriage isolates | Invasive isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA/MSSA | PVL+/PVL− | MRSA/MSSA | PVL+/PVL− | |||

| CC188 | ST188 (27), ST2393 (1) | 28 (17.3) | 1/8 | 0/9 | 2/17 | 0/19 |

| CC8 | ST8 (1), ST239 (2) | 3 (1.9) | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/0 | 0/2 |

| CC25 | ST25 (6), ST1029 (1) | 7 (4.3) | 1/5 | 2/4 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| CC45 | ST45 (26), ST546 (1) | 27 (16.7) | 11/10 | 3/18 | 5/1 | 0/6 |

| CC59 | ST59 (39), ST338 (1), ST537 (2), ST3069 (1) | 43 (26.5) | 8/17 | 8/17 | 15/3 | 15/3 |

| CC88 | ST88 (10), ST2141 (1) | 11 (6.8) | 1/3 | 1/3 | 0/7 | 0/7 |

| CC121 | ST121 (7), ST1964 (1) | 8 (4.9) | 2/2 | 1/3 | 0/4 | 3/1 |

| CC398 | ST398 (1), ST1232 (11) | 12 (7.4) | 1/3 | 1/3 | 0/8 | 6/2 |

| Singleton | 23 (14.2) | |||||

| ST5 | 1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0 | 0 | |

| ST6 | 7 | 0/5 | 1/4 | 0/2 | 0/2 | |

| ST9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/1 | 0/1 | |

| ST7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/1 | 0/1 | |

| ST15 | 5 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 0/3 | 0/3 | |

| ST72 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0/2 | 0/2 | |

| ST97 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/1 | 0/1 | |

| ST285 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0/1 | 1/0 | |

| ST406 | 1 | 1/0 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ST834 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/0 | 0/1 | |

| ST942 | 1 | 1/0 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ST1281 | 1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 162 (100 %) | 28/57 | 19/66 | 25/52 | 25/52 | |

Fig. 1.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree for the 162 samples with full datasets. Samples labelled in blue are carriage strains from rural Ba Vi and in green are from urban Dong Da; samples labelled in red are invasive hospital strains. An asterisk indicates meticillin resistance and # indicates presence of PVL. Numbers to the right of the vertical black bars indicate clonal complex designation. Numbers along the branches indicate branch support based on 100 bootstrap replicates. Bar, 0.1 % total sequence divergence.

CC45 isolates were more common across carriage isolates compared with invasive isolates (24.7 % for carriage isolates vs 7.8 % for invasive isolates; P = 0.002). No significant difference was found between the rate of CC59 carriage (29.4 %) and CC59 invasive (23.4 %) isolates. However, relatively more CC59 isolates were found in the rural (i.e. Ba Vi) carriage group (67.7 %), as compared to the urban (i.e. Dong Da) carriage group (7.4 %; P < 0.001). CC188 isolates displayed significantly higher rates in invasive isolates (29.4 %) compared with carriage isolates (7.7 %; P < 0.001).

Both carriage and invasive strains broadly co-occurred in our phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the tree clearly showed that some CCs were more present in invasive samples such as CC398, CC188 and CC88, whereas CC59 and CC45 were more present in the carriage samples. Both meticillin resistance and the presence of PVL were also distributed broadly across the phylogeny but with a distribution depending on the CC and on the invasive versus carriage status. For example, MRSA/PVL+ isolates were more prevalent in invasive CC59 samples, whereas CC188 isolates did not have any samples that were PVL+.

Distribution of MRSA among CCs

Of the total number of MRSA isolates, CC59 had the most MRSA isolates (23/53 isolates, 43.4 %), and of MSSA isolates, CC188 was the most predominant (25/109 isolates, 22.9 %) (Table 2, Fig. 1). There were differences between invasive and carriage strains within specific CCs. MRSA was more common among invasive CC59 isolates (n = 15, 83.3 %) compared with CC59 carriage group isolates (n = 8, 32.0 %; P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in number of MRSA isolates between invasive and carriage CC45 and CC188 isolates (P>0.05). Nevertheless, five out of the six CC45 invasive isolates were MRSA (83.3 %) whereas 11 out of 21 CC45 carriage isolates were MRSA (52.4 %; P = 0.2). To characterize the population structure of invasive MRSA and MSSA, we tested for differences among isolates from CC45, CC59 and CC188. Invasive MRSA and MSSA isolates displayed significant differences between CC45, CC59 and CC188 (P < 0.001). There were five (83.3 %) invasive MRSA and one (16.7 %) invasive MSSA CC45 isolates, 15 (83.3 %) invasive MRSA and three (16.7 %) invasive MSSA CC59 isolates, and finally two (10.5 %) invasive MRSA and 17 (89.5 %) invasive MSSA CC188 isolates.

