Abstract

Development of the human nervous system involves complex interactions between fundamental cellular processes and requires a multitude of genes, many of which remain to be associated with human disease. We applied whole exome sequencing to 128 mostly consanguineous families with neurogenetic disorders that often included brain malformations. Rare variant analyses for both single nucleotide variant (SNV) and copy number variant (CNV) alleles allowed for identification of 45 novel variants in 43 known disease genes, 41 candidate genes, and CNVs in 10 families, with an overall potential molecular cause identified in >85% of families studied. Among the candidate genes identified, we found PRUNE, VARS, and DHX37 in multiple families, and homozygous loss of function variants in AGBL2, SLC18A2, SMARCA1, UBQLN1, and CPLX1. Neuroimaging and in silico analysis of functional and expression proximity between candidate and known disease genes allowed for further understanding of genetic networks underlying specific types of brain malformations.

INTRODUCTION

Human brain development is a precisely orchestrated process requiring multiple genetic and epigenetic interactions and the coordination of cellular and molecular mechanisms, perturbation of which leads to a plethora of neurodevelopmental phenotypes depending on the spatial and temporal effect of the disturbance. Neuronal development has been categorized into three main processes: neurogenesis, neuronal migration, and postmigrational cortical organization and circuit formation. Classification of the various malformations of cortical development has evolved to reflect these underlying developmental processes (Barkovich et al., 2012; Mirzaa and Paciorkowski, 2014). Although such classifications recapitulate the main developmental steps in brain formation, recent advances challenge the implied boundaries between these clearly defined stages and suggest that the genes implicated in many developmental stages are genetically and functionally interdependent. Ultimately, this can lead to a more pragmatic classification of neurodevelopmental phenotypes that relies primarily on knowledge of genes and gene networks and manifests as dysfunction(s) in mechanisms of protein and pathway actions (Barkovich et al., 2012; Guerrini and Dobyns, 2014).

A fundamental question in the study of brain malformations is the role of structural abnormalities in promotion of intellectual disability. The two have long been studied together, with particular focus on X-linked intellectual disability (XLID) and more recent studies on both autosomal recessive intellectual disability (ARID) and dominant de novo mutations. Genes involved in intellectual disability play a role in diverse basic cellular functions, such as DNA transcription and translation, protein degradation, mRNA splicing, chromatin remodeling, energy metabolism and fatty-acid synthesis and turnover (de Ligt et al., 2012; Gilissen et al., 2014; Najmabadi et al., 2011). Further coordinated study of brain malformations and intellectual disability offers the opportunity to potentially relate basic developmental features to elements of higher level cognitive function.

The advent of next generation sequencing has enabled rapid identification of numerous genes and mechanisms that underlie disorders of brain malformation and intellectual disability (Alazami et al., 2015; Najmabadi et al., 2011). Further advances are often limited by the availability of well characterized and rigorously phenotyped patients and the capacity for detailed analyses of gene function. In this study, we applied whole exome sequencing (WES) to a cohort of 208 patients from 128 mostly consanguineous families with congenital brain malformations and/or intellectual disability. Due to the possibility that some post-migrational brain malformations may not be evident on imaging, we did not exclude patients with isolated profound intellectual disability from this study. We describe the genes identified by rare variant analyses and highlight candidate novel genes that were either present in more than one family with a similar phenotype; clearly fit into known biological processes perturbed in neurodevelopment; or harbored homozygous loss of function (LOF) (i.e., stopgain, frameshift, or splice site) variants.

RESULTS

Neurological manifestations of patients in the study cohort

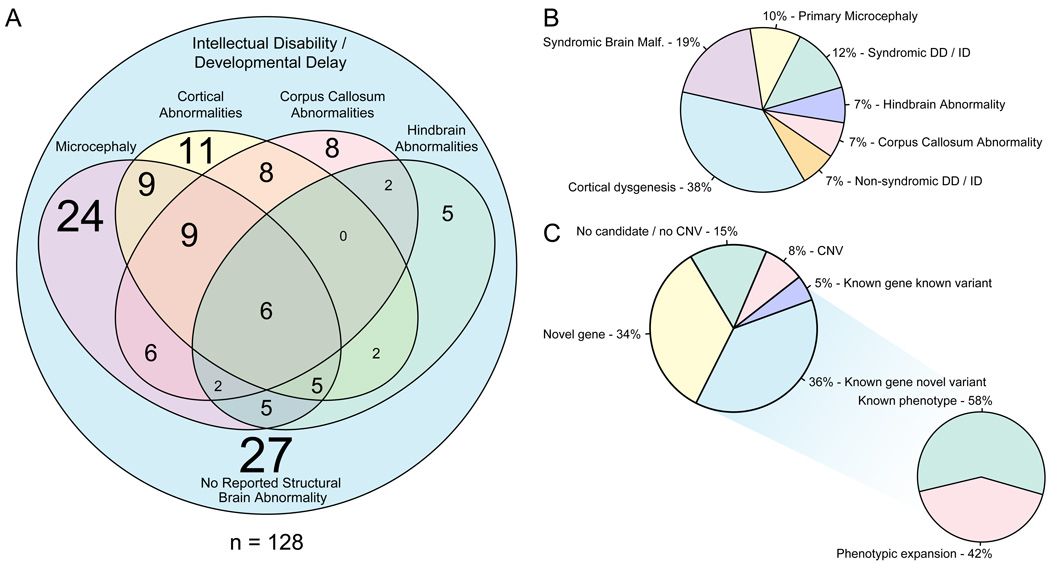

The central nervous system (CNS) features and pedigree structures of the 128 families are shown as Figure 1 and S1, respectively. According to their foremost central nervous system findings and accompanying clinical features (dysmorphic and additional systemic findings) we further classified probands into seven major groups: primary microcephaly (10%), cortical dysgenesis (38%), callosal abnormalities (7%), hindbrain malformations (7%), syndromic brain malformations (19%), nonsyndromic intellectual disability (7%), and syndromic developmental delay or intellectual disability (12%) (Figure 1B). Multiple affected members (proband and 1–2 siblings or cousins) were sequenced when available, and in singleton cases, either the trio (unaffected parents and affected proband) or only the proband were sequenced.

FIGURE 1. Phenotypic clustering of the cohort and summary of WES findings.

A. Venn diagram of clinical and neuro-radiological features. The font size of the numbers correlates with the number of individuals that represent any given category. B. Phenotypic clustering of the probands according to their most outstanding feature revealed seven major groups: primary microcephaly (10%), cortical dysgenesis (38%), callosal abnormalities (7%), hindbrain malformations (7%), syndromic brain malformations (19%), nonsyndromic intellectual disability (7%), and syndromic developmental delay or intellectual disability (12%). C. WES analysis revealed novel candidates in 34%, novel variants in known genes in 36%, known variants in known genes in 5%, CNVs in 8% of the families. 42% of the families with novel variants in known genes represent phenotypic expansion.

Analysis of WES data

Figure S2 describes the workflow used to identify candidate disease genes. We identified known variants in 5 known disease genes and 47 novel variants in 42 known disease genes; of these, 19 represented phenotypic expansions wherein trait manifestations were distinct from those previously reported in association with variation in that given gene (Table S1, Figure 1C). Variants of unknown significance (VUS) in known disease genes were considered probably associated with the disease if they segregated with the phenotype and were determined damaging or likely damaging by bioinformatic predictions by a majority of five different tools (see Experimental Procedures), with evolutionary conservation of the affected amino acid being a prerequisite for missense variants.

The above criteria were then used to screen for the strongest candidate genes in the remaining cases, with the addition of two factors: a) an internal database was screened to ensure that no potentially deleterious homozygous or compound heterozygous variants were present in control subjects without brain malformations in the specific gene of interest, and b) a comprehensive literature and database search was conducted to determine whether the function and expression pattern of the encoded protein could potentially be associated with the phenotype in question. Eventually, in 46 families (36%), we identified potential disease causing variants in 41 candidate disease genes (Table 1A, and S1; Figure 2C and S2). Rare variants were detected in the PRUNE, VARS, and DHX37 genes in more than one family segregating for a similar phenotype.

Table 1.

Detected SNVs in potential candidate disease genes (A) and CNVs (B) in the study cohort. (A) Potential candidate disease genes are ordered (stratified) from “most likely” pathogenic to “less likely”, whereas every single gene is the strongest candidate in any given individual. Please see “Experimental Procedure” for stratification criteria. (B) In four families, homozygous/hemizygous CNVs were detected while heterozygous in the remaining 6. Asterisk represents families with blended phenotype that presented both SNV and CNV in each affected individual. zyg: zygosity, het: heterozygous, hom: homozygous, hem: hemizygous

| A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proband | Gene | Transcript: nucleotide; protein | Zyg | |

