Abstract

Introduction

While overweight and obesity in children and adolescents is a major global health problem, the effects of exercise on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents are not well established despite numerous studies on this topic. The purpose of this study is to use the network meta-analytic approach to determine the effects of exercise (aerobic, strength training or both) on body mass index (BMI) z-score in overweight and obese children and adolescents.

Methods and analysis

Randomised exercise intervention trials >4 weeks, published in any language between 1 January 1990 and 31 September 2015, and which include direct and/or indirect evidence, will be included. Studies will be retrieved by searching 6 electronic databases, cross-referencing and expert review. Dual abstraction of data will occur. The primary outcome will be changes in BMI z-score while the secondary outcome will be changes in body weight in kilograms (kg). Risk of bias will be assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment instrument while confidence in the cumulative evidence will be assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) instrument for network meta-analysis. Network meta-analysis will be performed using multivariate random-effects meta-regression models. The surface under the cumulative ranking curve will be used to provide a hierarchy of exercise treatments (aerobic, strength training or both).

Dissemination

The results of this study will be presented at a professional conference and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

CRD42015026377.

Keywords: exercise, meta-analysis, systematic review, children, obesity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review with network meta-analysis to examine which exercise intervention is best (aerobic exercise, strength training or both) for improving body mass index z-score in overweight and obese children and adolescents.

The results of this systematic review with network meta-analysis will be useful to practitioners for making informed decisions about exercise in the treatment of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents as well as provide researchers with direction for the conduct and reporting of future research on this topic.

Common to most meta-analyses, the results may yield significant heterogeneity which cannot be explained.

Introduction

Rationale

Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents is a major global health problem. Ng et al1 reported that between the years 1980 and 2013, the worldwide prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents from developed countries has increased from 16.9% to 23.8% in boys and from 16.2% to 22.6% in girls, while in developing countries estimated increases of 8.1–12.9% (boys) and 8.4–13.4% (girls) were reported. Between the years 1971–1974 and 2011–2012, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the USA has increased from 15.6% to 32.1% among boys and 15.2% to 31.7% in girls.2 Not surprisingly, the estimated costs associated with childhood obesity are high. Finkelstein et al3 estimated that the incremental lifetime medical costs of an obese child aged 10 years in the USA were $19 000 greater when compared with a normal weight child of the same age. Accounting for the number of obese 10-year-olds in the USA, the lifetime medical costs for this age alone was estimated to be approximately $14 billion.3

Based on previous research, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that the deleterious effects of overweight and obesity during childhood and adolescence are both immediate and long term.4 Specifically, obese children and adolescents are more likely to have risk factors for cardiovascular disease (high cholesterol, high blood pressure, etc), with approximately 70% possessing at least one risk factor.5 In addition, obese adolescents are more likely to have prediabetes.6 Obese children and adolescents have also been shown to be at a greater risk for bone and joint difficulties, sleep apnoea, and social and psychological issues (stigmatisation, poor self-esteem, etc).7 8 From a long-term perspective, obesity in children and adolescents has been shown to track into adulthood.9 10 11 12 As a result, this places them at a greater risk for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, several types of cancer and osteoarthritis during adulthood.4

While one previous systematic review with meta-analysis reported statistically significant improvements in adiposity as a result of strength training in overweight and obese children and adolescents,13 others that have focused on the effects of exercise as an independent intervention on adiposity as a primary outcome in male and female children and adolescents have reported a non-significant change in adiposity.14 15 16 17 18 However, all six suffer from one or more of the following potential limitations: (1) inclusion of a small number of studies with exercise as the only intervention,14–16 (2) inclusion of non-randomised trials,13 15 (3) inclusion of children and adolescents who were not overweight or obese,15 17 18 (4) reliance on pairwise versus network meta-analysis that incorporates both direct and indirect evidence,13–18 and (5) absence of an established hierarchy for determining which types of exercise (aerobic, strength training or both) might be best for improving adiposity.13–18