Distribution of PVL among CCs, MRSA and invasive versus carriage isolates

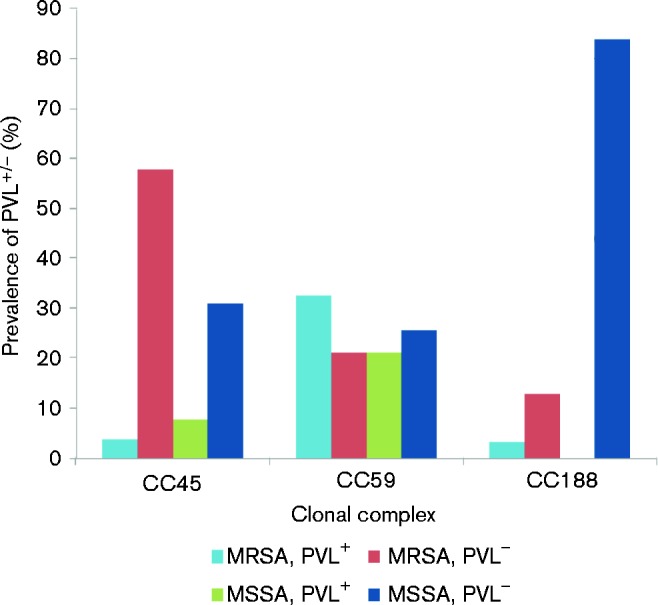

The prevalence of PVL+ isolates differed among CCs (Table 2, Figs 1 and 2). PVL in the invasive strains was most commonly found in CC59 (15 isolates, 19.4 %), CC398 (six isolates, 7.8 %) and CC121 (three isolates, 3.9 %). PVL distribution in the carriage isolates was found mainly in CC59 (eight isolates, 9.8 %). The prevalence of PVL+ and PVL− isolates was significantly different across CC45, CC59 and CC188 (P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of PVL among MRSA and MSSA CC45, CC59 and CC188 isolates.

There was a statistical difference in the proportion of PVL+ isolates between MSSA and MRSA: 21/53 (39.6 %) MRSA isolates and 24/109 (22.0 %) MSSA isolates were positive for the luk gene encoding PVL (P = 0.005; Fig. 2). Of the 21 PVL+ MRSA isolates, 15 (71.4 %) belonged to CC59, and the remaining six isolates were distributed among a total of four CCs, comprising ST406, CC25, CC45 and CC88. The PVL+ MRSA isolates in the carriage group were not significantly higher than in the invasive group.

There were also significant differences in the proportion of PVL+ isolates between invasive and carriage groups according to the CC. There were significantly higher rates of invasive PVL+ CC59 isolates (15 isolates, 83.3 %) than carriage PVL+ CC59 isolates (eight isolates, 32.0 %) (P < 0.001). The same trend (P < 0.001) was shown in CC398 : six invasive PVL+ CC398 isolates (75.0 %) and one carriage PVL+ CC398 isolate (25.0 %). On the other hand, there were significantly lower rates of invasive PVL+ CC45 isolates (0 isolates, 0 %) than carriage PVL+ CC45 isolates (three isolates, 14.3 %) (P < 0.001). The same trend (P < 0.001) was shown in CC88: no invasive PVL+ CC88 isolates (0 %) and one carriage PVL+ CC88 isolate (33.3 %).

Discussion

Here, we have provided data on the population structure of MRSA and MSSA in both carriage and invasive disease isolates in northern Vietnam. Most previous studies conducted in East Asian countries on S. aureus have focused on MRSA infections and either clinical or carriage isolates. We found a high level of genetic diversity in colonizing and invasive S. aureus strains. The most dominant S. aureus CCs detected in our collection were CC59, CC45 and CC188. All invasive CCs were also represented in carriage isolates, showing that community-acquired invasive S. aureus will be challenging to prevent. CC59 was particularly prevalent among both carriage and clinical isolates. CC45 and CC25 were more common among carriage compared with invasive isolates. CC188 was more common among invasive strains.

