Abstract

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is an endogenous lipid mediator, produced from the metabolism of arachidonic acids, upon the sequential actions of phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenases, and prostaglandin E synthases. The various biological functions governed by PGE2 are mediated through its four distinct prostaglandin E receptors (EPs), designated as EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4, among which the EP4 receptor is the one most widely distributed in the heart. The availability of global or cardiac-specific EP4 knockout mice and the development of selective EP4 agonists/antagonists have provided substantial evidence to support the role of EP4 receptor in the heart. However, like any good drama, activation of PGE2-EP4 signaling exerts both protective and detrimental effects in the ischemic heart disease. Thus, the primary object of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the current progress of the PGE2-EP4 signaling in ischemic heart diseases, including cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. A better understanding of PGE2-EP4 signaling should promote the development of more effective therapeutic approaches to treat the ischemic heart diseases without triggering unwanted side effects.

1. Introduction

Ischemia of the heart resulting from the shortage of oxygen supply can lead to the occurrence of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (MI/R), presenting as a leading cause of mortality and morbidity especially in those with preexisting myocardial diseases such as cardiac hypertrophy both in developed and in developing countries [1]. In the general population, the incidence of ischemic heart diseases increases when a person becomes overweight or obese [2, 3], which could be attributed to the alterations in the control of coronary blood flow [4] or the dysregulation of adipocyte-derived hormones (such as adiponectin, leptin) in the obesity [5, 6]. The population of obesity has skyrocketed worldwide over the last three decades [7]. In addition, overweight and obesity were estimated to have caused 3.4 million deaths in 2010, most of which were from cardiovascular causes [8]. Therefore, examining ways to protect the ischemic heart and its associated diseases (like obesity, metabolic syndrome) will be of great clinical value in this industrialized world.

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is an endogenous lipid mediator, which belongs to the family of eicosanoids [9]. Upon the action of phospholipase A2, arachidonic acid, the precursor of prostaglandins, is generated from phospholipids in the cell membrane [10]. Arachidonic acid is then metabolized into prostaglandin H2 by cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes. Prostaglandin H2 is the first intermediate in the biosynthesis of prostaglandins, which requires the action of specific prostaglandin synthases. The specific synthases involved in the formation of PGE2 are microsomal prostaglandin E synthases- (mPGES-) 1 and mPGES-2 and cytosolic PGE2 synthases (cPGES) [9, 11]. PGE2 exerts its diverse effects by activating four subtypes of prostaglandin E receptors (EPs), designated as EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4 [12]. Of those, the EP4 receptor is the most widely distributed subtype which exists in almost all tissues, such as the heart, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and lung [13–15], and is involved in various pathophysiological processes [16–18]. In particular, mice lacking EP4 exhibited slower weight gain and reduced adiposity upon high fat diet challenge when compared with wild type mice [16]. However, the lean phenotype of EP4 knockout mice is not a beneficial factor. In fact, EP4 knockout mice had a shorter life span than did the wild type mice [16]. In addition, deficiency of EP4 in mice manifests disrupted lipid metabolism due to impaired triglyceride clearance, suggesting a new dimension role of EP4 signaling in controlling lipid homeostasis [16]. Activation of PGE2-EP4 signaling also can exert multiple biochemical effects on the heart, suggesting the potential wide-ranging use of EP4 in both cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. However, due to the limited reports of EP4 in ischemic heart under complicated disease states, in this review, we thus summarize the current progress regarding the role of the PGE2-EP4 signaling in ischemic heart diseases, including cardiac hypertrophy and MI/R, which has been obtained from studies using genetic knockout mouse and pharmacological interventions.

2. Prostaglandin E Receptor Subtype 4: Structure and Signaling

As one of the seven-transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptors, EP4 (originally misidentified as EP2 subtype [19]) shares the structure properties of G-protein-coupled receptors. It has an extracellular N-terminus, a seven-transmembrane domain connected by three extracellular loops and three intracellular loops, and an intracellular C-terminus [20]. The N-glycosylation sites in the second extracellular loop of EP4 are important for the ligand binding [21]. EP4 has the longest intracellular C-terminus and third intracellular loop out of the four EP receptors. The human EP4 receptor is comprised of 488 amino acid residues, while the murine EP4 receptor has two isoform variants that consist of 488 and 513 amino acid residues, respectively [22, 23]. The sequence homology of EP4 between these two species reaches up to 88% [21].