| SZ51 | PRUNE | NM_021222: c.G383A; p.R128Q | Het | 46 Families, 41 Genes |

| NM_021222: c.G820T; p.G174X | Het | |||

| SZ322 | PRUNE | NM_021222: c.G316A; p.D106N | Hom | |

| BAB3500 | PRUNE | NM_021222: c.G316A; p.D106N | Hom | |

| BAB3737 | PRUNE | NM_021222: c.G316A; p.D106N | Hom | |

| BAB3186 | VARS | NM_006295: c.C2653T; p.L885F | Hom | |

| BAB3643 | VARS | NM_006295: c.G3173A; p.R1058Q | Hom | |

| BAB4627 | AGBL2 | NM_024783: c.C1747T; p.R583X | Hom | |

| BAB6167 | CPLX1 | NM_006651: c.G322T; p.E108X | Hom | |

| BAB4453 | SMARCA1 | NM_003069: c.C7T; p.Q3X | Hem | |

| BAB4019 | DHX37 | NM_032656: c.G1460A; p.R487H | Hom | |

| BAB4434 | DHX37 | NM_032656: c.C1257A; p.N419K | Hom | |

| BAB6569 | ACTL6B | NM_016188: c.G893A; p.R298Q | Hom | |

| BAB4471 | CEP97 | NM_024548: c.A1148G; p.H383R | Hom | |

| BAB6511 | CINP | NM_032630: c.T637G; p.X213G | Hom | |

| BAB5333 | KIF23 | NM_004856: c.T755A; p.L252H | Hom | |

| BAB4852 | OGDHL | NM_001143996: c.C2162T; p.S721L | Hom | |

| BAB3407 | SLC18A2 | NM_003054: c.705delC; p.G235fs | Hom | |

| BAB4452 | TTI1 | NM_014657: c.G2761A; p.D921N | Hom | |

| BAB3415 | TUT1 | NM_022830: c.G1411A; p.A471T | Hom | |

| BAB4748 | ANK3 | NM_020987: c.C9652T; p.L3218F | Hom | |

| BAB3408 | ARHGAP21 | NM_020824: c.T3491G; p.I1164R | Hom | |

| BAB6026 | ASH2L | NM_001105214: c.A1444G; p.I482V | Hom | |

| BAB3420 | ASTN1 | NM_004319: c.G2224C; p.G742R | Hom | |

| BAB4462 | C12orf34 | NM_032829: c.A284T; p.H95L | Hom | |

| BAB4860 | CDH4 | NM_001794: c.G1976C; p.R659P | Hom | |

| BAB5209 | CELSR2 | NM_001408: c.C3830T; p.P1277L | Hom | |

| BAB4930 | CSRP2BP | NM_020536: c.G1399A; p.E467K | Hom | |

| BAB5192 | DSCAML1 | NM_020693: c.G1411A; p.V471I | Hom | |

| BAB5013 | GTF3C1 | NM_001520: c.G4096A; p.E1366K | Hom | |

| BAB3740 | IGFBP4 | NM_001552: c.C698T; p.T233M | Hom | |

| BAB5373 | INA | NM_032727: c.G562A; p.G188R | Hom | |

| BAB4633 | KLHL15 | NM_030624: c.G1474A; p.V492I | Het | |

| BAB3480 | MXRA8 | NM_032348: c.T1238A; p.I413N | Hom | |

| BAB4830 | PLEKHG2 | NM_022835: c.G1708A; p.G570R | Hom | |

| BAB4519 | ROS1 | NM_002944: c.G1094C; p.G365A | Hom | |

| BAB5548 | SLITRK5 | NM_015567: c.G2515C; p.E839Q | Hom | |

| BAB5382 | SNAPIN | NM_012437: c.A163T; p.N55Y | Hom | |

| BAB3491 | SVIL | NM_003174: c.C2348T; p.S783L | Hom | |

| BAB4017 | TTC1 | NM_003314: c.T784G; p.F262V | Hom | |

| BAB4807 | UBQLN1 | NM_053067: c.377delA; p.N126fs | Hom | |

| BAB5605 | ULK2 | NM_001142610: c.A1733G; p.H578R | Hom | |

| BAB3410 | USP11 | NM_004651: c.G722A; p.R241Q | Hom | |

| BAB5379 | PTPRT | NM_007050: c.1561-3OT | Het | |

| NM_133170: c.T206C; p.V69A | Het | |||

| BAB5720 | CDK10 | NM_001160367: c.G857A; p.R286H | Hom | |

| uc002fob.2: c.C512G; p.T171S | Hom | |||

| BAB4698 | HELZ | NM_014877: c.A3322G; p.I1108V | Hom | |

| BAB4133 | TNN | NM_022093: c.G2516A; p.R839K | Hom | |

| B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAB | CNV location | Type | Included genes | Zyg |

| 3498 | chr6: 86201694–86282093 | del | SNX14 | Hom |

| 3747 | chr7: 147092700–147092873 | del | CNTNAP2 | Hom |

| 4097 | chr7: 153749905–158935238 | del | Many genes (5MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 4097 | chr15: 98512352–102463263 | dup | Many genes (4MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 4164 | chr14: 68129193–68162421 | del | RDH11, VTI1B | Het |

| 5029 | chr15: 51204274–51397374 | del | AP4E1, TNFAIP8L3 | Hom |

| 5040 | chr17: 43545574–44159909 | del | CRHR1, MAPT, KANSL1 | Het |

| 5481* | chr15: 22744254–23255388 | del | 15q11.2 | Het |

| 5503 | chr14: 20295607–24845308 | del | 146 genes (5MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 5687 | chr3: 194392792–197884541 | dup | Many genes (5MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 5687 | chr6: 348102–5999438 | del | Many genes (5MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 5866* | chrX: 31947712–31950345 | del | DMD | Hem |

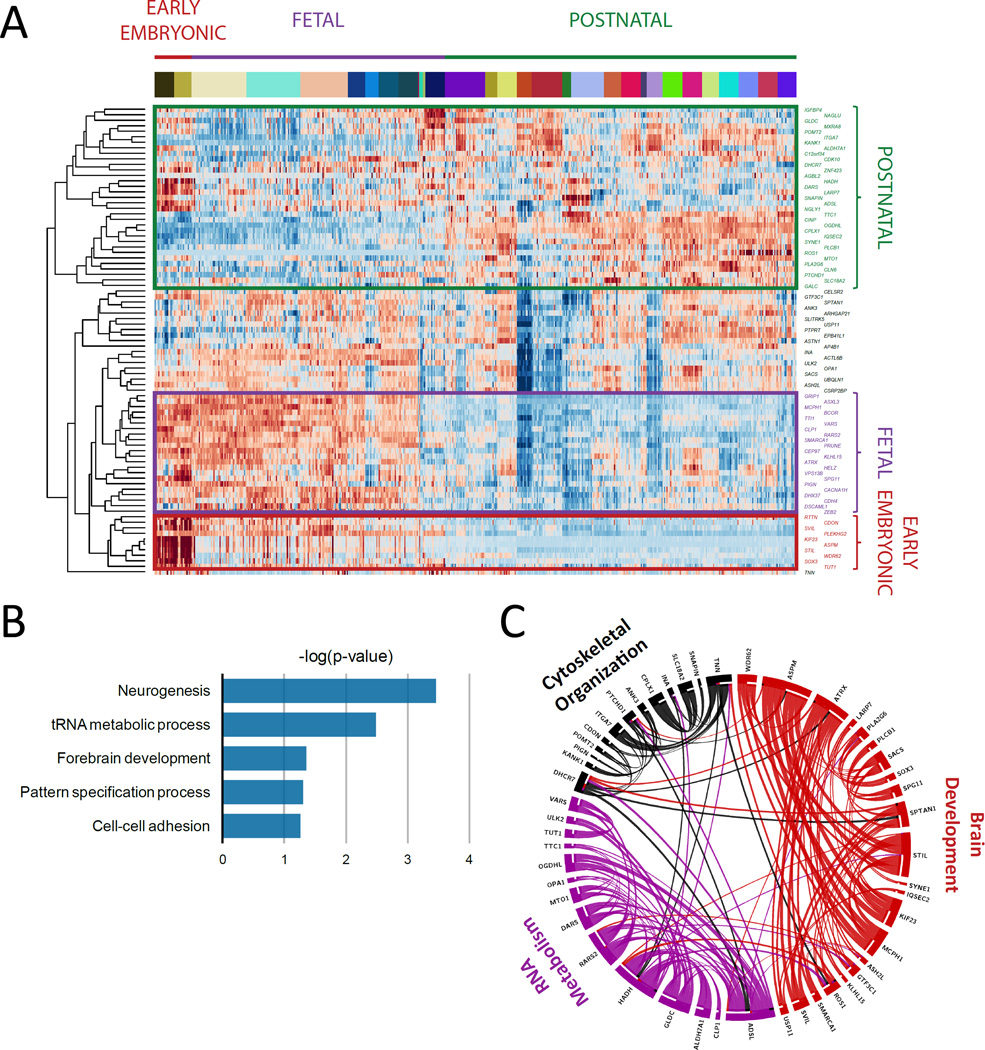

FIGURE 2. Expression, annotation, and pathway analysis of known and candidate genes.

A. Unsupervised clustering based on mRNA levels in the brain tissue partitioned the known and candidate genes into 4 subgroups: genes expressed only in early embryonic development, only in fetal development, only in adult brain tissue, and lastly in both embryonic development and adult tissue. KIF23, TUT1, CLP1, PRUNE, VARS, and DHX37 are included among the genes expressed only in early embryonic development or in fetal development. B. Biological functional annotation of the novel and known mutated genes in our cohort revealed that they were most significantly enriched in neurogenesis, tRNA metabolic process, forebrain development, pattern specification process, and cell-cell adhesion. C. The protein-protein interaction network had a greater degree of connectivity than expected by chance (P-value=3.26*10-3). This network revealed 3 highly interconnected protein networks, consisting of genes significantly enriched in brain development, RNA metabolism, and cytoskeletal organization.

Expression, annotation, and pathway analysis of known and candidate genes

Unsupervised clustering of the novel candidate and known mutated disease genes based on their mRNA levels in the brain tissue partitioned them into 4 subgroups: genes expressed only in early embryonic development, only in fetal development, only in adult brain tissue, and lastly in both embryonic development and adult tissue (Figure 2A). Biological functional annotation of the novel and known mutated genes in our cohort revealed enrichment of the collection in neurogenesis, tRNA metabolic processes, forebrain development, pattern specification process, and cell-cell adhesion (Figure 2B).

We next tested whether the novel and known mutated genes have a greater than expected degree of connectivity within a protein-protein interaction network, based upon the known and predicted protein-protein interaction score retrieved from the STRING database (http://string-db.org). The protein-protein interaction network had a greater degree of interconnectivity than expected by chance (P-value=3.26*10-3), and could be partitioned into 3 highly interconnected protein networks consisting of genes significantly enriched in brain development, RNA metabolism and cytoskeletal organization (Figure 2C).