In other Asian studies, CC30, CC59 and ST239 have been reported to be dominant CCs (Sheng et al., 2009; Song et al., 2011; Feil et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2013). In Europe, ST80, ST398 and ST152 are the predominant STs in CA-MRSA. In North America, USA300 (ST8) and USA400 (ST1) prevail. Interestingly, we did not find any ST30, ST80 or USA400 isolates in our study. A report from Japan has shown several cases of ST8 (USA300) CA-MRSA infection in Asia (Shibuya et al., 2008). Only one ST8 isolate was detected in our study, which was susceptible to meticillin.

A multinational study in Asia revealed that MRSA infections in the community are increasing in Asian countries (Song et al., 2011). In 2006, there was an outbreak of severe CA-MRSA infections of ST59 in southern Vietnam following routine vaccination injections (Tang et al., 2007). This is in agreement with our results, as CC59 was predominant in our study with a high proportion of MRSA and PVL+ isolates in invasive but also in carriage isolates. These data suggest that CC59 is widely spread, invasive in nature and commonly resistant in Vietnam, and thus appears as the most worrying CC in this country. This CC was also recently reported as a predominant clone associated with S. aureus infections in Chinese children as well as adults in Taiwan and Sri Lanka (Geng et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013; Du et al., 2011). It is possible that CC59 is currently spreading between adjacent regions, supporting its dominance in the Asian region as a whole.

CC45 was the second most frequent CC in our study, particularly among carriage isolates, with a high proportion of MRSA. Throughout Germany, the Netherlands and Canada, CC45 is common in both carriage and disease (Wannet et al., 2004; Witte et al., 1997; Simor et al., 2002; Wertheim et al., 2005b). In a report from the USA in 2010, USA600 (ST45) MRSA caused bloodstream infection with a high rate of mortality but with low carriage rates in community. The study suggested that unique virulent characteristics might be involved in USA600 bloodstream infections, which were not assessed in our study (Moore et al., 2010). The relative low proportion of invasive CC45 isolates in our study and the absence of PVL suggest that CC45 is predominantly a colonizer in Vietnam. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that the majority of the CC45 invasive strains were MRSA, and thus the spread of this CC in Vietnam needs to be followed.

The third main CC in our study, CC188, is a double locus variant of ST1. In contrast to CC45, 19/27 (70.3 %) of CC188 isolates were found in the invasive clinical group with low levels of meticillin resistance. This CC seems to weakly spread in the community in Vietnam, suggesting the source of transmission is clinical settings. CC188 has not been reported as a dominant CC in most other countries, such as Malaysia, Europe, America and Australia (Ghaznavi-Rad et al., 2010; Otter and French, 2010; Wertheim et al., 2005b; Rolo et al., 2012; Nimmo and Coombs, 2008). Studies in Korea, Hong Kong and Malaysia only sporadically found ST188 isolates in the MRSA population (Ghaznavi-Rad et al., 2010; Peck et al., 2009; Monecke et al., 2011). Only in Taiwan has CC1 been reported as one of the four major CCs (Wang et al., 2012).

Concerning CC398, we detected ST1232, which is a single locus variant of ST398. CC398 MRSA is considered a zoonotic pathogen, mainly affecting people who work with pigs and veal calves (van Loo et al., 2007). Nevertheless, in numerous countries, MSSA CC398 has now been identified in healthcare workers and patients without exposure to livestock but also in the environment of a French intensive care unit, indicating the capacity for emergence of this clone in hospitals (Brunel et al., 2014). Thus, this clone may cause a significant public health problem if it can spread successfully from human to human (de Neeling et al., 2007; Cuny et al., 2009; Wassenberg et al., 2011). Eight out of 12 (66.7 %) CC398 MSSA isolates were from clinical disease, suggesting that zoonotic CC398 S. aureus is also causing human disease in Vietnam, an agricultural country. In addition, 75 % of the CC398 MSSA clinical isolates tested positive for the presence of PVL, emphasizing their virulence.