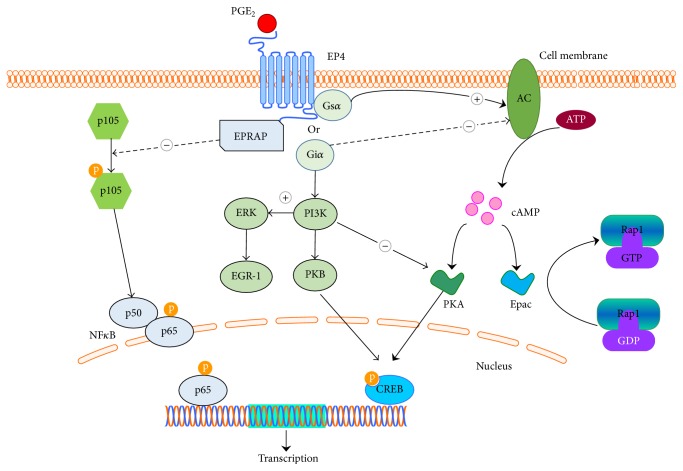

The downstream effectors of G-protein-coupled receptors are G-proteins, which consist of α, β, and γ subunits. Upon ligand binding, the conformational change in G-protein-coupled receptors triggers the dissociation of Gα from the Gβγ subunits [22]. EP4 is coupled to stimulated Gα (Gsα), which leads to the production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in response to PGE2 [23]. The increased intracellular cAMP level subsequently activates its major target protein kinase A (PKA). PKA then phosphorylates downstream protein, cAMP response element binding protein (CREBP), which is a nuclear transcriptional factor [24]. The activated CREBP then binds to specific sites and regulates the expression of certain genes, such as B-cell lymphoma 2 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), which are involved in development of ischemic heart disease [25]. In addition to PKA, another downstream molecule of Gsα/cAMP is exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac). Epac consists of Epac1 and Epac2. Both Epac isoforms can convert their downstream protein Ras-related protein 1 from inactivated guanosine diphosphate form to activated guanosine triphosphate form, which leads to the initiation of downstream signaling cascades [26]. EP4 is also coupled to the inhibitory Gα (Giα) [27]. In response to PGE2, Giα inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity leading to the reduced production of cAMP [28]. Furthermore, through activation of Giα, EP4 mediates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- (PI3K-) dependent pathway [29]. Activation of PI3K inhibits PKA activity but activates protein kinase B, which also can phosphorylate CREBP [30]. On the other hand, EP4 induces the expression of early growth response factor 1 through the PI3K/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway, which leads to the expression of PGE2 synthase, suggesting a positive feedback loop between EP4 and PGE2 production [23, 31]. Furthermore, yeast two-hybrid screening of human bone marrow complementary DNA with EP4 protein reveals that a protein named prostaglandin E receptor 4-associated protein (EPRAP) binds to the intracellular C-terminus of EP4 [32]. The interaction of EPRAP and EP4 inhibits stimulus-induced NFκB p105 phosphorylation and thus suppresses activation of NFκB [33] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Differential signaling pathway of EP4. In response to PGE2, activation of EP4 stimulates stimulatory Gα protein (Gsα)/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA)/cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) pathway or Gsα/cAMP/exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) pathway. EP4 is also coupled to inhibitory Gα protein (Giα), which inhibits the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway. Furthermore, EP4 activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) through activation of Giα. Activation of PI3K not only stimulates the protein kinase B (PKB)/CREB pathway but also induces the expression of early growth response factor 1 (EGR-1) through extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling. Prostaglandin E receptor 4-associated protein (EPRAP) can inhibit phosphorylation of p105 and further suppress the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB). AC = adenylyl cyclase; ATP = adenosine triphosphate; GDP = guanosine diphosphate; GTP = guanosine triphosphate.

Besides EP4 receptor, there are another three GPCRs, EP1, EP2, and EP3, which depend on G-protein to transduce downstream signals and mediate PGE2 actions [12]. EP1 receptor couples to Gqα protein and thus induces phospholipase C/inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling and leads to intracellular calcium mobilization [34]. The same as EP4 receptor, EP2 couples to Gsα protein and activates adenylate cyclase to produce cAMP, while EP3 is associated with Giα and inhibits cAMP production [35]. These EP subtypes have their unique expression patterns and associate to distinct downstream G-proteins and thereby lead to PGE2 being the most versatile prostanoid.

3. Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury

Myocardial ischemia caused by partial or complete occlusion of coronary arteries and the subsequent recovery of blood flow induced additional cardiac damage (ischemia/reperfusion injury) are leading causes for death around the world [36]. The underlying pathophysiology of myocardial I/R injury likely involves many factors, such as reactive oxygen species formation [37], altered cardiac energy metabolism [38], activation of cell apoptosis [39], and inflammatory responses [40].

During cardiac ischemia, the PGE2 level is significantly increased [41], and this increase may be a consequence of hypoxia inducible factor- (HIF-) 1α/COX-2/PGE2 pathway activation. Under ischemia conditions, the HIF-1α level starts to accumulate in the nucleus, be heterodimerized with β subunit, and initiate the transcription of genes which are involved in cell survival, angiogenesis, apoptosis, vascular remodeling, and glucose metabolism [42]. COX-2 has been proved to be a downstream protein of HIF-1α in various cell types, such as carcinoma cell lines HT29 [43] and human bronchial epithelial BEAS-2B cells [44]. COX-2 has been reported to be induced in the heart during I/R [45] and its expression was positively associated with the expression of HIF-1α at the site of recent acute myocardial infarction [46], despite the fact that direct evidence regarding whether or not COX-2 was transcriptionally controlled by HIF-1α in cardiomyocytes is lacking. Thus, as the major metabolite of COX-2, cardiac PGE2 may be produced through HIF-1α/COX-2 axis during cardiac ischemia.

The increased PGE2 level may play a beneficial role during cardiac I/R through EP4 receptor [15, 47]. Indeed, endogenous PGE2 protects the heart from I/R injury in vitro and in vivo [15]. In isolated perfused working hearts, there was a greater degree of functional damage to the myocardium (e.g., decreased developed tension, increased diastolic tension and creatine kinase (marker of myocardial injury) release) in EP4 knockout hearts after global ischemia when compared with wild type hearts [15]. In accordance with this result, mice lacking EP4 developed a greater degree of myocardial infarction size following I/R injury when compared with wild type mice in vivo [15]. Likewise, pharmacological intervention with an EP4 agonist significantly reduced infarct size and improved cardiac function, including left ventricular contraction and dilatation when compared with vehicle treated animals [47]. In line with this, the ischemic preconditioning-induced cardioprotection is completely lost in HIF-1α +/− mice [48]. Deficiency of hypoxia inducible transcription factor-prolyl hydroxylase domain-1 (PHD-1) in the mice significantly attenuated MI/R injury through reduced apoptosis by induction of HIF-1α [49], and COX-2 serves a protective role against myocardial I/R injury [50, 51]. These data provide additional evidence that PGE2-EP4 signaling sourced from HIF-1α/COX-2 axis is cardioprotective in the ischemic heart.