The investigative team has previously published meta-analytic research examining the effects of exercise (aerobic, strength training or both) on body mass index (BMI) z-score19 and BMI20 in overweight and obese children and adolescents. For both meta-analyses, statistically significant and practically important reductions of 3–4% were observed.19 20 While these results are encouraging, especially at the population level, they were limited to indirect comparisons that focused on the pooled results of different types of exercise (aerobic, strength training or both) in pairwise meta-analyses.19 20 Network meta-analysis ‘is a meta-analysis in which multiple treatments (that is, three or more) are compared using both direct comparisons of interventions within randomized controlled trials and indirect comparisons across trials based on a common comparator’.21 In addition, a major strength of network meta-analysis is the ability to provide a single ranking of treatments, for example, aerobic, strength training or both, with respect to their effects on the outcome(s) of interest. This is important because practitioners and policymakers want to know which treatments work best and for whom.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, no previous network meta-analysis has examined the effects of aerobic, strength training or combined aerobic and strength training on BMI z-score in either overweight and obese children and adolescents as well as adults. The investigative team is aware of one previous network meta-analysis that examined the effects of exercise and/or diet on body weight, waist circumference, fat mass and waist-to-hip ratio in overweight and obese adults 19 years of age and older.22 When compared with diet only, diet plus exercise resulted in greater reductions in body weight and fat mass, while diet plus exercise, when compared with exercise only, resulted in significant changes in body weight, waist circumference and fat mass.22 When exercise was compared with diet only, the diet-only groups yielded greater reductions in body weight and fat mass.22 Neither BMI nor BMI z-score was included as outcomes.22

Objective

The primary objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review with network meta-analysis of randomised trials to determine the effects of exercise (aerobic, strength training or both) on BMI z-score in overweight and obese children and adolescents.

Methods

Overview

This study will follow the guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) extension statement for network meta-analyses of healthcare interventions.23

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this network meta-analysis will be as follows: (1) direct evidence from randomised trials that compare two or more exercise interventions (aerobic, strength training or both) or indirect evidence from randomised controlled trials that compare an exercise intervention group to a comparative control group (non-intervention, attention control, usual care, wait-list control, placebo); (2) exercise interventions ≥4 weeks; (3) male and/or female children and adolescents 2–18 years of age; (4) participants overweight or obese, as defined by the original study authors; (5) studies published in any language; (6) published and unpublished studies (dissertations and Master's theses) between 1 January 1990 and September 2015 and (7) data available or calculable for BMI z-score. For the purposes of this study, exercise, aerobic exercise and strength training will be defined according to the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.24 Specifically, exercise will be defined as movement that is ‘planned, structured, and repetitive and purposive in the sense that the improvement or maintenance of one or more components of physical fitness is the objective,’24 25 aerobic exercise as ‘exercise that primarily uses the aerobic energy-producing systems, can improve the capacity and efficiency of these systems, and is effective for improving cardiorespiratory endurance,’24 and strength training as ‘exercise training primarily designed to increase skeletal muscle strength, power, endurance, and mass’.24 Studies will be limited to randomised trials because it is the only way to control for confounders that are not known or measured as well as the observation that non-randomised controlled trials tend to overestimate the effects of healthcare interventions.26 27 Intervention groups that include both exercise and diet performed concurrently will not be included unless there is a diet-only group. Four weeks was chosen as the lower cut point for intervention length based on previous research demonstrating improvements in adiposity over this time period in girls aged 11 years.28 Participants will be limited to overweight and obese children and adolescents, as defined by the original study authors, because it has been shown that this population is at an increased risk for premature morbidity and mortality throughout their lifetime.29 Studies that take place in any setting will be included. Based on our preliminary searching, the first studies that meet our inclusion criteria were published in 2004.30–33 However, to ensure that we do not miss any potentially eligible studies, we will search back starting with 1990 vs 2004. Our rationale for this approach is based on the assumption that no eligible studies will have been published prior to 1990.

