Abstract

The first total synthesis of a chromodorolide diterpenoid is described. The synthesis features a bimolecular radical addition/cyclization/fragmentation cascade that unites butenolide and trans-hydrindane fragments while fashioning two C–C bonds and stereoselectively forming three of the ten contiguous stereocenters of chromodorolide B

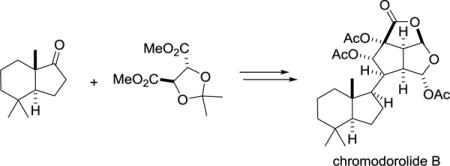

TOC image

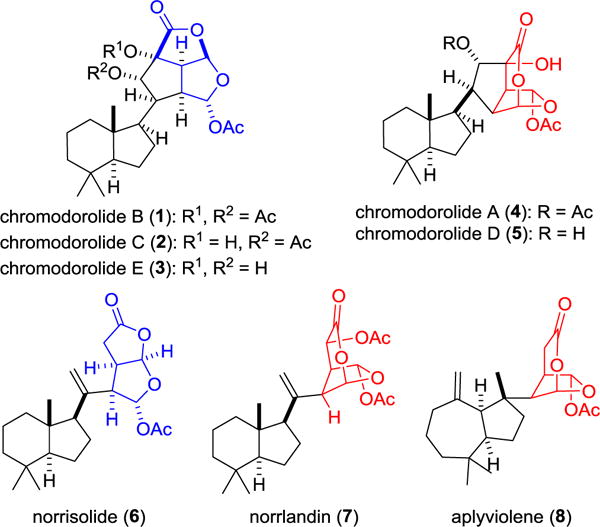

Chromodorolides A–E (1–5), which contain 10 contiguous stereocenters, are among the most structurally complex members of the rearranged spongian diterpenoids (Figure 1).1,2 They have been isolated from nudibranches in the genus Chromodoris and the encrusting sponges on which these nudibranches potentially feed. The 6-acetoxy-2,7-dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-one and 7-acetoxy-2,8-dioxabicyclo[3.3.0]octan-3-one rings embedded in the chromodorolides are distinctive features of many rearranged spongian diterpenes such as norrisolide (6),3 norrlandin (7),4 and aplyviolene (8).5 In the chromodorolides, these dioxabicyclic rings are appended to an additional oxygenated cyclopentane ring. Although modest in vitro antitumor, nematocidal and antimicrobial activities have been reported,1b,c,e the chromodorolides and analogues are of most interest for their potential effects on the Golgi apparatus.5c We report herein the first total synthesis of a chromodorolide, (−)-chromodorolide B (1), by a concise sequence that features a bimolecular radical addition/cyclization/fragmentation (ACF) cascade.

Figure 1.

The chromodorolides and three structurally related rearranged spongian diterpenoids that also contain 6-acetoxy-2,7-dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-one (red) and 7-acetoxy-2,8-dioxabicyclo[3.3.0]octan-3-one (blue) fragments.

