Abstract

Podophyllotoxin acetate (PA) acts as a radiosensitizer against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in vitro and in vivo. In this study, we examined its potential role as a chemosensitizer in conjunction with the topoisomerase inhibitors etoposide (Eto) and camptothecin (Cpt). The effects of combinations of PA and Eto/Cpt were examined with CompuSyn software in two NSCLC cell lines, A549 and NCI-H1299. Combination index (CI) values indicated synergistic effects of PA and the topoisomerase inhibitors. The intracellular mechanism underlying synergism was further determined using propidium iodide uptake, immunoblotting and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Combination of PA with Eto/Cpt promoted disruption of the dynamics of actin filaments, leading to subsequent enhancement of apoptotic cell death via induction of caspase-3, -8, and -9, accompanied by increased phosphorylation of p38. Conversely, suppression of p38 phosphorylation blocked the apoptotic effect of the drug combinations. Notably, CREB-1, a transcription factor, was constitutively activated in both cell types, and synergistically inhibited upon combination treatment. Our results collectively indicate that PA functions as a chemosensitizer by enhancing apoptosis through activation of the p38/caspase axis and suppression of CREB-1.

Keywords: chemosensitizer, podophyllotoxin acetate, etoposide, camptothecin, p38, apoptosis, CREB-1

Introduction

Cancer is a major cause of human death in modern industrialized countries. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), in particular, is associated with air pollution and smoking, and presents a low 5-year survival rate due to difficulties of diagnosis and limited therapeutic options (1). NSCLC therapy typically involves surgery, radiotherapy, and/or drug treatment. However, drugs and radiation therapy frequently result in therapeutic resistance, the primary obstacle to effective treatment for most cancers (2). Development of combinations of therapeutic drugs forms an essential element of strategies to improve patient survival. The rationale for combined drug therapy is based on the concept that combinations of therapeutic modalities with different mechanisms of action are more effective at eradicating cancer than a single agent, while minimizing toxicity and requiring lower drug doses (3).

PA is a derivative of podophyllotoxin, previously isolated from the natural product library as an anticancer drug candidate and radiosensitizer (4). Podophyllotoxin, one of the lignans isolated from podophyllin, is a type of resin from Podophyllum. These lignans are secondary metabolites consisting of two phenylpropane units produced via the shikimic acid pathway. Podophyllotoxin exhibits the aryl-tetralin structure of cyclolignans, a carbocycle between the two phenylpropane units comprising two single carbon-carbon bonds through the side-chains, one of which is located between the β-β′ positions. The lignan is historically reported to exert antiviral and immunosuppressive effects as well as activity against venereal warts (5). Additionally, podophyllotoxin mediates antitumor activity via reversible binding of tubulin and disruption of tubulin polymerization. This destroys the dynamic equilibrium of microtubules and triggers disruption of mitotic-spindle microtubule formation, inducing cell cycle arrest. Several investigators have synthesized various derivatives, with the aim of improving the antitumor effects of podophyllotoxin. Studies to date led to the development of three representative semi-synthetic epipodophyllotoxin derivatives, etoposide (Eto), teniposide and etopophos (6). Interestingly, the main anticancer target of Eto among these drugs is not tubulin polymerization but topoisomerase (TOP) II in the DNA TOP family, since etoposide does not prevent microtubule formation due to the presence of a bulky glucoside moiety in its chemical structure. DNA Tops are ubiquitous enzymes controlling the topological state of DNA during replication that exist in two forms, type I and II. Type I breaks a single strand of double-stranded DNA, while type II cleaves both strands, resulting in inhibition of religation of the nucleic acid-drug-enzyme complex (5,6). Camptothecin (Cpt), an inhibitor of TOP I initially isolated from the bark of Camptotheca acuminate in 1966 is a cytotoxic quinoline alkaloid (7,8) that possesses a planar pentacyclic ring structure. The A-D rings are required for maintaining activity and the ‘E-ring lactone interacts with the binding site in TOP I. Therefore, hydrolysis or removal of lactone disrupts Cpt activity (9). Induction of single- and double-stranded DNA breaks by TOP inhibitors leads to effective cell death or apoptosis in rapidly growing cell populations, such as cancer cells. Accordingly, TOP inhibitors and derivatives have been widely employed to treat a range of cancers, either as sole agents or combinations (10).

In this study, we examined whether PA promotes cell death in combination with TOP inhibitors and assessed its potential as a chemosensitizer to enhance cancer treatment efficiency. Our results collectively demonstrated a synergistic effect between PA and TOP inhibitors leading to enhanced apoptosis in NSCLC cell lines, which was attributable to activation of p38 and caspases, and inactivation of CREB-1.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and chemical reagents

NCI-H1299 and A549 human NSCLC cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). SB203580, U0126, JNK inhibitor II, Eto, Cpt, z-VAD-fmk and CBP-CREB interaction inhibitor (CREB inhibitor) were obtained from EMD Millipore Corp. (Billerica, MA, USA). PA was acquired from MicroSource Discovery Systems, Inc. (Gaylordsville, CT, USA).

MTT assay

NCI-H1299 and A549 cells (4×103 cells/well in 96-well plates) were seeded and treated with different concentrations of PA and Eto/Cpt. After 72 h, 50 μl of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution (2 mg/ml) was added to each well, and plates incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Formazan crystals formed by living cells were dissolved in 200 μl/well dimethyl sulf-oxide (DMSO), and the absorbance of individual wells read at 545 nm using a Multiskan EX ELISA reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of PA on HCI-H1299 and A549 cells was calculated from a concentration-response analysis performed using Softmax Pro software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Drug combination analysis

CompuSyn software (Ver. 1.0) and its manual were downloaded from http://www.combosyn.com to calculate the synergistic effects of combinations of PA and Eto/Cpt. Cell survival percentage data were acquired from the MTT assay and inserted into CompuSyn software. The effects of the PA and Eto/Cpt combinations were analyzed, and the combination index (CI) for each treatment calculated as described in the product manual.

