Summary

Bacterial populations differentiate at the subspecies level into clonal complexes. Intraclonal genome diversity was studied in 100 isolates of the two dominant P seudomonas aeruginosa clones C and PA14 collected from the inanimate environment, acute and chronic infections. The core genome was highly conserved among clone members with a median pairwise within‐clone single nucleotide sequence diversity of 8 × 10−6 for clone C and 2 × 10−5 for clone PA14. The composition of the accessory genome was, on the other hand, as variable within the clone as between unrelated clones. Each strain carried a large cargo of unique genes. The two dominant worldwide distributed P. aeruginosa clones combine an almost invariant core with the flexible gain and loss of genetic elements that spread by horizontal transfer.

Introduction

Within a bacterial species, the individual strains typically segregate into distinct clonal complexes that share more genetic and phenotypic features among themselves than with clonally unrelated strains (Robinson et al., 2010). Correspondingly, genome diversity is significantly lower within clones than between clones. Here, we report on the intraclonal genome diversity of the two most common clones in the global population of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Wiehlmann et al., 2007; 2015).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous and metabolically versatile Gram‐negative bacterium that thrives in soil and aquatic habitats and colonizes the animate surfaces of plants, animals and humans (Ramos, 2004–2015). The success of P. aeruginosa as a cosmopolitan aquatic bacterium and opportunistic pathogen is based on its broad genetic repertoire. Its pangenome consists of a core of about 4000 genes common to all P. aeruginosa strains, a flexible accessory genome of 10 000 genes and at least a further hundred thousand genes only present in a few clones or strains (Hilker et al., 2015). We have selected 100 isolates of the predominant P. aeruginosa clones C and PA14 from the inanimate environment, acute and chronic infections to study general features of intraclonal genome variation, i.e. the conservation and motility of core and accessory genome and the nature and frequency of sequence variation and mutation.

Results and discussion

The NN2 clone C genome

Clone C is the most abundant clone in the worldwide P. aeruginosa population (Römling et al., 1994; Wiehlmann et al., 2007). Completely sequenced P. aeruginosa genomes are already available for several clones but not clone C. Hence we decided to completely sequence a phenotypically characterized clone C strain. The cystic fibrosis (CF) isolate NN2 was selected as the reference strain for clone C because strain NN2 was the first P. aeruginosa clone C isolate in a P. aeruginosa naive CF subject, and its subsequent genomic microevolution in the CF host for the next 25 years is known (Cramer et al., 2011). Moreover, phenotypic traits of morphotype, motility, virulence, fitness (Cramer et al., 2011), a physical genome map (Schmidt et al., 1996) and the sequence of genomic islands (Larbig et al., 2002; Klockgether et al., 2004) have been investigated before.

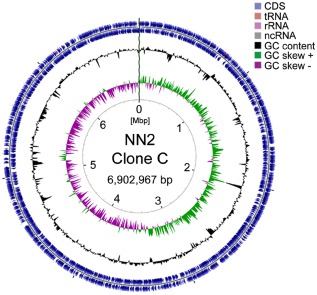

The 6 902 967 bp large NN2 genome (GC‐content 66.12%) encodes 6601 open reading frames (ORFs), 62 transfer RNAs, 13 ribosomal RNAs and 1 transfer‐messenger RNA (Fig. 1; Table S1). Strain NN2 shares 5355 orthologues with reference strain PAO1 and harbours a repertoire of 48 islands in its accessory genome (Klockgether et al., 2011). The majority of the 1246 non‐PAO1 ORFs encode proteins of unknown function indicating that NN2 carries a large yet unexplored set of clone or strain‐specific genes. Reliably annotated non‐PAO1 ORFs code for elements of horizontal gene transfer, maintenance and defence of genomic integrity, enzymes, transcriptional regulators and heavy metal resistance proteins. Instructive examples are multiple copies of DNA repair genes or condensins not yet reported in P. aeruginosa that assist in the correct folding of the chromosome (Badrinarayanan et al., 2012; She et al., 2013). These extra features may confer clone‐specific fitness traits to clone C so that it could become the most abundant clone in both environmental and disease habitats (Wiehlmann et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Clone C NN2 genome atlas.

Genome diversity of clone C and clone PA14 strains

Having complete genome sequences of the reference strains PA14 (Lee et al., 2006) and NN2 at hand (this work, accession no. PREBJ5222 in the EMBL/EBI archive), we next explored the intraclonal diversity of these two major clones in the P. aeruginosa population (Wiehlmann et al., 2007) by genome sequencing of 57 clone C and 42 clone PA14 isolates (see Text S1). The spatiotemporally unrelated strains were isolated during the last 30 years from the aquatic environment, acute infections or chronic airway infections in individuals with CF or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Table S2).

