Abstract

Sotos syndrome is an overgrowth syndrome caused by mutations within the functional domains of NSD1 gene coding for NSD1, a multidomain protein regulating chromatin structure and gene expression. In particular, PHDVC5HCHNSD1 tandem domain, composed by a classical (PHDV) and an atypical (C5HCH) plant homeo-domain (PHD) finger, is target of several pathological missense-mutations. PHDVC5HCHNSD1 is also crucial for NSD1-dependent transcriptional regulation and interacts with the C2HR domain of transcriptional repressor Nizp1 (C2HRNizp1) in vitro. To get molecular insights into the mechanisms dictating the patho-physiological relevance of the PHD finger tandem domain, we solved its solution structure and provided a structural rationale for the effects of seven Sotos syndrome point-mutations. To investigate PHDVC5HCHNSD1 role as structural platform for multiple interactions, we characterized its binding to histone H3 peptides and to C2HRNizp1 by ITC and NMR. We observed only very weak electrostatic interactions with histone H3 N-terminal tails, conversely we proved specific binding to C2HRNizp1. We solved C2HRNizp1 solution structure and generated a 3D model of the complex, corroborated by site-directed mutagenesis. We suggest a mechanistic scenario where NSD1 interactions with cofactors such as Nizp1 are impaired by PHDVC5HCHNSD1 pathological mutations, thus impacting on the repression of growth-promoting genes, leading to overgrowth conditions.

INTRODUCTION

The Nuclear receptor-binding SET (Su(var) 3–9, Enhancer of zeste, Trithorax) domain protein 1 (NSD1), is a large multi-domain nuclear protein (2696 amino acids) belonging to a family of three structurally similar mammalian methyltransferases including NSD1, NSD2 and NSD3, that have been all linked to multiple diseases and cancer types (1–4). As NSD prototype, NSD1 is characterized by the presence of different chromatin related domains including two proline–tryptophan–tryptophan–proline domains (PWWP), five plant homeodomains (PHD), a PHD finger-like Cys–His rich domain (C5HCH) (sometimes called PHDVI), acquired late in the evolution of the NSD family and a catalytic SET domain (5–7). In vitro NSD1-SET domain catalyzes the mono- and di-methylation of H3K36 and tri-methylation of H4K20, even though discrepancies exist as to the level and the target(s) of methylation (8–13). Importantly, mutations in the NSD1 gene lead to different aberrant developmental processes: fusion to Nup98 nucleoporin gene is associated with de novo childhood acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (14–16), and NSD1 mutations and translocations lead to Weaver and Sotos syndromes, inherited congenital malformation overgrowth syndromes leading to delayed motor and cognitive development (17–21). Indeed, mouse NSD1 knock out data show that the protein is essential for correct embryonic development (6). Although the different patho-physiological mechanisms dictated by NSD1 remain elusive, several lines of evidence suggest its direct involvement in context-dependent transcriptional repression or activation. In colon cancer cell lines NSD1 binds near various promoter elements tuning the levels of the various H3K36 methylation forms within the occupied promoter proximal region, regulating multiple genes involved in developmental processes, such as cell growth/cancer and bone morphogenesis (9). Conversely, in neuroblastoma cells NSD1 displays tumour suppressor like properties promoting MEIS1-mediated gene transcriptional repression (8). NSD1 bi-functional transcriptional regulation might be also related not only to the presence of two nuclear-interaction domains, NID−L and NID+L (5) but also to the presence of the other chromatin binding domains, that are expected to confer to NSD1 additional chromatin related functions, besides its SET-dependent methyltransferase activity. As a matter of fact, the fifth PHD finger and the adjacent C5HCH domain (PHDVC5HCHNSD1) have been shown to have context-dependent activation or repression activities with different patho-physiological outcomes. On the one hand, PHDVC5HCHNSD1 is a hot spot for the developmental overgrowth Sotos syndrome, as assessed by the presence of 17 pathological point-mutations within this domain (Supplementary Table S1). On the other hand, in AML context the same tandem domain contributes to inappropriate Hoxa7 and HoxA9 genes activation (22). This is in keeping with the chromatin associated functions generally attributed to these evolutionarily conserved Zn2+ binding ‘reader/effector’ modules (∼60 aminoacids long). PHD fingers usually interpret histones post-translational modifications (H3K4 vs. H3K4me3/2; H3R2me0 vs. H3R2me2; H3K36me3; H3K14ac) in a modification and context-specific fashion, thus promoting chromatin changes and/or protein recruitment (23,24). Consistent with its putative role as chromatin reader, murine PHDVC5HCHNSD1 (99% identity with human PHDVC5HCHNSD1 (Supplementary Figure S1) binds biotinylated H3K4me31–21 and H3K9me31–21 peptides in vitro (25), even though this interaction has been recently challenged (26). In fact, GST-pulldown assays using unfractionated calf-thymus histones or biotinylated histone peptides did not prove evidence of histone binding to PHDVC5HCHNSD1, thus raising a conflict in literature about its actual role as epigenetic reader (26). Notably, PHD fingers are emerging as a robust-conserved structural scaffold working as versatile non-histone binding domains, thereby extending their role to diverse cellular processes, far beyond the well documented histone tail interpretation (27,28). In line with the multifaceted role of PHD fingers, PHDVC5HCHNSD1 seems to function as a hub for the interaction with other proteins/domains critical for transcriptional activity, such as the C2HR domain of the transcriptional repressor Nizp1 (NSD1 interacting Zinc-finger protein), one of the few documented NSD1 interactors (7,25,26,29). Nizp1, is a poorly characterized multidomain protein, expressed in several tissues containing an N-terminal SCAN box, a repressor KRAB domain, an atypical C2HR Zinc-finger motif (C2HRNizp1) followed by four classical C2H2-type Zinc-fingers (7,29). Intriguingly, according to biochemical in-vitro experiments the interaction with C2HRNizp1 seems to be a unique peculiarity of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 (7,26), thus implying a functional divergence within the NSD protein family. In order to move a step further in the comprehension of the molecular mechanisms dictating PHDVC5HCHNSD1 patho-physiological relevance, we solved its NMR solution structure and provided also a structural rationale for the effects of seven Sotos syndrome point-mutations. To investigate the potential role of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 as structural platform for multiple interactions we characterized its binding to histone H3 peptides and to C2HRNizp1 by ITC and NMR. We observed only very weak electrostatic interactions with histone H3 N-terminal tail, conversely we proved the existence of a specific interaction (Kd∼ 4 μM) between PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1. We also solved the solution structure of C2HRNizp1 and generated a three-dimensional model of its complex with PHDVC5HCHNSD1 corroborated by site-directed mutagenesis studies. We suggest a mechanistic scenario where NSD1 interactions with cofactors, such as Nizp1 are impaired by PHDVC5HCHNSD1 pathological mutations, thus impacting on the repression of growth-promoting genes, and ultimately leading to overgrowth conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation for NMR and binding assays

Murine NSD1 PHDvC5HCH (Glu2117–Asp2207), (corresponding to residues Glu2116–Asp2206 in the human sequence NM_022455.4) was amplified from a pSG5 vector containing the cDNA for murine NSD1 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_008739.3). Murine C2HRNizp1 (residues Glu397–Lys434) was amplified from a pCVM vector containing the cDNA coding for mouse Nizp1 (protein NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_032752.1). Both plasmids were kindly provided by Prof. Chambon (Strasbourg, France). pETM11 and pETM41 (EMBL) plasmids were used to express His-tagged-PHDvC5HCHNSD1 and His-MBP-tagged-C2HRNizp1 proteins, respectively. The tags were removed by cleavage with TEV-protease. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by standard overlap extension methods. The DNA constructs were sequenced by Eurofins (Milan, Italy). Both protein domains were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells at 28°C overnight after induction with 1mM isopropyl thio-β-d-galactoside (IPTG), in LB medium supplemented with 0.2 mM ZnCl2. Uniformly 15N- and 13C-15N-labeled PHDvC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 were expressed by growing E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells in minimal bacterial medium containing 15NH4Cl, with or without 13C-d-glucose as sole nitrogen and carbon sources. Proteins were purified as described in (30). For binding assays with histone peptide arrays PHDvC5HCHNSD1 was cloned into pETM30 expression vector (EMBL) containing an N-terminal His-GST tag. As control only His-GST was used. The molecular masses of the recombinant proteins were checked by mass spectrometry (MALDI). Synthetic histone H3 peptides (H31–10, H31–21, H31–37, H3K4me31–21, H3K9me31–21) were C-amidated. C2HRNizp1 peptides used for ITC and NMR titrations were N-acetylated and C-amidated. They were purchased from Caslo Lyngby, Denmark. Peptide purity (>98%) was confirmed by HPLC and mass spectrometry. The NMR buffer of both PHDvC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 contained 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.3, 0.15 M NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 μM ZnCl2 (28,31) with 0.15 mM 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS). D2O was 10% (v/v) or 100% depending on the experiments.

NMR spectroscopy and resonance assignment

NMR experiments were performed at 295 K on a Bruker Avance 600 MHz equipped with inverse triple-resonance cryoprobe and pulsed field gradients (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). Typical sample concentration was 0.3–0.4 mM. Data were processed using NMRPipe (32) or Topspin 3.2 (Bruker) and analyzed with CCPNmr Analysis 2.1 (33). The 1H, 13C, 15N chemical shifts of the backbone atoms of both PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 were obtained from three-dimensional HNCA, CBCA(CO)NH, CBCANH, HNCO experiments. Side chain resonances were assigned through H(CCO)NH, CC(CO)NH, HCCH–TOCSY experiments (34) and classical 1H–1H 2D-TOCSY (Total Correlation Spectroscopy). The resonances of the aromatic side chains atoms were assigned using 1H–13C HSQC, (HB)CB(CGCD)HD and the 2D TOCSY and NOESY (Nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy) experiments in H2O and in D2O. The tautomeric state of the imidazole rings of the histidines were determined performing 2D 1H–15N HMQC (Heteronuclear Multiple Quantum Coherence) long-range experiments with transfer delay optimized to transfer the coherence from the Hϵ1 and Hδ2 atoms to the Nϵ2 and Nδ1 atoms (τ = 11 ms) and analyzing the peaks pattern according to (35). Proton–proton distance constraints were obtained from 15N and 13C separated three-dimensional NOESY spectra, 2D 1H–1H NOESY in D2O and H2O employing 100 ms mixing times. φ/ψ restraints were obtained from backbone chemical shifts using TALOS-N (36). Hydrogen bond restraints were defined from slow-exchanging amide protons identified after exchange in D2O. 1H–15N residual dipolar couplings were measured in isotropic and anisotropic phases generated by an axially compressed acrylamide gel (8%) as described in (37).

