Abstract

Motivation: Computational models of multicellular systems require solving systems of PDEs for release, uptake, decay and diffusion of multiple substrates in 3D, particularly when incorporating the impact of drugs, growth substrates and signaling factors on cell receptors and subcellular systems biology.

Results: We introduce BioFVM, a diffusive transport solver tailored to biological problems. BioFVM can simulate release and uptake of many substrates by cell and bulk sources, diffusion and decay in large 3D domains. It has been parallelized with OpenMP, allowing efficient simulations on desktop workstations or single supercomputer nodes. The code is stable even for large time steps, with linear computational cost scalings. Solutions are first-order accurate in time and second-order accurate in space. The code can be run by itself or as part of a larger simulator.

Availability and implementation: BioFVM is written in C ++ with parallelization in OpenMP. It is maintained and available for download at http://BioFVM.MathCancer.org and http://BioFVM.sf.net under the Apache License (v2.0).

Contact: paul.macklin@usc.edu.

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Mathematical modeling of many biological systems requires solving for secretion, diffusion, uptake and decay of multiple substrates in three dimensions. Cells change phenotype (division rate, metabolism, secretions, etc.) in response to their microenvironment; the spatial distribution of cells (and their uptake and secretion of substrates) alters the substrates’ distribution, affecting later cell behavior (Lowengrub et al., 2010). BioFVM solves PDEs driven by such problems, of the form

with zero flux conditions on . Here, Ω is the computational domain with boundary is the vector of substrate densities, are the substrate saturation densities, are the diffusion coefficients, are the decay rates, and are the supply and uptake rates (may vary throughout the domain), is a collection of cells centered at with volume Wk, supply and uptake rates and and saturation densities . is defined by inside cell k and otherwise. All products of vectors are element-wise.

While most multicellular models [e.g. Morpheus (Starruß et al., 2014), Chaste (Mirams et al., 2013)] include diffusion solvers, they generally are not designed to scale well to large 3D domains with more than a few substrates. Most are not designed for multithreaded parallelization on multicore desktops. The solvers tend to use explicit time steppings (require strict stability restrictions on ) or implicit time steppings (stable but require inverting large matrix systems). Those that invert large linear systems often have large dependencies that complicate cross-platform use.

BioFVM implements simple methods that can readily be parallelized by OpenMP. It can efficiently and accurately simulate systems of 5–10 or more diffusing substrates on 1–10 million or more voxels, with desktop workstations or single compute nodes. The code is first-order accurate in time and second-order accurate in space. Its performance scales linearly in the number of substrates (it takes 2.6× longer to increase from 1 to 10 substrates), the number of voxels and the number of cells. The code is stable; it often achieves good accuracy with to 0.1 min.

2 Method and implementation

We use a first-order, implicit (and stable) operator splitting, allowing us to create separate, optimized solvers for the diffusion-decay, cell-based source/sinks and bulk source/sinks (Marchuk, 1990). We solve the diffusion-decay terms using the finite volume method (Eymard et al., 2000), further accelerated by an additional first-order splitting into separate solutions in the x-, y- and z-directions via the locally one-dimensional method (LOD) (Marchuk, 1990; Yanenko, 1971). For each dimension, we solve the resulting tridiagonal linear systems with the Thomas algorithm (Thomas, 1949). We use OpenMP where loops can be parallelized (e.g. many instances of the Thomas solver when solving x-diffusion across multiple strips of domain). Other optimizations include storing pre-computations and overloading vector operations. The C ++ implementation is described in further detail in the supplementary materials.

