Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic surgery has several advantages when compared to open surgery, including faster postoperative recovery and lower pain scores. However, for laparoscopy, a pneumoperitoneum is required to create workspace between the abdominal wall and intraabdominal organs. Increased intraabdominal pressure may also have negative implications on cardiovascular, pulmonary, and intraabdominal organ functionings. To overcome these negative consequences, several trials have been performed comparing low- versus standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum.

Methods

A systematic review of all randomized controlled clinical trials and observational studies comparing low- versus standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum.

Results and conclusions

Quality assessment showed that the overall quality of evidence was moderate to low. Postoperative pain scores were reduced by the use of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum. With appropriate perioperative measures, the use of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum does not seem to have clinical advantages as compared to standard pressure on cardiac and pulmonary function. Although there are indications that low-pressure pneumoperitoneum is associated with less liver and kidney injury when compared to standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum, this does not seem to have clinical implications for healthy individuals. The influence of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum on adhesion formation, anastomosis healing, tumor metastasis, intraocular and intracerebral pressure, and thromboembolic complications remains uncertain, as no human clinical trials have been performed. The influence of pressure on surgical conditions and safety has not been established to date. In conclusion, the most important benefit of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum is lower postoperative pain scores, supported by a moderate quality of evidence. However, the quality of surgical conditions and safety of the use of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum need to be established, as are the values and preferences of physicians and patients regarding the potential benefits and risks. Therefore, the recommendation to use low-pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopy is weak, and more studies are required.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Pneumoperitoneum, Low pressure, Pain, Perioperative conditions

Based on experiments in dogs by Georg Kelling, Hans Christian Jacobaeus was the first to perform a laparoscopic procedure in humans in 1910 [1, 2]. Insufflation of air into the peritoneal cavity created working space between the abdominal wall and the intraabdominal organs. Until the 1960s, the physiological consequences of increased intraabdominal pressure by gas insufflation were poorly understood. In 1966, Kurt Semm introduced an automatic insufflation device capable of monitoring intraabdominal pressure, thereby improving the safety of laparoscopy [3]. Today, intraabdominal pressure is traditionally set at a routine pressure of 12–15 mmHg [4]. Bearing in mind the potential negative impact of pneumoperitoneum (PNP) on cardiopulmonary function and the positive impact on postoperative pain, international guidelines recommend that the use of “the lowest intraabdominal pressure allowing adequate exposure of the operative field rather than a routine pressure” should be used [5]. In literature, low-pressure PNP is generally defined as an intraabdominal pressure of 6–10 mmHg [6–9]. However, in daily clinical practice, usually the intra-abdominal pressure is set at 12–14 mmHg, and for gynecological laparoscopic procedures, sometimes even higher pressures are used. In this systematic review, we will address the risks and benefits of low- versus standard-pressure PNP.

Materials and methods

This review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. The MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases were systematically searched from January 1, 1995 to September 1, 2014, and the search strategy is provided in Table 1. Two authors (DÖ and SP) independently confirmed the eligibility of the studies. To identify other relevant randomized controlled clinical trials, the references of the identified trials and cross references were searched. Only randomized clinical trials (RCT) and cohort studies comparing low- versus standard-pressure PNP were included.

Table 1.

Search Strategy

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (laparoscop* OR coelioscop* OR celioscop* OR peritoneoscop*) AND (pneumoperitoneum OR pneumoperitoneum, Artificial[MeSH] OR insufflation OR insufflation[MeSH]) AND (randomized controlled trial[pt] OR controlled clinical trial[pt] OR randomized [tiab] OR randomly[tiab] OR trial[tiab]) |

| EMBASE | 1. (laparoscop* or coelioscop* or celioscop* or peritoneoscop*).af 2. exp Laparoscopic Surgery/ 3. 1 or 2 4. (pneumoperitoneum or insufflation).af 5. exp Pneumoperitoneum/ 6. 4 OR 5 7. 3 AND 6 8. exp RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS/ 9. 7 and 8 |

| CENTRAL | 1. Laparoscop* OR coelioscop* OR celioscop* OR peritoneoscop* 2. MeSH description Pneumoperitoneum, Artificial, explode all trees 3. MeSH description Insufflation, explode all trees 4. 1 OR 2 OR 3 |

The following characteristics were extracted: author, year of publication, country of hospital, study design, total number of patients, total number of patients in each experimental arm, mean age and standard deviation (SD), gender, mean body mass index (BMI) (SD), type of laparoscopic procedure, and definitions of low and standard pressures.

Outcome measures included: postoperative pain and analgesia consumption, pulmonary and cardiac function, liver and kidney function, thromboembolic complications, adhesion formation, anastomosis healing, intracranial and intraocular pressure, tumor growth and metastases and perioperative conditions, complications, and conversion to open procedure. When enough data were available, a meta-analysis was performed. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager (version 5.2, the Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Data were pooled using random-effects model. Continuous data were expressed as mean difference, and consistency was measured with I2.

Quality assessment of randomized controlled trials was performed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias [10] by two authors (DÖ and SP) independently. The quality of non-randomized trials was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa Rating scale [11]. Two stars were awarded when body mass index (BMI), age, and gender were comparable. The follow-up had to be at least 3 days to score one point on the “follow-up” item. This way, major complications were not missed due to a too short follow-up period. The quality of evidence and strength of recommendation were assessed according to the GRADE approach [12].

Results

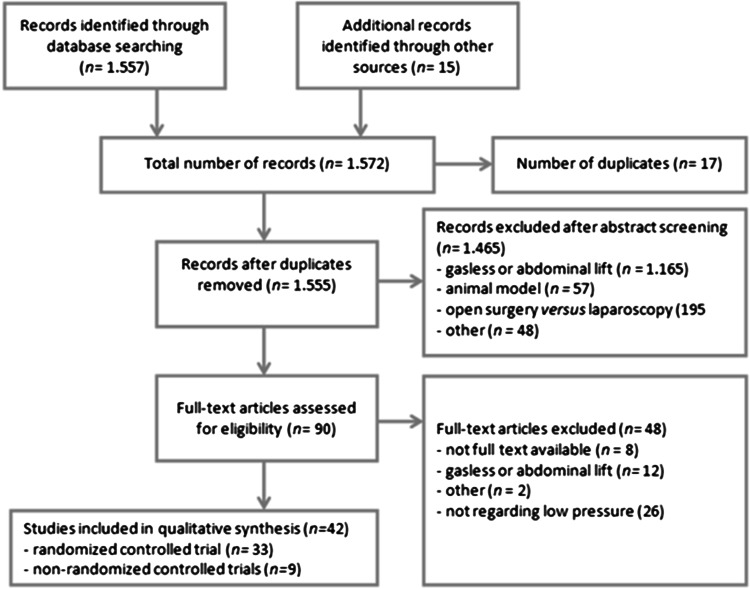

Of the 1572 papers identified at the initial search, 42 were included after abstract and full-text screening (Fig. 1). Characteristics of the included studies are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The quality assessment of the available evidence using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for assessing risk of bias is shown in Tables 4 and 5; in general, the quality of the included studies was low or unclear [10]. For five studies, information that Gurusamy et al. obtained by contacting the authors was reused to supplement the quality assessment. An overview of the results, including quality of evidence according to GRADE, is provided in Table 7 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study search

Table 2.

