Abstract

This article reviews 95 publications (based on 21 independent samples) that have examined children at family risk of reading disorders. We report that children at family risk of dyslexia experience delayed language development as infants and toddlers. In the preschool period, they have significant difficulties in phonological processes as well as with broader language skills and in acquiring the foundations of decoding skill (letter knowledge, phonological awareness and rapid automatized naming [RAN]). Findings are mixed with regard to auditory and visual perception: they do not appear subject to slow motor development, but lack of control for comorbidities confounds interpretation. Longitudinal studies of outcomes show that children at family risk who go on to fulfil criteria for dyslexia have more severe impairments in preschool language than those who are defined as normal readers, but the latter group do less well than controls. Similarly at school age, family risk of dyslexia is associated with significantly poor phonological awareness and literacy skills. Although there is no strong evidence that children at family risk are brought up in an environment that differs significantly from that of controls, their parents tend to have lower educational levels and read less frequently to themselves. Together, the findings suggest that a phonological processing deficit can be conceptualized as an endophenotype of dyslexia that increases the continuous risk of reading difficulties; in turn its impact may be moderated by protective factors.

Keywords: dyslexia, endophenotype, family risk of dyslexia, language impairment, multiple risk factors

Literacy skills are the key to educational attainments and these in turn promote access to career opportunities and employment. However, even in developed educational systems, a substantial number of children fail to learn to read to age-expected levels. A specific barrier to progress is difficulty in decoding print—the first step to reading with understanding; such difficulties with the development of decoding skills are referred to as dyslexia. Dyslexia is a common condition, thought to affect some 3–7% of the English-speaking population, with more boys than girls affected (Rutter et al., 2004).

The definition of dyslexia has undergone many changes over the years, not least because there are no clear diagnostic criteria (Rose, 2009). Rather the distribution of reading skills in the population is continuous and the “cut-offs” used to define a person as “dyslexic” are arbitrary (e.g., Pennington, 2006). Moreover, dyslexia tends to co-occur with other disorders, including specific language impairment (SLI; e.g., Bishop & Snowling, 2004; McArthur, Hogben, Edwards, Heath, & Mengler, 2000; Melby-Lervåg & Lervåg, 2012), speech sound disorder (e.g., Pennington & Bishop, 2009), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; e.g., McGrath et al., 2011; Willcutt & Pennington, 2000). Consistent with this, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition, DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) groups together reading disorders (dyslexia), mathematical disorders, and disorders of written expression under a single overarching diagnosis of Specific Learning Disorder within the broader category of Neurodevelopmental Disorders.

It has been known for many years that dyslexia, like other neurodevelopmental disorders, runs in families and studies of large twin samples demonstrate that reading and the phonological skills that underpin it are highly heritable (Olson, 2011, for a review). However, the genetic mechanisms involved are complex and depend on the combined influence of many genes of small effect and gene—gene interactions (e.g., Newbury, Monaco, & Paracchini, 2014). In addition, “generalist” genes, thought to code for general cognitive abilities, contribute to the etiology of dyslexia (Plomin & Kovas, 2005). Arguably, progress in the neurobiology of dyslexia requires a refined understanding of the phenotype of dyslexia at the cognitive level which clarifies its key developmental features and its relationship to other disorders. The current review contributes to that understanding.

In this article we provide a comprehensive review of studies that, assuming the heritability of dyslexia, have compared children at family risk (FR) of dyslexia with children with no such risk (low risk, control) on behavioral measures of perception, language, and cognition. Such studies have typically been designed to test out causal hypotheses regarding the developmental course of dyslexia. The methodology has distinct advantages over the more standard case-control approach; first it is free of clinical bias because children are recruited before they enter formal reading instruction; second, it allows us to disentangle possible causes of dyslexia from its consequences; third, and arguably most importantly, it is the only methodology that can allow the identification of risk factors in the preschool period, together with likely protective factors. Although such longitudinal prediction can also be conducted using a general population sample, the high-risk method is much more efficient; for instance, in a general population sample with a rate of dyslexia at 10%, one would need to follow 500 children to obtain a sample of 50 dyslexics; in a high-risk sample with a rate of dyslexia around 30%, a sample of 150 will yield the same number of affected cases.

The current review is organized around the main questions that family risk studies have addressed: the prevalence of dyslexia in children with a first-degree-affected relative, the nature of the home literacy environment in dyslexic families and the possible causes of dyslexia. We use the findings to address two further important issues for theory and practice. First, the relationship between dyslexia (diagnosed when written language skills fail to develop adequately) and language impairment (diagnosed when spoken language skills fail to develop adequately; Bishop & Snowling, 2004; Ramus et al., 2012). Second, evidence regarding what works to prevent or ameliorate dyslexia in children at high risk of the disorder. We begin with a short review of the research that guided our hypotheses before outlining the methodology for the current study and the constructs that were evaluated in the meta-analysis.

Individual Differences in Reading Development

To consider the nature and developmental course of dyslexia, it is important to highlight the resource demands of learning to read. Universally, reading is a process of mapping between the visual symbols on the page (orthography) and the spoken language. However, the nature of the symbols and the units of spoken language to which they connect differ across languages (e.g., Ziegler & Goswami, 2005). In an alphabetic language such as English, the foundation of literacy is a system of mappings between letters and phonemes (the smallest speech sounds of words) and a challenge for the child is to abstract the mapping principle (Byrne, 1998). In contrast, Chinese is nonalphabetic; the orthographic symbols are characters comprising semantic and phonetic radicals that correspond to morphemes (units of meaning). The semantic radical provides information about the meaning and the phonetic radical provides a cue to the pronunciation of the word (Shu & Anderson, 1997).

Orthographies also differ in their “transparency”—that is the regularity of the mappings between symbols and sounds. Among European languages, English has the most inconsistent writing system, embodying many exceptions; German and Dutch have relatively few inconsistencies and Finnish is the most consistent. In general, it has been shown that regular languages pose fewer challenges for the beginning learner than irregular languages (Seymour, 2005) but arguably, this is a simplistic view. Languages also differ in the way in which they convey the grammar in writing and differences in morphological structure may moderate the ease of learning (Seidenberg, 2011).

Nonetheless, it is clear that the specific demands of learning to read will differ across languages. Irrespective of this, the child needs to learn the symbol set and how that set maps to the language and this requires explicit awareness of the structure of the language. Once the basic mappings have been established, reading practice (“print exposure”) is required to achieve reading fluency.

Among alphabetic languages it is well established that the predictors of individual differences in decoding (the skill that is impaired in dyslexia) are the same regardless of the transparency of the language: these are, letter knowledge, phoneme awareness, and rapid automatized naming (Caravolas et al., 2012; Ziegler et al., 2010a). However, reading development proceeds faster in the more transparent orthographies than in opaque orthographies (Caravolas et al., 2013). The process of learning is more protracted in languages that have large symbol sets and in nonalphabetic languages where mappings are to meaning rather than sound (Nag, Caravolas, & Snowling, 2011). Nonetheless, a similar set of skills appear to predict progress in these languages—namely symbol knowledge, metalinguistic awareness, and rapid automatized naming; the corollary is that deficits in these skills compromise decoding in dyslexia.

The Role of Environmental Factors

The majority of research on dyslexia has focused on its proximal cognitive causes; however, within a developmental framework it is important also to consider distal risk factors. Given the differences between orthographies, one extrinsic factor which affects the rate of reading development is the language of learning. Thus, it might be expected that the prevalence of dyslexia will depend on the transparency of the language; indeed it has sometimes been speculated that the difficulty of the English language could be a cause of dyslexia. However, data from more regular orthographies provide little evidence in support of this contention (for Dutch: Blomert, 2005; for German: Fischbach et al., 2013).

Social-demographic factors can also affect reading attainments. For example, higher rates of reading difficulty have been reported in inner-city samples than in rural areas (except in developing countries where the opposite trend is seen) and it is well-known that there is a social gradient in reading attainment such that reading is poorer in disadvantaged groups (e.g., Rutter & Maughan, 2005). Among the factors that could account for demographic variation are differences in parental education level (Phillips & Lonigan, 2005, for a review) or in quality of schooling, although whether such differences are truly environmental, rather than reflecting genetic factors, is a moot point (Friend, DeFries, & Olson, 2008). The quality of the home literacy environment (e.g., Frijters, Barron, & Brunello, 2000) is one factor that likely reflects the correlated effects of genes and environment (ge correlation). Moreover, evidence suggests that the home literacy environment may at least partially mediate the influence of socioeconomic status (SES) on children’s literacy outcomes (e.g., Chazan-Cohen et al., 2009).

