Abstract

Black women with cumulative violence exposures (CVE) may have unique needs for health care and safety. Qualitative data was analyzed from interviews with nine Black women with CVE to explore factors that motivated women to leave abusive relationships, women’s sources of strengths, and their responses to abuse. Quantitative data (N = 163) was analyzed to examine relationships between CVEs by intimate partner and health among Black women to further characterize the challenges these women face in making changes and finding their sources of strengths. Findings highlight the need to assess for CVE and identify multiple motivators for change, sources of strengths and coping strategies that could be potential points of intervention for women with CVE.

Keywords: Cumulative victimization, intimate partner abuse, Black women, sources of strength

Introduction

Women of African descent are disproportionately affected by intimate partner abuse (IPA) (Catalano, Smith, Snyder & Rand, 2009; Hien & Ruglass, 2009) such as physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. According to results from a national survey of women living in the United States, 43.7% of non-Hispanic Black women reported experiencing violent victimization from an intimate partner. These rates are substantially higher than those of non-Hispanic White (34.7%) and Hispanic (37.1%) women (Black et al., 2011). Similar high rates of IPA are found among Black women in low- and middle-income Caribbean nations. For example, in one study on interpersonal violence in the Caribbean, two thirds of Black women in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) who reported victimization were victims of IPA (Le Franc Samms-Vaughan, Hambleton, Fox, & Brown, 2008). Black women from disadvantaged groups experience multiple forms of violence that accumulate over their lifetime (Long & Ullman, 2013). Women with cumulative violence experiences (CVE) may have unique needs for health, safety, and well-being. Furthermore, the time at which a woman leaves a violence relationship is when she is the most at risk for IPA homicide (Campbell, Rose, Kub, & Nedd, 2003). Given the multiplicative effects of cumulative violence, it is important to understand the survival responses by Black women who experienced abuse to address its impact on Black women’s mental health and help-seeking behaviors and barriers. Thus, an understanding of women’s motivations for change, patterns of response to violence, and sources of strength can be useful for the development of intervention strategies for Black women in the United States and Caribbean nations who are survivors of CVE.

Literature review

Cumulative violence refers to exposure to multiple forms of violence such as physical, sexual, and psychological abuse from intimate and nonintimate perpetrators. Black women with CVE are a high-risk group for negative outcomes of violence and need resources to cope with and address abuse in their lives. Evidence shows that womenwith CVEs are at higher risk for severe mental health symptoms than women who are exposed to a single type of violence or no violence at all (Sundermann, Chu, & DePrince, 2013). Although there is a dearth of research exploring Black women’s CVEs and its associations with interpersonal responses (i.e., reasons for change) and its impact on health outcomes, other research has noted the importance of turning points and sources of strength in enhancing one’s motivation to change and responses to abuse (Burke, Mahoney, Gielen, McDonnell, & O’Campo, 2009). Thus, identifying turning points and sources of strength that are protective against violence or negative outcomes of violence may help inform interventions for this group of Black women who are ethnically diverse.

Women’s responses to violence and sources of strength

Existing literature highlights the role of individual responses in effectively reducing the incidence and impact of victimization. For instance, according to the disruption and reintegration framework (Richardson, 2002), life disruptions (e.g., victimization experiences) change people’s intactworld paradigm and result in negative consequences. However, some people can mitigate negative consequences because they possess or develop qualities to manage stresses associated with these life disruptions. In this case, “resilient reintegration” occurs, referring to “the coping process that results in growth, knowledge, self-understanding and increased strength of resilient qualities” (Richardson, 2002, p. 310). For women who are abused, resilient reintegration often depends upon their self-care agency as described in the theory of self-care (Orem, 1995). Self-care agency refers to capabilities or abilities of women to take care of themselves or their health (Campbell &Weber, 2000). It is affected by developmental age, life experiences, and available resources (Campbell & Soeken, 1999; Campbell & Weber, 2000; Orem, 1995).

Internal and external resources affect women’s ability to manage abusive relationships. Internal resources for women who are abused include factors such as self-efficacy and engaging in self-care. External resources include community response, offers of protection, access to support, and varied resource options (McLeod, Hays, & Chang, 2010) and effective police intervention (Krugman et al., 2004). In a qualitative study (Davis, 2002), women reported utilizing internal resources (e.g., strength, spirituality and hope) to survive abusive experiences and develop ways to protect themselves from violence in future relationships. Strategies such as developing safety nets by saving money, furthering education to obtain more secure employment, and planning escape tactics contributed to the development of women’s strengths (Davis, 2002).

