SUMMARY

We describe a comprehensive genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC). Using this dataset, we expand the catalogue of known ACC driver genes to include PRKAR1A, RPL22, TERF2, CCNE1, and NF1. Genome wide DNA copy number analysis revealed frequent occurrence of massive DNA loss followed by whole genome doubling (WGD) which was associated with aggressive clinical course, suggesting WGD is a hallmark of disease progression. Corroborating this hypothesis were increased TERT expression, decreased telomere length, and activation of cell cycle programs. Integrated subtype analysis identified three ACC subtypes with distinct clinical outcome and molecular alterations which could be captured by a 68 CpG probe DNA methylation signature, proposing a strategy for clinical stratification of patients based on molecular markers.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Zheng et al. perform comprehensive genomic characterization of 91 cases of adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC). This analysis expands the list of driver genes in ACC, reveals whole genome doubling as a hallmark of ACC progression, and identifies three ACC subtypes with distinct clinical outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) is a rare endocrine malignancy with an annual incidence of 0.7–2 per million (Bilimoria et al., 2008; Else et al., 2014a). Current staging schemes such as by the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ENSAT) broadly divides ACCs into 4 stages (Fassnacht et al., 2009). While stage I and II tumors are organ-confined and potentially curable by complete resection, advanced stage tumors are invasive (stage III) and/or metastatic (stage IV), with a dismal 5 year survival of 6–13% for stage IV patients (Else et al., 2014b; Fassnacht et al., 2009; Fassnacht et al., 2013). Histologic grading of ACC based on proliferation (Giordano, 2011; Weiss et al., 1989) refines treatment decisions for specific patient subgroups, but is not universally accepted (Miller et al., 2010). Chemotherapy, radiotherapy and the adrenolytic agent mitotane are the current standard therapeutic modalities for unresectable or metastatic ACC, but all are palliative (Else et al., 2014a). Our understanding of ACC pathogenesis is incomplete and additional therapeutic avenues are needed.

Molecular studies have nominated several genes as potential drivers involved in sporadic adrenocortical tumorigenesis, including insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), β-catenin (CTNNB1), and TP53 (Giordano et al., 2003; Tissier et al., 2005). β-catenin gain-of-function mutations are evident in approximately 25% of both benign and malignant sporadic adrenocortical neoplasms (Tissier et al., 2005). Recent genomic profiling efforts of ACC have identified candidate driver genes such as ZNRF3 and TERT, and identified molecular subgroups with variable clinical outcomes (Assie et al., 2014; Pinto et al., 2015). Germline variants of these genes are also associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann, Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Coli and Li-Fraumeni syndromes, in which adrenocortical neoplasia occur.

Comprehensive and integrated genomic characterization of ACC may identify additional oncogenic alterations, provide a framework for further research, and guide development of therapies. As one of the rare cancer projects of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), we collected the clinical and pathological features, genomic alterations, DNA methylation profiles, and RNA and proteomic signatures of 91 cases of ACC. The comprehensive nature of the dataset combined with the many easy access routes to the individual and aggregated profiles will serve as a point of reference for many future ACC and comparative cancer studies. Here, we report this resource and an integrated analysis of the data.

RESULTS

Patient cohort, clinical annotation and analytical approach

We analyzed 91 histologically confirmed tumors and matched blood or normal tissue from a global cohort collected from 6 countries including 84 usual type, 4 oncocytic, 2 sarcomatoid and 1 myxoid variant. Median age at diagnosis was 49 years, and female:male ratio was 1.8. While 51 (56%) involved the left gland and 40 (44%) the right gland, more tumors in the left gland were diagnosed in males than females (72% vs 47%; p value=0.03, Fisher’s exact test). The majority of tumors (57%) were functional; hypercortisolism was the most common endocrinopathy. Resected tumors spanned all stages (stage I, n=9; II, n=43; III, n=19; IV, n=17; 3 unavailable). Median overall survival was 78 months with 5-year survival of 59%. Locally invasive and metastatic tumors (grade III plus IV) had dramatically reduced median overall survival (18 months) with 5-year survival of 22%. Clinicopathologic data are summarized in Table S1. Patient stage at diagnosis and cortisol hypersecretion were predictive for both overall survival and disease free survival (Else et al., 2014b), but age was only associated with overall survival. Gender had no clear association with disease stage or clinical outcome (Table S1).

We generated a comprehensive molecular dataset of the 91 tumors, as follows: whole exome sequence (n=90), mRNA sequence (n=78), miRNA sequence (n=79), DNA copy number via SNP arrays (n=89), DNA methylation via DNA methylation arrays (n=79) and targeted proteome from reverse phase protein array (RPPA; n=45) (Table S1).

Our analytical approach consisted of four main parts. We began by identifying somatic single nucleotide variants, gene fusions, and copy number alterations. Given the significant copy number alterations observed, we performed an extended bioinformatic analysis that revealed the role of genome doubling and telomere maintenance in ACC. Using the various molecular datasets, we derived molecular classifications of ACC and integrated a three class solution with the somatic genomic landscape. We placed ACC in the broader context of cancer by performing several pan-cancer analyses. Finally, we quantified adrenal differentiation and tumoral hormone production across the entire cohort to correlate the genomic results with clinical parameters. All unprocessed data used in the analysis can be accessed through the TCGA portals.

Exome and RNA-sequencing nominate ACC driver events

Somatic single nucleotide variants (SSNVs) and small indels were detected using five independent mutation callers and variants called by at least three callers or independently validated by RNA sequencing were included (Figure S1A and S1B). This approach yielded a total of 8,814 high-confidence mutations (6,664 nonsynonymous and 2,150 synonymous; 3,427 of these were found in two tumors with ultramutator phenotype. Deep coverage re-sequencing (1,500×) achieved a validation rate of 95% (Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Table S1). The median somatic mutation density was 0.9 per Mb, similar to pancreatic adenocarcinoma but twice more than that of another endocrine tumor, papillary thyroid cancer (Figure S1C). Similar to other cancers, ACC demonstrated a marked heterogeneity in mutation density (range: 0.2 to 14.0 mutations/Mb, excluding the two ultramutators). Mutation density was correlated with numerous clinicopathological parameters including overall survival, time to recurrence, necrosis, stage, Weiss score, and mitotic count (Figure S1D). Interestingly, these associations remained when restricting to organ-confined stage I and II diseases.