Previous studies have reported the presence of the PVL gene in many different S. aureus CCs: CC59, CC88, CC30, CC45, CC1, CC80, CC22 and CC398 (Monecke et al., 2007; Otter and French, 2010). The prevalence of MRSA containing the PVL gene is also very diverse according to the region. In Asia, the prevalence of the PVL gene in CA-MRSA and hospital-acquired MRSA was found to be 14.3 and 5.7 %, respectively (Song et al., 2011). In Taiwan, 28 (11.1 %) of 253 MRSA strains from bloodstream infection harboured PVL, while nine (7.1 %) of 126 community-onset MRSA isolates were PVL+ (Wang et al., 2010a, b). In a study of 100 S. aureus isolates from diverse cases of skin and soft tissue infection at a university hospital in Germany, 30 isolates were positive for the genes encoding PVL and three of them were MRSA (Monecke et al., 2007). In this study, the proportion of isolates containing PVL was 22.3 and 32.4 % in the carriage and clinical groups, respectively. These proportions are higher than in previous reports and than in a recent study carried out in China (Li et al., 2013). Indeed, Li et al. (2013) reported 55.5 % of CC59 MRSA strains to be PVL+ in mainland China, whereas we detected 61.9 % of CC59 MRSA as PVL+ in northern Vietnam.

It is worth noting that this study had several limitations. The S. aureus isolates used for this study were obtained from two health centres and a hospital in Hanoi in northern Vietnam, and thus no generalization can be made at a national scale. Further studies should offer a more comprehensive analysis of the molecular epidemiology of S. aureus throughout the country and possibly other Asian countries. In addition, further studies in Vietnam should examine the drivers of the emergence of invasive CCs and develop strategies to control the spread of virulent clones. Additionally, it would be of interest to include the clinical outcome of patients with invasive S. aureus disease in future studies.

In conclusion, we found that the population structure of S. aureus in northern Vietnam is different from that in other Asian countries and also from high-income countries such as Europe and the USA. The predominant CCs of S. aureus in our study were CC59, CC45 and CC188 MSSA. CC59 was widespread among both carriage and invasive isolates with a high proportion of MRSA and PVL virulence. It is thus essential to continue S. aureus surveillance with genotyping in Asia on a larger scale and to report trends in invasiveness and drug resistance over time.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust Major Overseas Programme Vietnam. The funder had no role in the design of the study, or in the decision to draft the paper or to submit. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations:

