Abstract

Volume-regulated channels for anions (VRAC) / organic osmolytes (VSOAC) play essential roles in cell volume regulation and other cellular functions, e.g. proliferation, cell migration and apoptosis. LRRC8A, which belongs to the leucine rich-repeat containing protein family, was recently shown to be an essential component of both VRAC and VSOAC. Reduced VRAC and VSOAC activities are seen in drug resistant cancer cells. ANO1 is a calcium-activated chloride channel expressed on the plasma membrane of e.g., secretory epithelia. ANO1 is amplified and highly expressed in a large number of carcinomas. The gene, encoding for ANO1, maps to a region on chromosome 11 (11q13) that is frequently amplified in cancer cells. Knockdown of ANO1 impairs cell proliferation and cell migration in several cancer cells. Below we summarize the basic biophysical properties of VRAC, VSOAC and ANO1 and their most important cellular functions as well as their role in cancer and drug resistance.

Keywords: anoctamins, apoptotic volume decrease, LRRC8A, regulatory volume decrease, TMEM16A, VRAC, VSOAC

Abbreviations

- AE

Anion exchange

- ANO

Anoctamin

- AVD

Apoptotic volume decrease

- CaCC

Ca2+ dependent Cl- current

- CNS

Central nerve system

- DOG-1

Discovered on gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- EATC

Ehrlich ascites tumor cells

- EGTA

ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid

- ELA

Ehrlich Lettré ascites tumor cells

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- ERM

Ezrin-radixin-moesin

- FADD

Fas associated protein with death domain

- HEK

Human embryonic kidney cells

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HPDE

Human pancreatic ductal epithelium cells

- KD

Knockdown

- LRRC8

Leucine rich repeat containing

- MDR

Multidrug resistant

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NKCC

Na,K,2Cl cotransporter

- ORAOV2

Oral cancer overexpressed

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PI3K

Phosphatidyl inositol 3-phosphate kinase

- RVD

Regulatory volume decrease

- TAOS2

Tumor amplified and overexpresses sequence

- VRAC

Volume regulated anion channel

- VSOAC

Volume sensitive organic anion channel

- WT

Wild type.

Introduction

Movement of anions across the plasma membrane is essential for cellular homeostasis and many physiological functions. Volume sensitive and Ca2+ activated Cl- channels are well-characterized and recently cloned.1-5 In the following we describe structure and function of VRAC, VSOAC and ANO1 with emphasis on their role in essential physiological functions (proliferation, migration, apoptosis) and their role in cancer (cell viability, metastasis, drug resistance).

Volume-Regulated Anion Channel – VRAC

Although osmolarity of the extracellular fluid in the body is well controlled,6 many cells are still challenged by change in extra- or intracellular electrolytes and water (see e.g.7). Hence, the ability to regulate cell volume is essential for maintenance of most cellular processes. Important examples of a challenge to cell volume is solute and water flow through epithelia,8 and volume perturbation, resulting from neuronal activity in CNS.9

Conversely, to the ability to regulate cell volume following changes in the intracellular or extracellular osmolarity, cell volume changes act as signals that control cell proliferation, migration and programmed cell death.7 The osmotic permeability to water is 105 to 106 times higher compared to the cation (Na+/K+) and anion (Cl-) permeabilities,10,11 thus an increase in the intracellular osmolarity or a reduction in the extracellular tonicity elicit a rapid increase in cell volume. Cell swelling is followed by a restoration of the cell volume through a process termed regulatory volume decrease (RVD). RVD reflects increase in the permeability to the dominant cellular cation K+, the anion Cl- and amino acids.7,12,13 That cell swelling transiently activates electrogenic anion permeability was first described in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells (EATC)10 and in lymphocytes.14 Figure 1A illustrates Cl- efflux under isotonic, hypotonic and hypertonic conditions, and it has been determined that under isotonic conditions less than 5% represents conductive Cl- flux with the rest being electroneutral anion exchange (AE).15 In contrast, increased Cl- flux under swollen and shrunken conditions represent Cl- conductance (VRAC) and electroneutral Cl- transport via the Na,K,2Cl cotransporter (NKCC), respectively.10 Figure 1B shows the volume regulatory response in EATC under hypotonic conditions, where the intrinsic volume sensitive K+ channel has been blocked by quinine but a high K+ conductance has been ensured by addition of the cation-ionophore gramicidin, hence making Cl- movement rate limiting for volume changes. Here it is seen that the Cl- permeability increases dramatically following hypotonic exposure (seen as an accelerated RVD response) but decreases within 10 minutes.

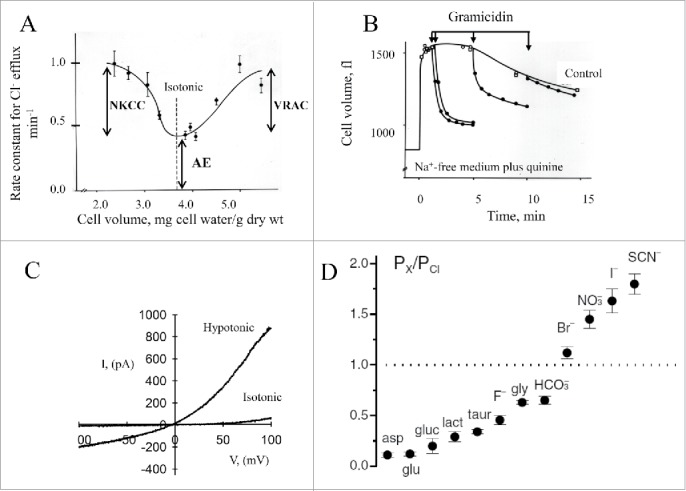

Figure 1.

VRAC characteristics. (A) Volume dependence of the rate constant for 36Cl efflux at steady state in EATC. Under isotonic conditions 95% of the Cl- efflux is mediated by an electroneutral anion exchange (AE). Under hypotonic conditions an increasing part of the Cl- efflux constitutes conductive Cl- flux taken to represent VRAC activity. Under hypertonic conditions an increasing part of the Cl- efflux constitutes cation dependent electroneutral Na, K, 2Cl cotransporter (NKCC). Values from15,158 and Figure adapted from7. (B) Transient increase in the Cl- permeability following hypoosmotic cell swelling. EATC cells were at time zero exposed to hypotonic, Na+-free medium containing quinine to block intrinsic, volume sensitive K+ channels. Gramicidin was added as indicated by the arrow to ensure high cation permeability, i.e., to establish conditions where the rate of RVD is dictated by the Cl- permeability. Figure modified from159. (C) Current / voltage (I-V) relationship for VRAC in EATC. Cl- current under isotonic and hypotonic (27% decrease) conditions was obtained from whole cell patch clamp recordings (−140 mV to +80 mV, fast ramp-protocol). Figure modified from41. (D) VRAC permeation properties. VRAC permeabilities to organic substrates [aspartate (asp), glutamate (glu), gluconate (gluc), lactate (lact), taurine (taur), glycine (gly)] and anions are given relative to the Cl- permeability. Figure 1D © John Wiley and Sons. Reproduced by permission of John Wiley and Sons. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

Biophysical characterization of VRAC

These early studies were later followed by patch clamp experiments16,17 that revealed the presence of an outwardly rectifying anion current, which was activated by cell swelling in most cell types.18 Figure 1C illustrates the volume-sensitive, outwardly rectifying anion current in EATC. Figure 1D illustrates that VRAC shows a type I Eisenman permeability sequence (I- >Br- > Cl-) and low permeability to amino acids. Figure 2A illustrates that VRAC shows voltage-dependent deactivation at positive (> 40 mV) potentials, which is seen in many cell types.7,18-20

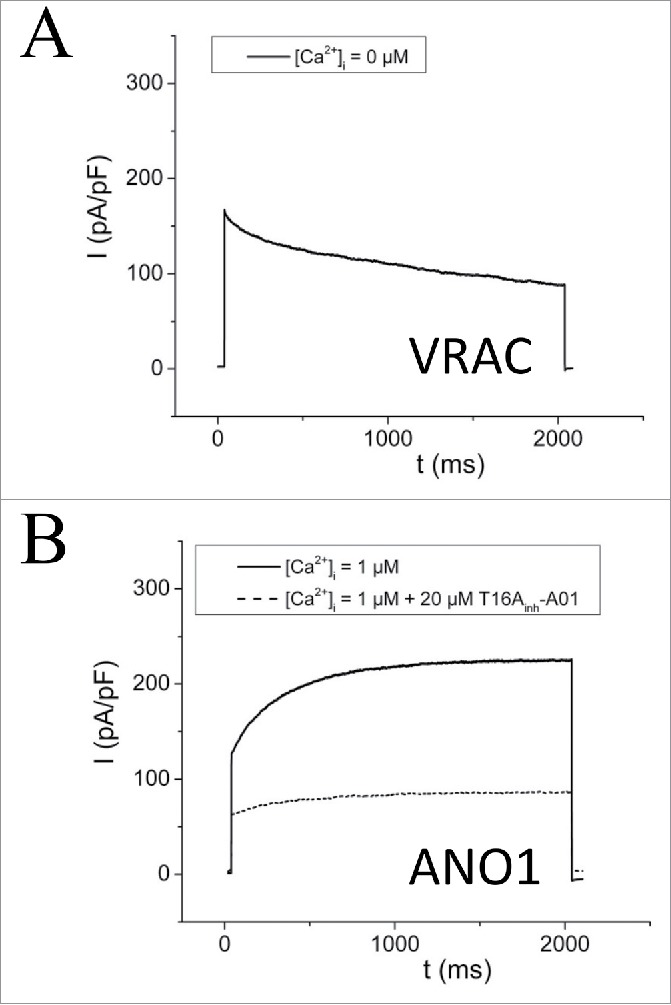

Figure 2.

