Abstract

Purpose

Morphologic and genetic evidence exists that an overactive complement system driven by the complement alternative pathway (AP) is involved in pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Smoking is the only modifiable risk factor for AMD. As we have shown that smoke-related ocular pathology can be prevented in mice that lack an essential activator of AP, we ask here whether this pathology can be reversed by increasing inhibition in AP.

Methods

Mice were exposed to either cigarette smoke (CS) or filtered air (6 hours/day, 5 days/week, 6 months). Smoke-exposed animals were then treated with the AP inhibitor (CR2-fH) or vehicle control (PBS) for the following 3 months. Spatial frequency and contrast sensitivity were assessed by optokinetic response paradigms at 6 and 9 months; additional readouts included assessment of retinal morphology by electron microscopy (EM) and gene expression analysis by quantitative RT-PCR.

Results

The CS mice treated with CR2-fH showed significant improvement in contrast threshold compared to PBS-treated mice, whereas spatial frequency was unaffected by CS or pharmacologic intervention. Treatment with CR2-fH in CS animals reversed thinning of the retina observed in PBS-treated mice as analyzed by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography, and reversed most morphologic changes in RPE and Bruch's membrane seen in CS animals by EM.

Conclusions

Taken together, these findings suggest that AP inhibitors not only prevent, but have the potential to accelerate the clearance of complement-mediated ocular injury. Improving our understanding of the regulation of the AP is paramount to developing novel treatment approaches for AMD.

Keywords: alternative complement pathway, CR2-fH, knockout mouse, smoke exposure, mitochondria, Bruch's membrane deposits, dry age-related macular degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness among the elderly in developed countries and is projected to affect 196 million people by 2020.1 Age-related macular degeneration is a progressive, degenerative disease of the retina that results in central vision loss caused by the degeneration of photoreceptor cells. This late-onset maculopathy can be diagnosed in two forms: atrophic, “dry”; or neovascular, “wet.”2 The atrophic form of the disease is marked by the formation of lipoprotein deposits known as drusen in the subretinal space between Bruch's membrane (BrM) and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The neovascular form is characterized by the proliferation of choroidal blood vessels (choroidal neovascularization, CNV) through BrM into the subretinal space. These fragile vessels leak fluid and proteins into the subretinal or sub-RPE space,3 leading to retinal detachment followed by photoreceptor cell death. Patients can develop either form of the disease; however, the atrophic form is most common, making up 90% of all cases.4

Age-related macular degeneration is a multiplex disease that is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Many of the main genetic risk factors are polymorphisms occurring in complement genes, a system whose role spans clearance of pathogens to mediating the induction and expansion of inflammatory injury. These genes include the complement alternative pathway (AP) inhibitor FH (factor H), the AP activator FB (factor B), and complement components C2 and C3. The most well known of these is the Y402H in FH. Its risk variant has been associated with increased levels of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the vitreous and an accumulation of choroidal macrophages, suggesting that a dysregulation of the proinflammatory cytokines locally in the eye underlies disease pathology.5 Increased levels of inflammation may be caused by poor binding of the 402H variants of factor H–like protein and FH to BrM due to an impaired ability to bind heparan sulphate.6,7 Furthermore, ranibizumab, a common antingiogenic used to treat AMD, has been shown to be either more or less effective depending on expression of the Y402H allele.8

Cigarette smoke is the most significant environmental factor contributing to AMD.9 Smoking promotes the progression of AMD from the atrophic to the neovascular form,10,11 and cessation has been shown to decrease the risk of developing AMD and the progression to CNV.12 The exact mechanism(s) responsible for a smoker's susceptibility to AMD is unknown, due in part to the large number of constituents in cigarette smoke and the potential for other contributing factors. Both cigarette smoke and hydroquinone, a component of cigarette smoke, induce oxidative damage and apoptosis in human RPE cells.13 Hydroquinone also downregulates proinflammatory monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in RPE cells, suggesting that incomplete clearance of proinflammatory debris coupled with increased angiogenesis may promote drusen formation and progression to CNV in AMD patients.14 Finally, smoke extract has been shown to directly activate C315 and trigger complement-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid deposition in ARPE-19 cells,16 providing a clear link between smoking and complement activation.

Previous studies by the Neufeld group13,17–20 have shown that mice with long-term cigarette smoke exposure (CSE) exhibit activation of the terminal pathway of the complement system in the RPE and choroid, concomitant with damage to the RPE and photoreceptors. We followed up on these findings by investigating the effects of long-term CSE in wild-type (WT) mice or mice lacking a functional AP (FB KO). Cigarette smoke exposure in WT mice resulted in functional (decreases in rod and cone electroretinography amplitudes), behavioral (decrease in cone-dependent contrast sensitivity), molecular (altered gene expression in RPE and photoreceptors), and morphologic (increase in mitochondrial size in the RPE, thickening of BrM) impairment, while FB KO mice were protected from developing any CSE-mediated alterations.21 In addition, we showed that C3d deposition could be identified in the RPE, BrM, and choriocapillaris, which was correlated with alterations in gene expression of complement components in the RPE-choroid fraction of the eye (increase in activators and a decrease in complement inhibitors).21 Using a novel model of smoking cessation,22–24 we expanded on these findings by investigating whether the detrimental effects caused by CSE are reversible following smoking cessation and treatment with the tissue-targeted AP inhibitor, CR2-fH.25 CR2-fH consists of the N-terminus of mouse complement factor H (short consensus repeats [SCR] 1–5), which contains the AP-inhibitory domain, linked to a complement receptor 2 (CR2) targeting fragment that binds complement activation products. The CR2 domain allows for targeting of the inhibitor factor H (fH) to sites of complement activation,26 and makes the CR2-fH protein independent of the endogenous ligand-binding domains present in CFH (SCR 6–8 and SCR 19/20) as shown in in vitro27–29 and in vivo26 studies.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA)30 and housed under a 12:12-hour light:dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum.

For intraperitoneal injections, a 25-gauge needle was inserted, and a 100-μL volume was injected (250 μg CR2-fH in PBS or PBS only). CR2-fH–expressing CHO cells were generously provided by S Tomlinson, and protein was generated and purified as published previously.25,26 Dosing and treatment schedules are outlined in the Results section. All experiments were approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Exposure to Cigarette Smoke

Eight-week-old C57BL/6J male mice were divided into three groups (n = 6 per group). The control group was kept in a filtered air environment, and the two experimental groups were subjected to cigarette smoke. Cigarette smoke exposure was carried out (5 hours per day, 5 days per week) by burning 3R4F reference cigarettes (University of Kentucky, Louisville, KY, USA) using a smoking machine (model TE-10; Teague Enterprises, Woodland, CA, USA) for 6 months as published previously.21 Carboxyhemoglobin levels in the mice after 2, 12, and 24 weeks of cigarette exposure as determined in venous blood by dual beam spectrophotometry31 were between 8% and 12% immediately after exposure, which is consistent with values reported in the literature for modeling the effects of chronic CSE.32–34 The average concentration of total suspended particulates present in the chamber was 130 mg/m3 and was monitored twice daily. Following 6 months of CSE, smoke-exposed animals were randomized into two groups (1, control PBS; 2, CR2-fH treated), and mice were followed for 12 weeks post smoking cessation. During this cessation period mice were exposed to normal room air.

