Abstract

Iron-dependent oxidative DNA damage in vivo by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, HP) induces copious single-strand(ss)-breaks and base modifications. HP also causes infrequent double-strand DNA breaks, whose relationship to the cell killing is unclear. Since hydrogen peroxide only fragments chromosomes in growing cells, these double-strand breaks were thought to represent replication forks collapsed at direct or excision ss-breaks and to be fully reparable. We have recently reported that hydrogen peroxide kills Escherichia coli by inducing catastrophic chromosome fragmentation, while cyanide (CN) potentiates both the killing and fragmentation. Remarkably, the extreme density of CN+HP-induced chromosomal double-strand breaks makes involvement of replication forks unlikely. Here we show that this massive fragmentation is further amplified by inactivation of ss-break repair or base-excision repair, suggesting that unrepaired primary DNA lesions are directly converted into double-strand breaks. Indeed, blocking DNA replication lowers CN+HP-induced fragmentation only ~2-fold, without affecting the survival. Once cyanide is removed, recombinational repair in E. coli can mend several double-strand breaks, but cannot mend ~100 breaks spread over the entire chromosome. Therefore, double-strand breaks induced by oxidative damage happen at the sites of unrepaired primary one-strand DNA lesions, are independent of replication and are highly lethal, supporting the model of clustered ss-breaks at the sites of stable DNA-iron complexes.

Keywords: cyanide, hydrogen peroxide, catastrophic chromosome fragmentation, base excision repair, ss-break repair, recombinational repair

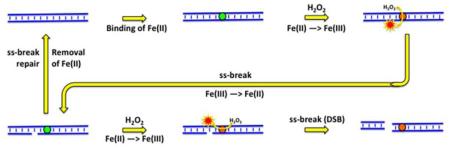

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, sometimes abbreviated as HP) is a potent life-specific oxidation agent, used by our immune cells to kill invading microbes [1, 2]. The general lack of reactivity of H2O2 outside the cell at physiological pH and temperatures [3-5] contrasts with its potent toxicity inside the cell, explained by the distribution of soluble ferrous iron (Fe(II)) between “life” and the surrounding “non-life”. Indeed, in oxic conditions, Fe(II) is generally absent outside the cell [6, 7], while plentiful (~1 mM total iron) inside the cell [8, 9]. According to the Fenton's reaction [10], ferrous iron donates electron to hydrogen peroxide, splitting the molecule in half and thus generating hydroxyl radical, which reacts with organic molecules at diffusion rates [5, 11].

However, because of the powerful cellular defense systems [12], H2O2 alone kills fast only at concentrations of 20 mM and higher [13-15], while typical in vivo concentrations of it even in lysosomes are orders of magnitude lower [16-18]. To make the physiological concentrations kill, cells of our immune system use various potentiator molecules that are only bacteriostatic by themselves, yet make low concentrations of H2O2 bactericidal. Perhaps the most widely recognized of such potentiators is nitric oxide [19-21], but several other potentiators are known, including aminoacids histidine and cysteine [22-24], and cyanide (CN) [15, 25]. In spite of years of research, the mechanisms behind potentiation of H2O2 toxicity remain elusive. The initial objective of our project was to test the idea that CN potentiates H2O2 toxicity by inactivating DNA repair mechanisms that mend various H2O2-induced DNA lesions. Cyanide could do it, for example, by extracting metal cofactors from certain enzymes or by blocking ATP production and thus stalling repair pathways requiring substantial energy consumption.

Hydrogen peroxide (via formation of hydroxyl radicals) induces a wide variety of DNA lesions. H2O2 treatment causes direct one-strand DNA breaks (ss-breaks), repaired in E. coli by DNA pol I plus DNA ligase (ss-break repair), a variety of modified sugars, as well as modified DNA bases, like hypoxanthine, 5,6-dihydrothymine, fapy-G and 8-oxo-G, that are removed by DNA glycosylases, with the resulting abasic sites incised by abasic site endonucleases (ABS-endo) and subsequent repair completed by the same DNA pol I and DNA ligase (base-excision repair) [26-28]. This diverse chemistry of DNA damage notwithstanding, at the end H2O2 either breaks individual DNA strands directly, or the modified sugars or bases are repaired via strand incision intermediates, both leading to accumulation of ss-breaks during cell treatment with H2O2 [29]. With all this H2O2 -induced ss-breaks, it is not surprising that some of them represent double-strand DNA breaks [23, 29, 30], the chromosome lesions of the highest killing potential [31-33]. In fact, there are proposals that the killing lesions after hydrogen peroxide treatment are these infrequent double-strand breaks [15, 23, 31, 34], rather than the copious oxidative one-strand DNA damage. The acute sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide of mutants in double-strand break repair [13, 14, 35] supports this suspicion.

The traditional explanation for these infrequent double-strand breaks would be stochastic coincidence of two direct/repair ss-breaks in the opposite DNA strands, according to the scenario called “clustered excision” [36-38] (Fig. 1A). However, aggravation of the repairable H2O2-induced DNA damage to the irreparable status is only observed in growing cells [15, 39], suggesting involvement of DNA replication or segregation in formation of double-strand DNA breaks. There are several models of replication-dependent chromosomal fragmentation [40, 41], but only one of them, the replication fork collapse model, features preexisting DNA ss-breaks. According to the replication fork collapse scenario [42-44], replication fork runs into a ss-break in template DNA and comes apart, generating a one-ended double-strand break and the full-length molecule (a hybrid between the template and one of the replicated daughter arms) (Fig. 1A). Finally, segregation in bacteria is suspected to break duplex DNA at unrepaired ss-breaks, in the double-strand break-behind the replication fork scenario [45] (Fig. 1A). The growth requirement for H2O2-induced double-strand breaks strongly favors either replication- or segregation-dependent scenarios for the chromosome fragmentation in H2O2-treated cells.

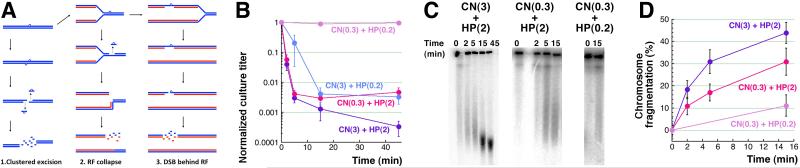

Fig. 1. Three levels of CN + H2O2-induced chromosomal fragmentation and their consequences for survival.

A. The three models of ss-break-mediated double-strand DNA breaks: 1) the clustered excision model of direct breaks; 2) the replication fork collapse model of replication-dependent breaks; 3) the “DSB-behind the fork” model of segregation-dependent breaks. Parental DNA strands are in blue, while the newly-synthesized DNA strands are in red.

B. Kinetics of death of WT cells treated with varying concentrations of either CN (3 or 0.3 mM) or H2O2 (2 or 0.2 mM). Here and in the rest of the paper, all values are means of 3 or more independent measurements ± SEM.

C. A representative pulsed-field gel demonstrating chromosomal fragmentation induced in WT cells treated with 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2, or 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2, or 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2.

D. Kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation upon treatment with 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2, or 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2, or 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 (from several gels like in “C”). Here and for the rest of the paper, fragmentation level at any time point is shown over the fragmentation level at time = 0.

While investigating mechanisms of cyanide-potentiated H2O2 toxicity in E. coli, we have recently reported a novel phenomenon, that we have called “catastrophic chromosome fragmentation” [15]. We have found that chromosomes in the treated cells were literally pulverized, leaving no chance of survival, but in wild type (WT) E. coli fragmentation only affected growing cells [15]. Then we also found that in the dps mutants, H2O2-induced fragmentation is still observed in stationary cultures [15]. This surprising result meant that replication forks per se are not required for H2O2-induced chromosome fragmentation and opened a possibility that even in growing cells, H2O2-induced double-strand breaks have a non-replicative nature. Another aspect of H2O2-induced chromosomal fragmentation that begged further investigation was its massive nature (thus, the term “catastrophic chromosome fragmentation”) [15], which was intuitively inconsistent with the replication- or segregation-dependence of the breakage. To explore mechanisms behind this catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation, and their potentiation by cyanide, we sought answers to three major questions: 1) what is the role of various DNA repair mechanisms in preventing or mending this fragmentation? 2) what is the effect of cyanide on the fragmentation or its repair? 3) are double-strand breaks dependent on replication or protein synthesis?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Plasmids

Escherichia coli strains used are listed in Table 1 and are all K-12 BW25113 derivatives [46], except for dnaA46, dnaC2 and dut recBC(Ts), which are in the AB1157 background. Alleles were moved between strains by P1 transduction [47]. Unless indicated otherwise, the mutants were all deletions from the Keio collection [46], purchased from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center, and were verified by PCR or by their characteristic UV-sensitivities. For double mutant construction, the resident kanamycin-resistance cassette was first removed by transforming the strain with pCP20 plasmid [48].

