Abstract

Aim:

Human papilloma viruses (HPVs) are small DNA viruses that have been identified in periodontal pocket as well as gingival sulcus. High risk HPVs are also associated with a subset of head and neck carcinomas. HPV detection in periodontium has previously involved DNA detection. This study attempts to: (a) Detect the presence or absence of high risk HPV in marginal periodontiun by identifying E6/E7 messenger RNA (mRNA) in cells from samples obtained by periodontal pocket scraping. (b) Detect the percentage of HPV E6/E7 mRNA in cells of pocket scrapings, which is responsible for producing oncoproteins E6 and E7.

Materials and Methods:

Pocket scrapings from the periodontal pockets of eight subjects with generalized chronic periodontitis were taken the detection of presence or absence of E6, E7 mRNA was performed using in situ hybridization and flow cytometry.

Results:

HPV E6/E7 mRNA was detected in four of the eight samples.

Conclusion:

Presence of high risk human papillomaviruses in periodontal pockets patients of diagnosed with chronic periodontitis, not suffering from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in the present day could link periodontitis to HPV related squamous cell carcinoma. Prevalence studies are needed detecting the presence of HPV in marginal periodontium as well as prospective studies of HPV positive periodontitis patients are required to explore this possible link.

Keywords: E6/E7 messenger RNA, head and neck carcinoma, human papilloma virus, periodontal pocket

INTRODUCTION

Papilloma viruses are epitheliotropic DNA viruses[1] associated with several benign conditions including condylomata acuminatum, focal epithelial dysplasia, respiratory papillomatosis,[2] and gingival warts.[3,4] It has been known since the 1990s that papillomaviruses cause cervical cancer.[5]

Of late, these viruses have also been implicated in the etiology of a growing subset head and neck cancers, specifically the oropharynx and the base of tongue, numerous cases of which have been reported all over the world[6,7,8] despite increasing awareness about the hazards of tobacco use. High-risk human papilloma virus (HPV) genotypes such as HPV-16, HPV-18, HPV-31, and HPV-33 have been found to be associated with these cancers.[9] The significance of the increased incidence of head and neck carcinomas caused by human papillomaviruses is reflected by the fact that human squamous cell carcinomas have now been divided into two subsets: Tobacco related squamous cell carcinomas and HPV related squamous cell carcinomas.[10,11,12]

Of rising concern, importance is the fact that high risk human papillomaviruses have been detected in the periodontium of patients diagnosed with chronic periodontitis as well as those with healthy gingiva.[13] It has even been thought that sites in close proximity to tongue and oropharynx may serve as reservoirs for high risk human papillomaviruses[14] which may include periodontal pockets or gingival sulci of mandibular posterior teeth.

HPV E6, E7 oncoproteins mediate the development of cancer. Their overexpression can be measured as E6, E7 messenger RNA (mRNA) transcripts.[15]

Previous studies have used HPV DNA testing methods to identify HPV in the periodontium which provide adequate sensitivity but lack specificity. This pilot study attempts to detect high risk HPVs in marginal periodontium by detection of E6/E7 mRNA within intact cells using in situ hybridization and flow cytometry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Eight patients were included from the outpatient Department of Periodontics, KVG Dental College, Sullia, Karnataka, India.

Patients diagnosed with generalized chronic periodontitis according to the 1999 classification of periodontal diseases (American Academy of Periodontics) with CAL >5 mm clinically seen as pocket, with age ranging from 30 to 70 years were included in the study and plaque corresponding to attachment loss and horizontal type of bone loss seen on orthopantomograph.

Patients with signs of aggressive periodontitis (arc shaped bone loss, familial history of aggressive periodontitis) were excluded. Patients who had a history of carcinoma of head and neck or a visible growth on base of tongue or pharynx area were excluded. Patients on antiviral drugs were also excluded.