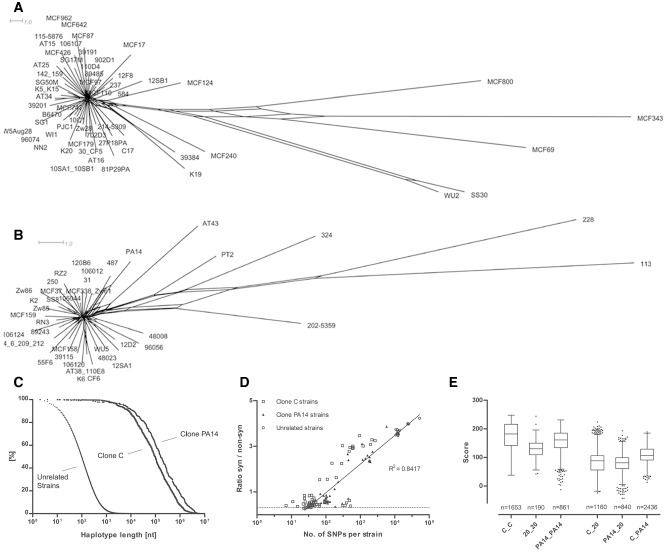

Clonal conservation of the chromosomal frame

We calculated the length of syntenic segments with 100% sequence identity between pairs of either clone C, clone PA14 or clonally unrelated strains (Hilker et al., 2015). The completely sequenced NN2, PA14 and PAO1 genomes were taken as reference. Fig. 2C shows the normalized frequency distribution of the length of fragments with identical sequence. Shared segments with absolute sequence identity, commonly called ‘haplotypes’ in case of diploid genomes, were short with a median size of 100 nucleotides if pairs of unrelated clones were compared (Hilker et al., 2015). In contrast, when either two clone C or two clone PA14 strains were compared, they shared large blocks of identical sequence with a median size of 99 kb (clone C) or 163 kb (clone PA14). Thus, haplotypes are 1000‐fold longer within a clonal complex than between unrelated clones. The chromosomal frame is conserved among members of a clonal complex, and in only a few cases the gene contig was disrupted by larger deletions (Fig. S1, Text S2).

Figure 2.

Intraclonal genome diversity of the clonal complexes C and PA14.

A and B. SNP‐based phylogenetic trees of the clonal complexes C (A) and PA14 (B).

C. Conservation of the core genome. Normalized distribution of the length of 100% pairwise conserved sequence (‘haplotype’) in 58 clone C (n = 33 800 haplotypes), 42 clone PA14 (n = 9510) and 20 clonally unrelated P. aeruginosa strains (n = 3 779 224).

D. Comparison of intraclonal versus. interclonal sequence diversity: Plot of the ratio of synonymous to non‐synonymous SNPs versus the total number of SNPs per strain. Clone C, clone PA14 and clonally unrelated strains (reference: strain PAO1 genome) are differentiated by symbol. The dotted line indicates the expectancy value of random mutation.

E. Diversity of the accessory genome. Box‐plot presentation of the similarity of the accessory genome within and between clonal complexes. For each strain, a global score of relatedness was evaluated, whereby the two strains were assessed of whether they were concordant (assigned value: +1) or discordant (assigned value: −1) for the presence or absence of each RGP or genomic island known from eight completely sequenced P. aeruginosa genomes (PAO1, PA14, PACS2, PA7, LESB58, C3719, 2192). Please note the large overlap of scores of the intraclonal comparisons (C_C; PA14_PA14) with those of interclonal comparisons of 20 unrelated strains (20_20).

Next, the haplotypes were used to visualize the relatedness of strains in a split‐tree (Puigbò et al., 2012) (Fig. 2A and B). Tree topology is similar for the two clones. The majority of strains form a star‐like structure of closely related independent singletons of just one strain. Five (C) and six strains (PA14) are distant outliers. The preponderance of singletons suggests that most isolates of the clonal complex diverged from a common ancestor by few independent events.

Intraclonal diversity of core and accessory genome

The median intraclonal sequence diversity at the single nucleotide (SNP) level was found to be 0.372‰ (range 0.002–0.789 ‰) in clone C and 0.024‰ (range 0.008–0.973 ‰) in clone PA14 strains (Table 1). Most sequence diversity is caused by genomic islands (GI) and a few regions of genome plasticity (RGPs) of the accessory genome (Fig. S2A and B). If we only considered the core genome common to all P. aeruginosa, the median sequence diversity at the SNP level was calculated to be 8 × 10−6 for clone C and 2 × 10−5 for clone PA14 which is more than 100‐fold lower than the sequence diversity among unrelated clones (Hilker et al., 2015). In other words, the core genome is highly conserved in a clonal complex and differs by just a few dozen SNPs from one strain to another.

Table 1.

Features of the investigated P. aeruginosa clone C and clone PA14 strains

| (A) Habitats; (B) SNP statistics of the genome panel | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Habitats | |||

| Chronic infection | Acute infection | Environment | |

| Clone C strains (n) | 36 | 10 | 11 |

| Clone PA14 strains (n) | 26 | 10 | 6 |

| B. SNP statistics of the genome panela | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone | Clone C | Clone C editedb | Clone PA14 | Clone PA14 editedc |

| No. of strains | 57 | 57 | 42 | 42 |

| SNPs | 2568 (15–5447) | 56 (15–2900) | 156 (55–6364) | 141 (55–4275) |

| Intragenic (Intra) | 2353 (7–5051) | 45 (8–2671) | 118 (40–5796) | 105 (40–3807) |

| Intergenic (Inter) | 194 (8–446) | 11 (4–279) | 37 (15–568) | 34 (15–468) |

| Ratio intra/inter | 11.62 (0.88–14.24) | 4.72 (1.14–18.18) | 3.84 (2.04–15.54) | 3.35 (1.13–9.13) |