Turning points: factors contributing to women’s motivation to change

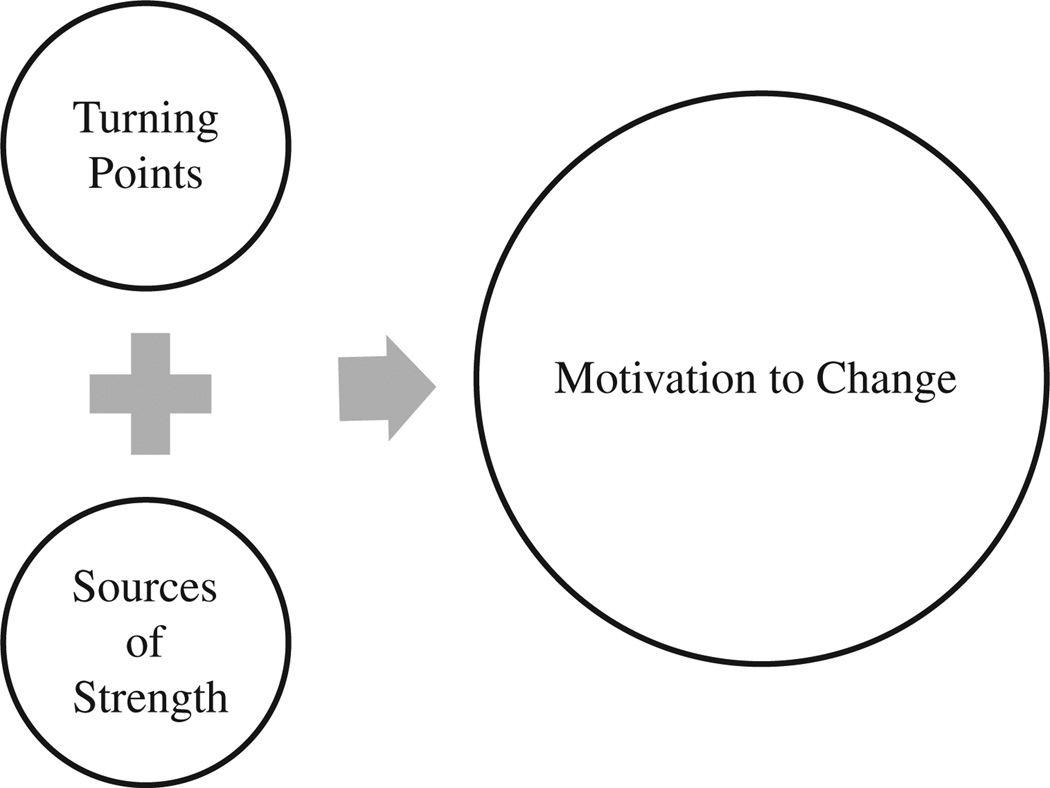

Several factors in women’s abusive relationships serve as catalysts or turning points that contribute to the motivation of women who are abused to change their situations and/or increase their safety (Figure 1). Turning points have been defined as “specific incidents, factors, or circumstances that permanently change how women view the violence, their relationship, and how they wish to respond” (Chang et al., 2010, p. 252). Turning points can be (1) specific events that serve as catalysts for change; (2) “the straw that broke the camel’s back,” which are minor events that tip the scale in a process that has escalated over time; (3) time-related factors that refers to realization that the remaining time for changing an abusive partner is becoming more and more limited; (4) excuses, through which a woman can place the responsibility of breaking up on someone else who insists that breaking up is necessary; and (5) either/or alternatives, in which a woman perceives that she has to make a choice between two alternatives, and that the nonchosen will be lost (Ebaugh, 1988; Enander & Holmberg, 2008). Research shows that women who are abused experience turning points due to fear that the violence affects other individuals, escalation in severity of abuse, recognition that they had support from others (Chang et al., 2010), an abuser’s infidelity (Campbell et al., 1998),; when women start to fear that the abuse is a matter of life and death, and lastly, a cognitive shift in which a woman starts to view the relationship as abusive (Enander & Holmberg, 2008; Haj-Yahia & Eldar-Avidan, 2001). Thus, many turning points affect the motivation of women who are abused to change their abusive situations.

Figure 1.

Model of how turning points and sources of strength combined to motivate women to change their abusive situation.

Purpose of the study

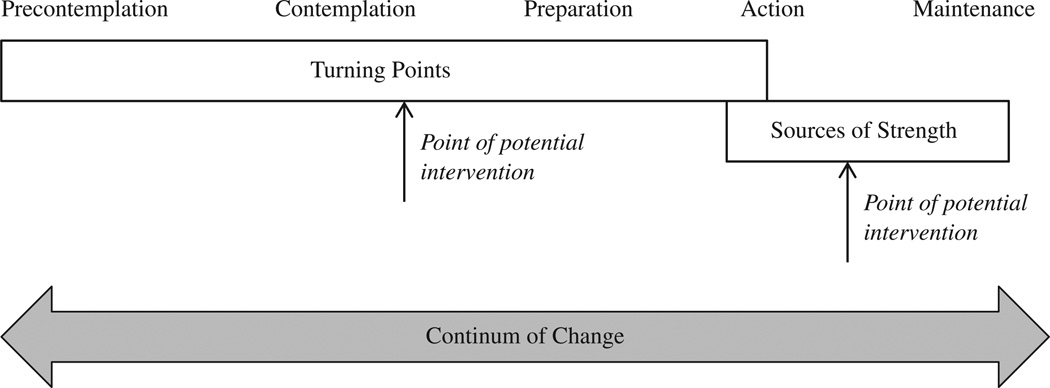

This study focused on ethnically diverse Black women with CVEs. It was guided by the strengths perspective (Saleeby, 1996) and the transtheoretical model, which outlines behavior transformation as a process on a continuum of change (Figure 2). Beginning with precontemplation to change, an individual uniquely progresses through the continuum of change, with contemplation to change, preparation for change, behavior change, and maintenance (Burke, Denison, Gielen, McDonnell, & O’Campo, 2004; Prochaska &DiClemente, 1983). The purpose was to understand factors and circumstances (i.e., turning points) that motivated women to change their abusive situations, their coping strategies, and sources of strengths. Further, to understand challenges associated with making positive life changes among Black women with CVEs, the study examined their health behaviors and perceived overall health.