Relaxation experiments

Heteronuclear {1H} 15N nuclear Overhauser enhancement, longitudinal and transversal 15N relaxation rates (R1, R2) were measured using standard 2D methods (38). For R1 and R2 experiments a duty-cycle heating compensation was used (39), the two decay curves were sampled at 13 (ranging from 50 to 2000 ms) and 11 (from 12 to 244 ms) different time points, respectively. Both R1 and R2 experiments were collected in random order and using a recovery delay of 2.5 s. R1 and R2 values were fitted to a 2-parameter exponential decay from the intensities using the fitting routine implemented in the analysis program NMRView (40), duplicate measurements are used to determine the uncertainty in the relaxation rate by Monte Carlo methods in NMRView. The tumbling correlation time (τc) was estimated from R2/R1. Only residues corresponding to non-overlapping peaks, with heteronuclear NOE > 0.65 were used, residues with anomalous short transverse relaxation time T2 were excluded (41). HSQC spectra measured in an interleaved fashion with and without 4 seconds of proton saturation during recovery delay were recorded for the {1H}–15N heteronuclear NOE experiments. The corresponding values were obtained from the ratio between saturated and unsaturated peaks intensities. The uncertainty was calculated as the standard deviation of the noise in the spectrum divided by the intensity of the reference peak.

Structure calculations and validation

PHDvC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 structures were calculated with ARIA 2.3.2 (42) in combination with CNS using experimentally derived restraints (Table 1). All NOEs were assigned manually and calibrated by ARIA, the automated assignment was not used. A total of eight iterations was performed, computing 20 structures in the first seven iterations and 200 in the last iteration. The ARIA default water refinement was performed on the 40 best structures of the final iteration. Initial structures were calculated without Zn2+ restraints to verify the position and the geometry of the metal ion ligands, so that the residues involved in Zn2+ binding could be identified in an unbiased manner. Several NOEs were observed between metal coordinating residues. After unequivocal identification of the metal coordinating residues, in final refinement calculations the geometry of the Zn2+ coordination was fixed through covalent bonds and angles in the CNS parameters (dZn-Sγ = 2.3 Å; dZn-Nϵ2,Nδ1 = 2.0 Å tetrahedral angle geometry around Zn2+ ion, i.e. Sγ–Zn–Sγ = 109.5°, Sγ–Zn–(Nδ1 or Nϵ2) = 109.5°); the proper angles and distances for Zn2+ ions coordinating residues were maintained also during water refinement. PROCHECK-NMR (43) and iCING (44) were used to assess the structural quality. The family of the 15 lowest energy structures (no distance or torsional angle restraints violations >0.5 Å or >5°, respectively) of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 have been deposited in the PDB (PDB accession codes 2naa and 2nab, respectively). Chemical shift and restraints lists used for structure calculations have been deposited in BioMagResBank (PHDvC5HCHNSD1 accession code: 25933; C2HRNizp1 accession code 25934). Electrostatic potential maps were calculated using APBS plugin of PyMOL (45). Figures were generated using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7.4 Schrödinger, LLC).

Table 1. Summary of conformational constraints and statistics for the 15 best structures of PHDvC5HCHNSD1.

| Restraints informationa,b | <SA>c |

| Total number of experimental distance restraints | 1344 |

| NOEs (intraresidual/sequential/medium/long) | 631/273/137/303 |

| Zn2+ coordination restraints | 16 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 7 |

| Dihedral angle restraints (Φ/Ψ) | 57/57 |

| Residual dipolar couplingsd | 22 |

| Deviation from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0031 ± 0.0001 |

| Angles (°) | 0.498 ± 0.012 |

| Coordinate r.m.s. deviation (Å)e | |

| Ordered backbone atoms (N, Cα, C’) | 0.67 ± 0.09 |

| Ordered heavy atoms | 1.06 ± 0.09 |

| Ramachandran quality parameters (%)e | |

| Residues in most favored regions | 89.40% |

| Residues in allowed regions | 10.60% |

a No distance restraint in any of the structures included in the ensemble was violated by more then 0.5 Å.

b No dihedral angle restraints in any of the structures included in the ensemble was violated by more than 5°.

c Simulated annealing, statistics refers to the ensemble of 15 structures with the lowest energy.

d RDC restraints have been used only for residues adopting regular secondary structure.

e Root mean square deviation between the ensemble of structures <SA> and the lowest energy structure and Ramachandran quality parameters calculated on residues Asp2119–Asp2205.

NMR binding assays

Protein concentrations were determined by UV spectroscopy using the predicted extinction coefficients of 12490 and 6990 M−1cm−1 for PHDvC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1, respectively. Peptide concentrations were estimated from their dry-weight. In order to minimize dilution and NMR signal loss, titrations were carried out by adding to the 15N labeled protein samples (typically 0.2–0.3 mM) small aliquots of concentrated (15 mM) peptides or proteins (1–2 mM) stock solutions. All the solutions were prepared in NMR buffer. For each titration point (stepwise addition of up to 12 and 2 equivalents for histone H3 peptides and for PHDvC5HCHNSD1/C2HRNizp1 titrations, respectively) a 2D water-flip-back 15N-edited HSQC spectrum was acquired with 512 (100) complex points, 55 ms (60 ms) acquisition times, apodized by 60° shifted squared (sine) window functions and zero filled to 1024 (512) points for 1H (15N), respectively. Assignment of the PHDvC5HCNSD1 in the presence of histone peptides was made by following individual cross-peaks through the titration series. The assignments of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and of C2HRNizp1 amides were achieved acquiring HNCA, CBCA(CO)NH experiments in the presence of a 1.5 fold excess of unlabelled CH2RNizp1 and unlabelled PHDVC5HCHNSD1, respectively. For each residue the weighted average of the 1H and 15N chemical shift perturbation (CSP) was calculated as CSP = [(Δδ2HN + Δδ2N/25)/2]1/2 (46).

Isothermal titration calorimetry thermodynamic analysis

ITC titration was performed using a VP-ITC isothermal titration calorimeter (MicroCal LLC, Northampton, MA, USA). Recombinant proteins and synthetic peptides were dialyzed against the same buffer (20 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 μM ZnCl2) at 23°C. Step by step injections of the 0.3–10 mM titrants (H3K9me31–21, C2HRNizp1 and mutants) solution into a cell containing a 25–200 μM PHDVC5HCHNSD1 were performed to finally reach a 2-fold and 7-fold molar excess of CH2RNizp1 and H3K9me31–21, respectively, with respect to the protein concentration. The quantity of heat absorbed or released in the process was measured. Control experiments were performed under identical conditions to determine the dilution heat of the titrant peptides into buffer and of the buffer into protein samples. The final data were analyzed using the software ORIGIN 7.0 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA).

Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics calculations

C2HRNizp1 structure calculations suggested that the Zn2+ ion was coordinated only by the thiols of C407Nizp1 and C410Nizp1 and by the Nϵ2 of H423Nizp1, we therefore verified whether water molecules could complete the Zn2+ coordination sphere using hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations (Density Functional based Tight Binding) (47). Calculations have been performed on the final structure of a MD simulation (100 ns) performed on the lowest C2HRNizp1 NMR energy structure using Amber14 (48), the Amber ff12SB force field and the SPCE water model (49). Adaptive solvent QM/MM calculations (50) were performed including in the active region the side chains of C407Nizp1, C410Nizp1, H423Nizp1, N409Nizp1 and eleven water molecules. After the equilibration phase of the QM part, a free QM/MM simulation (100 ps) was performed using Sander module (48).

Docking model

The complex model was generated using the information-driven docking software HADDOCK 2.0 (51). 10 NMR input structures for both PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 (residues S401-E429) were used. Ambiguous interactions restraints (AIRs) were generated based on NMR CSP data. We defined as active those residues showing a significant amide chemical shift displacement (defined as CSP > <CSP> + 1σ, whereby σ is the standard deviation) upon ligand binding and as passive those residues within a radius of 4 Å from the active ones. Among them, only amino acids with high solvent accessibility (relative all-atoms accessibilities > 40%) were considered (Supplementary Table S2). Naccess V2.1.1 (Hubbard, S.J. & Thornton, J.M. (1993), ‘NACCESS’, Computer Program, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University College London) was used for the solvent accessible area calculations. Unambiguous restraints were applied to maintain the Zn2+ ion coordination sphere. Calculations generated 1000, 1000, 500 structures for the rigid body docking (it0), the semi-flexible refinement (it1) and the explicit solvent refinement (water), respectively. In it0, each model was the result of five internal docking trials (with randomization of the starting orientations), whereby for each model the pose rotated by 180° around the normal to the interface was also sampled. In the it1 step, the semi-flexible regions were automatically defined. OPLS force field (52) and TIP3P water model were used. Tetra-coordinated Zn2+ ions in PHDVC5HCHNSD1 were treated according to bonded ZAFF parameters (53), whereas the Zn2+ ion in C2HRNizp1 was treated according to the aforementioned QM/MM calculations. The final 500 structures obtained after water refinement were scored according to their Haddock Score. The latter (defined as HADDOCKscore = 1.0 EvdW+0.2 Eelec+1.0 Edesolv+0.1 EAIR) is a weighted combination of van der Waals and electrostatic energy terms, represented by Lennard–Jones and Coulomb potentials, empirical desolvation term developed by Recio et al. (54) and ambiguous interaction restraint energy term, which reflects the accordance of the model to the input restraints. HADDOCK models were clustered (55) based on their interface root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.), setting the cutoff and the minimum number of models in a cluster to 4 Å and to 10, respectively. To remove any bias of the cluster size on the cluster statistics, the final overall score of each cluster was calculated on the five lowest HADDOCK scores models in that cluster (Supplementary Table S3).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