Pocket scraping

The selected pocket of buccal aspect of mandibular molar or premolar teeth was isolated and anesthetized by infiltrating lignocaine solution in the vestibule of the concerned tooth. The samples were taken by a single examiner. Area specific gracey curettes (Hu Friedy) were then inserted till the base of the pocket and scraped upwards. The sample obtained was stored in carrier medium provided by Curehealth Diagnostics.

Pocket scraping was taken using area specific curettes after the area was anaesthetized. The sample obtained was stored in carrier medium and sent to: Curehealth Diagnostics (ISO 9001 2009).

Method of analysis

The sample was analyzed at Curehealth Diagnostics using standardized detection method for HPV.

The sample (periodontal pocket scraping) is first centrifuged at 3500 rpm (1000 G) for 5 min to obtain a pellet and a supernatant. The supernatant is discarded. The sample is then washed with phosphate buffered saline followed by a second centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 5 min.

A permeabilizing agent (Reagent 1)-800 UL is added to allow entry of the probe and vortexed. Incubation is carried out for 1 h at room temperature.

Prehybridization buffer (Reagent 2) is then added, and the solution is vortexed followed by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 5 min. This process removes debris from the sample. The solution is incubated for 30 min at 43°C.

Reagent 4 (probe diluent) and Reagent 5 (concentrated probe) are the constituents of the probe, added at 103 UL/sample (100 UL Reagent 4 and 3 UL Reagent 5).

One milliliter post hybridization buffer is then added to the solution (Reagent 6) to remove the unwanted binding between two strands of mRNA and between probe and mRNA. Centrifugation is carried out again to obtain pellet and supernatant, of which supernatant is discarded.

Treatment is carried out with Reagent 7, also a post hybridization buffer and solution is incubated at 43°C for 15 min.

The sample is then subjected to flow cytometry (Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer, manufactured by BD, USA) and analyzed.

Not only the presence or absence of HPV is detected, but also the over-expression of viral oncogenes E6 and E7, as a direct marker of high grade cellular transforming activity. It utilizes molecular in situ hybridization as an indicator of oncogenic activity caused due to up-regulation of E6/E7 genes. The transforming cells exhibit much higher levels of E6 and E7 proteins than the benign or non infected cells.

RESULTS

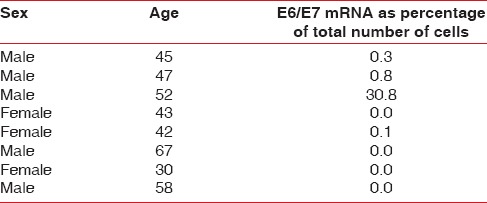

E6/E7 mRNA was absent in four of the eight samples, indicating the absence of HPV in the periodontium of these patients [Table 1].

Table 1.

Number of samples showing presence and absence of E6/E7 mRNA

E6/E7 mRNA was present in three of the eight samples but below the 2% cut off, this indicates the presence of high risk HPV in the marginal periodontium of these patients [Table 1].