- CA

community-acquired

- CC

clonal complex

- MLST

multilocus sequence typing

- MRSA

meticillin-resistant S. aureus

- MSSA

meticillin-sensitive S. aureus

- NHTD

National Hospital of Tropical Diseases

- PVL

Panton–Valentine leukocidin

- ST

sequence type

References

- Brunel A. S., Bañuls A. L., Marchandin H., Bouzinbi N., Morquin D., Jumas-Bilak E., Corne P. (2014). Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus CC398 in intensive care unit, France Emerg Infect Dis 20 1511–1515 10.3201/eid2009.130225 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Four pediatric deaths from community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus — Minnesota and North Dakota, 1997–1999 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 48 707–710 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wang W. K., Han L. Z., Liu Y., Zhang H., Tang J., Liu Q. Z., Huangfu Y. C., Ni Y. X. (2013). Epidemiological and genetic diversity of Staphylococcus aureus causing bloodstream infection in Shanghai, 2009–2011 PLoS One 8 e72811 10.1371/journal.pone.0072811 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2012). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests; Approved Standard 11th edn M02-A11 Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove S. E., Sakoulas G., Perencevich E. N., Schwaber M. J., Karchmer A. W., Carmeli Y. (2003). Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis Clin Infect Dis 36 53–59 10.1086/345476 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuny C., Nathaus R., Layer F., Strommenger B., Altmann D., Witte W. (2009). Nasal colonization of humans with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) CC398 with and without exposure to pigs PLoS One 4 e6800 10.1371/journal.pone.0006800 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Neeling A. J., van den Broek M. J., Spalburg E. C., van Santen-Verheuvel M. G., Dam-Deisz W. D., Boshuizen H. C., van de Giessen A. W., van Duijkeren E., Huijsdens X. W. (2007). High prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pigs Vet Microbiol 122 366–372 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.01.027 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Chen C., Ding B., Tu J., Qin Z., Parsons C., Salgado C., Cai Q., Song Y., other authors (2011). Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility of nasal Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a Chinese medical college campus PLoS One 6 e27328 10.1371/journal.pone.0027328 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright M. C., Day N. P., Davies C. E., Peacock S. J., Spratt B. G. (2000). Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus J Clin Microbiol 38 1008–1015 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil E. J., Nickerson E. K., Chantratita N., Wuthiekanun V., Srisomang P., Cousins R., Pan W., Zhang G., Xu B., other authors (2008). Rapid detection of the pandemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone ST 239, a dominant strain in Asian hospitals J Clin Microbiol 46 1520–1522 10.1128/JCM.02238-07 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier N., Gouy M., Gautier C. (1996). seaview phylo_win: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny Comput Appl Biosci 12 543–548 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng W., Yang Y., Wu D., Huang G., Wang C., Deng L., Zheng Y., Fu Z., Li C., other authors (2010). Molecular characteristics of community-acquired, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Chinese children FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 58 356–362 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez B. E., Martinez-Aguilar G., Hulten K. G., Hammerman W. A., Coss-Bu J., Avalos-Mishaan A., Mason E. O., Jr, Kaplan S. L. (2005). Severe staphylococcal sepsis in adolescents in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pediatrics 115 642–648 10.1542/peds.2004-2300 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. (2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0 Syst Biol 59 307–321 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y., Ito T., Ma X. X., Watanabe S., Kreiswirth B. N., Etienne J., Hiramatsu K. (2007). Combination of multiplex PCRs for staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type assignment: rapid identification system for mec, ccr, and major differences in junkyard regions Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51 264–274 10.1128/AAC.00165-06 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang L., Ip M., Sun M., Sun J., Huang G., Wang C., Deng L., Zheng Y., other authors (2013). Molecular and clinical characteristics of clonal complex 59 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in mainland China PLoS One 8 e70602 10.1371/journal.pone.0070602 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure J. A., Conly J. M., Lau V., Elsayed S., Louie T., Hutchins W., Zhang K. (2006). Novel multiplex PCR assay for detection of the staphylococcal virulence marker Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes and simultaneous discrimination of methicillin-susceptible from -resistant staphylococci J Clin Microbiol 44 1141–1144 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1141-1144.2006 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monecke S., Slickers P., Ellington M. J., Kearns A. M., Ehricht R. (2007). High diversity of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive, methicillin-susceptible isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and implications for the evolution of community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus Clin Microbiol Infect 13 1157–1164 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01833.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monecke S., Coombs G., Shore A. C., Coleman D. C., Akpaka P., Borg M., Chow H., Ip M., Jatzwauk L., other authors (2011). A field guide to pandemic, epidemic and sporadic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus PLoS One 6 e17936 10.1371/journal.pone.0017936 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. L., Osaki-Kiyan P., Perri M., Donabedian S., Haque N. Z., Chen A., Zervos M. J. (2010). USA600 (ST45) methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections in urban Detroit J Clin Microbiol 48 2307–2310 10.1128/JCM.00409-10 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmo G. R., Coombs G. W. (2008). Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Australia Int J Antimicrob Agents 31 401–410 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.08.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otter J. A., French G. L. (2010). Molecular epidemiology of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe Lancet Infect Dis 10 227–239 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70053-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck K. R., Baek J. Y., Song J. H., Ko K. S. (2009). Comparison of genotypes and enterotoxin genes between Staphylococcus aureus isolates from blood and nasal colonizers in a Korean hospital J Korean Med Sci 24 585–591 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.4.585 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolo J., Miragaia M., Turlej-Rogacka A., Empel J., Bouchami O., Faria N. A., Tavares A., Hryniewicz W., Fluit A. C., de Lencastre H., CONCORD Working Group (2012). High genetic diversity among community-associated Staphylococcus aureus in Europe: results from a multicenter study PLoS One 7 e34768 10.1371/journal.pone.0034768 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabet N. S., Subramaniam G., Navaratnam P., Sekaran S. D. (2007). Detection of methicillin- and aminoglycoside-resistant genes and simultaneous identification of S. aureus using triplex real-time PCR Taqman assay J Microbiol Methods 68 157–162 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.07.