VRAC and ANO1. Representative current traces over time of Capan-1 (pancreatic cancer cell line) cells at Vm = + 65 mV. (A) Cells, in the absence of intracellular Ca2+, were exposed to a hypotonic solution (210 mOsm). This swelling-activated current showed deactivation at positive potentials as described for VRAC. Shown trace was recorded after full saturation of swelling-activated current. (B) In the presence of 1µM free Ca2+ in pipette solution, a voltage- and time-dependent activated current was detected. This current was sensitive to the ANO1 - inhibitor T16Ainh-A01 (punctuated line). Figure adapted from.120

Activation and modulation of VRAC activity

A decrease in the intracellular ionic strength due to cellular hydration is the main signal for VRAC activation.21,22 Furthermore, VRAC is also activated under isotonic conditions by an increase in the intracellular concentration of GTP-γ-S, presumably by a mechanism that involves the small G-protein RhoA and F-actin polymerization.23,24 In agreement with this, VRAC is in several cell types demonstrated to be Rho and Rho-kinase regulated.23-25 Activation of VRAC following a modest hypoosmotic challenge is potentiated following cholesterol depletion (Fig. 9D)26 apparently due to an increased open probability of the channel.27 It has been suggested that this effect reflects prevention of a hypotonicity-induced reduction in the Rho activity and hence promotion of F-actin polymerization.26 It is noted that membrane stretch per se does not activate VRAC.20,28 In addition, signaling pathways contributing to VRAC activity include phosphatidyl-inositol-3-phosphate kinase (PI3K), NADH-dependent oxidases and reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as tyrosine kinases.29-36 Recently it was demonstrated that knockdown of integrin β1 reduces RVD in adherent Ehrlich Lettré ascites cells (ELA) cells37 and as integrin β1 stretch in cardiac ventricular myocytes is shown to regulate VRAC,38 it is likely that inhibition of RVD by integrin β1 knockdown in ELA cells involves inhibition of VRAC. VRAC current can in most cell types be activated under conditions with strongly buffered intracellular Ca2+.39-42 Finally, intracellular ATP seems to be required for VRAC activation.22,43,44 For further discussion of VRAC activation and modulation see.7,9,19

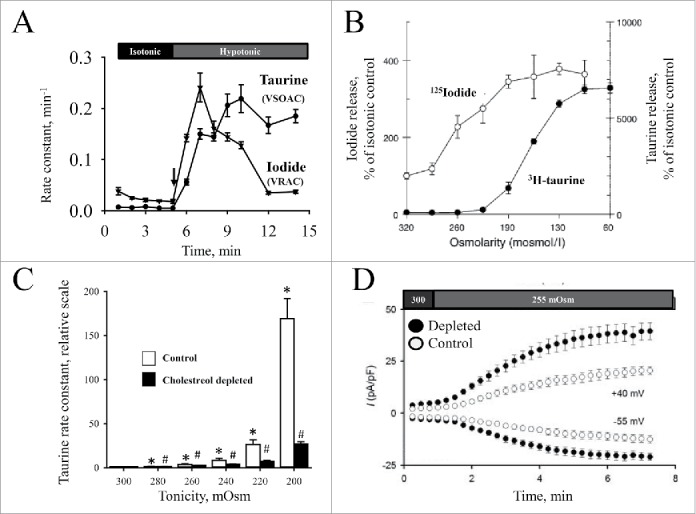

Figure 9.

Comparison of VSOAC and VRAC properties (A) The fractional rate constant for release of 3H-labeled taurine (tracer for VSOAC activity) and 125I- (tracer for VRAC activity) from HeLa cells, preloaded with the isotope, was followed with time under isotonic and hypotonic conditions (shift in tonicity indicated by the arrow). Data from160 and Figure adapted from88. (B) Release of 3H-labeled taurine and 125I- (tracer for VRAC activity) from human intestinal epithelial cells following exposure to reduced tonicity. Values are given as increase in osmolyte release (peak value) relative to isotonic control. Figure adapted from161. (C) Effect of cholesterol depletion on taurine release under hypotonic conditions in ELA. Cells loaded with 3H-labeled taurine in serum-free medium in the absence (control) or presence of 5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrine (cholesterol depleted cells) were exposed to isotonic (300 mOsm) or hypotonic (range: 280…200 mOsm) and the release followed with time. Release of taurine increases transiently following hypoosmotic exposure (see e.g. Fig. 10C) and the rate constants (min-1) were determined as mean rate constants for taurine release under isotonic conditions (300 mOsm) and max rate constants obtained under hypotonic conditions. Values for the maximal rate constant obtained under hypotonic conditions are given relative to the respective isotonic value in control and depleted cells. Figure adapted from.162 (D) Effect of cholesterol depletion on VRAC current under hypotonic conditions in ELA cells. Cells were cholesterol-depleted as indicated under 9C and VRAC current followed with time by patch clamp (whole cell recording / −55 and +40 mV) under isotonic (300 mOsm) and hypotonic (255 mOsm) conditions as indicated by the bars. Figure adapted from.26

VRAC versus anoctamins

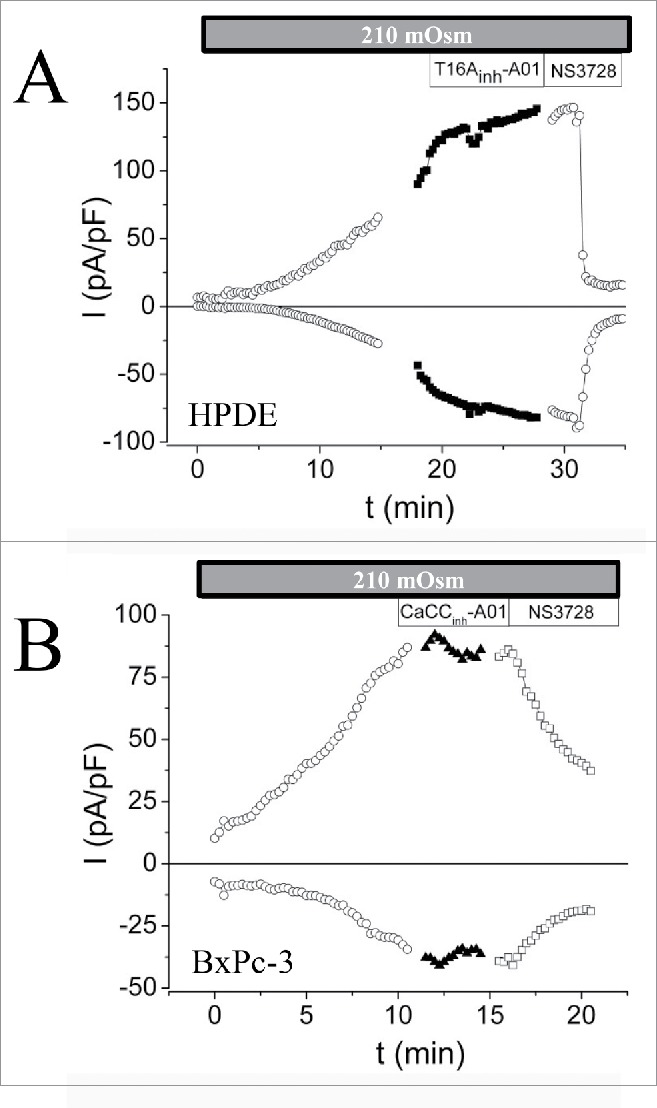

The Ca2+- activated channels ANO1 and ANO6 have been discussed as VRAC candidates.45 They show outward-rectification and a similar permeability sequence as described for VRAC (SCN->I->NO3->Br->Cl->gluconate), they are activated by osmotic cell swelling in the presence of extracellular Ca2+40 and requires cellular ATP.22,43,44,46 However, VRAC and ANO1/6 activities can be distinguished by (i) their sensitivity to strongly buffered intracellular Ca2+, i.e. VRAC can be activated whereas ANO1 cannot, (ii) activation/deactivation at positive potentials, i.e., VRAC deactivates9,41,47 whereas ANO1/6 activates (Fig. 2A–B), and (iii) their pharmacological profile, i.e. several compounds inhibit VRAC18 with acidic di-aryl-urea (NS3728) (Fig. 3A–B)48 and 4-(2-butyl-6,7-dichlor-2-cyclopentyl-indan-1-on-5-yl)-oxybutyric acid (DCPIB)49 being among the more effective, whereas the ANO1 inhibitors T16Ainh-A0150(Fig. 2A) and CaCCinh-A0151 have no effect on VRAC (Fig. 3A–B). With respect to channel biophysics VRAC has a unitary conductance of 10–20 pS for inward currents and 40–80pS for outward currents.52,53 Native CaCC in rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes exhibit 2 conductance states with 1.8 and 3.5 pS when examined in a single-channel patch-clamp experiment.54 ANO1 unitary conductance is measured at 8.3 pS from the slope conductance5 and at 3.5 pS from noise analysis.55

Figure 3.

VRAC activity in human pancreatic ductal epithelium (HPDE) and a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell line (BxPC-3). Current densities over time at Vm= −47 mV and + 93 mV in absence of intercellular Ca2+ and exposed to hypotonic medium (210 mOsm). ANO1 inhibitors (T16Ainh-A01; CaCCinh-A01) were applied at the time where maximum volume-activated current was obtained. VRAC inhibitor (NS3728) was applied to verify that current represented VRAC current. Figure adapted from.120

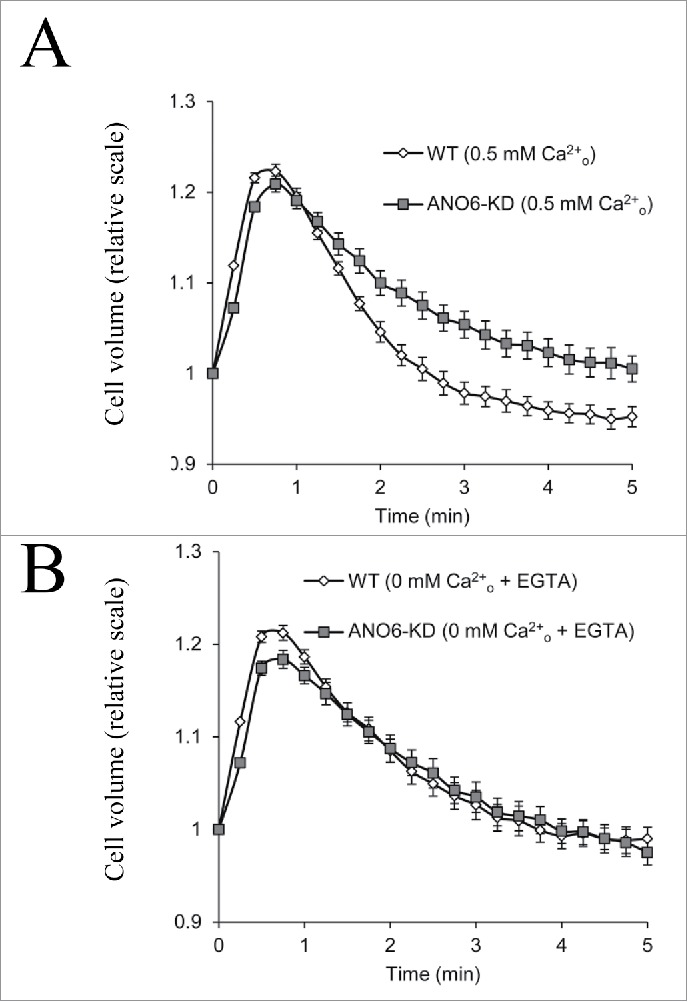

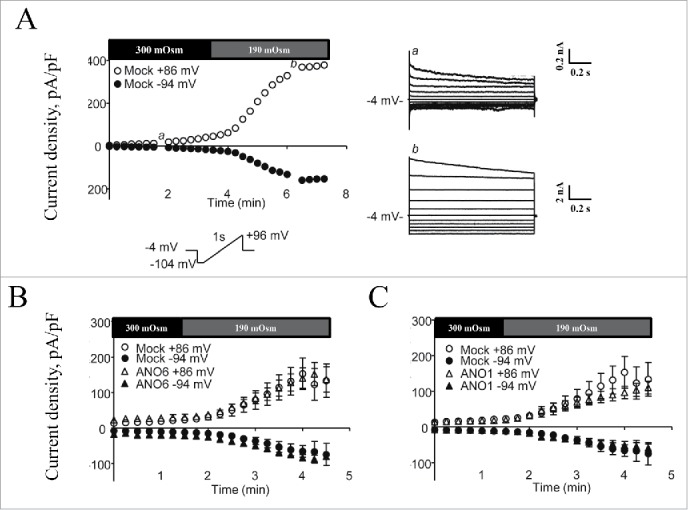

In 2009, Almaça and coworkers found that anoctamin knock-down significantly reduced the swelling-activated Cl- current and the concommitant RVD in the presence of extracellular Ca2+.45 To evaluate the contribution of anoctamins to the RVD response in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+, WT EATC and ANO6-KD EATC (KD Clone: miR-ANO6-1) were exposed to a hypotonic solution and RVD response was followed by electronic cell sizing. In the presence of 0.5 mM extracellular Ca2+ ANO6 KD reduced the rate of RVD (Fig. 4A), whereas the RVD rate didn´t change in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 4B). Hence, loss of Cl- via ANO6 contributes to the RVD response in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. Moreover, neither ANO1 nor ANO6 (Fig. 5) contributed to the volume-activated current in ANO-overexpressing HEK293 cells in the absence of Ca2+.40

Figure 4.