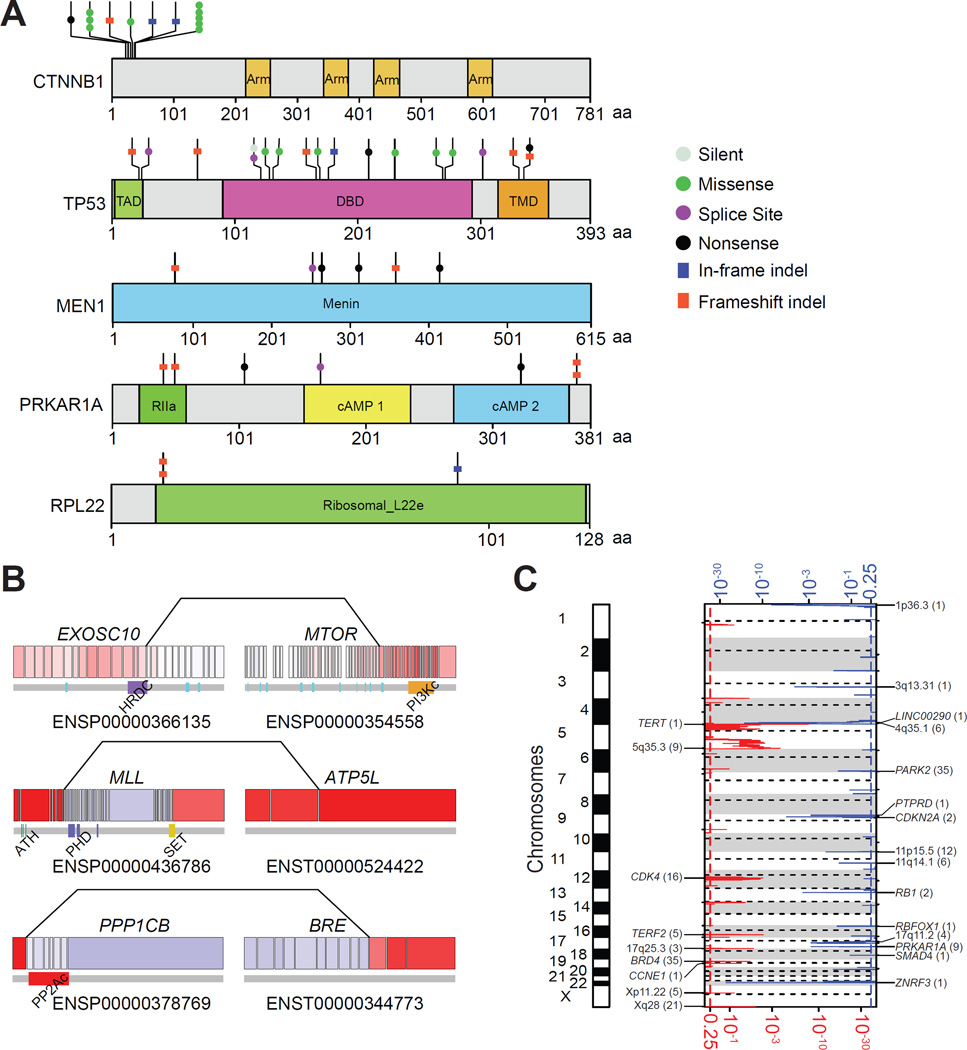

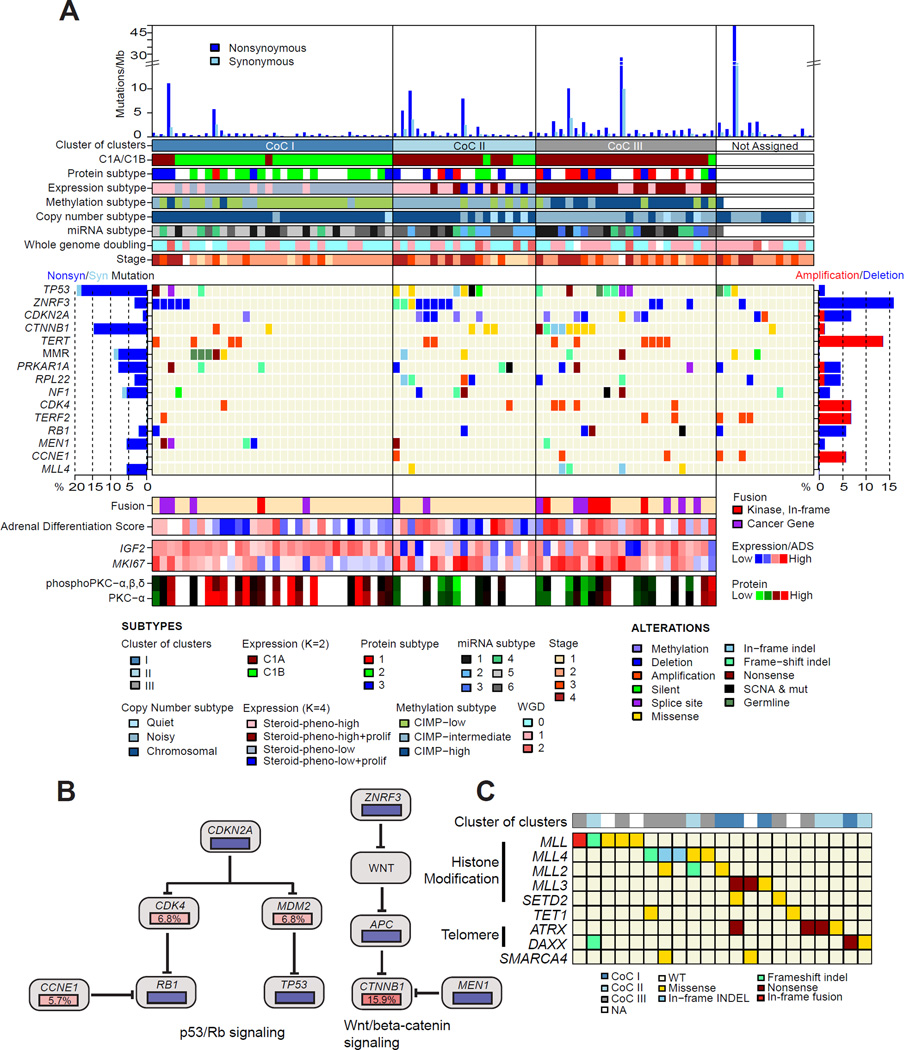

We used MutSigCV (Lawrence et al., 2013) to identify five significantly mutated genes (SMGs): TP53, CTNNB1, MEN1, PRKAR1A and RPL22. The mutation frequencies ranged from 3.3% to 17.8% of the cohort (Figure 1A and Figure S1E). Mutations of TP53 and CTNNB1 in ACC are well recognized (Tissier et al., 2005). As expected, missense mutations in CTNNB1 were confined to exon 3 (Figure 1A). Six (7%) tumors harbored inactivating mutations in MEN1, consistent with prior studies implicating MEN1 in ACC (Assie et al., 2014). While our cohort is the largest to be sequenced to date, a much larger number of samples is needed to identify all candidate cancer genes (Lawrence et al., 2014). To overcome the limitation of sample size, we compared the mutated genes with the Cancer Gene Census (Futreal et al., 2004). This approach identified two cancer genes mutated in more than 5% of the cohort, NF1 and MLL4, in addition to those nominated by MutSigCV.

Figure 1. Mutational driver genes in ACC.

(A) Protein domain structure of the five significantly mutated genes with somatic mutations aligned. Functional domains and mutation types are indicated in different colors and shapes as shown in the legend. Arm, Armadillo domain; TAD, transcription-activation domain; DBD, DNA binding domain; TMD, tetramerisation domain; RIIa, regulatory subunit of type II PKA R-subunit. (B) Sporadic gene fusions that involve cancer genes. All exons are represented, with red and blue indicating high and low expression respectively. Lines linking two exons indicate the fusion positions. Protein domains are related to the exons below the gene diagram. HRDC, helicase and RNase D C-terminal; PI3Kc, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, catalytic domain; ATH, AT-hook motif; PHD, plant homology domain; SET, Su(var)3–9, enhancer-of-zeste, trithorax; PP2Ac, protein phosphatase 2A homologues, catalytic domain. (C) Focal recurrent amplifications and deletions in ACCs with the number of genes spanned by the peak in parentheses. Red and blue indicate amplification and deletion, respectively. The x-axis at the bottom and top of the figure represents significance of amplification/deletion per q-value. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

In our cohort, 7 (8%) cases harbored inactivating mutations in the protein kinase cAMP-dependent regulatory type I alpha gene (PRKAR1A) (Figure 1A). A homozygous deletion was found in three additional cases. While inactivating germline PRKAR1A mutations cause Carney complex and benign primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) (Kirschner et al., 2000), malignant transformation has been reported in the adrenals of patients with this rare condition (Anselmo et al., 2012), and sporadic loss-of-function mutations in PRKAR1A have been found in adrenocortical adenomas and rare carcinomas (Bertherat et al., 2003). Interestingly, DNA sequencing of sporadic adrenocortical adenomas recently revealed a recurrent activating L206R mutation in the catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) (PRKACA) (Beuschlein et al., 2014; Goh et al., 2014). This mutation results in constitutive PKA activity by disrupting the interaction between PRKACA and the regulatory subunits of PKA including PRKAR1A (Calebiro et al., 2014; Goh et al., 2014). While we found no PRKACA mutations in our cohort, we observed decreased PRKAR1A expression and increased MEK and BRAF protein expression (Figure S1F and S1G) in mutant cases, suggesting a potential role for inhibition of the RAF-MEK-ERK cascade in treatment of some ACCs.

We observed two frameshift mutations in ribosomal protein L22 (RPL22) and confirmed them by RNA sequencing (Figure 1A). We detected a third in-frame deletion mutation in a sample with heterozygous loss of RPL22, and homozygous loss of RPL22 in three ACCs. These findings suggest a role for somatic alteration of RPL22 in 7% of ACC, which has previously been related to MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation (Zhang and Lu, 2009).

Using two complementary analytical methods to detect fusion transcripts in mRNA-seq data (McPherson et al., 2011; Torres-Garcia et al., 2014), we identified 156 singleton but no recurrent gene fusion events in 48 of 78 (62%) tumors (range: 1–16) (Figure S1H and Table S1). Gene fusions occur at much lower frequencies than mutations and copy number variants (Yoshihara et al., 2015), and a larger cohort is needed to determine the frequency of fusions reported here. However, we did identify private in–frame fusions involving known cancer genes (Figure 1B). A highly expressed EXOSC10-MTOR fusion retained the mTOR catalytic domain and resulted in elevated levels of total and phosphorylated mTOR protein in this tumor (Figure S1I). The fusion point of a MLL-ATP5L fusion fell within the MLL breakpoint cluster region associated with acute myeloid leukemia (Krivtsov and Armstrong, 2007). Both fusion cases lacked mutations in SMGs. A fusion involving the gene BRE, reported to promote tumor cell growth and adrenal neoplasia (Chan et al., 2005; Miao et al., 2001), was identified in one tumor. While more data are required to ascertain their roles in ACC, these private fusions may represent functional transcripts.

