Abstract

Activated myofibroblasts are key effector cells in tissue fibrosis. Emerging evidence suggests that myofibroblasts infiltrating fibrotic tissues originate predominantly from local mesenchyme-derived populations. Alterations in the extracellular matrix network play an important role in modulating fibroblast phenotype and function. In a pro-inflammatory environment, generation of matrix fragments may induce a matrix-degrading fibroblast phenotype. Deposition of ED-A fibronectin plays an important role in myofibroblast transdifferentiation. In fibrotic tissues, the matrix is enriched with matricellular macromolecules that regulate growth factor-mediated responses and modulate protease activation. This manuscript discusses emerging concepts on the role of the extracellular matrix in regulation of fibroblast behavior.

Keywords: Fibroblast, Pericyte, Myofibroblast, Extracellular matrix, Matricellular protein, Thrombospondin

Introduction

Fibrosis is defined as the accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins in tissue and is a common pathophysiologic companion of many pathologic conditions [1]. Expansion of the extracellular matrix network is an important part of the reparative response following tissue injury. Cell necrosis triggers an inflammatory reaction, ultimately activating fibrogenic pathways and stimulating deposition of matrix proteins. Whether the reparative fibrotic response is a reversible component of wound healing, or results in permanent disruption of organ function, is dependent on the regenerative capacity of the tissue, and the type and extent of the initial injury. For example, skeletal muscle injury heals through activation of a robust regenerative response triggered by myogenic precursor cells [2]. In contrast, the myocardium and the central nervous system exhibit negligible regenerative capacity; as a result, cellular loss in these organs is repaired through the formation of a collagen-based scar [3]. In all cases, irreversible fibrosis disrupts the normal architecture of the tissue and causes organ dysfunction. A wide range of diseases are associated with fibrosis, including hepatic cirrhosis, chronic renal disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and heart failure [1, 4•, 5, 6]. Moreover, metabolic conditions (such as diabetes, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome), and disorders associated with activation or dysregulation of the immune system (such as scleroderma) cause fibrotic remodeling in many tissues [7–9]. Considering the involvement of fibrosis in renal failure, end-stage liver disease, and in the pathogenesis of heart failure and cardiac arrhythmias, fibrotic remodeling is implicated, directly or indirectly, in a substantial number of deaths worldwide.