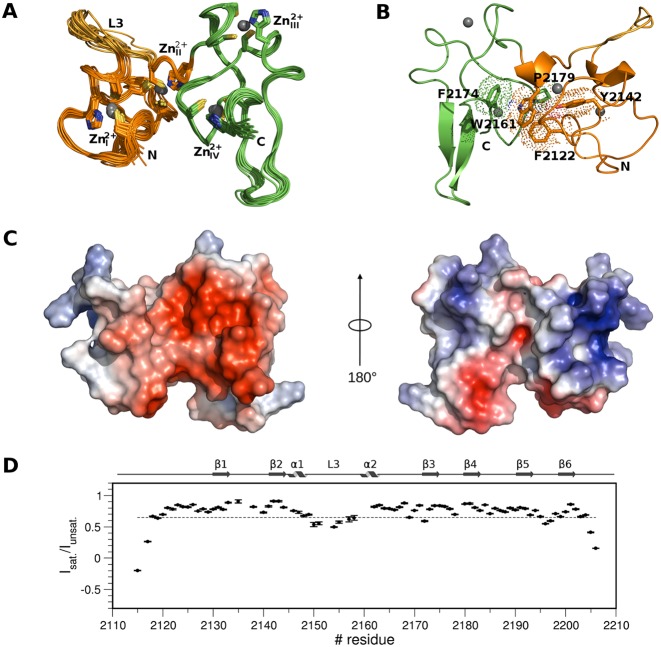

PHDVC5HCHNSD1 tandem domain forms a unique structural entity

We determined the three-dimensional solution structure of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 using multidimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy (Figure 1A, B, Table 1). As the mouse PHDVC5HCHNSD1 sequence shares 99% identity with the human one (Supplementary Figure S1), we adopted the human sequence numbering scheme to map Sotos syndrome mutants (see further). Residues E2116-Q2163NSD1 adopt the classical PHD finger fold consisting of an initial loop, relatively well defined from residues D2126NSD1 to L2130NSD1, a two-stranded antiparallel β-sheet formed by L2130-S2132NSD1 (β1) and V2141-H2143NSD1 (β2), followed by a short α-helix (A2144-L2147NSD1), and the so-called variable L3 loop (N2148-E2158NSD1) (56). A C-terminal 3–10 α-helix (P2160-H2162NSD1) links the domain to the adjacent C5HCH domain (residues C2164-D2206NSD1), whose sole elements of secondary structures consist of two short antiparallel β-sheets, β3-β4 (S2173-C2175NSD1; S2180-F2182NSD1), β5-β6 (L2191-S2194NSD1; G2198-C2202NSD1) arranged orthogonally one to each other (Figure 1A and B). The tandem domain is stabilized by four Zn2+ ions, coordinated respectively by C2121NSD1, C2124NSD1, C2146NSD1 and H2143NSD1 (Zn2+I), C2133NSD1, C2138NSD1, C2159NSD1 and H2162NSD1 (Zn2+II), C2164NSD1, C2167NSD1, C2183NSD1 and H2186NSD1 (Zn2+III), C2175NSD1, C2178NSD1, C2202NSD1 and H2205NSD1 (Zn2+IV) (Figure 1A). Metal ions binding via the imidazole rings occurs through Nδ of H2143NSD1 and H2186NSD1 and through Nϵ atoms for His2162NSD1 and H2205NSD1, as assessed from HMQC long range experiments (data not shown). Several conserved hydrophobic residues within the NSD family (F2122NSD1,Y2142NSD1, W2161NSD1, F2174NSD1, P2179NSD1) (Supplementary Figure S1A) establish direct inter-domain interactions (Figure 1B) creating a hydrophobic groove surrounded by negatively charged residues (Figure 1C). Of note, when expressed as single domains both the PHDV and the C5HCH domains are unstable in solution, as assessed respectively, by their low solubility and NMR peaks duplication (data not shown), thus supporting the notion that the two Zn2+ binding domains are intimately linked, forming an indivisible structural entity. Global and local dynamics of the tandem domain, including motions ranging from picoseconds to milliseconds time scales, were obtained analyzing 15N relaxation parameters from 79 residues that gave sufficiently resolved backbone peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum. The R2/R1 ratio for residues located in both PHDV and C5HCH is relatively uniform indicating that in solution the molecule behaves as a monomer and tumbles as a single body with a calculated correlation time of 7.96±0.41 ns (Supplementary Figure S2A). The steady-state heteronuclear {1H}–15N NOE, a sensitive indicator of internal motions on a sub-nanosecond timescale, revealed that most residues displayed values around 0.8. The N- and C-termini, the L3-loop within PHDV and the loop linking β5 and β6 showed lower values, indicating a significant mobility in the ps-ns time scale, in agreement with the paucity of inter-residue NOEs in this region (Figure 1D). The single domains are arranged in a ‘face to side’ manner, similarly to what observed in the homologue PHDVC5HCHNSD3 structure (65% sequence identity) (Supplementary Figures S1 and S3A). The fold similarity between the two NSD tandem domains is high, with a r.m.s.d. of 1.6 Å over 91 Cα atoms; major differences between the two structures are observable in the L3 loop, due to the presence of two consecutive Prolines (P1355-P1356NSD3) in PHDVC5HCHNSD3 occupied by an Arginine and a Proline in the equivalent positions in PHDVC5HCHNSD1 (R2152-P2153NSD1) (Supplementary Figure S3A). The ‘face to side’ orientation appears to be a hallmark of the NSD family, and differs from the ‘face to back’ arrangement adopted by the tandem PHD fingers of the histone acetyltransferase MOZ (monocytic leukemia Zinc-finger protein) (57,58) or of the adaptor component of BAF chromatin remodeling complex Dpf3b (59) (Supplementary Fig. S3B and C), thus defining a different structural class of PHD tandem domains.

Figure 1.

Solution structure of PHDVC5HCHNSD1. (A) Superposition of the best 15 NMR structures PHDV; the L3 loop and C5HCH are coloured in orange, gold and green, respectively. Zn2+ binding residues and Zn2+ ions are represented in sticks and spheres, respectively. (B) Cartoon representation of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 highlighting elements of secondary structure. Residues forming the domain hydrophobic core at the domains interface are shown in sticks and dotted space-filling representation. Zn2+ ions are represented in spheres. Amino acids in this and in the following Figures are numbered according to the human NSD1 sequence. (C) Electrostatic surface potential of PHDVC5HCHNSD1. The structures on the left and on the right are represented in the same orientation as in (A) and (B), respectively. (D) Backbone dynamics of PHDVC5HCHNSD1. Dotted line indicates the {1H}–15N heteronuclear NOE value threshold of 0.65. Elements of secondary structure are indicated on the top.

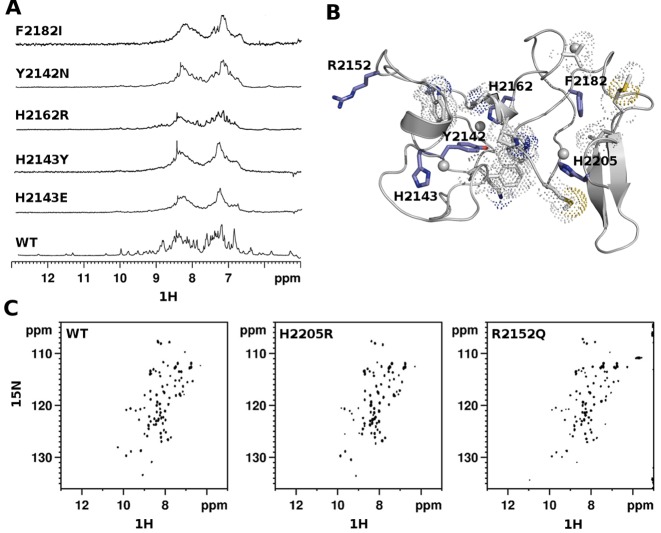

Structural analysis of Sotos syndrome point mutations

Of the 17 Sotos syndrome missense mutations targeting PHDVC5HCHNSD1, 14 involve Zn2+-coordinating residues and 3 affect amino-acids outside the metal binding site (Supplementary Table S1). As already observed in other PHD finger domains (30,31), the pathological effect of mutations involving Zn2+ coordinating Cysteines is ascribable to loss of function effects, due to domain unfolding caused by Zn2+ depletion. Conversely, the structural effect of Histidine mutations is less predictable, as they are often dispensable to preserve Zn2+ coordination and fold integrity (60) (see also further). In order to have a complete overview of the structural impact of the non-Cysteine pathological mutations we expressed and purified seven non-Cysteine Sotos mutants and compared their NMR spectra to the wild-type one (Figure 2A and B, Supplementary Figure S3E). The 1D-1H spectra of H2143ENSD1, H2143YNSD1, H2162RNSD1 were characterized by distinctive line-broadening effects, indicative of aggregation and/or unfolding, thus revealing their fundamental role in Zn2+ coordination and domain stability (Figure 2A). Unexpectedly, H2205RNSD1 mutation did not affect the domain fold as shown by the good peak dispersion of its 2D 1H–15N HSQC spectrum (Figure 2C). Conceivably, the three Zn2+ binding Cysteines are sufficient to maintain metal ion coordination, and the methylene groups of the Arginine-mutant can partially replace the hydrophobic interactions established by H2205NSD1 with M2177NSD1 (Figure 2B). Finally, among the mutants outside the Zn2+ binding sites, Y2142NNSD1 and F2182INSD1 involved two conserved aromatic residues establishing stabilizing hydrophobic interactions with F2122NSD1, K2140NSD1, W2157NSD1, P2160NSD1, W2161NSD1, V2166NSD1, M2177NSD1, P2179NSD1, M2190NSD1 and L2191NSD1) (Figure 2B). Mutations of both Y2142 NSD1 and F2182 NSD1 resulted in domain unfolding and/or aggregation, as assessed by the broad lines and reduced peak dispersion of their 1H-1D spectra (Figure 2A). Conversely, mutation of the solvent exposed R2152NSD1 into Glutamine (Figure 2B, C), did not affect the domain fold, as assessed by the remarkable similarity between the wild-type and mutant 1H–15N-HSQC spectra (Figure 2C). In the context of Sotos syndrome, fold-destroying mutants most likely result in functional inactivation of NSD1, well in keeping with NSD1 haploinsufficiency being the primary pathogenic mechanism in the syndrome (61). However, a more complex scenario at molecular level could arise from fold-preserving mutations, whose effects might not be simply ascribed to a generic loss of function event. It is conceivable that the change in electrostatic potential induced by both the H2205RNSD1 and R2152QNSD1 fold-preserving mutations results in downstream effects on the molecular complexes recruited by NSD1 and consequently on the transcriptional events regulated by these macromolecular assemblies. The functional impact of fold-preserving mutations has been already observed in other PHD finger containing proteins, such as Autoimmune regulator protein (AIRE), where PHD fingers pathological mutations acted on AIRE chromatin-associated interactome, thus reducing the activation of its target genes (31).