Whole genome doubling is a common event in ACC

We assessed somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) and loss of heterozygosity in 89 tumors. Using GISTIC2 (Mermel et al., 2011), we identified recurrent focal amplifications of TERT (5p15.33), TERF2 (16q22.1), CDK4 (12q14.1) and CCNE1 (19q12) and deletions of RB1 (13q14.2), CDKN2A (9p21.2) and ZNRF3 (22q12.1) (q ≤ 0.01; Figure 1C and Table S1). A focal deletion peak around 4q34.3–4q35.1 centered on a long noncoding RNA LINC00290, which has been reported as a deletion target in pediatric ACCs and other cancers (Letouze et al., 2012; Zack et al., 2013). ZNRF3 homozygous deletions appeared in 16% (n=14) of tumors assayed; by including non-silent mutations, 19.3% of ACCs harbored alterations in this gene. TERT and TERF2, two telomere maintenance related genes (Blasco, 2005), were focally amplified in 15% and 7% of cases, respectively. TERT promoter hotspot mutations have been recently discovered in human cancers (Huang et al., 2013). We resequenced the TERT promoter region of all 91 tumors. In agreement with a recent study (Liu et al., 2014), we identified four cases with the C228T mutation, but no C250T mutations.

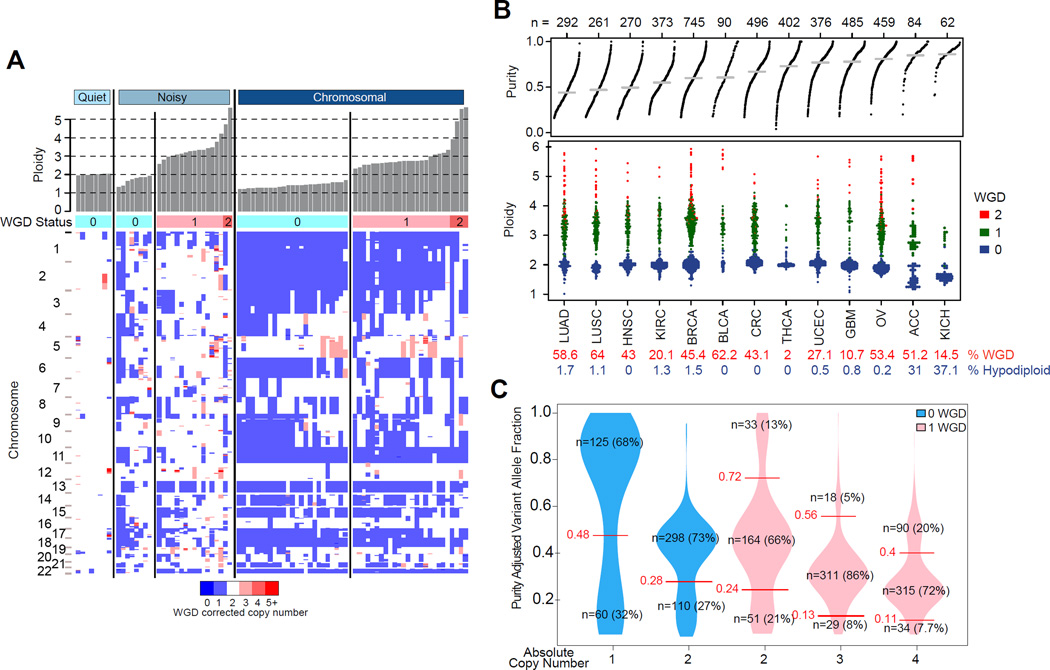

Arm-level copy number changes were frequent in ACC (Figure 2A and S2A). Clustering of 89 tumors based on their arm-level alterations produced three groups with striking differences: chromosomal (n=54; 61%); noisy (n=27; 30%); and quiet (n=8; 9%) (Figure S2A). The chromosomal group showed the highest frequency of whole chromosome arm gains and losses. The noisy group was characterized by a significantly higher number of chromosomal breaks as well as frequent loss of 1p with 1q intact. Tumors in the quiet group had few large copy number alterations. Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated a significant decrease in survival in the noisy group relative to the chromosomal and quiet subtypes, suggesting that this copy number phenotype is characteristic of aggressive disease (Figure S2A). To validate these subtypes, we analyzed an independent data set of ACC tumors (n=119) profiled on different versions of the Illumina BeadArray platform (Assie et al., 2014). Based on the chromosome 1p/1q pattern, the noisy group and its survival association were recovered in this independent cohort (Figure S2B), suggesting that the group distinctions are robust. We did not observe copy number quiet ACC in the independent cohort.

Figure 2. Landscape of DNA copy number alteration in ACC.

(A) Three major copy number patterns in ACC. Unsupervised clustering divided the cohort (n=89) into quiet, chromosomal and noisy subtypes. (B) Pan-cancer purity and ploidy including ACC. Sample sizes are indicated on top. Average tumor purity is plotted as a grey line for each cancer type. The percentages of whole genome doubling and hypodiploidy (ploidy ≤1.6) are listed in red and blue, respectively. LUAD - lung adenocarcinoma; LUSC – lung squamous; HNSC – head and neck; KIRC – clear cell renal cell; BRCA – breast; BLCA – bladder; CRC – colorectal; THCA – thyroid papillary; UCEC – endometrial; GBM – glioblastoma; OV – ovarian; KICH – kidney chromophobe. (C) Purity adjusted variant allele fraction in genome doubled and undoubled tumors. Only tumors with high purity (≥0.8) and mutation density less than 5 were included. Cutoffs labeled in the figure are recognized as turning points in the density distributions of variant allele fractions. See also Figure S2.

We next determined tumor purity, ploidy and whole genome doubling (WGD) by integrating allelic copy number profiles and DNA mutation data using the previously validated ABSOLUTE algorithm (Carter et al., 2012). ACC samples were pure relative to other tumor types (tumor purity 0.82±0.15; Figure 2B). Consistently fractions of tumor infiltrated stromal cells estimated from gene expression signatures (Yoshihara et al., 2013) were low relative to a panel of 14 other cancer types (Figure S2C). Immune scores were lower in cortisol-secreting ACCs (p value=0.015), consistent with the suppression of T cell activity by glucocorticoids (Palacios and Sugawara, 1982). We found that hypodiploid karyotypes (ploidy ≤ 1.6) occurred more frequently in ACC than in eleven other tumor types (31% vs. 1%; Figure 2B), a frequency that was only matched by chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. WGD occurred in 68% of the noisy subtype, 51% of the chromosomal subtype, and none of the diploid quiet subtype cases. We inferred the temporal order of somatic mutations for genes implicated in ACC based on variant allele fractions (VAF) and genotype (Figure 2C and S2D). Mutations in TP53 (n=7), MEN1 (n=3), RPL22 (n=2), and ZNRF3 (n=2) were predicted to have occurred prior to WGD. Only 4/9 CTNNB1 mutations were predicted to be pre-doubling, while three were post-doubling and the remaining two showed further reduced VAFs suggestive of subclonality. PRKAR1A mutations split evenly as having occurred before WGD, after WGD or being subclonal.

