Abstract

Rubisco activase (RCA), a key photosynthetic protein, catalyses the activation of Rubisco and thus plays an important role in photosynthesis. Although the RCA gene has been characterized in a variety of species, the molecular mechanism regulating its transcription remains unclear. Our previous studies on RCA gene expression in soybean suggested that expression of this gene is regulated by trans-acting factors. In the present study, we verified activity of the GmRCAα promoter in both soybean and Arabidopsis and used a yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) system for screening a leaf cDNA expression library to identify transcription factors (TFs) interacting with the GmRCAα promoter. Four basic leucine zipper (bZIP) TFs, GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, GmbZIP1, and GmbZIP71, were isolated, and GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g were confirmed as able to bind to a 21-nt G-box-containing sequence. Additionally, the expression patterns of GmbZIP04g, GmbZIp07g, and GmRCAα were analyzed in response to abiotic stresses and during a 24-h period. Our study will help to advance elucidation of the network regulating GmRCAα transcription.

Keywords: Rubisco activase, promoter, basic leucine zipper, soybean, transcription factor

Introduction

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), an abundant and important enzyme in plants, catalyses the photosynthetic assimilation of atmospheric CO2 and photorespiratory carbon oxidation (Spreitzer and Salvucci, 2002). In higher plants, Rubisco is a hexadecameric complex composed of eight large (RbcL) and eight small subunits (RbcS), and its activity in vivo is known to be regulated by different mechanisms (Stec, 2012). Previous studies have shown that the activation and maintenance of Rubisco catalytic activity require the continued action of Rubisco activase (RCA), an ATPase associated with a variety of cellular activities (AAA+) protein (Andrews et al., 1995; Portis, 2003). RCA is a nuclear-encoded chloroplast protein that functions as a molecular chaperone and activates Rubisco by removing various inhibitory sugar phosphates in an ATP-dependent reaction (Portis, 1990; Dejimenez et al., 1995). In addition, the expression level of RCA mRNA has been correlated with Rubisco activity, photosynthetic rates, seed/grain yield, and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, suggesting its potential applicability in breeding for enhancing soybean productivity (Yin et al., 2010, 2014; Chao et al., 2014).

In higher plants, the RCA gene is mainly expressed in photosynthetic tissues and is developmentally regulated by both light and leaf age (Watillon et al., 1993; Jiang et al., 2013; Bayramov and Guliyev, 2014; Chao et al., 2014). Levels of RCA mRNA exhibit cyclic variations during the day/night period in tomato (Martinocatt and Ort, 1992), apple (Watillon et al., 1993), rice (To et al., 1999), potato (Jiang et al., 2013), soybean (Chao et al., 2014), maize (Yin et al., 2014), and Arabidopsis (Liu et al., 1996). Moreover, RCA expression at the mRNA and protein levels is reported to be affected by a variety factors, including abiotic stress such as ozone (Pelloux et al., 2001; Demirevska-Kepova et al., 2005), drought (Pelloux et al., 2001; Bota et al., 2004; Ji et al., 2012), UV-B light (Liu et al., 2002), heat (Demirevska-Kepova et al., 2005; DeRidder and Salvucci, 2007; Scafaro et al., 2010), and NaCl (Bayramov and Guliyev, 2014). It has been reported that the RCA protein can also be regulated by Manduca sexta (a specialist herbivore of Nicotiana attenuata) attack and that RCA has a function in regulating JA signaling (Giri et al., 2006; Walia et al., 2007; Mitra and Baldwin, 2008, 2014; Shan et al., 2011; Attaran et al., 2014). RCA is also regulated in response to ABA treatment (Fukayama et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2010).

Gene expression is regulated both quantitatively and qualitatively by specific sequences upstream of a gene’s coding region, commonly known as the promoter, which contains multiple cis-regulatory elements (Mitsuhara et al., 1996). Indeed, interaction between cis-elements and transcription factors (TFs) has a critical role in regulating transcription via the coordinated activation or repression of the target (Ptashne, 2005; Wehner et al., 2011). Although the RCA gene has been characterized in a number of species, to date, its promoter has only been studied in spinach (Orozco and Ogren, 1993), Arabidopsis (Liu et al., 1996), potato (Qu et al., 2011), rice (Yang et al., 2012), and soybean (Chao et al., 2014), and the molecular mechanism by which the RCA promoter is regulated remains to be clarified. It has been shown in rice that nuclear proteins bind specifically to the RCA gene promoter (Yang et al., 2012). In soybean, previous studies have shown that expression of GmRCAβ is controlled by a combination of both cis-acting and trans-acting expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) (Chao et al., 2014), with GmRCAα gene expression being mainly regulated by trans-acting factors (Yin et al., 2010). However, little is known about the specific proteins interacting with the RCA promoter.

