Abstract

Mason–Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) and spleen necrosis virus (SNV) are simple retroviruses that encode functionally divergent cis-acting RNA elements that use cellular proteins to facilitate nuclear export and translation of unspliced viral RNA. We tested the hypothesis that a combination of MPMV constitutive transport element (CTE) and SNV or MPMV RU5 translational enhancer on unspliced HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA synergistically augments Gag production. Results of transient transfection assays validate the hypothesis of synergistic augmentation in COS cells, but not 293 cells. RNA targeting experiments verified comparable responsiveness to CTE-interactive proteins tethered by RRE and RevM10Tap in COS and 293 cells. Exogeneous expression of Tap and NXT1 was necessary and sufficient to rescue Gag augmentation in 293 cells. Overexpression experiments established that CTE, but not RU5, confers the responsiveness to Tap and NXT1 and that CTE in conjunction with Tap and NXT1 conferred a 30-fold increase in translational utilization of the cytoplasmic RNA. Our results uncovered a previously unidentified role of CTE in conjunction with Tap and NXT1 in commitment to efficient cytoplasmic RNA utilization.

Keywords: Posttranscriptional control, SNV RU5, MPMV CTE, Cytoplasmic utilization, HIV-1 unspliced RNA

Introduction

For typical cellular mRNAs, the removal of intronic sequences from pre-mRNA is coupled to nuclear export (Luo and Reed, 1999; Luo et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2000). As a consequence of intron removal, a multiprotein exon junction complex (EJC) is deposited near the exon–exon junction (Le Hir et al., 2000a,b). The EJC facilitates interaction with nuclear export factor Tap and essential cofactor NXT1, which translocate fully processed mRNAs across the nuclear pore (Le Hir et al., 2001; Rodrigues et al., 2001; Stutz et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2000). By contrast, retroviral pre-mRNA can achieve nuclear export independently of intron removal. Retroviral pre-mRNA is utilized as a template for synthesis of Gag and Pol structural and enzymatic proteins and also as genomic RNA that is packaged into progeny virions (Butsch and Boris-Lawrie, 2002). To facilitate nuclear export of viral unspliced RNA, Mason–Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) and the highly related simian retrovirus type 1 directly recruit mRNA export factors Tap and NXT1. Instead of recruitment to the EJC, Tap and NXT1 are recruited to a cis-acting RNA element located in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) that is termed the constitutive transport element (CTE) (Braun et al., 1999; Gruter et al., 1998; Kang et al., 2000; Guzik et al., 2001).

The CTE was initially identified by its ability to facilitate nuclear export of unspliced HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA in transiently transfected monkey COS cells (Bray et al., 1994; Zolotukhin et al., 1994). Subsequently, human Tap was shown to be necessary and sufficient for CTE-mediated RNA export in a nonpermissive quail cell line (Kang and Cullen, 1999). Binding assays demonstrate that NXT1 enhances the association of Tap with a variety of nucleoporins, including CAN/Nup214, Nup153, Nup98, p62, and CG1 (Bachi et al., 2000; Levesque et al., 2001; Wiegand et al., 2002; Kang et al., 2000). RNA-protein tethering experiments have demonstrated that Tap-NXT1 heterodimers augment expression of target intron-containing reporter RNAs in mammalian cells (Guzik et al., 2001; Levesque et al., 2001).

A growing body of literature indicates that nuclear proteins can also modulate translation of cytoplasmic mRNA. Experiments in Xenopus oocytes have demonstrated that removal of an intron positioned 5′ of the open reading frame stimulates translational efficiency compared to an intronless reporter RNA (Matsumoto et al., 1998). In contrast, removal of an intron positioned 3′ of the open reading frame represses translational efficiency compared to an intronless reporter RNA. Wolffe and colleagues speculate that position-dependent recognition of an intron in the nucleus recruits a particular ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex that determines the translational fate of mRNA in the cytoplasm. Consistent with this notion, several EJC proteins remain associated with the mRNP complex upon nuclear export. Of these, Y14 remains associated with mRNA in polysome profile fractions and is speculated to provide a protein imprint that modulates the utilization of cytoplasmic RNA (Dostie and Dreyfuss, 2002). Other EJC proteins mark mRNAs that contain a premature translation termination codon for nonsense-mediated decay in the cytoplasm after a pioneer round of translation (Kim et al., 2001a,b; Le Hir et al., 2001; Dostie and Dreyfuss, 2002; Lykke-Andersen et al., 2000, 2001; Schell et al., 2002). Recently, nuclear protein Sam68 was shown to enhance cytoplasmic utilization of intron-containing retroviral RNA (Coyle et al., 2003).

At least two retroviruses, MPMV and the divergent avian spleen necrosis virus (SNV), contain a 5′ proximal posttranscriptional control element in the RU5 region of the 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) that modulates translation (Butsch et al., 1999; Hull and Boris-Lawrie, 2002; Roberts and Boris-Lawrie, 2000). Ribosomal sedimentation and ribosome profile analyses have established that SNV and MPMV RU5 enhance translation of HIV-1 gag-pol and nonviral luc reporter RNAs by augmentation of ribosome loading (Butsch et al., 1999; Hull and Boris-Lawrie, 2002; Roberts and Boris-Lawrie, 2000). Quantitative RNA and protein analyses of SNV and MPMV LTR mutants that contain a deletion of RU5 but sustain the U3 promoter region detected minimal change in the steady-state level or cytoplasmic accumulation of HIV-1 gag-pol and luc reporter RNAs despite significant reductions in HIV-1 Gag and Luc protein production. These results together with RNA transfection assays and competition experiments with HIV Rev and the Rev responsive element (RRE) (Dangel et al., 2002) indicate that a nuclear protein(s) imprints RU5-containing transcripts for productive interaction with the translational machinery. The identity of the nuclear protein(s) and their relationship to nuclear export remains to be determined.