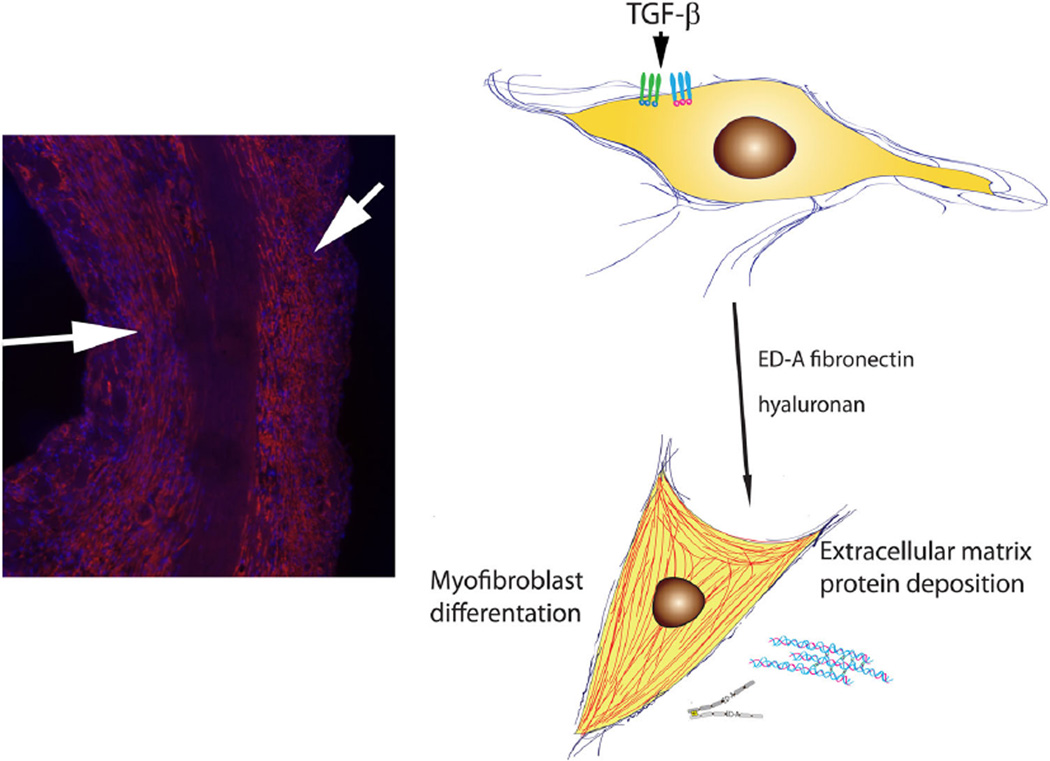

Fibroblasts are the main effector cells in tissue fibrosis, capable of synthesizing and remodeling the extracellular matrix. Most tissues contain large numbers of fibroblasts that can be activated by a wide range of stimuli, such as pathogens, mediators released by necrotic cells, toxins, and leukocyte-derived products. Conversion of quiescent fibroblasts into activated matrix-producing myofibroblasts (Fig. 1) [10] is a key event in tissue fibrosis [11, 12]. Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests that in injured and remodeling tissues, other resident or newly recruited cell types may transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts, expanding the pool of cells with fibrogenic potential. Despite the critical role of activated fibroblasts in the fibrotic process, the cell biology and molecular mechanisms of fibroblast activation remain mysterious. Traditionally defined by their morphology and capacity to secrete matrix proteins, fibroblasts exhibit significant heterogeneity and plasticity. The features that characterize various fibroblast subpopulations have not been systematically defined; the molecular signals implicated in fibroblast activation are poorly understood. The current manuscript reviews recent advances on the cellular origin of fibroblasts in injured tissues. Because fibroblast phenotype is critically modulated by alterations in the extracellular matrix environment, we focus specifically on the effects of matrix macromolecules in fibroblast activity and function.

Fig. 1.

Activated myofibroblasts are the main effector cells in tissue fibrosis. Left Immunofluorescent staining for α-smooth muscle actin identifies myofibroblasts in the infarcted heart. These cells are localized in the infarct border zone (arrows) and produce large amounts of extracellular matrix proteins. Right Myofibroblast conversion is mediated through activation of TGF-β signaling cascades and involves components of the extracellular matrix (ED-A fibronectin, hyaluronan, non-fibrillar collagens, etc.)

Origin of Fibroblasts in Fibrotic Tissues: The Concept of Cellular Plasticity

A wide range of injurious stimuli can cause expansion and activation of fibroblast populations in affected tissues. The origin of these activated fibroblasts remains a hotly debated question. More than a decade ago, a large body of evidence suggested that a wide range of cell types, including epithelial cells, vascular endothelial cells, and pericytes, exhibit a remarkable plasticity and can differentiate into fibroblasts in response to microenvironmental cues [13, 14]. In the pressure-overloaded myocardium, endothelial-to- mesenchymal transdifferentiation was implicated in generation of abundant myofibroblasts [15]. Moreover, hematopoietic progenitors were proposed as an additional source of fibroblasts in injured tissues [16–19]. Unfortunately, the lack of reliable and specific markers to identify fibroblasts has hampered efforts to understand the origin of fibroblasts in health and disease. Many studies attempting to trace fibroblast lineages have used non-specific markers, such as fibroblast-specific protein (FSP)-1/S100A4 [15, 20], a calcium-binding protein that is also abundantly expressed by leukocytes and vascular cells [21, 22]. Moreover, the origin of activated fibroblasts may depend on the tissue studied and on the type of injury. For example, injurious responses that cause cellular necrosis are often associated with robust upregulation of chemokines [23] and recruitment of abundant circulating cells. In this context, the contribution of circulating fibrocytes may be accentuated, due to increased chemoattraction of fibroblast progenitors through chemokine-mediated pathways [24, 25].

In recent years, experimental studies using fate-mapping strategies have produced an explosion in our knowledge on the origin of fibroblasts in fibrotic tissues. A growing body of evidence suggests that in most tissues, local mesenchyme-derived subpopulations of fibroblasts may act as the main cellular effectors of fibrotic responses. Although small populations of blood-derived fibroblasts have been identified in the fibrotic kidney and liver [26, 27], their relative contribution remains unknown. Several seminal investigations have identified local interstitial cell subsets as important sources of activated fibroblasts in various organs.

In normal and lesional mouse skin, lineage tracing approaches demonstrated that the Engrailed-1 lineage is the main source of matrix-secreting fibroblasts in normal skin, in healing cutaneous wounds, in radiation injury, and in the stroma of melanomas [28•]. Ablation of these highly fibrogenic cells that expressed CD26 significantly reduced scarring following cutaneous injury and delayed growth of melanomas.

In several different organs, perivascular cells serve as important sources of activated myofibroblasts [26, 29, 30]. Pericytes are defined as perivascular cells of mesenchymal origin, which are sheathed with a basement membrane, and directly communicate with endothelial cells [31]. Studies in experimental models of kidney fibrosis have suggested that pericytes may be a major source of myofibroblasts [26, 30]. Recent investigations have indicated a broader role for perivascular cells in the pathogenesis of tissue fibrosis. Expression of Gli1, a transcription factor that mediates hedgehog signaling, marks a population of tissue-resident perivascular cells that transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts in the heart, kidney, lung, and liver [32•].