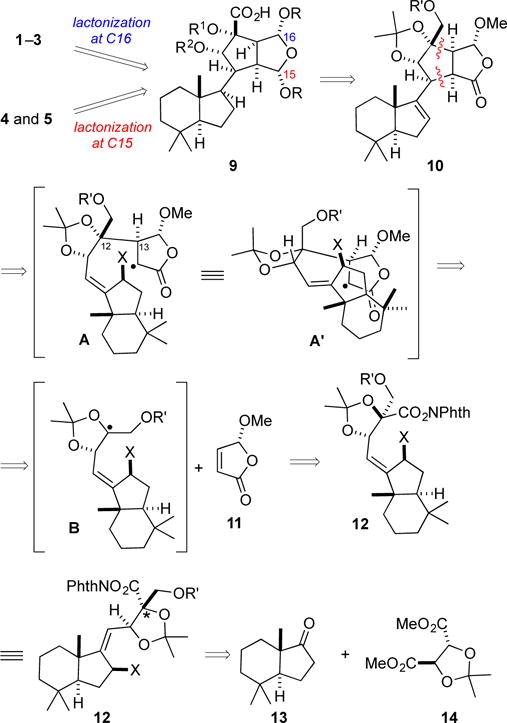

We envisaged that the chromodorolides containing distinctive dioxatricyclic fragments of both fused (1, 2, 3) and bridged (4, 5) motifs could be accessible from a common tetracyclic acid 9 (Scheme 1). In this analysis, the substituents at C-15 and C-16 of acid 9 would be differentiated to allow selective lactonization to construct either dioxatricyclic fragment. Further simplification of acid 9 leads to intermediate 10 having the C12 hydrocarbon and the highly oxidized fragment joined at a vinylic carbon of the hydrophobic fragment.6 On the basis of our recent experience showing that fragment couplings of nucleophilic tertiary radicals with alkenes can be high yielding,5b we envisioned a cascade sequence in which trisubstituted carbon radical B, generated by visible-light photoredox fragmentation of the N-acyloxyphthalimide substituent of intermediate 12,7 would couple with (R)-4-methoxybutenolide (11)8 to generate α-acyloxy-radical intermediate A, which was hoped would undergo intramolecular 5-exo cyclization from a conformation such as A′ depicted in Scheme 1 that minimizes destabilizing allylic A1,3 interactions. The cascade would then be terminated by β-fragmentation of the adjacent C–X (X = halide) bond to deliver the desired coupled product 10.9 Essential for success of this proposed sequence would be correctly setting the C-12 and C-13 stereocenters in the union of the two fragments to form intermediate A. The desired configuration at C-13 was anticipated from the radical addition to the butenolide occurring preferentially from the face opposite the methoxy substituent.10 Unclear at the outset was from which face radical intermediate B would couple, as few C–C bond-forming reactions of 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolane trisubstituted radicals have been described and preferences for both syn and anti addition have been reported.11 In an exploratory model study, we confirmed that radical coupling at such a carbon would preferentially occur from the desired face syn to the vicinal substituent.12 Further simplification of intermediate 12 leads to two readily available precursors: (S,S)-trimethylhydrindanone 133 and (R,R)-tartaric acid-derived acetonide 14.

Scheme 1.

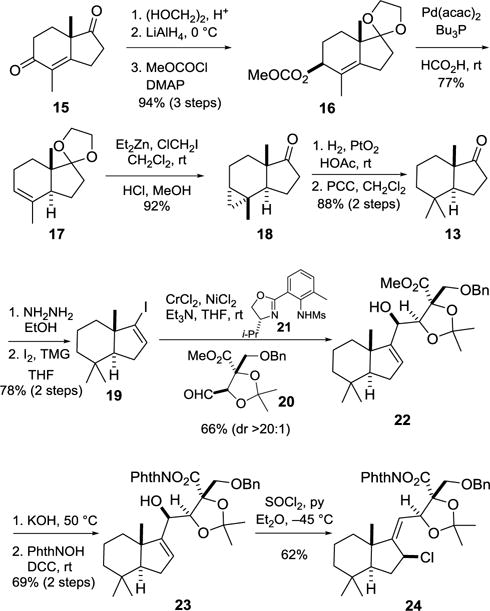

Although several enantioselective routes to trans-hydrindanone 13 have been reported,3,13 a readily scalable, efficient synthesis had not been described. During our investigations, such a route was developed (Scheme 2). This sequence began with commercially available (S)-enedione 15,14 which alternatively can be prepared in 98% ee on a large scale in two steps from 2-methylcyclopentane-1,3-dione.15 Selective ketalization of 15, stereoselective 1,2-reduction of the enone, and methoxycarbonylation provided β-allylic carbonate 16 in 94% overall yield. Palladium-catalyzed reductive transposition of the allylic carbonate then gave trans-hydrindene ketal 17 in 77% yield.16 Cyclopropanation of trisubstituted alkene 17 with diethylzinc and chloroiodomethane,17 followed by acidic workup, produced ketone 18. Subjection of cyclopropane 18 to hydrogenolysis conditions, followed by oxidation of the resulting secondary alcohol, delivered trans-hydrindanone 13 in 88% yield over two steps. The seven-step sequence summarized in Scheme 2 provides (S,S)-13 of high enantiomeric purity (98% ee) on multigram scales in 59% overall yield from enedione 15.

Scheme 2.