Microtubule assembly assay

The microtubule assembly assay was performed as described previously by our group (11). Briefly, NCI-H1299 and A549 cells were seeded (1×106 cells per 100-mm culture dish) and treated with 7.5 or 15 nM PA and 0.5 μM Eto/10 nM Cpt, respectively, for 24 h. Cells were lysed and samples collected via centrifugation. The supernatant fractions contained soluble αβ tubulin dimers while the pellets contained polymerized microtubules. Each fraction was subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Immunocytochemical staining

NCI-H1299 and A549 cells (1×104) were seeded in chamber slides and treated with 7.5 or 15 nM PA and 0.5 μM Eto/10 nM Cpt, respectively, for 24 h. Treated cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and subsequently stained with an anti-α-tubulin antibody and DAPI. Images of stained cells were acquired with a 710 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Propidium iodide uptake assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 1×105 cells and incubated with or without 7.5 or 15 nM PA and 0.5 μM Eto/10 nM Cpt. After 72 h, cells were harvested via trypsinization, washed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in 300 μl of 5 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The apoptotic fraction was evaluated using a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblots were performed as described previously (12). Membranes were probed with antibodies against caspase-3, -8, and -9, phospho-p38, and p38 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA, USA). An anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) was used a control for equal loading. Relative band densities of targets, determined densitometrically and normalized to that of β-actin or p38, were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, USA).

ELISA detection assay of p38 enzyme activity

To detect the phosphorylation level of p38, the p38 MAPK alpha (pT180/pY182) + total p38 MAPK alpha ELISA kit was purchased from Abcam® (Cambridge, UK). NCI-H1299 and A549 cells were seeded onto a 100-mm plate (1×106) and treated with control, Eto, Cpt, PA only or combinations of PA/Eto or PA/Cpt for 24 h. After discarding media, cells were rinsed with PBS and dissolved with 1X cell lysate buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors provided in the kit. ELISA was performed as described by the manufacturer. Supernatant fractions of each sample were collected via centrifugation, followed by sequential incubation with the relevant primary/secondary antibodies. Samples were treated with TMB One-Step substrate reagent for 30 min and Stop solution for detection of OD values at 450 nm in a Multiskan EX ELISA reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each OD value was calculated as a phosphor-p38/p38 activity ratio and graphically illustrated.

Electrophoretic mobility shift (EMSA) assay

NCI-H1299 and A549 cells were harvested and nuclei isolated as described previously (13). The EMSA system was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA), and all procedures performed as described by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), and the significance of differences between experimental groups determined using the Student's t-test. Data were considered significant at p-values <0.05. Individual p-values in figures are denoted by asterisks (*p<0.05, **p<0.01,***p<0.001). The numbers above each point or bar in the graphs represent the means of three independent experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations (SD).

Results

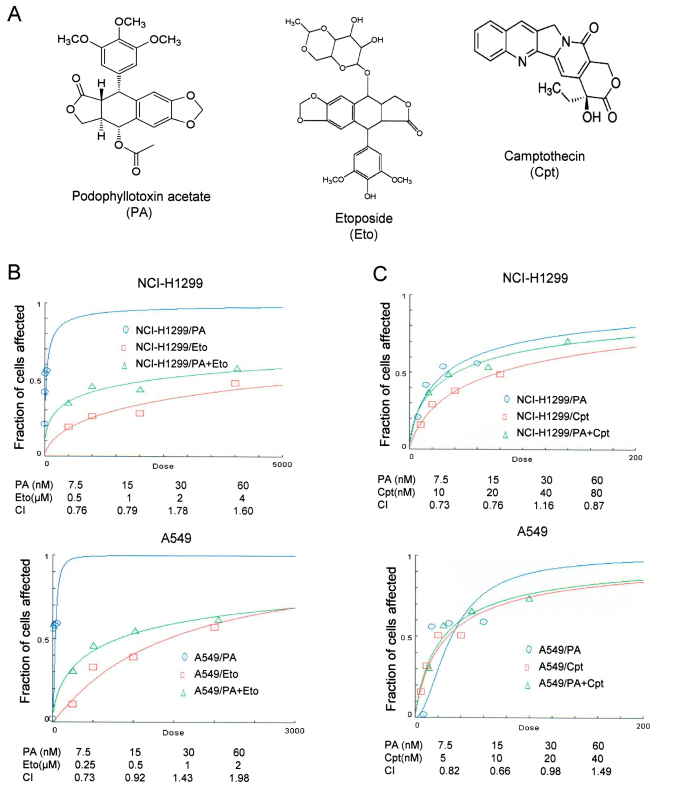

The combination of PA and TOP inhibitors has a synergistic effect

PA was initially screened from a natural product library as an anticancer drug candidate (Fig. 1A). The IC50 values of PA in NCI-H1299 and A549 cells were determined as 7.6 and 16.1 nM after 72 h of treatment, respectively. Effects of combined treatment with PA and TOP inhibitors (Eto and Cpt) on NSCLC cells were assessed with CompuSyn software (Fig. 1B and C). NCI-H1299 and A549 cell lines were treated with 7.5, 15, 30 and 60 nM PA and 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 μM or 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2 μM Eto, respectively, and the synergistic effects of PA/Eto examined. Treatment of NCI-H1299 and A549 cells with 7.5, 15, 30 and 60 nM PA and 10, 20, 40 and 80 μM or 5, 10, 20 and 40 nM Cpt was performed to detect synergistic effects. Specifically, 7.5 nM PA + 0.5 μM Eto and 15 nM PA + 1 μM Eto in NCI-H1299 cells and 7.5 nM PA + 0.25 μM Eto and 15 nM PA + 0.5 μM Eto in A549 cells were determined as combinations displaying effective synergistic activity (Fig. 1B). All combinations of PA+Cpt, except 30 nM PA + 40 nM Cpt in NCI-H1299 cells and 60 nM PA + 40 nM Cpt in A549 cells, exerted synergistic effects (Fig. 1C). Our results clearly indicate that PA and TOP inhibitors exert synergistic effects in vitro. Accordingly, the intracellular machineries involved in synergism were subsequently examined.

Figure 1.