Optokinetic Response Test

Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity of mice were measured by observing their optomotor responses to moving sine-wave gratings (OptoMotry; Cerebral Mechanics, Inc., Lethbridge, AB, Canada) as previously described.21 Mice reflexively respond to rotating vertical gratings by moving their head in the direction of grating rotation. To observe these movements, mice were placed individually on the central elevated pedestal surrounded by a square array of computer monitors that display stimulus gratings. Mice were monitored via an overhead closed-circuit TV camera that allowed the observer to view only the central platform and not the rotating grating. Mice were allowed to adjust to the chamber for 2 minutes with the monitors displaying a 50% gray uniform field prior to testing, and monitors returned to a homogenous gray between trials. All tests were conducted under photopic conditions with a mean luminance of 52 cd m−2. Visual acuity was measured by finding the spatial frequency threshold of each animal at a constant speed (12°/s) and contrast (100%) with a staircase procedure that systematically increased the spatial frequency of the grating until the animal no longer exhibited detectable responses. Contrast sensitivity was determined by taking the reciprocal of the contrast threshold at a fixed spatial frequency (0.131 cyc/deg) and speed (12°/s). It has previously been determined that this spatial frequency falls within the range of maximal contrast sensitivity for 9-month-old C57BL/6J mice (data not shown). Contrast of the pattern was decreased systematically in a staircase manner until the animal stopped responding.

Tissue Preparation

The eyes were enucleated, and a slit was cut into the cornea to allow for rapid influx of fixative. Eyes were fixed overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 1% formaldehyde, 3% sucrose, and 1 mM MgSO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. The eyes were then dissected, and small central portions were osmicated for 60 minutes in 0.5% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, processed in maleate buffer for en bloc staining with uranyl acetate, dehydrated in graded ethanols, and processed for resin embedding as published previously.35 Serial sections were cut at 90 nm on a Leica Ultramicrotome (Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) onto carbon-coated Formvar films supported by nickel slot-grids.

Ultrastructural Analysis

Electron microscopy images were captured using a JEOL JEM 1400 (Peabody, MA, USA) transmission electron microscope using SerialEM (Peabody, MA, USA) software to automate image capture overnight with 1200 to 1500 images captured per section, yielding datasets that were then processed with the NCR Toolset36,37 to generate image mosaics with corrections for image aberrations induced by electron microscopy.

Images were evaluated using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) and ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; provided in the public domain by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) software as published previously.21 For each animal, two RPE cells were outlined using the apical processes and the basal lamina (thickness) as well as the basolateral walls (length) as borders, and features were examined. Results from the two cells were averaged to provide a per mouse number. A masking layer for all mitochondria present within an RPE cell was created to calculate average mitochondrial number and size. To determine mitochondrial position, the centroid coordinates for each mitochondrion were calculated as a percentage of the corresponding RPE length and thickness, respectively. Coordinates were assigned to basolateral, basal, central, or apical compartments based on normalized x-y coordinates. The BrM thickness was determined by analyzing ∼200-μm sections of BrM. A masking layer was created over segments of BrM, using choroidal intercapillary pillars and the basement membrane of the RPE and choriocapillaris (CC) as boundaries. The area of the masking layer was divided by the length of each segment to determine an average BrM thickness for each segment. We then calculated a weighted thickness average, based on the percentage length of each segment versus the entire ∼200-μm section being analyzed. Finally, we determined the average BrM thickness by summing weighted averages for each section. The number of outer collagenous layer (OCL) deposits was calculated along a ∼200-μm section of BrM. An OCL deposit was defined as the presence of any discrete focal nodule of homogenous material of intermediate electron density between the OCL of BrM and the basement membrane of the CC. Outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness was determined by averaging measurements taken at five arbitrary points along a ∼200-μm section of retinal tissue, using the outer plexiform layer (upper) and outer limiting membrane (lower) as boundaries. Fenestrations were counted along a 100-μm section of BrM/CC and quantified as the number of fenestrations per mm. Fenestrations were identified as clearly defined gaps within the basement membrane of the CC. Müller cell percent area was determined by subtracting the area occupied by the rod/cone somas in a ∼600-μm2 area of the ONL and dividing by the total area analyzed, using the same masking technique as described for BrM thickness analysis. This area was also used to assess the number of nuclei within the ONL.