To address the relationship between nuclear export and translational enhancement, we tested the hypothesis that SNV or MPMV RU5 function compatibly with MPMV CTE to synergistically augment protein production from unspliced HIV-1 gag-pol RNA. MPMV CTE and either SNV or MPMV RU5 were combined on a single HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA and quantitative RNA and protein analyses were performed on transiently transfected cells.

Results

Synergistic augmentation of Gag production by MPMV CTE and SNV RU5 in COS cells

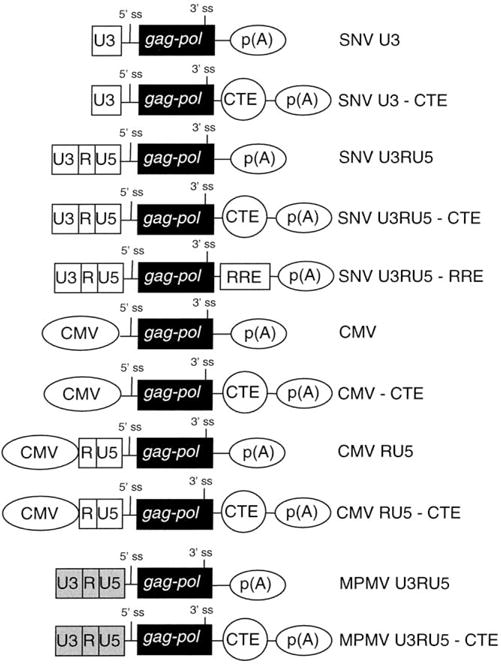

To evaluate potential synergism between MPMV CTE and SNV RU5, we analyzed a panel of HIV-1 gag-pol reporter plasmids (Fig. 1). HIV-1 Gag production was quantified by Gag ELISA on cell-associated protein in triplicate transient transfections of COS cells. The reference plasmid, SNV U3, lacks both MPMV CTE and SNV RU5 and has been previously shown to support low, but detectable Gag production (Butsch et al., 1999). We evaluated Gag production in response to MPMV CTE and SNV RU5, both individually and in combination. As shown in two representative triplicate transfection assays, CTE augmented Gag production 11- to 16-fold (compare SNV U3 and SNV U3-CTE), while SNV RU5 augmented Gag production 3- to 4-fold (compare SNV U3 and SNV U3RU5) (Table 1). The combination of CTE and SNV RU5 produced an overall increase of 27- to 37-fold. The results affirm that MPMV CTE and SNV RU5 individually augment Rev/RRE-independent HIV-1 Gag production in COS cells. Furthermore, the combination of MPMV CTE and SNV RU5 synergistically augments Gag production in COS cells.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the structures of the gag-pol reporter plasmids. 5′ terminal labeled white or gray rectangles, U3, R, and U5 regions of the SNV LTR or MPMV LTR, respectively; 5′ -terminal oval labeled CMV, CMV immediate-early promoter-enhancer; labeled black rectangle, HIV-1 gag-pol reporter gene; labeled 5′ and 3′ ss, splice site; oval labeled CTE, MPMV constitutive transport element; rectangle labeled RRE, HIV-1 Rev responsive element; 3′ terminal oval labeled p(A), polyadenylation signal.

Table 1.

Gag protein production in COS cells

| Experiment | Reporter | Gag (ng/ml)a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SNV U3 | 2.6 ± 0.9 (1.0)b |

| SNV U3-CTE | 29.5 ± 4.4 (11.3) | |

| SNV U3RU5 | 8.1 ± 1.0 (3.1) | |

| SNV U3RU5-CTE | 70.9 ± 8.3 (27.2) | |

| 2 | SNV U3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 (1.0) |

| SNV U3-CTE | 30.7 ± 8.5 (16.1) | |

| SNV U3RU5 | 7.5 ± 0.9 (3.9) | |

| SNV U3RU5-CTE | 70.4 ± 11.3 (37.0) | |

| 1 | MPMV U3RU5 | 10.0 ± 1.8 (1.0) |

| MPMV U3RU5-CTE | 57.0 ± 18.1 (5.7) | |

| 2 | MPMV U3RU5 | 4.00 ± 0.8 (1.0) |

| MPMV U3RU5-CTE | 30.0 ± 6.7 (7.5) |

Cell-associated Gag levels measured from triplicate transfection of COS cells normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

Amounts in parentheses signify Gag level relative to SNV U3 or MPMV U3RU5 reporter plasmid.

Combination of MPMV CTE and SNV RU5 does not synergistically augment Gag production in 293 cells

We sought to determine whether or not the combination of MPMV CTE and SNV RU5 also synergistically augments Gag production in 293 cells given that previous characterization of SNV and MPMV RU5 was performed in this cell line (Butsch et al., 1999; Hull and Boris-Lawrie, 2002; Roberts and Boris-Lawrie, 2000). In 293 cells, SNV RU5 augmented Gag production five-fold, which is consistent with previous results (Table 2, compare SNV U3 and SNV U3RU5) (Butsch et al., 1999). Basal Gag production from the SNV U3 reporter plasmid was not augmented by CTE (compare SNV U3 and SNV U3-CTE). The combination of CTE and SNV RU5 did not synergistically augment Gag production and consistently exhibited reduced Gag production as compared to SNV RU5 alone. In contrast, CTE augmented Gag production from the pSVgagpol reporter plasmid that was used in the original identification of CTE in COS cells (Table 3, compare pSVgagpol and pSVgagpolMPMV CTE) (Bray et al., 1994). These results posit the model that SNV U3 impeded Gag augmentation from the SNV U3-CTE and SNV U3RU5-CTE reporter plasmids in 293 cells. To directly address whether SNV U3 was responsible, this sequence was replaced with the CMV immediate early promoter in four SNV U3-containing reporter plasmids (CMV, CMV-CTE, CMV RU5, CMV RU5-CTE) (Fig. 1). Results of triplicate transient transfection assays in 293 cells demonstrated that CTE augmented Gag production from the CMV derivatives (Table 3). Furthermore, the combination of MPMV CTE and SNV RU5 rescued an additive increase in Gag production. The results imply that the SNV U3 sequence impedes Gag augmentation in response to MPMV CTE in 293 cells.