Most plants contain two closely related isoforms of RCA, an α-isoform of 46–48 kDa and a β-isoform of 41–43 kDa, though tobacco possesses only the β-isoform (Portis, 2003). The two isoforms differ by the presence of a carboxy-terminal extension containing redox-sensitive cysteine (Cys) residues in the former (Portis, 2003). Although both are capable of activating Rubisco (Zhang and Portis, 1999), expression of the isoforms often differs slightly. Previous studies in rice have shown that the expression level of mRNA encoding the α-isoform increases substantially after 24 h of heat treatment, whereas expression of the β-isoform declines (Scafaro et al., 2010) or is unaffected (Wang et al., 2010). This finding suggests differential regulation of the α-isoform gene, at least with regard to heat treatment. The soybean isoforms of RCA, GmRCAα, and GmRCAβ, are encoded by separate genes, and bioinformatics analysis of their promoters has revealed a heat shock element in the former that is not present in the latter (Chao et al., 2014). In the present study, the expression pattern of the GmRCAα promoter was analyzed in soybean and Arabidopsis. While investigating the network regulating GmRCAα expression, we identified two TFs, GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g, that bind to the promoter region. These results might help us better understand the complicated regulatory network of the soybean RCA gene, GmRCAα.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Plant Growth Conditions

Soybean cultivar Kefeng No. 1 was used in all experiments in this study, including promoter analysis, gene cloning and gene expression analysis. The seeds of this cultivar were provided by Soybean Research Institute, Nanjing Agricultural University, China, and grown under natural conditions in the field at Jiangpu Experimental Station, Nanjing Agricultural University. At the R2 stage, the mature upper third of leaves were sampled at different times (0:00, 6:00, 12:00, and 18:00) to determine GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, and GmRCAα gene expression levels during a single day.

Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0) was used as the wild type. Sterilized seeds were incubated on MS medium at 4°C for 3 days before being transferred to a growth chamber (25°C/22°C, 300 μmol photons m-2 s-1, 70% relative air humidity and 12-h/12-h light/dark).

Hormone and Abiotic Treatments

Soybean seeds were germinated in plugs containing a mixture of peat and vermiculite (3:1, v/v), and once the cotyledons were fully expanded, the soybean seedlings were selected and pre-cultured in one-half-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution for 3 days. The uniformly grown seedlings were washed and transferred to different abiotic conditions. PEG treatment was carried out by transferring seedlings to water supplemented with 15% PEG, and leaves were sampled after 0.5 and 2 h. For ABA and high-salt treatments, seedlings were transferred to water supplemented with 250 mM NaCl and 100 μM ABA solutions, respectively. Control seedlings were submerged in water, and leaves were sampled at 0, 0.5, 2, 3, and 6 h. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further use for RNA extraction.

RNA Preparation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from soybean leaf with an RNA Plant Extraction Kit (Tiangen, China), and approximately 2 μg of purified total RNA was reverse transcribed using AMV reverse transcriptase (Takara) according to the supplier’s instructions. RT-PCR was performed as described previously (Yin et al., 2010). The primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The soybean endogenous reference gene tubulin (GenBank: AY907703.1) was used as a control, and three technical replicates were performed.

Y1H Assay

A soybean cDNA library was constructed from RNAs of the mature upper-third leaves at the full-seed stage (R6 stage) using CloneMiner II cDNA Library Construction Kit (Invitrogen). The cDNA library was then cloned into pGADT7-Rec2-DEST to generate the library for Y1H screening.

DNA fragments of the GmRCAα promoter and the pG-box and pmG-box were cloned into the pAbAi vector, then linearized by BstBI digestion, and transformed into Y1HGold to generate reporter strains. The pGmRCAα strain was then transformed with the library. For the Y1H assay, positive colonies were selected on yeast Leu dropout medium supplemented with 250 ng/mL AbA (Clontech). To reconfirm the Y1H screening results, the full-length coding sequence of putative candidates (GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g) was cloned into pGADT7, and Y1H assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plasmid Construction and Plant Transformation

To generate constructs to examine the expression patterns of GmRCAα, PCR was performed using KOD polymerase (Toyobo, Japan) and the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1, the amplifications were then digested with BamHI/PstI. As a reporter, the fragments were fused with the GUS gene in the binary vector pCAMBIA1381z (Cambia, Australia); four constructs, GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS, GmRCAαpro(–889)::GUS, GmRCAαpro(–157)::GUS and pCAMBIA1381z were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 using the freeze-thaw method and then transformed into Arabidopsis using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). T1 seeds were collected and selected on MS medium containing 25 mg/mL hygromycin (hyg) and then tested by amplification of a 457-bp fragment using primer pairs targeting the promoter and GUS sequences. T3 and T4 homozygous lines were used for further study. The GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS construct was transformed into soybean cotyledonary nodes, and the transformation was performed following a previously described method (Zhang et al., 1999).