Figure 2.

Structural effects of Sotos syndrome mutations. (A) 1D 1H spectra (amide region) of wild-type and pathological mutants of PHDvC5HCHNSD1. (B) Cartoon representation of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 (gray). The side chains of pathological point mutations are shown in blue sticks, residues involved in hydrophobic contacts are shown in grey sticks with dotted space-filled representation. (C) 2D 1H–15N HSQC spectra (amide region) of wild-type and pathological mutants of PHDvC5HCHNSD1.

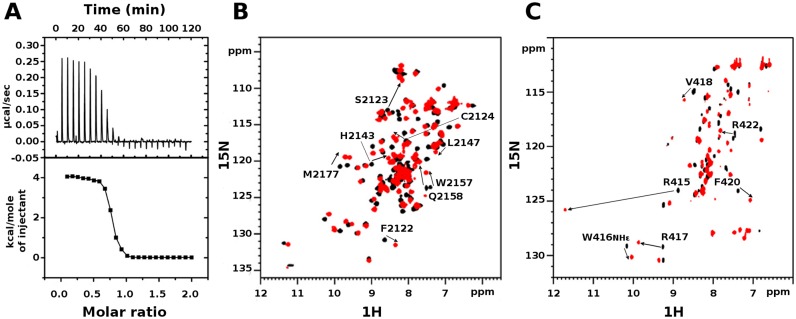

PHDVC5HCHNSD1 binds to C2HRNizp1 with low-micromolar affinity

Over the last decade PHD fingers as single modules or in combination with other chromatin binding domains have been intensively studied as histone binding recognition domains (62,63). Conversely, the possibility that PHD fingers can directly interact with non-histone proteins has been limited to only few examples, including the PHD fingers of MLL1 (28), of Pygo2 (27) and of Sp140 (64), interacting respectively with Cyp33, Bcl9 and Pin1. In line with the emerging multifaceted role of PHD fingers as structural hubs for multiple interactions, early yeast-two-hybrid screening and GST-pulldown assays, corroborated by site directed mutagenesis, have suggested a direct interaction between murine NSD1 and the nuclear repressor Nizp1 (also known as Zfp496) via the PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 domains (7,25). Prompted by this observation, we wondered whether we could confirm and thermodynamically characterize this PHD-finger/non-histone protein interaction. Indeed, evaluation of the binding through isothermal titration calorimetry indicated that a Nizp1 fragment (residues E397-K434Nizp1 as defined in (7)) containing the putative Zn2+-binding C2HRNizp1 domain binds to PHDVC5HCHNSD1 with a dissociation constant of 3.8 ± 0.7 μM in a 1:1 ratio (Figure 3A). At room temperature (T = 23°C) the reaction is endothermic (ΔH = 4.1 ± 0.1 kcal/mol) and entropy driven (TΔS = 11.4 kcal/mol) suggesting a prominent role of hydrophobic interactions in complex formation.

Figure 3.

Interaction between PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1. (A) ITC-binding curves of C2HRNizp1 to PHDVC5HCHNSD1. The upper panel shows the sequential heat pulses for domain–domain binding, and the lower panel shows the integrated data, corrected for heat of dilution and fit to a single-site-binding model using a nonlinear least-squares method (line). (B) Superposition of 1H–15N HSQC spectra of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 without (black) and with (red) C2HRNizp1. (C) Superposition of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of C2HRNizp1 without (black) and with (red) PHDVC5HCHNSD1. The peak with the down shift to 11.8 ppm upon PHDVC5HCHNSD1 addition corresponds to the backbone amide of R415Nizp1, suggesting the presence of an H-bond upon complex formation. Peaks shifting more than <CSP>+1σ are explicitly labeled.

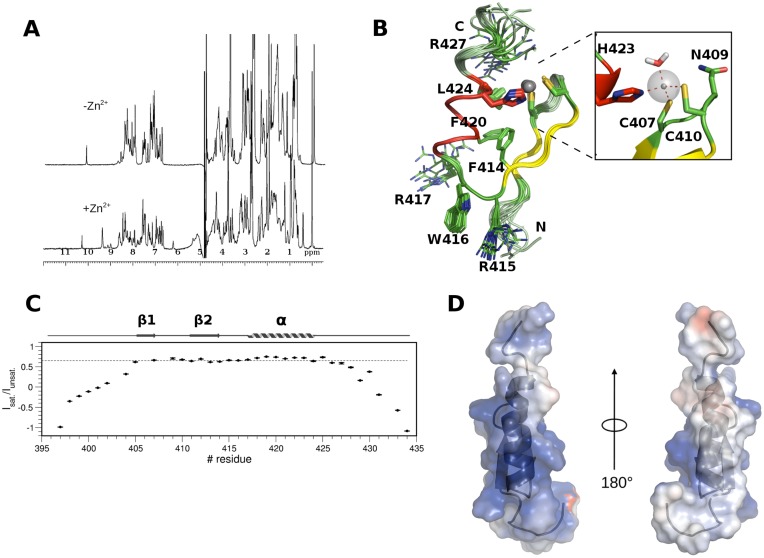

Solution structure of C2HRNizp1

To get further molecular insights into the interaction between PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 we first solved C2HRNizp1 solution structure by classical homonuclear and heteronuclear experiments (Table 2). Despite the presence of an Arginine (R427Nizp1) replacing the fourth core Histidine in this atypical Zinc-finger sequence (Supplementary Figure S1B), the domain has a Zn2+ dependent fold, as assessed by the increased chemical shift dispersion of its 1D-1H spectrum upon addition of one Zn2+ equivalent (Figure 4A). The domain adopts the typical Zinc-finger topology composed by a small two-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, encompassing residues Y405-C407Nizp1 (β1) and G411-F414Nizp (β2), followed by a short positively charged α-helix (R417-H423Nizp1) (Figure 4B). The N-terminus (E397-K403Nizp1) and the C-terminus (R425-K434Nizp1) are extremely flexible, in line with their low heteronuclear NOE values (Figure 4C). A network of hydrophobic interactions involving F414Nizp1, F420Nizp1, L424Nizp1 also contributes to domain stability (Figure 4B). Of note, W416Nizp1 is located on a solvent exposed loop (RWR-loop) and protrudes out of the domain suggesting a possible functional role for this residue (Figure 4B). Finally, C2HRNizp1 is highly positively charged with a positive patch comprising the surface of the α-helix and the RWR-loop, well suited to interact with the negatively charged surface of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 (Figure 4D). Of note, the RWR-loop appears to be well conserved along evolution, in line with its possible functional role (Supplementary Figure S1B). Preliminary structure calculations performed without including the Zn2+ ion revealed that three residues out of the C2HRNizp1 signature (C407Nizp1, C410Nizp1, H423Nizp1) are near in space, at the appropriate distance to coordinate the metal ion, whereas R427Nizp1 (Figure 4B), located on the flexible C-terminal tail is distant from these residues and is not involved in Zn2+ binding. We also excluded that N409Nizp1 side chain (Figure 4B), which was in proximity to the metal binding site, could bind Zn2+ ion completing its coordination sphere, as its mutation into Alanine did not have any impact on the domain fold, as assessed by comparison between the mutant and wild-type 1D 1H NMR spectra (Supplementary Figure S4A). Final structure calculations including distance restraints for the Zn-S− and Zn-Nϵ, did not highlight any backbone carbonyl or suitable side chain in the proximity of the metal ion that could complete its coordination. Since the three-coordinated Zn2+ ion is partially solvent exposed, water molecules can easily fill its coordination sphere, as often observed in the catalytic Zn2+-binding sites of enzymes or in other Zn2+ binding modules (60,65). Indeed, QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) calculations confirmed the presence of one water molecule completing the tetrahedral Zn2+ ion coordination sphere (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S4B).

Table 2. Summary of conformational constraints and statistics for the 15 lowest energy structures of C2HRNizp1.

| Restraints Information a,b | <SA>c |

| Total number of experimental distance restraints | 569 |

| C2HRNizp1 (intraresidual/sequential/medium/long) | 191/156/122/100 |

| Zn2+ coordination restraints | 3 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 1 |

| Dihedral angle restraints (Φ/Ψ) | 20/20 |

| Deviation from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0031 ± 0.0001 |

| Angles (°) | 0.481 ± 0.031 |

| Coordinate R.m.s. Deviation (Å)d | |

| Ordered backbone atoms (N, Cα, C’) | 0.462 ± 0.146 |

| Ordered heavy atoms | 1.034 ± 0.34 |

| Ramachandran Quality Parameters (%)e | |

| Residues in most favoured regions | 93.00% |

| Residues in allowed regions | 7.00% |

a No dihedral angle restraints in any of the structures included in the ensemble was violated by more than 5°.

b Simulated annealing, statistics refers to the ensemble of 15 structures with the lowest energy.

c No distance restraint in any of the structures included in the ensemble was violated by more then 0.5 Å.

d Root mean squared deviation between the ensemble of structures <SA> and the lowest energy structure and Ramachandran quality parameters calculated on residues Ser404–Ser426.

