Abstract

Limited research has examined polysubstance use profiles among young adults focusing on the various tobacco products currently available. We examined use patterns of various tobacco products, marijuana, and alcohol using data from the baseline survey of a multiwave longitudinal study of 3418 students aged 18-25 recruited from seven U.S. college campuses. We assessed sociodemographics, individual-level factors (depression; perceptions of harm and addictiveness,), and sociocontextual factors (parental/friend use). We conducted a latent class analysis and multivariable logistic regression to examine correlates of class membership (Abstainers were referent group). Results indicated five classes: Abstainers (26.1% per past 4-month use), Alcohol only users (38.9%), Heavy polytobacco users (7.3%), Light polytobacco users (17.3%), and little cigar and cigarillo (LCC)/hookah/marijuana co-users (10.4%). The most stable was LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users (77.3% classified as such in past 30-day and 4-month timeframes), followed by Heavy polytobacco users (53.2% classified consistently). Relative to Abstainers, Heavy polytobacco users were less likely to be Black and have no friends using alcohol and perceived harm of tobacco and marijuana use lower. Light polytobacco users were older, more likely to have parents using tobacco, and less likely to have friends using tobacco. LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users were older and more likely to have parents using tobacco. Alcohol only users perceived tobacco and marijuana use to be less socially acceptable, were more likely to have parents using alcohol and friends using marijuana, but less likely to have friends using tobacco. These findings may inform substance use prevention and recovery programs by better characterizing polysubstance use patterns.

Keywords: Substance use, Young adults, Risk factors, Tobacco use, Marijuana use

2. INTRODUCTION

Young adults are at the greatest risk for using various substances.1 Since 2013, there has been an increasing interest in polysubstance use among young adults globally.2-6 Young adulthood, particularly the transition to college, is a critical period for engaging in many health compromising behaviors, including substance use.7-10 Among young adults, polysubstance use patterns have changed little over recent years,11 potentially suggesting that use of certain drugs may occur in the context of other drug use.12

Three of the most commonly used substances among young adults in the U.S. are tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol.13 Cigarettes continue to be the main source of tobacco use in the U.S., including among young adults.14,15 Notably, most research prior to the past four years has focused on cigarettes. Recently, however, various alternative tobacco products, including little cigars and cigarillos (LCCs), smokeless tobacco (i.e., chew, snus, dissolvable tobacco), and electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have been introduced to the U.S. market, while waterpipes or hookahs have increased in popularity.16,17 These products may especially appeal to youth due to their attractive packaging, flavoring, dissolvable delivery systems,1 and social appeal.18-20 These products have significantly altered the terrain of tobacco use behavior and are often misperceived as safe among young adults.21

Marijuana has been the most common illicit substance used in the U.S. for several decades,22,23 and its use has increased among young adults,24 with 19.1% of young adults ages 18-25 reporting past month marijuana use in 2013.25 Marijuana use has dramatically increased in young adults in recent years largely due to increased legalization and decriminalization of marijuana in the U.S.26 and increasing social acceptability. 27,28 Also of relevance to the current study is the common co-use of tobacco and marijuana.29,30 The changing tobacco market may have also changed how marijuana is used,31 as users of hookah and LCCs may use the same materials (e.g., papers, waterpipe) to consume marijuana.32

Alcohol is by far the most commonly used substance in young adults, with roughly 60% of U.S. young adults consuming alcohol in the past month.33 According to the 2013 National College Health Assessment,34 roughly 30% of college students reported drinking at least six of the past 30 days, and about 40% reported consuming at least five drinks the last time they “partied.”

Research on concurrent or co-use of these substances is needed to understand use and couse patterns among young adults. This is critical, as using these substances during this developmental period may lead to lifelong impairments in brain function or establishment of negative health behaviors ultimately increasing risk of various diseases and illnesses. For example, co-use of marijuana and alcohol increases risk for motor vehicle crashes,35,36 short- and long-term memory impairment,37 psychological disorders,38,39 and lower educational performance and attainment.40-43 Tobacco and marijuana use increases the risk for adverse respiratory and cardiovascular effects44-48 and increased susceptibility to cancer.49 These are only a small number of the negative consequences of using these substances in young adulthood.

Drawing from a socioecological framework,50 several sociodemographic, individual-level, and sociocontextual factors might contribute to substance use.51 First, substance use has been associated with several sociodemographic factors. For example, being male is associated with greater substance use, and racial/ethnic differences also exist in relation to use across substances.52,53

Second, from a more theoretical perspective, individual-level constructs drawn from the Theory of Planned Behavior54,55 and Health Belief Model56,57 are associated with substance use. More positive attitudes toward use, decreased perceived risk of substance use, and greater social acceptability of use have been related to use of tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol. 21,51 Moreover, increased depressive symptoms are associated with substance use.51,58-60

Third, social factors play an important role. Those with parents, friends, and other social influences who use a range of substances are more likely to be substance users themselves, with the types of substances used being similar to those they are most frequently exposed to.21,51 In addition, relational and household factors (e.g., having children living in the home51) might be associated with substance use.