Local fibroblast progenitor populations may also be crucial contributors in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. The adult mammalian myocardium contains a large number of poorly defined fibroblast-like cells that may outnumber cardiomyocytes [33, 34] and, upon activation, may generate myofibroblasts. Lineage tracing studies suggested that, in the pressure-overloaded heart, the majority of activated myofibroblasts originate from proliferation and activation of resident fibroblast lineages, rather than from hematopoietic or endothelial cells [35•, 36]. In the infarcted myocardium, an epicardial-derived subset of cardiac fibroblasts appears to contribute to the reparative/fibrotic response [37].

Role of the Extracellular Matrix in Fibroblast Activation

An important question in understanding both the reparative process and the fibrotic response is whether fibroblasts become intrinsically activated, or simply respond to alterations in their matrix environment. In tissue repair, fibroblasts appear to be highly dynamic cells that can acquire distinct phenotypes depending on changes in their environment [38]. In healing myocardial infarcts, fibroblasts during the early inflammatory phase of cardiac repair exhibit high expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [39] and may act as inflammatory cells, activating the inflammasome [40], and producing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. As the inflammatory response is suppressed, fibroblasts proliferate, transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts, and secrete large amounts of extracellular matrix proteins [41–43]. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-mediated Smad-dependent signaling plays an important role in activation of a matrix-synthetic phenotype in infarct myofibroblasts [44]. As the scar matures, myofibroblasts become quiescent or undergo apoptosis. Alterations in the environmental conditions regulate modulation of fibroblast phenotype. Secreted mediators such as angiotensin II, TGF-β, the mast cell proteases tryptase and chymase, endothelin-1, and platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) participate in regulation of fibroblast activation and gene expression [5, 45–48]. The composition of the extracellular matrix also critically regulates fibroblast phenotype in fibrotic tissues [49]. The importance of the extracellular matrix in directing fibroblast phenotype is suggested by experimental studies using cells and decellularized matrix isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. These experiments suggested that the fibrotic matrix accentuates fibroblast-derived matrix synthesis, driving a highly fibrogenic phenotype [50•].

Matrix Degradation Products May Activate a Pro-inflammatory Fibroblast Phenotype

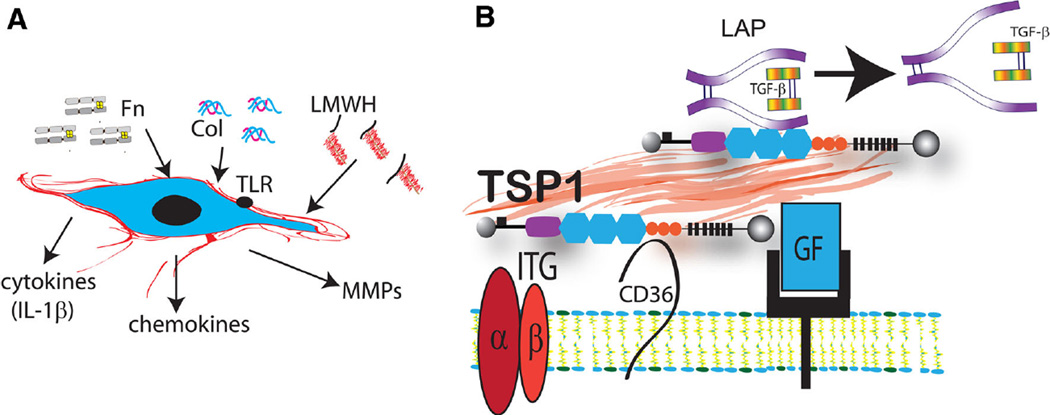

In an inflammatory environment, fibroblasts acquire a pro-inflammatory and matrix-degrading phenotype [51]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1, delay myofibroblast conversion and induce chemokine and MMP synthesis by tissue fibroblasts [39, 52]. Inflammatory activation of fibroblasts may also be driven by changes in the extracellular matrix. Inflammation is associated with protease activation and generation of matrix fragments with pro-inflammatory properties; these fragments serve as “danger signals” that trigger inflammation (Fig. 2a). Fibronectin fragments are rapidly released in the extracellular space following injury and activate pro-inflammatory signaling. In contrast to the intact fibronectin molecule, the 120 kDa cell-binding fibronectin fragment (Fn120) potently stimulates monocyte chemotaxis [53]. Both 120 and 45 kDa fibronectin fragments have been shown to activate a matrix-degrading program in human fibroblasts, stimulating MMP expression and activity [54–56]. In vitro studies suggest that hyaluronan fragments may also exert potent pro-inflammatory actions. In synovial fibroblasts, hyaluronan degradation products exerted pro-inflammatory actions activating CD44 and toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 signaling [57]. In human dermal fibroblasts, hyaluronan fragments increased MMP expression [58]. Support for the pro-inflammatory actions of matrix degradation products on cardiac fibroblasts is predominantly derived from in vitro studies. In vivo evidence on the role of these actions in regulating fibroblast phenotype is lacking.

