Abstract

Motivation: The advent of new genomic technologies has resulted in the production of massive data sets. Analyses of these data require new statistical and computational methods. In this article, we propose one such method that is useful in selecting explanatory variables for prediction of a binary response. Although this problem has recently been addressed using penalized likelihood methods, we adopt a Bayesian approach that utilizes a mixture of non-local prior densities and point masses on the binary regression coefficient vectors.

Results: The resulting method, which we call iMOMLogit, provides improved performance in identifying true models and reducing estimation and prediction error in a number of simulation studies. More importantly, its application to several genomic datasets produces predictions that have high accuracy using far fewer explanatory variables than competing methods. We also describe a novel approach for setting prior hyperparameters by examining the total variation distance between the prior distributions on the regression parameters and the distribution of the maximum likelihood estimator under the null distribution. Finally, we describe a computational algorithm that can be used to implement iMOMLogit in ultrahigh-dimensional settings () and provide diagnostics to assess the probability that this algorithm has identified the highest posterior probability model.

Availability and implementation: Software to implement this method can be downloaded at: http://www.stat.tamu.edu/∼amir/code.html.

Contact: wwang7@mdanderson.org or vjohnson@stat.tamu.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

Recent developments in bioinformatics and cancer genomics have made it possible to measure thousands of genomic variables that might be associated with the manifestation of cancer. The availability of such data has resulted in a pressing need for the development of statistical methods to use these data to identify variables that are associated with binary outcomes (e.g. cancer or control, survival or death). The topic of this article is a statistical model for identifying, from a large number p of potential feature vectors, a sparse subset that are useful in predicting a binary outcome vector. Throughout this article, we assume that the binary vector of interest is denoted by y, and that the matrix of potential explanatory variables is denoted by X. Letting denote the submatrix of X containing the ‘true’ predictors, we assume that

| (1) |

where F denotes a known binary link function (assumed to be the logistic distribution in what follows), and is the n vector of success probabilities for y. The regression coefficient represents the non-zero regression effect for each column of in predicting . The primary statistical challenge addressed in this article is the selection of the submatrix to be used for the prediction of .

A number of related methods have been proposed to address this problem. These include the LASSO (Tibshirani, 1996), which is a penalized likelihood method that maximizes a product of the binary likelihood function implied by (1) and a constraint on the sum of the absolute value of components of the regression coefficient . A closely related method called Smoothly Clipped Absolute Deviation (SCAD) (Fan and Li, 2001) uses a non-convex penalty function and has been demonstrated to have certain oracle properties in idealized asymptotic settings. Other penalized likelihood functions include the adaptive LASSO (Zou, 2006) and the Dantzig selector (Candes and Tao, 2007); these methods share asymptotic properties similar to SCAD.

In ultrahigh-dimensions (), an effective computational technique for implementing the techniques described above is the Iterative Sure Independence Screening (ISIS) procedure (Fan and Lv, 2008), which iteratively performs a correlation screening step to reduce the number of explanatory variables so that penalized likelihood methods can be applied. ISIS has been used in conjunction with several penalized likelihood methods—including adaptive LASSO (Zou, 2006), the Dantzig Selector (Candes and Tao, 2007), and SCAD (Fan and Li, 2001)—to perform model selection.

A number of Bayesian methods have also been proposed for variable selection. Notable among these are the approaches proposed by George and McCulloch (1997), which used a mixture-of-normals approximation to spike-and-slab priors on the regression coefficients. Lee et al. (2003) proposed a hierarchical probit model along with MCMC based stochastic search to perform gene selection in high-dimensional settings using a latent response variable and Gaussian priors on model coefficients. West et al. (2000) provided a Bayesian approach to this problem employing singular value regression and classes of informative prior distributions to estimate coefficients in high-dimensional settings. Liang et al. (2008) studied mixtures of g priors for Bayesian variable selection as an alternative to default g priors to overcome several consistency issues associated with the default g prior densities. Along more similar lines, Rossell et al. (2013) studied the utilization of non-local priors in Bayesian classifiers where they also address the problem of identifying variables with high predictive power.

Except for Rossell et al. (2013), each of the Bayesian methods described above impose local prior densities on regression coefficients in the true model. That is, the prior density on the regression coefficients has a positive prior density function at 0 (and in most cases has its mode at 0), which from a Bayesian perspective makes it more difficult to distinguish between models that include regression coefficients that are close to 0 and those that do not. Johnson and Rossell (2012) proposed two new classes of non-local prior densities to ameliorate this problem. In the model selection context, non-local prior densities are 0 when a regression coefficient in the model is 0. This makes it easier to distinguish between coefficients that do not have an impact on the prediction of y from those that do. Johnson and Rossell (2012) used a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm to sample from the posterior distribution on the model space; the convergence properties of this algorithm were studied in Johnson (2013).