| Synonymous SNPs (syn) | 1805 (2–3856) | 16 (2–2042) | 47 (13–4605) | 41 (13–3126) |

| Non‐synonymous SNPs (non‐syn) | 548 (5–1195) | 28 (5–629) | 74 (27–1191) | 65 (27–681) |

| Ratio syn/non‐syn | 3.21 (0.4–4.38) | 0.55 (0.28–3.47) | 0.73 (0.36–3.87) | 0.63 (0.36–4.59) |

| Transitions (Ts) | 1620 (11–3426) | 41 (11–1912) | 97 (40–4703) | 87 (40–3305) |

| Transversions (Tv) | 916 (4–2021) | 17 (3–988) | 59 (15–1661) | 55 (15–970) |

| Ratio Ts/Tv | 1.76 (1.55–2.75) | 2.5 (1.43–19.1) | 1.91 (1.27–6.89) | 1.68 (1.25–7.67) |

| Indels | 5 (1–64) | 3 (1–62) | 4 (0–58) | 2 (0–56) |

| Thereof frame‐shifts | 2 (0–44) | 2 (0–44) | 1 (0–34) | 0 (0–33) |

All data are given as median values and range (in brackets).

Single‐nucleotide polymorphisms in PAGI‐2 like genomic islands (PAGI‐2, pKLC102, PAPI‐1, RGP5 insertion) removed.

Single‐nucleotide polymorphisms in PAPI‐1 island removed.

Intraclonal diversity was higher in the accessory genome not only in terms of sequence diversity, but also – and more importantly – in terms of the repertoire of GIs and RGPs of the individual strains. The composition of the accessory genome was nearly as variable among clone C or clone PA14 strains as between unrelated clones (Fig. 2E). Figures S3–S5 visualize the combinatorial composition of the accessory genome.

The highest sequence diversity was observed in the mobile integrative and conjugative elements (ICE) of the types pKLC102, PAGI‐2 and PAPI‐1 which coexist as extra‐chromosomal elements and spread across species and genus barriers by horizontal transfer (Qiu et al., 2006; Klockgether et al., 2007; Pradervand et al., 2014). Consistent with their access to a large pool of proteobacterial hosts, more SNPs were fixed in these mobile ICEs than in any other GI or RGP of the clone C and PA14 genomes. When we removed the SNPs located in these three ICEs from the data set, the SNP statistics of the two clones converged indicating that similar mechanisms of mutation and repair exist in C and PA14 (Table 1).

Intraclonal purifying selection of SNPs

Next, we examined the ratio S/N of synonymous to non‐synonymous substitutions in the coding region of the 100 clone C and PA14 strains. The proportion of synonymous substitutions was higher in all strains than the expected value KA/KS = 9.1/2.9 of random mutation, but two groups could be clearly distinguished (Fig. 2D). In the larger cluster of 70 strains, the overrepresentation of synonymous substitutions was within the upper confidence interval of the expected value, but in all other strains including those with the largest intraclonal sequence diversity, the portion of synonymous SNPs increased even further with the total number of SNPs. The logarithmic regression line also properly described the interclonal S/N ratio. These data give a hint on the evolution of coding genes in P. aeruginosa. When we compare intraclonal sequence diversity against a clonal reference genome, neutral substitutions are more likely to be fixed than amino acid substitutions. This trend of purifying selection against non‐synonymous substitutions increases with the total number of SNPs until an S/N ratio of about four is reached that according to our P. aeruginosa pangenome data (Hilker et al., 2015) is typical for interclonal sequence diversity between unrelated clonal complexes in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 2D).

Figure S6 shows the KA / KS ratios vs. the logarithm of the total number of SNPs in complete and core genomes of the clone C and clone PA14 strain panels. The lower KA/KS values of the complete genomes indirectly visualize the relatively higher proportion of synonymous SNPs in the accessory genomes of the clone C and PA14 strains (Fig. S6). Consistent with this observation, Tajima's D values (Tajima, 1989) of within clone comparisons were less negative in the RGPs and genomic islands of the accessory genome [clone C (median; range): −2.85; 0.18–−3.15; clone PA14: −2.97; 1.42–−3.17] than in the core genome (clone C: −3.08; −2.25–−3.15; clone PA14: −3.02; −2.13–−3.17) (Table S3). Genomic segments with D values around neutrality (D = 0) (Robinson et al., 2010) were exclusively located in the accessory genome (Fig. S7). These data suggest stronger purifying selection in the core genome than in the accessory genome the latter being prone to ongoing horizontal gene transfer across species and genus carriers (Klockgether et al., 2011). The whole genome comparison of the 58 clone C and 43 clone PA14 strains yielded Tajima's D values of −3.09 and −3.07 again demonstrating non‐neutral within clone evolution.

The higher proportion of amino acid substitutions within the clone than between clones also showed up in another frequency spectrum of the type of change (P < 10−6) and the functional category of the affected protein (Table 2, Fig. S8). This finding is plausible in the context of the divergent time scales of the evolution of the P. aeruginosa core genome and its clonal complexes. The few mostly clade‐specific non‐synonymous mutations in a clonal complex primarily affect proteins involved in bacterial communication with its environment which indicates their habitat‐related emergence in a recent ancestor at the time scale of days to decades. Conversely, the retained protein variants of the core genome are the result of purifying selection over millions of years (Doolittle et al., 1996; Ludwig et al., 1998).