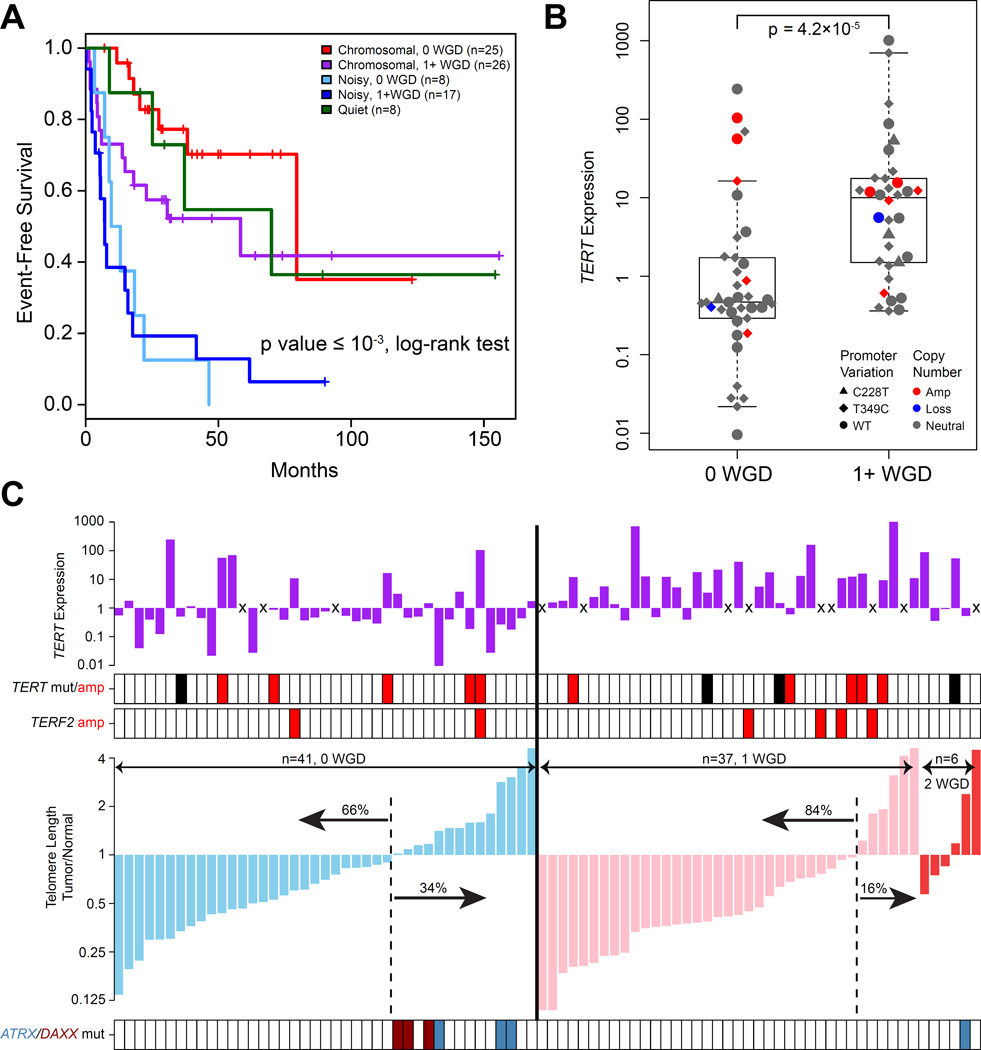

We observed that loss of heterozygosity (LOH) patterns were nearly identical between hypodiploid and hyperdiploid cases in the chromosomal group (rho=0.96, p value<10−5) (Figure S3A and S3B). We hypothesized that the undoubled chromosomal ACCs were precursors to the chromosomal ACC that underwent whole genome doubling. This model is corroborated by the difference in outcome and absolute copy number (Figure 3A, S3C and S3D). We did not find a survival difference between non-WGD and WGD noisy samples suggesting that additional factors may contribute to disease course or that we were underpowered to detect a statistically significant signal. Mutation density further corroborated the WGD hypothesis as the higher mutation frequency in WGD cases was eliminated after normalization by ploidy (Figure S3E).

Figure 3. Comparison of WGD and non-WGD ACCs.

(A) Event free survival of copy number subtypes and whole genome doubling groups. P value represents the statistical significance of event free survival differences between the five groups. (B) TERT expression in genome undoubled and doubled tumors. Boxplot shows median and interquartile range of TERT expressions, with whiskers extending to extreme values within 1.5 interquartile ranges from the upper and lower quartiles. Each dot corresponds to a tumor. (C) Telomere length was estimated using off-target exome sequencing data corrected for tumor purity and ploidy. Top panel shows TERT expression with “x” representing missing values. TERT promoter C228T mutation (black), amplification (red) and TERF2 amplification (red) are noted in the second panel. The bottom panel represents ATRX and DAXX mutations in light blue and dark red, respectively. See also Figure S3.

We employed gene set enrichment analysis using gene expression data to uncover differences between WGD and non-WGD tumors. We identified significantly enhanced pathways in WGD tumors including telomere regulation, cell cycle regulation and DNA replication repair (Figure S3F and S3G). The identification of cell cycle regulation was verified by an independent algorithm, Evaluation of Dependency DifferentialitY (Jung and Kim, 2014), which detected enrichment of the PARKIN pathway (Figure S3F) including PARK2, a recently reported master regulator of G1/S cyclins (Gong et al., 2014).

Amongst the telomere regulation pathway, TERT expression was significantly higher in the WGD group (FDR=0.05) (Figure 3B). Given the role of telomerase in maintaining telomere length (Blasco, 2005), we used spill over sequence generated by exome sequencing to infer telomere length of tumors and normal samples (Ding et al., 2014). Most tumors (73%) exhibited shorter telomeres than their matched normal samples (Figure 3C). WGD cases harbored shorter telomeres than non-WGD cases (Figure S3H). The association between WGD and TERT expression may suggest that increased TERT was required as a compensatory mechanism for telomere maintenance. Alternatively, TERT may have been non-functional with eroding telomeres as a consequence. This confirms previous observations that the majority of ACCs show telomerase activity, particularly in those with relatively short telomeres, while only a minority uses alternative telomere lengthening (ALT) as a telomere maintenance mechanism (Else et al., 2008). Telomere crisis is thought to drive tetraploidization (Davoli and de Lange, 2012) and may be directly associated with WGD events in these tumors. Similar to pediatric ACC and other cancers (Heaphy et al., 2011; Pinto et al., 2015), mutations in ATRX and DAXX (n=7) were associated with longer telomeres (p value= 5.4×10−5, Fisher’s exact test; Figure 3C). We did not find significant associations between telomere length and TERT promoter mutations or TERT amplification. Most cancers express TERT in the context of decreased telomere length (Maser and DePinho, 2002), suggesting that increased TERT maintains telomere homeostasis to a level that is sufficient for cancer cells to survive crisis. TERF2 was amplified in 7% of the cohort but similarly did not correlate with telomere length. TERF2 serves as an anchor protein of the shelterin complex which binds to telomeric DNA, but its direct involvement in telomere elongation has not been determined (Blasco, 2005). It has been documented that TERF2 might have telomere-independent functions (Stewart and Weinberg, 2006), raising interesting hypotheses about its role in adrenal tumorigenesis.

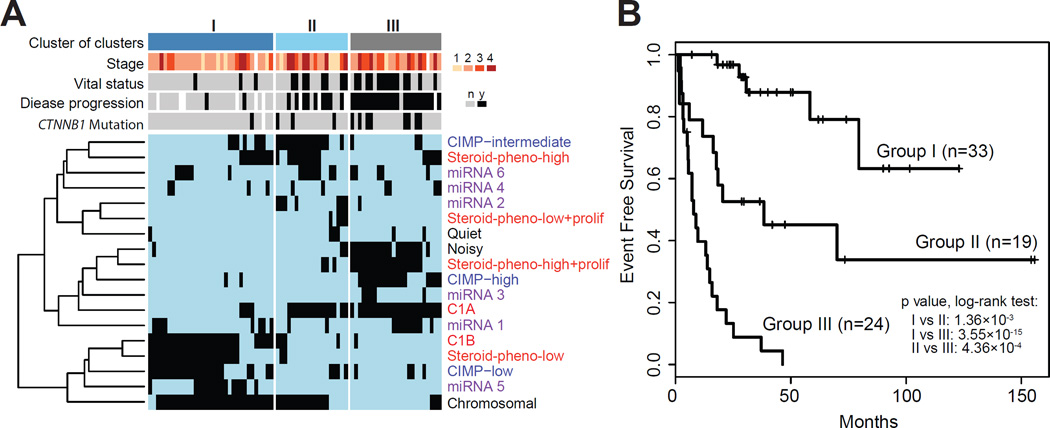

Molecular classes of adrenocortical carcinoma are captured by DNA Methylation signatures

To derive a robust molecular classification, we used unsupervised clustering to analyze the genomic and transcriptomic datasets (Figure S4 and Figure S2A). This approach yielded four mRNA expression groups (Figure S4A–B), six microRNA expression groups (Figure S4C–K), three DNA methylation groups (Figure S4L), three copy number groups (Figure S2A) and three protein expression groups (Figure S4M–N). Except for microRNA based clustering, the individual cluster analyses all resulted in classifications with significant differences in outcome. These subtypes are summarized in Table S2 and characteristics of each molecular classification are described in detail in the Supplemental Information. We integrated the ACC subsets identified across the DNA copy number, DNA methylation, mRNA expression and miRNA expression platforms through a Cluster of Cluster (CoC) analysis (Figure 4). Combined, the molecular classifications converged into three CoC subtypes (Figure 4A and S4O). Transcriptome clustering in a non-overlapping ACC sample set has previously identified an aggressive C1A subtype and an indolent C1B subtype (de Reynies et al., 2009; Giordano et al., 2009). A comparison between CoC and C1A/C1B showed that the majority of CoC I were classified as C1B, while most CoC II and CoC III were predicted as C1A (Figure 4A). Pan-cancer pathway enrichment analyses showed significant up-regulation of genes in immune-mediated pathways in CoC I tumors and mitotic pathways in CoC III tumors (Figure S4P). We compared the clinical outcome of the three CoC clusters. Disease progression rates of the three CoCs were 7%, 56%, and 96%, respectively. Survival analysis showed a dismal median event-free survival of eight months for CoC III (Figure 4B) while median event-free survival time was not reached in CoC I. CoC II was more heterogeneous in outcome with an event-free survival of 38 months. Stage III/IV tumors represented 25%, 47%, and 52% of CoC I, II, III, respectively, and stage I/II cases in CoC III showed MKI67 values in accordance with their grade classification (Figure 5A).

Figure 4. Cluster of clusters.

(A) Cluster of clusters (CoCs) from four platforms (DNA copy number, black; mRNA expression, red; DNA methylation, blue; miRNA expression, purple) divided the cohort into 3 groups. Presence or absence of membership for each sample is represented by black or light blue ticks, respectively. Sample parameters are aligned on top of the heatmap. White tick indicates data not available. (B) Event free survival of the 3 CoC groups. Pairwise log-rank test p values are shown. See also Figure S4 and Table S2.

Figure 5. Genomic landscape of ACC.

(A) The ensemble of mutations, copy number alterations, methylations, subtypes and clinicopathological parameters. (B) Aggregated alterations of the p53/Rb pathway and the Wnt pathways. Activating and deactivating alterations are indicated in red and blue, respectively. (C) Mutations in epigenetic regulatory genes. See also Figure S5 and Table S3.

