Abstract

Objectives:

Schools are an important setting to enable and promote physical activity. Researchers have created a variety of tools to perform objective environmental assessments (or ‘audits') of other settings, such as neighborhoods and parks; yet, methods to assess the school physical activity environment are less common. The purpose of this study is to describe the approach used to objectively measure the school physical activity environment across 12 countries representing all inhabited continents, and to report on the reliability and feasibility of this methodology across these diverse settings.

Methods:

The International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE) school audit tool (ISAT) data collection required an in-depth training (including field practice and certification) and was facilitated by various supporting materials. Certified data collectors used the ISAT to assess the environment of all schools enrolled in ISCOLE. Sites completed a reliability audit (simultaneous audits by two independent, certified data collectors) for a minimum of two schools or at least 5% of their school sample. Item-level agreement between data collectors was assessed with both the kappa statistic and percent agreement. Inter-rater reliability of school summary scores was measured using the intraclass correlation coefficient.

Results:

Across the 12 sites, 256 schools participated in ISCOLE. Reliability audits were conducted at 53 schools (20.7% of the sample). For the assessed environmental features, inter-rater reliability (kappa) ranged from 0.37 to 0.96; 18 items (42%) were assessed with almost perfect reliability (κ=0.80–0.96), and a further 24 items (56%) were assessed with substantial reliability (κ=0.61–0.79). Likewise, scores that summarized a school's support for physical activity were highly reliable, with the exception of scores assessing aesthetics and perceived suitability of the school grounds for sport, informal games and general play.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that the ISAT can be used to conduct reliable objective audits of the school physical activity environment across diverse, international school settings.

Introduction

Childhood obesity is an escalating global epidemic that concerns public health professionals worldwide.1, 2 Although levels of childhood overweight and obesity initially increased predominantly in high-income countries, the prevalence is currently growing fastest in lower- and middle-income countries.3 Obesity results from an imbalance in energy expenditure (primarily physical activity) and energy intake (food ingested); therefore, current efforts to prevent obesity focus on promoting higher levels of physical activity and/or healthier diets.4, 5

Because of the large amount of time children spend in schools, schools have been identified as an important setting to enable and promote physical activity and healthy eating.4, 6, 7, 8, 9 Current global strategies recommend enhancing schools' support for physical activity and a healthy diet through changes to their built, or physical, environments. The school built environment can be measured using surveys or objective methods to identify features that influence these behaviors.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Although surveys of school personnel are arguably easier to employ and are currently included as a component of several studies,18 they can be burdensome for school staff, which may result in incomplete data, and may be subject to biased and/or incomplete reporting of school amenities. Objective assessments (often termed as ‘audits') of the school built environment by study staff, on the other hand, pose little-to-no burden on school personnel and result in complete and verified data for all schools. These objective audits, however, are limited by the consistency with which the study data collectors assess the availability and quality of features of the school environment.19

Researchers have created a variety of tools to perform objective environmental audits of other settings, such as neighborhoods and parks; however, methods to assess the school environment are less common.19, 20 To date, the only published reports of audits of the school environment come from two studies, both in developed countries (the United States and the United Kingdom). The International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE) targeted schools in its sampling scheme, and study staff completed an environmental audit of each participating school.21 The purpose of this paper is to describe the feasibility of using a single instrument (the ISCOLE school audit tool, or ISAT) to objectively assess the physical activity environment in schools from 12 countries representing widely ranging levels of development and to report on the reliability of this methodology across these diverse settings, to inform future global work to promote healthy school environments.

Materials and methods

The International Study Of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment

ISCOLE collected data on obesity, physical activity, dietary patterns and other lifestyle behaviors in 7341 9–11-year-old children across 12 urban/suburban study sites.21 Each ISCOLE study site was responsible for recruiting and enrolling at least 500 children, and the primary sampling frame was schools, which was typically stratified by an indicator of socioeconomic status to maximize variability within sites.21 The Institutional Review Board at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center (coordinating center) approved the overarching ISCOLE protocol, and the Institutional/Ethical Review Boards at each participating institution also approved the local protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, and child assent was obtained as required by local Institutional/Ethical Review Boards. Further details on the study methods are available in the Supplementary Materials and elsewhere.21 Data were collected from September 2011 to December 2013.