Table 2.

Gag protein production in 293 cells

| Experiment | Reporter | Gag (ng/ml)a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SNV U3 | 9.5 ± 1.1 (1.0)b |

| SNV U3-CTE | 10.0 ± 0.6 (1.0) | |

| SNV U3RU5 | 47.0 ± 2.8 (5.0) | |

| SNV U3RU5-CTE | 22.5 ± 3.0 (2.3) | |

| 2 | SNV U3 | 9.2 ± 2.5 (1.0) |

| SNV U3-CTE | 8.7 ± 0.8 (0.9) | |

| SNV U3RU5 | 48.9 ± 9.7 (5.3) | |

| SNV U3RU5-CTE | 24.9 ± 2.9 (2.7) | |

| 1 | MPMV U3RU5 | 10.0 ± 0.6 (1.0) |

| MPMV U3RU5-CTE | 10.0 ± 0.9 (1.0) | |

| 2 | MPMV U3RU5 | 11.0 ± 1.0 (1.0) |

| MPMV U3RU5-CTE | 11.0 ± 0.8 (1.0) |

Cell-associated Gag levels measured from triplicate transfection of 293 cells normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

Amounts in parentheses signify Gag level relative to SNV U3 or MPMV U3RU5 reporter plasmid.

Table 3.

Gag production in response to CTE in 293 cells

| Plasmid | Gag (ng/ml)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Exp. 1 | Exp. 2 | |

| pSVgagpol | <MDb | <MD |

| pSVgagpolMPMV CTE | 13.0 ± 3.0 | 16.0 ± 2.0 |

| CMV | <MD | <MD |

| CMV-CTE | 12.0 ± 2.0 | 8.0 ± 2.5 |

| CMV RU5 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 5.0 ± 0.8 |

| CMV RU5-CTE | 17.0 ± 2.0 | 13.0 ± 2.0 |

Cell-associated Gag levels measured from triplicate transfections of 293 cells normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

<MD, less than minimum detectable (0.1 ng/ml).

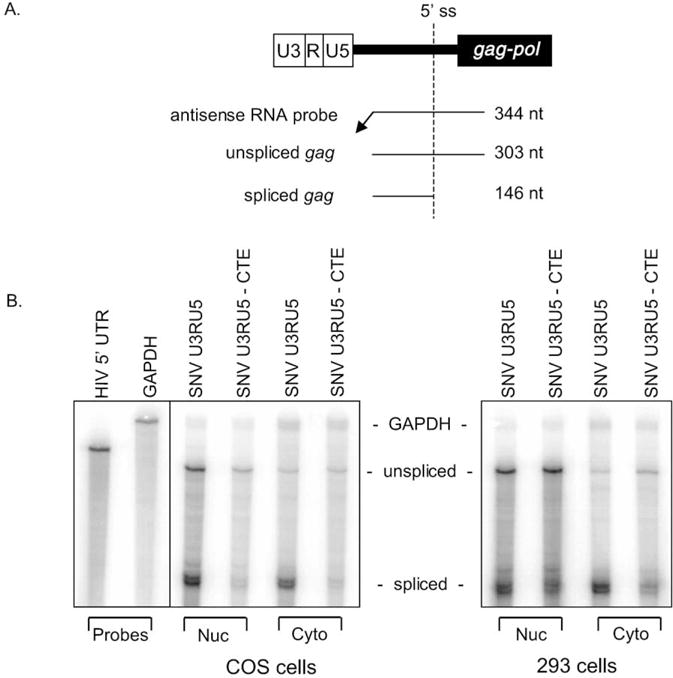

Differences in cytoplasmic utilization of SNV RU5gagCTE RNA are observed in COS and 293 cells

We sought to determine if the disparate response in Gag production upon the combination of SNV RU5 and MPMV CTE in COS and 293 cells is due to increased cytoplasmic utilization of the RU5gagCTE transcript in COS cells. Quantitative RPAs were performed on nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA fractionated by a hypotonic buffer protocol that was used previously to effectively separate Rev-dependent HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions (Hull and Boris-Lawrie, 2002). RPAs were performed with a uniformly labeled antisense HIV-1 RNA probe that detects both unspliced and spliced HIV-1 transcripts (Figs. 2A and B). The RNA signals were standardized to gapdh signal and cotransfected Luc values to control for minor differences in RNA loading and transfection efficiency. The CTE-containing unspliced RNA exhibited a lower steady-state level in the nucleus and an increased steady-state level in the cytoplasm in both COS and 293 cells. The relative level of cytoplasmic accumulation of the RU5gag reporter RNA was calculated as the ratio of unspliced gag RNA in the cytoplasm to that in the nucleus plus cytoplasm (Table 4). In both COS and 293 cells, CTE produced a similar and reproducible 2.5- to 3-fold increase in cytoplasmic accumulation of RU5gag reporter RNA. In addition, the efficiency of protein synthesis from the steady-state cytoplasmic gag RNA was calculated as the ratio of Gag protein to unspliced gag RNA in the cytoplasm and designated cytoplasmic utilization. The results demonstrated that MPMV CTE increased the cytoplasmic utilization of SNV RU5gag RNA five-fold in COS cells. However, in 293 cells, cytoplasmic utilization is reduced by a factor of 3. The results indicate that increased cytoplasmic accumulation of SNV RU5gagCTE RNA is not sufficient for augmented Gag production in 293 cells. Additionally, the disparate response in Gag production between COS and 293 cells upon the combination of SNV RU5 and MPMV CTE is attributable to increased cytoplasmic utilization of RU5gagCTE RNA in COS cells.