Information sources

From a previous and broad database of studies addressing the effects of exercise on measures of adiposity in overweight and obese children and adolescents published between 1990 and 2012, a search for studies that meet the aforementioned eligibility criteria will be conducted. In addition, updated searches of the following six databases will be conducted for studies in any language that were published between 1 January 2012 and September 2015: (1) PubMed, (2) Scopus, (3) Web of Science, (4) Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, (5) CINAHL and (6) Sport Discus. Furthermore, cross-referencing from retrieved studies and reviews will be conducted. Finally, the consultant, an expert on exercise and obesity in children and adolescents, will review the reference list for completeness (Dr Russell Pate, personal written and signed commitment, 13 August 2015).

Search strategy

Search strategies will be developed using text words as well as medical subject headings (MeSH) associated with the effects of exercise on adiposity in overweight and obese children and adolescents. Studies in languages other than English will be translated using the freely available Google translate and Babblefish. The second author (KSK) will conduct all electronic database searches. A copy of a preliminary search strategy using PubMed, including limits, can be found in online supplementary file 1. This search strategy will be adapted for other database searches.

bmjopen-2016-011258supp.pdf (486.3KB, pdf)

Study records

Study selection

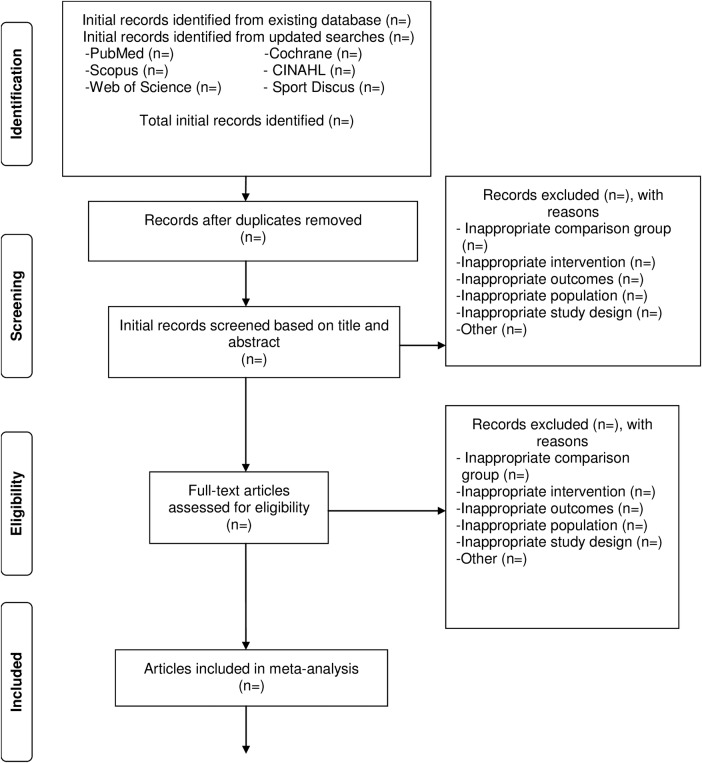

All studies to be screened will be imported into Reference Manager (V.12)34 and duplicates removed both electronically and manually by the second author (KSK). A copy of the database will then be provided to the first author for duplicate screening. The first two authors will select all studies, independent of each other. The full report for each article will be obtained for all titles and abstracts that appear to meet the inclusion criteria or where there is any uncertainty. Multiple reports of the same study will be handled by including the most recently published article as well as drawing from previous reports, assuming similar methods and sample sizes. Neither of the screeners will be blinded to the journal titles or to the study authors or institutions. Reasons for exclusion will be coded as one or more of the following: (1) inappropriate population, (2) inappropriate intervention, (3) inappropriate comparison(s), (4) inappropriate outcome(s), (5) inappropriate study design and (6) other. On completion, both authors will meet and review their selections. Discrepancies will be resolved by consensus. If consensus cannot be reached, the consultant will provide a recommendation (Dr Russell Pate, personal written and signed commitment, 13 August 2015). The overall agreement rate prior to correcting discrepant items will be calculated using Cohen's κ statistic.35 After identifying the final number of studies to be included, the overall precision of the searches will be calculated by dividing the number of studies included by the total number of studies screened after removing duplicates.36 The number needed-to-read will then be calculated as the inverse of the precision.36 A flow diagram that depicts the search process will be included as well as an online supplementary material file that includes a reference list of all studies excluded, including the reason(s) for exclusion. The proposed structure for the flow diagram is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed flow diagram to depict the search process.

