ABSTRACT

Antiretroviral treatment (ART) initiation in HIV-infected pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remains inadequate, and there is a severe shortage of professional healthcare workers in the region. The effectiveness of community support programmes for HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants in SSA is unclear. This study compared initiation of maternal antiretrovirals and infant outcomes amongst HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants who received and did not receive community-based support (CBS) in a high HIV-prevalence setting in South Africa. A cohort study, including HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants, was conducted at three sentinel surveillance facilities between January 2009 and June 2012, utilising enhanced routine clinical data. Through home visits, CBS workers encouraged uptake of interventions in the ART cascade, provided HIV-related education, ART initiation counselling and psychosocial support. Outcomes were compared using Kaplan–Meier analyses and multivariable Cox and log-binomial regression. Amongst 1105 mother–infant pairs included, 264 (23.9%) received CBS. Amongst women eligible to start ART antenatally, women who received CBS had a reduced risk of not initiating antenatal ART, 5.4% vs. 30.3%; adjusted risk ratio (aRR) = 0.18 (95% CI: 0.08–0.44; P < .0001). Women who received CBS initiated antenatal ART with less delay after the first antenatal visit, median 26 days vs. 39 days; adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 1.57 (95% CI: 1.15–2.14; P = .004). Amongst women who initiated antenatal zidovudine (ZDV) to prevent vertical transmission, women who received CBS initiated ZDV with less delay, aHR = 1.52 (95% CI: 1.18–2.01; P = .001). Women who received CBS had a lower risk of stillbirth, 1.5% vs. 5.4%; aRR = 0.24 (95% CI: 0.07–1.00; P = .050). Pregnant women living with HIV who received CBS had improved antenatal triple ART initiation in eligible women, women initiated ART and ZDV with shorter delays, and had a lower risk of stillbirth. CBS is an intervention that shows promise in improving maternal and infant health in high HIV-prevalence settings.

KEYWORDS: Pregnancy, prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, community-based support, lay health workers, antiretroviral treatment, South Africa

Introduction

Antiretroviral treatment (ART) initiation during pregnancy is vital in HIV-infected women for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) and to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality (World Health Organization, 2013). However, uptake of components of the ART and PMTCT cascades in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are unsatisfactory, delays and missed opportunities are frequent, and lack of antiretroviral receipt is the most important factor contributing to ongoing vertical HIV transmission (Schnippel, Mongwenyana, Long, & Larson, 2015; Woldesenbet et al., 2015). There are unique and substantial psychosocial barriers to ART initiation and adherence in HIV-infected pregnant women, which frequently remain unaddressed by the health system (Colvin et al., 2014; Hodgson et al., 2014). In 2013, 32% of HIV-infected pregnant women in SSA did not receive any antiretrovirals (UNAIDS, 2014).

A critical professional healthcare worker shortage exists in SSA, being an important barrier to the expansion of the ART programme and maternal ART initiation (Bärnighausen, Bloom, & Humair, 2007; Colvin et al., 2014). Accordingly, task-shifting of healthcare functions to lay community workers has occurred. There are little data regarding the effectiveness of community programmes for HIV-infected pregnant women in SSA, and is an area requiring evaluation (Colvin et al., 2014; World Health Organization, 2013).

Globally, South Africa has the greatest number of pregnant women requiring ART (UNAIDS, 2014). This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a community-based support (CBS) programme for HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants in a high HIV-prevalence district in South Africa, by comparing maternal initiation of antiretrovirals and infant outcomes between mother–infant pairs who received and did not receive CBS.

Methods

A cohort study was undertaken at three urban public facilities in the Nelson Mandela Bay district. Facilities were supported by Kheth'Impilo, which provides health systems strengthening innovations and managed the clinic-linked CBS programme. The district antenatal HIV-prevalence in 2011 was 28.3%.

HIV-infected pregnant women presenting between January 2009 and June 2012 were included. Infants were followed-up (where possible) until the first HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing at approximately six weeks post-delivery. Supplemental online material 1 summarises maternal ART eligibility criteria.

