Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether screening for malnutrition using the validated malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST) identifies specific characteristics of patients at risk, in patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (GEP-NET).

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire NHS Trust; European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society Centre of Excellence.

Participants

Patients with confirmed GEP-NET (n=161) of varying primary tumour sites, functioning status, grading, staging and treatment modalities.

Main outcome measure

To identify disease and treatment-related characteristics of patients with GEP-NET who score using MUST, and should be directed to detailed nutritional assessment.

Results

MUST score was positive (≥1) in 14% of outpatients with GEP-NET. MUST-positive patients had lower faecal elastase concentrations compared to MUST-negative patients (244±37 vs 383±20 µg/g stool; p=0.018), and were more likely to be on treatment with long-acting somatostatin analogues (65 vs 38%, p=0.021). MUST-positive patients were also more likely to have rectal or unknown primary NET, whereas, frequencies of other GEP-NET including pancreatic NET were comparable between MUST-positive and MUST-negative patients.

Conclusions

Given the frequency of patients identified at malnutrition risk using MUST in our relatively large and diverse GEP-NET cohort and the clinical implications of detecting malnutrition early, we recommend routine use of malnutrition screening in all patients with GEP-NET, and particularly in patients who are treated with long-acting somatostatin analogues.

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumours, malnutrition, somatostatin analogues, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, MUST malnutrition universal screening tool

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study investigates the important clinical problem of malnutrition screening in patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (GEP-NET).

Possible implications of the use of somatostatin analogues on the risk of malnutrition in patients with GEP-NET have not been reported in previous studies.

Strengths of the study include the relatively large size of a well characterised diverse cohort of patients with GEP-NET, including information about tumour grading, staging, functioning status, biomarkers and treatment modalities.

Limitations include the observational, real-world nature of this study, with attendant limitations on availability of data subsets and power in regression analyses.

Introduction

Malnutrition is caused by insufficient delivery of nutrients, or increased catabolism, and is linked to major negative outcomes including excess morbidity, mortality and higher treatment costs.1–4 The prevalence of malnutrition in patients with cancer has been reported to range between 30% and 70%, depending on tumour type, stage and treatment modalities,5 but might be different in patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (GEP-NET).

GEP-NET comprise a complex group of often slow-growing neoplasms that are derived from primitive endocrine and neural cells. The annual incidence of GEP-NET has recently tripled to 40–50 cases per million, which is thought to be at least, in part, related to increased awareness and improved diagnostic modalities.6 Malnutrition in patients with GEP-NET might be frequent for various reasons which include functioning tumours producing hormones that affect gut transit,7–9 pancreatic masses, tumour infiltration of the mesentery in midgut NET,10 11 prior abdominal surgery, or treatment with somatostatin analogues.12–14

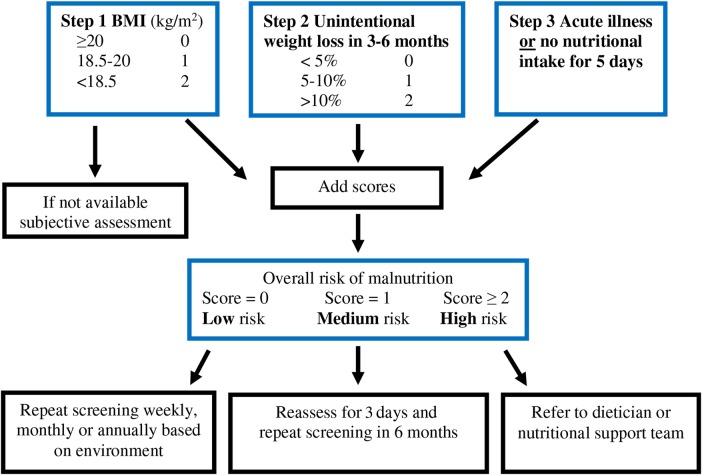

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends malnutrition screening in all adult inpatients and outpatients in at-risk groups.2 Several screening tools of varying complexity have been developed.5 The malabsorption universal screening tool (MUST) is one of the more commonly used screening methods in UK NHS Trusts, due to its simplicity and previous validation in multiple settings including use in patients with cancer2 15–17 (figure 1). However, the potential utility of malnutrition screening in patients with GEP-NET was only reported in a single very recent study to date.18

Figure 1.