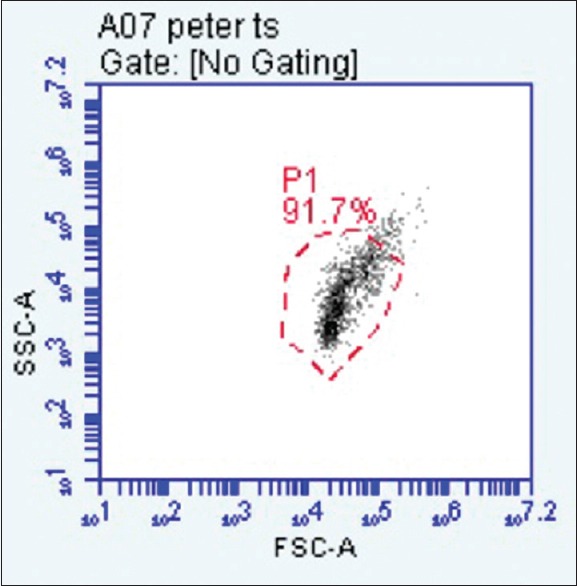

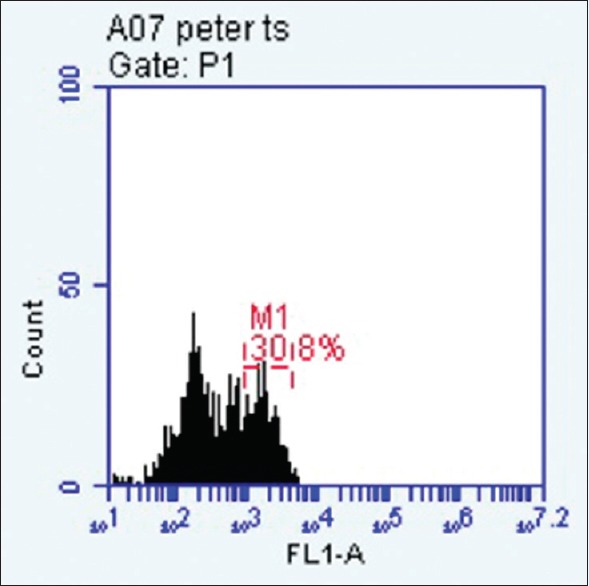

E6/E7 mRNA was found to be present in one of the eight samples above the 2% cut off indicating presence of virus as well as oncogenic potential[16] [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Dot plot is showing cells included in pocket scraping with side and forward scatter. Cells showing forward and side scatter represent larger cells with higher complexity, indicative of inflammation. These are gated at p2

Figure 2.

Histogram gated at p1 shows presence of E6/E7 messenger RNA above the 2% cut off

The positive cut off for E6/E7 over-expression is taken at 2% as per the validation criteria used by Curehealth Diagnostics, New Delhi.

Results are expressed in the form of dot plots. Each dot plot shows cells (recorded as signal “events”) of periodontal pocket scraping origin representing forward and side scatter characteristic of squamous epithelial cells. The accompanying histogram shows cells showing overexpression of E6/E7 in the form of a second peak in the histogram.

DISCUSSION

Substantial evidence supports that chronic inflammation is related to and is a key event in the development of cancer.[17,18] Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the supporting structures of the teeth which is characterized by the presence of gingival inflammation, loss of tissue attachment, periodontal pocket formation, and alveolar bone loss around the affected tooth.[19]

Causative agents include Gram-positive and Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria associated with an oral biofilm. Recently, the role of viruses in the pathogenesis of chronic periodontitis is being investigated, including herpes viruses and human papilloma viruses.[20,21,22]

Studies indicate that patients with a history of periodontitis have a higher risk for head and neck carcinomas especially of tongue and oropharynx. Loss of bone around teeth is found to be an independent risk factor for the development of oral carcinoma.[23,24,25]

HPV was the first thought to be involved in the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma in 1983.[26] The high risk HPV types (most often HPV 16 and occasionally HPV-18) identified in HPV positive tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma are similar to those found in cervical cancers.[27] What is of further interest is; there may be a synergy between chronic periodontitis oral HPV infection and head and neck carcinoma.[28]

It is, therefore, of growing importance that HPV has been detected in periodontal pockets as well as gingival sulci of healthy patients. These sites, being in close proximity to the tongue and oropharynx are thought to serve as reservoirs of HPV.[13]

The HPV genome is composed of three major regions: The long control region, the early genes E1-8, and late genes L1-2.[29] E6 and E7 have transforming properties. These proteins have pleiotropic functions, which include transmembrane signaling, regulation of the cell cycle, transformation of established cell lines, immortalization of primary cell line, and regulation of chromosomal stability. The viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins are necessary for malignant conversion. The abilities of high-risk HPV E6 and E7 proteins to associate with the tumor suppressors p53 and pRB, respectively, have been suggested as a mechanism by which these viral proteins induce tumor formation.[30]

HPV's cell cycles are found to be closely associated with differentiation of the epithelial cells it infects.[31] These viruses are known to infect basal and suprabasal cells.

