Abstract

Collagenolysis is essential in extracellular matrix homeostasis, but its structural basis has long been shrouded in mystery. We have developed a novel docking strategy guided by paramagnetic NMR that positions a triple-helical collagen V mimic (synthesized with nitroxide spin labels) in the active site of the catalytic domain of matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12 or macrophage metalloelastase) primed for catalysis. The collagenolytically productive complex forms by utilizing seven distinct subsites that traverse the entire length of the active site. These subsites bury ∼1,080 Å2 of surface area, over half of which is contributed by the trailing strand of the synthetic collagen V mimic, which also appears to ligate the catalytic zinc through the glycine carbonyl oxygen of its scissile G∼VV triplet. Notably, the middle strand also occupies the full length of the active site where it contributes extensive interfacial contacts with five subsites. This work identifies, for the first time, the productive and specific interactions of a collagen triple helix with an MMP catalytic site. The results uniquely demonstrate that the active site of the MMPs is wide enough to accommodate two strands from collagen triple helices. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancements also reveal an extensive array of encounter complexes that form over a large part of the catalytic domain. These transient complexes could possibly facilitate the formation of collagenolytically active complexes via directional Brownian tumbling.

Keywords: collagen, docking, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), protein-protein interaction, encounter complex, paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE)

Introduction

Collagens comprise around 30% of the protein mass of the body (1) and resist general proteolysis. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)2 degrade collagen during cancer cell migration (2), angiogenesis (3, 4), destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques (5), and arthritis (6) and after myocardial infarction (7). For instance, plaques contain a collagen-rich cap and are sensitive to MMP-12 secreted by macrophages that makes them more vulnerable to rupture, precipitating myocardial infarction, or stroke (8).

Collagen fibrils are bundles of staggered triple helices. Each triple helix comprises three extended strands twisted into a right-handed superhelix with hydrogen bonding between chains (9). Each collagen chain is a long series of GXY triplets in which the glycine is in the interior, X is often proline, and Y is often a stabilizing 4-hydroxyproline (Hyp). Because each chain is offset by one residue, the chains have been named leading, middle, and trailing (10). Lack of Pro and Hyp in four GXY triplets on the C-terminal side of the MMP scissile bond in interstitial collagens (types I, II, and III) was proposed to loosen the triple helix (1); this was later observed as 10-fold symmetry (11).

Protease substrates are labeled by increasing distance from the scissile peptide bond with a prime indicating the C-terminal side: P4-P3-P-P1∼P1′-P2′-P3′-P4′ where ∼ denotes the scissile peptide bond. We refer to the residues on the N-terminal side of the scissile bond as “unprimed” and those on the C-terminal side as “primed.” The active site of MMPs is funnel-shaped with a wide end of unprimed subsites and a narrow end of primed subsites. The ∼13-Å diameter of the collagen triple helix appears too wide to fit the 6-Å-wide channel through the primed subsites, prompting a longstanding question of how can the triple helix fit into the narrow channel (12–14). It has long been assumed that the collagen triple helix must partially unwind or be destabilized prior to formation of the Michaelis complex with a collagenolytic MMP (12–18). The archetypal collagenase MMP-1 may unwind the collagen triple helix (13) or rather destabilize the helical state and stabilize the locally unwound state (19). This may occur more readily in Hyp-poor regions that are less stable and more susceptible to localized unwinding (1, 14, 20). The classic collagenases MMP-1, -8, and -13 are joined by MMP-2 and -9 and membrane type MT1-MMP and MT2-MMP (21).

Like these collagenolytic MMPs, MMP-12 comprises pro-, catalytic, and hemopexin-like domains (21). The catalytic domain of MMP-12, a key physiological form (22), was reported to hydrolyze the fibril-forming collagens I, II, III, and V (23–25). We observed digestion of collagens I and V by the MMP-12 catalytic domain to be very slow. Nonetheless, prior x-ray crystallographic studies demonstrated the catalytic domain of MMP-12 to be a model system appropriate for collagenolysis (26). In turn, MMP-12 efficiently hydrolyzes a homotrimeric triple-helical peptide that mimics residues 436–450 of the α1 chain of collagen V, abbreviated α1(V)436–450 THP (27, 28). This collagen V mimic was first characterized as a substrate selective for the gelatinases MMP-2 and -9 (27). This self-assembling miniprotein was used for the docking studies described below. Collagen digestion by MMPs normally requires the catalytic domain working in tandem with the hemopexin-like domain or fibronectin-like inserts (12). The MMP-12 catalytic domain and its interaction with the homotrimeric collagen V mimic provide a simplified model of triple-helical peptidase activity of collagenolytic MMPs.

The interfaces between proteins can be mapped by NMR peak shifts (chemical shift perturbations) but with the complication that conformational changes can also shift peaks (29–31). Such perturbations of NMR peaks are minimal in encounter complexes (32). NMR detection of the line broadening of one partner introduced by an unpaired electron on the other partner provides an excellent means to characterize both specific and lightly populated nonspecific modes of binding (32–35). The unpaired electron, typically introduced in a nitroxide group, has such a strong magnetic moment that its dipole-dipole broadening of the NMR peaks of neighboring protons reaches up to around 25 Å despite its steep decline proportional to 1/r6 (36). These 1H NMR line broadenings are measured as paramagnetic relaxation enhancements (PREs) most reliably as transverse relaxation rate constants, Γ2 (35). The insights from PREs into complexes of lower affinity (35) have been exploited to characterize the structures of mixtures of specific and nonspecific protein complexes with DNA (33), proteins (34), redox protein partners (32, 37, 38), and bilayer mimics (39, 40). Synthesis of a nitroxide-containing artificial amino acid into key locations within a triple-helical peptide model of collagens I–III enabled structural capture of its transient complex with a domain of MT1-MMP (41).

We adopted this latter paramagnetic NMR approach to generate numerous structural restraints between the triple-helical peptide from collagen V and the MMP-12 catalytic domain despite their moderate affinity (28). The measurement of paramagnetic NMR relaxation also presented an opportunity to look at the sparsely populated encounter complexes that have been proposed to precede the formation of catalytic complexes (37). Elucidation of various encounter complexes proved crucial to capturing experimentally, for the first time to our knowledge, the productive complex with the triple helix intact, two of its chains occupying portions of the catalytic channel, and the scissile Gly∼Val peptide bond positioned correctly for catalysis. The encounter complexes form along an extended serpentine surface that centers around the II-III loop (previously designated exosite 2 of elastin interactions (42)). This might suggest a route of guided Brownian tumbling of an MMP on collagen fibrils, which could possibly hasten diffusive search to position the catalytic cleft around the triple helix.

Experimental Procedures

Triple-helical Peptide Synthesis

Self-assembling, homotrimeric α1(V)436–450 THP samples were synthesized by Fmoc (N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl) solid-phase methodology (43) with the artificial amino acid 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl-4-amino-4-carboxylic acid (TOAC) and 15N-labeled glycine, each at a single position in the sequence where desired. The integrity and thermal stability of the triple helix of each sample were determined by circular dichroism spectroscopy (CD). Peptides were allowed to assemble for 3 days at 4 °C immediately prior to use.

NMR Spectroscopy

The E219A-inactivated catalytic domain of MMP-12, designated MMP-12 cat, was prepared as described in a buffer of 20 mm imidazole (pH 6.6), 10 mm CaCl2, and 20 μm ZnCl2 (31). Table 1 explains the choice of conditions used. NMR was performed on a Bruker Avance III 800-MHz spectrometer equipped with a TCI cryoprobe. Sample temperatures were 25 °C with TOAC substitution at P5 of the unprimed substrate and 8 °C with TOAC substitution at P8′ in the primed substrate. These temperatures were chosen to keep the triple helix mostly assembled in each. In the nomenclature of protease substrates, P5 is five residues in the N-terminal direction from the scissile Gly∼Val peptide bond, whereas P8′ is eight residues in the C-terminal direction from the scissile bond. Spectra were processed using Bruker TopSpin and analyzed using CcpNmr Analysis (44). Paramagnetic NMR experiments were performed on enzyme samples at ∼300 μm, and triple-helical peptide was present at 0, 0.1, 0.33, 0.67, 1, and 1.5 molar eq. Diamagnetic controls were recorded after reduction with a 4-fold molar excess of ascorbic acid. PREs emanating from the unprimed substrate were measured on 15N-labeled MMP-12 cat using 15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence modified with two time evolution periods (45). PREs emanating from the primed substrate were measured on 2H/13C,1H3/15N-labeled enzyme using 15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence and 13C heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence with a new improvement that includes a Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill pulse train modified to suppress 3JHH coupling (46), allowing the recording of four time points at 4-ms steps of the relaxation period.

