Abstract

Background

Psychological therapies have been developed for parents of children and adolescents with a chronic illness. Such therapies include interventions directed at the parent only or at parent and child/adolescent, and are designed to improve parent, child, and family outcomes. This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review published in Issue 8, 2012, (Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness).

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of psychological therapies that include parents of children and adolescents with chronic illnesses including painful conditions, cancer, diabetes mellitus, asthma, traumatic brain injury (TBI), inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), skin diseases, or gynaecological disorders. We also aimed to evaluate the adverse events related to implementation of psychological therapies for this population. Secondly, we aimed to evaluate the risk of bias of included studies and the quality of outcomes using the GRADE assessment.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of psychological interventions that included parents of children and adolescents with a chronic illness. Databases were searched to July 2014.

Selection criteria

Included studies were RCTs of psychological interventions that delivered treatment to parents of children and adolescents with a chronic illness compared to an active control, waiting list, or treatment as usual control group.

Data collection and analysis

Study characteristics and outcomes were extracted from included studies. We analysed data using two categories. First, we analysed data by each individual medical condition collapsing across all treatment classes at two time points. Second, we analysed data by each individual treatment class; cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), family therapy (FT), problem solving therapy (PST) and multisystemic therapy (MST) collapsing across all medical conditions. For both sets of analyses we looked immediately post-treatment and at the first available follow-up. We assessed treatment effectiveness for two primary outcomes: parent behaviour and parent mental health. Five secondary outcomes were extracted; child behaviour/disability, child mental health, child symptoms, family functioning, and adverse events. Risk of bias and quality of evidence were assessed.

Main results

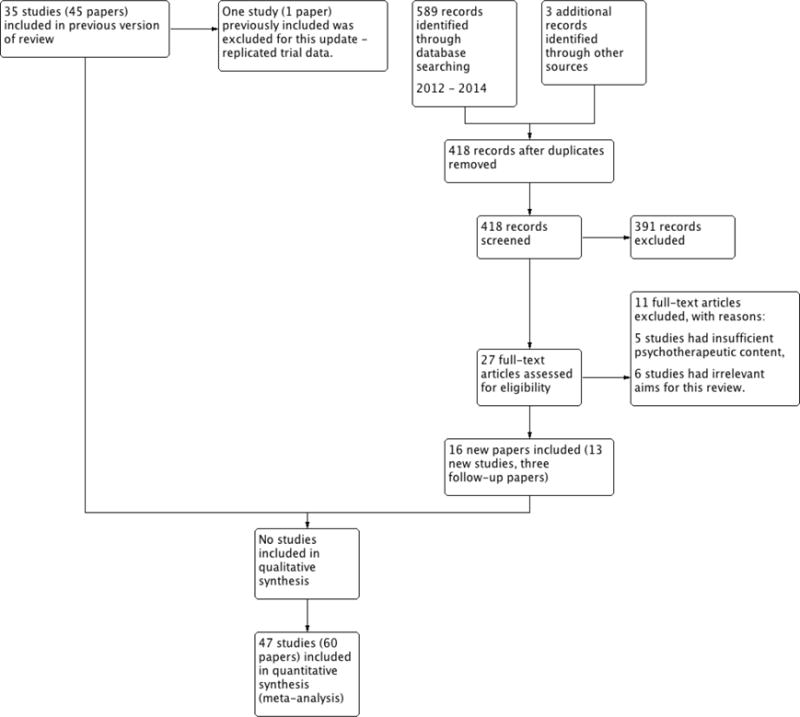

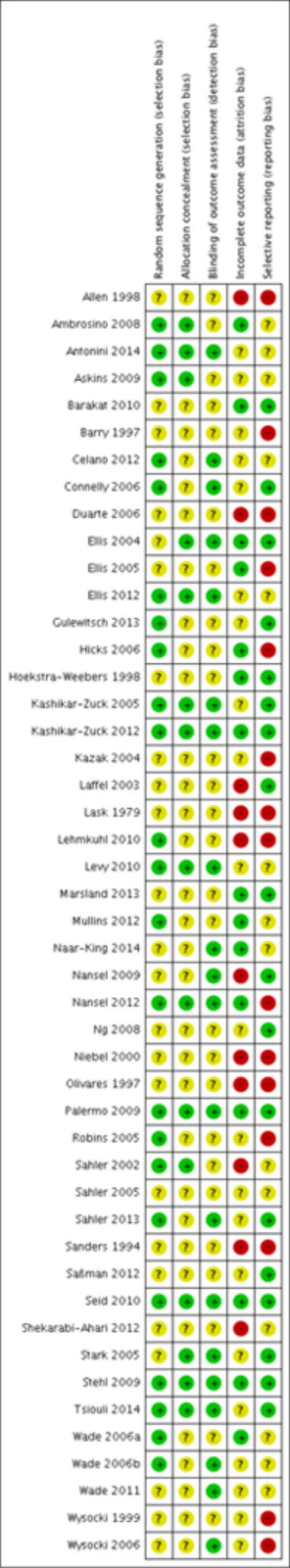

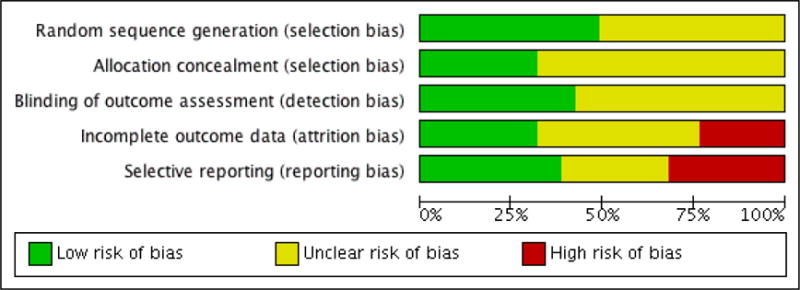

Thirteen studies were added in this update, giving a total of 47 RCTs. The total number of participants included in the data analyses was 2985, 804 of whom were added to the analyses in the update. The mean age of the children was 14.6 years. Of the 47 RCTs, the studies focused on the following paediatric conditions: n = 14 painful conditions, n = 13 diabetes, n =10 cancer, n = 5 asthma, n = 4 TBI, and n = 1 atopic eczema. We did not identify any studies treating parents of children with gynaecological disorders or IBD. Risk of bias assessments of included studies were predominantly unclear. Evidence quality, assessed using the GRADE criteria, was judged to be of low or very low quality.