Combined treatment with PA and TOP inhibitors (Eto and Cpt) synergistically induces apoptosis of NCI-H1299 and A549 cells. (A) Chemical structures of PA (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?sid=93087), Eto (ref. 5) and Cpt (ref. 10). (B and C) Calculation of the combination index (CI) of PA and Eto/Cpt. The MTT assay was performed to determine the fraction of cells affected on the y-axis. NCI-H1299 cells were co-treated with 0, 7.5, 15, 30 or 60 nM PA and 0, 0.5, 1, 2 or 4 μM Eto or 0, 10, 20, 40 or 80 nM Cpt. A549 cells treated with 0, 7.5, 15, 30 or 60 nM PA and 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1 or 2 μM Eto or 0, 5, 10, 20 or 40 nM Cpt.

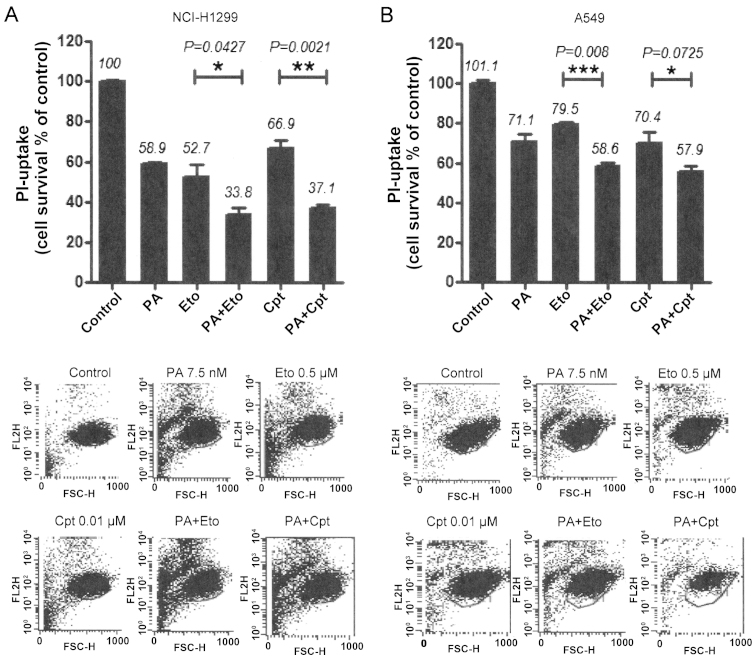

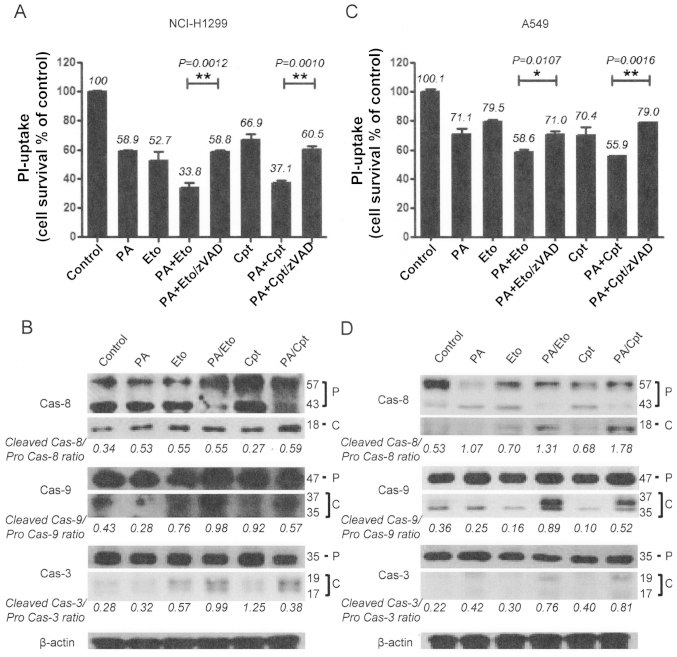

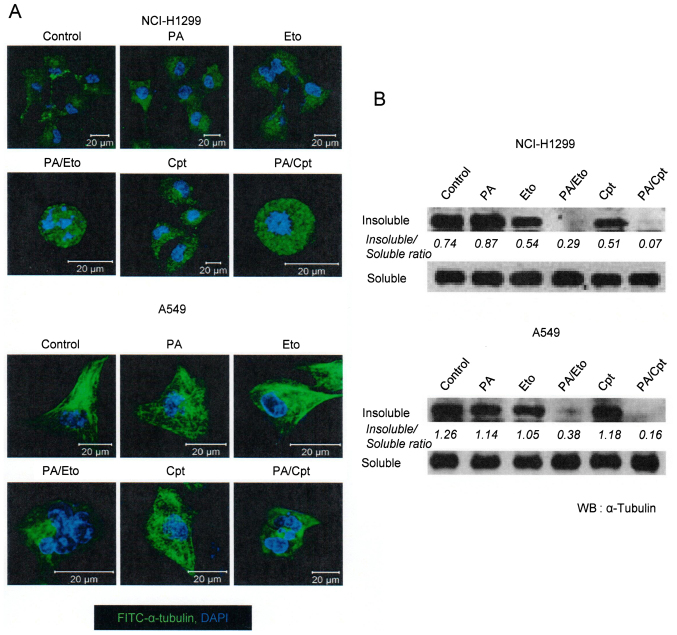

PA and TOP inhibitor combinations enhance microtubule polymerization and apoptotic cell death