TABLE 1.

Sample conditions and rationale

| Condition | Purpose |

|---|---|

| 10 mm CaCl2 | Stabilizes structure of MMP catalytic domains by populating three sites of binding |

| 20 mm imidazole (pH 6.6) | Maintains structure of MMP catalytic domains and rate of amide hydrogen exchange acceptable for NMR |

| 20 μm ZnCl2 | Populates zinc in active site and between β-sheet and sIII-sIV loop |

| TOAC substitution of triple-helical peptide | Introduces unpaired e− for paramagnetic NMR line broadening to serve as “ruler” to measure distances |

| 6 mm ascorbate | Reduces the unpaired electron of each TOAC to remove paramagnetic relaxation, i.e. makes the complex a diamagnetic control |

| 25 °C | Standard where MMP-12 cat is soluble and its structure and dynamics are well characterized |

| 8 °C | Preserves triple helix destabilized by TOAC at P8′ |

Calculations of Ensembles of Ensembles of Complexes of MMP-12 with Collagen V-mimic Bound

PREs were converted into distances according to Ref. 47. These unambiguous restraints were coupled with ambiguous restraints derived from the shifts of NMR peaks and scaled by the size of the shifts. Rigid body docking was carried out with HADDOCK 2.1 (48) using nearly default parameters with two exceptions: (a) interatomic interaction scaling was set to 0.5 to allow a modest amount of van der Waals violation during rigid body docking, and (b) topology and parameter files were modified to include the presence of non-interacting virtual sites (“dummy atoms”) to represent the nitroxide group of TOAC in anchoring distance restraints. The homology model of the collagen V-mimetic peptide used during docking was mutated from the sequence and crystal structure of Ref. 17 and modified to include the virtual sites to represent the positions occupied by the TOAC nitroxide group, determined to be 4.2-Å distant from the Cα atom of the modified residue in the N-Cα-C plane (49). To improve satisfaction of PRE-based distance restraints at the active site, rigid body docking was performed after removing Phe-237 through Thr-242 from the S1′ specificity loop of the solution structure of MMP-12 cat (Protein Data Bank code 2POJ) (31). These residues were replaced by virtual sites for use in distance restraints. The rigid body docking protocol (it0) of HADDOCK was used to generate a library of ∼7500 unique structural models of complexes of α1(V)436–450 THP with MMP-12 cat. HADDOCK calculations were repeated 20 times with 20% of the restraints randomly removed each time to ensure a diverse library.

Γ2 values for PREs implied by the coordinates of the complexes were then back-calculated at each MMP-12 residue for each member of the library of models of complexes. Ensembles of structures agreeing well with the measured Γ2 values were then generated using a metaheuristic algorithm. This program, q_test.py (available upon request), is small with ∼500 lines of Python code and relatively quickly assembled minimal ensembles. The program generates ensembles through random addition of models to the ensemble until there is no further reduction of Q-factor, which quantifies agreement of model with measurements (37). These maximal ensembles are then stripped of their members that do not contribute significantly to satisfying the PREs (Fig. 5). The program uses the Akaike information criterion (50) to validate the retention of a structure in the ensemble as a statistically significant improvement to accounting for the PREs measured. The minimal ensemble that results was used as the seed for further rounds of addition and subtraction. After generating ∼45,000 ensembles, those structures present in at least 1% of the ensembles were clustered using a pairwise root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) cutoff of 5 Å (51). Clusters present in >80% of the ensembles in the top 1000 ensembles (ranked by Q-factor) were determined to be major species. The percent contributions of these structures to the overall ensemble were optimized using a grid search. Another round of metaheuristic ensemble building was carried out with the ratios of the major species fixed and the use of cross-validation to prevent overfitting. This chose the 20 best ensembles in terms of Q-factor. Although this suggested the encounters present, it left uncertain the amounts of each mode of binding. The occupancies of the most frequent binding modes were optimized again using a grid search to find the populations that best satisfy the PREs measured as evident by improved Q-factor. This ensemble of ensembles was visualized using the program VMD-XPLOR (52).

FIGURE 5.

Logic flow of the Monte Carlo algorithm q_test.py used to identify ensembles of binding poses in accord with the PREs. The structural coordinates tried were drawn randomly from a library of thousands of unique binding poses calculated with HADDOCK. The algorithm depends upon the optimization of the three thresholds x, y, and z. The threshold x defines the improvement needed to justify addition of a model to the ensemble. Lowering this cutoff results in more accurate ensembles but at the expense of significantly longer run time. The cutoff y defines the exit condition. Increasing y tests a larger number of ensembles but at the expense of longer run time. The threshold z defines the level of statistical value as the Akaike information criterion (AIC) above which ensemble members are deemed not to add worthwhile information. Raising z results in smaller ensembles at the expense of potentially higher Q-factors.

The S1′ specificity loop (Phe-237 to Tyr-242) of each major complex was rebuilt and subjected to energy minimization using the Amber99 force field with optimized hydroxyproline parameters (53). This was followed by 100 ps of position-restrained equilibration in a bath of explicit, flexible single point charge water molecules (54) at constant volume and temperature and then at constant pressure and temperature. Buried surface areas of the major complexes were calculated using the program NACCESS (55).

Results

We initially utilized triple-helical and single-stranded peptide models of collagen V to determine the role of triple-helical structure in MMP-12 substrate specificity. The triple-helical substrate α1(V)436–450 THP (C6-(Gly-Pro-Hyp)4-Gly-Pro-Pro-Gly∼Val-Val-Gly-Glu-Gln-Gly-Glu-Gln-Gly-Pro-Pro-(Gly-Pro-Hyp)4-NH2), which has a melting temperature (Tm) of 49.5 °C, has been described (27). MMP-12 hydrolysis of α1(V)436–450 THP was studied at 37 °C by reversed-phase HPLC methods described previously (27) using 370 μm substrate and 17 nm enzyme. Wild-type MMP-12 cat hydrolyzed the substrate (retention time = 7.376 min) after 2 h into products with retention times of 6.610, 8.756, 9.194, and 9.766 min.

To determine whether primary structure alone accounted for the observed MMP-12 cat activity, a single-stranded peptide analog encompassing the sequence of residues 436–450 of type V collagen (Gly-Pro-Pro-Gly∼Val-Val-Gly-Glu-Gln-Gly-Glu-Gln-Gly-Pro-Pro-NH2) was utilized (27). MMP-12 cat (17 nm) was incubated with this single-stranded peptide (730 μm) at 37 °C. Reversed-phase HPLC indicated by a single peak with retention time of 7.108 min that the single-stranded peptide was not cleaved by MMP-12 cat even after 24 h. Thus, primary structure was not sufficient for MMP-12 hydrolysis of the α1(V)436–450 THP, and substrate triple-helical conformation of the peptide greatly enhanced hydrolysis rates. These results suggest that MMP-12 can act as a “true collagenase,” preferentially cleaving a specific sequence in triple-helical conformation while having little or no activity toward the sequence in a non-triple-helical context. Indeed, recent analysis of hydrolysis among thousands of linear peptide sequences indicates that the single strand of collagen V residues 436–450, apart from Val at P1′, lacks cleavage motifs favored by MMP-12 (56, 57).