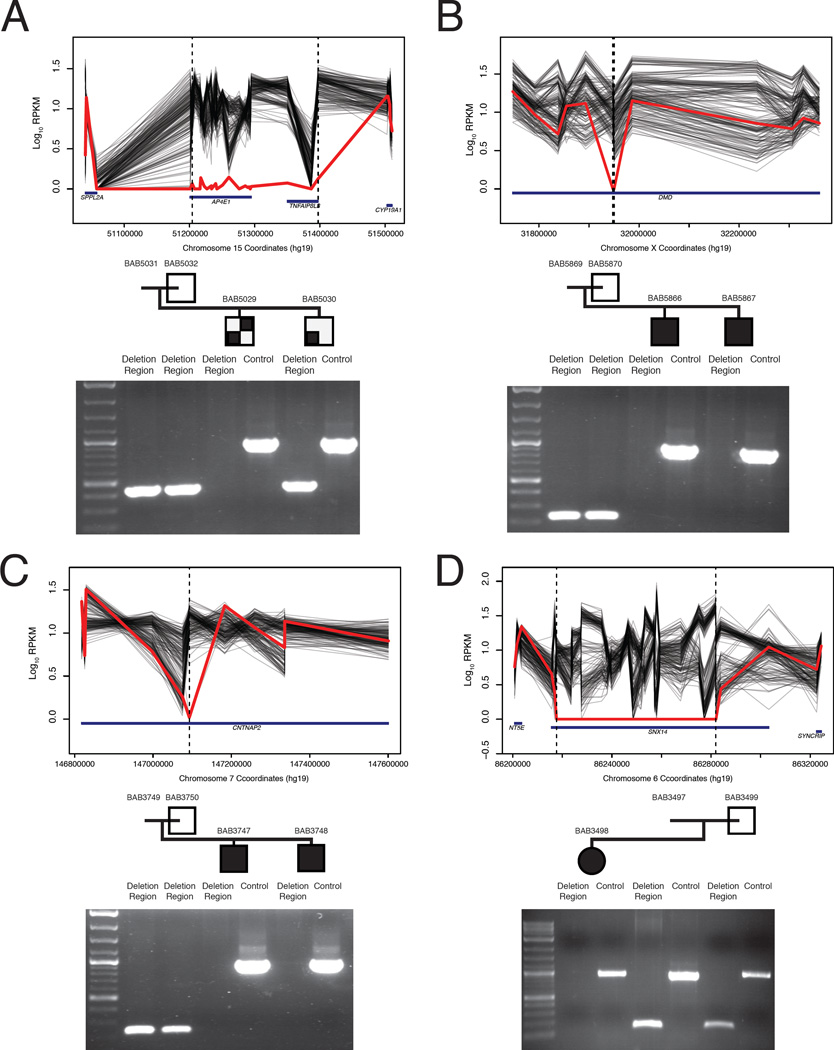

Copy number variant analysis

In addition to single nucleotide variant (SNV) analysis by WES, we performed systematic screening of the WES data for copy number variant (CNV) alleles and found likely pathogenic CNVs in 10 families (13 affected individuals) (Table 1B and S2; Figures 3 and 4). Among these families, we identified homozygous deletions in three consanguineous families. First, a ~64 Kb homozygous deletion encompassing almost the entire SNX14 gene was identified in patient BAB3498 with ID, microcephaly, and hypotonia (Figure 3D). Second, a 193 kb homozygous deletion encompassing almost the entire AP4E1 gene, previously associated with spastic paraplegia 51 (MIM# 613744), was found in patient BAB5029 with intellectual disability, microcephaly, seizures, spasticity, and hyperintensity changes in both cerebellar hemispheres and subcortical deep white matter (Figure 3A). Interestingly, his brother BAB5030 was not homozygous for this same deletion and retrospective analysis of their phenotypes indicated that unlike his brother, BAB5030 had neither abnormalities on MRI nor spasticity. The third family had a 173 bp homozygous intragenic deletion in CNTNAP2 identified in BAB3747 and BAB3748, siblings with intellectual disability and seizures (Tables 1B and S2; Figure 3). We also identified a hemizygous intragenic deletion interrupting exons 46 and 47 of DMD in two affected siblings, BAB5866 and BAB5867, with prominently elevated muscle enzymes (CK>10000 U/L). These siblings also showed a Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (MIM#270400) phenotype explained by a novel homozygous missense mutation in DHCR7 (Tables 1, Table S1 and S2; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Homozygous and hemizygous CNV’s.

A. Homozgous deletion encompassing AP4E1 in BAB5029 but not BAB5030. B. Hemizygous intragenic deletion of DMD interrupting exons 46 and 47; C. Homozygous intragenic deletion of CNTNAP2; and D. Homozygous deletion almost entirely encompassing SNX14.

PCR validation underneath each pedigree shows amplification or lack thereof of the deletion region and a positive control PCR of an unrelated locus. Amplification of the deletion region in parents and unaffected siblings indicates either a heterozygous (assumed for parents, as obligate carriers) or homozygous wild type state.

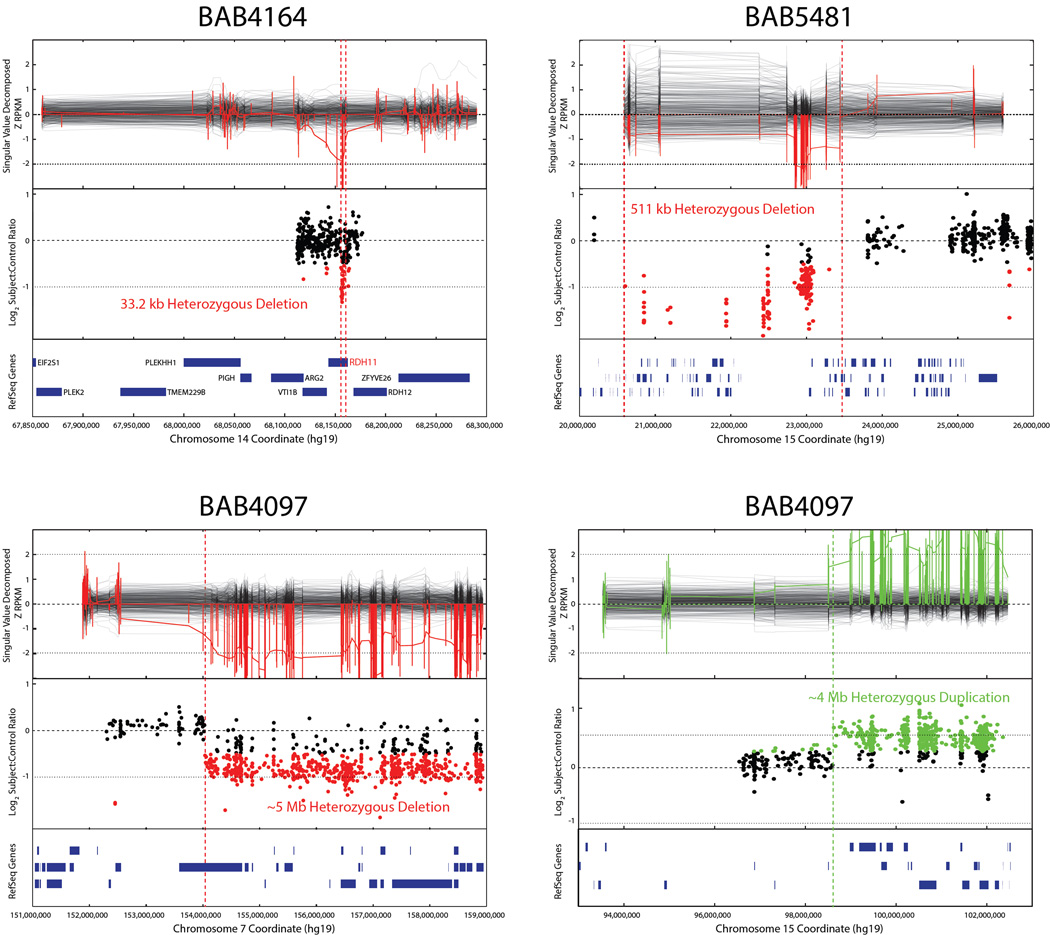

FIGURE 4. Heterozygous CNVs identified by whole exome sequencing.

Upper panel represents CNV as predicted from WES data; middle panel represents validation by array studies; and lower panel shows chromosomal position and RefSeq genes involved. Parental studies for CNVs were beyond the scope of this article.

In the remaining six families we found heterozygous deletions and duplications (Tables 1, 2 and S2; Figure 4). Review of the SNVs on the complementary chromosome did not reveal any reduction to homozygosity of a recessive variant in a known disease-associated gene in these loci. Two patients (BAB5687 and BAB4097) had both a terminal deletion and a terminal duplication, possibly suggestive of an unbalanced translocation. Patient BAB5040 had a 17q21.31 deletion ( 6Mb) involving KANSL1, a gene in which heterozygous deletion CNV and damaging intragenic SNV have been reported in association with Koolen-deVries syndrome (KDVS, MIM# 610443); patient BAB5481 had 15q11.2 deletion syndrome (MIM# 615656); patient BAB5503 had a 14q11.2 deletion; and patient BAB4164 had a 33 kb deletion including VTI1B and RDH11 (Tables 2 and S2; Figures 4 and S3).

Table 2.

Detected CNVs in the study cohort. In four families, homozygous/hemizygous CNVs were detected while heterozygous in the remaining 6.

| BAB | CNV location | Type | Included genes | Zyg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3498 | chr6: 86201694-86282093 | del | SNX14 | Hom |

| 3747 | chr7: 147092700-147092873 | del | CNTNAP2 | Hom |

| 4097 | chr7: 153749905-158935238 | del | Many genes (5MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 4097 | chr15: 98512352-102463263 | dup | Many genes (4MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 4164 | chr14: 68129193-68162421 | del | RDH11, VTI1B | Het |

| 5029 | chr15: 51204274-51397374 | del | AP4E1, TNFAIP8L3 | Hom |

| 5040 | chr17: 43545574-44159909 | del | CRHR1, MAPT, KANSL1 | Het |

| 5481* | chr15: 22744254-23255388 | del | 15q11.2 | Het |

| 5503 | chr14: 20295607-24845308 | del | 146 genes (5MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 5687 | chr3: 194392792-197884541 | dup | Many genes (5MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 5687 | chr6: 348102-5999438 | del | Many genes (5MB), see Supplementary Table 2 | Het |

| 5866* | chrX: 31947712-31950345 | del | DMD | Hem |

Asterisk represents families with blended phenotype that presented both SNV and CNV in each affected individual.