Fig. 2.

RNase protection assay (RPA) of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA detects comparable increases in cytoplasmic accumulation in response to CTE in COS and 293 cells despite discordant Gag production. (A) Relationship between the gag-pol reporter plasmid, the uniformly labeled antisense run-off HIV-1 5′ UTR RNA probe, and protected unspliced and spliced transcripts with sizes indicated. (B) Forty-eight hours posttransfection RNAs were isolated and treated with DNase. Nuclear (15 μg) and cytoplasmic (25 μg) RNAs were subjected to RPA with uniformly labeled antisense HIV-1 5′ UTR and gapdh RNA probes and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The RPAs were subjected to PhosphorImager analysis. Labels indicate the reporter plasmid, RNA preparation, protected transcripts, and cell line.

Table 4.

Analysis of HIV-1 gag reporter RNA in COS and 293 cellsa

| PhosphorImager units (105)b

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA preparation

|

Nuclear

|

Cytoplasmic

|

CAc

|

||||||

| Cells | Plasmid | Gage | Unspliced | Spliced | Unspliced | Spliced | Unspliced | Spliced | CUd |

| COS | SNV U3RU5 | 11.0 | 325.1 | 438.2 | 54.7 | 483.6 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.2 (1.0)f |

| SNV U3RU5-CTE | 72.0 | 145.7 | 148.9 | 73.2 | 147.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 (5.0) | |

| 293 | SNV U3RU5 | 46.0 | 277.1 | 675.4 | 77.5 | 468.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 (1.0) |

| SNV U3RU5-CTE | 18.0 | 103.9 | 142.2 | 93.1 | 143.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 (0.3) | |

Transfected COS or 293 cells were analyzed for Gag production and gag RNA expression.

RNA was extracted from transfected COS or 293 cells, treated with DNase, subjected to RNase protection assay with HIV-1 5′ UTR and gapdh probes and quantified by Phosphorimager analysis. The data are standardized to gapdh RNA level and cotransfected Luc values.

CA, cytoplasmic accumulation. Ratio of RNA level in cytoplasm relative to nucleus plus cytoplasm.

CU, cytoplasmic utilization. Ratio of Gag protein to unspliced cytoplasmic gag RNA.

Cell-associated Gag levels in nanograms per mililiter normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

Amounts in parentheses signify level relative to unspliced SNV U3RU5 reporter RNA.

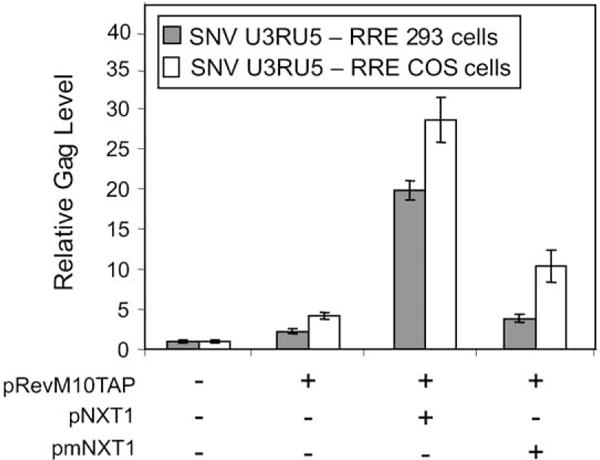

Targeting Tap and NXT1 to RU5gagRRE reporter RNA augments protein production in 293 and COS cells

We investigated the possibility that the CTE-interactive cellular proteins, Tap and NXT1, can rescue Gag augmentation from RU5gagCTE RNA in 293 cells. Previous studies have shown that targeting RevM10Tap and NXT1 to HIV-1 gagpo/RRE and nonviral catRRE reporter RNA augments protein production (Guzik et al., 2001; Levesque et al., 2001; Wiegand et al., 2002). We used this approach in a control experiment and verified that targeting RevM10Tap and NXT1 to RNA expressed from pSVgagpolRRE activates Gag production in both COS and 293 cells (data not shown). Furthermore, targeting RevM10Tap to SNV RU5gagRRE RNA increased Gag production two-fold in 293 cells and four-fold in COS cells (Fig. 3). Cotransfection of pRevM10Tap with pNXT1 further increased Gag production nine- and sevenfold in 293 and COS cells, respectively. Cotransfection of mutant NXT1 (pmNXT1) reduced Gag production to near baseline levels. The results demonstrate that SNV RU5gagRRE reporter RNA exhibits comparable responsiveness in COS and 293 cells and verify that RU5gag reporter RNA can respond to Tap and NXT1 that are tethered to RRE.

Fig. 3.