Binding Evident at the Active Site

The collagen V model THP induces small shifts of amide NMR peaks of E219A-inactivated MMP-12 cat, in most cases with ΔδHN <0.18 ppm, that map mainly to the full length of the active site cleft (Fig. 1, A and B). Modest peak shifts also mapped to remote exosite 2 implicated in elastin digestion (42). The residue with the largest amide peak shift (ΔδHN ≈ 0.22 ppm) is His-222, which coordinates the catalytic zinc and is positioned to respond to triple helix entry into the active site. The amide NMR peak of His-222 responds to titration with the triple-helical collagen V peptide in the intermediate to slow exchange regime with the appearance of a second NMR peak representing the bound form (Fig. 1C), suggesting a comparatively slow off-rate from the active site. (Fast, intermediate, and slow chemical exchange regimes refer to the off-rate exceeding, being similar to, or being less than, respectively, the NMR chemical shift differences between free and bound states.) This places the triple helix in the correct vicinity for hydrolysis. Amide NMR peaks of residues throughout the rest of the catalytic cleft exhibit fast-intermediate exchange in titrations because their peak shifts are smaller than those of His-222. No intermediate exchange broadening was observed outside the catalytic cleft. That the small peak shifts induced in NMR spectra of MMP-12 cat by the triple-helical peptide were small (Fig. 1A) suggests minimal conformational change in the protease. Consequently, the high resolution solution structure of free MMP-12 cat (31) (Protein Data Bank code 2POJ) was used in rigid body docking calculations with a homology model of the α1(V)436–450 triple-helical peptide.

FIGURE 1.

The largest shifts of peaks in NMR spectra of MMP-12 cat introduced by the α1(V)436–450 triple-helical peptide map to the catalytic cleft. A, shifts of amide NMR peaks are plotted versus sequence with a light gray line for individual values and a black line for the rolling average of five points. The shifts of the amide NMR peaks are defined as the radius of a triangle defined by the shifts of the 1H and 15N NMR peaks as ΔωHN = [ΔωH2 + (ΔωN/5)2]1/2 where the larger 15N scale is normalized to the 1H scale. The peak shifts are concentrated at residues at subsites within the cleft (solid colors) or residues packing with them (hatched colors). Exosite 2 (orange; Ile-152 to Gly-155) is the only area outside the catalytic cleft showing significant perturbation. Locations of the β-strands in the sequence are marked with arrows, and the helices are marked with cylinders. B, MMP-12 cat subsites exhibiting significant peak shifts span the length of the catalytic cleft. The colored surface corresponds to the colored areas in A. The gray sphere is the catalytic zinc. Red and white spheres mark the active water. C, spectral changes of His-222, which coordinates the catalytic zinc, strongly suggest binding nearby. Titration with the unlabeled triple-helical peptide shifts the His-222 amide peak (solid line) from that of the free form (fitted blue dashed line) to that of the bound form (fitted red dashed line). The inset shows the line widths of both free and bound peaks as a function of the concentration of α1(V)436–450 THP increasing to 1.5-fold molar excess. The broadening of the line shapes during partial occupancy of the active sites followed by the peak sharpening upon saturation to full occupancy is characteristic of intermediate-slow exchange. r.m.s. error of each fit of a Lorentzian line shape is indicated in the inset.

Intermolecular Paramagnetic Relaxation

To investigate how MMP-12 cat recognizes this triple helix from type V collagen, we sought the potentially transient solution structure of the complex by measuring long range distances between the enzyme and nitroxide spin-labeled THP substrates (Fig. 2). The α1(V) triple-helical peptide was synthesized with the unnatural amino acid TOAC that incorporates a nitroxide group into the cyclized side chain (Fig. 2A). This nitroxide harbors an unpaired electron exerting a strongly distance-dependent (r−6) line broadening effect on NMR peaks of hydrogen atoms within about 25 Å. TOAC was placed at either the P5 position five residues in the N-terminal direction from the scissile Gly∼Val peptide bond or at P8′ eight residues in the C-terminal direction from the scissile bond (Figs. 2B and 3). The triple-helical peptides, which were homotrimers with a one-residue stagger, placed TOAC with this spatial offset in the respective leading, middle, and trailing chains (Fig. 2A). The peptide with TOAC at P5 retained most of the thermal stability typical of collagen triple-helix (Fig. 3A). The TOAC substitution at P8′, however, decreased the Tm to 16 °C (Fig. 3B). Consequently, NMR studies using the P8′-substituted peptide were carried out at 8 °C to ensure that its triple helix remained fully folded.

FIGURE 2.

The collagen V-mimicking triple-helical peptide was synthesized with a nitroxide-containing amino acid to introduce strongly distance-dependent PREs to MMP-12 cat. A, the modified triple-helical peptide shows the nitroxide-containing TOAC residue with sticks and the leading, middle, and trailing chains in red, yellow, and blue, respectively. The radially decreasing violet color symbolizes the strong distance dependence of PRE that decreases in proportion to 1/r6 where r is the distance between unpaired electron and the proton monitored by NMR. B, peptide synthesis placed TOAC at either the P5 or P8′ position in the homotrimer. This introduces paramagnetic relaxation radiating up to 25 Å from each nitroxide group. The paramagnetic relaxation emanating from the TOAC at P5 is symbolized by green, and that from TOAC at P8′ is symbolized by violet. C, relaxation patterns indicate that Gly-105 at the unprimed end of the catalytic cleft is near a nitroxide at P5, whereas Gly-179 at the primed end of the cleft is near a nitroxide at P8′. The relaxation in the left panels was measured by the widely used two-point method (35, 45). In the right panels, the new multipoint approach (39–41) was used. Its exponential decays confirm suppression of J coupling. Error bars indicate S.D. of spectral noise. The unpaired electron in TOAC was reduced, and its paramagnetic relaxation was removed by incubation with 6 mm ascorbate, establishing the diamagnetic reference state.

FIGURE 3.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy demonstrates the formation of triple helix and thermal stability of the TOAC-substituted triple-helical peptides used in this study. CD spectra of the triple-helical peptides with TOAC substitution at the P5 position (A) or the P8′ position (B) are shown. The ratio of the peak near 210 nm to the peak near 230 nm describes the degree of triple helix formation, which in this case is 8:1 for the unprimed substrate and 12.3:1 for the primed substrate, indicating the triple helix to be intact. Each inset shows the thermal melting curve for each triple-helical peptide. The Tm values are 28 °C with P5 substitution and 16 °C for P8′ substitution. NMR was performed at a temperature below the Tm of the substrate for triple-helical integrity during the experiment. Above each spectrum is a schematic representation showing the location of the TOAC residue within the sequence. mdeg, millidegrees.

The TOAC labels result in distance-dependent PREs that are NMR line broadenings radiating as far as 25 Å from the nearest TOAC (Fig. 2B). The PRE patterns indicated a clear directionality of each TOAC-substituted triple-helical peptide at the catalytic cleft. Gly-105 at the unprimed end of the catalytic cleft mainly exhibits a PRE when TOAC is present at P5 (Fig. 2C). In contrast, Gly-179 at the primed end of the cleft shows the opposite behavior of PRE only with TOAC at P8′ (Fig. 2C).

Paramagnetic Relaxation Implicates Remote Binding

Overshadowing the paramagnetic broadening around the active site emanating from TOAC are many additional PREs (∼200 in total) radiating widely across the enzyme from locations other than the active site. Nonspecific, remote binding of collagen V model peptides was consistently observed in titrations in the form of extensive PREs far from the active site. For example, this is obvious in the broadening of methyl NMR peaks (surveyed only with TOAC at P8′) of a patch of side chains (Leu-160, Val-162, and Ile-191) next to the β-sheet (Fig. 4) and near aforementioned exosite 2. The large number of PREs (from TOAC at either P5 or P8′) remote from the active site means that any standard docking attempting to satisfy all PREs simultaneously with a single mode of binding is inappropriate for representing the mixture present. The “minor states” seemed collectively to be more abundant than the complex with triple-helical peptide bound at the active site.

FIGURE 4.

Paramagnetic NMR line broadenings introduced by triple-helical peptide with TOAC at P8′ are extreme and remote from the active site. A, i–iv, 13C heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence of Ile-Leu-Val-labeled, free MMP-12 cat (cyan) at 800 MHz reveals several methyl peaks broadened away by addition of α1(V) THP with TOAC on the primed side of the scissile bond (purple). Ile-180 is in the catalytic cleft. Ile-191, Val-162, and Leu-160 cluster on the β-sheet, suggesting alternative modes of binding. Each asterisk (*) symbolizes all three degenerate methyl protons. B, i–iv, concentration dependence of paramagnetic broadening. The last column was recorded after reduction with 6 mm ascorbate, which restored NMR peaks broadened by the spin-labeled triple-helical peptide.

