Abstract

The Arabidopsis immune receptor FLS2 perceives bacterial flagellin epitope flg22 to activate defenses through the central cytoplasmic kinase BIK1. The heterotrimeric G proteins composed of the non-canonical Gα protein XLG2, the Gβ protein AGB1, and the Gγ proteins AGG1 and AGG2 are required for FLS2-mediated immune responses through an unknown mechanism. Here we show that in the pre-activation state, XLG2 directly interacts with FLS2 and BIK1, and it functions together with AGB1 and AGG1/2 to attenuate proteasome-mediated degradation of BIK1, allowing optimum immune activation. Following the activation by flg22, XLG2 dissociates from AGB1 and is phosphorylated by BIK1 in the N terminus. The phosphorylated XLG2 enhances the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) likely by modulating the NADPH oxidase RbohD. The study demonstrates that the G proteins are directly coupled to the FLS2 receptor complex and regulate immune signaling through both pre-activation and post-activation mechanisms.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.13568.001

Research Organism: <i>A. thaliana</i>

eLife digest

Living cells need to be able to detect changes in their environment and respond accordingly. This ability involves signals from outside of the cell triggering changes to the activity inside the cell. Heterotrimeric G proteins are important for this kind of signaling in a wide range of organisms. In animals and fungi, these proteins directly work with a specific class of receptor proteins called G protein-coupled receptors (or GPCRs for short). Plants also have heterotrimeric G proteins, but it remains unclear whether they similiarly work with GPCRs.

Plants detect invading microbes by using receptors that are completely different from GPCRs. For example, a receptor called FLS2 from the model plant Arabidopsis senses a telltale protein produced by bacteria, and then passes the signal to another protein called BIK1 to activate the plant’s defenses. Heterotrimeric G proteins are required for this process, but the underlying mechanisms remain unknown.

Liang, Ding et al. now show that heterotrimeric G proteins regulate FLS2-controlled defenses by directly interacting with FLS2 and BIK1. Heterotrimeric G proteins also enhance defenses in at least two different ways. Firstly, in the absence of an infection, heterotrimeric G proteins stabilize the BIK1 protein to ensure that it is ready to respond. Secondly, if FLS2 does detect the telltale bacterial protein, BIK1 marks one of the heterotrimeric G proteins with a phosphate group. This then allows the G protein to boost the activity of another plant enzyme that is vital for defense signaling.

In the future, it will be important to work out how activation of FLS2 leads to the activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. Furthermore, heterotrimeric G proteins are likely to regulate additional plant proteins when defenses are activated, and further studies are needed to identify these proteins.

Introduction

As an intensely studied Pattern Recognition Receptor (PRR) in plants, FLS2 serves as an excellent model understanding plant innate immune signaling and receptor kinases in general (Macho and Zipfel, 2014). It forms a dynamic complex with the co-receptor BAK1 and the receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase BIK1 to perceive a conserved bacterial flagellar epitope, flg22, to activate a variety of defense responses (Chinchilla et al., 2007; Heese et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2013). Stability of FLS2 and BIK1 is subject to regulation by ubiquitin-proteasome system and a calcium-dependent protein kinase (Lu et al., 2011; Monaghan et al., 2014). We and others previously showed that BIK1 directly phosphorylates the NADPH oxidase RbohD to prime flg22-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS; Kadota et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014).

Heterotrimeric G proteins are central for signaling in animals (McCudden et al., 2005; Oldham et al., 2008), which contain hundreds of G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). In the pre-activation state, the GDP-bound Gα interacts with the Gβγ dimer to form a heterotrimer. Upon activation by GPCR, Gα exchanges GDP for GTP, resulting in the activation of the heterotrimer. The activated Gα and Gβγ dissociate from each other to regulate downstream effectors. Plants contain canonical Gα (encoded by GPA1 in Arabidopsis), Gβ (encoded by AGB1 in Arabidopsis), Gγ proteins (encoded by AGG1, AGG2), and a non-canonical Gγ (encoded by AGG3 in Arabidopsis) (Urano and Jones, 2013). Plants additionally encode extra-large G proteins (XLGs, encoded by XLG1, XLG2, and XLG3 in Arabidopsis) that carry a variable N-terminal domain and a C-terminal Gα domain (Lee and Assman, 1999; Ding et al., 2008). Recent advances indicate that the Arabidopsis XLGs are functional Gα proteins and interact with Gβγ dimers to form heterotrimers (Zhu et al., 2009; Maruta et al., 2015; Chakravorty et al., 2015). Heterotrimeric G proteins play important roles in a variety of biological processes in plants, including cell division (Ullah et al., 2001, 2003; Chen et al., 2003), meristem maintenance (Bommert et al., 2013), root morphogenesis (Ding et al., 2008), seed development and germination (Chen et al., 2006; Pandey et al., 2006), nitrogen assimilation (Sun et al., 2014), and response to ABA (Wang et al., 2001), low temperature (Ma et al., 2015), and blue light (Warpeha et al., 2006).

Accumulating evidence indicate that heterotrimeric G proteins also play an important role in plant disease resistance against diverse pathogens (Llorente et al., 2005; Trusov et al., 2006; Zhu et al, 2009; Ishikawa, 2009; Cheng et al., 2015). Recent reports indicate that XLG2, AGB1, and AGG1/2 mediate immune responses downstream of PRRs (Ishikawa, 2009; Zhu et al, 2009; Liu et al., 2013; Lorek et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2013; Maruta et al., 2015). XLG2 was first shown to play an important role in basal resistance to P. syringae (Zhu et al., 2009). A recent report showed that XLG2, but not XLG1, is required for resistance to P. syringae and flg22-induced ROS production (Maruta et al., 2015). AGB1 and AGG1/2, but not AGG3, are required for resistance to P. syringae and microbial pattern-induced ROS production (Liu et al., 2013; Lorek et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2013). Furthermore, epistatic analyses indicated that AGB1 acts in the same pathway as RbohD (Torres et al., 2013). However, it is still debated whether plants possess 7 transmembrane GPCRs (Taddese et al., 2014; Urano and Jones, 2014). One recent report suggests that GPA1, AGG1/2 can interact with BAK1 and the chitin-binding receptor kinase CERK1, but not FLS2 (Aranda-Sicilia et al., 2015). However, GPA1 does not appear to play a role in flg22-induced ROS and disease resistance to P. syringae (Liu et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2013). How XLG2 and AGB1 regulate PRR-mediated immunity remains elusive.

In this study, we report XLG2, AGB1, and AGG1/2 modulates flg22-triggered immunity by directly coupling to the FLS2-BIK1 receptor complex. Prior to activation by flg22, the G proteins attenuate the proteasome-dependent degradation of BIK1, ensuring optimum signaling competence. After flg22 stimulation, XLG2 dissociates from AGB1, indicating a ligand-induced dissociation of Gα from Gβγ. In addition, we provide evidence that activation by flg22 additionally leads to XLG2 phospohrylation by BIK1, and this phosphorylation positively regulates RbohD-dependent ROS production. Together the study illustrates two distinct mechanisms underlying the G protein-mediated regulation of the FLS2 signaling.

Results

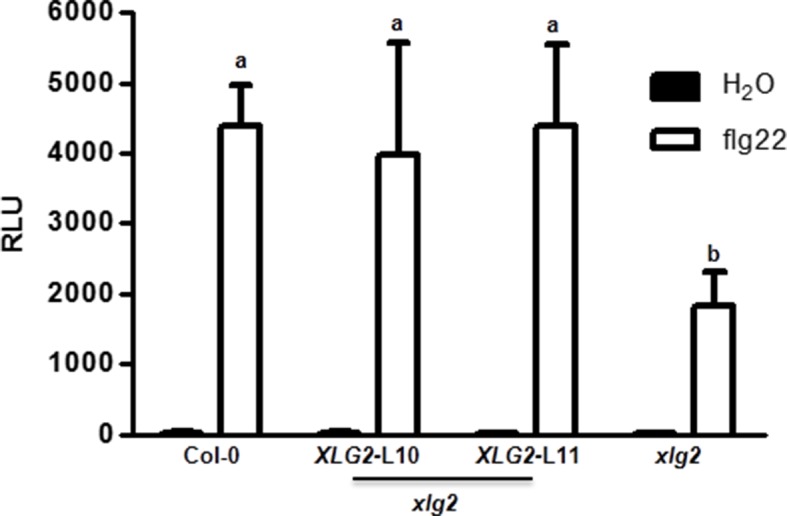

Characterization of XLG2 and AGB1 in FLS2-mediated immunity

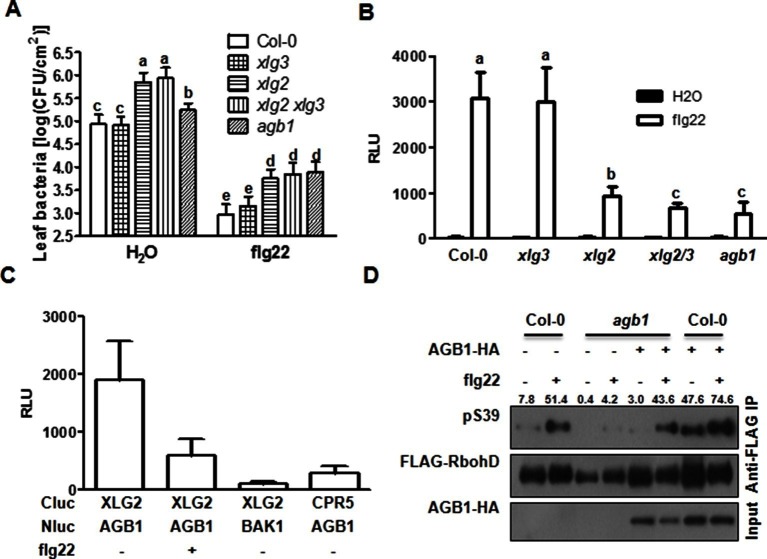

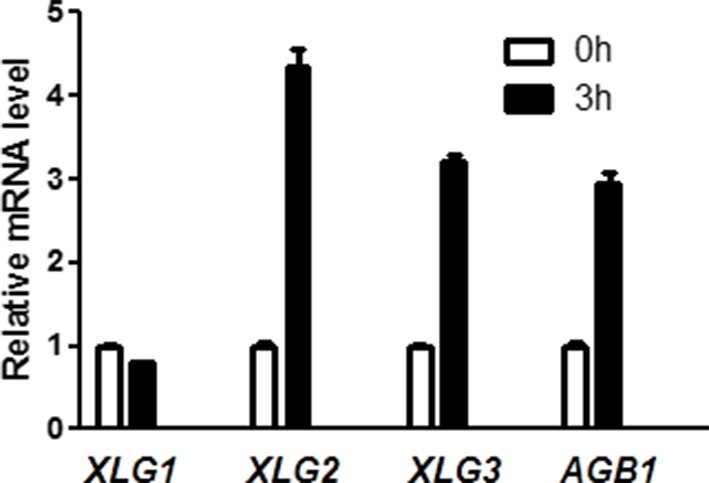

To identify additional components of the FLS2 immune pathway, we conducted a reverse genetic screen for mutants that were compromised in flg22-induced disease resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato (Pst). One mutant displayed significantly reduced resistance was xlg2 (Figure 1A), confirming previous report by Zhu et al. (2009). Further characterization indicated that the mutant is compromised in flg22-induced ROS (Figure 1B, Figure 1—figure supplement 1), confirming results reported previously (Maruta et al., 2015). An examination of gene expression showed that XLG2, XLG3, and AGB1, but not XLG1, were induced in response to flg22 treatment (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). This is in agreement with the recent report that XLG2/3, but not XLG1, are required for flg22-induced responses and disease resistance to P. syringae (Maruta et al., 2015). A comparison of xlg2 and agb1 mutant showed that the two mutants were similarly compromised in flg22-induced ROS burst and resistance against Pst, supporting that they act together to regulate FLS2 immunity. Interestingly, xlg2 plants were more susceptible to Pst than agb1 plants in the absence of flg22 treatment (Figure 1A), suggesting that XLG2 plays additional role in plant immunity independent of AGB1. As reported previously (Maruta et al., 2015), we found that the xlg3 mutant was similar to WT in Pst resistance and flg22-induced ROS, whereas the xlg2 xlg3 double mutant was slightly more defective in Pst resistance (Figure 1A) and flg22-induced ROS (Figure 1B), indicating that XLG2/3 play additive roles in flg22-induced immunity. Because AGG1/2, but not AGG3 and GPA1, are required for flg22-induced defense responses and Pst resistance (Liu et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2013), these results confirmed that the heterotrimeric G proteins required for FLS2 signaling and Pst resistance include the non-canonical Gα proteins XLG2/3, Gβ protein AGB1, and Gγ proteins AGG1/2.