CBS workers are lay healthcare workers providing ART initiation and adherence counselling and psychosocial support for women, who provide a continuum of care during the antenatal and postnatal periods and encourage uptake of the maternal ART and PMTCT cascade components. CBS workers are trained regarding HIV and tuberculosis infection and treatment, PMTCT, and how to address psychosocial barriers to ART initiation and adherence.

During home visits by the CBS worker, psychosocial barriers to ART initiation and adherence, including denial, non-disclosure, lack of partner involvement, stigma, fear of lifelong ART, depression, substance abuse, gender-based violence, nutrition security and social assistance grant eligibility, were assessed and addressed. Women eligible to initiate ART were visited three times during the ART preparation/initiation week, then weekly for a month, then monthly. CBS workers were assigned 80–120 patients each and received remuneration for their work. Evolving roles of CBS workers included management of serodiscordant couples, promoting exclusive breastfeeding, infant health promotion and household HIV testing.

The CBS programme could not support all geographic areas in which pregnant women resided for capacity reasons, thus at the first antenatal visit a community co-ordinator allocated consenting women who lived in supported areas to receive a CBS worker on a pragmatic basis, irrespective of woman's clinical or socioeconomic factors. Programme capacity increased over time as funding increased, extending support to larger areas and more women.

The outcomes were risk of not initiating triple ART antenatally amongst women eligible to initiate ART; time until initiating ART from the first antenatal visit amongst women who initiated ART antenatally (rate of antenatal ART initiation); risk of not initiating antenatal zidovudine (ZDV) amongst women eligible to initiate ZDV for PMTCT; time until initiating antenatal ZDV from date of eligibility following first antenatal visit amongst women who initiated ZDV (rate of antenatal ZDV initiation); proportion of women who received ART antenatally amongst all women (ART coverage at delivery); proportion of infants stillborn; and proportion of infants testing PCR positive around 6 weeks of age (vertical HIV transmission).

Enhanced routine clinical data were collected prospectively in custom-designed electronic databases, and infant follow-up data were sourced from surrounding health services. Analyses were by intention-to-treat ignoring changes in exposure status. Kaplan–Meier estimates, the logrank test and multivariable Cox's proportional hazards regression were used to assess the effect of CBS on time until commencing ART or ZDV. Log-binomial regression was used to analyse the effect of CBS on the remaining outcomes.

The following a priori specified confounders were eligible to be included in multivariable regression models to control for confounding: maternal age, baseline CD4 cell count, year of first antenatal visit, baseline gestational age, known HIV positive status at baseline, infant feeding choice and antiretroviral regimen received. The University of Cape Town Research Ethics Committee provided ethical approval.

Results

Amongst 1105 mother–infant pairs included, 264 (23.9%) received CBS. The median baseline CD4 cell count was 305 and 361 cells/µL in women who received and did not receive CBS, respectively, P = .010 (baseline table, supplemental online material 2).