Home literacy environment is defined by a range of factors concerning parents’ and children’s attitudes and dispositions toward reading, including how long parents spend reading with their children and parents’ own reading behavior. An important component is “shared book reading” that has a significant impact on children’s oral language development (Bus, van Ijzendoorn, & Pellegrini, 1995). In addition, direct teaching of literacy concepts is observed in some families and this strengthens the foundational skills for reading. More important, differences in parental attitude to literacy appear to affect how children’s reading skills develop: while direct instructional practices focusing on print concepts facilitate the early development of decoding skills, shared language experiences around books have a greater impact on reading comprehension (Senechal & LeFevre, 2001). An important question that arises from this research is how the literacy environment in families in which there is a parent (or indeed a child) with dyslexia differs from that in a family where family members are free of literacy problems. Family risk studies provide the opportunity to do this and to track possible changes in both child- and parental attitudes as reading develops over time.

Perceptual and Cognitive Deficits in Dyslexia

A major thrust of research on dyslexia has been to specify the underlying deficits that are candidate causes of the condition. Such impairments (that may be cognitive and/or have their origins in basic perceptual processes) mediate the impact of heritable, brain-based differences on behavior (Morton & Frith, 1995; Pennington, 2002; Ramus, 2003, 2004).

Within this approach, the predominant view for many years was that dyslexia could be traced to deficits within the phonological system of language (Melby-Lervåg, Lyster, & Hulme, 2012; Vellutino, Fletcher, Snowling, & Scanlon, 2004). As we have seen, phonological skills are critical foundations for learning to read in alphabetic systems. More generally, phonological deficits have been reported to characterize dyslexia in logographic Chinese (Hanley, 2005; Ho, Chan, Lee, Tsang, & Luan, 2004; Ho, Chan, Tsang, & Lee, 2002) and poor readers of alphasyllabic scripts (Nag & Snowling, 2011). However, a problem in assessing the causal status of phonological deficits is that performance on phonological tasks (such as phoneme awareness and nonword repetition) is influenced by reading skill (Morais & Kolinsky, 2005 for a review). It follows that deficits in these processes could be correlates (rather than causes) of poor reading. An advantage of family risk studies is that phonological processing can be measured before the onset of literacy. As we shall see, all family risk studies have assessed the development of phonological skills.

At a more fine-grained level, research has pursued the causes of the phonological deficits in dyslexia. In now classic work, Tallal (1980) proposed that dyslexia is caused by a problem with the rapid temporal processing of auditory information needed for the perception of speech sounds, leading to a cascade of difficulty from auditory processing through speech perception to phonological skills. Family risk studies are well placed to test such causal chains from the early stages of language development. Accordingly many of these studies draw on research suggesting deficits in speech perception in dyslexia (e.g., Adlard & Hazan, 1998; Nittrouer, 1999; Serniclaes, Van Heghe, Mousty, Carré, & Sprenger-Charolles, 2004; Ziegler, Pech-Georgel, George, & Lorenzi, 2009) or in basic auditory processing (Hämäläinen, Salminen, & Leppänen, 2012 for a review).

A separate line of investigation has focused on possible causes of difficulties with the letter-by-letter structure of words (orthographic deficits) in dyslexia. One theory is that spatial coding deficits affect ocular motor control (Boden & Giaschi, 2007; Kevan & Pammer, 2008; Vidyasagar & Pammer, 2010). Alternatively, problems in the system of visual attention could affect the left-to-right extraction of orthographic information critical for parsing letter strings before decoding (Facoetti, Paganoni, Turatto, Marzola, & Mascetti, 2000; Valdois, Bosse, & Tainturier, 2004). In addition, there are modality—general theories that aim not to explain particular features of dyslexia but rather seek overarching explanations (e.g., Ahissar, Lubin, Putter-Katz, & Bani, 2006; Nicolson & Fawcett, 1990; Vicari, Marotta, Menghini, Molinari, & Petrosini, 2003). Whereas such theories may hold promise for understanding how dyslexia relates to other co-occurring disorders (comorbidity, e.g., Rochelle & Talcott, 2006) they do not explain why dyslexia can and sometimes does occur in the absence of any other cognitive deficits.

Nevertheless, as a long history of the search for subtypes of dyslexia attests, these causal hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and it is important to recognize that dyslexia is a heterogeneous condition (e.g., Ramus et al., 2003). As Pennington (2006) has argued, the etiology of complex disorders like dyslexia is multifactorial and involves the interactions of risk and protective factors. Longitudinal studies of children at family risk of dyslexia that follow children from early childhood to formal schooling can reveal the risk factors associated with a dyslexia outcome. In addition, because dyslexia is a dimensional disorder, the study of unaffected relatives can be informative in highlighting protective or compensatory factors that mitigate familial risks. Such risks (that could be biological processes or cognitive impairments) can be described as “endophenotypes” (Skuse, 2001).

According to Bearden and Freimer (2006), an endophenotype is a “marker” that is associated with the disorder in the population and expressed at a higher rate in unaffected relatives of probands than in the general population. Put another way, it is intermediate between the genotype and the phenotype and, importantly, the impact of such processes can be moderated or compensated for by areas of skill or through interventions. This particular characteristic of an endophenotype deserves mention in relation to comorbidities. When two neurodevelopmental disorders frequently co-occur it is probable that they have endophenotypes in common (Thapar & Rutter, 2015, for a review). Prospective family risk studies can identify putative endophenotypes of dyslexia (or subclinical features) that mark the presence of co-occurring disorders For example, findings of family risk studies can elucidate relationships between difficulties with oral language observed in preschool and later written language disorders, in short, the comorbidity between dyslexia, specific language impairment (Bishop & Snowling, 2004; Pennington & Bishop, 2009, for reviews).

Study Rationale and Hypotheses

Although the discussion above highlights the importance of taking a longitudinal perspective to understanding dyslexia, current knowledge of dyslexia draws mainly on cross-sectional studies involving the comparison of individuals with dyslexia and controls at one specific point in time. Such evidence cannot distinguish adequately between causal and noncausal reasons for associations. Following the pioneering work of Scarborough (1989, 1990), who followed a group of 2-year-old English-speaking children deemed to be at high-risk of dyslexia because of an affected parent, many prospective studies of children at family risk of dyslexia have begun in recent years. At the time of writing, 21 independent studies have been completed, resulting in 95 behavioral publications that are the focus of this review. In addition, our review found 23 descriptive studies using neurophysiological measures that are listed in Supplemental Material Table S1 (in the online supplement file). We used the findings of the behavioral studies to test the hypotheses that follow.

Hypothesis 1: The prevalence of dyslexia in children at family risk. We predicted that dyslexia would be more common in at-risk than control families (Hypothesis 1a) and more prevalent in English because it has an opaque orthography than in other European languages (Hypothesis 1b); in addition, given the large character set, we expected a high prevalence in Chinese. Irrespective of orthography, because dyslexia is a dimensional disorder with no clear boundaries, we predicted that prevalence would depend upon the cut-off used for “diagnosis” (Hypothesis 1c).

Hypothesis 2: The home and literacy environment of children at family risk of dyslexia. Because of the influence of genetic factors and the environments correlated with them, we hypothesized that the home literacy environment would differ between families in which there is a history of reading difficulty from that in families where parents are free of such problems (Hypothesis 2a). We did not specify the ways in which these differences would be manifest but we anticipated that parents with dyslexia would read less for pleasure than controls (Hypothesis 2b). If the home literacy environment influences children’s reading attainment, we predicted that parental literacy skills (a proxy for gene—environment correlation; van Bergen, van der Leij, & de Jong, 2014) would account for independent variance in children’s reading outcomes (Hypothesis 2c).