Figure 1. G proteins are required for FLS2-mediated immunity.

(A) XLG2/3 and AGB1 play overlapping but not identical roles in disease resistance to Pst. Plants of indicated genotypes were infiltrated with H2O and flg22 1 day before infiltration with P. syringae DC3000, and bacteria number was determined 2 days later (mean ± SD; n ≥ 6; p<0.05, Student’s t-test; different letters indicate significant difference). (B) xlg2/3 and agb1 are similarly compromised in flg22-induced ROS burst. Leaves of the indicated genotypes were examined for flg22-induced ROS production, and peak RLU values are shown (mean ± SD; n ≥ 6; p<0.05, Student’s t-test; different letters indicate significant difference). (C) Flg22 treatment disrupts XLG2-AGB1 interaction. Cluc-XLG2 and AGB1-HA-Nluc constructs are transiently expressed in Nb leaves, relative luminescence unit (RLU) was measured 2 days later. Cluc-CPR5 and BAK1-HA-Nluc were used as negative control (mean ± SD; n ≥ 6). (D) Flg22-induced RbohD phosphorylation is impaired in agb1. FLAG-RbohD and/or AGB1-HA constructs were expressed under control of the 35S promoter in WT or agb1 protoplasts. The FLAG-RbohD protein was affinity purified and subject to anti-FLAG and anti-pSer39 immuoblot analyses. Numbers indicate arbitrary units of RbohD pS39 phosphorylation calculated from densitometry measurements normalized to total FLAG-RbohD protein. Each experiment was repeated three times, and data of one representative experiment are shown.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.13568.003

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Flg22-induced ROS burst is compromised in xlg2 plants.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. XLG2/3 and AGB1, but not XLG1, are transcriptionally induced by flg22.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. XLG2/3 interact with AGB1 through both N and C termini.

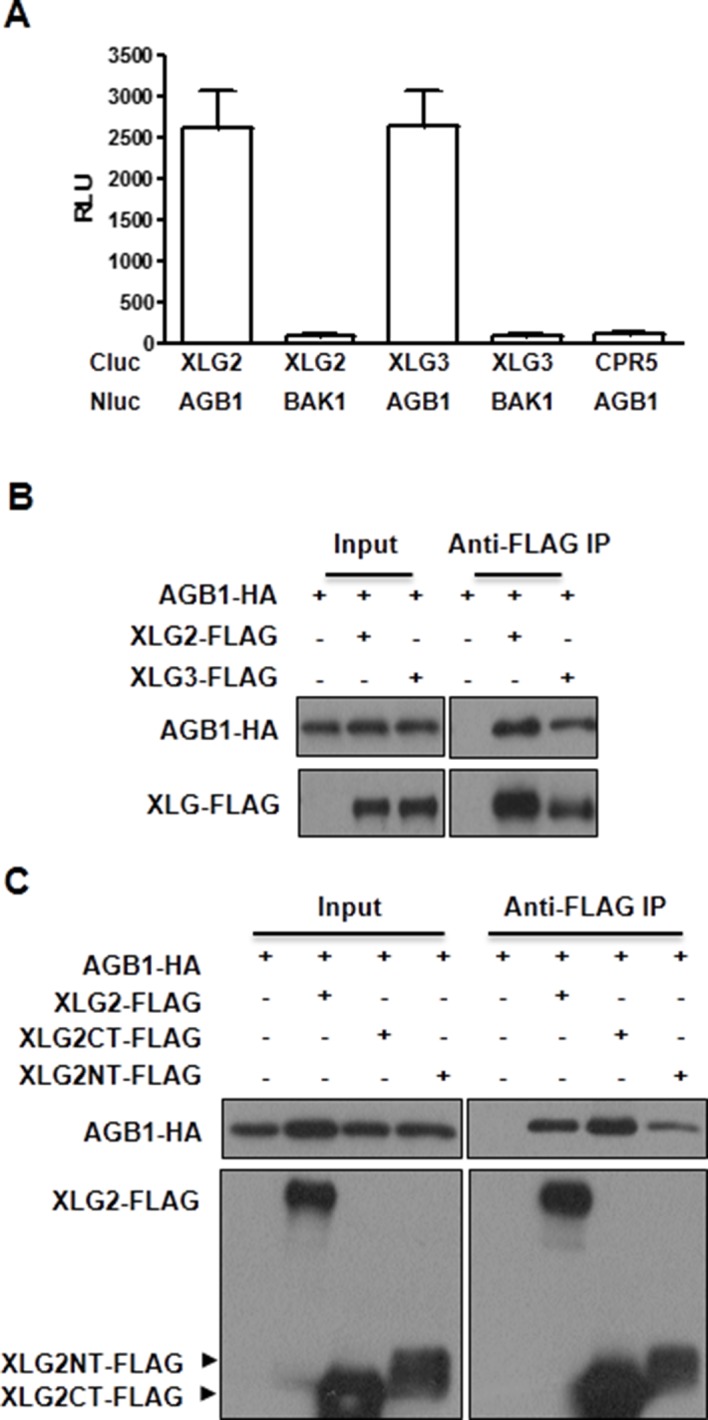

Previous yeast two-hybrid, yeast tri-hybrid and Bi-Fluorescence Complementation assays showed that XLG2/3 form heterotrimers with the Gβγ dimer through AGB1 (Zhu et al., 2009; Maruta et al., 2015; Chakravorty et al., 2015). Consistent with this, luciferase complementation and co-immunoprecipitation assays detected XLG2-AGB1 and XLG3-AGB1 interactions in Nicotiana Benthamiana (Nb) plants (Figure 1C, Figure 1—figure supplement 3A) and Arabidopsis protoplasts (Figure 1—figure supplement 3B–C). Both the N and C termini of XLG2 are sufficient for the interaction with AGB1 (Figure 1—figure supplement 3C). Note that XLG2-FLAG and AGB1-HA used in co-IP assays retain their biological functions when introduced into agb1 protoplasts or xlg2 plants (see below in Figures 1D and 5E). In the animal model, the heterotrimeric G protein is dynamically regulated upon ligand stimulation of GPCR. We tested whether flg22 treatment can similarly regulate XLG2-AGB1 interaction. As shown in Figure 1C, the flg22 treatment resulted in a great reduction in XLG2-AGB1 interaction in Nb plants, suggesting that Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins are reminiscent of their animal counterparts in that the heterotrimer is dynamically regulated upon ligand activation of receptors. Because the heterotrimeric G protein mutants under investigation all display defects in flg22-induced ROS, which requires phosphorylation of the NADPH oxidase RbohD by the BIK1 kinase (Kadota et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014), we monitored the flg22-induced phosphorylation of RbohD in agb1 using antibodies that recognize the BIK1-specific S39 phosphorylation. Flg22-induced S39 phosphorylation was significantly reduced in agb1 mutant protoplasts, whereas complementation of the mutant protoplasts with AGB1 restored RbohD S39 phosphorylation (Figure 1D). Consistent with a positive role of AGB1 in flg22-induced RbohD S39 phosphorylation, transient overexpression of AGB1 in WT protoplasts resulted in constitutive S39 phosphorylation in RbohD (Figure 1D). Together these results suggest that the hetero-trimeric G proteins regulate early components of the FLS2 signaling pathway.

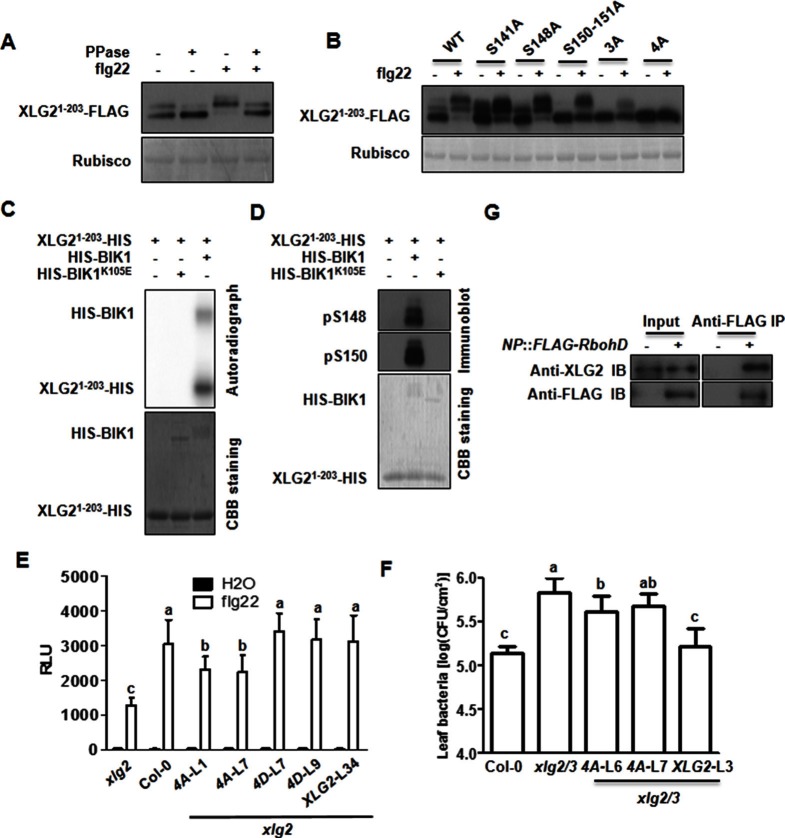

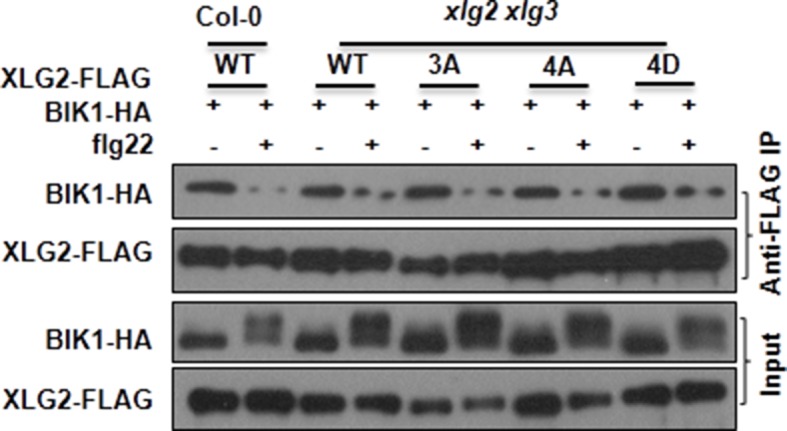

Figure 5. Phosphorylation of XLG2 by BIK1 regulates flg22-induced ROS.