Table 2.

Frequency of amino acid exchanges and strain‐specific genes in 26 functional classesa

| Functional category | Genes in the core genome | Genes with amino acid substitution | Genes with non‐conservative amino acid substitution (Dayhoff < 6) | Strain‐specific genes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Clone PA14 | Clone C | Clone PA14 | Clone C | Clone PA14 | Clone C | |

| Adaptation, protection | 92 | 1.90 | 30 | 49 | 4 | 12 | 101 | 127 |

| Amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism | 186 | 3.84 | 165 | 69 | 16 | 10 | 88b | 6 |

| Antibiotic resistance and susceptibility | 9 | 0.18 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 19 | 40 |

| Biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, carriers | 128 | 2.64 | 6 | 37 | 3 | 8 | 14 | 8 |

| Carbon compound catabolism | 111 | 2.29 | 5 | 36 | 6 | 9 | 62 | 275 b |

| Cell division | 22 | 0.45 | 19 | 228 | 4 | 9 | 37 | 13 |

| Cell wall / LPS / capsule | 114 | 2.35 | 75 | 149 | 8 | 21 | 15 | 62b |

| Central intermediary metabolism | 178 | 3.68 | 37 | 29 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 18 b |

| Chaperones | 16 | 0.33 | 6 | 261 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 7 |

| Chemotaxis | 21 | 0.43 | 14 | 16 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| DNA replication, recombination, modification, repair | 76 | 1.57 | 98 | 4632 | 21 | 83 | 88 | 187 b |

| Energy metabolism | 159 | 3.28 | 94 | 114 | 8 | 10 | 41 | 132b |

| Fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism | 47 | 0.97 | 81 | 397 | 7 | 15 | 45b | 0 |

| Hypothetical, unclassified, unknown | 1657 | 34.2 | 812 | 10749 | 158 | 55 | 2177 | 2138 |

| Membrane proteins | 267 | 5.52 | 72 | 327 | 17 | 25 | 11 | 0 |

| Motility and attachment | 44 | 0.91 | 286 | 492 | 15 | 31 | 56 | 47 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | 68 | 1.40 | 6 | 25 | 0 | 3 | 101 | 53 |

| Protein secretion/export apparatus | 53 | 1.09 | 35 | 1149 | 8 | 30 | 4 | 11 |

| Putative enzymes | 367 | 7.59 | 51 | 2455 | 32 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Related to phage, transposon, or plasmid | 6 | 0.12 | 124 | 3332 | 20 | 50 | 450 b | 210 |

| Secreted factors (toxins, enzymes, alginate) | 40 | 0.82 | 80 | 17 | 2 | 4 | 46b | 0 |

| Transcription, RNA processing and degradation | 49 | 1.01 | 49 | 28 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Transcriptional regulators | 398 | 8.23 | 37 | 617 | 12 | 18 | 170 | 95 |

| Translation, post‐translational modification, degradation | 143 | 2.95 | 96 | 1086 | 11 | 28 | 58 | 50 |

| Transport of small molecules | 527 | 10.8 | 64 | 623 | 42 | 20 | 149 | 201 |

| Two‐component regulatory systems | 57 | 1.17 | 387 | 68 | 12 | 11 | 18 | 11 |

Classes were defined by the P. aeruginosa Community Annotation Project (PseudoCAP).

Significantly different (P corr < 0.05) between clone C and clone PA14. All P‐values were corrected for multiple testing by the Bonferroni algorithm.

The functional category is significantly (Pcorr < 0.05) more frequent (bold) or less frequent (underlined) in the clone than in the pangenome.

Intraclonal hot spots of mutation

Next, we searched for hot spots of mutations in the core genome of the 100 strains (Tables S4 and S5). Besides numerous phage and plasmid‐derived proteins found in both clones, the heavy metal ion efflux protein CusA, the cyclic‐di‐GMP phosphodiesterase BifA (Kuchma et al., 2007) and the key regulator of quorum sensing LasR (Williams and Cámara, 2009) were identified in clone C as the targets for numerous non‐conservative amino acid substitutions some of which should modify structure and/or function. For example, in the case of LasR the amino acid exchanges include the helix‐breaking incorporation of a proline which either affects conserved positions in the alpha helices 8 and 10 or are located in the binding pocket of the homoserine lactone autoinducer (Bottomley et al., 2007).

As a complementary approach, the genomes were scanned for segments with significantly elevated SNP rates (FDR < 0.05). The clone C strain panel carried 12 hot spots of mutations, 10 of which affecting intergenic regions or phage and plasmid‐related genes (Table S5). The two genes in the core genome were the transcriptional regulator PA2020 and again lasR. Of the 60 segments found in the PA14 strains, 44 were located in the core and 16 in the accessory genome. Hot spots of mutations were predominantly phage or plasmid‐related genes and functionally to date uncharacterized ORFs. Strain PT2 had accumulated almost all SNPs found in the 22 genes flanking RGP31, suggesting that the SNPs had been acquired from another clone by recombination. In contrast to this singular case, numerous strains of the PA14 clone harboured SNPs in the three hot spots of mutation of functionally characterized genes, i.e. pchF, rocS2 and pelA indicating diversifying selection. Their gene products are involved in the communication of P. aeruginosa with its environment. PchF contributes to the non‐ribosomal biosynthesis of the siderophore pyochelin (Patel and Walsh, 2001), the transcriptional sensor RocS2 controls the biogenesis of CupC fimbriae and multi‐drug transport (Sivaneson et al., 2011) and PelA deacetylates the Pel exopolysaccharide which is essential for biofilm formation (Colvin et al., 2013).