While the CoC analysis showed that molecular data can determine outcome with high significance, implementing four parallel profiling platforms poses a clinical challenge. The four expression subtypes and three methylation subtypes rendered discriminative representations of each CoC group (Figure 4A), offering plausible routes for clinical implementation. Given the potential of the methylation platform to provide accurate data on formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tumor samples (de Ruijter et al., 2015; Thirlwell et al., 2010), we derived a methylation signature consisting of 68 probes that were included in both Illumina Human Methylation 450K and 27K arrays and tested its performance. This signature robustly classified our cohort into three ACC survival groups with 92.4% accuracy (Table S2). Classification of 51 methylation profiles from an independent cohort (Assie et al., 2014) accurately validated the prognostic power of the methylation signature (Figure S4Q).

Integrated genomic landscape of ACC

We generated a genomic landscape of ACC by further integrating multimodal mutational and epigenetic data with the CoC three class solution (Figure 5A). In addition to DNA copy number and mutations, we assessed epigenetic silencing and germline mutations of 177 manually selected genes (Table S3). We found 9 germline mutations, including two TP53R337H in two Brazilian patients, two MSH6, one MSH2 and one NF1R1534X mutations. The MSH6 and MSH2 mutations support recent observations that ACC is a Lynch syndrome-associated cancer (Raymond et al., 2013). The two TP53R337H mutated patients were younger than the rest of the cohort (23 and 30; median age of cohort: 49). We also found a single TINF2S245Y variant that is associated with dyskeratosis congenita. The likely benign variant APCE1317Q was observed in two cases (Rozek et al., 2006).

Collectively the genes altered most frequently by somatic mutations, DNA copy number alterations and epigenetic silencing were TP53 (21%), ZNRF3 (19%), CDKN2A (15%), CTNNB1 (16%), TERT (14%) and PRKAR1A (11%). The majority of gene alterations were either mutation or copy number change, except CDKN2A, which was targeted by both deletion and epigenetic silencing through promoter DNA methylation. Alterations of ZNRF3, CTNNB1, APC and MEN1 resulted in modification of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in 41% of cases (Figure 5B). Wnt pathway activity, as measured by expression of canonical Wnt target genes, was increased in ACC with Wnt-pathway alterations relative to Wnt wild-type samples (Figure S5A). Somatic alterations in TP53, CDKN2A, RB1, CDK4 and CCNE1 emphasize the importance of the p53 apoptosis/Rb1 cell cycle pathway, and were altered in 44.9% of the cases (Figure 5B). Finally, histone modification genes (MLL, MLL2, and MLL4) and chromatin remodeling genes (ATRX and DAXX) were collectively altered in 22% of cases, suggesting a role for epigenetic deregulation in ACC tumorigenesis (Figure 5C). Unsupervised HotNet2 analysis of protein-protein interaction network identified four significant subnetworks containing at least four genes (Figure S5B, p value<0.0001) (Leiserson et al., 2015). In addition to p53, Rb-cell cycle and Wnt-alteration subnetworks, HotNet2 showed a PKA network affecting 16 samples in total.

Combining somatic mutations, copy number alterations, and epigenetic modification, we found at least one alteration of potential driver genes in 69% of tumors (Figure 5A). The majority of CoC I tumors did not harbor a driver alteration that we could detect. We also examined the expression of IGF2 and an established proliferation marker MKI67. MKI67 expression was lower in CoC I tumors, consistent with the indolent phenotype of this subtype. IGF2 expression was unanimously high independent of ACC classification. Expression of IGF2 was relatively high in 67 of 78 (86%) ACCs (cutoff log2(RSEM)=14 determined by expression distribution), with no association to either promoter DNA methylation or genome rearrangement.

Based on existing clinical trials and FDA-approved drugs for cancers, we found 51 potentially actionable alterations, including both mutations and copy number alterations, in 22 ACCs using precision heuristics for interpreting the actionable landscape (PHIAL) (Van Allen et al., 2014), from cyclin-dependent kinases to DNA repair protein poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) (Figure S5C and Table S3).

Pan-Cancer Analyses provide context to ACC

Pan-cancer analysis of genomic data has provided insights on a wide range of cancer related questions. In an attempt to understand the driving mechanisms of ACC, we grouped our cohort on the basis of recurrent cancer-driving alterations using OncoSign (Ciriello et al., 2013). Our results broadly recapitulated the C class (OSC1–3, copy number driven) and M class (OSC 4–5, mutation driven) that have been described as a general trend across cancers (Ciriello et al., 2013) (Figure S6A).

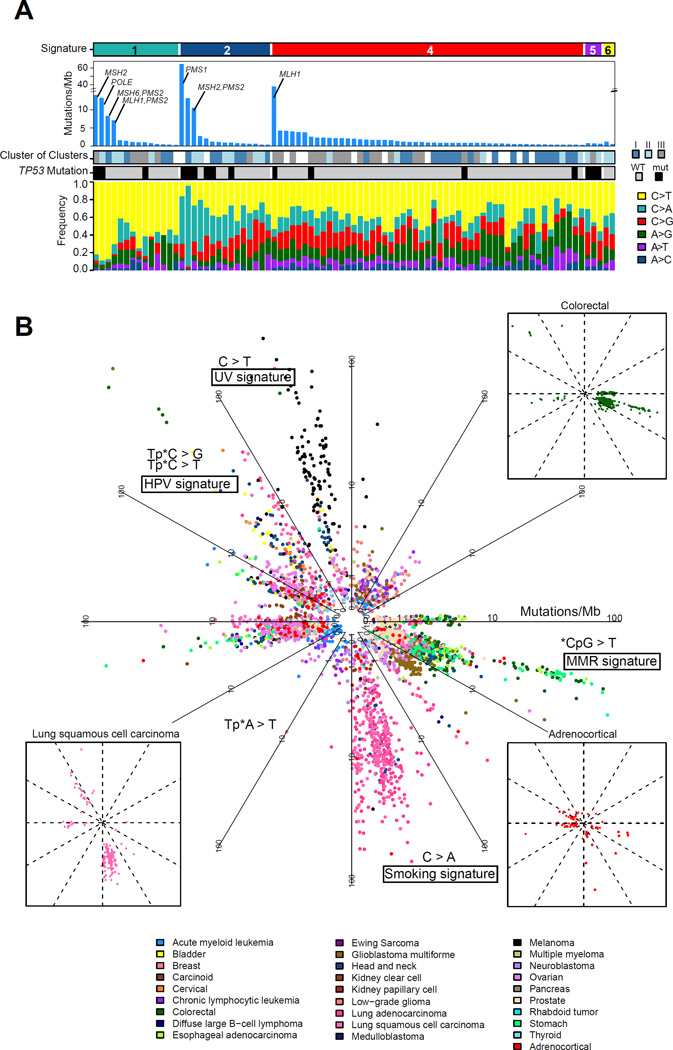

The accumulation of somatic mutations in cancer is caused by mutational processes that can be deconvoluted as mutational signatures (Alexandrov et al., 2013). To examine mutational processes in ACC, we extracted 6 mutational signatures from 85 ACCs (mutation number ≥ 10) and about 2,900 other cancers using non-negative matrix factorization (Figure S6B). We compared the six signatures with the 22 signatures from an independent study (Alexandrov et al., 2013). Signature 1 resembled the age and DNA mismatch repair deficiency signatures, all featuring C>T substitution in the CG context. Signature 2 resembled the smoking signature featuring C>A substitution in the CG context. Signature 5 resembled UV and APOBEC signatures featuring C>G, C>T, and C>T substitutions in the contexts of TC, CC and TC, respectively. We did not find an association between signatures and sample country of origin (p value=0.9, Fisher’s exact test). The majority of ACCs exhibited signatures 1, 2 and 4 (Figure 6A). Signature 1 captured the majority of gastrointestinal cancers (stomach, esophageal, colorectal) but also four ACC with a relatively high mutation frequency, all of which harbored mutations in the DNA mismatch repair pathway (Figure 6B). One case with a germline MSH6 mutation but relatively modest mutation density (0.51 mutations/Mb) also clustered with this signature. The smoking associated adenocarcinoma and squamous cell lung cancers in signature 2 also featured four high mutation frequency ACCs. Smoking has been listed as an ACC risk factor (Hsing et al., 1996). A set of Human papillomavirus (HPV)-driven cancers, including cervical, bladder and head and neck cancers, clustered together but did not capture any ACC. We analyzed RNA and exome sequencing data for microbial sequence reads (Chu et al., 2014) and identified human herpes virus sequences in nine exomes but not HPV sequence reads. De novo assembly of herpes virus sequences confirmed their presence but returned no evidence for viral genomic integration (Figure S6C).

Figure 6. Pan-cancer mutational signature analysis.

(A) Distribution of the mutational signatures extracted from pan-cancer analysis in the ACC cohort. Signature 2 is enriched in the cluster of clusters groups 1 and 2. (B) Circular plot of the mutational signatures in ACC and approximately 2,900 tumor samples from other cancer types. The distance to the center represents coding mutation density. Three small illustrations highlight ACC, lung squamous cell carcinoma and colorectal cancer to demonstrate their similarities in the featured directions. See also Figure S6.