(A) Flg22-induces phosphorylation of XLG2 in the N terminus. Protoplasts expressing XLG21-203-FLAG were treated with flg22. The total protein was treated with (+) or without (-) λ protein phosphatase (PPase) prior to anti-FLAG immunoblot analysis. (B) Flg22-induced phosphorylation of XLG2 in protoplasts primarily occurs in Ser141, Ser148, Ser150 and Ser151. Different mutated form of XLG21-203-FLAG constructs were transiently expressed in WT protoplast, treated with flg22 and the migration of XLG21-203-FLAG were examined by anti-FLAG immunoblot. (C) BIK1 phosphorylates XLG2 N terminus in vitro. XLG21-203-HIS was incubated with HIS-BIK1 and HIS-BIK1K105E in the presence of 32P-γ-ATP and analyzed by autoradiography. CBB, coomassie brilliant blue. (D) BIK1 phosphorylates XLG2 at Ser148 and Ser150 in vitro. XLG21-203-HIS was incubated with HIS-BIK1 and HIS-BIK1K105E in kinase reaction buffer. Protein phosphorylation was detected by anti-pSer148 and pSer150 immunoblots. (E) XLG2 phosphorylation is required for flg22-induced ROS. xlg2 mutant plants were transformed with WT (NP::XLG2-L34), non-phosphorylatable (4A-L1 and 4A-L7), or phospho-mimicking (4D-L7 and 4D-L9) forms of XLG2 under control of the native XLG2 promoter. Independent T2 lines were examined for flg22-induced ROS burst and peak relative luminescence unit (RLU) values are shown. (mean ± SD; n ≥ 6; p<0.05, Student’s t-test; different letters indicate significant difference). (F) XLG2 phosphorylation is required for Pst resistance. xlg2/3 double mutant plants were transformed with WT (XLG2-L3) or non-phosphorylatable (4A-L6 and 4A-L7) form of XLG2 under control of the native XLG2 promoter. Independent T2 lines were inoculated with Pst, and bacterial populations in leaves were measured 3 days post inoculation. (mean ± SD; n ≥ 6; p<0.05, Student’s t-test; different letters indicate significant difference). (G) XLG2 interacts with RbohD in Arabidopsis plants. rbohD plants were transformed with the FLAG-RbohD transgene under control of the RbohD native promoter. The resulting plants were used for Co-IP assay. Each experiment was repeated two (C, G) or three (A, B, D–F) times, and data of one representative experiment are shown.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.13568.018

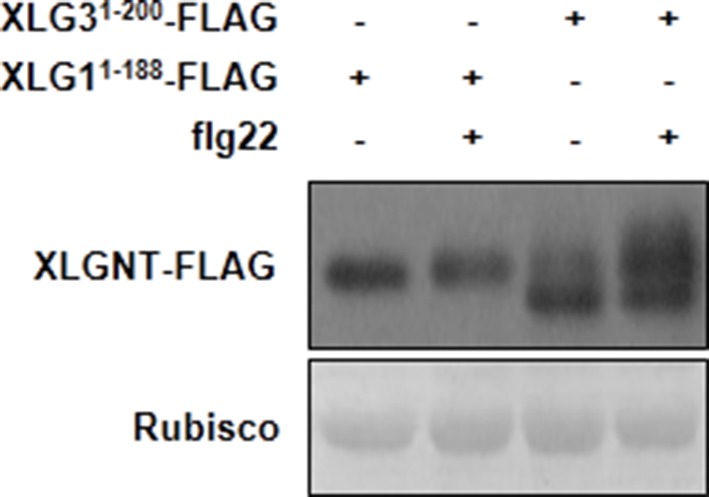

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. The N terminus of XLG3, but not XLG1, is phophorylated upon flg22-treatment.

Figure 5—figure supplement 2. Phospho-sites in XLG2 isolated from flg22-treated protoplasts.

Figure 5—figure supplement 3. Mutations that block or mimic XLG2 phosphorylation do not impact BIK1 stability and XLG2-BIK1 interaction.

Figure 5—figure supplement 4. XLG2/3 interact with RbohD in Nb plants.