Development of the ISAT

The ISAT (see Supplementary Table 1: ISCOLE school audit tool (ISAT)) measured the following aspects of the school environment linked to physical activity: support for active transportation; sports and play facility provision; other facility provision (for example, benches and drinking fountains); aesthetics; and perceived suitability of the school grounds for sport, informal games, and general play. The component of the ISAT addressing the school built environment was largely based on the school audit tool used in the SPEEDY (Sport, Physical activity and Eating behavior: Environmental Determinants in Young people) study.10, 11 However, in some cases, response categories were altered in an attempt to reduce potential subjectivity, and items were changed or added based on feedback from site investigators. For example, an item to assess the presence of a vegetable garden was added. Finally, the wording of choices, including examples of environmental features (for example, ‘sidewalk' versus ‘footpath') and customary food items, were adapted to colloquial language and understanding as necessary across ISCOLE sites.

Training of ISAT data collectors

Site principal investigators and key study staff were trained (and ultimately certified) in a series of regional training sessions conducted by the ISCOLE Coordinating Center in advance of data collection at each study site. Before the training, site personnel were expected to review all training materials and to successfully pass an on-line examination designed to assess practical understanding of the ISAT protocol and methods. Training sessions were conducted by experts and tool developers from the ISCOLE Coordinating Center and incorporated a thorough review of the school audit protocol and methodology (see Supplementary Table 2: ISAT manual of procedures). Participants were encouraged to ask questions and initiate discussion to enhance clarification. In addition, trainees conducted a school audit at a nearby school as a hands-on field-based training exercise and case study. School audit data collectors were certified only after (1) completing on-line modules, (2) attending and participating during all modules of the training, and (3) successfully completing the training school audit (evaluated by achievement of satisfactory percent agreement on all measures relative to the expert who conducted the training). Satisfactory agreement was defined as at least 89% agreement with the certifier on each of the five sections of the ISAT.

ISAT-supporting materials

The ISCOLE Coordinating Center developed materials and resources to support the school audit and to assist with quality control of the data collected.

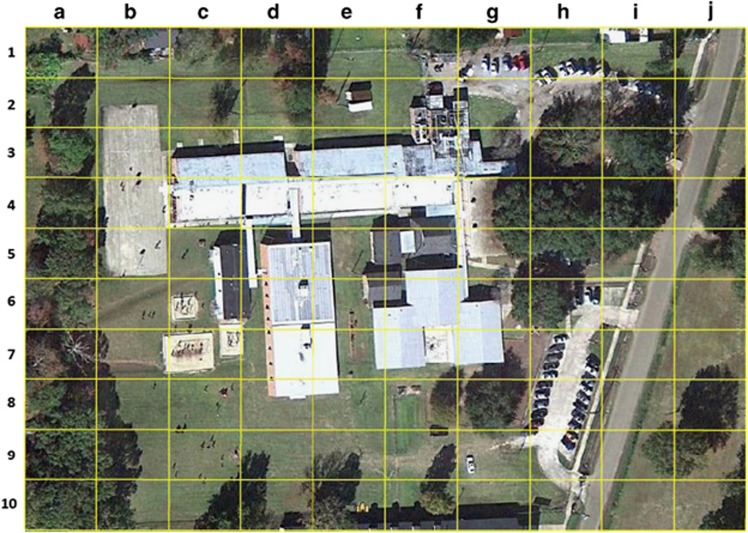

School aerial image and grid

To facilitate systematic completion of the ISAT, the ISCOLE Coordinating Center required that sites obtain an aerial image of each study school's entire school grounds (for example, from Google Earth) and overlay a predesigned 10 × 10 grid with labels ‘A–J' on the x axis and ‘1–10' on the y axis (see Figure 1 for an example). Data collectors were instructed to visit each grid square within the school grounds map and mark each as completed after the area was completely investigated. The map also served to allow data collectors to indicate location-specific data regarding features of the built environment, such as the location of entrances to the school.

Figure 1.

Aerial image of participating ISCOLE school with grid overlay.

ISAT worksheet

The school audit worksheet (see Supplementary Table 3: ISAT worksheet) was used by the data collectors to write down the grid locations where specific school audit items were located. After visiting all areas of the school grounds, the data collectors completed the ISAT based on the notes recorded on the school audit worksheet.

ISAT questions sheet

During one of the early trainings, site personnel recommended that a ‘questions sheet' be developed to assist school audit data collectors to record any questions arising during the audit (for example, how a certain area is used) that would require clarification with school personnel. School audit data collectors used the ISAT questions sheet to record such questions and to follow-up with the school's contact person or the ISCOLE Coordinating Center after the audit.

ISAT specific item dictionary

Each item in the school audit was defined in a document titled the ‘Specific Item Dictionary' (see Supplementary Table 4: ISAT specific item dictionary). The definitions were developed by the ISCOLE Coordinating Center and a new version of the dictionary was uploaded to the data management website if an item definition was altered or updated. The dictionary also included tips and quality control suggestions to reduce ambiguity of the item definitions and facilitate efficiency of school audit data collection.