Tethering RevM10Tap and NXT1 to SNV RU5gagRRE RNA is sufficient to augment Gag production in 293 and COS cells. The SNV U3RU5-RRE reporter plasmid was cotransfected in triplicate with pRevM10Tap, pRevM10Tap and pNXT1, or pRevM10Tap and pmNXT1 (N48K, N50K). Cell-associated Gag levels were analyzed by ELISA, normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

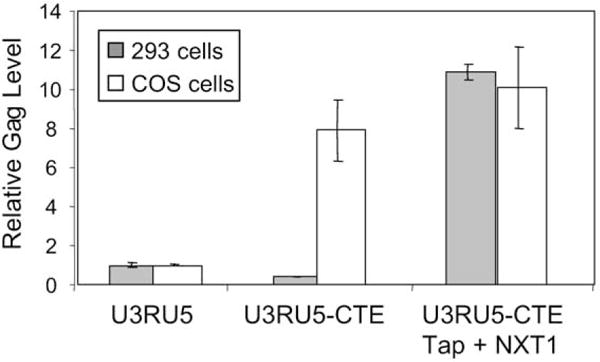

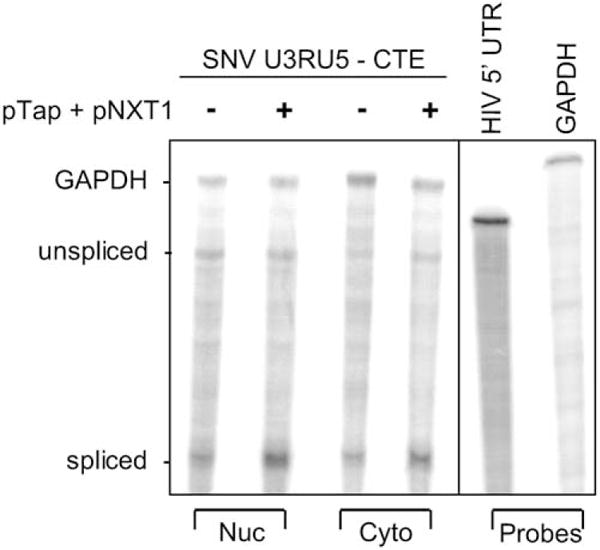

Tap and NXT1 rescue Gag augmentation in 293 cells by increasing cytoplasmic utilization

We investigated whether or not Gag augmentation in 293 cells from RU5gagCTE RNA can be rescued by overexpression of Tap and NXT1. We considered previous results that overexpression of Tap and NXT1 does not augment Gag production from SVgagpolCTE reportor RNA in COS, 293T, HeLa (Guzik al., 2001), or 293 cells (74,000 ± 2400 and 79,300 ± 270 minus and plus Tap/NXT1, respectively) (Hull and Boris-Lawrie, unpublished data). Therefore, augmentation of Gag production from RU5gagCTE RNA in an overexpression experiment in 293 cells would identify a variation in responsiveness to Tap and NXT1. Identical to results in Tables 1 and 2, introduction of CTE to RU5gag RNA increased Gag production in COS, but not in 293 cells (Fig. 4). In COS cells, exogenous expression of Tap and NXT1 did not produce an additional statistically significant increase in Gag production from SNV RU5gagCTE RNA. However, the SNV RU5gagCTE RNA exhibited a disparate response in 293 cells. Exogenous expression of Tap and NXT1 produced a significant 30-fold increase in Gag production from SNV RU5gagCTE RNA. The results demonstrate that exogenously expressed Tap and NXT1 are necessary and sufficient to rescue Gag augmentation from SNV RU5gagCTE RNA in 293 cells.

Fig. 4.

Combined overexpression of Tap and NXT1 is necessary to rescue Gag augmentation from RU5gagCTE RNA in 293, but not COS cells. The SNV U3RU5 and SNV U3RU5-CTE alone or cotransfected with pTap and pNXT1 were transfected in triplicate into 293 and COS cells. Cell-associated Gag levels were analyzed by ELISA and normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

Quantitative RNA analysis was performed to determine whether overexpression of Tap and NXT1 augmented Gag production in 293 cells by increasing nuclear export or cytoplasmic utilization of SNV RU5gagCTE RNA. As shown in a representative RPA (Fig. 5) and quantified in Table 5, overexpression of Tap and NXT1 had minimal effect on the absolute level and overall cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced SNV RU5gagCTE RNA. These data stand in sharp contrast to the 30-fold increase in Gag protein production. These results demonstrate that exogenous expression of Tap and NXT1 did not increase Gag production by increasing export of the RNA, but rather by increasing cytoplasmic utilization of the SNV RU5gagCTE RNA.

Fig. 5.

RNase protection assay (RPA) of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA reveals that combined overexpression of Tap and NXT1 does not increase cytoplasmic accumulation of SNV RU5gagCTE RNA in 293 cells. Forty-eight hours posttransfection RNAs were isolated and treated with DNase. Nuclear (15 μg) and cytoplasmic (25μg) RNAs were subjected to RPA with uniformly labeled antisense HIV-1 5′ UTR and gapdh RNA probes and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The RPA was subjected to Phosphorlmager analysis. Labels indicate the reporter plasmid, RNA preparation, and protected transcripts.

Table 5.

Analysis of HIV-1 gag reporter RNA in 293 cellsa

| PhosphorImager units (105)b

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA preparation

|

Nuclear

|

Cytoplasmic

|

CAc

|

|||||

| Plasmid | Gage | Unspliced | Spliced | Unspliced | Spliced | Unspliced | Spliced | CUd |

| SNV U3RU5-CTE | 13.0 | 15.0 | 23.0 | 13.0 | 17.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.0 |

| SNV U3RU5-CTE + TAP + NXT1 | 380.0 | 10.0 | 22.0 | 13.0 | 23.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 30.0 |

Transfected 293 cells were analyzed for Gag production and gag RNA expression.