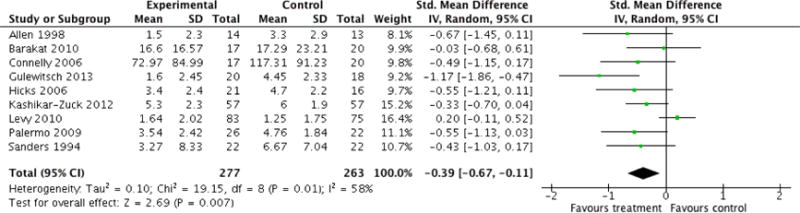

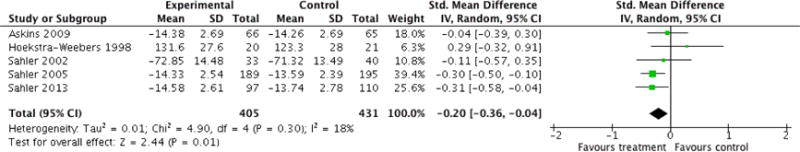

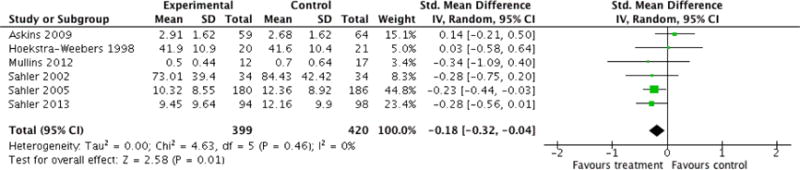

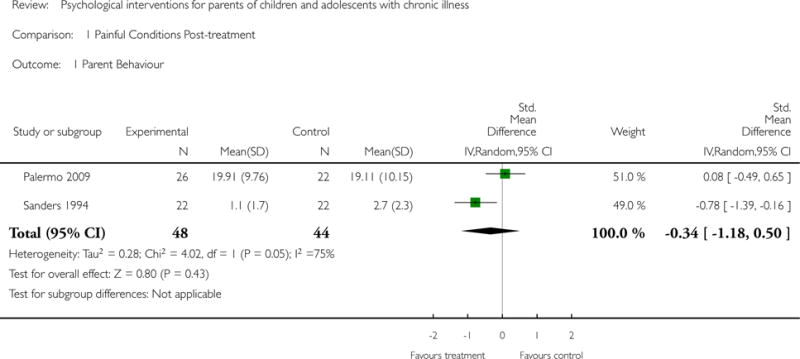

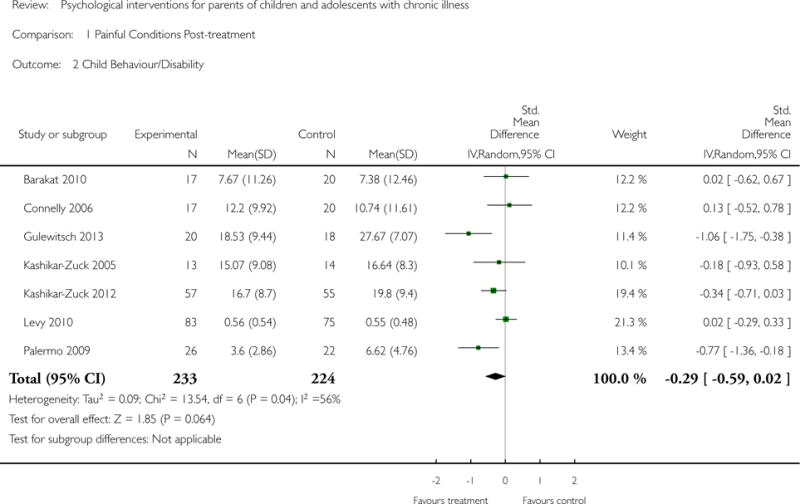

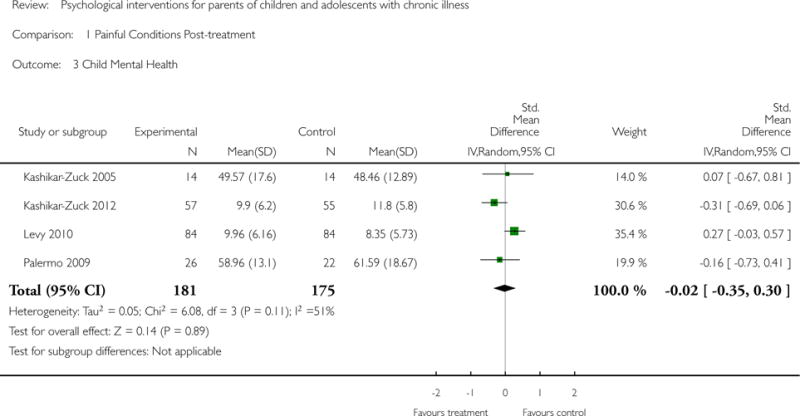

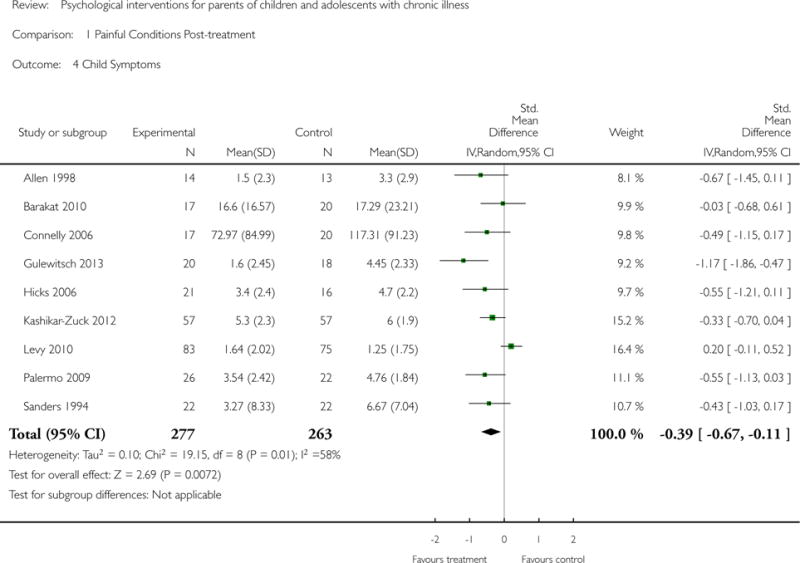

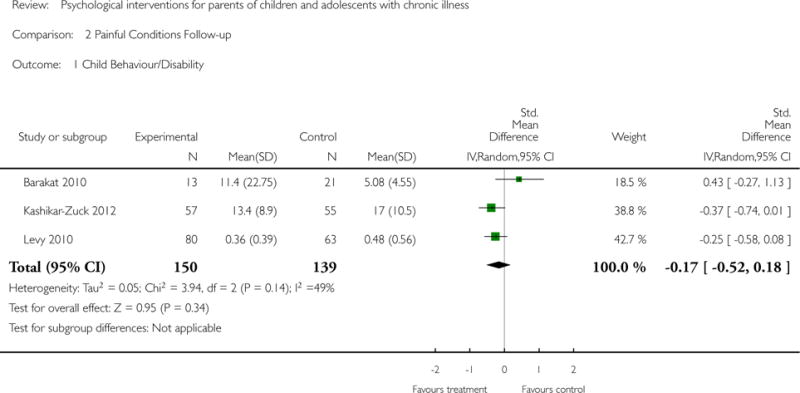

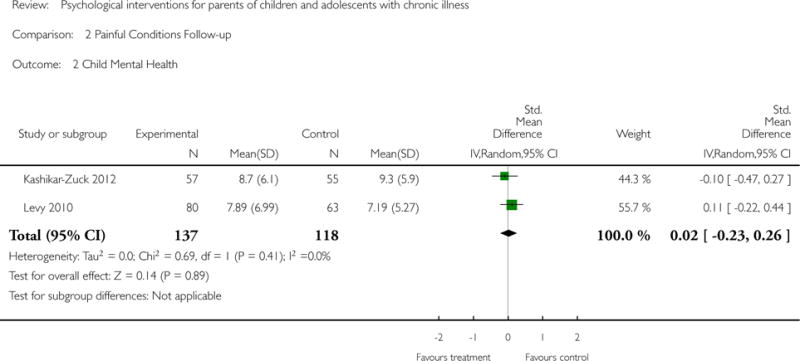

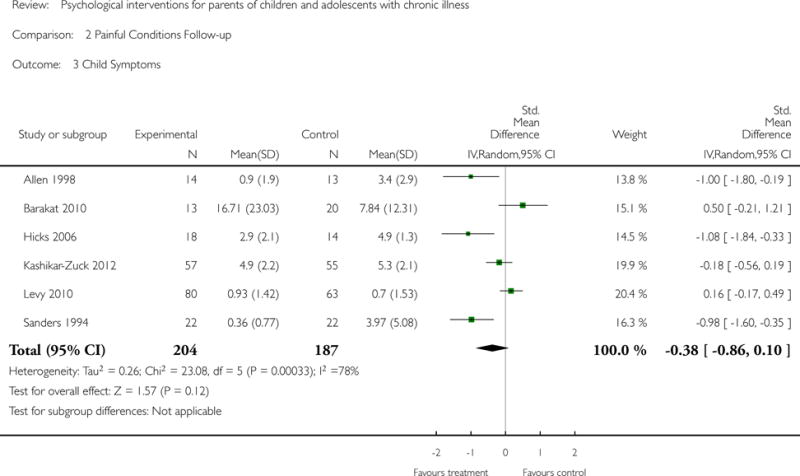

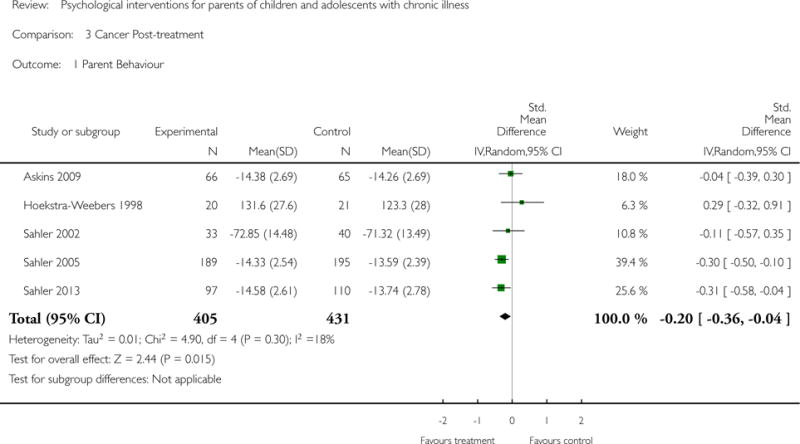

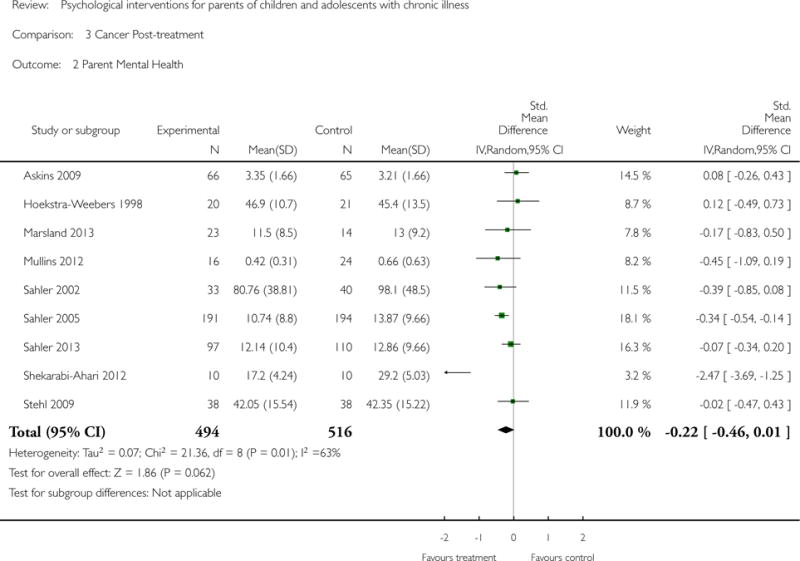

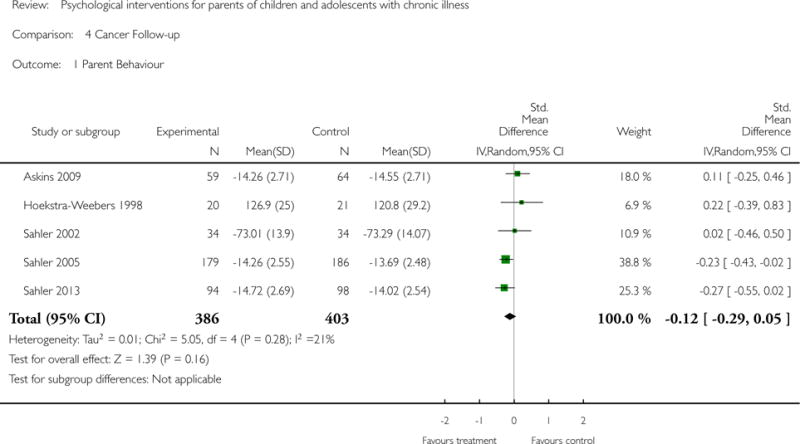

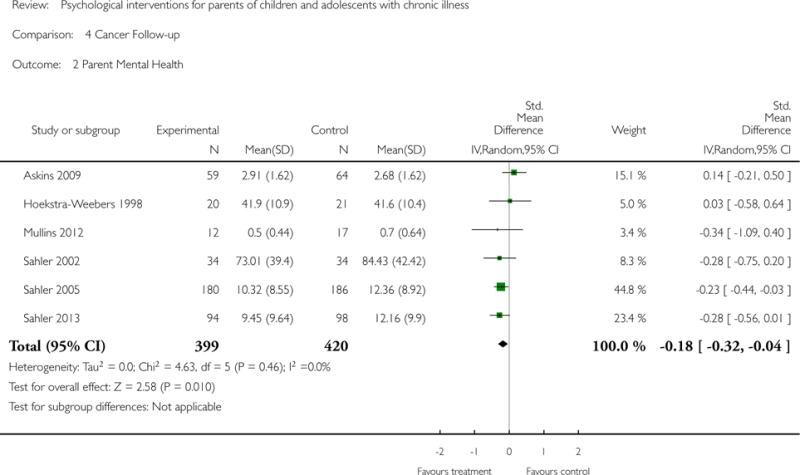

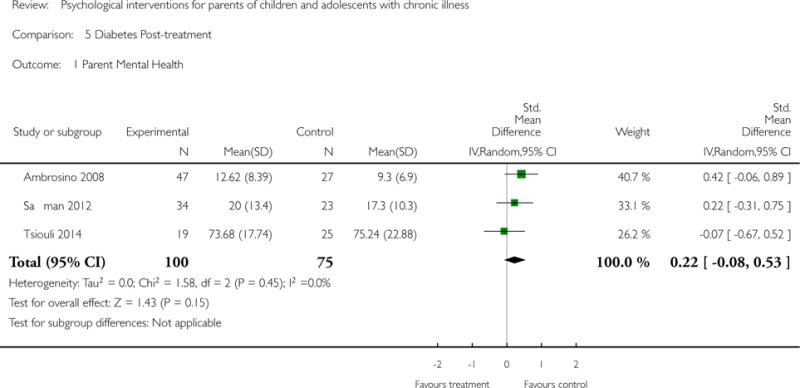

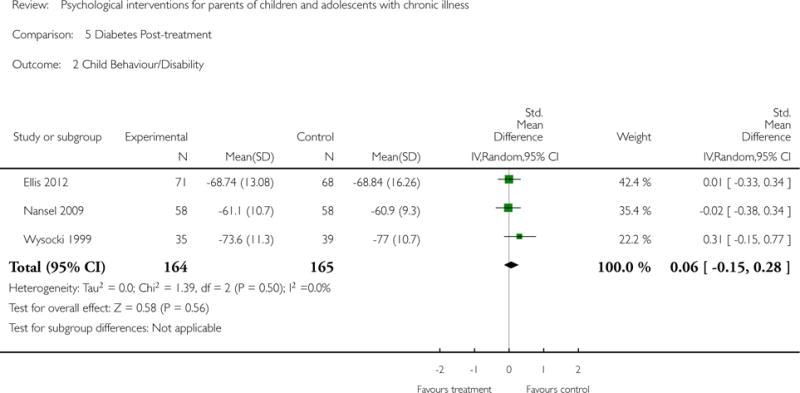

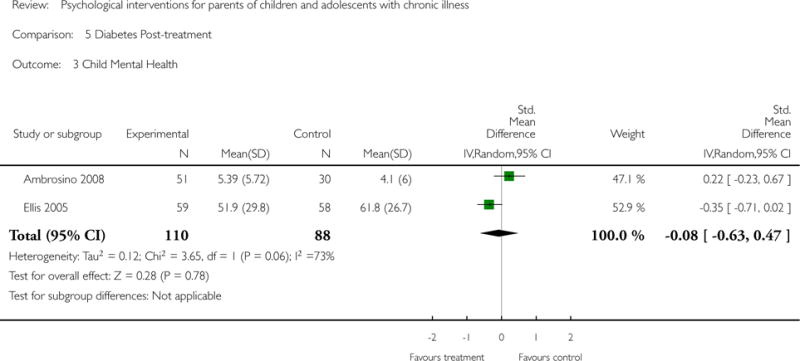

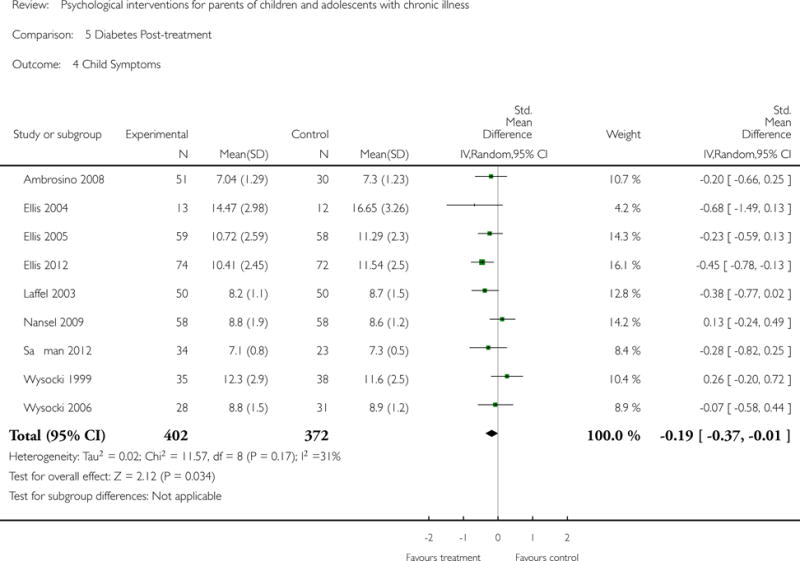

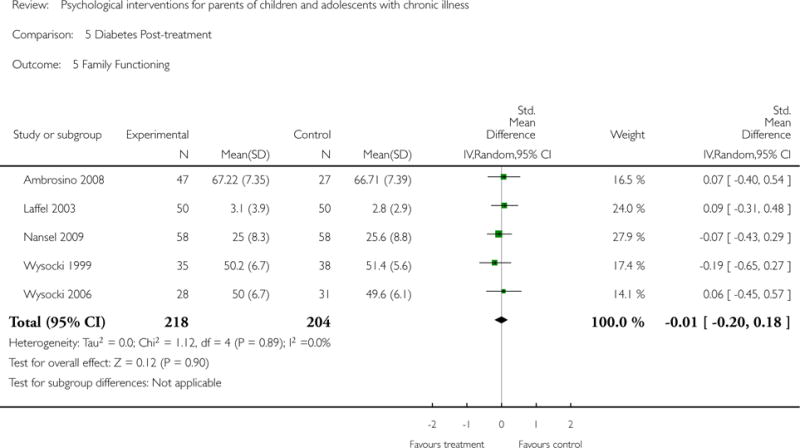

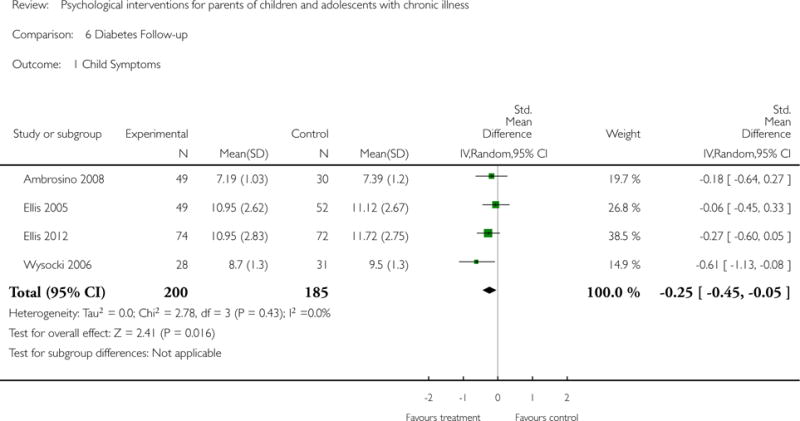

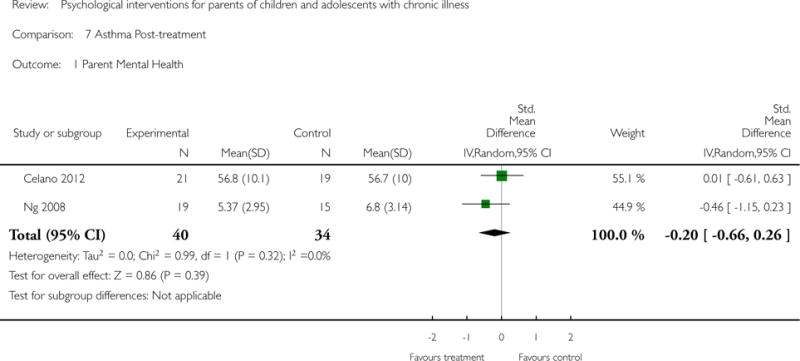

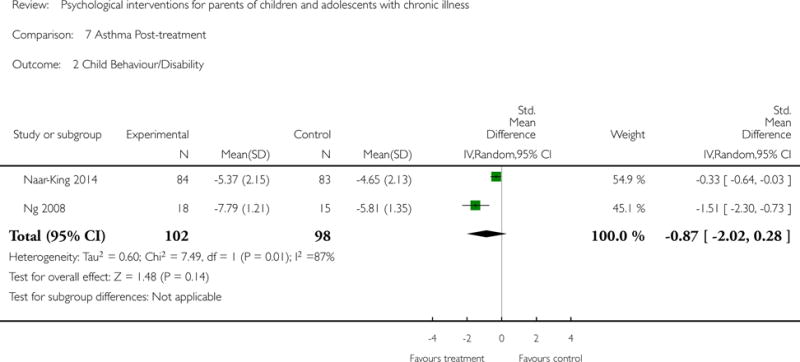

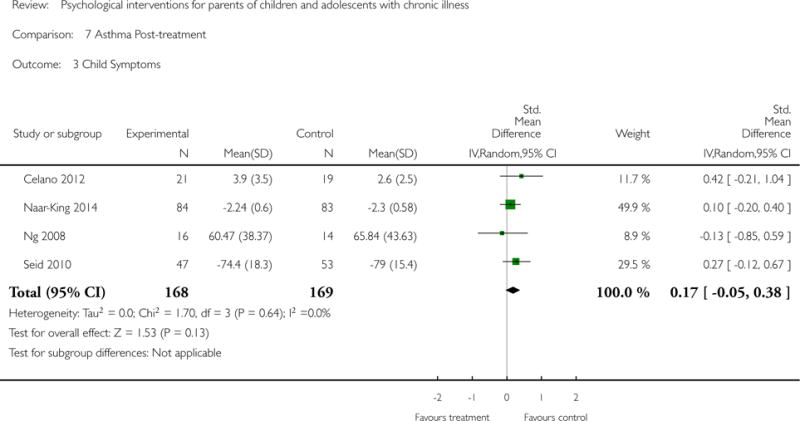

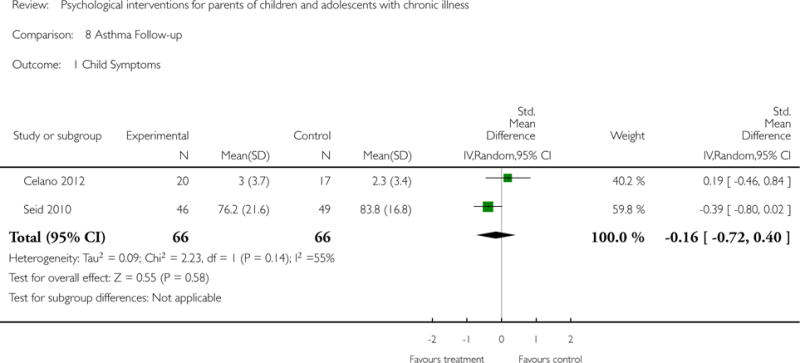