Dynamic and direct interaction between XLG2 and the FLS2-BIK1 complex

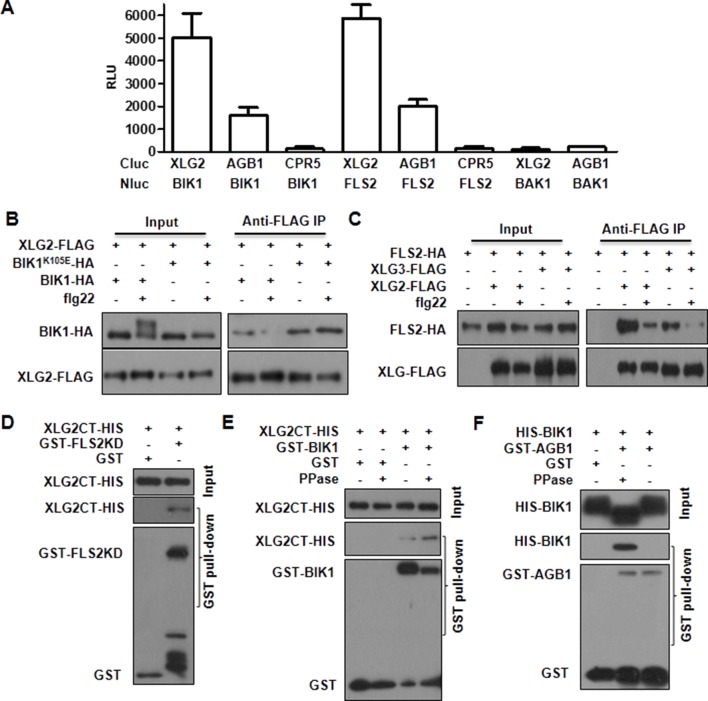

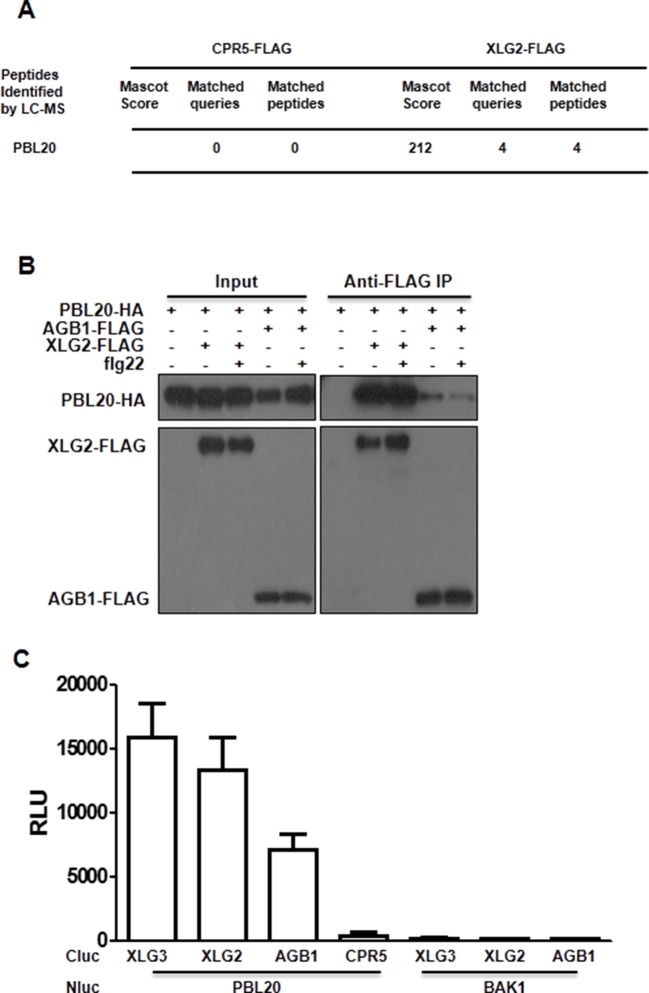

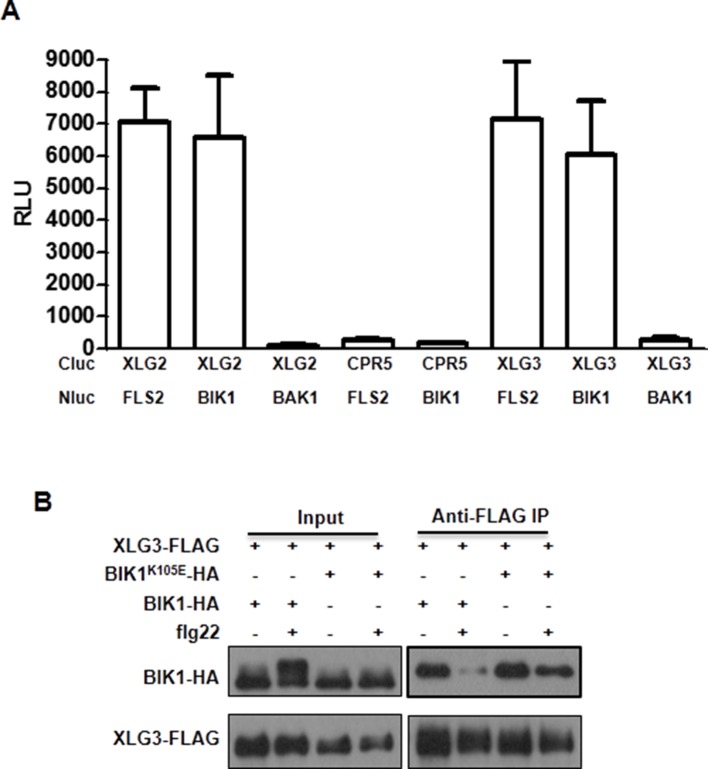

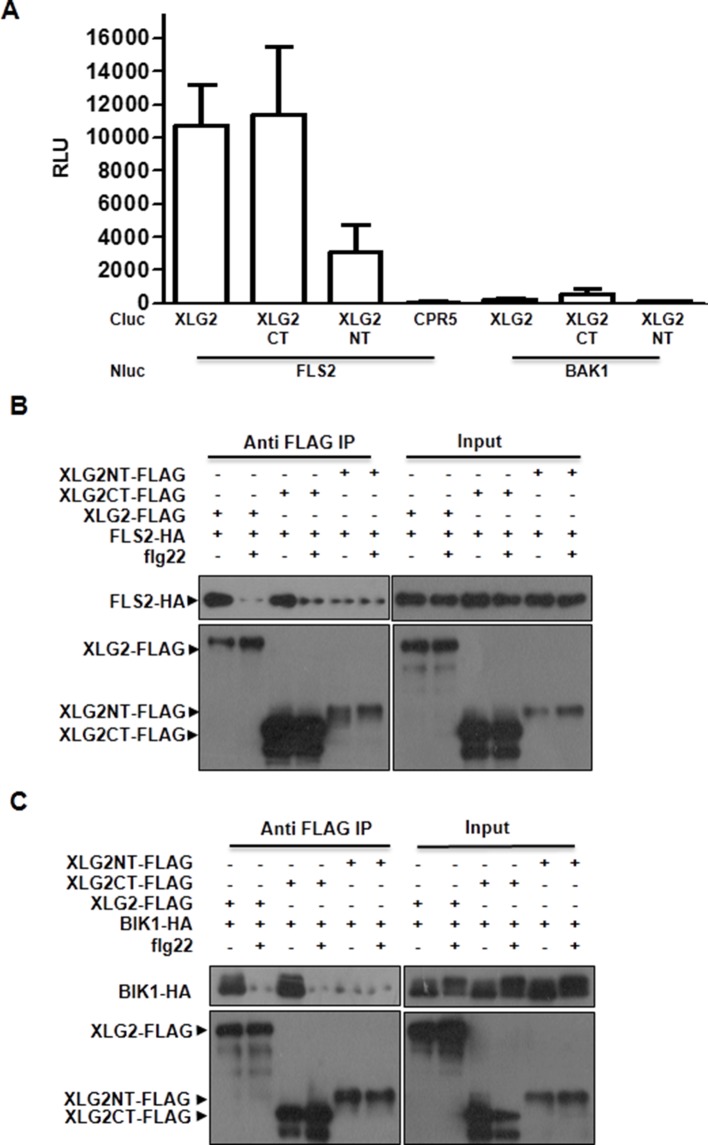

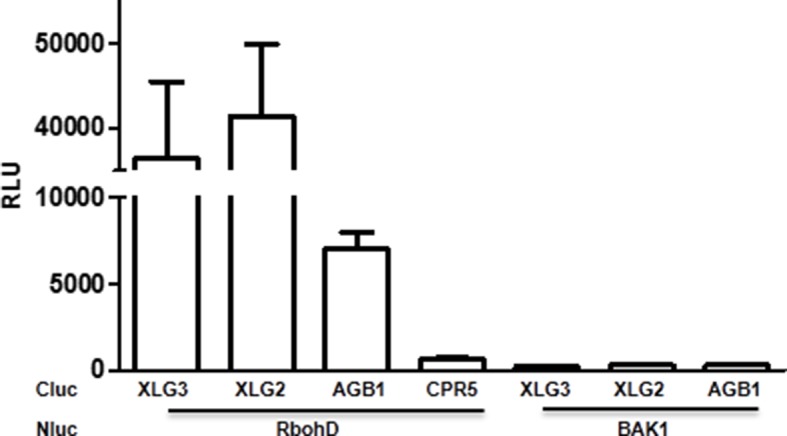

To identify potential proteins regulated by XLG2, we performed immunoprecipitation of XLG2-FLAG transiently expressed in protoplasts. LC-MS/MS analysis of the immune complex identified four peptides corresponding to PBL20 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A), a homolog of BIK1. In contrast, immunoprecipitation of the control protein CPR5-FLAG failed to identify any PBL20 peptides. Co-IP and luciferase complementation assays confirmed that XLG2/3 indeed interacted strongly with PBL20 (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B–C). AGB1 also interacted with PBL20, albeit much weaker than did XLG2. Because PBL20 and BIK1 belong to the same family of receptor like cytoplasmic kinases (RLCKs) and share similar biochemical properties (Zhang et al., 2010), we therefore tested whether BIK1 also interacts with the G proteins. Luciferase complementation assays showed that XLG2/3 strongly interacted with BIK1 but not BAK1 or CPR5 in Nb plants (Figure 2A, Figure 2—figure supplement 2A), whereas AGB1 interacted with BIK1 at a much lower level. Similarly, FLS2 also displayed strong interactions with XLG2/3 and a weaker interaction with AGB1 (Figure 2A, Figure 2—figure supplement 2A). The interactions were further confirmed by Co-IP assays (Figure 2B–C, Figure 2—figure supplement 2B). In the absence of flg22 treatment, XLG2/3 strongly interacted with BIK1 and FLS2 (Figure 2B–C, Figure 2—figure supplement 2B). Treatment of protoplasts with flg22 led to a much weaker interaction, indicating that flg22 induces dissociation of XLG2 from the FLS2 receptor complex. The BIK1K105E-HA mutant protein, which is defective in ATP-binding and dominantly inhibits flg22-induced signaling when expressed in protoplasts (Zhang et al., 2010), interacted with XLG2 and XLG3 irrespective of the presence or absence of flg22, suggesting that the activation of the BIK1 kinase is required for the dissociation.

Figure 2. Flg22 regulates interactions between G proteins and the FLS2-BIK1 receptor complex.

(A) XLG2 and AGB1 interact with BIK1 and FLS2 in Nb plants. The indicated Nluc and Cluc constructs were transiently expressed in Nb plants for luciferase complementation assay. Relative luminescence unit (RLU) shows the strength of protein-protein interaction (mean ± SD; n ≥ 6. (B) XLG2 interacts with BIK1 in Arabidopsis protoplasts and the interaction is dynamically regulated by flg22. (C) XLG2/3 interact with FLS2 in Arabidopsis protoplasts and the interaction is dynamically regulated by flg22. The indicated constructs were co-expressed in WT protoplasts, and Co-IP assays were performed using agarose-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody. BIK1K105E carries a mutation in the ATP-binding site. (D) The C terminus of XLG2 directly interacts with FLS2 kinase domain. XLG2CT-HIS (amino acids 459–861) was incubated with GST or GST-FLS2KD (FLS2 kinase domain) for GST pull-down assay and detected by anti-HIS and anti-GST immunoblots. (E) XLG2 primarily interacts with non-phosphorylated BIK1. XLG2CT-HIS was incubated with GST or GST-BIK1 that was untreated or pre-treated with λ phosphatase (PPase), and GST pull-down assay was performed. (F) AGB1 interacts with the non-phosphorylated BIK1. Untreated or PPase-treated BIK1-HIS was incubated with GST or GST-AGB1, and GST pull-down assay was performed. Each experiment was repeated two (D–F) or three (A–C) times, and data of one representative experiment are shown.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. PBL20 interacts with G proteins.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. XLG3 interacts with BIK1.

Figure 2—figure supplement 3. XLG2 interacts with FLS2 and BIK1 primarily through the C terminus.

We next tested XLG2 domains for interactions with BIK1 and FLS2. Luciferase complementation and Co-IP assays showed that the C terminus of XLG2 interacted strongly with BIK1 and FLS2, whereas the N terminus of XLG2 displayed weak interactions (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A–C), indicating that XLG2 interacts with FLS2 and BIK1 primarily through its C terminus. Similar to the full-length XLG2 protein, the C terminus of XLG2 also dissociated from BIK1 when protoplasts were treated with flg22 (Figure 2—figure supplement 3C). GST pull-down assays showed that the HIS-tagged C-terminal fragment of XLG2 strongly interacted with GST-tagged FLS2 kinase domain, but not GST alone (Figure 2D), indicating that the C terminus of XLG2 directly interacts with FLS2. Surprisingly, GST pull-down assay showed a weak interaction between XLG2 and BIK1 (Figure 2E). Interestingly, phosphatase treatment of BIK1 enhanced its interaction with XLG2 (Figure 2E), suggesting that XLG2 has greater affinity with non-phosphorylated BIK1. We similarly tested interaction between AGB1 with untreated and de-phosphorylated BIK1 by GST pull-down assay. While the un-treated BIK1 is unable to interact with AGB1, the de-phosphorylated form of BIK1 strongly interacted with AGB1 (Figure 2F). Together the results show that the G proteins dynamically interact with the FLS2-BIK1 receptor complex during FLS2 signaling, and the findings are consistent with the observed defects in flg22-induced responses and RbohD phosphorylation in the G protein mutants.