ISAT photodictionary

A photodictionary served as a pictorial resource to provide additional clarification for school audit items (see Figure 2 for an example). The photodictionary was available to all study sites via the ISCOLE data management website, and sites were encouraged to submit additional photos. Pictures in the photodictionary displayed examples of real-world scenarios within the built environment that would or would not be counted for particular school audit items.

Figure 2.

Example page from ISAT photodictionary.

ISAT forum

The ISCOLE data management website included a virtual/web-based forum for ISAT data collectors to post questions and pictures if they were uncertain whether and/or how to properly account for the feature or item definition in question. The Coordinating Center experts, as well as other sites' school audit data collectors, were expected to actively participate in forum discussions and ultimately come to a consensus about the decision proposed for each question posted on the forum.

Timing of ISAT data collection

ISCOLE data collection occurred during the school year and covered all spanned seasons. ISAT data collection for a particular school occurred at the same time as the other ISCOLE data collection at that school, which ensured that the ISAT provided information on the school conditions concurrent with the accelerometry.

Assessing reliability of ISAT items

For each ISCOLE site, a minimum of two schools or 5% of their school sample was simultaneously and independently audited by two certified data collectors to assess inter-rater reliability of school audit items, as well as to identify any local quality control issues related to data collection. In 10 of the 12 ISCOLE sites, the schools associated with the reliability audits were the first two schools at which ISCOLE data collection occurred. In the other two ISCOLE sites (that is, the United States and Colombia), reliability audits were performed for 67% and 95% of schools, respectively, with the reliability audit being determined by the availability of a second data collector and the objectives of the ISCOLE site.

Statistical analysis

The ISAT collected information about availability and, in some cases, quality of various school amenities. For analysis, responses were dichotomized to correspond to ‘present and functional' versus ‘present and not functional or not available.'

Item-level agreement between data collectors was assessed with both the kappa statistic and percent agreement. Because of the multilevel nature of the data, the kappa statistic was calculated using a regression technique,22 in which the regression models incorporated random effects corresponding to the ISCOLE sites. Level of agreement was evaluated as follows based on the value of the kappa statistic:23 almost perfect (κ=0.80–1.00), substantial (κ=0.60–0.79), moderate (κ=0.40–0.59), fair (κ=0.20–0.39) and slight (κ=0–0.19). Percent agreement was calculated as a weighted average that gave equal weight to each study site (that is, the two sites that conducted reliability audits in more than two schools were not over-represented in the measure).

The results of the audit were also summarized as scores corresponding to the domains assessed by the ISAT: support for walking to school; support for biking to school; provision of sports and play facilities; provision of other features supporting physical activity; aesthetics; and perceived suitability of the school grounds for sport, informal games and general play. Each component score was calculated as the sum of the items within each domain, with the following exceptions where two items measured separately were treated as a single item in the component score: having an entrance accessible/designed for pedestrians/cyclists (neither=0, accessible but not designed for=0.5, designed for=1), pavements (that is, sidewalks/footpaths) on one/both sides of the street (neither=0, one side=0.5, both=1), bicycle lanes on/separated from the road (neither=0, on road=0.5, separated from the road=1) and uncovered/covered bicycle parking (neither=0, uncovered=0.5, covered=1). For component scores, reliability was summarized as the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; and associated 95% confidence interval), which was calculated within an analysis of variance framework as the ratio of the difference between the between-school variation and the within-school (inter-rater) variation and the sum of the variance components.24 The ICC was summarized separately for those ISCOLE sites performing reliability audits on the minimum of two schools within the site-specific sample and those sites that performed reliability audits on the majority of their school samples. Agreement for the component scores was evaluated as follows based on the value of the ICC:25 excellent (ICC 0.80–1.00), good (ICC 0.60–0.79), fair (ICC 0.40–0.59) and poor (ICC 0–0.39). All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Across the 12 sites, 256 schools were audited as part of the ISCOLE study. Except for the China and India sites, which enrolled 6 and 10 schools, respectively, each site enrolled 24 schools on average. Reliability audits were conducted in 53 schools (21% of the school sample). By site, this ranged from 7 to 95% of schools.