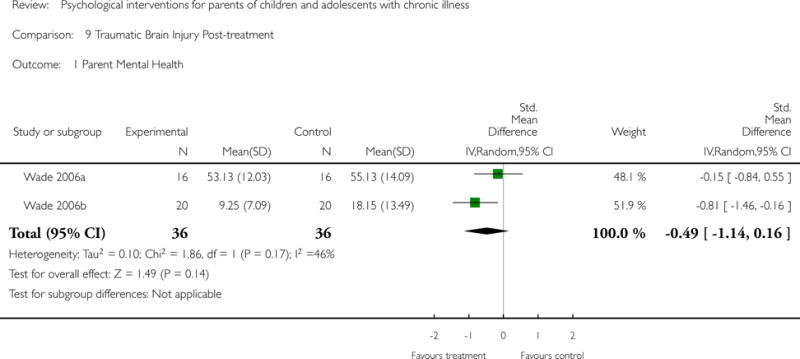

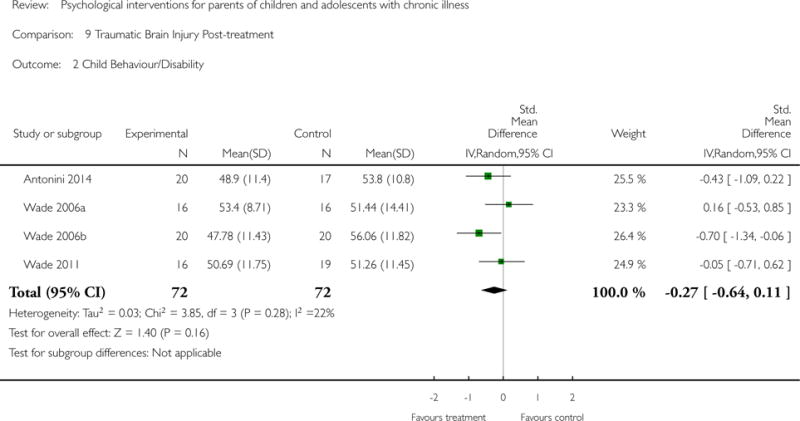

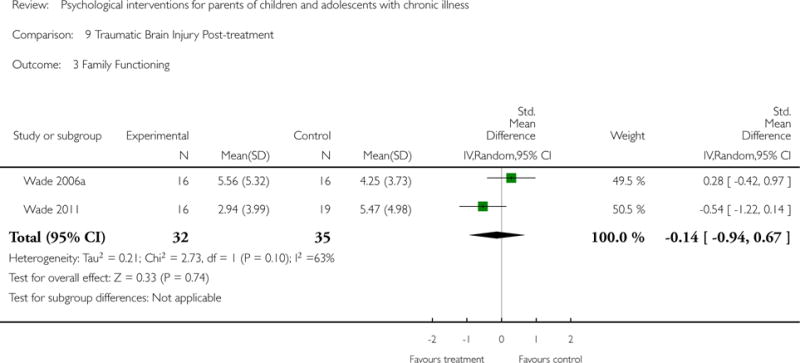

Analyses of separate medical conditions, across all treatment types, revealed two beneficial effects of psychological therapies for our primary outcomes. First, psychological therapies led to improved adaptive parenting behaviour in parents of children with cancer post-treatment (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.36 to −0.04, Z = 2.44, p = 0.01). In addition, therapies also improved parent mental health at follow-up in this group (SMD = −0.18, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.04, Z = 2.58, p = 0.01). We did not find any effect of therapies for parent behaviour for parents of children with a painful condition post-treatment or at followup, or for parent mental health for parents of children with cancer, diabetes, asthma, or TBI post-treatment. For all other primary outcomes, no analysis could be conducted due to lack of data.