In view of the ability of PA to disrupt tubulin polymerization (11), we examined whether the combination of PA and TOP inhibitors exerts similar effects. Microtubule assembly assays and immunocytochemical staining using an anti-α-tubulin antibody revealed that combination treatment led to decreased microtubule polymerization and disruption of microtubule organization in NCI-H1299 and A549 cells in a synergistic manner (Fig. 2). Immunocytochemical staining disclosed rounded morphology of NCI-H1299 cells and fragmented nuclei of A549 cells (Fig. 2A, upper panel). Based on results showing that the drug combinations enhance the microtubule damage effects of PA, studies on other cell death machinery were performed. In subsequent experiments, apoptotic cell death induction by the combinations was assessed with PI uptake (11). In NCI-H1299 cells, a combination of PA and Eto (7.5 nM PA + 0.5 μM Eto) enhanced apoptosis by ~25 and 21%, compared with PA (7.5 nM) only and Eto (0.5 μM) only treatment, while a combination of PA and Cpt (7.5 nM PA + 10 nM Cpt) increased cell death by ~21 and 30%, respectively (Fig. 4A). In A549 cells, PA and Eto (15 nM PA + 0.5 μM Eto) synergistically enhanced apoptosis by ~14 and 21%, compared with PA (15 nM) only and Eto (0.5 μM) only, while PA and Cpt (15 nM PA + 10 nM Cpt) increased cell death by ~15 and 24%, respectively, relative to treatment with the individual drugs (Fig. 4B). Treatment with the pan-caspase inhibitor, z-VAD-fmk, blocked the enhancement of cell death induced by the drug combinations in both cell lines (Fig. 4A and C). We confirmed that the combination treatments promote activation of apoptosis via immunoblot assays for caspase-3, -8, or -9 (Fig. 4B and D). These results imply that PA acts as a chemosensitizer that enhances the cytotoxicity of TOP inhibitors by promoting apoptosis.

Figure 2.

Combination treatment with PA and TOP inhibitors (Eto and Cpt) enhances cell death. (A and B) PI uptake assay for determination of cell death induced with combination treatments. NCI-H1299 (A) and A549 (B) cells were treated with PA, Eto, Cpt or both for 72 h. Representative data from experiments performed in triplicate are shown in each right panel.

Figure 4.

Combined treatment with PA and TOP inhibitors (Eto and Cpt) enhances apoptotic cell death. (A and C) PI uptake assay for determination of apoptosis. Pre-treatment with 20 μM zVAD-fmk, a pan-caspase inhibitor was performed for 1 h before treatment with the PA/Eto or PA/Cpt combination for NCI-H1299 (A) and A549 (C) cells for 72 h. Representative data from experiments performed in triplicate are shown in each right panel. (B and D) Immunoblot analysis for detection of caspase-3, -8, and -9 activation of NCI-H1299 (B) and A549 (D) cells for 72 h. Cas indicates caspase, P is pro-form caspase, and C is cleaved form caspase. Immunoblot images and ratios are representative data from experiments performed in triplicate.

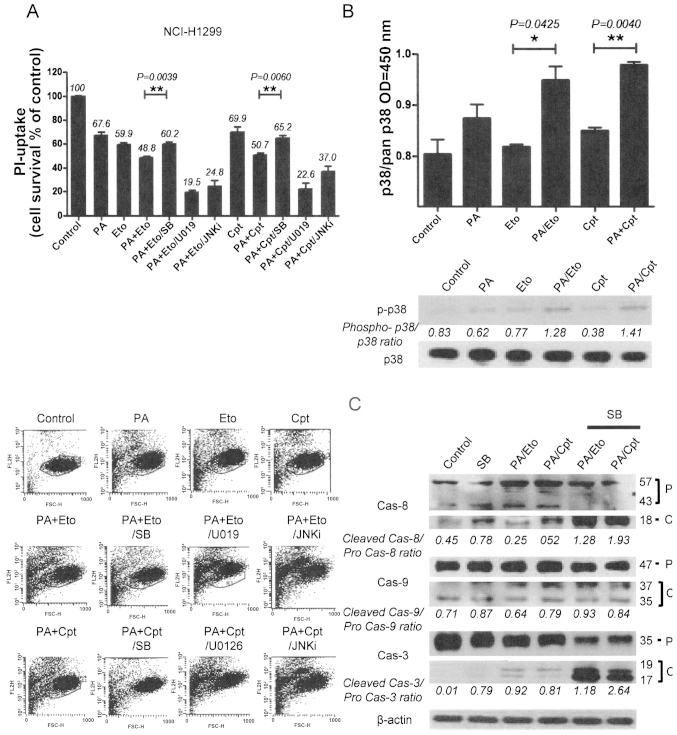

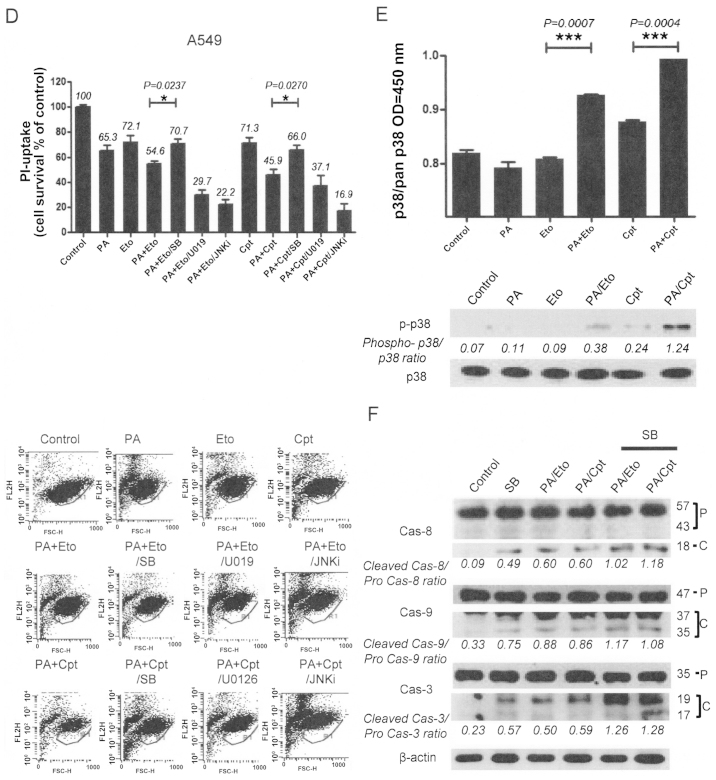

Modulation of MAPKs is involved in the chemosensitizing effect of PA

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying chemo-sensitization by PA, we initially examined the activities of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, including p38, ERK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), following treatment with the drug combinations. Pre-treatment of combined treatment cells with chemical inhibitors (SB203580, U0126, JNK inhibitor II) of each kinase revealed that only p38 inhibition by SB203580 blocked cell death, indicating that p38 kinase is specifically involved in the chemosensitization effect of PA. In contrast, pre-treatment with U0126 and JNK inhibitor II enhanced cell death induced by the combination (Fig. 5A and D). Increased activity and phosphorylation of p38 were also detected with activity (upper panel) and immunoblot assays (lower panel) in the combination treatment groups (Fig. 5B and E). Moreover, inhibition of p38 blocked caspase activation by the drug combinations in both NCI-H1299 and A549 cells, as shown in Fig. 5C and F. Our findings suggest that the chemosensitization effect of PA on TOP inhibitors is derived from enhancement of apoptosis via p38 activation.