Although the ISCOLE study targeted 10-year-old children, the school settings for these children were variable within and across sites (Table 1). Schools contained 3–16 grade levels, and the number of children enrolled in the participating school ranged from 50 to 5200.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of schools participating in ISCOLE.

| Country (site) | N (schools) | N (reliability schools) | No. of days per year students attend school, mean (s.d.) | No. of students per school, mean (s.d.) (range) |

No. of grades at school (%) |

No. of students per grade, mean (s.d.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–6 | 7–8 | 9–16 | ||||||

| Australia (Adelaide) | 26 | 2 | 195.3 (4.4) | 404.5 (308.0) (50–1200) | 81 | 19 | 43.8 (27.1) | |

| Brazil (Sao Paulo) | 24 | 2 | 200.3 (1.2) | 717.7 (572.0) (136–2900) | 21 | 29 | 50 | 85.5 (46.7) |

| Canada (Ottawa) | 26 | 2 | 190.8 (5.5) | 388.7 (191.8) (165–894) | 81 | 19 | 50.0 (21.3) | |

| China (Tianjin) | 6 | 2 | 195.8 (9.2) | 1660.3 (820.8) (700–2900) | 100 | 276.7 (136.8) | ||

| Colombia (Bogota) | 20 | 19 | 197.8 (7.3) | 1572.8 (825.0) (441–3400] | 100 | 127.2 (67.5) | ||

| Finland (Helsinki, Espoo and Vantaa) | 25 | 2 | 190.0 (7.6) | 426.3 (142.1) (172–760) | 68 | 4 | 28 | 62.2 (18.3) |

| India (Bangalore) | 10 | 2 | 215.5 (43.2) | 1860.0 (1464.4) (440–5200) | 10 | 90 | 140.6 (98.6) | |

| Kenya (Nairobi) | 29 | 2 | 193.1 (38.2) | 865.2 (511.1) (120–1800) | 10 | 21 | 69 | 103.4 (62.1) |

| Portugal (Porto) | 23 | 2 | 165.7 (13.9) | 781.5 (309.1) (239–1598) | 56 | 35 | 9 | 127.1 (55.4) |

| South Africa (Cape Town) | 20 | 2 | 203.4 (4.8) | 822.5 (326.5) (320–1350) | 5 | 80 | 15 | 107.3 (53.1) |

| United Kingdom (Bath and NE Somerset) | 26 | 2 | 190.5 (4.5) | 293.1 (141.6) (90–720) | 19 | 81 | 46.9 (31.4) | |

| United States (Baton Rouge) | 21 | 14 | 179.2 (1.7) | 620.5 (300.2) (235–1374) | 76 | 24 | 74.2 (25.1) | |

Likewise, the availability of school features supportive of physical activity differed both across sites, and across schools within a site (Table 2). However, some items (for example, availability of pedestrian entrances, presence of planted beds and assessed suitability of the school grounds for general play) showed little variability both within and between countries, with these features being present in over 90% of schools in the sample and in over 71% of each of the site-specific samples. Other items, such as the availability of running tracks, varied considerably between sites, but relatively little between schools within a site. Across the school features assessed, only six varied across all site-specific samples (bicycle parking, school warning signs, trees for sitting under, wildlife/nature gardens, murals/outdoor art and ambient noise).

Table 2. Availability of school features related to opportunities for physical activity.

| Overall (%) | Australia (%) | Brazil (%) | Canada (%) | China (%) | Colombia (%) | Finland (%) | India (%) | Kenya (%) | Portugal (%) | South Africa (%) | UK (%) | USA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking provision | |||||||||||||

| Has entrance designed for pedestriansa | 97 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 100 | 71 |

| Pavementsa | 87 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 83 | 95 | 100 | 60 | 31 | 96 | 90 | 100 | 81 |

| Marked pedestrian crossingsa | 64 | 81 | 88 | 69 | 50 | 45 | 100 | 50 | 7 | 96 | 85 | 23 | 76 |

| Traffic calminga | 41 | 50 | 29 | 35 | 0 | 45 | 72 | 60 | 31 | 57 | 40 | 38 | 10 |

| School warning signsa | 65 | 92 | 75 | 96 | 50 | 65 | 80 | 60 | 10 | 48 | 30 | 69 | 95 |

| Road safety signsa,b | 39 | 92 | 54 | 77 | 50 | 0 | 36 | 70 | 3 | 9 | 30 | 19 | 52 |

| Cycling provision | |||||||||||||

| Has entrance designed for cyclistsa | 51 | 62 | 29 | 8 | 100 | 50 | 76 | 100 | 3 | 87 | 5 | 96 | 67 |

| Cycle lanes separated from the roada | 19 | 38 | 4 | 4 | 67 | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 5 |

| Pavementsa | 87 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 83 | 95 | 100 | 60 | 31 | 96 | 90 | 100 | 81 |