Hypothesis 3: Endophenotypes of dyslexia. Although endophenotypes can take many forms, we are concerned here with the perceptual and cognitive deficits that are observed among children at family risk of dyslexia. These can be expected to be present in the preschool years before dyslexia is diagnosed (where they can be construed as cognitive risk factors; Hypothesis 3a). Based on the overlap between dyslexia and language impairment (Bishop & Snowling, 2004; Ramus et al., 2012), we expected that delays and difficulties with speech and language development would be common (Hypothesis 3b). More specifically, for alphabetic languages we predicted that three of the skills considered foundational for literacy (letter knowledge, phoneme awareness, and rapid automatized naming [RAN]; Caravolas et al., 2013) would show developmental delay in the preschool period (Hypothesis 3c) and deficits in each would characterize dyslexia in the school years (Hypothesis 3d). Given the known continuity of risk for dyslexia among family members (Pennington & Lefly, 2001), we predicted that unaffected children at family risk of dyslexia would also have poor literacy skills relative to controls but not severe enough to warrant a diagnosis of dyslexia (Hypothesis 3e) and deficits/endophenotypes should be observed in unaffected children but to a milder degree (Hypothesis 3f). Finally, we aimed to evaluate the causal status of basic deficits in speech perception, visual, and auditory processing, attention and motor skills as additional risk factors (Hypothesis 3a).

Hypothesis 4: Predictive relationships between early cognitive abilities and later reading. Reading builds upon spoken language and there are similar heritable influences on both reading comprehension and language comprehension (e.g., Keenan, Betjemann, Wadsworth, DeFries, & Olson, 2006). In this light, we predicted that preschool measures of oral language would predict later reading outcomes, particularly reading comprehension (Hypothesis 4a). Based on previous findings (e.g., Caravolas et al., 2013) we also predicted that, for alphabetic languages, there would be three predictors of decoding skills and hence dyslexia: phonological awareness, symbol knowledge (letters in alphabetic languages) and RAN (Hypothesis 4b).

Hypothesis 5: Interventions for dyslexia. Arguably the ultimate aim of research on dyslexia is to identify effective interventions that will ameliorate its impact on educational attainments. In addition, training studies are important theoretically as tests of causal hypotheses (Snowling & Hulme, 2011). We expected that interventions incorporating training in letter knowledge and phoneme awareness would improve decoding skills in children at family risk of dyslexia (Hypothesis 5a). However, we did not expect such interventions to impact reading comprehension beyond gains in decoding unless they incorporated training in broader oral language skills (e.g., vocabulary training; Hypothesis 5b).

Table 1. Hypotheses for the Review.

| Hypotheses guiding the review | Predictions |

|---|---|

| The prevalence of dyslexia in children at family risk | |

| Hypothesis 1a | Dyslexia is more common in at-risk than control families. |

| Hypothesis 1b | Dyslexia is more prevalent in English than in other European (regular) languages. |

| Hypothesis 1c | The prevalence rates for dyslexia depend upon the cut-off used for “diagnosis.” |

| The home and literacy environment of children at family risk of dyslexia | |

| Hypothesis 2a | The home literacy environment will differ between families in which there is a history of reading difficulty from that in families where both parents are free of problems. |

| Hypothesis 2b | Parents with dyslexia will read less for pleasure than controls. |

| Hypothesis 2c | Parental literacy skills will account for independent variance in children’s reading outcomes. |

| Endophenotypes of dyslexia | |

| Hypothesis 3a | Cognitive and perceptual risk factors that are putative endophenotypes should be present in the preschool years before dyslexia is diagnosed. |

| Hypothesis 3b | Children at family risk of dyslexia will show delayed speech/language development. |

| Hypothesis 3c | The development of three critical foundations for decoding, viz phonological awareness, symbol knowledge (letters in alphabetic languages) and rapid naming (RAN) will be delayed in children at family risk of dyslexia in preschool. |

| Hypothesis 3d | Deficits in phonological awareness, symbol knowledge and RAN will characterize dyslexia in the school years. |

| Hypothesis 3e | Unaffected children at family risk of dyslexia will have poorer literacy skills than controls. |

| Hypothesis 3f | Endophenotypes of dyslexia will be observed in unaffected children but to a milder degree than in affected children. |

| The predictive relationships between early cognitive and later reading skills | |

| Hypothesis 4a | Oral language skills will predict literacy outcomes in children at family risk of dyslexia. |

| Hypothesis 4b | Three critical foundations for decoding, viz phonological awareness, symbol knowledge (letters in alphabetic languages) and rapid naming (RAN) will be predictors of decoding in children at family risk of dyslexia. |

| Interventions for dyslexia | |

| Hypothesis 5a | Training in letter knowledge and phoneme awareness will ameliorate decoding difficulties. |

| Hypothesis 5b | Training in vocabulary and broader language skills will improve reading comprehension. |

Structure of the Current Review

Table 1 presents a summary of the hypotheses that guided the review. First, to assess Hypotheses 1(a–c) we summarize data from studies examining prevalence of dyslexia in family risk studies; second, to assess Hypotheses 2 (a and b), we use data on the home and literacy environment and to assess Hypothesis 2c we use data examining parental skills as predictors of outcome. To assess evidence for endophenotypes (Hypotheses 3 a–f), we adopt a developmental perspective, presenting evidence from different developmental stages from infancy/toddlerhood to secondary school. Here we will discuss findings of studies that have compared children at family risk of dyslexia with controls (at low risk because they do not have a family history). These studies can tell us about the risk factors associated with familial dyslexia (Hypotheses 3a–d). We will also include findings from retrospective analyses comparing the cognitive profiles of children at family risk who have later been classified as dyslexic or not, and controls. In addition to reinforcing the conclusions above, these studies can assess Hypothesis 3e and elucidate endophenotypes of dyslexia (Hypothesis 3f). Next we will examine the findings of longitudinal studies that have incorporated multiple regression and related statistical techniques to provide additional evidence regarding the predictors of dyslexia (Hypotheses 4a and b) and finally evaluate the evidence for effective interventions (Hypothesis 5a and b).

Method

The review was designed and is reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (www.prisma-statement.org). PRISMA is a consensus statement developed by an international group of researchers in health care for the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. When there is a sufficient number of studies (two or more), we will do a meta-analysis by calculating a mean effect size. If a summary effect is not possible, we will do a systematic review and report effect sizes for individual studies.

Literature Search, Inclusion Criteria, and Coding

Literature search

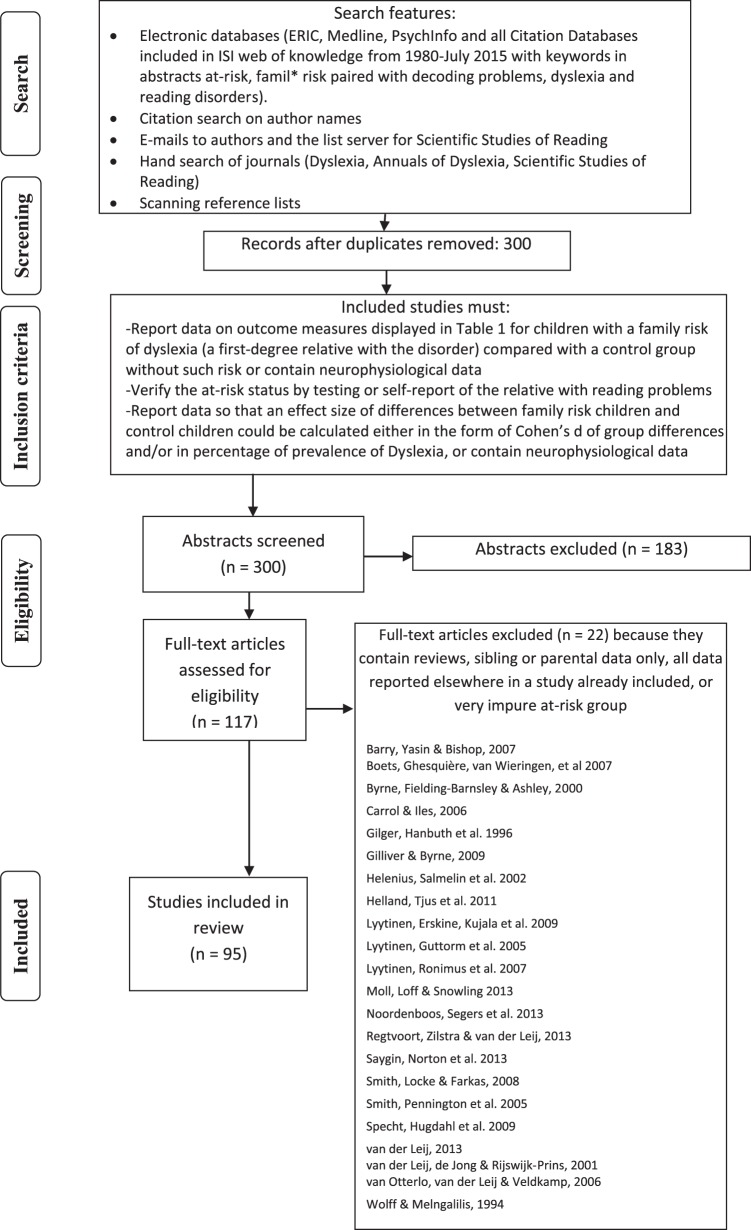

Details concerning the literature search, criteria for inclusion and flow of studies are shown in Figure 1. The literature search consisted of the following components: Electronic databases (ERIC, Medline, PsychInfo, and all Citation Databases included in ISI web of knowledge from 1980–30 July 2015 with keywords in abstracts at-risk, famil* risk paired with dyslexia, reading disorders, decoding, and decoding problems), citation search on author names, emails to authors and posting at the list server for Scientific Studies of Reading, hand search of journals (Dyslexia, Annuals of Dyslexia, Scientific Studies of Reading), scanning reference lists, and Google Scholar.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the search and inclusion criteria for studies in this review. Adapted from “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement,” by D. Moher, A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, and The PRISMA Group, 2009. PLoS Med 6(6). Copyright, 2009 by the Public Library of Science.