The primary goal of this article is to extend the methodology proposed in Johnson and Rossell (2012) for application to binary outcomes and to compare the performance of this algorithm to leading penalized likelihood methods. In addition, we describe a default procedure for setting the hyperparameters (i.e. tuning parameters) in the non-local priors, and we examine a numerical strategy for identifying the highest posterior probability model (HPPM).

2 Methods

Let denote a vector of independent binary observations, an n × p matrix of real numbers, a regression vector, and the ith row of . We denote a model by where and it is assumed that and all other elements of are 0. The design matrix corresponding to model is denoted by and is defined to have cardinality k. We assume that the columns of X have been standardized. The ith row of is denoted by . Assuming the logistic link function for F in (1), the goal of the model selection procedure proposed in this article is to identify sparse regression models that have high predictive probability. We propose to do this by identifying the highest posterior probability model for data , distributed according to

| (2) |

under prior constraints on the model space and the assumption of non-local prior density constraints on the regression parameter . Our primary focus is on the case .

Bayesian model selection is based on the calculation of posterior model probabilities. From Bayes theorem, the posterior probability of model is specified as

| (3) |

where

| (4) |

The art in implementing a Bayesian model selection procedure thus focuses on specifying the prior densities for under each model, as well as the prior model probabilities for the models themselves. Except for the intercept, we assume non-local priors on the components of the regression vector in each model. These non-local priors are described in the next section. Discussion of the prior on the model space is described after that.

2.1 Non-local priors

The form of the non-local prior densities imposed on the (non-zero) regression coefficients in this article take the form of a product of independent iMOM priors, or piMOM densities, expressible as

| (5) |

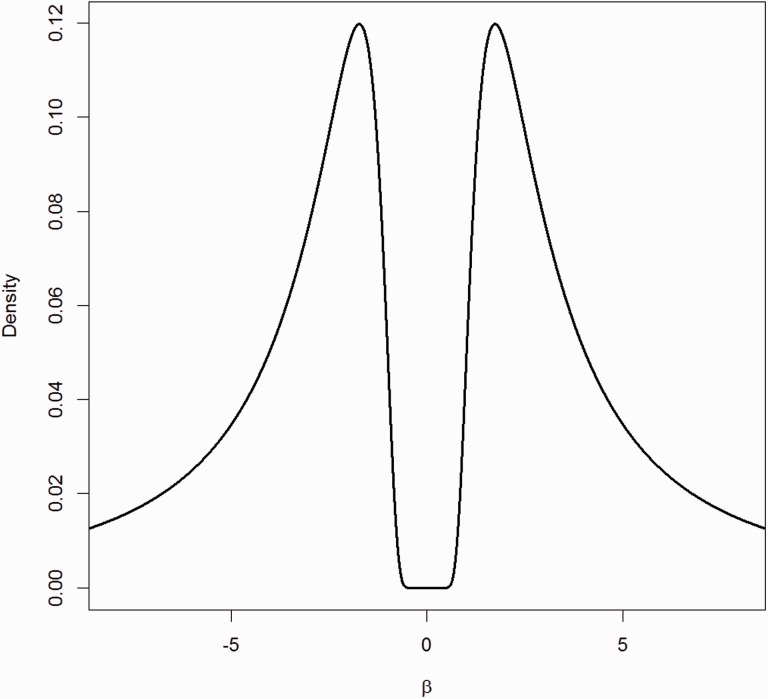

Here is a vector of coefficients of length k, and . The hyperparameter τ represents a scale parameter that determines the dispersion of the prior around , while r is similar to the shape parameter in the Inverse Gamma distribution and determines the tail behavior of the density. An example of an iMOM density is illustrated in Figure 1 for the particular case of r = 1 and τ = 3.

Fig. 1.

iMOM prior for r = 1 and τ = 3

An important feature of this non-local prior, as highlighted in Johnson and Rossell (2012), is that these priors do not necessarily impose significant penalties on non-sparse models, provided that the estimated coefficients in the non-sparse models are not too small. That is, large values of regression coefficients are not penalized since the value of the exponential kernel in (5) tends to 1 as βi becomes large. This fact lies in stark contrast to most penalized likelihood methods.

2.2 Prior on model space

To define the prior on the model space, we adopt a subjective version of the prior proposed by Scott et al. (2010). In the fully Bayesian version of the beta-binomial prior, this formulation specifies that the prior probability for model is

| (6) |

where B(a, b) denotes the beta function and a and b are prior parameters that describe an underlying beta distribution on the marginal probability that a selected feature is associated with a non-zero regression coefficient in (2). This type of prior on the model size is also recommended in Castillo et al. (2015), where it is suggested that an exponential decrease in prior probabilities with model size provides optimal results when the prior density on regression parameters has the form of a double exponential.