Computing Ensembles of Complexes Accounting for PREs

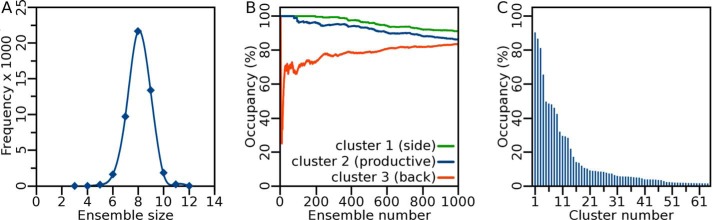

The mixture with remote binding motivated us to adapt the ensemble of ensembles strategy pioneered by Clore and co-workers (58). We developed a new docking protocol to identify the triple-helical peptide bound at the active site among the myriad of encounter complexes. Development of the docking protocol resulted in five steps: generation of a library of thousands of potential docked poses of α1(V)436–450 THP with MMP-12 cat, selection of a minimal ensemble of poses, identification of the major docked poses, weighting of the major complexes to match PREs, and identification of a minimal ensemble of ensembles (58) to portray aptly the mixture of complexes present. The interactions of α1(V)436–450 THP with MMP-12 cat are underdetermined in that the number of potential binding modes outstrips the hundreds of distance restraints measured. Consequently, we sought to avoid overfitting through use of our in-house algorithm used to identify parsimonious ensembles of binding poses consistent with the PREs measured (q_test.py; Fig. 5). Typically, the parsimonious ensembles comprise 6–10 members (Fig. 6A). Although the ensembles vary, the ensembles agreeing best with the PREs (low Q-factor) consistently contain the same few models of complexes of triple-helical peptide with MMP-12 (Fig. 6, B and C). Three major poses are present in over 80% of ensembles with lowest Q-factor (Fig. 6B). These three structures collectively account for the PREs with a reasonable Q-factor of 0.37. One of these occupies the active site (Fig. 7), and the other two are major encounter complexes (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 6.

Statistics of parsimonious ensembles generated by the metaheuristic algorithm q_test.py. A, minimal ensembles generated showed a typical Gaussian distribution of between six and 10 members with an ensemble size of 8 being most frequent. B, certain clusters of structures were highly represented among the 1000 best ensembles (when ranked by Q-factor). Three clusters (clusters 1, 2, and 3) appeared in over 80% of ensembles. C, occurrence of clusters among the 1000 best minimal ensembles. 65 clusters were represented in at least 1% of ensembles of which only three (clusters 1, 2, and 3) occurred in more than 80%.

FIGURE 7.

Productive complex of a collagen triple helix in the active site of an MMP revealed by paramagnetic NMR. A, structure of the collagen V-derived triple helix primed for hydrolysis reveals that both the middle (yellow surface) and trailing (blue surface) chains fit in the active site. The leading strand (red surface) makes little contact with the enzyme. The region of the large dashed box is expanded in walleyed stereo in B. The small dashed boxes show approximate locations of TOAC residues, each containing a spin label. B, middle and trailing strands manage to fit in the active site through efficient subsite usage, positioning the trailing chain of the Michaelis complex for initial hydrolysis. Active water (red and white spheres) and the carbonyl oxygen of the Gly at the P1 position (blue sticks of Gly-88) coordinate the active site zinc (black sphere). This positions the carbonyl carbon of Gly at P1 in the trailing chain for nucleophilic attack by the water. Seven distinct subsites (labeled in the left image) are occupied by side chains (labeled with magenta in the right image) from the middle and trailing chains. Dots are plotted for peptide atoms in apparent contact with the enzyme. Two bad contacts outside subsite S3′ are colored blue-green. Green dashes mark a hydrogen bond inferred between Lys-241 and Gln at P5′. The exosite marked was identified in Refs. 28 and 67.

FIGURE 8.

Ensembles of structures containing remote encounter complexes account for the distribution of paramagnetic broadenings from TOAC-substituted triple-helical miniproteins (A–C). The productively bound member of the ensembles is symbolized by the black arrow. The two major remote binding poses (red, yellow, and blue schematic) are members of most of the ensembles. An ensemble of ensembles (mesh representing 20% occupancy) representing a cohort of lowly populated or mobile binding poses is required to explain the majority of the remaining PREs.

Productive Mode of Binding

Of the major modes of binding identified, the one occupying the active site was of most interest because of the proximity of the scissile bond to the catalytic zinc. Temporary removal of six residues from the S1′ loop during rigid body docking enabled the triple helix to rotate into and fill the catalytic cleft on the unprimed side, thereby satisfying the PRE-based distance restraints better. Once the S1′ specificity loop had been rebuilt, there was a degree of steric clash between the enzyme and the triple-helical peptide in the resultant structure (supplemental Movie S1). This clash was removed by performing a round of energy minimization that resulted in a small amount of distortion to both the enzyme and substrate (Fig. 9). The distortion to MMP-12 cat was limited to the C-terminal ends of the III-IV and V-B loops and part of the S1′ loop (Fig. 9, A and C). The distortions of both of these areas are well within the ranges of experimental variation among the crystallographic and solution NMR coordinates of MMP-12 cat available in the Protein Data Bank (Fig. 9A). 15N relaxation experiments have shown them to be flexible (59). Intriguingly, R1ρ measurements (60) showed that both these areas, which together form the upper and lower rims of the narrowest part of the active site (Fig. 9C), undergo sub-ms motions postulated to be consistent with 1–4-Å widening of the cleft. The distortions to the triple helix are minor and are mostly restricted to the scissile triplet of the trailing strand and Glu-20 of the leading and middle strands (Fig. 9, B and D).

FIGURE 9.

Structural distortions in the complex upon binding appear small, localized, and within the experimental range of variation. A, per-residue Cα r.m.s.d. of crystallographic and NMR solution structures of MMP-12 cat in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The blue line shows the structural changes needed for MMP-12 to accommodate two chains of the triple helix. The red line corresponds to the natural diversity of all MMP-12 structures in the Protein Data Bank (currently 18 structures). All the significant distortion needed for MMP-12 cat to accommodate the triple helix (r.m.s.d. > 1.0 Å; residues 178–182, 225–230, and 237–242) maps to flexible loops and falls within the natural range of structural diversity. B, per-residue structural changes are plotted for the α1(V)436–450 triple-helical peptide as it binds to MMP-12 cat. The largest change occurs in the trailing strand (blue line) in the scissile triplet. Only Glu-20 of the leading and middle strands (red and orange lines) exhibits significant distortion, which accompanies displacement of the scissile triplet of the trailing strand. C, per-residue structural changes in MMP-12 as it binds the triple-helical miniprotein plotted as r.m.s.d. of free versus bound forms (i.e. pre- and postenergy minimization). Much of the distortion is confined to the flexible S1′ specificity loop, i.e. the “lower lip” of the active site. D, the information of B is plotted onto the surface of the homology model of the α1(V)436–450 triple-helical peptide. The boxed region shows the approximate location of the scissile region.

The major pose in the active site (cluster 2 in Fig. 6B) places the carbonyl group of the scissile Gly∼Val peptide bond of the trailing strand close enough for attack by the water molecule positioned for catalysis (Fig. 7). Consequently, we consider this the first productive complex of a triple-helical substrate with an MMP protease to be determined experimentally. The occupation of each of the subsites of MMP-12 cat in the structure of the productive complex by the triple helix from collagen V is near almost all of the largest NMR peak shifts induced in MMP-12 cat (Fig. 1). After refinement of this complex in explicit water, the MMP-12 cat exhibits a small deviation of the backbone from the NMR structure of the free state with r.m.s.d. of 0.56 Å. When hosting the triple-helical peptide, the widening of the cleft via outward shift of the S1′ loop appears <1.7 Å. The deviation of the triple helix from the starting coordinates is also small with r.m.s.d. of 0.65 Å. That is, both partners remain mostly unchanged. The pattern of hydrogen bonds inferred from the coordinates of the triple helix appears unchanged by the docking procedures.