Characteristics of human randomized controlled trials

| First author | Year of publication | Country | Pressure | Procedure | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barczynski [2] | 2002 | Poland | 7 versus 12 | LC | 74 versus 74 |

| Basgul [13] | 2004 | Turkey | 10 versus 14–15 | LC | 11 versus 11 |

| Bogani [14] | 2014 | Italy | 8 versus 12 | LH | 20 versus 22 |

| Celik [15] | 2004 | Turkey | 8 versus 10 versus 12 versus 14 versus 16 | LC | 20 versus 20 versus 20 versus 20 versus 20 |

| Celik [16] | 2010 | Turkey | 8 versus 12 versus 14 | LC | 20 versus 20 versus 20 |

| Chok [17] | 2006 | China | 7 versus 12 | LC | 20 versus 20 |

| Dexter [18] | 1998 | UK | 7 versus 15 | LC | 10 versus 10 |

| Ekici [19] | 2009 | Turkey | 7 versus 15 | LC | 20 versus 32 |

| Emad Esmat [9] | 2006 | Egypt | 10 versus 14 | LC | 34 versus 37 |

| Eryilmaz [6] | 2011 | Turkey | 10 versus 14 | LC | 20 versus 23 |

| Gupta [20] | 2013 | India | 8 versus 14 | LC | 50 versus 51 |

| Hasukic [21] | 2005 | Bosnia-Herzegovina | 7 versus 14 | LC | 25 versus 25 |

| Ibraheim [7] | 2006 | Saudi Arabia | 6–8 versus 12–14 | LC | 10 versus 10 |

| Joshipura [22] | 2009 | India | 8 versus 12 | ||

| Kandil [23] | 2010 | Egypt | 8 versus 10 versus 12 versus 14 | LC | 25 versus 25 versus 25 versus 25 |

| Kanwer [24] | 2009 | India | 10 versus 14 | LC | 27 versus 28 |

| Karagulle [25] | 2008 | Turkey | 8 versus 12 versus 15 | LC | 14 versus 15 versus 15 |

| Koc [26] | 2005 | Turkey | 10 versus 15 | LC | 25 versus 25 |

| Morino [27] | 1998 | Italy | 10 versus 14 | LC | 10 versus 22 |

| Perrakis [28] | 2003 | Greece | 8 versus 15 | LC | 20 versus 20 |

| Polat [29] | 2003 | Turkey | 10 versus 15 | LC | 12 versus 12 |

| Sandhu [30] | 2009 | Thailand | 7 versus 14 | LC | 70 versus 70 |

| Sarli [31] | 2000 | Italy | 9 versus 13 | LC | 46 versus 44 |

| Schietroma [8] | 2013 | Italy | 6–8 versus 12–14 | LNF | 33 versus 35 |

| Sefr [32] | 2003 | Czech Republic | 10 versus 15 | LC | 15 versus 15 |

| Singla [33] | 2014 | India | 7–8 versus 12–14 | LC | 50 versus 50 |

| Sood [34] | 2006 | India | 8–10 versus 15 | LA | 5 versus 4 |

| Topal [35] | 2011 | Turkey | 10 versus 13 versus 16 | LC | 20 versus 20 versus 20 |

| Torres [36] | 2009 | Poland | 6–8 versus 10–12 | LC | 20 versus 20 |

| Umar [37] | 2011 | India | 8–10 versus 11–13 versus 14 | LC | Unclear |

| Vijayaraghavan [38] | 2014 | India | 8 versus 12 | LC | 22 versus 21 |

| Wallace [39] | 1997 | UK | 7.5 versus 15 | LC | 20 versus 20 |

| Warlé [40] | 2013 | the Netherlands | 7 versus 12 | LDN | 10 versus 10 |

| Yasir [41] | 2012 | India | 8 versus 14 | LC | 50 versus 50 |

LA laparoscopic adrenalectomy, LC laparoscopic cholecystectomy, LDN laparoscopic donor nephrectomy, LH laparoscopic hysterectomy, LNF Laparoscopic nissen fundoplication

Table 3.

Characteristics of non-randomized trials

| First author | Year of publication | Country/state | Pressure | Procedure | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atila [42] | 2009 | Turkey | N/A | LC | 40 |

| Davides [43] | 1999 | UK | 7 versus 10.6 | LC | 50 versus 77 |

| Hawasli [44] | 2003 | USA | 10 versus 15 | LDN | 25 versus 25 |

| Kamine [45] | 2014 | USA | N/A | LA VERSUSP | 9 |

| Kovacs [46] | 2012 | Hungary | 8 versus 13 | LDN | 44 versus 26 |

| Matsuzaki [47] | 2011 | France | 8 versus 12 | LH | 32 versus 36 |

| Park [22] | 2012 | Korea | 10 versus 15 | LCol | 30 |

| Rist [48] | 2001 | Germany | 10 versus 15 | L | 10 |

| Schwarte [38] | 2004 | Germany | 8 versus 12 | DL | 16 |

DL diagnostic laparoscopy, L laparoscopy of the lower abdomen, LA VSP laparoscopy-assisted ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement, LC laparoscopic cholecystectomy, LCol laparoscopic colectomy, LDN laparoscopic donor nephrectomy, LH laparoscopic hysterectomy

Table 4.

Quality assessment of included human randomized controlled trials according to Cochrane

| First author | Random sequence | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Incomplete outcome | Selective reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barczynski [2] | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Basgul [13] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Bogani [14] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Celik [15] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Celik [16] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Chok [17] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Dexter [18] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Ekici [19] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Emad Esmat [9] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Eryilmaz [6] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Gupta [20] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Hasukic [21] | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Ibraheim [7] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Joshipura [22] | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Kandil [23] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Kanwer [24] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Karagulle [25] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Koc [26] | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Morino [27] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Perrakis [28] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Polat [29] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Sandhu [30] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Sarli [31] | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Schietroma [8] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Sefr [32] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Singla [33] | Low | unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Sood [34] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Topal [35] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Torres [36] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Umar [37] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Vijayaraghavan [38] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Wallace [39] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Warlé [40] | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Yasir [41] | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear |

Table 5.

Quality assessment of included non-randomized trials according to Newcastle–Ottawa

| First author | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representiveness | Selection | Ascertainment | Demonstration | Assessment | Follow-up | Adequacy | |||

| Atila [42] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 | ||

| Davides [43] | * | * | * | * | 4 | ||||

| Hawasli [44] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 | ||

| Kamine [45] | * | * | * | ** | * | 6 | |||

| Kovacs [46] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 | ||

| Matsuzaki [49] | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | |||

| Park [50] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 | ||

| Rist [48] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 | ||

| Schwartz [51] | * | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 | ||

Table 7.

Summary of findings and quality of evidence regarding outcome measures that are potentially critical for decision making

| Endpoints | Type of surgery (number of studies) | Outcomes | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | LC (15) | Less pain and lower overall analgesic consumption in the low-pressure group | B |

| Other procedures (6) | Less pain in the low-pressure group | C | |

| Pulmonary function | LC (4) | Although pulmonary compliance seems to be compromised in the standard-pressure group, this has little or no clinical consequences for ASA I and II patients. | B |

| Other procedures(3) | One study describing decreased pulmonary compliance, no clinical consequences described in the other studies | B | |

| Cardiac function | LC (4) | No differences between low and standard-pressure PNP for ASA I and II patients. | B |

| LC (1) | No differences between low- and standard-pressure PNP for ASA III and IV patients. | B | |

| Other procedures (1) | No differences between low- and standard-pressure PNP. | C | |

| Liver function | LC (6) | The rise of AST and ALT is related to intraabdominal pressure, although this is probably not clinically relevant for healthy individuals | B |

| Other procedures (0) | No data | N/A | |

| Kidney function | LC (0) | No data | N/A |

| Other procedures(3) | Decreased urine output and clearance in the standard-pressure group, but no influence on postoperative creatinine after LDN | B | |

| Thromboembolic complications | LC (3) | Inconclusive results | B |

| Other procedures (1) | No significant difference in diameter of common iliac vein | B | |

| Adhesions | Other procedures (0) | No data | N/A |

| Anastomosis healing | Colorectal procedures (1) | No data | N/A |

| Intracranial pressure | LC (0) | No data | N/A |

| Other procedures (1) | PNP increases intracranial pressure in a pressure-dependent way | C | |

| Intraocular pressure | LC | No data | N/A |

| Other procedures | Pneumoperitoneum (standard pressure) increases intraocular pressure as compared to no pneumoperitoneum. | N/A | |

| Tumor growth and metastases | LC | No data | N/A |

| Other procedures | No data | N/A | |

| Inflammation | LC | No significant difference in rise of pro-inflammatory cytokines (although not uniform results in all studies) | B |

| Other procedures | Significant higher concentrations of IL-6, IL-1 and CRP in the standard pressure (1 study) | B | |

| Visibility | LC (1) | Decreased visibility, decreased visibility at suction, decreased space for dissection | B |

| Other (2) | No significant difference in difficulty or progression | B | |

| Safety | LC (20) | No significant differences in incidence of serious adverse events or conversions to open surgery | B |

| Other (3) | No significant differences in incidence of serious adverse events or conversions to open surgery | B |