To incorporate our belief that the optimal predictive models are sparse, we arbitrarily set , and . For large n, this implies that we expect, on average, a feature vectors to be included in the model. Here, . This choice of for the prior hyperparameter reflects the belief that the number of models that can be constructed from available covariates should be smaller than the number of possible binary responses. Similarly, by restricting a to be less than , comparatively small prior probabilities are assigned to models that contain more than covariates. Finally, we impose a deterministic constraint on model size and define if .

A sensitivity analysis for a and b in (6) is provided in Section 4.1.1.

2.2.1 Choosing hyperparameters

A critical aspect of implementing our model is the choice of the hyperparameters r and τ. The value of r determines the tail behavior of the piMOM prior, while τ plays a role similar to the tuning parameter in penalized likelihood methods, with its value largely determining the minimum value of a component of that will be selected into a high posterior probability model.

To pick an appropriate, application-specific value for τ, we adopt a strategy in which we compare the null distribution of the maximum likelihood estimator for (i.e., when all components of are 0), obtained from a randomly selected design matrix , to the prior density on under the alternative assumption that the components are non-zero. By choosing τ to be just large enough so that the intersection of these two densities falls below a specified threshold, we are able to approximately bound the probability of false positives in the model, while at the same time maintaining sensitivity to regression coefficients that fall outside of the distribution of MLEs that estimate 0. In principle, we could employ this strategy to obtain a distinct value of τ for each model k, but were unable to do so in this article because of the computational expense this procedure would impose. Instead, we mixed over models to obtain a single value of τ.

Numerically, our strategy is implemented as follows. We begin by sampling a model from the prior on the model space. That is, we randomly sample k columns of X where k is determined by a draw from the prior on the model space. A Bernoulli vector of length n with success probability is generated, where is the proportion of successes in the observed data. Then the MLE for the model is estimated using standard logistic regression software with an intercept included in the model. This process is repeated N times to obtain a normal density approximation to the marginal density of maximum likelihood estimates under the condition that all true regression coefficients (except for the intercept) are 0. Typically, .

Next, piMOM priors corresponding to different values of τ are compared to the null distribution of the MLE. Based on these comparisons, we numerically determine the value of τ so that the overlap of these densities falls below a threshold of . This overlap value is chosen heuristically in a way that suggests the number of false positives will decrease to 0 as p and n become large. Other thresholds of the form might also be considered, but we have found that provides good performance in a wide range of simulation studies and in real data examples. Further justification for this threshold is provided in the supplementary data.

Notice that for a fixed p, the dispersion of the null distribution of the MLE around 0 decreases as the sample size n increases, although the rate of decrease is also affected by the structure of the design matrix X. This effect is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected τ parameter of piMOM prior for different simulation settings

| n = 50 | n = 100 | n = 200 | n = 400 | n = 600 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P = 1000 | 5.50 | 1.66 | 0.68 | 0.30 | 0.20 |

| P = 10 000 | 4.28 | 1.85 | 0.76 | 0.34 | 0.21 |

We also note that a similar procedure for setting the scale parameter for local priors on the regression coefficients could potentially be implemented. Unfortunately, the application of this procedure to local priors can require extremely large values of tuning parameters in order to ‘squash’ the prior near 0 and achieve small overlap with the null distribution. As a consequence of this fact, the tuning parameters selected by this procedure will not reflect any reasonable prior belief on the values of the regression parameters in a logistic model with a standardized design matrix.

To find an appropriate value of r for the piMOM prior (5), we impose a constraint that the prior mass assigned to the interval (−10,10) equals 0.95. This constraint is imposed because coefficients larger than 10 in magnitude are not expected when the columns of the design matrix have been standardized.

Together, these constraints identify a unique combination of r and τ for the piMOM prior.

A numerical strategy for finding this hyperparameter vector is outlined in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1 Choosing Appropriate r and τ for piMOM

1: Procedure rtauselect ()

2:

3: for (i in 1:N) do

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12: return

Notice that this procedure for choosing the hyperparameters depends on the prior on the model space. This implies that τ will tend to be larger in larger models, because it is more likely that the sampled columns X will exhibit high collinearity in large models. Ideally, we would adjust τ for each individual model, but as mentioned earlier it was not computationally feasible to do so for the applications and simulations reported in this article.

3 Numerical aspects of implementation

The model described in Section 2 leads to a joint density for the data, model and its parameters. As a result, the posterior distribution of model and its coefficients can be expressed as

| (7) |

Because of the high dimension of the parameter space and the complexity of the posterior density function in (7), it is not feasible to maximize this function analytically to obtain the HPPM. To search for the HPPM, we therefore utilized a Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm. To reduce the dimension of the parameter space, we used a Laplace approximation to marginalize over the regression coefficient associated with each model. The resulting approximation to the marginal posterior density of the data y under model can be expressed as

| (8) |

Here is the MAP estimate of and is the determinant of the Hessian of the function , computed at . The elements of the Hessian matrix can be expressed as

| (9) |

A simple birth-death scheme was used to sample from the posterior distribution. At each iteration of MCMC algorithm, each of the p covariates was visited in random order. The update at position i was performed by proposing a candidate model by flipping the inclusion state of that variable in the model. The candidate model was accepted using a Metropolis algorithm where the probability of accepting the candidate model, , was

| (10) |

The MAP estimate for was obtained using the nlminb() function in R. We assumed that an intercept was present in all models.