Given the risks associated with substance use, changing terrain of tobacco products available in the market, and changing landscape of marijuana use policies and social norms, this study aimed to examine: 1) profiles of substance use behaviors among young adult college students, with particular focus on use of various tobacco products, marijuana, and alcohol; and 2) sociodemographic, individual-level, and sociocontextual-level factors associated with use profiles among this sample.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Procedure and Participants

The parent study, entitled Project DECOY (Documenting Experiences with Cigarettes and Other Tobacco in Youth), was approved by the Emory University and ICF International Institutional Review Boards as well as those of the participating colleges. Project DECOY is a sequential mixed-methods61 longitudinal panel study of 3418 college students ages 18 to 25 from seven colleges in Georgia. The colleges include two public universities/colleges, two private universities, two community/technical colleges, and a historically black university located in rural and urban settings. Detailed information on this study is under review elsewhere.62 Data collection began in Fall 2014 and consists of self-report assessments every four months for two years (during Fall, Spring, and Summer). Current analyses draw from the baseline data collected in Fall 2014. For the current latent class analysis (LCA), we included all 3418. The multivariable analyses focused on the 3193 (93.4%) with complete data on the potential correlates involved in this analyses.

3.2 Measures

Manifest variables for the LCA were chosen to represent five distinct tobacco products: cigarettes, LCCs, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, and hookah. In addition, we included marijuana and alcohol use. Participants were asked to indicate yes or no to the following assessment: “For each of the following products, indicate if you have ever tried them in your lifetime” for each tobacco product, marijuana, and alcohol. Photos of the various tobacco products were also provided. Those who indicated lifetime use of each substance were subsequently asked, “In the past 4 months, on how many days have you used each of the following products?” with answer choices ranging from 0 to 120. Those who indicated any use in the past 4 months were then asked, “How many days of the past 30 days did you use [product X]?” with answer choices ranging from 0 to 30. All manifest variables were created by dichotomizing any versus no use in the past 4 months and any versus no use in the past 30 days.

Sociodemographic data collected included age, sex, race, and ethnicity.

At the individual level, we assessed depressive symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 item (PHQ-9).63 Cronbach's alpha for the PHQ-9 in the current study was 0.86. It was scored as the sum of items. We also asked about perceptions of tobacco products (regular cigarettes, LCCs, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, hookah) and marijuana on a Likert scale of 1=not at all to 7=extremely. This included perceptions about harmfulness of product use, addictiveness, and social acceptability.21 For each domain, an aggregate score was created by taking the average score across products. Cronbach's alphas for harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability were 0.73, 0.92, and 0.83, respectively.

At the sociocontextual level, we asked about place of primary residence and children living in that residence. We also asked if any parent currently used each of the tobacco products, marijuana, or alcohol, respectively,21 and how many of their five closest friends currently used each product, respectively.21 Except for alcohol use, the items related to friends’ use were dichotomized as at least one friend used versus none. For alcohol use, the distribution indicated three categories: no friends, some friends, or all friends use alcohol.

3.3 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics of sociodemographics and tobacco use characteristics were calculated. For the LCA, we investigated use patterns for the past 4 months and past 30 days. We analyzed the past 4 month data first due to higher prevalence of use across products. We investigated a succession of LCA models starting with the most parsimonious one-class model, which assumed that all college students’ use patterns were the same, followed by models assuming two to six classes to find the most parsimonious model that provided an adequate fit to the data. We used the Akaike information criterion (five-class model) and Bayesian information criterion (four-class model) as well as class membership distribution to decide on the five-class model presented. We assumed a five-class model for past 30 day use, which was confirmed by the Akaike information criterion. We then examined stability of class membership across the past 4 month and past 30 day time frames. Finally, multinomial logistic regression, including sociodemographic, individual-level, and sociocontextual characteristics, was conducted to compare class membership in each of the four classes to a reference class (the Abstainers). Descriptive analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4. LCA and multinomial regression analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.3. All analyses account for clustering of students within schools.