Table 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids (all strains are in the BW25113 background unless indicated otherwise).

| Strain name | Relevant Genotype | Source/ CGSC# or Construction |

|---|---|---|

| AB1157 | F− λ−

rac- thi-1 hisG4 Δ(gpt-proA)62 argE3 thr-1 leuB6 kdgK51 rfbD1 araC14 lacY1 galK2 xylA5 mtl-1 tsx-33 glnV44 rpsL31. |

[87] |

| L-216 | AB1157 dnaA46(Ts) [88] lac/CE-ori::bla | Elena Kouzminova |

| L-393 | AB1157 dnaC2 (Ts) [64] | 10827 |

| AK4 | AB1157 Δ(srlR-recA306)::Tn10 | [89] |

| JB1 | AB1157 ΔrecBCD3::kan | [90] |

| N2731 | AB1157 recG258::Tn10 | [91] |

| JJC754 | AB1157 ΔruvABC232::cat | [92] |

| AK25 | AB1157 polA12(Ts)(Tn10) | Lab Collection |

| GR501 |

Hfr(PO45), λ, ligA251(ts), relA1, spoT1, thi

E1 |

6087 |

| LA20 | GR501 ligA251 ΔypeB::kan | [93] |

| SX1253 | F-, Δ(argF-lac)169, gal-490, Δ(modF- ybhJ) 803, λ[cI857 Δ(cro-bioA)], xthA791- YFP(::cat), IN(rrnD-rrnE)1, rph-1 |

12808 |

| BW535 | F-, thr-1, araC14, leuB6(Am), Δ(gpt- proA) 62, lacY1, tsx-33, glnX44(AS), galK2(Oc), λ−, Rac-0, nth- 1::kan,ble, Δ(xthA- pncA) 90, hisG4(Oc), rfbC1, mgl-51, nfo- 1::kan, rpsL31(strR),kdgK51, xylA5, mtl- 1, argE3(Oc), thiE1 |

7047 |

| N3055 | F-, λ−, IN(rrnD-rrnE)1, rph- 1, uvrA277::Tn10 |

6661 |

| JW0762-2 | ΔuvrB751::kan | 8819 |

| BW25113 | F-, Δ(araD-araB)567, ΔlacZ4787(::rrnB- 3), λ−, rph-1, Δ(rhaD-rhaB)568, hsdR514 |

[46] |

| TM21 | Δ(srlR-recA306)::Tn10 | BW25113 × P1 AK4 |

| TM22 | ΔrecBCD3::kan | BW25113 × P1 JB1 |

| TM23 | ΔruvABC232::cat | BW25113 × P1 JJC754 |

| TM24 | recG258::Tn10 ΔruvABC232::cat | TM23 × P1 N2731 |

| TM25 | xthA791-YFP(::cat) | BW25113 × P1 SX1253 |

| TM26 | xthA791-YFP(::cat) nfo-1::kan | TM25 × P1 BW535 |

| TM 27 | ligA251 ΔypeB::kan | BW25113 × P1 LA20 |

| TM 28 | polA12(Ts) (Tn10) | BW25113 × P1 AK25 |

| TM 29 | uvrA277::Tn10 | BW25113 × P1 N3055 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCP20 | Flp recombinase gene on a temperature- sensitive replicon |

[48] |

2.2. Reagents

Hydrogen peroxide was purchased from Sigma; potassium cyanide (KCN) was from Mallinckrodt.

2.3. Growth Conditions and Viability Assay

To quantify survival kinetics, fresh overnight cultures were diluted 500-fold into LB medium (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl, 250 μl of 4 M NaOH per liter [47]) and were shaken at 37°C for about two and a half hours until they reached OD600 ~ 0.3. At this point, the cultures were made 3 mM for CN and/or 2 mM for H2O2 (or the indicated treatment) and the shaking at 37°C was continued. In order to measure survival/revival in cells treated with CN + H2O2, the cells were spun down, resuspended in fresh LB and shaken at 37°C for various amount of time. Viability of cultures was measured at the indicated time points by spotting 10 μL of serial dilutions in 1% NaCl on LB plates (LB medium supplemented with 15 g of agar per liter). The plates were incubated overnight at 28°C, the next morning colonies in each spot were counted under the stereomicroscope. All titers have been normalized to the titer at time 0 (just before the treatment).

2.4. Measuring Chromosomal Fragmentation via Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis

This was done exactly as before [15] and follows our general protocol [49, 50].

3. Results

3.1. Conditions with reduced chromosome fragmentation for sensitive mutants

Concentrations of KCN up to 300 mM and H2O2 up to 10 mM are bacteriostatic for WT E. coli grown in a rich medium, while their 3 mM KCN + 2 mM H2O2 combination is strongly bactericidal [15, 25]. To gain insights into both the primary DNA lesions and the ultimate chromosomal consequences after KCN + H2O2 treatment, we used the survival and chromosomal fragmentation as the two readouts with select mutants in DNA repair. However, some of these mutants proved to be so sensitive to our standard 3 mM KCN + 2 mM H2O2 treatment, that we had to develop milder treatment regimens to observe any survivors at the earliest time points. We found that reducing CN concentration 10 times does not affect the early rate of killing of WT cells, while reducing H2O2 concentration 10 times decreases the early rate of killing somewhat (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1AB). At the same time, if the concentration of both CN and H2O2 is reduced 10-fold, the treatment becomes bacteriostatic for WT cells (Fig. 1B), as we have reported before [15]. The rate of early (5 minutes) chromosome fragmentation during CN + H2O2 treatment is reduced ~2-fold when 10 times lower CN concentration is used, whereas it is reduced ~8-fold when both CN and H2O2 concentrations are decreased 10-fold (Fig. 1CD). We used 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 conditions for the sensitive mutants, while reserving the 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 conditions (that do not kill WT cells) for the hyper-sensitive mutants.

3.2. ABS-endonucleases prevent double-strand breaks

The two major pathways for repair of one-strand DNA lesions in E. coli are nucleotide excision repair (NER) and base excision repair (BER) [51]. In addition, there is also the most basic pathway to close all kinds of single-strand interruptions, catalyzed by DNA pol I and DNA ligase that serves both the excision repair pathways, as well as DNA replication [52]. We found that the NER-deficient uvrA and uvrB mutants have the wild type sensitivity to CN + H2O2 (Fig. 2A), indicating that NER has no role in mending the CN + H2O2 induced DNA lesions and suggesting that oxidative DNA lesions are unlike the bulky and/or DNA helix-distorting lesions, or interstrand crosslinks, all repaired by NER [28].

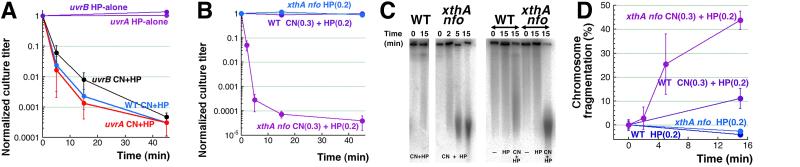

Fig. 2. Mutants in base excision repair are extremely sensitive to CN + H2O2 treatment, but not to H2O2-alone treatment.

A. Kinetics of death of the uvrA and uvrB mutants, compared to WT cells, treated with 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 or with 2 mM H2O2 alone.

B. Kinetics of death of the xthA nfo double mutant treated with 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 or 0.2 mM H2O2 alone.

C. Representative pulsed-field gels demonstrating chromosomal fragmentation induced in the xthA nfo double mutant treated with 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 compared to WT cells (left) or comparison of H2O2-alone treatment with CN + H2O2 treatment (right).

D. Quantification of the kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation in xthA nfo and WT cells upon treatment with 0.2 mM H2O2 alone or with 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 (from several gels like in “C”).