Data abstraction

Prior to the abstraction of data, a codebook that can hold more than 200 items per study will be developed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, Washington: Microsoft Corporation, 2010). The codebook will be developed by the first two authors with input from the consultant (Dr Russell Pate, personal written and signed commitment, 13 August 2015). The major categories of variables to be coded include (1) study characteristics (author, journal, year, etc); (2) participant characteristics (age, height, etc.); and (3) outcome characteristics for BMI z-score and body weight (sample sizes, baseline and postexercise means and SDs, etc). The first two authors will abstract the data from all studies, independent of each other, using separate codebooks in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Excel, 2010). On completion of coding, the codebooks will be merged into one primary codebook for review. Both authors will then meet and review all selections for agreement. Discrepancies will be resolved by consensus. If consensus cannot be reached, the consultant will provide a recommendation (Dr Russell Pate, personal written and signed commitment, 13 August 2015). Prior to correcting disagreements, the overall agreement rate will be calculated using Cohen's κ statistic.35

Outcomes and prioritisation

The primary outcome in this study will be changes in BMI z-score, while the secondary outcome will be changes in body weight in kilograms (kg).

Risk of bias assessment in individual studies

Risk of bias will be assessed at the study level using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment instrument,37 with a focus on the primary outcome of interest, changes in BMI z-score. Bias will be assessed across six domains: (1) random sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of participants and personnel, (4) blinding of outcome assessment, (5) incomplete outcome data, (6) selective reporting and (7) whether or not participants were exercising regularly, as defined by the original study authors, prior to taking part in the study. Each item is classified as having either a high, low or unclear risk of bias. In addition, we will provide a text description of the basis for our judgement in each of the seven domains. For example, for a study rated as being at an unclear risk of bias for the category of whether or not participants were exercising regularly, we may provide a text description such as ‘not enough information provided to make a decision’. Assessment for risk of bias will be limited to the primary outcome of interest, changes in BMI z-score. Since it's impossible to blind participants to group assignment in exercise intervention protocols, all studies will be classified as at a high risk of bias with respect to the category ‘blinding of participants and personnel’. Based on previous research, no study will be excluded based on the results of the risk of bias assessment.38 All assessments will be conducted following the same procedures as for the abstraction of data.

Data synthesis

Calculation of effect sizes

The primary outcome for this study will be changes in BMI z-score, while the secondary outcome will be changes in body weight. For indirect comparisons, changes will be calculated by subtracting the change outcome difference in the exercise group minus the change outcome difference in the control group. Variances will be calculated from the pooled SDs of change scores in the exercise and control groups. If change score SDs are not available, these will be calculated from either (1) 95% CIs for change outcome or treatment effect differences, (2) pre-SD and post-SD values according to procedures developed by Follmann et al39 or (3) data for BMI in kg/m2. However, before trying to estimate BMI z-score from BMI in kg/m2, we will try and retrieve complete BMI z-score data from investigators. For direct comparisons, that is, randomised trials with no control group, the same general procedures will be followed except that the control group data will be replaced with one of the exercise interventions as follows: (1) aerobic minus strength training, (2) aerobic training minus aerobic and strength training combined and (3) strength training minus aerobic and strength training combined. Ninety-five per cent CI and z-α values will be calculated for each outcome from each study. If a study includes both direct and indirect comparisons, only direct comparison data will be included given that a primary focus of the current study is determining which exercise interventions(s) might work best for improving BMI z-score in children and adolescents. For studies in which BMI z-score and changes in body weight are assessed at multiple intervention time points, for example, 0, 4 and 8 weeks, we will use the data from the initial and last assessment. If sufficient data are available, we will also analyse results from the follow-up period in order to determine the sustainability of reductions in BMI z-score related to the various exercise modalities. While few if any cross-over trials are expected, treatment effects will be calculated for these trials by using all assessments from the intervention and control periods and analysing them as if they were a parallel group trial of the intervention versus control group.40 While this might create a unit-of-analysis error, this is a conservative approach in which studies may result in being underweighted versus overweighted.40 Given the primary outcomes and expected distribution of findings, this approach is believed to be superior to alternative approaches such as only including data from the first assessment period or attempting to impute SDs.40