In six subsequent steps, hydrindanone 13 was elaborated to radical coupling precursor 24. This sequence began by conversion of ketone 13 to known vinyl iodide 19.3 The other fragment, sensitive aldehyde 20, is accessible in three steps from acetonide 14.12 A variety of standard conditions were examined for the Nozaki-Hiyama-Kishi coupling of iodide 19 with aldehyde 20;18 however, only low yields (<20%) and modest diastereoselectivities (3:1) were observed. In contrast, in the presence of (R)-sulfonamide ligand 21 introduced by Kishi,19 allylic alcohol 22 was obtained in 66% yield as a single alcohol epimer. Saponification of the ester and subsequent esterification with N-hydroxyphthalimide provided crystalline ester 23 in 69% yield, whose structure was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray analysis.20a Exposure of this intermediate to thionyl chloride and pyridine at −45 °C in diethyl ether mediated suprafacial allylic transposition21 to give crystalline allylic chloride 2420b in 62% yield.

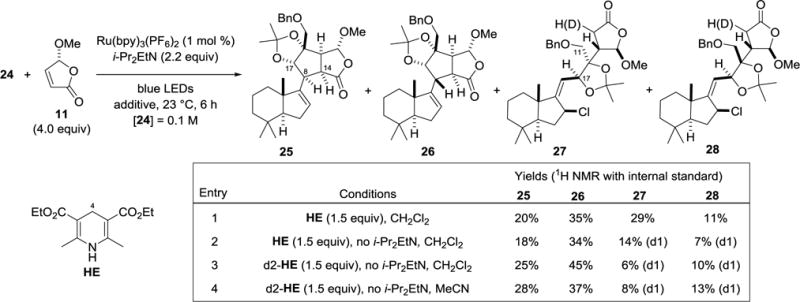

We then examined the key ACF cascade that ideally would set two new C–C bonds and four stereocenters of 1 in a single step. Initial experiments employed conditions previously used in the coupling of tertiary radicals with (R)-methoxybutenolide 11 (Scheme 3, entry 1).7b,10 Two products arising from the ACF cascade sequence, 25 and 26, were isolated.22,23 Detailed analysis of their NMR spectra showed that these products were epimeric at C-8. Particularly diagnostic were 1H NOE correlations between the C-8, C-17, and C-14 methine hydrogens.12 Confirmation of the structures of these epimers was obtained by eventual conversion of cascade product 25 to (−)-chromodorolide B (vide infra). The third predominant product retained the alkylidene chlorohydrindane fragment of precursor 24 and showed 1H NOE data consistent with a cis relationship of the allylic hydrogen at C-17 and the benzyloxymethyl substituent. Products 25–27 all arose from coupling of the dioxolane radical with the chiral butenolide syn to the vicinal hydrophobic fragment, with 27 resulting from premature trapping of the α-acyl radical intermediate. ACF product 25 derives from the 5-exo cyclization occurring in the desired orientation as depicted in intermediate ‘A’ (Scheme 1), whereas epimer 26 arises from the cyclization taking place from the alternate face of the alkylidene double bond. The fourth product 28 is tentatively assigned as the C12 epimer of 27,24 which would arise from radical addition to the butenolide occurring from the face of the 1,3-dioxolane anti to the vicinal hydrophobic fragment.12

Scheme 3.

A number of experiments were conducted to minimize the formation of byproduct 27 arising from premature quenching of the coupled radical.12 Removal of i-Pr2EtN, which was expected to minimize amine-mediated reduction of intermediate ‘A’ to its corresponding enolate,7b reduced formation of byproduct 27 (entry 2). However, as intermediate ‘A’ can also be quenched by hydrogen-atom transfer from the Hantzsch ester,7b this pathway also needed attenuation. Employing 4,4-dideuterio Hantzsch ester in the absence of i-Pr2EtN (entry 3), which was expected to minimize hydrogen-atom transfer to the initially generated coupled radical, significantly decreased the formation of product 27, increasing the combined yield of ACF products 25 and 26 to 70% yield. Attempts thus far to improve the ratio of epimeric products 25/26 have been less successful.12 This ratio was slightly improved in reactions conducted in acetonitrile (entry 4), allowing product 25 to be formed in 28% yield (by 1H NMR with internal standard) and isolated in 27% yield.