Promoter Transactivation Assays Using Arabidopsis Mesophyll Protoplasts

To generate firefly luciferase reporter construct, a 2205-bp sequence upstream of GmRCAα was PCR amplified using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1, digested with BamHI and NcoI, and then cloned into pRD29A-LUC (EF090409) to replace the RD29A promoter in the vector. To prepare effector TFs, the entire coding region of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g, without the stop codon TAG, were amplified by PCR. Both of the fragments were digested with BamHI and ligated to the same digested HBT95::sGFP(S65T)-NOS vector. The pPTRL (Renilla reniformis Luciferase driven by 35S promoter) was used as internal control (Fang et al., 2015).

Arabidopsis protoplasts were isolated and transformed according to the method described by Wang et al. (2015). The effector, reporter and internal control were co-transformed into Arabidopsis protoplasts with 10, 5, and 0.5 μg, respectively. The protoplasts were incubated under weak light for 12–16 h before harvesting. Dual luciferase assay was performed with a Dual-luciferase assay system kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the transformed protoplasts were centrifuged at 12000 × g for 15 s at room temperature, and the supernatant was removed. Then add 100 μl of the Passive Lysis Buffer with further homogenization. Twenty microliters of the lysate was mixed with 100 μl of LAR II, and the firefly luciferase (LUC) activity was measured using a GloMax 20/20 luminometer (Promega). Then 100 μl of Stop & Glo Reagent was added to the reaction, and the Renilla luciferase (REN) activity was measured. Four repeats were performed. Differences were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, with post hoc analysis using SPSS16.0. ∗∗ denotes significant difference at P = 0.01.

Subcellular Localization

The same effector TF constructs were used to investigate GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g localization. Arabidopsis protoplasts were isolated and transformed as promoter transactivation assays. The protoplasts were incubated under weak light for 12 to 16 h and observed with an LSM 780 Exciter confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss). The excitation wavelength used for GFP was 488 nm.

Histochemical GUS Staining and Activity Assay

Transgenic Arabidopsis expressing GUS expression constructs were collected at several growth stages and subjected to GUS staining. GUS staining in both transgenic Arabidopsis and soybean cotyledonary nodes was performed as described previously, with some modification (Chao et al., 2014). Plant samples were soaked at 37°C for 12 h in the GUS assay solution which included 0.5 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl glucuronide, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM K3[Fe(CN)6], 1 mM K4[Fe(CN)6], 10 mM EDTA and 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) in darkness. The staining solution was then replaced by 75% ethanol to remove chlorophyll. Ethanol washing was repeated 3–5 times for 6 h. Then GUS staining was observed with an Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope and photographed with a digital camera (CoolSNAP, RS photometrics). For transgenic Arabidopsis plants, quantitative analysis of GUS activity was detected according to the method of Jefferson et al. (1987).

Transactivation Activity Assay in Yeast

The transactivation activity assay was performed using the Matchmaker Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System (Clontech, USA). To construct BD-GmbZIP04g and BD-GmbZIP07g, the full-length coding sequence of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g was amplified by PCR and then fused into pGBKT7 vector, using the same primer pairs with that of pGADT7 constructs (Supplementary Table S1). Combinations of BD-GmbZIP04g and AD, BD-GmbZIP07g and AD, positive and negative control vectors were transformed into yeast strain AH109, respectively. The transformed yeasts were grown on SD/-Trp/-Leu/X-α-gal (DDO/X) and SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade/X-α-gal (QDO/X) agar plates. After 3 days growth in dark, the plates were photographed.

Results

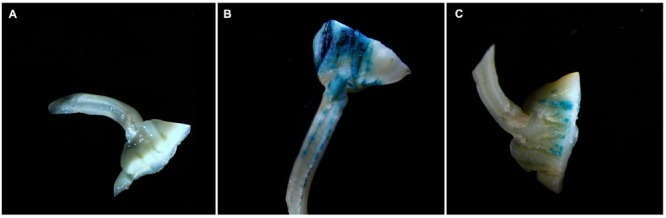

GUS Expression Driven by the GmRCAα Promoter in Soybean Cotyledonary Nodes

To determine whether the promoter sequence of the GmRCAα gene is able to activate GUS expression, we carried out a transient assay by cloning a 2205-bp promoter fragment of GmRCAα, referred to as GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS, upstream of the GUS reporter gene. Subsequent staining results indicated that GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS can drive GUS expression in soybean cotyledonary nodes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Histochemical staining of soybean cotyledonary nodes driven by the promoter sequence of GmRCAα. (A) Negative control pCAMBIA1381z; (B) positive control pCAMBIA1301; (C) GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS.