Simplified scheme of use of the MUST score (adapted from BAPEN15). MUST was positive in 14.2% of the screened patients (23/161 patients with GEP-NET). The majority of the patients with positive MUST scored 1 (n=14) or 2 (n=7), mostly related to BMI <20 kg/m2 (n=16) and/or, less frequently, recent weight loss (n=9). Only n=2 of the patients in the entire cohort had a MUST score of ≥3. MUST, malnutrition universal screening tool; GEP-NET, gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours; BMI, body mass index.

Here, in a cohort of 161 patients with confirmed GEP-NET of varying primary tumour sites, grading, staging, functioning status and treatment modalities, we explored the prevalence of malnutrition, and whether MUST-positive GEP-NET patients showed specific disease or treatment-related characteristics.

Materials and methods

Participants and sample collection

The University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust (UHCW) audit department approved the study (audit number 1133/2015; July 2015). Data were obtained from the local data base at the ARDEN NET centre, European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) Centre of Excellence (CoE) in UHCW. All patients with GEP-NET who attend their routine clinical appointments in the ARDEN NET Centre are screened using MUST since May 2015; and were eligible for inclusion.

Patients had physical examination as part of routine clinical care and were characterised according to age, gender, body weight, body height, body mass index (BMI), the location of the primary tumour, staging, histological grading (surgical sample or diagnostic biopsy), presence or absence of functioning symptoms (ie, flushing or diarrhoea), treatment modalities received, for example, treatment with somatostatin analogues, information about prior abdominal surgery GEP-NET-related or for any reason, and GEP-NET-related biomarkers (most recent overnight fasted gut hormone profile from within the previous 6 months including Chromogranin A; other biomarkers such as Chromogranin B, gastrin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), somatostatin, glucagon and pancreatic polypeptide were available but only used for clinical decision-making when appropriate. Samples for 24 h urine were obtained following restriction of known factors that can cause false high measurements of urinary 5-HIAA. Further characteristics such as biomarkers for screening for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency or heart failure were used if available for clinical reasons. Using the available data a MUST score was calculated. A simplified scheme of the use of the MUST score is depicted in (figure 1).

Measurement of biomarkers

Routine biochemical markers were performed in the biochemistry laboratory at UHCW. Plasma gut hormone profiles were sampled after at least 10 h of overnight fast. Analyses were performed by radioimmunoassay at Hammersmith Hospital. Analyses for 5-HIAA were performed using HPLC at Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham. Faecal elastase-1 concentration in stools was determined using an ELISA (ScheBo Pancreatic Elastase-1 Stool Test), measured at City Hospital, Birmingham, UK. The human faecal elastase-1 antibody used here is immunologically specific and is not affected by enzyme replacement therapies. A faecal elastase concentration<200 µg/g stool indicates moderate, and a concentration<100 µg/g stool indicates severe exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean±SE. Metric values were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and further analysed using the paired t test. Non-normally distributed metric variables and ordinally scaled variables were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. For nominally scaled variables, χ2 tests were applied. Ordinal data were correlated using Spearman's analyses (based on 1000 bootstrap samples) to assess the associations between variables. Owing to the relatively small number of patients in the respective subgroups, all MUST-positive patients were pooled for comparison with MUST-negative patients. Breusch Pagan test and auxiliary regressions were used to investigate for heteroscedasticity and significant relationships between fitted predicted values and squared residuals. Bootstrapped ordinal regression analyses (set as 1000 bootstrap samples) were performed with MUST score (positive vs negative) as the dependent variable and age, tumour stage, prior abdominal surgery (separately for any prior abdominal surgery or GEP-NET-related surgery, ie, ileocaecal resection or right hemicolectomy), functioning status, treatment and duration of treatment (in month) with somatostatin analogues and GEP-NET-related biomarkers (normal or pathological) as the independent variables, based on biological plausibility to potentially cause malabsorption; bootstrapped p values are provided. Backward stepwise binary logistic regression analyses were additionally used to assess the influence of individual variables on MUST score. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.22 (Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