3.1 Convergence diagnostics

Convergence diagnostics of MCMC can be used to assess whether an adequate number of iterations have been performed. Because of the high dimension of the parameter space for even moderately large p, we implemented a modified coupling diagnostic (Johnson, 1996, 1998) to assess the probability that our MCMC algorithm had identified the true model. In the standard implementation of this method, one randomly initializes two MCMC chains by independently including each variable in the model according to a fixed probability. The components of the model in each chain are then updated synchronously, using the same uniform random deviate to perform acceptance/rejection of the candidate models. The chains are said to couple when the models from each chain are identical. Note that once the chains become coupled, they never uncouple. In theory, the distribution of the number of updates of the chains required to obtain coupling can be used to establish a bound on the total variation distance (TVD) between iterates in the chain and the target distribution.

In our implementation of the coupling diagnostic, we started 100 pairs of model chains. Each pair was updated until either they had coupled or all p components in each of the chains had been updated N times where N = 250. The (local) HPPM identified by each chain was recorded, and then the HPPM’s for the 100 chains were compared. We then identified the global HPPM among the 100 models in the paired chains, and also examined the proportion of chains that had both coupled and identified the ‘global’ HPPM.

4 Results

To investigate the performance of the proposed model selection procedure, we applied our procedure to both simulated data sets and real data. We compared the performance of our algorithm to ISIS-SCAD (Fan and Lv, 2008) in both real and simulated data because ISIS-SCAD has proven to be among the most successful model selection procedures used in practice. For the real data analyses, we also compared our method to another Bayesian procedure based on the product moment prior (Rossell et al., 2013).

4.1 Simulation studies

In all simulation studies, we assumed that the response vector represents a sequence of Bernoulli samples whose component probabilities of success are given by

| (11) |

for a true model k.

Elements of the design matrix X were sampled from a multivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and covariance matrix Σ, where the diagonal elements of Σ were 1 and off diagonal elements were 0.5. That is,

| (12) |

Different combinations of n and p were investigated. Moreover, different ranges of regression coefficients were tested. In our simulations, the true model contained three variables. The following combinations of n, p and were used to perform the simulation studies.

, where the non-zero coefficients of the vector were the ith row of the matrix .

The hyperparameters τ and r for the piMOM prior were selected by the procedure explained in Section 2.2.1 for each of the 10 combinations of n and p. Values of τ and r selected by this procedure are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 2.

Selected r parameter of piMOM prior for different simulation settings

| n = 50 | n = 100 | n = 200 | n = 400 | n = 600 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P = 1000 | 2.04 | 1.50 | 1.24 | 1.07 | 1.00 |

| P = 10 000 | 1.90 | 1.54 | 1.27 | 1.09 | 1.01 |

To run ISIS-SCAD, we used the R package ‘SIS’ (Fan et al., 2015) available from CRAN.

The variable selection procedure in both algorithms was run 50 times for each of the 30 combinations of n, p and . In each trial, true and false positive values for iMOMLogit and ISIS-SCAD were counted by comparing the selected model with the true one. TP and FP rates were defined as the average true and false positive values over 50 trials. A true positive, TP, was defined to be the number of variables that were correctly selected, while false positives, FP, were the number of variables that were mistakenly selected.