4. RESULTS

4.1 Participant Characteristics

Descriptive statistics regarding sociodemographic, individual-level, and sociocontextual factors are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic, individual-level, and sociocontextual factors

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Age (SD) | 20.5 | 1.97 |

| Sex (%) | N | % |

| Male | 1215 | 35.6 |

| Female | 2199 | 64.3 |

| Other | 4 | 0.1 |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 2133 | 63.2 |

| Black | 832 | 24.6 |

| Other | 411 | 12.2 |

| Hispanic (%) | 255 | 7.5 |

| College year (%) | ||

| First | 899 | 26.3 |

| Second | 821 | 24.0 |

| Third | 724 | 21.2 |

| Fourth | 579 | 16.9 |

| Fifth or more | 395 | 11.6 |

| Parental education (%) | ||

| High school/GED/ or less | 589 | 17.5 |

| Some college/Associate's/Bachelor's | 1876 | 55.6 |

| Master's/Doctoral degree | 908 | 26.9 |

| Born in the U.S. (%) | 3161 | 92.5 |

| Individual-level factors | Mean | SD |

| Depression score (PHQ-9) (SD) | 6.34 | 5.38 |

| Perceptions of tobacco/marijuana (SD) | ||

| Harm of product use score | 4.00 | 1.93 |

| Addictiveness score | 5.21 | 1.49 |

| Social acceptability score | 3.75 | 1.80 |

| Sociocontextual factors | ||

| Relationship status (%) | N | % |

| Single/never married/divorced/separated | 3066 | 89.7 |

| Married/living with significant other | 349 | 10.21 |

| Primary residence (%) | ||

| On campus | 1493 | 43.7 |

| At home/with parents | 819 | 24.0 |

| Other off-campus | 1101 | 32.2 |

| Children in the household (%) | 587 | 17.2 |

| Parental substance use (%) | ||

| Tobacco | 1107 | 32.4 |

| Marijuana | 215 | 6.3 |

| Alcohol | 1855 | 54.3 |

| Friends’ substance use (%) | ||

| Tobacco | 2307 | 67.5 |

| Marijuana | 1741 | 50.9 |

| Alcohol (%) | ||

| None | 452 | 13.2 |

| Some | 1515 | 44.3 |

| All | 1451 | 42.5 |

4.2 Tobacco Product Use Prevalence

Past 4 month use of cigarettes (15.6%) was lower than use of hookah (21.5%), LCCs (20.1%), and e-cigarettes (16.5%; Table 2). However, cigarettes (13.4%) were the most commonly used tobacco product in the past 30 days. All tobacco product use was surpassed by the use of alcohol and marijuana in the past 4 and the past 30 days. Furthermore, more than 40% reported use of at least one tobacco product in the past 4 months, and nearly 30% had used at least one tobacco product in the last 30 days. In the past 4 months and past 30 days, many reported polytobacco use.

Table 2.

Use prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana, past 4 months and 30 days

| Past 4 months | Past 30 days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco product | N | % | N | % |

| Cigarettes | 534 | 15.6 | 806 | 13.4 |

| LCCs | 688 | 20.1 | 385 | 11.3 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 168 | 4.9 | 123 | 3.6 |