Figure 5.

Apoptotic cell death induced by the combination of PA and TOP inhibitors (Eto and Cpt) is mediated via modulation of the MAPK pathway. (A and D) PI uptake assay for determination of apoptosis with combinations of PA, TOP inhibitors, and MAPK inhibitors. NCI-H1299 (A) and A549 (D) cells were pre-treated with 10 μM SB203580 (SB), 10 μM U0126 (U0126), and 10 μM JNK inhibitor (JNKi) for 1 h before treatment with the PA/Eto or PA/Cpt combination for 72 h. Representative data from experiments performed in triplicate are shown in each right panel. (B and E) p38 enzyme activity assay (upper panels) and phospho-p38 immunoblot analyses (lower panels) in NCI-H1299 (B) and A549 (E) cells for 24 h. (C and F) Immunoblot analyses for detection of caspase-3, -8, and -9 activation in NCI-H1299 (C) and A549 (F) cells pre-treated with SB203580 followed by a combination of PA/TOP inhibitors for 72 h. Cas indicates caspase, P is pro-form caspase, and C is cleaved form caspase.

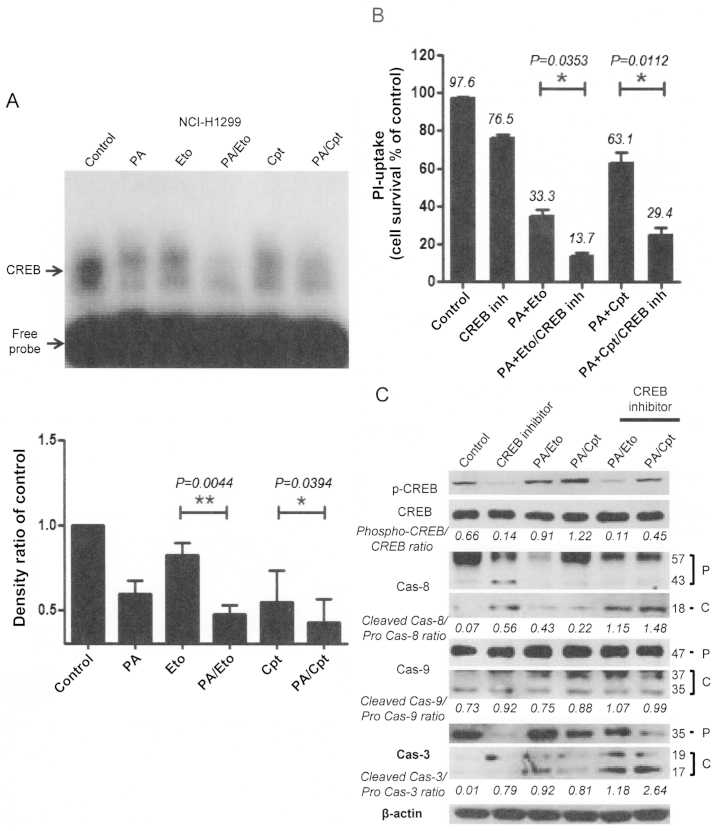

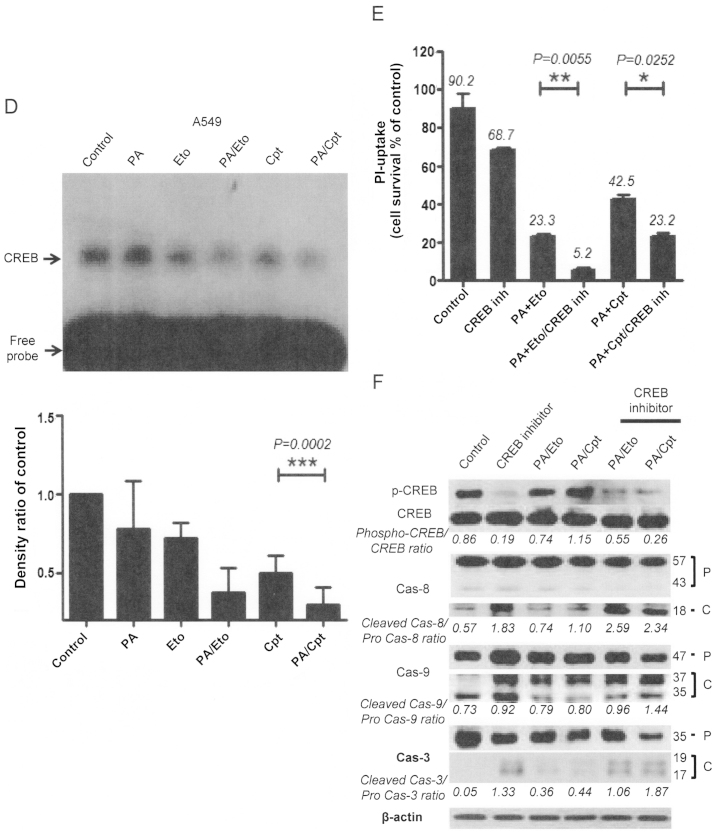

Modulation of CREB-1 is involved in the chemosensitizing effect of PA

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying the chemosensitization activity of PA, we examined several transcriptional factors, in view of the finding that transcriptional factors, such as NF-κB, are activated downstream of various stress signals (14). CREB-1 was constitutively activated in both NCI-H1299 and A549 cells, which was attenuated upon treatment with PA, Eto, or Cpt only. Interestingly, combinations of PA/TOP inhibitors exerted synergistic suppressive effects on activation of CREB-1 (Fig. 6A and D). Treatment with CREB inhibitors enhanced cell death (Fig. 6B and E) and apoptotic pathway activation in cells treated with the PA/TOP inhibitor combinations (Fig. 6C and F). Based on these findings, we suggest that activation of CREB-1 is an essential step for NSCLC cell survival and PA exerts its chemosensitizing effect through inhibition of CREB-1.