Cell volume regulation in WT and ANO6-KD EATC in the absence or presence of extracellular Ca2+. Cell volume for WT and ANO6-KD EATC was determined by electronic cell sizing (Coulter Counter) under isotonic conditions and after transfer to hypotonic medium (time zero) in the presence of 0.5 mM Ca2+ (A) or absence of extracellular Ca2+ (medium supplemented with 1 mM EGTA)(B). Values are given relative to the initial cell volume. Figure adapted from.40

Figure 5.

Volume-sensitive Cl- currents in mANO1 and mANO6 transfected HEK293 cells. Patch-clamp recordings in the whole cell configuration in the absence of intracellular Ca2+ (10 mM EGTA). (A) Mock-transfected HEK293 cells were exposed to isotonic and hypotonic superfusate (indicated by bars) and the volume activation (left) and voltage dependency (right) of the endogenous VRAC current in a single cell was followed with time. (B) Mean values for development of Cl- current in HEK cells transfected with mock or mANO6. (C) Mean values for development of Cl- current in HEK cells transfected with mock or mANO1. Figure adapted from.40

Role of VRAC in proliferation, migration and apoptosis – Role in multidrug resistance

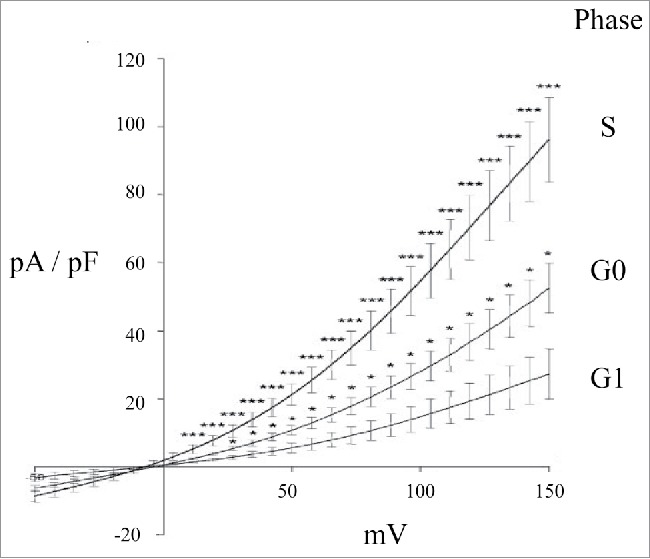

VRAC in Cell cycle progression

The role of specific cell volume changes for cell cycle progression is well described in glia cells.56-59 In several cell types it is found that VRAC is regulated throughout the cell cycle and that VRAC inhibitors obstruct cell proliferation.60-62 In particular, changes in VRAC activity seem important for the G1/S transition phase and many cells are halted in the G1 phase by Cl- channel inhibitors.63-69 It should be noted that conclusions about VRAC and cell cycle generally rely on data obtained with pharmacological compounds with low selectivity / specificity and should be reinvestigated now that essential components of VRAC have been cloned.2,4 In ELA cells patch clamp experiments revealed that VRAC activity decreased as ELA cells go from G0 to G1, and increased again when they go from G1 to S66 (Fig. 6). Thus, if ELA cells in G0 decrease their VRAC activity they will progress into G1 and avoid apoptosis (see discussion later). A decreased VRAC activity, as seen in many multidrug resistant cells (see below), is thus favoring cell cycle progression and preventing apoptosis.70

Figure 6.

I/V relationships of the Cl- current in ELA cells in G0, G1, or (S)phase, following exposure to hypotonic extracellular solution and at nominally Ca2+ free concentration. Cl- current data were obtained by whole-cell patch-clamp measurements (Vhold was 0 mV; voltage ramps from -0 to +150 mV of 2.6 sec duration were applied every 15 sec, after a 500 msec pre-pulse to +30 mV). Figure adapted from.66

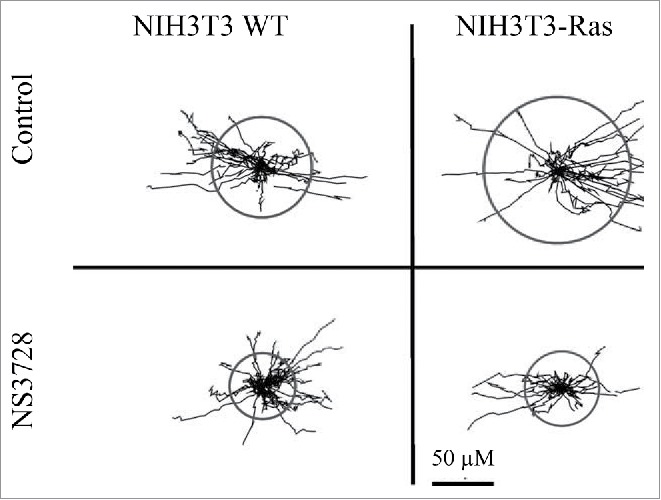

VRAC in Cell migration

VRAC inhibitors inhibit cell migration in several cell types (Fig. 7)71,72 and the Schwab group has presented a model, where cell migration involves shrinkage-activated transporters at the leading end and K+, Cl- channels at the lagging end. Cell expansion / protrusion at the leading end is according to the model obtained by uptake of ions, whereas retraction at the lagging end is obtained by ion loss and cell shrinkage (see73). However, as indicated above for cell cycle studies, conclusions on migration are also based on inadequate and questionable pharmacological compounds.

Figure 7.

NIH3T3 migration - trajectories. Single cell migration during a 5-h time period was monitored for NIH3T3 fibroblasts (left) and H-Ras-transformed NIH3T3 (right) mouse fibroblasts in the absence (top panels) and presence (bottom panels) of the anion channel blocker NS3728 (400 nmol/l). Figure adapted from.72

VRAC in apoptosis and in multidrug resistance

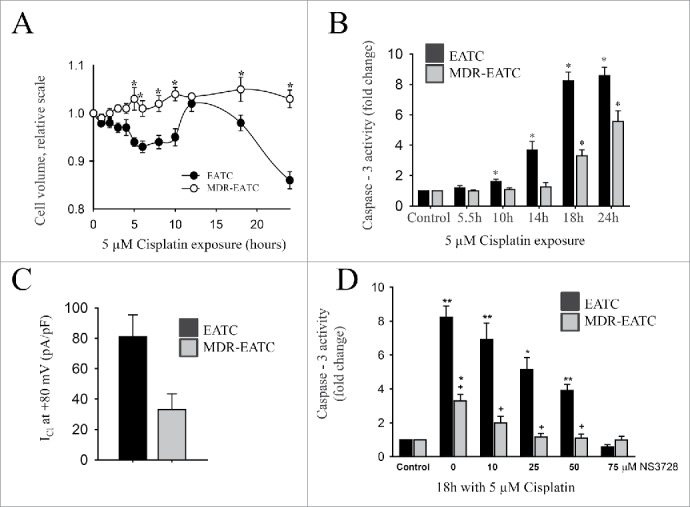

Activation of VRAC under isovolumetric conditions results in cell shrinkage and has been shown to be involved in the early phase of apoptosis in several cell types.74-77 This initial cell shrinkage, which reflects net loss of KCl and amino acids, is termed apoptotic volume decrease (AVD)75 and is essential to initiation of the apoptotic process.78 Hence, inhibition of VRAC blocks AVD and cell death.74,75,78,79 Activation of VRAC by apoptotic stimuli under isovolumetric conditions necessitates a shift in the volume set-point for VRAC toward a lower value.35 Following the increased Cl- conductance during AVD, the cells depolarize which facilitates apoptotic K+ loss.78 In several multidrug-resistant cancer cell types, there is a reduction in VRAC, which limits the initial cell shrinkage, and hence protects the cell against apoptosis.70,74,80-82 Using multidrug-resistant EATC (MDR EATC) as an illustrative example, it is seen from Figure 8A that MDR EATC show no initial AVD response after exposure to the platinum based chemotherapeutic drug cisplatin, whereas wild type EATC (WT EATC) show a significant cell shrinkage within 10 hours following the drug exposure. Within this time frame WT EATC but not MDR EATC enters apoptosis, seen as an increase in Caspase-3 activity (Fig. 8B). Patch-clamp experiments indicate that VRAC is reduced in MDR EATC compared to WT EATC (Fig. 8C). Finally, Figure 8D shows that prevention of VRAC activity (NS3728) renders WT EATC resistant to cisplatin, i.e., WT EATC now express a MDR phenotype. Thus, cisplatin resistance correlates with impaired VRAC activity and lack of AVD.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Apoptotic volume decrease, Cisplatin sensitivity, and Chloride conductance in WT EATC and MDR EATC. (A) Cell volume, determined by electronic cell sizing was followed with time in WT EATC and MDR EATC following exposure to 5 µM Cisplatin. Values are given relative to the initial cell volume. (B) Apoptotic progress in EATC and MDR EATC following exposure to 5 µM Cisplatin was determined as an increase in Caspase 3 activity. Values are given relative to control cells not exposed to Cisplatin. (C) Swelling activated Cl- current (pA/pF) following exposure to hypotonicity (2/3 of the isotonic value) was determined by patch clamp technique at +80 mV. (D) Effect of VRAC inhibition on Cisplatin induced apoptose (Caspase 3 activity) was determined in the absence and presence of an increasing concentration the VRAC inhibitor NS3728 (added concentration indicated). Values are relative to Caspase activity in untreated control cells. Figure adapted from.74

Volume-Sensitive Organic Anion Transporters – VSOAC

Amino acids play an important role as organic osmolytes in mammalian cells, i.e., a reduced release and an increased accumulation of amino acids are reflected by an increase in cell volume and vice versa. Taurine (β-amino ethane sulphonic acid), which accounts for approximately 0.1% of our total bodyweight,83 is often used as a model to illustrate how cells modulate the cellular content of the organic osmolytes following cellular stress (osmotic challenge, hypoxia, ischemia).13 It is emphasized that a shift in the cellular taurine content will not only affect cell volume but also have an impact on membrane dynamics, metabolism, antioxidative capacity as well as apoptotic progression and drug resistance (see e.g.,13). An extraordinarily high cellular to extracellular taurine concentration gradient (400:1) is reported in e.g. EATC and the retina,84,85 which reflects a low plasma membrane permeability to the zwitter-ionic taurine (high water solubility/low lipophilicity) and the presence of a Na+-dependent, high-affinity transporter TauT (SLC6A6) in the plasma membrane.13 However, it has been demonstrated that following osmotic cell swelling in e.g., EATC84 and NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts86,87 a net loss of taurine and hence restoration of cell volume are partly ensured by activation of a volume-sensitive leak pathway for organic osmolytes, designated VSOAC (volume sensitive organic anion channel) and a concomitant down-regulation of TauT. Using HeLa cells (Fig. 9A) or the human ovarian cancer cell line (Fig. 10C) as illustrative examples, it has been demonstrated that maximal release of organic osmolytes is obtained within minutes following osmotic challenge, where after the volume-sensitive release pathway inactivates, the release decreases. It has been estimated that 15% cell swelling is required for VSOAC activation in NIH3T3 cells.87 Swelling-induced activation of VSOAC has, in a variety of cell lines, been demonstrated to involve sequential activation of a cell-specific phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) and once activated, VSOAC activity can be modulated by (i) protein and phosphoinositide kinases/phosphatases, (ii) nucleotides/Ca2+/calmodulin, as well as (iii) ROS generated by NADPH oxidases.13,88,89

Figure 10.