| E-cigarettes | 563 | 16.5 | 372 | 10.9 |

| Hookah | 734 | 21.5 | 416 | 12.2 |

| Marijuana | 808 | 23.6 | 648 | 19.0 |

| Alcohol | 2431 | 71.1 | 2155 | 63.1 |

| Polytobacco use | ||||

| Any tobacco product | 1374 | 40.2 | 1012 | 29.6 |

| 1 product only | 599 | 17.5 | 536 | 15.7 |

| 2 products | 412 | 12.1 | 274 | 8.0 |

| 3 products | 220 | 6.4 | 150 | 4.4 |

| 4 products | 111 | 3.3 | 43 | 1.3 |

| 5 products | 32 | 0.9 | 9 | 0.3 |

4.3 LCA Results

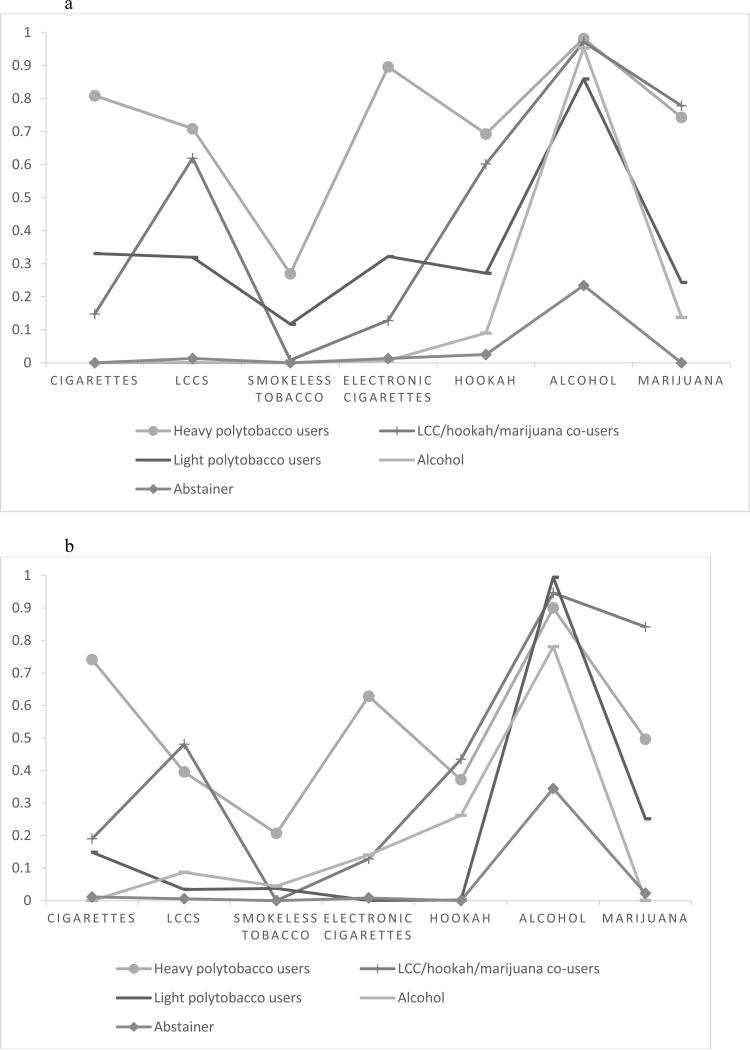

The LCA indicated five distinct classes (Figure 1). A significant portion reported no use of any substances (the “Abstainers”; 20.8% and 28.8% of the sample for past 4 months and 30 days, respectively). Another large class is characterized by use of “Alcohol only” (35.5% in past 4 months, 37.9% in past 30 days). The remaining three classes are characterized by different patterns of tobacco and marijuana use: “Light polytobacco users” (20.2% in past 4 months; 15.5% in past 30 days); “Heavy polytobacco users” (12.2% in past 4 months; 8.9% in past 30 days); and “LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users” (11.3% in past 4 months; 9.1% in past 30 days).

Figure 1.

a: Graphical display of item-response probabilities for past 4 month substance use

Figure 1b: Graphical display of item-response probabilities for past 30 day substance use

4.4 Stability of Class Membership

Classes were somewhat unstable when comparing past 4 month and past 30 day use (Table 3). For the past 30 days, the majority (65.9%) were classified as Abstainers. This is more than double the number classified as Abstainers based on past 4 month use (26.1%). Based on past 4 month use, most of the 30 day Abstainers were classified as using Alcohol only but not tobacco products or marijuana. However, 7.5% of 30 day Abstainers were classified as Light polytobacco users and 1.9% as LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users based on past 4 month use. The most stable class was the LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users. Of those classified as such based on past 30 day use, 77.3% were also classified as such based on past 30 day use; however, 20.7% were classified as Light polytobacco users and 13.4% were classified as Heavy polytobacco users. The Heavy polytobacco user class was the second most stable class; 53.2% of past 30 day Heavy polytobacco users were also identified as such per past 4 months use.

Table 3.

Class membership based on past 4 month use compared to past 30 day use

| Classes for past 30 day use |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % past 4 months | Heavy poly-tobacco users | Light poly-tobacco users | LCC/ hookah/ marijuana users | Alcohol users | Abstainers | ||

| Classes for past 4 month use | % past 30 days | 100.0 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 65.9 |

| Heavy polytobacco users | 7.3 | 53.2 | 5.7 | 20.3 | 3.1 | 0.1 | |

| Light polytobacco users | 17.3 | 43.4 | 41.4 | 2.3 | 54.0 | 7.5 | |

| LCC/ hookah/ marijuana users | 10.4 | 3.5 | 20.7 | 77.3 | 13.4 | 1.9 | |

| Alcohol users | 38.9 | 0.0 | 32.1 | 0.0 | 21.1 | 51.9 | |

| Abstainers | 26.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.4 | 38.6 | |

Note: Column % should total 100.0%, indicating % of proportion of class across each category. For example, 53.2% of Heavy polytobacco users defined by past 30 day use were also categorized as such within the past 4 months, with 43.4% being recategorized as Light polytobacco users and 3.5% being recategorized as LCC/hookah/marijuana users within the past 4 month time frame.