Figure 2.

Conceptualization of motivating factors to leave an abusive relationship among women survivors of intimate partner abuse (IPA), by applying the transtheoretical model.

Method

Parent study

The current study is part of a large multisite comparative case-control study conducted from 2009 to 2011. The parent study consisted of quantitative surveys (N = 543) and in-depth interviews (N = 20) of abused Black women. The primary aims of the parent study were to (1) determine the prevalence of physical, emotional, and sexual intimate partner violence among health care–seeking African Caribbean women living in the USVI and a comparable group of African American women in the U.S. mainland and (2) compare physical and mental health conditions, and use of health care services among African Caribbean women who are abused in the USVI with women who are not abused and with U.S. African American women.

The sample and procedures of the parent study are described in depth elsewhere (Sabri, Bolyard et al., 2013). Briefly, participants were women who self-reported lifetime abuse and past 2-year experiences of intimate partner physical and sexual abuse, with or without psychological abuse. Participants were recruited from primary care, prenatal or family planning clinics in Baltimore, Maryland, and in St. Croix and St. Thomas, USVI, from immunization, maternal health, and family planning clinics. Approval for the study was granted from the institutional review boards of Johns Hopkins University and the University of Virgin Islands.

Current study

In the current study, we used a life history approach to understand how sources of strength and access to resources are formulated within the context of Black women’s social reality. Using qualitative interview data, we compared two subpopulations of Black women (i.e., United States and USVI) who are survivors of lifetime cumulative violence (i.e., intimate partner and nonintimate partner perpetrated violence) to (1) describe various factors and circumstances (i.e., turning points) that contributed to their motivation to change abusive situations and (2) identify their responses to abuse and sources of strength. To further understand the challenges associated with making life changes, we examined self-reported health behaviors and perceived overall health among women survivors of cumulative violence.

Sample

For the qualitative portion of the current study, we analyzed a subset of nine women (five from United States and four from USVI), who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) participants described abuse experiences that occurred during childhood and adulthood, (2) participants reported cumulative victimization by intimate partners in the quantitative survey, (3) events reported by participants were categorized as severe according to validated scales (e.g., Danger Assessment; Campbell, Webster, & Glass, 2009), and (4) participants reported having a mental health morbidity, such as depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with clinically significant symptoms. In the qualitative sample, women’s ages ranged from 21 to 52. More than one half (i.e., 55.5%) completed some college or were college graduate and 55.6% of them were unemployed.

For the quantitative portion of the present study, we selected 163 women with experiences of cumulative violence (i.e., physical, psychological, and sexual) by male intimate partner perpetrators. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 55, with 75.4% participants in the age group of 18 to 34. The average age of women who reported CVE in intimate partner relationships (n = 163; 49 in Baltimore and 114 in the USVI) was 29.7. More than one third of the women with CVE in Baltimore and USVI (35.4%–44.9%) had at least a high school education and nearly 55% were employed.

Qualitative data and analysis

The interview guide included questions about major life events, childhood experiences, relationships including sexual partners, abuse disclosure to health care providers, and sexual health. We conducted interviews using a life history approach (Haglund, 2004; Yoshihama & Bybee, 2011) associating incidents of severe abuse with relationship and life experiences. We used a calendar or grid with these major themes incorporated to provide a visual representation of the participants’ life as she shared it. We then discussed severe abuse events in-depth to probe for triggers and strengths the participants relayed as their stories unfolded.

Qualitative analysis

Data were analyzed combining thematic analysis procedure and analysis of life history calendars. The two methodological approaches were used to deepen our explorations of cumulative abuse experiences among the participants (Baxter & Jack, 2008). During analysis, we aimed to provide rich descriptions of these experiences while attending to the diverse contexts in which they occurred and thus examined nine cases to find answers to our research questions (Yin, 2003). We approached analyses of transcript texts using a three-step process. All authors read each transcript three times; coding and categorization according to thematic patterns was an iterative process. During each step of the process, we integrated constant comparison techniques to our data analysis within and across case stories (Glaser, 1965). During the first reading, to enhance credibility, each of the authors independently coded the cases, focusing on major events and overt references to turning points for change described by the participants. During the second reading, we identified explicit sources of strength as discussed by each participant. During the third reading, we synthesized coding to develop themes that emerged across participants stories. After each step of the process, all authors met to discuss findings and refine analysis criteria (Glaser, 1965) and an audit trail was kept to document our decisions.

