Abstract

In filamentous fungi, communication is essential for the formation of an interconnected, multinucleate, syncytial network, which is constructed via hyphal fusion or fusion of germinated asexual spores (germlings). Anastomosis in filamentous fungi is comparable to other somatic cell fusion events resulting in syncytia, including myoblast fusion during muscle differentiation, macrophage fusion, and fusion of trophoblasts during placental development. In Neurospora crassa, fusion of genetically identical germlings is a highly dynamic and regulated process that requires components of a MAP kinase signal transduction pathway. The kinase pathway components (NRC-1, MEK-2 and MAK-2) and the scaffold protein HAM-5 are recruited to hyphae and germling tips undergoing chemotropic interactions. The MAK-2/HAM-5 protein complex shows dynamic oscillation to hyphae/germling tips during chemotropic interactions, and which is out-of-phase to the dynamic localization of SOFT, which is a scaffold protein for components of the cell wall integrity MAP kinase pathway. In this study, we functionally characterize HAM-5 by generating ham-5 truncation constructs and show that the N-terminal half of HAM-5 was essential for function. This region is required for MAK-2 and MEK-2 interaction and for correct cellular localization of HAM-5 to “fusion puncta.” The localization of HAM-5 to puncta was not perturbed in 21 different fusion mutants, nor did these puncta colocalize with components of the secretory pathway. We also identified HAM-14 as a novel member of the HAM-5/MAK-2 pathway by mining MAK-2 phosphoproteomics data. HAM-14 was essential for germling fusion, but not for hyphal fusion. Colocalization and coimmunoprecipitation data indicate that HAM-14 interacts with MAK-2 and MEK-2 and may be involved in recruiting MAK-2 (and MEK-2) to complexes containing HAM-5.

Keywords: cell fusion, Neurospora crassa, MAP kinase signaling, protein complexes, chemotropism

FUSION between genetically identical cells exists in many organisms and plays an important role in different developmental processes, for example, myoblast fusion during the formation of muscle tissue, macrophage fusion, or fusion of trophoblasts in placental development (Chen and Olson 2005; Aguilar et al. 2013). In fungi, vegetative fusion enables a fungal colony to share resources and has implications for fitness and virulence (Craven et al. 2008; Fricker et al. 2009; Eaton et al. 2011; Richard et al. 2012; Simonin et al. 2012; Roper et al. 2013; Chagnon 2014). In the filamentous ascomycete fungus, Neurospora crassa, genetically identical germinated asexual spores (germlings) undergo fusion to form a syncytium that is an interconnected network of fused cells (Roca et al. 2005; Leeder et al. 2013; Herzog et al. 2015). An important pathway required for both germling and hyphal fusion is a conserved mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade that includes the MAPK kinase kinase NRC-1, the MAPK kinase MEK-2, the MAPK MAK-2, and the scaffold protein, HAM-5 (Pandey et al. 2004; Dettmann et al. 2012, 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). During germling fusion, chemotrophic growth is associated with oscillation of the MAK-2/MEK-2/NRC-1/HAM-5 complex and the regulatory adaptor subunit STE-50 to the fusion tips of germlings, conidial anastomosis tubes (CATs), and to the tips of hyphae undergoing chemotropic interactions prior to cell fusion (fusion hyphae) (Fleissner et al. 2009; Dettmann et al. 2012, 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). The oscillation of the MAK-2 signaling complex is perfectly out of phase with a second protein, called SOFT, which is also essential for chemotropic interactions and cell fusion (Fleissner et al. 2005). Switching between the MAK-2 complex and SOFT at the tips of cells undergoing chemotropic interactions occurs every ∼4–5 min (Fleissner et al. 2009; Jonkers et al. 2014). Phosphorylation and subsequent dephosphorylation of HAM-5 has been hypothesized to regulate the assembly and disassembly of the MAK-2 complex at CATs and hyphal fusion tips (Jonkers et al. 2014). However, how the oscillation of the MAK-2 complex and SOFT is initiated and sustained during chemotropic interactions is currently unclear, and the input signals important for phosphorylation of HAM-5 are unknown.

The scaffold protein HAM-5 was identified as a putative MAK-2 target using a global phosphoproteomics approach (Jonkers et al. 2014) and via mass spectrometry with epitope-tagged MAK-2 (Dettmann et al. 2014). Deletion of ham-5 results in a mutant unable to undergo germling and hyphal fusion and also results in the inability of the MAK-2 complex to form distinct puncta, which in wild-type germlings and hyphae is associated with oscillation of the MAK-2 complex to CATs and to tips of fusion hyphae (Aldabbous et al. 2010; Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). HAM-5 is a large protein of 1686 amino acids (aa) that binds MAK-2 via the N-terminal WD40 domain and MEK-2 via regions distal to the WD40 domain (Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). In this study, we constructed versions of HAM-5 with sequential truncations to identify domains required for function and cellular localization. We further expressed HAM-5–GFP in 21 fusion mutant strains and studied colocalization of HAM-5–GFP with fluorescent-tagged cellular marker proteins. A second protein, HAM-14, was identified by mining phosphoproteomics data (Jonkers et al. 2014). Deletion of ham-14 resulted in a mutant unable to undergo germling fusion, but which is competent to undergo hyphal fusion. Although HAM-14 localized to puncta and to the cytoplasm, it did not show colocalization or oscillation with the MAK-2 signaling complex or with SOFT. However, by coimmunoprecipitation studies, HAM-14 was shown to interact with MAK-2 and MEK-2. Our data support a model whereby HAM-14 plays a role in facilitating interaction between HAM-5 and MAK-2/MEK-2 and their subsequent localization to fusion complexes. These data provide new insights into the composition of the MAK-2 complex during chemotropic interactions and the molecular processes underlying chemotropic growth and cell fusion.

Materials and Methods

Molecular techniques and strain construction

Strains used and constructed for this study are listed in Supplemental Material, Table S1. Strains were grown on Vogel’s minimal medium (VMM) (Vogel 1956) (with supplements as required) and were crossed on Westergaard’s medium (Westergaard and Mitchell 1947). Transformations and other N. crassa molecular techniques were performed as described (Colot et al. 2006) or using protocols available at the Neurospora home page at the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (FGSC) (http://www.fgsc.net/Neurospora/NeurosporaProtocolGuide.htm). The his-3::Ptef1-ham-5-gfp and Ptef1-Lifeact-TagRFP-T::nat1 strains were obtained by crossing his-3::Ptef1-ham-5-gfp with FGSC10598 (Table S1) with selection of progeny that showed both GFP and RFP fluorescence.

The ham-5 truncation alleles were created via PCR with forward primer 1 and reverse primers 2–9 (Table S2). These PCR fragments were cloned into the pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen). We sequenced and digested the constructs from the pCR-Blunt vector with the restriction enzymes NsiI (unique internal ham-5 site) and PacI (in the linkers of the reverse primers). The constructs were ligated into plasmid pMF272 + ham-5 digested with NsiI and PacI (Margolin et al. 1997; Freitag et al. 2004). The ham-14 gene was cloned using primers 10 and 11 (Table S2), which have XbaI and PacI restriction enzyme sites included, respectively. This PCR product was inserted into the pCR-Blunt vector, sequenced, and digested with XbaI and PacI. The digested construct was ligated into pMF272 between either the gfp (Freitag et al. 2004) or mCherry (Jonkers et al. 2014) gene and with either the ccg-1 or the tef-1 promoter using restriction enzymes XbaI and PacI. The promoter region (1387 bp upstream of the start codon) of ham-14 was amplified using primers 14 and 15 (Table S2), which have NotI and XbaI restriction enzyme sites included, respectively. The PCR product was cloned into the pCR-Blunt vector, sequenced, digested with NotI and XbaI, and ligated into the plasmid instead of the tef-1 promoter using restriction enzymes NotI and XbaI.

To construct strains expressing secretory pathway proteins that are N-terminally fused to the red fluorescent protein tdimer(2)12 (Campbell et al. 2002), open reading frames corresponding to the homologs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SEC7 (NCU07658), SEC13 (NCU04063), and SEC23 (NCU01318) were amplified by PCR and cloned into plasmid pMF334 (Freitag and Selker 2005). The following forward and reverse primer pairs were used to amplify the genes for cloning: 16 and 17 for NCU07658-, 18 and 19 for NCU04063-, and 20 and 21 for NCU01318 (Table S2). All forward primers contained a SpeI restriction enzyme cleavage site. The reverse primers for NCU04063 and NCU01318 contained an XbaI cleavage site, whereas the reverse primer for NCU07658 contained an FseI site.

All constructs were transformed into the his-3 strain FGSC6103 with selection for His+ prototrophy. Homokaryotic strains were obtained via microconidial purification (Pandit and Maheshwari 1994). Deletion strains were obtained from the FGSC (McCluskey 2003) that were generated as part of the N. crassa functional genomics project (Colot et al. 2006; Dunlap et al. 2007). For each deletion strain, both the mating type A and mating type a strains were analyzed, if available.

Phenotypic analyses

Growth of the different strains (WT, ∆ham-14, ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp, and segregation strains) on VMM plates was measured at 25° by spotting 5 µl of a 106 conidia/ml suspension or by placing an agar plug (10 mm) with hyphae in the center of Petri plates. Aerial hyphal extension was determined by inoculating tubes containing 1 ml of liquid Vogel’s minimal medium with 1 × 106 conidia; aerial hyphae height was measured after 3 days of growth at 25° in constant light. Six replicates were measured for each strain. Growth on slant tubes with WT, ∆ham-14, ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp, segregation strains, and the ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-5-gfp strains was assessed by placing an inoculum of each strain on the agar and letting them grow for 2 days at 30° in the dark and for 1 week at room temperature on the bench.

To assess the ability of germling fusion of deletion strains as compared to wild type, slant tubes containing the strains were grown for 4–6 days or until significant conidiation occurred. Conidia were harvested by vortexing the slant tube with 2 ml ddH2O and subsequently filtered by pouring over cheesecloth to remove hyphal fragments. Conidia were diluted to a concentration of 3.3 × 107 conidia/ml. For each sample, 300 μl of spore suspension was spread on a 9-cm solid VMM plate. The plates were dried in a fume hood for 20–30 min and incubated for 3–4 hr at 30°. After 3–4 hr, most spores have germinated and a germ tube or CAT has emerged. Squares of 1 cm were excised and observed with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 using a ×40 Plan-Neofluor oil immersion objective. The ability of germlings to communicate and fuse was determined by evaluating whether germlings displayed homing behavior or had fused when germinated conidia were within ∼15 μm of each other (Leeder et al. 2013). Chemotropic redirected growth of germ tubes/CATs toward each other is evidence of communication. Chemotropism is terminated upon contact, which is followed by cell wall breakdown and membrane merger of the two interacting cells. Multiple frames containing ∼100 germlings were examined for pairs of cells that had fused or were undergoing chemotropic interactions. Germlings were considered deficient in chemotropic interaction and fusion when germ tubes grew outwardly straight following conidial germination and cell fusion was not observed, a phenotype markedly different from that of interacting germlings (see Figure 1D and Figure 3A for examples).