Strain‐specific gene repertoire

The strain‐specific acquisition of genes could generate gain‐of‐function traits that modulate the fitness, lifestyle and metabolic competence of the clonal complex. And indeed, the provision of extra genes to the individual strain was found to be substantial in both the clone C and the clone PA14 complex (Table S6). An average PA14 or C strain had taken up 170 and 103 genes respectively (P < 0.001 for the comparison PA14 versus C). The majority of closest orthologues was identified in other P. aeruginosa clones or other members of the Pseudomonas genus (Fig. S9). Phylogenetically more distant taxa contributed to the residual 20%.

Table 2 summarizes the total repertoire of strain‐specific genes in the two clonal complexes sorted by functional category. Genes related to mobile genetic elements like phage or plasmids and hypotheticals of yet unknown function were significantly overrepresented among the strain‐specific genes. This finding was expected because phages, transposons and plasmids are the common vehicles to provide genes to an individual strain of a clonal complex by horizontal gene transfer. Conversely, genes that encode elements of transcription or of intermediary metabolism were rarely or not identified among the strain‐specific genes indicating that the genetic repertoire of the core genome is essential and comprehensive to cope with the basic requisites of cell growth and metabolism of P. aeruginosa (Table 2). However, we noted a differential repertoire of genes promoting the competence of the bacteria to metabolize substrates. The clone PA14 strains harboured a larger number of genes involved in amino acid or fatty acid metabolism, whereas the clone C strains had a larger genetic repertoire for carbohydrate metabolism (Table 2). It is textbook knowledge based on studies on a few reference strains like PAO1 that P. aeruginosa prefers amino acids and fatty acids as carbon source of intermediary and energy metabolism (‘catabolite repression control’) (Linares et al., 2010). Our data indicate that the repression of the uptake and catabolism of sugars may not apply to all P. aeruginosa and that some clonal lineages like the most common clone C may compensate the core genome‐predetermined limitations in the utilization of sugars by the horizontal acquisition of genes of carbohydrate metabolism or by mutation of key regulators the latter having been reported for P. aeruginosa residing in CF lungs (Silo‐Suh et al., 2005).

Conclusion

This first extensive study of intraclonal genome diversity of a cosmopolitan bacterium revealed a highly conserved core genome and a highly versatile accessory genome of its most common clonal complexes. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an ubiquitous microorganism that is equipped with broad nutritional capabilities, stress tolerance and an arsenal of virulence effectors (Ramos, 2004–2015). Members of the dominant clones C and PA14 have been isolated worldwide from soil and aquatic habitats and the animate surfaces of plants, animals and humans (Wiehlmann et al., 2007; Cramer et al., 2012).

For our study, we selected isolates from the environment and from acute and chronic human infections. Lateral gene transfer turned out to be the driving force of intraclonal differentiation. On the contrary, the core genome with its sequence diversity of about 10−6 was virtually identical among members of the clone C or clone PA14 communities irrespective of their spatiotemporal origin. The few SNPs in the core genome were mostly strain specific and the de novo coding variants were subject to purifying selection. In conclusion, the two dominant worldwide distributed P. aeruginosa clones are probably so successful at colonizing all aquatic habitats and mucosal surfaces on earth because their genome combines an almost invariant core with the flexible gain and loss of genetic elements that spread by horizontal transfer.

Contributions

S.F. and B.T. conceived the study. S.F., N.C., J.K., S.D., M.D., S.M., S.W. and L.W. performed experiments. S.F., P.M.L., P.C. and B.T. devised algorithms. S.F., P.M.L., P.C., C.F.D., A.G., R.H., T.S., O.T. and J.K. wrote scripts. S.F., N.C., P.M.L., P.C., S.D., C.F.D., R.H., P.C., J.K. and B.T. processed and evaluated the primary data. The manuscript was prepared by S.F. and B.T. with contributions by N.C., P.M.L., P.C., L.W. and J.K.. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supporting information

Text S1. Experimental procedures.

Text S2. The text describes the insertions, deletions and frameshifts on clone C and PA14 genomes.

Fig. S1. Deletions in the core genome found in clone C (inner circle) and clone PA14 isolates (outer circle) from different habitats (full circle = chronic infection, open circle = acute infection, square = environment).

Fig. S2. Cumulative Kaplan–Meier‐plots of the SNP frequency along the genomes of clone PA14 isolates (a) (n = 40 and separately the two outliers PT2 and 158) and of clone C isolates (b) (n = 57). Regions with pronounced sequence diversity are indicated by RGP or ORF numbers. Single‐nucleotide polymorphisms in RGPs marked with an asterisk were not incorporated because of their large number of SNPs.