Expression Patterns and Deletion Analysis of the GmRCAα Promoter in Arabidopsis

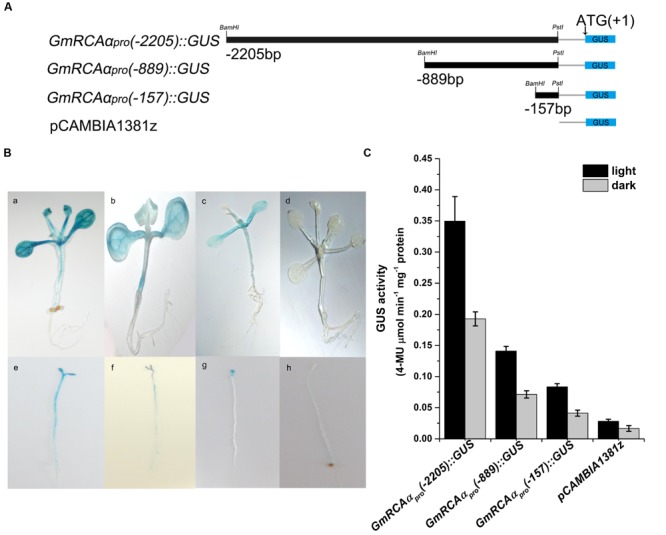

To analyze the function of the GmRCAα promoter, two deletion mutants were fused with the GUS reporter gene [named GmRCAαpro(–889)::GUS and GmRCAαpro(–157)::GUS] (Figure 2A) and transformed into Arabidopsis, as was GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS.

FIGURE 2.

GUS activity in transgenic Arabidopsis. (A) The diagram shows GmRCAα promoter 5′ terminal deletion mutant constructs fused with the reporter gene GUS. (B) Histochemical staining of transgenic Arabidopsis. (a–d) Green seedlings grown under a 12-h/12-h light/dark photoperiod; (e–h) etiolated seedlings grown in the dark. a and e, b and f, c and g, and d and h represent transgenic seedlings expressing GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS, GmRCAαpro(–889)::GUS, GmRCAαpro(–157)::GUS and pCAMBIA1381z, respectively. (C) GUS activity assay of the green and etiolated seedlings indicated in (B). Error bars represent SE (n = 3). 4-MU, 4-methylumbelliferone.

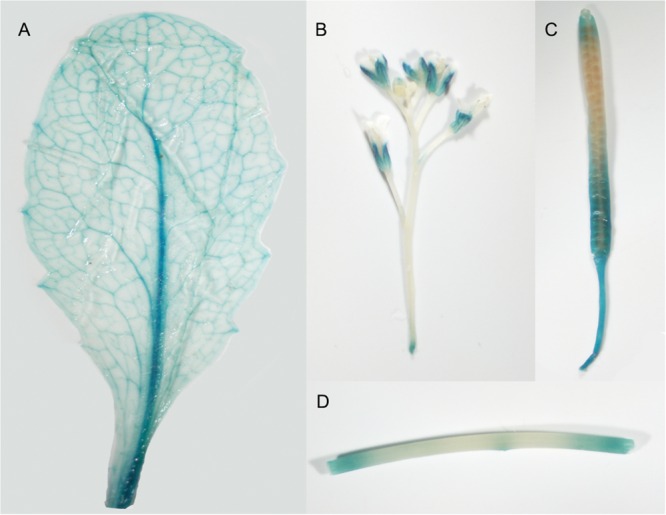

β-Glucuronidase staining revealed a detailed temporal and spatial expression pattern for GmRCAαpro(–2205) ::GUS. In young seedlings, staining was observed mainly in green tissues, including cotyledons, true leaves and hypocotyls, but not in roots (Figure 2B), whereas in mature plants, GUS activity was found in leaves, particularly in vascular tissues, stems, green siliques and flower sepals (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

GUS staining for GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS activity in transgenic Arabidopsis. (A) A mature leaf from a 2-week-old seedling; (B) flowers; (C) mature silique; (D) stem.

β-Glucuronidase staining of 7-day-old green seedlings grown under a 12-h/12-h light/dark photoperiod showed that GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS, GmRCAαpro(–889)::GUS and GmRCAαpro(–157)::GUS were all able to drive GUS expression (Figure 2B), with expression driven by GmRCAαpro(–2205)::GUS being stronger than that by GmRCAαpro(–889)::GUS and staining for GmRCAαpro(–889)::GUS being stronger than that for GmRCAαpro(–157)::GUS (Figure 2C). Etiolated dark-grown seedlings showed similar staining. These results indicated that positive regulatory elements may be located in the regions extending from -2205 to -889 and from -889 to -157.

Identification of bZIP TFs Interacting with the GmRCAα Promoter

To identify putative TFs regulating GmRCAα expression, a Y1H assay was carried out to identify proteins interacting with the GmRCAα promoter. A 2205-bp fragment upstream the ATG start codon of GmRCAα was initially used as bait, but 500 ng/mL AbA did not suppress basal expression in the reporter strain. Then, a 1459-bp GmRCAα promoter was isolated and applied for screening a soybean cDNA library. Among the positive clones (Supplementary Table S2), four TFs belonging to the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family appeared 17 times during screening and were thus analyzed further. The corresponding gene names are Glyma04g04170, Glyma06g04353 (GmbZIP71) (Liao et al., 2008), Glyma07g33600, and Glyma02g14880 (GmbZIP1) (Gao et al., 2011), which we refer to herein as GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP71, GmbZIP07g, and GmbZIP1.