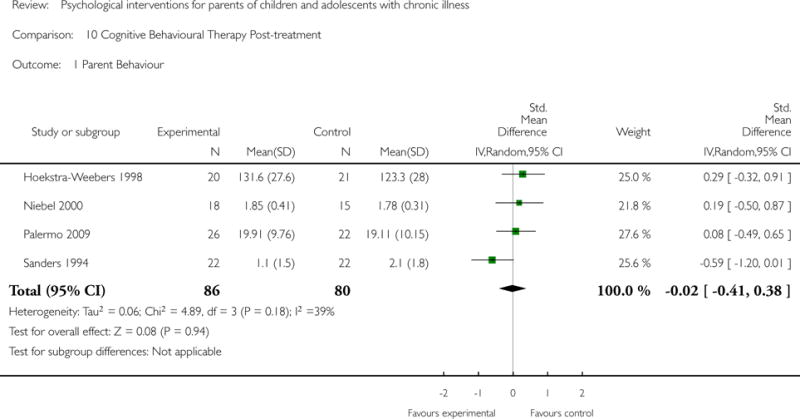

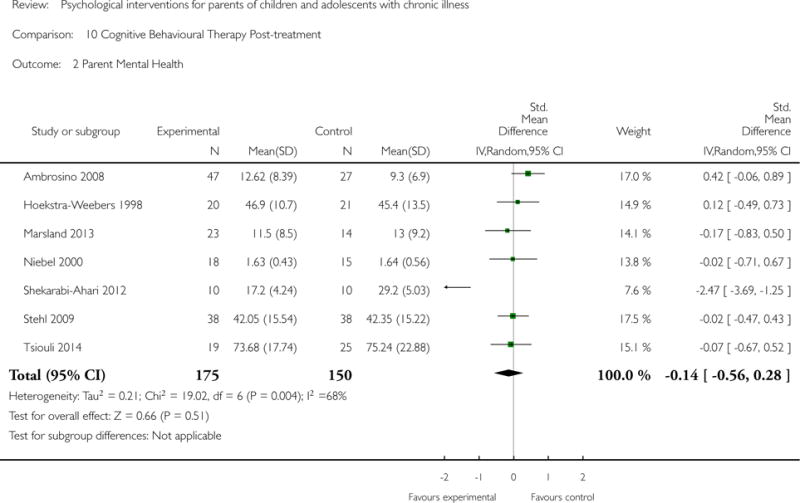

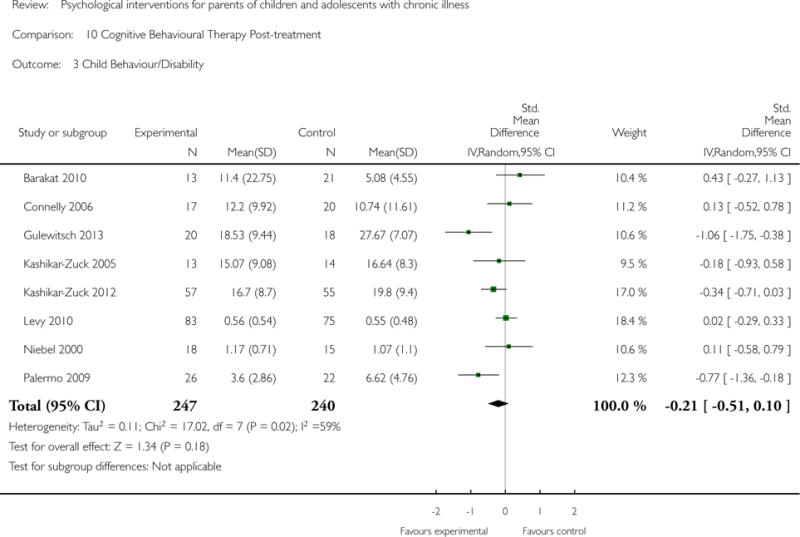

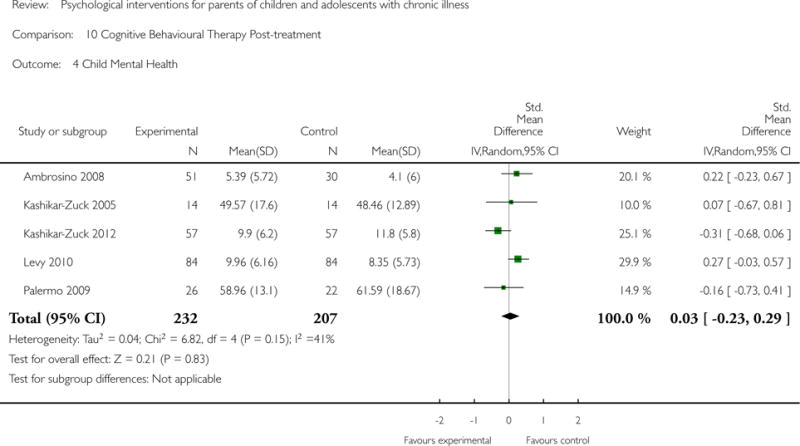

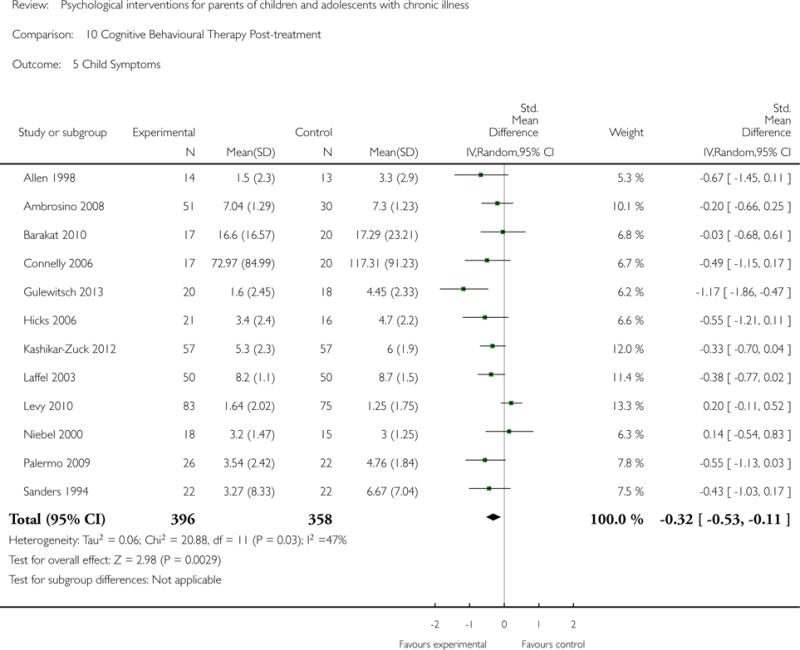

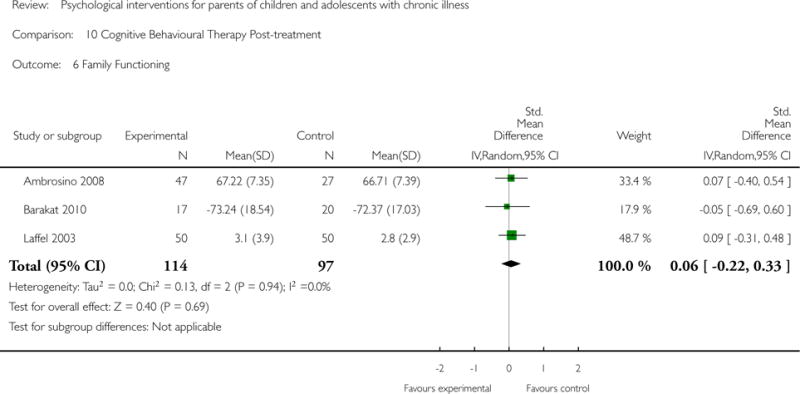

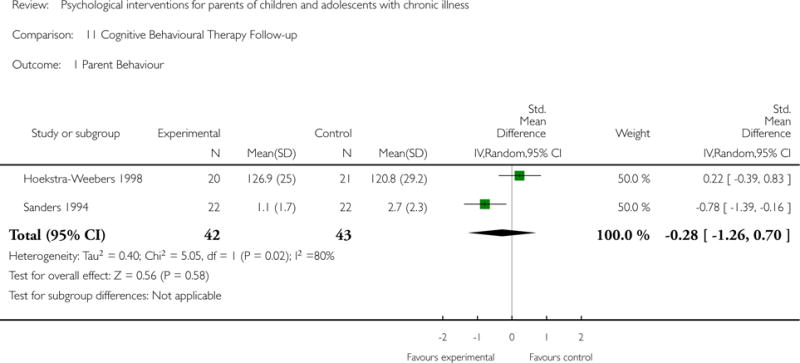

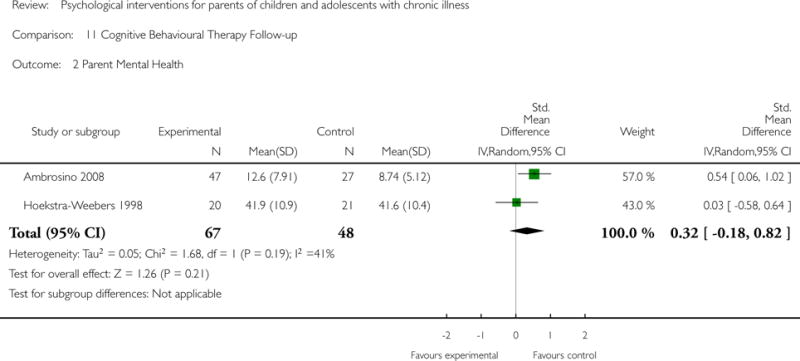

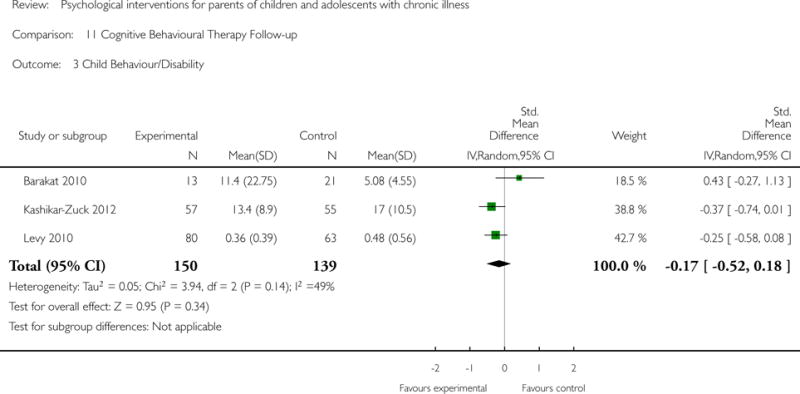

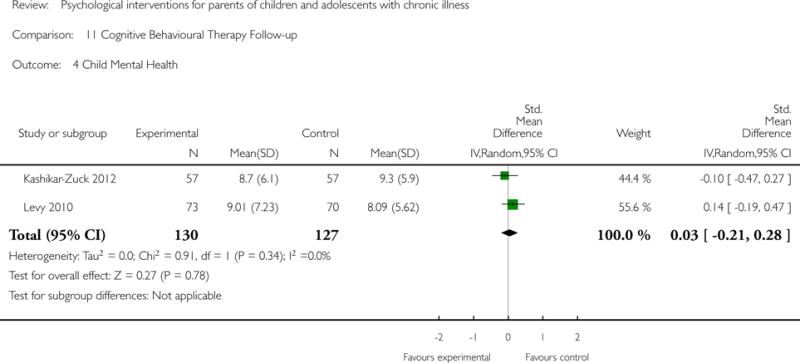

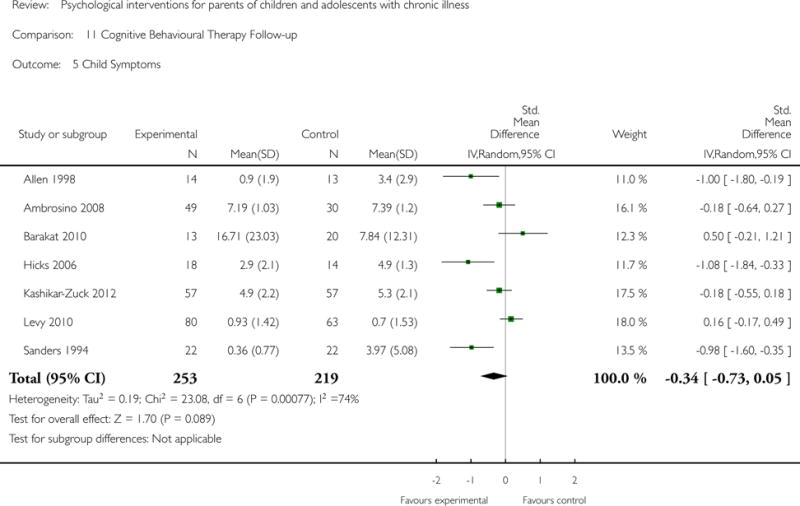

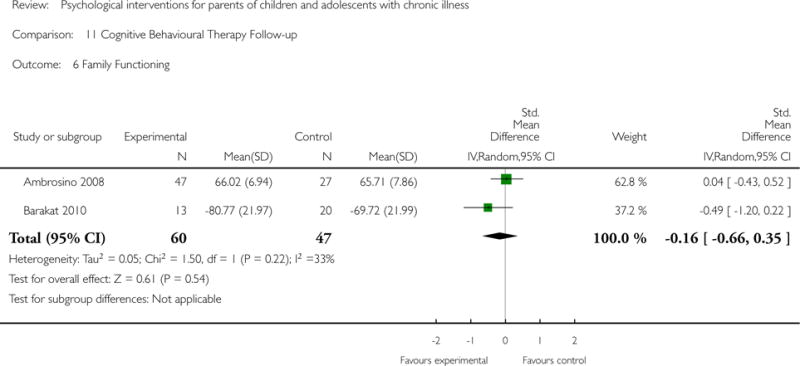

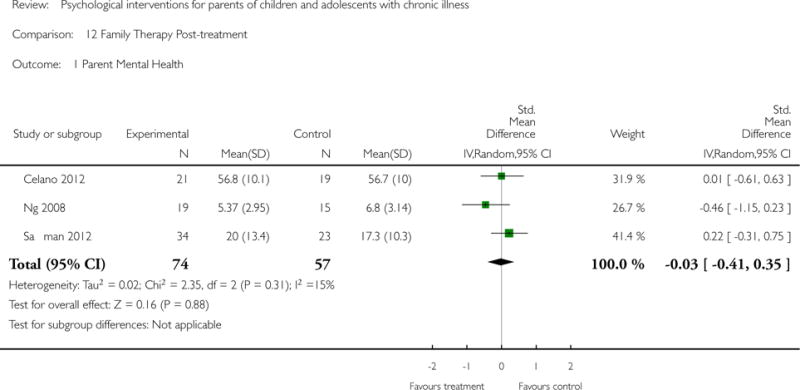

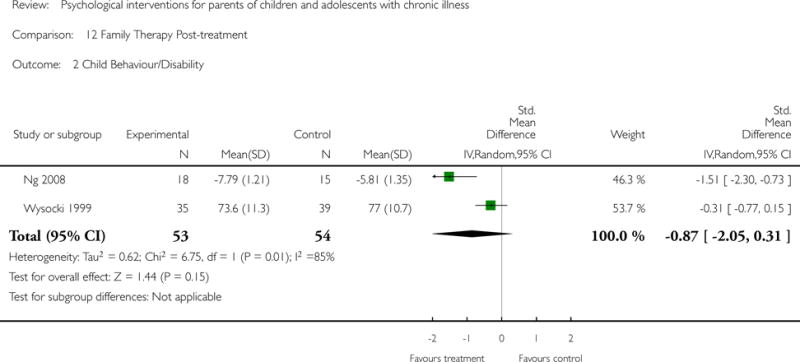

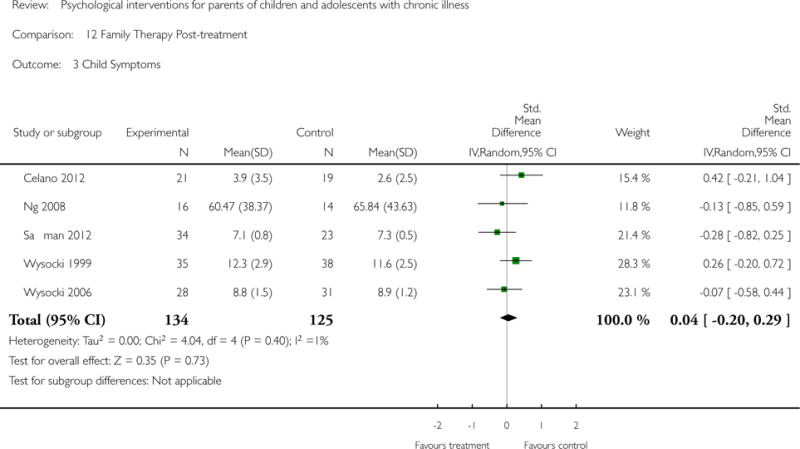

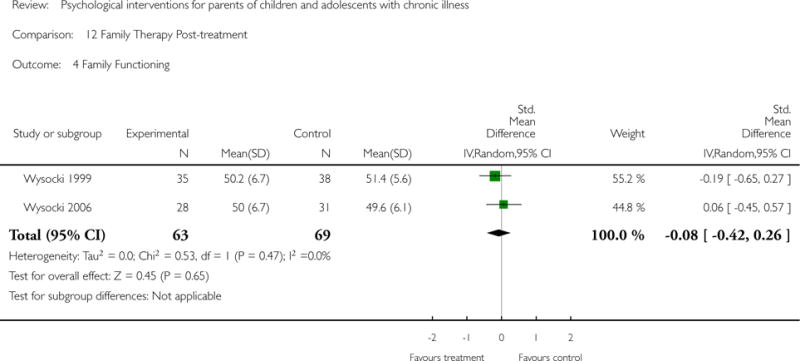

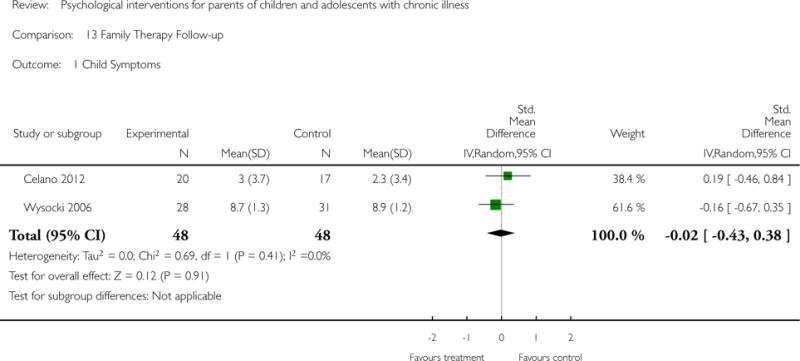

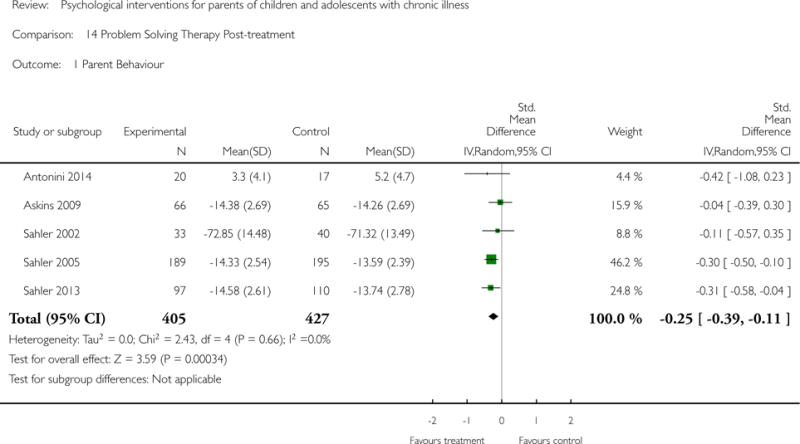

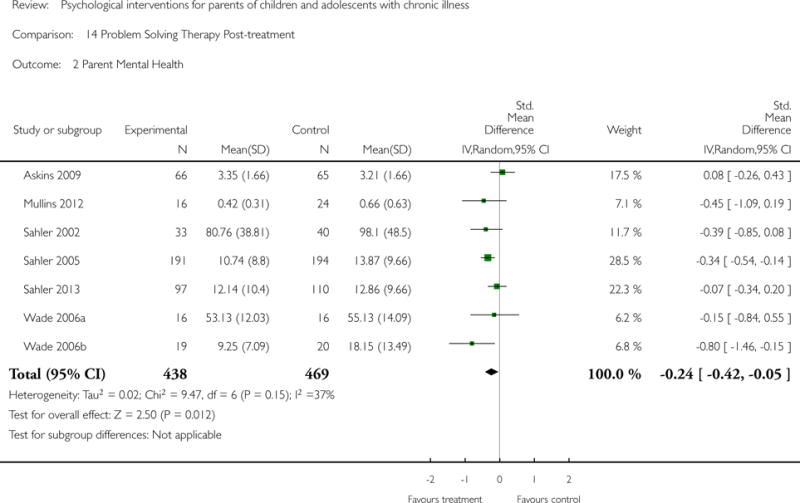

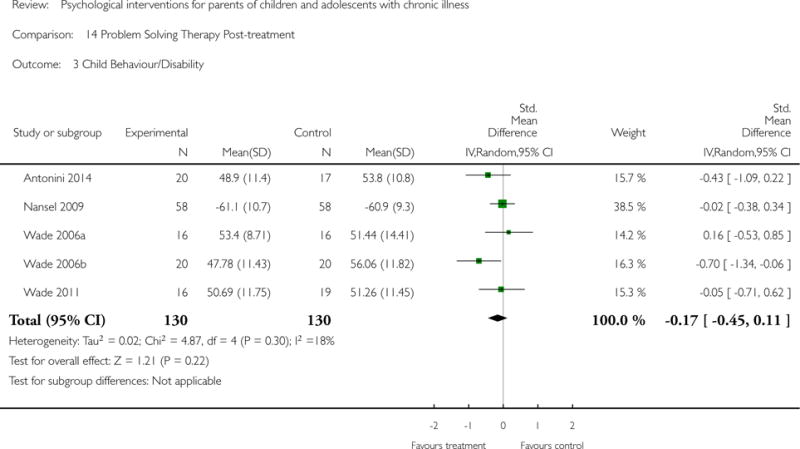

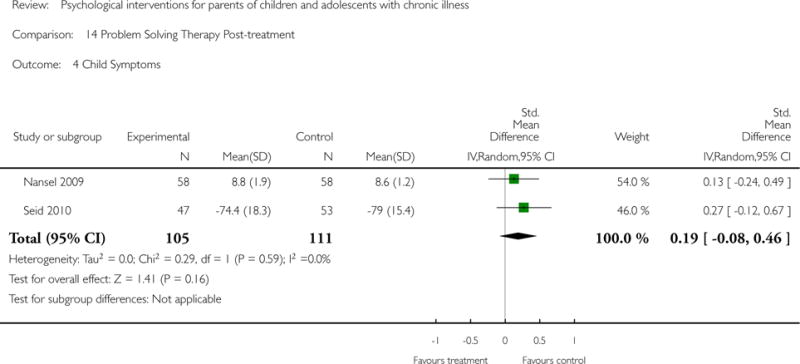

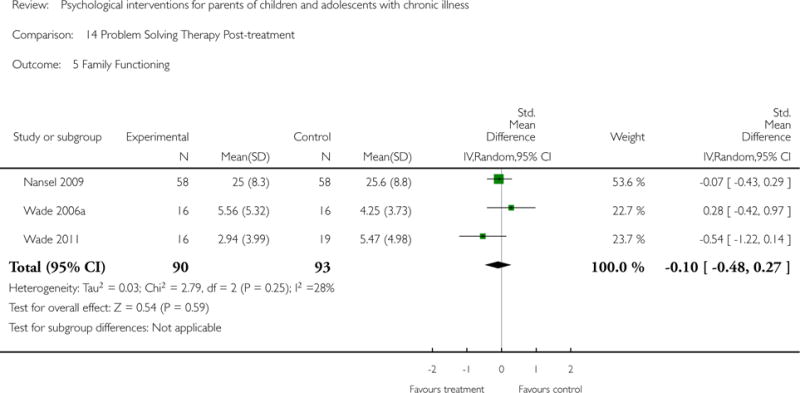

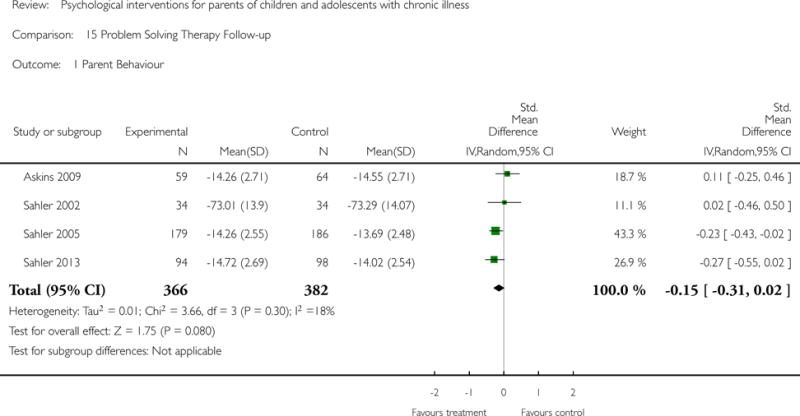

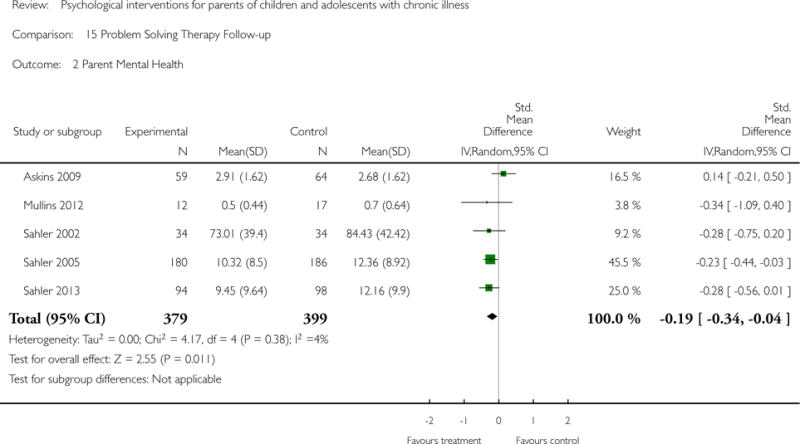

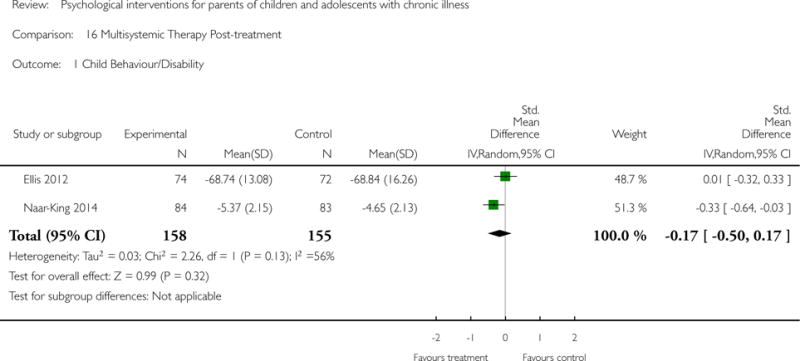

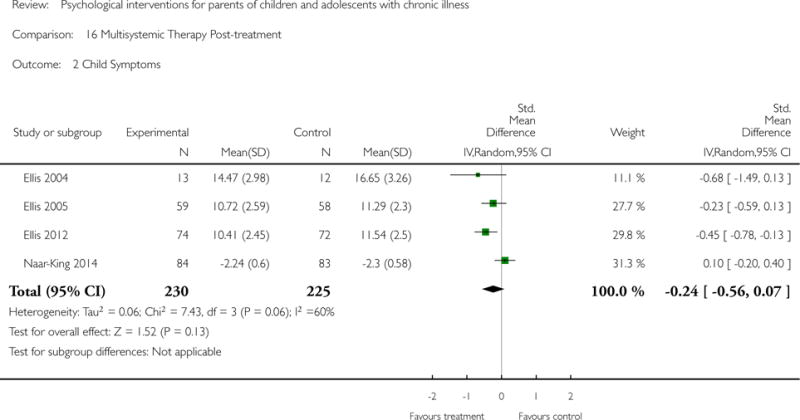

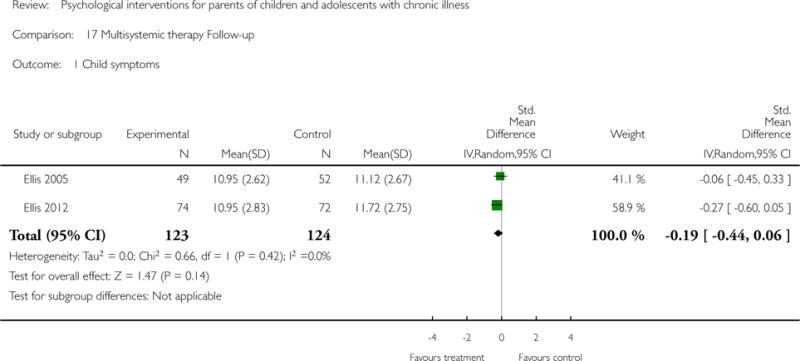

Across all medical conditions, three effects were found for the primary outcomes of psychological therapies. PST had a beneficial effect on parent adaptive behaviour (SMD = −0.25, 95% CI −0.39 to −0.11, Z = 3.59, p < 0.01) and parent mental health (SMD= −0.24, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.05, Z = 2.50, p = 0.01) immediately post-treatment and this effect was maintained at follow-up for parent mental health (SMD= −0.19, 95% CI −0.34 to −0.04, Z = 2.55, p = 0.01). The remaining analysis for PST on parent behaviour found no effect. No effects were found for CBT post-treatment or at follow-up for either parent outcome. For FT, only one analysis could be run on parent mental health and no effect was found. Due to lack of data, the remaining analyses of primary outcomes could not be run. For MST, no parent outcomes could be analysed due to lack of data.

Secondary outcome analyses are presented in the Results section. Five studies reported that there were no adverse events during the trial. The remaining 42 studies did not report adverse events.

Authors’ conclusions

This update includes 13 additional studies, although our conclusions have not changed from the original version. There is little evidence for the efficacy of psychological therapies that include parents on most outcome domains of functioning, for a large number of common chronic illnesses in children. However, psychological therapies are efficacious for some outcomes. CBT that includes parents is beneficial for reducing children’s primary symptoms, and PST that includes parents improved parent adaptive behaviour and parent mental health. There is evidence that the beneficial effects can be maintained at follow-up for diabetes-related symptoms in children, and for the mental health of parents of children with cancer and parents who received PST.

INDEX TERMS: Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Chronic Disease [*psychology], Cognitive Therapy, Family Therapy, Parenting [psychology], Parents [*psychology], Problem Solving, Psychotherapy [*methods], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Adolescent, Child, Humans

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Psychological therapy for parents of children and adolescents with a longstanding or life-threatening physical illness

Background

This is an update of a previously published review published in 2012 investigating the efficacy of psychological therapies for parents of children with a longstanding or life-threatening physical illness. This review updates includes studies that have been conducted in the previous two years to give an up-to-date review of the evidence.