Candidate genes seen in multiple families with various cortical abnormalities

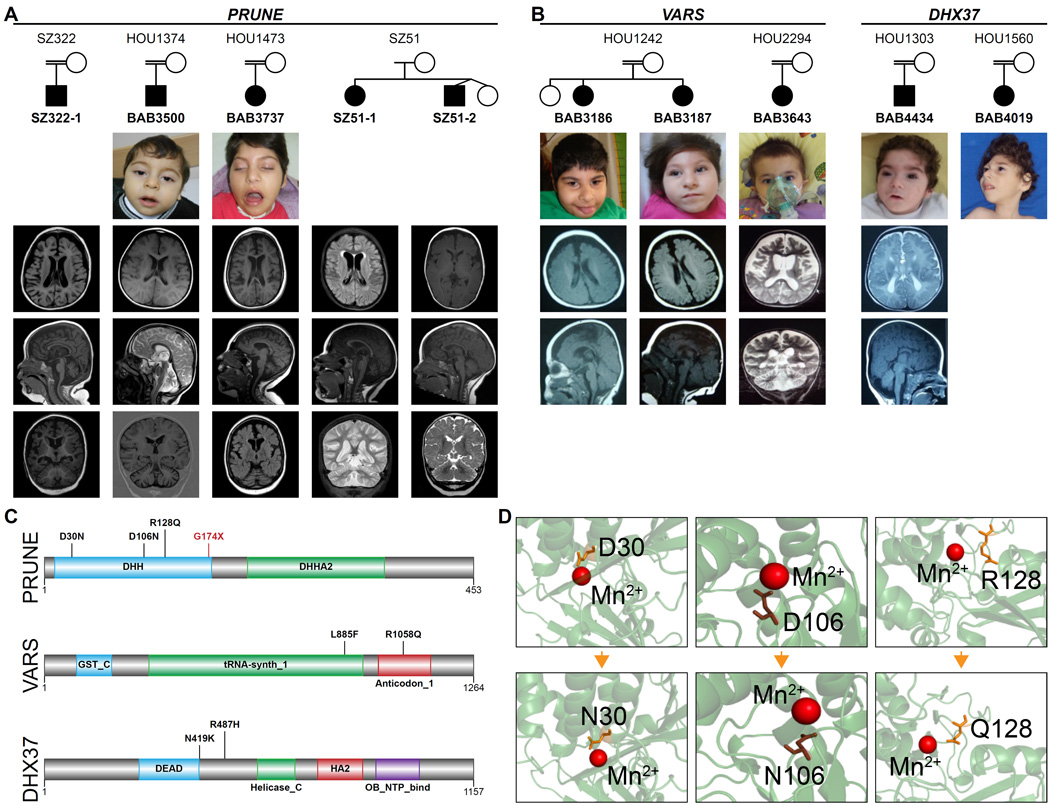

In our cohort, 48 families showed cortical dysplasia (atrophy, heterotopia, pachygyria or schizencephaly) with or without microcephaly, callosal abnormalities, and hindbrain involvement (Figures 1A and 1B). In this clinical phenotypic category, we highlight novel candidate genes in which likely deleterious variants were identified in more than one family: PRUNE (4), VARS (2), and DHX37 (2) (Tables 1A, Table S1; Figure 5A–D).

FIGURE 5. Patients with mutations in PRUNE VARS and DHX37.

A. Pedigrees of the families with PRUNE mutations show that 3 families (BAB3500 and BAB3737 are of Turkish origin, SZ322 is of Saudi origin) are consanguineous while SZ51 (US origin) is not. Available patient images reveal some dysmorphic features most probably a result of microcephaly. Note that axial, mid-sagittal and coronal slices from the brain MRIs of each patient demonstrate a similar phenotype consisting of cortical atrophy, thin/hypoplastic corpus callosum and prominent cerebellar atrophy. B. Families with homozygous VARS and DHX37 mutations presented with severe microcephaly, DD/ID, and cortical atrophy. C. The human PRUNE is a member of DHH superfamily, and contains DHH and DHHA protein domains at the N-l and C-termini respectively. Also note that human VARS is a multi-domain protein, containing N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST_N), C-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST_C), tRNA synthase class I (tRNA-synth_1) and anticodon-binding domain of tRNA (anticodon_1). L885F and R1058Q substitutions occur in the latter two domains respectively. DHX37 protein contains DEAD, Helicase_C, HA2 and OB_NTP_binding domains. N419K substitution occurs nearby the DEAD domain, which plays a role in several aspects of RNA metabolism processes such as translation initiation and pre-mRNA splicing, whereas the other substitution (p.R487H) locates between DEAD and Helicase_C domains. D. DHH domain of PRUNE carries a highly conserved motif of Asp-His-His (DHH). The aspartic acid in DHH motif of the human PRUNE was shown to bind Mg2+ (D’Angelo et al., 2004). Model structure for human PRUNE protein from SwissModel repository suggests that negatively charged D30 and D106 interact directly with the positively charged cofactor, while R128 and G174 are in close proximity to the catalytic site.

Potentially deleterious variants in PRUNE were identified in four families. In two apparently unrelated families from nearby villages in eastern Turkey, we identified an identical homozygous variant (NM_021222: c.G316A, p.D106N) in the PRUNE gene. Both probands (BAB3500 and BAB3737) presented with microcephaly, frontotemporal cortical atrophy and cerebellar atrophy (Figures 5A, 5C and 5D). Based on the proximity of the villages of the two families and the shared AOH surrounding the mutation (data not shown), we suggest that a founder effect likely played a role in the etiology (Karaca et al., 2014), as commonly seen in populations with high rates of consanguineous marriage. In a Saudi Arabian family (SZ322) in which parents were consanguineous, an 18 month old male patient with cerebral and cerebellar atrophy, microcephaly, seizures and severe developmental delay was found to be homozygous for a rare PRUNE (NM_02122:cG88A:p.D30N) variant. A fourth non-consanguineous family (SZ51) from the US with severe developmental delay, regression, seizures, and microcephaly marked by cerebral and cerebellar volume loss showed compound heterozygous (NM_021222:c.G383A:p.R128Q and NM_021222:c.G520T:p.G174X) variants shared by the two affected siblings. PRUNE (prune homolog, drosophila) is a phosphodiesterase member of the DHH phosphoesterase superfamily and highly expressed in the human fetal brain and fully confined to the nervous system in mouse embryos (Reymond et al., 1999). Its encoded protein plays a role in cell proliferation and induction of cellular motility in the cancer metastatic process via interaction with NME1 (non-metastatic cells 1, protein NM23A) (Aravind and Koonin, 1998; D’Angelo et al., 2004; Reymond et al., 1999). It has also been shown to cooperate with GSK-3 (serine/threonine kinase glycogen synthase kinase 3) in modulation of focal adhesions and thus to regulate cell migration (Kobayashi et al., 2006). Human PRUNE protein contains two main domains: a catalytic DHH domain, and an adjacent aspartic acid-histidine-histidine (Asp-His-His) family-associated motif 2 (DHHA2) domain. Of note, all of the ‘likely pathogenic’ variants identified in our patients map to the DHH domain (Figure 5C). The Turkish variant p.D106N changes one of the three conserved amino acids (Asp-His-His) that form the active site of the protein. Mutation of any of these three amino acids has been shown to severely decrease the enzyme’s activity to hydrolyze short-chain polyphosphates (Tammenkoski et al., 2008).

We detected two different homozygous potentially pathogenic variants in VARS that encodes valyl-tRNA synthetase, in two unrelated consanguineous pedigrees: NM_006295: c.G3173A, p.R1058Q in BAB3643; and NM_006295.2: c.C2655, p.L885F in siblings BAB3186 and BAB3187 (Figures 5B and C). All affected individuals presented with severe developmental delay, microcephaly, seizures, and cortical atrophy on MRI (Figure 5B). The phenotype of these affected individuals was similar to that of the families with the homozygous PRUNE variant and to the previously published patients with CLP1 mutations (Karaca et al., 2014), both in terms of severity and brain regions involved, and functional network analysis that suggested protein-protein interactions between VARS, PRUNE, and CLP1 (Figure 7).

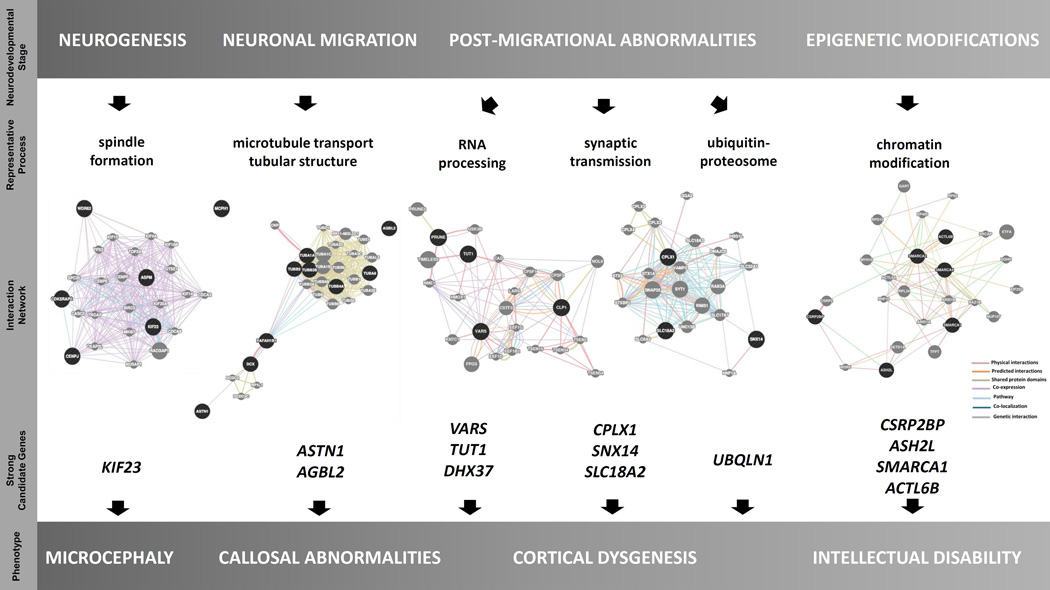

FIGURE 7. Suggested correlation between neurodevelopmental stage, representative process, strong candidate genes, and phenotype.