Fig. 2.

Alterations in the extracellular matrix network modulate fibroblast phenotype. a In a pro-inflammatory environment, collagen (Col), fibronectin (Fn), and low-molecular weight hyaluronan (LMWH) fragments stimulate a matrix-degrading fibroblast phenotype and may induce expression of pro-inflammatory mediators. b In fibrotic tissues, the extracellular matrix is enriched with matricellular proteins. These macromolecules do not play a structural role, but bind to growth factors and cell surface receptors and transduce signaling responses. For example, the prototypical matricellular protein thrombospondin (TSP)-1 is deposited into the matrix and modulates fibroblast function by facilitating the release of bioactive TGF-β (through a direct interaction with the latency-associated peptide/LAP), and by modulating growth factor (GF)- and integrin (ITG)-mediated responses. Some of the effects of TSP-1 may be mediated through activation of CD36 signaling

The Provisional Matrix Provides a Conduit for Fibroblast Migration in Repair and in Fibrosis

In tissue repair, matrix degradation during the inflammatory phase is accompanied by extravasation of plasma proteins through hyperpermeable vessels, resulting in the formation of a provisional matrix network that comprises predominantly fibrin (derived from extravasated fibrinogen) and plasma fibronectin [59]. The fibrin-rich provisional matrix is later lysed by proteolytic enzymes, and replaced by a cell-derived “second order” provisional matrix that contains cellular fibronectin and hyaluronan [60]. Fibronectin and fibrin are also deposited in the extracellular matrix in chronic fibrotic conditions [61]. The provisional matrix plays a critical role in regulating the orchestrated movement of leukocytes, fibroblasts, and vascular cells in healing and fibrotic tissues, serving as a conduit for cell migration [62]. In addition to its effects on fibroblast migration, fibronectin also activates fibroblast proliferation [63] and modulates fibroblast gene expression, acting through pathways involving α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins, and syndecans [64–67]. Cell adhesion to the central cell-binding domain of fibronectin, and activation of growth factor responses facilitated by fibronectin are essential for fibroblast survival [68].

The Matrix Regulates Myofibroblast Conversion

Modulation of the extracellular matrix critically regulates myofibroblast transdifferentiation, the key step in tissue fibrosis. The ED-A variant of fibronectin, non-fibrillar collagens, and hyaluronan have been implicated in myofibroblast conversion. ED-A fibronectin expression precedes myofibroblast transdifferentiation in healing and fibrotic tissues and is essential for TGF-β1-mediated myofibroblast conversion [69]. Non-fibrillar collagens (such as collagen VI) have been reported to stimulate myofibroblast transdifferentiation, both in vitro and in vivo [70, 71]. Moreover, deposition of pericellular hyaluronan may also facilitate and maintain myofibroblast transdifferentiation in response to TGF-β [72–74]. Activation of CD44 signaling by hyaluronan may accentuate the TGF-β/Smad signaling cascade [75]. In vitro experiments demonstrated that hyperglycemia-mediated collagen glycation may promote myofibroblast transdifferentiation, suggesting a matrix-dependent pathway that may be involved in diabetes-associated tissue fibrosis [76].

Matricellular Proteins Regulate Fibroblast Phenotype and Function

The term “matricellular protein” was coined to describe a family of structurally unrelated extracellular macromolecules that do not serve a structural role, but bind to matrix proteins, growth factors, and cell surface receptors, transducing signaling cascades [77, 78]. The family includes the thrombospondins (TSPs), SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine), osteopontin (OPN), tenascin-C, periostin, and the members of the CCN (Cyr61/CTGF/NOV) family. Most matricellular proteins are not expressed in normal tissues, but enrich the extracellular matrix following injury and participate in reparative and fibrotic responses.