Parenting a child with a longstanding or life-threatening illness is very difficult, and can have a negative impact on many aspects of the parents’ life. Parents of these children often have difficulty balancing caring for their child with other responsibilities and demands. As a result, parents may experience more stress, worries, mood disturbance, family arguments, and their children may show troubling or problematic behaviour. Parents also have a major influence on their child’s well-being and adjustment, and play an important role in how their child adapts to living with an illness. Treatments for parents of children with a longstanding illness aim to improve parent distress, parenting behaviours, family conflict, child distress, child disability and the child’s medical symptoms.

Review question

To evaluate the effectiveness of psychological therapies for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illnesses including painful conditions, cancer, diabetes mellitus, asthma, traumatic brain injury (TBI), inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), skin diseases, or gynaecological disorders. Psychological therapies will be compared to active, treatment as usual, or wait-list controls. There were two primary outcomes of interest: parent mental health and parenting behaviour. We included five secondary outcomes; child behaviour/disability, child mental health, child symptoms, family functioning, and adverse events.

Study characteristics

The search was completed in July 2014. Forty-seven studies were found in the search including 3778 participants. The average age of the children was 14.6 years. We found studies that focused on six chronic illnesses (painful conditions, cancer, diabetes, asthma, traumatic brain injury and eczema) and evaluated four types of psychological therapies (cognitive behavioural therapy, family therapy, problem solving therapy, multisystemic therapy). Outcomes were extracted from the time point immediately after the treatment and at the first available follow-up. We analysed the data in two ways: first we grouped the studies by each individual illness (across all therapies) and then we grouped the studies by each individual psychological therapy (across all chronic illnesses).

Key Results

Psychological therapies improved parenting behaviour of parents of children with cancer immediately following treatment. Parent distress also improved for parents of children with cancer. Children with painful conditions and those with symptoms of diabetes showed benefit immediately following treatment, and for diabetes the reduction in symptoms was maintained at follow-up. When analysing different psychological therapies, we found cognitive behavioural therapy can improve the child’s medical symptoms. Problem-solving therapy can improve a parent’s distress and their ability to solve problems, with the reduction in parental distress continuing long-term. Five studies reported that there were no adverse events during the study period. The remaining studies failed to report or discuss adverse events. Risk of bias assessments of included studies were predominantly unclear due to poor reporting.

Conclusion

There is evidence that psychological therapies including parent interventions can benefit parents of children with a chronic illness, particularly for parents of children with cancer. However, due to the small number of studies in this review, future studies are likely to change the findings in this review.

BACKGROUND

This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review published in Issue 8, 2012 (Eccleston 2012b).

Description of the condition

Chronic illness affects the lives of many children and their families. The prevalence of illness and disability differs by geographical and economic context. In the USA, Canada, Northern Europe, UK and Australia chronic activity-limiting conditions are reported to be frequent, with painful illness, allergy, asthma and obesity being common (McDougall 2004). The changing demographic of childhood illness in economically wealthy countries has prompted a re-analysis of the role of paediatric medicine, as chronic illness becomes more prevalent than acute (e.g. Halfon 2010; Van Cleave 2010). Other parts of the world present different clinical challenges. In Africa, for example, life expectancy is 54 years and shorter in sub-Saharan Africa where almost half the population are children and the most prevalent chronic conditions are related to communicable diseases, in particular HIV-related disease, malaria and tuberculosis (WHO 2011).