The subsequent downstream signaling of EP4 during the myocardial I/R injury has not been well documented yet. However, there are multiple potential downstream pathways. (1) cAMP-PKA pathway: Through the activation of EP4 receptor on the cell membrane, adenylyl cyclase catalyzes the conversion of adenosine triphosphate to cAMP. There are at least 9 isoforms of adenylyl cyclase; among them, adenylyl cyclase V and adenylyl cyclase VI are mainly expressed in the mammalian myocardium [52]. In the mice with cardiac adenylyl cyclase VI overexpression, adverse left ventricular remodeling was attenuated with preserved left ventricular contractile function and reduced mortality after myocardial ischemia [53]. In addition, through activating the downstream protein cAMP, PKA presents a cardioprotective role after ischemia possibly through its negative-inotropic effect during sustained ischemia [54]. In this study, the negative-inotropic effects of postischemic effluent can be significantly suppressed by preincubation with EP2 antagonist (AH6809) or EP4 antagonist (AH23848), indicating a protective role of both EP2 and EP4 receptor during I/R injury. However, unlike EP4 receptor, there is still no direct evidence showing that EP2 receptor can mediate the cardioprotective role of PGE2 in the postischemic heart during reperfusion in vivo and this warrants further investigation. These data suggested that cAMP-PKA may be responsible for the PGE2-EP4-mediated cardioprotection during myocardial ischemia. (2) Stat3 signaling: In addition to its role in the cardiac hypertrophy, Stat3 signaling activation also plays a causal role in ischemic postconditioning mediated cardioprotection [5]. Multiple lines of evidence suggested that activation of Stat3 signaling exerts cardioprotective effects during I/R injury through scavenging of reactive oxygen species [55] or improving mitochondrial function [56]. In cardiomyocytes, PGE2 activated Stat3 signaling through EP4 receptor in a concentration- and time-dependent manner [57]. Moreover, MI/R-induced tissue injury involves activation of cell apoptosis [39]. PGE2 is reported to prevent myocardial apoptosis through activation of Stat3 and ERK1/2 in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis model in neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes [58], suggesting that activation of Stat3 signaling may contribute to PGE2-EP4-mediated cardioprotective role during I/R injury. In addition, despite the fact that there is no direct evidence showing that activation of EP4 receptor exerts antiapoptotic role in cardiomyocytes during I/R injury, it has been proved that PGE2 protects normal and transformed intestinal epithelial cells from diverse stimuli-induced apoptosis via EP4 receptor [59]. Consistently, another study showed that EP4 agonist (L-902688) significantly inhibits the cell death during in vivo focal cerebral ischemia [60]. Taken together, these data suggested that PGE2-EP4 signaling may mediate cardioprotection through attenuating cell apoptosis during myocardial ischemia.

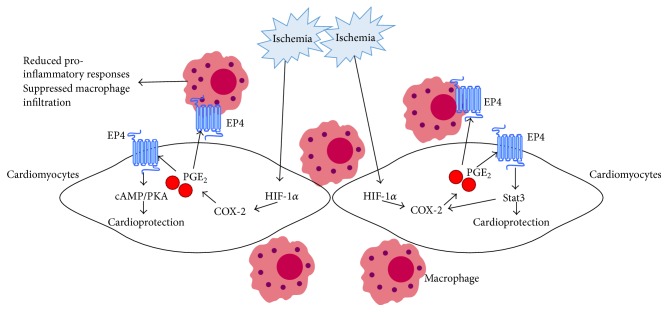

During ischemia, inflammatory cells like macrophages may migrate into the ischemic myocardium and produce proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including TNFα, interleukin 6 (IL6), IL-1β, and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), which further exacerbate myocardial I/R injury [40]. Thus, it is possible that the anti-inflammatory effect of EP4 on macrophages may contribute to the beneficial role of EP4 in cardiac ischemia. Indeed, EP4 agonist significantly attenuated the production of TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β, and MCP-1 as well as macrophage infiltration in the heart after ischemia [47]. Of note, the EP4-Stat3 signaling may establish a positive feedback loop through controlling the expression of COX-2 in cardiomyocytes, while the newly secreted PGE2 may not only trigger greater Stat3 activation but also exert anti-inflammatory effect on infiltrated inflammatory cells in a paracrine way (Figure 2). Thus, EP4 receptor may confer protection against I/R injury at multiple levels. EP4 agonist may provide a novel approach to limit the damage from myocardial I/R injury.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the proposed role of EP4-mediated signaling under myocardial ischemia. During cardiac ischemia, increased PGE2 level may be a consequence of increased hypoxia inducible factor- (HIF-) 1α/cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) activation. PGE2 may play a beneficial role in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury through EP4/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) or EP4/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) signaling pathway. In addition, synthesized PGE2 in cardiomyocytes also diffuses into adjacent infiltrated macrophages or other inflammatory cells, protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury through binding with EP4 receptor, and exerts anti-inflammatory effects.