The prototypical matricellular protein TSP-1 is consistently upregulated in fibrotic tissues [79] and regulates fibroblast function through several distinct mechanisms (Fig. 2b). First, TSP-1 may promote myofibroblast transdifferentiation through activation of TGF-β [80, 81]. TSP-1 binds to the latency-associated peptide (LAP) and promotes the release of the active TGF-β dimer from the latent complex [82]. Second, TSP-1 may exert direct actions on cardiac fibroblasts (possibly mediated through CD36 activation), stimulating an activated matrix-synthetic phenotype [83]. Third, TSP-1 may exert direct matrix-stabilizing actions by inhibiting protease activation [84, 85]. Tenascin-C is also markedly upregulated in injured, healing, and remodeling tissues and may contribute to the pathogenesis of fibrosis through actions on fibroblasts and macrophages [86, 87]. Tenascin-C has broad actions on fibroblast phenotype, stimulating migration and accelerating myofibroblast conversion [88]. Tenascin-C binds to a wide range of growth factors, including TGF-βs, PDGFs, and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) [89] and may regulate their actions on cardiac fibroblasts. SPARC expression is also upregulated in fibrotic tissues and has been reported to modulate growth factor-mediated responses [90]. OPN may act both as a cytokine (when secreted in a soluble form), and as a matricellular protein (when bound to the extracellular matrix). A large body of in vitro and in vivo evidence suggests that OPN plays an important role in activation of fibroblasts in several different tissues [91–93]. OPN may act by stimulating fibroblast migration [93], by increasing fibroblast survival [94], and by promoting proliferation [95] through effects involving CD44 and αvβ3 integrin signaling. Periostin is consistently induced in activated myofibroblasts and critically regulates their matrix-synthetic function [96]. Periostin potently stimulates fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast persistence [97]; whether its stimulatory actions involve intracellular or matricellular effects remains unknown.

Several members of the CCN matricellular family have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of fibrotic diseases. CCN2 is a fibrogenic mediator that potentiates fibroblast adhesion to fibronectin [98], induces matrix protein synthesis [99], and stimulates fibroblast proliferation [100]. In vivo, CCN2 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of fibrosis in several distinct models of fibrosis [101, 102]. In contrast, CCN1 and CCN5 exert anti-fibrotic actions. In the liver, CCN1 is upregulated following injury and suppresses fibrosis [103•], attenuating TGF-β signaling and accentuating apoptosis [104]. CCN5 also reduces fibrosis, attenuating TGF-β/Smad responses [105].

Conclusions

The extracellular matrix actively participates in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. Over the last 10 years, an impressive body of evidence has documented critical effects of matrix macromolecules on fibroblast phenotype and function. Important questions remain to be explored. Are matricellular actions involved in the plasticity of interstitial cells in fibrotic tissues? Do fibroblast subsets have distinct responses to alterations in their matrix environment? Can we modulate the extracellular matrix to restrain fibrosis? Understanding the molecular basis for matrix-dependent actions on fibroblast activation holds therapeutic promise. Identification of specific functional domains responsible for the effects of matrix macromolecules may lead to design of novel therapeutic strategies using peptides that selectively reproduce or inhibit specific matrix-dependent actions.

Acknowledgments

Dr Frangogiannis’ laboratory is supported by NIH Grants R01 HL76246 and R01 HL85440.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest Nikolaos G Frangogiannis declares no conflict of interest.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol. 2008;214:199–210. doi: 10.1002/path.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumont NA, Bentzinger CF, Sincennes MC, et al. Satellite cells and skeletal muscle regeneration. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:1027–1059. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frangogiannis NG. Pathophysiology of myocardial infarction. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:1841–1875. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duffield JS. Cellular and molecular mechanisms in kidney fibrosis. J Clin Investig. 2014;124:2299–2306. doi: 10.1172/JCI72267. A highly informative and well-illustrated review on the cell biology of renal fibrosis

- 5.Kong P, Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. The pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:549–574. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1349-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:1028–1040. doi: 10.1038/nm.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavalera M, Wang J, Frangogiannis NG. Obesity, metabolic dysfunction, and cardiac fibrosis: pathophysiological pathways, molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Transl Res. 2014;164:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leask A. Matrix remodeling in systemic sclerosis. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37:559–563. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biernacka A, Cavalera M, Wang J, et al. Smad3 signaling promotes fibrosis while preserving cardiac and aortic geometry in obese diabetic mice. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:788–798. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabbiani G, Majno G. Dupuytren’s contracture: fibroblast contraction?: an ultrastructural study. Am J Pathol. 1972;66:131–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast in wound healing and fibrocontractive diseases. J Pathol. 2003;200:500–503. doi: 10.1002/path.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinz B. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Investig Dermatol. 2007;127:526–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Investig. 2003;112:1776–1784. doi: 10.1172/JCI20530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:952–961. doi: 10.1038/nm1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, et al. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med. 1994;1:71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilling D, Buckley CD, Salmon M, et al. Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by serum amyloid P. J Immunol. 2003;171:5537–5546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haudek SB, Xia Y, Huebener P, et al. Bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors mediate ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18284–18289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608799103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fausther M, Lavoie EG, Dranoff JA. Contribution of myofibroblasts of different origins to liver fibrosis. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2013;1:225–230. doi: 10.1007/s40139-013-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, et al. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Investig. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI15518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osterreicher CH, Penz-Osterreicher M, Grivennikov SI, et al. Fibroblast-specific protein 1 identifies an inflammatory subpopulation of macrophages in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:308–313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017547108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong P, Christia P, Saxena A, et al. Lack of specificity of fibroblast-specific protein 1 in cardiac remodeling and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H1363–H1372. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00395.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewald O, Zymek P, Winkelmann K, et al. CCL2/mono-cyte chemoattractant protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circ Res. 2005;96:881–889. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163017.13772.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frangogiannis NG. Chemokines in ischemia and reperfusion. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:738–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeley EC, Mehrad B, Strieter RM. The role of circulating mesenchymal progenitor cells (fibrocytes) in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disorders. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:613–618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin SL, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA, et al. Pericytes and perivascular fibroblasts are the primary source of collagen-producing cells in obstructive fibrosis of the kidney. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1617–1627. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scholten D, Reichart D, Paik YH, et al. Migration of fibrocytes in fibrogenic liver injury. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rinkevich Y, Walmsley GG, Hu MS, et al. Skin fibrosis: identification and isolation of a dermal lineage with intrinsic fibrogenic potential. Science. 2015;348:aaa2151. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2151. This study identifies a dermal lineage with high fibrogenic potential. Ablation of these CD26+ cells attenuates cutaneous fibrosis