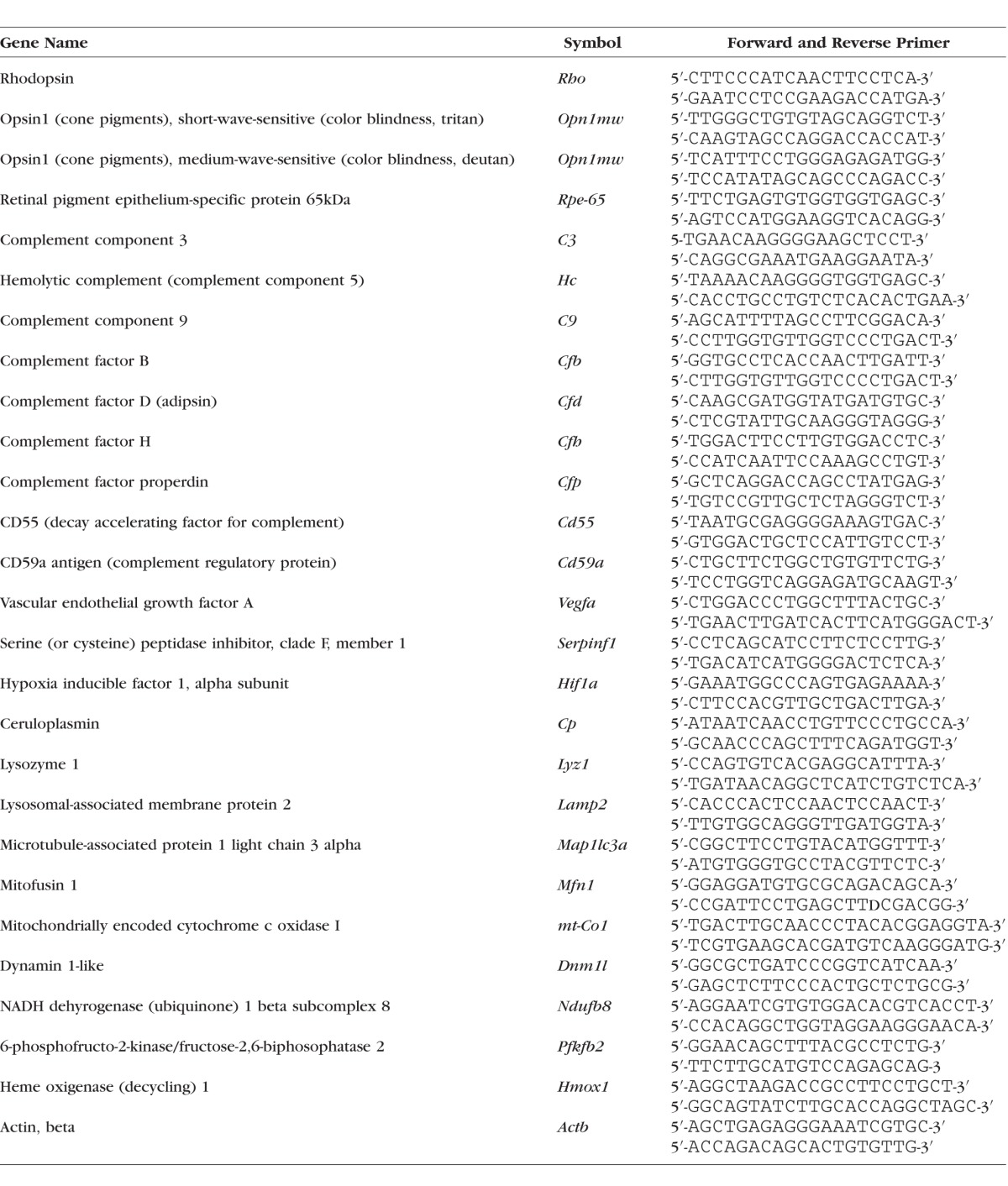

Quantitative RT-PCR

From the second eye of each animal, RPE/choroid/sclera (henceforth referred to as RPE/choroid) and retina fractions were isolated and stored at −80°C until they were used. Quantitative RT-PCR (QRT-PCR) analyses were performed as previously described in detail.21 In short, real-time PCR analyses were performed in triplicate in a GeneAmp 5700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using standard cycling conditions. Quantitative values were obtained by the cycle number, normalizing genes of interest to β-actin, and determining fold difference between room air and CSE within treatments. See Table 1 for the full list of primers used.

Table 1.

Quantitative RT-PCR Primer Sequences

Statistics

For data consisting of multiple groups and repeated measures, linear regression analyses of the individual animals followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test (P < 0.05) were used; single comparisons were analyzed using Student's t-test assuming equal variance (P < 0.05; Statview; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Fold changes in QRT-PCR experiments were analyzed by Z-test (treatment versus never smokers; P < 0.05) and t-test using the Holm-Sidak method (CSE mice, PBS versus CR2-fH, with α = 5.0%; P < 0.01).

Results

Effect of CR2-fH Treatment on Smoke-Induced Impairment of Visual Function

There is ample evidence that morphologic and cellular alterations in dry AMD lead to vision loss or impairment as measured by changes in visual acuity and contrast sensitivity. In particular, structural changes to BrM, including thickening and lipid deposition, can lead to impaired exchange of waste and nutrients between the RPE and choroid38 as well as a reduction in the generation and delivery of 11-cis-retinal, the chromophore essential for proper visual function, to photoreceptor outer segments.39 However, it is unclear to what degree these changes are reversible.

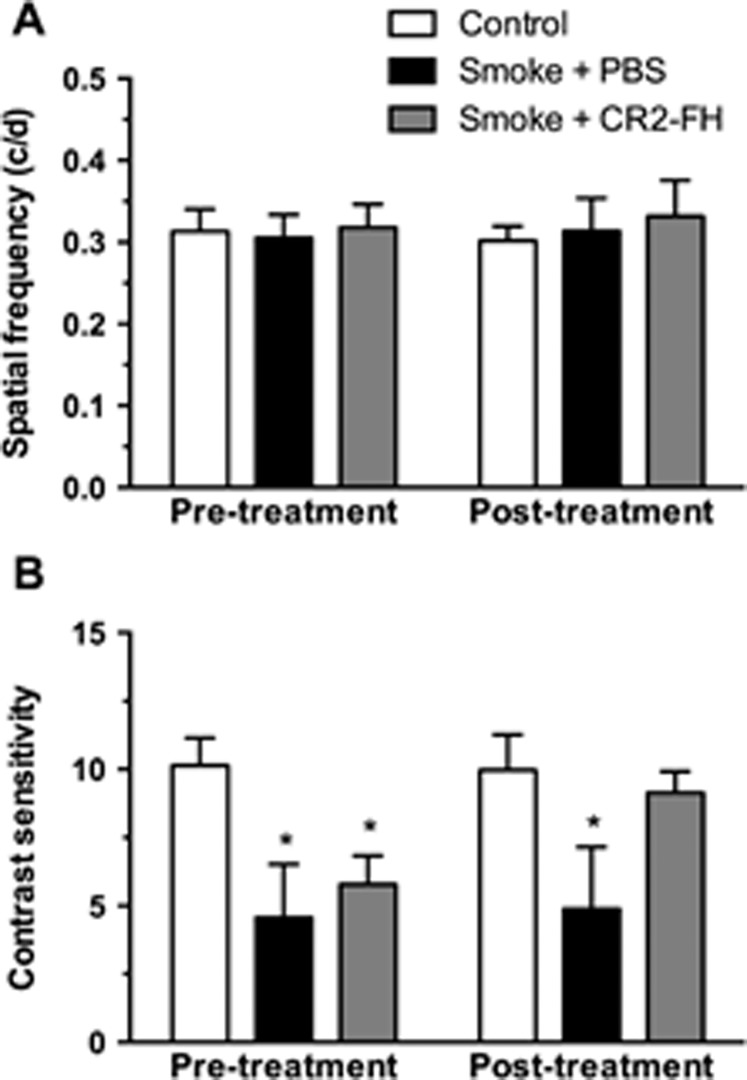

Here, we generated AMD-associated morphologic alterations and loss of contrast sensitivity in mice exposed to long-term smoke inhalation as reported previously.21 After 6 months of CSE, animals were randomly split into two groups and assessed for visual function using optokinetic responses (reported as pretreatment data in Fig. 1). As reported previously, spatial acuity in C57BL/6J mice was not affected by CSE, resulting in acuity measures that did not differ from those of age-matched room air controls (never smokers; Fig. 1A; P = 0.98). However, contrast sensitivity was significantly reduced in CSE mice, which exhibited a significant decrease in contrast sensitivity compared to never smokers (group 1, to be treated with PBS: 4.57 ± 0.97; or group 2, to be treated with CR2-fH: 5.78 ± 0.52; versus never smokers: 10.14 ± 0.41; P < 0.01; Fig. 1B, pretreatment).

Figure 1.