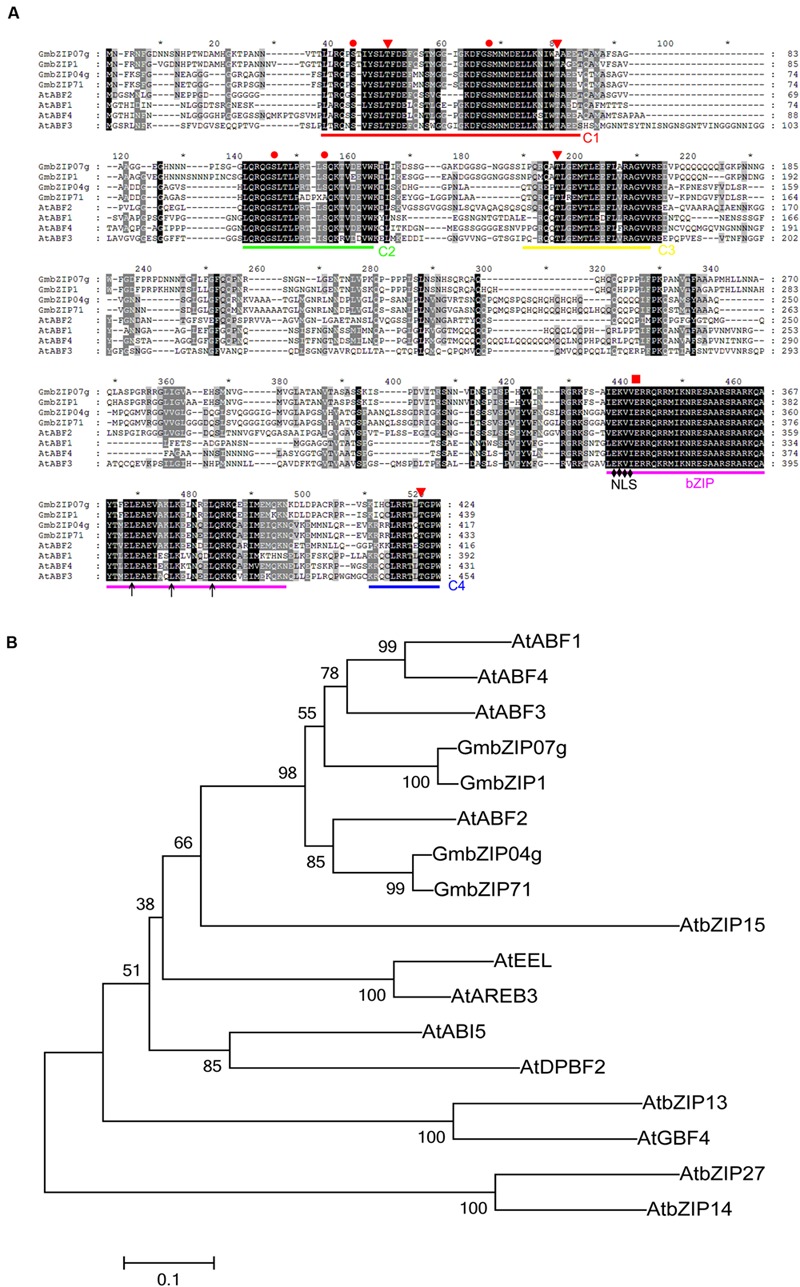

Multiple alignments for GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP71, GmbZIP07g, GmbZIP1, and four other ABF proteins of Arabidopsis thaliana revealed high sequence identity. As shown in Figure 4A, these four proteins possess a conserved bZIP domain at the C-terminus, a putative nuclear localization signal (NLS) and four additional conserved domains, three at the N-terminal half (C1, C2, and C3) and one at the C-terminal end (C4) (Fujita et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2011). Based on the characteristics of the conserved domains, we assigned these four bZIP proteins of soybean to the ABF subgroup of the bZIP family. A phylogenetic tree constructed using amino acid sequences of GmABFs (GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP71, GmbZIP07g, and GmbZIP1) and bZIP groupA proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana (Jakoby et al., 2002) presented that GmABFs are most closely related to AtABF1-4 proteins (Figure 4B), with GmbZIP1 having high similarity to GmbZIP07g (86.00%) and GmbZIP71 sharing 87.76% similarity with GmbZIP04g.

FIGURE 4.