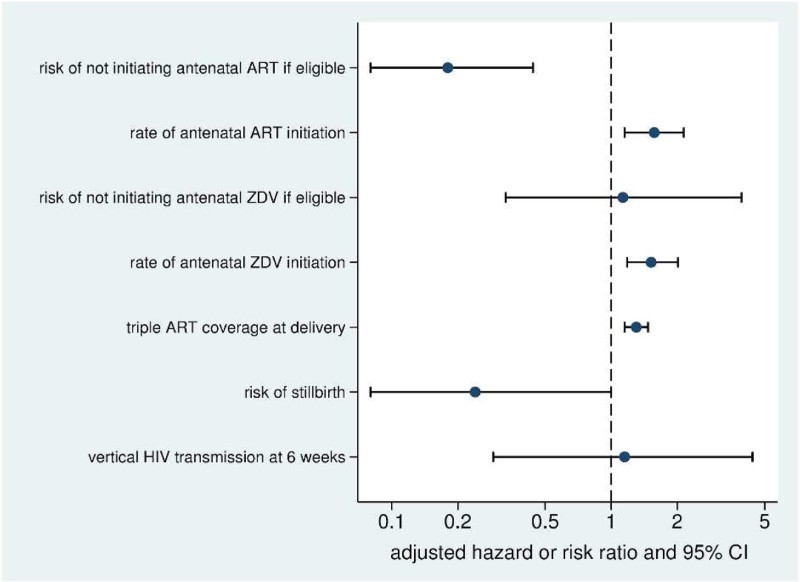

Amongst women eligible to initiate triple ART, the proportions who failed to initiate ART antenatally were 5.4% and 30.3% amongst women who received and did not receive CBS, respectively (P < .0001) (Table 1). After adjustment, the risk of not initiating ART antenatally was substantially reduced amongst women who received CBS, adjusted risk ratio (aRR) = 0.18 (95% CI: 0.08–0.44; P < .0001) (Figure 1).

Table 1. Crude and adjusted maternal and infant outcomes amongst women who received and did not receive CBS in South Africa.

| Received CBS | Did not receive CBS | Crude effect measure (95% CI) (CBS vs. no CBS) | Crude P-value | Adjusted effect measure (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women eligible to initiate triple ART who failed to initiate triple ART antenatally, n/N (%) | 6/112 (5.4%) | 88/290 (30.3%) | 0.17 (0.07–0.39)a | <.0001 | 0.18 (0.08–0.44)a | <.0001 |

| Time till initiating triple ART from the first antenatal visit, median, days (IQR)c | 26 (13–49) | 39 (22–72) | 1.49 (1.12–1.97)b | .006 | 1.57 (1.15–2.14)b | .004 |

| Women eligible to initiate antenatal ZDV who failed to initiate ZDV, n/N (%) | 5/86 (5.8%) | 36/392 (9.2%) | 0.63 (0.26–1.57)a | .32 | 1.13 (0.33–3.92)a | .85 |

| Time till initiating antenatal ZDV since eligibility, median, days (IQR)d | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–28) | 1.66 (1.30–2.11)b | <.0001 | 1.52 (1.18–2.01)b | .001 |

| Proportion of all women who received ART by delivery, n/N (%) | 171/264 (64.8%) | 324/841 (38.5%) | 1.68 (1.49–1.90)a | <.0001 | 1.30 (1.15–1.47)a | <.0001 |

| Stillbirths, n/N (%) | 4/264 (1.5%) | 45/841 (5.4%) | 0.27 (0.10–0.76)a | .0067 | 0.24 (0.07–1.00)a | .050 |

| Positive infant PCR tests around six weeks of age, n/N (%) | 3/76 (3.95%) | 13/392 (3.32%) | 1.19 (0.35–4.07)a | .782 | 1.15 (0.29–4.40)a | .84 |

Note: ART, antiretroviral treatment; ZDV, zidovudine; PCR, HIV deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction; IQR, interquartile range.

aRR (95% confidence interval).

bHR (95% confidence interval).

cAmongst women who commenced triple ART antenatally.

dAmongst women who initiated ZDV antenatally. For women with zero survival time, 0.1 day was added to survival times in order to include subjects in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Adjusted effect measures: women who received CBS vs. women who did not receive CBS. Effect measures for rate of antenatal ART initiation and rate of antenatal ZDV initiation are aHR. Remaining effect measures are aRR. Horizontal bars are 95% confidence intervals. ART, triple antiretroviral treatment; ZDV, zidovudine.