Selected genes and their protein-protein interactions are shown in terms of correlation with neurodevelopmental process and resultant phenotype.

In two unrelated families each with one affected proband (BAB4019 and BAB4434) we found two different homozygous variants (NM_032656: c.G1460A, p.R487H and NM_032656: c.C1257A, p.N419K, respectively) in the DHX37 gene (Figure 5B and 5C). BAB4019 presented with severe microcephaly, developmental delay, seizures, and cortical atrophy and BAB4434 presented with severe microcephaly, polymicrogyria, and dysgenesis of the corpus callosum (Figure 5B). DHX37 encodes a RNA helicase that is a member of the DEAD box protein subfamily, characterized by the evolutionarily conserved motif Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp (DEAD) (Bleichert and Baserga, 2007). DEAD box proteins are known to be implicated in embryogenesis, spermatogenesis, and cellular growth and division (de la Cruz et al., 1999; Jankowsky et al., 2001). In a recent study, it was shown that Dhx37 is required for the biogenesis of glycine receptors in zebrafish and thereby regulates glycinergic synaptic transmission and associated motor behaviors (Hirata et al., 2013). The authors do not comment on a central nervous system phenotype in the mutants.

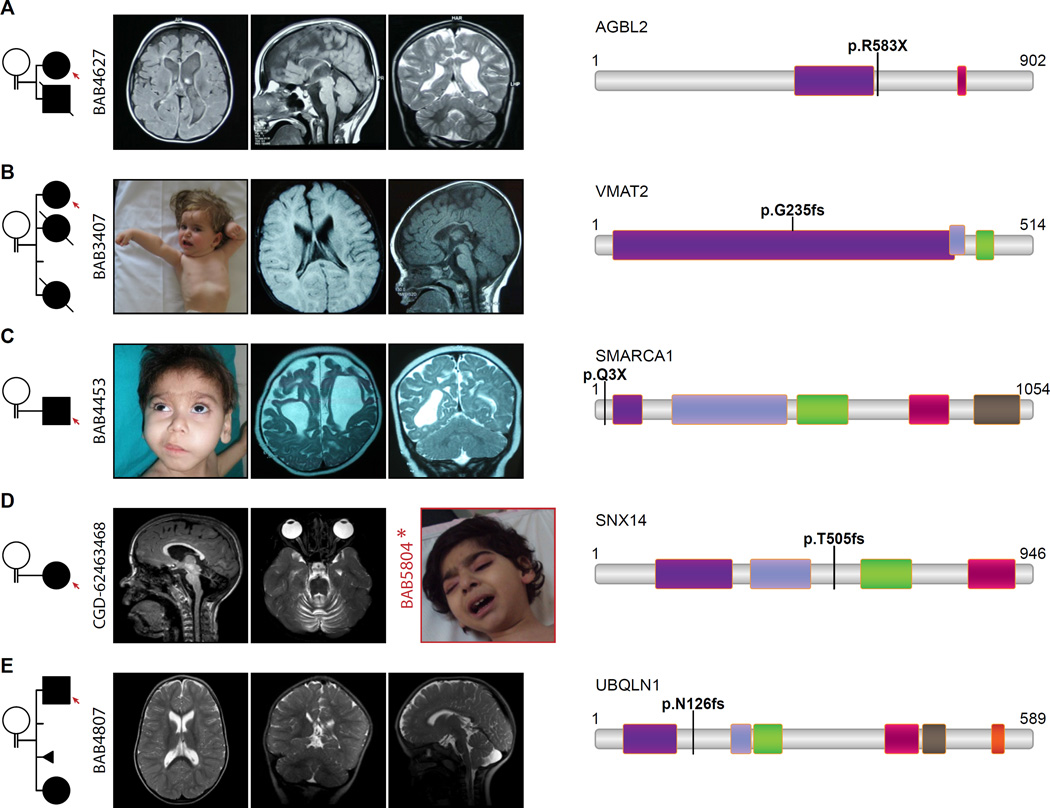

Patients with homozygous LOF variants in novel candidates

We further screened for any homozygous or hemizygous loss of function variants in our cohort. We verified that the observed loss of function variants affected all transcripts, checked whether it was in the last exon or last 55 bp of the penultimate exon which may escape nonsense mediated decay, and reviewed internal and publicly available databases (e.g. Exome Aggregations Consortium (ExAC), Thousand Genomes, dbSNP) to ensure that no other homozygous loss of function variant had been reported in the candidate disease gene. We identified homozygous loss of function variants in five families in the following genes: AGBL2, SLC18A2, SMARCA1, UBQLN1, and CPLX1 (Tables 1A and S1; Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. Pedigrees, clinical and radiologic images of patients with homozygous LOF mutations.

Consanguinity between parents is indicated in each pedigree. A. Brain MRI of BAB4627 revealed severe cortical dysplasia, diffuse hypoplastic corpus callosum, dilated lateral ventricles, simplified gyral pattern, and dysmorphic basal ganglia. Note the similarity of the brain phenotype in BAB4627, with homozygous AGBL2 p. R583X variant, to tubulinopathy-related cortical dysplasia syndromes. B. BAB3407’s MRI presents cortical atrophy, thin and dysplastic corpus callosum. Patient image illustrates her severe dystonia. C. BAB4453 with homozygous stop gain (p.Q3X) in SMARCA1 represents severe cortical atrophy. Patient image underlines the coarse face, bushy eyebrows, facial hypertrichosis, and long eye lashes which resembles the facial dysmorphism in Coffin-Siris syndrome. D. A homozygous frameshift mutation (p.505fs) was detected in SNX14 in patient CGD-62463468; note the MRI shows severe cerebellar atrophy. For comparison an image of a patient (BAB5804) from a different family with homozygous SNX14:c.T2390G:p.L797R mutation is provided and which also revealed a coarse face in the patient. E. The MRI of BAB4807 with homozygous p.N126fs in UBQLN1 shows the dolichocephalic appearance of the head, dilated lateral ventricles and Arnold-Chiari malformation.

A homozygous nonsense variant (NM_024783:c.C1747T:p.R583X) in the AGBL2 gene was identified in patient BAB4627 with cerebral fronto-parieto-temporal atrophy, simplified gyral pattern; diffuse thinning of corpus callosum and seizures (Figures 6A and S4A). AGBL2 encodes a cytoplasmic carboxypeptidase involved in posttranslational modification (detyrosination) of α-tubulin (Sahab et al., 2011).

Patient BAB4453 presented with microcephaly, spasticity, and intellectual disability. He also had very similar dysmorphic features similar to those seen in Coffin-Siris syndrome (MIM# 135900) (Figure 6C). Family history was negative. He was found to have a hemizygous null variant in the SMARCA1 gene (NM_003069: c.C7T, p.Q3X) (Tables 1A and S1, Figure 6C), which encodes a member of the SWI/SNF family of proteins and is part of the ATP-dependent CECR2-containing remodeling factor (CERF) (Figure 6C) (Banting et al., 2005).

In a female proband (BAB4810) with intellectual disability, developmental delay, hypotonia, strabismus, dolichocephaly, simple and low-set ears, and early loss of teeth, and her brother (BAB4807) with intellectual disability and developmental delay, dilated lateral ventricles and Arnold-Chiari malformation on MRI but less pronounced dysmorphic features, we identified a novel frameshift mutation in the UBQLN1 gene (NM_013438: c.377delA, p.N126Mfs*) which segregated with the phenotype in 5 available family members (Tables 1A and S1, Figure 6). The encoded ubiquilin 1 protein and related ubiquitin-like family members are proposed to functionally link the ubiquitination machinery to the proteasome to facilitate in vivo protein degradation (Kleijnen et al., 2000).

We identified a homozygous nonsense mutation (NM_006651:c.G322T:p.E108X) in the CPLX1 gene in two female siblings, BAB6167 and BAB6168, who presented with malignant migrating epilepsy and cortical atrophy. CPLX1 encodes one of the “complexins” (complexin 1), soluble presynaptic proteins that modulate neurotransmitter release by binding the SNAP (soluble N-ethylmalemide-sensitive-factor attachment protein) receptor assembly (Chen et al., 2002; McMahon et al., 1995).

Patient BAB3407 with intellectual disability, dystonia, microcephaly, cortical atrophy, corpus callosum hypoplasia and seizures, was found to have a frameshift variant in SLC18A2 (NM_003054:c.705delC:p.G235fs) encoding the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) which regulates the release and metabolism of the monoamine neurotransmitters; this finding offers a potential avenue for experimental treatment of the associated disease with direct dopamine agonists (Tables 1 and S1, Figures 6B and S4B) (Ohara et al., 2013).

Genes involved in biological pathways associated with distinct phenotypes

We utilized the type of brain malformation in a given individual and an understanding of its underlying molecular pathogenesis in the prioritization of the potential candidate genes identified in this study. Among the top candidate genes found in this group is a homozygous missense variant (NM_004856: c.T755A, p.L252H) in KIF23 identified in siblings with severe microcephaly (BAB5333 and BAB5334). KIF23 encodes a kinesin family member localized at the interzone of the mitotic spindle (Mishima et al., 2004). This variant has been found only in this family amongst our ‘in-house generated’ 5000 exomes on Mendelian families and was the only shared homozygous variant by two affected siblings. Neither this particular variant or any homozygous LOF variant has been reported in the ExAC database.