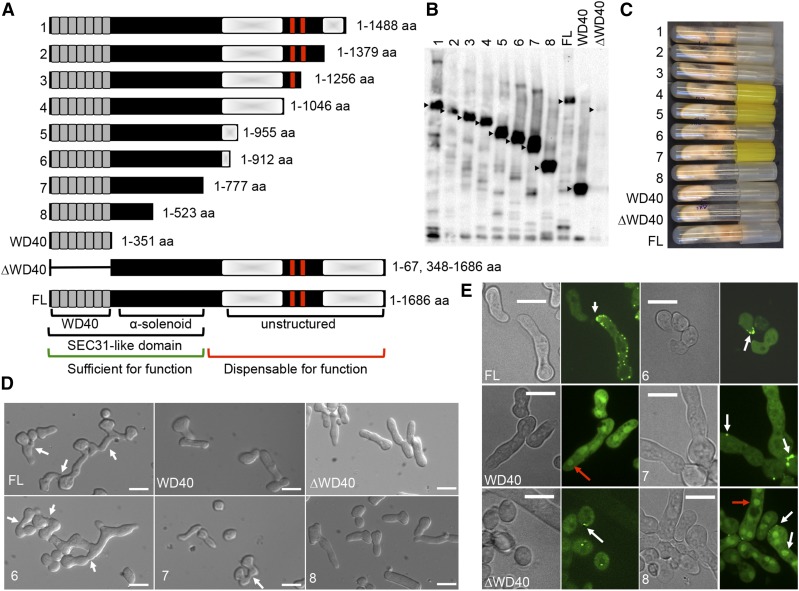

Figure 1.

Phenotypes and functional characterizations of truncated HAM-5–GFP proteins. (A) Schematic overview of the eight different truncated HAM-5 constructs (1–8), WD40 only version (1–351 aa), ∆WD40 version (1–67 and 348–1686 aa) and the full-length (FL) protein (1–1686 aa). The predicted WD40 domains are shown in gray and the putative coiled coil domains are shown as red bars. Shaded white boxes depict the two disordered regions with low complexity. The Sec31-like domain consists of the WD40 and the α-solenoid motifs found in S. cerevisiae Sec31 protein. The region of HAM-5 sufficient for function is marked by a green bar, while the region dispensable for function by a red bar. (B) Western blot of ∆ham-5 germlings bearing the eight different ham-5–gfp truncation constructs, FL ham-5–gfp, the wd40-gfp version (1–351 aa) or the ∆wd40-gfp (1–67 and 348–1686 aa) construct. Samples from 5-hr-old germlings were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibodies. Black triangles point to the HAM-5 protein bands of the correct size in the strains. (C) Growth phenotype of ∆ham-5 strains bearing the eight different truncated ham-5-gfp constructs, the wd40-gfp version, the ∆wd40, and the FL ham-5–gfp version on a Vogel’s minimal medium agar slant. (D) Germling fusion phenotypes of ∆ham-5 germlings bearing FL ham-5–gfp, wd40-gfp, ∆wd40-gfp, or the three shortest truncated ham-5–gfp constructs (constructs 6–8). White arrows point to germling pairs that have fused. Bar, 10 µm. (E) Cellular localization of the FL HAM-5–GFP protein, the WD40-GFP version (Jonkers et al. 2014), the HAM-5∆WD40, and the three shortest truncated HAM-5–GFP proteins (constructs 6–8). White arrows point to HAM-5–GFP puncta, red arrows to HAM-5–GFP accumulation in nuclei. Bar, 10 µm.

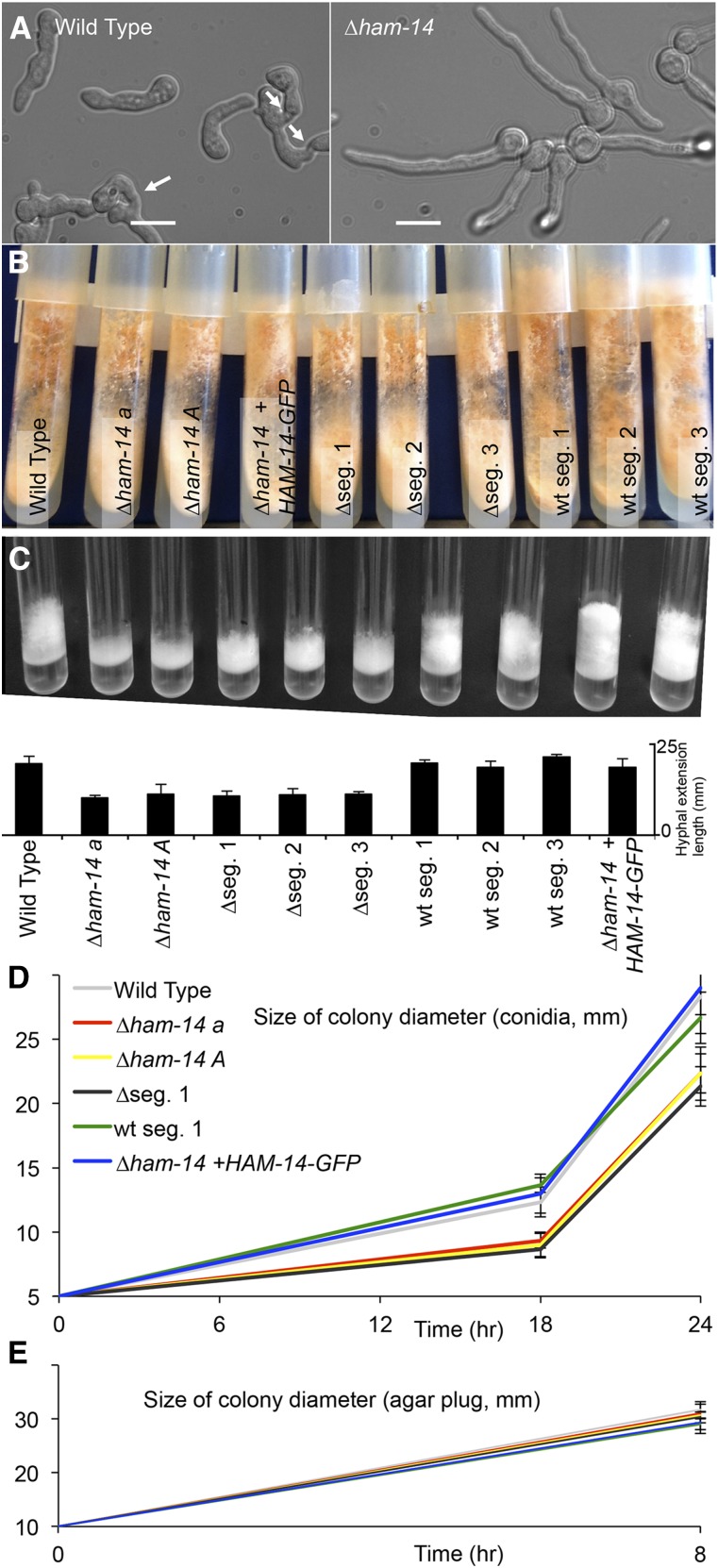

Figure 3.

Growth and fusion phenotypes of ∆ham-14 strains. (A) Chemotropic interactions and cell fusion are absent in ∆ham-14 germlings (right), in contrast to WT germlings (left). White arrows point to fusing germlings. Bar, 10 µm. (B) The ∆ham-14 mutants (∆ham-14 a; ∆ham-14 A; ∆seg.1; ∆seg.2 and ∆seg.3 (segregants from a WT × ∆ham-14 cross that carry a deletion of ham-14) do not show a phenotypic difference from WT in agar slant cultures, with the exception of slightly shorter aerial hyphae. (C) The ∆ham-14 strains (∆ham-14 a; ∆ham-14 A; ∆seg.1; ∆seg.2 and ∆seg.3) show reduced aerial hyphae extension as compared to WT, the ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp complemented strain and three segregants from a WT × ∆ham-14 cross that do not carry the ham-14 deletion. Top image shows macroscopic phenotypes and the bottom graph shows the hyphal extension length in millimeters for the different strains used. (D) Colony size measurements of WT (gray), the ∆ham-14 mat a (red) and ∆ham-14 mat A (yellow) mutants, the ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp complemented strain (blue), one WT segregant (WT seg.1, green) and one hygromycin-resistant segregant carrying the ΔNCU07238 deletion (∆seg.1, black). Plates were inoculated with 5 µl of 1 × 106 conidia/ml (top graph) for each strain or with a 10-mm diameter circular agar plug from the edge of an already established colony from each strain (E).

Fluorescence microscopy

Samples for fluorescence microscopy performed with GFP- and mCherry-tagged strains were prepared as described above. Images were taken using a Leica SD6000 microscope with a ×100 1.4 numerical aperature (N.A.) oil-immersion objective equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 spinning disk head and a 488-nm or 561-nm laser controlled by Metamorph software. Multiple pairs of interacting or noninteracting germlings were analyzed per experiment and representative pairs are shown for each strain. To count the number of germlings that show MAK-2–GFP puncta in noncommunicating germlings, random images were taken and MAK-2–GFP localization to puncta was counted. ImageJ software was used for image analysis (Schneider et al. 2012). Western blot band intensity was quantified in ImageJ by measuring the region of interest at a fixed size and then each value was subtracted from local background and normalized to the corresponding ponceau-stained lane.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting was performed as described (Jonkers et al. 2014). Immunoprecipitation and detection of GFP- or mCherry-tagged proteins was performed with mouse or rabbit anti-GFP antibodies (Roche or Life Technologies, respectively) and with mouse or rabbit anti-mCherry antibodies (monoclonal NBPI-96752 NovusBio or polyclonal 5993-100 Bio-vision, respectively).

Detection of phosphorylated MAK-1 and MAK-2 was carried out using antiphospho p44/42 MAP kinase antibodies (1:3000 dilution) (PhosphoPlus antibody kit; Cell Signaling Technology) as described (Pandey et al. 2004; Jonkers et al. 2014). Detection of phosphorylated HAM-14–GFP was performed using a purified mouse antiphosphoserine/threonine antibody, clone 22A (BD Biosciences).

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.

Results

Functional domains of HAM-5 are positioned at the N terminus

HAM-5 is a large scaffold protein consisting of 1686 aa. A predicted WD40 domain with seven helices is situated at the N-terminal side of the protein (amino acids 13–348, Figure 1A). Two predicted coiled coil domains (amino acids 1168–1190 and 1257–1286, Figure 1A) are located at the C terminus, imbedded in a large unstructured region of low complexity (amino acids 869–1686, Figure 1A). Full-length HAM-5 that was C-terminally tagged with GFP localized to the cytoplasm and to distinct cytoplasmic punctate structures. In cells undergoing chemotropic interactions and fusion, HAM-5 accumulates as puncta at CAT tips, which assemble and disassemble in a highly dynamic manner (Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014), which we term “fusion puncta.” This cytological feature is probably not due to overexpression of HAM-5, since puncta are also observed in hyphae when ham-5–gfp expression is driven by the ham-5 promoter, although the signal was too low to observe in germlings (Jonkers et al. 2014). In contrast to the full-length HAM-5–GFP, which was excluded from the nucleus, a GFP-tagged version of HAM-5 bearing only the WD40 domain (amino acids 1–351, Figure 1A) accumulated in the nucleus and localized diffusely to the cytoplasm (Jonkers et al. 2014). The ham-51–351-gfp construct also failed to complement the growth and fusion defects of the Δham-5 mutant. HAM-5 lacking the WD40 domain (∆WD40, Figure 1A) is also nonfunctional and is unstable in germlings and hyphae (Jonkers et al. 2014), but punctate localization was detected in conidia (Figure 1E, bottom left). These data indicate that the C terminus of HAM-5 (amino acids 351–1686) is required for function, for nuclear exclusion, and/or for localization to puncta.