We blocked base-excision repair at the critical stage of abasic site nicking, inactivating both the major abasic site endonuclease (XthA) and the minor one (Nfo) [51]. Both xthA single and xthA nfo double mutants are hypersensitive to the CN + H2O2 treatment (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2), indicating that this treatment causes massive base damage. Since any mechanism of base-damage-induced chromosome fragmentation assumes conversion of abasic sites into ss-breaks, and the H2O2-induced double-strand breaks were supposed to be due to ss-break clustering (Fig. 1A), we expected much reduced chromosome fragmentation in the xthA nfo double mutant. To our surprise, we found that the ABS-endo mutants exhibit massive chromosomal fragmentation far greater than the WT cells under similar conditions (see Fig. 2CD for xthA nfo and Fig. 5BC for xthA alone), suggesting conversion of unrepaired abasic sites into double-strand breaks. At the same time, the ABS-endo mutants are neither sensitive to the corresponding H2O2-alone treatment (Fig. 2B and S2), nor show any chromosomal fragmentation after it (Fig. 2CD). Therefore, abasic sites are not produced by H2O2 acting alone, yet they are massively induced when the same H2O2 treatment is potentiated by cyanide.

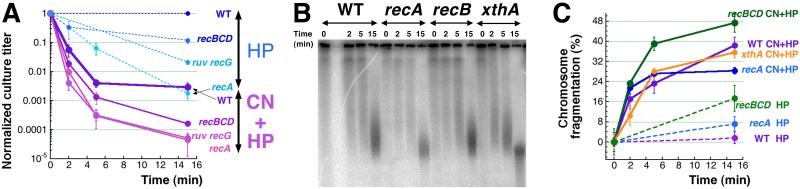

Fig. 5. Recombinational repair mutants are more sensitive than the WT cells to CN + H2O2 treatment.

A. Kinetics of survival of the recombinational repair mutants treated with 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2. The survival of 2 mM H2O2-alone treatment is shown for comparison from Fig. 4B.

B. A representative pulsed-field gel of kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation in the recA and recBC mutants treated with 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 compared with WT and xthA mutant cells.

C. Quantification of the kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation upon treatment with 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 in recA and recBC mutants compared to WT and xthA mutant cells (from several gels like in “B”). For comparison, fragmentation levels of H2O2-alone treatment from Fig. 4D are also shown.

3.3. The two types of CN + H2O2-induced one-strand DNA lesions and their repair

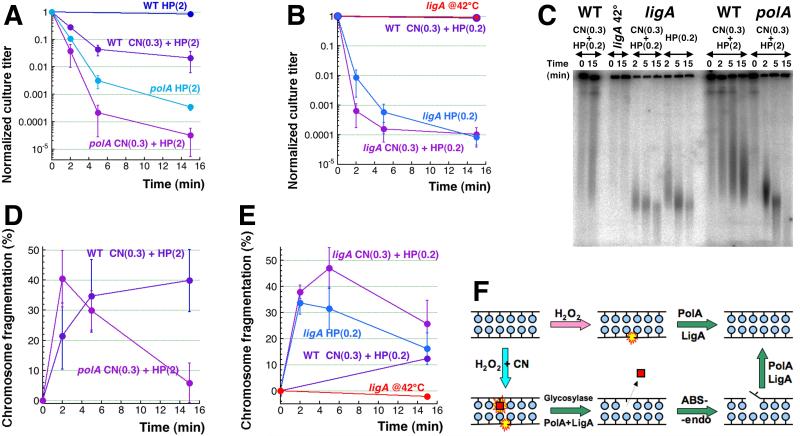

The mutants most sensitive to CN + H2O2 killing turned out to be the ss-break repair mutants, polA and ligA (Fig. 3AB) (the difference in the treatment doses is because the polA12(Ts) mutant we use has the mildest DNA pol I defect of all polA mutants [53], in contrast to our ligA251(Ts) mutant, which is a complete inactivation at the non-permissive temperature [45, 54, 55]). Remarkably, unlike the abasic site endonuclease mutants, both ss-break repair mutants show a distinct pattern of similar sensitivities to both CN + H2O2 and H2O2 alone treatments (Fig. 3AB) and exhibit similarly enhanced catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation in response to both treatments (Fig. 3CDE). (The level of fragmentation goes down at later times due to over-fragmentation and short linear DNA migrating out of the gel [15].) This demonstrates that, far from being innocuous, H2O2 alone treatment induces copious ss-breaks in DNA (confirming prior observations [29, 35]), but these ss-breaks are promptly repaired by DNA pol I and DNA ligase. Interestingly, CN-potentiation only moderately increases the number of these “direct” ss-breaks.

Fig. 3. Mutants in singe-strand break repair are similarly sensitive to both treatments.

A. Kinetics of death of the polA12 (Ts) mutant and WT cells treated with 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 or 2 mM H2O2 alone at 42°C.

B. Kinetics of death of the ligA251(Ts) mutant and WT cells treated with 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 or 0.2 mM H2O2 alone at 42°C. The ligA251(Ts) mutant and WT cells are pre-grown at 28°C for two and a half hours prior to addition of 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 or 0.2 mM H2O2, after which they are shifted to 42°C for the duration of the treatment. An untreated ligA control is also included to demonstrate that the mutant does not start dying due to the ligase defect for up to 15 minutes after being shifted to 42°C [45].

C. A representative pulsed-field gel demonstrating chromosomal fragmentation induced in the ligA mutant treated with 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 or 0.2 mM H2O2 alone compared to WT at 42°C (along with untreated ligA control), and in the WT and polA mutant treated with 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 at 42°C.

D. Quantification of the kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation upon treatment with 0.3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 in polA and WT cells (from several gels like in “C”).

E. Quantification of the kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation upon treatment with 0.3 mM CN + 0.2 mM H2O2 or 0.2 mM H2O2 alone in ligA and WT cells (from several gels like in “C”).

F. A scheme of base-excision repair and ss-break repair of H2O2-alone or CN + H2O2-induced DNA lesions.

Taken together, the results from the most sensitive mutants suggest that ss-breaks dominate among H2O2-induced DNA lesions, while CN potentiation of H2O2 treatment leads to the additional induction of base modifications, removed by base-excision repair via the abasic site intermediate (Fig. 3F). Most surprisingly, without immediate and complete repair, a significant fraction of these one-strand lesions and repair intermediates is converted into double-strand breaks, which we detect as catastrophic, “pulverizing” chromosome fragmentation in these mutants (Figs. 2C and 3C). The mode of the size distribution of the chromosomal fragments in ligase mutants after CN(0.3) + H2O2(0.2) treatment is ~50 kbp, translating into at least 100 double-strand breaks per genome-equivalent.

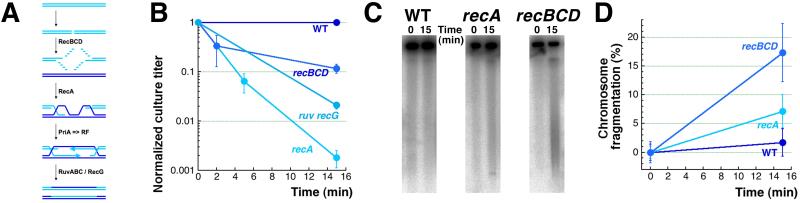

3.4. Recombinational repair mends H2O2-induced, but not CN + H2O2-induced double-strand breaks

The major pathway to mend double-strand DNA breaks in E. coli is recombinational repair [56-58] (Fig. 4A), and since CN + H2O2 treatment induces double-strand breaks, recombinational repair mutants were expected to show extreme sensitivity to CN + H2O2 treatment. Because of the known sensitivity of recA and recBC mutants to H2O2-alone treatment [13, 14, 35], we expected recombinational repair to mend double-strand breaks induced by hydrogen peroxide alone and we have confirmed these expectations, both by survival (Fig. 4B) and by physical analysis of chromosomal fragmentation in WT cells versus rec mutants (Fig. 4CD). It should be noted that the recBCD mutants, deficient in both linear DNA repair and degradation, show the level of total fragmentation, whereas the WT cells show the level of irreparable fragmentation (which is very low, in this case, indicating complete repair).

Fig. 4. H2O2-alone-induced double-strand breaks and their recombinational repair.

A. A scheme of double-strand break repair in E. coli, with the critical enzymes marking the corresponding stages.

B. Survival of recombinational repair mutants after 2 mM H2O2-alone treatment.

C. A representative gel showing chromosome fragmentation in WT versus recA and recBCD mutants treated with 2 mM H2O2.

D. Quantification of the chromosomal fragmentation upon treatment with 2 mM H2O2.

Remarkably, recombinational repair mutants are much less sensitive to H2O2-alone treatment than the most sensitive mutants in ss-break repair, which is reflected in their 2 mM H2O2 killing concentration (Fig. 4B), compared to the 10-times lower 0.2 mM killing H2O2 concentrations for the ligA mutants (Fig. 3B). The apparent reason for this difference is the much lower number of double-strand breaks in recombinational repair mutants after the same H2O2 treatment, most likely because of the functional ss-break repair. This is a strong, though indirect, evidence that timely ss-break repair prevents massive chromosomal fragmentation during oxidative damage.