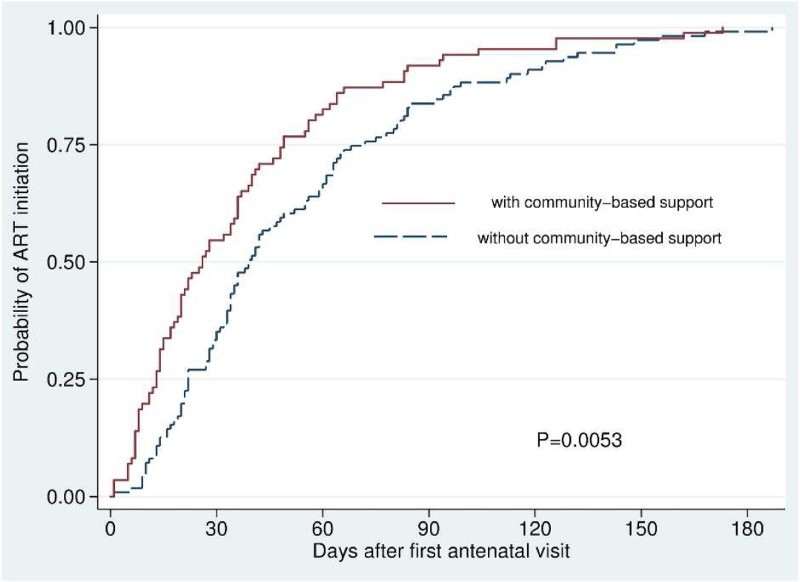

Women who received CBS started ART with less delay following the first antenatal visit; median 26 days vs. 39 days amongst women who did not receive CBS (P = .0053) (Figure 2). After adjustment, the rate of ART initiation was 57% greater amongst women who received CBS, adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 1.57 (95% CI: 1.15–2.14; P = .004). Amongst women ineligible for ART who initiated ZDV, women who received CBS initiated ZDV with less delay following the first antenatal visit, median 0 days (interquartile range (IQR): 0–0 days) vs. 1 day (IQR: 0–28) amongst women who did not receive CBS; aHR = 1.52 (95% CI: 1.18–2.01; P = .001), see supplemental online material 3 (figure).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of time till antenatal triple ART initiation after the first antenatal visit amongst pregnant women initiating ART in South Africa.

At delivery, ART coverage (amongst all women) was 64.8% and 38.5% in women who received and did not receive CBS, respectively; aRR = 1.30 (95% CI: 1.15–1.47; P < .0001).

The proportion of stillborn infants was lower amongst women who received CBS (1.5% vs. 5.4%; P = .0067); aRR = 0.24 (95% CI: 0.07–1.00; P = .050). The proportions of positive infant PCR tests amongst women with and without CBS were 3.95% and 3.32%, respectively, with no difference in transmission risk between the two groups, aRR = 1.15 (95% CI: 0.29–4.40; P = .84).

Discussion

HIV-infected pregnant women who received CBS had improved antenatal ART initiation, women initiated ART and ZDV with less delay, and the risk of stillbirth was reduced.

ART initiation amongst eligible pregnant South African women has been low and associated with significant delay (Stinson, Jennings, & Myer, 2013). Pregnant women newly diagnosed with HIV face the triple burden of transitioning into pregnancy, accepting the HIV diagnosis and comprehending the urgent need to start lifelong ART before delivery, a combination of events requiring complex psychosocial reorganisation (Stinson & Myer, 2012). High levels of depression are found amongst women undergoing HIV testing (Rochat et al., 2006), and women testing HIV positive during pregnancy experience severe emotional distress (Sherr, 2009). Other barriers limiting ART initiation during pregnancy include a poor understanding of HIV and PMTCT, challenges to the practical demands of ART, substance abuse, lack of partner involvement in diagnosis and treatment, and perceived stigma (Hodgson et al., 2014). These barriers can generally not be addressed by overburdened professional healthcare staff in antenatal clinics (Stein et al., 2008). The focussed and sustained individual support provided by lay community counsellors trained in the psychosocial aspects of pregnancy, ART initiation and adherence likely account for the improved ART initiation amongst women who received CBS.

HIV increases the risk of stillbirth (Rollins et al., 2007). Reasons for reduced stillbirths associated with CBS are unclear, although it is plausible that counselling and support regarding nutrition and social grant assistance may have improved maternal nutrition status, which is an important predictor of improved birth outcome (Wrottesley, Lamper, & Pisa, 2015), considering that pregnant HIV-infected South African women are at high risk of malnutrition (Banda, Pribram, Lawson, Mkangama, & Nyirenda, 2011).