- 29.Goritz C, Dias DO, Tomilin N, et al. A pericyte origin of spinal cord scar tissue. Science. 2011;333:238–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1203165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphreys BD, Lin SL, Kobayashi A, et al. Fate tracing reveals the pericyte and not epithelial origin of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:85–97. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res. 2005;97:512–523. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kramann R, Schneider RK, DiRocco DP, et al. Perivascular Gli1+ progenitors are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.004. A seminal study, demonstrating that Gli1-positive perivascular cells contribute to myofibroblast populations in several different organs

- 33.Nag AC. Study of non-muscle cells of the adult mammalian heart: a fine structural analysis and distribution. Cytobios. 1980;28:41–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. Cardiac fibroblast: the renaissance cell. Circ Res. 2009;105:1164–1176. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moore-Morris T, Guimaraes-Camboa N, Banerjee I, et al. Resident fibroblast lineages mediate pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. J Clin Investig. 2014;124:2921–2934. doi: 10.1172/JCI74783. A systematic study using lineage tracing approaches to study the origin of activated fibroblasts in the fibrotic pressure-overloaded myocardium demonstrates for the first time the crucial role of local resident fibroblast lineages

- 36.Ali SR, Ranjbarvaziri S, Talkhabi M, et al. Developmental heterogeneity of cardiac fibroblasts does not predict pathological proliferation and activation. Circ Res. 2014;115:625–635. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruiz-Villalba A, Simon AM, Pogontke C, et al. Interacting resident epicardium-derived fibroblasts and recruited bone marrow cells form myocardial infarction scar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2057–2066. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinde AV, Frangogiannis NG. Fibroblasts in myocardial infarction: a role in inflammation and repair. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;70C:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saxena A, Chen W, Su Y, et al. IL-1 induces proinflammatory leukocyte infiltration and regulates fibroblast phenotype in the infarcted myocardium. J Immunol. 2013;191:4838–4848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mezzaroma E, Toldo S, Farkas D, et al. The inflammasome promotes adverse cardiac remodeling following acute myocardial infarction in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19725–19730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108586108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willems IE, Havenith MG, De Mey JG, et al. The alpha-smooth muscle actin-positive cells in healing human myocardial scars. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:868–875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleutjens JP, Kandala JC, Guarda E, et al. Regulation of collagen degradation in the rat myocardium after infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(05)82390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frangogiannis NG, Michael LH, Entman ML. Myofibroblasts in reperfused myocardial infarcts express the embryonic form of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMemb) Cardiovasc Res. 2000;48:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bujak M, Ren G, Kweon HJ, et al. Essential role of Smad3 in infarct healing and in the pathogenesis of cardiac remodeling. Circulation. 2007;116:2127–2138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biernacka A, Dobaczewski M, Frangogiannis NG. TGF-beta signaling in fibrosis. Growth Factors. 2011;29:196–202. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.595714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zymek P, Bujak M, Chatila K, et al. The role of platelet-derived growth factor signaling in healing myocardial infarcts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2315–2323. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porter KE, Turner NA. Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He W, Dai C. Key fibrogenic signaling. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2015;3:183–192. doi: 10.1007/s40139-015-0077-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobaczewski M, de Haan JJ, Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix modulates fibroblast phenotype and function in the infarcted myocardium. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:837–847. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9406-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Parker MW, Rossi D, Peterson M, et al. Fibrotic extracellular matrix activates a profibrotic positive feedback loop. J Clin Investig. 2014;124:1622–1635. doi: 10.1172/JCI71386. An interesting study suggesting that the fibrotic extracellular matrix drives fibroblast activation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- 51.Smith RS, Smith TJ, Blieden TM, et al. Fibroblasts as sentinel cells: synthesis of chemokines and regulation of inflammation. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:317–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bujak M, Dobaczewski M, Chatila K, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor type I signaling critically regulates infarct healing and cardiac remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:57–67. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark RA, Wikner NE, Doherty DE, et al. Cryptic chemotactic activity of fibronectin for human monocytes resides in the 120-kDa fibroblastic cell-binding fragment. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12115–12123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huttenlocher A, Werb Z, Tremble P, et al. Decorin regulates collagenase gene expression in fibroblasts adhering to vitronectin. Matrix Biol. 1996;15:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(96)90115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kapila YL, Kapila S, Johnson PW. Fibronectin and fibronectin fragments modulate the expression of proteinases and proteinase inhibitors in human periodontal ligament cells. Matrix Biol. 1996;15:251–261. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(96)90116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kong W, Longaker MT, Lorenz HP. Cyclophilin C-associated protein is a mediator for fibronectin fragment-induced matrix metalloproteinase-13 expression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55334–55340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campo GM, Avenoso A, D’Ascola A, et al. The inhibition of hyaluronan degradation reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines in mouse synovial fibroblasts subjected to collagen-induced arthritis. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:1852–1867. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.David-Raoudi M, Tranchepain F, Deschrevel B, et al. Differential effects of hyaluronan and its fragments on fibroblasts: relation to wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:274–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dobaczewski M, Bujak M, Zymek P, et al. Extracellular matrix remodeling in canine and mouse myocardial infarcts. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:475–488. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Welch MP, Odland GF, Clark RA. Temporal relationships of F-actin bundle formation, collagen and fibronectin matrix assembly, and fibronectin receptor expression to wound contraction. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:133–145. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuhn C, 3rd, Boldt J, King TE, Jr, et al. An immunohistochemical study of architectural remodeling and connective tissue synthesis in pulmonary fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1693–1703. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.6.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clark RA. Wound repair: overview and general considerations. In: Raf C, editor. The molecular and cellular biology of wound repair. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rybarczyk BJ, Lawrence SO, Simpson-Haidaris PJ. Matrix-fibrinogen enhances wound closure by increasing both cell proliferation and migration. Blood. 2003;102:4035–4043. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greiling D, Clark RA. Fibronectin provides a conduit for fibroblast transmigration from collagenous stroma into fibrin clot provisional matrix. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 7):861–870. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.7.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin F, Ren XD, Doris G, et al. Three-dimensional migration of human adult dermal fibroblasts from collagen lattices into fibrin/fibronectin gels requires syndecan-4 proteoglycan. J Investig Dermatol. 2005;124:906–913. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corbett SA, Schwarzbauer JE. Fibronectin-fibrin cross-linking: a regulator of cell behavior. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1998;8:357–362. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(98)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li X, Qian H, Ono F, et al. Human dermal fibroblast migration induced by fibronectin in autocrine and paracrine manners. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:682–684. doi: 10.1111/exd.12447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin F, Ren XD, Pan Z, et al. Fibronectin growth factor-binding domains are required for fibroblast survival. J Investig Dermatol. 2011;131:84–98. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Serini G, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Ropraz P, et al. The fibronectin domain ED-A is crucial for myofibroblastic phenotype induction by transforming growth factor-beta1. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:873–881. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naugle JE, Olson ER, Zhang X, et al. Type VI collagen induces cardiac myofibroblast differentiation: implications for postinfarction remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H323–H330. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00321.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luther DJ, Thodeti CK, Shamhart PE, et al. Absence of type VI collagen paradoxically improves cardiac function, structure, and remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012;110:851–856. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.252734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Webber J, Meran S, Steadman R, et al. Hyaluronan orchestrates transforming growth factor-beta1-dependent maintenance of myofibroblast phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9083–9092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806989200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meran S, Thomas D, Stephens P, et al. Involvement of hyaluronan in regulation of fibroblast phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25687–25697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Midgley AC, Rogers M, Hallett MB, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1)-stimulated fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation is mediated by hyaluronan (HA)-facilitated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and CD44 co-localization in lipid rafts. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:14824–14838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.451336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huebener P, Abou-Khamis T, Zymek P, et al. CD44 is critically involved in infarct healing by regulating the inflammatory and fibrotic response. J Immunol. 2008;180:2625–2633. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yuen A, Laschinger C, Talior I, et al. Methylglyoxal-modified collagen promotes myofibroblast differentiation. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:537–548. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bornstein P. Matricellular proteins: an overview. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:163–165. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0069-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Frangogiannis NG. Matricellular proteins in cardiac adaptation and disease. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:635–688. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xia Y, Dobaczewski M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, et al. Endogenous thrombospondin 1 protects the pressure-overloaded myocardium by modulating fibroblast phenotype and matrix metabolism. Hypertension. 2011;58:902–911. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Adams JC, Lawler J. The thrombospondins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zeisberg M, Tampe B, LeBleu V, et al. Thrombospondin-1 deficiency causes a shift from fibroproliferative to inflammatory kidney disease and delays onset of renal failure. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:2687–2698. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ribeiro SM, Poczatek M, Schultz-Cherry S, et al. The activation sequence of thrombospondin-1 interacts with the latency-associated peptide to regulate activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13586–13593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gonzalez-Quesada C, Cavalera M, Biernacka A, et al. Thrombospondin-1 induction in the diabetic myocardium stabilizes the cardiac matrix in addition to promoting vascular rarefaction through angiopoietin-2 upregulation. Circ Res. 2013;113:1331–1344. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Lane TF, Ortega MA, et al. Thrombospondin-1 suppresses spontaneous tumor growth and inhibits activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and mobilization of vascular endothelial growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12485–12490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171460498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hogg PJ. Thrombospondin 1 as an enzyme inhibitor. Thromb Haemost. 1994;72:787–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carey WA, Taylor GD, Dean WB, et al. Tenascin-C deficiency attenuates TGF-ss-mediated fibrosis following murine lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L785–L793. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00385.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shimojo N, Hashizume R, Kanayama K, et al. Tenascin-C may accelerate cardiac fibrosis by activating macrophages via the integrin alphaVbeta3/nuclear factor-kappaB/interleukin-6 axis. Hypertension. 2015;66:757–766. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tamaoki M, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Yokoyama K, et al. Tenascin-C regulates recruitment of myofibroblasts during tissue repair after myocardial injury. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:71–80. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62954-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.De Laporte L, Rice JJ, Tortelli F, et al. Tenascin C promiscuously binds growth factors via its fifth fibronectin type III-like domain. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schellings MW, Vanhoutte D, Swinnen M, et al. Absence of SPARC results in increased cardiac rupture and dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction. J Exp Med. 2009;206:113–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ashizawa N, Graf K, Do YS, et al. Osteopontin is produced by rat cardiac fibroblasts and mediates A(II)-induced DNA synthesis and collagen gel contraction. J Clin Investig. 1996;98:2218–2227. doi: 10.1172/JCI119031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lorenzen JM, Schauerte C, Hubner A, et al. Osteopontin is indispensible for AP1-mediated angiotensin II-related miR-21 transcription during cardiac fibrosis. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2184–2196. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu M, Schneider DJ, Mayes MD, et al. Osteopontin in systemic sclerosis and its role in dermal fibrosis. J Investig Dermatol. 2012;132:1605–1614. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zohar R, Zhu B, Liu P, et al. Increased cell death in osteopontin-deficient cardiac fibroblasts occurs by a caspase-3-independent pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1730–H1739. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00098.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Anwar A, Li M, Frid MG, et al. Osteopontin is an endogenous modulator of the constitutively activated phenotype of pulmonary adventitial fibroblasts in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L1–L11. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00050.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shimazaki M, Nakamura K, Kii I, et al. Periostin is essential for cardiac healing after acute myocardial infarction. J Exp Med. 2008;205:295–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Crawford J, Nygard K, Gan BS, et al. Periostin induces fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast persistence in hypertrophic scarring. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24:120–126. doi: 10.1111/exd.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen Y, Abraham DJ, Shi-Wen X, et al. CCN2 (connective tissue growth factor) promotes fibroblast adhesion to fibronectin. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5635–5646. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dobaczewski M, Bujak M, Li N, et al. Smad3 signaling critically regulates fibroblast phenotype and function in healing myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2010;107:418–428. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xu H, Li P, Liu M, et al. CCN2 and CCN5 exerts opposing effect on fibroblast proliferation and transdifferentiation induced by TGF-beta. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2015;42:1207–1219. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu S, Shi-wen X, Abraham DJ, et al. CCN2 is required for bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:239–246. doi: 10.1002/art.30074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Leask A. Getting to the heart of the matter: new insights into cardiac fibrosis. Circ Res. 2015;116:1269–1276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kim KH, Chen CC, Monzon RI, et al. Matricellular protein CCN1 promotes regression of liver fibrosis through induction of cellular senescence in hepatic myofibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2078–2090. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00049-13. An important study that documents anti-fibrotic effects of the matricellular protein CCN1 in the liver in models of carbon tetrachloride intoxication and bile duct ligation

- 104.Borkham-Kamphorst E, Schaffrath C, Van de Leur E, et al. The anti-fibrotic effects of CCN1/CYR61 in primary portal myofibroblasts are mediated through induction of reactive oxygen species resulting in cellular senescence, apoptosis and attenuated TGF-beta signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:902–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yoon PO, Lee MA, Cha H, et al. The opposing effects of CCN2 and CCN5 on the development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]