Abstract

The DEK gene encodes a nuclear protein that binds chromatin and is involved in various fundamental nuclear processes including transcription, RNA splicing, DNA replication and DNA repair. Several cancer types characteristically over-express DEK at the earliest stages of transformation. In order to explore relevant mechanisms whereby DEK supports oncogenicity, we utilized cancer databases to identify gene transcripts whose expression patterns are tightly correlated with that of DEK. We identified an enrichment of genes involved in mitosis and thus investigated the regulation and possible function of DEK in cell division. Immunofluorescence analyses revealed that DEK dissociates from DNA in early prophase and re-associates with DNA during telophase in human keratinocytes. Mitotic cell populations displayed a sharp reduction in DEK protein levels compared to the corresponding interphase population, suggesting DEK may be degraded or otherwise removed from the cell prior to mitosis. Interestingly, DEK overexpression stimulated its own aberrant association with chromatin throughout mitosis. Furthermore, DEK co-localized with anaphase bridges, chromosome fragments, and micronuclei, suggesting a specific association with mitotically defective chromosomes. We found that DEK over-expression in both non-transformed and transformed cells is sufficient to stimulate micronucleus formation. These data support a model wherein normal chromosomal clearance of DEK is required for maintenance of high fidelity cell division and chromosomal integrity. Therefore, the overexpression of DEK and its incomplete removal from mitotic chromosomes promotes genomic instability through the generation of genetically abnormal daughter cells. Consequently, DEK over-expression may be involved in the initial steps of developing oncogenic mutations in cells leading to cancer initiation

Keywords: aneuploidy, cancer, chromosome instability, DEK, micronuclei, mitosis, mitotic defects

Abbreviations

- NIKS

Near-diploid immortalized keratinocytes

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- CCHMC

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- 7AAD

7-aminoactinomycin D

- MSO

Mitotic shake off

- NM

Non-mitotic.

Introduction

Mitosis is a tightly regulated process to ensure daughter cells obtain a complete, diploid set of chromosomes. Mitotic defects can lead to aneuploidy caused by chromosome segregation errors resulting in a loss or gain of one or more chromosomes.1 Aneuploidy is a remarkably common characteristic of tumor cells and has long been proposed as one of the first events to initiate tumorigenesis.2,3 Mitotic defects that cause aneuploidy usually lead to cell death; however, some cells continue to divide and pass on genetic abnormalities leading to an unstable karyotype and chromosome instability.4,5 Over the course of time, this chromosome instability can lead to the creation of an immortalized, proliferative, and highly metastatic population of cells.6 Thus, these mitotic abnormalities potentiate selection for a genetic advantage that supports tumorigenesis.7

Aneuploidy is caused by mitotic defects including centrosome amplification, a compromised mitotic check point, and abnormal mitotic spindle assembly.8,9 Daughter cells that arise from these defective mitoses may end up hypodiploid or hyperdiploid, depending on whether they have lost or gained a chromosome(s) respectively. Hyperdiploidy is more tolerated in cells and is often caused by problems with cytokinesis. Hyperdiploidy is often caused by problems during cytokinesis and is more tolerated by cells. Hypodiploidy, however, is a more common event but often results in cell death.10-13 These malsegregated chromosomes at anaphase may not end up in the nucleus of either daughter cell but remain extra-nuclear. These chromosomes eventually become enclosed by a nuclear membrane to form either nuclear buds or micronuclei. Micronuclei originate from chromosome fragments or whole chromosomes that fail to be incorporated in the daughter nuclei. This can result from lagging chromosomes in anaphase or unrepaired or misrepared double-stranded DNA breaks.8 Micronuclei are biomarkers of genotoxic events and chromosomal instability. Nuclear buds resemble micronuclei in that they are associated with chromosomal instability, but remain connected to the nucleus by nucleoplasmic material.8 Nuclear buds are thought to represent a mechanism by which cells remove amplified DNA and are therefore considered a marker of possible gene amplification.14 De-regulation of proteins involved in various stages of mitosis, including chromosome condensation, sister chromatid separation, and spindle assembly checkpoints, are common causes of chromosome instability and carcinogenesis.1 Multiple studies have shown that proteins that bind to and regulate chromatin structure during interphase also play important roles in mitosis. Examples include the high mobility group (HMG) box containing Structure Specific Recognition Protein (SSRP) family and the heterochromatin protein α (HP1α). These proteins are important for microtubule growth, the separation of sister chromatids and the completion of mitosis.15,16 DEK is a protein similar to the HMG, SSRP and HP1 families in that it functions as a chromatin topology modulator. DEK is a unique, non-histone, chromatin-associated protein that is evolutionarily conserved in higher eukaryotes, and represents the only member of its family. DEK can non-enzymatically bend DNA to introduce positive supercoils17 and functions as a histone 3.3 chaperone both in Drosophila18 and human cells.19 It also is involved in the maintenance of heterochromatin by directly interacting with HP1α to enhance its binding to H3K9Me3.20 DEK is over-expressed in numerous solid tumors and in some at the earliest stages of tumorigenesis.52 It is over-expressed through various mechanisms including increased transcription via the Rb/E2F pathway,21 6p22.3 Alifications,22-24 steroid hormone signaling,25 and mutations in its degradation machinery.26,27 DEK overexpression can inhibit cell death and differentiation as well as promote proliferation, and invasion in multiple types of cancer.28-32 During interphase, DEK plays a role in numerous nuclear processes including transcription, RNA processing, DNA repair, and chromatin organization.20,33-37 DEK is a highly modified protein, containing 57 potential phosphorylated sites and over 70 lysine residues with the potential to be poly ADP-ribosylated and ubiquitinated.26,27,38-40 Such modifications alter its ability to bind chromatin, re-localize, and carry out specific biological functions in a manner that remain poorly understood and have been studied primarily in cancer cells wherein DEK is over-expressed.41 For example, DEK is phosphorylated by CK2 during interphase and phosphorylation levels appear to peak in G1.38 In vitro, CK2 phosphorylation reduces the affinity of DEK for DNA and increases DEK self-multimerization.38

Previous studies have suggested that DEK associates with mitotic chromatin, potentially in a stage-dependent manner. For instance, using immunofluorescence and metaphase spreads, Kappes et al. 2001 observed that DEK is detectable on HeLa cell chromatin during metaphase and anaphase but appears to be absent in prometaphase. Two other reports confirm DEK association with chromatin in telophase cells,42,43 with one showing DEK absence from metaphase cells.43 Mass spectrometry of isolated mitotic chromosomes localizes DEK to the chromosome arm,44 but did not distinguish between the various stages of mitosis and may be a result of telophase association. Together, this data suggests that DEK localization may be regulated in cancer cells throughout mitosis. Such regulation, however, has not yet been closely examined in non-transformed cells, and, furthermore, the effect of cancer-related DEK over-expression on mitotic cells remains unknown.

Here we report, and build on, cancer-related ontology analyses of DEK which suggest major associations for DEK expression and mitotic processes. To determine the regulation of DEK during mitosis in non-transformed cells, which harbor relatively low DEK expression levels, we utilized a near-diploid immortalized keratinocyte cell line (NIKS)45 and murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). We found that endogenous DEK is largely absent from mitotic chromosomes from prophase through anaphase, but re-associates in telophase. Importantly, DEK overexpression leads to aberrant chromosomal retention of DEK through all stages of mitosis, and concomitantly increased the formation of micronuclei and hypodiploid populations. Micronuclei are strongly associated with mitotic errors and are a clinically relevant hallmark of cancer.46-50 We posit that DEK over-expression in normal cell populations contributes to mitotic abnormalities as a first step toward chromosomal instability, aneuploidy, and selection for oncogenic clones.

Results

The nuclear DEK oncogene is absent from mitotic chromosomes

In order to evaluate the relationship of DEK to other genes and biological processes across a broad series of biological contexts, we carried out gene expression profile analysis to identify genes whose expression was coordinately regulated with that of DEK. To do this we used 2158 tumor biopsy samples that had been subjected to gene expression microarray analysis by the International Genome Consortium Cancer Expression Profile project (Table S1). Somewhat unexpectedly, genes whose expression was very similar to that of DEK (Pearson correlation >0.485; 307 probesets), were highly enriched with respect to functional involvement in the mitotic cell cycle (Fig. 1A). This association indicated a potential relationship of DEK function with mitosis. To explore this, we used immunofluorescence to determine DEK localization throughout mitosis in NIKS cells, a near-diploid spontaneously immortalized keratinocyte cell line that harbors low DEK expression levels.30 While DEK is known to bind chromatin constitutively during interphase, we noted its marked absence from DNA during certain phases of mitosis (Fig. 1B and 1C). Specifically, DEK was not associated with chromatin from prophase through anaphase but was associated during telophase. DEK co-localized with chromosomes (DAPI) in over 95% of cells in telophase but in less than 10% of cells in anaphase (Fig. 1D). This was confirmed using 3 separate DEK antibodies (Fig. S1A and B), a finding which suggests that DEK dissociates from chromatin early in mitosis and re-associates prior to nuclear membrane formation.