Addition of cyanide to the H2O2-alone treatment decreases survival of the WT cells, as well as the recA, recBCD and the double recG ruvABC mutants, two-three orders of magnitude from the corresponding levels after H2O2-alone treatment, generally preserving the relationship between the four strains (Fig. 5A). The level of CN + H2O2-induced chromosomal fragmentation, even though increased, also appears to be similar in the WT cells and in the rec mutants (and generally less than in the BER mutants) (Fig. 5BC). Thus, instead of the expected devastating effect of the CN + H2O2 treatment on recombinational repair mutants compared to the WT cells, we observed a comparable deterioration for all of them, independently of their rec status (Fig. 5). This means that, although recombinational repair does efficiently mend a limited number of double-strand breaks due to H2O2 -alone treatment, additional double-strand breaks induced by CN + H2O2 treatment are not repaired, at least not during the treatment itself.

3.5. Recombinational repair efficiently mends several breaks per chromosome, but is paralyzed by CN

In fact, this conclusion was expected, as all recombinational repair enzymes hydrolyze ATP to fuel their activities [56], while even 2 mM CN is known to lower ATP production to 5-10% of the WT levels [59, 60], which should inhibit recombinational repair. For example, RecBCD exonuclease is expected to degrade fragmented chromosome during the CN+HP treatment, but no such chromosomal DNA degradation is observed until cyanide is removed from the medium (T.M. and A.K., unpublished). Because of this dependence of recombinational repair on ATP-hydrolysis, we originally considered recombinational repair a likely target of CN-potentiation, similar to our earlier suspicion about catalases [15]. However, a much higher sensitivity of recombinational repair mutants to CN + H2O2 treatment compared to H2O2 -alone treatment (Fig. 5A) argues against this possibility, as mutants inactivating the target of CN potentiation of H2O2 toxicity are expected to be equally sensitive to both H2O2 -alone and CN + H2O2 treatments [15].

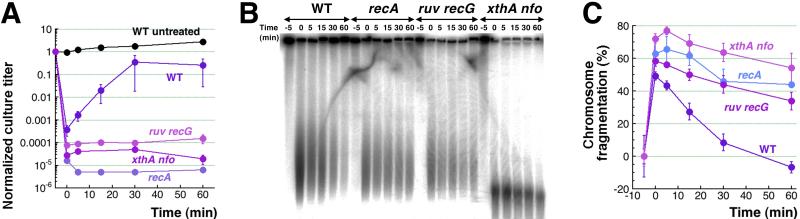

To reveal the role of recombinational repair in mending CN + H2O2-induced chromosomal fragmentation, we removed the treatment by pelleting cells and resuspending them in fresh medium to allow resumption of ATP-production, and then followed both the culture titer and the level of fragmentation with time. We detected no repair after 45 minute CN + H2O2 treatment (not shown), apparently due to the massive chromosomal fragmentation overwhelming the WT double-strand break repair capacity. In contrast, after a short 5 minute treatment followed by removal of CN + H2O2, we observed an almost three orders of magnitude recovery in the culture titer (to 30% of the original titer) (Fig. 6A), accompanied by a complete disappearance of chromosomal fragmentation (Fig. 6BC). The median size of sub-chromosomal fragments is ~500 kbp after 5 minute treatment (Fig. 6B), translating into ~10 double-strand breaks per genome-equivalent. There was neither recovery of the culture titer, nor significant repair of chromosomal fragmentation in the recA single mutant or in the ruvABC recG double mutant (Fig. 6), indicating that both phenomena are due to recombinational repair. There was also no recovery or repair (but evident DNA degradation) in the xthA nfo double mutant, in which the density of double-strand breaks after even 5 minute treatment is much higher and is similar to the density of double-strand breaks in WT cells after 45 minute treatment (the median size of sub-chromosomal fragments is ~50 kbp (Fig. 6B), translating into ~100 double-strand breaks per genome-equivalent). We conclude that when ATP-production resumes, recombinational repair is still capable of reassembling fragmented chromosomes if there are 10 or fewer double-strand breaks per genome equivalent, but its capacity is saturated when the density of double-strand breaks is increased 10-fold.

Fig. 6. Recombinational repair of CN + H2O2-induced double-strand breaks.

A. Kinetics of survival/’revival’ after 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 treatment. After 5 minutes of treatment, CN and H2O2 were removed by pelleting cells by centrifugation, resuspending in fresh LB and allowing to recover at 37°C. Repair-deficient mutants, such as recA, recG ruvABC and xthA nfo, were included as negative controls. Growth of the untreated WT culture was also monitored in parallel.

B. A representative pulsed-field gel showing the disappearance of catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation in WT cells induced by 5-minute CN + H2O2 treatment, upon removal of the treatment at time = 0. In contrast, recA, recG ruvABC and xthA nfo mutants after the same treatment show only decrease in the levels of chromosomal fragmentation consistent with some linear DNA degradation.

C. Quantification of the disappearance of catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation in WT cells induced by 5-minute CN + H2O2 treatment upon their removal, compared to the lack of it in recA, recG ruvABC and xthA nfo mutants (from several gels like in ‘B’).

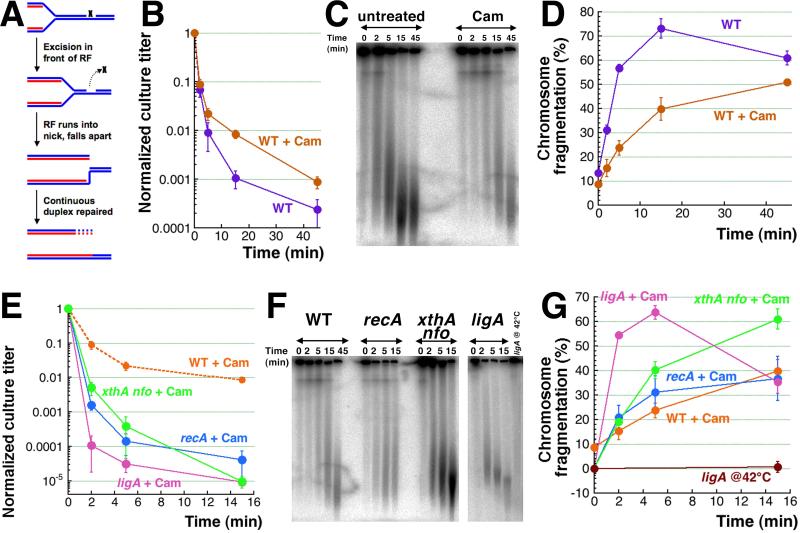

3.6. Blocking replication and protein synthesis does not save cells from CN + H2O2 induced double-strand breaks and killing

The extremely high density of double-strand breaks (~100 per genome equivalent) is unique to (CN +) H2O2-induced chromosome fragmentation [15] (phleomycin-induced fragmentation may be another example [49]), but the nature of these breaks is perplexing. Indeed, as our genetic analysis suggests, the primary DNA lesions caused by H2O2 are one-strand interruptions (ss-breaks), while CN potentiation causes additional base modifications, which eventually translate into more ss-breaks (Fig. 3F). Typically, ss-breaks by themselves cannot fragment DNA; they cause chromosomal fragmentation only during the replication-segregation transition (Fig. 1A), as either replication fork collapse events (Fig. 7A) [56] or segregation fork collapse events [41, 45]. Therefore, the subchromosomal fragments released as a result of fork collapse events in asynchronous cultures have the length distribution from close to zero to the full chromosome size [50, 61], which is not what we observe after 45 minutes of CN + H2O2 treatment, that produces chromosomal DNA broken into uniformly short fragments (Fig. 1B) [15].

Fig. 7. CN+H2O2-induced killing and chromosome fragmentation in chloramphenicol-treated cells.

A. A scheme of replication fork (RF) collapse at a ss-break in template DNA.

B. Kinetics of death in WT cells treated with 40 μg/ml chloramphenicol for two hours, to stop any replication in the chromosome, before treatment with 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2.

C. A representative gel showing the level of CN + H2O2-induced chromosomal fragmentation in chloramphenicol-treated versus untreated WT cells.

D. Quantification of the kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation from several gels like in “C”.

E. Kinetics of death of non-replicating WT, recA, ligA(Ts) and xthA nfo cultures pre-treated with 40 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Cam) for 2 hours before treatment with 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2. The ligA(Ts) mutant was pre-grown and treated with chloramphenicol at 28°C and was shifted to 42°C upon adding CN + H2O2.