| Marked pedestrian crossingsa | 64 | 81 | 88 | 69 | 50 | 45 | 100 | 50 | 7 | 96 | 85 | 23 | 76 |

| Traffic calminga | 41 | 50 | 29 | 35 | 0 | 45 | 72 | 60 | 31 | 57 | 40 | 38 | 10 |

| School warning signsa | 65 | 92 | 75 | 96 | 50 | 65 | 80 | 60 | 10 | 48 | 30 | 69 | 95 |

| Road safety signsa | 39 | 92 | 54 | 77 | 50 | 0 | 36 | 70 | 3 | 9 | 30 | 19 | 52 |

| Route signs for cyclistsa | 16% | 8 | 8 | 23 | 0 | 5 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 12 | 19 |

| Cycle parkingc | 49 | 96 | 8 | 46 | 17 | 35 | 84 | 50 | 3 | 61 | 20 | 85 | 57 |

| Sports and play facilities | |||||||||||||

| Bright markings on play surfacesd | 52 | 92 | 54 | 54 | 17 | 35 | 56 | 0 | 24 | 48 | 30 | 92 | 57 |

| Playground equipmentc | 59 | 100 | 38 | 42 | 33 | 40 | 100 | 60 | 45 | 0 | 90 | 42 | 100 |

| Outdoor sports fieldsd | 60 | 77 | 4 | 23 | 100 | 25 | 64 | 100 | 97 | 91 | 50 | 73 | 52 |

| Running trackd | 19 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 8 | 100 | 0 | 91 | 0 | 15 | 5 |

| Paved courts for sportd | 68 | 100 | 100 | 23 | 67 | 85 | 24 | 100 | 28 | 91 | 70 | 88 | 71 |

| Assault course/fitness coursed | 16 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 33 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 88 | 24 |

| Outdoor paved aread | 84 | 100 | 75 | 73 | 17 | 95 | 64 | 100 | 66 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 95 |

| Grassy/soft surface play aread | 73 | 100 | 17 | 69 | 0 | 65 | 84 | 100 | 100 | 35 | 70 | 92 | 100 |

| Other facility provision | |||||||||||||

| Benchesc | 79 | 100 | 83 | 77 | 50 | 75 | 95 | 90 | 41 | 100 | 35 | 100 | 90 |

| Picnic tablesc | 45 | 96 | 96 | 35 | 17 | 15 | 21 | 0 | 7 | 22 | 20 | 88 | 67 |

| Drinking fountainsc | 59 | 100 | 96 | 0 | 50 | 5 | 60 | 100 | 62 | 65 | 60 | 31 | 95 |

| Wildlife/nature gardensd | 30 | 35 | 54 | 4 | 50 | 5 | 4 | 50 | 24 | 78 | 5 | 46 | 33 |

| Vegetable gardensd | 39 | 73 | 17 | 8 | 0 | 25 | 4 | 20 | 55 | 74 | 25 | 73 | 43 |

| Aesthetics | |||||||||||||

| Planted bedse | 91 | 100 | 75 | 81 | 100 | 90 | 88 | 100 | 93 | 100 | 95 | 96 | 90 |

| Trees for sitting undere | 74 | 96 | 46 | 85 | 67 | 55 | 16 | 90 | 83 | 87 | 80 | 96 | 90 |

| Ambient noisee | 25 | 27 | 8 | 31 | 33 | 60 | 24 | 20 | 28 | 43 | 5 | 8 | 19 |

| Littere | 34 | 19 | 25 | 19 | 0 | 15 | 48 | 30 | 41 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 57 |

| Murals/outdoor arte | 62 | 81 | 88 | 35 | 50 | 70 | 32 | 60 | 62 | 65 | 60 | 81 | 48 |

| Graffitie | 21 | 12 | 13 | 38 | 0 | 60 | 32 | 60 | 3 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Suitability of school grounds | |||||||||||||

| For sportf | 83 | 100 | 92 | 38 | 100 | 95 | 88 | 80 | 97 | 87 | 60 | 85 | 81 |

| For informal gamesf | 91 | 100 | 83 | 73 | 50 | 90 | 100 | 80 | 97 | 96 | 95 | 100 | 95 |

| For general playf | 96 | 100 | 92 | 77 | 83 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Response categories for items:

Yes/no.

Road safety signs did not include normal traffic signs like stop signs.

Assessed as number of examples, overall quality of features (1=entirely or almost entirely broken down and non-functional to 5=100% or almost 100% functional) or not available; recoded for analysis as present and functional (that is, number of examples >0 and quality >1) versus present and non-functional.