To identify additional regions that control HAM-5 function and localization, we generated a series of truncated versions of ham-5 tagged with GFP (Figure 1). These GFP-tagged constructs were transformed into a wild-type strain at the his-3 locus and positive transformants were crossed with a ∆ham-5 strain (Table S1). Progeny carrying both the ∆ham-5 mutation as well as the desired construct at the his-3 locus were selected for analysis. Western blot analysis confirmed expression of each HAM-5–GFP truncation construct in the Δham-5 background with the expected protein sizes (Figure 1B).

Strains bearing the different ham-5–gfp deletion constructs were evaluated for fusion, growth phenotypes, and cellular localization via fluorescence microscopy. Strains bearing a ham-5 deletion exhibit a flat phenotype, which is caused by a reduction in extension of aerial hyphae (Aldabbous et al. 2010; Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014), a phenotype associated with germling and hyphal fusion mutants in N. crassa (Fu et al. 2011; Herzog et al. 2015). Although constructs that lack the WD40 domain or consist only of the WD40 domain failed to complement the flat and fusion phenotypes of a ∆ham-5 strain (Jonkers et al. 2014), full recovery of the growth phenotype (Figure 1C) and complementation of the fusion defect (ranging from ∼60 to 98% of WT level, Figure S1A and Figure 1D) was observed in strains bearing constructs 1–6. These data indicated that the terminal 576 aa are not essential for HAM-5 function. Sporadic fusion events, representing ∼10% of WT level (Figure S1A) and partial complementation of the flat phenotype were observed in the strain bearing the ham-51–777-gfp allele (no. 7) (Figure 1, C and D). However, strains bearing the final truncated allele, ham-51–523-gfp (no. 8) showed a similar flat phenotype and a complete absence of fusion, as observed with the ∆ham-5 strain (Figure 1, C and D and Figure S1A).

An α-solenoid motif was identified in the N terminus of HAM-5 (amino acids 351–777) via hydrophobic cluster analysis (Gaboriaud et al. 1987), xtalpred (Slabinski et al. 2007), and Phyre2 (Kelley et al. 2015) prediction methods (Figure 1 and Figure S8). α-Solenoid domains are found in other scaffold or cage-forming proteins (Stagg et al. 2007) and are involved in generating unique geometries that enable proteins to sort cargo and produce vesicles. Thus, the WD40 and the α-solenoid domain are both required for HAM-5 function.

HAM-5 functional domains are required for correct cellular localization and function during sexual reproduction

Microscopic investigation showed that ham-5–gfp truncated constructs 1–6 in a Δham-5 background showed a similar cellular localization pattern (puncta and cytoplasm) as the full-length HAM-5 protein (Figure 1; Figure S1). Moreover, these truncated versions of HAM-5–GFP showed oscillation to CATs during chemotropic interactions and colocalization with MEK-2–mCherry consistent with their ability to complement the fusion defect in the Δham-5 deletion strain (Figure S1B). For a ∆ham-5 strain bearing ham-51–77-gfp (no. 7), HAM-51–777-GFP localized to the cytoplasm and to puncta that also contained MEK-2–mCherry in both germlings and in hyphae (Figure 1E; Figure S1B), but oscillation was not observed as cell fusion was a rare event. In contrast to full-length HAM-5 and the ham-5 truncation constructs 1–7, HAM-51–523-GFP (no. 8) showed strong nuclear signal in both germlings and hyphae, but also localizated to puncta (that also contained MEK-2–mCherry) that were often at the cell periphery near contact sites with other germlings or conidia (Figure 1E; Figure S1B). However, oscillation, chemotropic interactions, and fusion were never observed in the Δham-5; his-3:: ham-51–523-gfp strains. Nuclear localization was also observed for HAM-51–351-GFP that contained the seven WD40 repeats (Figure 1E, WD40) (Jonkers et al. 2014), but no cytoplasmic puncta were observed. Thus, the domain required for nuclear exclusion of HAM-5 is situated between amino acids 523 and 777 and sequences important for localization of HAM-5 to puncta are between amino acids 351 and 523. Bioinformatics analyses failed to reveal a nuclear export signal for HAM-5, indicating that the nuclear import and export is determined by other factors.

Fusion mutants in N. crassa are often either unable to form female reproductive structures (protoperithecia) or are defective in sexual reproduction (Fu et al. 2011); the ∆ham-5 mutant is unable to form protoperithecia and is therefore female sterile (Aldabbous et al. 2010). As a male, the ∆ham-5 mutant is able to fertilize WT protoperithecia with production of viable ascospores (Jonkers et al. 2014). To determine whether the germling fusion phenotype of the ham-5 truncation constructs tracked with the sexual reproduction phenotype, the ∆ham-5, ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-5-gfp, ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-51–912-gfp (no. 6), ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-51–777-gfp (no. 7), and ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-51–523-gfp (no. 8) strains were inoculated onto Westergaards medium to induce protoperithecial development and subsequently fertilized with wild-type conidia of the opposite mating type. In accordance with the growth and germling fusion phenotype, the ∆ham-5 parental strain and the ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-51–351-gfp (WD40 domain only), the ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-51-67,348-1686-gfp (lacking the WD40 domain) and the ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-51–523-gfp (no. 8) strains were all female sterile. In contrast, the ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-5-gfp, the ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-51–912-gfp (no. 6), and the ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-51–777-gfp (no. 7) strains formed protoperithecia and produced viable ascospores in crosses with wild type. Thus, the functional domains required for germling fusion were also required for sexual development, suggesting similar roles for HAM-5 in these two distinct processes.

Previous biochemical approaches showed that the binding of HAM-5 to MAK-2 occurs through the WD40 domain and that binding to MEK-2 occurs at the region C-terminal to the WD40 domain (Jonkers et al. 2014). To further dissect the region of interaction between MEK-2 and HAM-5, heterokaryotic strains were constructed bearing ham-5-gfp or the ham-5-gfp truncation alleles with mek-2–mCherry. Consistent with their germling fusion and sexual reproduction proficiency, MEK-2–mCherry colocalized with HAM-5–GFP, HAM-51–912-GFP, HAM-51–777-GFP, and the nonfunctional ham-5 construct HAM-51–523-GFP to the cytoplasm and to puncta (Figure S1B), an identical localization pattern to that of homokaryotic strains bearing MAK-2 and HAM-5 (Jonkers et al. 2014). However, it is possible that the presence of HAM-5 in the heterokaryotic strains could affect cellular localization. Altogether, these data suggest that the amino acids between 351 and 523 of HAM-5 determine the localization of HAM-5 to puncta and the association of HAM-5 with MEK-2.

HAM-5 localization is not disrupted in other fusion mutants

Genes important for germling/hyphal fusion include genes of the MAK-2 MAP kinase pathway and upstream factors (Fu et al. 2011; Dettmann et al. 2014), members of the cell wall integrity (CWI) MAP kinase pathway (Fu et al. 2011, 2014), the STRIPAK complex (Simonin et al. 2010; Dettmann et al. 2013), the NADPH oxidation complex (Cano-Dominguez et al. 2008; Fu et al. 2011, 2014), a number of transcription factors (Aldabbous et al. 2010; Fu et al. 2011; Leeder et al. 2013), and genes encoding uncharacterized proteins (Fu et al. 2011, 2014). Previously, we showed that HAM-5–GFP localizes to puncta in ∆mak-2, ∆ham-7, and ∆ham-11 fusion mutants (Jonkers et al. 2014). We therefore asked whether strains carrying deletions of other genes required for germling fusion affected localization of HAM-5 by introducing ham-5–gfp into a set of 21 deletion strains (Table S3): five mutants for the STRIPAK complex (∆ham-2, ∆ham-3, ∆ham-4, ∆mob-3, and ∆ppg-1; Figure S2B), three mutants from the MAK-2 MAP kinase pathway and upstream factors (∆mek-2, ∆ste-20, and ∆ras-2; Figure S2C), two mutants from the NADPH oxidase complex (∆nox-1 and ∆ham-6; Figure S2D), three mutants from the CWI MAP kinase pathway (∆so, ∆mak-1, and ∆mik-1; Figure S2E), two transcription factor mutants (∆adv-1 and ∆pp-1; Figure S2F), and five additional mutants (∆ham-8, ∆ham-9, ∆ham-10, ∆amph-1, and ∆pkr-1; Figure S2G). One additional transcription factor (∆ada-3) mutant was reported to be fusion deficient (Fu et al. 2011). However, by segregation analyses, we determined that a deletion in ada-3 does not confer the germling/hyphal fusion-deficient phenotype in the original deletion strain. Without exception, HAM-5–GFP localized to puncta in all of the mutants and did not show accumulation in nuclei (Figure S2). These data suggest that HAM-5 itself may be sufficient for fusion puncta localization and nuclear exclusion, consistent with observation that HAM-5 forms homocomplexes (Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014).