Posttreatment with CR2-fH reverses smoke-induced impairment of contrast sensitivity. Optomotor responses were analyzed in C57BL/6J mice after 6 months of cigarette smoke exposure (CSE) or room air followed by 3 months of treatment with nothing, PBS, or alternative complement pathway inhibitor, CR2-fH. (A) Visual acuity was measured by identifying the spatial frequency threshold at a constant speed (12°/s) and contrast (100%). Spatial frequency thresholds were not affected by CSE or treatment. (B) Contrast sensitivity was measured by taking the reciprocal of the contrast threshold at a fixed spatial frequency (0.131 cyc/deg) and speed (12°/s). We previously determined that this spatial frequency falls within the range of maximal contrast sensitivity for 9-month-old C57BL/6J mice (data not shown). After CSE, mice showed a significant reduction in contrast sensitivity compared to controls, which was still maintained after 3 months of CSE cessation. However, smoke-exposed mice treated with CR2-FH showed a contrast sensitivity that was similar to room air controls and significantly higher than in PBS-treated mice following CSE. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4–6 per condition; *P < 0.05).

After confirming that CSE animals exhibited loss of contrast sensitivity, mice were returned to room air and treated for 3 consecutive months with either CR2-fH given three times per week or PBS, using intraperitoneal injections. CR2-fH has both a targeting domain (SCRs 1–4 of CR2) that binds C3 fragments deposited at sites of complement activation and a complement inhibitory domain (SCRs 1–5 of FH).40 After 3 months of smoking cessation and treatment, animals were retested for visual function (reported as posttreatment data in Fig. 1). As expected, spatial acuity in CSE mice treated with either PBS or CR2-fH did not differ from mice exposed to room air (Fig. 1A; P = 0.44). On the other hand, CSE mice treated with PBS still exhibited a robust decrease in contrast sensitivity (smoke + PBS; 4.89 ± 1.14) compared to never smokers (control; 9.97 ± 0.53; P < 0.001; Fig. 1B, posttreatment). Importantly, contrast sensitivity threshold in CSE mice treated with CR2-fH recovered to levels similar to those of age-matched never smokers (smoke + CR2-fH: 9.97 ± 0.53 versus control never smokers: 9.14 ± 0.39; P = 0.29). Linear regression analysis for pre- and posttreatment contrast sensitivity confirmed the marked improvement in CR2-fH–treated animals (P < 0.0001).

Effect of CR2-fH Treatment on Smoke-Induced Changes in Gene Expression

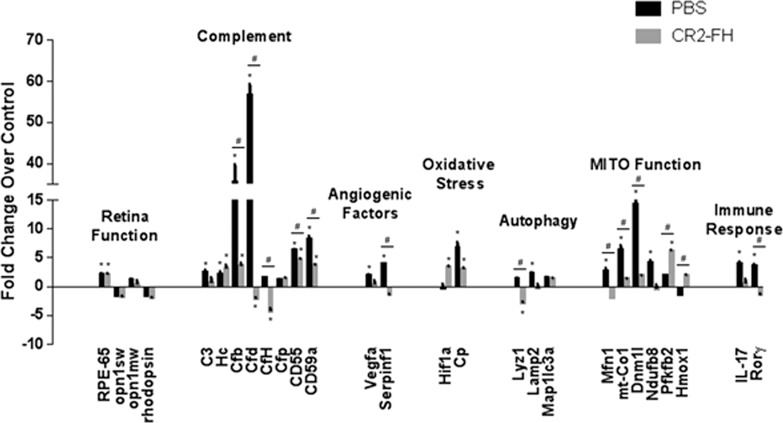

Changes in gene expression following smoke exposure for six gene categories have been shown previously.21 To recap, after 6 months of CSE, expression of genes whose products are involved in photoreceptor cell function, complement inhibition, and inhibition of angiogenic and lysosomal function was downregulated, whereas increases were observed for genes whose products are involved in complement activation, angiogenesis, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial fission and fusion. All of these changes were ameliorated by knocking out FB systemically.21 Here, we asked how cessation of smoking alone, or cessation of smoking coupled with CR2-fH therapy, affects expression of the same set of genes (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Gene expression changes in ocular tissues following cessation of smoke and treatment with CR2-fH. Analysis of marker gene expression in smoke-exposed mice following cessation of cigarette smoke exposure (CSE) and treatment with PBS or alternative complement pathway inhibitor, CR2-fH, using quantitative RT-PCR on cDNA generated from retina and RPE/choroid/sclera fraction. Please note that with the exception of Rho, Opn1sw, and Opn1mw, which were examined in the retina fraction, all other genes were examined in the RPE/choroid/sclera fraction. Quantitative values were obtained by cycle number (Ct value), determining the difference between the mean experimental and control (Actb) ΔCt values for PBS- and CR2-fH–treated mice following CSE versus room air–exposed mice (fold difference). Candidates were examined from a number of categories including photoreceptor cell function (Rho, Opn1sw, Opn1mw, Rpe65), complement activation (C3, Hc, Cfb, Cfd, Cfh, Cd55, Cd59a), control of angiogenesis (Vegfa, Serpinf1), oxidative stress (Hif1a, Cp), autophagy (Lyz1, Lamp2, Klc3), mitochondrial function (Mfn1, mt-Co1, Dnm1l, Ndufb8, Pfkfb1, Hmox1), and immune response (IL-17 and RoRγ). Significant changes were identified in several categories for CR2-fH–treated mice, in particular, suggesting decreased complement activation and enhanced energy production. Statistics represent comparisons between PBS- and CR2-fH-treated animals following CSE versus never smokers and differences between CSE mice treated with PBS versus CR2-fH. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 per condition; *P < 0.05 analyzing fold changes between treatment groups versus never smokers; #P < 0.01 analyzing fold change differences between CSE mice treated with PBS versus CR2-fH).

Three months after smoking cessation, PBS-treated animals had normal levels of gene expression for photoreceptor function, pro- and antiangiogenic factors, oxidative stress, and autophagy. Misregulated genes, on the other hand, involved those mediating mitochondrial fission and fusion, as well as complement activation. Interestingly, a significant increase in factors regulating the complement AP pathway (FB and FD [factor D]) was observed.

The effects of CR2-fH treatment compared to PBS treatment following smoking cessation involved two major categories: energy metabolism and complement activation. Treatment with CR2-fH prevented the massive increase in expression of FB and FD. CR2-fH was also found to reduce mitochondrial stress, as genes affecting mitochondrial fission and fusion were normalized and an increase in the protective response gene heme oxygenase 1 was observed.