TTI1 was identified in a family (HOU1832) with microcephaly and intellectual disability where a homozygous missense mutation (NM_014657: c.G2761A, p.D921N) segregated with the phenotype in 2 affected and 4 unaffected family members. The encoded protein is a component of the triple T complex which has been shown to play a role in PIKK signaling in brain development and functioning (Hurov et al., 2010). Another component of the triple T complex is encoded by TTI2, and this gene has been shown to be mutated in a large consanguineous family with microcephaly, severe cognitive impairment, skeletal anomalies, and facial dysmorphism (MIM#615541) (Langouet et al., 2013). In addition, patients BAB6569 and BAB6570 with severe ID, microcephaly, seizures and some autistic behavioral pattern were found to have a homozygous missense mutation in ACTL6B (NM_016188:exon10:c.G893A:p.R298Q), a component of brain-specific chromatin remodeling complexes containing the ATPases Brg1 (SMARCA4) and Brm (SMARCA2) (Figure 7) (Olave et al., 2002).

In order to further clarify the role of RNA processing factors in brain malformations, we screened our cohort for potentially pathogenic variants in genes whose encoded proteins were predicted to interact with VARS, CLP1, and other RNA cleavage and polyadenylation specific factors (Figure 7). We focused especially on families with phenotypes similar to those seen in association with potential pathogenic variants in the above genes, and identified a rare homozygous variant (NM_022830:exon7:c.G1411A:p.A471T) in the TUT1 gene in a female proband (BAB3415) with cortical atrophy, microcephaly, and cerebellar atrophy (Tables 1 and S1; Figure 7). TUT1 plays a role in post-transcriptional modification of miRNAs, primarily as a poly(A) polymerase, and is essential for cell proliferation (Knouf et al., 2013; Trippe et al., 2006).

DISCUSSION

We investigated 128 mostly consanguineous families with abnormal brain development or brain function as evidenced by brain imaging or manifested as developmental delay/intellectual disability (DD/ID). Exome sequencing, accompanied by an informatics pipeline and analyses tools, and followed by Sanger validation and segregation studies, enabled detection of rare variants of potential pathologic significance. In silico analyses of the genes for brain developmental expression, and interactome and pathway analysis of gene products, further prioritized variants potentially associated with the Mendelizing traits that were studied. The study of a large cohort of over 100 families, rather than a small number of larger families aided the discovery process.

Two similar large scale genomic studies have been published recently (Alazami et al., 2015; Najmabadi et al., 2011). Both studies consisted of mostly consanguineous families which presented with DD/ID, with or without structural brain malformations, and utilized homozygosity mapping in addition to next generation sequencing. Interestingly, none of the genes proposed as potential candidates in these two studies overlapped with those proposed herein. This may be attributed to the selection of different ethnic groups and thus accumulation of private variants which occurred in recent ancestral generations (Lupski et al., 2011). In addition, the majority of probands in our cohort have structural brain malformations (~ 80%) rather than non-specific ID or congenital developmental delay. Finally, the multitude of prospective novel candidate genes highlights the magnitude and complexity of the mechanisms involved in human nervous system development and maintenance.

Our findings converge on three cellular processes: brain development, RNA metabolism, and cytoskeletal organization. As anticipated, some genes are involved in more than one of these processes. Genes associated with primary microcephaly were often differentially expressed during development with highest expression during the early embryonic and fetal periods (ASPM, WDR62, MCPH1, STIL, KIF23, and TTI1). This is consistent with the well-established association between defective neurogenesis, loss of neuroprogenitor cells, and resultant decreased volume of the brain. Proposed candidates found in patients with structural brain malformations (e.g. VARS, PRUNE, and DHX37) showed marked enrichment in early embryonic or fetal stages. Genes associated with metabolic derangements of the brain were often most highly expressed in the postnatal period (ALDH7A1, NAGLU, GLDC). Interestingly, candidate genes associated with intellectual disability (ADSL, GRIA3, CSRB2BP, ASH2L, CELSR2, and ACTL6B) did not follow a recognizable pattern of differential expression between the prenatal and postnatal stages.

Our hypothesis that VARS may lead to microcephaly and cortical dysgenesis is in accordance with the emerging class of neurological disorders resulting from mutations in genes encoding various aminoacyl tRNA synthetases (Taft et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2014; Vester et al., 2013). Evidence emphasizing the importance of the genes involved in RNA metabolism in the developing human brain is not limited to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, as tRNA-splicing complex proteins (TSEN2, TSEN34, TSEN54, CLP1) have also been shown to be associated with both forebrain and hindbrain development (Budde et al., 2008; Cassandrini et al., 2010; Karaca et al., 2014; Schaffer et al., 2014). We identified two potential candidate genes which function as RNA helicases: DHX37 and HELZ. RNA helicases are involved in almost every RNA related process, including transcription, splicing, ribosome biogenesis, translation and degradation (Jankowsky and Fairman, 2007; Jankowsky et al., 2001). They have been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, spinal muscular atrophy, and Alzheimer disease; however, evidence is often circumstantial (Steimer and Klostermeier, 2012). Although not directly involved in RNA processing, in silico analysis suggested that PRUNE, in which disease-associated variant alleles were identified in four distinct families, is tightly connected to VARS, TUT1, CLP1, and to additional cleavage polyadenylation specific factors (Figure 7). We suggest that PRUNE has a potential role in the developing human brain in addition to its role in cancer cell metastasis and tumor aggressiveness, and may be added to the growing list of genes involved in both neurodevelopment and cancer, which includes ASPM, MCPH1 (Alsiary et al., 2014), the AKT genes (Cohen, 2013), and the FANC genes (Walden and Deans, 2014).

Identification of homozygous LOF variants in candidate genes relevant to and co-segregating with a given Mendelian trait often provides evidence supporting causality. The high frequency of consanguinity in the current study cohort (~ 80%) allowed for the identification of several homozygous stop gain and frameshift variants in novel candidate genes. These include AGBL2, encoding a protein with a role in posttranslational modification of α-tubulin; and SMARCA1, encoding a component of the SWI/SNF like chromatin remodeling complex. In addition, we identified homozygous loss of function alleles in three genes with proposed roles in synaptic transmission: SLC18A2, CPLX1, and SNX14. Abnormal expression of VMAT2, encoded by SLC18A2, has been proposed to contribute to vulnerability toward epilepsy-related psychiatric disorders and cognitive impairment (Jiang et al., 2013). Our finding complements the single report in the literature of a homozygous missense mutation in this gene and provides our patient possible direct route to treatment with dopamine agonists as described (Rilstone et al., 2013). The SNX14 gene, homozygously deleted almost in its entirety in BAB3498 and harboring a homozygous frameshift insertion in patient CGD-62463468, encodes a protein of the sorting nexin family, important in cell trafficking and signaling (Mas et al., 2014). While our work was in progress another group independently reported SNV mutations of this gene in association with intellectual disability, coarse face and hypoplasia of the cerebellum, specifically without microcephaly (Akizu et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2014). The microcephaly observed in BAB3498 may reflect a more severe phenotype associated with the larger homozygous deletion or possibly a yet unidentified modifier gene. Finally, a homozygous LOF allele was identified in UBQLN, which has been studied in Alzheimer disease due to its potential role in proteasome degradation and its interaction with PSEN1 and PSEN2 (Bertram et al., 2005; Bird, 2005; Stieren et al., 2011). The ubiquitin-proteasome system has recently been proposed to play a role in the pathogenesis of Down syndrome (Granese et al., 2013), and several members of this pathway have been implicated in intellectual disability (UBE2A, UBE3B, CRBN) (Basel-Vanagaite et al., 2012; Nascimento et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2013).

Although traditional classification divides brain malformations by temporal embryological processes, there have been suggestions that future classification may rely on dysfunctions of particular biological pathways (Barkovich et al., 2012; Guerrini and Dobyns, 2014). Thus, the type of brain malformation in a given individual and an understanding of its underlying molecular pathogenesis were utilized in the prioritization of the potential candidate genes, which would not have been possible in a cohort of non-syndromic intellectual disability and distinguishes our work from previous publications (Alazami et al., 2015; Najmabadi et al., 2011). This approach is underlined by many of our findings such as a homozygous AGBL2 truncating mutation in a severe cortical dysplasia family; and a KIF23 variant in a patient with primary microcephaly. KIF23 is predicted to interact with several genes previously associated with microcephaly (Figure 7).

Contrary to the widely held paradigm that a genetic syndrome is associated with a singular unifying molecular diagnosis, recent studies reported that in ~5% of patients with a molecular diagnosis the phenotype is attributed to mutations in two distinct disease loci (Yang et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014) (Posey et al., in press). We identified three families with blended phenotypes of two different variants affecting at least two different genes. These included SNX14 and RARS2 in a family (HOU2215) with severe microcephaly, severe ID, cerebellar hypoplasia, seizures and a relatively coarse face. SNX14 and RARS2 are in linkage disequilibrium - they lie in close proximity on chromosome 6 and are found in the same AOH region in these patients. Family HOU2231 had a complex phenotype of Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and unrelated elevated creatinine kinase. Systematic use of WES data revealed that both probands had a homozygous SNV in DHCR7 (MIM#270400) as well as a hemizygous CNV disrupting the DMD gene, explaining their complex clinical picture and illustrating the value of a non-targeted genomic analyses over a single locus genetic approach. In addition, patient BAB5481 was found to have both 15q11.2 deletion syndrome (MIM#615656) and a homozygous missense mutation in ASXL3. Although 15q11.2 microdeletion could explain developmental delay, seizures and intellectual disability; the patient also had severe microcephaly, diffuse cortical atrophy and gastroesophageal reflux which have been reported in patients with ASXL3 mutations (Bainbridge et al., 2013; Dinwiddie et al., 2013). To the best of our knowledge, all reported mutations of human ASXL3 gene are de novo heterozygous truncating mutations, whereas we identified a homozygous missense variant in our case from a consanguineous family.