Contrary to recent proposals that a single chain of the triple helix must be released for insertion in the catalytic cleft of the MMP (16–18), both the middle and trailing strands fit neatly and intact into the catalytic cleft with extensive subsite usage along both the upper and lower rims of the cleft. This stereospecific and productive complex has extensive interfacial buried surface area (Fig. 7) of ∼1080 Å2, which is much greater than the interfaces of the other two binding poses (Fig. 8). The trailing chain contributes around half of the surface area buried in the interface of the productive complex. Its Val side chain at the P1′ position is buried in the main S1′ pocket (Fig. 7B). The Pro at P3 of the trailing chain forms extensive hydrophobic contacts with the S3 subsite formed from the N terminus and the N-terminal portion of the Met loop (Fig. 7B). The trailing chain places its Glu side chain at P4′ into the adjacent channel close enough to Thr-215 for hydrogen bonding. The trailing chain also appears to form hydrogen bonds with the S1′ loop.

The middle strand contributes 40% of interfacial surface area and fills five subsites traversing the entire length of the active site (Fig. 7B). The Hyp at position P5 of the middle strand forms both hydrophobic and polar contacts with subsite S4. Pro at P3 of the middle chain may contact the enzyme with a single atom. The Pro at P2 buries deeply into subsite S2. Both Val side chains of the G∼VV triplet of the middle strand tuck snugly underneath the S-shaped loop into subsites S1 and S2′, respectively (Fig. 7B). Finally, Gln at P5 fits into the S3′ subsite where it appears to donate a hydrogen bond toThr-210 of the protease. (The corresponding positions in MMP-1 and -8 are essential to collagenolysis (61, 62).) Around 10 intermolecular hydrogen bonds are suggested by the coordinates of the productive complex. The hydrogen bonding presumably promotes and specifically positions the productive binding. The middle chain forms apparent hydrogen bonds with the β-sheet. In effect, the two chains of the triple helix and the extended segment of the S1′ loop continue the network of hydrogen bonding of the five-stranded β-sheet by the transient addition of these three additional strands.

Principal Remote Encounter Complexes

The productive mode of binding accounts only for a minority share of the PREs observed (Fig. 10, top row) with Q-factor of 0.68, strongly implying interactions elsewhere. The PREs centering on the II-III loop, the β-sheet, and the N terminus require understanding. In the ensembles of complexes computed as collectively satisfying the intermolecular PREs, cluster 1, which binds on the “left side” in Fig. 8, is even a bit more frequent than the productive binding (Fig. 6B). This most frequent pose passes by multiple chemical groups with NMR peaks completely broadened by TOAC positioned at P8′ in the triple helix. In the β-sheet, these include the methyl groups of Leu-160 and Val-162 (Fig. 5) and amide groups of Leu-160 to Val-162 and Ala-195 (Fig. 10B). In the loops flanking this channel, the amide peaks of Thr-154, Ala-157, Ala-167, His-172, Ile-191, and Gly-192 joined by the Ile-191 δ-methyl peak are also nearly completely broadened by the TOAC at P8′ (Γ2 ≥ 100 s−1 in Fig. 10B). That is, the triple helix here in cluster 1 occupies a hydrophobic surface groove running from the β-sheet to the unprimed end of the catalytic cleft (Fig. 8B). At corresponding locations in this channel, TOAC substitution instead at P5 introduces PREs with Γ2 of 35–46 s−1 only at Gly-155, Met-156, and Val-162 (Fig. 10A), suggesting only transient approaches by the P5 position of the triple helix. Cluster 3 represents the third most frequent binding pose (Fig. 6B). It binds the back of the catalytic domain over helix A near exosite 3 (Fig. 1A) most distant from the active site (Fig. 8). Combining the productive and two main encounter complexes significantly improves the accounting for PREs (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

Ensembles of structures are needed to account for the many PREs measured. Theoretical PREs (colored symbols) are compared with measured PREs (gray) introduced by a 1.5-fold excess of the triple-helical peptide with TOAC substitution either at P5 (A) or at P8′ (B). The PREs from triple-helical peptide to amide protons are marked with gray columns for measurements and squares for back-calculations from the productive model in red, from the three frequent binding poses (clusters 1–3) in blue, and the ensemble of parsimonious ensembles in green. Triangles mark PREs from P8′ to methyl groups measured (gray) or back-calculated (color). Theoretical PREs calculated from the productive mode of binding (red) explain broadening in the active site (e.g. residues 102–105 and 221–230 in A and 202–220 in B) but fail to explain other areas experiencing significant broadening (e.g. residues 140–165 in B). Addition of the two frequently sampled remote poses explains the PREs of several other areas (blue). However, an ensemble of ensembles is required to model (green) the widely observed PREs with the comparatively high quality of a Q-factor of 0.21. Error bars indicate S.D. of spectral noise.

Many Lesser Encounters

Nonetheless, many measured PREs remain unexplained by the three main modes of triple helix binding (Fig. 10). Among the parsimonious ensembles selected by the new software, the most frequent sizes are seven to nine members (Fig. 6A). These additional poses occur in dozens of additional clusters of lower populations (Fig. 6C). We evaluated groups of these ensembles to model the encounter complexes (58). This is consistent with a cloud of minor encounters and their dynamic variation. The mesh in Fig. 8 represents the likelihood of a volume containing atoms from the THP, in this case for at least 20% of the distribution. Weak, transient associations are generally accompanied by minimal NMR peak shifts compared with specific complexes (63), which also seems true of the triple helix interactions with MMP-12 cat with the possible exception of the peak shifts of exosite 2 (Fig. 2). Collecting the best 20 ensembles containing 6–10 binding poses each improves the Q-factor to a respectable 0.21 and predicts the majority of measured PREs. However, PREs of residues 213, 214, and 216 to TOAC at P5 (Fig. 10A) remain unexplained, perhaps suggesting a minor population of alternative peptide positioning in the active site not captured by the structural ensembles. One possibility for this minor population is the monomer fraction of this peptide present at the 25 °C used (see Fig. 3A, inset). The monomer fraction may have been larger than its normal presence in triple-helical peptides (64, 65). Nonetheless, MMP-12 chooses the triple-helical form for hydrolysis but not the monomer as described above.

Overall, the cloud of transient poses encircles the II-III loop (exosite 2), crosses the top of the β-sheet (Fig. 8A), and courses down the back of the catalytic domain (Fig. 8C). This appears to be a continuous, serpentine path of occupation that leads through the active site, around the S-shaped loop, over the β-sheet, and down the spine of helix A (Fig. 8).

Discussion

Two Chains of a Collagen Triple Helix Fit the Active Site

Two of three chains of a triple helix occupy most of the length of the catalytic cleft of MMP-12 cat in this first experimental measurement of productive triple helix binding (Fig. 7). Dozens of distance restraints from paramagnetic NMR position two chains of the collagen V-mimetic peptide into the cleft of MMP-12. It may be possible that this structural snapshot of the Michaelis complex can precede a subsequent intermediate in which a single chain occupies the narrower primed subsites, perhaps after the first chain is hydrolyzed. Or appropriate conditions may enable a collagenolytic MMP to draw a single chain from a triple helix into its primed subsites, i.e. high enough temperature or both domains of a full-length collagenase working together to unwind the triple helix partly (16, 17). However, the productive mode of binding observed with the triple helix intact suggests that chain separation may not be required to initiate triple helix digestion. With the active site intact (with only modest NMR peak shifts) and intact collagen triple helix occupying it, the scissile peptide bond is near the water ligand of the catalytic zinc poised for hydrolytic attack (Fig. 7B) but prevented by lack of the general base Glu-219. Another possible implication of the two-stranded insertion captured in this structure is that the proximity of the middle strand to the catalytic zinc and water suggests the possibility of a minimal and quick reorientation to position its scissile Gly∼Val bond for attack.

Parallels at the Active Site Interface

Trailing Chain

The more superficial binding of a collagen II-based triple-helical peptide to MMP-1 in the crystal structure placed the P1–P5 residues of the trailing chain into unprimed subsites of the active site (17) in a fashion analogous to the positioning of the P1–P5 residues of the middle chain in the productive complex with MMP-12 cat (Fig. 7B). However, the trailing chain in the productive complex with MMP-12 cat additionally positions its P1–P6 residues in contact with the other rim of the unprimed side of the active site (Fig. 7B), whereas the hypothesized productive complex with MMP-1 only predicted Pro at P3 and P6 to make such contacts (17). The position of the trailing strand more deeply inserted in the MMP-12 active site (Fig. 7B) strongly resembles the positioning of a hexapeptide caught immediately after cleavage (26) with an average Cα displacement of 2.8 Å (close to the crystallographic resolution limit of 1.9 Å), consistent with the coordinates of Fig. 7B depicting productive binding.