Figure 1.

The nuclear DEK oncogene is absent from mitotic chromosomes. (A) Ontology analysis reveals mitosis is the most highly correlated biological process with DEK expression in tumors. Over 2000 tumor specimens were queried for transcriptional co-expression with the DEK oncogene using microarrays performed by the International Genome Consortium Expression Project for Ontology and connectivity to biological processes was carried out using ToppGene. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy (IF) of unsynchronized near diploid immortalized keratinocytes (NIKS) shows DEK co-localization with DAPI in a cell in interphase and telophase, but absent from DNA in a cell in prophase. NIKS were stained with DAPI to detect DNA, along with α tubulin to detect microtubules and the mitotic spindle, and a DEK specific antibody (Aviva Systems Biology). Arrowheads point to cells wherein DEK co-localizes with chromatin (white) or there is no co-localization (yellow). (C) IF was carried out as in (B) with examples of DEK localization throughout mitosis. (D) Quantification of (C) not including prometaphase. Over 140 mitotic cells were counted across 4 cover slips from 3 independent experiments with at least 20 cells counted per mitotic stage. Twenty interphase cells were counted per coverslip.

DEK protein levels are drastically reduced in mitotic cells

Since DEK was largely absent from DNA during mitosis, we investigated its regulation at the protein level in cells that were either chemically synchronized or enriched for mitotic cells by mitotic shake-off. Asynchronous NIKS were compared to cells synchronized with mimosine or serum starvation for arrest in G1, with thymidine and aphidicolin for arrest in S, and with nocodazole for arrest in G2/M. Cells obtained from mitotic shake-off (MSO) were compared to their respective adherent control cells referred to as non-mitotic. Arrest in the predicted phase of the cell cycle was verified by flow cytometry in each case (Fig. 2A), with the proportion of cells in G1, S and G2/M quantified in Figure 2B. Interestingly, while DEK protein levels were relatively constant upon G1 and S arrest as previously reported,51 DEK protein levels decreased dramatically in mitotically enriched cells following mitotic shake off (Fig. 2C). This was confirmed with 3 other DEK antibodies (data not shown). G2/M arrest with nocodazole also decreased DEK protein but to a lesser extent as would be expected due to fewer cells arrested in G2/M (Fig. 2 A and B). It is likely the small amount of DEK remaining in the MSO is from cells in telophase. This data suggests that in early prophase, DEK is degraded or otherwise removed from cells.

Figure 2.

DEK protein is sharply reduced in mitotic cells. NIKS were treated with mimosine or serum starvation to induce cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase, with a combination of thymidine and aphidicolin to induce cell cycle arrest in S phase, and with nocodazole or underwent a mitotic shake off to enrich for cells in G2/M phase. Mitotic shake off occurred after treatment with colcemid 20 nM for 24 hours. (A) Cellular arrest in the expected phase of the cell cycle was verified by flow cytometry. Cells were pulsed with EdU for 2 hours then stained with 7AAD to determine DNA content. (B) Percent cells from the gated areas of G1, S, and G2/M were quantified from (A). (C) Cells were treated as in (A) and subjected to protein gel blot analysis to detect DEK protein (Aviva Systems Biology) levels throughout the cell cycle.

Overexpression of DEK stimulates its aberrant retention on mitotic chromosomes

DEK is highly expressed across multiple human tumor types, and expression ontology data in Figure 1A links DEK over-expression to mitosis. We therefore set out to determine the consequences of DEK overexpression on its dynamic chromatin binding pattern during mitosis. To this end, DEK was overexpressed in NIKS using a previously published30 retroviral vector shown to be functional in vitro.37 DEK was expressed to a level comparable to that observed in cancer cells (Fig. S2A). The co-localization of DEK with DNA was then monitored by immunofluorescence microscopy. Interestingly, DEK protein over-expression stimulated DEK association with prophase, metaphase and anaphase chromosomes, when compared to the corresponding empty vector transduced cells (Fig. 3A-D). DEK overexpression in R780-DEK transduced cells was verified by western blot analysis (Fig. 3C). Taken together, DEK over-expression induces abnormal DEK retention on mitotic chromosomes.

Figure 3.

DEK overexpression induces its aberrant retention on mitotic chromosomes. (A and B) NIKS were transduced with a GFP-marked R780 retroviral vector encoding wild-type human DEK. The R780 backbone vector was used as a control. IF images of NIKS in mitosis expressing either control R780 vector (A) or R780-DEK vector (B) reveal DEK over-expression stimulates DEK retention on mitotic chromosomes. (C) Western blot analysis confirms DEK overexpression. (D) Quantification of (A and B). Over 140 mitotic cells were counted (at least 20 per mitotic stage) in 2 independent experiments for the R780 empty vector and over 200 mitotic cells for R780-DEK in 3 independent experiments.

A DEK-GFP fusion protein hyper-associates with mitotic chromosomes

To follow DEK localization during cell division spatially and temporally, we utilized a DEK-GFP fusion protein for live cell imaging (Fig. 4A). Expression levels of the DEK-GFP fusion protein are about twice that of endogenous DEK (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, we found that compared to endogenous DEK protein (Fig. 1D), the DEK-GFP fusion protein more frequently associated with DNA throughout mitosis by IF (Fig. 4C) and live cell imaging (Fig. 4D and Movie S1). This association was detected both by viewing the DEK-GFP protein directly and using a DEK antibody (Aviva Systems Biology) (Fig. S3A). The observed chromatin retention of DEK-GFP may be due, in part, to the overexpression of the fusion protein. Of interest, we noticed that cells with robust DEK-GFP expression frequently exhibited mitotic defects such as lagging chromosomes and anaphase bridges (Fig. 4D, Fig. S3B, and Movies S2 and S3). Therefore, the retention of DEK on chromatin throughout mitosis may be detrimental to the fidelity of cell division.

Figure 4.

A DEK-GFP fusion protein is retained on mitotic chromosomes and associates with lagging chromosomes. (A) Schematic of the DEK-GFP fusion protein expressed from a pLentiLox vector backbone. GFP is fused to the C-terminus of the 375 amino acid protein DEK. (B) NIKS were transduced with DEK-GFP or empty control GFP vector and were sorted for GFP expression. DEK-GFP expression was confirmed by western blot analysis using a DEK antibody (BD Biosystems). (C) Quantification of interphase and mitotic cells with chromatin-associated DEK-GFP compared to control GFP protein using a GFP antibody for IF. (D) Mitotic defects were commonly observed in the DEK-GFP expressing NIKS by live cell imaging. Pictures were taken of the same cell in metaphase, anaphase and telophase. DEK-GFP remains bound to the DNA throughout mitosis and is detected on an anaphase bridge that results in a nuclear bud. Arrows point to improperly segregating chromosome(s).

DEK expression that is sufficient to cause aberrant mitotic localization induces micronucleus formation