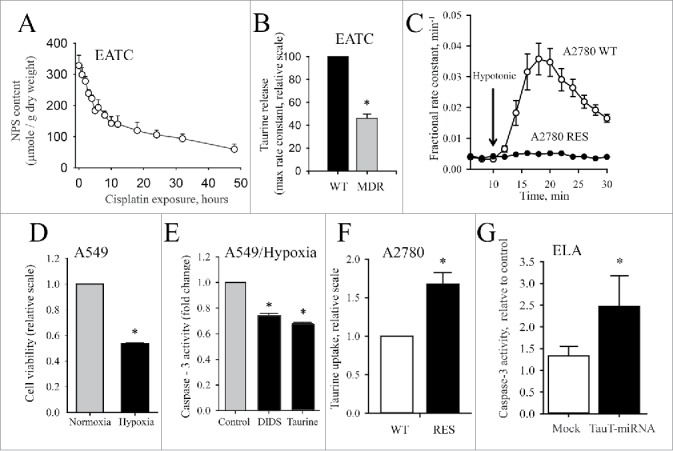

Downregulation of VSOAC and upregulation of TauT activity in drug resistant cells. (A) Release of amino acids in EATC following exposure to cisplatin under isotonic conditions. Amino acids content was determined as ninhydrin positive substances (NPS) and given relative to cell dry weight. Figure adapted from.74 (B) Down regulation of volume-sensitive taurine release via VSOAC in MDR EATC. Maximal obtainable rate constant for swelling induced taurine release was determined by tracer technique and values for MDR EATC cells given relative to WT EATC. Figure adapted from.74 (C) Down regulation of volume-sensitive taurine release via VSOAC in Cisplatin resistant human ovarian cancer cells (A2780 RES). Fractional rate constant (min-1) for taurine release was determined from release of 3H-labeled taurine isotonic and hypotonic conditions (shift in tonicity indicated by the arrow) in Cisplatin sensitive (WT) A2780 cells and RES A2780 cells. Figure adapted from95. (D) Loss of viability in human lung epithelial cell (A549) during hypoxia. Viability was determined by MTT assay. Hypoxia (1% O2, 94% N2, 5% CO2) was obtained by incubation of cells in a Biospherix ExVivo (Biospherix, Redfield, NY) for 18 hours. Figure adapted from79. (E) Prevention of taurine loss reduces apoptosis induced by hypoxia. Cells were exposed to hypoxia for 18 hours in the absence (Control) or presence of DIDS (inhibition of VSOAC) or 20 mM extracellular taurine (prevention of taurine loss by elimination of the cellular to extracellular taurine gradient). Figure adapted from79. (F) Cisplatin resistance in A2780 cells correlates with increased TauT activity. Taurine influx in A2780 WT and A2780 RES was determined by tracer technique and values given relative to values from WT cells. Figure adapted from95. (G) TauT knockdown renders ELA cells sensitive to cisplatin. TauT was knocked down by miRNA transfection. Influx determined by tracer technique in control ELA, mock miRNA- and TauT miRNA transfected cells. Values are given relative to influx in control ELA cells. Figure adapted from.93

VRAC vs. VSOAC

The molecular identity of VSOAC has been controversial and more than one channel has been demonstrated to be involved in release of organic osmolytes.90 VRAC has been suggested as a VSOAC candidate53,91 and as indicated below the discovery of LRRC8 family members as essential components of VSOAC and VRAC2,4 nourishes this hypothesis. However, there are discrepancies between VSOAC and VRAC, i.e., differences in (i) time course for swelling induced activation/inactivation of taurine (VSOAC) and I- (tracer for Cl-, VRAC) (Fig. 9A), (ii) osmotic set-point (Fig. 9B) and modulation of volume sensitivity by RhoA,24 (iii) sensitivity to cholesterol depletion (VSOAC activity decreased Fig. 9C/VRAC activity increased, Fig. 9D), (iv) sensitivity to membrane potential (VSOAC inhibited by depolarization / VRAC shows outward rectification and varying degree of inactivation at positive potentials7), and (v) regulation via integrin β1, i.e., VSOAC is unaffected by integrin β1 knockdown37 whereas VRAC is activated by integrin β1 stretch.34,38,92 Variation in stoichiometry of LRRC8 components and their regulation / localization to subdomain in the plasma membrane could explain differences between VSOAC and VRAC activities (see below).

VSOAC – Cell death and Drug resistance

Resistance to apoptosis induced by DNA-damaging drugs has been correlated to downregulation of pro-apoptotic transporters that release osmolytes and/or up-regulation of anti-apoptotic transporters that accumulate osmolytes.70 From Figure 10A it can be seen that the cellular amino acid pool in WT-EATC is significantly reduced within 10 hours following exposure to cisplatin, i.e., at the time point where apoptosis is detectable (Fig. 8B). However, in MDR-EATC (Fig. 10B) and cisplatin resistant A2780 (A2780 RES, Fig. 10C) the drug resistant phenotype correlates with a reduction in the volume-sensitive permeability to taurine. Hypoxia elicits, just like cisplatin exposure, loss in cell viability in human cancer lung cells (A549, Fig. 10D). However, hypoxia-induced caspase-3 activity is partly reduced when taurine release is prevented by addition of the VSOAC / VRAC inhibitor DIDS or elimination of the cellular to extracellular taurine gradient (high extracellular taurine) (Fig. 10E). Comparing (i) non-adherent cisplatin sensitive EATC with adherent, cisplatin resistant ELA,93 (ii) A2780 WT with A2780 RES (Fig. 10F)94,95 as well as (iii) colorectal cancer cell lines (LoVo, SW480, DLD1, HT-29, HCT116) with normal colonocytes96 it appears that TauT expression is high in drug resistant cells compared to their drug-sensitive parental counterparts which support earlier findings in kidney cells that cisplatin resistance complies with high expression of functional TauT.97 Furthermore, similar to findings in colorectal cancer by Yasunaga and Matsumuru96 we see that TauT knockdown enhances drug sensitivity in cisplatin-resistant ELA cells (Fig. 10G). It is noted that down-regulation of VSOAC activity in MDR-EATC is accompanied by a reduction in TauT expression and activity,98 which could indicate that down regulation of VSOAC in drug resistant cells contributes more to limitation in the initial cell shrinkage following drug exposure74 than upregulation in the number of TauT copies in the plasma membrane. Whether the actual cellular taurine content affects apoptotic progress has been questioned,93 but taurine supplementation experiments reveal that taurine not only attenuates the onset of apoptosis induced by hypoxia (rat retinal ganglion cells99), exposure to high glucose (retinal glial cells100) and IL-2 (anti-CD3-activated Jurkat cells101), but also interferes with apoptotic signaling through down regulation of ligands for the death receptors,101 reduction in DNA fragmentation, and cell shrinkage (Jurkat T-lymphocytes102), prevention of cytochrome c release99 and suppression of Apaf-1/caspase-9 apoptosome assembly (cardiomyocytes103). Under hypoxic, ischemic, swollen conditions, where taurine is released to a constrained extracellular compartment, one could envision taurine as an anti-apoptotic agent.

The LRRC8 Family – Important Components of VRAC and VSOAC

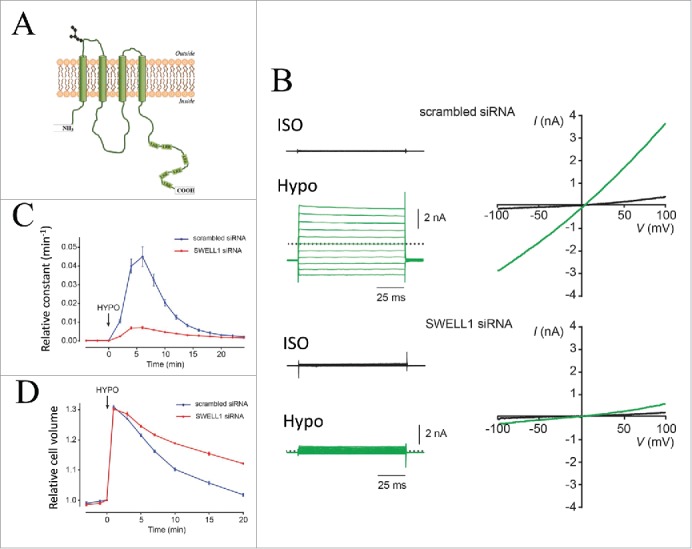

In April 2014, 2 groups simultaneously identified the LRRC8A protein also known as SWELL1 (Fig. 11A) as being an essential component of VRAC / VSOAC.2,4 LRRC8A is a member of the plasma membrane spanning protein leucine-rich-repeat-containing LRRC8 family, which was originally described in a girl that lacked B cells in peripheral blood, and who suffered from congenital agamma-globulinemia and minor facial anomalies.104 The girl was found to carry a C-terminal truncated variant of the LRRC8A gene, and this truncation was identified as being the direct cause of the disease. Despite the role of the LRRC8 family in B cell maturation, the LRRC8 family has also been associated with adipocyte differentiation as well as lymphocyte and monocyte activation105-107 In Lrrc8a -/- mice prenatal/postnatal mortality is increased and although the mice appear normal at birth and feed normally their growth became retarded, the hind legs turn weak, the stratum corneum is thickened, cysts are formed in the kidneys and the mice become sterile (no ovarian corpora lutea).108

Figure 11.

LRRC8A / SWELL1 knockdown abolishes endogenous VRAC currents, VSOAC activity and ability to perform RVD following hypoosmotic cells swelling. (A) Putative LRCC8A model. LRR indicates leucine reach repeats. LRRC8 proteins may form hexameric channels.109 (B) Whole-cell currents (right) monitored by voltage step protocols (left) under isotonic conditions (black) and after 6 min in hypotonic solution (210 mOsm/kg Hypo, green) in HEK293T cells transfected with either scrambled or SWELL1 siRNA. (C) Rate constant for swelling-induced 3H-taurine efflux in HeLa cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA (black) or siRNA against SWELL1 (blue). Shift in tonicity to hypotonic solution (210 mOsm/kg) is indicated by an arrow. (D) Cell volume under isotonic conditions and following exposure to hypotonic solution (220 mOsm/kg; indicated by the arrow) in HeLa cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA (black) or siRNA against SWELL1, blue). Panels B, C, D © Elsevier. Reproduced by permission of Elsevier. Permission to reuse must be obtained from the rightsholder.