Figure 4.

Solution structure of C2HRNizp1. (A) 1D 1H spectrum of a synthetic peptide corresponding to C2HRNizp1 (0.2 mM) with (bottom) and without (top) one equivalent of ZnCl2. (B) Superposition of the best 15 NMR structures of C2HRNizp1, with the two β-strands, the α helix and the loops coloured in yellow, red and green, respectively. Zn2+ binding residues and the Zn2+ ions are represented in sticks and spheres, respectively. The hydrophobic core, the RWRNizp1 loop and R427Nizp1 are represented in lines. A zoom into the Zn2+ binding site of a representative structure from QM/MM calculations is shown in the inset, highlighting the presence of one water molecule completing the tetrahedral Zn2+ ion coordination sphere (highlighted by red dotted lines). H423Nizp1, C407Nizp1, N409Nizp1, C410Nizp1 and the water molecule are represented in sticks. (C) Backbone dynamics of C2HRNizp1. The dotted line indicates the {1H}–15N heteronuclear NOE value threshold of 0.65. Elements of secondary structure are indicated on the top of the figure. (D) Electrostatic surface potential of C2HRNizp1.

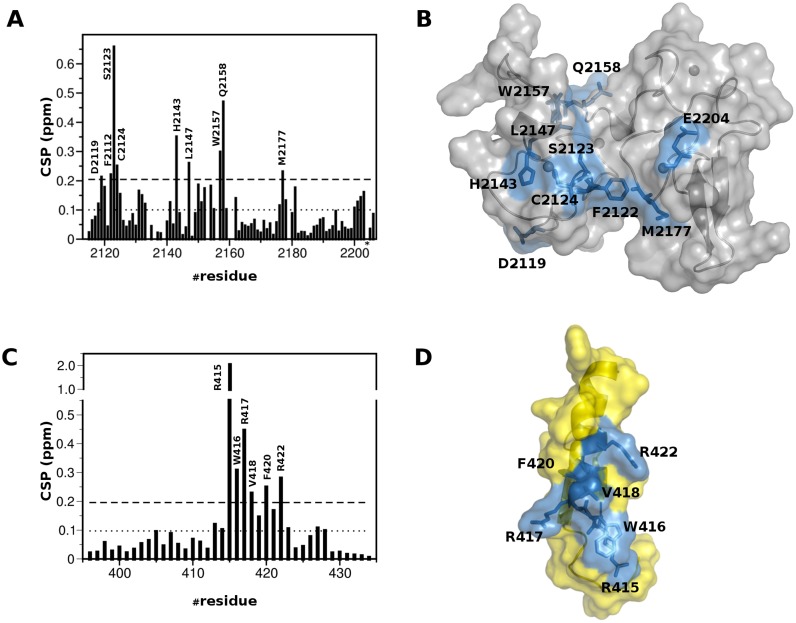

Mapping of PHDVC5HCHNSD1/C2HRNizp1 interaction surface

To map the interaction surface between PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 we performed CSP experiments titrating 15N-PHDVC5HCHNSD1 with unlabeled C2HRNizp1. The CSP method is extremely sensitive and versatile, well suited to detect both strong and weak interactions, to map binding sites and detect residues both directly interacting with the ligand and/or indirectly affected by the association. Considerable changes in the slow- to intermediate-exchange regime occurred in PHDVC5HCHNSD1 1H–15N HSQC spectrum upon addition of unlabeled C2HRNizp1 (Figure 3B). At equimolar ratio PHDVC5HCHNSD1 resonances with significant amide CSP or disappearing upon binding, clustered on the negatively charged surface of the tandem domain, mainly involving residues at the interface between PHDV and C5HCH (D2119NSD1, F2122NSD1, S2123NSD1, C2124NSD1, H2143NSD1, L2147NSD1, W2157NSD1, E2158NSD1, M2177NSD1, E2204NSD1) (Figure 5A and B). The reverse NMR titration, in which unlabelled PHDVC5HCHNSD1 was stepwise added into 15N-C2HRNizp1 (Figure 3C) indicated that the C2HRNizp1 α-helix and the solvent exposed RWR-loop were affected by the binding, as assessed by the remarkable amide chemical shifts of residues R415Nizp1, W416Nizp1, R417Nizp1, V418Nizp1, F420Nizp1, R422Nizp1 (Figure 5C and D). Relaxation measurements acquired on 15N-PHDVC5HCHNSD1 or on 15N-C2HRNizp1 in the presence of unlabelled C2HRNizp1 or PHDVC5HCHNSD1, respectively, yielded a correlation time of ∼12 ns, well in agreement with a 1:1 complex (MW ∼15 kDa) tumbling in solution as a unique structural entity (Supplementary Figure S2 A and B).

Figure 5.

Mapping of the interaction between PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1. (A) Histograms showing the averaged backbone chemical shift differences observed in PHDVC5HCHNSD11H–15N HSQC (0.2 mM) upon addition of a 2-fold excess of C2HCRNizp1. Missing bars correspond to either Prolines or amides that are not visible because of exchange with the solvent. The asterisk indicates peak disappearance (Glu2204NSD1) upon binding. The last two bars in the plot correspond to the indole amides of W2157NSD1 and W2168NSD1, respectively. (B) Cartoon and surface representation of PHDVC5HCHNSD1. Residues showing significant chemical shift perturbation are represented in sticks and coloured in blue. (C) Histograms showing the averaged backbone chemical shift differences observed in C2HCRNizp11H–15N HSQC (0.2mM) upon addition of a 2-fold excess of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 In all the histograms, the dotted line represents <CSP>, the dashed line represents <CSP> + 1σ value, where σ corresponds to standard deviation. (D) Cartoon and surface representation of C2HRNizp1 (yellow). Residues showing significant chemical shift perturbation are represented in sticks and are coloured in blue.

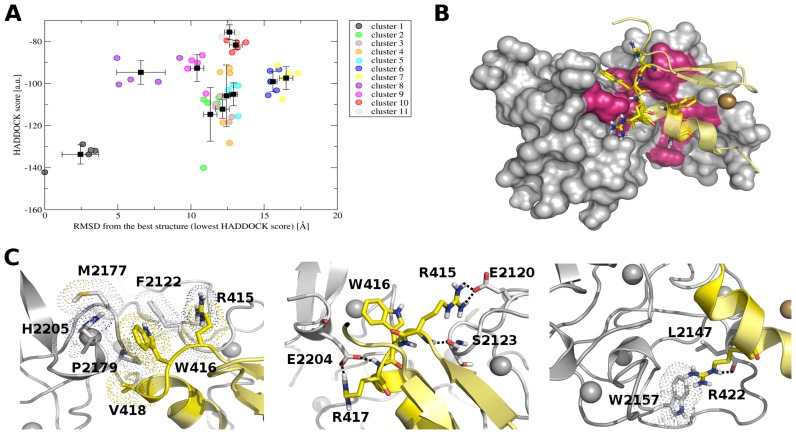

Three-dimensional model of PHDVC5HCHNSD1/C2HRNizp1 complex

Although most of the backbone resonances assignment of bound PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 was accomplished, due to unfavourable dynamic regime and to sample precipitation and degradation at concentrations beyond 0.3 mM, it was not possible to detect intermolecular NOEs to determine the complex structure using the standard NOE-based approach. Thus, we took advantage of the well-established HADDOCK 2.0 software (51) to obtain a structural model of the complex, exploiting experimental CSP data, as described in Materials and Methods. Docking models were clustered based on the interface r.m.s.d. resulting in 11 clusters (Figure 6A, Supplementary Table S2). Importantly, in all the clusters C2HRNizp1 docks inside PHDVC5HCHNSD1 placing its α helix in the interdomain groove formed by PHDV and C5HCH (Figure 6B). In particular in Cluster 1, showing the best HADDOCK score (Figure 6A, Supplementary Table S2), C2HRNizp1 interacts with PHDVC5HCHNSD1 inserting its W416Nizp1 side chain into the hydrophobic pocket generated by H2205NSD1, F2122NSD1, M2177NSD1, P2179NSD1, R415Nizp1 and V418Nizp1 (Figure 6C-left). A set of polar contacts involving the Arginines of the RWR signature seems to contribute to the binding: the guanidinium group of R417Nizp1 forms a salt-bridge with the carboxylate of E2204NSD1; moreover R415Nizp1 establishes electrostatic interactions with the carboxylate of E2120NSD1 through its guanidinium group and forms through its amide proton a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl of S2123NSD1 (Figure 6C, middle). Finally, R422Nizp1 points toward the interdomain groove, interacting with L2147NSD1 and W2157NSD1 (Figure 6C right). All the residues establishing favourable intermolecular interactions were consistent with the observed chemical shift perturbations. In an effort to assess the validity of our HADDOCK model we made a series of single point mutations around the binding interface of both PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 to investigate their effect in NMR and/or calorimetric titrations (Table 3). In particular, mutation of the exposed W416Nizp1 into Alanine had a very strong impact, with little or virtually no detectable binding in NMR titrations, implying almost complete abrogation of the interaction (Supplementary Figure S5B, Table 3). This result strongly supports the role of hydrophobic interaction in this binding process, in agreement with the entropically driven reaction, most likely deriving from the desolvation of the intermolecular binding interface. Both R417Nizp1 and E2204NSD1 mutations into Alanine resulted in one order of magnitude reduction in binding affinity and a reduction of the average chemical shifts displacements (Table 3) corroborating the presence of a salt-bridge between these two residues (Figure 6C, left). Mutation of R415Nizp1 did not have a relevant impact in binding, suggesting that the major interaction with PHDVC5HCHNSD1 occurs via a hydrogen bond between its amide and the carbonyl of S2123NSD1, in line with the extreme down-shift of S2123NSD1 amide proton resonance upon binding (Figures 3C and 6C, middle). R422ANizp1, with only a 2-fold increase in the Kd, had a minor impact in binding (Table 3), implying a secondary role for this residue in substrate recognition. Unfortunately, we could not assess the role of E2120NSD1, F2122NSD1 and S2123NSD1 in binding as their mutations into Alanine caused low expression yields and partial PHDVC5HCHNSD1 unfolding. Mutation of the R427Nizp1 within the C2HR signature did not influence binding, in agreement with both the model and the chemical shift mapping which did not highlight any relevant role of this residue in the binding. We also verified the impact of fold-preserving Sotos syndrome point mutations in the binding to C2HRNizp1. As expected, R2152QNSD1 mutation, located on the opposite surface with respect to C2HRNizp1 binding site, did not affect complex formation (Table 3). Conversely, H2205RNSD1 mutation, located near the binding site identified by CSP, reduced the binding of almost one order of magnitude, probably because of repulsive interactions with R417Nizp1 and of the loss of stabilizing hydrophobic interactions between H2205NSD1 and W416Nizp1 (Figure 6C, left). Based on these findings and on the repressive role attributed to Nizp1 and NSD1 interaction (7), it is conceivable that Sotos syndrome mutations targeting PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and hampering interaction with Nizp1 might have an impact on the repression of growth-promoting genes, eventually resulting in overgrowth disease.