Quantitative data and analysis

Measures

To assess CVEs in intimate partner relationships, a dichotomous variable was created using items from the Severity of Violence Against Women Scale (SVAWS; 46 items; α = .94; Marshall, 1992) for physical and sexual abuse and the Women’s Experiences of Battering (WEB; 10 items, α = 1.00; range = 0–71; Smith, Earp, & DeVellis, 1995) for psychological abuse. In SVAWS, women were asked how often in the past 12 months they experienced the behavior from their abusive partners, if they ever had an abusive partner, and about their current or most recent partner. The items were rated using a 4 point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (not in the last 12 months but it did happen before). The WEB captured psychological abuse using the following six domains: perceived threat, altered identity, managing, entrapment, yearning, and disempowerment (Smith et al., 1995). Each item was rated using a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). A categorical variable was created to classify women into two categories: those with all three types of victimization (physical, sexual, and emotional), and those with a single or two types of victimizations. Women who endorsed all three types of victimization by their intimate partners were classified as those with CVE in intimate partner relationships and assigned the value of 1 (cumulative victimization = 1, one or two types = 0).

PTSD was measured using the Primary Care Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Screening (PC-PTSD; Prins et al., 2003). The PC-PTSD (4 items; α = .78) is a self-report screening tool designed to assess PTSD symptoms in the past month, with scores ranging from 0 to 4. A score of 3 or higher is the cutoff for clinically significant PTSD symptoms (Response options: 0 = no, 1 = yes). Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CESD-10; Miller, Anton, & Townson, 2008). The CESD-10 (10 items; α = .80) is a brief screening measure for assessing levels of past-week depressive symptoms (range 0–29). A score of 10 or higher is the cutoff for clinically significant depressive symptoms. Each symptom item is rated according to its frequency of occurrence using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time; < 1 day) to 3 (all of the time; 5–7 days).

For overall health, participants were asked how they would rate their health during the past 4 weeks. The responses options included excellent, very good, good, fair, poor, and very poor. For self-harm, suicidal thoughts, attempted suicide, drug use, and eating disorder, participants were asked how often they had the problem (burning or hurting i.e., self-mutilation), suicidal thoughts, attempted suicide, drug use, and eating disorder) in the past year for any reason. The response options included never/not at all, once, a few times, many times, every day, or almost every day. A dichotomous variable was created with two categories: never/not at all and once or more than once.

Quantitative analysis

Using descriptive statistics such as chi-square, we examined health characteristics of women with CVE such as self-rated health, self-cutting, suicidal thoughts, attempted suicide, drug use, eating disorder, depression, and PTSD and how they differed from women without CVEs. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 21.0.

Results

Qualitative findings

The qualitative analysis (n = 9) revealed a wide range of severe abuse experiences spanning physical (e.g., choking, biting, hitting, punching), psychological (e.g., threats to kill, controlling behaviors) and sexual (e.g., forced sex) IPA. In addition, women experienced childhood abuse, witnessed domestic violence in childhood, and reported clinically significant depression and/or PTSD symptoms. Further, women discussed the complex and damaging effects of violence in their lives in the form of embarrassment, shame, lingering feelings for the abuser, and trust issues with any new relationship.

In the sections below, we discuss (a) how childhood abuses affect their adult experiences, (b) how they coped with intimate partner abuse, (c) sources of strength, and finally (d) turning points: what made them decide to leave their abusive partner. After each quote, the participant’s ID, age, and location are indicated.

Cumulative violence: Influence of childhood experiences

All nine women reported experiences of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse that occurred during their childhood, which played a part in making them more vulnerable to abuse as adults. For example, one participant said, “I had low self-esteem as a small girl. Yeah, I been through a lot of abuse [as a child], but not really sexual abuse, but abuse from family too, verbally” (U2507, Age unknown, USVI).

High levels of childhood abuse helped to normalize later life abuse from partners. As one participant explained, childhood memories often resurfaced during incidences of adult abuse, “I mean, [abuse from my partner] wasn’t nothing that I haven’t gone through already […]. At the time, it brought back memories of my child abuse, but it’s nothing that I did not go through already” (U1319, Age 25, USVI).

Coping with intimate partner violence

Women described a range of strategies to deal with their abusive partners such as seeking safety, verbal/ confrontational coping, and seeking informal and formal support.

Seeking safety

Two Baltimore women sought safety through formal protection from abuse orders or at a domestic violence shelter. One of the women from the USVI sought formal measures of safety, such as protection from abuse orders, but used more informal measures for ensuring safety, “He left the same day pissed off whatever, because I made sure I stayed in a public area” (U1179: Age 21, USVI). One woman took it upon herself to ensure she was safe by running from her abuser.

It was a cold night time and he sort of trapped me between maybe two buses and just was holding me there so I wouldn’t go. He was like I am not letting you go. He thought that I was leaving him. I finally broke free, lost a shoe and ran up the street. (U1179: Age 21, USVI)

Verbal/confrontation coping

Three of the five women from Baltimore and three of the four women from USVI reported confronting their abusers either verbally or physically. Two incidents of verbal confrontation are reflected in the following quotes: “He was walking me home and I was telling him I am done with him. I’m done” (U1179: Age 21, USVI). The second woman said, “Because I’m not really that weak in some kind of sense in my mind, I could always fight back with the words also” (U1081: Age 34, USVI).