Inclusion criteria

To be included a study had to consist of a sample of children with familial risk of dyslexia. Family risk was defined as having a parent and or a sibling (a first-degree relative) with dyslexia. The at-risk status had to be verified by testing or self-report of the relative with reading problems. In addition, the studies had to include a control group of children with no known family risk of dyslexia. Studies vary in the nomenclature they have used. To be consistent, in this review, we use the terms “FR–Dyslexia” to refer to children at family risk (FR) who are identified as having reading problems, “FR–NR” to refer to children at family risk who are identified as typical in their literacy outcome (normal reader) and “control” to refer to children from low-risk groups with no family history, who are considered free of reading difficulties.

In the review we focus on three different study designs: (a) group comparisons, (b) longitudinal prediction studies, and (c) experimental intervention studies. We also include references to neurophysiological studies that are tabulated in Table S1 in the online supplement file. The studies included had to report data so that an effect size could be calculated or significance testing reported for either one of three types of comparisons, based on the different designs we found in the studies in this field: (Comparison Type 1) between children at family risk of dyslexia (FR+) and children without such risk (control). In these studies, reading skills are treated as a continuous variable, and family risk children are not separated into two groups based on whether they have dyslexia or not; (Comparison Type 2) between children at family risk later “diagnosed” with dyslexia (FR–Dyslexia) and control children without family risk (control); and (Comparison Type 3) children at family risk who did not fulfil criteria for dyslexia (FR–NR) and control children without family risk (control).

For the longitudinal prediction studies, in addition to the criteria outlined above, the study must have reported a longitudinal analysis concerning either (a) unique predictors of outcomes treated as continuous variables, or (b) unique predictors of literacy outcome when this is treated as a categorical variable (i.e., presence or absence of reading problem). For a study to be included, the analysis needs to have been conducted so that the predictive patterns pertaining to children at family risk and children without such risk could be compared, or the effect of group membership could be determined. For the experimental intervention studies, some kind of training must have been included with the aim of ameliorating difficulties of reading or literacy in children at family risk.

The neurophysiological studies in Table S1 in the online supplement file used a variety of methodologies and were not amenable to meta-analysis. Most of these studies are of small samples; however, their findings will be used when appropriate to reinforce conclusions.

Coding

Some of the at-risk studies are longitudinal and report data from different stages in development. When coding the studies, it became clear that although there are 95 different publications, many were based on the same study sample (there are 21 independent samples). In Appendices A, B, and C (Column 1 in parentheses after the author name), the sample on which the publication is based is indicated. Special attention had to be taken in the coding to avoid bias related to dependency in the data. To make use of as much information as possible from the different publications, information was coded for different developmental stages: (a) Infants and toddlers (below the age of 3 years), (b) Preschool (below 5.5 years and before formal reading instruction starts), (c) Early Primary school (up to 4th grade), and (d) Late primary school/secondary school (from 5th grade and upward). By doing this, we were able to code information from longitudinal studies twice without merging data from the same study in the same analysis. Therefore, we did not violate the assumption of independence in the data. Nonetheless effect sizes in the different developmental stages will be related because 20 out of 69 publications included in the analyses of group comparisons have data coded from more than one developmental stage.

Furthermore, scrutiny of the studies revealed that several different measures were often reported for the same construct, sometimes in different publications. Table 2 presents the indicators that we selected to represent the higher-order constructs in the review. If there was more than one indicator for a construct from the same developmental stage (e.g., Boston naming test and word definitions for vocabulary knowledge), either in the same or in different publications, the mean of the indicators coded was used in the analysis. An advantage of this procedure is that the mean effect size will be more reliable because it is based on two measures of the same construct. The number of studies and sum of participants reported for the different analyses refers to the number of independent samples and participants that have provided data on a construct and the number of effect sizes contributing to a mean effect size is reported in parentheses. However, if the same test was reported in several different publications on the same sample, the same test was only coded once. In many cases, prevalence of dyslexia is reported for the same sample in several publications. However, such data were only coded once for each independent sample based on one set of reading tests in each study. When it was unclear whether data were based on the same sample or parts of the same sample, authors were contacted by email and asked for clarification. Most authors responded, but in cases where they did not, we have based the overview on information provided in the articles.

Table 2. Indicators for the Constructs Targeted in the Review.

| Higher order constructs | Lower order constructs | Indicators coded |

|---|---|---|

| Home literacy environment | Parental education | Reports of educational background |

| Book reading habits and availability | Various questionnaires and self-reports | |

| Parental literacy skills | Tests of parental language and reading skills | |

| General cognitive abilities and perceptual skills | Nonverbal IQ | Nonverbal problem-solving tasks such as Raven, WISC performance, TONI |

| Motor skills | Tests or rating scales of motor skills | |

| Auditory processing | Speech perception, tone perception, tone in noise detection | |

| Visual processing | Tests of visual perception (e.g. Gardner), visual matching, visual cueing | |

| Oral language skills | Articulatory accuracy | Percentage of consonants correct, percentage of intelligible speech |

| Vocabulary knowledge | Defining words, naming pictures, parental scales such as CDI | |

| Pointing at pictures (such as PPVT) | ||

| Grammar | Plural marking, Past tense test, temporal terms, inflection, receptive grammar, expressive syntax | |

| Phonological memory | Nonword repetition tests such as CN Rep | |

| Verbal short-term memory | Digit span, word span | |

| Decoding specific skills | Letter knowledge | Accuracy of letter-naming, naming letter–sound correspondences |

| Phoneme awareness | Phoneme manipulation, phoneme detection, phoneme generation, composite tests where phoneme tasks are in majority | |

| Rhyme awareness | Rhyme oddity task, rhyme generation tasks, rhyme detection | |

| Rapid automatized naming (RAN) | Naming speed for symbolic items (objects, letters, digits or colors) | |

| Literacy skills | Word recognition | Word reading accuracy, word reading fluency |

| Nonword decoding | Nonword reading accuracy, nonword reading fluency | |

| Spelling accuracy | Spelling regular words, spelling irregular words, spelling nonwords | |

| Reading comprehension | Cloze tests or open-ended questions about the meaning of a text |

A random sample of 80% of the studies was coded by two independent raters. The interrater correlation (Pearson’s) for main outcomes (means, SD, sample size, and age) was r = .98 and agreement rate = 93%. Any disagreements between raters were resolved by consulting the original article or by discussion.

Procedure and Analysis

The coding of studies and analyses were conducted using the “comprehensive meta-analysis” program (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2005). Two different effect sizes were used in the meta-analysis. For group differences between the family risk groups and the children from low-risk groups with no family history, we used Cohen’s d. Cohen’s ds were calculated using Hedges’ corrections for small sample sizes (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). When Cohen’s d is negative, children from high-risk groups with a family history have the lowest score. For judging the size of the effect, for group comparisons Cohen’s tentative guidelines were used. According to Cohen, d = 0.2 is a small effect, 0.4 is moderate and 0.8 is large. However, note that according to Cohen (1968), such guidelines should only be used when no better basis for estimating the effect size is available. In the intervention studies, if Cohen’s d is positive, the group that has received the intervention has the highest gain between pre- and posttest. For the intervention studies, two influential policy organizations (What works clearinghouse [WWC] and Promising Practices Network [PPN]), have set a limit of d = 0.25 for when results of high-quality randomised trials should be taken as having policy implications (see Cooper, 2008). In the intervention studies we adopt these guidelines in preference to Cohen. For estimates of prevalence of children in the family risk samples and the control samples affected with dyslexia, we used percentage affected with dyslexia as the effect size.