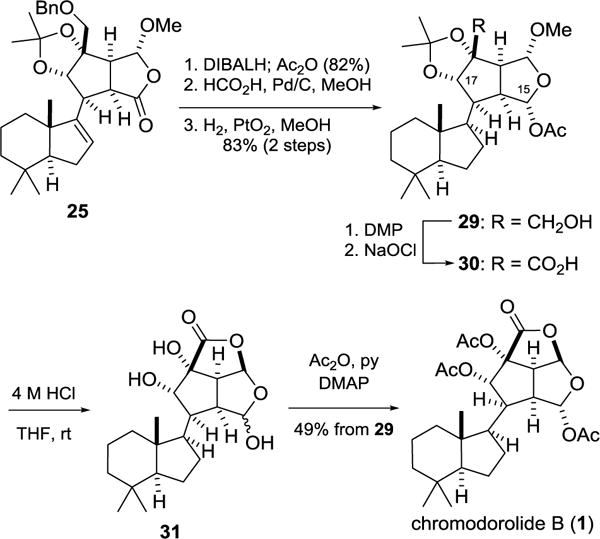

As summarized in Scheme 4, cascade product 25 was readily transformed to (−)-chromodorolide B (1). Reduction of the lactone carbonyl of 25 with (i-Bu)2AlH at −78 °C and in situ acetylation with Ac2O and DMAP afforded the acetoxy acetal as a single epimer at C-15. 1H NOE correlations between the C-17 and C-15 methine hydrogens revealed that the acetoxy group was oriented α.25 Following removal of the benzyl protecting group, the trisubstituted double bond was hydrogenated selectively (dr > 20:1) from the face opposite the angular methyl group to yield product 29 in 68% overall yield from 25. Without purifying subsequent intermediates, 29 was oxidized to carboxylic acid 30, which upon exposure to 4 M HCl in THF at room temperature underwent acetonide deprotection and lactonization to form lactol 31. Exhaustive acetylation of this triol gave (−)-chromodorolide B (1), [α]D = −66.8 (c = 0.12, CH2Cl2), in 49% overall yield from intermediate 29. This product showed 1H and 13C NMR data and optical rotation in close accord to those reported for a natural sample.1b,c In addition, synthetic 1 provided single crystals, which allowed the structure of chromodorolide B to be unambiguously confirmed by X-ray analysis.20c

Scheme 4.

In summary, the enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-chromodorolide B (1) was completed in 21 steps and 1.2% overall yield from commercially available enedione 15. An unprecedented photoredox radical cascade reaction allowed butenolide and trans-hydrindane fragments to be combined while forming two C–C bonds and stereoselectively creating three of the ten contiguous stereocenters of 1. As with almost all first total syntheses of a unique and structurally complex natural product, several aspects of the synthetic route can be improved upon. Towards this end, our current efforts focus on discovering the origins of diastereoselectivity of both Csp3–Csp3 bond-forming steps in the radical cascade and improving the diastereoselectivity of the 5-exo cyclization step.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the the National Institute of General Medical Sciences by research grant R01GM098601 and a graduate fellowship award to YS (1F31GM113494). NMR and mass spectra were determined at UC Irvine using instruments purchased with the assistance of NSF and NIH shared instrumentation grants. We thank Greg Lackner and Dr. Gerald Pratsch for helpful discussions. We thank Professor Mary J. Garson, the University of Queensland, for the high-field NMR spectra of natural chromodorolide B.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:XX.