4. Cardiac Hypertrophy

Pathological cardiac hypertrophy is a slow adaptive response to various types of extracellular stressors, including increased hemodynamic load [61], neurohormones [62], growth factors [63], and cytokines [64]. At the early stage, cardiac hypertrophy is compensatory to maintain the circulatory system homeostasis. However, the severe and sustained workload on the heart may trigger the cardiac remodeling process and increase the risk of cardiac dysfunction and, ultimately, the development of heart failure [65] and the underlying mechanism is incompletely understood. A better understanding of the signal transmission from cell surface to the nuclear transcription activities in response to various hypertrophic stimuli may yield novel therapeutic approaches to treat cardiac hypertrophy.

In ventricular myocytes, PGE2 significantly increased total protein synthesis (measured by [3H]-phenylalanine uptake), cell surface area, and hypertrophic maker genes, including atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), in a dose dependent manner [66–68]. These hypertrophic effects of PGE2 were conserved in vivo. Using a mouse model of myocardial infarction, injection with NS-398 or rofecoxib (COX-2 selective inhibitors) in mice significantly downregulated cardiac PGE2 production and reduced cardiac hypertrophy as determined by myocyte cross-sectional area when compared with vehicle treated mice [69]. Similarly, mice with global knockout of mPGES-1, which is in charge of the inducible PGE2 synthase, also exhibited decreased cardiac PGE2 levels, myocyte cross-sectional area, and cardiomyocyte surface area after myocardial infarction when compared to wild type mice, suggesting that PGE2 positively regulates cardiac hypertrophy in vitro and in vivo [70].

Activation of EP4 receptor signaling contributes to the PGE2-mediated cardiac hypertrophy, since EP4 specific antagonist (L-161982 or ONO-AE3-208) significantly blocked the hypertrophic actions of PGE2, including the protein synthesis, mRNA expression of ANP and BNP in neonatal cardiac cells [66, 68]. In accordance with these observations, myocyte cross-sectional area was significantly smaller in cardiac-specific EP4 knockout mice after myocardial infarction when compared with wild type mice, suggesting that the lack of EP4 receptor signaling in cardiomyocytes alleviated cardiac hypertrophy after myocardial infarction [71]. By contrast, global EP4 knockout mice did not affect the myocyte cross-sectional area and heart/body weight ratio under basal conditions [15] or pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy through transverse aortic constriction (TAC) treatment [72] as compared with wild type mice. There are several possible explanations regarding the discrepancy among these studies. (1) The development of cardiac hypertrophy is a very slow process, and thus if there are no continuous hypertrophic stimuli, it may take a long time to develop cardiac hypertrophy. Therefore, it may be difficult to detect significant difference in the development of cardiac hypertrophy between EP4 wild type and knockout mice under basal conditions. (2) The wide distribution of EP4 receptor in different kinds of cells indicates its diverse biological functions in vivo, such as anti-inflammatory response [73] and energy metabolism [16]. The affected anti-inflammatory pathway or lipid metabolism in global EP4 knockout mice may influence the development of cardiac hypertrophy indirectly. Indeed, inflammatory process and energy metabolism are closely associated with the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy [74, 75]. Thus, under basal condition or TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy, global knockout of EP4 in mice may affect the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy through other compensatory pathways. (3) Different cardiac hypertrophic stimuli activate diverse signaling cascades and may have distinct cardiomyocyte gene expression pattern [65]. It is possible that PGE2-EP4 signaling is only involved in myocardial infarction—but not pressure overload-mediated cardiac hypertrophy. (4) In the study of Hara et al. [72], the heart/body weight ratios were only compared between EP4 wild type and knockout mice after 4 weeks of TAC treatment, a time point at which generally the pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy has reached the maximal level. Thus, comparison should be performed at both the early and late phase of the disease to get a solid conclusion. Through these explanations, it is tempting to speculate that EP4 in cardiomyocytes may be the endogenous ligand to mediate the hypertrophic effects of PGE2 both in vitro and in vivo, but its definite role in this pathology needs to be confirmed in future studies.

The additional challenge is to identify the subsequent downstream molecules in EP4-mediated cardiac hypertrophy. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) has emerged as an important regulator of cardiac hypertrophy [76]. There is study that reported that PGE2 activates the mTOR complex 1 pathway through an EP4/cAMP/PKA mediated mechanism in the human pancreatic carcinoma cell line PANC-1 [77]. Besides PKA, cAMP also exerts its biological functions through Epac. Despite the fact that cAMP-producing β-adrenergic stimulation induces cardiac hypertrophy [78], cAMP/PKA or cAMP/Epac signaling is not likely to mediate the hypertrophic effects of PGE2 in cardiomyocytes, since all the treatment like cAMP activator (forskolin), cAMP inhibitor (SQ-22536), PKA inhibitor (H89), and Epac activator (8-CPT-2Me-cAMP) at different concentrations had no effect on PGE2-induced protein synthesis in ventricular myocytes [57, 68, 79]. Thus, mTOR may not be able to mediate the hypertrophic effects of PGE2/EP4 in cardiomyocytes.

It is well known that mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signaling cascade is a prominent player involved in the hypertrophic reaction with its four best characterized subfamilies, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2 or P42/P44 MAPK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 MAPK, and ERK5 [80]. The ERK1/2 inhibitor, U0126, significantly reduced the hypertrophic effect of PGE2 in ventricular myocytes, whereas the p38 MAPK blocker (SB203580) and JNK inhibitor (SP600125) have no such effect [68]. In addition, activation of ERK1/2 by PGE2 was strongly suppressed by EP4 antagonist ONO-208 compound, indicating that ERK1/2 signaling cascade was involved in PGE2-EP4-mediated cardiac hypertrophy [57, 68]. However, the involvement of ERK5 on PGE2-induced protein synthesis remains undefined.