F. A representative pulsed-field gel demonstrating the catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation induced in chloramphenicol pre-treated non-replicating WT, recA, ligA(Ts) and xthA nfo cultures by the 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 treatment.

G. Quantification of the kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation upon treatment with 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 (from several gels like in ‘F’) in chloramphenicol pre-treated non-replicating WT, recA, ligA(Ts) and xthA nfo cultures. Lack of fragmentation in the untreated ligA(Ts) mutant at 42°C within the time frame of experiment is also shown.

To test the replication-dependence of CN + H2O2-induced fragmentation, we blocked initiation of new replication rounds for two hours, while allowing ongoing rounds to finish, which aligns the chromosomes in the fully-replicated state, devoid of any replication forks. A classic and reliable way to align the chromosomes in bacteria is to block protein synthesis with chloramphenicol (because replication initiation requires new protein synthesis) [62]. The chloramphenicol block does reduce the killing of WT cells slightly (Fig. 7B) and reduces the overall fragmentation about two-fold (Fig. 7CD). However, chloramphenicol pretreatment fails to prevent both fragmentation and cell killing, demonstrating their significant independence of replication or segregation events and even of protein synthesis.

Since blocking protein synthesis would preclude any kind of inducible repair in WT cells (that may negate the positive consequences of replication removal), we thought that DNA repair mutants that are hyper-sensitive to CN + H2O2 treatment could be a more sensitive system to detect the effect of replication block. In other words, if chloramphenicol-treated DNA repair mutants were to show the sensitivity of chloramphenicol-treated WT cells, this would mean a huge boost to their CN + H2O2 resistance. However, the chloramphenicol-treated DNA repair mutants were still 100-1,000 times more sensitive to CN + H2O2 compared to WT cells (Fig. 7E). The levels of chromosome fragmentation in them were also significant (Fig. 7FG), leaving no chances for increased survival. We conclude that blocking replication via protein synthesis inhibition does not save from CN + H2O2 poisoning via catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation, indicating that a good half of induced double-strand breaks require no replication forks for their formation.

3.7. Chromosome alignment in the initiation mutants

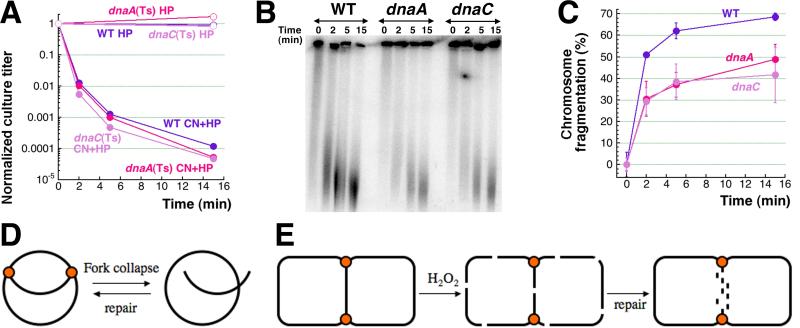

The most non-invasive way to align the chromosome is to utilized dnaA(Ts) and dnaC(Ts) mutants, that have heat-sensitive replication initiation and in 2 hours at 42°C have complete chromosomes without replication forks, but with all other cellular processes unaffected [63, 64]. We found that after 2 hours at 42°C the dnaA(Ts) and dnaC(Ts) mutants are killed with exactly the same kinetics as the corresponding WT strain (Fig. 8A), even though they reach early stationary phase at this point and barely fragment their chromosome (Fig. S3). Since we have already observed a similar effect (loss of viability without chromosome fragmentation) in the stationary cultures of the dps mutants before [15], we kept the dna(Ts) cultures from saturating by deep dilution before switching to 42°C. We found that CN + H2O2 induced significant chromosome fragmentation in non-replicating diluted cultures of dna(Ts) mutants at 42°C, even though this level was still ~1.5 times lower than in WT cells (Fig. 8BC) (which matches the chloramphenicol result above (Fig. 7CD)). Overall, we conclude that at least half of the CN + H2O2-induced chromosomal fragmentation is independent of DNA replication. Together with the finding that this fragmentation is at least partially irreparable by recombinational repair (Fig. 6A), the replication-independence means that these double-strand breaks form by mechanisms other than replication fork disintegration (Fig. 7A and 8D). For example, they could be direct double-strand breaks, reparable in the replicated part of the chromosome, but irreparable in the unreplicated part around the terminus (Fig. 8E).

Fig. 8. CN + H2O2-induced killing and chromosome fragmentation in dnaA(Ts) and dnaC(Ts) mutant cells at 42°C.

A. Kinetics of death of non-replicating dnaA46 and dnaC2 cultures in the AB1157 background (compared to exponential AB1157 cultures) upon treatment with 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2. The AB1157, dnaA46(Ts) and dnaC2(Ts) mutants were pre-grown at 28°C for two hours and then shifted to 42°C for two hours, following which the CN + H2O2 treatment was carried out at 42°C.

B. A representative pulsed-field gel demonstrating the catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation induced in non-replicating dnaA46 and dnaC2 cultures by the 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 treatment (compared to the fragmentation observed in exponentially growing CN + H2O2 treated AB1157 cells). The AB1157, dnaA46(Ts) and dnaC2(Ts) mutants were pre-grown at 28°C for two hours and then diluted 20 times and shifted to 42°C for two hours, followed by the CN + H2O2 treatment at 42°C.

C. Quantification of the kinetics of chromosomal fragmentation upon treatment with 3 mM CN + 2 mM H2O2 (from several gels like in “B”) in non-replicating diluted dnaA46 and dnaC2 cultures, compared with WT cells.

D. Replication fork collapse and recombinational repair at the chromosome level.

E. Replication-independent double-strand breaks all over the replicating chromosome and their subsequent repair in the duplicated parts. Chromosome is presented as a theta-replicating structure with replication forks identified by the orange dots. Note the impossibility of recombinational repair in the unreplicated part of the chromosome, which is instead degraded, killing the cell.

4. Discussion

Catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation is a novel phenomenon that we have discovered in E. coli cells killed by hydrogen peroxide (either by high, killing concentrations of H2O2-alone or by combined treatment of hydrogen peroxide and cyanide at concentrations of the two chemicals that individually are only bacteriostatic). In our previous work [15], we have shown that cyanide potentiation of oxidative damage by H2O2 works at two cellular levels: 1) via iron recruitment from the intracellular depots to fuel Fenton's reaction; 2) by depositing the recruited iron directly onto DNA and thus promoting the so-called DNA self-targeting Fenton’s reaction, which, by catalyzing hydroxyl radical formation right on DNA, generates double-strand DNA breaks.

In this work, we have characterized the DNA damage aspects of the CN-potentiated H2O2 toxicity by measuring survival and chromosomal fragmentation in various DNA repair mutants. As explained previously [15, 25], finding a mutant equally sensitive to H2O2-alone and CN + H2O2 treatments could mean that the corresponding repair enzyme is a target of cyanide potentiation. However, the only mutant in DNA repair showing this behavior is deficient in DNA ligase, an enzyme that requires Mg2+ as the only metal cofactor and that cannot be, therefore, inactivated by CN via demetallation (cyanide forms tight complexes with transition metals, like iron or copper, but not with Mg2+). Interestingly, unlike eukaryotic ATP-dependent ligases, bacterial NAD+-dependent ligase [65] is not inactivated by CN via ATP depletion either.