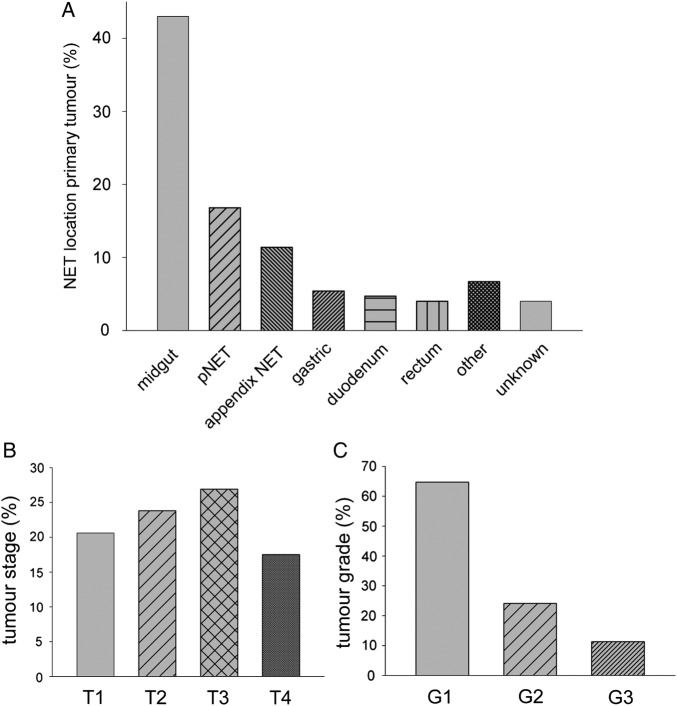

MUST data were available in n=161 patients of the GEP-NET cohort in the ARDEN NET centre. The cohort comprised 74 men and 87 women. Age was 63.2±1.2 years, body weight 75±1.4 kg, body height 167±0.01 cm, BMI 26.7±0.4 kg/m2, and serum creatinine 85.1±3.5 µmol/L. Previous abdominal surgery for any reason had been performed in n=96 (59.6%) of the patients. Previous ileocaecal resection was done in n=17 (10.6%), and right hemicolectomy in n=14 (8.7%) of the patients. Histological grading was available in n=133 (82.6%) of the patients, if performed for clinical reasons; of those, n=86 (64.7%) had a grade 1 well differentiated (G1) GEP-NET; n=32 (24.1%) had a grade 2 well differentiated (G2) GEP-NET; and n=15 (11.3%) had a poorly differentiated (G3) neuroendocrine carcinoma of gastro-entero-pancreatic origin. Out of the 161 NET patients in this cohort, n=67 (41.6%) were on treatment with somatostatin analogues (Sandostatin LAR 30 mg once monthly; or Somatuline Autogel 120 mg once monthly); of those, n=43 (65.2%) had a well differentiated midgut NET, and n=14 (21.2%) had a well differentiated pancreatic NET. Mean duration of treatment with somatostatin analogues in the n=67 treated patients was 19.5±3.3 months at the time of data collection. Of the 15 patients in the GEP NET cohort with pathological faecal elastase concentrations (<200 µg/g stool; 96.1±18.9 µg/g stool), n=12 had previous abdominal surgery (any), n=7 had a pNET, n=3 had previous ileocaecal resection, and n=1 had previous right hemicolectomy. Further tumour characteristics of the cohort are shown in (figure 2A–C).

Figure 2.

Characteristics of the GEP-NET cohort. (A) location of the primary tumour, (B) distribution of tumour staging, with the remaining 11.2% of the patients being classified as Tx (no signs of primary tumour), (C) histological grading (well differentiated, grade 1 and 2; poorly differentiated, grade 3). GEP-NET, gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours.

Patients scoring positive using MUST

Fourteen per cent of the GEP-NET patients (n=23/161) scored ≥1 using MUST, which classifies the patient as ‘medium risk for malnutrition’, and should trigger a recommendation of ‘further observation’ of nutrition status according to BAPEN/NICE guidelines;2 16 and 5.5% of the patients scored ≥2 (n=9/161), which classifies the patient as ‘high risk for malnutrition’ and should trigger treatment of malnutrition and, ideally, referral to the dieticians or multidisciplinary nutrition team.16

Correlation analyses

Spearman analyses (based on 1000 bootstrap samples) showed a moderate but statistically significant negative correlation of total MUST score (positive vs negative) with faecal elastase concentrations (r=−0.32, p=0.005), and a weak but statistically significant positive correlation with treatment with somatostatin analogues (r=0.20, p=0.013). Duration of treatment with somatostatin analogues showed a weak trend with total MUST score (r=0.14; p=0.078). None of the remaining markers significantly correlated with MUST total score in bootstrapped regression analyses, which included age, gender, functioning status, tumour grade, tumour stage, biomarkers in blood and urine, serum creatinine, BNP, prior abdominal surgery (any), and prior ileocaecal resection or right hemicolectomy (all p>0.13).