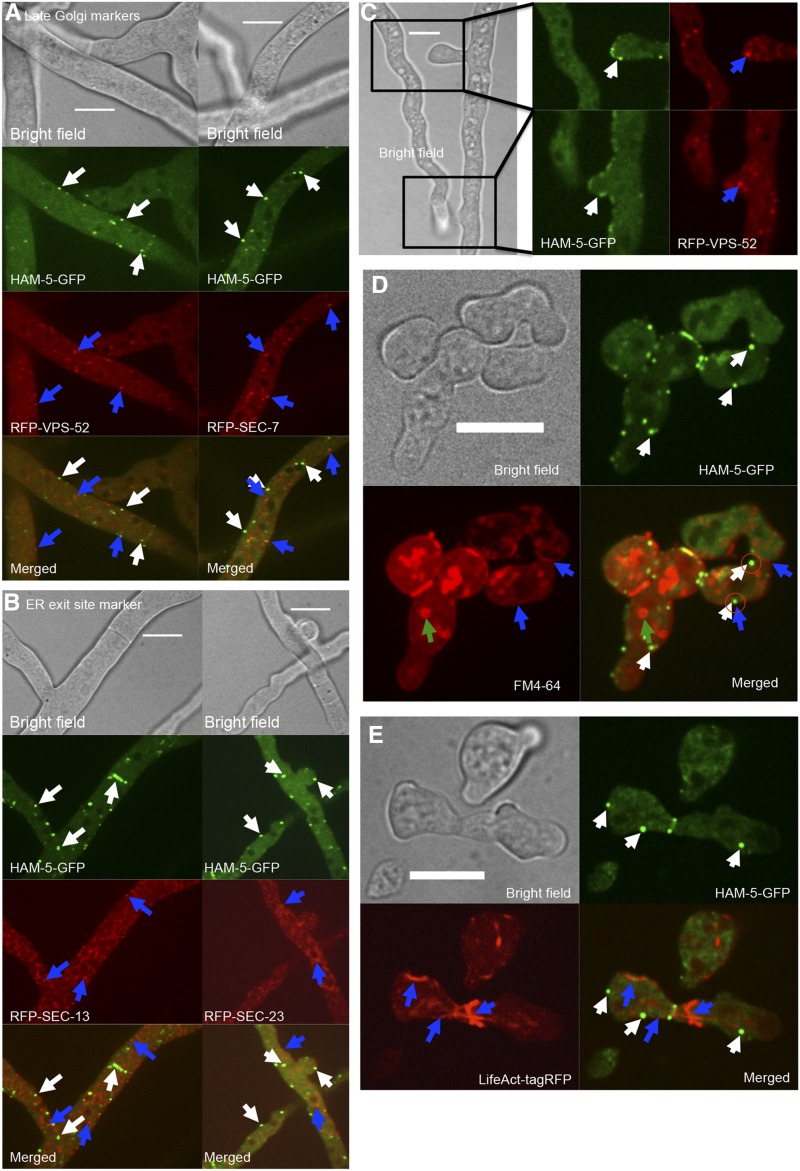

HAM-5 does not colocalize with vesicles or actin filaments

HAM-5 and components of the MAK-2 signal transduction complex show dynamic oscillation in germling tube tips, CAT tips, and to hyphal sites undergoing chemotropic interactions (Fleissner et al. 2009; Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). We therefore asked whether HAM-5–GFP puncta colocalized with any other cellular markers, including VPS-52 (Bowman et al. 2009) and SEC-7 (Sanchez-Leon et al. 2015) (late Golgi markers), SEC-23 and SEC-13 (ER-exit site markers), or RAB-4 and TLG-1 (early endosome markers) (Bowman et al. 2015) (Table S1; see Materials and Methods), or the endocytic dye FM4-64. Markers for the ER-exit site (SEC-23/SEC-13), late Golgi (SEC-7/VPS-52), or early endosome (RAB-4 or TLG-1) did not oscillate to tips of cells undergoing chemotropic interactions, nor did they colocalize with HAM-5–GFP puncta (Figure 2, A–C; Figure S3, File S2). Colocalization of HAM-5–GFP with FM4-64 was also not observed in either hyphae or in germlings with the exception of colocalization of HAM-5 puncta at the membrane of the CAT tip during oscillation and chemotropic interactions (Figure 2D; File S3).

Figure 2.

HAM-5–GFP fusion puncta do not colocalize with late Golgi, ER-exit sites, FM4-64 stained endosomes, or with actin filaments. (A) Cellular localization in heterokaryotic strains expressing HAM-5–GFP (his-3::ham-5-gfp) and RFP-tagged marker proteins VSP-52 (his-3::rfp-vps-52) or SEC-7 (his-3::rfp-sec-7) (Table S1). Top shows bright field image, the second panel shows GFP fluorescence, the third panel shows RFP fluorescence, and bottom shows the merged images. White arrows point to HAM-5–GFP puncta. Blue arrows point to RFP-VPS-52 or RFP–SEC-7 structures. Bar, 10 µm. (B) Heterokaryotic strains expressing HAM-5–GFP (his-3::ham-5-gfp) and RFP-tagged marker proteins SEC-13 (his-3::rfp-sec-13) and SEC-23 (his-3::rfp-sec-23) (Table S1). Top shows bright field image, the second panel shows GFP fluorescence, the third panel shows RFP fluorescence, and bottom shows merged images. White arrows point to HAM-5–GFP puncta. Blue arrows point to RFP–SEC-13 or RFP–SEC-23 structures. Bar, 10 µm. (C) Localization in the homing tips of heterokaryotic HAM-5–GFP (his-3::ham-5-gfp) and VSP-52 (his-3::rfp-vps-52) hyphae. Left shows bright field image, magnified panels show GFP fluorescent image (middle), and RFP fluorescent images (right) of two hyphal tips undergoing homing and fusion. White arrows point to HAM-5–GFP puncta at the tip. Blue arrows point to RFP–VPS-52 structures. Bar, 10 µm. (D) Cellular localization of HAM-5–GFP vs. the membrane selective dye FM4-64 in his-3::ham-5-gfp germlings. Top left image is bright field, top right image shows GFP fluorescence, bottom left shows red fluorescence and bottom right is the merged image. White arrows point to HAM-5–GFP puncta, blue arrows point to the FM4-64-stained cell membrane, green arrows to internal FM4-64-stained vesicles, and encircled are HAM-5–GFP puncta that show localization to the cell periphery. Bar, 10 µm. (E) Cellular localization of HAM-5–GFP and Lifeact-TagRFP in the homokaryotic strain (his-3::ham-5-gfp; Ptef-1::Lifeact-TagRFP-T::nat1). Top left image is bright field, top right is GFP fluorescence image, bottom left is RFP fluorescence image, and bottom right is the merged image. White arrows point to HAM-5–GFP puncta, blue arrows points to the LifeAct-tagRFP-marked actin cables. Bar, 10 µm.

Inhibitor studies have revealed that actin filaments are required for germling and hyphal fusion (Berepiki et al. 2010; Roca et al. 2010), although microtubules are not. To investigate whether HAM-5–GFP puncta colocalized with actin, we coexpressed HAM-5–GFP with Lifeact, an RFP-tagged small actin interacting protein (Delgado-Alvarez et al. 2010). As above, colocalization of HAM-5–GFP puncta undergoing oscillatory dynamics with actin filaments was not observed in germlings (Figure 2) or hyphae (Figure S3).

Identification of HAM-14 using a phosphoproteomics approach

HAM-5 was among the 3200 previously identified phosphopeptides identified as potential targets of MAK-2 (Jonkers et al. 2014). Here, we further analyzed this phosphoproteomic dataset to identify other targets of MAK-2 and potential members of the HAM-5/MAK-2 complex. Of these 3200 phosphopeptides, 217 phosphopeptides representing 144 proteins have a phosphorylated MAPK consensus site (P-X-S/T-P) (Parnell et al. 2005; Mok et al. 2010) (File S1). Twenty-eight of these 217 peptides showed a lower abundance after MAK-2 kinase inhibition (>1.25-fold change), (Table S4), but because of variability in samples, the difference was not statistically significant (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). Because these proteins have a MAPK consensus site and some evidence for dependence on MAK-2 for phosphorylation, we investigated the germling fusion phenotype for each deletion mutant for these 28 proteins (see Materials and Methods). Strains carrying deletions for 12 of these 28 proteins had previously been evaluated for germling fusion (Table S4). Strains carrying a deletion for 7 of the 28 proteins were either not available or available only as a heterokaryon. Of the 9 additional deletion strains (ΔNCU00277, ΔNCU01728, ΔNCU02024, ΔNCU03200, ΔNCU03539, ΔNCU07192, ΔNCU07238, ΔNCU08962, and ΔNCU09860; Table S4), only the ΔNCU07238 strain showed a complete absence of germling fusion (Figure 3A). The asexual spores of ΔNCU07238 germinated normally as compared to WT (Figure 4A), but in contrast to WT germlings, which redirect their growth to each other and fuse, the ΔNCU07238 germ tubes grew straight, showed no chemotropic interactions, and did not undergo cell fusion (Figure 3B). Because of this defect, we named NCU07238 hyphal anastomosis-14 (ham-14). Cosegregation analysis performed with six WT progeny and six ∆ham-14 progeny showed that the six hygromycin B-resistant strains that carried the hygromycin marker at the ∆NCU07238 locus were germling fusion defective with an identical phenotype to the parental ∆NCU07238 strain. All six hygromycin B-sensitive strains were fully germling fusion competent with a phenotype comparable to the WT parental strain (Figure S4A). In addition, the germling fusion defect in Δham-14 mutant was complemented by the introduction of a ham-14–gfp construct (Table S1, Figure S5, A and B).

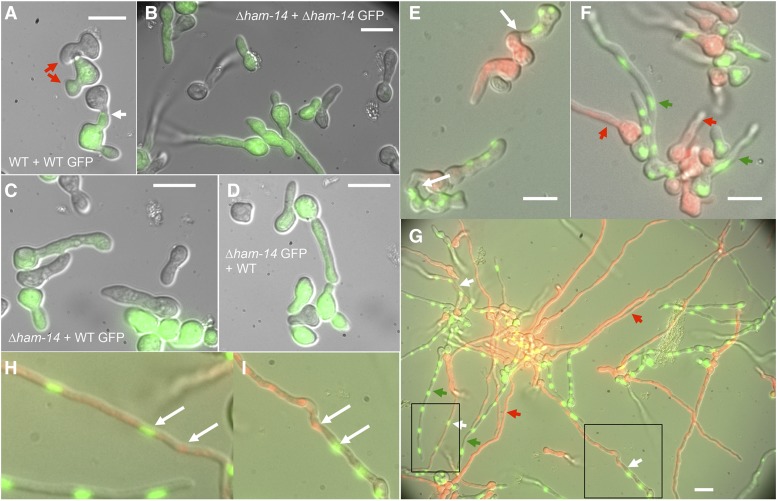

Figure 4.

Absence of fusion between WT and ∆ham-14 germlings. (A) GFP-fluorescent WT cells (green) bearing MAK-2–GFP grow toward and fuse with an otherwise isogenic nonfluorescent wild-type germling (WT GFP + WT). White arrow shows fusion point and red arrow shows two germlings growing toward each other. Bar, 10 µm. (B) No germling fusion is observed between GFP-fluorescent ∆ham-14; his-3::mak-2-gfp germlings in proximity to otherwise isogenic nonfluorescent ∆ham-14 cells (∆ham-14 GFP + ∆ham-14). (C) No germling fusion is observed between nonfluorescent ∆ham-14 and GFP-fluorescent WT (his-3::mak-2-gfp) germlings when in proximity to each other (∆ham-14 + WT GFP). Note that one ∆ham-14 germling by chance touches the WT germling but does not fuse. Bar, 10 µm. (D) No fusion is observed between nonfluorescent WT and GFP-fluorescent ∆ham-14; his-3::mak-2-gfp germlings when in proximity to each other (WT + ∆ham-14 GFP). Bar, 10 µm. (E) WT (his-3::H1-gfp) germlings communicating with WT (his-3::H1-dsRED) germlings (note that the red fluorescence of the H1-DsRED is also visible in vacuoles throughout the germling). White arrows point to communicating or fusing germlings. Bar, 10 µm. (F) Chemotropic interactions and cell fusion are not observed between ∆ham-14; his-3::H1-dsRED and ∆ham-14; his-3::H1-gfp germlings. Red arrows point to germlings that only have DsRed-tagged nuclei and green arrows point to germlings that only have GFP-tagged nuclei and have not fused. (G) Fusion event between ∆ham-14; his-3::H1-dsRED and ∆ham-14; his-3::H1-gfp hyphae after 7-hr incubation. White arrows point to fused hyphae in which both H1-GFP and H1-DsRED are visible (see magnified boxed areas H and I in which white arrows point to H1-GFP and H1-DsRED nuclei). Red arrows point to hyphae that have only DsRed-tagged nuclei and green arrows point to hyphae that have only GFP-tagged nuclei. Bar, 10 µm.