Figure 6.

HADDOCK model of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1. (A) HADDOCK score versus r.m.s.d. from the lowest energy complex structure in terms of HADDOCK score (a.u.). Circles correspond to the best five structures of each cluster, black squares correspond to the cluster averages with the standard deviation indicated by bars. (B) Representative pose of the best docking model in terms of HADDOCK score. PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 are shown as surface and cartoon, respectively. Active residues are shown in hot pink and yellow sticks in PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1, respectively. (C) Details of the relevant interactions between PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1. Hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between RWRNizp1 loop and PHDvC5HCHNSD1 are shown on the left and central panels, respectively. Interactions of R422Nizp1 are shown on the right panel. Hydrophobic interactions are highlighted with dotted space-filling representation and polar interactions with dotted lines. Zn2+ ions are shown as grey (PHDVC5HCHNSD1) and gold spheres (C2HRNizp1)

Table 3. Thermodynamic parameters, stoichiometry (n) and dissociation constants (Kd) between PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 wild type (WT) and mutants measured by ITC (T = 22°C).

| PHDvC5HCHNSD1 | C2HRNizp1 | ΔH (kcal/mol) | -TΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | n | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | WT | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 11.4± 0.1 | -7.3 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.7 |

| R2152Q | WT | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 10.7 ± 0.1 | -7.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.6 |

| E2204A | WT | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | -5.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 45.2 ± 6.9 |

| H2205R | WT | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 27.2 ± 5.3 |

| WT | R415A | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 9.3 ± 0.1 | -7.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.4 |

| WT | W416A | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| WT | R417A | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 36.0 ± 6.0 |

| WT | R422A | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.2 |

| WT | R427A | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | -7.3 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.3 |

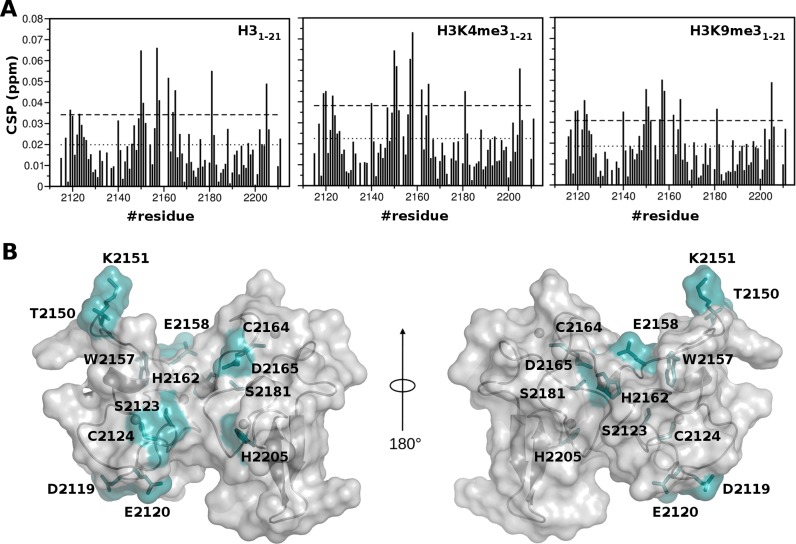

Biophysical assessment of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 interaction with histone H3 N-terminal tail peptides

Until now biochemical assays aiming at the in vitro assessment of the effective histone binding ability of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 were not conclusive. On one hand recent pulldown assays of GST-PHDVC5HCHNSD1 with unfractionated calf thymus histones or with biotinylated histone H3 peptides did not provide evidence of histone binding (26). On the other hand histone binding assays using MODified Histone Peptide Array TM (Activ Motif) (Supplementary Figure S6A,B) were in line with previous pull-down assays of GST-PHDVC5HCHNSD1 with modified biotinylated peptides (21 aminoacids long) (25), suggesting an interaction preference for H3K4me3 and H3K9me3. Because of the qualitative nature of biochemical binding assays, that are often prone both to false positive and negative results (66–68), we biophysically verified this putative interaction using NMR CSP. At variance to what observed in titrations with C2HRNizp1, addition of up to 12 molar excess of unmodified or modified histone peptides (H31–21, H3K4me31–21 and H3K9me31–21) induced in PHDVC5HCHNSD1 1H–15N HSQC spectrum very small changes in the fast exchange regime, suggestive of extremely weak interactions (with an average CSP value <CSP> of ∼0.02 ppm) (Figure 7A, Supplementary Figure S6C). As the binding curves did not reach saturation, it was not possible to reliably fit the binding curves obtained during the individual titrations, implying affinities in the high mM range, i.e. orders of magnitude higher with respect to the micromolar affinity usually observed in PHD-histone tail interactions (69,70). Accordingly, isothermal titration calorimetry experiments did not develop sufficient heat to allow Kd determination (data not shown). Notably, in all the titrations, irrespectively of the peptides modification status, residues exhibiting significant amide chemical shift (CSP > <CSP> + 1σ) did not involve the classical histone binding surface, composed by the N-terminus of the PHD finger, the first β-strand, and the conserved PXGXW binding pocket. Peaks significantly shifting upon H3 peptides addition belonged to residues located on both PHDV and C5HCH (D2119NSD1, E2120NSD1, S2123NSD1, C2124NSD1, T2150NSD1, K2151NSD1, W2157NSD1, E2158NSD1, H2162NSD1, C2164NSD1, D2165NSD1, S2181NSD1, H2205NSD1), mainly, at the interface between PHDV and C5HCH, on the negatively charged surface of the tandem domain (Figures 1C and 7B). Of note, these residues did not form a continuous interaction surface when mapped on the surface of the tandem domain (Figure 7B). Intriguingly, NMR titrations performed reducing or increasing the number of positively charged residues using shorter (H31–10) or longer peptides (H31–36), did not change the chemical shift differences profiles, but rather resulted in smaller and higher chemical shifts displacements, respectively (Supplementary Figure S6D). Taken together, these observations strongly support the non-specific electrostatic nature of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 histone H3 tail interaction. Indeed, titration of the domain with up to 300 mM of Lysine induced amide chemical shifts in the same region (Supplementary Figure S6D). Overall, in contrast to what observed in previous binding assays with biotinylated histone peptides (25), but in agreement with recent GST-pulldown experiments with unfractionated calf thymus histones and biotinylated histone peptides (26), our biophysical data exclude a role of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 in decoding methylated/unmethylated H3K4 and H3K9 epigenetic marks. We cannot rule out that, despite the extensive modification coverage guaranteed by the peptides arrays, PHDVC5HCHNSD1 has an as-of-yet unidentified histone modification(s) specificity. It is conceivable that the specific recruitment of full-length NSD1 to chromatin might be mediated by the combinatorial interactions of the other chromatin readers (four PHD fingers and two PWWP) present in the full-length protein. Herein, the acidic surface of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 might work as an electrostatic platform reinforcing the interaction with the basic histone tails. Indeed, it is not unusual that isolated readers displaying in vitro weak or non-specific interactions with their histone peptide target, in the context of the full length protein reach physiologically relevant binding affinities range, thanks to multivalent interactions and/or contacts using scaffolding domains that bridge their host proteins with other subunits of the chromatin bound complex (62). As the C2HRNizp1 binding site involves PHDVC5HCHNSD1 interdomain space, we wondered whether the weak interaction with the histone H3 N-terminal tail could compete with complex formation. The 1H–15N HSQC spectra of both 15N-PHDVC5HCHNSD1/C2HRNizp1, and of 15N-C2HRNizp1/PHDVC5HCHNSD1 (1:1) did not show any substantial change upon addition of an excess of H31–21 peptide (1:12), excluding a competing influence of the histone H3 tail on PHDVC5HCHNSD1/C2HRNizp1 interaction (Supplementary Figure S5A).

Figure 7.

Mapping of the interaction with histone H3 amino-terminal peptides. (A) Histograms showing the averaged backbone chemical shift perturbations (CSP) observed in 1H–15N HSQC of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 (0.2 mM) upon addition of a twelve-fold excess of H31–21, H3K4me31–21, H3K9me31–21. The last two bars in the plot correspond to the indole amides of W2157NSD1 and W2168NSD1, respectively. The dotted line represents <CSP>, the dashed line represents <CSP> + 1σ, where σ corresponds to standard deviation. Missing bars correspond to either Prolines or amides that are not visible because of exchange with the solvent. (B) Surface and cartoon representation of PHDVC5HCHNSD1. Residues showing significant chemical shift perturbation (CSP > <CSP>+1σ) are represented in cyan.