Figure 6.

Apoptotic cell death induced by combined treatment with PA and TOP inhibitors (Eto and Cpt) is mediated via modulation of CREB-1 activity. (A and D) EMSA assay for detection of CREB-1 activity following combined treatment of NCI-H1299 (A) and A549 (D) cells with PA and TOP inhibitors. Representative EMSA films from experiments performed in triplicate are shown in each left panel, and analyses of band densities in each right panel. (B and E) PI uptake assay for determination of apoptosis in NCI-H1299 (B) and A549 (E) cells treated with a combination of PA, TOP inhibitors and 10 μM CBP-CREB interaction inhibitors (CREB inh) for 72 h. Representative PI uptake assay data from experiments performed in triplicate are shown in each right panel. (C and F) Immunoblot analyses for detection of activated caspases-3, -8, and -9 in NCI-H1299 (C) and A549 (F) cells treated with combinations of PA/TOP inhibitors and CREB inhibitors for 72 h. Cas indicates caspase, P is pro-form caspase, and C is cleaved form caspase.

Discussion

Improving chemotherapy and minimizing side-effects may entail modulation of different facets of cancer-specific processes involving chemoresistance. The mechanisms of chemoresistance in cancer are classified into intrinsic (cells are resistant before treatment) or acquired (resistance develops during treatment). Significant mechanisms of chemoresistance include overexpression of drug efflux pumps, increased activity of DNA repair mechanisms, altered drug target enzymes, and overexpression of enzymes involved in drug detoxification and elimination (15). Since almost all anticancer reagents induce elimination of cancer cells via apoptosis, the chemoresistance mechanism is focused on modulation of the apoptosis signal and molecules, for example, mutation or deletion of tumor suppressor genes, such as p53, and overexpression of Bcl-2 or IAP family proteins (16,17). Therefore, development of new anticancer drugs or therapeutic strategies that induce activation of apoptosis may present a key approach to overcoming chemoresistance (18).

Data from this study demonstrated chemosensitization activity of PA in combination with TOP inhibitors against NSCLC cell lines, leading to enhanced apoptotic cell death and attenuation of transcription factors involved in cell survival. Topoisomerase I inhibitors, such as topotecan and irinotecan, are usually components of combination chemotherapy against NSCLC (19–21). Eto and Cpt have been identified as powerful and dynamic cytostatic anticancer reagents under both experimental and clinical conditions. These chemicals target a group of microtubules, coincident with our present results (Fig. 3), and act as apoptosis inducers operating via distinct mechanisms. Therefore, treatment with combinations of these agents should theoretically enhance the final therapeutic outcomes (19). The activities of Eto and Cpt as apoptosis inducers were confirmed in our experiments (Fig. 4), whereby two (intrinsic and extrinsic) major apoptotic pathways were activated. The intrinsic pathway is induced by external stress and leads to changes in mitochondrial permeability and activation of caspase-9. The extrinsic pathway mainly begins with death receptor/ligand binding and proceeds through caspase-8 activation. Caspases-8 and -9 in extrinsic and intrinsic pathways are starting ‘initiator’ caspases, and both pathways activate caspase-3, a common ‘executioner’ caspase (22). Inhibition of caspase activation prevented apoptosis in both cell types and blocked synergistic cell death (Fig. 4A and C). We further showed that increased cell death induced by the combination of PA and TOP inhibitors is accompanied by enhanced phosphorylation of p38, which has been shown to evoke cell death secondary to DNA damage and membrane oxidative damage (23,24). Previous reports have shown that disruption of tubulin dynamics leads to activation of p38, inducing apoptosis (11). Coincident with these findings, combination treatment with PA and TOP inhibitors promoted phosphorylation and consequent activation of p38 resulting in increased apoptosis (Fig. 5). Suppression of p38 with the specific inhibitor, SB203580, attenuated caspase activation and apoptosis increase induced by the combination of PA and TOP inhibitors. In contrast, prevention of ERK and JNK activity with U0126 and JNK inhibitor II, respectively, did not block enhancement of apoptosis in either NCI-H1299 or A549 cell line. Based on these findings, we propose that p38 lies downstream of tubulin damage and is responsible for caspase activation and induction of apoptosis. Additionally, the radiosensitizer effect of PA was shown to be related to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) in our previous study (11), but the chemosensitizer effect of PA with TOP inhibitors was not established (data not shown). Other studies have also shown that p38 is a stress response molecule involved in apoptotic cell death induced by numerous chemotherapeutic agents and natural products, including cyclophosphamide (CTX) commonly used for breast cancer, anthocyanins for human colon cancer cells and oxaliplatin for human colorectal cancer cells (25–27). The increased chemosensitivity to CDDP induced by Met inactivation is attributable to p38 MAPK activation (28). Interestingly, the combination of PA and TOP inhibitors reduced phosphorylation of CREB-1, a 43-kDa basic/leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor. CREB-1 is found in most tissues and shown to be overexpressed in several cancer tissues, including leukemic blast cells of acute myeloid leukemia patients and lung cancer, compared to normal tissues (29–32). CREB can form both homo and heterodimeric complexes. CREB binds to the octanucleotide cAMP response element (CRE), TGANNTCA, as a homodimer and to other members of the CREB/ATF transcriptional factor superfamily as a heterodimer (33,34). CREB becomes transcriptionally activated after phosphorylation at serine 133, which induces activity by promoting interactions with the 256-kDa coactivator CREB-binding protein (CBP) (35). Following its activation, the transcription factor is reported to perform various physiological functions, including integration of various stimuli, such as IR, in a p53-dependent manner (34–36), and promote pro-survival signaling important in cancer development and progression (37,38). We detected phosphorylated and activated CREB-1 in both NCI-H1299 and A549 cells (Fig. 6). Sole treatment with PA or TOP inhibitor attenuated endogenous activation of CREB-1. Combined treatments with PA/TOP inhibitors further enhanced suppression of CREB-1 phosphorylation and activation. Our results imply that CREB-1 facilitates cell survival in both cell types, and thus potentially presents a major target of the PA/TOP inhibitor combination.