Regression analyses

Bootstrapped binary logistic regression analyses in the complete model identified use of somatostatin analogues (exp (B)=0.022; 95% CI (0.000 to 1.554); p=0.004), faecal elastase concentrations (exp (B)=0.992; 95% CI (0.984 to 1.001); p=0.009)), age (exp (B)=0.901; 95% CI (0.781 to 1.038; p=0.010) and tumour stage (≥T2; p<0.044); and presence of distant metastatic disease M1 (p=0.037); but not N1) as significant predictors of MUST score. Duration of treatment with somatostatin analogues was not a significant predictor, neither in bootstrapped nor in conventional analyses (p=0.11 and p=0.63, respectively). The regression model was statistically significant (χ2 26.58; p=0.046). The model explained 57% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in MUST, and correctly identified 95.5% of MUST-negative and 44.4% of MUST-positive subjects.

To obtain additional information about the influence of individual dependent variables, additional backward stepwise binary logistic regression analyses were tested. In step 6 of this stepwise model, again 44.4% of MUST-positive patients and 97% of MUST-negative patients were correctly identified, with use of somatostatin analogues, but not other factors including the duration of treatment with somatostatin analogues remaining a statistically significant predictor (p<0.001; χ2 test 21.98, p=0.009), and explaining 49% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in MUST. Again, duration of treatment with somatostatin analogues did not influence the variance in the MUST score (p>0.595 in all tested models).

Use of somatostatin analogues (yes vs no) in bootstrapped analyses with location of the primary tumour, tumour grade, tumour stage and functioning status as the independent variables was predicted by functioning status (p=0.011), tumour grade (p<0.032) and presence of distant metastases (M1, p=0.035), with location of the primary tumour showing a trend. The model explained 55% of the variance in use of somatostatin analogues and reasonably correctly predicted both treated (84.2%) and untreated (78.3%) patients (χ2 66.35, p<0.001).

Characteristics of MUST-positive compared with MUST-negative patients

Specific characteristics of GEP-NET patients with a positive as compared with a negative MUST scores are shown in (table 1). GEP-NET patients who scored ≥1 using MUST were significantly more frequently treated with somatostatin analogues as compared with patients who did not score using MUST (65% vs 38%; p=0.021) (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of MUST-positive compared with MUST-negative patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours of varying primaries, tumour grading, staging and functioning status

| MUST-positive n=23 |

MUST-negative n=138 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment with SSA (%) | 65 | 38 | 0.021 |

| Faecal elastase (µg/g stool) | 244±37 | 383±20 | 0.018 |

Data are given as mean±SE.

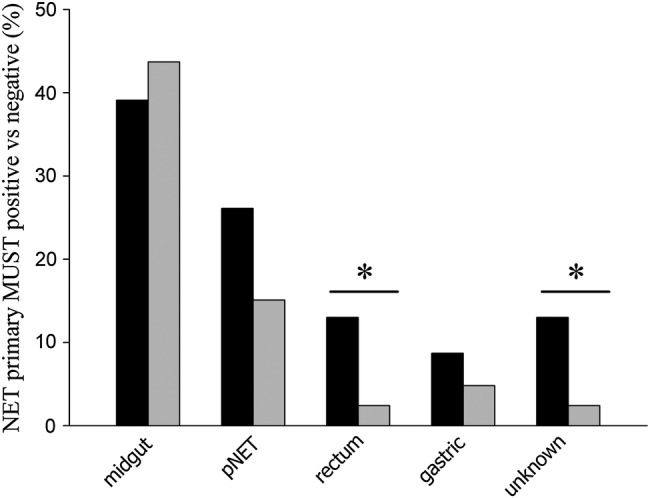

MUST, malnutrition universal screening tool; SSA, long-acting somatostatin analogues.