Assessed as present and functional, present and non-functional or not available; recoded for analysis as present and functional (1) versus present and non-functional or not available (0).

Assessed as none versus some/a lot.

Assessed as not at all versus somewhat/very.

Of the 43 items comprising a school's physical activity environment, 18 items (42%) were assessed with almost perfect reliability (κ=0.80–0.96), and a further 24 items (56%) were assessed with substantial reliability (κ=0.61–0.79; that is, a total of 98% of items had substantial to almost perfect reliability; Table 3). Only one item (suitability of school grounds for general play) was not reliably assessed (K=0.37). Across all items, percent agreement between the two local data collectors ranged from 83.9 to 100%.

Table 3. ISAT inter-rater reliability.

| School grounds component/item | Kappa | Agreement (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Walking provision | ||

| Has entrance accessible for pedestrians | 0.66 | 99.4 |

| Has entrance designed for pedestrians | 0.75 | 98.8 |

| Pavements on one side of the street | 0.92 | 99.1 |

| Pavements on both sides of the street | 0.93 | 99.1 |

| Marked pedestrian crossings | 0.77 | 93.3 |

| Traffic calming | 0.72 | 92.7 |

| School warning signs | 0.69 | 85.6 |

| Road safety signs | 0.61 | 83.9 |

| Cycling provision | ||

| Has entrance accessible for cyclists | 0.67 | 90.6 |

| Has entrance designed for cyclist use | 0.74 | 96.3 |

| Cycle lanes on the road | 0.79 | 99.4 |

| Cycle lanes separated from the road | 0.80 | 100.0 |

| Pavements on one side of the road | 0.92 | 99.1 |

| Pavements on both sides of the road | 0.93 | 99.1 |

| Marked pedestrian crossings | 0.77 | 93.3 |

| Traffic calming | 0.72 | 92.7 |

| School warning signs | 0.69 | 85.6 |

| Road safety signs | 0.61 | 83.9 |

| Route signs for cyclists | 0.83 | 95.2 |

| Covered cycle parking | 0.91 | 100.0 |

| Uncovered cycle parking | 0.91 | 100.0 |

| Sports and play facilities | ||

| Bright markings on play surfaces | 0.89 | 94.6 |

| Playground equipment | 0.82 | 91.2 |

| Outdoor sports fields | 0.79 | 90.0 |

| Running track | 0.87 | 99.4 |

| Paved courts for sport | 0.63 | 89.0 |

| Assault course/fitness course | 0.94 | 99.6 |

| Outdoor paved area | 0.85 | 99.6 |

| Grassy/soft surface play area | 0.78 | 94.5 |

| Other facility provision | ||

| Benches | 0.96 | 95.8 |

| Picnic tables | 0.96 | 100.0 |

| Drinking fountains | 0.91 | 95.8 |

| Wildlife/nature gardens | 0.82 | 94.6 |

| Vegetable gardens | 0.96 | 99.4 |

| Aesthetics | ||

| Planted beds | 0.64 | 98.4 |

| Trees for sitting under | 0.64 | 94.2 |

| Ambient noise | 0.64 | 93.1 |

| Litter | 0.70 | 91.8 |

| Murals/outdoor art | 0.63 | 84.2 |

| Graffiti | 0.69 | 92.7 |

| Suitability of school grounds | ||

| For sport | 0.61 | 93.3 |

| For informal games | 0.66 | 98.7 |

| For general play | 0.37 | 95.0 |

Abbreviation: ISAT, ISCOLE school audit tool.

Reliability was good to excellent for scores corresponding to the following domains assessed by the ISAT: support for walking to school, support for biking to school, provision of sports and play facility and provision of other features supporting physical activity (Table 4). Although the reliability of the scores for aesthetics and perceived suitability of the school grounds was excellent across the 10 ISCOLE sites that performed reliability audits in two schools, the reliability for these schools was lower in the two ISCOLE sites that performed reliability audits in the majority of their schools.

Table 4. ISAT reliability of scores summarizing components of the school environment.

| School grounds factor or subscale | Mean (s.d.) (n=256)a | ICC (95% CI) (n=33)b | ICC (95% CI) (n=20)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Walking provision (6 items) | 3.9 (1.5) | 0.75 (0.56, 0.87) | 0.73 (0.38, 0.90) |

| Cycling provision (9 items) | 4.2 (2.0) | 0.83 (0.69, 0.91) | 0.87 (0.66, 0.95) |

| Sports and play facilities (8 items) | 4.3 (1.7) | 0.86 (0.74, 0.93) | 0.82 (0.55, 0.93) |

| Other facility provision (5 items) | 2.5 (1.4) | 0.97 (0.94, 0.98) | 0.93 (0.81, 0.98) |

| Aesthetics (6 items) | 3.1 (1.1) | 0.46 (0.15, 0.69) | 0.88 (0.69, 0.96) |

| Suitability of school grounds (3 items) | 2.7 (0.7) | 0.35 (0.02, 0.61) | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; ISAT, ISCOLE school audit tool; ISCOLE, International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment.