Effects of CR2-fH on Morphologic Alterations in RPE-BrM Caused by Constant Smoke Exposure

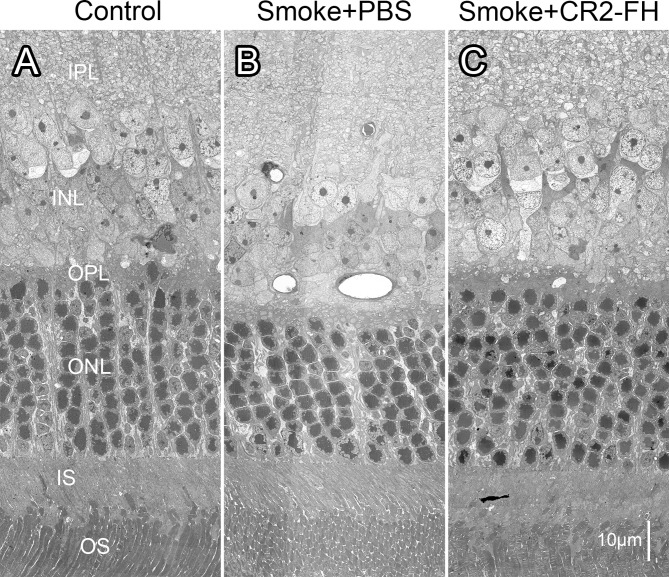

Loss in contrast sensitivity following smoke exposure has previously been shown to be associated with specific morphologic alterations in RPE, BrM, and Müller cells.21 Here, we asked whether these same features play a role in the recovery of visual function in CSE mice treated with CR2-fH. We analyzed electron micrographs obtained from CR2-fH and PBS cohorts and age-matched never smokers, analyzing outer retina structure (Fig. 3) and the RPE/BrM/choroid interface (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

CR2-fH rescues ultrastructural changes in the outer retina in mice following cigarette exposure. Electron micrographs of the outer retina obtained from age-matched mice after 6 months of cigarette smoke exposure (CSE) or room air followed by 3 months of treatment with PBS (B) (smoke + PBS), CR2-fH (C) (smoke + alternative complement pathway inhibitor, CR2-fH), or 3 additional months of room air (A) (control, never smokers) were compared. While all animals had the same number of photoreceptors per row (∼9), the nuclei were more densely packed in the smoke + PBS– when compared to the control and CR2-fH–treated animals. IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; IS, inner segments; OS, outer segments.

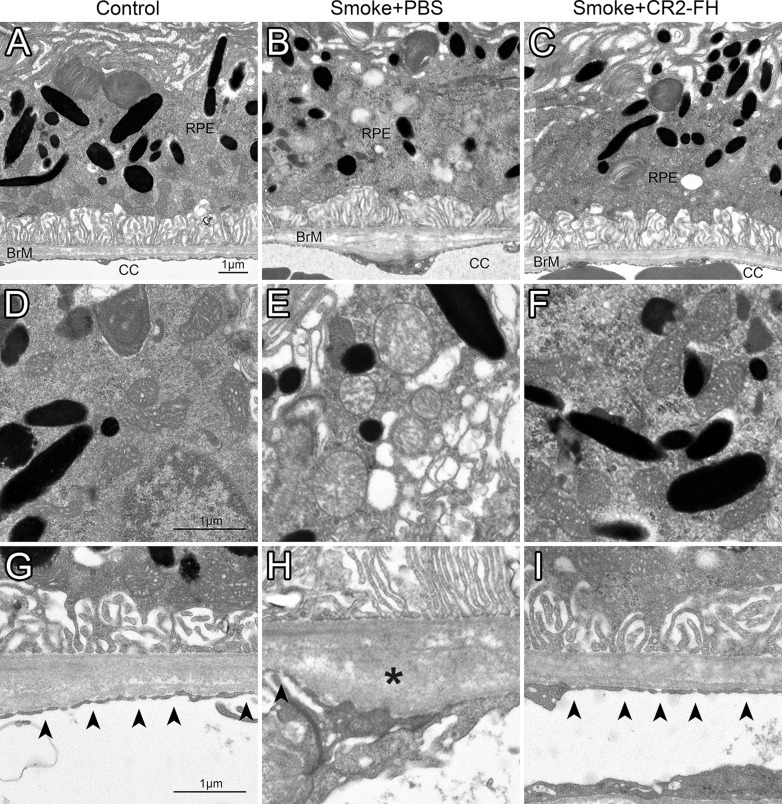

Figure 4.

CR2-fH rescues ultrastructural changes in RPE/BrM/CC complex in mice following cigarette exposure. Electron micrographs of the retinal pigment epithelium/Bruch's membrane/choriocapillaris complex (RPE/BrM/CC) obtained from age-matched mice after 6 months of cigarette smoke exposure (CSE) or room air followed by 3 months of treatment with PBS (smoke + PBS), CR2-fH (smoke + alternative complement pathway inhibitor, CR2-fH), or 3 additional months of room air (control, never smokers) were compared, providing an RPE/BrM/CC overview (A–C), or focusing on mitochondria (D–F) and BrM (G–I). In an animal raised in room air (control, never smoker), BrM exhibits an organized pentalaminar structure consisting of RPE basement membrane, inner collagenous layer, middle elastic layer, outer collagenous layer, and choriocapillaris basement membrane, and the choriocapillaris endothelium has fenestrations (arrowheads) along the entire membrane (A, G). (B, H) The RPE/BrM/CC in a mouse following CSE (smoke + PBS) exhibits pathologic changes. Bruch's membrane is disorganized, no longer showing a pentalaminar structure, and large deposits (asterisks) are present in the outer collagen layer (OCL). Notably, there is significant fenestration loss and/or endothelial cell thickening adjacent to OCL deposits. (C, I) The RPE/BrM/CC appears normal in mice treated with CR2-fH following CSE (smoke + CR2-fH). The morphologic features of mitochondria shown in mice exposed to smoke mitochondria have degraded outer membranes and disorganized cristae (E), but normal appearance in never smokers (D) and mice treated with CR2-fH following CSE (F).