The macroscopic phenotype of the ∆ham-14 strain was different from other fusion-defective mutants because the culture was not flat, for example, in ∆ham-5 mutants (Figure 1C). In an agar slant tube, the ∆ham-14 strain had nearly normal aerial hyphae growth and exhibited normal conidiation (Figure 3B). However, when grown in tubes with liquid media, aerial hyphae growth was significantly reduced in the ∆ham-14 strains by almost 50% as compared to WT and the complemented strain (P < 0.01, Student’s t-test; Figure 3C).

The ability of germlings to undergo fusion results in faster colony development (Richard et al. 2012). To test whether Δham-14 mutants also showed a lag in colony establishment, we performed a growth experiment in which we measured colony size after inoculating either a drop of conidia (5 µl of a 1 × 106 conidia/ml solution) vs. growth rate when a hyphal plug (10-mm size) was used for the initial inoculum. These experiments showed that the ∆ham-14 strains grown from conidia initially formed a smaller colony (P < 0.05, Student’s t-test) as compared to the wild-type strain, but had a similar growth rate after 18 hr (Figure 3D). However, when a colony was initiated from an agar plug from an established colony, the colony size reached by all strains over the time course was identical (Figure 3E). The smaller colony size of the ∆ham-14 mutant was not due to a conidial germination defect (Figure S4 and data not shown). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that strains unable to undergo germling fusion (and thereby unable to cooperate) are restricted in colony establishment size as compared to those strains capable of germling fusion.

The Δham-14 mutant is germling fusion deficient, but can undergo hyphal fusion

The growth phenotype of the ∆ham-14 mutant resembles that of the ∆ham-11 mutant, another germling fusion mutant that does not have a flat phenotype (Leeder et al. 2013). ∆ham-11 is unique among germling fusion mutants because it cannot undergo germling fusion with itself, but is capable of doing so with WT germlings (Leeder et al. 2013). We therefore mixed ∆ham-14 germlings that expressed MAK-2–GFP (∆ham-14; his-3::mak-2-gfp; Table S1) with ∆ham-14 and WT germlings. We also performed the reciprocal test where wild-type germlings bearing mak-2–gfp were mixed with ∆ham-14 and WT germlings. As expected, no chemotropic interactions and fusion events were observed when ∆ham-14; his-3::mak-2-gfp germlings were paired with ∆ham-14 germlings (Figure 4B). However, unlike the Δham-11 mutants (Leeder et al. 2013), the WT his-3::mak-2-gfp germlings did not grow toward or fuse with ∆ham-14 germlings, even if two germlings touched by chance (Figure 4C). The ∆ham-14 his-3::mak-2-gfp cells also did not grow toward or fuse with WT germlings (Figure 4D). However, normal chemotropic interactions and cell fusion between WT his-3::mak-2-gfp and WT germlings was observed (Figure 4A).

The ∆ham-11 mutant also differs from other fusion mutants in that it is female fertile (Leeder et al. 2013). Similar to ∆ham-11 mutant, the ∆ham-14 mutant was also female fertile, forming fertile perithecia with viable ascospores. One possibility of why ∆ham-14 lacks a flat phenotype and is not female sterile might be that it can undergo hyphal fusion, which occurs at a different developmental time point than germling fusion. We investigated the ability of the ∆ham-14 mutant to undergo germling and hyphal fusion by mixing ∆ham-14 germlings bearing a green fluorescent nuclear marker (H1-GFP) with ∆ham-14 germlings bearing a red fluorescent nuclear marker (H1-dsRed) (Table S1) as compared to WT strains bearing H1-GFP or H1-dsRED. In contrast to WT, in which germling communication was ubiquitously observed after 4 hr (Figure 4E), neither communication nor germling fusion was observed in the ∆ham-14 cells (Figure 4F). However, after 7 hr, we detected hyphal fusion events in ∆ham-14 (Figure 4, G–I), as evidenced by the hyphal segments that contained both H1-GFP and H1-dsRed fluorescent markers (Figure 4, G–I). Although fusion events in ∆ham-14 hyphae were observed, quantification of these events compared to wild-type colonies was not possible due to the 3D aspect of an interconnected fungal colony and because fusion occurs at all stages of growth (germlings and hyphae). The fact that hyphal fusion events were observed in the ∆ham-14 strains, unlike other fusion mutants, indicates that HAM-14 is only specifically and absolutely required for germling fusion.

HAM-14–GFP localizes to the cytoplasm and to puncta that do not oscillate to cell tips during fusion

ham-14 encodes a hypothetical protein of 606 aa with two predicted coiled coil domains (amino acids 112–156 and 168–278, Figure 5A). HAM-14 follows a similar conservation pattern as HAM-5 and is restricted to fungi belonging the Pezizomycotina, the largest subphylum of filamentous Ascomycetes. Eight HAM-14 phosphopeptides were detected in our phosphoproteomics experiments (Jonkers et al. 2014); one phosphopeptide has a MAPK consensus site, while two additional phosphopeptides have a degenerate MAPK consensus site (pS/pT-P). From a subsequent phosphoproteomic study on N. crassa hyphal cultures (Xiong et al. 2014), an additional 33 phosphopeptides were identified for HAM-14. Thus, 24 possible unique phosphosites are present in HAM-14. None of the phosphosites were present in the predicted coiled coil domains (amino acids 112–278) (Figure 5A).

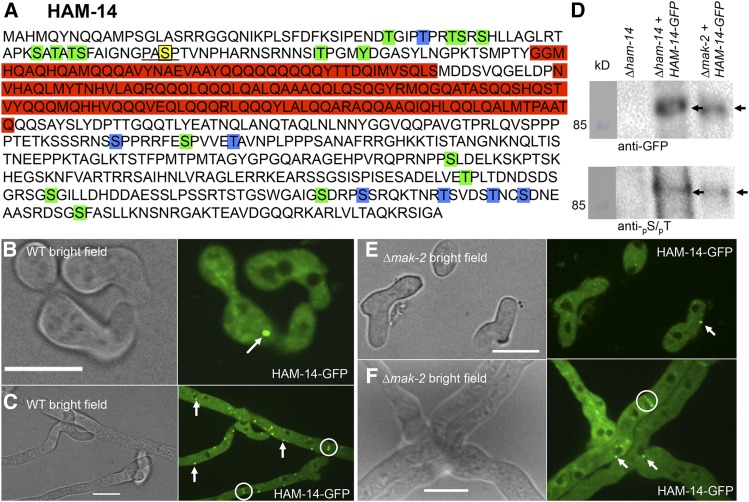

Figure 5.

HAM-14 is a phosphoprotein that localizes to the cytoplasm, occasionally to puncta, and is excluded from the nucleus. (A) Protein sequence of HAM-14. The red boxes represent predicted coiled coil domains. The MAPK phosphorylation site (amino acid S73) is marked by a yellow box and underlined. The 23 additional phosphorylation sites (T39, T43, T46, S47, S49, S61, S63, T65, S66, S73, T91, Y95, S345, S352, T357, S436, T496, S510, S538, S542, T550, T555, and S558) are marked in blue (Jonkers et al. 2014) and green boxes (Xiong et al. 2014). (B) HAM-14–GFP localizes in the cytoplasm and occasional puncta in communicating germlings (white arrow). Bar, 10 µm. (C) In hyphae, HAM-14–GFP localizes to the cytoplasm, puncta (white arrows), and septa (white encircled). Bar, 10 µm. (D) Top shows a Western blot of protein samples from germlings of ∆ham-14, ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp, and ∆mak-2; his-3::ham-14-gfp strains (Table S1), which were subjected to immunoprecipitation and Western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies (black arrow, 93 kDa). Bottom shows a Western blot of identical anti-GFP immnoprecipitated samples probed with an antibody that specifically detects phosphorylated serine or threonine residues (black arrow) (E) HAM-14–GFP localizes in ∆mak-2 germlings to the cytoplasm and occasional puncta (white arrow). Bar, 10 µm. (F) HAM-14–GFP localizes in ∆mak-2 hyphae to the cytoplasm, occasional puncta (white arrows), and septa (white encircled). Bar, 10 µm.

To investigate the localization of HAM-14 during germling fusion, we C-terminally tagged ham-14 with GFP and mCherry and transformed a ∆ham-14 strain at the his-3 locus with either a Pccg1-ham-14-gfp, a Pham14-ham-14-gfp, a Ptef1-ham-14-gfp, or a Ptef1-ham-14-mCherry construct (Table S1). All constructs complemented the germling fusion defect of the ∆ham-14 strain to levels comparable to WT, including the ham-14 construct driven by its native promoter (Figure S5B). The ham-14 constructs driven by either the tef-1 or ccg-1 promoters and tagged with either GFP or mCherry showed cytoplasmic localization, localization to puncta and to septa, although the tef-1-driven HAM-14–GFP signal was higher (Figure 5B; Figure S5, C and D; File S4). Western blot analyses of HAM-14–GFP also showed increased proteins levels in both the ccg-1 and tef-1-driven ham-14 constructs, consistent with microscopy results. However, the Pham14-ham-14-gfp construct gave a very low signal that prevented assessment of cellular localization (Figure S5E).

In the Ptef-1-ham-14-gfp germlings undergoing fusion, HAM-14–GFP was present in the cytoplasm and sometimes appeared in puncta (Figure 5B). These puncta did not oscillate to CAT tips, nor did they show dynamic assembly and disassembly similar to HAM-5/MAK-2 puncta during chemotropic interactions. (Fleissner et al. 2009; Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). In germlings undergoing chemotropic interactions and fusion the HAM-14–GFP puncta randomly appear and disappear near the nucleus or the cell membrane (File S4). In hyphae, HAM-14–GFP puncta are more abundant and localized near the nucleus, at the membrane, in the cytoplasm, and at the septa (Figure 5C and File S5). Whether the puncta are intrinsic structures of HAM-14 or whether they are a result of overexpression from either the tef-1 or ccg-1 promoters is currently unclear. Since cellular localization of HAM-14 in the Pham14-ham-14-gfp strain could not be determined, it is possible that puncta observed in the Ptef-1-ham-14-gfp strains are not associated with or required for HAM-14 function. In heterokaryotic strains expressing both the nuclear marker histone H1-dsRed and ham-14-gfp, nonoverlapping fluorescence in germlings or hyphae was observed (Figure S6A), indicating that HAM-14 is excluded from the nucleus, similar to HAM-5, MEK-2, NRC-1, and SOFT (Fleissner et al. 2009; Dettmann et al. 2012, 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014).

To assess whether HAM-14 is a phosphorylation target of MAK-2, as indicated by the phosphoproteomics data, we introduced ham-14–gfp into a ∆mak-2 strain (Table S1) and determined its phosphorylation status during germling fusion. HAM-14–GFP was immunoprecipitated from 5-hr-old ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp germlings and ∆mak-2; his-3::ham-14-gfp germlings (Table S1) with anti-GFP antibodies (Figure 5D, top). Each sample was further assayed for phosphorylation status using Western blot analysis with antiphosphoserine/phosphothreonine antibodies (Figure 5D, bottom). The results showed HAM-14–GFP from Δham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp and ∆mak-2; his-3::ham-14-gfp cells was phosphorylated (Figure 5D, see black arrows). Since HAM-14–GFP has multiple phosphoserine and phosphothreonine sites, it is probable that other kinases act on HAM-14.