The LRRC8 family is composed of 4 transmembrane segments located at the N-terminal half of the protein and as illustrated for LRRC8A in Figure 11A a leucine rich repeat domain carrying up to 17 leucine-rich repeats (only 6 are shown in LRRC8A) located at the C-terminal end.109 Sequence comparison of the LRRC8 family, which is composed of 5 members (A-E), has revealed that the LRRC8 proteins share a common ancestor with pannexines, a protein family considered to form hexameric channels and known to be involved in leakage of Ca2+ from the ER and ATP-dependent cell death.109,110 With respect to VRAC / VSOAC activity Patapoutian and coworkers2 demonstrated that LRRC8A localizes to the plasma membrane and that LRRC8A current resembles VRAC (ICl,swell) with respect to ion selectivity (I->Cl-), sensitivity to inhibitors and a mild outwardly rectification. Transfection with siRNA against LRRC8A prevented endogenous VRAC current (Fig. 11B), volume sensitive taurine efflux (Fig. 11C) and the overall ability to perform RVD (Fig. 11D). Jentsch and coworkers4 at the same time demonstrated a LRRC8A ion selectivity similar to VRAC (I->NO3->Cl->gluconate), that LRRC8B-E translocation to the plasma membrane required LRRC8A and that disruption of LRRC8B-E in contrast to LRRC8A disruption had no effect on VRAC current. As ICl,swell and the swelling-induced release of taurine are abolished in LRRC8A-/- cells as well as LRRC8(B/C/D/E)-/- cells, it was suggested that VRAC and VSOAC activities depend on LRRC8 heteromerization and that VRAC and VSOAC are most likely identical.2,4 As indicated above this conclusion does not exclude that variation in substrate preference (ions versus organic osmolytes), gating mechanisms for LRRC8 (yet unknown), osmo-sensitivity as well as channel localization to specific subcellular domains (calveolae, rafts) could be dictated by the stoichiometry of the LRRC8 subunits forming the functional, volume-activated channel.

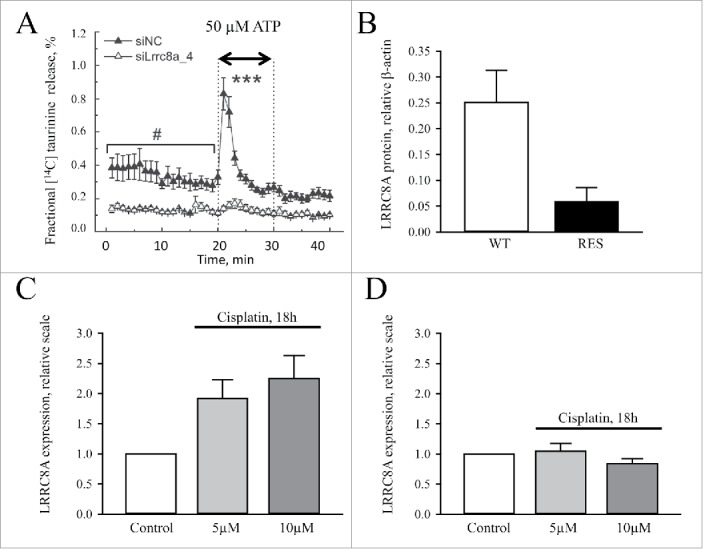

Later in 2014, Mongin and colleagues111 demonstrated that LRRC8A expression was also essential for ATP-induced release of excitatory amino acids (glutamate and taurine (Fig. 12A) in rat astrocytes under isosmotic conditions, indicating an important role of LRRC8A in astrocyte-to-neuron purinergic signaling. Our newest data show that LRRC8A is markedly down-regulated in the cisplatin-resistant human ovarian A2780 cancer cell line compared to the drug-sensitive parental cell line (Fig. 12B), and that this downregulation correlates with an absent swelling-induced taurine efflux (Fig. 10C) and an inability to volume regulate.95 Furthermore, 18 hour cisplatin treatment results in a 2-2.25 fold increase in the LRRC8A protein content in the cisplatin-sensitive A2780 cells (Fig. 12C), whereas the protein expression in resistant cells was unaffected by cisplatin (Fig. 12D). Thus, an increase in LRRC8A expression correlates with initiation of apoptosis in wild type A2780 cells whereas a reduction in the protein expression correlates with development of cisplatin resistance.

Figure 12.

LRRC8A plays a central role in ATP-induced release of excitatory amino acids and Cisplatin resistance. (A) Taurine release from rat astrocytes treated with mock (siNC) or LRRC8A_4 siRNA. Taurine release is determined as the fractional release of 14C-taurine from preloaded cells before and after addition of ATP (50 µM). Figure adapted from111. (B, C, D) LRRC8A protein expression in Cisplatin-sensitive (WT) and Cisplatin-resistant (RES) human ovarian cancer cells (A2780) without (Control) or with 18 hours pretreatment with 5 / 10 µM Cisplatin. Figure is adapted from.95

Anoctamin1 – ANO1

ANO1 – Identification – Biophysical properties

In 2008 3 different groups identified a member of the Anoctamin family, i.e., ANO1 which was found to translocate to the plasma membrane where it provokes a current with the same characteristics as the well-known Ca2+ dependent Cl- current (CaCC).1,3,5 The Anoctamin family has 10 members all with 8 transmembrane domains and the NH2 and COOH termini exposed to the cytosolic side.112 It is shown that functional ANO1 is an obligate dimer, i.e., dimerization of units happens en route to the plasma membrane.113,114 For characterization of Anoctamin structure and function see refs.115-118. In the following we focus on ANO1.

ANO1 current exhibits typical characteristics: (i) Ion selectivity follows a type I Eisenmann sequence,3,5 (ii) Dependence on cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 13) and membrane voltage (outwardly rectifying) with activation at positive potentials at sub-micromolar [Ca2+]i,119 and (iii) ANO1 becomes voltage insensitive (linear steady state I-V relationship) at higher micromolar [Ca2+]i.120 Concomitantly, the time-dependent component of ANO1 activation disappears.1,3,5,119

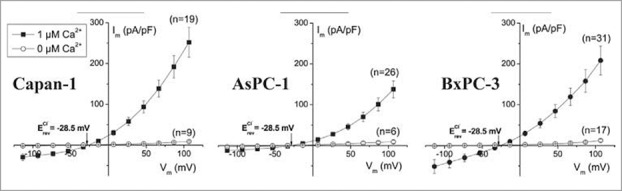

Figure 13.

Steady-state I–V relationship of Cl- current in Capan-1, AsPC-1, and BxPC-3 cells in the presence and absence of intracellular Ca2+. Steady-state current voltage relationships of Capan-1, AsPC-1, and BxPC-3 cells with and without Ca2+ in intracellular solution evoked by families of voltage steps from −100 to +100 mV in 20 mV increments. Figure adapted from.120

ANO1 – Pharmacological profile

Verkmanns group identified 2 ANO1 inhibitors (T16inh-A01; CaCCinh-A01),50,51 which have no effect on VRAC (Fig. 3) although some side effects of CaCCinh-A01 on Ca2+ signaling was reported.120,121 In addition the VRAC inhibitor NS3728 was found to be an inhibitor of ANO1 (IC50 ∼1.3 μM120). Finally Eugenol is an ANO1-antagonist with an IC50 ∼150 μM122 and gallotannins, which are found in red wine and green tea, also potently inhibit ANO1.123

Activation and modulation of ANO1 activity

ANO1 contains no canonical Ca2+ binding motif questioning whether the Ca2+-dependent gating is controlled by direct binding of Ca2+ to ANO1. Acidic residues on the 3rd intracellular loop participate in the regulation of the protein activity by Ca2+117,124,125 and recently, Bill and coworkers identified mutations in ANO1 that affected channel activity and they demonstrated that a specific mutation (S741T) in a proposed re-entrant loop, connected to 2 Ca2+-binding sites, increased the calcium sensitivity of ANO1 and at the same time rendered the Ca2+-gating voltage-independent.126 Two putative CaM binding sites were identified on ANO1, which led to the proposal that Ca2+ sensitivity is mediated by calmodulin.46,127 Recent papers did however present strong evidence against the possible role of calmodulin.128,129 The most direct evidence that the Ca2+ sensitivity is intrinsic and not dependent on calmodulin comes from the observation that purified ANO1 reconstituted in liposomes recapitulates the functional properties of ANO1.129 Hence, the Ca2+/calmodulin issue is still controversial. Ca2+ independent regulation of ANO1 has also been suggested because 2 intracellular binding sites for ERK were shown to be necessary for receptor-mediated activation of ANO1.130 ANO1 interacts with actin-binding proteins belonging to the ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) network and knockdown of moesin reduced ANO1 current by >50 % without affecting the surface expression.131

Role of ANO1 in cancer cells

Expression in cancer cells

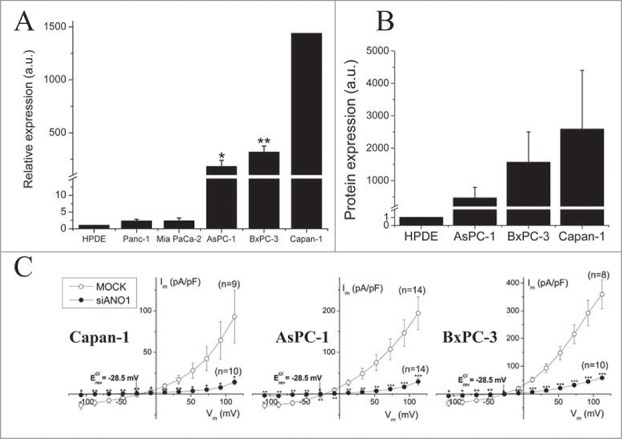

ANO1 was originally identified as a protein overexpressed in several tumors,112 where it was designated DOG-1 (Discovered on Gastrointestinal stromal tumor), ORAOV2 (Oral cancer overexpressed) and TAOS2 (tumor amplified and overexpressed sequence).132-134 The coding sequence for ANO1 is located on amplicon 11q13, which contains the coding sequence for several proteins related to cell cycle, proliferation and apoptosis, and which is often amplified in cancers with poor prognosis.118,135-138 ANO1 is upregulated in several cancer tissues including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, prostate, breast, pancreatic cancer and gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells.120,139-142 Figure 14A and 14B show overexpression of ANO1 at the mRNA level and the protein level, respectively, in PDAC cells compared to normal human pancreatic ductal epithelium cells (HPDE). Finally, the functional expression of ANO1 was assessed using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique (steady-state I-V relationship) and cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or siRNA targeting ANO1. It is seen that the Ca2+-sensitive Cl- current is reduced by more than 80% following ANO1 gene silencing, indicating that the current is conducted by ANO1. Together the data in Figure 14 indicate a strong over expression of ANO1 in the carcinogenic pancreatic ductal epithelium cells.

Figure 14.