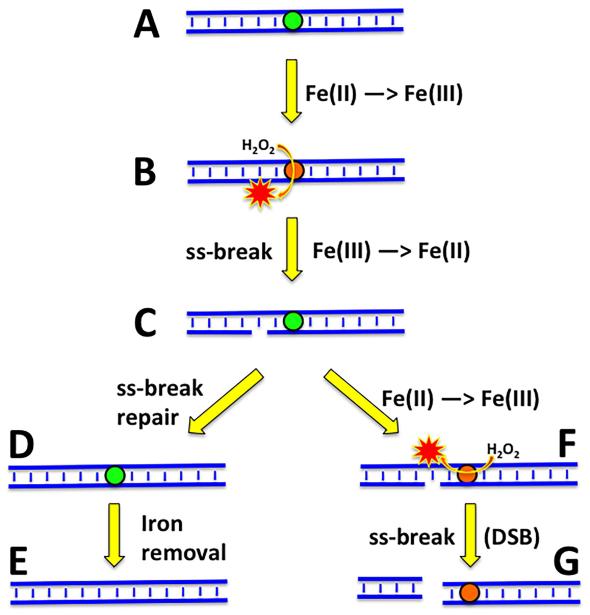

Even though our search for cyanide-inhibition targets among the DNA repair enzymes proved futile, we found evidence consistent with formation of double-strand DNA breaks due to stable iron-DNA complexes: 1) the ABS-endo deficiency, instead of suppressing chromosome fragmentation, increases it; 2) the inability to repair ss-breaks, instead of modestly increasing chromosomal fragmentation, literally pulverizes the chromosome; 3) H2O2-induced double-strand breaks are partially independent of replication or segregation; 4) even in replicating cells, at least some of these breaks cannot be mended by recombinational repair. Our specific findings include:

— The ss-break repair mends the bulk of both the H2O2-alone-induced or CN + H2O2-induced primary DNA lesions, suggesting that they are ss-breaks.

— Compared to ss-break repair, base-excision repair plays a lesser role in mending H2O2-alone-induced primary DNA damage, but is critical for repair a significant part of the CN + H2O2-induced DNA damage, indicating that CN-potentiation redirects this part of oxidative damage to DNA bases.

— CN + H2O2-induced double-strand breaks form at ~50% efficiency in non-replicating chromosome and (judging by the unchanged size distribution of resulting chromosomal fragments) appear to be uniformly distributed over the chromosome.

— Recombinational repair efficiently mends a few double-strand breaks generated by H2O2-alone treatment.

— Recombinational repair does not function during the CN + H2O2 treatment, because cyanide inhibits production of ATP, while all recombinational repair functions depend on ATP hydrolysis. Once the treated cells are transferred to a CN-free medium, recombinational repair can mend ~10 double-strand breaks per genome equivalent. Recombinational repair in E. coli cannot mend 100 double-strand breaks per genome equivalent, at least not under our growth conditions.

Below we discuss these specific finding in detail.

4.1. The primary H2O2-induced DNA lesions and the possible nature of CN-potentiated base modifications

By itself, hydrogen peroxide has low reactivity with organic matter [3-5]; the DNA damage comes from hydroxyl radicals, that are products of H2O2 splitting by electrons derived from the free intracellular Fe(II) atoms [16, 66]. Since hydroxyl radicals interact with various organic substances at diffusion rates [5, 11], the expectation is that all three chemical constituents of DNA: sugars, phosphates and nitrogen bases, will be equally susceptible to hydroxyl radicals coming from cytosol. However, the observed sensitivity of the DNA repair mutants to H2O2-alone treatments indicates that the sugar-phosphate backbone is hit preferentially over DNA bases: the ABS-endo-deficient mutant shows no sensitivity to 0.2 mM H2O2, while the ligase mutant is extremely sensitive to this treatment. If we assume that hydroxyl radicals are indeed generated in the cytosol around DNA, this difference in sensitivities between the two mutants may reflect the fact that the duplex DNA structure hides the genetic information-carrying bases in the protective double spiral of the sugar-phosphate backbone, which absorbs most of the chemical reactivity coming to DNA [67].

Perhaps more likely, Fe(II) atoms form complexes with DNA phosphates, essentially targeting sugar-phosphate backbone for attacks by nascent hydroxyl radicals. If so, then cyanide potentiation not only dramatically induces production of hydroxyl radicals, but also expands their targets, as both the ligase and DNA pol I mutants, on the one hand, and the ABS-endo-deficient mutants on the other become sensitive to CN + H2O2 treatment. The sensitivity of ABS-endo-deficient mutants indicates that cyanide potentiation redirects part of the H2O2 damage to DNA bases which, according to the previous results, suggests that Fe(II) atoms directly bind to the DNA bases (in addition to sugar-phosphate backbone). In other words, CN not only releases Fe(II) from the intracellular depots and delivers it to DNA [15], but it also helps depositing Fe(II) onto both sugar-phosphate backbone and DNA bases. Two binding sites of iron on DNA, one at the backbone, while the other at the bases, have been proposed [68-70].

4.2. DNA-iron removal as a result of one-strand repair

One of the most surprising findings of this work is the critical role of base excision repair in prevention of double-strand breaks. The general expectation is that, in the absence of ss-break processing by DNA pol I or ligase, ss-breaks will accumulate, leading to a modest increase in double-strand breaks due to occasional coincidence of ss-breaks in opposite DNA strands. The genome-pulverizing density of double-strand breaks in ligase mutants apparently exceeds this expectation, but in the absence of actual measurements of the density of ss-breaks during these treatments one can only speculate about the mismatch between the two numbers. Others have observed in vitro that the density of double-strand breaks from H2O2 + Fe(II) treatment significantly exceeds the one expected from the density of ss-breaks in the same reaction (assuming that double-strand breaks result from coincidence of random ss-breaks) [71].

In the ABS-endo-deficient mutant, much fewer ss-breaks are expected due to the blocked base-excision repair. Yet, chromosomal fragmentation, instead of going down, is extreme in this mutant (Fig. 2C), indicating that completion of this repair somehow prevents subsequent formation of double-strand breaks. We would like to speculate that, since the original cause of the primary one-strand lesions appears to be the DNA-bound Fe(II), this prevention could work by removing the DNA-bound iron (Fig. 9). This removal could be potentially done by either any of the DNA repair enzymes (ABS-endonuclease, DNA pol I, DNA ligase) or, more likely, by the specialized iron depot protein Dps, that could be targeted to the culprit iron by the DNA repair activity in the region. The concept of proteins mopping up transition metal ions to take subsequent oxidative damage on themselves, has experimental support [72].

Fig. 9. A scheme of how hydrogen peroxide could induce direct double-strand DNA breaks, and how timely repair of one-strand DNA lesions could prevent them.

DNA duplex is shown in blue, the iron atoms are indicated by colored circles; green circles, Fe(II); orange circles, Fe(III). Red stars, hydroxyl radicals. A, formation of Fe(II)-DNA complex. B, hydrogen peroxide undergoes Fenton's reaction on DNA to generate hydroxyl radical. C, hydroxyl radical breaks one DNA strand. D, repair of the ss-break restores DNA integrity. E, the iron atom is removed from DNA (by Dps). F, in the absence of ss-break repair and subsequent iron removal, another Fenton's reaction with the same iron atom generates another hydroxyl radical nearby. G, the second DNA strand is disrupted opposite the first ss-break, breaking the DNA duplex.

If not removed from DNA, this iron could continuously cycle between Fe(II) and Fe(III), catalyzing formation of hydroxyl radicals that would eventually break both DNA strands in the same location, inducing a double-strand break (Fig. 9). The idea that oxidatively-induced double-strand DNA breaks are due to stable binding of a catalytic transition metal to DNA has a long history [71, 73-75] and has been formally presented [76].

4.3. The replication-independent HP-induced double-strand breaks

Another unexpected finding, that we had to document carefully, was the partial replication independence of CN + H2O2-induced double-strand breaks. Since oxidative damage is supposed to break (directly or via excision repair) only one DNA strand at a time [29, 35], we expected complete dependence of fragmentation on replication or segregation, like in the cases of UV irradiation or ligase-deficiency [45, 77]. However, aligning the chromosome by blocking new initiations and allowing the existing replication forks to finish did not save the cells from killing and only reduced the observed fragmentation ~2-fold, suggesting that at least half of the double-strand breaks are replication/segregation-independent, in other words — direct. This dovetails with the proposed model of Fenton's reaction-promoted double-strand DNA breakage as a result of stable DNA-iron complex catalyzing formation of multiple hydroxyl radicals at the same DNA location and thus increasing the likelihood of breaks in both DNA strands (Fig. 9). Such double-strand breaks are expected to be completely independent of replication or segregation. Recently, the replication fork-independence of H2O2-induced double-strand breaks (with H2AX foci as a readout) was reported in human cells [78, 79], even triggering a suspicion that H2AX foci do not necessarily identify double-strand breaks [79].