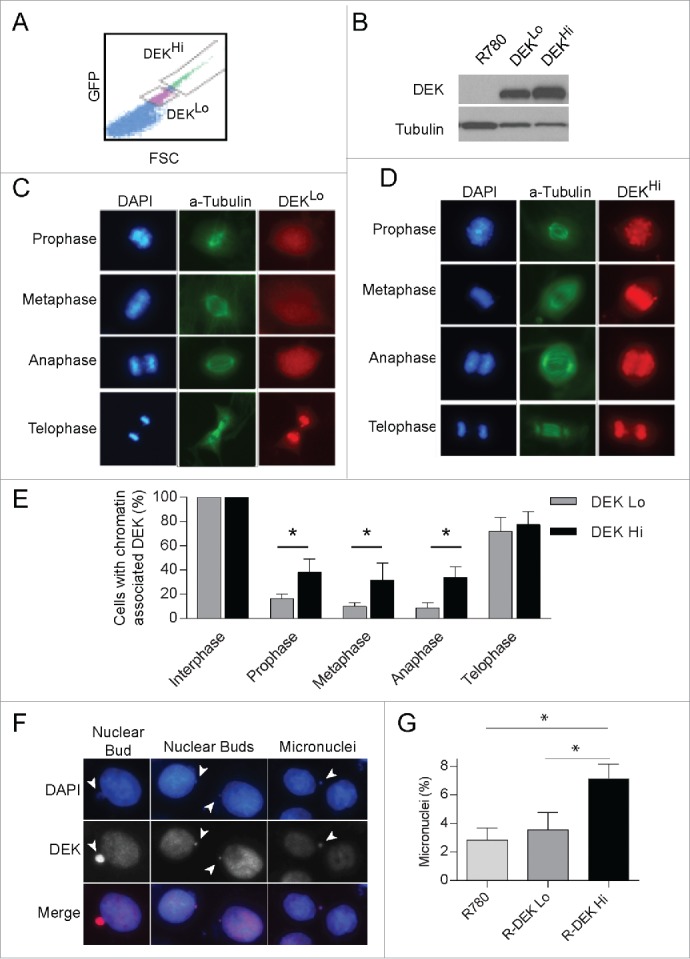

Since exogenous expression of DEK stimulates its inappropriate association with mitotic chromosomes, it is possible a threshold level of DEK is required for this effect. To determine this, we utilized Dek−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts either control transduced or complemented retrovirally with low or high levels of human DEK protein. Cells were sorted by low or high IRES-driven GFP expression (Fig. 5A), and DEK protein levels were verified by protein gel blot analysis (Fig. 5B). Low GFP detection correlated with low DEK expression (DEKLo) and high GFP detection correlated with high DEK expression (DEKHi). As was observed with endogenous DEK, we found DEK in DEKLo expressing MEFs is generally absent from mitotic chromosomes until telophase, and always bound to DNA in interphase (Fig. 5C). However, the DEKHi MEFs showed significant increases in DEK association with chromatin in prophase, metaphase and anaphase compared to DEKLo MEFs suggesting DEK is not as efficiently removed from the chromatin in these cells (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, we observed DEK association with lagging genetic material in the DEKHi expressing MEFs (Fig. S4A) similar to that observed in NIKS expressing the DEK-GFP fusion protein (Fig. 4D). We also consistently observed DEK co-localization with micronuclei and nuclear buds (Fig. 5F). This suggested that aberrant retention of DEK on mitotic chromosomes due to high DEK expression may result in mitotic defects. Therefore, we investigated if DEK levels sufficient to cause DEK retention on mitotic chromosomes resulted in the formation of micronuclei. To this end micronuclei were counted by coverslip IF and of significance, DEKHi expressing cells had an increased incidence of micronuclei compared to empty vector and DEKLo expressing cells (Fig. 5G). Together this data supports that high DEK expression promotes aberrant chromatin binding throughout mitosis and leads to mitotic defects that result in micronucleus formation.

Figure 5.

High DEK expression, sufficient to cause mitotic retention, stimulates micronucleus formation. (A) Immortalized Dek−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were transduced with the R780-DEK or control retroviral vector. The cells were sorted for low vs. high DEK expression by gating on low versus high GFP expression. (B) Western blot analysis of sorted cells verifies low and high DEK protein levels as expected. (C) IF reveals DEKLo expression in Dek−/− MEFs results in DEK localization similar to that of endogenous DEK during mitosis. (D) DEKHi expression in MEFs stimulates abnormal DEK association with mitotic chromosomes throughout mitosis. (E) Quantification of (C and D) as before from 3 independent experiments, comparing DEK localization in DEKLo and DEKHi expressing mitotic cells. (F) DEK associates with extra-nuclear chromosome fragments such as nuclear buds and micronuclei in DEKHi MEFs. Arrowheads point to extra-nuclear DNA. (G) DEKLo and DEKHi MEFs were plated on coverslips and micronuclei were quantified from images using imageJ to count a total of 500–2000 cells.

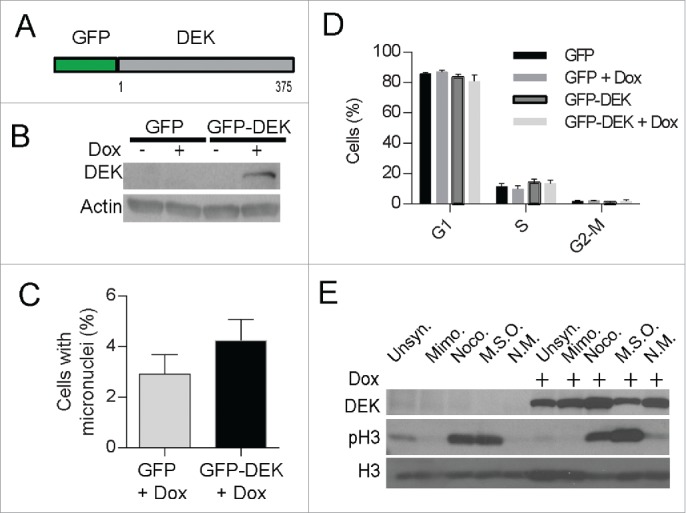

Since micronuclei develop from abnormal chromosome segregation during mitosis, the more rounds of cell division, the more chances to develop micronuclei. With regard to DEK, its over-expression is known to increase proliferation in certain scenarios, and this could potentially increase micronuclei indirectly by driving cell division. To consider this scenario, we examined if acute DEK overexpression was sufficient to induce micronuclei formation in the absence of proliferative gains. We utilized a doxycycline inducible GFP-DEK fusion construct (Fig. 6A). Of note, GFP is fused to the N-terminus of DEK and unlike DEK-GFP has chromatin association patterns similar to that of wild type DEK (Fig. S5A). The cells were treated with doxycycline for 48 hours to express GFP-DEK (Fig. 6B). This brief period of DEK over-expression was sufficient to increase micronucleus formation by ∼1.5-fold as quantified by coverslip IF (Fig. 6C) and flow cytometry (Fig. S5B). Importantly, the increase in micronuclei formation occurred in the absence of increased proliferation (Fig. 6D) thus ruling out more cell divisions as the cause of micronucleus formation and suggesting a more direct effect by DEK. Lastly, the GFP-DEK protein was detected in a mitotic shake off (Fig. 6E) suggesting a portion of this fusion protein is retained on mitotic chromosomes presumably due to crossing the threshold level of DEK that can be removed from chromosomes prior to prophase.

Figure 6.

Acute, inducible expression of DEK induces micronuclei formation. Dek−/− MEFs were transduced with a doxycycline-inducible GFP-DEK fusion protein (A) encoded by a TRIPZ vector and selected with puromycin. The empty GFP pTRIPZ vector was used as a control. (B) Western blot analysis confirmed fusion protein expression at 48 hours after the addition of doxycycline to GFP-DEK transduced cells. Cells from (B) were fixed on coverslips and micronuclei were quantified by IF as before (C). (D) GFP-DEK expression does not alter cell cycle progression. GFP and GFP-DEK transduced cells, in the presence or absence of dox for 48 hours, were pulsed with EdU for 2 hours and subjected to cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry. Cells in each stage of the cell cycle were quantified from duplicate experiments. (E) The GFP-DEK fusion protein is retained in mitotic cells. Western blot analysis of GFP-DEK cells with and without doxycycline and arrested in G1 with mimosine or mitosis with nocodazole, or underwent a mitotic shake off (MSO) confirms an increase of GFP-DEK in mitotic cells (NM=non mitotic). A DEK specific antibody was utilized (BD Biosystems) as well as a pH3 antibody to detect cells in mitosis.

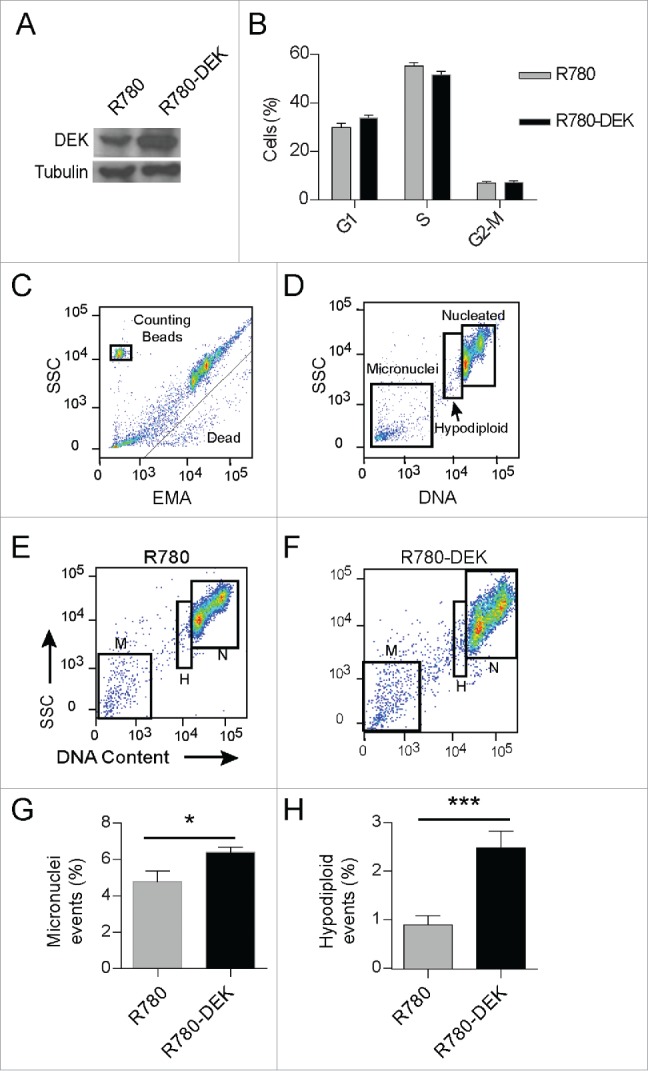

DEK overexpression increases the incidence of hypodiploidy and micronuclei in cancer cells