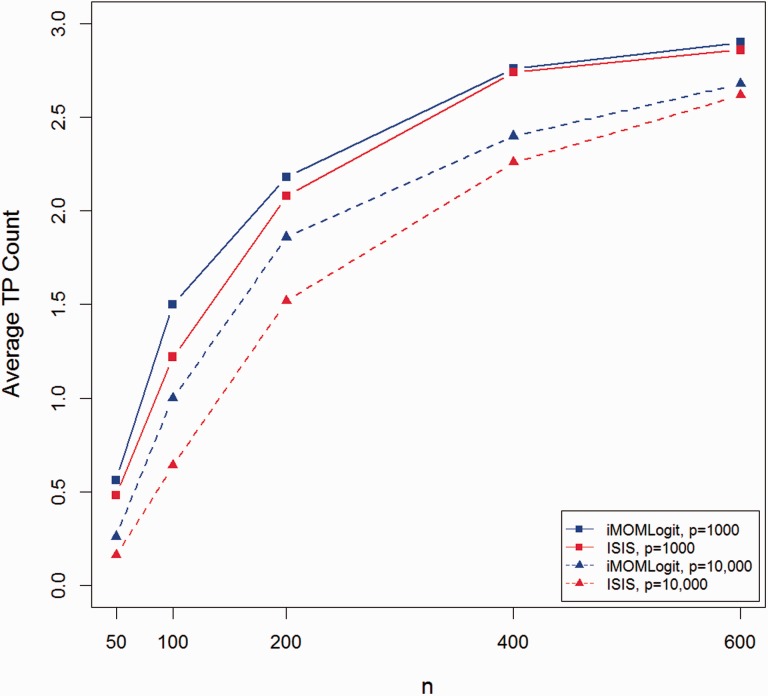

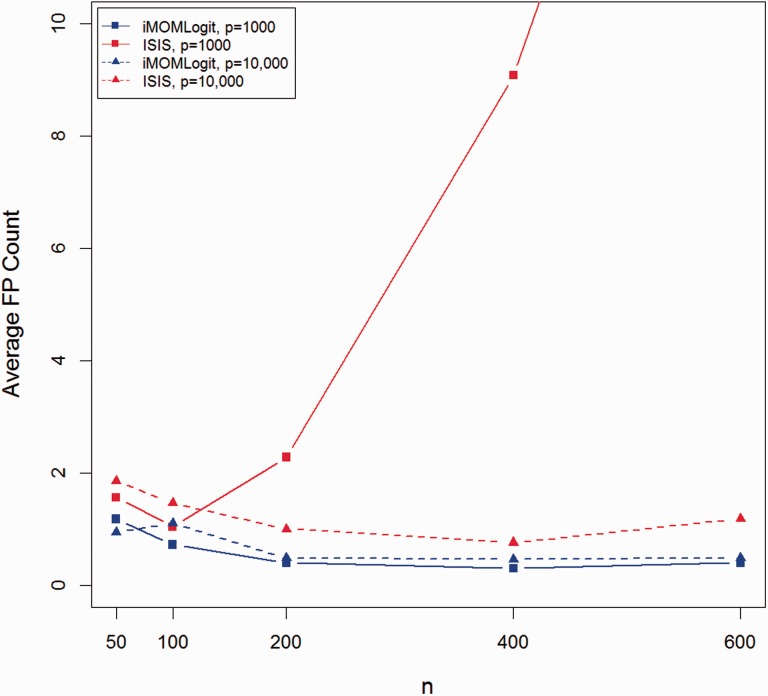

Figures 2 and 3 show average TP and FP counts of both methods for all combinations of n and p and . The figures for and are provided in the supplementary materials and demonstrate similar trends. In all cases, the average FP count for iMOMLogit was less than ISIS-SCAD, while its average TP count was higher. The only case where both iMOMLogit and ISIS-SCAD had the same average TP count was when they both found the true model in all 50 simulation trials.

Fig. 2.

Average true positive count for

Fig. 3.