4.5 Indicators of Class Membership

Table 4 presents the results from the multinomial regression analysis identifying correlates of class membership; the referent group was the Abstainers. Relative to Abstainers, Heavy polytobacco users were less likely to be Black (OR=0.81, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.69, 0.94, p=.006), rated the harm of tobacco and marijuana use lower (OR=0.93, CI 0.88, 0.97, p=.003), and were less likely to have no friends who used alcohol (OR=0.72, CI 0.53, 0.97, p=.01). Compared to Abstainers, Light polytobacco users were older (OR=1.07, CI 1.03, 1.11, p=.001), were more likely to have parents who use tobacco (OR=1.36, CI 1.16, 1.59, p<.001), and were less likely to have friends who use tobacco (OR=0.83, CI 0.76, 0.90, p<.001). Versus Abstainers, the LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users were older (OR=1.10, CI 1.03, 1.17, p=.005) and were more likely to have parents who use tobacco (OR=1.27, CI 1.12, 1.45, p<.001). Compared to Abstainers, Alcohol only users perceived tobacco and marijuana use to be less socially acceptable (OR=0.97, CI 0.95, 0.99, p=.03), were more likely to have parents who use alcohol (OR=1.18, CI 1.01, 1.37, p=.03), were less likely to have friends who use tobacco (OR=0.85, CI 0.74, 0.97, p=.002), but were more likely to have friends who use marijuana (OR=1.14, CI 1.06, 1.22, p=.001).

Table 4.

Covariates of class assignment per past 4 month use patterns compared to Abstainers (N=3193)

| Heavy polytobacco users |

Light polytobacco users |

LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users |

Alcohol only |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | OR | p-value |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||

| Age | 1.01 | .83 | 1.07 | .001 | 1.10 | .005 | 1.04 | .21 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.85 | .23 | 0.87 | .30 | 1.01 | .97 | 0.94 | .61 |

| Race (ref White) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.81 | .006 | 0.87 | .13 | 1.17 | .27 | 0.84 | .06 |

| Other race | 1.08 | .71 | 1.22 | .15 | 1.08 | .46 | 0.94 | .65 |

| Ethnicity (1 = Latino) | 1.30 | .31 | 1.04 | .87 | 0.80 | .27 | 0.98 | .89 |

| Individual-level factors | ||||||||

| Depression score | 0.98 | .16 | 0.99 | .13 | 1.01 | .32 | 0.99 | .57 |

| Harm of product use score | 0.93 | .003 | 0.98 | .51 | 0.97 | .52 | 0.97 | .41 |

| Addictiveness score | 0.96 | .33 | 0.96 | .24 | 1.01 | .71 | 0.99 | .78 |

| Social acceptability score | 0.99 | .77 | 1.00 | .90 | 0.98 | .31 | 0.97 | .03 |

| Sociocontextual factors | ||||||||

| Children in the household (1 = Yes) | 0.73 | .07 | 0.90 | .35 | 0.84 | .13 | 0.89 | .06 |

| Lives on campus (1 = Yes) | 0.98 | .84 | 1.04 | .75 | 0.93 | .65 | 1.16 | .21 |

| Parent uses tobacco (1=Yes) | 1.11 | .61 | 1.36 | <.001 | 1.27 | <.001 | 1.10 | .23 |

| Parent uses marijuana (1=Yes) | 0.90 | .78 | 0.86 | .65 | 0.94 | .68 | 0.94 | .67 |

| Parent uses alcohol (1=Yes) | 0.95 | .84 | 1.07 | .21 | 1.13 | .30 | 1.18 | .03 |

| Friends use tobacco (1=Yes) | 0.85 | .15 | 0.83 | <.001 | 1.06 | .53 | 0.85 | .015 |

| Friends use marijuana (1=Yes) | 1.08 | .65 | 1.05 | .60 | 0.95 | .69 | 1.14 | .001 |

| Friends use alcohol (Ref = some) | ||||||||

| none | 0.72 | .03 | 0.69 | .11 | 0.76 | .08 | 0.75 | .12 |

| all | 1.16 | .21 | 1.17 | .11 | 0.76 | .08 | 1.13 | .22 |

5. DISCUSSION

Five distinct categories of young adult college students were identified in relation to substance use behavior profiles. The largest two groups for past 4 month and past 30 day time frames were Alcohol only users and Abstainers, respectively. The other three groups identified were Heavy polytobacco users, Light polytobacco users, and LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users. One important finding is that the classification by group was relatively unstable, potentially indicating that young adult college students may not have established and consistent substance use habits. The Abstainer group was larger in the past 30 day analysis than in the past 4 month use analysis, with the majority of those that were regrouped being categorized as Alcohol only users for the 4 month time frame. The LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users were the most consistent in use behaviors, with over three-quarters consistently categorized versus 50% or less for other groups. Heavy polytobacco users were also relatively consistent, potentially indicating the role of addiction over time. Notably, for the 4-month window, the greatest proportion of reclassified LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users were classified as Light polytobacco users. Those who transitioned to Light polytobacco users from the 30 day time frame to the 4 month time frame were largely Alcohol only users, potentially indicating experimentation with or social use of these tobacco products.