Fig. S3. Diversity of genomic islands in clone PA14 (a) and clone C (b) isolates. The sequences of the individual strains were aligned to the sequence of the indicated genomic island. The colour gradient of the heat maps ranges from the absence of all genes of the island (mere green) via the presence of an increasing number of matching homologues to 100% sequence identity (mere red). Strains are arranged by the similarity of their repertoire applying hierarchical clustering with default parameters (R package).

Fig. S4. Diversity of RGPs of the accessory genome of clone C strains. regions of genome plasticity sequences were extracted from eight completely sequenced P. aeruginosa genomes (PAO1, PA14, PACS2, PA7, LESB58, C3719, 2192). The sequences of the individual strains were aligned to the sequence of the indicated RGP. The colour gradient of the heat map ranges from the absence of all genes of the RGP (mere green) via the presence of an increasing number of matching homologues to 100% sequence identity (mere red). Strains are arranged by the similarity of their repertoire applying hierarchical clustering with default parameters (r package).

Fig. S5. Diversity of RGPs of the accessory genome of clone PA14 strains. Regions of genomic plasticity sequences were extracted from eight completely sequenced P. aeruginosa genomes (PAO1, NN2, PACS2, PA7, LESB58, C3719, 2192). The sequences of the individual strains were aligned to the sequence of the indicated RGP. The colour gradient of the heat map ranges from the absence of all genes of the RGP (mere green) via the presence of an increasing number of matching homologues to 100% sequence identity (mere red). Strains are arranged by the similarity of their repertoire applying hierarchical clustering with default parameters (r package).

Fig. S6. Dependence of KA/KS on the logarithm of SNPs in complete (left panel; A,C) and core genomes (right panel; B, D) of 57 clone C (upper panel; A,B) and 42 clone PA14 strains (lower panel; C,D) taking strains NN2 and PA14 as reference.

Fig. S7. Gradient of Tajima's D along the clone C (left) and clone PA14 (right) genomes. Tajima's D values were calculated for the whole data sets of 58 clone C and 43 clone PA14 genomes in 1000 bp sliding windows.

Fig. S8. Normalized frequency of amino acid replacements within and between clonal complexes sorted by occupancy of Dayhoff similarity index.

Fig. S9. Origin of closest homologues of strain‐specific genes.

Fig. S10. Indel frequency in the strain panel. Frequency of small indels in the clone C (left) and clone PA14 (right) strain panels differentiated by habitat and their localization within intergenic region, genes of annotation classes 1 or 2 and 3 or 4 respectively.

Table S1. Annotation of the NN2 genome. The table lists the annotated ORFs of the NN2 genome.

Table S2. Origin of the investigated strains and detailed SNP statistics. The table lists the origin and isolation date of each strain and provides a detailed SNP statistics compared with the clonal reference (clone C: strain NN2, clone PA14: strain PA14).

Table S3. Within clone Tajima's D values of 1000 bp sliding windows of 58 clone C and 43 clone PA14 genomes. Genome coordinates were taken from the completely sequenced genomes of strains NN2 and PA14. D values were calculated with the ‘angsd’ program (Korneliussen et al., 2014).

Table S4. Amino acid exchanges of the strains. The table shows all amino acid exchanges found in the clone C and clone PA14 strain panel.

Table S5. Hot spots of mutation in the genomes. The table shows all genes with a high mutation frequency within the strain panels and their affiliation to core or accessory genome.

Table S6. Singular or shared genes that are absent in the reference genome and known RGPs. The table shows the additional genes of the strains. Each row lists (from left to right) the annotation and origin of the closest homologue, the strains harbouring the gene and up to 10 more distant homologues, if applicable.

Table S7. Large deletions in the strain panel. The table shows the size and map positions of deletions in clone C and clone PA14 genomes including information about the deleted genes.

Table S8. Indels in the strain panel. The table shows for each strain the detected indels. Shared or strain specific indels are coloured.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank M. Griese (München), T.F. Murphy (Buffalo), J. Sikorski (Braunschweig) and C. Winstanley (Liverpool) for the provision of strains. This work was supported by grants from the Christiane Herzog Stiftung to N.C., the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 900, project A2) to B.T. and to S.S. and B.T. (SFB900, project Z1) and from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (programme ‘Medical Infection Genomics’, 0315827A) to A.G. and B.T. P.M.L. is a member of the graduate programme ‘Infection biology’ of Hannover Medical School.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Originality–Significance Statement

This work describes for the first time the intraclonal genome diversity of the two major Pseudomonas aeruginosa clones C and PA14.