Middle Chain

The large contribution of the middle strand from this collagen V mimic to buried surface area and to five subsites at the interface suggests this chain to be extremely important in complex formation despite not itself being primed for cleavage. The middle chain in the productive complex with MMP-12 cat is mimicked partly by the hypothetical productive model of the collagen II triple-helical peptide with MMP-1 (17, 66) on the wider, unprimed side of the active site. The hypothesized productive complex places the P1–P5 residues of the middle chain in contact with the unprimed subsites (17) similarly to the productive complex with MMP-12 cat (Fig. 7B). However, the middle chain in the productive MMP-12 complex measured in solution runs deeply through the full length of the cleft. In the hypothetical model proposed for MMP-1 in contrast, the middle chain is excluded from the narrow, primed side of the cleft (17). The propeptide fragment crystallized in the active site of MMP-13 (66) is a much better mimic of the deep course of the middle chain of the productive complex of MMP-12 with triple-helical peptide. The MMP-13 propeptide chain from Arg-41 to His-48 is displaced from the middle chain in the productive MMP-12 complex by 2.25 Å on average across the Cα traces of the peptide backbones. Nonetheless, two chains occupying, in parallel, the full length of the cleft is unique among MMP complexes. The dynamic fluctuations of the S1′ specificity loop in solution (59) might allow enough widening for the two chains of the triple helix to enter the full length of the cleft. The more rigidified state of this loop in crystals at cryogenic temperatures might impede entry of two chains.

Contacts for Triple-Helical Peptidase Activity

Mutations of MMP-12 that compromise its collagen triple-helical peptidase activity the most are F185Y, G227F, T239L, and K241H (67). Phe-185 (Phe-166 in MMP-1) contributes both to subsite S2 and to maintaining the conserved hydrophobicity of the groove around the S-shaped loop. The hydroxyl group of F185Y may directly impair triple helix binding. The G227F lesion fills the S3 subsite occupied by the triple helix with the bulky phenyl moiety. The ϵ-amino group of Lys-241 is suggested by the coordinates of the productive complex to be capable of forming hydrogen bonds with Gln at the P5′ position of the trailing chain (Fig. 7B) and with Glu at P7′ of the leading chain. Thr-239 seems pivotal, and its lesions heavily impact catalytic turnover of triple-helical substrates. Not only does Thr-239 contribute much surface area to S1′, but it also forms hydrogen bonds with the trailing strand and is straddled by the valine pair in the scissile G∼VV triplet. The MEROPS database suggests the MMP-12 preference of collagen substrate sequence (like other MMPs) to be GPXG∼ΦXGX where Φ is hydrophobic. The occupation of subsites by the trailing chain of the α1(V)436–450 triple-helical peptide is in excellent agreement with these sequence requirements, further supporting its positioning as the starting orientation for digestion of the triple helix.

The distances estimated from paramagnetic relaxation positioned the peptide bond of the scissile site in the collagen V triple-helix, i.e. the G∼VV triplet of the trailing chain, poised for hydrolysis (Fig. 7B). However, digestion in the subsequent GE∼Q triplet was observed in the case of MMP-12 (28). This might reflect hydrolysis after the initiating hydrolysis. The Glu∼Gln peptide bond of the leading chain is only a 120° rotation and a one- to two-residue spatial translation from the Gly∼Val bond positioned for attack (Fig. 7B); it is a short corkscrew rotation apart.

Encounter Complexes and Implications

Encounter complexes have been well characterized among electron transfer proteins but deserve study broadly among other protein associations (32). Minimal ensembles reported to represent the loosely bound, transient encounter complexes observed by paramagnetic NMR in other protein associations have up to 7–10 members (38, 58, 68). Remote binding of the collagen V miniprotein to the β-sheet, active site, and possibly elsewhere had been suggested by its protection of these surfaces of MMP-12 cat from solvent PREs introduced by a Gd·EDTA probe (28). However, that previous approach lacked the wealth of distance measurements to orient the poses of the collagen V-derived triple helix made possible by spin labeling it.

Encounter complexes have been hypothesized to speed up the process of molecular recognition by reducing the search from three to two dimensions through the formation of weak electrostatic (58) or hydrophobic (38) interactions. The hydrophobic and conserved nature of the large serpentine path filled by transient complexes reinforces its potential as harboring “loading complexes”, i.e. attracting the collagen triple helix to the catalytic domain and then often to the catalytic cleft from where it can proceed to form a hydrolytically active complex (Fig. 11A). In a physiological environment, insoluble collagen fibrils are essentially immobile. Therefore, it is the MMP that diffuses upon the fibrils in the search for productive complexes (69, 70). The encounters of multiple surfaces of the MMP-12 catalytic domain with a collagen triple helix may increase the frequency of collisions. Such a process of guided tumbling could expedite the diffusional search to productive engagement, perhaps by a potential route marked by the blue arrow in Fig. 11A.

FIGURE 11.

Remote binding to exosite 2 and a hydrophobic channel topping the β-sheet might impart a hypothetical advantage to reload another triple helix into the active site. A, proposed route of diffusion that might reload productive binding (blue arrow) after molecular recognition near exosite 2. B, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (magenta; Protein Data Bank code 2E2D) reaches its long sA-sB loop (magenta surface) around the S-shaped loop to fill the channel over the β-sheet to approach exosite 2. This occupies the hypothetical path of diffusion of the triple helix.

This potential route between loops over the β-sheet is utilized in other contexts. The extended sA-sB loop of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2, a physiological inhibitor of MMPs, occupies the hydrophobic portion of this path in its association with MT1-MMP, specifically reaching between the S-shaped, IV-V, and II-III loops over the β-sheet (71) (Fig. 11B). This projection just touches the edge of exosite 2 at the II-III loop. The B-type propeptide of MMP-13 was also observed reaching from the active site into the proximal portion of the corresponding groove between the S-shaped and IV loops of MMP-13 (66). Intriguingly, the predominant pose of the collagen V triple helix crosses this same groove between the S-shaped and IV-V loops of MMP-12 cat (Fig. 11). Thus, this groove appears to serve as a recognition channel for narrow protein partners of MMPs.

Exosite 2 at the II-III loop enhances affinity and catalytic efficiency for soluble elastin fragments despite being ∼20 Å from the catalytic cleft (42). This reinforces the hypothesis that this loop may be important in the molecular recognition of fibrillar substrates en route to the active site. The II-III loop is also critically important for the molecular recognition of membrane bilayers (39, 40) and a receptor (72). These precedents and the PREs from spin-labeled triple-helical peptides encompassing the II-III loop may be consistent with the possibility of a functional role in initial associations with collagen triple helix.

The present study was performed utilizing an MMP catalytic domain alone. As the presence of the C-terminal hemopexin-like domain in a full-length MMP enhances affinity for (73) and catalytic turnover of (74) triple-helical collagen, it may be worth considering whether one potential role of the hemopexin-like domain could be to attract and stabilize the productive binding of the triple helix from among the multitude of alternative binding poses.

Conclusions

A productive complex between a collagen triple helix and an MMP catalytic domain has now been observed experimentally, which was made possible by paramagnetic NMR measurement of numerous intermolecular distances. The trailing chain of this triple helix runs deeply through the catalytic channel with positioning very similar to that reported for a linear peptide substrate (26). The accompanying path of the middle chain is similar to the path of a propeptide fragment bound to MMP-13 (66). However, the observation of two chains of a triple helix fitting the full length of the catalytic channel, with both triple helix and active site little changed in structure, is unexpected and novel. Also surprising is the wealth of remote encounter complexes detected winding loosely from the back of the catalytic domain across the β-sheet past exosite 2 and between three loops toward the active site. This serpentine cloud of orientations raises the question of its relevance to enhancing attraction for collagen fibrils and guiding diffusional reorientation of the catalytic domain on collagen. The two-stranded triple helix insertion into the active site and the convoluted array of encounter complexes observed interject new concepts for reflection and experimentation regarding the initiation of collagenolysis. The channel occupied by the most abundant encounter might prove druggable. Regardless, the productive mode of binding is now available as a structural template for rational development of inhibitors acting by molecular mimicry or by competing with binding at outlying subsites.