Amino acid sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of GmABFs. (A) Sequence alignment of GmABFs and AtABFs. The alignment was generated using CLUSTALX (version 1.83) and viewed using the GeneDOC program (version 2.6.0.2). The basic region and the three heptad leucine repeats, three important bZIP signatures, are shown as purple line and arrows, respectively. C1, C2, C3, and C4 are conserved regions containing serine (●) and threonine (▼) residues. The NLS, the putative nuclear localization signal, is indicated by a black diamond. The red square indicates the boundary between the N- and C-terminal of GmbZIP07g. ∗ indicates that this position is an odd multiple of 10. (B) Phylogenetic tree of GmABFs and Arabidopsis thaliana bZIP group A proteins using MEGA6.06. The protein sequences were obtained from Phytozome (http://www.phytozome.net/) and The Arabidopsis Information Resource (http://www.arabidopsis.org/).

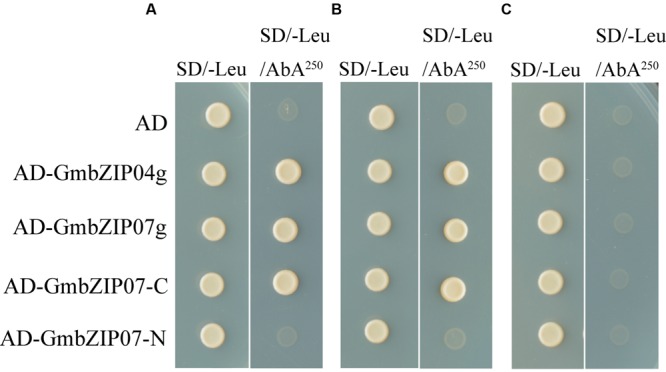

Based on the phylogenetic relationship, we verified whether two of these bZIP TFs, GmbZIP04g, and GmbZIP07g, are able to bind the GmRCAα promoter using the full-length ORF in a second Y1H assay (Figure 5A). Y1H assays were also conducted to identify which TF region is responsible for binding to the GmRCAα promoter. Given the sequence similarity (44.42%) between GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g and their highly conserved domains, GmbZIP07g was selected for further analyses. Two fragments of GmbZIP07g were generated based on the bZIP domain of bZIP family proteins; the corresponding constructs were named GmbZIP07-N(1-345AA) and GmbZIP07-C(346-430AA). Deletion of the C-terminal 84 amino acids of GmbZIP07g resulted in a lack of binding to the GmRCAα promoter (Figure 5A). Thus, GmbZIP07g possesses binding activity, and this activity resides within the C-terminal region.

FIGURE 5.

Identification of proteins interacting with pGmRCAα, pG-box, and pmG-box reporter strains by a Y1H assay. The promoter of GmRCAα, G-box sequence, and mutated G-box were cloned upstream of the AbA resistance (AbAr) gene and integrated into Y1HGold to generate reporter strains. The reporter strains were transformed with the effector transcription factors (TFs) indicated on the left, and growth was recorded for 3 days at 30°C in the absence or presence of 250 ng/mL AbA. (A) pGmRCAα reporter strain. (B) pG-box reporter strain. (C) pmG-box reporter strain.

GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g Interact with a Specific Sequence in the GmRCAα Promoter

Numerous bZIP proteins have been reported as interacting with the ABRE or G-box (CACGTG) (Huang et al., 2010; Dai et al., 2013). According to a bioinformatics analysis of the GmRCAα promoter, only one conserved ABRE/G-box (CACGTG) is present in the 1459-bp fragment. Therefore, we examined whether GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g bind to a 21-nt G-box/ABRE-containing sequence.

Both this G-box containing sequence (pG-box, AGTTGC CACGTGGCAGCCAAG, G-box core sequence was underlined) and a mutated G-box sequence (pmG-box, AGTTGC AACGACGCAGCCAAG, mutant sequence of the G-box is underlined) were prepared as reporter strains, and DNA-binding activity was determined using a Y1H assay. Figures 5B,C shows that the clones harboring GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, and GmbZIP07-C grew well on SD/-Leu/AbA250 medium with the pG-box reporter strain, whereas GmbZIP07-N and the negative control (empty pGADT7 AD vector) did not grow. Thus, GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g specifically bound the G-box/ABRE-containing sequence through the C-terminus of GmbZIP07g. Furthermore, no clones grew with the pmG-box reporter strain, indicating that the CACGTG motif is essential for DNA binding.