Average false positive count for

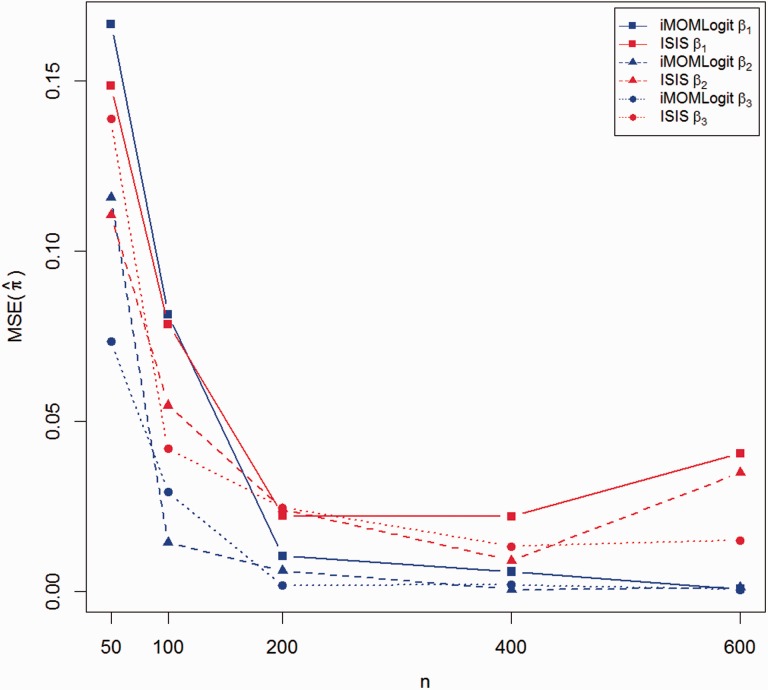

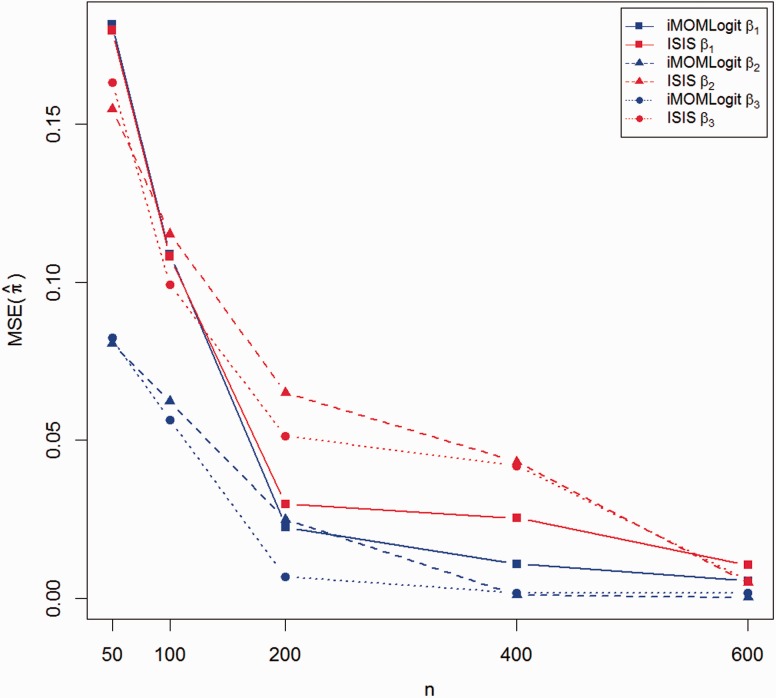

We next compared the performance of both methods in estimating the regression coefficients. For each simulation setting, we compared the mean squared error in estimating the probability of success for each binary observation by performing 10-fold cross validation. The point estimate was estimated as the posterior mode under the HPPM. The predicted value of was then computed according to (1). Note that the prediction of the response vector involves both coefficient estimation and variable selection. The mean squared error of prediction (MSE) was defined as follows:

| (13) |

The comparison between cross validated MSEs of both methods is shown in Figures 4 and 5. As in the comparisons of TP and FP rates, these figures suggest that iMOMLogit is preferred to ISIS-SCAD in estimating the success probabilities of binary observations.

Fig. 4.

10-fold cross validation MSE of iMOMLogit vs. ISIS-SCAD, P = 1000

Fig. 5.

10-fold cross validation MSE of iMOMLogit vs. ISIS-SCAD, P= 10 000

4.1.1 Sensitivity analysis for prior parameters on model space

To assess the sensitivity of our results to the prior hyperparameters on the model space (6), we conducted a brief sensitivity analysis under the simulation settings for which n = 200, p = 1000 and . We also fixed as before. This insured that the prior mean of the number of variables selected would be a. Based on the default procedure for defining a described in Section 2.2, the default value for a in this setting was 6. We examined sensitivity to this choice of a by varying a around this default value within the interval (3, 9). To quantitatively assess the sensitivity of the selection procedure to values of a in this range, we examined the consequent changes to described in (13). This measure incorporates errors in both variable selection and coefficient estimation.

The figure provided in the supplementary material depicts for different values of a in the described simulation setting. As shown in that figure, model output does not change dramatically with changes in a, varying by at most from the default choice of a.

4.2 Real data analysis

We applied iMOMLogit to two data sets, one with a small sample size and one with a large sample size. These two data sets are publicly available and have good clinical annotations. The first data set was the Golub leukemia data (Golub et al., 1999). The goal of our analysis for these data was to discriminate between two types of acute leukemia, myeloid (AML) and lymphoblastic (ALL). The design matrix consisted of gene expression levels produced by cDNA microarrays from bone marrow samples, and was pre-processed by RMA (Irizarry et al., 2003). There are 72 samples and 7,129 genes in the data set. The second data set was the clear cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC) RNAseq data, available from the Cancer Genome Atlas projects (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, 2013) (TCGA). There were 467 tumor samples and more than 20 000 genes in this data set.

As mentioned earlier, we also compared our selection procedure results to a related Bayesian method proposed in Rossell et al. (2013), called pmomPM. This method uses a probit link function with a moment prior, (pMOM), another type of non-local prior. The pMOM prior has Gaussian tails and decreases quadratically near the origin. We implemented this method with the default hyperparameter suggested in Rossell et al. (2013) for sparse models. To run pmomPM method, we used the R package ’mombf’ (Rossell et al., 2015) available from CRAN.

In contrast to iMOMLogit and ISIS-SCAD, the mombf package focuses on prediction using Bayesian model averaging, rather than on the identification of biologically important genes using the HPPM. Because of the behavior of the pMOM prior near the origin, the pMOM model selects many more genes in the models over which it averages. Though model averaging can improve prediction accuracy (Raftery et al., 1997), the current version of the mombf package does not provide estimates of the HPPM, which complicates comparisons with the other methods considered here. These attributes of the pmomPM method are illustrated in the examples that follow.

4.2.1 Leukemia data

Following Golub et al. (1999), we split the data into training and test sets. The training set contained 38 samples, with 27 ALL and 11 AML. The testing set contained 34 samples, with 20 ALL and 14 AML.