A range of sociodemographic, individual-level, and sociocontextual factors were associated with substance use behaviors relative to abstainers. The Heavy polytobacco user category was distinct because of the high rates of use of various tobacco products along with the highest rates of marijuana and alcohol use. Thus, they demonstrated the highest risk behavior \ of any group. Versus Abstainers, Heavy polytobacco users were less likely to be Black, perceived less harm of tobacco and marijuana use, and were less likely to have friends who did not use alcohol. The findings related to race are consistent with prior research indicating that Blacks are less likely to use certain tobacco products (e.g., cigarettes, chew) and alcohol.51 The findings regarding perceived harm are also expected.21,51 Additionally, the lower likelihood of having friends abstinent from alcohol, which is reasonable given that having friends who use substances is a risk factor for substance use.21,51

Light polytobacco users were distinct in their substance use, as they demonstrated some use of the range of tobacco products, also engaged in alcohol consumption, but had relatively low rates of marijuana use. Compared to Abstainers, Light polytobacco users were older and more likely to have parents who use tobacco. These findings may reflect greater opportunity to have experimented with tobacco and to have lived in an environment where tobacco use exposure and experimentation with a diversity of products were more normative.51,64 However, they were less likely to have friends who use tobacco, which might indicate that their current social network might be protective against heavy tobacco use.

The LCCs/hookah/marijuana co-users are interesting. Prior research has indicated high co-use of these products, which might indicate use in the same apparatus and/or in similar social contexts.31,32 Versus Abstainers, LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users were older and more likely to have parents who use tobacco. Again, these findings might indicate greater exposure to tobacco products in their home settings and more time to experiment with tobacco products.64

Finally, one of the largest classes was the Alcohol only user group. Compared to Abstainers, Alcohol only users were more likely to have parents who use alcohol and perceived tobacco and marijuana use to be less socially acceptable, which aligns with theory54 and prior literature21,51 regarding risk and protective factors for use of different substances. Moreover, Alcohol only users were less likely to have friends who use tobacco but were more likely to have friends who use marijuana. We might expect alcohol users to have greater exposure to friends using the range of substances compared to those who abstain.21,51 The finding regarding lower prevalence of tobacco use among their social network is difficult to interpret, especially because alcohol and tobacco use frequently co-occur, and warrants future research.

In general, it is important to note that, despite the fact that our selection of key predictor variables was based on the literature, some anticipated associations were not found. For example, level of depressive symptoms did not differentiate any of the groups versus Abstainers. Another unanticipated null finding was in relation to perceived addictiveness of tobacco and marijuana. These null findings might be related to differences between use and abuse of substances, particularly among the young adult population, where some of these use patterns might be transient. In addition, several of the social influence factors demonstrated null results in relation to substance use group. For example, peer marijuana use did not significantly contrast the LCC/hookah/marijuana using group from the Abstainers, but it does contrast the Alcohol only group versus Abstainers. One reason for this may be that these measures were dichotomized and had range restrictions, thus limiting sensitivity to detecting group differences.

The current findings have implications for research and practice. First, subsequent research should examine how these classes transition in their substance use behaviors over time. The relative instability of some classes across 30-day and 4-month timeframes suggests that there may be reliable change in transitional classes (e.g., movers vs. stayers) and predictors of these changes across longer time intervals (e.g., one to two years). Qualitative research should also examine the experiences of and reasons for use, as well as patterns of use among these different substance use categories, particularly those that are nuanced such as the polytobacco groups and the LCC/hookah/marijuana co-user group. More broadly, latent class analyses should be included in substance use research to identify the patterns and sequence of using substances, evaluate predictors of transitions in use patterns, make statistical comparisons for substance use patterns across important variables (e.g., ethnic group, gender), and determine transitional patterns associated with interventions. In practice, more progressive policies are needed to decrease access to tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol among young adults to decrease early initiation and transitions to use of these substances. Campus-based services must also exist to promote abstinence and aid in recovery among those struggling with addiction. Moreover, clinicians, particularly those in campus-based settings, must assess use of the range of tobacco products – not just cigarettes – as well as marijuana and alcohol on a systematic basis.