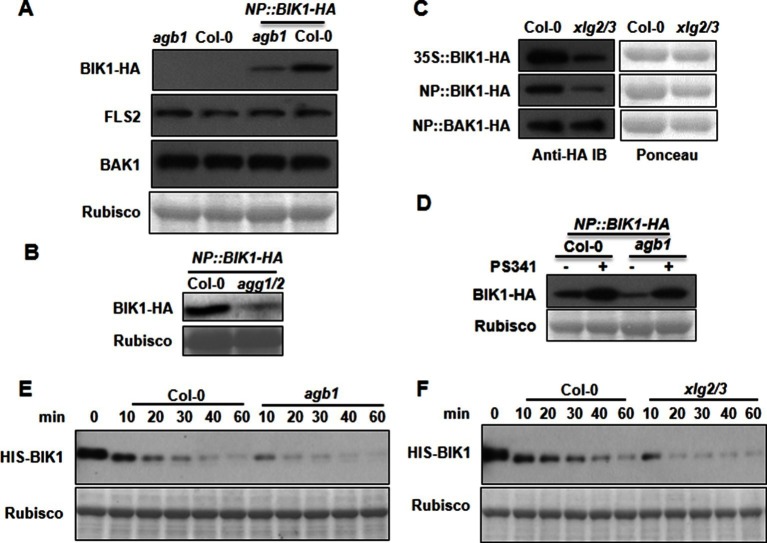

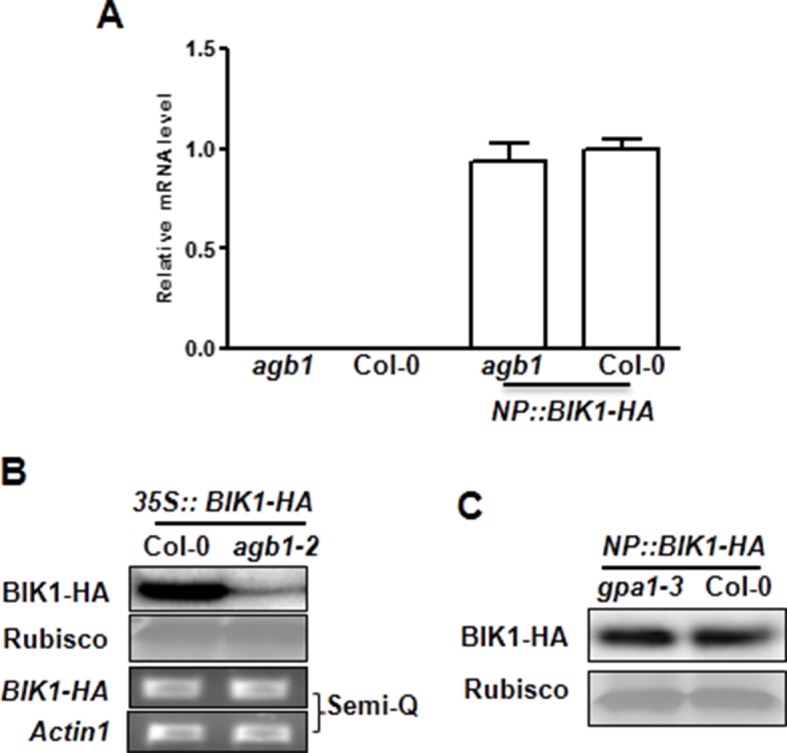

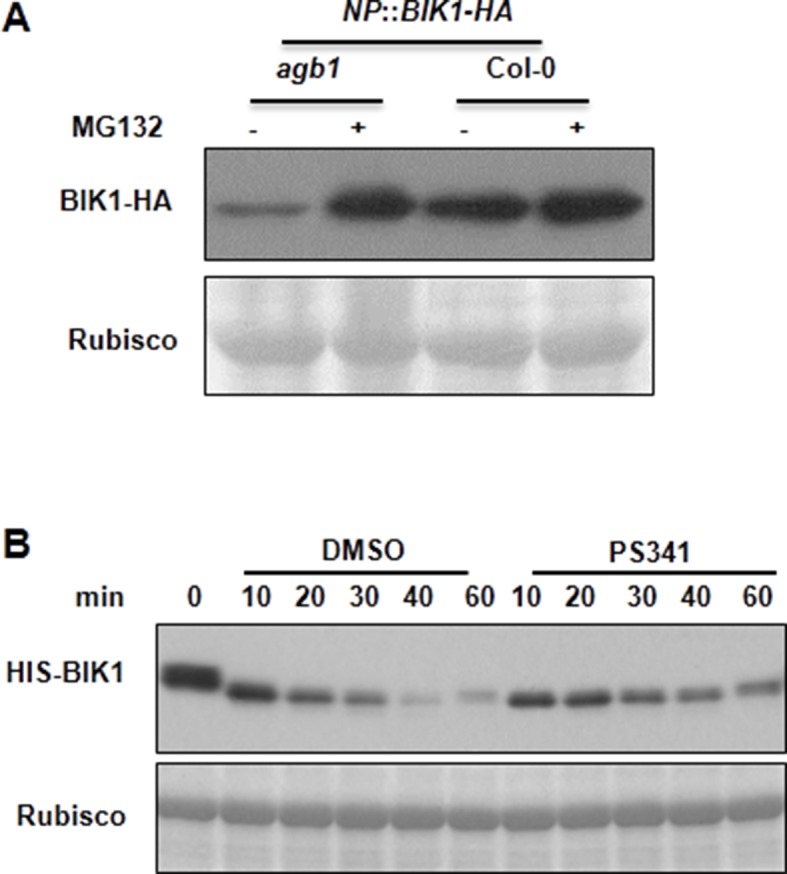

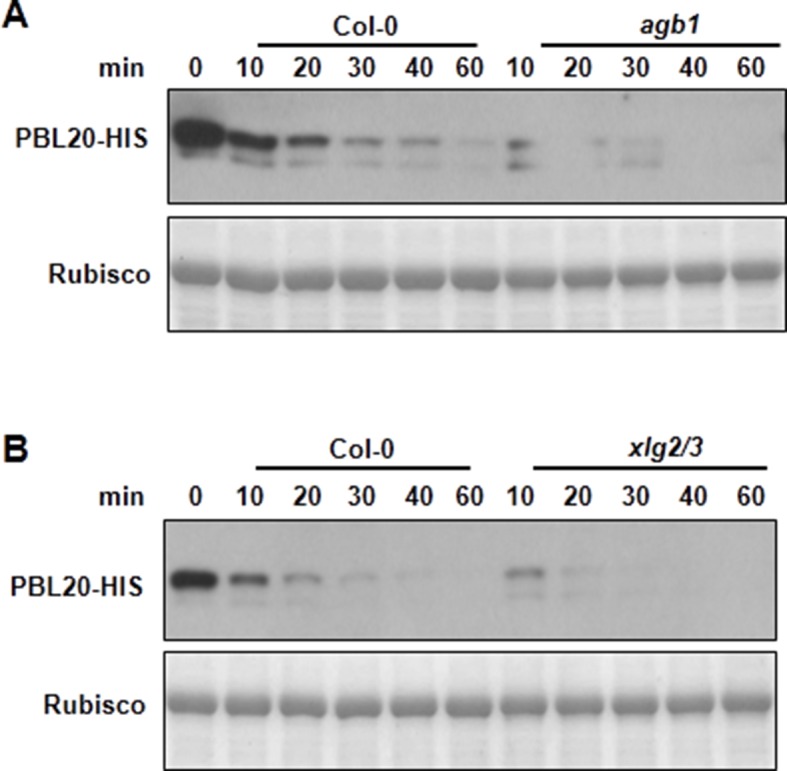

XLG2/3, AGB1, and AGG1/2 maintain BIK1 stability by attenuating the proteasome-dependent degradation of BIK1

The direct interaction of XLG2/3 with the FLS2 receptor complex prompted us to examine FLS2, BIK1 and BAK1 proteins in the G protein mutants. To examine BIK1 accumulation, we crossed agb1 with a transgenic line carrying a BIK1-HA transgene under control of the native BIK1 promoter (Zhang et al., 2010) and identified sibling transgenic lines of either agb1 or AGB1 genotype. Immunoblot analyses showed that the BIK1-HA protein accumulated to a much lower level in agb1 compared to WT (Figure 3A), indicating that AGB1 is required for BIK1 accumulation in plants. In contrast, FLS2 and BAK1 protein accumulation was not affected in agb1, indicating a specific effect on BIK1 protein. Examination of BIK1-HA transcripts indicated that the transgene is similarly expressed in agb1 and WT plants (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A). To further rule out the possibility that AGB1 modulates BIK1 at transcriptional level, we transformed agb1 and WT plants with BIK1-HA transgene under the control of the 35S promoter. Again, a much lower BIK1-HA accumulation was observed in agb1 than in WT plants although the BIK1-HA transcripts accumulated to similar levels in the two lines (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B). Similarly, the BIK1-HA protein accumulation was greatly reduced in agg1 agg2 double mutant plants (Figure 3B), indicating that AGG1/2 are also required for BIK1 accumulation. We further asked whether XLG2 and XLG3 are required for BIK1 accumulation by transiently expressing BIK1-HA in xlg2 xlg3 mutant protoplasts. Regardless of the promoter used for BIK1-HA expression, BIK1 accumulated to lower levels in the xlg2 xlg3 double mutant than in WT protoplasts (Figure 3C), indicating that XLG2/3 are also required for BIK1 accumulation. The defect in protein accumulation is specific to BIK1, as BAK1 accumulation was not affected in xlg2 xlg3 protoplasts (Figure 3C). The accumulation of BIK1-HA was not affected in gpa1 mutant plants (Figure 3—figure supplement 1C), a result that is consistent with previous report that GPA1 is not required for flg22-induced ROS (Liu et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2013). BIK1 is known to be turned-over through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Monaghan et al., 2014). Treatment of plants with proteasome inhibitors PS341 (Figure 3D) and MG132 (Figure 3—figure supplement 2A) restored BIK1 accumulation in agb1 mutant plants, suggesting that AGB1 regulates BIK1 stability through the proteasome pathway. We further performed in vitro protein degradation assay to compare the rate of BIK1 degradation in total protein extracts from WT and mutant plants. The recombinant BIK1 was degraded in the WT extract, and this degradation was blocked by PS341 (Figure 3—figure supplement 2B), recapitulating the proteasome-dependent degradation of BIK1 in plants. The rate of BIK1 degradation was more rapid in agb1 and xlg2 xlg3 extracts compared to that in the WT extract (Figure 3E–F). Because XLG2 also interacted with PBL20, we further tested whether XLG2/3 and AGB1 similarly regulate PBL20 stability. Indeed, PBL20 was also degraded in WT extracts, and this degradation was enhanced when extracts from xlg2 xlg3 or agb1 mutants were used (Figure 3—figure supplement 3A–B). Together these results demonstrate that the heterotrimeric G proteins formed by XLG2/3, AGB1, and AGG1/2 attenuate proteasome-dependent degradation of BIK1 and PBL20.

Figure 3. G proteins positively regulate immunity and BIK1 stability.

(A) AGB1 is required for accumulation of BIK1, but not FLS2 and BAK1. BIK1-HA was introduced into agb1 by crossing, homozygotes of the indicated genotypes in F3 generation were used for immunoblot analyses. (B) AGG1/2 are required for BIK1 stability. NP::BIK1-HA was introduced into agg1/2 by crossing, homozygous plants in F3 generation were subject to immunoblot analyses. (C) XLG2/3 are required for BIK1 accumulation. NP::BIK1-HA, 35S::BIK1-HA and NP::BAK1-HA plasmids were transiently expressed in WT and xlg2/3 protoplasts, and accumulation of BIK1 and BAK1 was determined by immunoblot analyses. (D) AGB1 regulates BIK1 accumulation through the proteasome pathway. One-week-old NP::BIK1-HA seedlings of WT (Col-0) or agb1 background were pretreated with DMSO (-) or 100 μM proteasome inhibitor PS341(+) for 8 hr before total protein was isolated for immunoblot analysis. (E) The agb1 extract shows accelerated degradation of BIK1 in vitro (F) The xlg2 xlg3 extract shows accelerated degradation of BIK1. Total extracts from WT (Col-0), agb1 and xlg2 xlg3 seedlings were incubated with HIS-BIK1 protein at 22°C for the indicated times, and equal amounts of sample were analyzed using anti-HIS immunoblot. Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and data from one representative experiment are shown.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. G proteins are required for BIK1 stability.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. AGB1 regulates BIK1 stability through proteasome pathway.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. AGB1 and XLG2/3 attenuate PBL20 degradation.

BIK1 accumulation accounts for the G protein-mediated regulation of immunity

We next tested whether the regulation of BIK1 stability contributes to the role of heterotrimeric G proteins in flg22-induced immune responses. Transient overexpression of BIK1 in xlg2 xlg3 and agb1 protoplasts largely restored the flg22-induced RbohD S39 phosphorylation (Figure 4A), indicating that the heterotrimeric G proteins positively regulate RbohD phosphorylation at least in part by enhancing BIK1 stability. We next asked whether increased copy number of BIK1 could rescue flg22-induced ROS burst in agb1 mutant. Introgression of the NP::BIK1-HA transgene into agb1 by crossing significantly enhanced flg22-induced ROS production in these plants compared to agb1 plants that contained only the endogenous copy of BIK1 (Figure 4B), indicating that increasing BIK1 accumulation by the transgene at least partially restored flg22-induced ROS in agb1. Col-0 NP::BIK1-HA plants displayed higher level of ROS compared to non-transgenic WT plants (Figure 4B), indicating that BIK1 protein level is rate-limiting in flg22-induced immune responses. We further tested the impact of the NP::BIK1-HA transgene on flg22-induced resistance to Pst. While the agb1 consistently supported greater amount of bacterial growth compared to WT plants following flg22 treatment, the agb1 NP::BIK1-HA plants were indistinguishable from WT (Figure 4C). Col-0 NP::BIK1-HA plants supported less bacterial growth than did WT plants, further supporting the importance of BIK1 abundance in FLS2-mediated immunity. We similarly introduced the NP::BIK1-HA transgene into xlg2 xlg3 double mutant plants by transformation. The resulting transgenic lines displayed near WT ROS production (Figure 4D) and Pst resistance (Figure 4E) in response to flg22 treatment, indicating that XLG2/3 also regulate FLS2-mediated immunity by controlling BIK1 stability.

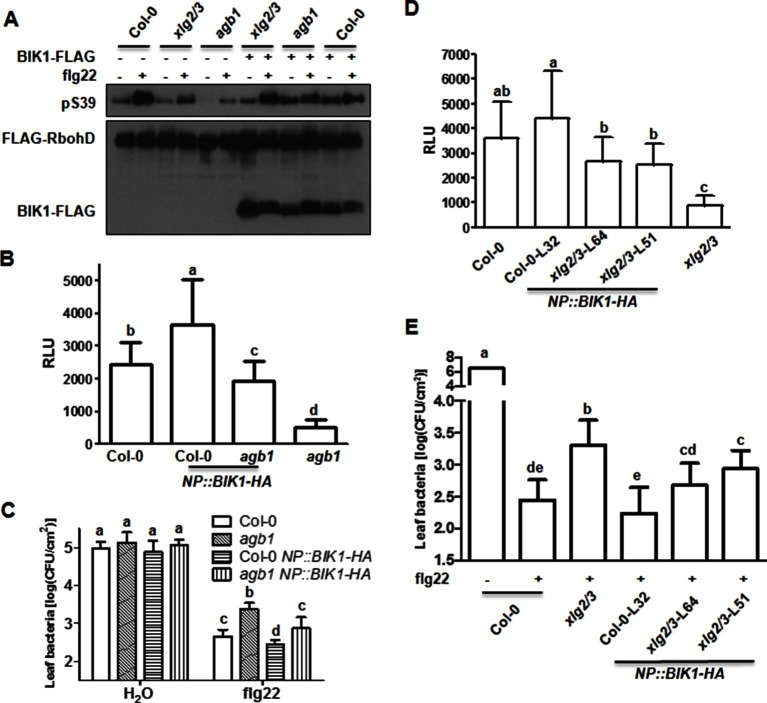

Figure 4. BIK1 level accounts for G protein-mediated regulation of FLS2 immunity.