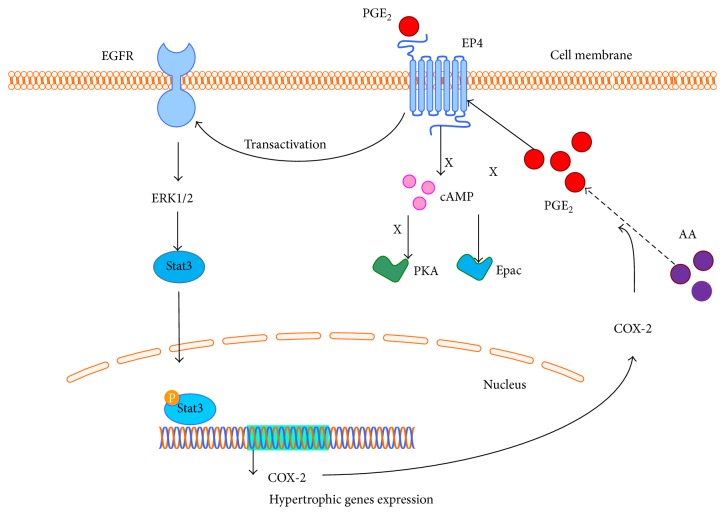

Activation of G-protein-coupled receptors has been shown to transactivate epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR), which can result in the activation of ERK1/2 signaling [81, 82]. Indeed, EP4 antagonist L-161982 significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of EGFR by PGE2 in ventricular myocytes. Furthermore, EGFR inhibitor AG-1478 totally blocked activation of ERK1/2 by PGE2 and PGE2-EP4-mediated protein synthesis, suggesting that activation of EGFR bridges PGE2/EP4 and ERK1/2 signaling and also is responsible for PGE2-induced protein synthesis in cardiomyocytes [79].

As reported in several studies, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) pathway is another signaling cascade that plays a major role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Multiple in vitro and in vivo studies suggested that activation of Stat3 promotes cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in response to various stimuli through transcriptional control of hypertrophic genes expression [83, 84]. PGE2 induced Stat3 activation in cardiomyocytes in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, while ERK1/2 inhibitor (U0126) and EP4 antagonists (GW627368X or AH23848B) significantly suppressed PGE2-induced Stat3 activation [57]. In Stat3-silenced cardiomyocytes, the PGE2-mediated protein synthesis was dramatically inhibited [57], suggesting that activation of Stat3 works downstream of PGE2-EP4-ERK1/2-mediated cardiac hypertrophy in vitro. Accordingly, myocardial infarction induced cardiac hypertrophy was accompanied with significantly increased Stat-3 phosphorylation in wild type controls, but the increase of Stat-3 phosphorylation was absent in the heart from cardiomyocyte-specific EP4 knockout mouse, suggesting that EP4-Stat3 signaling is conserved in vivo and responsible for cardiac hypertrophy [71]. Furthermore, once Stat3 signaling is activated in the nucleus, the gene expression of COX-2 will be stimulated, which will metabolize the first step in the formation of PGE2 from arachidonic acid and trigger the greater activation of Stat3 signaling in a positive feedback loop [85]. Thus, these findings together demonstrated the pathophysiological importance of PGE2 signaling through EP4-EGFR-ERK1/2-Stat3 cascade that was involved in the development of cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Simplified scheme of the EP4 signaling in PGE2-mediated hypertrophic actions. In response to PGE2, activation of EP4 transactivates epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR), which can result in the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2). ERK1/2 in turn activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) pathway. Once Stat3 signaling is activated in the nucleus, the hypertrophic genes will be expressed to mediate the protein synthesis. In addition, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression is also stimulated by Stat3 signaling, which will further metabolize the formation of PGE2 from arachidonic acid (AA) and trigger the greater activation of Stat3 signaling in a positive feedback loop. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) or cAMP/exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) pathways are not involved in the PGE2-EP4-mediated hypertrophic actions in ventricular myocytes.

5. Conclusion

Cardiac hypertrophy is not only a risk factor for myocardial ischemia, but also part of the response of MI/R-induced tissue injury, which further promotes the extent of ischemia. It is very interesting that activation of PGE2-EP4 signaling may impact on ischemic heart events through totally opposite pathways. EP4 may mediate the cardiac hypertrophy through EGFR/ERK1/2/Stat3 signaling, whereas PGE2-EP4 signaling may protect the heart from MI/R injury through cAMP/PKA or Stat3 pathway. Despite the fact that there is still no direct evidence showing the role of Stat3 signaling in EP4-mediated cardioprotection, the in vivo model, cardiac-specific EP4 knockout mice with myocardial infarction, exhibited decreased hypertrophic changes but worsened cardiac function, suggesting that activation of EP4 signaling may contribute to the compensatory survival of cardiomyocytes for maintaining the normal cardiac function. In the future, with regard to the potential detrimental effects of EP4, special caution is needed when evaluating how EP4 can be preferably activated in the heart without triggering unwanted side effects. In addition, the role of PGE2-EP4 signaling pathway in the heart should be further explored in detail, with the aim of developing therapeutic approaches to treat the patients with ischemic heart disease and its associated diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors' research was supported by the General Research Fund (17123915M, 17124614M, and 17121315M) from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong and Educational Commission of JiLin Province of China (2016-471).