References

- Badrinarayanan, A. , Lesterlin, C. , Reyes‐Lamothe, R. , and Sherratt, D. (2012) The Escherichia coli SMC complex, MukBEF, shapes nucleoid organization independently of DNA replication. J Bacteriol 194: 4669–4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottomley, M.J. , Muraglia, E. , Bazzo, R. , and Carfì, A. (2007) Molecular insights into quorum sensing in the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the structure of the virulence regulator LasR bound to its autoinducer. J Biol Chem 282: 13592–13600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin, K.M. , Alnabelseya, N. , Baker, P. , Whitney, J.C. , Howell, P.L. , and Parsek, M.R. (2013) PelA deacetylase activity is required for Pel polysaccharide synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Bacteriol 195: 2329–2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, N. , Klockgether, J. , Wrasman, K. , Schmidt, M. , Davenport, C.F. , and Tümmler, B. (2011) Microevolution of the major common Pseudomonas aeruginosa clones C and PA14 in cystic fibrosis lungs. Environ Microbiol 13: 1690–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, N. , Wiehlmann, L. , Ciofu, O. , Tamm, S. , Høiby, N. , and Tümmler, B. (2012) Molecular epidemiology of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infections in cystic fibrosis. PLoS ONE 7: e50731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, R.F. , Feng, D.F. , Tsang, S. , Cho, G. , and Little, E. (1996) Determining divergence times of the major kingdoms of living organisms with a protein clock. Science 271: 470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilker, R. , Munder, A. , Klockgether, J. , Losada, P.M. , Chouvarine, P. , Cramer, N. , et al (2015) Interclonal gradient of virulence in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa pangenome from disease and environment. Environ Microbiol 17: 29–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockgether, J. , Reva, O. , Larbig, K. , and Tümmler, B. (2004) Sequence analysis of the mobile genome island pKLC102 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa C. J Bacteriol 186: 518–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockgether, J. , Würdemann, D. , Reva, O. , Wiehlmann, L. , and Tümmler, B. (2007) Diversity of the abundant pKLC102/PAGI‐2 family of genomic islands in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J Bacteriol 189: 2443–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockgether, J. , Cramer, N. , Wiehlmann, L. , Davenport, C.F. , and Tümmler, B. (2011) Pseudomonas aeruginosa genomic structure and diversity. Front Microbiol 2: 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korneliussen, T.S. , Albrechtsen, A. , and Nielsen, R. (2014) ANGSD: Analysis of Next Generation Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinformatics 15: 356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchma, S.L. , Brothers, K.M. , Merritt, J.H. , Liberati, N.T. , Ausubel, F.M. , and O'Toole, G.A. (2007) BifA, a cyclic‐Di‐GMP phosphodiesterase, inversely regulates biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J Bacteriol 189: 8165–8178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larbig, K.D. , Christmann, A. , Johann, A. , Klockgether, J. , Hartsch, T. , Merkl, R. , et al (2002) Gene islands integrated into tRNA(Gly) genes confer genome diversity on a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone. J Bacteriol 184: 6665–6680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.G. , Urbach, J.M. , Wu, G. , Liberati, N.T. , Feinbaum, R.L. , Miyata, S. , et al (2006) Genomic analysis reveals that Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence is combinatorial. Genome Biol 7: R90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares, J.F. , Moreno, R. , Fajardo, A. , Martínez‐Solano, L. , Escalante, R. , Rojo, F. , and Martínez, J.L. (2010) The global regulator Crc modulates metabolism, susceptibility to antibiotics and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Environ Microbiol 12: 3196–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, W. , Strunk, O. , Klugbauer, S. , Klugbauer, N. , Weizenegger, M. , Neumaier, J. , et al (1998) Bacterial phylogeny based on comparative sequence analysis. Electrophoresis 19: 554–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, H.M. , and Walsh, C.T. (2001) In vitro reconstitution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa nonribosomal peptide synthesis of pyochelin: characterization of backbone tailoring thiazoline reductase and N‐methyltransferase activities. Biochemistry 40: 9023–9031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradervand, N. , Sulser, S. , Delavat, F. , Miyazaki, R. , Lamas, I. , and van der Meer, J.R. (2014) An operon of three transcriptional regulators controls horizontal gene transfer of the integrative and conjugative element ICEclc in Pseudomonas knackmussii B13. PLoS Genet 10: e1004441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigbò, P. , Wolf, Y.I. , and Koonin, E.V. (2012) Genome‐wide comparative analysis of phylogenetic trees: the prokaryotic forest of life. Methods Mol Biol 856: 53–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X. , Gurkar, A.U. , and Lory, S. (2006) Interstrain transfer of the large pathogenicity island (PAPI‐1) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 19830–19835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos J.L. (ed.) (2004–2015) Pseudomonas, Vol. 1–7 Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D.A., Falush D., and Feil E.J. (eds) (2010) Bacterial Populations Genetics in Infectious Disease. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Römling, U. , Wingender, J. , Müller, H. , and Tümmler, B. (1994) A major Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone common to patients and aquatic habitats. Appl Environ Microbiol 60: 1734–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K.D. , Tümmler, B. , and Römling, U. (1996) Comparative genome mapping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO with P. aeruginosa C, which belongs to a major clone in cystic fibrosis patients and aquatic habitats. J Bacteriol 178: 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She, W. , Mordukhova, E. , Zhao, H. , Petrushenko, Z.M. , and Rybenkov, V.V. (2013) Mutational analysis of MukE reveals its role in focal subcellular localization of MukBEF. Mol Microbiol 87: 539–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silo‐Suh, L. , Suh, S.J. , Phibbs, P.V. , and Ohman, D.E. (2005) Adaptations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the cystic fibrosis lung environment can include deregulation of zwf, encoding glucose‐6‐phosphate dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol 187: 7561–7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaneson, M. , Mikkelsen, H. , Ventre, I. , Bordi, C. , and Filloux, A. (2011) Two‐component regulatory systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: an intricate network mediating fimbrial and efflux pump gene expression. Mol Microbiol 79: 1353–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, F. (1989) Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123: 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiehlmann, L. , Wagner, G. , Cramer, N. , Siebert, B. , Gudowius, P. , Morales, G. , et al (2007) Population structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 8101–8106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiehlmann, L. , Cramer, N. , and Tümmler, B. (2015) Habitat‐associated skew of clone abundance in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa population. Environ Microbiol Rep 7: 955–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P. , and Cámara, M. (2009) Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr Opin Microbiol 12: 182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Text S1. Experimental procedures.