This study has some limitations. First, the study sample, drawn from colleges/universities in Georgia and is subject to selection bias, may not generalize to all young adults; however, our sample is diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, geographic location (urban vs. rural), and socioeconomic backgrounds. Second, although our scope of measures may not be inclusive of all potentially important measures related to substance use, the measures selected were drawn from the literature relevant to tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol use in this population. Third, the cross-sectional design limits the extent to which we can make causal attributions or determine intra-individual trajectories of substance use over time. Subsequent multiwave analyses will enable us to address this issue using the results from this cross-sectional analysis to guide subsequent analyses and correlates of interest. These analyses are also limited by the self-report nature of the assessments. In particular, substance use is often underreported, especially for more recent time periods, and may be particularly underreported by some subgroups of the sample. Additionally, whether or not the participant was aware of the substance use of others (e.g., parents or friends) is a limitation of the data. Finally, given the transient nature of young adults between and within the academic year, there may have been transitions that are not accounted for in this cross-sectional analyses. Future analyses using longitudinal data can address the impact of changing residential circumstances on substance use over time.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Five distinct categories of substance use behaviors were identified within a sample of young adult college students. The largest two groups were Alcohol only users and Abstainers. The other three groups identified varied in their level of tobacco and marijuana use. These groups were also somewhat unstable when examining group membership from a past 4 month to a past 30 day time frame, indicating rapid transitions among some subgroups. However, less rapid transitioning was seen in others, particularly the Heavy polytobacco users and the LCC/hookah/marijuana co-users, indicating some level of addiction contributing to consistent use. These five groups were distinct in terms of sociodemographic, individual-level, and sociocontextual factors.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Five categories of young adults were identified in relation to substance use.

These groups were distinct in terms of sociodemographic and risk factors.

The instability of these groups suggest rapid transitions in substance use patterns.

Heavy poly-substance users were the most consistent, perhaps due to addiction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our Campus Advisory Board members across the state of Georgia in developing and assisting in administering this survey. We also would like to thank ICF Macro for their scientific input and technical support in conducting this research.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA179422-01; PI: Berg) and the Georgia Cancer Coalition (PI: Berg).

7. ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE

The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

8. CONTRIBUTORS

Berg, Windle, Lewis, and Haardörfer designed the study and wrote the protocol. Haardörfer conducted the analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Berg wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

9. CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.McMillen R, Maduka J, Winickoff J. Use of emerging tobacco products in the United States. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:989474. doi: 10.1155/2012/989474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiauzzi E, Dasmahapatra P, Black RA. Risk behaviors and drug use: a latent class analysis of heavy episodic drinking in first-year college students. Psychology of addictive behaviors : journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(4):974–985. doi: 10.1037/a0031570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter JL, Strang J, Frissa S. Comparisons of polydrug use at national and inner city levels in England: associations with demographic and socioeconomic factors. Annals of Epidemiology. 2013;23:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quek LH, Chan GC, White A, et al. Concurrent and simultaneous polydrug use: latent class analysis of an Australian nationally representative sample of young adults. Frontiers in public health. 2013;1:61. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armour C, Shorter GW, Elhai JD. Polydrug use typologies and childhood maltreatment in a nationally representative survey of Danish young adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:170–178. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia de Oliveira L, Alberghini DG, dos Santos B, Guerra de Andrade A. Polydrug use among college students in Brazil: a nationwide survey. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35:221–230. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-0775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Department of Health and Human Services OoAS; p. ed2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigotti NA, Lee JE, Wechsler H. US college students' use of tobacco products: results of a national survey. JAMA. 2000;284(6):699–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2002;S14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in alcohol use, related problems and experience of prevention efforts among U.S. college students 1993-2001: Results from the 2001 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly AB, Chan GC, White A, Saunders JB, Baker PJ, Connor JP. Is there any evidence of changes in patterns of concurrent drug use among young Australians 18-29 years between 2007 and 2010? Addictive behaviors. 2014;39(8):1249–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly AB, O'Flaherty M, Connor JP, et al. The influence of parents, siblings and peers on pre- and early-teen smoking: a multilevel model. Drug and alcohol review. 2011;30(4):381–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Prevalence and Trends Data. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigotti N, Lee JE, Wechsler H. US college students’ use of tobacco products: Results of a national survey. JAMA. 2000;284:699–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2008;10(2):393–398. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knishkowy B, Amitai Y. Water-pipe (narghile) smoking: an emerging health risk behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):e113–119. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etter JF. Electronic cigarettes: a survey of users. BMC public health. 2010;10:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L. Waterpipe (hookah) tobacco smoking among youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2011;41(2):34–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein JD. Hookahs and waterpipes: cultural tradition or addictive trap? The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2008;42(5):434–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith JR, Edland SD, Novotny TE, et al. Increasing Hookah Use in California. American journal of public health. 2011 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, et al. Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Substance use & misuse. 2015;50(1):79–89. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.958857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston L. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2009, Volume I: Secondary school students. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAMSHA . Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2013. NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Sumary of National Findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2014. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) [November 10, 2014];Legalization of Recreational/Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol (CBD) 2014 http://www.astho.org/Public-Policy/State-Health-Policy/Marijuana-Overview/.