The junctional epithelium of the periodontium is a rapidly differentiating epithelium whose cells are exfoliated throughout the gingival sulcus before they can differentiate.[32] During periodontal disease, pocket formation occurs which is typically associated with a rapid proliferation and migration of the basal and suprabasal cells of the junctional epithelium. Epithelial sites showing these features favor the replication of human papillomaviruses.

Although, a number of studies have been performed, identifying HPV in periodontium,[4,13,33,34] these studies have identified the presence of viral DNA. However, it is now known that integration of HPV DNA into the genomic DNA and its detection is not enough to establish high risk HPV as a potential oncogenic agent. This is because in 15–30% of HPV related squamous cell carcinomas,[20] HPV has been found in episomal form, showing a plasmidic expression of E6, E7.[21]

This study is the first to detect presence or absence of E6, E7 mRNA in human periodontium. Expression of E6/E7 mRNA in cells of marginal periodontium indicates that periodontal pocket could be a reservoir of HPV.

In the present study, four of the eight samples were found have evidence of presence of HPV in the periodontium in the form of E6/E7 mRNA. These results are consistent with previous studies which described detection of HPV in gingival epithelium in patients with periodontitis.[4,33,35] Previously used methods of virus detection included southern blotting.[33] This study is the first to identify the presence or absence of extra chromosomal HPV genetic material in the periodontium to detect the presence or absence of HPV. Detection of E6/E7 transcripts has been shown to be associated with increased sensitivity and specificity as compared to the mere detection of viral DNA when used for detecting precancerous cervical lesions.[30]

One of the samples contained E6/E7 mRNA above the significant 2% cutoff. This 2% cutoff is used as a screening marker for early predictor of active infection in samples of cervical epithelium.

A study by Tezal et al. was conducted in 2009 to test the hypothesis that chronic periodontitis can be a predictor of HPV tumor status in patients of tongue carcinomas. Because of the ability of the investigation used in this study to detect not only the presence of extra chromosomal HPV elements but also their over expression (above 2% cutoff) and finding one sample containing this E6/E7 mRNA above this significant mark, this strengthens this hypothesis. However, the sample size in the present study is limited and long-term follow up of these patients with positive findings is required.