When stratifying the entire cohort according to treatment with somatostatin analogues, 22.4% (n=15 of 67 patients) who were treated with somatostatin analogues scored ≥1 using MUST, as compared to 8.5% (n=8 of 94 patients) who were not on treatment with somatostatin analogues (p=0.013). MUST-positive patients showed significantly lower faecal elastase levels, as compared with MUST-negative patients (table 1). Faecal elastase concentrations also tended to be lower in patients who were on treatment with somatostatin analogues, as compared with patients who were not on treatment with somatostatin analogues (335±26 vs 402±27 µg/g stool; p=0.075). Finally, patients who scored using MUST had significantly more often NET of the rectum or of unknown origin, as compared with patients who did not score (figure 3). Frequencies of midgut NET (p=0.688), pancreatic NET (p=0.195) and gastric NET (p=0.443) were not significantly different between MUST-positive and MUST-negative patients (figure 3).

Figure 3.

MUST-positive compared with MUST-negative patients with GEP-NET. Patients who scored using MUST were significantly more likely to have rectum NET (p<0.017) or a NET with an unknown primary (p<0.017). Other types of NET were not significantly different between MUST-positive and MUST-negative patients, which included pancreatic NET (p=0.195). Black bars: MUST-positive patients; grey bars: MUST-negative patients. pNET, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour. MUST, malnutrition universal screening tool; GEP-NET, gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours; NET, neuroendocrine tumours.

Discussion

Malnutrition is an adjustable risk factor,19 but associated with severe adverse clinical outcomes if not addressed.1 2 Patients with GEP-NET do not typically present with major weight loss or acute illness before reaching the very final stages with extensive metastatic disease or carcinoid heart disease. This is related to the fact that GEP-NET are often slower growing and less aggressive tumours at least when well differentiated, as compared with other types of cancer.20 Nevertheless, malnutrition in patients with GEP-NET could be present for other reasons, including chronic loose stools, osmotic diarrhoea,20 and excess secretion of serotonin precursors stimulating small bowel motility.7–9 Pancreatic mass effects, tumour infiltration of the mesentery10 11 and GEP-NET-related treatment12–14 are further potential risk factors.

In our outpatient cohort of patients with various types of GEP-NET, 14% had a MUST score of >1, which should trigger referral to the dietitians and the nutrition support team.2 16 When comparing the cohort of patients who scored using MUST with the patients who did not score, we identified distinct characteristics of MUST-positive patients with GEP-NET. MUST-positive patients were more likely to have unknown primary or rectal NET, which might be related to delayed diagnosis and widespread disease in these patients. Furthermore, MUST-positive patients showed significantly lower faecal elastase concentrations, although the frequency of pancreatic NET was not significantly different between groups, arguing against possible pancreatic mass effects as the main driving factor. Most importantly, MUST-positive patients were some twofold more likely to be on treatment with long-acting somatostatin analogues. After acute, short-term administration, rapid onset suppression of pancreatic exocrine secretion by somatostatin analogues21 22 and consequent steatorrhoea23 have been reported. Further known mechanisms are in agreement with a possible role of somatostatin analogues in conveying malnutrition in patients with GEP-NET, although it is important to mention that most previous reports refer to effects of acute administration of somatostatin analogues12 13 24 25 or in vitro studies,26 whereas effects after chronic administration23 might be differently related to possible adaptive mechanisms. Impairment of hepatic bile acid physiology by somatostatin analogues has been reported after both short-term27 and more prolonged administration, and is causally involved in gallstone formation.28 In the acute setting, intravenous somatostatin inhibits glucose, triglyceride, amino acid and calcium absorption by direct effects on the intestinal mucosa;12 13 24 and decreases gastric acid secretion by 90% in healthy volunteers.24 In addition, acute suppression or in vitro effects of various gut hormones, such as cholecystokinin and glucagon-like peptide-1 by somatostatin analogues are well described,23 25 26 and diarrhoea, steatorrhoea and weight loss are key features of excess hormone-producing somatostatinomas.29 Possible implications of treatment with somatostatin analogues on other aspects such as loss of fat-soluble vitamins in the faeces have been also reported.30 It might be argued that patients who were treated with long-acting somatostatin analogues were more prone to score using MUST related to functioning status and advanced disease progression, as well as general risk factors such as age and disease-related depression. However, treatment with somatostatin analogues remained a statistically significant predictor of MUST in all tested models. Importantly, duration of treatment with somatostatin analogues showed no significant influence in our analyses, indicating that acute effects of the administration of somatostatin analogues on the likelihood scoring positive in the MUST score were sustained after longer term treatment, and somewhat arguing against adaptive mechanisms in this context.