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Lei Pang and Yin Cai contributed equally.

References

- 1.Ferdinandy P., Hausenloy D. J., Heusch G., Baxter G. F., Schulz R. Interaction of risk factors, comorbidities, and comedications with ischemia/reperfusion injury and cardioprotection by preconditioning, postconditioning, and remote conditioning. Pharmacological Reviews. 2014;66(4):1142–1174. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calle E. E., Thun M. J., Petrelli J. M., Rodriguez C., Heath C. W., Jr. Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341(15):1097–1105. doi: 10.1056/nejm199910073411501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S., Hawken S., Ôunpuu S., et al. Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27 000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. The Lancet. 2005;366(9497):1640–1649. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berwick Z. C., Dick G. M., Tune J. D. Heart of the matter: coronary dysfunction in metabolic syndrome. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2012;52(4):848–856. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H., Yao W., Irwin M. G., et al. Adiponectin ameliorates hyperglycemia-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction by concomitantly activating Nrf2 and Brg1. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2015;84:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin S. S., Qasim A., Reilly M. P. Leptin resistance: a possible interface of inflammation and metabolism in obesity-related cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52(15):1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M., et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–781. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poorten D. V. D. Obesity, gastrointestinal cancer and the role of visceral fat. Translational Gastrointestinal Cancer. 2014;3(3):127–129. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murakami M. Lipid mediators in life science. Experimental Animals. 2011;60(1):7–20. doi: 10.1538/expanim.60.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gijón M. A., Leslie C. C. Regulation of arachidonic acid release and cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1999;65(3):330–336. doi: 10.1002/jlb.65.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harizi H., Corcuff J.-B., Gualde N. Arachidonic-acid-derived eicosanoids: roles in biology and immunopathology. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2008;14(10):461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugimoto Y., Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(16):11613–11617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.r600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regard J. B., Sato I. T., Coughlin S. R. Anatomical profiling of G protein-coupled receptor expression. Cell. 2008;135(3):561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang E. H. C., Cai Y., Wong C. K., et al. Activation of prostaglandin E2-EP4 signaling reduces chemokine production in adipose tissue. Journal of Lipid Research. 2015;56(2):358–368. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m054817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao C.-Y., Yuhki K.-I., Hara A., et al. Prostaglandin E2 protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury via its receptor subtype EP4. Circulation. 2004;109(20):2462–2468. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000128046.54681.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Y., Ying F., Song E., et al. Mice lacking prostaglandin E receptor subtype 4 manifest disrupted lipid metabolism attributable to impaired triglyceride clearance. The FASEB Journal. 2015;29(12):4924–4936. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-274597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang E. H. C., Shimizu K., Christen T., et al. Lack of EP4 receptors on bone marrow-derived cells enhances inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions. Cardiovascular Research. 2011;89(1):234–243. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang E. H. C., Shvartz E., Shimizu K., et al. Deletion of EP4 on bone marrow-derived cells enhances inflammation and angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2011;31(2):261–269. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.110.216580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bastien L., Sawyer N., Grygorczyk R., Metters K. M., Adam M. Cloning, functional expression, and characterization of the human prostaglandin E2 receptor EP2 subtype. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(16):11873–11877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobilka B. K. G protein coupled receptor structure and activation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Biomembranes. 2007;1768(4):794–807. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narumiya S., Sugimoto Y., Ushikubi F. Prostanoid receptors: structures, properties, and functions. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79(4):1193–1226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuteja N. Signaling through G protein coupled receptors. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2009;4(10):942–947. doi: 10.4161/psb.4.10.9530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokoyama U., Iwatsubo K., Umemura M., Fujita T., Ishikawa Y. The prostanoid EP4 receptor and its signaling pathway. Pharmacological Reviews. 2013;65(3):1010–1052. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delghandi M. P., Johannessen M., Moens U. The cAMP signalling pathway activates CREB through PKA, p38 and MSK1 in NIH 3T3 cells. Cellular Signalling. 2005;17(11):1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ichiki T. Role of cAMP response element binding protein in cardiovascular remodeling: good, bad, or both? Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2006;26(3):449–455. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000196747.79349.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Rooij J., Zwartkruis F. J. T., Verheijen M. H. G., et al. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature. 1998;396(6710):474–477. doi: 10.1038/24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujino H., Regan J. W. EP4 prostanoid receptor coupling to a pertussis toxin-sensitive inhibitory G protein. Molecular Pharmacology. 2006;69(1):5–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anand-Srivastava M. B. Modulation of Gi proteins in hypertension: role of angiotensin II and oxidative stress. Current Cardiology Reviews. 2010;6(4):298–308. doi: 10.2174/157340310793566046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujino H., West K. A., Regan J. W. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 and stimulation of T-cell factor signaling following activation of EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptors by prostaglandin E2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(4):2614–2619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pugazhenthit S., Nesterova A., Sable C., et al. Akt/protein kinase B up-regulates Bcl-2 expression through cAMP-response element-binding protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(15):10761–10766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujino H., Xu W., Regan J. W. Prostaglandin E2 induced functional expression of early growth response factor-1 by EP4, but not EP2, prostanoid receptors via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinases. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(14):12151–12156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m212665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takayama K., Sukhova G. K., Chin M. T., Libby P. A novel prostaglandin E receptor 4-associated protein participates in antiinflammatory signaling. Circulation Research. 2006;98(4):499–504. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000204451.88147.