(A) Transient expression of BIK1 in agb1 and xlg2/3 mutant protoplasts restores RbohD phosphorylation. FLAG-RbohD and BIK1-HA constructs are transiently expressed in protoplasts from WT (Col-0), agb1 and xlg2/3. FLAG-RbohD protein was affinity purified and detected by anti-FLAG and anti-pSer39 immuoblots. (B) BIK1 transgene restores flg22-induced ROS burst in agb1. (C) BIK1 transgene partially restores flg22-induced resistance to Pst in agb1. NP::BIK1-HA was introduced into agb1 by crossing, transgenic lines of agb1 or Col-0 background in the F3 generation were used for the assays. (D) BIK1 transgene partially restores flg22-induced ROS burst in xlg2 xlg3 mutant. (E) BIK1 transgene partially restores flg22-induced resistance to Pst. The NP::BIK1-HA transgene was introduced into WT (Col-0-L32) and xlg2 xlg3 (xlg2/3-L64 and xlg2/3-L51) plants by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Independent T2 transgenic lines were used for the assays. Peak relative luminescence unit (RLU) values were shown for ROS assays (B and D) and leaf bacterial populations 2 days after bacterial inoculation were shown for flg22-protection assays (C and E). Bars in B-E represent mean ± SD (n ≥ 6; p<0.05, Student’s t-test; different letters indicate significant difference). Each experiment was repeated two (A) or three (B–E) times, and data of one representative experiment are shown.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.13568.016

XLG2 is phosphorylated in the N terminus upon flg22 treatment

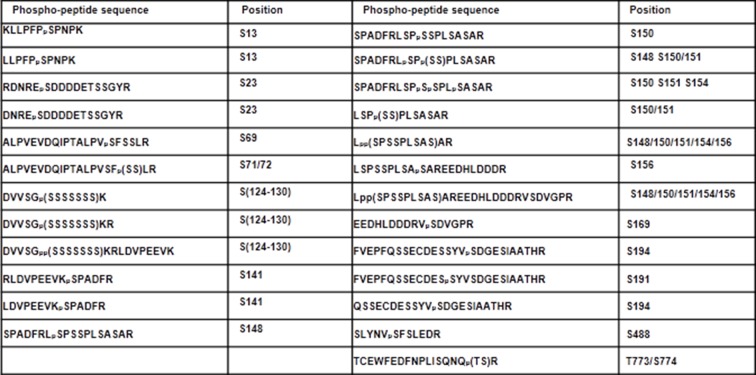

BIK1 is postulated to phosphorylate multiple proteins, including RbohD, in PTI (Pattern-Triggered Immunity) signaling (Kadota et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014; Macho and Zipfel, 2014). An examination of XLG2 N-terminal fragment expressed in protoplasts following flg22 treatment showed a prominent shift in protein migration in SDS-PAGE (Figure 5A). The shift of protein mobility was sensitive to phosphatase treatment, which is indicative of flg22-induced phosphorylation in XLG2. The flg22-induced phosphorylation similarly occurred to the N terminus of XLG3, but not XLG1 (Figure 5—figure supplement 1), which is consistent with the notion that XLG2/3 but not XLG1, are involved in flg22 signaling. To determine phospho-sites in XLG2, we expressed full-length XLG2-FLAG in protoplasts. Following flg22 treatment, the XLG2-FLAG protein was affinity-purified and subject to LC-MS/MS analysis for phospho-peptides. We were able to recover 87% of total peptide sequence, among which we identified 23 phospho-peptides corresponding to at least 15 phospho-sites (Figure 5—figure supplement 2). Interestingly, all but two phospho-peptides were located in the N terminus. Strikingly, phospho-sites between amino acids 141–156 accounted for nearly half of the phospho-peptides. We further tested whether these are the major phospho-sites by site-directed mutagenesis. Simultaneously substituting three to four of these residues into non-phosphorylatable alanine (XLG2S148A,S150A,S151A; XLG2S141A,S148A,S150A,S151A) resulted in severe reduction to complete elimination in flg22-induced band shift in XLG2 N terminus (Figure 5B), indicating that amino acids Ser141, Ser148, Ser150 and Ser151 are indeed required for overall phosphorylation of XLG2 in response to flg22 treatment.

We next tested whether BIK1 is able to phosphorylate XLG2 N terminus in vitro Radio-labelling assay showed that the recombinant BIK1, but not BIK1K105E, strongly phosphorylated the N terminus of XLG2 (Figure 5C). To determine whether the major phospho-sites in XLG2 were also phosphorylated by BIK1, we raised antibodies that specifically recognize phospho-S148 and phospho-S150. Immunoblot analysis showed that S148 and S150 were indeed phosphorylated in vitro by BIK1, but not BIK1K105E (Figure 5D).

XLG2 phosphorylation is required for disease resistance to Pst and optimum ROS production upon flg22 induction

We introduced WT, non-phosphorylatable (XLG2S141A,S148A,S150A,S151A) and phospho-mimicking (XLG2S141D,S148D,S150D,S151D) forms of XLG2-FLAG transgene under control of the native XLG2 promoter into xlg2 plants and analyzed flg22-induced ROS production in the resulting transgenic lines. While the xlg2 transgenic lines carrying the WT or phospho-mimicking XLG2-FLAG transgene completely restored the flg22-induced ROS to WT level, the two lines transformed with the non-phosphorylatable XLG2-FLAG transgene only partially restored the flg22-induced ROS (Figure 5E). The inability of phospho-mimicking XLG2 to constitutively activate ROS suggests that the phosphorylation of XLG2 is required, but not sufficient, for optimum activation of RbohD. We further introduced WT and the non-phosphorylatable XLG2-FLAG transgene into xlg2/3 double mutants, and inoculated independent lines with Pst. While the line carrying the WT XLG2-FLAG transgene was fully restored in resistance to Pst that was indistinguishable from the WT non-transgenic plants, the two lines transformed with the non-phosphorylatable XLG-FLAG transgene were only marginally more resistant to Pst (Figure 5F). These results indicated that the phosphorylation is required, but not sufficient, for full function of XLG2. We next asked whether the phospho-site mutants affect BIK1 stability or XLG2-BIK1 interaction. When expressed in protoplasts isolated from xlg2 xlg3 plants, the phospho-site mutants allowed similar BIK1-HA accumulation compared to protoplasts expressing the WT XLG2 protein (Figure 5—figure supplement 3). These mutants also showed normal interaction with BIK1 in the absence of flg22 and normal dissociation from BIK1 in the presence of flg22. The results suggest that the phosphorylation of these sites affected neither BIK1 stability nor interaction with BIK1. Because XLG2 dissociates from BIK1 following activation by flg22 (Figure 2B), we reasoned that XLG2 may have additional effectors. Indeed, XLG2 interacted strongly with RbohD in Arabidopsis plants (Figure 5G) and Nb plants (Figure 5—figure supplement 4), providing an explanation that XLG2 phosphorylation regulates ROS burst independent of BIK1 stability. The XLG2-RbohD interaction was detected in the absence of flg22 treatment, indicating that the XLG2 constitutively interacts with RbohD.

Discussion

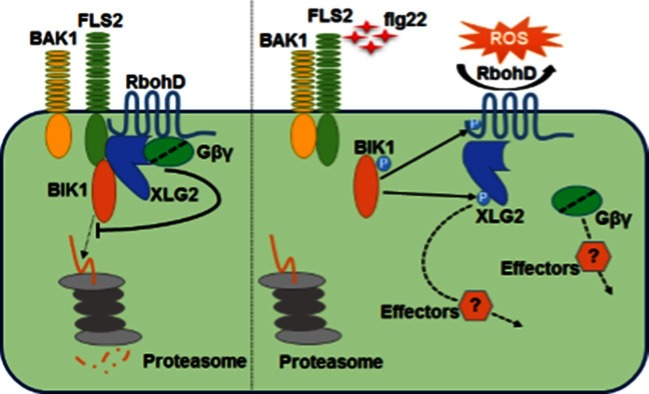

In this study we show that the Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins positively regulate plant immunity by directly interacting with the FLS2-BIK1 immune receptor complex. The heterotrimeric G proteins regulate FLS2-mediated immunity through at least two mechanisms. Before activation, XLG2/3, AGB1, and AGG1/2 positively regulate BIK1 stability by attenuating proteasome-dependent degradation of BIK1. Upon activation of the FLS2-BIK1 complex by flg22, BIK1 directly phosphorylates XLG2 in the N terminus to regulate flg22-induced ROS production, likely through the XLG2-RbohD interaction (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Model for G protein-coupled FLS2 signaling.

In the pre-activation state, the heterotrimeric G proteins composed of XLG2/3, AGB1, and AGG1/2 interact with the FLS2-BIK1 complex. Stimulation by flg22 induces BAK1-FLS2 interaction and activation of the receptor complex. This leads to the activation of the G proteins and phosphorylation of XLG2 in the N terminus. The activated G proteins dissociate from the receptor complex and regulate RbohD and other downstream effectors to positively modulate immune responses.

Coupling of heterotrimeric G proteins to FLS2

Heterotrimeric G proteins play important role in signal transduction in plants and animals. Paradoxically, plants do not possess functional GPCRs. The maize Gα protein CT2 interacts with the receptor kinase CLV1 to control shoot meristem development (Bommert et al., 2013). GPA1 and AGG1/2 have been shown to interact with BAK1 and CERK1 in yeast two-hybrid and Bi-Fluorescence Complementation assays, although the biological significance of this remains unknown (Aranda-Sicilia et al., 2015). We show that XLG2 directly interacts with FLS2 and BIK1 to regulate FLS2-mediated immunity. Thus, these studies collectively support that plant receptor kinases fulfil the roles of GPCRs by directly coupling to heterotrimeric G proteins.

Importantly, we show that the G proteins coupled to the FLS2 receptor complex are subject to multiple regulations during FLS2 signaling. The interaction between XLG2/3 and AGB1, which leads to the formation of XLG2/3-AGB1-AGG1/2 heterotrimers (Maruta et al., 2015; Chakravorty et al., 2015), is dynamically regulated by flg22. The flg22-induced dissociation of XLG2 from AGB1 likely reflects an increase of GTP-bound form of Gα which dissociates from the Gβγ dimer upon receptor activation. Secondly, the interactions of the G proteins with FLS2 and BIK1 are also dynamically regulated by flg22. The flg22-induced dissociation of the G proteins from BIK1 coincides with the flg22-induced BIK1 phosphorylation, suggesting that the flg22-induced BIK1 phosphorylation triggers the dissociation of the G proteins. Indeed, de-phosphorylation of BIK1 strongly enhanced its interactions with both XLG2 and AGB1 in vitro. The decoupling of the G proteins from the receptor maybe necessary for the regulation of down-stream effectors.

Heterotrimeric G proteins stabilizes BIK1 in the pre-activation state

BIK1 is subject to proteasome-dependent degradation (Monaghan et al., 2014). Our genetic analyses indicated that XLG2, AGB1 and AGG1/2 are required for BIK1 stability in the pre-activation state. Loss of XLG2 and AGB1 leads to accelerated degradation of BIK1, and this is blocked by the addition of proteasome inhibitors, indicating that the G proteins attenuating the proteasome-dependent degradation of BIK1. FLS2 is also subject to proteasome-dependent degradation (Lu et al., 2011). However, FLS2 accumulation is not affected by the agb1 mutation, indicating that the G proteins do not generally regulate proteasome-mediated protein degradation. These observations raise an interesting question as to whether the G proteins specifically impede the ubiquitination of BIK1 or loading of BIK1 to proteasome. Importantly, introduction of a transgenic copy of BIK1 largely restored flg22-triggered immune responses and disease resistance in xlg2 and agb1 mutants, demonstrating that a major function of the heterotrimeric G protein is to maintain the signaling competence of the FLS2-BIK1 complex in the pre-activation state.

Flg22-induced phosphorylation in XLG2 is required for optimum ROS production and Pst resistance

In addition to the ligand-induced dissociation of XLG2 from AGB1, flg22 induces the phosphorylation of XLG2 in the N terminus. This phosphorylation is likely caused by the BIK1 family kinases, as two of the major phosphor-sites induced by flg22 are also phosphorylated by BIK1 in vitro. Non-phosphorylatable XLG2 mutants are compromised in flg22-induced ROS production and disease resistance to Pst, indicating that the phosphorylation plays a positive role. However, mutations in the phospho-sites did not affect XLG2-BIK1 interaction nor BIK1 stability, suggesting that the phosphorylated XLG2 regulates components other than BIK1. Indeed, XLG2 constitutively interacts with RbohD, suggesting that the phosphorylated XLG2 further enhances ROS production by modulating RbohD. RbohD is known to be subject to multiple regulations including phosphorylation by CPK5 and BIK1 (Dubiella et al., 2013; Kadota et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014) and calcium binding to EF-hand (Ogasawara et al., 2008). The results presented here show that RbohD is additionally regulated by a phosphorylated XLG2, although the underlying mechanism remains unknown.