4.4. Recombinational repair of H2O2-induced DNA lesions

In contrast to H2O2-induced one-strand DNA lesions, whose nature differs depending on whether cyanide is present or absent, there appears no indication of heterogeneity among double-strand breaks induced by H2O2-alone or by CN + H2O2. Neither there is any difference in how they are recombinationally repaired, as long as their density appears similar. We did not quantify it systematically, but it is clear that E. coli is still in the position to reassemble one functional chromosome after experiencing ~10 double-strand breaks per genome equivalent, even though the survival is only 30%. At the other extreme, when the density of double-strand breaks reaches ~100 per genome equivalent, no repair or survival becomes possible. These numbers are most likely similar to other bacterial and eukaryotic cells alike [33, 80], as the massive experience in radiation sterilization testifies [81, 82]. The only exception is Deinococcus radiodurans and its relatives, capable of assembling chromosome with no loss of viability after 100 double-strand breaks per genome equivalent [83-85]. One reason for such a high resistance of Deinococcus to double-strand breaks is the presence of at least four genome-equivalents in resting cells, putting the minimal number of any chromosomal part per Deinococcus cells at four [86]. In contrast, the stationary E. coli cells, like most other bacteria, have a single chromosome, and even in the rapidly-growing E. coli cells, the copy number of chromosomal segments around the terminus is close to one, making any double-strand break there an irreparable lesion (Fig. 8E).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our results clearly support the idea that oxidative damage by hydrogen peroxide kills by inducing double-strand breaks in the chromosomal DNA. In addition, our investigation into the nature of DNA damage induced by hydrogen peroxide alone or by cyanide-potentiated hydrogen peroxide highlighted the important differences between the two in the position of the primary DNA damage and revealed the critical role of timely excision repair in prevention of the subsequent double-strand breaks. In combination with the unexpected lack of the critical role of DNA replication in formation of these double-strand breaks, this indirectly but strongly suggests that a significant fraction of lethal oxidative DNA lesions comes from stable DNA-iron complexes, as has been suggested before [71, 73-76]. In the presence of hydrogen peroxide, such stable complexes eventually “burn through” DNA, breaking both strands in the same location. In the future it would be important to detect such complexes inside the cell, as well as their promotion by cyanide and removal after excision repair. It would be also important to test whether H2O2 induces the same catastrophic chromosome fragmentation in Deinococcus and how efficiently the pulverized genome will be repaired in that unusual bacterium.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

— Blocking BER of oxidative DNA damage pulverizes the chromosome in CN+HP-treated cells

— Thus, timely repair of one-strand lesions prevents the bulk of double-strand breaks

— Recombination repairs HP-induced double-strand breaks, but is poisoned by CN

— Blocking DNA replication halves CN+HP-induced fragmentation, does not affect survival

— We propose that HP-induced double-strand breaks happen at stable DNA-iron complexes

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the members of this laboratory for enthusiastic discussion of our results and for general support. We are grateful to Bénédicte Michel for her interest in this work and for helpful suggestions to clarify the presentation. This work was supported by grant # GM 073115 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CN