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng W. H., Wang J. T., Lauderdale T. L., Weng C. M., Chen D., Chang S. C. (2009). Epidemiology and susceptibilities of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Taiwan: emphasis on chlorhexidine susceptibility Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 63 309–313 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.11.014 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya Y., Hara M., Higuchi W., Takano T., Iwao Y., Yamamoto T. (2008). Emergence of the community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 clone in Japan J Infect Chemother 14 439–441 10.1007/s10156-008-0640-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D., Gibson T. J., Karplus K., Li W., Lopez R., McWilliam H., Remmert M., other authors (2011). Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega Mol Syst Biol 7 539 10.1038/msb.2011.75 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simor A. E., Ofner-Agostini M., Bryce E., McGeer A., Paton S., Mulvey M. R., Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee and Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program, Health Canada (2002). Laboratory characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canadian hospitals: results of 5 years of National Surveillance, 1995-1999 J Infect Dis 186 652–660 10.1086/342292 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. H., Hsueh P. R., Chung D. R., Ko K. S., Kang C. I., Peck K. R., Yeom J. S., Kim S. W., Chang H. H., other authors (2011). Spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus between the community and the hospitals in Asian countries: an ANSORP study J Antimicrob Chemother 66 1061–1069 10.1093/jac/dkr024 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C. T., Nguyen D. T., Ngo T. H., Nguyen T. M., Le V. T., To S. D., Lindsay J., Nguyen T. D., Bach V. C., other authors (2007). An outbreak of severe infections with community-acquired MRSA carrying the Panton-Valentine leukocidin following vaccination PLoS One 2 e822 10.1371/journal.pone.0000822 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover F. C., McDougal L. K., Goering R. V., Killgore G., Projan S. J., Patel J. B., Dunman P. M. (2006). Characterization of a strain of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus widely disseminated in the United States J Clin Microbiol 44 108–118 10.1128/JCM.44.1.108-118.2006 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thwaites G. E., United Kingdom Clinical Infection Research Group (UKCIRG) (2010). The management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in the United Kingdom and Vietnam: a multi-centre evaluation PLoS One 5 e14170 10.1371/journal.pone.0014170 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo E. E., Pearman J. W., Grubb W. B. (1993). Genetic analysis of community isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Western Australia J Hosp Infect 25 97–108 10.1016/0195-6701(93)90100-E . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Belkum A., Melles D. C., Nouwen J., van Leeuwen W. B., van Wamel W., Vos M. C., Wertheim H. F., Verbrugh H. A. (2009). Co-evolutionary aspects of human colonisation and infection by Staphylococcus aureus Infect Genet Evol 9 32–47 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.09.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loo I., Huijsdens X., Tiemersma E., de Neeling A., van de Sande-Bruinsma N., Beaujean D., Voss A., Kluytmans J. (2007). Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus of animal origin in humans Emerg Infect Dis 13 1834–1839 10.3201/eid1312.070384 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nguyen K., Zhang T., Thi Vu B. N., Dao T. T., Tran T. K., Thi Nguyen D. N., Thi Tran H. K., Thi Nguyen C. K., Fox A., other authors (2014). Staphylococcus aureus nasopharyngeal carriage in rural and urban northern Vietnam Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 108 783–790 10.1093/trstmh/tru132 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. L., Wang J. T., Sheng W. H., Chen Y. C., Chang S. C. (2010a). Nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia in Taiwan: mortality analyses and the impact of vancomycin, MIC = 2 mg/L, by the broth microdilution method BMC Infect Dis 10 159 10.1186/1471-2334-10-159 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. T., Wang J. L., Fang C. T., Chie W. C., Lai M. S., Lauderdale T. L., Weng C. M., Chang S. C. (2010b). Risk factors for mortality of nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infection: with investigation of the potential role of community-associated MRSA strains J Infect 61 449–457 10.1016/j.jinf.2010.09.029 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Y., Chiueh T. S., Sun J. R., Tsao S. M., Lu J. J. (2012). Molecular typing and phenotype characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from blood in Taiwan PLoS One 7 e30394 10.1371/journal.pone.0030394 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannet W. J., Spalburg E., Heck M. E., Pluister G. N., Willems R. J., De Neeling A. J. (2004). Widespread dissemination in The Netherlands of the epidemic berlin methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone with low-level resistance to oxacillin J Clin Microbiol 42 3077–3082 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3077-3082.2004 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenberg M. W., Bootsma M. C., Troelstra A., Kluytmans J. A., Bonten M. J. (2011). Transmissibility of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ST398) in Dutch hospitals Clin Microbiol Infect 17 316–319 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03260.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim H. F., Melles D. C., Vos M. C., van Leeuwen W., van Belkum A., Verbrugh H. A., Nouwen J. L. (2005a). The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections Lancet Infect Dis 5 751–762 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim H. F., van Leeuwen W. B., Snijders S., Vos M. C., Voss A., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. M., Kluytmans J. A., Verbrugh H. A., van Belkum A. (2005b). Associations between Staphylococcus aureus genotype, infection, and in-hospital mortality: a nested case-control study J Infect Dis 192 1196–1200 10.1086/444427 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte W., Kresken M., Braulke C., Cuny C. (1997). Increasing incidence and widespread dissemination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in hospitals in central Europe, with special reference to German hospitals Clin Microbiol Infect 3 414–422 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00277.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]