In conclusion, our study emphasizes the efficiency of WES to detect genes with variants contributing to diseases that show Mendelian inheritance, demonstrates the ability to reliably identify homozygous and heterozygous CNVs in WES data, and highlights the utility of WES in solving complex phenotypes in patients with more than one molecular diagnosis. Our approach of sequencing 2–3 affected members from small families with apparent recessive inheritance, without prior homozygosity mapping, differentiates this study from classical studies of recessive pedigrees (Alazami et al., 2015; Najmabadi et al., 2011). We illustrate the utility of this approach and underscore the added benefits of solving blended phenotypes and observing the mutation load of individual cases within a given pedigree. The work provides insights into the biology of brain malformations as well as the genomics of neurogenetic diseases. In addition, close interactions of several candidates found in this cohort, particularly the ones seen in more than one family (CLP1, VARS, and PRUNE) with the RNA processing factors, stress the significance of these genes in the developing human brain (Karaca et al., 2014).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Whole exome sequencing analysis

We applied whole exome sequencing (WES) to selected family members through the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics research initiative. Genomic sequencing was performed by the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center following previously reported protocols (Lupski et al., 2013) and at Columbia University and Regeneron Genetics Center. Briefly, samples underwent whole exome capture using HGSC core design (52Mb, Roche NimbleGen, Inc), followed by sequencing on the HiSeq platform (Illumina, Inc) with an ~150x depth of coverage. Sequence data were aligned and mapped to the human genome reference sequence (hg19) using the Mercury in-house bioinformatics pipeline. Variants were called using the ATLAS (an integrative variant analysis pipeline optimized for variant discovery) and SAMtools (The Sequence Alignment/Map) suites and annotated with an in-house-developed annotation pipeline that uses ANNOVAR (Annotation of Genetic Variants) and additional tools and databases (Challis et al., 2012; Li et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). During the analyses of candidate variants/mutations, we used external publicly available databases such as the 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org) and other large-scale exome sequencing projects including the Exome variant server, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), our “in-house-generated” exome database (~5,000 individuals) at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) Human Genome Sequencing Center, and the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) Database (http://drupal.cscc.unc.edu/aric/). The Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), Cambridge, MA (URL: http://exac.broadinstitute.org) [Aug 2015] was used to search for homozygous loss of function variants in specific candidate genes. All experiments and analyses were performed according to previously described methods (Bainbridge et al., 2013).

Exome sequencing at the Regeneron Genetics Center (RGC) used similar protocols. Exome capture was performed using the Nimblegen VCRome design (Roche NimbleGen, Inc) and sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina, Inc). Mapping and alignment of sequence reads was performed through the RGC in-house developed cloud-based American Bobtail pipeline. Analysis of variants was performed using in-house developed bioinformatics pipelines.

AOH and CNV analysis

To examine absence of heterozygosity (AOH) regions surrounding candidate variants, we calculated B-allele frequency using whole exome sequencing data as a ratio of variants reads to total reads. These data were then processed using the Circular Binary Segmentation algorithm (CBS; (Olshen et al., 2004) to identify AOH regions.

To identify heterozygous CNVs we used both WES and genotype data from Illumina’s Human Exome (v1–2) arrays. Segmentation of log ratio signal from genotype arrays was performed using CBS (Olshen et al., 2004) whereas WES data were processed using CoNIFER software (Krumm et al., 2012; O’Roak et al., 2012).

The homozygous CNVs were detected using an in-house-developed algorithm implemented in the R programming language (R Core Team 2014, http://www.R-project.org). First, for every individual, we computed the total number of reads (TR) in each exon and normalized read depth values (RPKM, i.e. Reads Per Kilobase Per Million mapped reads) using the utility provided with CoNIFER (Krumm et al., 2012). Next, we identified homozygous deletions by analyzing exons for which the RPKM value was lower than 0.5 in less than 2% of individuals and RPKM values for remaining individuals were greater than 1. The second condition ensures that poorly captured regions are excluded from the analysis. RPKM thresholds were determined based on the analysis of distribution of RPKM values in previously identified and confirmed homozygous deletions. Finally, we filtered out homozygous CNVs which did not overlap with larger (>0.5Mb) AOH regions. RPKM values were also used for further visualization of detected deletions.

CNV detected by informatics analyses were further verified by array CGH and/or breakpoint junction sequencing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the family members and collaborators that participated in this study. This work was supported by the US National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHBLI) grant U54HG006542 to the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics, NINDS grant RO1 NS058529 to JRL and NHGRI 5U54HG003273 to RAG. TH is supported by the Medical Genetics Research Fellowship Program (T32 GM07526). WW is supported by Career Development Award K23NS078056 from NINDS. The authors would like to thank the Exome Aggregation Consortium and the groups that provided exome variant data for comparison. A full list of contributing groups can be found at http://exac.broadinstitute.org/about.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure summary: J.R.L. has stock ownership in 23 and Me and Lasergen and is a paid consultant for Regeneron. J.R.L. is a coinventor on multiple United States and European patents related to molecular diagnostics for inherited neuropathies, eye diseases and bacterial genomic fingerprinting. The Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine derives revenue from the chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) and clinical exome sequencing offered in the Medical Genetics Laboratory (http://www.bcm.edu/geneticlabs/). W.K.C. is a paid consultant for Regeneron and BioReference Laboratories. C.G.J and J.O. are employee of Regeneron Genetics Center. Other authors have no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.K. and T.H analyzed all the clinical and WES data. Z.C.A. and T. Gambin performed computational studies and applied bioinformatics tools and statistical analyses; S.E. performed in silico protein modelling; J.N.S., D.M.M., R.G. and J.O. generated WES pipelines; E.K., T.H. and J.R.L. wrote the manuscript, edited by all co-authors.