Functional divergence of the PHDVC5HCH domain within the NSD family

Despite the high sequence similarity shared by the PHDVC5HCH domain within the NSD family (PHDVC5HCHNSD1 shares 61% and 64% identity with PHDVC5HCHNSD2 and PHDVC5HCHNSD3, respectively) (Supplementary Figure S1A), they appear to have evolved to exert different functions. As a matter of fact, PHDVC5HCHNSD1 does not function as classical epigenetic reader, whereas PHDVC5HCHNSD2 and PHDVC5HCHNSD3 preferentially recognize H3K4me0 (demonstrated only biochemically) and H3K9me3 marks, respectively (26). Based on sequence comparison and on the available structural knowledge (this study and the 3D structure of the PHDVC5HCHNSD3/H3K9me3 complex (26)), we hypothesized that PHDVC5HCHNSD1 inability to efficiently recognize the positively charged histone H3 tail could be ascribable to electrostatic repulsions, generated by two basic residues (R2117NSD1, K2134NSD1) on the canonical histone interaction surface (Supplementary Figures S1A, S3D). Notably, the equivalent positions in NSD2 and NSD3 are occupied by a neutral aminoacid and by an acidic residue forming a salt-bridge with H3R2, as highlighted by the PHDVC5HCHNSD3/H3K9me3 crystallographic structure (Supplementary Figure S3D). However, simultaneous mutations of these basic residues (R2117ANSD1, K2134DNSD1) aiming at converting PHDVC5HCHNSD1 into a classical histone H3 reader, failed to induce the expected functional twist (Supplementary Figure S6E). Collectively, these results suggest that a more complex combination of amino-acids substitutions, possibly related to yet unidentified conformational and dynamic effects might dictate the different histone recognition propensities within the NSD family. Following the same line, PHDVC5HCH domain functional divergence seems also to reflect into different C2HRNizp1 binding abilities attributed to the three NSD proteins. In fact yeast two hybrid screenings on both C5HCHNSD2 and C5HCHNSD3 (71) along with GST-pulldown assays on PHDVC5HCHNSD3 (26) did not support their direct interaction with C2HRNizp1. Conceivably, also in this case a combination of dynamical effects and of minor sequence variations targeting the interaction surface might account for possible differences in C2HRNizp1 binding specificity within the NSD family. Future structural, dynamical and biophysical studies i. investigating the effective binding ability of the other NSD members to C2HRNizp1 and ii. verifying the putative histone H3 interaction with PHDVC5HCHNSD2 are warranted to complete our picture on the structure-function relationship within the PHDVC5HCH-NSD family.

Concluding remarks

In the last years, PHD fingers, alone or in tandem with other chromatin binding domains, have emerged as multifaceted interaction platforms, whose functions go far beyond the perceiving of the epigenetic landscape (62,63). As a matter of fact PHD fingers have been shown to work often as scaffolding domains bridging their host proteins with other subunits of bigger macromolecular complexes (62,63,72). Herein, PHDVC5HCHNSD1 seems to represent a paradigmatic example for the PHD domain functional versatility: on one hand it has been proposed to decode the methylation status of histone H3K4 and H3K9 (25), on the other hand it has been shown to mediate the recruitment of NSD1 to reinforce Nizp1 transcriptional repressor activity via its direct binding to C2HRNizp1 Zinc-finger domain (25,29,73). Notably, structural and biophysical studies proving all these interactions and providing molecular details on them were lacking. Here, we have shown that the tandem domain PHDVC5HCHNSD1 forms an indivisible structural entity that interacts only very weakly with histone H3 N-terminal tail peptides. The binding occurs via non-specific electrostatic forces, irrespectively of histone H3 methylation and involves a distinct surface with respect to the classical histone H3 tail binding groove. While the role of PHDVC5HCHNSD1 as classical epigenetic reader is highly questionable, ITC and NMR CSP experiments clearly demonstrate a finger-finger micromolar interaction between C2HRNizp1 and PHDVC5HCHNSD1. Via a data driven docking model, supported by site-directed mutagenesis, we have provided first molecular insights into the recruitment of the co-repressor NSD1 to the repressor Nizp1 via PHDVC5HCHNSD1 and a solvent exposed RWR motif of C2HRNizp1. In particular, the RWR loop of Nizp1 accommodate into the PHDVC5HCHNSD1 interdomain groove establishing hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. Interestingly, both C5HCHNSD1 and C2HRNizp1 domains have been acquired late in evolution (7) and their high conservation in vertebrates support an evolutionary preservation of this protein-protein interaction (Supplementary Figure S1). Recruitment of co-repressors through short sequence motifs is a recurrent theme in transcriptional repression, as observed for example in the engagement of Groucho corepressor via the WPRW motif of Drosophila transcriptional repressors Dorsal and Hairy (74). The prominent functional role exerted by the RWRNizp1 signature within the C2HRNizp1 domain strengthens also the notion that this atypical Zinc-finger motif is more than just a degenerate evolutionary vestige of the classical Zinc-finger C2H2 motif (7). This is in keeping with previous studies showing that Nizp1 transcriptional repressor activity depends on C2HR domain integrity, as fold destroying mutations abolished its binding to NSD1, thus reducing transcriptional repression (7). Importantly, in the Sotos syndrome context we have shown that the fold preserving mutation H2205RNSD1 also diminishes the interaction with C2HRNizp1 supporting a mechanistic scenario in which impairment of the repressive NSD1/Nizp1 complex might alter the physiological down-regulation of growth-promoting genes, thus resulting in the overgrowth phenotype, typical of Sotos syndrome. In this context, it is conceivable that other nuclear proteins besides Nizp1 bind to NSD1, whereby the PHD finger domains, in line with their functional versatility, might mediate additional protein interactions. Future studies dedicated to NSD1/Nizp1 dependent transcriptome and interactome in normal and pathological conditions will be instrumental in understanding the patho-physiological role of NSD1/Nizp1 interaction and in devising new strategies for successful treatments in overgrowth diseases.

ACCESSION NUMBERS. DB accession codes: 2naa; 2nab BioMagResBank 25933; 25934.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the CERM Infrastructure (Florence) for access to NMR instrumentation. D.S. conducted this study as partial fulfillment of his PhD in Molecular Medicine, Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology, Vita e Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, Italy.