ANO1 is overexpressed in human pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. (A) ANO1 expressions at the mRNA level is demonstrated by RT-qPCR in the 5 PDAC cell lines Panc-1, Mia PaCa-2, BxPC-3, AsPC-1, and Capan-1. Values are relative to the immortalized human pancreatic ductal epithelium cell line (HPDE). (B) ANO1 expressions at the protein level is demonstrated by Western blot analysis in 3 pancreatic cancer cell lines and HPDE using β-actin as a loading control. C: Steady-state I–V relationships of cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA (MOCK) or siRNA targeting ANO1. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed with 1 μM Ca2+ in pipette solution. Figure adapted from.120

Proliferation

A pro-proliferative role of ANO1 is found in most cancer cells investigated118,141-146 and Stanich and coworkers demonstrated that ANO1 regulates cell proliferation at the G1/S transition in the cell cycle.147 Other studies, however, show that cell proliferation in certain cell types is unaffected by ANO1, e.g. ANO1 overexpression or knockdown do not affect proliferation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)137,139 and ANO1 knockdown does not affect proliferation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells.120 ANO1 isoforms are shown to produce different channel characteristics (voltage and Ca2+ dependency).148 However, as expression of these ANO1 isoforms does not affect proliferation or migration differently and does not associate with specific cancer tissues Ubby and coworkers suggested that the actual ANO1 channel activities are not directly involved in cell growth and motility.149

Apoptosis

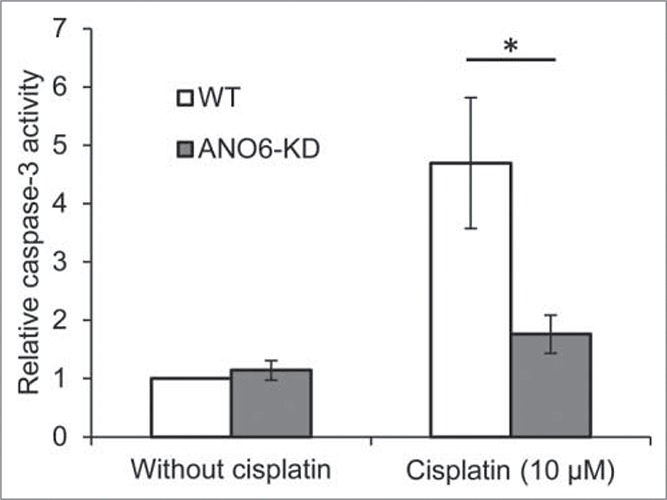

As described above (1.4), activation of Cl- channels under isovolumetric conditions results in cell shrinkage that is required for initiation of apoptosis.78 VRAC is known to play an important role in this process but also ANO proteins appear to play a role in AVD/apoptotic cell death in several cell types investigated.45,150,151 The amplicon 11q13 contains the Ano1 gene as well as well as a Fas-Associated protein with Death Domain (FADD) gene, i.e., a gene associated with apoptosis, suggesting a coupling between the regulation of ANO1 and cell death. Not much is published about ANO1 and apoptosis. Inhibition of ANO1 is shown to shift gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells from early apoptotic to late apoptotic stages.140 ANO6 has received more attention in relation to apoptosis compared to ANO1 and in particular its role as a putative scramblase involved in the redistribution of phospholipids between the outer/inner membrane during apoptosis.118,152,153 siRNA KD of ANO6 reduces cisplatin induced Caspase 3 activation (apoptosis) in ELA cells (Fig. 15) and staurosporine induced cell death in lung epithelial cells (A549151). On the other hand, Okada and coworkers found that ANO6 KD has no effect on staurosporine induced AVD.154 Hence, the role of ANO6 in AVD/apoptosis seems to vary among cell types.

Figure 15.

ANO6 is involved in Cisplatin induced cells death. Caspase-3 activity in WT and ANO6-KD ELA cells was determined in untreated control cells and cells exposed to 10 µM Cisplatin for 24 hours. Figure adapted from.40

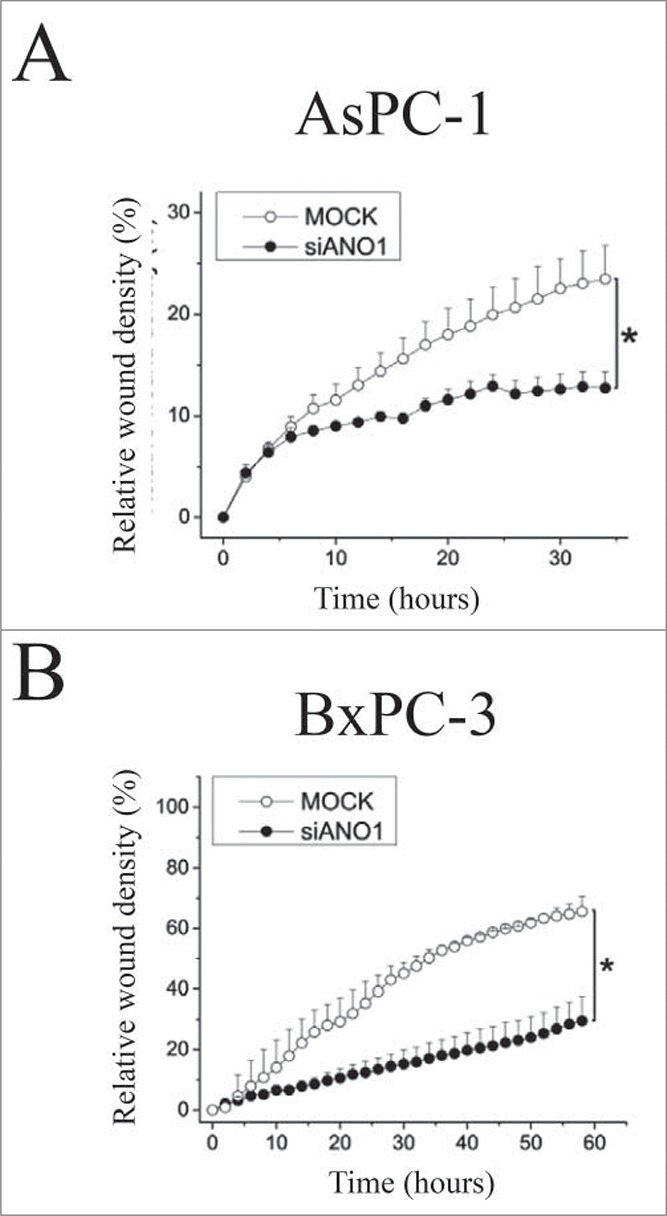

Migration and metastasis

Cell migration is shown to involve local cell volume changes, e.g., cells retract at the rear part due to activation of K+ and Cl- channels and hence cell shrinkage.73 Cell migration is Ca2+-dependent155 and Ca2+-activated channels have been allocated a role in cell migration in several cell types (see73). Migration analysis in ELA cells after knockdown of either ANO1 or ANO6 showed that the directional cell migration involves ANO1 and that the migration rate involves ANO6.156 Figure 16 shows relative wound density over time monitored in 2 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines (AsPC-1; BxPC-3) following ANO1 siRNA knockdown.120 ANO1 knockdown resulted in a decreased migratory rate. Although many studies have shown the importance of ANO1 in migration137,139,141,145,146,156 there are also studies demonstrating that ANO1 might act indirectly. Thus, Ubby et al. overexpressed ANO1 in HEK293 cells and measured large ANO1-like currents, but no effect on migration was observed.149 There are several reports highlighting the importance of ANO1 in cancer cell metastasis, i.e., Shi and coworkers demonstrated a correlation between ANO1 overexpression and lymph node metastasis of ESCC and advanced clinical stage of cancers157 and Ayoub and collaborators found that increased ANO1 expression correlates with increased risk of developing metastases in oral and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas.139 In contrast, Shiwarshi and coworkers find that reduced ANO1 expression slows proliferation and allow metastatic progression and they suggest that ANO1 expression is a switch between growth and metastasis.143

Figure 16.

ANO1 is essential for cell migration. Migration was determined by a scratch wound healing assay (density of wounded area relative to confluency of cell region) over time in AsPC-1 (A) and BxPC-3 (B) cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA (5 nM)(MOCK) or siRNA targeting ANO1 (50 nM). Figure adapted from.120

Concluding Remarks

Many physiological and pathophysiological processes are controlled by the activity of anion channels. This has as described above mainly been demonstrated by inadequate and questionable inhibitors. As CaCC and essential components of VRAC/VSOAC have now been cloned previous data can be verified by molecular tools and transgenic cells/animals. Obvious question to be answered is (i) how closely related are VRAC and VSOAC, (ii) are CaCC and VRAC contributing equally to proliferation, migration and apoptosis, and (iii) their respective pro-proliferative role in cancer cells, metastasis and development of multidrug resistance.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

Work in the author's laboratory is supported by grants from the Danish Council for Independent Research/Medical Sciences; The Carlsberg Foundation, Augustinus Foundation, and Marie Curie Initial Training Network IonTraC (Grant Agreement No. 289648).