Mean effect sizes were estimated by calculating a weighted average of individual effect sizes using a random effects model. A mean effect size was calculated if there were two or more studies. A 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for each effect size to establish whether it was statistically significantly larger than zero. If confidence intervals cross zero, the result is not significantly different from zero.

To examine the variation in effect sizes between studies, the Tau2 was used (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). As a rule of thumb, if Tau2 exceeds 1, the variation between the studies is large. I2 was also used to determine the degree of true heterogeneity. I2 assesses the percentage of between-study variance that is attributable to true heterogeneity rather than random error. Notably, I2 does not say anything about the size of the variation between the studies in general, that is, I2 can be 100% or 10% but in both cases variation between studies can be small or large. Thus, I2 can only be used to determine the part of the heterogeneity that is due to true variation between studies rather than sampling error.

For moderator variables, studies were separated into subsets based on the categories in the categorical moderator variable, and a Q-test was used to examine whether the effect sizes differed between subsets. When there were fewer than two studies in a category, this analysis was not conducted. To examine the size of difference between subsets of studies, overlap between CIs was also examined. In cases of multiple significance tests of moderators on the same data set, the results are reported both with and without Bonferroni correction.

When we coded articles, it became clear that there were numerous instances of missing data. If data were critical to calculate an effect size, articles with missing data were excluded if authors did not respond to an email request to provide the data (see inclusion criteria in flowchart). In cases where an effect size could be computed on one outcome but data were missing on other outcomes or moderator variables, the study was included in all the analyses for which sufficient data were provided.

Results From the Review

Appendices A, B, and C contains all the necessary information to replicate the results from our meta-analysis. Appendix A shows characteristics of studies comparing children at family risk (not yet diagnosed) and control children. In the results, data based on Appendix A are presented as group comparisons of children at family risk versus controls not at-risk. Appendix B shows characteristics of studies comparing children at family risk diagnosed with dyslexia and controls and the prevalence of dyslexia. In the results, data based on Appendix B are presented as group comparisons of (a) family risk children with dyslexia versus controls not at-risk and (b) family risk children who are normal readers versus controls not at-risk. Appendix C shows characteristics of intervention studies concerning children with family risk of dyslexia; results based on these data are presented in a separate section of the review on intervention studies.

Prevalence of Dyslexia

Prevalence of dyslexia in family risk samples

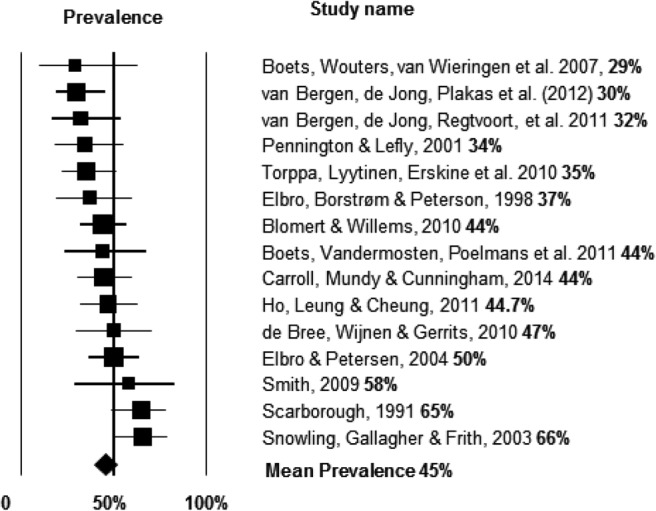

The first analysis considered the prevalence of dyslexia in families where there was a positive history. Fifteen independent studies had examined prevalence of dyslexia/reading disorders in samples of children at family risk. The studies included 420 children with dyslexia (mean sample size 29.4, SD = 13.9, range 9 to 53). Mean prevalence (expressed as percentage) of dyslexia in the family risk samples in the different studies was 45% (95% CI [39%, 51.2%] I2 = 36.5%, Tau2 = 0.08; see Figure 2), confirming that children with a first-degree relative with reading problems have a high risk of developing such problems themselves1 (Hypothesis 1a).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of dyslexia in the family risk samples (mean prevalence across all studies [displayed by ♦] and prevalence for each study [displayed by ■] with 95% confidence intervals presented by vertical lines).

An analysis of moderator variables showed that, as to be expected, the cut-off point for diagnosing dyslexia had a significant impact on the mean prevalence (Hypothesis 1c). In eight studies where the criterion for diagnosing reading disorder was set above the 10th percentile, the mean prevalence was 53% (95% CI [46.3%, 60.0%], I2 = 13.54%, Tau2 = 0.02) while in six studies where the criterion was set below the 10th percentile, the mean prevalence was 33.7%, (95% CI [26.6%, 41.8%], I2 = 0%, Tau2 = 0). Notably, one study was excluded from this analysis because it did not report a cut-off. Because of distributional characteristics, the impact from the diagnostic cut-off variable had to be separated into two categories rather than be analyzed as a continuous variable; the difference between the two categories was significant, Q(1) = 11.84, p < .001, also after correcting for multiple comparisons, p = .001.

Turning to differences in prevalence according to orthography (excluding Chinese studies), for English 54% (95% CI [41.3%, 66.2%], I2 = 52.85%, Tau2 = 0.17). For studies from more transparent languages (Dutch, Danish, or Finnish), 40% (95% CI [35.0%, 46.4%], I2 = 0%, Tau2 = 0). This difference was approaching significance, Q(1) = 3.62, p = .058. Further, after examining the studies, it was clear that more studies with English samples had lenient cut-off criteria. After controlling for cut-off in the analysis of group differences in orthography, the difference between the groups was not significant (β = −0.21, p = .13; Hypothesis 1b).

Prevalence of dyslexia in control samples

To estimate how much the risk of dyslexia is increased in families with a history of reading difficulty, it is important also to assess the prevalence of dyslexia in control samples without a family history. Eleven studies reported information from the control group; the studies included 540 control children without family risk (mean sample size 49.09, SD = 20.5, range 23 to 93). The mean prevalence of dyslexia in the samples without family risk was 11.6% (95% CI [8.4%, 15.8%] I2 = 35.23%, Tau2 = 0.12). Compared with the 45% prevalence of dyslexia found in the family risk group, this confirms that the children at family risk have a reliably higher likelihood of developing dyslexia/reading disorders than children in the general population without such risk (there is no overlap between CIs; Hypothesis 1a).

In six studies where the criterion for diagnosing reading disorder was set above the 10th percentile, the mean prevalence was 16% (95% CI [11.5%, 21.2%], I2 = 6.97%, Tau2 = 0.02) while in four studies where the criterion was set below the 10th percentile, the mean prevalence was 7.8% (95% CI [4.9%, 12.2%], I2 = 0%, Tau2 = 0). One study did not report the cut-off. The difference between the two categories was significant, Q(1) = 4.09, p = .01, also after correcting for multiple comparisons (p = .02). As for differences between orthography, for the English studies,11.2% (95% CI [0.06%, 19.8%], I2 = 46.41%, Tau2 = 0.21); for studies from more transparent languages, 11.6% (95% CI [7.6%, 17.2%], I2 = 38.44%, Tau2 = 15). This difference was not significant, Q(1) = 0.46, p = .50. Finally, the single study reporting prevalence in a family risk study of Chinese readers estimated this to be 47% but no data were reported for controls.

The Home and Literacy Environment of Children at Family Risk of Dyslexia

A small number of family risk studies have explored the hypothesis that parents with dyslexia offer a different “diet” of books, print, and other literary experiences to parents who have not experienced reading problems.

Parental education

One factor which might influence the home literacy environment is parental educational level. Four studies comparing children at family risk (FR+) with controls report data on the education level of the mothers. In these studies, the difference in mothers’ educational levels was small and not significant, d = 0.13 (95% CI [−0.32, 0.07], Tau2 = 0.00, I2 = 0). Three studies reported data on fathers’ education, and here the difference between the FR+ and control groups was larger, d = −0.63 (95% CI [−1.43, 0.17], Tau2 = 0.45, I = 90.75%). One study (Black, Tanaka, et al., 2012) also reported differences in parental verbal language skills (as measured by WAIS verbal IQ), finding that FR+ mothers had significantly poorer verbal skills than those without such risk d = −0.73, (95% CI [−1.20, −0.17]). As for fathers, the difference was smaller and not significant, d = −0.37 (95% CI [−0.91, 0.18]).