Study limitations include the nonrandomised design with the potential for selection bias and unmeasured or residual confounding. Pregnant women were allocated to receive the intervention on the basis of availability of community workers and geography of client's residence. As random allocation in studies in pragmatic settings may be challenging, the study findings may be generalised with caution. Of note, however, is that nonrandomised studies of this intervention type are more pragmatic and suitable in low-income settings, as randomised experiments are suitable and feasible for only a small proportion of HIV interventions (Thomas, Curtis, & Smith, 2011). In addition, the use of routine data in this study has the potential for information bias. This studies power to detect potential differences in vertical HIV transmission was low (approximately 10%, to detect a 25% relative reduction in HIV transmission had all infant PCR results been available). Substantially greater sample sizes would thus be required to detect potential differences in vertical HIV transmission due to CBS.

In conclusion, CBS is associated with improved ART initiation amongst HIV-infected pregnant women, and further expansion of CBS may improve maternal and infant health in resource-poor settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge participants included in the study, the Department of Health of the Eastern Cape, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United States Agency for International Development and the Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

This article makes reference to supplementary material available on the publisher's website at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1148112

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Banda T., Pribram V., Lawson M., Mkangama C., Nyirenda G. Malnutrition, infant feeding, maternal and child health. In: Pribram V., editor. Nutrition and HIV. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2011. pp. 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bärnighausen T., Bloom D. E., Humair S. Human resources for treating HIV/AIDS: Needs, capacities, and gaps. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;(11):799–812. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin C. J., Konopka S., Chalker J. C., Jonas E., Albertini J., Amzel A., Fogg K. A systematic review of health system barriers and enablers for antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS ONE. 2014;(10):e108150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson I., Plummer M. L., Konopka S. N., Colvin C. J., Jonas E., Albertini J., Fogg K. P. A systematic review of individual and contextual factors affecting ART initiation, adherence, and retention for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS ONE. 2014;(11):e111421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat T. J., Richter L. M., Doll H. A., Buthelezi N. P., Tomkins A., Stein A. Depression among pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing. JAMA. 2006;(12):1373–1378. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins N. C., Coovadia H. M., Bland R. M., Coutsoudis A., Bennish M. L., Patel D., Newell M. L. Pregnancy outcomes in HIV-infected and uninfected women in rural and urban South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;(3):321–328. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802ea4b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnippel K., Mongwenyana C., Long L. C., Larson B. A. Delays, interruptions, and losses from prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services during antenatal care in Johannesburg, South Africa: A cohort analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015:46. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr L. Vertical transmission of HIV: Pregnancy and infant issues. In: Rohleder P., Swartz L., Kalichman S. C., Simbayi L. C., editors. HIV/AIDS in South Africa 25 years on. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Stein J., Lewin S., Fairall L., Mayers P., English R., Bheekie A., Zwarenstein M. Building capacity for antiretroviral delivery in South Africa: A qualitative evaluation of the PALSA PLUS nurse training programme. BMC Health Services Research. 2008:240. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson K., Jennings K., Myer L. Integration of antiretroviral therapy services into antenatal care increases treatment initiation during pregnancy: A cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2013;(5):e63328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson K., Myer L. Barriers to initiating antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy: A qualitative study of women attending services in Cape Town, South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2012;(1):65–73. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2012.671263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. C., Curtis S., Smith J. B. The broader context of implementation science. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;(1):e19–e21. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31822103e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS 2014 The gap report. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/20140716_UNAIDS_gap_report.

- Woldesenbet S., Jackson D., Lombard C., Dinh T.-H., Puren A., Sherman G., Goga A. Missed opportunities along the prevention of mother-to-child transmission services cascade in South Africa: Uptake, determinants, and attributable risk (the SAPMTCTE) PLoS ONE. 2015;(7):e0132425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization 2013 Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Recommendations for a public health approach. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/download/en/

- Wrottesley S. V., Lamper C., Pisa P. T. Review of the importance of nutrition during the first 1000 days: Maternal nutritional status and its associations with fetal growth and birth, neonatal and infant outcomes among African women. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 2015:1–19. doi: 10.1017/s2040174415001439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.