References

- 1.Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, Pfeffer U, Ravazzolo R, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science 2008; 322:590-4; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1163518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiu Z, Dubin AE, Mathur J, Tu B, Reddy K, Miraglia LJ, Reinhardt J, Orth AP, Patapoutian A. SWELL1, a plasma membrane protein, is an essential component of volume-regulated anion channel. Cell 2014; 157:447-58; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell 2008; 134:1019-29; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voss FK, Ullrich F, Munch J, Lazarow K, Lutter D, Mah N, Andrade-Navarro MA, von Kries JP, Stauber T, Jentsch TJ. Identification of LRRC8 Heteromers as an Essential Component of the Volume-Regulated Anion Channel VRAC. Science 2014; 344:634-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1252826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, et al.. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature 2008; 455:1210-5; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen SF, Kapus A, Hoffmann EK. Osmosensory mechanisms in cellular and systemic volume regulation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22:1587-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH, Pedersen SF. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol Rev 2009; 89:193-277; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen EH, Hoffmann EK. Volume Regulation in Epithelia, In: Hamilton KL, Devor DC, eds. Ion Channels and Transporters of Epithelia in Health and Disease. APS / Springer, 2015: In the press [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akita T, Okada Y. Characteristics and roles of the volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying (VSOR) anion channel in the central nervous system. Neuroscience 2014; 275:211-31; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann EK. Regulation of cell volume by selective changes in the leak permeabilities of Ehrlich ascites tumor cells, Alfred Benzon Symposium 1978, XI:397-417. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert IH, Hoffmann EK, Jorgensen F. Membrane potential, anion and cation conductances in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. J Membr Biol 1989; 111:113-31; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF01871776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert IH, Hoffmann EK, Pedersen SF. Cell volume regulation: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Acta Physiol Scand 2008; 194:255-82; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01910.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert IH, Kristensen DM, Holm JB, Mortensen OH. Physiological role of taurine - from organism to organelle. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015; 213:191-212; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/apha.12365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grinstein S, Clarke CA, Dupre A, Rothstein A. Volume-induced increase of anion permeability in human lymphocytes. J Gen Physiol 1982; 80:801-23; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.80.6.801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann EK, Simonsen LO, Sjoholm C. Membrane potential, chloride exchange, and chloride conductance in Ehrlich mouse ascites tumour cells. J Physiol 1979; 296:61-84; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cahalan MD, Lewis RS. Role of potassium and chloride channels in volume regulation by T lymphocytes. Soc Gen Physiol Ser 1988; 43:281-301; PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazama A, Okada Y. Ca2+ sensitivity of volume-regulatory K+ and Cl- channels in cultured human epithelial cells. J Physiol 1988; 402:687-702; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilius B, Eggermont J, Voets T, Buyse G, Manolopoulos V, Droogmans G. Properties of volume-regulated anion channels in mammalian cells. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 1997; 68:69-119; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0079-6107(97)00021-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilius B, Droogmans G. Amazing chloride channels: an overview. Acta Physiol Scand 2003; 177:119-47; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01060.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okada Y. Volume expansion-sensing outward-rectifier Cl- channel: fresh start to the molecular identity and volume sensor. Am J Physiol 1997; 273:C755-C789; PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabirov RZ, Prenen J, Tomita T, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Reduction of ionic strength activates single volume-regulated anion channels (VRAC) in endothelial cells. Pflugers Arch 2000; 439:315-20; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s004249900186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voets T, Droogmans G, Raskin G, Eggermont J, Nilius B. Reduced intracellular ionic strength as the initial trigger for activation of endothelial volume-regulated anion channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96:5298-303; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nilius B, Voets T, Prenen J, Barth H, Aktories K, Kaibuchi K, Droogmans G, Eggermont J. Role of Rho and Rho kinase in the activation of volume-regulated anion channels in bovine endothelial cells. J.Physiol 1999; 516 ( Pt 1):67-74; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.067aa.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedersen SF, Beisner KH, Hougaard C, Willumsen BM, Lambert IH, Hoffmann EK. Rho family GTP binding proteins are involved in the regulatory volume decrease process in NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts. J Physiol 2002; 541:779-96; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tilly BC, Edixhoven MJ, Tertoolen LG, Morii N, Saitoh Y, Narumiya S, de Jonge HR. Activation of the osmo-sensitive chloride conductance involves P21rho and is accompanied by a transient reorganization of the F-actin cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell 1996; 7:1419-27; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.7.9.1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klausen TK, Hougaard C, Hoffmann EK, Pedersen SF. Cholesterol modulates the volume-regulated anion current in Ehrlich-Lettre ascites cells via effects on Rho and F-actin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006; 291:C757-C771; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00029.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitan I, Christian AE, Tulenko TN, Rothblat GH. Membrane cholesterol content modulates activation of volume-regulated anion current in bovine endothelial cells. J Gen Physiol 2000; 115:405-16; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.115.4.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen O, Hoffmann EK. Cell swelling activates K+ and Cl- channels as well as nonselective, stretch-activated cation channels in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. J Membr Biol 1992; 129:13-36; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00232052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du XL, Gao Z, Lau CP, Chiu SW, Tse HF, Baumgarten CM, Li GR. Differential effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on volume-sensitive chloride current in human atrial myocytes: evidence for dual regulation by Src and EGFR kinases. J Gen Physiol 2004; 123:427-39; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.200409013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lepple-Wienhues A, Szabo I, Laun T, Kaba NK, Gulbins E, Lang F. The tyrosine kinase p56lck mediates activation of swelling-induced chloride channels in lymphocytes. J Cell Biol 1998; 141:281-6; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.141.1.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lepple-Wienhues A, Szabo I, Wieland U, Heil L, Gulbins E, Lang F. Tyrosine kinases open lymphocyte chloride channels. Cell Physiol Biochem 2000; 10:307-12; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000016363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tilly BC, van den BN, Tertoolen LG, Edixhoven MJ, de Jonge HR. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation is involved in osmoregulation of ionic conductances. J Biol Chem 1993; 268:19919-22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voets T, Manolopoulos V, Eggermont J, Ellory C, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Regulation of a swelling-activated chloride current in bovine endothelium by protein tyrosine phosphorylation and G proteins. J Physiol 1998; 506 ( Pt 2):341-52; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.341bw.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. Angiotensin II (AT1) receptors and NADPH oxidase regulate Cl- current elicited by beta1 integrin stretch in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol 2004; 124:273-87; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.200409040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimizu T, Numata T, Okada Y. A role of reactive oxygen species in apoptotic activation of volume-sensitive Cl(−) channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101:6770-3; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0401604101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varela D, Simon F, Riveros A, Jorgensen F, Stutzin A. NAD(P)H oxidase-derived H2O2 signals chloride channel activation in cell volume regulation and cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:13301-4; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.C400020200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sørensen BH, Rasmussen LJH, Broberg BS, Klausen TK, Sauter DPR, Lambert IH, Aspberg A, Hoffmann EK. Integrin B1, Osmosensing, and Chemoresistance in Mouse Ehrlich Carcinoma Cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2015; 36:111-32; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000374057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. Stretch of β 1 integrin activates an outwardly rectifying chloride current via FAK and Src in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol 2003; 122:689-702; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.200308899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doroshenko P, Neher E. Volume-sensitive chloride conductance in bovine chromaffin cell membrane. J Physiol 1992; 449:197-218; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juul CA, Grubb S, Poulsen K, Kyed T, Hashem N, Lambert IH, Larsen EH, Hoffmann EK. Anoctamin 6 differs from VRAC and VSOAC but is involved in apoptosis and supports volume regulation in the presence of Ca2+. Pflugers Archiv 2013; 466(10):1899-910; DOI: 10.1007/s00424-013-1428-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedersen SF, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Hoffmann EK, Nilius B. Separate swelling- and Ca2+-activated anion currents in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. J Membr Biol 1998; 163:97-110; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s002329900374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szucs G, Buyse G, Eggermont J, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Characterization of volume-activated chloride currents in endothelial cells from bovine pulmonary artery. J Membr Biol 1996; 149:189-97; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s002329900019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bond T, Basavappa S, Christensen M, Strange K. ATP dependence of the ICl, swell channel varies with rate of cell swelling. Evidence for two modes of channel activation. J Gen Physiol 1999; 113:441-56; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.113.3.441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eggermont J, Trouet D, Carton I, Nilius B. Cellular function and control of volume-regulated anion channels. Cell Biochem Biophys 2001; 35:263-74; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1385/CBB:35:3:263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almaca J, Tian Y, Aldehni F, Ousingsawat J, Kongsuphol P, Rock JR, Harfe BD, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. TMEM16 proteins produce volume-regulated chloride currents that are reduced in mice lacking TMEM16A. J Biol Chem 2009; 284:28571-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M109.010074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian Y, Kongsuphol P, Hug M, Ousingsawat J, Witzgall R, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Calmodulin-dependent activation of the epithelial calcium-dependent chloride channel TMEM16A. FASEB J 2011; 25:1058-68; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1096/fj.10-166884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voets T, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Modulation of voltage-dependent properties of a swelling-activated Cl- current. J Gen Physiol 1997; 110:313-25; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.110.3.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helix N, Strobaek D, Dahl BH, Christophersen P. Inhibition of the endogenous volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC) in HEK293 cells by acidic di-aryl-ureas. J Membr Biol 2003; 196:83-94; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00232-003-0627-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrigan TJ, Abdullaev IF, Jourd'heuil D, Mongin AA. Activation of microglia with zymosan promotes excitatory amino acid release via volume-regulated anion channels: the role of NADPH oxidases. J Neurochem 2008; 106:2449-62; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05553.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Namkung W, Phuan PW, Verkman AS. TMEM16A inhibitors reveal TMEM16A as a minor component of calcium-activated chloride channel conductance in airway and intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:2365-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De La Fuente R, Namkung W, Mills A, Verkman AS. Small-molecule screen identifies inhibitors of a human intestinal calcium-activated chloride channel. Mol Pharmacol 2008; 73:758-68; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1124/mol.107.043208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pedersen SF, Klausen TK, Nilius B. The identification of a volume-regulated anion channel: an amazing Odyssey. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015; 213:868-81; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/apha.12450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strange K, Emma F, Jackson PS. Cellular and molecular physiology of volume-sensitive anion channels. Am J Physiol 1996; 270:C711-C730; PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piper AS, Large WA. Multiple conductance states of single Ca2+-activated Cl- channels in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 2003; 547:181-96; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adomaviciene A, Smith KJ, Garnett H, Tammaro P. Putative pore-loops of TMEM16/anoctamin channels affect channel density in cell membranes. J Physiol 2013; 591:3487-505; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.251660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rouzaire-Dubois B, Malo M, Milandri JB, Dubois JM. Cell size-proliferation relationship in rat glioma cells. Glia 2004; 45:249-57; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/glia.10320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Habela CW, Sontheimer H. Cytoplasmic volume condensation is an integral part of mitosis. Cell Cycle 2007; 6:1613-20; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.6.13.4357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Habela CW, Olsen ML, Sontheimer H. ClC3 is a critical regulator of the cell cycle in normal and malignant glial cells. J Neurosci 2008; 28:9205-17; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1897-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Habela CW, Ernest NJ, Swindall AF, Sontheimer H. Chloride accumulation drives volume dynamics underlying cell proliferation and migration. J Neurophysiol 2009; 101:750-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/jn.90840.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doroshenko P, Sabanov V, Doroshenko N. Cell cycle-related changes in regulatory volume decrease and volume-sensitive chloride conductance in mouse fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol 2001; 187:65-72; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/1097-4652(200104)187:1%3c65::AID-JCP1052%3e3.0.CO;2-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klausen TK, Preisler S, Pedersen SF, Hoffmann EK. Monovalent ions control proliferation of Ehrlich Lettre ascites cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2010; 299:C714-C725; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00445.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shen MR, Droogmans G, Eggermont J, Voets T, Ellory JC, Nilius B. Differential expression of volume-regulated anion channels during cell cycle progression of human cervical cancer cells. J Physiol 2000; 529 Pt 2:385-94; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00385.