Stronger evidence comes from three studies that compared groups according to children’s literacy outcomes. Mothers of children with a reading disorder (FR–Dyslexia) had moderately lower education levels than mothers of controls, but this difference is not significant, d = −0.32 (95% CI [−2.06, 1.42], Tau2 = 2.18, I = 93.09%). A similar pattern is present when comparing mothers of children in the FR–NR group and controls, d = −0.68 (95% CI [−1.15, 0.20], Tau2 = 0.44, I = 76.44%). Compared with controls, fathers in the FR–Dyslexia group have moderately but not significantly lower levels of education, d = −0.45 (95% CI [−1.96, 1.06], Tau2 = 1.07, I = 89.78%). Fathers in the FR–NR group also have moderately lower educational level than fathers of controls and again the difference is significant, d = −0.47 (95% CI [−0.90, −0.04], Tau2 = 0, I = 0%, k = 2).

Home literacy environment

Torppa et al. (2007) made a comprehensive assessment of the home literacy environment (HLE) of families participating in the Finnish Jyväskylä Study. Parental questionnaires completed when children were 2, 4, 5, and 6 years of age provided measures of shared reading, access to print, the child’s interest in reading, and the modeling of literate behaviours in the home. The group means across age for the HLE composites were similar in children at family risk (FR+) and controls for shared reading across age groups, d = −0.08 (95% CI [−0.23, 0.05], Tau2 = 0, I = 0%); for access to print, d = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.20, 0.11], Tau2 = 0, I = 0%; and for child’s reading interest, d = −0.14, (95% CI [−0.28, 0.01], Tau2 = 0, I = 0%). However, the scores for shared reading when the children were 2 years old and for parental modeling of literate behaviors were more variable in the FR group (Hypothesis 2a). Moreover, there was a significant difference between the FR+ and control groups in the frequency of parental modeling activities in reading books, newspapers, magazines, and so forth, with parents from at-risk families typically engaging in such activities less frequently than parents without a history of dyslexia: for fathers, d = −0.44, (95% CI [−0.73, −0.16]) and for mothers, d = −0.66 (95% CI [−0.95, −0.38]; Hypothesis 2b).

Scarborough (1991b) also reported differences in literacy experiences of children from families at risk of dyslexia but data are not reported to allow calculation of an effect size. A graph presented in the article shows that during the preschool years, children who went on to be dyslexic (FR–Dyslexia) were read to less often by their fathers than children from the family risk group who went on to be normal readers and controls. For mothers, there was less joint reading for children at family risk at 30 months than for controls but not thereafter (Hypothesis 2a). However, mothers also rated how often they observed their children reading to themselves. There were fewer occurrences of solitary book reading by the FR–Dyslexia group at all ages (two to three times per week compared with five to seven times for controls) suggesting that group differences may be child-driven and less frequent exposure to books could be self-imposed by affected children. A follow-up in adolescence of children at family risk of dyslexia by Snowling, Muter, and Carroll (2007) found that there was a trend for those in the FR–Dyslexia group to report themselves as reading less than those in the FR–NR group, but this was not significant (p = .08). There were no group differences in how often the families bought books and gave books for presents (p = .25) but the dyslexia group had less knowledge of book titles and authors (but not magazines) as assessed by a print exposure questionnaire.

Exploring whether parental reading skills predict reading outcomes in children at family risk of dyslexia, (Torppa, Eklund, et al., 2011; N family risk dyads = 31, control dyads = 68) showed that beyond the influence of children’s language and decoding-related skills, parental literacy skills predicted early reading and spelling outcomes (Hypothesis 2c). However, parental skills did not account for variance in reading fluency in third grade once children’s skills at earlier points in time were taken into account.2 A similar conclusion was reached by Aro, Poikkeus et al. (2009) using data from the same study.

Endophenotypes of Dyslexia

Having considered what is known about environmental variables, we turn to consider how being at family risk of dyslexia affects the development of perceptual and cognitive skills and ultimately literacy outcomes.

Characteristics of infants and toddlers at family risk of dyslexia

The first developmental stage investigated has been from birth to age 3, namely infants and toddlers. We will review data pertaining to each of the main constructs in turn to evaluate Hypotheses 3a and 3b.

Table 3 shows results from studies of infants and toddlers. First, note that the evidence is scarce. As can be seen in Table 3, there was a significant difference between family risk children who went on to develop dyslexia and control children in general cognitive abilities. Note that the test of cognitive abilities also included language-related tasks. Furthermore, the family risk children showed poorer articulatory skills than peers with no family risk, and also reliably poorer vocabulary knowledge and grammar. This was not the case for the family risk children who did not develop dyslexia (Hypothesis 3b).

Table 3. Group Comparisons in Studies of Infants and Toddlers at Family Risk of Dyslexia.

| Construct | Comparison type | Mean effect size (d) [95% CI] | Number of studies [N family-risk (N control)] | I2 | Tau2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note. CI = confidence interval. | |||||

| * p < 0.05. | |||||

| General cognitive abilities | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.15 [−.61, .31] | 1 [49, (28)] | — | — |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.60 [−1.20, .00]* | 1 [19, (22)] | — | — | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.05 [−.61, .50] | 1 [24, (22)] | — | — | |

| Motor skills | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | .10 [−.14, .34] | 2 [137, (124)] | 0 | 0 |

| Articulatory accuracy | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.93 [−1.57, −.28]* | 1 [19, (20)] | — | — |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.01 [−1.66,−.37]* | 1 [20, (20)] | — | — | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.08 [−.68, .62] | 1 [19, (20)] | — | — | |

| Vocabulary knowledge | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.32 [−.53, −.12]* | 4 [315, (336)] | 0 | 0 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.55 [−1.27, −.24]* | 2 [29, (29)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.55 [−1.24, .14] | 2 [21, (29)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Grammar | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −1.0 [−1.52, −.47]* | 1 [35, (27)] | — | — |

A number of studies not amenable to meta-analysis have reported qualitative differences in language development between FR+ children and controls. An early study by Locke et al., (1997) suggested differences in babbling between children at family risk and controls. Also in infancy, Wilsenach and Wijnen (2004) demonstrated a preference for grammatical passages (as opposed to nongrammatical) containing forms of morphosyntactic agreement in Dutch among not-at-risk compared to at-risk infants, and van Alphen, de Bree et al. (2004; N family risk 35, controls 27) found that FR+ children paid reliably less attention to stress patterns in words than children not at-risk. Koster et al., (2005; N family risk = 111, 87 controls) focused on the growth of vocabulary. For common nouns and predicates, FR+ and typically developing (TD) groups followed the same course but there was divergence for the production of verbs and closed class words when the FR+ group appeared to plateau at a vocabulary size between 50 and 100 words. These findings chime with those of Scarborough (1990, 1991a) who reported group differences in lexical diversity, accuracy of phonological production, utterance length, and grammatical complexity in natural language samples. Finally, Lyytinen, Poikkeus, Laasko, Eklund, and Lyytinen (2001; N = 107 FR+ and 93 controls) documented the emergence of language skills in children at family risk of dyslexia and controls. Group differences did not emerge until 24 months when the family risk group used shorter sentences. Whereas late talkers in the control group tended to catch up, those in the family risk group remained delayed up until 3.5 years.

Finally, six small-scale neurophysiological studies (Table S1 in the online supplement file) reported differences in brain response (primarily ERP) to speech stimuli and two studies reported reduced sensitivity to higher word-level semantic information in infants at family risk of dyslexia.

Characteristics of preschool children at family risk of dyslexia

The studies reviewed in this section concern preschool children, aged from 3–5.5 years (dependent on school entry in the country of sample origin). Table 4, Panel A, B, and C shows the results from these studies. The focus is on the known precursors of word decoding as well as more general developmental progress (Hypotheses 3a and b).