Author Contributions

S. R. V. D. conceived and coordinated the project. S. H. P., S. R. V. D., and G. B. F. designed the research. S. H. P. and T. S. B. measured the NMR data. S. H. P. designed and performed the structural calculations. D. T-R. and G. B. F. performed chemical syntheses. S. H. P. and S. R. V. D. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Lindsay Smith for analyzing collagenolysis by MMP-12 and Janelle Lauer for analyzing MMP-12 peptidase activity by HPLC.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM057289 and R01 CA098799 and Grant T32 GM008396 and American Heart Association Grant 0855714G. The 800 MHz NMR spectrometer was purchased with funds from National Institutes of Health Grant S10 RR022341 and the University of Missouri. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Movie S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2N8R) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- MMP-12 cat

- catalytic domain of E219A-inactivated MMP-12

- PRE

- paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

- THP

- triple-helical peptide

- TOAC

- 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl-4-amino-4-carboxylic acid

- Hyp

- 4-hydroxyproline

- MT

- membrane type

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation.

References

- 1.Fields G. B. (1991) A model for interstitial collagen catabolism by mammalian collagenases. J. Theor. Biol. 153, 585–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf K., Wu Y. I., Liu Y., Geiger J., Tam E., Overall C., Stack M. S., and Friedl P. (2007) Multi-step pericellular proteolysis controls the transition from individual to collective cancer cell invasion. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 893–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chun T. H., Sabeh F., Ota I., Murphy H., McDonagh K. T., Holmbeck K., Birkedal-Hansen H., Allen E. D., and Weiss S. J. (2004) MT1-MMP-dependent neovessel formation within the confines of the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. J. Cell Biol. 167, 757–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rundhaug J. E. (2005) Matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 9, 267–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P. (2008) The molecular mechanisms of the thrombotic complications of atherosclerosis. J. Intern. Med. 263, 517–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troeberg L., and Nagase H. (2012) Proteases involved in cartilage matrix degradation in osteoarthritis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1824, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsey M. L., Iyer R. P., Zamilpa R., Yabluchanskiy A., DeLeon-Pennell K. Y., Hall M. E., Kaplan A., Zouein F. A., Bratton D., Flynn E. R., Cannon P. L., Tian Y., Jin Y.-F., Lange R. A., Tokmina-Roszyk D., Fields G. B., and de Castro Brás L. E. (2015) A novel collagen matricryptin reduces left ventricular dilation post-myocardial infarction by promoting scar formation and angiogenesis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 1364–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J. L., George S. J., Newby A. C., and Jackson C. L. (2005) Divergent effects of matrix metalloproteinases 3, 7, 9, and 12 on atherosclerotic plaque stability in mouse brachiocephalic arteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15575–15580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoulders M. D., and Raines R. T. (2009) Collagen structure and stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 929–958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emsley J., Knight C. G., Farndale R. W., Barnes M. J., and Liddington R. C. (2000) Structural basis of collagen recognition by integrin α2β1. Cell 101, 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer R. Z., Bella J., Mayville P., Brodsky B., and Berman H. M. (1999) Sequence dependent conformational variations of collagen triple-helical structure. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 454–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overall C. M. (2002) Molecular determinants of metalloproteinase substrate specificity: matrix metalloproteinase substrate binding domains, modules, and exosites. Mol. Biotechnol. 22, 51–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung L., Dinakarpandian D., Yoshida N., Lauer-Fields J. L., Fields G. B., Visse R., and Nagase H. (2004) Collagenase unwinds triple-helical collagen prior to peptide bond hydrolysis. EMBO J. 23, 3020–3030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stultz C. M. (2002) Localized unfolding of collagen explains collagenase cleavage near imino-poor sites. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 997–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nerenberg P. S., Salsas-Escat R., and Stultz C. M. (2008) Do collagenases unwind triple-helical collagen before peptide bond hydrolysis? Reinterpreting experimental observations with mathematical models. Proteins 70, 1154–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertini I., Fragai M., Luchinat C., Melikian M., Toccafondi M., Lauer J. L., and Fields G. B. (2012) Structural basis for matrix metalloproteinase 1-catalyzed collagenolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2100–2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manka S. W., Carafoli F., Visse R., Bihan D., Raynal N., Farndale R. W., Murphy G., Enghild J. J., Hohenester E., and Nagase H. (2012) Structural insights into triple-helical collagen cleavage by matrix metalloproteinase 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12461–12466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Díaz N., Suárez D., and Valdés H. (2013) Unraveling the molecular structure of the catalytic domain of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in complex with a triple-helical peptide by means of molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry 52, 8556–8569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han S., Makareeva E., Kuznetsova N. V., DeRidder A. M., Sutter M. B., Losert W., Phillips C. L., Visse R., Nagase H., and Leikin S. (2010) Molecular mechanism of type I collagen homotrimer resistance to mammalian collagenases. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22276–22281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nerenberg P. S., and Stultz C. M. (2008) Differential unfolding of α1 and α2 chains in type I collagen and collagenolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 382, 246–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fields G. B. (2013) Interstitial collagen catabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8785–8793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro S. D., Kobayashi D. K., and Ley T. J. (1993) Cloning and characterization of a unique elastolytic metalloproteinase produced by human alveolar macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 23824–23829 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhen E. Y., Brittain I. J., Laska D. A., Mitchell P. G., Sumer E. U., Karsdal M. A., and Duffin K. L. (2008) Characterization of metalloprotease cleavage products of human articular cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 2420–2431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taddese S., Jung M. C., Ihling C., Heinz A., Neubert R. H., and Schmelzer C. E. (2010) MMP-12 catalytic domain recognizes and cleaves at multiple sites in human skin collagen type I and type III. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 731–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu J. Y., Lyga A., Shi H., Blue M. L., Dixon B., and Chen D. (2001) Cloning, expression, purification, and characterization of rat MMP-12. Protein Expr. Purif. 21, 268–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertini I., Calderone V., Fragai M., Luchinat C., Maletta M., and Yeo K. J. (2006) Snapshots of the reaction mechanism of matrix metalloproteinases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45, 7952–7955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauer-Fields J. L., Sritharan T., Stack M. S., Nagase H., and Fields G. B. (2003) Selective hydrolysis of triple-helical substrates by matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18140–18145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhaskaran R., Palmier M. O., Lauer-Fields J. L., Fields G. B., and Van Doren S. R. (2008) MMP-12 catalytic domain recognizes triple helical peptide models of collagen V with exosites and high activity. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21779–21788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson M. P. (2013) Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 73, 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda M., Terasawa H., Sakakura M., Yamaguchi Y., Kajiwara M., Kawashima H., Miyasaka M., and Shimada I. (2003) Hyaluronan recognition mode of CD44 revealed by cross-saturation and chemical shift perturbation experiments. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43550–43555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhaskaran R., Palmier M. O., Bagegni N. A., Liang X., and Van Doren S. R. (2007) Solution structure of inhibitor-free human metalloelastase (MMP-12) indicates an internal conformational adjustment. J. Mol. Biol. 374, 1333–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schilder J., and Ubbink M. (2013) Formation of transient protein complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23, 911–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwahara J., and Clore G. M. (2006) Detecting transient intermediates in macromolecular binding by paramagnetic NMR. Nature 440, 1227–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fawzi N. L., Doucleff M., Suh J. Y., and Clore G. M. (2010) Mechanistic details of a protein-protein association pathway revealed by paramagnetic relaxation enhancement titration measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1379–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clore G. M. (2015) Practical aspects of paramagnetic relaxation enhancement in biological macromolecules. Methods Enzymol. 