Text S2. The text describes the insertions, deletions and frameshifts on clone C and PA14 genomes.

Fig. S1. Deletions in the core genome found in clone C (inner circle) and clone PA14 isolates (outer circle) from different habitats (full circle = chronic infection, open circle = acute infection, square = environment).

Fig. S2. Cumulative Kaplan–Meier‐plots of the SNP frequency along the genomes of clone PA14 isolates (a) (n = 40 and separately the two outliers PT2 and 158) and of clone C isolates (b) (n = 57). Regions with pronounced sequence diversity are indicated by RGP or ORF numbers. Single‐nucleotide polymorphisms in RGPs marked with an asterisk were not incorporated because of their large number of SNPs.

Fig. S3. Diversity of genomic islands in clone PA14 (a) and clone C (b) isolates. The sequences of the individual strains were aligned to the sequence of the indicated genomic island. The colour gradient of the heat maps ranges from the absence of all genes of the island (mere green) via the presence of an increasing number of matching homologues to 100% sequence identity (mere red). Strains are arranged by the similarity of their repertoire applying hierarchical clustering with default parameters (R package).

Fig. S4. Diversity of RGPs of the accessory genome of clone C strains. regions of genome plasticity sequences were extracted from eight completely sequenced P. aeruginosa genomes (PAO1, PA14, PACS2, PA7, LESB58, C3719, 2192). The sequences of the individual strains were aligned to the sequence of the indicated RGP. The colour gradient of the heat map ranges from the absence of all genes of the RGP (mere green) via the presence of an increasing number of matching homologues to 100% sequence identity (mere red). Strains are arranged by the similarity of their repertoire applying hierarchical clustering with default parameters (r package).

Fig. S5. Diversity of RGPs of the accessory genome of clone PA14 strains. Regions of genomic plasticity sequences were extracted from eight completely sequenced P. aeruginosa genomes (PAO1, NN2, PACS2, PA7, LESB58, C3719, 2192). The sequences of the individual strains were aligned to the sequence of the indicated RGP. The colour gradient of the heat map ranges from the absence of all genes of the RGP (mere green) via the presence of an increasing number of matching homologues to 100% sequence identity (mere red). Strains are arranged by the similarity of their repertoire applying hierarchical clustering with default parameters (r package).

Fig. S6. Dependence of KA/KS on the logarithm of SNPs in complete (left panel; A,C) and core genomes (right panel; B, D) of 57 clone C (upper panel; A,B) and 42 clone PA14 strains (lower panel; C,D) taking strains NN2 and PA14 as reference.

Fig. S7. Gradient of Tajima's D along the clone C (left) and clone PA14 (right) genomes. Tajima's D values were calculated for the whole data sets of 58 clone C and 43 clone PA14 genomes in 1000 bp sliding windows.

Fig. S8. Normalized frequency of amino acid replacements within and between clonal complexes sorted by occupancy of Dayhoff similarity index.

Fig. S9. Origin of closest homologues of strain‐specific genes.

Fig. S10. Indel frequency in the strain panel. Frequency of small indels in the clone C (left) and clone PA14 (right) strain panels differentiated by habitat and their localization within intergenic region, genes of annotation classes 1 or 2 and 3 or 4 respectively.

Table S1. Annotation of the NN2 genome. The table lists the annotated ORFs of the NN2 genome.

Table S2. Origin of the investigated strains and detailed SNP statistics. The table lists the origin and isolation date of each strain and provides a detailed SNP statistics compared with the clonal reference (clone C: strain NN2, clone PA14: strain PA14).

Table S3. Within clone Tajima's D values of 1000 bp sliding windows of 58 clone C and 43 clone PA14 genomes. Genome coordinates were taken from the completely sequenced genomes of strains NN2 and PA14. D values were calculated with the ‘angsd’ program (Korneliussen et al., 2014).

Table S4. Amino acid exchanges of the strains. The table shows all amino acid exchanges found in the clone C and clone PA14 strain panel.

Table S5. Hot spots of mutation in the genomes. The table shows all genes with a high mutation frequency within the strain panels and their affiliation to core or accessory genome.

Table S6. Singular or shared genes that are absent in the reference genome and known RGPs. The table shows the additional genes of the strains. Each row lists (from left to right) the annotation and origin of the closest homologue, the strains harbouring the gene and up to 10 more distant homologues, if applicable.

Table S7. Large deletions in the strain panel. The table shows the size and map positions of deletions in clone C and clone PA14 genomes including information about the deleted genes.

Table S8. Indels in the strain panel. The table shows for each strain the detected indels. Shared or strain specific indels are coloured.