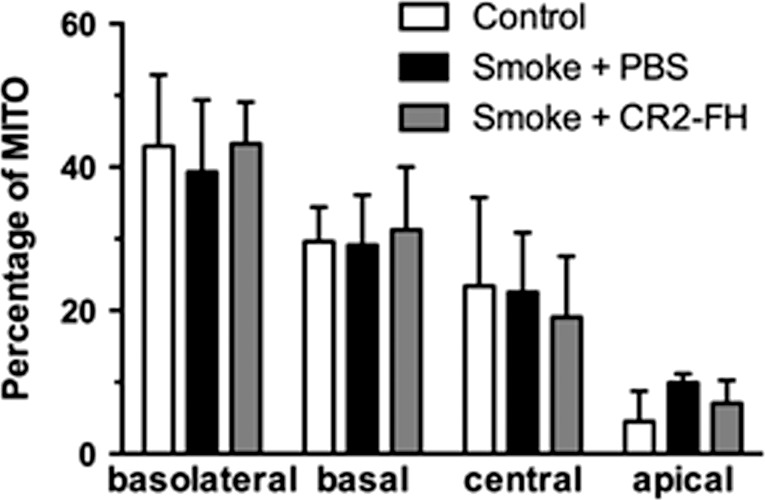

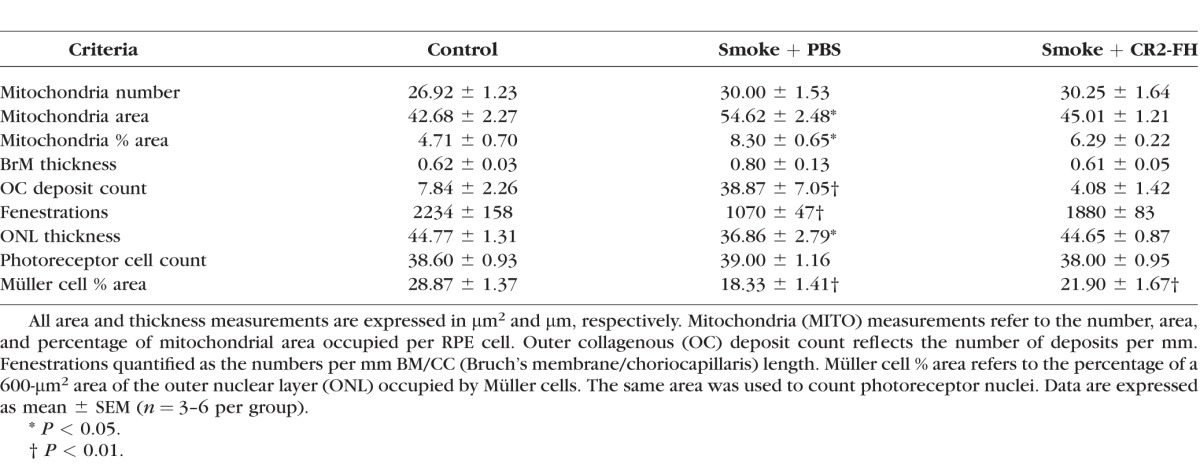

Bruch's membrane is a pentalaminar structure consisting of the basement membrane of the RPE, the inner collagenous layer, the middle elastic layer, the OCL, and the basement membrane of the CC. Bruch's membrane is thicker in CSE mice compared to never smokers. The pentalaminar structure of BrM was disrupted as evidenced by an inconsistent middle elastic layer (Figs. 4B, 4H). Areas of BrM disorganization were especially prevalent near large deposits located in the OCL (asterisks) that are absent in never smokers. These deposits were associated with lower or absent CC fenestration density (arrowheads). In contrast, never smokers exhibit a high fenestration count with few to no OCL deposits. Mitochondria (Figs. 4D–F) were significantly altered in CSE animals, characterized by poorly defined outer membranes and disorganized cristae. Never smokers displayed healthy mitochondria with clearly defined outer membranes and organized cristae. Finally, mitochondria, which in a healthy RPE cell are distributed in a basal to apical gradient but lose this arrangement in unhealthy cells such as those exposed to CSE,21 were found to localize in a pattern that was not different between never smokers and CSE mice in any of the four localization bins analyzed (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results are consistent with previous findings from our lab obtained from animals examined immediately following the completion of the 6-month CSE period, with the exception of the lack of mitochondrial mislocalization.21 Treatment with CR2-fH following CSE reversed all smoke-induced ultrastructural deficits. Bruch's membrane appeared intact, exhibiting the full pentalaminar structure, without any apparent thickening. Few deposits were found in BrM, and fenestrations were evenly distributed along the CC. Likewise, the mitochondrial phenotype also appeared to be healthy, as evidenced by a clear outer membrane and organized cristae.

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial localization is normal 3 months after cessation of smoke exposure. Mitochondrial position was determined from electron micrographs (depicted in Fig. 3) by determining their centroid coordinates as a percentage of the corresponding retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) length and thickness, respectively. Each centroid was subsequently assigned to one of four bins (basolateral, basal, central, or apical) and expressed as percent of total mitochondria (MITO). Mitochondria are localized predominantly to the basolateral and basal compartments of the RPE cells with fewer localized in the central and apical portions in never smokers. While we previously reported that cigarette smoke exposure (CSE) affects the mitochondrial distribution in C57BL/6J mice after 6 months,21 with mitochondria exhibiting an apical shift from the basal to central compartment, mitochondrial distribution is back to normal 3 months after the cessation of CSE (smoke + PBS), and is not further affected by complement inhibition (smoke + CR2-fH).

Electron microscopy results were quantified (Table 2 based on data such as those in Figs. 3, 4) focusing on morphologic correlates of energy metabolism in the RPE (mitochondria), nutrient and waste transport (BrM thickness, OCL deposit count, and fenestrations in the CC), and photoreceptor function (ONL thickness, photoreceptor cell counts, and size of Müller cells). Mitochondria were found to be significantly larger in CSE mice compared to never smokers (P < 0.05) and made up a larger percentage of total RPE cell area (P < 0.05). Mitochondrial morphology completely recovered during the 3-month CR2-fH treatment period. The total number of mitochondria was unchanged between all three groups as was their localization. A thickening of BrM in CSE mice was observed compared to never smokers; however, this did not reach statistical significance. Bruch's membrane was of normal thickness in animals treated with CR2-fH. Cigarette smoke exposure triggers the formation of OCL deposits in BrM,21 which are maintained in CSE mice treated with vehicle (P < 0.01) but removed in those treated with CR2-fH. Fenestrations counted along 100-μm BrM/CC sections revealed, on average, a ∼53% decline of the fenestrations in CSE mice (P = 0.002), a deficit that was reduced to ∼17% in mice treated with CR2-fH, which is not statistically different from never smokers (P = 0.06). In addition, we measured the thickness of the ONL, photoreceptor cell counts, and the area of the ONL occupied by Müller cells. Smoke-exposed WT mice had a significantly thinner ONL when compared to room air controls (P < 0.05), which is due to Müller cell hypotrophy (P < 0.01) as opposed to a loss in photoreceptors. In contrast, treatment with CR2-fH restored the thickness of the ONL to normal levels (P < 0.05) even though there was still evidence of Müller cell hypotrophy (P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Quantification of Morphologic Structures From Mice Treated With Alternative Complement Pathway Inhibitor CR2-FH Following Cigarette Smoke Exposure (CSE)

Discussion

While we confirmed and extended our previous data on retinal structure and function in mice following long-term smoke exposure, we additionally addressed two specific questions: First, are CSE-induced changes reversible upon smoke cessation; and second, since the pathologic changes are complement dependent,21 can we accelerate their resolution with complement inhibitory therapy?

First, are the structural and functional changes induced by CSE reversible upon cessation of smoking (smoke + PBS)? Previously, we showed that while spatial acuity is retained in mice after 6 months of CSE, contrast sensitivity is reduced by ∼60%. Allowing mice to recover in room air for 3 months only marginally affected contrast sensitivity, as the threshold was still suppressed by ∼50%. Similarly, the thinning of the ONL observed after 6 months of smoke is retained after 3 months of recovery, as are Müller cell atrophy, the presence of large numbers of OCL deposits in BrM, and the increase in mitochondrial area. Overall BrM thickness after 3 months of room air was still increased in PBS mice by ∼30%; however, this difference was no longer significant based on the large variability in BrM thickness in CSE mice. Finally, the mislocalization of mitochondria observed after CSE was no longer apparent following recovery in 3 months of room air. In patients, the question whether smoke-induced pathology is reversible has not yet been addressed. However, Neuner and colleagues41 have posed a related question in the Muenster Aging and Retina Study. The group followed aged smokers and nonsmokers without AMD over a median of 30.9 months and reported their adjusted risk ratios for incident AMD. Of the 9.6% of subjects who progressed to AMD, the adjusted risk ratio in current smokers versus never smokers was 3.25 (95% confidence interval [1.50–7.06]), but was still significantly elevated by 1.28 (0.70–2.33) in former smokers versus never smokers.