Our observed total rate of patients at risk of malnutrition was somewhat lower than the prevalence very recently reported by Maasberg et al18 in a neuroendocrine cohort of comparable size. Authors identified some 21%–25% of the patients at risk,18 as compared to 14% in our study; however, the cohort in the mentioned study comprised 87% inpatients and also included patients with neuroendocrine tumours of the lung, as compared with our study, which was exclusively assessed in outpatients with GEP-NET. This may explain the lower frequency of patients at risk of malnutrition in our cohort.

The observational nature of this study needs to be mentioned as a limitation, as well as its relatively small sample sizes when including not routinely measured biomarkers in the regression models. Our study confirms the importance of screening for malnutrition in patients with GEP-NET. This is directly clinically relevant, considering that malnutrition in patients with neuroendocrine tumours could be an independent prognostic factor.18 Confirmation of our findings in multicentre settings with access to large and diverse GEP-NET patient cohorts will be useful.

In summary, somatostatin analogues are key treatment modalities in patients with well-differentiated GEP-NET, but may cause transient or permanent gastrointestinal side effects such as bloating and cramping in up to 30% of the patients;31–33 and, based on our findings, appear to increase malnutrition risk as identified by MUST. Without systematically screening GEP-NET patients for malnutrition, mild impairment of digestive processes might be missed or attributed to functioning aspects of the GEP-NET, rather than recognised and treated as a possible side effect of the treatment. Referring these patients for early nutritional intervention could lead to improvement of the nutritional status and quality of life.34

Footnotes

Contributors: MOW, NB and SAQ were involved in the study concept and design. SK, KG, JLHW, LD, SF, WS and SS were involved in the acquisition of clinical data. CD was involved in the analyses of biochemical markers. SAQ, NB, LD, GKD and MOW were involved in the collection of MUST data. MOW and JGH did the statistical analyses. MOW and MD supervised the MSc project of SAQ. MD provided important intellectual content and critical review of the manuscript. SAQ provided input to the first draft of the manuscript. MOW drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically revised it for important intellectual content. MOW supervised the study and is the guarantor. The authors thank Ms Josie Goodby for support with data collection.

Funding: This research was funded by the ARDEN NET Centre in UHCW, ENETS CoE (development grant from R&D UHCW to MOW, June 2015). The study did not receive a specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The UHCW audit department had approved this study (audit number 1133/2015; July 2015). All study data were accessed using techniques compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), and, because this study involved analysis of pre-existing, deidentified data, it was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Barker LA, Gout BS, Crowe TC. Hospital malnutrition: prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:514–27. 10.3390/ijerph8020514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.32 Ncg. Nutrition support in adults: Oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition. 2006. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg32 (accessed 3 Dec 2015). [PubMed]

- 3.de Ulibarri Perez JI, Picon Cesar MJ, Garcia Benavent E et al. . [Early detection and control of hospital malnutrition]. Nutr Hosp 2002;17:139–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stratton RJ, Hackston A, Longmore D et al. . Malnutrition in hospital outpatients and inpatients: prevalence, concurrent validity and ease of use of the ‘malnutrition universal screening tool’ (‘MUST’) for adults. Br J Nutr 2004;92:799–808. 10.1079/BJN20041258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isenring E, Elia M. Which screening method is appropriate for older cancer patients at risk for malnutrition? Nutrition 2015;31:594–7. 10.1016/j.nut.2014.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinik AI, Woltering EA, Warner RR et al. . NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor. Pancreas 2010;39:713–34. 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebaffd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman JM, Plonk JW. Gastrointestinal and metabolic function in patients with the carcinoid syndrome. Am J Med Sci 1977;273:43–54. 10.1097/00000441-197701000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oosterbosch L, von der Ohe M, Valdovinos MA et al. . Effects of serotonin on rat ileocolonic transit and fluid transfer in vivo: possible mechanisms of action. Gut 1993;34:794–8. 10.1136/gut.34.6.794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ter-Minassian M, Chan JA, Hooshmand SM et al. . Clinical presentation, recurrence, and survival in patients with neuroendocrine tumors: results from a prospective institutional database. Endocr Relat Cancer 2013;20:187–96. 10.1530/ERC-12-0340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aspestrand F, Pollard L. Carcinoid infiltration and fibroplastic changes of the mesentery as a cause of malabsorption. Radiologe 1986;26:79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nash DT, Brin M. Malabsorption in malignant carcinoid with normal 5 Hiaa. N Y State J Med 1964;64:1128–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evensen D, Hanssen KF, Berstad A. The effect on intestinal calcium absorption of somatostatin in man. Scand J Gastroenterol 1978;13:449–51. 10.3109/00365527809181920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krejs GJ, Browne R, Raskin P. Effect of intravenous somatostatin on jejunal absorption of glucose, amino acids, water, and electrolytes. Gastroenterology 1980;78:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V, Barbara G et al. . Clinical approach to diarrhea. Intern Emerg Med 2012;7(Suppl 3):S255–62. 10.1007/s11739-012-0827-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.BAPEN. Introducing “MUST”. 2015. http://www.bapen.org.uk/screening-for-malnutrition/must/introducing-must (accessed 03 Dec 2015).