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minami M., Shimizu K., Okamoto Y., et al. Prostaglandin E receptor type 4-associated protein interacts directly with NF-κB1 and attenuates macrophage activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(15):9692–9703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m709663200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katoh H., Watabe A., Sugimoto Y., Ichikawa A., Negishi M. Characterization of the signal transduction of prostaglandin E receptor EP1 subtype in cDNA-transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1244(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)00182-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naribayashi-Inomoto Y., Ding M., Nakata H., et al. Copresence of prostaglandin EP2 and EP3 receptors on gastric enterochromaffin-like cell carcinoid in African rodents. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(2):341–347. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hausenloy D. J., Yellon D. M. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: a neglected therapeutic target. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123(1):92–100. doi: 10.1172/jci62874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mao X., Wang T., Liu Y., et al. N-acetylcysteine and allopurinol confer synergy in attenuating myocardial ischemia injury via restoring HIF-1α/HO-1 signaling in diabetic rats. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068949.e68949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heidrich F., Schotola H., Popov A. F., et al. AMPK—activated protein kinase and its role in energy metabolism of the heart. Current Cardiology Reviews. 2010;6(4):337–342. doi: 10.2174/157340310793566073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krijnen P. A. J., Nijmeijer R., Meijer C. J. L. M., Visser C. A., Hack C. E., Niessen H. W. M. Apoptosis in myocardial ischaemia and infarction. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2002;55(11):801–811. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.11.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frangogiannis N. G. Targeting the inflammatory response in healing myocardial infarcts. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;13(16):1877–1893. doi: 10.2174/092986706777585086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calabresi L., Rossoni G., Gomaraschi M., Sisto F., Berti F., Franceschini G. High-density lipoproteins protect isolated rat hearts from ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing cardiac tumor necrosis factor-α content and enhancing prostaglandin release. Circulation Research. 2003;92(3):330–337. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000054201.60308.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semenza G. L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and cardiovascular disease. Annual Review of Physiology. 2014;76:39–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaidi A., Qualtrough D., Williams A. C., Paraskeva C. Direct transcriptional up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 promotes colorectal tumor cell survival and enhances HIF-1 transcriptional activity during hypoxia. Cancer Research. 2006;66(13):6683–6691. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He J., Wang M., Jiang Y., et al. Chronic arsenic exposure and angiogenesis in human bronchial epithelial cells via the ROS/miR-199a-5p/HIF-1α/COX-2 pathway. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014;122(3):255–261. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schrör K., Zimmermann K. C., Tannhäuser R. Augmented myocardial ischaemia by nicotine—mechanisms and their possible significance. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;125(1):79–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abbate A., Santini D., Biondi-Zoccai G. G. L., et al. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression at the site of recent myocardial infarction: friend or foe? Heart. 2004;90(4):440–443. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.010280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hishikari K., Suzuki J.-I., Ogawa M., et al. Pharmacological activation of the prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 improves cardiac function after myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovascular Research. 2009;81(1):123–132. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cai Z., Zhong H., Bosch-Marce M., et al. Complete loss of ischaemic preconditioning-induced cardioprotection in mice with partial deficiency of HIF-1α . Cardiovascular Research. 2008;77(3):463–470. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adluri R. S., Thirunavukkarasu M., Dunna N. R., et al. Disruption of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-prolyl hydroxylase domain-1 (PHD-1−/−) attenuates ex vivo myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through hypoxia-inducible factor-1α transcription factor and its target genes in mice. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2011;15(7):1789–1797. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolli R., Shinmura K., Tang X.-L., et al. Discovery of a new function of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2: COX-2 is a cardioprotective protein that alleviates ischemia/reperfusion injury and mediates the late phase of preconditioning. Cardiovascular Research. 2002;55(3):506–519. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00414-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y., Kodani E., Wang J., et al. Cardioprotection during the final stage of the late phase of ischemic preconditioning is mediated by neuronal NO synthase in concert with cyclooxygenase-2. Circulation Research. 2004;95(1):84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000133679.38825.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leineweber K., Böhm M., Heusch G. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate in acute myocardial infarction with heart failure: slayer or savior? Circulation. 2006;114(5):365–367. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.106.642132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahashi T., Tang T., Lai N. C., et al. Increased cardiac adenylyl cyclase expression is associated with increased survival after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;114(5):388–396. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birkenmeier K., Janke I., Schunck W.-H., et al. Prostaglandin receptors mediate effects of substances released from ischaemic rat hearts on non-ischaemic cardiomyocytes. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;38(12):902–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oshima Y., Fujio Y., Nakanishi T., et al. STAT3 mediates cardioprotection against ischemia/reperfusion injury through metallothionein induction in the heart. Cardiovascular Research. 2005;65(2):428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heusch G., Musiolik J., Gedik N., Skyschally A. Mitochondrial STAT3 activation and cardioprotection by ischemic postconditioning in pigs with regional myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation Research. 2011;109(11):1302–1308. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.111.255604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frias M. A., Rebsamen M. C., Gerber-Wicht C., Lang U. Prostaglandin E2 activates Stat3 in neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes: a role in cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovascular Research. 2007;73(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frias M. A., Somers S., Gerber-Wicht C., Opie L. H., Lecour S., Lang U. The PGE2-Stat3 interaction in doxorubicin-induced myocardial apoptosis. Cardiovascular Research. 2008;80(1):69–77. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nishihara H., Kizaka-Kondoh S., Insel P. A., Eckmann L. Inhibition of apoptosis in normal and transformed intestinal epithelial cells by cAMP through induction of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP)-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(15):8921–8926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533221100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akram A., Gibson C. L., Grubb B. D. Neuroprotection mediated by the EP4 receptor avoids the detrimental side effects of COX-2 inhibitors following ischaemic injury. Neuropharmacology. 2013;65:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Devereux R. B., Savage D. D., Sachs I., Laragh J. H. Relation of hemodynamic load to left ventricular hypertrophy and performance in hypertension. The American Journal of Cardiology. 1983;51(1):171–176. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(83)80031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gray M. O., Long C. S., Kalinyak J. E., Li H.-T., Karliner J. S. Angiotensin II stimulates cardiac myocyte hypertrophy via paracrine release of TGF-β 1 and endothelin-1 from fibroblasts. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;40(2):352–363. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Serneri G. G. N., Modesti P. A., Boddi M., et al. Cardiac growth factors in human hypertrophy: relations with myocardial contractility and wall stress. Circulation Research. 1999;85(1):57–67. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fredj S., Bescond J., Louault C., Delwail A., Lecron J.-C., Potreau D. Role of interleukin-6 in cardiomyocyte/cardiac fibroblast interactions during myocyte hypertrophy and fibroblast proliferation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2005;204(2):428–436. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frey N., Katus H. A., Olson E. N., Hill J. A. Hypertrophy of the heart: a new therapeutic target? Circulation. 2004;109(13):1580–1589. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000120390.68287.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.He Q., Harding P., LaPointe M. C. PKA, Rap1, ERK1/2, and p90RSK mediate PGE2 and EP4 signaling in neonatal ventricular myocytes. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2010;298(1):H136–H143. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00251.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miyatake S., Manabe-Kawaguchi H., Watanabe K., Hori S., Aikawa N., Fukuda K. Prostaglandin E2 induces hypertrophic changes and suppresses α-skeletal actin gene expression in rat cardiomyocytes. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2007;50(5):548–554. doi: 10.1097/fjc.0b013e318145ae2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qian J.-Y., Leung A., Harding P., LaPointe M. C. PGE2 stimulates human brain natriuretic peptide expression via EP4 and p42/44 MAPK. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006;290(5):H1740–H1746. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00904.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.LaPointe M. C., Mendez M., Leung A., Tao Z., Yang X.-P. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction in the mouse. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2004;286(4):H1416–H1424. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00136.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Degousee N., Fazel S., Angoulvant D., et al. Microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 deletion leads to adverse left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(13):1701–1710. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.749739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qian J.-Y., Harding P., Liu Y., Shesely E., Yang X.-P., LaPointe M. C. Reduced cardiac remodeling and function in cardiac-specific EP4 receptor knockout mice with myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2008;51(2):560–566. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.102590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hara A., Yuhki K.-I., Fujino T., et al. Augmented cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload in mice lacking the prostaglandin I2 receptor. Circulation. 2005;112(1):84–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.527077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang E. H. C., Libby P., Vanhoutte P. M., Xu A. Anti-inflammation therapy by activation of prostaglandin EP4 receptor in cardiovascular and other inflammatory diseases. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2012;59(2):116–123. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182244a12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allard M. F. Energy substrate metabolism in cardiac hypertrophy. Current Hypertension Reports. 2004;6(6):430–435. doi: 10.1007/s11906-004-0036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smeets P. J. H., Teunissen B. E. J., Planavila A., et al. Inflammatory pathways are activated during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and attenuated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors PPARα and PPARδ . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(43):29109–29118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m802143200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Soesanto W., Lin H.-Y., Hu E., et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin is a critical regulator of cardiac hypertrophy in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2009;54(6):1321–1327. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang H. H., Young S. H., Sinnett-Smith J., et al. Prostaglandin E2 activates the mTORC1 pathway through an EP4/cAMP/PKA- and EP1/Ca2+-mediated mechanism in the human pancreatic carcinoma cell line PANC-1. American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology. 2015;309(10):C639–C649. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00417.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Métrich M., Berthouze M., Morel E., Crozatier B., Gomez A. M., Lezoualc'h F. Role of the cAMP-binding protein Epac in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 2010;459(4):535–546. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0747-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mendez M., LaPointe M. C. PGE2-induced hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes involves EP4 receptor-dependent activation of p42/44 MAPK and EGFR transactivation. American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2005;288(5):H2111–H2117. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00838.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rose B. A., Force T., Wang Y. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the heart: angels versus demons in a heart-breaking tale. Physiological Reviews. 2010;90(4):1507–1546. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00054.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prenzel N., Zwick E., Daub H., et al. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. 1999;402(6764):884–888. doi: 10.1038/47260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shah B. H., Farshori M. P., Jambusaria A., Catt K. J. Roles of Src and epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation in transient and sustained ERK1/2 responses to gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(21):19118–19126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kunisada K., Negoro S., Tone E., et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in the heart transduces not only a hypertrophic signal but a protective signal against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(1):315–319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kunisada K., Tone E., Fujio Y., Matsui H., Yamauchi-Takihara K., Kishimoto T. Activation of gp130 transduces hypertrophic signals via STAT3 in cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 1998;98(4):346–352. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xiong H., Du W., Sun T.-T., et al. A positive feedback loop between STAT3 and cyclooxygenase-2 gene may contribute to Helicobacter pylori-associated human gastric tumorigenesis. International Journal of Cancer. 2014;134(9):2030–2040. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]