Second, is continued complement activation required to maintain the structural and functional deficits observed in CSE mice, or can damage be reversed with complement inhibition? Our group previously described a recombinant site-targeted inhibitor of the complement AP, CR2-fH. This fusion protein consists of the AP-inhibitory domain of mouse FH linked to a CR2 targeting fragment that binds membrane-bound complement activation products, and CR2-fH is orders of magnitude more effective at blocking the AP in vitro than native FH.25 CR2-fH has been shown to reduce complement activation, inflammation, and injury to the colon in a model of chronic colitis,42 to block the progression of both acute and chronic autoimmune demyelinating disease in an experimental encephalomyelitis study,43 and to attenuate deficits associated with cerebral and cardiac ischemia–reperfusion injury.44,45 CR2-fH has also been used to inhibit CNV, a process requiring AP activation,26 as well as smoke-induced lipid deposition in cultured RPE cells.16 However, no studies have been conducted to investigate the efficacy of this AP inhibitory protein in a dry AMD model, particularly using a therapeutic rather than preventative paradigm. Here, we show the first conclusive evidence that CR2-fH is effective in reducing and reversing smoke-induced ocular pathology in a novel smoking cessation model. We previously showed that preventing AP activation (FB KO mice) prevented the development of all CSE-mediated structural and functional alterations.21 Here, we asked whether CR2-fH can accelerate the reversal of pathology when applied for a 12-week period post smoking cessation. Remarkably, we found that smoke-induced decreases in contrast sensitivity can be completely reversed following treatment with CR2-fH. Functional improvement was found to correlate with an attenuation of morphologic differences in RPE/BrM/CC. Not only did CR2-fH reverse the trend toward a thicker BrM and increases in OCL deposit formation caused by CSE, but it also reversed alterations in the CC, including restoration of fenestrations in areas of close proximity to OCL deposits. In addition, CR2-fH was effective in reversing all mitochondrial impairments observed under smoke conditions. Our data suggest that inhibition of the complement AP is paramount to reversing ocular smoke pathology, and CR2-fH is a potent inhibitor of this pathway. Further experiments need to be conducted to determine the therapeutic window, most effective dosage, and ideal delivery modality for this AP inhibitor following CSE or other complement-dependent AMD models. It will be of great interest to determine how these data relate to the ocular changes found in GA patients, in particular in light of the recent findings of the phase II clinical trial for lampalizumab,46 in which an anti-FD monoclonal antibody applied intravitreally appeared to reduce geographic atrophy (GA) lesion size in a subpopulation of patients.

How might smoke-induced ocular pathology be reversible with complement inhibition? Affected structures such as drusen, BrM, RPE, and CC exhibit signs of complement activation and contain neoepitopes that continue to trigger complement activation. Hence, in the absence of sufficient complement inhibition, de novo complement activation triggered by the continued presence of neoantigens29 and complement amplification through the complement AP will continue to drive complement activation and maintain the damaged structures even in the absence of the toxic stimulus, which in the present case is smoking. This hypothesis is supported by our gene expression study, indicating a rebound effect of AP inhibition, since both of the required activators of the AP are significantly upregulated upon cessation of smoking but return to normal levels in the presence of CR2-fH. It is plausible that in the absence of continued complement activation, complement-mediated damage leading to the growth of the lesions is reduced, and reparative mechanisms including removal of debris by macrophages, and repair of cellular metabolism by mitochondrial biogenesis, can occur. However, the exact mechanism whereby CR2-fH slows down or reverses the progression of disease requires further investigation.

In summary, there is a growing body of evidence linking oxidative stress, cigarette smoking, and complement activation to the development and progression of AMD. Our data provided herein demonstrate that CSE in mice causes behavioral and morphologic defects in the retina, RPE, BrM, and CC, similar to those observed in patients with dry AMD, and it persists post smoking cessation. CR2-fH administered to mice following CSE provides the first evidence that complement-based therapy is effective in treating smoke-induced ocular pathology, and suggests that this line of therapy may be effective in treating dry AMD in humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Luanna Bartholomew, PhD, for critical review.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01EY019320, R01 NHLBI 091944, NIH EY015128, NIH EY02576, and EY014800; Department of Veterans Affairs I01 RX000444; an unrestricted grant to the Medical University of South Carolina from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB), Inc., New York, New York, United States; Vision Core, an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Moran Eye Center; Edward N. and Della L. Thome Memorial Foundation grant for Age-Related Macular Degeneration Research. Animal studies were conducted in a facility constructed with support from the NIH (C06 RR015455). CA, ST, and BR are patent holders for the use of CR2-fH in complement-dependent diseases. This patent is licensed to Alexion Therapeutics.

Disclosure: A. Woodell, None; B.W. Jones, None; T. Williamson, None; G. Schnabolk, None; S. Tomlinson, P; C. Atkinson, P; B. Rohrer, P