Table 3 summarizes the results of applying iMOMLogit, ISIS-SCAD and pmomPM to these data. The error rate for predicting the test data observations was 5.88% for iMOMLogit, which misclassified 2 out of 34 observations, samples 17 and 31. Both ISIS-SCAD and the method described in Golub et al. (1999) resulted in an error rate of 14.7%. ISIS-SCAD achieved this error rate by finding two significant genes, ‘Zyxin’ and ‘FAH’, whereas Golub et al. (1999) selected 50 genes. The pmomPM method achieved an error rate of 23.53% with an average model size of 11.08. None of the genes were assigned marginal posterior probability of 0.5 by the pmomPM method; the highest marginal posterior probability of any gene was 0.052, acheived by CD33.

Table 3.

Comparison between iMOMLogit and other methods for leukemia data set

| Method | Error rate | Reported genes |

|---|---|---|

| iMOMLogit | 5.88% | Zyxin |

| ISIS-SCAD | 14.70% | Zyxin - FAH |

| pmomPM | 23.53% | No genes had marginal posterior probability greater than 0.5 |

iMOMLogit selected a model containing only one gene named ‘Zyxin’, which perfectly predicted the classifications in the training data. This gene was also listed in the top 50 genes reported by Golub et al. (1999), and was found to be advantageous for classifying the two types of leukemia in four published data sets (Baker and Kramer, 2006). The gene ‘FAH’ found only by ISIS-SCAD is involved in certain metabolic pathways that are not known to be associated with leukemia (Kegg.org).

Following the methodology discussed in Section 3.1, 74% of pairs of chains that were updated using the coupling algorithm found the same highest posterior probability model (HPPM). Among all pairs, 95% coupled.

4.2.2 Renal cell carcinoma data

The second data set was generated by the Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2013) and contained Illumina HiSeq data on mRNA expression for 467 patient samples. The survival outcomes of these patients were available. A hierarchical clustering of the gene expression data [preprocessed using DeMix (Ahn et al., 2013) to remove stromal contamination] were performed on the data. That led to the identification of four clusters of patients based on survival times. To apply iMOMLogit, we considered two of those clusters, presenting the best and worst survival outcomes and labeled them as 0 (worst) and 1 (best). The resulting number of samples included in our analysis was 193, with 14150 features in the design matrix.

The results using iMOMLogit, ISIS-SCAD and pmomPM are summarized in Table 4. To compare methods, we performed a 10-fold cross-validation. The error rate of iMOMLogit was 9.79%, ISIS-SCAD’s error rate was 12.97%, and pmomPM was 9.84%. In the model selected by iMOMLogit, there were 3 significant genes named ‘C7orf43’, ‘NUMBL’ and ‘SAV1’, with the latter two being uniquely identified by our model. ‘NUMBL’ participates in the Notch signaling pathway and is believed to contribute to nervous system tumors (glioma) (Tao et al., 2012) as well as lung cancer (Yingjie et al., 2013). The Notch signaling pathway is highly conserved, manages communication between adjacent cells and maintenance of adult stem cells, and is linked to the development of various cancers (Alketbi and Attoub, 2015). Not surprisingly, we identified NUMBL as differentiating two groups of kidney patients. ‘SAV1’ has been reported to play a role in kidney cancer (Matsuura et al., 2011), and is located in a Hippo signaling pathway (Kegg.org). The Hippo signaling pathway is highly conserved and controls epithelial tissue growth. Recently, its relation to other signaling pathways has been studied to identify new therapeutic interventions for cancer (Yimlamai et al., 2015).

Table 4.

Comparison between iMOMLogit and other methods for renal cell carcinoma data set

| Method | Error rate | Reported genes |

|---|---|---|

| iMOMLogit | 9.79% | C7orf43 - NUMBL - SAV1 |

| ISIS-SCAD | 12.97% | C7orf43 - C19orf66 - ATXN7L2 - MICAL1 |

| pmomPM | 9.84% | No genes had marginal posterior probability greater than 0.5 |

Among all pairs of chains with different random starts, 32% of them reported the same global HPPM and 6% of paired chains were coupled. This suggests that convergence in this data set was more problematic, and that our multiple coupled chain approach (or other modifications of the standard, single chain MCMC algorithm) is required to identify the HPPM model.

The genes uniquely selected by ISIS-SCAD were ‘C19orf66’, ‘ATXN7L2’ and ‘MIICAL1’. ‘ATXN7L2’ was previously reported to be associated with non-small cell lung cancer (Wu et al., 2013), whereas ‘MICAL1’ was previously reported to control survival in melanoma cell lines.

As for the leukemia data, the pmomPM selected substantially more genes in each of its sampled models, and the genes selected in each model were highly variable. The average model size of the pmomPM method for this data set was 13.84. As before, none of the genes were assigned marginal probability of 0.5; the highest marginal posterior probability assigned to any gene was 0.33, for API5.