Confrontation included actions in addition to words. One participant described her efforts to fight back her abuser:

I eased my way to the kitchen after they let me go and I got that knife and went out that back door and he was gone. But I chased him a block and half with that knife because I told him I’d kill him. (B5702: Age 48, Baltimore)

Seeking informal support

Some women received support from family members and friends, which helped them cope with the violence they experienced:

[I was able to talk about abuse]. [His family members]…would see it. They would tell him about it, but he wouldn’t listen to them. His cousin, which we were living with, used to tell him that if you don’t behave, or you don’t watch out she is going to leave you. (U1319: Age 25, USVI)

Another woman used her familial supports for more than coping, “I made his mother kick him out the house” (U1179: Age 21, USVI).

One participant reported talking to her best friend and cousin about the abuse without being judged:

I talked to my best friend and…to my favorite person in the whole world- my cousin. I and she are closer than my own sister. She wouldn’t down me, like—“You are stupid, you need to leave him, you need to do this…you need to do that.” She would be like—“If you need to…stay here for a little while you can. But, as you can see, it’s really not working’ out, when did you want to do something about it?” (B5975: Age 30, Baltimore)

Seeking formal support

Baltimore women were more likely to seek formal sources of support. Four Baltimore women filed formal protection from abuse orders, sought shelter at a domestic violence shelter, or disclosed their abuse during professional counseling sessions. One woman from the USVI mentioned seeking care from local health professionals and law-enforcement officers under fictitious names and that her police reports were sealed, whereas another filed a restraining order against her abusive partner, “I had to get a restraining order on him but he still kept on coming by me” (U1179: Age 21, USVI).

My sister called the police on him because she said he robbed me. When the police came out, they saw the hole in the wall and what’s going on-domestic violence. They sent me to the House of Ruth because he was locked up and he got out a jail. I had a restraining order against him, and he was calling my job from jail—he was like weeks stalking me from jail. And then he got out a jail and started coming around where I lived at. And that’s when, I contacted the detectives, and they came and relocated me and the kids to the House of Ruth. (B5975: Age 30, Baltimore)

Sources of strength

Women’s sources of strength appeared to play a significant role in increasing their ability to address abuse and healing from lifetime trauma. Women identified internal and external sources of strength. Internal sources included self-reliance and engaging in self-motivation. External sources included social support and spiritual guidance from a religious institution.

Internal sources of strength–self-reliance/belief in self

Women described their abusive relationships as a learning experience. They viewed themselves as independent and strong to move ahead in life, as reflected in the following quotes: “I feel it’s time for me to develop myself, get myself in order before I jump into anything. I have to learn to be independent. I see that I was dependent on a lot of men” (U1179: Age 21, USVI).

Another woman said,

He cheated. He hit me. He used objects on me…pulled my hair. He verbally abused me. He physically abused me…sexually abused me. I look at it now as a learning experience. Because of it I am a stronger woman. (U1319: Age 25, USVI)

All women mentioned developing self-reliance either through self-coaching or gaining financial independence as types of strength that helped them move on, as described by the following participant, “[The most helpful in dealing with this situation] has been myself” (U1319: Age 25, USVI).

For others, self-reliance manifested:

I really did it on my own…I got my life in order on my own, I stayed on top of them—police and detectives and made sure they locked his ass up and make sure he wouldn’t harass me no more. I got him locked up a couple times. (B5975: Age 30, Baltimore)

Internal strength combined with a desire for change played a role in helping women leave their abusive relationship:

It’s hard, but you are the one who have to be strong to get out […] it’s something you have to make up your mind to get out of[…]. People can talk. You can try this. It’s not going to work. You have to want it. You have to be the one to want to do it. (U2507: Age, 36, USVI)

External sources of strength

Women’s external sources of strength were people in their informal and formal network as well as religious sources in the community. Women shared how their family member was a source of strength and offered appropriate help and support, “My mom [supported me]. I have my sister, one of my brothers [and] my other brother. Me and [my cousin] are closer than my own sister” (B5975: Age 30, Baltimore).

Several women had family members who stepped in to help stop the abuse, “My sister…would always come down and tell him that he better leave me alone. And if he didn’t…how she was going to hurt him or my brothers were going to do whatever to him” (B5702: Age 48, Baltimore). Another noted, “His cousin, who we were living with, used to tell him that if you don’t behave, or you don’t watch out she is going to leave you” (U1319: Age 25, USVI).

“My sister called the police on him because she said he robbed me” (B5975: Age 30, Baltimore). For one woman, religion was the most helpful resource for her in dealing with abuse.

[The most helpful when [I was] dealing with [abuse] was Jesus…. All I know, Jesus is paying my bills. My godmother taught me this gospel song: “Count your blessings, and name them one by one. Count your blessings to see what God has done.” I got three godmothers. So, I’m okay. (B5702: Age 48, Baltimore)

Further, she described how her professional therapy session helped in her process of growth and healing:

This guy did a [therapy] session where he played soft music and told us to close our eyes. And while our eyes were closed, he guided us down this path. We walked with him down this path with our eyes closed. And we kept hearing this child cry. And bottom line, he said, “Now open your eyes and see who it is.” And it was actually us, sitting in the middle of this park on this rock crying. He said, “Now I want you to pick that child up, and hug that child, and tell him it’s gonna be okay.” And that was the beginning of my process. (B5702: Age 48, Baltimore)

Turning points: Reasons for deciding to leave

Although women described going back and forth in terms of leaving and returning, there were some turning points where women decided to finally break free from the abusive relationship. Among women in Baltimore, turning points or reasons for leaving involved more escalated incidents of violence or fear for lethality than their USVI counterparts.