Quality of evidence and strength of recommendation were assessed according to the GRADE approach

A (high): Randomized trials; or double-upgraded observational studies

B (moderate): Downgraded randomized trials; or upgraded observational studies

C (low): Double-downgraded randomized trials; or observational studies

D (very low): Triple-downgraded randomized trials; or downgraded observational studies; or case series/case reports

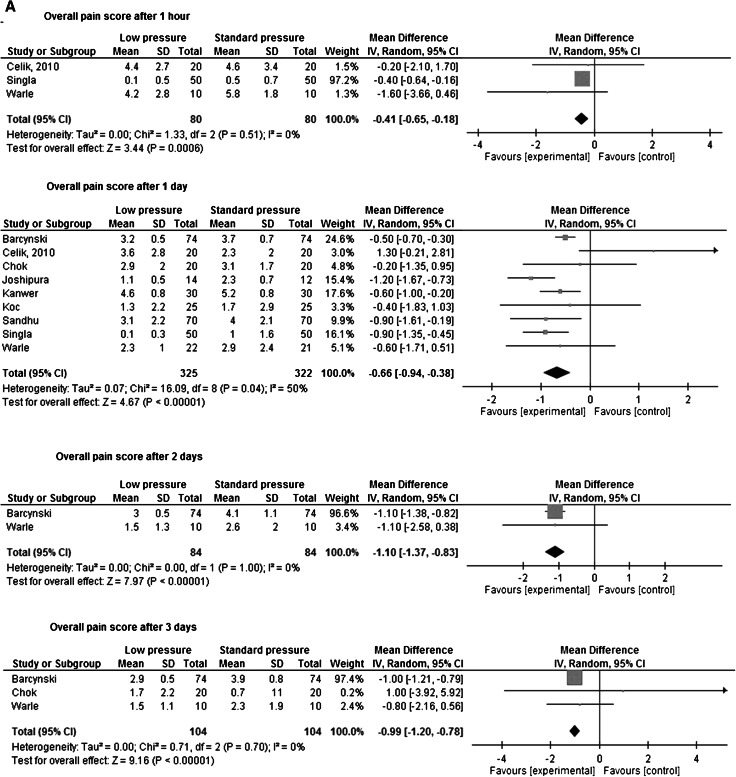

Fig. 2.

A Meta-analysis of overall pain. B Shoulder pain

Pain

A Cochrane review performed by Gurusamy et al. in 2009 regarding elective and emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy showed decreased pain scores during the early postoperative phase. Nevertheless, definite conclusions could not be drawn from this meta-analysis since most studies were at high risk of bias [52]. In the recently updated Cochrane review, pain scores were not included, and it was stated that “pain scores are unvalidated surrogate outcomes for pain in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and several Cochrane systematic reviews have demonstrated that pain scores can be decreased with no clinical implications in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy” [53]. However, in literature there is evidence that a reduction of 1.0–1.5 points on an 0–10 pain scale is a clinically relevant difference [54–57]. In four studies, the effects of low-pressure PNP were assessed in a blinded fashion [22, 31, 38, 40]. In three studies, overall pain scores were assessed and in two studies, and a clinically relevant difference was found at postoperative day 1. From the patients’ perspective, the duration of reduction in postoperative pain is also important. The only blinded study comparing postoperative pain longer than 24 h after surgery is the study by Warlé et al. [40]. In this study, a difference of 0.8 in overall pain score on an 0–10 scale 3 days after surgery was observed. Regarding shoulder pain, in two studies this parameter was assessed, in one study a difference of approximately two points was found up to postoperative day 1 [26], while in the other study mean pain scores of 0.7 and 0.9 were observed [40, 58].

Randomized controlled trials comparing non-cholecystectomy procedures (i.e., laparoscopic donor nephrectomy and laparoscopic gynecologic procedures) also suggests that low-pressure PNP is associated with less postoperative pain [14, 40, 44, 46, 47, 59].

In Table 6a, b, an overview of overall pain scores and shoulder pain in low pressure versus standard pressure is shown. Meta-analysis of pain scores at different time point shows that overall pain was significant lower in the low-pressure group; however, this difference was only clinically relevant after 2 and 3 days. After 1 and 3 days, shoulder pain was significantly lower for the low-pressure group, and this difference was clinically significant after 3 days.

Table 6.

Assessment of (a) overall postoperative pain, (b) shoulder pain

| First author | 1 h | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low pressure | Standard pressure | Low pressure | Standard pressure | Low pressure | Standard pressure | Low pressure | Standard pressure | |

| (a) Overall postoperative pain | ||||||||

| Barcynski [2] | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 3.9 | ||

| Celik [16] | 4.4 | 4.6 | 3.6 | 2.3 | ||||

| Chok [17] | 2.9 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 | ||||

| Joshipura [22] | 1.1 | 2.3 | ||||||

| Kanwer [24] | 4.6 | 5.2 | ||||||

| Koc [26] | 1.3 | 1.7 | ||||||

| Sandhu [30] | 3.1 | 4.0 | ||||||

| Singla [33] | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1.0 | ||||

| Vijavaraghavan [38] | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| Warlé [40] | 4.2 | 5.8 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| (b) Shoulder pain | ||||||||

| Bogani [14] | 0.8 | 5.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ||||

| Esmat [9] | 1.3 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||||

| Kandil [23] | 1.3 and 1.9 | 3.1 and 3.5 | 0.4 and 1.4 | 2.3 and 2.4 | ||||

| Warlé [40] | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| Yasir [41] | 0.2 | 0.6 | ||||||

Pulmonary function

Despite the fact that in one RCT, pulmonary compliance was significantly compromised in the standard-pressure group when compared to low-pressure PNP [50], end tidal CO2, pCO2, oxygen saturation, pO2 and blood gas analyses, including pH, bicarbonate or base excess, were comparable [22, 32, 38–40]. Postoperative pulmonary function tests were evaluated by three RCTs, and no significant differences in pulmonary function tests were observed [22, 25, 38]. No RCTs comparing low- versus standard-pressure PNP in patients with pulmonary comorbidities are performed.

Cardiac function

When comparing cardiac function in low- versus standard-pressure PNP in human trials, most studies comparing heart frequency, cardiac index, and mean arterial pressure did not observe a significant difference [6, 18, 19, 34, 60]. These findings also seem to be applicable for ASA III and IV patients, as Koivusalo et al. [60] compared hemodynamic, renal, and liver parameters in ASA III and IV patients in low-pressure versus standard-pressure PNP and found no significant differences. However, it should be noted that not all studies demonstrated consistent results [37]: Umar et al. observed a significant decrease in mean heart rate and mean systolic blood pressure.

Liver function

Two studies observed a pressure-dependent decrease in hepatic blood flow and enzyme elevations of AST and ALT [21, 27], whereas postoperative bilirubin, γ-GT, and ALP were not or slightly elevated [21, 61–63]. Eryilmaz et al. [6] used indocyanine green elimination tests (ICG-PDR) as a parameter for liver function. In their trial, a significant decrease in ICG-PDR values in the standard pressure (14 mmHg) PNP was observed when compared to the low-pressure group (10 mmHg). In none of the trials, persistent elevation of liver enzymes or liver failure was observed.