Footnotes

Present address: Dimitrios Spiliotopoulos, Dimitrios Spiliotopoulos, Department of Biochemistry, University of Zürich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zürich, Switzerland.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Italian Ministry for Health [RF-2013–02354880 to G.M and G.T.]; Italian Association Cancer Research [AIRC-13149 to G.M.]; Fondazione Telethon [ TCP99035 to G.M.]; Fondazione Veronesi [to F.M.G.]; Marie Curie Co-funding of Regional, National and International Programmes [PCOFUND-GA-2010-267264 INVEST to M.A.C.R.]; Fondazione Cariplo [2009-3577 to M.G.]. Funding for open access charge: Italian Ministry for Health [RF-2013-02354880] or Italian Association Cancer Research [AIRC-13149].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wagner E.J., Carpenter P.B. Understanding the language of Lys36 methylation at histone H3. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:115–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vougiouklakis T., Hamamoto R., Nakamura Y., Saloura V. The NSD family of protein methyltransferases in human cancer. Epigenomics. 2015;7:863–874. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morishita M., di Luccio E. Cancers and the NSD family of histone lysine methyltransferases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1816:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurotaki N., Harada N., Yoshiura K., Sugano S., Niikawa N., Matsumoto N. Molecular characterization of NSD1, a human homologue of the mouse Nsd1 gene. Gene. 2001;279:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00750-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang N., vom Baur E., Garnier J.M., Lerouge T., Vonesch J.L., Lutz Y., Chambon P., Losson R. Two distinct nuclear receptor interaction domains in NSD1, a novel SET protein that exhibits characteristics of both corepressors and coactivators. EMBO J. 1998;17:3398–3412. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rayasam G.V., Wendling O., Angrand P.O., Mark M., Niederreither K., Song L., Lerouge T., Hager G.L., Chambon P., Losson R. NSD1 is essential for early post-implantation development and has a catalytically active SET domain. EMBO J. 2003;22:3153–3163. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen A.L., Jorgensen P., Lerouge T., Cervino M., Chambon P., Losson R. Nizp1, a novel multitype zinc finger protein that interacts with the NSD1 histone lysine methyltransferase through a unique C2HR motif. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:5184–5196. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5184-5196.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berdasco M., Ropero S., Setien F., Fraga M.F., Lapunzina P., Losson R., Alaminos M., Cheung N.K., Rahman N., Esteller M. Epigenetic inactivation of the sotos overgrowth syndrome gene histone methyltransferase NSD1 in human neuroblastoma and glioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:21830–21835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906831106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucio-Eterovic A.K., Singh M.M., Gardner J.E., Veerappan C.S., Rice J.C., Carpenter P.B. Role for the nuclear receptor-binding SET domain protein 1 (NSD1) methyltransferase in coordinating lysine 36 methylation at histone 3 with RNA polymerase II function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:16952–16957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002653107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H., Pesavento J.J., Starnes T.W., Cryderman D.E., Wallrath L.L., Kelleher N.L., Mizzen C.A. Preferential dimethylation of histone H4 lysine 20 by Suv4–20. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:12085–12092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707974200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morishita M., Mevius D., di Luccio E. In vitro histone lysine methylation by NSD1, NSD2/MMSET/WHSC1 and NSD3/WHSC1L. BMC Struct. Biol. 2014;14:25. doi: 10.1186/s12900-014-0025-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morishita M., di Luccio E. Structural insights into the regulation and the recognition of histone marks by the SET domain of NSD1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;412:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiao Q., Li Y., Chen Z., Wang M., Reinberg D., Xu R.M. The structure of NSD1 reveals an autoregulatory mechanism underlying histone H3K36 methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:8361–8368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaju R.J., Fidler C., Haas O.A., Strickson A.J., Watkins F., Clark K., Cross N.C., Cheng J.F., Aplan P.D., Kearney L., et al. A novel gene, NSD1, is fused to NUP98 in the t(5;11)(q35;p15.5) in de novo childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;98:1264–1267. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollink I.H., van den Heuvel-Eibrink M.M., Arentsen-Peters S.T., Pratcorona M., Abbas S., Kuipers J.E., van Galen J.F., Beverloo H.B., Sonneveld E., Kaspers G.J., et al. NUP98/NSD1 characterizes a novel poor prognostic group in acute myeloid leukemia with a distinct HOX gene expression pattern. Blood. 2011;118:3645–3656. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-346643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thol F., Kolking B., Hollink I.H., Damm F., van den Heuvel-Eibrink M.M., Michel Zwaan C., Bug G., Ottmann O., Wagner K., Morgan M., et al. Analysis of NUP98/NSD1 translocations in adult AML and MDS patients. Leukemia. 2013;27:750–754. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurotaki N., Harada N., Yoshiura K., Sugano S., Niikawa N., Matsumoto N. Molecular characterization of NSD1, a human homologue of the mouse Nsd1 gene. Gene. 2001;279:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00750-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurotaki N., Imaizumi K., Harada N., Masuno M., Kondoh T., Nagai T., Ohashi H., Naritomi K., Tsukahara M., Makita Y., et al. Haploinsufficiency of NSD1 causes sotos syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:365–366. doi: 10.1038/ng863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagai T., Matsumoto N., Kurotaki N., Harada N., Niikawa N., Ogata T., Imaizumi K., Kurosawa K., Kondoh T., Ohashi H., et al. Sotos syndrome and haploinsufficiency of NSD1: Clinical features of intragenic mutations and submicroscopic deletions. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:285–289. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.4.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douglas J., Hanks S., Temple I.K., Davies S., Murray A., Upadhyaya M., Tomkins S., Hughes H.E., Cole T.R., Rahman N. NSD1 mutations are the major cause of sotos syndrome and occur in some cases of weaver syndrome but are rare in other overgrowth phenotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:132–143. doi: 10.1086/345647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatton-Brown K., Rahman N. The NSD1 and EZH2 overgrowth genes, similarities and differences. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 2013;163:86–91. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G.G., Cai L., Pasillas M.P., Kamps M.P. NUP98-NSD1 links H3K36 methylation to hox-A gene activation and leukaemogenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:804–812. doi: 10.1038/ncb1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez R., Zhou M.M. The PHD finger: A versatile epigenome reader. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yap K.L., Zhou M.M. Keeping it in the family: Diverse histone recognition by conserved structural folds. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;45:488–505. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.512001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasillas M.P., Shah M., Kamps M.P. NSD1 PHD domains bind methylated H3K4 and H3K9 using interactions disrupted by point mutations in human sotos syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32:292–298. doi: 10.1002/humu.21424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He C., Li F., Zhang J., Wu J., Shi Y. The methyltransferase NSD3 has chromatin-binding motifs, PHD5-C5HCH, that are distinct from other NSD (nuclear receptor SET domain) family members in their histone H3 recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:4692–4703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.426148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiedler M., Sanchez-Barrena M.J., Nekrasov M., Mieszczanek J., Rybin V., Muller J., Evans P., Bienz M. Decoding of methylated histone H3 tail by the pygo-BCL9 wnt signaling complex. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z., Song J., Milne T.A., Wang G.G., Li H., Allis C.D., Patel D.J. Pro isomerization in MLL1 PHD3-bromo cassette connects H3K4me readout to CyP33 and HDAC-mediated repression. Cell. 2010;141:1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Losson R., Nielsen A.L. The NIZP1 KRAB and C2HR domains cross-talk for transcriptional regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1799:463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bottomley M.J., Stier G., Pennacchini D., Legube G., Simon B., Akhtar A., Sattler M., Musco G. NMR structure of the first PHD finger of autoimmune regulator protein (AIRE1). insights into autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11505–11512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaetani M., Matafora V., Saare M., Spiliotopoulos D., Mollica L., Quilici G., Chignola F., Mannella V., Zucchelli C., Peterson P., et al. AIRE-PHD fingers are structural hubs to maintain the integrity of chromatin-associated interactome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11756–11768. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G.W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vranken W.F., Boucher W., Stevens T.J., Fogh R.H., Pajon A., Llinas M., Ulrich E.L., Markley J.L., Ionides J., Laue E.D. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: Development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sattler M., Schleucher J., Griesinger C. Heteronuclear multidimensional NMR experiments for the structure determination of proteins in solution employing pulsed field gradients. Prog. NMR Spectroscopy. 1999;34:94–158. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelton J.G., Torchia D.A., Meadow N.D., Roseman S. Tautomeric states of the active-site histidines of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated IIIGlc, a signal-transducing protein from escherichia coli, using two-dimensional heteronuclear NMR techniques. Protein Sci. 1993;2:543–558. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen Y., Bax A. Protein structural information derived from NMR chemical shift with the neural network program TALOS-N. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1260:17–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2239-0_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sass H.J., Musco G., Stahl S.J., Wingfield P.T., Grzesiek S. An easy way to include weak alignment constraints into NMR structure calculations. J. Biomol. NMR. 2001;21:275–280. doi: 10.1023/a:1012998006281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farrow N.A., Muhandiram R., Singer A.U., Pascal S.M., Kay C.M., Gish G., Shoelson S.E., Pawson T., Forman-Kay J.D., Kay L.E. Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yip G.N., Zuiderweg E.R. Improvement of duty-cycle heating compensation in NMR spin relaxation experiments. J. Magn. Reson. 2005;176:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson B.A. Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;278:313–352. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barbato G., Ikura M., Kay L.E., Pastor R.W., Bax A. Backbone dynamics of calmodulin studied by 15N relaxation using inverse detected two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy: The central helix is flexible. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5269–5278. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rieping W., Habeck M., Bardiaux B., Bernard A., Malliavin T.E., Nilges M. ARIA2: Automated NOE assignment and data integration in NMR structure calculation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:381–382. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laskowski R.A., Rullmannn J.A., MacArthur M.W., Kaptein R., Thornton J.M. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: Programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doreleijers J.F., Sousa da Silva A.W., Krieger E., Nabuurs S.B., Spronk C.A., Stevens T.J., Vranken W.F., Vriend G., Vuister G.W. CING: An integrated residue-based structure validation program suite. J. Biomol. NMR. 2012;54:267–283. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9669-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker N.A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M.J., McCammon J.A. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grzesiek S., Stahl S.J., Wingfield P.T., Bax A. The CD4 determinant for downregulation by HIV-1 nef directly binds to nef. mapping of the nef binding surface by NMR. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10256–10261. doi: 10.1021/bi9611164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moreira N.H., Dolgonos G., Aradi B., da Rosa A.L., Frauenheim T. Toward an accurate density-functional tight-binding description of zinc-containing compounds. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:605–614. doi: 10.1021/ct800455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Case D.A., Berryman J.T., Betz R.M., Cerutti D.S., Cheatham T.E. III, Darden T.A., Duke R.E., Giese T.J., Gohlke H., Goetz A.W. Amber 2015. University of California, San Francisco. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kusalik P.G., Svishchev I.M. The spatial structure in liquid water. Science. 1994;265:1219–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.265.5176.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bulo R.E., Ensing B., Sikkema J., Visscher L. Toward a practical method for adaptive QM/MM simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:2212–2221. doi: 10.1021/ct900148e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Vries S.J., van Dijk A.D., Krzeminski M., van Dijk M., Thureau A., Hsu V., Wassenaar T., Bonvin A.M. HADDOCK versus HADDOCK: New features and performance of HADDOCK2.0 on the CAPRI targets. Proteins. 2007;69:726–733. doi: 10.1002/prot.21723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaminski GA., Friesner RA., Tirado-Rives J., Jorgensen W.L. Evaluation and reparametrization of the OPLS-AA force field for proteins via comparison with accurate quantum chemical calculations on peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:674. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peters M.B., Yang Y., Wang B., Fusti-Molnar L., Weaver M.N., Merz K.M., Jr Structural survey of zinc containing proteins and the development of the zinc AMBER force field (ZAFF) J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:2935–2947. doi: 10.1021/ct1002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernandez-Recio J., Totrov M., Abagyan R. Identification of protein-protein interaction sites from docking energy landscapes. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:843–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daura X., Antes I., van Gunsteren W.F., Thiel W., Mark A.E. The effect of motional averaging on the calculation of NMR-derived structural properties. Proteins. 1999;36:542–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwan A.H., Gell D.A., Verger A., Crossley M., Matthews J.M., Mackay J.P. Engineering a protein scaffold from a PHD finger. Structure (Camb) 2003;11:803–813. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiu Y., Liu L., Zhao C., Han C., Li F., Zhang J., Wang Y., Li G., Mei Y., Wu M., et al. Combinatorial readout of unmodified H3R2 and acetylated H3K14 by the tandem PHD finger of MOZ reveals a regulatory mechanism for HOXA9 transcription. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1376–1391. doi: 10.1101/gad.188359.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dreveny I., Deeves S.E., Fulton J., Yue B., Messmer M., Bhattacharya A., Collins H.M., Heery D.M. The double PHD finger domain of MOZ/MYST3 induces alpha-helical structure of the histone H3 tail to facilitate acetylation and methylation sampling and modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:822–835. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng L., Zhang Q., Li S., Plotnikov A.N., Walsh M.J., Zhou M.M. Mechanism and regulation of acetylated histone binding by the tandem PHD finger of DPF3b. Nature. 2010;466:258–262. doi: 10.1038/nature09139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cordier F., Grubisha O., Traincard F., Veron M., Delepierre M., Agou F. The zinc finger of NEMO is a functional ubiquitin-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:2902–2907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kurotaki N., Imaizumi K., Harada N., Masuno M., Kondoh T., Nagai T., Ohashi H., Naritomi K., Tsukahara M., Makita Y., et al. Haploinsufficiency of NSD1 causes sotos syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:365–366. doi: 10.1038/ng863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Musselman C.A., Lalonde M.E., Cote J., Kutateladze T.G. Perceiving the epigenetic landscape through histone readers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:1218–1227. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ali M., Hom R.A., Blakeslee W., Ikenouye L., Kutateladze T.G. Diverse functions of PHD fingers of the MLL/KMT2 subfamily. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1843:366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]