References

- 1.Chromodorolide A:; (a) Dumdei EJ, De Silva ED, Andersen RJ, Choudhary MI, Clardy J. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:2712–2713. [Google Scholar]; Chromodorolide B:; (b) Morris SA, Dilip de Silva E, Andersen RJ. Can J Chem. 1991;69:768–771. [Google Scholar]; Chromodorolide C:; (c) Rungprom W, Chavasiri W, Kokpol U, Kotze A, Garson MJ. Mar Drugs. 2004;2:101–107. [Google Scholar]; Chromodorolides D and E:; (d) Katavic PL, Jumaryatno P, Hooper JNA, Blanchfield JT, Garson MJ. Aust J Chem. 2012;65:531–538. [Google Scholar]; Chromodorolide D:; (e) Uddin MH, Hossain MK, Nigar M, Roy MC, Tanaka J. Chem Nat Compd. 2012;48:412–415. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For reviews of rearranged spongian diterpenes, see:; (a) Keyzers RA, Northcote PT, Davies-Coleman MT. Nat Prod Rep. 2006;23:321–334. doi: 10.1039/b503531g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gonzalez M. Cur Bioact Comp. 2007;3:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Total syntheses of norissolide:; (a) Brady TP, Kim SH, Wen K, Theodorakis EA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:739–742. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brady TP, Kim SH, Wen K, Kim C, Theodorakis EA. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:7175–7190. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Granger K, Snapper ML. Eur J Org Chem. 2012:2308–2311. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isolation:; Rudi A, Kashman Y. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:4019–4022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Total syntheses of aplyviolene:; (a) Schnermann MJ, Overman LE. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16425–16427. doi: 10.1021/ja208018s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schnermann MJ, Overman LE. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:9576–9570. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Effect on Golgi structure:; (c) Schnermann MJ, Beaudry C, Egorova AV, Polishchuk RS, Sütterlin C, Overman LE. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6158–6163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001421107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The cis-diol was incorporated from the outset because our early studies in this area revealed that the stereoselectivity of dihydroxylation of an alkene precursor could be problematic. See:; Wang H, Kohler P, Overman LE, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16054–16058. doi: 10.1021/ja3075538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Okada K, Okamoto K, Morita N, Okubo K, Oda M. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:9401–9402. [Google Scholar]; (b) Pratsch G, Lackner GL, Overman LE. J Org Chem. 2015;80:6025–6036. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Deen H, van Oeveren A, Kellogg RM, Feringa BL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:1755–1758. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Also plausible would be a radical-polar crossover pathway in which A/A’ is reduced to the butenolide enolate and cyclization occurs by an SN2′ pathway. For experimental evidence that α–acyl radicals formed from the coupling of carbon radicals–generated by the Okada method–and α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds can be reduced reduced under these conditions, see ref 7b.

- 10.Such selectivity is well precedented, see:; Lackner GL, Quasdorf KW, Overman LE. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:15342–15345. doi: 10.1021/ja408971t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For reactions of 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolane trisubstituted radicals, see:; (a) Gerster M, Renauld P. Synthesis. 1997:1261–1267. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamada K, Yamamoto Y, Maekawa M, Tomioka K. J Org Chem. 2004;69:1531–1534. doi: 10.1021/jo035496s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For reactions of 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-dioxolane disubstituted radicals, see:; (c) Barton DHR, Gateau-Olesker A, Géro SD, Lacher B, Tachdjian C, Zard SZ. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:4589–4602. [Google Scholar]

- 12.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 13.Alvarez-Manzaneda E, Chahboun R, Barranco I, Cabrera E, Alvarez E, Lara A, Alvarez-Manzaneda R, Hmamouchi M, Es-Samti H. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:11943–11951. [Google Scholar]; (b) Paquette LA, Wang H-L. J Org Chem. 1996;61:5352–5357. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eder U, Sauer G, Wiechert R. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1971;10:496–497. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shigehisa H, Mizutani T, Tosaki S-Y, Ohshima T, Shibasaki M. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:5057–5065. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandai T, Matsumoto T, Kawada M, Tsuji J. J Org Chem. 1992;57:1326–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Miyano S, Yamashita J, Hashimoto H. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1972;45:1946. [Google Scholar]; (b) Denmark SE, Edwards JP. J Org Chem. 1991;56:6974–6981. [Google Scholar]

- 18.For reviews, see:; (a) Fürstner A. Chem Rev. 1999;99:991–1046. doi: 10.1021/cr9703360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wessjohann LA, Scheid G. Synthesis. 1999:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan Z-K, Choi HW, Kang F-A, Nakajima K, Demeke D, Kishi Y. Org Lett. 2002;4:4431–4434. doi: 10.1021/ol0269805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Choi HW, Nakajima K, Demeke D, Kang F-A, Jun H-S, Wan Z-K, Kishi Y. Org Lett. 2002;4:4435–4438. doi: 10.1021/ol026981x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.X-ray coordinates were deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre: a) 23: 1446028, b) 24: 1446026, and c) 1: 1446027.

- 21.Ireland RE, Wrigley TI, Young WG. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:4604–4606. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Generation of the dioxolane radical from the corresponding carboxylic acid was also successful.23 However, this acid proved more difficult to purify than the crystalline N-acyloxypthalamide 24.

- 23.Chu L, Ohta C, Zuo Z, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10886–10889. doi: 10.1021/ja505964r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.We have thus far failed to isolate this product in pure form.

- 25.This result may arise from coordination of DIBALH to the benzyl ether, e.g., see:; Jung ME, Usui Y, Vu CT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:5977–5980. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.