Table 4. Group Comparisons in Studies of Preschool Children.

| Construct | Comparison type | Mean effect size (d) [95% CI] | Number of studies [N family-risk (N control)] | I2 | Tau2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note. CI = confidence interval. | |||||

| * p < 0.05. | |||||

| Panel A: General cognitive abilities and perceptual skills | |||||

| Nonverbal IQ | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.35 [−.55, −.14]* | 7 [315, (336)] | 46.40 | .04 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.21 [−.48, .06] | 6 [201, (276)] | 50.59 | .06 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.06 [−.30, .18] | 6 [227, (242)] | 33 | .03 | |

| Auditory processing | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.31 [−.59, −.03]* | 2 [100, (100)] | 0 | 0 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.80 [−1.57, −.04]* | 1 [9, (22)] | — | — | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.21 [−.77, .35] | 1 [26, (22)] | — | — | |

| Visual processing | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.11 [−.29, .07] | 2 [217, (2148)] | 0 | 0 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.34 [−.82, .13] | 1 [26, (47)] | — | — | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.08 [−.59, .43] | 1 [21, (47)] | — | — | |

| Motor skills | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | .25 [−.03, .53] | 1 [101, (89)] | — | — |

| Panel B: Oral language skills | |||||

| Articulatory accuracy | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.79 [−.79, −.01]* | 3 [164, (133)] | 61.43 | .07 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.41 [−.94, .11] | 4 [125, (187)] | 46.69 | .22 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.31 [−.69, .08] | 4 [87, (187)] | 33.84 | .05 | |

| Vocabulary knowledge | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.65 [−.91, −.38]* | 6 [436, (374)] | 54.61 | .06 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.83 [−1.42, −.24]* | 6 [259, (235)] | 88.38 | .47 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.34 [−.54, −.15]* | 5 [236, (192)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Grammar | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.26 [−.66, .15] | 6 [340, (276)] | 81.35 | .19 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.72 [−1.05, −.40]* | 2 [55, (121)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.28 [−.54, −.02]* | 3 [101, (134)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Phonological memory | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.57 [−.79, −.35]* | 4 [174, (151)] | 0 | 0 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.11 [−1.39, −.84]* | 5 [98, (180)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.47 [−.72, −.22]* | 5 [101, (180)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Verbal short-term memory | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.45 [−.89, −.04]* | 4 [216, (190)] | 74.07 | .13 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.65 [−1.18, −.12]* | 6 [168, (182)] | 80.93 | .35 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.15 [−.40, .11] | 5 [143, (135)] | 10.69 | .01 | |

| Panel C: Decoding specific skills | |||||

| Letter knowledge | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.47 [−.60, −.34]* | 7 [447, (478)] | 0 | 0 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at -risk | −.94 [−1.42, −.45]* | 7 [206, (337)] | 83.74 | .35 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.32 [−.50, −.13]* | 7 [226, (290)] | 4.41 | .002 | |

| Phoneme awareness | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.56 [−.70, −.43]* | 6 [482, (453)] | 0 | 0 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.83 [−1.17, −.48]* | 11 [218, (376)] | 73.74 | .23 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.32 [−.53, −.10]* | 10 [262, (350)] | 39.28 | .05 | |

| Rhyme awareness | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.90 [−1.36, −.44]* | 2 [106, (94)] | 54.85 | .06 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.00 [−1.70, −.23]* | 1 [37, (25)] | — | — | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.55 [−1.12, .02] | 1 [19, (25)] | — | — | |

| Rapid naming | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.61 [−.80, −.41]* | 6 [381, (385)] | 36.08 | .02 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.03 [−1.37, −.69]* | 5 [119, (206)] | 29.4 | .04 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.47 [−.71, −.22]* | 5 [185, (206)] | 0 | 0 | |

General cognitive abilities and perceptual skills

Table 4 Panel A shows mean effect size with 95% CIs, sample size (studies, effect sizes, and persons) and heterogeneity measures for measures of general cognitive abilities, perceptual processes, and motor skills. For nonverbal IQ, it is apparent that groups differ more in the studies comparing FR+ children and controls, than in the studies in which the family risk group with and without dyslexia are separately compared with controls.

There are few studies of auditory or visual processing in this age group. For auditory processing, there is a significant difference in studies that compare FR+ children and controls, and in one longitudinal study, children at family risk who go on to be dyslexic (FR–Dyslexia) demonstrate poorer auditory processing skills than controls but the FR–NR group do not differ significantly (Hypothesis 3a). In addition one neurophysiological study reports reduced sensitivity to rapid auditory processing. Likewise studies of speech perception are inconclusive and data are not amenable to meta-analysis: studies from the Utrecht dyslexia project reported differences between children at family risk of dyslexia and controls in categorical speech perception for consonants (Gerrits & de Bree, 2009), but not for a vowel continuum (van Alphen, et al., 2004). From the same project, de Bree, van Alphen, Fikkert, and Wijnen, (2008) assessed comprehension of metrical stress using pictures of objects with stress patterns which were either strong–weak (′zebra) or weak–strong (ka′do), accompanied by presentations of the object name pronounced with correct or incorrect stress. Overall, FR+ children looked relatively less to the targets when they heard a weak—strong pattern than controls. In addition one neurophysiological study reports reduced sensitivity to phoneme deviance. For neither visual processing nor motor skills are there reliable group differences, but the evidence here is extremely limited with very few studies.

Oral language skills

Table 4 Panel B shows mean effect size with 95% CIs, sample size (studies and persons) and heterogeneity measures for speech and language skills including articulatory accuracy, vocabulary knowledge, grammar, phonological memory, and verbal short-term memory (STM; Hypothesis 3b). For articulatory accuracy, there are few studies of preschool children so the evidence is limited. Across three concurrent studies, FR+ children show reliably poorer articulatory accuracy than controls. However, group differences are not significant when the family risk group is classified according to reading outcome. One of the longitudinal samples overlaps with one of the concurrent studies examining FR+ children. Further, two studies found that, although 3-year-old children at family risk of dyslexia did less well on speech production tasks than controls, their errors obeyed Dutch stress rules (de Bree, Wijnen, & Zonneveld, 2006; Gerrits & de Bree, 2009).

For lexical/vocabulary knowledge, children at family risk have reliably poorer skills than controls. The results show that the FR–Dyslexia group shows a large deficit in vocabulary knowledge in preschool. The FR–NR group also shows a significant deficit, but in size this is only one-quarter of the size compared with the effect size for those who do develop a reading problem. Here, one sample included as a concurrent comparison is also included in comparisons comparing FR–Dyslexia and FR–NR groups with controls. For grammar, children at family risk have reliably poorer grammatical skills than their peers, irrespective of whether they actually go on to develop a reading problem. However, those who develop reading problems have more severe difficulties (Hypothesis 3f).

Turning to measures of verbal/phonological processing, children at family risk have significantly poorer phonological memory than controls for all comparison types (there is one overlapping sample between the different comparisons). FR+ children also have reliably poorer verbal STM than controls; those who go on to have reading problems (FR–Dyslexia) have particularly severe difficulties whereas the FR–NR group does not differ reliably from controls. In this case, there are three overlapping samples between the comparison types and the differences between the family risk and control groups increase when publication bias is taken into account.

Decoding-related skills

Table 4 Panel C shows mean effect size with 95% CIs, sample size (studies and persons) and heterogeneity measures for decoding-related predictors, that is, letter knowledge, phoneme awareness, rhyme awareness and rapid naming (Hypothesis 3c). First, for letter knowledge, it is clear that FR+ children and family risk children who go on to develop a reading problem are slow to acquire letter knowledge. The FR–NR group is also reliably slower to acquire letter knowledge than the controls, but the effect size is only one third compared with the FR+ children. It is noteworthy that effect sizes decline for letter knowledge when publication bias is taken into account; also three samples overlap between the group comparisons.

For phoneme awareness, there is a marked deficit in preschool children at family risk, but this is larger for those who go on to develop a reading problem (FR–Dyslexia). The group difference between FR–NR and control groups is barely significant, and drops to nonsignificant when adjusted for publication bias. Three comparisons involve overlapping samples.

For rhyme awareness the evidence is very limited, but there are reliable differences both between FR+ and control groups, and between FR–Dyslexia and control groups. For rapid naming, all three comparisons suggest reliably poorer skills in family risk children regardless of outcome and controls. However, performance on rapid naming tasks is much poorer in the FR–Dyslexia than the FR–NR groups, as shown by the confidence intervals which show little overlap. Furthermore, the differences between these two comparisons increases when publication bias is taken into account. There are two overlapping samples between the comparisons.