Pooled estimates for changes in outcomes

Separate network (geometry) plots for each outcome will be used to provide a visual representation of the evidence base with nodes (circles) weighted by the number of participants randomised to each treatment and edges (lines) weighted by the number of studies evaluating each pair of treatments.41 42 Contribution plots for each outcome will be used to determine the most dominant comparisons for each network estimate as well as for the entire network.41 The weights applied will be a function of the variance of the direct treatment effect and the network structure, the result being a per cent contribution of each direct comparison to each network estimate.41

Network meta-analysis will be performed using a recently described multivariate random-effects metaregression model43 44 that can be performed within a frequentist setting, allows for the inclusion of potential covariates, and correctly accounts for the correlations from multiarm trials.45 The frequentist approach was chosen over alternative Bayesian models because it avoids sensitivity to priors and Monte Carlo error.43 Non-overlapping 95% CIs will be considered to represent statistically significant changes. Separate network meta-analysis models will be used to examine for changes in BMI z-score and body weight.

Transitivity, that is, similarity in the distribution of potential effect modifiers across the different pairwise comparisons for each outcome,46 will be assessed using random-effects network meta-regression analyses. Potential effect modifiers will include age, gender, baseline BMI z-score, baseline body weight and length of training, in weeks. In addition, sensitivity analysis will be conducted according to whether the study was published or unpublished.

Inconsistency, that is, differences between direct and indirect effect estimates for the same comparison,47 48 will be examined using the recently updated mvmeta command for multivariate random-effects meta-regression in STATA.45 While inconsistency tests will be applied, recent research has shown that inconsistency was detected in only 2–14% of tested loops, depending on the effect measure and heterogeneity estimation method.49 50

Prediction intervals will be used to enhance interpretation of results with respect to the magnitude of heterogeneity as well as provide an estimate of expected results in a future study.51

52 These will be computed as  , where

, where  is the average weighted estimate across studies,

is the average weighted estimate across studies,  is the 100(1-α/2) percentile of the t-distribution degrees of freedom,

is the 100(1-α/2) percentile of the t-distribution degrees of freedom,  is the estimated squared SE of

is the estimated squared SE of  and

and  is the estimated between-study variance. For network meta-analysis, degrees of freedom (df) will be set to the number of studies minus the number of comparisons minus 1.53

is the estimated between-study variance. For network meta-analysis, degrees of freedom (df) will be set to the number of studies minus the number of comparisons minus 1.53

Ranking analysis, a major advantage of network meta-analysis, is the ability to rank all interventions for the outcome under study. For this proposed project, ranking plots for a single outcome using probabilities will be used.41 54 However, since ranking of treatments based solely on the probability of each treatment being the best should be avoided because it does not account for the uncertainty in the relative treatment effects as well as the potential for assigning higher ranks for treatments in which little evidence is available, separate rankograms and cumulative ranking probability plots will be used to present ranking probabilities along with their uncertainty for changes in BMI z-score and body weight.41 54 A rankogram for a specific treatment y is a plot of the probabilities of assuming each of the T ranks where T is the total number of treatments in the network.41 54 The cumulative rankograms display the probabilities that a treatment would be among the n best treatments, where n ranges from one to T.41 54 The surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA), a transformation of the mean rank, provides a hierarchy of treatments and accounts for the location and variance of all treatment effects.41 54 Larger SUCRA values are indicative of better ranks for the treatment.41 54 Separate ranking analyses for BMI z-score and body weight will be conducted using the SUCRA and mvmeta commands in STATA. Interpretation of these rankings will be conducted within the context of absolute and relative treatment effects.42

Meta-biases

Small-study effects (publication bias, etc) will be assessed using comparison-adjusted funnel plots.41 Unlike traditional funnel plots in pairwise meta-analysis, funnel plots in network meta-analysis need to account for the fact that studies estimate treatment effects for different comparisons. Consequently, there is no single reference line from which symmetry can be evaluated. For the comparison-adjusted funnel plot, the horizontal axis will represent the difference between study-specific effect sizes from the comparison-specific summary effect. In the absence of small-study effects, the comparison-adjusted funnel plot should be symmetric around the zero line. Since the treatments need to be organised in some meaningful way to examine how small studies may differ from large ones, comparisons will be defined so that all refer to an active treatment versus a control group.