Mean (s.d.) of component scores across entire ISCOLE school sample.

Reliability of component scores within the sample of reliability schools from two ISCOLE sites that performed reliability audits on the majority of schools in the sample.

Reliability of component scores within the sample of reliability schools from ten ISCOLE sites that performed reliability audits on two schools within each site-specific sample.

On average, school audits took 57 min to complete, ranging from 15 to 160 min. The time to complete the audit increased with the number of students at the school and declined over time (data not shown), presumably as data collectors became more familiar with the method. For example, for an average-sized school, a site's first school audit took an average of 61 min to complete, whereas a school audit completed 6 months later took an average of 51 min to complete.

Discussion

This study supports that it is possible to conduct reliable objective audits across international settings of features of the school built environment related to physical activity. Nearly all features of the school environment were assessed with high reliability. Likewise, scores that summarized a school's support for physical activity were highly reliable, with the exception of scores assessing aesthetics and perceived suitability of the school grounds for sport, informal games and general play.

Our results are similar to those of two other studies that have reported on the development of school audit tools. Jones et al.11 tested the reliability of the SPEEDY instrument in 17 schools in Norfolk, UK, and Lee et al.16 assessed reliability of the Texas Childhood Obesity Prevention Policy Evaluation (TCOPPE) instrument in 12 schools in Texas, USA. Both studies report moderate to excellent reliability for items, with the exception of items measured with ordinal (Likert) responses and those requiring data collectors to subjectively rate their perceptions (for example, attractiveness and quality).

A unique feature of this study is the diversity of school settings in which the ISAT was used; to our knowledge, this is the first study to conduct objective audits of the school environment in less-developed countries. A further strength of this study is the large sample size of schools that contributed to the reliability estimates. Prior studies11, 16 noted low variability in some measures, which limited assessment of reliability. In contrast, because the current study assessed school environments across widely different settings, all items showed some variability, whether within or between sites. However, the current study is limited by the fact that inter-rater reliability of school audit items was the only reliability measure evaluated. Lee et al.16 also measured test–retest reliability to assess the stability of the item measures over time and reported good-to-outstanding test–retest reliability in their use of the TCOPPE instrument in Texas schools. Although not investigated formally within ISCOLE, feedback from ISCOLE data collectors suggests that in countries with high seasonal variation, test–retest reliability for particular audit items measured across seasons would likely be low. For example, in a country with high amounts of winter snow accumulation, a feature such as the presence of bright marking on play surfaces could be assessed as ‘functional' some of the year; however, a data collector would be unable to determine its presence if covered by snow, and would therefore consider it ‘not present.' Similarly, there may be features present during winter, such as snow hills, that are not present during other seasons. Measures derived from a school audit are generally used in two ways: to summarize the overall healthfulness of a school's environment (for example, the number of features supportive of physical activity that the school provides its students), and to provide objective measures of the school environment against which concurrent levels of student physical activity can be evaluated for associations. In situations such as the examples provided above, a single point-in-time audit may not suffice for both intended uses if high seasonal variability occurs across the measurement of participating schools. An additional limitation of the current study is the fact that the reliability schools were generally the first two participating schools. This approach was chosen so that potential measurement issues could be identified and resolved early in the data collection process; however, because the reliability audits occurred most proximate to the training, this may have biased reliability estimates upward. If, on the other hand, reliability improves with time and experience, then these estimates may be considered conservative. Within the two sites with more than two reliability audits, there was no evidence of drift, or a decline in consistency over time, between the two data collectors (data not shown).

The current study did not assess relationships between in-school physical activity and the assessed features. The SPEEDY instrument on which the ISAT was based showed good construct validity, however, being able to differentiate the most supportive and least supportive schools on the basis of child physical activity levels. Besides construct validity, the amount of variability in an item, or component, affects the relationship with physical activity. In the current study, the availability of school features supportive of physical activity differed both across sites, and across schools within a site, and several items showed little within-site variability. Therefore, it is likely that the relationships between specific features of the school environment and in-school physical activity may differ across countries.