RNA was extracted from transfected 293 cells, treated with DNase, subjected to RNase protection assay with HIV-1 5′ UTR and gapdh probes and quantified by Phosphorlmager analysis. The data are standardized to gapdh RNA level and cotransfected Luc values.

CA, cytoplasmic accumulation. Ratio of RNA in cytoplasm relative to nucleus plus cytoplasm.

CU, cytoplasmic utilization. Ratio of Gag protein to unspliced cytoplasmic gag RNA.

Cell-associated Gag levels in nanograms per mililiter normalized to cotransfected Luc values.

MPMV U3RU5 also supports Gag augmentation by CTE in COS, but not 293 cells

We also evaluated the effect on Gag production upon combination of MPMV U3RU5 and MPMV CTE in HIV-1 gag-pol reporter plasmids (Fig. 1). Comparable to results with SNV U3RU5 reporter plasmid, results of multiple triplicate reporter gene assays in COS cells demonstrated that Gag production from MPMV U3RU5 was augmented five- to sevenfold in response to MPMV CTE (Table 1). For example, Gag production was 10 ± 2 and 57 ± 18 ng/ml from MPMV U3RU5 and MPMV U3RU5-CTE, respectively. Furthermore, MPMV CTE did not augment Gag production in 293 cells (Table 2). Gag production remained similar in the absence or presence of CTE at 10 ± 0.6 and 10 ± 0.9 ng/ml, respectively. The results demonstrate that SNV and MPMV RU5gag reporter transcripts display similar responses to CTE and exhibit augmented Gag production in COS, but not 293 cells. MPMV RU5gagCTE reporter RNA also yielded similar increases in Gag production in response to overexpression of Tap and NXT1 (data not shown).

SNV RU5 and MPMV RU5 do not confer responsiveness to Tap and NXT1

The overexpression strategy was also used to address whether or not SNV and MPMV RU5 confer responsiveness to Tap and NXT1 independently of CTE. In contrast to results with the CTE-containing derivatives, the CTE-lacking plasmids SNV U3RU5 and MPMV U3RU5 exhibit little modulation of Gag production in response to Tap and NXT1. Gag production in a representative of three experiments was 49 ± 10 ng/ml for SNV U3RU5 and 57 ± 11 ng/ml in response to Tap and NXT1, and 34 ± 4 ng/ml for MPMV U3RU5 and 30 ± 0.6 ng/ml in response to Tap and NXT1. These results demonstrated that SNV and MPMV RU5 do not confer responsiveness to Tap and NXT1 and that Tap and NXT1 are not rate-limiting factors for Rev/RRE-independent Gag production by SNV and MPMV RU5. The results also affirm that rescue of Gag augmentation from SNV and MPMV RU5gagCTE RNA by Tap and NXT1 in 293 cells in attributable to interaction with CTE.

Discussion

This study assessed whether or not MPMV CTE functions compatibly with 5′ terminal posttranscriptional control elements in the SNV or MPMV 5′ LTR to synergistically augment Rev/RRE-independent Gag production. The results demonstrate that the combination of MPMV CTE and SNV RU5 or MPMV RU5 on a single HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA produced a synergistic increase in Gag production in monkey COS cells. However, the same combinations did not synergistically increase Gag production in human 293 cells. Transient transfection assays demonstrated that replacement of SNV U3 with the CMV promoter facilitated responsiveness to CTE and indicated that SNV U3 impeded Gag augmentation in 293 cells. These results imply that SNV U3 functions upstream of CTE and may cotranscriptionally recruit an RNP complex to SNV RU5gagCTE RNA in 293 cells that hinders Gag augmentation. RNA analysis eliminated the possibility that SNV U3 recruited an RNP complex that disrupted nuclear export because CTE sustained an equivalent increase in cytoplasmic accumulation of SNV RU5gag RNA in both COS and 293 cells. Instead, the data argue that SNV U3 recruits an RNP complex that disrupts productive cytoplasmic utilization in 293 cells. In Xenopus oocytes, differences in cytoplasmic utilization are speculated to be controlled by variations in recruitment of RNP components to position-dependent exon–exon junctions (Matsumoto et al., 1998). Excision of an intron positioned 5′ of the open reading frame stimulates translational efficiency relative to a 3′ intron. An interesting analogy in another step of posttranscriptional control of gene expression is the promoter-dependent cotranscriptional recruitment of splicing factors to the RNP complex that dictate disparate patterns of alternative splicing of fibronectin RNA (Cramer et al., 1997, 1999).

Notably, previous analysis of CTE has utilized reporter RNAs that absolutely require CTE for nuclear export, which does not facilitate assessment of the effect of CTE on cytoplasmic RNA utilization (Bray et al., 1994; Ernst et al., 1997). In this article, analysis of SNV RU5gagCTE reporter RNA provided a unique tool to evaluate CTE and revealed an unexpected additional property: augmentation of cytoplasmic RNA utilization. CTE increased the overall cytoplasmic accumulation of SNV RU5gag RNA by threefold, produced a minor increase in the absolute level of cytoplasmic RNA, but produced a 7- to 16-fold increase in protein production in COS cells. These results argue that, in addition to augmentation of cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced SNV RU5gag RNA, CTE recruits an RNP complex that imprints the cytoplasmic RU5gag RNA for efficient translation in COS cells.