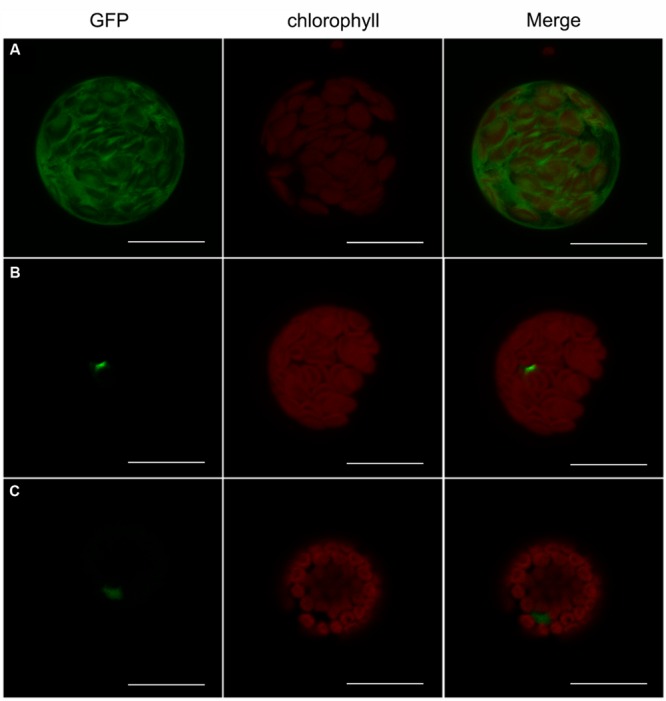

GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g Are Localized in the Nucleus and Exhibit Transactivation Activity in Yeast

GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g are TFs, and both have a nuclear localization signal near the C terminus, suggesting that they may be localized to the nucleus. To determine the intracellular localization of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g, we transiently transformed GmbZIP04g-sGFP and GmbZIP07g-sGFP into Arabidopsis protoplasts and found GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g in the nucleus (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Nuclear localization of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g in Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts. Confocal laser scanning microscope images of leaf protoplasts transiently expressing (A) HBT95::sGFP(S65T)-NOS, (B) GmbZIP04g-sGFP, and (C) GmbZIP07g-sGFP. Column 1, GPF signal (green); column 2, chlorophyll autofluorescence (red); column 3, merged GFP and chlorophyll signals. Scale bars represent 20 μm.

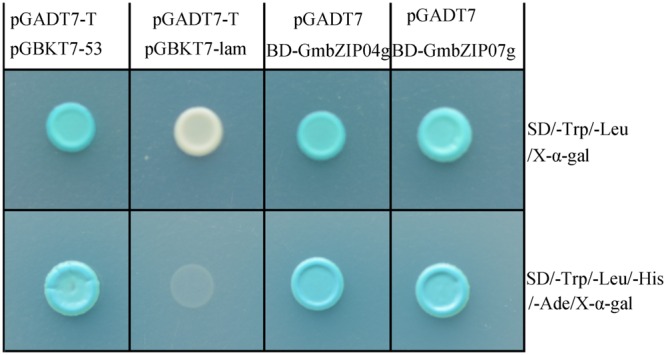

To evaluate whether GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g are able to activate transcription, full-length GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g were fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (GAL4-BD) in the pGBKT7 vector. The constructs were co-transformed into yeast strain AH109 with pGADT7, then screened on DDO/X and QDO/X media. By X-α-Gal assay, the GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g yeast clones were weak blue in colour (Figure 7), indicating that GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g possess transactivation activity in yeast.

FIGURE 7.

Transactivation assay of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g in the yeast strain AH109. Positive control (pGADT7-T and pGBKT7-53); Negative control (pGADT7-T and pGBKT7-lam); BD-GmbZIP04g and pGADT7; BD-GmbZIP07g and pGADT7. The SD/-Trp/-Leu/X-α-Gal (DDO/X, Upper) and SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade/X-α-Gal (QDO/X, Lower) plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days and then visualized.

Expression Patterns of GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, and GmRCAα