ISCOLE used several strategies to promote high reliability: data collectors were required to be certified after completing a rigorous training, the audit was supported by the availability of specific item definitions and a photodictionary to reduce ambiguity or subjectivity in scoring of features, data collectors used a school map and grid to facilitate a systematic approach to the audit, and a forum was available that encouraged questions and discussions about situations requiring clarification. Despite differences in local expertize and resources, all ISCOLE sites were able to conduct the school audit according to protocol. This success suggests that the ISAT is feasible to include in future research on child health, and the ISAT results for the 12 sites represented in ISCOLE provide a valuable benchmark for this future work.

Conclusions

The ISAT is the first instrument to objectively assess the physical activity environment in a global sample of schools. The ISAT is feasible to implement across diverse, international settings and provides reliable information about aspects of the school environment thought to be supportive of physical activity. The availability of a single audit instrument suitable for the use in schools around the world can facilitate global work to promote healthy school environments. Future research will evaluate associations between measures derived from the school audit and children's in-school physical activity.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the ISCOLE External Advisory Board and the ISCOLE participants and their families who made this study possible. A membership list of the ISCOLE Research Group and External Advisory Board is included in Katzmarzyk et al. (this Issue). ISCOLE was funded by The Coca-Cola Company. MF has received a research grant from Fazer Finland. AK has been a member of the Advisory Boards of Dupont and McCain Foods. RK has received a research grant from Abbott Nutrition Research and Development. VM is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Actigraph.

MF has received an honorarium for speaking for Merck. VM has received an honorarium for speaking for The Coca-Cola Company. TO has received an honorarium for speaking for The Coca-Cola Company. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity Supplements website (http://www.nature.com/ijosup)

Supplementary Material

References

- Karnik S, Kanekar A. Childhood obesity: a global public health crisis. Int J Prev Med 2012; 3: 1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; 164. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman A. World Health Assembly. WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Food Nutr Bull 2004; 25: 292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Interventions on Diet and Physical Activity: What Works: Summary Report. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. School Policy Framework: Implementation of the WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Prioritizing Areas for Action in the Field of Population-based Prevention of Childhood Obesity: a Set of Tools for Member States to Determine and Identify Priority Areas for Action. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Story M, Nanney MS, Schwartz MB. Schools and obesity prevention: creating school environments and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Milbank Q 2009; 87: 71–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Sluijs EM, Skidmore PM, Mwanza K, Jones AP, Callaghan AM, Ekelund U et al. Physical activity and dietary behaviour in a population-based sample of British 10-year old children: the SPEEDY study (Sport, Physical activity and Eating behaviour: environmental Determinants in Young people). BMC Public Health 2008; 8: 388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NR, Jones A, van Sluijs EM, Panter J, Harrison F, Griffin SJ. School environments and physical activity: The development and testing of an audit tool. Health Place 2010; 16: 776–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle LA. Examining the etiology of childhood obesity: The IDEA study. Am J Community Psychol 2009; 44: 338–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Consortium for School Health. Healthy School Planner. 2012. Available at www.healthyschoolplanner.uwaterloo.ca (accessed on 8 July 2014).

- Cameron R, Manske S, Brown KS, Jolin MA, Murnaghan D, Lovato C. Integrating public health policy, practice, evaluation, surveillance, and research: the school health action planning and evaluation system. Am J Public Health 2007; 97: 648–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS). 2012. Available at www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/shpps/index.htm (accessed on 8 July 2014).

- Lee C, Kim HJ, Dowdy DM, Hoelscher DM, Ory MG. TCOPPE school environmental audit tool: assessing safety and walkability of school environments. J Phys Act Health 2013; 10: 949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan N, Wolfenden L, Morgan PJ, Bell AC, Barker D, Wiggers J. Validity of a self-report survey tool measuring the nutrition and physical activity environment of primary schools. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013; 10: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner K, Foster C, Allender S, Plugge E. A systematic review of how researchers characterize the school environment in determining its effect on student obesity. BMC Obesity 2015; 2: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, Sallis JF. Measuring the built environment for physical activity: state of the science. Am J Prev Med 2009; 36: S99–S123 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle LA. Measuring the food environment: state of the science. Am J Prev Med 2009; 36: S134–S144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmarzyk PT, Barreira TV, Broyles ST, Champagne CM, Chaput JP, Fogelholm M et al. The International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment (ISCOLE): design and methods. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz SR, Parzen M, Fitzmaurice GM, Klar N. A two-stage logistic regression model for analyzing inter-rater agreement. Psychometrika 2003; 68: 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Shara N. Reliability Analysis: Calculate and Compare Intra-class Correlation Coefficients (ICC) in SAS. NESUG: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess 1994; 6: 284–290. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.