Fear of grave harm

Fear of great harm was a reason why three women left their abusive relationship. “Someone was going to get hurt. I was in fear of my life” (B5945: Age 30, Baltimore) said one participant who’s abuser attempted to push her out of a moving car. Another woman explicitly mentioned fear of homicide, though this reason was implicitly mentioned in other interviews, “I was seeing how bad it was getting and I was to the point, well, the next thing you know, he’ll be picking up a gun onto my head” (B5808, Age: 52, Baltimore).

Self-awakening

For another participant, her turning point was not only threats to her life, but self-awakening after she spoke to another survivor of IPA. She said, “He tried to choke me again. It was time for me to get out of it because he was trying to kill me…. I decided I was going to leave him.” This incident catalyzed her self-awakening:

This man beat this girl and I’m telling her, “You don’t have to be in this relationship.” Then I thought about me. Well why am I in it? So that woke me up to teach her to get out of it. (B5702: Age 48, Baltimore)

Cheating

A participant from USVI shared that the turning point in her life came when her partner cheated on her and lied about it, “He cheated on me and he lied and covered it up and I just didn’t want to be in the situation anymore. I ended it” (U1319: Age 25, USVI). She was able to finally leave her partner when she got into a new relationship.

Robbery

For one participant, the turning point was when her partner robbed her:

When I was asleep he came in and took all the money out of my wallet. He knew the pin code to my bank card, so he took all the money out of my savings and checking accounts. The only thing that was left was the money order for the kids’ day care. And then he took my keys so I couldn’t leave. I had to be at work at 7:30 and I couldn’t even let myself back in the house because my door automatically locks. I needed somebody to let me back in while I take the kids to school. So that was the last straw. (B5975: Age 30, Baltimore)

This woman and her children ended up seeking housing at a domestic violence shelter under the advisement of local authorities.

Quantitative analysis

More than one half of the women with CVEs in intimate partner relationships had clinically significant depressive symptoms (60.1%), and 35% met criteria for clinically significant PTSD. There were significant differences between abused women with CVE in intimate partner relationships (n = 163) and those without CVE (n = 380) on health characteristics such as depression, PTSD, self-mutilation, suicidal thoughts, attempted suicide, drug use, eating disorder, and overall health. A significantly greater proportion of women in the cumulative violence group than those in the noncumulative violence exposure group reported engaging in self-mutilation (19.6% vs. 7.8%), having suicidal thoughts (31.3% vs. 19.0%), having attempted suicide (20.4% vs. 9.9%), problem with drug use (17.2% vs. 9.1%), and eating disorder problem (44.8% vs. 28.8%) in the past year. Women with CVE in intimate partner relationships were also significantly more likely than those without CVE to self-rate their overall health as fair, poor, or very poor (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Health Characteristics of Abused Women in the Quantitative Survey.

| Cumulative Violence Exposures (n = 163) |

Women without Cumulative Violence Exposures (n = 380) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 60.1 | 44.7 | .001 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 35.0 | 15.8 | .000 |

| Self-mutilation | 19.6 | 7.8 | .000 |

| Suicidal thoughts | 31.3 | 19.0 | .002 |

| Attempted suicide | 20.4 | 9.9 | .001 |

| Drug use | 17.2 | 9.1 | .008 |

| Eating disorder | 44.8 | 28.8 | .000 |

| Self-rated overall health | |||

| Poor or very poor | 9.8 | 5.6 | .000 |

| Fair | 36.2 | 20.2 | |

| Excellent, good or very good | 54.0 | 74.3 |

Note. Percentages presented are within violence group percentages.

Discussion

This study focused on women with CVEs, using qualitative and quantitative data collected from Black women living in the United States and the USVI. Drawing from the strengths perspective and transtheoretical model of change, the study identified turning points or factors that motivate women who experience IPA to create change within their relationship (i.e., leave or prepare to leave) as well as their coping strategies and sources of strength. The quantitative analysis was used to understand additional challenges women with CVEs face in terms of their overall health and well-being. Despite extreme challenges related to safety, health, and well-being that women with CVEs face, women were found to utilize numerous sources of strengths for changing their abusive situations.

Women in both settings experienced childhood physical and/or sexual abuse, and many witnessed domestic violence in their childhood homes. The experiences normalized the abuse they suffered later in life. The level of women experiencing IPA in this study experienced was extreme. Almost all of the women screened as in extreme danger of being killed by their intimate partner (based on their scores on the Danger Assessment; Campbell et al., 2009), and most had depression, PTSD, suicidal thoughts, and/or low self-esteem as a result. Our findings highlight the sources of strength and internal resources women find to cope with these life circumstances. The importance of assessing lifetime cumulative violence experiences and its effect on Black women’s health are vital to gain in-depth understanding of these women’s lives. As other research indicates, cumulative victimization experiences can negatively affect self-care agency (i.e., abilities to address abuse), since violence erodes women’s self-esteem, motivation, and energy (Campbell, & Soeken, 1999) and contributes to poor health (Sundermann et al., 2013).