All data will be analysed using Stata (V.14.1; Stata/SE for Windows, version 14.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation LP; 2015), Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Excel, 2010) and two add-ins for Excel, SSC-Stat (V.2.18; SSC-Stat, version 3.0. University of Reading, United Kingdom: Statistical Services Center; 2007), and EZ-Analyze (V.3.0; EZ Analyze, version 3.0. TA Poynton; 2007).

Confidence in cumulative evidence

Strength of the body of evidence will be assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) instrument for network meta-analysis.55 This includes evaluating the confidence in a specific pairwise effect estimate in a network meta-analysis (study limitations, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) as well as evaluating the confidence in treatment ranking estimates in network meta-analysis (study limitations, indirectness, inconsistency).55 Assessments will be conducted following the same procedures as for the abstraction of data and risk of bias for individual studies.

Dissemination

The results of this study will be presented at a professional conference and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Footnotes

Contributors: GAK is the guarantor. GAK and KSK drafted the manuscript. Both authors contributed to (1) the development of the data sources to search for relevant literature, including search strategy, (2) selection criteria, (3) data abstraction criteria and (4) risk of bias assessment strategy. GAK provided statistical and content expertise on exercise and adiposity in overweight and obese children and adolescents. Both authors read, provided feedback and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This systematic review with network meta-analysis is funded by the West Virginia University Health Sciences Center's Office of Research and Graduate Education (GAK, principal investigator). GAK is also partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U54GM104942.

Disclaimer: The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of West Virginia University or the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: On completion of this project, all data will be available to anyone who requests such by contacting the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M et al. . Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:766–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents: United States, 1963–1965 through 2011–2012. Health E-Stat, 1-6. 2014. National Center for Health Statistics. 12-2-2015.

- 3.Finkelstein EA, Graham WCK, Malhotra R. Lifetime direct medical costs of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2014;133:854–62. 10.1542/peds.2014-0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood obesity facts. 8-27-2015. Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 12-3-2015.

- 5.Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR et al. . Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr 2007;150:12–17. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G et al. . Prevalence of pre-diabetes and its association with clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors and hyperinsulinemia among U.S. adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. Diabetes Care 2009;32:342–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels SR, Arnett DK, Eckel RH et al. . Overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation 2005;111:1999–2012. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161369.71722.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietz WH. Overweight in childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med 2004;350:855–7. 10.1056/NEJMp048008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo SS, Chumlea WC. Tracking of body mass index in children in relation to overweight in adulthood. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;70:145S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK et al. . The relation of childhood BMI to adult adiposity: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 2005;115:22–7. 10.1542/peds.2004-0220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman DS, Wang J, Thornton JC et al. . Classification of body fatness by body mass index-for-age categories among children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:805–11. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Dietz WH et al. . Relationship of childhood obesity to coronary heart disease risk factors in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics 2001;108:712–18. 10.1542/peds.108.3.712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schranz N, Tomkinson G, Olds T. What is the effect of resistance training on the strength, body composition and psychosocial status of overweight and obese children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2013;43:893–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atlantis E, Barnes EH, Singh MA. Efficacy of exercise for treating overweight in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1027–40. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris KC, Kuramoto LK, Schulzer M et al. . Effect of school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index in children: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2009;180:719–26. 10.1503/cmaj.080966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGovern L, Johnson JN, Paulo R et al. . Treatment of pediatric obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4600–5. 10.1210/jc.2006-2409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cesa CC, Sbruzzi G, Ribeiro RA et al. . Physical activity and cardiovascular risk factors in children: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Prev Med 2014;69:54–62. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerra PH, Nobre MR, da Silveira JA et al. . The effect of school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68:1263–73. 10.6061/clinics/2013(09)14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Pate RR. Effects of exercise on BMI z-score in overweight and obese children and adolescents: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:225 10.1186/1471-2431-14-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Pate RR. Exercise and BMI in overweight and obese children and adolescents: a systematic review with trial sequential meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:704539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T, Puhan MA, Vedula SS et al. . Network meta-analysis-highly attractive but more methodological research is needed. BMC Med 2011;9:79 10.1186/1741-7015-9-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwingshackl L, Dias S, Hoffmann G. Impact of long-term lifestyle programmes on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight/obese participants: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2014;3:130 10.1186/2046-4053-3-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM et al. . The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Report. Washington DC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 1985;100:126–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sacks HS, Chalmers TC, Smith H. Randomized versus historical controls for clinical trials. Am J Med 1982;72:233–40. 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90815-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes R et al. . Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408–12. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520290060030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jago R, Jonker ML, Missaghian M et al. . Effect of 4 weeks of Pilates on the body composition of young girls. Prev Med 2006;42:177–80. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics 1998;101(3 Pt 2):518–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watts K, Beye P, Siafarikas A et al. . Exercise training normalizes vascular dysfunction and improves central adiposity in obese adolescents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1823–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watts K, Beye P, Siafarikas A et al. . Effects of exercise training on vascular function in obese children. J Pediatr 2004;144:620–5. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly AS, Wetzsteon RJ, Kaiser DR et al. . Inflammation, insulin, and endothelial function in overweight children and adolescents: the role of exercise. J Pediatr 2004;145:731–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly AS. The effects of aerobic exercise training on vascular structure and function in obese children. DAI 2004;65:185. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reference Manager, Philadelphia, PA: Thompson ResearchSoft, 2009.