Renal function

Human trials comparing renal function during and after low-pressure compared to standard-pressure PNP are scarce. In two RCTs, urine output was lower in the standard-pressure group, but no changes in postoperative creatinine could be demonstrated [40, 44]. Preoperative volume loading before and during PNP can help maintaining renal perfusion [64]. With the exception of a few case reports [65–67], in the postoperative phase, serum creatinine levels, creatinine clearance, and urine output returned to normal in all patients.

Thromboembolic complications

The difference in the incidence of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism during low or normal intra-abdominal pressure has not been described. However, four studies indirectly evaluated the risk of thromboembolic complications. First, Ido et al. [68] demonstrated that blood flow velocity in the femoral vein was significantly reduced during abdominal insufflation, and there was a significant difference when using 5 or 10 mmHg intra-abdominal pressure. Topal et al. [35] assessed different thromboelastographic parameters, e.g., reaction time, maximum amplitude, α-angle, and K time, in low (10 mmHg) versus standard (13 mmHg) and high intra-abdominal pressure (16 mmHg). All parameters were comparable to preoperative values in the 10 mmHg group and the 13 mmHg group. Two other randomized controlled trials observed no significant differences in diameter of the common iliac vein when pressure was increase from, respectively, 10 to 15 and 8 to 12 mmHg [22, 48].

Adhesions

No human trials have been performed comparing adhesion formation in low-pressure versus standard-pressure PNP.

Anastomosis healing

No human randomized controlled trials comparing anastomotic leakage in low-pressure versus standard-pressure PNP have been performed. In one study, low- versus standard-pressure was compared in colorectal procedures; however, the incidence of anastomotic leakage was not recorded [50].

Intracranial pressure

Kamine et al. [45] compared intracranial pressure at different intra-abdominal pressures in nine patients undergoing laparoscopy-assisted ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement. They observed a pressure-dependent increase after abdominal insufflation, and maximum intracranial pressure was 25 cm H2O at an insufflation pressure of 15 mmHg. No trials comparing intracranial pressure in low-pressure versus standard-pressure PNP in humans have been performed.

Intraocular pressure

Although clinical trials in humans have shown that laparoscopic procedures are associated with increased intraocular pressure when compared to open procedures, it remains unclear whether this can solely by attributed to increased intra-abdominal pressure; type of anaesthesia and position of the patient probably also play an important role [69–71]. No clinical trials in humans have been performed comparing intraocular pressure in low- versus normal-pressure PNP.

Tumor growth and metastases

Data from human trials are lacking.

Peri- and postoperative inflammatory response

In five studies, the inflammatory response in low- versus standard-pressure PNP are compared [8, 13, 28, 36, 38]. Schietroma et al. [8] observed a significant decrease in interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and C-reactive protein (CRP); however, this could not be confirmed in the studies performed by Perrakis, Torres, and Vijayaghavan et al. [28, 36, 38]. Basgul et al. [13] observed a significant lower increase in IL-6 up to 24 h after surgery, but higher levels of IL-2 during low-pressure PNP.

Quality of surgical conditions

Because the use of low-pressure PNP might decrease the effective working space, one of the major concerns is risk of intra-abdominal organ injury. Perioperative surgical conditions are reported in three randomized controlled trials [14, 38, 40]. Bogani et al. [14] and Warlé et al. [40] did not observe a significant difference in visualization or progression, while Vijayaraghavan et al. [38] observed a significant decreased in visibility, visibility at suction, and space for dissection in the low-pressure PNP group when compared to standard pressure. Recent evidence indicates that the use of deep neuromuscular blockade may improve the incidence of optimal surgical space condition in laparoscopic cholecystectomy [72].

Safety

With regard to serious adverse events and conversion to open procedure, no significant differences could be demonstrated for laparoscopic cholecystectomy [53, 73]. Recent RCTs comparing other laparoscopic procedures, e.g., laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic donor nephrectomy, and laparoscopic appendectomy, also indicate that low pressure has a comparable incidence of serious adverse events and conversions to open procedures when compared to standard pressure [14, 40, 74]. In all studies mortality was zero; however, it was only scarcely explicitly reported [16–19, 21, 27, 30, 40, 75].

Discussion

Pain after laparoscopic procedures can be divided into three components: referred shoulder pain, superficial or incisional wound pain, and deep intra-abdominal pain [76]. Referred pain is most often attributed to CO2-induced diaphragm and/or phrenic nerve irritation causing referred pain to the C4 dermatoma, stretching of the diaphragm, and/or residual pockets of gas in the abdominal cavity [58, 77]. Deep intra-abdominal pain is mainly caused by bowel traction, stretch of the abdominal wall, and compression of intra-abdominal organs.

Although Gurusamy et al. [53] state that pain reduction does not always have clinical implications, there are several studies stating the importance of a clinically significant reduction in postoperative pain [54, 78]. Relative few number of blinded studies addressed postoperative pain after low-pressure PNP [22, 31, 38, 40]. However, in two of three blinded studies, a clinically relevant difference was found after 1 day. Only one blinded study assessed pain scores beyond 24 h and did not find a clinically relevant difference [40].

Overall inconsistency was minimal since in 15 [2, 9, 14, 16, 17, 22, 23, 31, 33, 38–41, 79, 80] of the 19 [2, 8, 9, 14, 16–18, 23, 24, 26, 28, 30, 33, 39, 41, 54, 79, 80] RCT’s a reduction in pain for low-pressure PNP was found. Reduction in pain scores ranged from 0.2 to 3.0 points on day 1. Except for 1 study [16], there were no studies reporting higher pain scores in patients who underwent low-pressure laparoscopy. Meta-analysis of pain scores showed significant less pain for low-pressure PNP, this difference was clinically relevant after 2 and 3 days.

The establishment of CO2 PNP increases intra-abdominal volume, thereby causing the diaphragm to move cranial. In combination with the fact that muscle relaxation during surgery impairs the excursion of the diaphragm, this can lead to compression of the lower lung lobes, resulting in increased dead space, ventilation perfusion mismatch, and decreased tidal volume [5, 7, 22, 25, 32, 51, 81]. Furthermore, CO2 is a highly soluble gas and is rapidly absorbed from the peritoneal cavity into the circulation. The resulting hypercapnia can only be avoided by compensatory hyperventilation. While low-pressure PNP was beneficial for the compliance of the lungs when compared to standard-pressure PNP, perioperative pulmonary parameters and postoperative pulmonary function tests are comparable, indicating that healthy individuals, with the aid of artificial ventilator adjustments, are able to compensate for pulmonary function reduction.

CO2 PNP can also have an impact on the cardiovascular system. Without preoperative volume loading, mechanical impairment of venous return as a result of inferior caval vein compression can result in reduced preload [37, 82]. Reduced preload can lead to decreased stroke volume and subsequent reduced cardiac output [83]. In addition, CO2 is absorbed in the systemic circulation, which can lead to hypercapnia and therefore stimulates the release of vasopressine and catecholamines and activates the renine–angiotensin–aldosteron system [84–86]. Vasopressine and catecholamines increase the systemic vascular resistance and therefore afterload [87, 88]. Furthermore, hypercapnia-induced acidosis can cause decreased cardiac contractility, sensibilization of myocardium to the arrhythmogenic effects of catecholamines, and systemic vasodilatation [89]. Due to these hemodynamic changes, invasive monitoring is necessary in ASA III and IV patients. These patients should also receive preoperative volume loading. In animal studies, low-pressure PNP is associated with improved cardiac function as compared to standard pressure, reflected by higher mean arterial pressure, cardiac output, and stroke volume [90–94]. However, in a human trial investigating ASA I and II patients, low-pressure PNP does not seem to have significant advantages when compared to standard-pressure PNP for cardiac function. However, no evidence exists regarding the beneficial effects of low pressure on cardiac function in ASA III and IV patients.