Research also shows that poor health may interfere with women’s ability to access resources and to actively engage in safety planning (Perez & Johnson, 2008). This may increase their risk for victimization by severe violence or homicide by an intimate partner (Perez & Johnson, 2008; Sabri, Stockman et al., 2013). However, the women in this study demonstrated that turning points and sources of strength ultimately enhanced their well-being. Thus, practitioners should assess the mental health needs of women who are battered and the impact of these problems on their engagement in safety planning. The Affordable Healthcare Act (ACA) in the United States provides clinicians with the opportunity to screen for IPA via routine health care appointments and may be one avenue to discuss safety plans and methods to cope with violence (The White House, 2015).

As previous research has indicated, leaving an abusive relationship is a process (Enander & Holmberg, 2008). Women in this study experienced multiple forms of IPA but remained in the abusive relationship for some time. They reported diverse ways of dealing with violence such as staying away from the abuser, and avoiding being alone with him. Several women in the USVI confronted their abuser, whereas only one woman from the United States did so.

To cope with the abuse, women in this study drew from internal and external sources of support, which protected them from the negative impact of abuse. Becoming self-reliant and receiving support from family members, friends, and religion were sources of strength that empowered women to terminate their abusive relationships, which is consistent with previous research (Davis, 2002; Fowler & Hill, 2004). Most women did not seek legal intervention despite being in extreme danger of lethal violence at the hands of their partner; only two women from Baltimore and one from the USVI sought a restraining order to address their partner’s abuse. It is unclear why so few women from the USVI sought police protection; however, cultural norms that discount violence against women may play a part. The one woman from the USVI who did contact the police used a fake name. For women who are battered, abuse is not the only factor in decisions to leave (Campbell et al., 1998).

Women in this study described how turning points contributed to their decision to break free from their abusive relationship. Turning points reported in the literature are access to external support, which changes view of their situation from one of feeling trapped and isolated to one of feeling hopeful for change and relief from abuse (Chang et al., 2010). In this study, the turning points that prompted the end of relationships were not the first abusive incidents. In Baltimore, the turning points were often violence that endangered a woman’s life or posed harm to her child. Turning points for the women from the USVI were realization and growing tired of the situation. For one participant from the USVI, her abusive partner’s infidelity and subsequent exposure to a sexually transmitted disease influenced her decision to leave. The influence of abuser’s infidelity and threat to life on women’s decision to end a relationship is consistent with previous literature on women who are battered (Campbell et al., 1998; Chang et al., 2010).

Implications for research and practice

Our findings are useful for social work practitioners providing care to African American and African Caribbean women who experience CVEs. This study highlighted some of the cultural nuances faced by Black survivors of IPA in the United States and USVI, such as access to resources and coping methods. More research is needed to understand whether greater access to police and legal intervention (i.e., orders of protection) to women in USVI would increase their safety. In the United States, collaborative interventions between police and social services have shown to increase protective actions (Messing et al., 2011; Messing et al., 2014).

Our findings also illuminated a myriad of reasons why Black women decide to leave abusive relationships in adulthood given a history of violent experiences in their early life years. Although we know experiencing violence is cyclic and often persists into adulthood, a gap exists regarding the ideology of change among Black women. This study shed light on the impact of resiliency, social norms, and stages of change, which are key factors to include in interventions developed for women who have experienced life-long abuse. In future studies, additional research should be conducted to further capture cultural differences among Black women and factors that drive their motivation to leave abusive relationships or change their ability to remain safe while in an abusive situation. This information can then be used to inform individualized, culturally competent care and to develop targeted interventions that address the concerns of women who have experienced an accumulation of violence in their lifetime. Specifically, indicators to assess readiness for change may be useful in providing appropriate support to victims of IPA by way of counseling and safety planning. Interventions that help women to safely leave an abusive relationship can help reduce the public health costs associated with IPA.

Limitations

Although this study is an important contribution that focuses on lifetime cumulative victimization experiences of Black women in the United States and in the USVI, findings must be considered in the context of certain limitations. Because this study focused on two groups of Black women, our findings may not be generalized to other racial/ethnic groups or Black women from other countries such as Africa. Moreover, women may not have felt at ease disclosing all their experiences, and the retrospective nature of the study may have resulted in recall bias. Nevertheless, the study is an important contribution to the literature on Black women who are ethnically diverse with cumulative abuse histories.

Conclusion

Violence experienced throughout the lifetime has serious consequences for the health of women. It is important to understand how ethnically diverse Black women with CVEs cope with and survive abuse to enhance their help-seeking behavior. The findings of the study highlight the importance for consideration of internal and external sources of strength for developing intervention plans for women’s safety and well-being. Practitioners must assess for cumulative violence experiences, and the impact of these experiences on women’s overall health, safety, and help seeking. Individual-level interventions may focus on addressing their health care needs, promoting health coping, developing safety plans, and empowering women to live violence-free lives. Policies must be in place to support women experiencing abuse at all levels, and to minimize their barriers to seeking formal sources of help.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Grant# P20MD002286), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (T32-HDO64428; support for Bushra Sabri, Kamila Alexander, Charvonne Holliday, and Andrea Cimino).