The existing published literature shows a bias towards the medical management of chronic illness related to environment or lifestyle. Chronic pain in childhood is known to have widespread negative outcomes for children and parents (Palermo 2000). Psychological intervention reviews have also been undertaken on the impact of sickle cell disease (Anie 2012), recurrent abdominal pain/irritable bowel syndrome (Huertas-Ceballos 2008), type 1 diabetes (McBroom 2009), traumatic brain injury in children (Soo 2007) and asthma (Yorke 2005).

The impact of childhood chronic illness on other family members, including parents, has been of growing interest for two reasons. First, it is now recognised that parents who have significant emotional distress of their own, and poor family functioning, can either directly or indirectly affect child outcomes by engaging in problematic responses to children’s pain behaviours (Logan 2005; Palermo 2007). Second, it is now recognised that adaptive strategies used by parents can have a positive effect on child adjustment to chronic illness (Logan 2005).

Description of the intervention

Addressing the high level of parenting stress and mental health problems of parents, while enabling parents to be agents of change in the management of their child’s chronic illness, have recently been promoted as viable components of intervention in paediatric chronic conditions (Jordan 2007; Palermo 2009b). Studies have focused on the education of parents about the specific condition or treatment (e.g. cystic fibrosis; Savage 2014), whilst others evaluate the benefit of lay- or nurse-mediated social support (e.g. Lewin 2010). In psychological science, specific treatment approaches have been developed that focus on reducing the emotional distress expressed by parents, or on altering parenting behaviours to promote better child outcomes, whether this be decreasing emotional distress, or improving physical symptoms or behaviour.

Psychological interventions of interest are defined as any psychotherapeutic treatment specifically designed to change parent cognition or behaviour, or both, with the intention of improving child outcomes. Psychological interventions are varied in their approaches and there is still debate surrounding which treatment is most effective for improving mental health and behaviour in parents and children with chronic illnesses. Such interventions include cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which has been found to be effective for modifying parent behaviour in children with a painful condition (e.g. Palermo 2009a; Williams 2012). Problem-solving therapy (PST) has also been used to reduce distress in parents of children with various chronic illnesses (D’Zurilla 1971; Sahler 2002). Other treatments have emerged from a family-systems approach that focuses explicitly on the family as a unit of intervention (Ellis 2005; Wysocki 2000) such as multisystemic therapy (MST) or family therapy (FT).

How the intervention might work

There are a variety of interventions described as psychological. Cognitive and cognitive behavioural therapies dominate, but therapies with a psychodynamic or systemic tradition are also represented. Family and couple therapies have also been developed. All psychological interventions include a rationale for therapy and specific goals for therapy. Education around illness and behaviour is common. Establishing the therapy and the therapist as credible is an important general stage (Nock 2001). Next, a therapeutic relationship is established that will enable a confidential, non-blaming investigation of behaviour. Then, depending on the illness and behavioural presentation, specific components may include anxiety management, problem-solving skills, cognitive therapy for depression, and relationship management. Finally, most treatments will include a maintenance component that focuses on robust behavioural change within a normal home environment outside the clinic, over time. Such components have been used in parent interventions using different therapies to improve parental functioning, child behaviour and mental health.

Cognitive behavioural interventions specifically are based on a number of foundational assumptions (Beck 2011). First, behaviour is socially and historically contingent (Skinner 1953). Second, cognition is an emergent property of behavioural context (James 1980). Third, behaviour is regulated by cognitive goals (Bandura 1989). Fourth, emotions influence both behaviour and cognition (Ashby 1999; Gilliom 2002). Fifth, most behaviour is deployed outside of conscious awareness or control (Bargh 2008). Finally, some attempts to control cognition and behaviour can have paradoxical negative effects on desired outcomes (Beck 2011; Wegner 1994).

Other interventions such as PST (D’Zurilla 1971) are based on enhancing social competence through constructive problem-solving attitudes and skills. PST is based on a model of social problem-solving (D’Zurilla 1999). Specific problem-solving skills are taught in sequential steps that typically include defining the problem, generating alternative solutions, decision making, and solution verification and implementation. PST has previously been effective with depression, anxiety and stress-related syndromes (D’Zurilla 1999) and has been implemented with caregivers in a number of contexts.

Family and systemic therapies specifically focus on a contextual and relational view of the aetiology and maintenance of behaviour. In particular, the target of health behaviour change is typically related to family functioning, or in the cognitive representation of the family, rather than on individual attitudes, beliefs or behaviour. Typically, family or systems therapy approaches will include multiple family members, and outcomes are often expressed on behalf of the family or dyad (two individuals regarded as a pair).

Why it is important to do this review

Chronic illness is experienced by children, but within the context of the family. Parents are often detrimentally affected by their child’s illness, which adds a burden of adult distress to the child’s distress and disability. Further, parent distress can impair their performance in supporting their child in adapting to a chronic illness. Psychological interventions are available which focus on helping parents to help both themselves and their children. Establishing the evidence at this stage of development can guide best practice and further treatment development.

OBJECTIVES

To evaluate the efficacy of psychological therapies that include parents of children and adolescents with chronic illnesses including painful conditions, cancer, diabetes mellitus, asthma, traumatic brain injury (TBI), inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), skin diseases, or gynaecological disorders. We also aimed to evaluate the adverse events related to implementation of psychological therapies for this population.

To evaluate the risk of bias of included studies and the quality of outcomes using the GRADE assessment.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of psychological interventions that include a parent component, compared with attention control, other active treatment, or waiting-list control groups. The parent intervention had to be primarily psychological in nature. Studies that met the inclusion criteria consisted of the following:

RCT, published in full in a peer-reviewed journal;

Primary aim of the trial was an evaluation of a psychological intervention;

Involved parents of children who have an illness for three months or more (Van der Lee 2007);

Involved parents of children adjusting to a diagnosis of cancer;

Had a participant n of 10 or more in both the treatment and control arm at end of treatment or at follow-up.

Types of participants

Parents of a child who has endured a chronic illness for three months or more, or who was recently diagnosed with a condition (e.g., cancer) that is expected to last more than three months. We regard parents as the primary caregiver of a child or adolescent under the age of 19 years. We define parents for the purposes of this review as any adult who adopts the responsibility for the role of parenting the child (this could include biological parent, guardian, or other adult family member). There was no lower age limit for the children; however, by the definition of ’chronic illness’, the child must be three months or older. Physical illnesses that were considered for inclusion were:

Asthma;

Cancer;

Diabetes mellitus;

Gynaecological disorders (e.g. chronic dysmenorrhoea and endometriosis);

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD);

Painful condition (including but not exclusively limited to arthritis, back pain, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), fibromyalgia, headache, idiopathic pain conditions, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), recurrent abdominal pain);

Skin diseases (e.g. eczema);

Traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Chronic illnesses were selected from the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs 2009 to 2010 (Data Resource Center 2010). It was impractical to include all chronic illnesses on this list therefore we selected the most common. However, three illnesses (cancer, inflammatory bowel diseases and gynaecological disorders) were not included in the list of ‘Current Health Conditions and Functional Difficulties’ but were added for the purposes of this review. Cancer has a high incidence level, and in the UK alone 1600 0–14 year-old children are diagnosed with cancer each year (Cancer Research UK 2014). In the USA, it is estimated that 15,780 0–19 year-olds are diagnosed with cancer (National Cancer Institute 2014). Studies that delivered interventions to parents of children who have ’survived’ an illness but still experienced distress, such as childhood survivors of cancer, were also eligible for inclusion. Inflammatory bowel diseases and gynaecological disorders are also common conditions in childhood and adolescence, and are included because they are thought to be prevalent but under-represented in the academic literature.

Types of interventions

Studies were included if the interventions were primarily psychological, and had credible, recognisable psychological/psychotherapeutic content, and were specifically developed for, or included parents. Psychological interventions were defined as any psychotherapeutic treatment specifically designed to change parent cognition or behaviour, or both, and had the intention of improving parent or child outcomes. However, studies that included parents as ’coaches’ to support exclusively child-focused interventions were excluded from this review. The intervention had to aim to provide treatment to the parent rather than teach them to deliver an intervention to their child. Similarly, we also excluded health promotion therapies such as intervening with the parent to cease smoking to improve their child’s asthma. We have excluded studies that combine psychological interventions with pharmacological interventions or are qualitative in nature, because it is difficult to combine qualitative and quantitative data.

Types of outcome measures

Parent outcomes were the primary target of our review. However, if the study also reported child outcomes as stated below, we also analysed and reported these data as secondary outcomes. We analysed data at post-treatment and the first available follow-up period, where reported.

Primary outcomes for the purposes of this review include parenting behaviour and parent mental health. Secondary outcomes include child behaviour/disability, child mental health, child illness-related symptoms, family function and adverse events.

We made a judgement when studies reported multiple measures within one of the six outcome domains and did not define their primary or secondary outcome measure. The rules of this judgement were to select the most generic, reliable, and most frequently used measure within the field, and most appropriate for the given outcome category. When both parents and children reported on a measure, we extracted the self-reported item unless the non-self-reported measure was a more generic measure. For family functioning measures, we preferentially extracted parent data over child data, as the review is focused on whether interventions can help parents of children with a chronic illness.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Two searches have been conducted. The first, from inception to March 2012, and the second from March 2012 to July 2014. We searched four databases for studies for this update. The dates listed below state the most recent date of our search.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Library, Issue 6, 2014;

MEDLINE via Ovid, 1946 to 30/6014;

EMBASE via Ovid, 1974 to 30/6/14;

PsycINFO via Ovid, 1806 to June week 4 2014.

We adapted the search strategies from the MEDLINE search (for all search strategies see Appendix 1). There was no language restriction imposed and no unpublished literature or grey material was included, so only the highest quality trials were included. The search strategy included four categories of words: psychological interventions, parents, children/adolescents and chronic illnesses (as stated above), and was refined by a methodological filter used to identify RCTs according to Cochrane guidance (Higgins 2011).

Searching other resources

We performed a reference list and citation search of all included studies. Relevant meta-analyses and systematic reviews were searched for additional studies. We also contacted authors of selected studies and experts in the field for further studies that had not already been identified from the search. In addition, we searched online trial repositories for additional studies including metaRegister of controlled trials (mRCT) (www.controlledtrials.com/mrct/), ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov), and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (EF, EL, JB) sifted through potential studies and identified those eligible to be included, with CE acting as arbiter. No blinding of study authors’ names, institutions or journals occurred during this process. We resolved any disagreements by discussion between all review authors.

We made selection of abstracts using the following criteria.

- Participants

-

◦Parents had to be referred to in the title or abstract of each study;

-

◦The parent had to be the primary caregiver of the child;

-

◦Children had to have one or more of the chronic illnesses listed above;

-

◦Children had to be in the age range three months to 19 years;

-

◦There had to be 10 or more participants in each condition at the end of the treatment assessment.

-

◦

- Intervention

-

◦The intervention had to be primarily psychological in at least one treatment arm;

-

◦Design was an RCT;

-

◦One or more parents had to be treated by the intervention;

-

◦The parents or child or both had to complete assessments at baseline and at a point in time during or after the intervention.

-

◦

- Comparison groups

-

◦Active treatment group;

-

◦Treatment-as-usual group (e.g. usual doctors’ appointments and treatment without added psychological therapy);

-

◦Waiting-list control.

-

◦

Quantitative outcomes had to be presented We then obtained the selected studies meeting the criteria in full and EF, EL and JB read and assessed them independently.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (EF, EL and JB) carried out data extraction from studies that were identified by all review authors as appropriate for inclusion. We extracted demographics of parents and children (e.g. age, sex), characteristics of the child’s illness (e.g. diagnosis, length of illness), and characteristics of therapy (e.g. setting, components, treatment team, therapy type). Finally, we extracted relevant outcomes for analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias using the recommended Cochrane guidance (Higgins 2011). Of the six suggested ’Risk of bias’ categories, we judged studies on random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective reporting (reporting bias). We excluded the option of ’blinding participants and personnel’ because we deemed it redundant because personnel cannot be blinded to whether they deliver a treatment.

Decisions about random sequence generation were based on whether authors gave a convincing method of randomisation. Participants being stratified by age or sex did not count as biased. Allocation concealment judgements were based on whether sufficient methods were employed for random allocation to take place. We judged risk of blinding of outcome assessment on whether the measures were administered and collected by an assessor who was blind to the treatment allocation. For attrition bias, we assigned a low risk of bias when authors gave both a description of attrition and stated that there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers. We judged there to be unclear risk of bias when there was an adequate description of attrition but authors did not report whether there were significant differences between completers and non-completers. We judged there to be a high risk of attrition bias when no description of attrition was reported.

We judged selective reporting bias on whether data were fully reported in the study or if authors later responded to data requests. We assigned a low risk of bias when all the data were reported in the paper, an unclear risk of bias when authors responded to data requests, and a high risk of bias when the data were not reported in the paper and authors did not respond to data requests. Previously we had rated the concordance between the aims, measures, and results of studies; however, we decided not to conduct this assessment for this update and deleted previous ratings.

The original version of this review included quality assessments advocated by Yates 2005. However, for this update we used the GRADE assessment of quality in accordance with Cochrane guidance (Higgins 2011). Quality of evidence using GRADE was assessed in order to determine the quality of evidence and to enable a summary of the level of confidence in the estimate of effect. First, GRADE assessments for parent outcomes combining all psychological therapies are presented. Second, GRADE assessments for all outcomes for each medical condition are presented.

There were five categories that were assessed to obtain a GRADE rating for an outcome: limitations in the design, indirectness of evidence, unexplained heterogeneity, imprecision of results, and probability of publication bias. Quality ratings could be downgraded from high to either moderate, low, or very low quality evidence.