564, 485–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Battiste J. L., and Wagner G. (2000) Utilization of site-directed spin labeling and high-resolution heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance for global fold determination of large proteins with limited nuclear Overhauser effect data. Biochemistry 39, 5355–5365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bashir Q., Volkov A. N., Ullmann G. M., and Ubbink M. (2010) Visualization of the encounter ensemble of the transient electron transfer complex of cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scanu S., Foerster J. M., Ullmann G. M., and Ubbink M. (2013) Role of hydrophobic interactions in the encounter complex formation of the plastocyanin and cytochrome f complex revealed by paramagnetic NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 7681–7692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koppisetti R. K., Fulcher Y. G., Jurkevich A., Prior S. H., Xu J., Lenoir M., Overduin M., and Van Doren S. R. (2014) Ambidextrous binding of cell and membrane bilayers by soluble matrix metalloproteinase-12. Nat. Commun. 5, 5552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prior S. H., Fulcher Y. G., Koppisetti R. K., Jurkevich A., and Van Doren S. R. (2015) Charge-triggered membrane insertion of matrix metalloproteinase-7, supporter of innate immunity and tumors. Structure 23, 2099–2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Y., Marcink T. C., Sanganna Gari R. R., Marsh B. P., King G. M., Stawikowska R., Fields G. B., and Van Doren S. R. (2015) Transient collagen triple helix binding to a key metalloproteinase in invasion and development. Structure 23, 257–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fulcher Y. G., and Van Doren S. R. (2011) Remote exosites of the catalytic domain of matrix metalloproteinase-12 enhance elastin degradation. Biochemistry 50, 9488–9499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fields G. B. (2010) Synthesis and biological applications of collagen-model triple-helical peptides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 8, 1237–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vranken W. F., Boucher W., Stevens T. J., Fogh R. H., Pajon A., Llinas M., Ulrich E. L., Markley J. L., Ionides J., and Laue E. D. (2005) The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins 59, 687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwahara J., Tang C., and Marius Clore G. (2007) Practical aspects of 1H transverse paramagnetic relaxation enhancement measurements on macromolecules. J. Magn. Reson. 184, 185–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aguilar J. A., Nilsson M., Bodenhausen G., and Morris G. A. (2012) Spin echo NMR spectra without J modulation. Chem. Commun. 48, 811–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krugh T. R. (1976) Spin Label-Induced Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Relaxation Studies of Enzymes. in Spin Labeling: Theory and Applications (Berliner L. J., ed), pp. 339–372, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dominguez C., Boelens R., and Bonvin A. M. (2003) HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1731–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flippen-Anderson J. L., George C., Valle G., Valente E., Bianco A., Formaggio F., Crisma M., and Toniolo C. (1996) Crystallographic characterization of geometry and conformation of TOAC, a nitroxide spin-labelled Cα,α-disubstituted glycine, in simple derivatives and model peptides. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 47, 231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akaike H. (1973) in Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle (Petrov B. N., and Csaki F., eds) pp. 267–281, Akademiai Kiado, Budapest, Hungary [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daura X., Gademann K., Jaun B., Seebach D., van Gunsteren W. F., and Mark A. E. (1999) Peptide folding: when simulation meets experiment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 38, 236–240 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwieters C. D., and Clore G. M. (2001) The VMD-XPLOR visualization package for NMR structure refinement. J. Magn. Reson. 149, 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park S., Radmer R. J., Klein T. E., and Pande V. S. (2005) A new set of molecular mechanics parameters for hydroxyproline and its use in molecular dynamics simulations of collagen-like peptides. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1612–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berendsen H. J., Grigera J. R., and Straatsma T. P. (1987) The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 6269–6271 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hubbard S. J., and Thornton J. M. (1993) NACCESS, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University College London, London [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kukreja M., Shiryaev S. A., Cieplak P., Muranaka N., Routenberg D. A., Chernov A. V., Kumar S., Remacle A. G., Smith J. W., Kozlov I. A., and Strongin A. Y. (2015) High-throughput multiplexed peptide-centric profiling illustrates both substrate cleavage redundancy and specificity in the MMP family. Chem. Biol. 22, 1122–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eckhard U., Huesgen P. F., Schilling O., Bellac C. L., Butler G. S., Cox J. H., Dufour A., Goebeler V., Kappelhoff R., Keller U. A., Klein T., Lange P. F., Marino G., Morrison C. J., Prudova A., et al. (2016) Active site specificity profiling of the matrix metalloproteinase family: proteomic identification of 4300 cleavage sites by nine MMPs explored with structural and synthetic peptide cleavage analyses. Matrix Biol. 49, 37–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang C., Iwahara J., and Clore G. M. (2006) Visualization of transient encounter complexes in protein-protein association. Nature 444, 383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liang X., Arunima A., Zhao Y., Bhaskaran R., Shende A., Byrne T. S., Fleeks J., Palmier M. O., and Van Doren S. R. (2010) Apparent tradeoff of higher activity in MMP-12 for enhanced stability and flexibility in MMP-3. Biophys. J. 99, 273–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bertini I., Calderone V., Cosenza M., Fragai M., Lee Y. M., Luchinat C., Mangani S., Terni B., and Turano P. (2005) Conformational variability of matrix metalloproteinases: beyond a single 3D structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5334–5339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chung L., Shimokawa K., Dinakarpandian D., Grams F., Fields G. B., and Nagase H. (2000) Identification of the 183RWTNNFREY191 region as a critical segment of matrix metalloproteinase 1 for the expression of collagenolytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29610–29617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pelman G. R., Morrison C. J., and Overall C. M. (2005) Pivotal molecular determinants of peptidic and collagen triple helicase activities reside in the S3′ subsite of matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP-8): the role of hydrogen bonding potential of Asn188 and Tyr189 and the connecting cis bond. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2370–2377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Volkov A. N., Bashir Q., Worrall J. A., Ullmann G. M., and Ubbink M. (2010) Shifting the equilibrium between the encounter state and the specific form of a protein complex by interfacial point mutations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11487–11495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fan P., Li M. H., Brodsky B., and Baum J. (1993) Backbone dynamics of (Pro-Hyp-Gly)10 and a designed collagen-like triple-helical peptide by 15N NMR relaxation and hydrogen-exchange measurements. Biochemistry 32, 13299–13309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Madhan B., Xiao J., Thiagarajan G., Baum J., and Brodsky B. (2008) NMR monitoring of chain-specific stability in heterotrimeric collagen peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 13520–13521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stura E. A., Visse R., Cuniasse P., Dive V., and Nagase H. (2013) Crystal structure of full-length human collagenase 3 (MMP-13) with peptides in the active site defines exosites in the catalytic domain. FASEB J. 27, 4395–4405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palmier M. O., Fulcher Y. G., Bhaskaran R., Duong V. Q., Fields G. B., and Van Doren S. R. (2010) NMR and bioinformatics discovery of exosites that tune metalloelastase specificity for solubilized elastin and collagen triple helices. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 30918–30930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim Y. C., Tang C., Clore G. M., and Hummer G. (2008) Replica exchange simulations of transient encounter complexes in protein-protein association. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12855–12860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Doren S. R. (2015) Matrix metalloproteinase interactions with collagen and elastin. Matrix Biol. 44–46, 224–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sarkar S. K., Marmer B., Goldberg G., and Neuman K. C. (2012) Single-molecule tracking of collagenase on native type I collagen fibrils reveals degradation mechanism. Curr. Biol. 22, 1047–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fernandez-Catalan C., Bode W., Huber R., Turk D., Calvete J. J., Lichte A., Tschesche H., and Maskos K. (1998) Crystal structure of the complex formed by the membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase with the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2, the soluble progelatinase A receptor. EMBO J. 17, 5238–5248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Woskowicz A. M., Weaver S. A., Shitomi Y., Ito N., and Itoh Y. (2013) MT-LOOP-dependent localization of membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) to the cell adhesion complexes promotes cancer cell invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 35126–35137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arnold L. H., Butt L. E., Prior S. H., Read C. M., Fields G. B., and Pickford A. R. (2011) The interface between catalytic and hemopexin domains in matrix metalloproteinase-1 conceals a collagen binding exosite. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 45073–45082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lauer-Fields J. L., Tuzinski K. A., Shimokawa K.-i., Nagase H., and Fields G. B. (2000) Hydrolysis of triple-helical collagen peptide models by matrix metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13282–13290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.