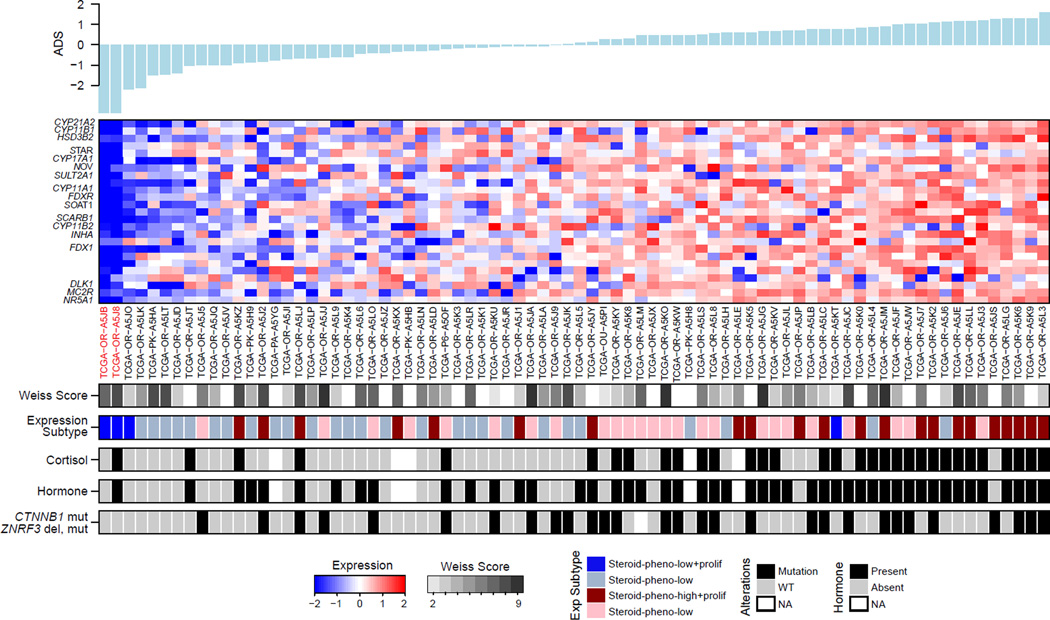

Molecular correlates of ACC pathology and adrenocortical differentiation

We evaluated adrenocortical differentiation by using 25 genes with very high expression levels in the adult adrenal cortex and that are of importance for adrenal function, including steroidogenic enzymes, cholesterol transporters and their transcriptional regulator, SF1 (NR5A1) (Figure S7A and Table S4). We derived a single metric, termed Adrenocortical Differentiation Score (ADS), to measure adrenocortical differentiation (Figure 7). Sorting the tumors according to their ADS values we observed that functional tumors showed higher ADS values, which did not correlate with Weiss histopathology score (p value=0.41, ANOVA). TP53 mutations were present across the spectrum of ADS values (p value=0.56, Fisher’s exact test), whereas Wnt-related mutations appeared to be enriched among tumors with higher ADS values (p value=0.0091, Fisher’s exact test). Not surprisingly, the two sarcomatoid tumors had the lowest ADS values with very low expression of NR5A1 and steroidogenic enzymes (Figure S7B). One such patient had elevated serum cortisol levels, suggesting a mixed histology in which a differentiated component expressed steroidogenic enzymes and an undifferentiated component did not. The other tumor was histologically mixed with separate components of usual and sarcomatoid ACC. We suggest that these sarcomatoid, NR5A1-negative tumors do indeed represent dedifferentiated ACCs, rather than retroperitoneal sarcomas.

Figure 7. Distribution of Adrenal Differentiation Score (ADS).

The 25-gene signature is shown in the expression heatmap. Adrenal cortex differentiation markers are listed on the left. Two sarcomatoid cases are indicated in red. See also Figure S7 and Table S4.

DISCUSSION

As part of TCGA, we present an integrated molecular characterization of a large cohort of ACC. The tumors were derived from four continents and thus represent a near-global sampling of this disease. The data presented here represents a resource for future investigations to facilitate ACC research across myriad avenues, including via pan-cancer analysis.

Our study builds upon prior efforts on adult ACC from European (Assie et al., 2014) and North American patients (Juhlin et al., 2015), as well as pediatric ACC patients from North America and Brazil (Pinto et al., 2015). Using high quality multidimensional genomic data, we confirm many alterations as essential for ACC development and progression but also expand the somatic genetic landscape of ACC to nearly double the known ACC driver genes. The high frequency of PRKAR1A mutations expands the role of PKA signaling in ACC and is consistent with PRKACA somatic mutations being the founder lesion of benign adrenal tumor associated with endocrinopathies such as Cushing syndrome (Beuschlein et al., 2014). By integrating data from multiple platforms we demonstrated the critical role of WGD. While WGD is common across cancer (Zack et al., 2013), an association between WGD and patient outcome has only been reported in ovarian cancer (Carter et al., 2012). The exceptional high level of tumor purity and the clear evidence that WGD is a marker of tumor progression make ACC a model disease for better understanding of the mechanisms that result in doubling and the molecular context needed to sustain it.

Weiss and colleagues (Weiss et al., 1989) first proposed that ACC consists of two pathologic classes that have different mitotic rates and distinct clinical outcomes. This proliferation-based two-grade (low and high) system has been confirmed by several transcriptome studies (de Reynies et al., 2009; Giordano et al., 2009) and has been clinically implemented by some centers (Giordano, 2011). We confirmed the two-grade classification with mRNA-seq data and importantly, used multidimensional data to extend the molecular classification to three classes that have markedly distinct biological properties and significantly different patient outcomes. Clinical implementation of this three-class grading system using DNA methylation profiles could facilitate improved patient care, although additional translational efforts are needed for its implementation. Despite these uncertainties, our results represent an extensive ensemble of molecular ACC subtypes and thus are likely to be useful in directing future development of clinically applicable classifiers. Moreover, our results illustrate how molecular data, combined with traditional clinicopathologic assessment, might inform therapeutic decisions and lead to advances in patient outcomes. The diversity of genomic alterations, especially the significant copy number changes seen in the majority of ACC, suggests that combined inhibition of disease pathways, however challenging, likely holds the key to successful targeted therapy for ACC.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tumor and normal samples were obtained from patients after informed consent and with approval from local Institutional Review Boards (RIB). Details on all contributing Centers and their IRB approval can be found in the Supplemental Information. DNA, RNA and protein were purified and distributed throughout the TCGA network. In total, 91 primary tumors with associated clinicopathologic data were assayed on at least one molecular profiling platform. Platforms included exome sequencing, mRNA sequencing, miRNA sequencing, SNP arrays, DNA methylation arrays, and reverse phase protein arrays. Mutation calling was performed by 5 independent callers, and a voting mechanism was used to generate the final mutation set. MutSigCV (version 1.4) was used to determine significantly mutated genes (Lawrence et al., 2013). GISTIC2.0 was used to identify recurrent deletion and amplification peaks(Mermel et al., 2011). Consensus clustering was used to derive miRNA, mRNA, methylation and protein subtypes. Tumor purity, ploidy and whole genome doubling were determined by ABSOLUTE (Carter et al., 2012). The data and analysis results can be explored through TCGA data portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/tcgaCancerDetails.jsp?diseaseType=ACC), the Broad Institute GDAC FireBrowse portal (http://firebrowse.org/?cohort=ACC), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/public-portal/study.do?cancer_study_id=acc_tcga), Regulome Explorer (http://explorer.cancerregulome.org/all_pairs/?dataset=TCGA_ACC). See also the Supplemental Experimental Procedures and the ACC publication page (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/docs/publications/acc_2016/).

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Adrenocortical carcinoma is a rare endocrine cancer with limited therapeutic options and overall poor outcome. We comprehensively analyzed 91 ACC specimens from four continents using state of the art genomic technologies and computational methods. In addition to identification of ACC driver genes, pathways and refined subtypes, our analysis revealed whole genome doubling (WGD) as a milestone in disease progression. Our findings suggest that ACC can serve as a model for how WGD influences disease progression. Our dataset is standardized with other TCGA studies, fully available at the TCGA Data Portal, and thus will serve as a valuable research resource.

Highlights.

Standardized molecular data from 91 cases of adrenocortical carcinoma

Driver genes including TP53,ZNFR3,CTNNB1, PRKAR1A,CCNE1 and TERF2

Whole genome doubling event is a marker for ACC progression

Three prognostic molecular subtypes captured by a DNA methylation signature

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients and families who contributed to this study, to Ina Felau, Margi Sheth and Jiashan (Julia) Zhang for project management. Supported by the following grants from the United States National Institutes of Health: 5U24CA143799, 5U24CA143835, 5U24CA143840, 5U24CA143843, 5U24CA143845, 5U24CA143848, 5U24CA143858, 5U24CA143866, 5U24CA143867, 5U24CA143882, 5U24CA143883, 5U24CA144025, U54HG003067, U54HG003079, and U54HG003273, P30CA16672.