Figure 3.

Combined treatment with PA and TOP inhibitors enhances PA-induced inhibition of intracellular microtubule polymerization. Control represents mock-treated control. PA, Eto, and Cpt indicate each reagent only-treated sample. PA/Eto and PA/Cpt represent samples treated with a combination of PA and Eto or PA and Cpt. NCI-H1299 and A549 cells were treated with 7.5 and 15 nM PA, respectively. Both cell lines were treated with Eto (0.5 μM) or Cpt (10 nM). (A) Immunocytochemical staining for α-tubulin in NCI-H1299 and A549 cells treated with PA, Eto, Cpt or a combination of the drugs for 24 h. Nuclei are stained blue while α-tubulin is stained green. (B) Immunoblot analyses of α-tubulin in insoluble and soluble fractions of NCI-H1299 and A549 cells treated with PA, Eto, Cpt or a combination for 24 or 48 h.

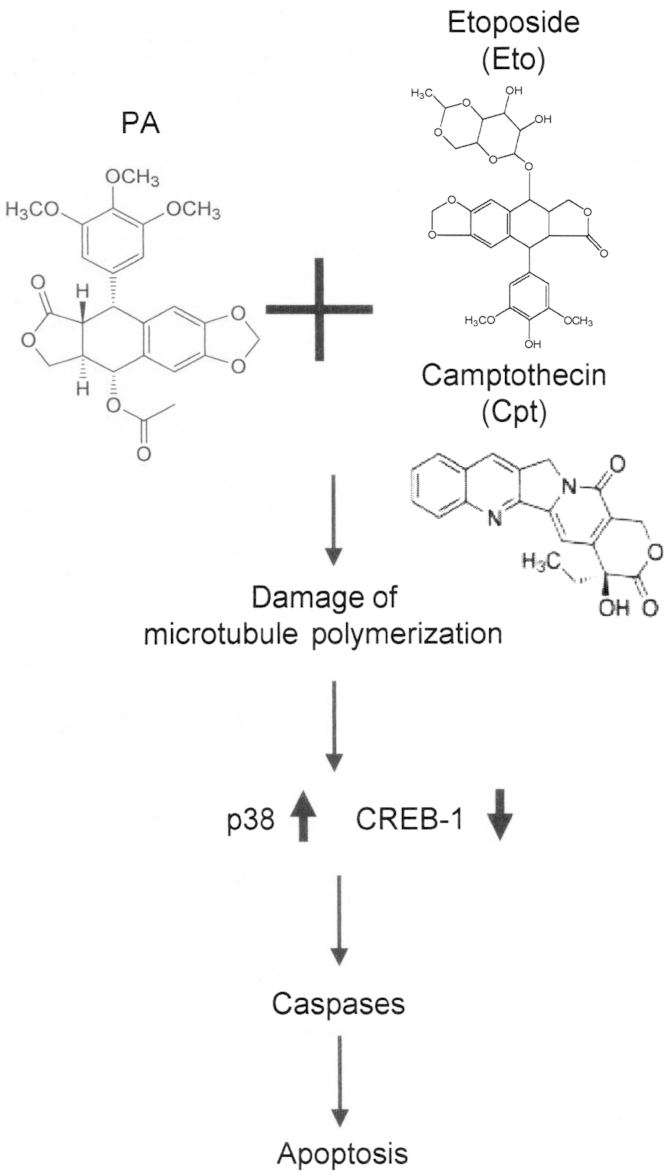

We did not determine whether PA protects normal tissue from chemotherapy-induced side-effects or whether modulation of p38 and CREB-1 mediates whole-cell death in response to PA and TOP inhibitor combinations in this study. Nonetheless, our current results suggest a novel role for PA as a chemosensitizer that enhances apoptotic death of NCI-H1299 and A549 NSCLC cells through promotion of tubulin degradation, activation of the p38/caspase pathway and suppression of CREB-1 activation (Fig. 7). Our findings provide new insights supporting the utility of podophyllotoxin derivatives as chemosensitizers and induction of apoptosis via p38/CREB-1/caspase activation and suppression of CREB-1 as a useful strategy for the development of new therapeutic agents.

Figure 7.

Schematic depiction of the signaling pathway underlying PA activity as a chemosensitizer for TOP inhibitors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Nuclear Research and Development Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MEST) (2012M2A2A7010422) and the Basic Science Research Program through the NRF (NRF-2014R1A1A2054985).