Conclusion

The Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins reported here are analogous to the animal counterpart in that, upon activation by receptors, dissociate from each other and activate downstream effectors. Unlike the animal heterotrimeric G proteins, however, the Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G proteins additionally regulate signaling competence of the FLS2-BIK1 complex prior to receptor activation. Taken together, our results highlight remarkable similarities and striking differences in heterotrimeric G protein-coupled receptor signaling in animals and plants as a result of independent evolution.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Arabidopsis plants used in this study include WT (Col-0), xlg2, xlg2 xlg3 (Ding et al., 2008), xlg3 (SALK_107656c), agb1-2 (Ullah et al., 2003), gpa1-3 (Jones et al., 2003) and agg1 agg2 mutants (Trusov et al., 2007), and NP::BIK1-HA (Zhang et al., 2010) and NP::FLAG-RbohD transgenic lines (Li et al., 2014).

Nicotiana benthamiana plants used for luciferase-complementation assay and Arabidopsis plants used for ROS burst, protoplast preparation and bacterial infection assays were grown in soil at 23°C and 70% relative humidity with 10/14 hr day/night photoperiod for 4–5 weeks. Arabidopsis seedlings used for BIK1 stability and in vitroprotein degradation assay were grown in half Murashige-Skoog (MS) plates at 23°C with 16/8 hr day/night photoperiod for 7–10 days.

Constructs and transgenic plants

To generate constructs for transient expression in protoplast, coding sequences of desired genes are amplified by PCR and cloned into the pUC19-35S-FLAG/HA-RBS vector. For GST and HIS fusion constructs, coding sequences were PCR-amplified and cloned into pGex 6P-1 (for GST fusion constructs) or pET28a (for HIS fusion constructs).

For complementation of xlg2 (related with Figure 1—figure supplement 1), XLG2 genomic sequence containing 2 kb native promoter and 0.5 kb 3’UTR was cloned into pENTY vector using pENTY Directional Cloning Kit (Invitrigen.Carlsbad, CA), transferred to pFAST-G01 vector using Gateway LR Clonase (Invitrogen) and introduced into xlg2 mutant plants by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.. To generate XLG2 transgenic plants containing mutated phosphosites (Figures 5E and F), a fragment containing 2 kb native promoter and coding sequence of XLG2 was fused to FLAG tag at the C terminus followed by the RBS terminator and cloned into pENTY vector. Mutations were introduced into pENTY-XLG2-FLAG by site-directed mutagenesis. All forms of XLG2-FLAG were transferred to pFAST-G01 and introduced into xlg2 or xlg2 xlg3 mutant plants by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

To generate BIK1-HA transgenic plants in agb1, gpa1-3 and agg1 agg2 background, the NP::BIK1-HA transgene (Zhang et al., 2010) was introduced into agb1, agg1/2 and gpa1-3 by crossing. Homozygous mutants and WT plants containing the transgene in the F3 generation were used for BIK1 stability and immune response assays. To express BIK1-HA under the 35S promoter, the cDNA of BIK1 was amplified by PCR and cloned into pCambia1300 with a 3x HA tag. Transgenic plants expressing 35S::BIK1-HA were generated by transforming WT or agb1-2 mutant plants with the pCambia1300-BIK1-HA construct. Transgenic lines in wild type and agb1-2 background with similar expression levels of the BIK1-HA transgene were identified by quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

To generate BIK1-HA transgenic plants in xlg2 xlg3 background, the pCAMBIA1300-NP::BIK1-HA-RBS (Zhang et al., 2010) construct was introduced into WT and xlg2 xlg3 plants by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Independent lines in T2 generation were used for ROS assay and flg22-protection assay.

Oxidative burst assay

Leaf strips form 4- to 5-week-old soil-grown Arabidopsis plants were incubated in water for 12 hr in 96-well plate before treated with luminescence detection buffer (20 μM luminol and 10 mg/ml horseradish peroxidase) containing 1 μM flg22 as described (Zhang et al., 2007). Luminescence was recorded by using GLOMAX 96 microplate luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI).

Flg22-protection assay

4- to 5-week-old plants were pre-treated with water or 1 μM flg22 1 day before infiltration with P. syringae DC3000 at a concentration of 1×106/ml, and bacterial population was determined 2 days after bacterial inoculation.

Plant protein extraction and co-immunoprecipitation assay

Total protein was extracted from ground transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings or protoplasts with protein extraction buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Trition-X 100, 1 mM DTT, proteinase inhibitor cocktail). Supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. Total protein was separated in SDS-PAGE gel and detected by immunoblot by using the indicated antibodies.

For immunoprecipitation in protoplasts, Arabidopsis protoplasts were transfected with 50–100 μg indicated plasmids, incubated overnight, and then treated with water or 1 μM flg22 for 10 min. Total protein was incubated with agarose-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 4 hr, washed 6 times with extraction buffer and eluted with 3× FLAG peptide (Sigma) for 30 min. The immunoprecipitates were separated in a SDS-PAGE gel and detected with immunoblot.

Mass spectrometric analyses for XLG2-interacting proteins and phosphosite detection

XLG2-FLAG plasmid was transfected into WT Arabidopsis protoplasts and incubated at room temperature for 14 hr. Total protein was extracted with IP buffer I (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/mL Dextran (Sigma), proteinase inhibitor cocktail) and the immunoprecipitation was performed as previously reported (Liu et al., 2009). To identify XLG2 phosphosites, protoplasts were treated with 1 μM flg22 for 10 min before extraction. Total protein was incubated with 70 μl agarose-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody for 4 hr, washed with IP buffer II (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, proteinase inhibitor cocktail) for 2 times, IP buffer III (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, proteinase inhibitor cocktail) for 2 times and eluted with 3× FLAG peptide for 45 min. The immunoprecipitates were separated in 10% NuPAGE gel (invitrogen) and subject to Mass Spectrometric analysis as previously described (Li et al., 2014).

GST pull-down and in vitro phosphorylation assays

For GST pull-down assay, GST-BIK1, GST-BIK1K105E, GST-FLS2KD and XLG2CT-HIS proteins were purified using the glutathione agarose beads and Ni-NTA agarose beads. 10 μg GST- and HIS-tagged proteins were incubated with 30 μl glutathione agarose beads in GST buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5) for 3 hr. The beads were washed 5–6 times with GST buffer and eluted with elution buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 15 mM GSH, pH 7.5). Samples were separated in SDS-PAGE gel and detected by anti-HIS immunoblot.

For in vitro phosphorylation assay, 200 ng HIS-BIK1 or HIS-BIK1K105E was incubated with 2 μg XLG21-203-HIS protein in the kinase reaction buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 100 mM ATP, pH 7.5) for 30 min. The phosphorylation of XLG21-203 was detected by autoradiograph (by adding γ-P32 ATP in kinase reaction buffer) or by immunoblot using phosphosite-specific antibodies.

Luciferase complementation assay

The coding sequences of indicated genes are cloned into pCAMBIA1300-35S-Cluc-RBS or pCAMBIA1300-35S-HA-Nluc-RBS and are introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. The assay was carried out as previously described (Chen et al., 2008), Agrobacterial strains carrying the indicated constructs were infiltrated into Nb leaves. Leaf discs were taken 2 days later, incubated with 1 mM luciferin in a 96-well plate for 5–10 min, and luminescence was recorded with the GLOMAX 96 microplate luminometer.

Phosphosite antibodies

XLG2 phosphosite-specific antibodies were produced by Abmart (China) as previous described (Li et al., 2014) using the following peptides:

| Immunization peptide | Control peptide | |

|---|---|---|

| p148 | -ADFRL(pS)PSSPL | -ADFRLSPSSPL |

| p150 | -FRLSP(pS)SPLSA | -FRLSPSSPLSA |

| p151 | -RLSPS(pS)PLSAS | -RLSPSSPLSAS |

In vitro protein degradation assay

In vitro protein degradation assay was performed as previous described (Wang et al., 2009) with slightly modification. 1-week-old seedlings of indicated genotype were ground in 200–300 μl extraction buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM PMSF, 5 mM DTT, and 10 mM ATP). Supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min and total protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad protein assay and adjusted to a final concentration of 1μg protein/μl. 300 ng recombinant HIS-BIK1 or PBL20-HIS protein was incubated with 100 μl total extract at 22°C, and equal amounts of samples were withdrawn at the indicated times for anti-HIS immunoblot analysis.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

4-week-old WT Arabidopsis plants were treated with flg22 for 0 hr and 3 hr and total RNA was extracted by using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript III RNA transcriptase (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Real-Time PCR was performed using and specific primers and SYBR Premix Ex Taq Kit (TaKaRa, Japan).

Oligonucleotide primers

Primers for Real-Time PCR:

ACT8-RT-F: 5'-TGTGACAATGGTACTGGAATGG-3'

ACT8-RT-R: 5'-TTGGATTGTGCTTCATCACC -3'

XLG1-RT-F: 5'-TGATGGTGAGGATTGTGAATTGA-3'

XLG1-RT-R: 5'-TTCCCAATCCGGTACTAACGG-3'

XLG2-RT-F: 5'-ATTGCTAATGTGCCACGAGCT-3'

XLG2-RT-R: 5'-ACGAGAGGTGCCACTGGGTAA-3'

XLG3-RT-F: 5'-CCGGTTGTGAAATTCAAACCTG-3'

XLG3-RT-R: 5'-TCCCTCTCTGTCTCTGCCTCC-3'

BIK1-HA-RT-F: 5'-CAGGACAACTTGGGAAAACCG-3'

BIK1-HA-RT-R: 5'-TAGGATCCTGCATAGTCCGGG-3'

Primers for site-directed mutagenesis

XLG2 (S141A)-F:

5'-ATGTACCAGAAGAAGTGAAAGCTCCTGCTGATTTTCGGTTATC-3'

XLG2 (S141A)-R:

5'-GATAACCGAAAATCAGCAGGAGCTTTCACTTCTTCTGGTACAT-3'

XLG2 (S148A)-F:

5'-TCCTGCTGATTTTCGGTTAGCACCATCATCACCATTGTCTG-3'

XLG2 (S148A)-R:

5'-CAGACAATGGTGATGATGGTGCTAACCGAAAATCAGCAGGA-3'

XLG2 (S150A/S151A)-F:

5'-GCTGATTTTCGGTTATCACCAGCAGCACCATTGTCTGCATCAGCGAGA-3'

XLG2 (S150A/S151A)-R:

5'-TCTCGCTGATGCAGACAATGGTGCTGCTGGTGATAACCGAAAATCAGC-3'

XLG2-3A (S148A/S150A/S151A)-F:

5'-AAAGTCCTGCTGATTTTCGGTTAGCACCAGCAGCACCATTGTCTGCATCAGCGAGA

GA-3'

XLG2-3A (S148A/S150A/S151A)-R:

5'-TCTCTCGCTGATGCAGACAATGGTGCTGCTGGTGCTAACCGAAAATCAGCAGGACT

TT-3'

XLG2-3D (S148D/S150D/S151D)-F:

5'-AAAGTCCTGCTGATTTTCGGTTAGACCCAGACGACCCATTGTCTGCATCAGCGAGA

GA-3'

XLG2-3D (S148D/S150D/S151D)-R:

5'-TCTCTCGCTGATGCAGACAATGGGTCGTCTGGGTCTAACCGAAAATCAGCAGGACT

TT--3'

XLG2 (S141D)-F:

5'-ATGTACCAGAAGAAGTGAAAGATCCTGCTGATTTTCGGTTATC-3'

XLG2 (S141D)-F:

5'-GATAACCGAAAATCAGCAGGATCTTTCACTTCTTCTGGTACAT-3'

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Yiji Xia for providing xlg2 and xlg3 mutants. Yuli Ding and Yufei Yu for technical assistance. JMZ was funded by the Natural Science Foundation China (Grant No. 31320103909), Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2015CB910201), Chinese Academy of Sciences (Strategic Priority Research Program Grant No. XDB11020200 and Joint Scientific Thematic Research Programme Grant No GJHZ1311), and State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics. YZ was funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (Grant No. 249922).