For limitations in the design, the category was downgraded once if the majority of risk of bias ratings from included studies in an outcome were rated as ’unsure’ or ’high’ risk of bias. It was downgraded twice if there were a high proportion of high risk ratings. For indirectness of evidence, if 50% or more of studies had a waiting-list control the outcome was downgraded once, however if 75% or more had a waiting-list control, the outcome was downgraded twice. The inconsistency of results was downgraded once when the heterogeneity of the analysis was more than 45% and downgraded twice when the heterogeneity was 75% or more. For imprecision of results, we downgraded the outcome if the included studies had fewer than 500 participants. Outcomes were downgraded twice if there were fewer than 150 participants contributing to an outcome. Last, for publication bias, we downgraded outcomes where 50% or more of the contributing studies had a high risk of bias rating for publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We investigated four classes of psychological therapies: cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), family therapy (FT), problem-solving therapy (PST) and multisystemic therapy (MST). CBT is based on theories of behavioural analysis (Bergin1975), cognitive theory (Beck 1979) and social learning theory (Bandura 1977). CBT therefore includes a range of strategies with the goals of modifying social/environmental and behavioural factors that may exacerbate or cause symptoms, and modifying maladaptive thoughts, feelings and behaviours to reduce symptoms and prevent relapse. FT is based on family systems theory (Haley 1976; Minuchin 1974), which emphasises the role of the family context in an individual’s emotional functioning. FT interventions typically focus on altering patterns of interactions between family members, and include structural family therapy (Minuchin 1974), strategic family therapy (Haley 1976) and behavioural systems family therapy (Robin 1989). PST is based on the D’Zurilla 1982 social problem-solving model, which defines problem solving in terms of an individual’s ability to recognise problems and use a positive orientation and problem-solving skills to solve them. PST includes didactic instruction in problem-solving skills, followed by in-session modelling, behavioural rehearsal and performance feedback, as well as homework assignments (D’Zurilla 2007). Finally, MST is an intensive family- and community-based intervention based on the Bronfenbrenner 1979 social ecological model and family systems theory (Haley 1976; Minuchin 1974). MST therefore targets the child, their family and broader systems such as the child’s school, work or medical team as needed. MST incorporates a wide range of evidence-based intervention techniques based on the individual needs of the child and family (Henggeler 2003), including cognitive-behaviour approaches, parent training and family therapies. We extracted data immediately post-treatment (i.e. immediately after the treatment programme had finished). Where data were available, we also analysed studies at follow-up, which is classed as the first available time point after post-treatment. We categorised outcomes into one of six outcome domains: parenting behaviour, parent mental health, child behaviour/disability, child mental health, child symptoms and family functioning. Where studies had more than one comparator group, we chose the ‘active control group’ over ‘standard treatment’ or ‘wait-list control’ groups.

There are four therapies (CBT, FT, PST and MST), eight conditions (asthma, cancer, diabetes mellitus, gynaecological disorders, inflammatory bowel diseases, painful conditions, skin diseases, and traumatic brain injury), two time points (post-treatment and follow-up) and six possible outcomes (parenting behaviour, parent mental health, child behaviour/disability, child mental health, child symptoms and family functioning). There are six categories by which we analysed data:

For each condition, across all types of psychological therapy, what is the efficacy for the six outcomes immediately post-treatment?

For each condition, across all types of psychological therapy, what is the efficacy for the six outcomes at follow-up?

For each psychological therapy, across all conditions, what is the efficacy for the six outcomes immediately post-treatment?

For each psychological therapy, across all conditions, what is the efficacy for the six outcomes at follow-up?

The interaction between the condition and the psychological therapy efficacy.

Investigation of characteristics of particularly effective treatments.

Analyses are presented for each of the six outcomes, however, due to the heterogeneous nature of the conditions and studies, this was not always possible. We pooled data using the standardised mean difference (SMD) and a random-effect model, as studies did not consistently use the same scales when measuring the same outcomes. Cohen’s d effect sizes can be interpreted as follows: 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large (Cohen 1992).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of studies when data were not reported fully in publications. However, when authors could not send data to the review authors or were non-responsive to emails, we excluded data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When there were multi-arm trials or trials that compared more than one active treatment, we used the primary active treatment and compared with the least biased comparator (active control). Analyses of the following subgroups are presented where data permitted:

Parent-only interventions versus family-based interventions;

Intervention effects within specific illnesses;

Intervention effects across specific types of psychological interventions.

We also explored heterogeneity through subgroup analysis.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies for a detailed description of included and excluded studies.

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Allen 1998 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment, post-treatment, 3 months and 1 year | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 27, 3-month follow-up = 27, 12-month follow-up = 21 Start of treatment n = 27 Sex of children: 11 M, 16 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age of children =12.2 Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Referred by paediatricians and neurologists in the community and recruited by newspaper ad Diagnosis of child = Migraine headache Mean years of illness = 4.4 years |

|

| Interventions | “Thermal Biofeedback plus Parent Pain Behaviour Management” (CBT) “Thermal Biofeedback” Mode of delivery: Individual, face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Authors Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child, hrs) = 6 × 40 minutes = 4 hours Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = not reported |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Pain diary* Coping Assistance Questionnaire Child Perception Abbreviated Acceptability Rating Profile Parent measures Parent Perception of Pain Interference Questionnaire* Coping Assistance Questionnaire for Parents* Abbreviated Acceptability Rating Profile |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This manuscript was supported in part by grant MCJ319152 from the Maternal and Health Bureau, Health Resources Services Administration, and by grant 90 DD 032402” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Randomized, controlled group-outcome design, subjects were assigned to either thermal biofeedback intervention, or the same biofeedback intervention plus pain behavior management guidelines”. Comment: method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Attrition was not adequately described |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data were incompletely reported |

| Ambrosino 2008 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment, 1 month (end of treatment), 3 months, 6 months and 12 months post-intervention | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 81 children, 3-month follow-up = 79 children, 6-month follow-up = 72, 12-month follow-up = 72 Start of treatment n = 87 parents and children received intervention at start Sex of children: 34 M, 53 F Sex of parents: 5 M, 82 F Mean age of children = 9.91 (± 1.44) Mean age of parents = 40.01 (± 5.40) Source = Yale Pediatric Diabetes Program Diagnosis of child = Type 1 diabetes Mean years of illness = 3.71 ± 2.91 years |

|

| Interventions | “Coping Skills Training (CST)” (CBT) “Group Education (GE)” Mode of delivery: Groups, face-to-face, parents met separately Intervention delivered by: Mental health professionals Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child) = 6 × 1½ = 9 hours Duration of intervention (parent) = 6 × 1½ = 9 hours |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Metabolic control* Child Depression Inventory (CDI)* Disease-related variables Issues in Coping with IDDM - Child scale Self-Efficacy for Diabetes Scale Diabetes Quality of Life Scale for Youth (DQOL) Diabetes Family Behavior Scale (DFBS) Parent measures Center for Epidemiologic Depression Scale (CES-D)* Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale (FACES II)* Issues in Coping with IDDM - Parent scale Diabetes Responsibility and Conflict Scale |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This study was supported by grants funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research (National Institute of Health, 1&2R01NR004009)” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Participants were randomised initially by a sealed envelope technique and later by computer to either the coping skills therapy of group eduction.” Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Participants were randomised initially by a sealed envelope technique and later by computer to either the coping skills therapy of group eduction.” Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | “All follow-up data were collected by trained research assistants.” Comment: blinding unclear, probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Data were fully reported on request |

| Antonini 2014 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment, post-treatment = 8.16 months after start of intervention | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 36 Start of treatment n = 40 parents and children received intervention at start Sex of children: Not reported Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age of children = 5.42 (± 2.1) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Hospital Diagnosis of child = TBI Mean years of illness = Not reported |

|

| Interventions | ”Online parenting skills program” “Internet resource comparison” (IRC) Mode of delivery: Home visit, online Intervention delivered by: Therapist with psychology masters degree Training: Given manual and had meetings with an advanced supervising psychologist Duration of intervention (child) = 10 core sessions, 4 supplementary sessions Duration of intervention (parent) = 10 core sessions |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS)* Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL)* Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (ECBI) |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This work was supported by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, Department of Education (grant numbers 133G060167, H133B090010 to SLW)” COI: “The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest” |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “The randomization scheme was generated using SAS by the medical centers Division of Biostatistics and created using permuted block sizes for each of the randomizations. ” Comment: Probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “The randomization scheme was generated using SAS by the medical centers Division of Biostatistics and created using permuted block sizes for each of the randomizations. ” Comment: Probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “Video coders remained naive to condition.” Comment: Probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Attrition reported but no data were presented describing equivalence between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Data were fully reported on request |

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment, post-treatment and at 3 months | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 131 mothers, 3-month follow-up =123 mothers Start of treatment n = 197 mothers Sex of children: 103 M, 94 F Sex of parents: 0 M, 197 F Mean age of child =8.1 Mean age of parents = 36.3 Source = 4 paediatric cancer centres in USA Diagnosis of child = Cancer Mean years of illness = Average 6 weeks since diagnosis, range 2 to 16 weeks from diagnosis |

|

| Interventions | “Problem-Solving Skills Training” (PST) “Problem-Solving Skills Training + Personal Digital Assistant” Mode of delivery: Individual, face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Therapists with graduate training in Clinical Psychology Training: Special training in PSST Duration of intervention (child, hours) = 0 Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = 8 × 1 = 8 hours |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Parent measures Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R)* Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)* Profile of Mood States (POMS) Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) |

|

| Notes | The comparison looks like a non inferiority trial but it was not designed in this way so we have included it despite the lack of a control group Funding: “National Institutes of Health [grants CA 65520, CA 098954, and The University of Texas M. D. Anderson core grant CA 16672 for data management at this institution” COI: “Conflict of interest: None declared” |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Computerized randomisation to one of the three treatment arms was performed at the data management centre.” Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Computerized randomisation to one of the three treatment arms was performed at the data management centre.” Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Attrition was reported, but no data were presented describing equivalence between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Data were fully reported on request |

| Barakat 2010 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed at pre-treatment, post-treatment and 12 months | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 37, 12-month follow-up = 34 Start of treatment n = 42 received session 1 Sex of children: 15 M, 22 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age (SD) of child = 14.17 (1.75) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = “Comprehensive sickle cell centre” Diagnosis of child = Sickle cell disease Mean years of illness = Lifetime |

|

| Interventions | “Pain Management Intervention” (CBT) “Disease Education Intervention” Mode of delivery: Individual families, face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Clinical Psychology doctoral students Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child, hours) = 4 × 90 minutes = 6 hours Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = 4 × 90 minutes = 6 hours |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Pain diary (% days with pain and % interference with activities)* Coping Strategies Questionnaire Family Cohesion Scale* Health-related Hindrance Inventory Health Service Use per Medical Chart Review School Attendance Records |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This research was funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U54 30117 to J.R)” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “A 2-group, randomised treatment design was used.” Comment: method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data were fully reported |

| Barry 1997 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed at pre-treatment, post-treatment and 3 months | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 29, 3-month follow-up = 29 Start of treatment n = 36 Sex of children: 10 M, 19 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age of child =9.4 Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Ads in elementary schools and community health centres, referrals from paediatricians and family physicians Diagnosis of child = Headache Mean years of illness = 2 headaches/month |

|

| Interventions | “Cognitive Behavioural Therapy” (CBT) “Wait-list Control” Mode of delivery: Group, face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Mental health professionals Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child, hours) = 2 × 90 minutes = 3 hours Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = 2 × 90 minutes = 3 hours |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Pain diary* |

|

| Notes | Funding: No funding statement was provided in the manuscript COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Each parent-child pair was initially matched with another pair based on the child’s age, sex and headache pain as indicated by the parents’ ratings of average duration, frequency, and intensity of headaches. Subsequently, one of each of the matched parent-child pairs was randomly assigned to either the treatment condition or the waiting list control condition. ” Comment: method not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Each parent-child pair was initially matched with another pair based on the child’s age, sex and headache pain as indicated by the parents’ ratings of average duration, frequency, and intensity of headaches.” Comment: method of concealment not described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data were not fully reported |

| Celano 2012 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed at pre-treatment, post-treatment and 6 months | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 40, 6-month follow-up = 37 Start of treatment n = 41 Sex of children: 26 M, 15 F Sex of parents: 6M, 35 F Mean age (SD) of child = 10.5 (1.6) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Urban children’s hospital and residential camp for children with asthma Diagnosis of child = Asthma Mean years of illness = More than 1 year |

|

| Interventions | “Home based family intervention” “Enhanced treatment as usual” Mode of delivery: Individual families, face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Trained asthma counsellors, post-doctoral psychology fellow and respiratory therapist Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child, hours) = 4 to 6 sessions, average 78 minutes per session Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = 4 to 6 sessions, average 78 minutes per session |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Family Asthma Management System Scale Metered Dose Inhaler Checklist Cotinine/creatinine ratio Number of school days missed Asthma symptom days* Urgent health care visits Medical records reviewed Parent measures Family Asthma Management System Scale Parenting Stress Index (PSI-SF) Brief Symptoms Inventory (for parent distress)* |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This research was supported by a grant from the National Heart Lung & Blood Institute” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Randomisation....by blocked randomisation within age group (8 to 10 vs. 11 to 13) .” Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “Trained assistants blind to group assignment.” Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Data were fully reported on request |