References

- 1. Wong WL,, Su X,, Li X,, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014; 2: e106–e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferris FL,, III, Wilkinson CP,, Bird A,, et al. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013; 120: 844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freund KB,, Zweifel SA,, Engelbert M. Do we need a new classification for choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration? Retina. 2010; 30: 1333–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown MM,, Brown GC,, Stein JD,, Roth Z,, Campanella J,, Beauchamp GR. Age-related macular degeneration: economic burden and value-based medicine analysis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005; 40: 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang JC,, Cao S,, Wang A,, et al. CFH Y402H polymorphism is associated with elevated vitreal GM-CSF and choroidal macrophages in the postmortem human eye. Mol Vis. 2015; 21: 264–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Langford-Smith A,, Keenan TD,, Clark SJ,, Bishop PN,, Day AJ. The role of complement in age-related macular degeneration: heparan sulphate, a ZIP code for complement factor H? J Innate Immun. 2014; 6: 407–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clark SJ,, Bishop PN. Role of factor H and related proteins in regulating complement activation in the macula, and relevance to age-related macular degeneration. J Clin Med. 2015; 4: 18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dikmetas O,, Kadayifcilar S,, Eldem B. The effect of CFH polymorphisms on the response to the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) with intravitreal ranibizumab. Mol Vis. 2013; 19: 2571–2578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ni Dhubhghaill SS Cahill MT, Campbell M, Cassidy L, Humphries MM, Humphries P. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and age-related macular degeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010; 664: 437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chakravarthy U,, Augood C,, Bentham GC,, et al. Cigarette smoking and age-related macular degeneration in the EUREYE Study. Ophthalmology. 2007; 114: 1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mitchell P,, Wang JJ,, Smith W,, Leeder SR. Smoking and the 5-year incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002; 120: 1357–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khan JC,, Thurlby DA,, Shahid H,, et al. Smoking and age related macular degeneration: the number of pack years of cigarette smoking is a major determinant of risk for both geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90: 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bertram KM,, Baglole CJ,, Phipps RP,, Libby RT. Molecular regulation of cigarette smoke induced-oxidative stress in human retinal pigment epithelial cells: implications for age-related macular degeneration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009; 297: C1200–C1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pons M,, Marin-Castano ME. Cigarette smoke-related hydroquinone dysregulates MCP-1, VEGF and PEDF expression in retinal pigment epithelium in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2011; 6: e16722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kew RR,, Ghebrehiwet B,, Janoff A. Cigarette smoke can activate the alternative pathway of complement in vitro by modifying the third component of complement. J Clin Invest. 1985; 75: 1000–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kunchithapautham K,, Atkinson C,, Rohrer B. Smoke exposure causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid accumulation in retinal pigment epithelium through oxidative stress and complement activation. J Biol Chem. 2014; 289: 14534–14546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fujihara M,, Nagai N,, Sussan TE,, Biswal S,, Handa JT. Chronic cigarette smoke causes oxidative damage and apoptosis to retinal pigmented epithelial cells in mice. PLoS One. 2008; 3: e3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang AL,, Lukas TJ,, Yuan M,, Du N,, Handa JT,, Neufeld AH. Changes in retinal pigment epithelium related to cigarette smoke: possible relevance to smoking as a risk factor for age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2009; 4: e5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jia L,, Liu Z,, Sun L,, et al. Acrolein, a toxicant in cigarette smoke, causes oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in RPE cells: protection by (R)-alpha-lipoic acid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Espinosa-Heidmann DG,, Suner IJ,, Catanuto P,, Hernandez EP,, Marin-Castano ME,, Cousins SW. Cigarette smoke-related oxidants and the development of sub-RPE deposits in an experimental animal model of dry AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 729–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Woodell A,, Coughlin B,, Kunchithapautham K,, et al. Alternative complement pathway deficiency ameliorates chronic smoke-induced functional and morphological ocular injury. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e67894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jobse BN,, McCurry CA,, Morissette MC,, Rhem RG,, Stampfli MR,, Labiris NR. Impact of inflammation emphysema, and smoking cessation on V/Q in mouse models of lung obstruction. Respir Res. 2014; 15: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koike K,, Ishigami A,, Sato Y,, et al. Vitamin C prevents cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema in mice and provides pulmonary restoration. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014; 50: 347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duan MC,, Tang HJ,, Zhong XN,, Huang Y. Persistence of Th17/Tc17 cell expression upon smoking cessation in mice with cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013; 2013: 350727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang Y,, Qiao F,, Atkinson C,, Holers VM,, Tomlinson S. A novel targeted inhibitor of the alternative pathway of complement and its therapeutic application in ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2008; 181: 8068–8076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rohrer B,, Long Q,, Coughlin B,, et al. A targeted inhibitor of the alternative complement pathway reduces angiogenesis in a mouse model of age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 3056–3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thurman JM,, Renner B,, Kunchithapautham K,, et al. Oxidative stress renders retinal pigment epithelial cells susceptible to complement-mediated injury. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284: 16939–16947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bandyopadhyay M,, Rohrer B. Matrix metalloproteinase activity creates pro-angiogenic environment in primary human retinal pigment epithelial cells exposed to complement. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 1953–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Joseph K,, Kulik L,, Coughlin B,, et al. Oxidative stress sensitizes RPE cells to complement-mediated injury in a natural antibody-, lectin pathway- and phospholipid epitope-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2013; 288: 12753–12765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matsumoto M,, Fukuda W,, Circolo A,, et al. Abrogation of the alternative complement pathway by targeted deletion of murine factor B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997; 94: 8720–8725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Watson ES,, Jones AB,, Ashfaq MK,, Barrett JT. Spectrophotometric evaluation of carboxyhemoglobin in blood of mice after exposure to marijuana or tobacco smoke in a modified Walton horizontal smoke exposure machine. J Anal Toxicol. 1987; 11: 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yao H,, Arunachalam G,, Hwang JW,, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase protects against pulmonary emphysema by attenuating oxidative fragmentation of ECM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107: 15571–15576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yao H,, Chung S,, Hwang JW,, et al. SIRT1 protects against emphysema via FOXO3-mediated reduction of premature senescence in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012; 122: 2032–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen ZH,, Kim HP,, Sciurba FC,, et al. Egr-1 regulates autophagy in cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2008; 3: e3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marc RE,, Liu W. Fundamental GABAergic amacrine cell circuitries in the retina: nested feedback concatenated inhibition, and axosomatic synapses. J Comp Neurol. 2000; 425: 560–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anderson JR,, Jones BW,, Yang JH,, et al. A computational framework for ultrastructural mapping of neural circuitry. PLoS Biol. 2009; 7: e1000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stoppelkamp S,, Riedel G,, Platt B. Culturing conditions determine neuronal and glial excitability. J Neurosci Methods. 2010; 194: 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mettu PS,, Wielgus AR,, Ong SS,, Cousins SW. Retinal pigment epithelium response to oxidant injury in the pathogenesis of early age-related macular degeneration. Mol Aspects Med. 2012; 33: 376–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Owsley C,, McGwin G,, Jackson GR,, et al. Effect of short-term, high-dose retinol on dark adaptation in aging and early age-related maculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 1310–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holers VM,, Rohrer B,, Tomlinson S. CR2-mediated targeting of complement inhibitors: bench-to-bedside using a novel strategy for site-specific complement modulation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013; 735: 137–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Neuner B,, Komm A,, Wellmann J,, et al. Smoking history and the incidence of age-related macular degeneration--results from the Muenster Aging and Retina Study (MARS) cohort and systematic review and meta-analysis of observational longitudinal studies. Addict Behav. 2009; 34: 938–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Elvington M,, Schepp-Berglind J,, Tomlinson S. Regulation of the alternative pathway of complement modulates injury and immunity in a chronic model of dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015; 179: 500–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hu X,, Tomlinson S,, Barnum SR. Targeted inhibition of complement using complement receptor 2-conjugated inhibitors attenuates EAE. Neurosci Lett. 2012; 531: 35–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Elvington A,, Atkinson C,, Zhu H,, et al. The alternative complement pathway propagates inflammation and injury in murine ischemic stroke. J Immunol. 2012; 189: 4640–4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Atkinson C,, He S,, Morris K,, et al. Targeted complement inhibitors protect against posttransplant cardiac ischemia and reperfusion injury and reveal an important role for the alternative pathway of complement activation. J Immunol. 2010; 185: 7007–7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rhoades W,, Dickson D,, Do DV. Potential role of lampalizumab for treatment of geographic atrophy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015; 9: 1049–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]