REFERENCES

- Akizu N, Cantagrel V, Zaki MS, Al-Gazali L, Wang X, Rosti RO, Dikoglu E, Gelot AB, Rosti B, Vaux KK, et al. Biallelic mutations in SNX14 cause a syndromic form of cerebellar atrophy and lysosome-autophagosome dysfunction. Nature genetics. 2015;47:528–534. doi: 10.1038/ng.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alazami AM, Patel N, Shamseldin HE, Anazi S, Al-Dosari MS, Alzahrani F, Hijazi H, Alshammari M, Aldahmesh MA, Salih MA, et al. Accelerating novel candidate gene discovery in neurogenetic disorders via whole-exome sequencing of prescreened multiplex consanguineous families. Cell reports. 2015;10:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsiary R, Bruning-Richardson A, Bond J, Morrison EE, Wilkinson N, Bell SM. Deregulation of microcephalin and ASPM expression are correlated with epithelial ovarian cancer progression. PloS one. 2014;9:e97059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Koonin EV. A novel family of predicted phosphoesterases includes Drosophila prune protein and bacterial RecJ exonuclease. Trends in biochemical sciences. 1998;23:17–19. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge MN, Hu H, Muzny DM, Musante L, Lupski JR, Graham BH, Chen W, Gripp KW, Jenny K, Wienker TF, et al. De novo truncating mutations in ASXL3 are associated with a novel clinical phenotype with similarities to Bohring-Opitz syndrome. Genome medicine. 2013;5:11. doi: 10.1186/gm415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banting GS, Barak O, Ames TM, Burnham AC, Kardel MD, Cooch NS, Davidson CE, Godbout R, McDermid HE, Shiekhattar R. CECR2, a protein involved in neurulation, forms a novel chromatin remodeling complex with SNF2L. Human molecular genetics. 2005;14:513–524. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkovich AJ, Guerrini R, Kuzniecky RI, Jackson GD, Dobyns WB. A developmental and genetic classification for malformations of cortical development: update 2012. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2012;135:1348–1369. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basel-Vanagaite L, Dallapiccola B, Ramirez-Solis R, Segref A, Thiele H, Edwards A, Arends MJ, Miro X, White JK, Desir J, et al. Deficiency for the ubiquitin ligase UBE3B in a blepharophimosis-ptosis-intellectual-disability syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2012;91:998–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram L, Hiltunen M, Parkinson M, Ingelsson M, Lange C, Ramasamy K, Mullin K, Menon R, Sampson AJ, Hsiao MY, et al. Family-based association between Alzheimer’s disease and variants in UBQLN1. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:884–894. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird TD. Genetic factors in Alzheimer’s disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:862–864. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleichert F, Baserga SJ. The long unwinding road of RNA helicases. Molecular cell. 2007;27:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde BS, Namavar Y, Barth PG, Poll-The BT, Nurnberg G, Becker C, van Ruissen F, Weterman MA, Fluiter K, te Beek ET, et al. tRNA splicing endonuclease mutations cause pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Nature genetics. 2008;40:1113–1118. doi: 10.1038/ng.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassandrini D, Biancheri R, Tessa A, Di Rocco M, Di Capua M, Bruno C, Denora PS, Sartori S, Rossi A, Nozza P, et al. Pontocerebellar hypoplasia: clinical, pathologic, and genetic studies. Neurology. 2010;75:1459–1464. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f88173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis D, Yu J, Evani US, Jackson AR, Paithankar S, Coarfa C, Milosavljevic A, Gibbs RA, Yu F. An integrative variant analysis suite for whole exome next-generation sequencing data. BMC bioinformatics. 2012;13:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Tomchick DR, Kovrigin E, Arac D, Machius M, Sudhof TC, Rizo J. Three-dimensional structure of the complexin/SNARE complex. Neuron. 2002;33:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MM., Jr The AKT genes and their roles in various disorders. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2013;161A:2931–2937. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo A, Garzia L, Andre A, Carotenuto P, Aglio V, Guardiola O, Arrigoni G, Cossu A, Palmieri G, Aravind L, et al. Prune cAMP phosphodiesterase binds nm23-H1 and promotes cancer metastasis. Cancer cell. 2004;5:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz J, Kressler D, Linder P. Unwinding RNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: DEAD-box proteins and related families. Trends in biochemical sciences. 1999;24:192–198. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BW, Kleefstra T, Yntema HG, Kroes T, Vulto-van Silfhout AT, Koolen DA, de Vries P, Gilissen C, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:1921–1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie DL, Soden SE, Saunders CJ, Miller NA, Farrow EG, Smith LD, Kingsmore SF. De novo frameshift mutation in ASXL3 in a patient with global developmental delay, microcephaly, and craniofacial anomalies. BMC medical genomics. 2013;6:32. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilissen C, Hehir-Kwa JY, Thung DT, van de Vorst M, van Bon BW, Willemsen MH, Kwint M, Janssen IM, Hoischen A, Schenck A, et al. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature. 2014;511:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granese B, Scala I, Spatuzza C, Valentino A, Coletta M, Vacca RA, De Luca P, Andria G. Validation of microarray data in human lymphoblasts shows a role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and NF-kB in the pathogenesis of Down syndrome. BMC medical genomics. 2013;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Dobyns WB. Malformations of cortical development: clinical features and genetic causes. The Lancet Neurology. 2014;13:710–726. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70040-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata H, Ogino K, Yamada K, Leacock S, Harvey RJ. Defective escape behavior in DEAH-box RNA helicase mutants improved by restoring glycine receptor expression. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:14638–14644. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1157-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurov KE, Cotta-Ramusino C, Elledge SJ. A genetic screen identifies the Triple T complex required for DNA damage signaling and ATM and ATR stability. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1939–1950. doi: 10.1101/gad.1934210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowsky E, Fairman ME. RNA helicases--one fold for many functions. Current opinion in structural biology. 2007;17:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowsky E, Gross CH, Shuman S, Pyle AM. Active disruption of an RNA-protein interaction by a DExH/D RNA helicase. Science. 2001;291:121–125. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G, Cao Q, Li J, Zhang Y, Liu X, Wang Z, Guo F, Chen Y, Chen Y, Chen G, et al. Altered expression of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 in epileptic patients and experimental rats. Synapse. 2013;67:415–426. doi: 10.1002/syn.21663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaca E, Weitzer S, Pehlivan D, Shiraishi H, Gogakos T, Hanada T, Jhangiani SN, Wiszniewski W, Withers M, Campbell IM, et al. Human CLP1 mutations alter tRNA biogenesis, affecting both peripheral and central nervous system function. Cell. 2014;157:636–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleijnen MF, Shih AH, Zhou P, Kumar S, Soccio RE, Kedersha NL, Gill G, Howley PM. The hPLIC proteins may provide a link between the ubiquitination machinery and the proteasome. Molecular cell. 2000;6:409–419. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouf EC, Wyman SK, Tewari M. The human TUT1 nucleotidyl transferase as a global regulator of microRNA abundance. PloS one. 2013;8:e69630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Hino S, Oue N, Asahara T, Zollo M, Yasui W, Kikuchi A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 and h-prune regulate cell migration by modulating focal adhesions. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:898–911. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.898-911.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm N, Sudmant PH, Ko A, O’Roak BJ, Malig M, Coe BP, Project NES, Quinlan AR, Nickerson DA, Eichler EE. Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome research. 2012;22:1525–1532. doi: 10.1101/gr.138115.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langouet M, Saadi A, Rieunier G, Moutton S, Siquier-Pernet K, Fernet M, Nitschke P, Munnich A, Stern MH, Chaouch M, et al. Mutation in TTI2 reveals a role for triple T complex in human brain development. Human mutation. 2013;34:1472–1476. doi: 10.1002/humu.22399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome Project Data Processing S. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR, Belmont JW, Boerwinkle E, Gibbs RA. Clan genomics and the complex architecture of human disease. Cell. 2011;147:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski JR, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Yang Y, Bainbridge MN, Jhangiani S, Buhay CJ, Kovar CL, Wang M, Hawes AC, Reid JG, et al. Exome sequencing resolves apparent incidental findings and reveals further complexity of SH3TC2 variant alleles causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Genome medicine. 2013;5:57. doi: 10.1186/gm461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas C, Norwood SJ, Bugarcic A, Kinna G, Leneva N, Kovtun O, Ghai R, Ona Yanez LE, Davis JL, Teasdale RD, et al. Structural basis for different phosphoinositide specificities of the PX domains of sorting nexins regulating G-protein signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:28554–28568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.595959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon HT, Missler M, Li C, Sudhof TC. Complexins: cytosolic proteins that regulate SNAP receptor function. Cell. 1995;83:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaa GM, Paciorkowski AR. Introduction: Brain malformations. American journal of medical genetics Part C. Seminars in medical genetics. 2014;166C:117–123. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima M, Pavicic V, Gruneberg U, Nigg EA, Glotzer M. Cell cycle regulation of central spindle assembly. Nature. 2004;430:908–913. doi: 10.1038/nature02767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najmabadi H, Hu H, Garshasbi M, Zemojtel T, Abedini SS, Chen W, Hosseini M, Behjati F, Haas S, Jamali P, et al. Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature. 2011;478:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento RM, Otto PA, de Brouwer AP, Vianna-Morgante AM. UBE2A, which encodes a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, is mutated in a novel X-linked mental retardation syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2006;79:549–555. doi: 10.1086/507047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Roak BJ, Vives L, Girirajan S, Karakoc E, Krumm N, Coe BP, Levy R, Ko A, Lee C, Smith JD, et al. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara A, Kasahara Y, Yamamoto H, Hata H, Kobayashi H, Numachi Y, Miyoshi I, Hall FS, Uhl GR, Ikeda K, et al. Exclusive expression of VMAT2 in noradrenergic neurons increases viability of homozygous VMAT2 knockout mice. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;432:526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olave I, Wang W, Xue Y, Kuo A, Crabtree GR. Identification of a polymorphic, neuron-specific chromatin remodeling complex. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2509–2517. doi: 10.1101/gad.992102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond A, Volorio S, Merla G, Al-Maghtheh M, Zuffardi O, Bulfone A, Ballabio A, Zollo M. Evidence for interaction between human PRUNE and nm23-H1 NDPKinase. Oncogene. 1999;18:7244–7252. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilstone JJ, Alkhater RA, Minassian BA. Brain dopamine-serotonin vesicular transport disease and its treatment. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:543–550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahab ZJ, Hall MD, Me Sung Y, Dakshanamurthy S, Ji Y, Kumar D, Byers SW. Tumor suppressor RARRES1 interacts with cytoplasmic carboxypeptidase AGBL2 to regulate the alpha-tubulin tyrosination cycle. Cancer research. 2011;71:1219–1228. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer AE, Eggens VR, Caglayan AO, Reuter MS, Scott E, Coufal NG, Silhavy JL, Xue Y, Kayserili H, Yasuno K, et al. CLP1 founder mutation links tRNA splicing and maturation to cerebellar development and neurodegeneration. Cell. 2014;157:651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimer L, Klostermeier D. RNA helicases in infection and disease. RNA biology. 2012;9:751–771. doi: 10.4161/rna.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieren ES, El Ayadi A, Xiao Y, Siller E, Landsverk ML, Oberhauser AF, Barral JM, Boehning D. Ubiquilin-1 is a molecular chaperone for the amyloid precursor protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:35689–35698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft RJ, Vanderver A, Leventer RJ, Damiani SA, Simons C, Grimmond SM, Miller D, Schmidt J, Lockhart PJ, Pope K, et al. Mutations in DARS cause hypomyelination with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and leg spasticity. American journal of human genetics. 2013;92:774–780. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammenkoski M, Koivula K, Cusanelli E, Zollo M, Steegborn C, Baykov AA, Lahti R. Human metastasis regulator protein H-prune is a short-chain exopolyphosphatase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9707–9713. doi: 10.1021/bi8010847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RW, Pyle A, Griffin H, Blakely EL, Duff J, He L, Smertenko T, Alston CL, Neeve VC, Best A, et al. Use of whole-exome sequencing to determine the genetic basis of multiple mitochondrial respiratory chain complex deficiencies. Jama. 2014;312:68–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AC, Williams H, Seto-Salvia N, Bacchelli C, Jenkins D, O’Sullivan M, Mengrelis K, Ishida M, Ocaka L, Chanudet E, et al. Mutations in SNX14 cause a distinctive autosomal-recessive cerebellar ataxia and intellectual disability syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2014;95:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trippe R, Guschina E, Hossbach M, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R, Benecke BJ. Identification, cloning, and functional analysis of the human U6 snRNA-specific terminal uridylyl transferase. Rna. 2006;12:1494–1504. doi: 10.1261/rna.87706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vester A, Velez-Ruiz G, McLaughlin HM, Program NCS, Lupski JR, Talbot K, Vance JM, Zuchner S, Roda RH, Fischbeck KH, et al. A loss-of-function variant in the human histidyl-tRNA synthetase (HARS) gene is neurotoxic in vivo. Human mutation. 2013;34:191–199. doi: 10.1002/humu.22210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden H, Deans AJ. The Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway: structural and functional insights into a complex disorder. Annu Rev Biophys. 2014;43:257–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-022737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Jiang X, Jaffrey SR. A mental retardation-linked nonsense mutation in cereblon is rescued by proteasome inhibition. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:29573–29585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.472092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Muzny DM, Reid JG, Bainbridge MN, Willis A, Ward PA, Braxton A, Beuten J, Xia F, Niu Z, et al. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:1502–1511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Muzny DM, Xia F, Niu Z, Person R, Ding Y, Ward P, Braxton A, Wang M, Buhay C, et al. Molecular findings among patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing. Jama. 2014;312:1870–1879. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.