- 16.(MAG) MAG. MAG screening tool and guidelines set to combat malnutrition. 2001. http://www.guidelinesinpractice.co.uk/feb_01_elia_malnutrition_feb01#.Vg1JSTZdFMt (accessed 26 Feb 2016).

- 17.Boleo-Tomé C, Monteiro-Grillo I, Camilo M et al. . Validation of the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) in cancer. Br J Nutr 2012;108:343–8. 10.1017/S000711451100571X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maasberg S, Knappe-Drzikova B, Vonderbeck D et al. . Malnutrition predicts clinical outcome in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasias. Neuroendocrinology 2015. [epub ahead of print 8 Dec 2015]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris D, Haboubi N. Malnutrition screening in the elderly population. J R Soc Med 2005;98:411–14. 10.1258/jrsm.98.9.411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinik A, Feliberti E, Perry RR. Carcinoid tumors. In: De Groot LJ, Beck-Peccoz P, Chrousos G et al., eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25905385 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boden G, Sivitz MC, Owen OE et al. . Somatostatin suppresses secretin and pancreatic exocrine secretion. Science 1975;190:163–5. 10.1126/science.1166308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopman WP, van Liessum PA, Pieters GF et al. . Pancreatic exocrine and gallbladder function during long-term treatment with octreotide (SMS 201-995). Digestion 1990;45(Suppl 1):72–6. 10.1159/000200266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho PJ, Boyajy LD, Greenstein E et al. . Effect of chronic octreotide treatment on intestinal absorption in patients with acromegaly. Dig Dis Sci 1993;38:309–15. 10.1007/BF01307549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamrani A, Vidon N, Sogni P et al. . Effects of lanreotide, a somatostatin analogue, on postprandial gastric functions and biliopancreatic secretions in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997;43:65–70. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1997.tb00034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlegel W, Raptis S, Harvey RF et al. . Inhibition of cholecystokinin-pancreozymin release by somatostatin. Lancet 1977;2:166–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(77)90182-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chisholm C, Greenberg GR. Somatostatin-28 regulates GLP-1 secretion via somatostatin receptor subtype 5 in rat intestinal cultures. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2002;283:E311–17. 10.1152/ajpendo.00434.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnusson I, Einarsson K, Angelin B et al. . Effects of somatostatin on hepatic bile formation. Gastroenterology 1989;96:206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussaini SH, Pereira SP, Veysey MJ et al. . Roles of gall bladder emptying and intestinal transit in the pathogenesis of octreotide induced gall bladder stones. Gut 1996;38:775–83. 10.1136/gut.38.5.775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinik A, Feliberti E, Perry RR. Somatostatinoma. In: De Groot LJ, Beck-Peccoz P, Chrousos G et al., eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25905263 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiebrich HB, Van Den Berg G, Kema IP et al. . Deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins in long-term users of somatostatin analogue. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:1398–404. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04479.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lembcke B, Creutzfeldt W, Schleser S et al. . Effect of the somatostatin analogue sandostatin (SMS 201-995) on gastrointestinal, pancreatic and biliary function and hormone release in normal men. Digestion 1987;36:108–24. 10.1159/000199408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caplin ME, Pavel M, Ćwikła JB et al. . Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 2014;371:224–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1316158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rinke A, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C et al. . Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: a report from the PROMID Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4656–63. 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paccagnella A, Morassutti I, Rosti G. Nutritional intervention for improving treatment tolerance in cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol 2011;23:322–30. 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283479c66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]