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed at pre-treatment, post-treatment and 2 months | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 31, 2-month follow-up = 31 Start of treatment n = 37 Sex of children: 19 M, 18 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age (SD) of child = 9.2 (1.7) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Outpatient neurology clinic at a large children’s hospital in Midwestern USA Diagnosis of child = Headache Mean years (SD) of illness = 2 years 3 months (2 years 2 months) |

|

| Interventions | “Headstrong CD ROM” (CBT) “Wait-list Control” Mode of delivery: Computer and phone calls Intervention delivered by: CD ROM Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child, hours) = 4 × 1 hr = 4 hours Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = 1 × 1 hr = 1 hour |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Headache diary* Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment* Parent measures Headache diary Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This research was supported in part by an educational grant from AstraZeneca LP” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Randomly assigned to one of two groups by a research assistant using a uniform random numbers table.” Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Randomly assigned to one of two groups by a research assistant using a uniform random numbers table.” Comment: does not state whether research assistant was blind to concealment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “Study neurologists remained blind to randomisation condition throughout the study. Chance of unblinding were limited because follow-up appointments with the study neurologist were scheduled for 2 months following the initial assessment.” Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Attrition was reported, but no data were presented describing equivalence between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data were fully reported |

| Duarte 2006 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed at 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th session (sessions were monthly) | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 32 children Start of treatment n = 32 children Sex of children: 10 M, 22 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age (SD) of children = 9.15 (2.1) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Pediatric Gastroenterology Reference Service Diagnosis of child = Recurrent abdominal pain Mean years of illness = 25 ± 17.5 months |

|

| Interventions | “Cognitive-behavioural family intervention” (CBT) “Control group” Mode of delivery: face-to-face (group/individual not reported) Intervention delivered by: General health professionals Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child, hours) = 4 × 50 minutes = 3 hours, 20 minutes Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = 4 × 50 minutes = 3 hours, 20 minutes |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Pain diary* Visual analogue scale Pressure Pain Threshold |

|

| Notes | Funding: No funding statement was provided in the manuscript COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Randomly allocated to 2 groups.” Comment: probably done but unclear method |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Attrition was not adequately described |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data were incompletely reported |

| Ellis 2004 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment, 6 months after study entry (end of treatment) | |

| Participants | End of treatment = 25 Start of treatment n = 31 Sex of children: 14 M, 11 F Sex of parents: All female Mean age (SD) of children = 13.6 (1.6) Mean age of parents = 39.1 (7.6) Source = Endocrinology clinic within a tertiary care children’s hospital Diagnosis = Type 1 diabetes Mean years of illness = At least 1 year |

|

| Interventions | “Multisystemic Therapy” (MST) “Standard Care Control” Mode of delivery: Individual families, face-to-face and phone contact Intervention delivered by: mental health professionals Training: Completed 1 week MST training Duration of intervention (child) = Mean 6.5 months, 46 sessions Duration of intervention (parent) = Mean 6.5 months, 46 sessions |

|

| Outcomes | * Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Metabolic control* Twenty-Four Hour Recall Interview Frequency of blood glucose testing from blood glucose meter The Diabetes Management Scale (DMS) Health Service Use per Medical Chart Review Parent measures Satisfaction with treatment The Diabetes Management Scale (DMS) |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This project was supported by Grant #R21DK57212 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Randomisation to treatment or control group was completed immediately after baseline data collection by the project statistician.” Comment: no description provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Randomisation to treatment or control group was completed immediately after baseline data collection by the project statistician.” Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “All data was collected by a trained research assistant who was blind to the adolescent’s treatment status.” Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data were fully reported |

| Ellis 2005 | ||

| Methods | RCT 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment, 7 months after study entry (end of treatment), 12 months after study entry (6-month follow-up) | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 110, 6-month follow-up = 85 Start of treatment n = 127 children and their families Sex of children: 62 M, 65 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age of children = 13.25 (± 1.95) Mean age of parents = 38.8 (± 6.8) Source = Endocrinology clinic within a tertiary care children’s hospital Diagnosis = Type 1 diabetes Mean years of illness = 5.25 (± 4.35) years |

|

| Interventions | “Multisystemic Therapy” (MST) “Standard Care Control” Mode of delivery: Individual families, face-to-face and phone contact Intervention delivered by: Mental health professional Training: 1-week training in MST and diabetes education Duration of intervention (child) = Mean 5.7 months, 48 sessions Duration of intervention (parent) = Mean 5.7 months, 48 sessions |

|

| Outcomes |

*Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures HbA1c Levels* Diabetes Stress Questionnaire* Family Relationship Index (FRI) of the Family Environment Scale (FES)* Frequency of Blood Glucose Testing from blood glucose meter Twenty-Four Hour Recall Interview Health Service Use per Medical Chart Review (hospitalisations, emergency department visits) Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist (DFBC) Diabetes Family Responsibility Questionnaire Parental overestimation of adolescent responsibility score Parent measures Family Relationship Index (FRI) of the Family Environment Scale (FES)* Diabetes Family Behavior Checklist (DFBC) Diabetes Family Responsibility Questionnaire |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This project was supported by grant Ro1 DK59067 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases” COI: “No conflict of interest declared” |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Random assignment to treatment group was completed after baseline data collection.” Comment: no method described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “To ensure equivalence across treatment conditions, random assignment was stratified according to HbA1 c level at the baseline visit.” |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data were incompletely reported |

| Ellis 2012 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed at pre-treatment, 7 month post-treatment, 6 month follow-up | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 117, 6-month follow-up =117 Start of treatment n = 146 Sex of children: 64 M, 82 M Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age (SD) of child = 14.2 (2.3) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Hospital Diagnosis of child = Diabetes Mean years of illness = 4.7 years (3.0) |

|

| Interventions | “Multisystemic therapy” (MST) “Telephone support” Mode of delivery: Home/school/clinic visits Intervention delivered by: 5 masters-level therapists Training: 5-day training, phone consultation with MST expert, follow-up booster Duration of intervention (child, hours) = Minimum 2 meetings per week for 6 mths Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = Minimum 2 meetings per week for 6 mths |

|

| Outcomes |

*Extracted measures used in the analyses Metabolic control* Regimen adherence* |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This project was supported by grant #RO1DK59067 from the National institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney diseases” COI: “Three of the authors are board members of Evidence Based Services, which has a licensing agreement with MST Services, which has a licensing agreement with MST Services, LLC, for dissemination of multisystemic therapy treatment technology. There are no other potential author conflicts of interest” |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to MST or telephone support. Randomization occurred immediately after baseline data collection using a permuted block algorithm to ensure equivalence across treatment condition…” Comment: Probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “The project statistician generated the randomization sequence and participants were notified of their randomization status by the project manager.” Comment: Probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “All measures were collected by a trained research assistant in the participants’ homes. The research assistant was blind to treatment assignment to the extent possible in a behavioural trial.” Comment: Probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Attrition was reported, but no data were presented describing equivalence between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Data were fully reported on request |

| Gulewitsch 2013 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed at pre-treatment, 3 months post-treatment | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 37 Start of treatment n = 38 Sex of children: 14 M, 24 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age of child =9.4 Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Public announcements in local newspapers and at paediatricians’ and community health centres, referrals from paediatricians and family physicians Diagnosis of child = Functional abdominal pain and Irritable bowel syndrome Mean months (SD) of illness = 34.61 (40.7) |

|

| Interventions | “Hypnotherapeutic behavioural treatment” “Wait-list Control group” (WCG) Mode of delivery: Group face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Psychologist Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child, hours) = 2 × 90 minutes = 3 hours Duration of intervention (parent, hours) = 2 × 90 minutes = 3 hours |

|

| Outcomes |

*Extracted measures used in the analyses Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL)* Pain diary Pediatric-pain disability index (P-PDI)* Abdominal pain index (AP) Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) |

|

| Notes | Funding: No funding statement was provided in the manuscript COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Randomly assigned following simple randomization procedures (computerized random number generator) to TG (n=20 or WCG (n=18).” Comment: Probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Attrition was reported, but no data were presented describing equivalence between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data were fully reported |

| Hicks 2006 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment, 1-month follow-up and 3-month follow-up | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 37, 1 -month follow-up = 37, 3-month follow-up =32 Start of treatment n = 47 Sex of children: 17 M, 30 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age (SD) of children = 11.7 (2.1) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Media, posters in physicians offices and advertisements in school newsletters Diagnosis = Recurrent head or abdominal pain Mean years of illness = 3 years |

|

| Interventions | “Online cognitive-behavioral treatment programme” (CBT) “Wait list Control” Mode of delivery: Individual, online web programme, email and phone contact Intervention delivered by: Internet and researcher Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child) = Mean 3 hours on the phone, duration to complete online programme not described Duration of intervention (parent) = Not reported |

|

| Outcomes |

*Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Pain diary* Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Treatment expectation Treatment satisfaction Parent measures Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Treatment expectation Treatment satisfaction |

|

| Notes | Funding: “The first author acknowledges the support received through the Peter Samuelson STARBRIGHT Foundation 2002 Dissertation Award in pediatric psychology and the Canadian Pain Society Small Grant for Local and Regional Initiatives” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “The 47 participants were stratified by age and pain severity and randomly assigned by blocks to either the treatment condition or the standard medical care wait-list condition.” Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “The 47 participants were stratified by age and pain severity and randomly assigned by blocks to either the treatment condition or the standard medical care wait-list condition.” Comment: no method of concealment described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data were incompletely reported |

| Hoekstra-Weebers 1998 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Pre-treatment (at diagnosis), post-treatment, 6-month follow-up | |

| Participants | End of treatment and 6-month follow-up n = 81 parents, 41 children Start of treatment n = 120 parents, 61 children Sex of parents: 40 M, 41 F Sex of children: 23 M, 18 F Mean age (SD) of parents = 36.6 (5.4) Mean age (SD) of children = 6.4 (4.7) Source = Paediatric oncology clinic Diagnosis = Cancer Mean years of illness = 2 to 21 days post diagnosis |

|

| Interventions | “Psychoeducational and Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention” (CBT) “Standard Care Control” Mode of delivery: Individual, face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Master’s student in Psychology Training: Not reported Duration of intervention (child) = 0 Duration of intervention (parent) = 8 × 90 minutes =12 hours |

|

| Outcomes |

*Extracted measures used in the analyses Parent measures Symptom Check List (SCL)* State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State* Goldberg General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) Social Support List-Discrepancies (SSL-D) Intensity of emotions questionnaire designed by the authors |

|

| Notes | Funding: “This study has been funded by the Dutch Cancer Society and the Pediatric Oncology Foundation Groningen” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Parents were randomly assigned…. parents drew one of two envelopes in which a letter indicated in which group they were placed. ” Comment: method unclear |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “Parents were randomly assigned…. parents drew one of two envelopes in which a letter indicated in which group they were placed.” Comment: probably done but unsure whether envelopes were sealed or numbered |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | No description found in text. Comment: probably not done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data were fully reported |

| Kashikar-Zuck 2005 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment and post-treatment | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 27 Start of treatment n = 30 Sex of children: 0 M, 30 F Sex of parents: 3 M, 27 F Mean age of children = 15.83 (1.26) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = paediatric rheumatology clinic, Midwestern USA Diagnosis = Fibromyalgia syndrome Mean years of illness = Over 2 years |

|

| Interventions | “Cognitive Skills Training” (CBT) “Self Monitoring” Mode of delivery: Individual, face-to-face plus phone contact Intervention delivered by: Doctoral level paediatric psychology intern or psychology fellow Training: Trained by principal investigator Duration of intervention (child) = 6 sessions, hours not reported Duration of intervention (parent) = 3 sessions, hours not reported |

|

| Outcomes |

*Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Children’s Depression Inventory* (CDI) Functional Disability Inventory* (FDI) Visual analogue scale (VAS) Pain Coping Questionnaire (PCQ) Tender point examination |

|

| Notes | Funding: “Supported by grants from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation and National Institutes of Health Grant 1P60AR47784-0” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “A computer generated pseudo-random number list was used. A simple randomisation technique was used with a 1:1 allocation ratio for 30 subjects as a single block. ” Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “…a research assistant who was blind to the objectives of the study enrolled the subject and opened a sealed envelope with the subject’s study identification number.” Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “A research assistant who was blind to the study objectives and to the subjects’ treatment assignment administered the self-report measures. The rheumatologist or occupational therapist who conducted the tender point assessments was blind to the subjects’ treatment assignment.” Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Attrition was reported, but no data were presented describing equivalence between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data were fully reported |

| Kashikar-Zuck 2012 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment, post-treatment, 6-month follow-up | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 106, follow-up n = 100 Start of treatment n = 114 Sex of children: 9 M, 105 F Sex of parents: Not reported Mean age (SD) of children = 15.0 (1.8) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = 4 paediatric rheumatology centres, Midwestern USA Diagnosis = Fibromyalgia syndrome Mean years (SD) of illness = 2 years, 10 months (2 years, 6 months) |

|

| Interventions | “Cognitive behavioural therapy” (CBT) “Fibromyalgia education” Mode of delivery: Individual, face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Therapists with postdoctoral training in paediatric psychology Training: 6- to 8-hour training by principal investigator Duration of intervention (child) = 6 hours Duration of intervention (parent) = 2 hours, 15 minutes |

|

| Outcomes |

*Extracted measures used in the analyses Child measures Child Depression Inventory* (CDI) Functional Disability Inventory* (FDI) Visual analogue scale* (VAS) Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) |

|

| Notes | Funding: “Supported by grants from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation and National Institutes of Health Grant 1P60AR47784-0” COI: No conflict of interest statement included in the manuscript |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Eligible patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 2 treatment arms based upon a computer-generated randomisation list. Randomisation was stratified by site.” Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “When a patient was enrolled, the study therapist contacted the biostatistician to obtain the subject identification number and treatment allocation.” Comment: probably done |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “The principle investigator, study physicians, study coordinator, and assessment staff were all blinded to the patients’ treatment condition throughout the trial. Patients were asked not to divulge what treatment they were receiving to the study physician.” Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | Attrition was reported, there were no significant differences between completers and non-completers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data were fully reported |

| Kazak 2004 | ||

| Methods | RCT. 2 arms. Assessed pre-treatment and 3 to 5 months post-treatment | |

| Participants | End of treatment n = 116 children Start of treatment n = 150 children Sex of children: 73 M, 77 F Sex of parents: 106 M, 146 F Mean age (SD) of children = 14.61 (2.4) Mean age of parents = Not reported Source = Oncology tumour registry at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Diagnosis = Childhood cancer survivor Mean years (SD) of illness = 5.30 (2.92) years post-treatment |

|

| Interventions | “Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program SCCIP” (CBT) “Wait-list Control” Mode of delivery: Group, face-to-face Intervention delivered by: Nurses, social workers, psychologists, graduate and post-doctoral psychology trainees Training: 12 hours Duration of intervention (child) = 5 hours direct, 2 hours informal Duration of intervention (parent) = 5 hours direct, 2 hours informal |

|

| Outcomes |