The overexpression experiments demonstrated that Tap and NXT1 are necessary and sufficient to rescue augmentation of Gag production from SNV RU5gagCTE RNA in 293 cells. Tap and NXT1 in conjunction with CTE produce a significant 30-fold increase in cytoplasmic utilization of the reporter RNA. Recently, Coyle et al. demonstrated that overexpression of Sam68 also enhances the cytoplasmic utilization of CTE-containing HIV-1 gag-pol reporter RNA (Coyle et al., 2003). The mechanisms are unknown by which Tap and NXT1 enhances Gag production from RU5gagCTE RNA or Sam68 enhances Gag production from SVgagpolCTE RNA. We speculate that overexpression of Tap and NXT1 reorganizes the RNP complex to achieve productive association with factors necessary for efficient translation. By contrast, in COS cells a productive RNP complex is constitutively recruited to RU5gagCTE RNA and hypothetical reorganization solicited by overexpression of Tap and NXT1 is not necessary. Recent experiments have identified that Tap interacts with multiple adapter proteins including selected components of the EJC and shuttling SR proteins (Huang et al., 2003; Stutz et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2000). The data argue for competitive interactions with Tap that regulate recruitment of Tap to mRNA (Huang et al., 2003). Future biochemical studies of the mRNP architecture will be important to define the mechanism by which nuclear proteins modulate the utilization of cytoplasmic RNA.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The construction of the SNV U3, SNV U3RU5, SNV U3RU5-RRE, CMV, CMV RU5, and MPMV U3RU5 reporter plasmids has been described previously (Butsch et al., 1999; Dangel et al., 2002; Hull and Boris-Lawrie, 2002). To create derivative CTE-containing reporter plasmids, the MPMV CTE sequence was amplified by PCR from pSHRM-1 (Bryant et al., 1986) (a kind gift of E. Hunter, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL) and ligated into a unique SatlI site in the 3′ UTR.

DNA transfection and reporter protein analysis

Triplicate reporter gene assays were performed on protein from 1 × 105 human 293 or 3 × 105 monkey COS cells transfected with 2 μg of reporter plasmid by a CaPO4 or a Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) protocol, respectively (Hull and Boris-Lawrie, 2002). Overexpression and tethering experiments were performed with 2.5 × 105 293 or 5.0 × 105 COS cells, 5 μg of reporter plasmid, 5 μg of pTap or pRevM10Tap, which is a fusion protein composed of an export deficient Rev protein and wild-type Tap, and 5 μg of pNXT1 or mutant NXT1 (pmNXT1) (N48K, N50K), which abrogates NXT1 binding to Tap (kind gifts of M.-L. Hammarskjöld, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA) (Guzik et al., 2001). The cells were harvested 48 h posttransfection in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), centrifuged at 3000× g for 3 min, and resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40]. HIV Gag levels were quantified by a Gag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Coulter Corp., Miami, FL) and normalized to Luc activity from cotransfected pGL3 (Promega). Luc assays were performed with 10 μl lysate and 100 μl Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega) and quantified in a Lumicount luminometer (Packard, Meriden, CT.). The Student t-test was performed to determine whether the observed differences in Gag production were statistically significant as defined by a p value of ≤0.05.

RNA analysis

RNA protection assays (RPA) were performed with 15 μg of nuclear and 25 μg of cytoplasmic RNA that had been separated by a hypotonic buffer protocol (Hull and Boris-Lawrie, 2002). The RNAs were analyzed with uniformly labeled antisense RNA probes that were prepared by run-off transcription of HIV 5′ UTR and gapdh plasmids as previously described (Butsch et al., 1999).

Acknowledgments

We thank Marie Louise Hammarskjold (University of Virginia) for the gift of pTap, pNXT1, pmNXT1, and pRevM10Tap expression plasmids; David Rekosh (University of Virginia) for the gift of pSVgagpol, pSVgagpolRRE, and pSVgagpolMPMV CTE; and Patrick Green and Tiffiney Roberts for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society, Ohio Division, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R29A146325), and the National Cancer Institute (P30CA16058).