Our ontology analysis links DEK expression patterns to mitotic genes across various cancer types. Therefore, to determine the effects of DEK over-expression on mitosis in transformed cells, we used the CCHMC-SCC152 cell line which was cultured from a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and harbors relatively low DEK expression (Fig. S2A). DEK overexpression was driven from the R780 vector as before (Fig. 7A), and did not alter cell cycle profiles in the respective population (Fig. 7B). Next we employed a flow cytometry based assay to quantify micronuclei in R780-DEK versus R780 cells. In this assay, dead and dying cells are identified and removed from analysis by ethidium monoazide (EMA) staining (Fig. 7C). Viable cells were lysed, releasing nucleated DNA and micronuclei. Nuclei were analyzed for DNA content; thus aneuploidy including hypodiploidy and hyperdiploidy, as well as micronucleus formation can be clearly identified and distinguished from each other. Less than 5% of all events were micronuclei in the empty vector control cells (Fig. 7D, E and G). However, DEK over-expression significantly increased micronucleus formation to ˜7% (P value 0.036) (Fig. 7F and G), approaching the percentage observed by that of known micronuclei inducing drugs (Fig. S6A and B). Interestingly, DEK also increased the hypodiploid population of cells by more than 2-fold (P-value 0.0004) which is comparable to that of colcemid, a known aneugen (Fig. 7H and Fig. S6A). Hypodiploidy is a characteristic consequence of aneugen exposure which causes missegregation of chromosomes, often by interfering with the mitotic machinery, and results in aneuploidy. Therefore, DEK overexpression may be acting as an aneugen and increases both the incidence of hypodiploidy and micronucleus formation in cancer cells.

Figure 7.

DEK over-expression increases the incidence of hypodiploidy and micronuclei in cancer cells. CCHMC-SCC1 cells are a squamous cell carcinoma line isolated from a primary tonsillar tumor. (A) DEK was over-expressed by R780-DEK compared to control R780 transduction, and expression levels were confirmed by protein gel blot analysis. (B) DEK overexpression did not increase proliferation in C-SCC1 cells. Cells were pulsed with EdU for 2 hours, and then stained with 7AAD to determine DNA content. (C-F) CCHMC-SCC1 cells treated as in (A) were used for micronuclei detection by a flow cytometry based assay. (C) DNA from dead or dying cells was gated out on EMA positivity. (D) Remaining DNA that was stained with SYTOX Red was gated on DNA content to reveal G1, G2/M nuclei (labeled nucleated or N), a hypo-diploid population of nuclei (labeled H), and micronuclei (M). ((E)and F) Each population of events was gated in FlowJo to compare empty vector control cells (E) with DEK overexpressing cells (F). (G and H) DEK over-expression increased both micronucleus formation (G) and the hypo-diploid population of cells (H). Numbers represent 5 replicate cell cultures from 2 independent experiments.

Discussion

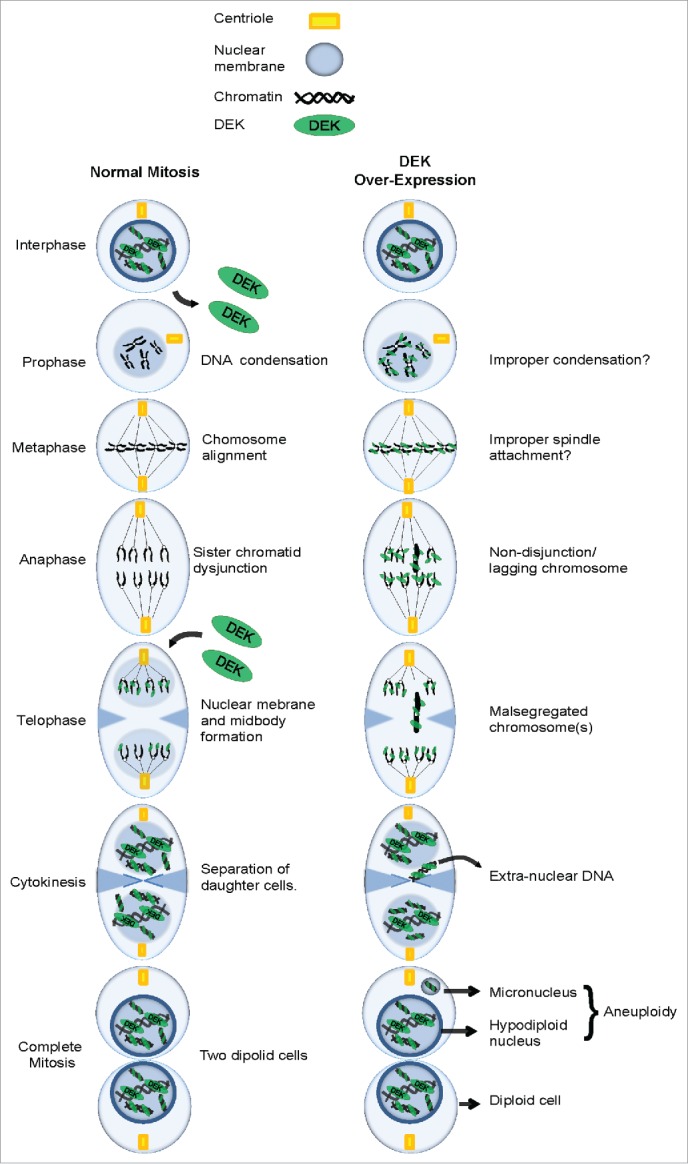

The DEK oncogene has been implicated in multiple oncogenic phenotypes including tumor initiation, promotion and progression. However, molecular studies of DEK oncogenicity have mostly focused on roles of DEK in interphase cells, where DEK is constitutively bound to chromatin, and functions in transcription, replication and DNA repair.18,31,36,53-57 In this study we investigated the regulation of DEK in mitosis and found that endogenous DEK is removed from chromatin in early prophase and re-associates with chromatin in telophase as outlined in Figure 8A. Importantly, DEK over-expression leads to its aberrant retention on chromatin throughout mitosis (Fig. 8B) and contributes to mitotic defects and chromosome instability in normal and transformed cells.

Figure 8.

Working model: The consequence of DEK overexpression in mitosis. (A) A schematic detailing the various stages of mitosis including the loss of DEK association with chromatin in prophase and re-association in telophase. (B) The over-expression of DEK leads to its aberrant retention on mitotic chromosomes throughout mitosis. The end result is malsegregated chromosomes that end up as micronuclei in daughter cells.

Previous studies of DEK expression and localization in mitosis agree with our findings that DEK co-localizes with DNA during telophase.42,43,51 However, we find that DEK is mostly absent from chromosomes in prophase, metaphase and anaphase. This finding is in contrast to a previous report51 showing DEK bound to metaphase chromosomes. This discrepancy may be due to previous results being obtained from cells being treated with nocodazole, compared to our studies carried out in untreated cells. In support of this, nocodazole treated cells harbored increased DEK or GFP-DEK protein levels when compared to cells after mitotic shake off (Fig. 2D, Fig. 6G). While nocodazole clearly arrests cells in mitosis it is also known to cause DNA damage58-61, and DEK contributes to DNA damage repair.37 Thus DEK may be retained on chromatin in nocodazole treated cells in order to support the DNA damage response and repair. Furthermore, we have observed instances wherein endogenous DEK is retained on mitotic chromosomes, and these may also be related to DNA damage. In fact, the dynamic pattern of DEK localization in mitosis resembles that of many proteins involved in DNA damage repair which are removed from chromatin during mitosis such as Rad51, DNA-PK, FAND2 and Bloom complex components.62-65

It is important to point out that while the majority of DEK is absent from mitotic chromosomes until telophase, a greater proportion of the fusion proteins, and particularly the C-terminal DEK-GFP fusion, were in fact prominent on mitotic chromosomes. This increased retention is likely due to the overexpression of DEK. However we cannot rule out the possibility that the GFP fusion is more directly involved in causing aberrant retention, or conversely, amplifies the small proportion of DEK that remains on the DNA during mitosis under normal circumstances. Regardless, high levels of wild type DEK protein expression increase its retention on mitotic chromosomes compared to low or endogenous levels, suggesting saturation of unknown mechanisms of DEK dissociation or removal. Perhaps an abundance of DEK causes DEK aggregates which exhibit greater affinity for DNA or precludes appropriate post-translational modification.42 While mitosis-related DEK modifications are unknown, a large number of proteins are phosphorylated during mitosis for subsequent relocalization or degradation.66 DEK is known to be phosphorylated by CK2 in interphase cells and DEK phosphorylation decreases its affinity for DNA. While CK2 phosphorylates some substrates in mitosis,67-70 DEK is not known to be one of them. DEK also carries predicted phosphorylation sites for both aurora kinase A and B as well as polo like kinases which regulate proper entry, progression and exit from mitosis and may be regulating the removal of DEK from chromosomes.