To further test the role of MAK-2 and HAM-5 on HAM-14 function, we assessed the cellular localization of HAM-14–GFP in ∆mak-2, Δham-5, and WT germlings (Figure 5, E and F; Figure S5, C and D). HAM-14–GFP in the ∆mak-2 and Δham-5 mutants appeared in the cytoplasm and in occasional puncta, a localization pattern identical to WT cells. In contrast, MAK-2–GFP shows only cytoplasmic localization in ∆ham-5 cells and is absent from puncta (Jonkers et al. 2014).

HAM-14 binds the MAP kinase cascade members MEK-2 and MAK-2

HAM-5 binds MEK-2 and MAK-2 and recruits them to puncta that show dynamic oscillation during the chemotropic interactions prior to cell fusion in both germlings and hyphae (Jonkers et al. 2014). To test the possibility that HAM-14 binds MAK-2, MEK-2, HAM-5, or SOFT, we constructed heterokaryotic strains bearing HAM-14–mCherry and either HAM-5–GFP, MAK-2–GFP, SOFT–GFP, or free GFP (Table S1; Figure 6A), in addition to the reciprocal heterokaryotic strains bearing HAM-14–GFP and either MEK-2–mCherry, MAK-2–mCherry, or SOFT–mCherry (Table S1; Figure 6A). Samples of MEK-2–mCherry and either HAM-5–GFP or free GFP were included as positive and negative controls, respectively (Figure 6A).

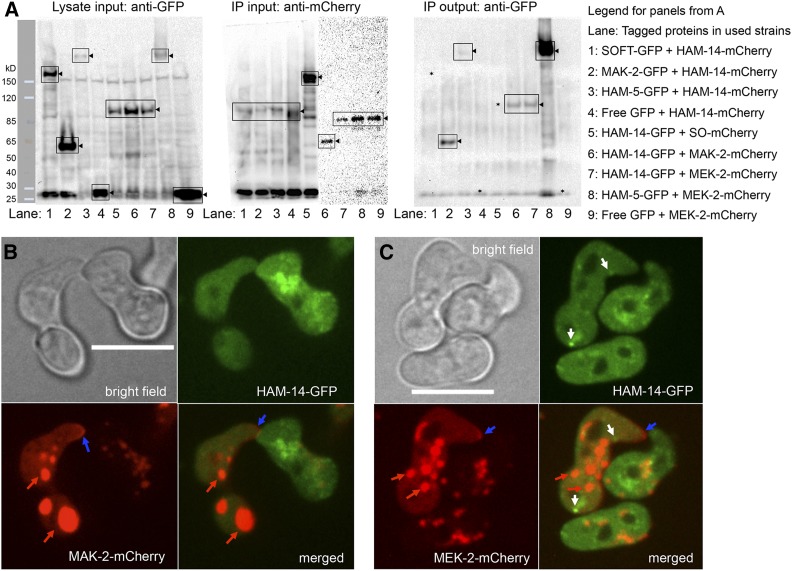

Figure 6.

Interaction of HAM-14–GFP with MAK-2–mCherry and MEK-2–mCherry. (A) Left shows Western blot of input protein samples from 5-hr-old germlings probed with anti-GFP antibodies (lane 1, SOFT-GFP; lane 2, MAK-2–GFP; lanes 3 and 8, HAM-5–GFP; lanes 4 and 9, free GFP; and lanes 5–7, HAM-14–GFP). Black triangles point to the bands of interest (boxed) and ladder on the left shows protein marker. Middle consists of two Western blots showing anti-mCherry immunoprecipitated input protein samples from 5-hr-old germlings probed with anti-mCherry antibodies (lanes 1–4, HAM-14–mCherry; lane 5, SOFT-mCherry; lane 6, MAK-2–mCherry; and lanes 7–9, MEK-2–mCherry; black triangles point to the bands of interest). Right is a Western blot of protein samples immunoprecipitated by anti-mCherry antibodies and subsequently probed by anti-GFP antibodies. Lane 2, MAK-2–GFP; lanes 3 and 8, HAM-5–GFP; lanes 6 and 7, HAM-14–GFP; black triangles point to the bands of interest. Lanes lacking co-immunopreciptation signal (1, 4, and 5) are marked with *. Legend on the right shows strains/lanes. (B) HAM-14–GFP and MAK-2–mCherry localization during germling fusion. Top is a bright field image (Bar, 10 µm); top right shows HAM-14–GFP fluorescence; bottom left shows MAK-2–mCherry fluorescence; and bottom right shows the composite of HAM-14–GFP and MAK-2–mCherry fluorescent images. Blue arrows point to MAK-2–mCherry crescent at the tip. Red arrows point to mCherry fluorescence visible in vacuoles, which has been observed previously in germlings (Jonkers et al. 2014). (C) Composite of HAM-14–GFP and MEK-2–mCherry localization during germling fusion. Top left is a bright field image (Bar, 10 µm); top right shows HAM-14–GFP fluorescence; bottom left shows MEK-2–mCherry fluorescence; and bottom right shows the composite of HAM-14–GFP and MEK-2–mCherry fluorescent images. White arrows point to HAM-14–GFP fluorescent puncta, blue arrows point to MEK-2–mCherry crescent at the tip, and red arrows point to mCherry fluorescence visible in vacuoles.

After protein extraction, all GFP-tagged samples were detected by Western blot (Figure 6A, left blot). After immunoprecipitation with anti-mCherry, all mCherry-tagged proteins were also detected (Figure 6A, middle blots). When the HAM-14–mCherry immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-GFP, we identified MAK-2–GFP and to a lesser extent, HAM-5–GFP, indicating that the interaction between HAM-5 and HAM-14 was specific, but weak (lane 3 Figure 6A, right blot). No free GFP above background or SOFT–GFP was detected in the HAM-14–mCherry immunoprecipitates (lanes 1–4 Figure 6A, right blot). When either SOFT–mCherry, MEK-2–mCherry, or MAK-2–mCherry immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-GFP antibodies, HAM-14–GFP was detected in the MEK-2–mCherry and MAK-2–mCherry samples, but not in the SOFT–mCherry sample (lanes 5–7 Figure 6A, right blot). As controls, HAM-5–GFP, but not free GFP (lanes 8 and 9 Figure 6A, right blot) was detected above background in the MEK-2–mCherry immunoprecipitates (lanes 8 and 9, Figure 6A). These data support physical interaction between HAM-14 and the MAK-2 complex, as represented by MAK-2 and HAM-5, and could indicate that HAM-14 is a kinase substrate of MAK-2 when both are part of the complex.

In germlings, HAM-14–GFP did not colocalize with MAK-2/MEK-2 puncta that show dynamic oscillation during chemotropic interactions (Figure 6, B and C; File S6), although all three of these proteins also showed cytoplasmic localization. Similarly, in hyphae of heterokaryotic strains expressing HAM-14–GFP and MAK-2–mCherry or MEK-2–mCherry, no overlapping fluorescence of HAM-14–GFP puncta with MAK-2–mCherry or MEK-2–mCherry was observed (Figure S7, A and B), although all three proteins also localized to septa. Overlapping fluorescence of HAM-14–GFP puncta with SOFT–mCherry, which also shows dynamic oscillation in cells undergoing chemotropic interactions (Fleissner et al. 2009) was also not observed (Figure S7C, File S7). These observations suggest that the biochemical interaction between HAM-14 and MAK-2/MEK-2 might be due to cytoplasmic interactions.

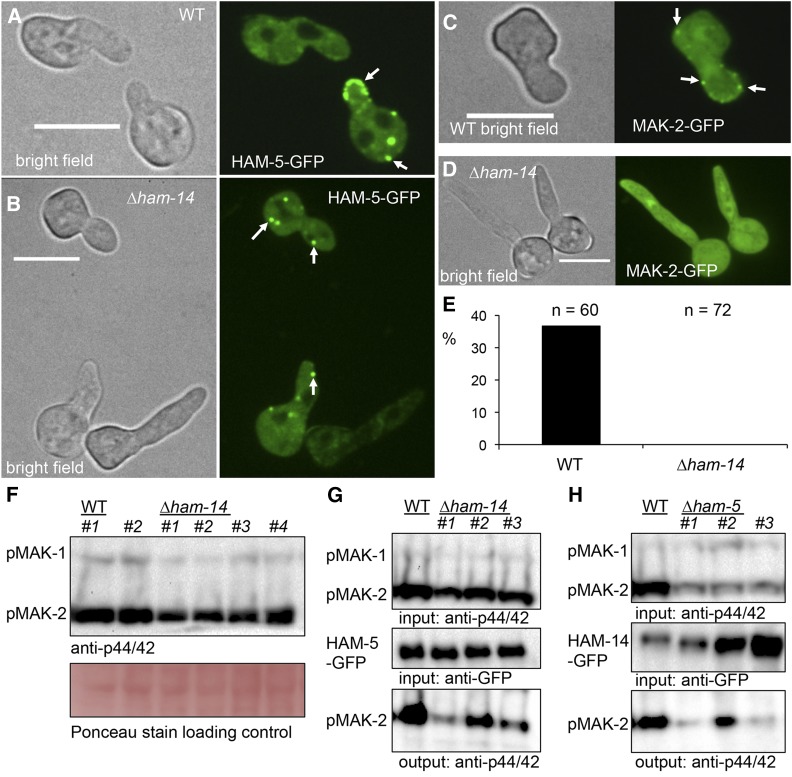

The coimmunopreciptation data indicated that HAM-14 physically interacts with MAK-2/MEK-2 and HAM-5 (MAK-2 signaling complex) (Figure 6A). To further dissect the effect of a deletion of ham-14 on HAM-5 and MAK-2 localization and dynamics, we assessed localization and dynamics of HAM-5 and MAK-2 in a Δham-14 mutant. The localization of HAM-5–GFP in ∆ham-14 germlings was indistinguishable from HAM-5–GFP in WT germlings, with the exception that dynamic oscillation of HAM-5 puncta was never observed in ∆ham-14 germlings (Figure 7, A and B). However, when MAK-2–GFP was expressed in ∆ham-14 strains, no MAK-2–GFP was found in puncta under any conditions, in contrast to MAK-2–GFP localization in wild-type strains, where puncta were observed even in strains not undergoing chemotrophic interactions (Figure 7, C and D). For example, when his-3::mak-2-gfp and ∆ham-14; his-3::mak-2-gfp germlings were screened for MAK-2–GFP localization, ∼37% of the his-3::mak-2-gfp cells not undergoing chemotropic interactions displayed MAK-2–GFP puncta, while MAK-2–GFP puncta were not observed in the communication defective ∆ham-14 germlings (Figure 7E). These data suggest HAM-14 plays a role in assembling MAK-2 but not HAM-5, into MAK-2 signaling complexes.

Figure 7.