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

National Natural Science Foundation of China to Jian-Min Zhou.

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to Yuelin Zhang.

Chinese Academy of Sciences to Jian-Min Zhou.

Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China to Jian-Min Zhou.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Author contributions

XL, Designed and performed the majority of the experiments, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

PD, Designed and performed the majority of the experiments, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

KL, Contributed to the analyses of BIK1 stability in plants, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

JW, Performed in vitro protein degradation assays, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

MM, Performed part of the protein-protein interaction studies, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

LLi, Performed mass-spectrum analyses, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

LLi, Performed part of the protein-protein interaction studies, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

ML, Participated in the characterization of xlg2 mutant, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

XZ, Participated in the characterization of xlg2 mutant, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

SC, Performed mass-spectrum analyses, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

YZ, Coordinated the research and wrote the paper, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data.

J-MZ, Coordinated the research and wrote the paper, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data.

References

- Aranda-Sicilia MN, Trusov Y, Maruta N, Chakravorty D, Zhang Y, Botella JR. Heterotrimeric G proteins interact with defense-related receptor-like kinases in Arabidopsis. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2015;188:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommert P, Je BI, Goldshmidt A, Jackson D. The maize Gα gene COMPACT PLANT2 functions in CLAVATA signalling to control shoot meristem size. Nature. 2013;502:555–558. doi: 10.1038/nature12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty D, Gookin TE, Milner MJ, Yu Y, Assmann SM. Extra-large G proteins expand the repertoire of subunits in Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G protein signaling. Plant Physiology. 2015;169:512–529. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zou Y, Shang Y, Lin H, Wang Y, Cai R, Tang X, Zhou JM. Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiology. 2008;146:368–376. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JG, Gao Y, Jones AM. Differential roles of Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G-protein subunits in modulating cell division in roots. Plant Physiology. 2006;141:887–897. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JG, Willard FS, Huang J, Liang J, Chasse SA, Jones AM, Siderovski DP. A seven-transmembrane RGS protein that modulates plant cell proliferation. Science. 2003;301:1728–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.1087790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Li JF, Niu Y, Zhang XC, Woody OZ, Xiong Y, Djonović S, Millet Y, Bush J, McConkey BJ, Sheen J, Ausubel FM. Pathogen-secreted proteases activate a novel plant immune pathway. Nature. 2015;521:213–216. doi: 10.1038/nature14243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla D, Zipfel C, Robatzek S, Kemmerling B, Nürnberger T, Jones JD, Felix G, Boller T. A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature. 2007;448:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Pandey S, Assmann SM. Arabidopsis extra-large G proteins (XLGs) regulate root morphogenesis. The Plant Journal. 2008;53:248–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubiella U, Seybold H, Durian G, Komander E, Lassig R, Witte C-P, Schulze WX, Romeis T. Calcium-dependent protein kinase/NADPH oxidase activation circuit is required for rapid defense signal propagation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:8744–8749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221294110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heese A, Hann DR, Gimenez-Ibanez S, Jones AME, He K, Li J, Schroeder JI, Peck SC, Rathjen JP. The receptor-like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:12217–12222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705306104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa A. The Arabidopsis G-protein beta-subunit is required for defense response against agrobacterium tumefaciens. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 2009;73:47–52. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AM, Ecker JR, Chen JG. A reevaluation of the role of the heterotrimeric G protein in coupling light responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2003;131:1623–1627. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.017624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota Y, Sklenar J, Derbyshire P, Stransfeld L, Asai S, Ntoukakis V, Jones JD, Shirasu K, Menke F, Jones A, Zipfel C. Direct regulation of the NADPH oxidase RBOHD by the PRR-associated kinase BIK1 during plant immunity. Molecular Cell. 2014;54:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YR, Assmann SM. Arabidopsis thaliana 'extra-large GTP-binding protein' (AtXLG1): a new class of G-protein. Plant Molecular Biology. 1999;40:55–64. doi: 10.1023/A:1026483823176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L LM, Yu L, Zhou Z, Liang X, Liu Z, Cai G, Gao L, Zhang X, Wang Y, Chen S, Zhou JM. The FLS2-associated kinase BIK1 directly phosphorylates the NADPH oxidase RbohD to control plant immunity. Cell Host&Microbe. 2014;15:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Ding P, Sun T, Nitta Y, Dong O, Huang X, Yang W, Li X, Botella JR, Zhang Y. Heterotrimeric G proteins serve as a converging point in plant defense signaling activated by multiple receptor-like kinases. Plant Physiology. 2013;161:2146–2158. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.212431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Elmore JM, Fuglsang AT, Palmgren MG, Staskawicz BJ, Coaker G. RIN4 functions with plasma membrane H+-ATPases to regulate stomatal apertures during pathogen attack. PLoS Biology. 2009;7:e13568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente F, Alonso-Blanco C, Sánchez-Rodriguez C, Jorda L, Molina A. ERECTA receptor-like kinase and heterotrimeric G protein from arabidopsis are required for resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Plectosphaerella cucumerina. The Plant Journal. 2005;43:165–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorek J, Griebel T, Jones AM, Kuhn H, Panstruga R. The role of Arabidopsis heterotrimeric G-protein subunits in MLO2 function and MAMP-triggered immunity. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions : MPMI. 2013;26:991–1003. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-13-0077-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Lin W, Gao X, Wu S, Cheng C, Avila J, Heese A, Devarenne TP, He P, Shan L. Direct ubiquitination of pattern recognition receptor FLS2 attenuates plant innate immunity. Science. 2011;332:1439–1442. doi: 10.1126/science.1204903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Wu S, Gao X, Zhang Y, Shan L, He P. A receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase, BIK1, associates with a flagellin receptor complex to initiate plant innate immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:496–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909705107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Dai X, Xu Y, Luo W, Zheng X, Zeng D, Pan Y, Lin X, Liu H, Zhang D, Xiao J, Guo X, Xu S, Niu Y, Jin J, Zhang H, Xu X, Li L, Wang W, Qian Q, Ge S, Chong K. COLD1 confers chilling tolerance in rice. Cell. 2015;160:1209–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho AP, Zipfel C. Plant PRRs and the activation of innate immune signaling. Molecular Cell. 2014;54:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruta N, Trusov Y, Brenya E, Parekh U, Botella JR. Membrane-localized extra-large G proteins and Gbg of the heterotrimeric G proteins form functional complexes engaged in plant immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2015;167:1004–1016. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.255703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCudden CR, Hains MD, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP, Willard FS. G-protein signaling: back to the future. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2005;62:551–577. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4462-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan J, Matschi S, Shorinola O, Rovenich H, Matei A, Segonzac C, Malinovsky FG, Rathjen JP, MacLean D, Romeis T, Zipfel C. The calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK28 buffers plant immunity and regulates BIK1 turnover. Cell Host&Microbe. 2014;16:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara Y, Kaya H, Hiraoka G, Yumoto F, Kimura S, Kadota Y, Hishinuma H, Senzaki E, Yamagoe S, Nagata K, Nara M, Suzuki K, Tanokura M, Kuchitsu K. Synergistic activation of the Arabidopsis NADPH oxidase AtrbohD by Ca2+ and phosphorylation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:8885–8892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham WM, Hamm HE. Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 2008;9:60–71. doi: 10.1038/nrm2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S, Chen JG, Jones AM, Assmann SM. G-protein complex mutants are hypersensitive to abscisic acid regulation of germination and postgermination development. Plant Physiology. 2006;141:243–256. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Sun H, Qian Q, Wu K, Luo J, Wang S, Zhang C, Ma Y, Liu Q, Huang X, Yuan Q, Han R, Zhao M, Dong G, Guo L, Zhu X, Gou Z, Wang W, Wu Y, Lin H, Fu X. Heterotrimeric G proteins regulate nitrogen-use efficiency in rice. Nature Genetics. 2014;46:652–656. doi: 10.1038/ng.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Li L, Macho AP, Han Z, Hu Z, Zipfel C, Zhou JM, Chai J. Structural basis for flg22-induced activation of the Arabidopsis FLS2-BAK1 immune complex. Science. 2013;342:624–628. doi: 10.1126/science.1243825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddese B, Upton GJ, Bailey GR, Jordan SR, Abdulla NY, Reeves PJ, Reynolds CA. Do plants contain g protein-coupled receptors? Plant Physiology. 2014;164:287–307. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.228874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MA, Morales J, Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Molina A, Dangl JL. Functional interplay between Arabidopsis NADPH oxidases and heterotrimeric G protein. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions : MPMI. 2013;26:686–694. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-12-0236-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov Y, Rookes JE, Chakravorty D, Armour D, Schenk PM, Botella JR. Heterotrimeric G proteins facilitate arabidopsis resistance to necrotrophic pathogens and are involved in jasmonate signaling. Plant Physiology. 2006;140:210–220. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.069625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusov Y, Rookes JE, Tilbrook K, Chakravorty D, Mason MG, Anderson D, Chen JG, Jones AM, Botella JR. Heterotrimeric G protein gamma subunits provide functional selectivity in Gbetagamma dimer signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;4:1235–1250. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah H, Chen JG, Temple B, Boyes DC, Alonso JM, Davis KR, Ecker JR, Jones AM. The beta-subunit of the Arabidopsis G protein negatively regulates auxin-induced cell division and affects multiple developmental processes. The Plant Cell. 2003;15:393–409. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah H, Chen JG, Young JC, Im KH, Sussman MR, Jones AM. Modulation of cell proliferation by heterotrimeric G protein in Arabidopsis. Science. 2001;292:2066–2069. doi: 10.1126/science.1059040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano D, Jones AM. Heterotrimeric G protein-coupled signaling in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2014;65:365–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Zhu D, Huang X, Li S, Gong Y, Yao Q, Fu X, Fan LM, Deng XW. Biochemical insights on degradation of Arabidopsis DELLA proteins gained from a cell-free assay system. The Plant Cell. 2009;21:2378–2390. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.065433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XQ, Ullah H, Jones AM, Assmann SM. G protein regulation of ion channels and Abscisic acid signaling in arabidopsis guard cells. Science. 2001;292:2070–2072. doi: 10.1126/science.1059046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warpeha KM, Lateef SS, Lapik Y, Anderson M, Lee BS, Kaufman LS. G-protein-coupled receptor 1, G-protein Galpha-subunit 1, and prephenate dehydratase 1 are required for blue light-induced production of phenylalanine in etiolated Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2006;140:844–855. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.071282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Li W XT, Liu Z, Laluk K, Ding X, Zou Y, Gao M, Zhang X, Chen S, Mengiste T, Zhang Y, Zhou JM. Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases integrate signaling from multiple plant immune receptors and are targeted by a Pseudomonas syringae effector. Cell Host & Microbe. 2010;7:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shao F, Li Y, Cui H, Chen L, Li H, Zou Y, Long C, Lan L, Chai J, Chen S, Tang X, Zhou J-M. A pseudomonas syringae effector inactivates mapks to suppress pamp-induced immunity in plants. Cell Host & Microbe. 2007;1:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Li GJ, Ding L, Cui X, Berg H, Assmann SM, Xia Y. Arabidopsis extra large G-protein 2 (XLG2) interacts with the Gbeta subunit of heterotrimeric G protein and functions in disease resistance. Molecular Plant. 2009;2:513–525. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]