Irrespective of potential regulation by mitotic kinases, DEK over-expression leads to aberrant chromatin retention and increases mitotic defects and the formation of micronuclei (Fig. 8b). This occurred in both non-transformed fibroblasts as well as in a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma line, and was independent of cellular proliferative differences. The enhanced capabilities of the flow cytometry micronuclei detection assay also enabled the detection a hypo-diploid population of cells. An increase in hypodiploidy is a characteristic of aneugens which interfere with chromosome segregation resulting in chromosomal gain or loss. Therefore, high DEK expression is expected to contribute to chromosome instability by ultimately stimulating hypodiploidy, a form of aneuploidy. Critically, this effect was demonstrated to occur upon short term induction of DEK, suggesting DEK overexpression may directly impact chromosome segregation in mitosis. While most hypodiploid cells succumb to cell death, hypodiploidy can potentiate the development of a select subpopulation of cells with enhanced survival capacity and thus aggressive behavior. Taken together, the dynamic DEK association with mitotic chromatin supports functional roles for DEK in this process, and its over-expression is sufficient to cause mitotic abnormalities that are hallmarks and causes of cellular transformation and carcinogenesis.

Methods & Materials

Cell culture

MEFs derived from Dek+/+ and Dek−/− mice were previously described.37 MEFs were maintained in high glucose DMEM (http://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/11965118) containing 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine (http://cellgro.com/products/cell-culture-reagents/amino-acids-vitamins/ l-glutamine-liquid-2.html), 100 mM MEM non-essential amino acids (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/11140050), 0.055 mM b-mercaptoethanol (Midwest Scientific- 0482–1) and 10 mg/ml gentamycin (http://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/15710064). Spontaneously immortalized near-diploid human keratinocyte cell line (NIKS)45 were maintained in F-media, which is 3 parts Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium to 1 part Ham's F12 media (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/11765070) supplemented with the following components: 5% fetal bovine serum, 24 ug/ml adenine, 8.4 ng/ml cholera toxin (http://www.labome.com/product/EMD-Millipore/227036–1MG.html), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/e4127), 2.4 μg/ml hydrocortisone (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/h0888), 5 μg/ml insulin, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/15140122), and 0.2% fungizone (http://www.omegascientific.com/shop/fungizone-amphotericin-b/). CCHMC-SCC1 head and neck cancer cells were cultured from a tumor obtained with IRB approval at the time of surgical resection.52 Cells were placed on irradiated J2–3T3 mouse fibroblasts and were maintained in F-media. Once robust growth was observed they were removed from feeders and adapted to and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 1% hydrocortisone, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.2% fungizone.

EdU incorporation and cell-cycle analysis by flow cytometry

NIKS were grown to 70–80% confluency in 6 well plates and pulsed with 10 mM EdU for 2 hours before collection by trypsinization. Cells were prepared using the Click-iT® EdU Alexa Fluor® 647 Imaging Kit (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/C10424) according to manufacturer specifications. DNA content was determined using 7-AAD (http://www.bdbiosciences.com/us/applications/research/apoptosis/ancillary-products/7-aad/p/559925) to stain DNA and cells were analyzed on a BD FACSCanto analyzer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Cell synchronization

500,000 cells were plated in 6-well plates and synchronized at various stages of the cell cycle: For G1 arrest, cells were treated with mimosine (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/m0253), 400 uM, 24 hours, or placed in serum free F-media with no insulin, adenine or EGF for 48 hours. For S phase synchronization cells were place in thymidine (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/t1895), 2 ug/ml, 12 hours followed by release for 10 hours followed by either another round of thymidine or aphidicolin (http://www.pfstar.com/Fisher-Scientific-BP615–1-APHIDICOLIN-1MG-EA_p_274776.html), 500 uM for 12 hours. Aphidicolin was also used alone. For mitotic arrest, cells were treated with nocadazole (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/m1404), 2 ug/ml, 24 hours or colcemid (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/15212012), 20 nM, 16 hours, or subjected to a mitotic shake off.

Mitotic shake off

Cells were grown to 80% confluency on 15 cm plates then washed with PBS. NIKS were treated with 0.05% trypsin (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/25300054) for 1–5 minutes until mitotic cells appeared loosely attached. Cells were rinsed with PBS and the floating cells were collected, centrifuged and lysed as described below for western blot or RNA analysis. The non-mitotic cells, which remained attached to the plate, were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/25200114), collected and lysed as the control cells. MEFs were treated as above except trypsin exposure was limited to 30 seconds in 0.05% trypsin.71

Plasmid and viral constructs and transductions

A retroviral R780 vector was used to over-express human DEK, and cells were sorted on GFP expression from an IRES signal as previously published.29 The pLentilox vector is lentiviral and contains full-length DEK with GFP fused to the C-terminus and was a gift from Ferdinand Kappes and previously described20 The pTRIPZ vector is a doxycycline inducible vector containing full length DEK with GFP fused to the N-terminus. First, the tRFP cassette of the pTRIPZ vector was replaced by a new MCS, where the eGFP cDNA derived from the pEGFP-N1 vector was inserted via the new XhoI/SnaBI sites. Next, the DEK cDNA was cloned into the pTRIPZ-EGFP vector, digested with EcoRI/SnaBI via a 3-fragment ligation: DEK bp 1–471 was isolated by restriction digest of the pGEX4T1-DEK vector using EcoRI/NsiI; DEK bp 472–1125 was produced from the pGEX4T1-DEK vector via PCR using the primer pair 5′-GATGCTTAAGCTTCTCGAGGCCACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAG-3′ and 5′-GCGGTACGTAGCGGCCGCTCAAGAAATTAGCTCTTTTACAG-3′ and digestion with NsiI/SnaBI. The resulting pTRIPZ-EGFP-DEK plasmid was analyzed by sequencing. Cells were transduced at 50% confluency. For retroviral infections, cells were incubated with virus for 4 hours in medium containing 2 mg/ml of polybrene (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/h9268), then washed and overlaid with fresh medium. Transduced cells were sorted for GFP and expanded as a polyclonal population. Lentiviral infections were conducted in the same way except that the cells were incubated with virus for 16 hours and selected and maintained in 1 ug/ml puromycin as previously described.20 Doxycline (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/d9891) was added to media for the indicated times at 1 ug/ml. The MIEG-His-Flag-DEK (GenScript Piscataway, NJ) construct was developed from the pMIEG3 retroviral vector, a kind gift from Dr. David Williams (Children's Hospital Boston, MA), and has been described earlier.72 The EcoRI-His(6)-FLAG-DEK-XhoI sequence, CCGGAATTCGGCGGCCGCGCCACCATGCATCACCATCACCATCACGACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAGATGTCCGCCTCGGCCCCTGCTGCGGAGGGGGAGGGAACCCCCACCCAGCCCGCGTCCGAGAAAGAACCCGAAATGCCCGGTCCCAGAGAGGAGAGCGAGGAGGAAGAGGACGAGGACGACGAGGAGGAGGAGGAGGAGGAAAAAGAAAAGAGTCTCATCGTGGAAGGCAAGAGGGAAAAGAAAAAAGTAGAGAGGTTGACAATGCAAGTCTCTTCCTTACAGAGAGAGCCATTTACAATTGCACAAGGAAAGGGGCAGAAACTTTGTGAAATTGAGAGGATACATTTTTTTCTAAGTAAGAAGAAAACCGATGAACTTAGAAATCTACACAAACTGCTTTACAACAGGCCAGGCACTGTGTCCTCATTAAAGAAGAATGTGGGTCAGTTCAGTGGCTTTCCATTTGAAAAAGGAAGTGTCCAATATAAAAAGAAGGAAGAAATGTTGAAAAAATTTAGAAATGCCATGTTAAAGAGCATCTGTGAGGTTCTTGATTTGGAGAGATCAGGTGTAAATAGTGAACTAGTGAAGAGGATCTTGAATTTCTTAATGCATCCAAAGCCTTCTGGCAAACCATTGCCGAAATCTAAAAAAACTTGTAGCAAAGGCAGTAAAAAGGAACGGAACAGTTCTGGAATGGCAAGGAAGGCTAAGCGAACCAAATGTCCTGAAATTCTGTCAGATGAATCTAGTAGTGATGAAGATGAAAAGAAAAACAAGGAAGAGTCTTCAGATGATGAAGATAAAGAAAGTGAAGAGGAGCCACCAAAAAAGACAGCCAAAAGAGAAAAACCTAAACAGAAAGCTACTTCTAAAAGTAAAAAATCTGTGAAAAGTGCCAATGTTAAGAAAGCAGATAGCAGCACCACCAAGAAGAATCAAAACAGTTCCAAAAAAGAAAGTGAGTCTGAGGATAGTTCAGATGATGAACCTTTAATTAAAAAGTTGAAGAAACCCCCTACAGATGAAGAGTTAAAGGAAACAATAAAGAAATTACTGGCCAGTGCTAACTTGGAAGAAGTCACAATGAAACAGATTTGCAAAAAGGTCTATGAAAATTATCCTACTTATGATTTAACTGAAAGAAAAGATTTCATAAAAACAACTGTAAAAGAGCTAATTTCTTGACTCGAG, was created by flanking DEK in the R780-DEK vector with primers to introduce EcoRI and in-frame His(6)-FLAG-Stop-XhoI sequence. The PCR product was produced, cut, and inserted into the EcoRI and XhoI sites in the pMIEG vector by GenScript.