Transient elevation of liver enzymes such as AST and ALT after non-complicated cholecystectomy is a well-known finding [95]. This can be caused by cranial retraction of the gallbladder, cauterization of the liver bed, and manipulation of external bile ducts or effects of general anesthesia. However, elevated intra-abdominal pressure itself probably plays a significant part in elevation of liver enzymes. Since normal portal venous pressure is between 7 and 10 mmHg, increase in intra-abdominal pressure above this level reduces portal blood flow and may therefore cause a certain degree of hepatic ischemia [96–98]. Animal studies have shown a pressure-dependent decrease n hepatic blood flow, although this difference was not significant in all studies [93, 99, 100]. Likewise, postoperative AST and ALT were significantly increased when comparing low- versus standard-pressure PNP [101, 102]. For humans, the rise of AST and ALT seems to be related to intra-abdominal pressure, and this does not seem to apply for bilirubin, γ-GT, or ALP. For healthy patients, this is unlikely to have clinical consequences.

PNP is known to induce important changes in the kidneys. Increased intra-abdominal pressure can cause compression of the renal vessels and parenchyma. Reduced renal perfusion causes activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, thereby further decreasing the renal blood flow. Also, several animal studies have reported elevated levels of antidiuretic hormone production (ADH) during increased intra-abdominal pressure, although the mechanism is poorly understood [85, 103]. Despite the fact that the studies were performed with a variety of animals and outcome measures, the results are uniform: Standard-pressure PNP is associated with decreased renal perfusion, urine output, postoperative creatinine, and creatinine clearance [6, 22, 83, 90, 104–109] when compared to low-pressure PNP. For humans, urine output was decreased in the standard-pressure group, but no changes in postoperative creatinine were observed.

No studies have been performed comparing the incidence of deep venous thrombosis in low- versus standard-pressure PNP. Observational studies in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy with standard pressure have demonstrated a decrease in APTT and antithrombin III, suggesting activation of coagulation, and decrease in D-dimer, suggesting activation of fibrinolysis [8, 110–115]. Moreover, others have demonstrated an increase in peripheral vascular resistance and a decrease in flow rate in the leg during the PNP phase when standard-pressure PNP is used [116, 117]. Low-pressure PNP did not significantly alter thromboelastographic profile when compared to standard-pressure PNP [35].

The formation of postoperative peritoneal adhesions is an important complication following gynecological and abdominal surgery, having significant clinical and economic consequences. Surgery causes mesothelial defects, which produces an inflammatory exudate, resulting in the presence of a fibrin mass in the peritoneal cavity [118, 119]. When peritoneal fibrinolytic activity is normal, complete mesothelial regeneration occurs within 8 days. However, due to ischemia or inflammation-induced over-expression of plasminogen activator inhibitors 1 and 2, the peritoneal fibrinolytic activity can be suppressed, leading to incomplete removal of the fibrin mass from the abdominal cavity [120]. When fibrin persists, fibroblast migrates and organizes in adhesions [121].

The mechanism of adhesion formation as a consequence of increased abdominal pressure is unclear, but the most plausible explanation is hypoxemia caused by mechanical compression of the capillary bed. Possible effects of anoxaemia in the mesothelium include the induction of angiogenic factors, e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor [122] or attraction of monocytes from the circulation [123].

CO2 itself also seems to be an important factor in adhesion formation: adhesion formation decreased with the addition of 2–4 % oxygen [124, 125]. This can be explained by the fact that local hypercapnia induces acidosis and an impaired microcirculation [126, 127]. Two animal studies have been performed comparing adhesion formation in low- versus standard-pressure PNP. Rosch et al. [128] did not observe a difference in adhesion formation when comparing low- versus standard-pressure PNP after mesh implantation in chinchilla rabbits. On the contrary, Yesildaglar et al. [129] compared the adhesion scores in New Zealand rabbits following laser and bipolar lesions during endoscopic surgery and observed significant higher adhesion scores in the high intra-abdominal pressure group. Since Rosch et al. compared 3 versus 6 mmHg and Yesildaglar et al. compared 5 versus 20 mmHg, this might suggest that the significant difference observed by Yesildaglar et al. was caused by a greater pressure difference.

One human study suggests that low-pressure PNP minimizes the adverse effects on surgical peritoneal environment as measured by connective tissue growth factors, inflammatory cytokines, and cytotoxicity [49].

No human studies have been performed regarding the effects of low-pressure PNP on adhesion formation.

Anastomotic leakage continues to be a catastrophic complication of gastrointestinal surgery. Increased in-abdominal pressure diminishes intra-abdominal blood flow and could thereby impair the healing of anastomosis [130–132]. Animal studies have shown that anastomosis bursting pressure has an inverse correlation with intra-abdominal pressure [29, 133, 134]. However, it must be emphasized that some of the applied pressures are substantially higher than pressures that are normally used for laparoscopy. Moreover, in most studies the animals underwent open surgery via laparotomy after a period of abdominal insufflation, so the actual surgery on the intestines was performed after the PNP.

Intracranial pressure can be increased by elevated intraabdominal pressure. Increased intraabdominal pressure displaces the diaphragm cranially, thereby increasing intrathoracic pressure. This in turn leads to a reduction in venous drainage of the central nervous system, which causes an increase in cerebrospinal fluid and subsequently intracranial pressure [135–138]. In addition, absorption of carbon dioxide during the PNP phase can lead to hypercapnia, which causes reflex vasodilatation in the central nervous system and can therefore increase intracranial pressure [135].

Studies performed in swine indicate that there is a significant and linear increase in intracranial pressure with intraabdominal pressure [139].

Increase in intraocular pressure during laparoscopy is probably related to an increase in central venous pressure, caused by increased intrathoracic pressure [140–142]. Persistently increased intraocular pressure can lower ocular perfusion pressure and thereby cause progressive ischemic damage to the optic nerve. An animal study comparing the effect of low pressure (defined as 10 mmHg) to standard pressure (20 mmHg) in rabbits with α-chymotrypsin-induced glaucoma observed no significant increase in intraocular pressure after the start of PNP. However, intraocular pressure significantly increased with PNP in the head-down position, although it remained within the diurnal range [143]. A subsequent study did not observe any differences in terms of retinal layer organization and the distribution of intracellular vimentin and actin [144].

There are indications from animal studies that CO2 PNP is associated with tumor growth and metastases [145–147]. For instance, local and systemic hypercapnia reduces the phagocytic activity of macrophages, thereby stimulating growth of tumor cells [94, 148, 149]. Others suggested that increased intraabdominal pressure is associated with increased expression of genes associated with peritoneal tumor dissemination [150]. Results of animal studies comparing the development of liver and peritoneal metastases in low- versus standard-pressure PNP are inconclusive [151–157]. This can be explained by the used variety of animals, definition of low and standard pressure, and type of animal model. In most animal models, a tumor cell spillage model is used, in which cells are introduced at the time of surgery; however, this model does not reflect the clinical situation in which surgery is being performed on preexisting tumors.

IL-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine secreted by T cells and macrophages during infection and after tissue damage; CRP is an acute-phase protein that increases after IL-6 section. Both markers are an indication for the degree of tissue damage. Schietroma et al. suggested that low-pressure PNP was associated with significantly lower postoperative IL-6 and CRP. However, this could not be confirmed in four other studies.