For phoneme awareness it is possible to do a moderator analysis to examine the effect of orthography in studies comparing children at family risk with controls. The results for English studies was d = −0.42, 95% CI [−0.64, −0.20], p = .0001, Q(2) = 1.39, p > .01, Tau2 = 0, I = 0%, k = 3 and for studies from more transparent languages (Danish, Finnish, and Italian) d = −0.60, 95% CI [−0.76, −0.43], p = .0001, Q(3) = 0.52, p > .01, Tau2 = 0, I = 0%, k = 4. This difference was not significant, Q(1) = 1.59, p = .21.

Characteristics of children in early primary school at family risk of dyslexia

The studies reviewed in this section concern primary schoolchildren from school entry to 4th grade (age dependent on school entry in the country of sample origin). Table 5 Panel A, B, C and D shows the results from these studies.

Table 5. Group Comparisons in Studies of Primary School Children.

| Construct | Comparison type | Mean effect size (d) [95% CI] | Number of studies [N family-risk (N control)] | I2 | Tau2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note. CI = confidence interval. | |||||

| * p < 0.05. | |||||

| Panel A: General cognitive abilities and perceptual skills | |||||

| Nonverbal IQ | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.27 [−.50, −.04]* | 5 [315, (336)] | 35.05 | .02 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.19 [−.49, .11] | 5 [192, (248)] | 55.09 | .07 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.02 [−.29, .25] | 5 [190, (201)] | 38.52 | .04 | |

| Auditory processing | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.48 [−.95, −.02]* | 1 [36, (36)] | — | — |

| Visual processing | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.42 [−.75, −.09]* | 3 [151, (186)] | 43.61 | .04 |

| Motor skills | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | .28 [−.01, .57] | 1 [98, (85)] | — | — |

| Panel B: Oral language skills | |||||

| Articulatory accuracy | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.21 [−1.07, .63] | 2 [63, (145)] | 80.48 | .31 |

| Vocabulary knowledge | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.59 [−1.21, .02] | 5 [155, (268)] | 86.28 | .41 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.46 [−.80, −.11]* | 3 [74, (63)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.15 [−.46, .18] | 3 [105, (63)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Grammar | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.31 [−.87, .25] | 2 [81, (164)] | 74.12 | .12 |

| Phonological memory | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −1.02 [−1.42, −.61]* | 3 [51, (53)] | 0 | 0 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.83 [−2.07, .41] | 2 [70, (102)] | 92.18 | .74 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.22 [−.65, .22] | 2 [86, (102)] | 44.53 | .04 | |

| Verbal short-term memory | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.82 [−1.20, −.45]* | 4 [100, (88)] | 34.66 | .05 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.29 [−1.84, −.73]* | 1 [37, (25)] | — | — | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.27 [−.86, .32] | 1 [19, (25)] | 10.69 | .01 | |

| Panel C: Decoding specific skills | |||||

| Letter knowledge | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.41 [−1.20, .41] | 3 [47, (93)] | 76.15 | .62 |

| Phoneme awareness | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.69 [−1.09, −.29]* | 7 [482, (453)] | 70.12 | .19 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.63 [−1.93, −1.33]* | 3 [115, (116)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.56 [−.87, −.27]* | 3 [158, (116)] | 25.08 | .02 | |

| Rhyme awareness | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −1.94 [−2.04, −.95]* | 1 [37, (29)] | — | — |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.13 [−1.48, −.79]* | 2 [63, (34)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.23 [−.75, .28] | 2 [19, (25)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Rapid naming | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.73 [−1.18, −.28]* | 5 [119, (162)] | 66.12 | .17 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.78 [−1.03, −.53]* | 3 [111, (168)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.07 [−.27, .13] | 3 [206, (168)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Panel D: Literacy skills | |||||

| Word recognition | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.88 [−1.20, −.66]* | 9 [440, (378)] | 69.70 | .15 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −2.44 [−2.80, −2.08]* | 9 (15) [246, (354)] | 49.70 | .14 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.29 [−.47, −.10]* | 9 (15) [330, (352)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Nonword decoding | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −1.12 [−1.64, −.60]* | 4 [153, (158)] | 76.42 | .21 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.83 [−2.23, −1.44]* | 6 (10) [163, (264)] | 49.59 | .11 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.56 [−1.00, −.12]* | 6 (10) [257, (264)] | 73.99 | .21 | |

| Spelling accuracy | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −1.06 [−1.88, −.25]* | 3 [37, (29)] | 90.83 | .45 |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −2.10 [−2.40, −1.81]* | 6 (10) [190, (280)] | 9.93 | .01 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.42 [−.63, −.21]* | 6 (10) [288, (280)] | 0 | 0 | |

| Reading comprehension | Family-risk children vs. controls not at-risk | −.77 [−1.14, −.41]* | 1 [67, (57)] | — | — |

| Family-risk children with dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −1.89 [−2.92, −.86]* | 3 (4)[64, (110)] | 84.50 | .91 | |

| Family-risk children without dyslexia vs. controls not at-risk | −.40 [−.91, .12] | 3 (4) [50, (110)] | 54.40 | .15 | |

General cognitive abilities and perceptual skills

Table 5 Panel A shows mean effect size with 95% CIs, sample size (studies and persons) and heterogeneity measures for skills related to general cognitive, perceptual and motor skills (Hypothesis 3a). For nonverbal IQ, there is a significant difference in nonverbal IQ between FR+ and control groups, with no overlap between the samples in the three comparison types. For auditory processing, visual processing and motor skills, the evidence is very limited. There are, however, reliable differences in auditory and visual processing, but not in motor skills between family risk and control groups. In addition, two neurophysiological studies report deviant auditory processing in children at family risk of dyslexia.

Oral language skills

Table 5 Panel B shows mean effect size with 95% CIs, sample size (studies and persons) and heterogeneity measures for oral language skills. For articulatory accuracy, vocabulary knowledge, and grammar, the evidence suggests that the difficulties observed early in development amongst children at family risk of dyslexia in these areas are mostly resolved in early primary school. An exception seems to be vocabulary knowledge, where the FR–Dyslexia group still have reliably poorer skills than their peers (Hypothesis 3a). For phonological and verbal STM, results indicate that the problems here are more severe and persistent and poor verbal STM is observed in the FR+ as well as the FR–Dyslexia groups (Hypothesis 3a). While the number of studies here are limited, there is no overlap between the samples in the different comparison types.

Decoding-related skills

Table 5 Panel C shows mean effect size with 95% CIs, sample size (studies and persons) and heterogeneity measures for decoding-related predictors. For letter knowledge, the difficulties experienced in preschool seem to have resolved by early primary school. However, problems with phoneme awareness are now more severe both in FR+ children and in the FR–Dyslexia group (Hypothesis 3d). For the FR–NR group, the problems are less severe, but the group difference is still as much as half a SD unit (Hypothesis 3f). This is not the case for rhyme awareness: here both FR+ children and the FR–Dyslexia group show poor performance but the FR–NR group do not differ from controls. Similarly, for rapid naming, the FR–Dyslexia group has persistent and severe difficulties, while those who do not develop a reading problem have no difficulties (FR–NR; Hypothesis 3d). For phoneme awareness one study is based on the same sample for all three comparison types, for rhyme awareness all comparison types are based on the same sample and for the other measures there is no overlap.

For phoneme awareness in studies that compared family risk children with controls it was possible to analyze orthography as a moderator. For English studies, d = −0.96 (95% CI [−1.64, −0.28], p = .03, Tau2 = 0.26, I = 72.82%) and for studies from more transparent languages, d = −0.72 (95% CI [−1.33, −0.10], Tau2 = 0.27, I = 71.72%). This difference was not significant, Q(1) = 0.27, p = .60.

Literacy skills

Table 5 Panel D shows mean effect size with 95% CIs, sample size (studies and persons) and heterogeneity measures for literacy outcomes namely word reading, nonword reading, spelling, and reading comprehension. For literacy outcomes, the FR–Dyslexia group has severe difficulties; their skills are around 2 SD units poorer than controls on all measures, implying a cut-off of around the 2nd percentile. Thus, even though the analysis of prevalence showed that the cut-off limits for reading disorder varied considerably, on average at a sample level, the reading disorders are severe. In addition, the FR–NR group have moderate difficulties in all literacy domains compared with the controls but with performance reliably better than that of the FR–Dyslexia group (Hypothesis 3e) except for reading comprehension where there was no overlap between the confidence intervals. For word decoding there are three overlapping samples between the comparisons, for nonword decoding one overlapping and for spelling three overlapping samples.