- 27.Gallup I. [September 25, 2014];Gallup Poll: For First Time, Americans Favor Legalizing Marijuana. 2013 http://www.gallup.com/poll/165539/first-time-americans-favor-legalizing-marijuana.aspx.

- 28.Hickenlooper GJ. Experimenting with pot: the state of Colorado's legalization of marijuana. Milbank Q. 2014;92(2):243–249. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinsker EA, Berg CJ, Nehl E, Prokhorov AV, Buchanan T, Ahluwalia JS. Intentions to quit smoking among daily smokers and native and converted nondaily college student smokers Health education research. 2013;28(2):313–325. doi: 10.1093/her/cys116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutfin EL, McCoy TP, Berg CJ, et al. Tobacco use among college students: A comparison of daily and nondaily smokers. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2012;36(2):218–229. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.2.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, Donovan DM, Windle M. Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: Trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003-2012. Addictive behaviors. 2015;49:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enofe N, Berg CJ, Nehl E. Alternative tobacco product use among college students: Who is at highest risk? American Journal of Health Behavior. 2014;38(2):180–189. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.2.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park MJ, Scott JT, Adams SH, Brindis CD, Irwin CE., Jr. Adolescent and young adult health in the United States in the past decade: little improvement and young adults remain worse off than adolescents. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2014;55(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American College Health Association . Results of the National College Health Association Survey. American College Health Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration . Traffic Safety Facts 2001. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual review of public health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pope HG, Jr., Yurgelun-Todd D. The residual cognitive effects of heavy marijuana use in college students. JAMA. 1996;275(7):521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grech A, Van Os J, Jones PB, Lewis SW, Murray RM. Cannabis use and outcome of recent onset psychosis. European Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall W. The adverse health effects of cannabis use: what are they, and what are their implications for policy? . International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20(6):458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brook JS, Zhang C, Brook DW. Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: personal predictors. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2011;165(1):55–60. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brook JS, Kessler RC, Cohen P. The onset of marijuana use from preadolescence and early adolescence to young adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11(4):901–914. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynskey M, Hall W. The effects of adolescent cannabis use on educational attainment: a review. Addiction. 2000;95(11):1621–1630. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arria AM, Garnier-Dykstra LM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Winick AR, O'Grady KE. Drug Use Patterns and Continuous Enrollment in College:Results From a Longitudinal Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(1):71–83. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mittleman MA, Lewis RA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Muller JE. Triggering myocardial infarction by marijuana. Circulation. 2001;103(23):2805–2809. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polen MR, Sidney S, Tekawa IS, Sadler M, Friedman GD. Health care use by frequent marijuana smokers who do not smoke tobacco. The Western journal of medicine. 1993;158(6):596–601. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tashkin DP. Pulmonary complications of smoked substance abuse. The Western journal of medicine. 1990;152(5):525–530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang ZF, Morgenstern H, Spitz MR, et al. Marijuana use and increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(12):1071–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aryana A, Williams MA. Marijuana as a trigger of cardiovascular events: speculation or scientific certainty? Int J Cardiol. 2007;118(2):141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashibe M, Straif K, Tashkin DP, Morgenstern H, Greenland S, Zhang ZF. Epidemiologic review of marijuana use and cancer risk. Alcohol. 2005;35(3):265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37(7):747–775. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berg CJ, Wen H, Cumming CR, Ahluwalia JS, Druss BG. Depression and substance abuse and dependency in relation to current smoking status and frequency of smoking among nondaily and daily smokers. American Journal on Addictions. 2013;22:581–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Patterson F. Identifying and characterizing adolescent smoking trajectories. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2004;13(12):2023–2034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Montano DE, Kasprzyk D. The theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2002. pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health education and health behavior: Theory, research, and practice. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, Halpern CT. Which comes first in adolescence--sex and drugs or depression? American journal of preventive medicine. 2005;29(3):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Windle M, Wiesner M. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: predictors and outcomes. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(4):1007–1027. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu LT, Anthony JC. Tobacco smoking and depressed mood in late childhood and early adolescence. American journal of public health. 1999;89(12):1837–1840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.12.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2nd Edition. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berg CJ, Haardörfer R, Lewis M, et al. Project DECOY: Documenting Experiences with Cigarettes and Other Tobacco in Youth. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.40.3.3. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arria AM, Caldeira KM, O'Grady KE, et al. Drug exposure opportunities and use patterns among college students: results of a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Substance abuse : official publication of the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse. 2008;29(4):19–38. doi: 10.1080/08897070802418451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]