Western blot analyses

Cells were washed with PBS and whole cell lysates were harvested with RIPA buffer (1% Triton, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.16 M NaCl, 10 mmol/L Tris pH 7.4, and 5 mmol/L EDTA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (BD PharMingen- 554779) and analyzed as described previously.30 Primary antibodies used for DEK were as follows: DEK (1:1000; http://www.bdbiosciences.com/us/reagents/research/antibodies-buffers/cell-biology-reagents/cell-biology-antibodies/purified-mouse-anti-human-dek-2dek/p/610948), DEK-Aviva (1:1000; http://www.avivasysbio.com/dek-antibody-n-terminal-region-p100637-t100.html), DEK antibody K-877 (1:10,000, a polyclonal antibody; gift from Ferdinand Kappes), a DEK cocktail including the 3 described antibodies and DEK polyclonal rabbit from Proteintech (1:1000; http://www.ptglab.com/Products/DEK-Antibody-16448–1-AP.htm). Other antibodies include α tubulin (1:5000; http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/t9026), pH3-S10 (1:1000; http://www.cellsignal.com/product/productDetail.jsp?productId=9701), H3 (1:1000; http://www.cellsignal.com/products/primary-antibodies/9715), pan-actin (1:20,000; a gift from James Lessard, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA). Membranes were exposed to enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (http://www.perkinelmer.com/catalog/category/id/detection%20of%20horseradish%20peroxidase)

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were plated onto 100 mg/ml poly-D-lysine coated coverslips, and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. Coverslips were incubated in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 3 min, blocked with 5% normal goat serum, and incubated with primary antibody for 1 h at 37°C. Antibody dilutions were as follows: DEK-BD (1:60; BD Biosciences), DEK-Aviva (1:60 Aviva systems biology), DEK-K-877 (1:500), GFP (1:500; http://www.abcam.com/gfp-antibody-chip-grade-ab290.html) and α tubulin (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich). Coverslips were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 or 568 (1:1000; https://www.lifetechnologies.com/us/en/home/brands/molecular-probes/key-molecular-probes-products/alexa-fluor.html?icid=fr-alexa-main) and mounted onto glass slides with DAPI Vectashield mounting media (https://www.vectorlabs.com/catalog.aspx?prodID=428). Cell staining was analyzed using a Leica DMI6000 microscope (Leica) and Openlab5 software (Improvision). DEK retention on mitotic chromosomes was quantified in at least 20 cells per phase of mitosis and done in duplicate or triplicate experiments where indicated. Images of varying magnifications were cropped in Microsoft PowerPoint and resized to fit in a specific window and therefore are not representative of size. Micronuclei quantification was analyzed using ImageJ by counting micronuclei and the total number of cells from 20× magnification images. A total of 500 to 1000 cells were analyzed per cell line. The standard error was calculated from the percent of micronuclei per cell across all photos.

Live cell imaging

Cells were plated in a 35 mm-60 mm dish. 20 mM of HEPES (http://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/15630080) pH 7.4 was added to the media as well as 10 uM trolox (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/aldrich/238813). Media was overlaid with 1.5 mL mineral oil (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/fluka/1443952) to prevent evaporation. The dish was set inside an incubator attached to the microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200 M) set to 37°Celsius. Pictures were taken every 4 minutes through the FITC channel. Videos were made using ImageJ and converted to AVG files.

Quantification of micronuclei by flow cytometry

Micronucleus staining was adapted from previously published protocols.73–75 In brief, CCHMC-SCC1 or MEFs were plated in 6-well or 12-well plates and grown to 50% confluency. At this time cells were either untreated or treated with the indicated drugs: 1 ug/ml bleomycin (http://www.labome.com/product/EMD-Millipore/203408–100MG.html), 1 uM etoposide (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/e1383), or 20 nM colcemid (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/15212012) for 16 hours. Cells were placed on ice for 20 minutes. Media was then aspirated and cells were covered with 0.0125 mg/ml ethidium monoazide bromide (EMA) (http://biotium.com/product/ethidium-monoazide-bromide-ema/) in PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum. EMA was photoactivated for 30 minutes, one foot below a 60 W bulb on ice. Cells were washed twice with PBS then covered in a non-ionic detergent called “Lysis Solution 1.” “Lysis solution 1” was prepared with deionized water, and consisted of 0.584 mg /ml NaCl (http://shop.midsci.com/productdetail/M50/IB07070/Sodium_Chloride_(NaCl),_500g/), 1 mg/ml sodium citrate (http://www.amresco-inc.com/CITRIC-ACID-SODIUM-SALT-0101.cmsx), 0.3 μl /ml IGEPAL (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/i8896), 0.5 mg/ml RNAse A (https://www.qiagen.com/us/products/catalog/sample-technologies/dna-sample-technologies/plasmid-dna/rnase-a/) and 0.4 μM SYTOX Red (https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/S34859), followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 hour in the dark. Then “Lysis Solution 2” was prepared with deionized water, 85.6 mg/ml sucrose (http://www.fishersci.com/ecomm/servlet/fsproductdetail_10652_753078__-1_0), 15 mg/ml citric acid (Sigma Aldrich), and 0.4 μM SYTOX Red. Lysis solution 2 was added to cells for 1 hour in the dark at room temperature. Details regarding the lysis solutions have been published previously.75 The cell lysis protocol keeps nuclear membranes intact thus enabling the identification of nuclei with <2 N, 2 N, 4 N, and >4 N DNA content as well as micronuclei.

Nuclear gating was performed as previously published.75 Samples were analyzed on the BD LSRFortessa with 488 nm, 640 nm and 405 nm lasers in the CCHMC Flow Cytometry core facility. SYTOX-associated fluorescence emission was detected using 640 nm excitation and a 660/20 bandpass filter, and EMA-associated fluorescence was detected using 488 nm excitation and a 610/20 bandpass filter. EMA positive nuclei were gated out prior to the quantification of micronuclei. Bleomycin, etoposide and colcemid were used as positive controls for micronucleus formation. The incidence of cells with micronuclei was determined through the acquisition of at least 10,000 gated nuclei per culture.

DEK expression module analysis

We evaluated DEK expression across the entire series of tumor samples that are profiled in 2158 Affymetrix Gene Chip Hg-133 plus 2.0 microarrays performed by the International Genome Consortium Expression Project for Ontology (ExpO; Gene Expression Omnibus Dataset GSE2109). To do this we used Pearson Correlation Analysis to identify the most strongly correlated probesets to the DEK probeset 200934_at across the RMA-normalized data set. Using a cutoff of Pearson Correlation 0.485 identified 307 probesets. Geneset enrichment and connectivity analysis was carried out using the ToppGene web server (http://toppgene.cchmc.org/) and ToppGene Suite76 for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization.

Statistics

Statistical significance was calculated using GraphPad Prism 6 software (La Jolla, CA, USA). The Fisher's exact test was used to determine significance of DEK localization during mitosis. A t-test was used to determine the significance of micronuclei presence by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry. When samples exceeded more than 2 groups, a 2-way anova test was used to determine significance for micronuclei detection by flow cytometry. Where indicated * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, and *** P ≤ 0.001.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. James Lessard of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and Seven Hills Bioresearch (Cincinnati, OH) for his gift of the C4 pan-actin monoclonal antibody used in this work. We thank David Williams (Children's Hospital Boston, MA) for the pMIEG3 retroviral vector. We thank Lisa Privette-Vinnedge (CCHMC) for all of her insightful comments and edits to the manuscript as well as Eric Smith for his edits.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

Funding

This work was supported by the Public Health Service Grant R01 CA116316 from the NIH (SIW). Work in the laboratory of Ferdinand Kappes is supported by the START Program of the Faculty of Medicine, RWTH Aachen and by the German Research Foundation (DFG KA 2799). We recognize the Research Flow Cytometry Core in the Division of Rheumatology at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, supported in part by NIH AR-47363, NIH DK78392 and NIH DK90971.