3 Examples

3.1 Oxygen and VEGF diffusion in a large tissue

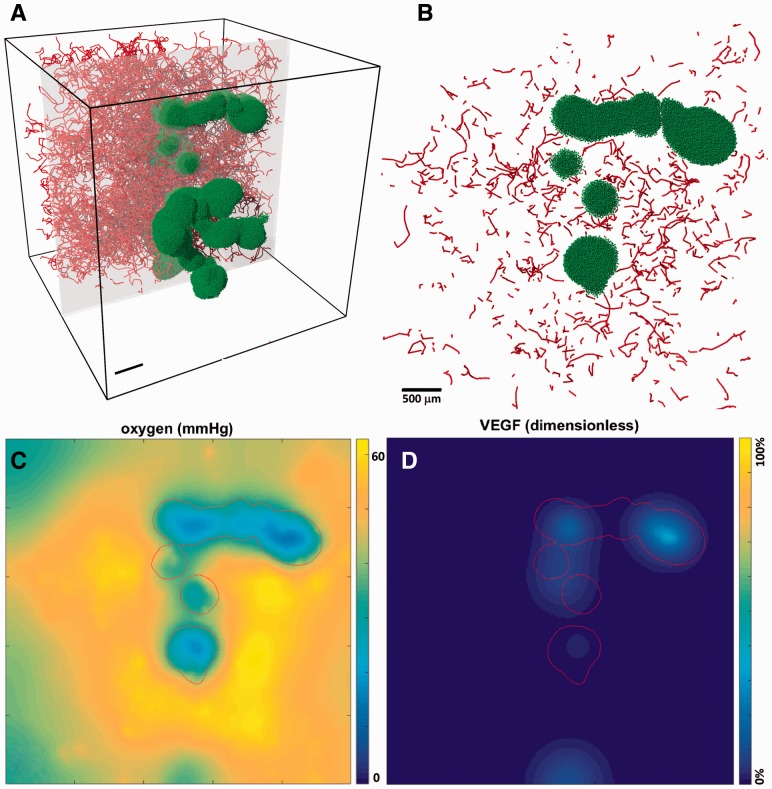

In Figure 1, we simulated 1 hour of diffusive transport in 125 mm3 of vascularized tissue (red curves, panel A) with a large irregular tumor (green cells, panel A) at 20 μm resolution (15 625 000 voxels) and min. Oxygen is released by the vessels (a series of cell-centered sources), diffuses through the tissue and is consumed by tumor cells. For technical illustration, tumor cells release VEGF where mmHg, which diffuses through the domain. Further biology, parameter values and references are discussed in the supplementary materials. In panel A, the vasculature is rendered up to the gray clipping plane for clearer illustration. Panel B shows the tumor cells and vessels in the gray clipping plane. Panels C–D shows the concentration of oxygen and VEGF in this plane. The red contour marks the tumor boundary. This simulation—with 2.8 million cell source/sink terms—required minutes on a quad-core desktop computer (Intel i7 4790, 3.60 GHz, 16 GB of memory); similar problems on 1 million voxels require 5–10 min.

Fig. 1.

Simulation of oxygen and VEGF diffusion in a highly vascularized tissue with a multifocal tumor lesion; vasculature is rendered up to the gray clipping plane (A). Vessels and tumor cells in the gray clipping plane (B). Oxygen distribution in (C) shows significant hypoxia (blue areas, pO2 < 15 mmHg) within the tumor (red outline). Hypoxic tumor cells release VEGF to stimulate further vascularization (D) (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

3.2 Convergence testing

Tests for several 1D and 3D problems showed first-order accuracy in time, second-order accuracy in space and stability even for large time steps. Using min gave reasonable accuracy for most problems. The convergence tests are fully detailed in the supplementary materials.

3.3 Performance testing

We tested diffusion of to 128 substrates with (typical magnitude for cancer biology) in a 1 mm3 domain at 10 resolution (1 million voxels) with min. Computational cost (wall time for 4 min of diffusion) scaled linearly with N; increasing from 1 to 10 substrates increased computational cost by . In other tests, computational cost scaled linearly with the number of voxels (domain size) and the number of cells. Full results are in the supplementary materials.

4 Obtaining software and licensing

BioFVM is available from BioFVM.MathCancer.org and BioFVM.sf.net under the Apache License (v2.0). A tutorial on using the code is included with the BioFVM download, along with several examples.

5 Discussion

BioFVM can efficiently and accurately simulate several diffusing substrates in large 3D domains, with both bulk and cell-based source and uptake terms. While it can run on its own (with minimal software dependencies), it is well-suited for inclusion in larger modeling packages. Beyond simulating the transport of drugs and growth substrates, BioFVM’s ability to simulate dozens of compounds should make 3D simulations of multicellular secretomics and multiscale cell responses feasible. In future releases, we plan to add upwinded advective solvers, more adaptive time stepping for cell-based source/sink terms and support for general Voronoi meshes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank David B. Agus and the USC Center for Applied Molecular Medicine for generous institutional support.

Funding

Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (5U54CA143907, 1R01CA180149).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Eymard R. et al. (2000). Finite volume methods. In Solution of Equation in Rn (Part 3), Techniques of Scientific Computing (Part 3) Handbook of Numerical Analysis, vol. 7 Elsevier, pp. 713–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Lowengrub J. et al. (2010) Nonlinear modeling of cancer: Bridging the gap between cells and tumors. Nonlinearity, 23, R1–R91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchuk G. (1990). Splitting and alternating direction methods. volume 1 of Handbook of Numerical Analysis, Elsevier, pp. 197–462. [Google Scholar]

- Mirams G.R. et al. (2013) Chaste: An open source c ++ library for computational physiology and biology. PLoS Comput. Biol., 9, e1002970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starruß J. et al. (2014) Morpheus: a user-friendly modeling environment for multiscale and multicellular systems biology. Bioinformatics, 30, 1331–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas L.H. (1949). Elliptic problems in linear difference equations over a network In: Watson Sci. Comput. Lab Report. Columbia University, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Yanenko N. (1971). Simple schemes in fractional steps for the integration of parabolic equations In: Holt M. (ed.) The Method of Fractional Steps. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.