CONSORTIA

The members of The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network for this project are Siyuan Zheng, Roel G. W. Verhaak, Thomas J. Giordano, Gary D. Hammer, Andrew D. Cherniack, Ninad Dewal, Richard A. Moffitt, Ludmila Danilova, Bradley A. Murray, Antonio M. Lerario, Tobias Else, Theo A. Knijnenburg, Giovanni Ciriello, Seungchan Kim, Guillaume Assié, Olena Morozova, Rehan Akbani, Juliann Shih, Katherine A. Hoadley, Toni K. Choueiri, Jens Waldmann, Ozgur Mete, A. Gordon Robertson, Hsin-Tu Wu, Benjamin J. Raphael, Matthew Meyerson, Michael J. Demeure, Felix Beuschlein, Anthony J. Gill, Stan B. Sidhu, Madson Almeida, Maria Candida Barisson Fragoso, Leslie M. Cope, Electron Kebebew, Mouhammed Amir Habra, Timothy G. Whitsett, Kimberly J. Bussey, William E. Rainey, Sylvia L. Asa, Jérôme Bertherat, Martin Fassnacht, David A. Wheeler, Christopher Benz, Adrian Ally, Miruna Balasundaram, Reanne Bowlby, Denise Brooks, Yaron S.N. Butterfield, Rebecca Carlsen, Noreen Dhalla, Ranabir Guin, Robert A. Holt, Steven J.M. Jones, Katayoon Kasaian, Darlene Lee, Haiyan I. Li, Lynette Lim, Yussanne Ma, Marco A. Marra, Michael Mayo, Richard A. Moore, Andrew J. Mungall, Karen Mungall, Sara Sadeghi, Jacqueline E. Schein, Payal Sipahimalani, Angela Tam, Nina Thiessen, Peter J. Park, Matthias Kroiss, Jianjiong Gao, Chris Sander, Nikolaus Schultz, Corbin D. Jones, Raju Kucherlapati, Piotr A. Mieczkowski, Joel S. Parker, Charles M. Perou, Donghui Tan, Umadevi Veluvolu, Matthew D. Wilkerson, D. Neil Hayes, Marc Ladanyi, Marcus Quinkler, J. Todd Auman, Ana Claudia Latronico, Berenice B. Mendonca, Mathilde Sibony, Zack Sanborn, Michelle Bellair, Christian Buhay, Kyle Covington, Mahmoud Dahdouli, Huyen Dinh, Harsha Doddapaneni, Brittany Downs, Jennifer Drummond, Richard Gibbs, Walker Hale, Yi Han, Alicia Hawes, Jianhong Hu, Nipun Kakkar, Divya Kalra, Ziad Khan, Christine Kovar, Sandy Lee, Lora Lewis, Margaret Morgan, Donna Morton, Donna Muzny, Jireh Santibanez, Liu Xi, Bertrand Dousset, Lionel Groussin, Rossella Libé, Lynda Chin, Sheila Reynolds, Ilya Shmulevich, Sudha Chudamani, Jia Liu, Laxmi Lolla, Ye Wu, Jen Jen Yeh, Saianand Balu, Tom Bodenheimer, Alan P. Hoyle, Stuart R. Jefferys, Shaowu Meng, Lisle E. Mose, Yan Shi, Janae V. Simons, Matthew G. Soloway, Junyuan Wu, Wei Zhang, Kenna R. Mills Shaw, John A. Demchok, Ina Felau, Margi Sheth, Roy Tarnuzzer, Zhining Wang, Liming Yang, Jean C. Zenklusen, Jiashan (Julia) Zhang, Tanja Davidsen, Catherine Crawford, Carolyn M. Hutter, Heidi J. Sofia, Jeffrey Roach, Wiam Bshara, Carmelo Gaudioso, Carl Morrison, Patsy Soon, Shelley Alonso, Julien Baboud, Todd Pihl, Rohini Raman, Qiang Sun, Yunhu Wan, Rashi Naresh, Harindra Arachchi, Rameen Beroukhim, Scott L. Carter, Juok Cho, Scott Frazer, Stacey B. Gabriel, Gad Getz, David I. Heiman, Jaegil Kim, Michael S. Lawrence, Pei Lin, Michael S. Noble, Gordon Saksena, Steven E. Schumacher, Carrie Sougnez, Doug Voet, Hailei Zhang, Jay Bowen, Sara Coppens, Julie M. Gastier-Foster, Mark Gerken, Carmen Helsel, Kristen M. Leraas, Tara M. Lichtenberg, Nilsa C. Ramirez, Lisa Wise, Erik Zmuda, Stephen Baylin, James G. Herman, Janine LoBello, Aprill Watanabe, David Haussler, Amie Radenbaugh, Arjun Rao, Jingchun Zhu, Detlef K. Bartsch, Silviu Sbiera, Bruno Allolio, Timo Deutschbein, Cristina Ronchi, Victoria M. Raymond, Michelle Vinco, Lina Shao, Linda Amble, Moiz S. Bootwalla, Phillip H. Lai, David J. Van Den Berg, Daniel J. Weisenberger, Bruce Robinson, Zhenlin Ju, Hoon Kim, Shiyun Ling, Wenbin Liu, Yiling Lu, Gordon B. Mills, Kanishka Sircar, Qianghu Wang, Kosuke Yoshihara, Peter W. Laird, Yu Fan, Wenyi Wang, Eve Shinbrot, Martin Reincke, John N. Weinstein, Sam Meier, Timothy Defreitas.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The TCGA consortium contributed collectively to this study. Project activities were coordinated by the National Cancer Institute and National Human Genome Research Institute Project Teams. Initial guidance in the project design was provided by the Disease Working Group. We also acknowledge the following TCGA investigators of the Analysis Working Group, who contributed substantially to the analysis and writing of this manuscript: project leaders: R.G.W.V., T.J.G. and G.D.H.; data coordinator: S.Z.; manuscript coordinator: S.Z., T.J.G. and R.G.W.V.; analysis coordinator: S.Z.; writing team: S.Z., G.D.H, T.J.G., and R.G.W.V. DNA sequence analysis: N.D., D.A.W., S.Z., R.G.W.V.; mRNA analysis: R.A.M., K.A.H., S.Z. and O.M.; miRNA analysis: G.A.R.; DNA copy number analysis: A.D.C., B.A.M., S.Z., J.S. and R.G.W.V.; DNA methylation analysis: L.D. and L.M.C.; pathway analysis: S.K., T.A.K., B.J.R. S.Z. and T.G.W.; clinical data pathology and disease expertise: T.J.G., G.D.H., T.E., A.M.L., M.F., J.B., W.E.R., K.J.B. and S.L.A.