References

- Bachi A, Braun IC, Rodrigues JP, Pante N, Ribbeck K, von Kobbe C, Kutay U, Wilm M, Gorlich D, Carmo-Fonseca M, Izaurralde E. The C-terminal domain of TAP interacts with the nuclear pore complex and promotes export of specific CTE-bearing RNA substrates. RNA. 2000;6:136–158. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200991994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun IC, Rohrbach E, Schmitt C, Izaurralde E. TAP binds to the constitutive transport element (CTE) through a novel RNA-binding motif that is sufficient to promote CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus. EMBO J. 1999;18:1953–1965. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray M, Prasad S, Dubay JW, Hunter E, Jeang KT, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML. A small element from the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus genome makes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression and replication Rev-independent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1256–1260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant ML, Gardner MB, Marx PA, Maul DH, Lerche NW, Osborn KG, Lowenstine LJ, Bodgen A, Arthur LO, Hunter E. Immunodeficiency in rhesus monkeys associated with the original Mason–Pfizer monkey virus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;77:957–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butsch M, Boris-Lawrie K. Destiny of unspliced retroviral RNA: ribosome and/or virion? J Virol. 2002;76:3089–3094. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3089-3094.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butsch M, Hull S, Wang Y, Roberts TM, Boris-Lawrie K. The 5′ RNA terminus of spleen necrosis virus contains a novel posttranscriptional control element that facilitates human immunodeficiency virus Rev/RRE-independent Gag production. J Virol. 1999;73:4847–4855. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4847-4855.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JH, Guzik BW, Bor YC, Jin L, Eisner-Smerage L, Taylor SJ, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML. Sam68 enhances the cytoplasmic utilization of intron-containing RNA and is functionally regulated by the nuclear kinase Sik/BRK. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:92–103. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.92-103.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P, Caceres JF, Cazalla D, Kadener S, Muro AF, Baralle FE, Kornblihtt AR. Coupling of transcription with alternative splicing: RNA pol ll promoters modulate SF2/ASF and 9G8 effects on an exonic splicing enhancer. Mol Cell. 1999;4:251–258. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P, Pesce CG, Baralle FE, Komblihtt AR. Functional association between promoter structure and transcript alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11456–11460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangel AW, Hull S, Roberts TM, Boris-Lawrie K. Nuclear interactions are necessary for translational enhancement by spleen necrosis virus RU5. J Virol. 2002;76:3292–3300. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3292-3300.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostie J, Dreyfuss G. Translation is required to remove Y14 from mRNAs in the cytoplasm. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1060–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst RK, Bray M, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML. A structured retroviral RNA element that mediates nucleocytoplasmic export of intron-containing RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:135–144. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruter P, Tabemero C, von Kobbe C, Schmitt C, Saavedra C, Bachi A, Wilm M, Felber BK, Izaurralde E. TAP, the human homolog of Mex67p, mediates CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus. Mol Cell. 1998;1:649–659. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzik BW, Levesque L, Prasad S, Bor YC, Black BE, Paschal BM, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML. NXT1 (p15) is a crucial cellular cofactor in TAP-dependent export of intron-containing RNA in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2545–2554. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2545-2554.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Gattoni R, Stevenin J, Steitz JA. SR splicing factors serve as adapter proteins for TAP-dependent mRNA Export. Mol Cell. 2003;11:837–843. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull S, Boris-Lawrie K. RU5 of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus 5′ long terminal repeat enhances cytoplasmic expression of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 gag-pol and vonviral reporter RNA. J Virol. 2002;76:10211–10218. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10211-10218.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Bogerd HP, Cullen BR. Analysis of cellular factors that mediate nuclear export of RNAs bearing the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus constitutive transport element. J Virol. 2000;74:5863–5871. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.5863-5871.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Cullen BR. The human Tap protein is a nuclear mRNA export factor that contains novel RNA-binding and nucleocytoplasmic transport sequences. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1126–1139. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.9.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim VN, Kataoka N, Dreyfuss G. Role of the nonsense-mediated decay factor hUpf3 in the splicing-dependent exon-exon junction complex. Science. 2001a;293:1832–1836. doi: 10.1126/science.1062829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim VN, Yong J, Kataoka N, Abel L, Diem MD, Dreyfuss G. The Y14 protein communicates to the cytoplasm the position of exon-exon junctions. EMBO J. 2001b;20:2062–2068. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir H, Gatfield D, Izaurralde E, Moore MJ. The exon-exon junction complex provides a binding platform for factors involved in mRNA export and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. EMBO J. 2001;20:4987–4997. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir H, Izaurralde E, Maquat LE, Moore MJ. The spliceosome deposits multiple proteins 20–24 nucleotides upstream of mRNA exon-exon junctions. EMBO J. 2000a;19:6860–6869. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Hir H, Moore MJ, Maquat LE. Pre-mRNA splicing alters mRNP composition: evidence for stable association of proteins at exon-exon junctions. Genes Dev. 2000b;14:1098–1108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque L, Guzik B, Guan T, Coyle J, Black BE, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML, Paschal BM. RNA export mediated by tap involves NXT1-dependent interactions with the nuclear pore complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44953–44962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo MJ, Reed R. Splicing is required for rapid and efficient mRNA export in metazoans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14937–14942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ML, Zhou Z, Magni K, Christoforides C, Rappsilber J, Mann M, Reed R. Pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA export linked by direct interactions between UAP56 and Aly. Nature. 2001;413:644–647. doi: 10.1038/35098106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykke-Andersen J, Shu MD, Steitz JA. Human Upf proteins target an mRNA for nonsense-mediated decay when bound downstream of a termination codon. Cell. 2000;103:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykke-Andersen J, Shu MD, Steitz JA. Communication of the position of exon-exon junctions to the mRNA surveillance machinery by the protein RNPS1. Science. 2001;293:1836–1839. doi: 10.1126/science.1062786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Wassarman KM, Wolffe AP. Nuclear history of a pre-mRNA determines the translational activity of cytoplasmic mRNA. EMBO J. 1998;17:2107–2121. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TM, Boris-Lawrie K. The 5′ RNA terminus of spleen necrosis virus stimulates translation of nonviral mRNA. J Virol. 2000;74:8111–8118. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8111-8118.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues JP, Rode M, Gatfield D, Blencowe BJ, Carmo-Fonseca M, Izaurralde E. REF proteins mediate the export of spliced and unspliced mRNAs from the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1030–1035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031586198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell T, Kulozik AE, Hentze MW. Integration of splicing, transport and translation to achieve mRNA quality control by the nonsense-mediated decay pathway. Genome Biol Rev. 2002:S1006. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-3-reviews1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutz F, Bachi A, Doerks T, Braun IC, Seraphin B, Wilm M, Bork P, Izaurralde E. REF, an evolutionary conserved family of hnRNP-like proteins, interacts with TAP/Mex67p and participates in mRNA nuclear export. RNA. 2000;6:638–650. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand HL, Coburn GA, Zeng Y, Kang Y, Bogerd HP, Cullen BR. Formation of Tap/NXT1 heterodimers activates Tap-dependent nuclear mRNA export by enhancing recruitment to nuclear pore complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:245–256. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.245-256.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Luo MJ, Straesser K, Katahira J, Hurt E, Reed R. The protein Aly links pre-messenger-RNA splicing to nuclear export in metazoans. Nature. 2000;407:401–405. doi: 10.1038/35030160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin AS, Valentin A, Pavlakis GN, Felber BK. Continuous propagation of RRE(−) and Rev(−)RRE(−) human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones containing a cis-acting element of simian retrovirus type 1 in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Virol. 1994;68:7944–7952. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7944-7952.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]