HAM-14 is involved in formation of HAM-5 and MAK-2 protein complexes. (A) HAM-5–GFP localizes in fusing WT germlings to the cytoplasm and puncta (white arrows). Note localization of HAM-5–GFP to tip of cell undergoing chemotropic interactions. Left shows a bright field image; right shows GFP fluorescence. Bar, 10 µm. (B) HAM-5–GFP localizes to the cytoplasm and to puncta (white arrow) in ∆ham-14 germlings, which are fusion defective. Left shows a bright field image; right shows GFP fluorescence. Bar, 10 µm. (C) MAK-2–GFP in WT germlings not undergoing chemotropic interactions localizes to the nucleus, cytoplasm, and puncta that mostly appear at the periphery of the cell (white arrows). Left shows a bright field image; right shows GFP fluorescence. (D) In the ∆ham-14 mutant, MAK-2–GFP localization is cytoplasmic and nuclear but no puncta were observed. Bar, 10 µm. Left shows a bright field image; right shows GFP fluorescence. (E) Percentage of noncommunicating cells that display MAK-2–GFP puncta in WT vs. ∆ham-14 germlings, n = number of noncommunicating germlings screened. (F) Western blot of protein samples from 5-hr-old (his-3::ham-5-gfp) germlings from two WT strains and four independent ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-5-gfp strains probed with anti-p42/44 antibodies, which recognize phosphorylated MAK-1 and MAK-2. (G) Coimmunoprecipitation experiments showing an interaction between HAM-5–GFP and phosphorylated MAK-2 in WT (his-3::ham-5-gfp) germlings, and between MAK-2 and HAM-5–GFP in three independent ∆ham-14 strains (∆ham-14; his-3::ham-5-gfp). Top is a Western blot of input protein samples probed with anti-p42/44 antibodies (MAK-2, 40.8 kDa and MAK-1, 46.7 kDa). Middle is a Western blot of input anti-GFP immunoprecipitated HAM-5–GFP proteins samples probed with anti-GFP antibodies (HAM-5–GFP, 210 kDa). Bottom is a Western blot of anti-GFP immunoprecipitated protein samples probed with anti-p42/44 antibodies. (H) Coimmunoprecipitation experiment assessing an interaction between HAM-14–GFP and phosphorylated MAK-2 in complemented ∆ham-14 germlings (∆ham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp) (labeled WT) vs. three individual ∆ham-5 strains (∆ham-5; his-3::ham-14-gfp). Top is a Western blot of input protein samples probed with anti-p42/44 antibodies. Note that MAK-2 shows less phosphorylation in the ∆ham-5 strains as compared to WT germlings (Figure S7F) (Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). Middle is a Western blot of input anti-GFP immunoprecipitated protein samples probed with anti-GFP antibodies (HAM-14–GFP, 94 kDa). Bottom is a Western blot of output anti-GFP immunoprecipitated protein samples probed with anti-p42/44 antibodies that recognize phosphorylated MAK-2.

MAK-2 and HAM-5 interact in ∆ham-14 mutants and MAK-2 and HAM-14 interact in ∆ham-5 mutants

Since coimmunoprecipitation experiments revealed that HAM-14 interacted with MAK-2/MEK-2 and HAM-5, but that MAK-2 failed to localize to puncta in Δham-14 cells, we hypothesized that HAM-14 may play a role in the interaction between MAK-2/MEK-2 and HAM-5. This interaction is important since HAM-5 recruits the MAP kinase cascade members to fusion puncta, which oscillate at CAT tips and hyphae undergoing chemotropic interactions (Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). We first examined MAK-2 phosphorylation levels (which reflect upstream activation events) in WT vs. ∆ham-14 germlings. Western blots were probed with anti-p44/42 antibodies, which specifically recognize phosphorylated MAK-2 (Pandey et al. 2004). As seen with other fusion mutants (Dettmann et al. 2012, 2014; Fu et al. 2014), phosphorylated MAK-2 was present in ∆ham-14 strains, but to a lower level (61.2 ±12.8%, P < 0.05, Student’s t-test) than in WT germlings (Figure 7, F and G; Figure S7, D and E).

Second, we evaluated phosphorylation of MAK-2 that was immunoprecipitated with HAM-5 in ∆ham-14 germlings, as compared to wild-type cells. HAM-5–GFP was immunoprecipitated from WT (his-3::ham-5-gfp) and from ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-5-gfp germlings (Figure 7G; Figure S7G) and the immunoprecipitated proteins were subsequently probed with anti-p44/42 MAPK antibodies. In all three independent ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-5-gfp samples, phosphorylated MAK-2 was still present (Figure 7G), indicating that HAM-14 is not essential for the biochemical interaction between HAM-5 and phosphorylated MAK-2.

We then assessed the levels of HAM-14–GFP and its interaction with phosphorylated MAK-2 in three independent ∆ham-5 strains expressing HAM-14–GFP (∆ham-5; his-3::ham-14-gfp) (Table S1). In the ∆ham-5; his-3::ham-14-gfp germling samples, the base level of phosphorylated MAK-2 was lower than in WT (47.3 ± 5.7%) or ∆ham-14; his-3::ham-14-gfp cells (Figure 7H; Figure S7F). Nevertheless, in each of the ∆ham-5 strains, phosphorylated MAK-2 coimmunoprecipitated with HAM-14–GFP (Figure 7H). These data indicate that HAM-5 is also not essential for the interaction between HAM-14 and phosphorylated MAK-2. However, unlike the levels of HAM-5–GFP in the three independent ∆ham-14 strains, which are very similar to the levels of HAM-5–GFP in the WT strain (Figure 7G; Figure S7G), the levels of HAM-14–GFP in the ∆ham-5 strains were variable (Figure 7H; Figure S7H), with increased protein levels in two of the ∆ham-5 strains. Altogether, mutations in ham-14 and ham-5 reduce the level of phosphorylated MAK-2, suggesting that both HAM-5 and HAM-14 are involved in the MAK-2 complex formation and might depend on each other for function, protein levels, and/or localization.

Discussion

The MAK-2 signaling complex, which includes the filamentous ascomycete-specific scaffold protein, HAM-5, assembles and disassembles at CAT tips and fusion hyphae during chemotropic interactions (Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). These distinct fusion puncta composed of the MAK-2/HAM-5 complex are also present in other parts of the cell, including at the nuclear envelope, in the cytoplasm, and along the cell membrane (Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014), where they undergo coordinated assembly and disassembly in both the cytoplasm and at the fusion tip during chemotropic interactions. This observation is especially striking in fusion hyphae, where assembly of the MAK-2/HAM-5 complexes is coordinated during chemotropic interactions through several hyphal compartments and over several hundred μm (Jonkers et al. 2014). Here we show that the N-terminal 523 aa of HAM-5 are essential for correct localization to these puncta, and which also include MAK-2 complex components (Figure S1). An additional 250 aa of HAM-5 are essential for nuclear exclusion. Nuclear exclusion of HAM-5 was correlated with function during both cell fusion and sexual reproduction, suggesting the possibility that mislocalization of HAM-5 contributes to the inability to coordinate these developmental processes. We also identified a new fusion protein, HAM-14, which physically interacts with MAK-2, MEK-2, and HAM-5. Importantly, although HAM-5 localizes to puncta in the Δham-14 mutant, MAK-2 does not. These data indicate that HAM-14 may play a role in the recruitment of MAK-2 to the HAM-5 puncta, which is important in the downstream signaling that mediates subsequent chemotropic interactions and cell fusion. Further biochemical studies with HAM-5 and HAM-14, including differentiating phosphorylated and unphosphorylated NRC-1, MEK-2, and MAK-2 is needed to order the sequence of events associated with assembly/disassembly of fusion puncta during chemotropic interactions.

All the known components of the MAPK pathway (STE-50, NRC-1, MEK-2, MAK-2, and HAM-5) assemble as distinct fusion puncta at the CATs, germling tube, and fusion hyphae tips every 4 min during chemotropic interactions (Fleissner et al. 2009; Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). In the absence of HAM-5, MEK-2 and MAK-2 localization is cytoplasmic (Jonkers et al. 2014). The assembly/disassembly of the fusion puncta is essential for chemotropic interactions (Fleissner et al. 2009). Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of HAM-5 via MAK-2 and other cellular kinases is thought to regulate the oscillatory formation and disassembly of fusion puncta during chemotropic interactions (Dettmann et al. 2014; Jonkers et al. 2014). At the N terminus, HAM-5 consists of a WD40 motif important for binding MAK-2 (Jonkers et al. 2014). WD40 repeats form a β-propeller, which is a disc-like structure with blades assembled around a central channel (Chen et al. 2011). The propeller structure is a stable scaffold capable of forming protein–protein interactions (Xu and Min 2011). The interaction of HAM-5 with MEK-2 is regulated by sequences after the WD40 domain (amino acids 351–523), and which includes the α-solenoid region; restoration of HAM-5 function requires just the β-propeller and α-solenoid region (Figure 1). The β-propeller and α-solenoid region of HAM-5 is very similar to the organization of Sec31p, a component of the COPII complex in S. cerevisiae (Figure S8). Sec31 is involved in the formation of the COPII cage that forms around vesicles that bud from the ER and are transported to the Golgi (Salama et al. 1997). A crystallographic study demonstrated that the central α-helical unit of Sec31 is structurally similar to nucleoporins (Brohawn et al. 2008); HAM-5 puncta are often found associated with the nuclear periphery (Jonkers et al. 2014 and this study). Sec31 and Sec13 are capable of self-assembly into polyhedral cages in the absence of membranes or other proteins (Stagg et al. 2007). These observations suggest that self-assembly of HAM-5 into cage-like structures may provide scaffold functions for the MAK-2 cascade complex and prompted us to explore colocalization of HAM-5 puncta with other cellular markers.

The N-terminal 523 aa of HAM-5, which includes the WD40 domain and the α-solenoid region, are essential for the formation of puncta. Additional proteins, such as HAM-14, play a role in recruiting MAPK components to the HAM-5 scaffold. This hypothesis suggests that the reason the Δham-14 mutants are fusion deficient is their inability to effectively recruit MAK-2 (and perhaps other components of the MAK-2 signal transduction pathway) to the HAM-5 scaffold in germlings during chemotropic interactions. The recruitment of MAK-2 to the HAM-5 scaffold by HAM-14 may also play a role in enforcing and maintaining the oscillation of the MAK-2/HAM-5 complex to the fusion tip or may facilitate HAM-14 phosphorylation. It is predicted that genetically identical interacting germlings must switch between two different physiological states: a “receiving” vs. a “sending” state (Fleissner and Glass 2007; Goryachev et al. 2012), which enables communication, but avoids self-stimulation. Both genetic and biochemical evidence suggests that the coordinated assembly and disassembly of fusion puncta in interacting germlings is important for mediating communication, which may be facilitated by HAM-14. Future work will continue to dissect the molecular mechanism of how a germling switches from one state to another and how the germlings send and receive signals. Importantly, to fully understand the process of germling communication, the elusive receptors/ligands for initiating this process require identification; so far numerous screens of the N. crassa deletion collection have failed to reveal candidates (Fu et al. 2011; Read et al. 2012; Leeder et al. 2013).

ham-14 and ham-5 are conserved among filamentous ascomycete species (Pezizomycotina), while mak-2 is broadly conserved across fungi, animals, and plants. We predict that the function of both HAM-5 and HAM-14 in fusion and colony development will be conserved in a wide range of filamentous ascomycete fungi. Cell fusion and the ability to form a syncytium provides a fungal colony with many advantages ranging from improved fitness and enhanced ability to adapt to the environment, in addition to mixing of genetic material and cellular components (Richard et al. 2012; Roper et al. 2013; Bastiaans et al. 2015). Also, for some plant pathogenic fungi, the ability to fuse affects the ability to form an infection network or is a prerequisite to infect their host (Craven et al. 2008; Prados Rosales and Di Pietro 2008; Guo et al. 2015). In contrast, in endophytic fungi, failure to form a network has been associated with a switch from a mutualistic to pathogenic state (Eaton et al. 2011; Charlton et al. 2012).