REFERENCES

- Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Borresen-Dale AL, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmo J, Medeiros S, Carneiro V, Greene E, Levy I, Nesterova M, Lyssikatos C, Horvath A, Carney JA, Stratakis CA. A large family with Carney complex caused by the S147G PRKAR1A mutation shows a unique spectrum of disease including adrenocortical cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:351–359. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assie G, Letouze E, Fassnacht M, Jouinot A, Luscap W, Barreau O, Omeiri H, Rodriguez S, Perlemoine K, Rene-Corail F, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:607–612. doi: 10.1038/ng.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertherat J, Groussin L, Sandrini F, Matyakhina L, Bei T, Stergiopoulos S, Papageorgiou T, Bourdeau I, Kirschner LS, Vincent-Dejean C, et al. Molecular and functional analysis of PRKAR1A and its locus (17q22–24) in sporadic adrenocortical tumors: 17q losses, somatic mutations, and protein kinase A expression and activity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5308–5319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuschlein F, Fassnacht M, Assie G, Calebiro D, Stratakis CA, Osswald A, Ronchi CL, Wieland T, Sbiera S, Faucz FR, et al. Constitutive activation of PKA catalytic subunit in adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1019–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilimoria KY, Shen WT, Elaraj D, Bentrem DJ, Winchester DJ, Kebebew E, Sturgeon C. Adrenocortical carcinoma in the United States: treatment utilization and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2008;113:3130–3136. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco MA. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:611–622. doi: 10.1038/nrg1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calebiro D, Hannawacker A, Lyga S, Bathon K, Zabel U, Ronchi C, Beuschlein F, Reincke M, Lorenz K, Allolio B, et al. PKA catalytic subunit mutations in adrenocortical Cushing’s adenoma impair association with the regulatory subunit. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5680. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SL, Cibulskis K, Helman E, McKenna A, Shen H, Zack T, Laird PW, Onofrio RC, Winckler W, Weir BA, et al. Absolute quantification of somatic DNA alterations in human cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:413–421. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan BC, Li Q, Chow SK, Ching AK, Liew CT, Lim PL, Lee KK, Chan JY, Chui YL. BRE enhances in vivo growth of tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Sadeghi S, Raymond A, Jackman SD, Nip KM, Mar R, Mohamadi H, Butterfield YS, Robertson AG, Birol I. BioBloom tools: fast, accurate and memory-efficient host species sequence screening using bloom filters. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3402–3404. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriello G, Miller ML, Aksoy BA, Senbabaoglu Y, Schultz N, Sander C. Emerging landscape of oncogenic signatures across human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/ng.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoli T, de Lange T. Telomere-driven tetraploidization occurs in human cells undergoing crisis and promotes transformation of mouse cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Reynies A, Assie G, Rickman DS, Tissier F, Groussin L, Rene-Corail F, Dousset B, Bertagna X, Clauser E, Bertherat J. Gene expression profiling reveals a new classification of adrenocortical tumors and identifies molecular predictors of malignancy and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1108–1115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.5678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruijter TC, de Hoon TP, Slaats J, de Vries B, Janssen MJ, van Wezel T, Aarts MJ, van Engeland M, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Van Neste L, Veeck J. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue epigenomics using Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip assays. Lab Invest. 2015;95:833–842. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Mangino M, Aviv A, Spector T, Durbin R, Consortium UK. Estimating telomere length from whole genome sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e75. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else T, Giordano TJ, Hammer GD. Evaluation of telomere length maintenance mechanisms in adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1442–1449. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else T, Kim AC, Sabolch A, Raymond VM, Kandathil A, Caoili EM, Jolly S, Miller BS, Giordano TJ, Hammer GD. Adrenocortical carcinoma. Endocr Rev. 2014a;35:282–326. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else T, Williams AR, Sabolch A, Jolly S, Miller BS, Hammer GD. Adjuvant therapies and patient and tumor characteristics associated with survival of adult patients with adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014b;99:455–461. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassnacht M, Johanssen S, Quinkler M, Bucsky P, Willenberg HS, Beuschlein F, Terzolo M, Mueller HH, Hahner S, Allolio B, et al. Limited prognostic value of the 2004 International Union Against Cancer staging classification for adrenocortical carcinoma: proposal for a Revised TNM Classification. Cancer. 2009;115:243–250. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassnacht M, Kroiss M, Allolio B. Update in adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4551–4564. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, Wooster R, Rahman N, Stratton MR. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TJ. The argument for mitotic rate-based grading for the prognostication of adrenocortical carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:471–473. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31820bcf21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TJ, Kuick R, Else T, Gauger PG, Vinco M, Bauersfeld J, Sanders D, Thomas DG, Doherty G, Hammer G. Molecular classification and prognostication of adrenocortical tumors by transcriptome profiling. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:668–676. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TJ, Thomas DG, Kuick R, Lizyness M, Misek DE, Smith AL, Sanders D, Aljundi RT, Gauger PG, Thompson NW, et al. Distinct transcriptional profiles of adrenocortical tumors uncovered by DNA microarray analysis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:521–531. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63846-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh G, Scholl UI, Healy JM, Choi M, Prasad ML, Nelson-Williams C, Kunstman JW, Korah R, Suttorp AC, Dietrich D, et al. Recurrent activating mutation in PRKACA in cortisol-producing adrenal tumors. Nat Genet. 2014;46:613–617. doi: 10.1038/ng.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Zack TI, Morris LG, Lin K, Hukkelhoven E, Raheja R, Tan IL, Turcan S, Veeriah S, Meng S, et al. Pan-cancer genetic analysis identifies PARK2 as a master regulator of G1/S cyclins. Nat Genet. 2014;46:588–594. doi: 10.1038/ng.2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF, Jiao Y, Klein AP, Edil BH, Shi C, Bettegowda C, Rodriguez FJ, Eberhart CG, Hebbar S, et al. Altered telomeres in tumors with ATRX and DAXX mutations. Science. 2011;333:425. doi: 10.1126/science.1207313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing AW, Nam JM, Co Chien HT, McLaughlin JK, Fraumeni JF., Jr Risk factors for adrenal cancer: an exploratory study. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:432–436. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960208)65:4<432::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, Kryukov GV, Chin L, Garraway LA. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science. 2013;339:957–959. doi: 10.1126/science.1229259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhlin CC, Goh G, Healy JM, Fonseca AL, Scholl UI, Stenman A, Kunstman JW, Brown TC, Overton JD, Mane SM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing characterizes the landscape of somatic mutations and copy number alterations in adrenocortical carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E493–E502. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Kim S. EDDY: a novel statistical gene set test method to detect differential genetic dependencies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e60. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner LS, Sandrini F, Monbo J, Lin JP, Carney JA, Stratakis CA. Genetic heterogeneity and spectrum of mutations of the PRKAR1A gene in patients with the carney complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:3037–3046. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.20.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Mermel CH, Robinson JT, Garraway LA, Golub TR, Meyerson M, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Getz G. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature. 2014;505:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, Mermel CH, Roberts SA, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiserson MD, Vandin F, Wu HT, Dobson JR, Eldridge JV, Thomas JL, Papoutsaki A, Kim Y, Niu B, McLellan M, et al. Pan-cancer network analysis identifies combinations of rare somatic mutations across pathways and protein complexes. Nat Genet. 2015;47:106–114. doi: 10.1038/ng.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letouze E, Rosati R, Komechen H, Doghman M, Marisa L, Fluck C, de Krijger RR, van Noesel MM, Mas JC, Pianovski MA, et al. SNP array profiling of childhood adrenocortical tumors reveals distinct pathways of tumorigenesis and highlights candidate driver genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1284–E1293. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TT, Brown TC, Juhlin CC, Andreasson A, Wang N, Backdahl M, Healy JM, Prasad ML, Korah R, Carling T, et al. The activating TERT promoter mutation C228T is recurrent in subsets of adrenal tumors. Endocr-Relat Cancer. 2014;21:427–434. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser RS, DePinho RA. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science. 2002;297:565–569. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5581.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson A, Hormozdiari F, Zayed A, Giuliany R, Ha G, Sun MG, Griffith M, Heravi Moussavi A, Senz J, Melnyk N, et al. deFuse: an algorithm for gene fusion discovery in tumor RNA-Seq data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1001138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J, Panesar NS, Chan KT, Lai FM, Xia N, Wang Y, Johnson PJ, Chan JY. Differential expression of a stress-modulating gene, BRE, in the adrenal gland, in adrenal neoplasia, and in abnormal adrenal tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:491–500. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BS, Gauger PG, Hammer GD, Giordano TJ, Doherty GM. Proposal for modification of the ENSAT staging system for adrenocortical carcinoma using tumor grade. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery / Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie. 2010;395:955–961. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0698-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios R, Sugawara I. Hydrocortisone abrogates proliferation of T cells in autologous mixed lymphocyte reaction by rendering the interleukin-2 Producer T cells unresponsive to interleukin-1 and unable to synthesize the T-cell growth factor. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 1982;15:25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1982.tb00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto EM, Chen X, Easton J, Finkelstein D, Liu Z, Pounds S, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Lund TC, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, et al. Genomic landscape of paediatric adrenocortical tumours. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6302. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond VM, Everett JN, Furtado LV, Gustafson SL, Jungbluth CR, Gruber SB, Hammer GD, Stoffel EM, Greenson JK, Giordano TJ, Else T. Adrenocortical carcinoma is a lynch syndrome-associated cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3012–3018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.0988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozek LS, Rennert G, Gruber SB. APC E1317Q is not associated with Colorectal Cancer in a population-based case-control study in Northern Israel. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2006;15:2325–2327. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SA, Weinberg RA. Telomeres: cancer to human aging. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2006;22:531–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirlwell C, Eymard M, Feber A, Teschendorff A, Pearce K, Lechner M, Widschwendter M, Beck S. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation27 BeadChip. Methods. 2010;52:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissier F, Cavard C, Groussin L, Perlemoine K, Fumey G, Hagnere AM, Rene-Corail F, Jullian E, Gicquel C, Bertagna X, et al. Mutations of beta-catenin in adrenocortical tumors: activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is a frequent event in both benign and malignant adrenocortical tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7622–7627. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Garcia W, Zheng S, Sivachenko A, Vegesna R, Wang Q, Yao R, Berger MF, Weinstein JN, Getz G, Verhaak RG. PRADA: pipeline for RNA sequencing data analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2224–2226. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Allen EM, Wagle N, Stojanov P, Perrin DL, Cibulskis K, Marlow S, Jane-Valbuena J, Friedrich DC, Kryukov G, Carter SL, et al. Whole-exome sequencing and clinical interpretation of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples to guide precision cancer medicine. Nat Med. 2014;20:682–688. doi: 10.1038/nm.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss LM, Medeiros LJ, Vickery AL., Jr Pathologic features of prognostic significance in adrenocortical carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:202–206. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198903000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martinez E, Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Trevino V, Shen H, Laird PW, Levine DA, et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2612. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K, Wang Q, Torres-Garcia W, Zheng S, Vegesna R, Kim H, Verhaak RG. The landscape and therapeutic relevance of cancer-associated transcript fusions. Oncogene. 2015;34:4845–4854. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zack TI, Schumacher SE, Carter SL, Cherniack AD, Saksena G, Tabak B, Lawrence MS, Zhang CZ, Wala J, Mermel CH, et al. Pan-cancer patterns of somatic copy number alteration. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lu H. Signaling to p53: ribosomal proteins find their way. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.