References

- Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report. 2008;13(4):544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, Denison JA, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. Ending intimate partner violence: an application of the transtheoretical model. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28(2):122–133. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JG, Mahoney P, Gielen A, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. Defining appropriate stages of change for intimate partner violence survivors. Violence and Victims. 2009;24(1):36–51. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Rose L, Kub J, Nedd D. Voices of strength and resistance: A contextual and longitudinal analysis of women’s responses to battering. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1988;13(6):743–762. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Soeken KL. Women’s responses to battering: A test of the model. Research in Nursing & Health. 1999;22:49–58. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199902)22:1<49::aid-nur6>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Weber N. An empirical test of a self-care model of women’s responses to battering. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2000;13(1):45–53. doi: 10.1177/08943180022107276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Webster DW, Glass N. The danger assessment: Validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(4):653–674. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S, Smith E, Snyder H, Rand M. Female victims of violence. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, NCJ 228356; 2009. Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/fvv.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Dado D, Hawker L, Cluss PA, Buranosky R, Slagel L, Scholle SH. Understanding turning points in intimate partner violence: Factors and circumstances leading women victims toward change. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(2):251–259. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE. “The strongest women”: Exploration of the inner resources of abused women. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12(9):1248–1263. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebaugh HRF. Becoming an ex: The process of role exit. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Enander V, Holmberg C. Why does she leave? The leaving processes of battered women. Health Care for Women International. 2008;29:200–226. doi: 10.1080/07399330801913802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler DN, Hill HP. Social support and spirituality as culturally relevant factors in coping among African American survivors of partner abuse. Violence against Women. 2004;10(11):1267–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems. 1965;12(4):436–445. [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K. Conducting life history research with adolescents. Qualitative Health Research in Nursing & Health. 2004;14(9):1309–1319. doi: 10.1177/1049732304268628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Yahia MM, Eldar-Avidan D. Formerly battered women: A qualitative study of their experiences in making a decision to divorce and carrying it out. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage. 2001;36:37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hien D, Ruglass L. Interpersonal partner violence and women in the United States: an overview of prevalence rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2009;32(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugman SD, Witting MD, Furuno JP, Hirshon JM, Limcango R, Perisse ARS, Rasch EK. Perceptions of help resources for victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:766–777. doi: 10.1177/0886260504265621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Franc E, Samms-Vaughan M, Hambleton I, Fox K, Brown D. Interpersonal violence in three Caribbean countries: Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago. Pan American Journal of Public Health. 2008;24(6):409–421. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892008001200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, Ullman SE. The impact of multiple traumatic victimization on disclosure and coping mechanisms for Black women. Feminist Criminology. 2013;8(4):295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LL. Development of the severity of violence against women scale. Journal of Family Violence. 1992;7:103–121. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod AL, Hays DG, Chang CY. Female intimate partner violence survivors experiences with accessing resources. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2010;88:303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Messing J, Cimino A, Campbell J, Brown S, Patchell B, Wilson JS. Collaborating with police departments: Recruitment in the Oklahoma Lethality Assessment (OK-LA) Study. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(2):163–176. doi: 10.1177/1077801210397700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messing JT, Campbell J, Brown S, Patchell B, Androff D, Wilson J. The association between protective actions and homicide risk: Findings from the Oklahoma Lethality Assessment Study. Violence and Victims. 2014;29(4):543–563. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-13-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WC, Anton HA, Townson AF. Measurement properties of the CESD scale among individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:287–292. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem D. Nursing: Concepts of practice. 5th. New York, NY: Mc. Graw-Hill; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Parks SE, Kim KH, Day NL, Garza MA, Larkby CA. Lifetime self-reported victimization among low-income, urban women: The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adult violent victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(6):1111–1126. doi: 10.1177/0886260510368158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez S, Johnson DM. PTSD compromises battered women’s future safety. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(5):635–651. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Cameron RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, Sheikh JI. The Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics (PDF) Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemete CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GE. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58(3):307–321. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B, Bolyard R, McFadgion A, Stockman J, Lucea M, Callwood GB, Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence, depression, PTSD and use of mental health resources among ethnically diverse black women. Social Work in Health Care. 2013;52(4):351–369. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.745461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabri B, Stockman J, Bertrand D, Campbell D, Callwood G, Campbell JC. Victimization experiences, substance misuse and mental health problems in relation to risk for lethality among African American and African Caribbean women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28(16):3223–3241. doi: 10.1177/0886260513496902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleebey D. The strengths perspective in social work practice: Extensions and cautions. Social Work. 1996;41(3):296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Earp JA, DeVellis R. Measuring battering: development of the women’s experience with battering (WEB) scale. Women’s Health. 1995;1(4):273–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundermann JM, Chu AT, DePrince AP. Cumulative violence exposure, emotional non-acceptance, and mental health symptoms in a community sample of women. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2013;14:69–83. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2012.710186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. Presidential proclamation–National Domestic Violence Awareness Month, 2015 [Press release] 2015 Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/09/30/presidential-proclamation-national-domestic-violence-awareness-month.

- Yin RK. Case study research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihama M, Bybee D. The life history calendar method and multilevel modeling: Application to research on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(3):295–308. doi: 10.1177/1077801211398229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]