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitsudomi T, Suda K, Yatabe Y. Surgery for NSCLC in the era of personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:235–244. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ismael GF, Rosa DD, Mano MS, Awada A. Novel cytotoxic drugs: Old challenges, new solutions. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi JY, Cho HJ, Hwang SG, Kim WJ, Kim JI, Um HD, Park JK. Podophyllotoxin acetate enhances γ-ionizing radiation-induced apoptotic cell death by stimulating the ROS/p38/caspase pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;70:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordaliza M, García PA, del Corral JM, Castro MA, Gómez-Zurita MA. Podophyllotoxin: Distribution, sources, applications and new cytotoxic derivatives. Toxicon. 2004;44:441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerram M, Jiang Z-Z, Zhang L-Y. Podophyllotoxin, a medicinal agent of plant origin: Past, present and future. Chin J Nat Med. 2012;10:161–169. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1009.2012.00161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wall ME, Wani MC, Cooke CE, Palmer KH, McPhail AT, Sim GA. Plant antitumor agents. I. The isolation and structure of camptothecin, a novel alkaloidal leukemia and tumor nhibitor from Camptotheca acuminata. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:3888–3890. doi: 10.1021/ja00968a057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsiang Y-H, Hertzberg R, Hecht S, Liu LF. Camptothecin induces protein-linked DNA breaks via mammalian DNA topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14873–14878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabr A, Kuin A, Aalders M, El-Gawly H, Smets LA. Cellular pharmacokinetics and cytotoxicity of camptothecin and topotecan at normal and acidic pH. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4811–4816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venditto VJ, Simanek EE. Cancer therapies utilizing the camptothecins: A review of the in vivo literature. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:307–349. doi: 10.1021/mp900243b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi JY, Hong WG, Cho JH, Kim EM, Kim J, Jung CH, Hwang SG, Um HD, Park JK. Podophyllotoxin acetate triggers anticancer effects against non-small cell lung cancer cells by promoting cell death via cell cycle arrest, ER stress and autophagy. Int J Oncol. 2015;47:1257–1265. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JK, Jung HY, Park SH, Kang SY, Yi MR, Um HD, Hong SH. Combination of PTEN and gamma-ionizing radiation enhances cell death and G(2)/M arrest through regulation of AKT activity and p21 induction in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1552–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JK, Park SH, So K, Bae IH, Yoo YD, Um HD. ICAM-3 enhances the migratory and invasive potential of human non-small cell lung cancer cells by inducing MMP-2 and MMP-9 via Akt and CREB. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:181–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piva R, Belardo G, Santoro MG. NF-kappaB: A stress-regulated switch for cell survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:478–486. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shabbits JA, Hu Y, Mayer LD. Tumor chemosensitization strategies based on apoptosis manipulations. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:805–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed JC. Regulation of apoptosis by bcl-2 family proteins and its role in cancer and chemoresistance. Curr Opin Oncol. 1995;7:541–546. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199511000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaCasse EC, Baird S, Korneluk RG, MacKenzie AE. The inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) and their emerging role in cancer. Oncogene. 1998;17:3247–3259. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turrini E, Ferruzzi L, Fimognari C. Natural compounds to overcome cancer chemoresistance: Toxicological and clinical issues. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10:1677–1690. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2014.972933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudolf E, Cervinka M. Topoisomerases and tubulin inhibitors: A promising combination for cancer treatment. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2003;3:421–429. doi: 10.2174/1568011033482242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houghton PJ, Cheshire PJ, Hallman JD, II, Lutz L, Friedman HS, Danks MK, Houghton JA. Efficacy of topoisomerase I inhibitors, topotecan and irinotecan, administered at low dose levels in protracted schedules to mice bearing xenografts of human tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;36:393–403. doi: 10.1007/BF00686188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunn PA, Jr, Kelly K. New chemotherapeutic agents prolong survival and improve quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer: A review of the literature and future directions. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1087–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elmore S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawenda BD, Kelly KM, Ladas EJ, Sagar SM, Vickers A, Blumberg JB. Should supplemental antioxidant administration be avoided during chemotherapy and radiation therapy? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:773–783. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Laethem A, Nys K, Van Kelst S, Claerhout S, Ichijo H, Vandenheede JR, Garmyn M, Agostinis P. Apoptosis signal regulating kinase-1 connects reactive oxygen species to p38 MAPK-induced mitochondrial apoptosis in UVB-irradiated human keratinocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1361–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pang H, Cai L, Yang Y, Chen X, Sui G, Zhao C. Knockdown of osteopontin chemosensitizes MDA-MB-231 cells to cyclophosphamide by enhancing apoptosis through activating p38 MAPK pathway. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2011;26:165–173. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2010.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin DY, Lee WS, Lu JN, Kang MH, Ryu CH, Kim GY, Kang HS, Shin SC, Choi YH. Induction of apoptosis in human colon cancer HCT-116 cells by anthocyanins through suppression of Akt and activation of p38-MAPK. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:1499–1504. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiu SJ, Chao JI, Lee YJ, Hsu TS. Regulation of gamma-H2AX and securin contribute to apoptosis by oxaliplatin via a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. Toxicol Lett. 2008;179:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lou X, Zhou Q, Yin Y, Zhou C, Shen Y. Inhibition of the met receptor tyrosine kinase signaling enhances the chemosensitivity of glioma cell lines to CDDP through activation of p38 MAPK pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1126–1136. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crans HN, Sakamoto KM. Transcription factors and translocations in lymphoid and myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2001;15:313–331. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pigazzi M, Ricotti E, Germano G, Faggian D, Aricò M, Basso G. cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) over-expression CREB has been described as critical for leukemia progression. Haematologica. 2007;92:1435–1437. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shankar DB, Cheng JC, Kinjo K, Federman N, Moore TB, Gill A, Rao NP, Landaw EM, Sakamoto KM. The role of CREB as a proto-oncogene in hematopoiesis and in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo H-S, Liu DD, Bekele BN, Kim MK, Pisters K, Lippman SM, Wistuba II, Koo JS. Cyclic AMP response element-binding protein overexpression: A feature associated with negative prognosis in never smokers with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6065–6073. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. CREB: A stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821–861. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayr BM, Canettieri G, Montminy MR. Distinct effects of cAMP and mitogenic signals on CREB-binding protein recruitment impart specificity to target gene activation via CREB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10936–10941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191152098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amorino GP, Hamilton VM, Valerie K, Dent P, Lammering G, Schmidt-Ullrich RK. Epidermal growth factor receptor dependence of radiation-induced transcription factor activation in human breast carcinoma cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2233–2244. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsumoto K, Yamamoto T, Kurachi H, Nishio Y, Takeda T, Homma H, Morishige K, Miyake A, Murata Y. Human chorionic gonadotropin-alpha gene is transcriptionally activated by epidermal growth factor through cAMP response element in trophoblast cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7800–7806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swarthout JT, Tyson DR, Jefcoat SC, Jr, Partridge NC. Induction of transcriptional activity of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein by parathyroid hormone and epidermal growth factor in osteoblastic cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1401–1407. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.8.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]