PNP during laparoscopy is used to create workspace between the abdominal wall and intraabdominal organs. The major determinant of the amount of pressure that is required for adequate surgical conditions is the compliance of the abdominal wall. For example, in obese patients higher pressures are required to obtain adequate workspace and exposure of the surgical field. The compliance of the abdominal wall can be increased significantly by the application of a deep neuromuscular block. Furthermore, the use of deep neuromuscular block might increase intraabdominal space [158]. A recently performed systematic review suggests that the possible negative effects of low-pressure PNP on perioperative conditions might be overcome by the use of deep neuromuscular block, defined as PTC ≥ 1 to TOF 0, compared to moderate neuromuscular block [159].

All human studies included in this review switched directly from low to standard pressure in case of insufficient surgical conditions [9, 22, 24, 28, 30]. However, a stepwise increase in intraabdominal pressure guided by the quality of surgical field may be an ideal approach to identify the lowest possible pressure that is required to obtain adequate quality of the surgical conditions. Further research is required to investigate whether this approach leads to the use of lower intraabdominal pressures without compromising surgical conditions, and thus safety.

The design and implementation of the studies are the major limitations of this review. This was the main reason for downgrading the quality of evidence. Regarding cohort studies, all studies scored 4–7 points on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Also, it must be stated that the majority of the RCT’s was not registered in a trial registration.

Conclusions and general recommendation (grade approach)

The first determinant of the strength of a recommendation is the balance between desirable and undesirable consequences of low-pressure PNP [160]. The use of low-pressure PNP decreases postoperative pain and analgesic consumption. With adequate pre- and perioperative measures, e.g., preoperative volume loading and artificial hyperventilation, the use of low- or standard-pressure PNP does not seem to have a major impact on cardiac or pulmonary functioning. Low-pressure PNP seems to improve peri- and postoperative dysfunction of liver and kidneys, although this is probably not clinically relevant for healthy patients. The effects of low-pressure PNP on thromboembolic complications, adhesions, tumor growth and metastases, intraocular, and intracranial need to be further specified. Until now, it is unclear whether low-pressure PNP procedures deteriorate surgical conditions; however, there does not seem to be an association with serious adverse events or conversion to open surgery. Regarding safety, Gurusamy et al. concluded that the safety of low pressure during laparoscopic cholecystectomy needs to be established [54]. Since the evidence for the use of low pressure during other laparoscopic procedures is limited, the general conclusion should be that safety of low pressure should be pursued in new clinical trials.

The second determinant is the quality of evidence, which is shown in Table 7. In general the quality of evidence was moderate to low.

Thirdly, values and preferences of physicians and patients regarding their attitude toward the use of low-pressure PNP and its potential beneficial effects have not been investigated.

The final determinant is costs. Decreasing intraabdominal pressure might prolong operation time and subsequently increase costs of the procedure. Indeed, in the Cochrane SRMA operation time was not significantly prolonged during laparoscopic cholecystectomy with low-pressure PNP (MD 1.51, 95 % CI 0.07–2.94, I2 = 0 %). In the same review, however, there was a tendency toward shorter hospital stay in the low-pressure group (MD −0.30, 95 % CI −0.63 to 0.02, I2 = 88 %) [53].

In summary, clinically the most important benefit of low-pressure PNP is lower postoperative pain scores. The cardiopulmonary consequences are comparable when for low- versus standard-pressure PNP in healthy patients; however, for ASA III and IV patients further studies are necessary. Moreover, safety of low-pressure PNP has to be established and the quality of evidence is moderate to low. Furthermore, no evidence exists on the value and preferences of physicians and patients regarding the potential benefits and risks of low-pressure PNP. Finally, there is no indication that the use of low-pressure PNP leads to increased healthcare costs. Altogether, we conclude that the recommendation to use low-pressure PNP is weak and that more studies are required to establish the safety of low-pressure PNP and to explore the values and preferences of physicians and patients.

Disclosures

Denise M. D. Özdemir-van Brunschot, Kees C. J. H. M. van Laarhoven, Gert-Jan Scheffer, Sjaak Pouwels, Kim E. Wever and Michiel C. Warlé have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hatzinger M, et al. Hans Christian Jacobaeus: inventor of human laparoscopy and thoracoscopy. J Endourol. 2006;20(11):848–850. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barczynski M, Herman RM. A prospective randomized trial on comparison of low-pressure (LP) and standard-pressure (SP) pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(4):533–538. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litynski GS. Kurt Semm and an automatic insufflator. JSLS. 1998;2(2):197–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hypolito OH, et al. Creation of pneumoperitoneum: noninvasive monitoring of clinical effects of elevated intraperitoneal pressure for the insertion of the first trocar. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(7):1663–1669. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0827-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neudecker J, et al. The European Association for Endoscopic Surgery clinical practice guideline on the pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(7):1121–1143. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eryilmaz HB, et al. The effects of different insufflation pressures on liver functions assessed with LiMON on patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Sci World J. 2012;2012:172575. doi: 10.1100/2012/172575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibraheim OA, et al. Lactate and acid base changes during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2006;18(4):757–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schietroma M, et al. Changes in the blood coagulation, fibrinolysis, and cytokine profile during laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(7):1090–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8819-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esmat ME, et al. Combined low pressure pneumoperitoneum and intraperitoneal infusion of normal saline for reducing shoulder tip pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2006;30(11):1969–1973. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0752-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JPT (ed) (2008) Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of intervention. Version 5.0.1. Cochrane Collaboration

- 11.Wells GA, O.C.D., Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P, The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analysis