References

- 1.Rajagopalan H, Lengauer C. Aneuploidy and cancer. Nature 2004; 432:338-41; PMID:15549096; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature03099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boveri T. über mehrpolige Mitosen als Mittel zur Analyse des Zellkerns. Verhandlungen der physicalisch-medizinischen Gesselschaft zu Würzburg Neu Folge 1902; 67-90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boveri TGF. Zur Frage der Entstehung maligner Tumoren (The origin of malignant tumors). Gustav Fischer; 1914. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. Does aneuploidy cause cancer? Curr Opin Cell Biol 2006; 18:658-67; PMID:17046232; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duesberg P, Rausch C, Rasnick D, Hehlmann R. Genetic instability of cancer cells is proportional to their degree of aneuploidy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95:13692-7; PMID:9811862; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyberg KA, Michelson RJ, Putnam CW, Weinert TA. Toward maintaining the genome: DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Annu Rev Genet 2002; 36:617-56; PMID:12429704; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.060402.113540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kops GJ, Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. On the road to cancer: aneuploidy and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5:773-85; PMID:16195750; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenech M, Kirsch-Volders M, Natarajan AT, Surralles J, Crott JW, Parry J, Norppa H, Eastmond DA, Tucker JD, Thomas P. Molecular mechanisms of micronucleus, nucleoplasmic bridge and nuclear bud formation in mammalian and human cells. Mutagenesis 2011; 26:125-32; PMID:21164193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/mutage/geq052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakhoum SF, Genovese G, Compton DA. Deviant kinetochore microtubule dynamics underlie chromosomal instability. Curr Biol 19:1937-42; PMID:19879145; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver BAA, Silk AD, Montagna C, Verdier-Pinard P, Cleveland DW. Aneuploidy Acts Both Oncogenically and as a Tumor Suppressor. Cancer Cell 2007; 11:25-36; PMID:17189716; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michel LS, Liberal V, Chatterjee A, Kirchwegger R, Pasche B, Gerald W, Dobles M, Sorger PK, Murty VV, Benezra R. MAD2 haplo-insufficiency causes premature anaphase and chromosome instability in mammalian cells. Nature 2001:409, 355-9; PMID:11201745; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35053094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rehen SK, McConnell MJ, Kaushal D, Kingsbury MA, Yang AH, Chun J. Chromosomal variation in neurons of the developing and adult mammalian nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2001; 98:13361-6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.231487398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amato A, Lentini L, Schillaci T, Iovino F, Di Leonardo A. RNAi mediated acute depletion of Retinoblastoma protein (pRb) promotes aneuploidy in human primary cells via micronuclei formation. BMC Cell Biol 2009; 10:79; PMID:19883508; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2121-10-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenech M. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay evolves into a “cytome” assay of chromosomal instability, mitotic dysfunction and cell death. Mutat Res 2006; 600:58-66; PMID:16822529; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund T, Laland SG. The metaphase specific phosphorylation of HMG I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1990; 171:342-7; PMID:2168176; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0006-291X(90)91399-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prymakowska-Bosak M, Misteli T, Herrera JE, Shirakawa H, Birger Y, Garfield S, Bustin M. Mitotic phosphorylation prevents the binding of HMGN proteins to chromatin. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21:5169-78; PMID:11438671; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5169-5178.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldmann T, Eckerich C, Baack M, Gruss C. The ubiquitous chromatin protein DEK alters the structure of DNA by introducing positive supercoils. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:24988-94; PMID:11997399; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M204045200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawatsubashi S, Murata T, Lim J, Fujiki R, Ito S, Suzuki E, Tanabe M, Zhao Y, Kimura S, Fujiyama S, et al.. A histone chaperone, DEK, transcriptionally coactivates a nuclear receptor. Genes Dev 2010; 24:159-70; PMID:20040570; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1857410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivanauskiene K, Delbarre E, McGhie JD, Küntziger T, Wong LH, Collas P. The PML-associated protein DEK regulates the balance of H3.3 loading on chromatin and is important for telomere integrity. Genome Res 2014; 24:1584-94; PMID:25049225; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.173831.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kappes F, Waldmann T, Mathew V, Yu J, Zhang L, Khodadoust MS, Chinnaiyan AM, Luger K, Erhardt S, Schneider R, et al.. The DEK oncoprotein is a Su(var) that is essential to heterochromatin integrity. Genes Dev 2011; 25:673-8; PMID:21460035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.2036411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carro MS, Spiga FM, Quarto M, Di Ninni V, Volorio S, Alcalay M, Müller H. DEK Expression is controlled by E2F and deregulated in diverse tumor types. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 2006; 5, 1202-7; PMID:16721057; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.5.11.2801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grasemann C, Gratias S, Stephan H, Schüler A, Schramm A, Klein-Hitpass L, Rieder H, Schneider S, Kappes F, Eggert A, et al.. Gains and overexpression identify DEK and E2F3 as targets of chromosome 6p gains in retinoblastoma. Oncogene 2005; 24:6441-9; PMID:16007192; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1208792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Lindern M, Fornerod M, Soekarman N, van Baal S, Jaegle M, Hagemeijer A, Bootsma D, Grosveld G, et al.. Translocation t(6;9) in acute non-lymphocytic leukaemia results in the formation of a DEK-CAN fusion gene. Bailliere's Clin Haematol 1992; 5:857-79; PMID:1308167; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0950-3536(11)80049-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Q, Hoffmann MJ, Hartmann FH, Schulz WA. Amplification and overexpression of the ID4 gene at 6p22.3 in bladder cancer. Mol Cancer 2005; 4:16; PMID:15876350; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1476-4598-4-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Privette Vinnedge LM, Ho SM, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Wells SI. The DEK oncogene is a target of steroid hormone receptor signaling in breast cancer. PloS One 2012; 7:e46985; PMID:23071688; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0046985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theurillat J-P, Udeshi ND, Errington WJ, Svinkina T, Baca SC, Pop M, Wild PJ, Blattner M, Groner AC, Rubin MA, et al.. SPOP mutations alter the Ubiquitin landscape in prostate cancer. Cancer Discov 2014; 4:Of19; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-rw2014-214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babaei-Jadidi R, Li N, Saadeddin A, Spencer-Dene B, Jandke A, Muhammad B, Ibrahim EE, Muraleedharan R, Abuzinadah M, Davis H, et al.. FBXW7 influences murine intestinal homeostasis and cancer, targeting Notch, Jun, and DEK for degradation. J Exp Med 2011; 208:295-312; PMID:21282377; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20100830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wise-Draper TM, Allen HV, Thobe MN, Jones EE, Habash KB, Münger K, Wells SI. The human DEK proto-oncogene is a senescence inhibitor and an upregulated target of high-risk human papillomavirus E7. J Virol 2005; 79:14309-17; PMID:16254365; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14309-14317.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wise-Draper TM, Mintz-Cole RA, Morris TA, Simpson DS, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Currier MA, Cripe TP, Grosveld GC, Wells SI. Overexpression of the cellular DEK protein promotes epithelial transformation in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 2009; 69:1792-9; PMID:19223548; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wise-Draper TM, Morreale RJ, Morris TA, Mintz-Cole RA, Hoskins EE, Balsitis SJ, Husseinzadeh N, Witte DP, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Lambert PF, et al.. DEK proto-oncogene expression interferes with the normal epithelial differentiation program. A J Pathol 2009; 174:71-81; PMID:19036808; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Privette Vinnedge LM, McClaine R, Wagh PK, Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA, Waltz SE, Wells SI. The human DEK oncogene stimulates beta-catenin signaling, invasion and mammosphere formation in breast cancer. Oncogene 2011; 30:2741-52; PMID:21317931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2011.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deutzmann A, Ganz M, Schönenberger F, Vervoorts J, Kappes F, Ferrando-May E. The human oncoprotein and chromatin architectural factor DEK counteracts DNA replication stress. Oncogene 2014; Epub ahead of print; PMID:25347734; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2014.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohm F, Kappes F, Scholten I, Richter N, Matsuo H, Knippers R, Waldmann T. The SAF-box domain of chromatin protein DEK. Nucleic acids Res 2005; 33:1101-10; PMID:15722484; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gki258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kappes F, Scholten I, Richter N, Gruss C, Waldmann T. Functional domains of the ubiquitous chromatin protein DEK. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24:6000-10; PMID:15199153; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.24.13.6000-6010.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campillos M, Garcia MA, Valdivieso F, Vazquez J. Transcriptional activation by AP-2alpha is modulated by the oncogene DEK. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31:1571-5; PMID:12595566; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkg247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sammons M, Wan SS, Vogel NL, Mientjes EJ, Grosveld G, Ashburner BP. Negative regulation of the RelA/p65 transactivation function by the product of the DEK proto-oncogene. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:26802-12; PMID:16829531; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M600915200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kavanaugh GM, Wise-Draper TM, Morreale RJ, Morrison MA, Gole B, Schwemberger S, Tichy ED, Lu L, Babcock GF, Wells JM, et al.. The human DEK oncogene regulates DNA damage response signaling and repair. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39:7465-76; PMID:21653549; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkr454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kappes F, Damoc C, Knippers R, Przybylski M, Pinna LA, Gruss C. Phosphorylation by protein kinase CK2 changes the DNA binding properties of the human chromatin protein DEK. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24:6011-20; PMID:15199154; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.24.13.6011-6020.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cleary J, Sitwala KV, Khodadoust MS, Kwok RP, Mor-Vaknin N, Cebrat M, Cole PA, Markovitz DM. p300/CBP-associated factor drives DEK into interchromatin granule clusters. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:31760-7; PMID:15987677; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M500884200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kappes F, Fahrer J, Khodadoust MS, Tabbert A, Strasser C, Mor-Vaknin N, Moreno-Villanueva M, Bürkle A, Markovitz DM, Ferrando-May E. DEK is a poly(ADP-ribose) acceptor in apoptosis and mediates resistance to genotoxic stress. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28:3245-57; PMID:18332104; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01921-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Privette Vinnedge LM, Kappes F, Nassar N, Wells SI. Stacking the DEK: from chromatin topology to cancer stem cells. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 2013; 12:51-66; PMID:23255114; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.23121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldmann T, Scholten I, Kappes F, Hu HG, Knippers R. The DEK protein–an abundant and ubiquitous constituent of mammalian chromatin. Gene 2004; 343:1-9; PMID:15563827; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gene.2004.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fornerod M, Fahrer J, Khodadoust MS, Tabbert A, Strasser C, Mor-Vaknin N, Moreno-Villanueva M, Bürkle A, Markovitz DM, Ferrando-May E. Relocation of the carboxyterminal part of CAN from the nuclear envelope to the nucleus as a result of leukemia-specific chromosome rearrangements. Oncogene 1995; 10:1739-48; PMID:7753551 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gassmann R, Henzing AJ, Earnshaw WC. Novel components of human mitotic chromosomes identified by proteomic analysis of the chromosome scaffold fraction. Chromosoma 2005; 113:385-97; PMID:15609038; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00412-004-0326-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen-Hoffmann BL, Schlosser SJ, Ivarie CA, Sattler CA, Meisner LF, O'Connor SL. Normal growth and differentiation in a spontaneously immortalized near-diploid human keratinocyte cell line, NIKS. The J Invest Dermatol 2000; 114:444-55; PMID:10692102; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonassi S, Znaor A, Ceppi M, Lando C, Chang WP, Holland N, Kirsch-Volders M, Zeiger E, Ban S, Barale R, et al.. An increased micronucleus frequency in peripheral blood lymphocytes predicts the risk of cancer in humans. Carcinogenesis 2007; 28:625-31; PMID:16973674; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/carcin/bgl177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez A, Saldanha PH. Micronucleus investigation of alcoholic patients with oral carcinomas. Genet Mol Res 2002; 1:246-60; PMID:14963832 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaur J, Dey P. Micronucleus to distinguish adenocarcinoma from reactive mesothelial cell in effusion fluid. Diagn Cytopathol 2010; 38:177-9; PMID:19693939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samanta S, Dey P, Gupta N, Mouleeswaran KS, Nijhawan R. Micronucleus in atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance. Diagn Cytopathol 2011; 39:242-4; PMID:21416636; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/dc.21368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arora SK, Dey P, Saikia UN. Micronucleus in atypical urothelial cells. Diagn Cytopathol 2010; 38:811-3; PMID:20049965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/dc.21297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kappes F, Burger K, Baack M, Fackelmayer FO, Gruss C. Subcellular localization of the human proto-oncogene protein DEK. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:26317-23; PMID:11333257; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M100162200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adams AK, Hallenbeck GE, Casper KA, Patil YJ, Wilson KM, Kimple RJ, Lambert PF, Witte DP, Xiao W, Gillison ML, et al.. DEK promotes HPV-positive and -negative head and neck cancer cell proliferation. Oncogene 2014; 0:1; PMID:24608431; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2014.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim DW, Kim JY, Choi S, Rhee S, Hahn Y, Seo SB. Transcriptional regulation of 1-cys peroxiredoxin by the proto-oncogene protein DEK. Mol Med Rep 2010; 3:877-81; PMID:21472329; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3892/mmr.2010.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu K, Feng T, Liu J, Zhong M, Zhang S. Silencing of the DEK gene induces apoptosis and senescence in CaSki cervical carcinoma cells via the up-regulation of NF-kappaB p65. Biosci Rep 2012; 32:323-32; PMID:22390170; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/BSR20100141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karam M, Thenoz M, Capraro V, Robin JP, Pinatel C, Lancon A, Galia P, Sibon D, Thomas X, Ducastelle-Lepretre S, et al.. Chromatin redistribution of the DEK oncoprotein represses hTERT transcription in leukemias. Neoplasia (New York, N.Y.) 2014; 16:21-30; PMID:24563617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gamble MJ, Fisher RP. SET and PARP1 remove DEK from chromatin to permit access by the transcription machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2007; 14:548-55; PMID:17529993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koleva RI, Ficarro SB, Radomska HS, Carrasco-Alfonso MJ, Alberta JA, Webber JT, Luckey CJ, Marcucci G, Tenen DG, Marto JA, et al.. C/EBPalpha and DEK coordinately regulate myeloid differentiation. Blood 2012; 119:4878-88; PMID:22474248; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2011-10-383083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong C, Stearns T. Mammalian cells lack checkpoints for tetraploidy, aberrant centrosome number, and cytokinesis failure. BMC Cell Biol 2005; 6:6; PMID:15713235; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2121-6-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Attia SM, Ahmad SF, Okash RM, Bakheet SA. Dominant lethal effects of nocodazole in germ cells of male mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2015; 77:101-4; PMID:25595372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.fct.2015.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Endo K, Mizuguchi M, Harata A, Itoh G, Tanaka K. Nocodazole induces mitotic cell death with apoptotic-like features in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett 2010; 584:2387-92; PMID:20399776; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giunta S, Belotserkovskaya R, Jackson SP. DNA damage signaling in response to double-strand breaks during mitosis. J Cell Biol 2010; 190:197-207; PMID:20660628; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200911156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dutertre S, Ababou M, Onclercq R, Delic J, Chatton B, Jaulin C, Amor-Guéret M. Cell cycle regulation of the endogenous wild type Bloom's syndrome DNA helicase. Oncogene 2000; 19:2731-8; PMID:10851073; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1203595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koike M, Awaji T, Kataoka M, Tsujimoto G, Kartasova T, Koike A, Shiomi T. Differential subcellular localization of DNA-dependent protein kinase components Ku and DNA-PKcs during mitosis. J Cell Sci 1999; 112 (Pt 22):4031-9; PMID:10547363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan KL, Palmai-Pallag T, Ying S, Hickson ID. Replication stress induces sister-chromatid bridging at fragile site loci in mitosis. Nat Cell Biol 2009; 11:753-60; PMID:19465922; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cappelli E, Townsend S, Griffin C, Thacker J. Homologous recombination proteins are associated with centrosomes and are required for mitotic stability. Exp Cell Res 2011; 317:1203-13; PMID:21276791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Olsen JV, Vermeulen M, Santamaria A, Kumar C, Miller ML, Jensen LJ, Gnad F, Cox J, Jensen TS, Nigg EA, et al.. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals widespread full phosphorylation site occupancy during mitosis 2010; 3:ra3; PMID:20068231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Avila J, Ulloa L, Gonzalez J, Moreno F, Diaz-Nido J. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated proteins by protein kinase CK2 in neuritogenesis. Cell Mol Biol Res 1994; 40:573-9; PMID:7537578 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Glover CV, 3rd. On the physiological role of casein kinase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 1998; 59:95-133; PMID:9427841; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)61030-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lorenz P, Pepperkok R, Ansorge W, Pyerin W. Cell biological studies with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against human casein kinase II subunit beta demonstrate participation of the kinase in mitogenic signaling. J Biol Chem 1993; 268:2733-9; PMID:8428947 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Faust M, Schuster N, Montenarh M. Specific binding of protein kinase CK2 catalytic subunits to tubulin. FEBS Lett 1999; 462:51-6; PMID:10580090; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01492-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petersen DF, Anderson EC, Tobey RA. Mitotic Cells As A Source Of Synchronized Cultures. Prescott DM. (Ed.) Academic Press, New York: 1968; 3:347-70 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams DA, Tao W, Yang F, Kim C, Gu Y, Mansfield P, Levine JE, Petryniak B, Derrow CW, Harris C, Jia B, et al.. Dominant negative mutation of the hematopoietic-specific Rho GTPase, Rac2, is associated with a human phagocyte immunodeficiency. Blood 2000; 96:1646-54; PMID:10961859 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Avlasevich S, Bryce S, De Boeck M, Elhajouji A, Van Goethem F, Lynch A, Nicolette J, Shi J, Dertinger S. Flow cytometric analysis of micronuclei in mammalian cell cultures: past, present and future. Mutagenesis 2011; 26:147-52; PMID:21164196; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/mutage/geq058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bryce SM, Avlasevich SL, Bemis JC, Dertinger SD. Miniaturized flow cytometry-based CHO-K1 micronucleus assay discriminates aneugenic and clastogenic modes of action. Environ Mol Mutagen 2011; 52:280-6; PMID:20872831; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/em.20618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bryce SM, Bemis JC, Avlasevich SL, Dertinger SD. In vitro micronucleus assay scored by flow cytometry provides a comprehensive evaluation of cytogenetic damage and cytotoxicity. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2007; 630:78-91; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen J, Bardes EE, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res 2009; 37:W305-311; PMID:19465376; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkp427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.