The genes identified by iMOMLogit seem to be more biologically meaningful and better annotated in the literature for ccRCC than those selected by ISIS-SCAD.

5 Discussion

In this article, we introduced a Bayesian method, iMOMLogit, for variable selection in binary response regression problems in high and ultrahigh-dimensional settings. There are many applications associated with these type of data. Such data are of great interest to bioinformaticians and biologists, who routinely collect gene expression data to find prognostic features to classify cancer types.

For two real datasets, iMOMLogit identified sparse models with low prediction error rates. In both cases, biological considerations suggest that the genes reported by iMOMLogit appear to be valid predictors of biological outcomes.

The primary disadvantage of the iMOMLogit procedure is that it is computationally much more intensive than ISIS-SCAD and related penalized likelihood methods. We are currently investigating methods for reducing the computational burden of our algorithm by implementing various screening procedures that are similar to those used in ISIS-SCAD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank John Hancock and three anonymous referees for their valuable comments that improved the presentation of the materials in this article. The authors would also like to thank Jaeil Ahn for providing the deconvolved RNAseq data for ccRCC samples as well as the two clusters of patients with most distinct survival outcomes.

Funding

National Institute of Health (R01CA158113 to A.N. and V.E.J.); National Cancer Institute (1R01CA174206-01 to A.N. and W.W., 1R01CA183793-01 and P30 CA016672 to W.W.); Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP130090 to W.W.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Ahn J. et al. (2013) Demix: deconvolution for mixed cancer transcriptomes using raw measured data. Bioinformatics, 29, 1865–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alketbi A., Attoub S. (2015) Notch signaling in cancer: Rationale and strategies for targeting. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets, 15, 364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.G., Kramer B.S. (2006) Identifying genes that contribute most to good classification in microarrays. BMC Bioinformatics, 7, 407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2013) Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature, 499, 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candes E., Tao T. (2007) The dantzig selector: Statistical estimation when p is much larger than n. Ann. Stat., 2313–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo I. et al. (2015) Bayesian linear regression with sparse priors. Ann. Statist., 43, 1986–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Li R. (2001) Variable selection via nonconcave penalized likelihood and its oracle properties. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 96, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Lv J. (2008) Sure independence screening for ultrahigh dimensional feature space. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B, 70, 849–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J. et al. (2015) SIS: Sure Independence Screening. R package version 0.7-6.

- George E.I., McCulloch R.E. (1997) Approaches for bayesian variable selection. Statistica Sinica, 7, 339–373. [Google Scholar]

- Golub T.R. et al. (1999) Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science, 286, 531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry R.A. et al. (2003) Summaries of affymetrix genechip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, e15–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V.E. (1996) Studying convergence of markov chain monte carlo algorithms using coupled sample paths. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 91, 154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V.E. (1998) A coupling-regeneration scheme for diagnosing convergence in markov chain monte carlo algorithms. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 93, 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V.E. (2013) On numerical aspects of bayesian model selection in high and ultrahigh-dimensional settings. Bayesian Anal., 8, 741–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson V.E., Rossell D. (2012) Bayesian model selection in high-dimensional settings. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 107, 649–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.E. et al. (2003) Gene selection: a bayesian variable selection approach. Bioinformatics, 19, 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F. et al. (2008) Mixtures of g priors for bayesian variable selection. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 103. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura K. et al. (2011) Downregulation of SAV1 plays a role in pathogenesis of high-grade clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer, 11, 523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery A.E. et al. (1997) Bayesian model averaging for linear regression models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 92, 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rossell D. et al. (2013). High-dimensional bayesian classifiers using non-local priors In: Statistical Models for Data Analysis, pp. 305–313. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rossell D. et al. (2015) mombf: Moment and Inverse Moment Bayes Factors. R package version 1.6.1.

- Scott J.G., Berger J.O. et al. (2010) Bayes and empirical-bayes multiplicity adjustment in the variable-selection problem. Ann. Stat., 38, 2587–2619. [Google Scholar]

- Tao T. et al. (2012) Numbl inhibits glioma cell migration and invasion by suppressing TRAF5-mediated NF-B activation. Mol. Biol. Cell, 23, 2635–2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R. (1996) Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B (Methodological), 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- West M. et al. (2000) Dna microarray data analysis and regression modeling for genetic expression profiling. ISDS Discussion. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. et al. (2013) Genome-wide association study of genetic predictors of overall survival for non-small cell lung cancer in never smokers. Cancer Res., 73, 4028–4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yimlamai D. et al. (2015) Emerging evidence on the role of the hippo/yap pathway in liver physiology and cancer. J. Hepatol., 63, 1491–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yingjie L. et al. (2013) Numblike regulates proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion of lung cancer cell. Tumour Biol., 34, 2773–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H. (2006) The adaptive lasso and its oracle properties. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 101, 1418–1429. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.