HAM-14 is unique in that it is required for germling fusion, but not essential for hyphal fusion, consistent with the fact that the ∆ham-14 mutant is female fertile and lacks a “flat” phenotype that is ubiquitous in fusion mutants that cannot undergo germling or hyphal fusion. Although hyphal fusion events were observed in a ∆ham-14 mutant, we were not able to witness the actual fusion process. It is possible that HAM-14 is only specific for germling fusion and that a second protein performs a similar function in hyphae. An alternative explanation is that during hyphal fusion within a mature colony, two different fusion events can take place: directed, chemotropic growth that uses the same components as germling fusion or fusion events that occur when two hyphae randomly meet and fuse without undergoing prior chemotropism. It could be that in the ∆ham-14 strain, the latter can still take place but the former cannot. Both events have been documented in WT via live cell imaging of hyphal fusion events (Hickey et al. 2002). For the latter event, although chemotropic growth might not be required, the MAK-2/HAM-5 complex function might still be required for cell wall breakdown and membrane merger; MAK-2 remains at the contact point and at the membrane during pore formation (Fleissner et al. 2009).

In recent years, many novel components of the germling fusion apparatus in N. crassa have been discovered. The discoveries showed in this study help us to better understand the molecular processes underlying self-recognition and communication between genetically identical cells as well as the dynamic oscillatory recruitment of proteins required for communication and fusion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Coyle from the University of California San Francisco for performing secondary structure analysis with HAM-5. We are pleased to acknowledge use of deletion strains generated by P01 GM068087 ‘‘Functional Analysis of a Model Filamentous Fungus’’ and which are publically available at the Fungal Genetics Stock Center. This work was funded by National Science Foundation grants (MCB-1121311 and MCB-1412411) and an Alexander von Humboldt research award to N.L.G.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: M. D. Rose

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/cgi/data/genetics.115.185348/DC1.

Literature Cited

- Aguilar P. S., Baylies M. K., Fleissner A., Helming L., Inoue N., et al. , 2013. Genetic basis of cell-cell fusion mechanisms. Trends Genet. 29: 427–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldabbous M. S., Roca M. G., Stout A., Huang I. C., Read N. D., et al. , 2010. The ham-5, rcm-1 and rco-1 genes regulate hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa. Microbiology 156: 2621–2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaans E., Debets A. J., Aanen D. K., 2015. Experimental demonstration of the benefits of somatic fusion and the consequences for allorecognition. Evolution 69: 1091–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berepiki A., Lichius A., Shoji J. Y., Tilsner J., Read N. D., 2010. F-actin dynamics in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 9: 547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman B. J., Draskovic M., Freitag M., Bowman E. J., 2009. Structure and distribution of organelles and cellular location of calcium transporters in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 8: 1845–1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman B. J., Draskovic M., Schnittker R. R., El-Mellouki T., Plamann M. D., et al. , 2015. Characterization of a Novel Prevacuolar Compartment in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 14: 1253–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohawn S. G., Leksa N. C., Spear E. D., Rajashankar K. R., Schwartz T. U., 2008. Structural evidence for common ancestry of the nuclear pore complex and vesicle coats. Science 322: 1369–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R. E., Tour O., Palmer A. E., Steinbach P. A., Baird G. S., et al. , 2002. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 7877–7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Dominguez N., Alvarez-Delfin K., Hansberg W., Aguirre J., 2008. NADPH oxidases NOX-1 and NOX-2 require the regulatory subunit NOR-1 to control cell differentiation and growth in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 7: 1352–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagnon P. L., 2014. Ecological and evolutionary implications of hyphal anastomosis in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 88: 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton N. D., Shoji J. Y., Ghimire S. R., Nakashima J., Craven K. D., 2012. Deletion of the fungal gene soft disrupts mutualistic symbiosis between the grass endophyte Epichloe festucae and the host plant. Eukaryot. Cell 11: 1463–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. K., Chan N. L., Wang A. H., 2011. The many blades of the beta-propeller proteins: conserved but versatile. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36: 553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E. H., Olson E. N., 2005. Unveiling the mechanisms of cell-cell fusion. Science 308: 369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colot H. V., Park G., Turner G. E., Ringelberg C., Crew C. M., et al. , 2006. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 10352–10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven K. D., Velez H., Cho Y., Lawrence C. B., Mitchell T. K., 2008. Anastomosis is required for virulence of the fungal necrotroph Alternaria brassicicola. Eukaryot. Cell 7: 675–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Alvarez D. L., Callejas-Negrete O. A., Gomez N., Freitag M., Roberson R. W., et al. , 2010. Visualization of F-actin localization and dynamics with live cell markers in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47: 573–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmann A., Illgen J., Marz S., Schurg T., Fleissner A., et al. , 2012. The NDR kinase scaffold HYM1/MO25 is essential for MAK2 map kinase signaling in Neurospora crassa. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmann A., Heilig Y., Ludwig S., Schmitt K., Illgen J., et al. , 2013. HAM-2 and HAM-3 are central for the assembly of the Neurospora STRIPAK complex at the nuclear envelope and regulate nuclear accumulation of the MAP kinase MAK-1 in a MAK-2-dependent manner. Mol. Microbiol. 90: 796–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmann A., Heilig Y., Valerius O., Ludwig S., Seiler S., 2014. Fungal communication requires the MAK-2 pathway elements STE-20 and RAS-2, the NRC-1 adapter STE-50 and the MAP kinase scaffold HAM-5. PLoS Genet. 10: e1004762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap J. C., Borkovich K. A., Henn M. R., Turner G. E., Sachs M. S., et al. , 2007. Enabling a community to dissect an organism: Overview of the Neurospora functional genomics project. Adv. Genet. 57: 49–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton C. J., Cox M. P., Scott B., 2011. What triggers grass endophytes to switch from mutualism to pathogenism? Plant Sci. 180: 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleissner A., Glass N. L., 2007. SO, a protein involved in hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa, localizes to septal plugs. Eukaryot. Cell 6: 84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleissner A., Sarkar S., Jacobson D. J., Roca M. G., Read N. D., et al. , 2005. The so locus is required for vegetative cell fusion and postfertilization events in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 4: 920–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleissner A., Leeder A. C., Roca M. G., Read N. D., Glass N. L., 2009. Oscillatory recruitment of signaling proteins to cell tips promotes coordinated behavior during cell fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 19387–19392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M., Hickey P. C., Raju N. B., Selker E. U., Read N. D., 2004. GFP as a tool to analyze the organization, dynamics and function of nuclei and microtubules in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41: 897–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag, M., and E. U. Selker, 2005 Expression and visualization of red fluorescent protein (RFP) in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 52: 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, M., L. Boddy, T. Nakagaki, and D. P. Bebber, 2009 Adaptive biological networks, pp. 51–70 in Adaptive Networks: Theory, Models and Applications, edited by T. Gross, and H. Sayama. Springer-Verlag, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Fu C., Iyer P., Herkal A., Abdullah J., Stout A., et al. , 2011. Identification and characterization of genes required for cell-to-cell fusion in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 10: 1100–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C., Ao J., Dettmann A., Seiler S., Free S. J., 2014. Characterization of the Neurospora crassa cell fusion proteins, HAM-6, HAM-7, HAM-8, HAM-9, HAM-10, AMPH-1 and WHI-2. PLoS One 9: e107773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaboriaud C., Bissery V., Benchetrit T., Mornon J. P., 1987. Hydrophobic cluster analysis: an efficient new way to compare and analyse amino acid sequences. FEBS Lett. 224: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goryachev A. B., Lichius A., Wright G. D., Read N. D., 2012. Excitable behavior can explain the “ping-pong” mode of communication between cells using the same chemoattractant. BioEssays 34: 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Wenner N., Kuldau G. A., 2015. FvSO regulates vegetative hyphal fusion, asexual growth, fumonisin B1 production, and virulence in Fusarium verticillioides. Fungal Biol. 119: 1158–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog S., Schumann M. R., Fleissner A., 2015. Cell fusion in Neurospora crassa. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 28: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey P. C., Jacobson D., Read N. D., Louise Glass N. L., 2002. Live-cell imaging of vegetative hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 37: 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers W., Leeder A. C., Ansong C., Wang Y., Yang F., et al. , 2014. HAM-5 functions as a MAP kinase scaffold during cell fusion in Neurospora crassa. PLoS Genet. 10: e1004783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley L. A., Mezulis S., Yates C. M., Wass M. N., Sternberg M. J., 2015. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10: 845–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeder A. C., Jonkers W., Li J., Glass N. L., 2013. Germination and early colony establishment in Neurospora crassa requires a MAP kinase regulatory network. Genetics 195: 883–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin B. S., Freitag M., Selker E. U., 1997. Improved plasmids for gene targeting at the his-3 locus of Neurospora crassa by electroporation. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 44: 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey K., 2003. The Fungal Genetics Stock Center: from molds to molecules. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 52: 245–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok J., Kim P. M., Lam H. Y., Piccirillo S., Zhou X., et al. , 2010. Deciphering protein kinase specificity through large-scale analysis of yeast phosphorylation site motifs. Sci. Signal. 3: ra12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A., Roca M. G., Read N. D., Glass N. L., 2004. Role of a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway during conidial germination and hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 3: 348–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit A., Maheshwari R., 1994. A simple method of obtaining pure microconidia in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 41: 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell S. C., Marotti L. A., Jr, Kiang L., Torres M. P., Borchers C. H., et al. , 2005. Phosphorylation of the RGS protein Sst2 by the MAP kinase Fus3 and use of Sst2 as a model to analyze determinants of substrate sequence specificity. Biochemistry 44: 8159–8166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prados Rosales R. C., Di Pietro A., 2008. Vegetative hyphal fusion Is not essential for plant infection by Fusarium oxysporum. Eukaryot. Cell 7: 162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read N. D., Goryachev A. B., Lichius A., 2012. The mechanistic basis of self-fusion between conidial anastomosis tubes during fungal colony initiation. Fungal Biol. Rev. 26: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Richard F., Glass N. L., Pringle A., 2012. Cooperation among germinating spores facilitates the growth of the fungus, Neurospora crassa. Biol. Lett. 8: 419–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca M., Arlt J., Jeffree C., Read N., 2005. Cell biology of conidial anastomosis tubes in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 4: 911–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca M. G., Kuo H. C., Lichius A., Freitag M., Read N. D., 2010. Nuclear dynamics, mitosis, and the cytoskeleton during the early stages of colony initiation in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 9: 1171–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper M., Simonin A., Hickey P. C., Leeder A., Glass N. L., 2013. Nuclear dynamics in a fungal chimera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 12875–12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama N. R., Chuang J. S., Schekman R. W., 1997. Sec31 encodes an essential component of the COPII coat required for transport vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell 8: 205–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]