cyanide

- HP

hydrogen peroxide

- ss-break

single-strand DNA break

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Clifford DP, Repine JE. Hydrogen peroxide mediated killing of bacteria. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1982;49 doi: 10.1007/BF00231175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood. 1998;92:3007–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Eberhardt MK. Reactive Oxygen Metabolites - Chemistry and Medical Consequences. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Olinescu R, Smith T. Free Radicals in Medicine. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; Huntington, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pryor WA. Oxy-radicals and related species: their formation, lifetimes, and reactions. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1986;48:657–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Croot PL, Heller MI. The importance of kinetics and redox in the biogeochemical cycling of iron in the surface ocean. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00219. Article 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu X, Millero FJ. The solubility of iron in seawater. Mar. Chem. 2002;77:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ganz T. Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:1721–1741. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hartmann A, Braun V. Iron uptake and iron limited growth of Escherichia coli K-12. Arch. Microbiol. 1981;130:353–356. doi: 10.1007/BF00414599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Koppenol WH. The centennial of the Fenton reaction. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 1993;15:645–651. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90168-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB. Critical Review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (·OH/·O−) in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1988;17:513–886. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Imlay JA. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:755–776. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Imlay JA, Linn S. Bimodal pattern of killing of DNA-repair-defective or anoxically grown Escherichia coli by hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 1986;166:519–527. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.519-527.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Imlay JA, Linn S. Mutagenesis and stress responses induced in Escherichia coli by hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:2967–2976. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.7.2967-2976.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mahaseth T, Kuzminov A. Cyanide enhances hydrogen peroxide toxicity by recruiting endogenous iron to trigger catastrophic chromosomal fragmentation. Mol. Microbiol. 2015;96:349–367. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Imlay JA. Chapter 5.4.4. Oxidative Stress. In: Böck A, Curtiss R III, Kaper JB, Karp PD, Neidhardt FC, Slauch JM, Squires CL, editors. EcoSal—Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Slauch JM. How does the oxidative burst of macrophages kill bacteria? Still an open question. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;80:580–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Winterbourn CC, Hampton MB, Livesey JH, Kettle AJ. Modeling the reactions of superoxide and myeloperoxidase in the neutrophil phagosome: implications for microbial killing. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:39860–39869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pacelli R, Wink DA, Cook JA, Krishna MC, DeGraff W, Friedman N, Tsokos M, Samuni A, Mitchell JB. Nitric oxide potentiates hydrogen peroxide-induced killing of Escherichia coli. J. Exp. Med. 1995;182:1469–1479. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Smith AW, Green J, Eden CE, Watson ML. Nitric oxide-induced potentiation of the killing of Burkholderia cepacia by reactive oxygen species: implications for cystic fibrosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 1999;48:419–423. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-5-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Woodmansee AN, Imlay JA. A mechanism by which nitric oxide accelerates the rate of oxidative DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:11–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Berglin EH, Carlsson J. Potentiation by sulfide of hydrogen peroxide-induced killing of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 1985;49:538–543. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.3.538-543.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cantoni O, Giacomoni P. The role of DNA damage in the cytotoxic response to hydrogen peroxide/histidine. Gen. Pharmacol. 1997;29:513–516. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(96)00363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Park S, Imlay JA. High levels of intracellular cysteine promote oxidative DNA damage by driving the Fenton reaction. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:1942–1950. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.6.1942-1950.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Woodmansee AN, Imlay JA. Reduced flavins promote oxidative DNA damage in non-respiring Escherichia coli by delivering electrons to intracellular free iron. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:34055–34066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Breen AP, Murphy JA. Reactions of oxyl radicals with DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;18:1033–1077. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dizdaroglu M, Jaruga P, Birincioglu M, Rodriguez H. Free radical-induced damage to DNA: mechanisms and measurement. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;32:1102–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00826-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ward JF, Blakely WF, Joner EI. Mammalian cells are not killed by DNA single-strand breaks caused by hydroxyl radicals from hydrogen peroxide. Radiat. Res. 1985;103:383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Massie HR, Samis HV, Baird MB. The kinetics of degradation of DNA and RNA by H2O2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1972;272:539–548. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(72)90509-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dahm-Daphi J, Sass C, Alberti W. Comparison of biological effects of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation and hydrogen peroxide in CHO cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2000;76:67–75. doi: 10.1080/095530000139023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Iliakis G. The role of DNA double-strand breaks in ionising radiation-induced killing of eukaryotic cells. BioEssays. 1991;13:641–648. doi: 10.1002/bies.950131204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Resnick MA. Similar responses to ionizing radiation of fungal and vertebrate cells and the importance of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Theor. Biol. 1978;71:339–346. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(78)90164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Prise KM, Davies S, Michael BD. Cell killing and DNA damage in Chinese hamster V79 cells treated with hydrogen peroxide. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1989;55:583–592. doi: 10.1080/09553008914550631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ananthaswamy HN, Eisenstark A. Repair of hydrogen peroxide-induced single-strand breaks in Escherichia coli deoxyribonucleic acid. J. Bacteriol. 1977;130:187–191. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.187-191.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Blaisdell JO, Wallace SS. Abortive base-excision repair of radiation-induced clustered DNA lesions in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7426–7430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131077798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bonura T, Smith KC, Kaplan HS. Enzymatic induction of DNA double-strand breaks in g-irradiated Escherichia coli K-12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:4265–4269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.11.4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hartman PS, Eisenstark A. Killing of Escherichia coli K-12 by near-ultraviolet radiation in the presence of hydrogen peroxide: role of double-strand DNA breaks in absence of recombinational repair. Mutat. Res. 1980;72:31–42. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(80)90217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chen JH, Ozanne SE, Hales CN. Heterogeneity in premature senescence by oxidative stress correlates with differential DNA damage during the cell cycle. DNA Repair. 2005;4:1140–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Michel B, Grompone G, Florès MJ, Bidnenko V. Multiple pathways process stalled replication forks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12783–12788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401586101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rotman E, Khan SR, Kouzminova E, Kuzminov A. Replication fork inhibition in seqA mutants of Escherichia coli triggers replication fork breakage. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;93:50–64. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hanawalt PC. The U.V. sensitivity of bacteria: its relation to the DNA replication cycle. Photochem. Photobiol. 1966;5:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kuzminov A. Collapse and repair of replication forks in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;16:373–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Skalka A. A replicator's view of recombination (and repair) In: Grell RF, editor. Mechanisms in Recombination. Plenum Press; New York, NY: 1974. pp. 421–432. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kouzminova EA, Kuzminov A. Chromosome demise in the wake of ligase-deficient replication. Mol. Micorbiol. 2012;84:1079–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2:2006–0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Khan SR, Kuzminov A. Trapping and breaking of in vivo nicked DNA during pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 2013;443:269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kouzminova EA, Rotman E, Macomber L, Zhang J, Kuzminov A. RecA-dependent mutants in E. coli reveal strategies to avoid replication fork failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:16262–16267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405943101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Couvé S, Ishchenko AA, Fedorova OS, Ramanculov EM, Laval J, Saparbaev M. Chapter 7.2.4. Direct DNA Lesion Reversal and Excision Repair in Escherichia coli. In: Böck A, Curtiss R III, Kaper JB, Karp PD, Neidhardt FC, Slauch JM, Squires CL, editors. EcoSal—Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. ASM Press; Washington, D.C.: 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kornberg A, Baker TA. DNA Replication. W.H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sweasy JB, Loeb LA. Mammalian DNA polymerase ∫ can substitute for DNA polymerase I during DNA replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:1407–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dermody JJ, Robinson GT, Sternglanz R. Conditional-lethal deoxyribonucleic acid ligase mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1979;139:701–704. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.2.701-704.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lavesa-Curto M, Sayer H, Bullard D, MacDonald A, Wilkinson A, Smith A, Bowater L, Hemmings A, Bowater RP. Characterization of a temperature-sensitive DNA ligase from Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2004;150:4171–4180. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kuzminov A. Recombinational repair of DNA damage in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage l. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:751–813. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.4.751-813.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kuzminov A. Homologous Recombination—Experimental Systems. Analysis, and Significance, EcoSal Plus. 2011;4 doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.1127.1122.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Michel B, Leach D. Homologous Recombination - Enzymes and Pathways. EcoSal Plus. 2012;5 doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.1127.1122.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].St John AC, Goldberg AL. Effects of reduced energy production on protein degradation, guanosine tetraphosphate, and RNA synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:2705–2711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Weigel PH, Englund PT. Inhibition of DNA replication in Escherichia coli by cyanide and carbon monoxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:8536–8542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kouzminova EA, Kuzminov A. Fragmentation of replicating chromosomes triggered by uracil in DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Messer W. Initiation of deoxyribonucleic acid replication in Escherichia coli B-r: chronology of events and transcriptional control of initiation. J. Bacteriol. 1972;112:7–12. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.1.7-12.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Atkinson J, Gupta MK, Rudolph CJ, Bell H, Lloyd RG, McGlynn P. Localization of an accessory helicase at the replisome is critical in sustaining efficient genome duplication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:949–957. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Withers HL, Bernander R. Characterization of dnaC2 and dnaC28 mutants by flow cytometry. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:1624–1631. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1624-1631.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Wilkinson A, Day J, Bowater R. Bacterial DNA ligases. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:1241–1248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Imlay JA. Pathways of oxidative damage. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2003;57:395–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Pryor WA. Why is the hydroxyl radical the only radical that commonly adds to DNA? Hypothesis: it has a rare combination of high electrophilicity, high thermochemical reactivity, and a mode of production that can occur near DNA. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1988;4:219–223. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Eisinger J, Schulman RG, Szymanski BM. Transition metal binding in DNA solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 1962;36:1721–1729. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Luo Y, Han Z, Chin SM, Linn S. Three chemically distinct types of oxidants formed by iron-mediated Fenton reactions in the presence of DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:12438–12442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Netto LE, Ferreira AM, Augusto O. Iron(III) binding in DNA solutions: complex formation and catalytic activity in the oxidation of hydrazine derivatives. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1991;79:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90048-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Lloyd DR, Carmichael PL, Phillips DH. Comparison of the formation of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine and single- and double-strand breaks in DNA mediated by fenton reactions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998;11:420–427. doi: 10.1021/tx970156l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Gutteridge JM, Wilkins S. Copper salt-dependent hydroxyl radical formation. Damage to proteins acting as antioxidants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1983;759:38–41. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(83)90186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Gutteridge JM. Copper-phenanthroline-induced site-specific oxygen-radical damage to DNA. Detection of loosely bound trace copper in biological fluids. Biochem. J. 1984;218:983–985. doi: 10.1042/bj2180983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Schweitz H. Dégradation du DNA par H2O2 en présence d'ions Cu++, Fe++ et Fe+++ Biopolymers. 1969;8:101–119. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Ward JF, Evans JW, Limoli CL, Calabro-Jones PM. Radiation and hydrogen peroxide induced free radical damage to DNA. Br. J. Cancer Suppl. 1987;8:105–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chevion M. A site-specific mechanism for free radical induced biological damage: the essential role of redox-active transition metals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1988;5:27–37. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Khan SR, Kuzminov A. Replication forks stalled at ultraviolet lesions are rescued via RecA and RuvABC protein-catalyzed disintegration in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:6250–6265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Berniak K, Rybak P, Bernas T, Zarȩbski M, Biela E, Zhao H, Darzynkiewicz Z, Dobrucki JW. Relationship between DNA damage response, initiated by camptothecin or oxidative stress, and DNA replication, analyzed by quantitative 3D image analysis. Cytometry A. 2013;83:913–924. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Katsube T, Mori M, Tsuji H, Shiomi T, Wang B, Liu Q, Nenoi M, Onoda M. Most hydrogen peroxide-induced histone H2AX phosphorylation is mediated by ATR and is not dependent on DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biochem. 2014;156:85–95. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvu021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Krasin F, Hutchinson F. Repair of DNA double-strand breaks in Escherichia coli, which requires recA function and the presence of a duplicate genome. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;116:81–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Takehisa M, Shintani H, Sekiguchi M, Koshikawa T, Oonishi T, Tsuge M, Sou K, Yamase Y, Kinoshita S, Tsukamoto H, Endo T, Yashima K, Nagai M, Ishigaki K, Sato Y, Whitby JL. The radiation resistance of the bioburden from medical devices. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1998;52:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- [82].Whitby JL. Microbiological aspects relating to the choice of radiation sterilization dose. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1993;42:577–580. [Google Scholar]

- [83].Ghosal D, Omelchenko MV, Gaidamakova EK, Matrosova VY, Vasilenko A, Venkateswaran A, Zhai M, Kostandarithes HM, Brim H, Makarova KS, Wackett LP, Fredrickson JK, Daly MJ. How radiation kills cells: survival of Deinococcus radiodurans and Shewanella oneidensis under oxidative stress. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005;29:361–375. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Minton KW. Repair of ionizing-radiation damage in the radiation resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mutat. Res. 1996;363:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Moseley BEB. Photobiology and radiobiology of Micrococcus (Deinococcus) radiodurans. Photochem. Photobiol. Rev. 1983;7:223–275. [Google Scholar]

- [86].Hansen MT. Multiplicity of genome equivalents in the radiation-resistant bacterium Micrococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 1978;134:71–75. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.1.71-75.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Bachmann BJ. Derivations and genotypes of some mutant derivatives of Escherichia coli K-12. In: Neidhardt FC, editor. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Cellular and Molecular Biology. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, D.C.: 1987. pp. 1190–1219. [Google Scholar]

- [88].Gil D, Bouché J-P. ColE1-type vectors with fully repressible replication. Gene. 1991;105:17–22. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90508-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Csonka LN, Clark AJ. Deletions generated by the transposon Tn10 in the srl-recA region of the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. Genetics. 1979;93:321–343. doi: 10.1093/genetics/93.2.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Miranda A, Kuzminov A. Chromosomal lesion suppression and removal in Escherichia coli via linear DNA degradation. Genetics. 2003;163:1255–1271. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.4.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Benson F, Collier S, Lloyd RG. Evidence of abortive recombination in ruv mutants of Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1991;225:266–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00269858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Seigneur M, Bidnenko V, Ehrlich SD, Michel B. RuvAB acts at arrested replication forks. Cell. 1998;95:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Amado L, Kuzminov A. The replication intermediates in Escherichia coli are not the product of DNA processing or uracil excision. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:22635–22646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.