- 35.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968;70:213–20. 10.1037/h0026256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee E, Dobbins M, DeCorby K et al. . An optimal search filter for retrieving systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:51 10.1186/1471-2288-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC et al. . The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahn S, Becker BJ. Incorporating quality scores in meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat 2011;36:555–85. 10.3102/1076998610393968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Follmann D, Elliot P, Suh I et al. . Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:769–73. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90054-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaimani A, Higgins JPT, Mavridis D et al. . Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e76654 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catala-Lopez F, Tobias A, Cameron C et al. . Network meta-analysis for comparing treatment effects of multiple interventions: an introduction. Rheumatol Int 2014;34:1489–96. 10.1007/s00296-014-2994-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White IR, Barrett JK, Jackson D et al. . Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: model estimation using multivariate meta-regression. Res Syn Meth 2012;3:111–25. 10.1002/jrsm.1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JPT, Jackson D, Barrett JK et al. . Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res Syn Meth 2012;3:98–110. 10.1002/jrsm.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White IR. Multivariate random-effects meta-regression: updates to mvmeta. Stata J 2011;11:255–70. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jansen JP, Naci H. Is network meta-analysis as valid as standard pairwise meta-analysis? It all depends on the distribution of effect modifiers. BMC Med 2013;11:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donegan S, Williamson P, D'Alessandro U et al. . Assessing key assumptions of network meta-analysis: a review of methods. Res Syn Meth 2013;4:291–323. 10.1002/jrsm.1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu GB, Ades AE. Assessing evidence inconsistency in mixed treatment comparisons. J Am Stat Assoc 2006;101:447–59. 10.1198/016214505000001302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veroniki AA, Vasiliadis HS, Higgins JP et al. . Evaluation of inconsistency in networks of interventions. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:332–45. 10.1093/ije/dys222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song F, Xiong T, Parekh-Bhurke S et al. . Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons of competing interventions: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2011;343:d4909 10.1136/bmj.d4909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A 2009;172:137–59. 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Impact of progressive resistance training on lipids and lipoproteins in adults: another look at a meta-analysis using prediction intervals. Prev Med 2009;49:473–5. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cooper HC, Hedges LV, Valentine JF. The handbook of research synthesis. New York, New York: Russell Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:163–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salanti G, Del Giovane C, Chaimani A et al. . Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e99682 10.1371/journal.pone.0099682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011258supp.pdf (486.3KB, pdf)