- 12.Guyatt GH, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basgul E, et al. Effects of low and high intra-abdominal pressure on immune response in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(12):1888–1891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bogani G, et al. Low vs standard pneumoperitoneum pressure during laparoscopic hysterectomy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.12.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celik V, et al. Effect of intra-abdominal pressure level on gastric intramucosal pH during pneumoperitoneum. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2004;14(5):247–249. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Celik AS, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and postoperative pain: is it affected by intra-abdominal pressure? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20(4):220–222. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181e21bd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chok KS, et al. Prospective randomized trial on low-pressure versus standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum in outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16(6):383–386. doi: 10.1097/01.sle.0000213748.00525.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dexter SP, et al. Hemodynamic consequences of high- and low-pressure capnoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13(4):376–381. doi: 10.1007/s004649900993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekici Y, et al. Effect of different intra-abdominal pressure levels on QT dispersion in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(11):2543–2549. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta R, et al. Effects of varying intraperitoneal pressure on liver function tests during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23(4):339–342. doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasukic S. Postoperative changes in liver function tests: randomized comparison of low- and high-pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(11):1451–1455. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshipura VP, et al. A prospective randomized, controlled study comparing low pressure versus high pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19(3):234–240. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181a97012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandil TS, El Hefnawy E. Shoulder pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: factors affecting the incidence and severity. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20(8):677–682. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanwer DB, et al. Comparative study of low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy—a randomised controlled trial. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009;30(3):171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karagulle E, et al. The effects of different abdominal pressures on pulmonary function test results in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18(4):329–333. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31816feee9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koc M, et al. Randomized, prospective comparison of postoperative pain in low-versus high-pressure pneumoperitoneum. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(8):693–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morino M, Giraudo G, Festa V. Alterations in hepatic function during laparoscopic surgery. An experimental clinical study. Surg Endosc. 1998;12(7):968–972. doi: 10.1007/s004649900758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perrakis E, et al. Randomized comparison between different insufflation pressures for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13(4):245–249. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200308000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polat C, et al. The effects of increased intraabdominal pressure on colonic anastomoses. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(9):1314–1319. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandhu T, et al. Low-pressure pneumoperitoneum versus standard pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, a prospective randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(5):1044–1047. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarli L, et al. Prospective randomized trial of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum for reduction of shoulder-tip pain following laparoscopy. Br J Surg. 2000;87(9):1161–1165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sefr R, Puszkailer K, Jagos F. Randomized trial of different intraabdominal pressures and acid-base balance alterations during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(6):947–950. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singla S, et al. Pain management after laparoscopic cholecystectomy—a randomized prospective trial of low pressure and standard pressure pneumoperitoneum. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(2):92–94. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7782.4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sood J, et al. Laparoscopic approach to pheochromocytoma: is a lower intraabdominal pressure helpful? Anesth Analg. 2006;102(2):637–641. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000184816.00346.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Topal A, et al. The effects of 3 different intra-abdominal pressures on the thromboelastographic profile during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21(6):434–438. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182397863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres K, et al. A comparative study of angiogenic and cytokine responses after laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed with standard- and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(9):2117–2123. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Umar A, Mehta KS, Mehta N. Evaluation of hemodynamic changes using different intra-abdominal pressures for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(4):284–289. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0484-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vijayaraghavan N, et al. Comparison of standard-pressure and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a double blinded randomized controlled study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24(2):127–133. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182937980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallace DH, et al. Randomized trial of different insufflation pressures for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1997;84(4):455–458. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800840408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warle MC, et al. Low-pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic donor nephrectomy to optimize live donors’ comfort. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(4):E478–E483. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yasir M, et al. Evaluation of post operative shoulder tip pain in low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgeon. 2012;10(2):71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atila K, et al. What is the role of the abdominal perfusion pressure for subclinical hepatic dysfunction in laparoscopic cholecystectomy? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19(1):39–44. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davides D, et al. Routine low-pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13(9):887–889. doi: 10.1007/s004649901126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawasli A, et al. The effect of pneumoperitoneum on kidney function in laparoscopic donor nephrectomy. Am Surg. 2003;69(4):300–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamine TH, Papavassiliou E, Schneider BE. Effect of abdominal insufflation for laparoscopy on intracranial pressure. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(4):380–382. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kovacs JB, et al. Deviceless low-pressure operation; a cost-effective way to reduce CO2-induced barotrauma during hand-assisted laparoscopic donor nephrectomy. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(7):2136–2138. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuzaki S, et al. Impact of the surgical peritoneal environment on pre-implanted tumors on a molecular level: a syngeneic mouse model. J Surg Res. 2010;162(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rist M, et al. Influence of pneumoperitoneum and patient positioning on preload and splanchnic blood volume in laparoscopic surgery of the lower abdomen. J Clin Anesth. 2001;13(4):244–249. doi: 10.1016/S0952-8180(01)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuzaki S, et al. Impact of intraperitoneal pressure of a CO2 pneumoperitoneum on the surgical peritoneal environment. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(6):1613–1623. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park JS, et al. Effects of pneumoperitoneal pressure and position changes on respiratory mechanics during laparoscopic colectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012;63(5):419–424. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2012.63.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwarte LA, et al. Moderate increase in intraabdominal pressure attenuates gastric mucosal oxygen saturation in patients undergoing laparoscopy. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(5):1081–1087. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gurusamy KS, Samraj K, Davidson K. Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD006930. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006930.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gurusamy KS, Vaughan J, Davidson BR. Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD006930. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006930.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kendrick DB, Strout TD. The minimum clinically significant difference in patient-assigned numeric scores for pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23(7):828–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cepeda MS, et al. What decline in pain intensity is meaningful to patients with acute pain? Pain. 2003;105(1–2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly AM. The minimum clinically significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score does not differ with severity of pain. Emerg Med J. 2001;18(3):205–207. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farrar JT, et al. Defining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measures. Pain. 2000;88(3):287–294. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donatsky AM, Bjerrum F, Gogenur I. Surgical techniques to minimize shoulder pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(7):2275–2282. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Topcu HO, et al. A prospective randomized trial of postoperative pain following different insufflation pressures during gynecologic laparoscopy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koivusalo AM, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy with carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum is safe even for high-risk patients. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(1):61–67. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen NT, et al. Comparison of postoperative hepatic function after laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass. Am J Surg. 2003;186(1):40–44. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(03)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sakorafas G, et al. Elevation of serum liver enzymes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. N Z Med J. 2005;118(1210):U1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Andrei VE, et al. Liver enzymes are commonly elevated following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: is elevated intra-abdominal pressure the cause? Dig Surg. 1998;15(3):256–259. doi: 10.1159/000018624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mertens zur Borg IR, et al. Beneficial effects of a new fluid regime on kidney function of donor and recipient during laparoscopic v open donor nephrectomy. J Endourol. 2007;21(12):1509–1515. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben-David B, Croitoru M, Gaitini L. Acute renal failure following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report. J Clin Anesth. 1999;11(6):486–489. doi: 10.1016/S0952-8180(99)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Briscoe JH, Bahal V (2012) Acute renal failure following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BMJ Case Rep 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Apostolou T, et al. Severe acute renal failure in a 19-year-old woman following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Nephrol. 2004;61(6):444–447. doi: 10.5414/CNP61444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ido K, et al. Femoral vein stasis during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: effects of graded elastic compression leg bandages in preventing thrombus formation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(2):151–155. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(95)70072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hwang JW, et al. Does intraocular pressure increase during laparoscopic surgeries? It depends on anesthetic drugs and the surgical position. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23(2):229–232. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828a0bba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mowafi HA, Al-Ghamdi A, Rushood A. Intraocular pressure changes during laparoscopy in patients anesthetized with propofol total intravenous anesthesia versus isoflurane inhaled anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(2):471–474. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000067532.56354.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoo YC, et al. Increase in intraocular pressure is less with propofol than with sevoflurane during laparoscopic surgery in the steep Trendelenburg position. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61(4):322–329. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Staehr-Rye AK, et al. Surgical space conditions during low-pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy with deep versus moderate neuromuscular blockade: a randomized clinical study. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(5):1084–1092. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hua J, et al. Low-pressure versus standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2014;208(1):143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cravello L, et al. Laparoscopic surgery in gynecology: randomized prospective study comparing pneumoperitoneum and abdominal wall suspension. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;83(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(98)00239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karagulle E, et al. Effects of the application of intra-abdominal low pressure on laparoscopic cholecystectomy on acid-base equilibrium. Int Surg. 2009;94(3):205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bisgaard T, et al. Characteristics and prediction of early pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pain. 2001;90(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsimoyiannis EC, et al. Intraperitoneal normal saline infusion for postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 1998;22(8):824–828. doi: 10.1007/s002689900477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Todd KH, et al. Clinical significance of reported changes in pain severity. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(4):485–489. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(96)70238-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ibraheim OA, et al. Lactate and acid base changes during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2006;18(4):757–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barczynski M, Herman RM. Low-pressure pneumoperitoneum combined with intraperitoneal saline washout for reduction of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(9):1368–1373. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Suh MK, et al. The effect of pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg position on respiratory mechanics during pelviscopic surgery. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59(5):329–334. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2010.59.5.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alfonsi P, et al. Cardiac function during intraperitoneal CO2 insufflation for aortic surgery: a transesophageal echocardiographic study. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(5):1304–1310. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000202473.17453.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kelman GR, et al. Caridac output and arterial blood-gas tension during laparoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 1972;44(11):1155–1162. doi: 10.1093/bja/44.11.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O’Leary E, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: haemodynamic and neuroendocrine responses after pneumoperitoneum and changes in position. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76(5):640–644. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mann C, et al. The relationship among carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum, vasopressin release, and hemodynamic changes. Anesth Analg. 1999;89(2):278–283. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stone J, et al. Hemodynamic and hormonal changes during pneumoperitoneum and trendelenburg positioning for operative gynecologic laparoscopy surgery. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5(4):155. doi: 10.1016/S1068-607X(98)00043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arnolda L, McGrath BP, Johnston CI. Vasopressin and angiotensin II contribute equally to the increased afterload in rabbits with heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1991;25(1):68–72. doi: 10.1093/cvr/25.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arnolda L, et al. Vasoconstrictor role for vasopressin in experimental heart failure in the rabbit. J Clin Invest. 1986;78(3):674–679. doi: 10.1172/JCI112626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Feig BW, et al. Pharmacologic intervention can reestablish baseline hemodynamic parameters during laparoscopy. Surgery. 1994;116(4):733–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lindstrom P, et al. Effects of increased intra-abdominal pressure and volume expansion on renal function in the rat. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(11):2269–2277. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perry Y, et al. Pressure-related hemodynamic effects of CO2 pneumoperitoneum in a model of acute cardiac failure. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2003;13(6):341–347. doi: 10.1089/109264203322656388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shuto K, et al. Hemodynamic and arterial blood gas changes during carbon dioxide and helium pneumoperitoneum in pigs. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(11):1173–1178. doi: 10.1007/BF00210922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yokoyama Y, et al. Hepatic vascular response to elevated intraperitoneal pressure in the rat. J Surg Res. 2002;105(2):86–94. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Volz J, et al. Pathophysiologic features of a pneumoperitoneum at laparoscopy: a swine model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(1 Pt 1):132–140. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70385-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guven HE, Oral S. Liver enzyme alterations after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2007;16(4):391–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jakimowicz J, Stultiens G, Smulders F. Laparoscopic insufflation of the abdomen reduces portal venous flow. Surg Endosc. 1998;12(2):129–132. doi: 10.1007/s004649900612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sato K, Kawamura T, Wakusawa R. Hepatic blood flow and function in elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg. 2000;90(5):1198–1202. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200005000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schilling MK, et al. Splanchnic microcirculatory changes during CO2 laparoscopy. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184(4):378–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hashikura Y, et al. Effects of peritoneal insufflation on hepatic and renal blood flow. Surg Endosc. 1994;8(7):759–761. doi: 10.1007/BF00593435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sanchez-Etayo G, et al. Effect of intra-abdominal pressure on hepatic microcirculation: implications of the endothelin-1 receptor. J Dig Dis. 2012;13(9):478–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2012.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nesek-Adam V, et al. Aminotransferases after experimental pneumoperitoneum in dogs. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48(7):862–866. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-5172.2004.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li J, et al. Two clinically relevant pressures of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum cause hepatic injury in a rabbit model. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(31):3652–3658. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i31.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Viinamki O, Punnonen R. Vasopressin release during laparoscopy: role of increased intra-abdominal pressure. Lancet. 1982;1(8264):175–176. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rosin D, et al. Low-pressure laparoscopy may ameliorate intracranial hypertension and renal hypoperfusion. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2002;12(1):15–19. doi: 10.1089/109264202753486876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Khoury W, et al. The hemodynamic effects of CO2-induced pressure on the kidney in an isolated perfused rat kidney model. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18(6):573–578. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181875ba4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bishara B, et al. Impact of pneumoperitoneum on renal perfusion and excretory function: beneficial effects of nitroglycerine. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(3):568–576. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9881-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kirsch AJ, et al. Renal effects of CO2 insufflation: oliguria and acute renal dysfunction in a rat pneumoperitoneum model. Urology. 1994;43(4):453–459. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lindstrom P, et al. Blood flow distribution during elevated intraperitoneal pressure in the rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177(2):149–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hejazi M, et al. Evaluation of effects of intraperitoneal CO2 pressure in laparoscopic operations on kidney, pancreas, liver and spleen in dogs. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(9):809–812. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.7805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Garg PK, et al. Alteration in coagulation profile and incidence of DVT in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Surg. 2009;7(2):130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Prisco D, et al. Videolaparoscopic cholecystectomy induces a hemostasis activation of lower grade than does open surgery. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(2):170–174. doi: 10.1007/s004649900093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Papaziogas B, et al. Modifications of coagulation and fibrinolysis mechanism in laparoscopic vs. open cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(77):1335–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Marakis G, et al. Changes in coagulation and fibrinolysis during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16(6):582–586. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Martinez-Ramos C, et al. Changes in hemostasis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13(5):476–479. doi: 10.1007/s004649901016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Diamantis T, et al. Alterations of hemostasis after laparoscopic and open surgery. Hematology. 2007;12(6):561–570. doi: 10.1080/10245330701554623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Andersson LE, et al. Are there changes in leg vascular resistance during laparoscopic cholecystectomy with CO2 pneumoperitoneum? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49(3):360–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gulec B, et al. Lower extremity venous changes in pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(10):904–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rodgers KE, diZerega GS. Function of peritoneal exudate cells after abdominal surgery. J Invest Surg. 1993;6(1):9–23. doi: 10.3109/08941939309141188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Drollette CM, Badawy SZ. Pathophysiology of pelvic adhesions. Modern trends in preventing infertility. J Reprod Med. 1992;37(2):107–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Holmdahl L, et al. Depression of peritoneal fibrinolysis during operation is a local response to trauma. Surgery. 1998;123(5):539–544. doi: 10.1067/msy.1998.86984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Molinas CR, et al. Role of the plasminogen system in basal adhesion formation and carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum-enhanced adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in transgenic mice. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(1):184–192. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wiczyk HP, et al. Pelvic adhesions contain sex steroid receptors and produce angiogenesis growth factors. Fertil Steril. 1998;69(3):511–516. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)00529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zeyneloglu HB, et al. The role of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in intraperitoneal adhesion formation. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(5):1194–1199. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.5.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Molinas CR, Koninckx PR. Hypoxaemia induced by CO(2) or helium pneumoperitoneum is a co-factor in adhesion formation in rabbits. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(8):1758–1763. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.8.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Molinas CR, et al. Peritoneal mesothelial hypoxia during pneumoperitoneum is a cofactor in adhesion formation in a laparoscopic mouse model. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(3):560–567. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)01964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Taskin O, et al. The effects of duration of CO2 insufflation and irrigation on peritoneal microcirculation assessed by free radical scavengers and total glutathion levels during operative laparoscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5(2):129–133. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(98)80078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Taskin O, et al. Adhesion formation after microlaparoscopic and laparoscopic ovarian coagulation for polycystic ovary disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6(2):159–163. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(99)80095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rosch R, et al. Impact of pressure and gas type on adhesion formation and biomaterial integration in laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(11):3605–3612. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1766-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Yesildaglar N, Koninckx PR. Adhesion formation in intubated rabbits increases with high insufflation pressure during endoscopic surgery. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(3):687–691. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Khoury W, et al. Renal apoptosis following carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum in a rat model. J Urol. 2008;180(4):1554–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chiu AW, et al. The impact of pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum, and gasless laparoscopy on the systemic and renal hemodynamics. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181(5):397–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bongard F, et al. Adverse consequences of increased intra-abdominal pressure on bowel tissue oxygen. J Trauma. 1995;39(3):519–524. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199509000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Tytgat SH, Rijkers GT, van der Zee DC. The influence of the CO(2) pneumoperitoneum on a rat model of intestinal anastomosis healing. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(6):1642–1647. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2086-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Polat C, et al. The effect of NG-nitro l-arginine methyl ester on colonic anastomosis after increased intra-abdominal pressure. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392(2):197–202. doi: 10.1007/s00423-006-0088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Schob OM, et al. A comparison of the pathophysiologic effects of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and helium pneumoperitoneum on intracranial pressure. Am J Surg. 1996;172(3):248–253. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Rosenthal RJ, et al. Intracranial pressure. Effects of pneumoperitoneum in a large-animal model. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(4):376–380. doi: 10.1007/s004649900367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rosenthal RJ, et al. Effects of hyperventilation and hypoventilation on PaCO2 and intracranial pressure during acute elevations of intraabdominal pressure with CO2 pneumoperitoneum: large animal observations. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187(1):32–38. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(98)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hanel F, et al. Effects of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum on cerebral hemodynamics in pigs. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2001;13(3):222–226. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Josephs LG, et al. Diagnostic laparoscopy increases intracranial pressure. J Trauma. 1994;36(6):815–818. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199406000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]