CONCLUSION

Presence of high risk human papilloma viruses in patients diagnosed with chronic periodontitis, not suffering from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in the present day could link periodontitis to HPV related squamous cell carcinoma. Prevalence studies, detecting the presence of HPV in marginal periodontium as well as prospective studies of HPV positive periodontitis patients are required to explore this possible link.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Salazar EL, Mercado E, Calzada L. Human papillomavirus hpv-16 DNA as an epitheliotropic virus that induces hyperproliferation in squamous penile tissue. Arch Androl. 2005;51:327–34. doi: 10.1080/014850190923396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murrah V. Raised lesions with a rough or papillary surface. In: DeLong L, Burkhrt N, editors. General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Christopher Johnson; 2013. pp. 433–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ural A, Arslan S, Ersoz S, Deger B. Verruca vulgaris of the tongue: A case report with a literature review. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2014;14:136–8. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2014.3.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parra B, Slots J. Detection of human viruses in periodontal pockets using polymerase chain reaction. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:289–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Pawlita M, Lissowska J, Kee F, Balaram P, et al. Human papillomavirus and oral cancer: The International Agency for Research on Cancer multicenter study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1772–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernster JA, Sciotto CG, O'Brien MM, Finch JL, Robinson LJ, Willson T, et al. Rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer and the role of oncogenic human papilloma virus. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:2115–28. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31813e5fbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammarstedt L, Lindquist D, Dahlstrand H, Romanitan M, Dahlgren LO, Joneberg J, et al. Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for the increase in incidence of tonsillar cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2620–3. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillison ML, D'Souza G, Westra W, Sugar E, Xiao W, Begum S, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennessey PT, Westra WH, Califano JA. Human papillomavirus and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Recent evidence and clinical implications. J Dent Res. 2009;88:300–6. doi: 10.1177/0022034509333371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klussmann JP, Weissenborn SJ, Wieland U, Dries V, Eckel HE, Pfister HJ, et al. Human papillomavirus-positive tonsillar carcinomas: A different tumor entity? Med Microbiol Immunol. 2003;192:129–32. doi: 10.1007/s00430-002-0126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charfi L, Jouffroy T, de Cremoux P, Le Peltier N, Thioux M, Fréneaux P, et al. Two types of squamous cell carcinoma of the palatine tonsil characterized by distinct etiology, molecular features and outcome. Cancer Lett. 2008;260:72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hormia M, Willberg J, Ruokonen H, Syrjänen S. Marginal periodontium as a potential reservoir of human papillomavirus in oral mucosa. J Periodontol. 2005;76:358–63. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slots J. Human viruses in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2010;53:89–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ndiaye C, Mena M, Alemany L, Arbyn M, Castellsagué X, Laporte L, et al. HPV DNA, E6/E7 mRNA, and p16INK4a detection in head and neck cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1319–31. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Boer MA, Jordanova ES, Kenter GG, Peters AA, Corver WE, Trimbos JB, et al. High human papillomavirus oncogene mRNA expression and not viral DNA load is associated with poor prognosis in cervical cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:132–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shacter E, Weitzman SA. Chronic inflammation and cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2002;16:217–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Listgarten MA. Pathogenesis of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:418–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contreras A, Slots J. Active cytomegalovirus infection in human periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1998;13:225–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Contreras A, Slots J. Herpesviruses in human periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 2000;35:3–16. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035001003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortez-Lopez M, Sandoval-Rivas L, Ortega-Kermedy Z, Cerda-Flores RM. Detection HPV in Mexicans with Periodontitis. Asian Acad Res J Multidiscip. 2014;1:307–15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tezal M, Sullivan MA, Hyland A, Marshall JR, Stoler D, Reid ME, et al. Chronic periodontitis and the incidence of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2406–12. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tezal M, Sullivan MA, Reid ME, Marshall JR, Hyland A, Loree T, et al. Chronic periodontitis and the risk of tongue cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:450–4. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer MS, Joshipura K, Giovannucci E, Michaud DS. A review of the relationship between tooth loss, periodontal disease, and cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:895–907. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9163-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syrjänen K, Syrjänen S, Lamberg M, Pyrhönen S, Nuutinen J. Morphological and immunohistochemical evidence suggesting human papillomavirus (HPV) involvement in oral squamous cell carcinogenesis. Int J Oral Surg. 1983;12:418–24. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(83)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Psyrri A, DiMaio D. Human papillomavirus in cervical and head-and-neck cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:24–31. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tezal M, Sullivan Nasca M, Stoler DL, Melendy T, Hyland A, Smaldino PJ, et al. Chronic periodontitis-human papillomavirus synergy in base of tongue cancers. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:391–6. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris BJ. Cervical human papillomavirus screening by PCR: Advantages of targeting the E6/E7 region. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:1171–7. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yim EK, Park JS. The role of HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins in HPV-associated cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer Res Treat. 2005;37:319–24. doi: 10.4143/crt.2005.37.6.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doorbar J, Egawa N, Griffin H, Kranjec C, Murakami I. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25(Suppl 1):2–23. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bosshardt DD, Lang NP. The junctional epithelium: From health to disease. J Dent Res. 2005;84:9–20. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madinier I, Doglio A, Cagnon L, Lefèbvre JC, Monteil RA. Southern blot detection of human papillomaviruses (HPVs) DNA sequences in gingival tissues. J Periodontol. 1992;63:667–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.8.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horewicz VV, Feres M, Rapp GE, Yasuda V, Cury PR. Human papillomavirus-16 prevalence in gingival tissue and its association with periodontal destruction: A case-control study. J Periodontol. 2010;81:562–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bustos DA, Grenón MS, Benitez M, de Boccardo G, Pavan JV, Gendelman H. Human papillomavirus infection in cyclosporin-induced gingival overgrowth in renal allograft recipients. J Periodontol. 2001;72:741–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.6.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]