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen LX, Zhu LY, Jacob TJ, Wang LW. Roles of volume-activated Cl- currents and regulatory volume decrease in the cell cycle and proliferation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cell Prolif 2007; 40:253-67; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00432.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.He D, Luo X, Wei W, Xie M, Wang W, Yu Z. DCPIB, a specific inhibitor of volume-regulated anion channels (VRACs), inhibits astrocyte proliferation and cell cycle progression via G1/S arrest. J Mol Neurosci 2012; 46:249-57; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12031-011-9524-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang B, Hattori N, Liu B, Nakayama Y, Kitagawa K, Inagaki C. Suppression of cell proliferation with induction of p21 by Cl(−) channel blockers in human leukemic cells. Eur J Pharmacol 2004; 488:27-34; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klausen TK, Bergdahl A, Hougaard C, Christophersen P, Pedersen SF, Hoffmann EK. Cell cycle-dependent activity of the volume- and Ca2+-activated anion currents in Ehrlich lettre ascites cells. J Cell Physiol 2007; 210:831-42; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.20918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li M, Wang B, Lin W. Cl-channel blockers inhibit cell proliferation and arrest the cell cycle of human ovarian cancer cells. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2008; 29:267-71; PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nilius B. Chloride channels go cell cycling. J.Physiol 2001; 532:581; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0581e.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wondergem R, Gong W, Monen SH, Dooley SN, Gonce JL, Conner TD, Houser M, Ecay TW, Ferslew KE. Blocking swelling-activated chloride current inhibits mouse liver cell proliferation. J Physiol 2001; 532:661-72; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0661e.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH. Ion channels and transporters in the development of drug resistance in cancer cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2014; 369:20130109; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rstb.2013.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mao J, Wang L, Fan A, Wang J, Xu B, Jacob TJ, Chen L. Blockage of volume-activated chloride channels inhibits migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2007; 19:249-58; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000102388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schneider L, Klausen TK, Stock C, Mally S, Christensen ST, Pedersen SF, Hoffmann EK, Schwab A. H-ras transformation sensitizes volume-activated anion channels and increases migratory activity of NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Pflugers Arch 2008; 455:1055-62; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00424-007-0367-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schwab A, Fabian A, Hanley PJ, Stock C. Role of ion channels and transporters in cell migration. Physiol Rev 2012; 92:1865-913; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00018.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Poulsen KA, Andersen EC, Hansen CF, Klausen TK, Hougaard C, Lambert IH, Hoffmann EK. Deregulation of apoptotic volume decrease and ionic movements in multidrug-resistant tumor cells: role of chloride channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2010; 298:C14-C25; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00654.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maeno E, Ishizaki Y, Kanaseki T, Hazama A, Okada Y. Normotonic cell shrinkage because of disordered volume regulation is an early prerequisite to apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97:9487-92; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.140216197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maeno E, Takahashi N, Okada Y. Dysfunction of regulatory volume increase is a key component of apoptosis. FEBS Lett 2006; 580:6513-7; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okada Y, Maeno E, Shimizu T, Dezaki K, Wang J, Morishima S. Receptor-mediated control of regulatory volume decrease (RVD) and apoptotic volume decrease (AVD). J Physiol 2001; 532:3-16; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0003g.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lang F, Hoffmann EK. Role of ion transport in control of apoptotic cell death. Compr Physiol 2012; 2:2037-61; PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Holm JB, Grygorczyk R, Lambert IH. Volume-sensitive release of organic osmolytes in the human lung epithelial cell line A. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2013; 305:C48-C60; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00412.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee EL, Shimizu T, Ise T, Numata T, Kohno K, Okada Y. Impaired activity of volume-sensitive Cl- channel is involved in cisplatin resistance of cancer cells. J Cell Physiol 2007; 211:513-21; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.20961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lehen'kyi V, Shapovalov G, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Ion channnels and transporters in cancer. Five. Ion channels in control of cancer and cell apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011; 301:C1281-C1289; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00249.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Min XJ, Li H, Hou SC, He W, Liu J, Hu B, Wang J. Dysfunction of volume-sensitive chloride channels contributes to cisplatin resistance in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood.) 2011; 236:483-91; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1258/ebm.2011.010297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huxtable RJ. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol Rev 1992; 72:101-63; PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH. Amino acid transport and cell volume regulation in Ehrlich ascites tumour cells. J Physiol 1983; 338:613-25; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pasantes-Morales H, Moran J, Fellman JH. Hypotaurine uptake by the retina. J Neurosci Res 1986; 15:101-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hansen DB, Friis MB, Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH. Down-regulation of the taurine transporter TauT during hypoosmotic stress in NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts. J Membrane Biol 2012; 245:77-87; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00232-012-9416-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lambert IH. Reactive oxygen species regulate swelling-induced taurine efflux in NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts. J Membr Biol 2003; 192:19-32; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00232-002-1061-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lambert IH. Regulation of the Cellular Content of the Organic Osmolyte Taurine in Mammalian Cells. Neurochem Res 2004; 29:27-63; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/B:NERE.0000010433.08577.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lambert IH, Jensen JV, Pedersen PA. mTOR ensures increased release and reduced uptake of the organic osmolyte taurine under hypoosmotic conditions in mouse fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2014; 306:C1028-C1040; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00005.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mongin AA, Reddi JM, Charniga C, Kimelberg HK. [3H]taurine and D-[3H]aspartate release from astrocyte cultures are differently regulated by tyrosine kinases. Am J Physiol 1999; 276:C1226-C1230; PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kirk K. Swelling-activated organic osmolyte channels. J Membr Biol 1997; 158:1-16; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s002329900239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. EGFR kinase regulates volume-sensitive chloride current elicited by integrin stretch via PI-3K and NADPH oxidase in ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol 2006; 127:237-51; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.200509366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tastesen HS, Holm JB, Møller J, Poulsen KA, Møller C, Stürup S, Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH. Pinpointing differences in cisplatin-induced apoptosis in adherent and non-adherent cancer cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2010; 26:809-20; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000323990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dam CS, Henarejos SAP, Tsolakou T, Segato CA, Gammelgaard B, Yellol GS, Ruiz J, Lambert IH, Stürup S. In vitro charaterization of a novel C,N-cyclometalated benzimidazole Ru(II) arene complex: stability, intracellular distribution and binding, effects on organic osmolyte homeostasis and induction of apoptosis. Metallomics 2015; 7(5):885-95; DOI: 10.1039/c5mt00056d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sørensen BH, Thorsteinsdottir AA, Lambert IH. Acquired cisplatin resistance in human ovarian cancer A2780 cells correlates with shift in taurine homeostasis and ability to volume regulate. Am J Physiol 2014; 307:C1071-C1080; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00274.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yasunaga M, Matsumura Y. Role of SLC6A6 in promoting the survival and multidrug resistance of colorectal cancer. Sci Rep 2014; 4:4852; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/srep04852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Han X, Yue J, Chesney RW. Functional TauT protects against acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20:1323-32; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2008050465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Poulsen KA, Litman T, Eriksen J, Mollerup J, Lambert IH. Downregulation of taurine uptake in multidrug resistant Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Amino Acids 2002; 22:333-50; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s007260200019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen K, Zhang Q, Wang J, Liu F, Mi M, Xu H, Chen F, Zeng K. Taurine protects transformed rat retinal ganglion cells from hypoxia-induced apoptosis by preventing mitochondrial dysfunction. Brain Res 2009; 1279:131-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zeng K, Xu H, Mi M, Chen K, Zhu J, Yi L, Zhang T, Zhang Q, Yu X. Effects of taurine on glial cells apoptosis and taurine transporter expression in retina under diabetic conditions. Neurochem Res 2010; 35:1566-74; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11064-010-0216-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maher SG, Condron CEM, Bouchier-Hayes DJ, Toomey DM. Taurine attenuates CD3/interleukin-2-induced T cell apoptosis in an in vitro model of activation-induced cell death (AICD). Clin Exp Immunol 2005; 139:279-86; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02694.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lang F, Madlung J, Siemen D, Ellory C, Lepple-Wienhues A, Gulbins E. The involvement of caspases in the CD95(Fas/Apo-1) but not swelling-induced cellular taurine release from Jurkat T-lymphocytes. Pflugers Arch 2000; 440:93-9; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s004240000247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Takatani T, Takahashi K, Uozumi Y, Shikata E, Yamamoto Y, Ito T, Matsuda T, Schaffer SW, Fujio Y, Azuma J. Taurine inhibits apoptosis by preventing formation of the Apaf-1/caspase-9 apoptosome. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2004; 287:C949-C953; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00042.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sawada A, Takihara Y, Kim JY, Matsuda-Hashii Y, Tokimasa S, Fujisaki H, Kubota K, Endo H, Onodera T, Ohta H, et al.. A congenital mutation of the novel gene LRRC8 causes agammaglobulinemia in humans. J Clin Invest 2003; 112:1707-13; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI18937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hayashi T, Nozaki Y, Nishizuka M, Ikawa M, Osada S, Imagawa M. Factor for adipocyte differentiation 158 gene disruption prevents the body weight gain and insulin resistance induced by a high-fat diet. Biol Pharm Bull 2011; 34:1257-63; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1248/bpb.34.1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kubota K, Kim JY, Sawada A, Tokimasa S, Fujisaki H, Matsuda-Hashii Y, Ozono K, Hara J. LRRC8 involved in B cell development belongs to a novel family of leucine-rich repeat proteins. FEBS Lett 2004; 564:147-52; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00332-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tominaga K, Kondo C, Johmura Y, Nishizuka M, Imagawa M. The novel gene fad104, containing a fibronectin type III domain, has a significant role in adipogenesis. FEBS Lett 2004; 577:49-54; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kumar L, Chou J, Yee CS, Borzutzky A, Vollmann EH, von Andrian UH, Park SY, Hollander G, Manis JP, Poliani PL, et al.. Leucine-rich repeat containing 8A (LRRC8A) is essential for T lymphocyte development and function. J Exp Med 2014; 211:929-42; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20131379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Abascal F, Zardoya R. LRRC8 proteins share a common ancestor with pannexins, and may form hexameric channels involved in cell-cell communication. Bioessays 2012; 34:551-60; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.201100173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Qu Y, Misaghi S, Newton K, Gilmour LL, Louie S, Cupp JE, Dubyak GR, Hackos D, Dixit VM. Pannexin-1 is required for ATP release during apoptosis but not for inflammasome activation. J Immunol 2011; 186:6553-61; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1100478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hyzinski-Garcia MC, Rudkouskaya A, Mongin AA. LRRC8A protein is indispensable for swelling-activated and ATP-induced release of excitatory amino acids in rat astrocytes. J Physiol 2014; 592:4855-62; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.278887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Katoh M, Katoh M. FLJ10261 gene, located within the CCND1-EMS1 locus on human chromosome 11q13, encodes the eight-transmembrane protein homologous to C12orf3, C11orf25 and FLJ34272 gene products. Int J Oncol 2003; 22:1375-81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fallah G, Romer T, Detro-Dassen S, Braam U, Markwardt F, Schmalzing G. TMEM16A(a)/anoctamin-1 shares a homodimeric architecture with CLC chloride channels. Mol Cell Proteomics 2011; 10:M110; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/mcp.M110.004697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sheridan JT, Worthington EN, Yu K, Gabriel SE, Hartzell HC, Tarran R. Characterization of the oligomeric structure of the Ca(2+)-activated Cl- channel Ano1/TMEM16A. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:1381-8; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.174847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hoffmann EK, Holm NB, Lambert IH. Functions of volume-sensitive and Calcium activated chloride channels. IUBMB Life 2014; 66:257-67; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/iub.1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pedemonte N, Galietta LJ. Structure and function of TMEM16 proteins (anoctamins). Physiol Rev 2014; 94:419-59; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00039.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Picollo A, Malvezzi M, Accardi A. TMEM16 proteins: unknown structure and confusing functions. J Mol Biol 2015; 427:94-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wanitchakool P, Wolf L, Koehl GE, Sirianant L, Schreiber R, Kulkarni S, Duvvuri U, Kunzelmann K. Role of anoctamins in cancer and apoptosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2014; 369:20130096; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rstb.2013.0096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Xiao Q, Yu K, Perez-Cornejo P, Cui Y, Arreola J, Hartzell HC. Voltage- and calcium-dependent gating of TMEM16A/Ano1 chloride channels are physically coupled by the first intracellular loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108:8891-6; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1102147108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sauter DR, Novak I, Pedersen SF, Larsen EH, Hoffmann EK. ANO1 (TMEM16A) in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Pflugers Arch 2014; 467:1495-508; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00424-014-1598-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]