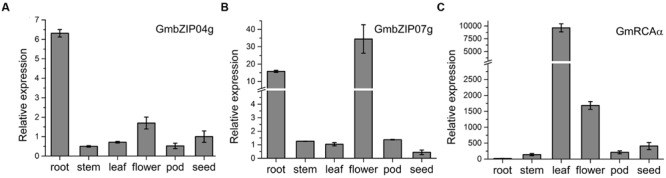

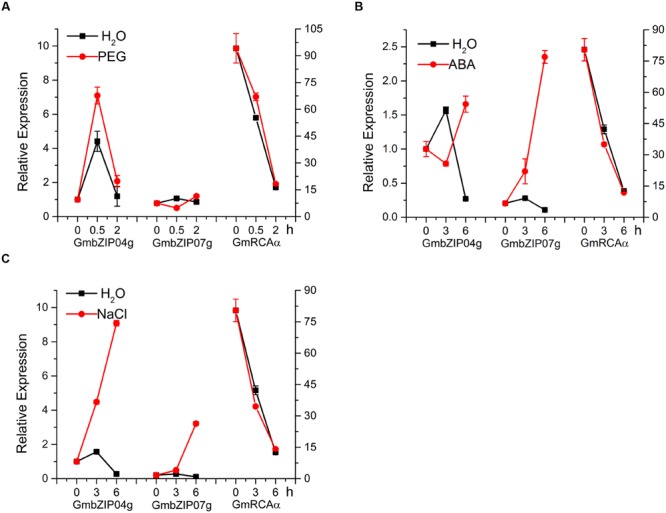

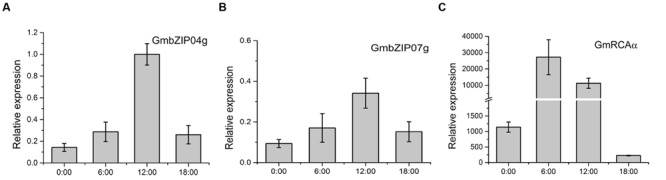

Tissue analysis of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g revealed expression in root, stem, flower, leaf, and seed (Figures 8A,B); as GmRCAα was mainly expressed in leaf (Figure 8C), we chose this tissue for further study. The expression of GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, and GmRCAα was analyzed in plants subjected to PEG, ABA, and NaCl stresses. As shown in Figures 9A–C, GmRCAα exhibited a slight change at 3 h and was almost the same as the control at 6 h under all these treatments. After PEG treatment, the expression of GmbZIP04g was higher than that in the control, and GmbZIP07g showed a lower expression at 0.5 h followed a higher level at 2 h compared to the control. The transcript level of GmbZIP04g was lower than that in the control at 3 h but was significantly higher at 6 h when subjected to ABA treatment. With ABA and NaCl treatments, continuous accumulation of GmbZIP07g transcript was observed at 3 and 6 h, and a similar pattern for GmbZIP04g was observed in response to NaCl treatment. The upper-third leaves of soybean were sampled at 6-h intervals for 24 h, and RT-PCR assays were then performed. The results showed that the transcripts of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g increased from 0:00 to 12:00, reaching a peak at noon and then decreasing, whereas the maximal level of GmRCAα was detected at 6:00 (Figures 10A–C). Our results suggest that GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, and GmRCAα may be regulated in response to abiotic stresses and light.

FIGURE 8.

Tissue-specific expression of GmbZIP04g(A), GmbZIP07g(B), and GmRCAα (C). Transcript expression levels were measured by RT-PCR. Total RNA was isolated from soybean roots, stems and leaves harvested at the seedling stage, from flowers harvested at the R2 stage (flowering) and from seeds harvested at the R6 stage (full seed). Tubulin was used as an internal control, and error bars represent the standard error of three independent repetitions.

FIGURE 9.

Time-course expression analysis of GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, and GmRCAα. (A–C) Soybean seedlings were exposed to PEG (15%), NaCl (250 mM), ABA (100 μM), and water treatments. GmbZIP04g expression under water treatment at 0 h was used as the reference for the basal expression level. The left y-axis indicates the relative expression level of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g, and the right y-axis represents the expression of GmRCAα. Tubulin was used as an internal control. Error bars represent the SE (n = 3).

FIGURE 10.

Diurnal pattern of GmbZIP04g(A), GmbZIP07g(B), and GmRCAα (C) mRNA accumulation in soybean leaves. Total RNA was extracted at 0:00, 6:00, 12:00, and 18:00 from the upper-third leaves of soybean plants at the R2 stage. Tubulin was used as an internal control, and error bars represent the SE (n = 3).

Discussion

The genes encoding two RCA isoforms, GmRCAα and GmRCAβ, have been previously characterized (Yin et al., 2010). In addition, the levels of GmRCAα and GmRCAβ gene expression have been positively correlated with Rubisco initial activity, PN, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters and seed yield, indicating that RCA genes may play important roles in regulating soybean photosynthetic capacity and enhancing soybean productivity (Yin et al., 2010; Chao et al., 2014). Here, we report the expression patterns of GmRCAα by examining the activity of its promoter. The GmRCAα promoter was able to drive GUS expression in soybean cotyledonary nodes (Figure 1), and GUS staining in Arabidopsis revealed expression mainly in green tissues (Figure 2), which is similar to that of Arabidopsis and rice RCA genes (Liu et al., 1996; Yang et al., 2012). We also found that a 157-bp fragment upstream of the ATG to be sufficient for tissue-specific expression in transgenic Arabidopsis. Minimal promoters conferring RCA gene expression in Arabidopsis, rice, and spinach were previously identified within 317 bp, 297 bp, and 294 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site (Orozco and Ogren, 1993; Liu et al., 1996; Yang et al., 2012). These results suggest that basal and/or important elements are located proximal to the 5′-untranslated region in both dicots and monocots.

Although numerous studies have shown that RCA gene and/or protein expression is affected by various factors, such as biotic (Mitra and Baldwin, 2014) and abiotic (Ji et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2015) stresses, there are no reports to date on the direct transcriptional regulation of RCA. Regulatory TFs activate or repress transcription of their target genes by binding to cis-elements, which are frequently located in a gene’s promoter. In this study, Y1H screening was performed to investigate the upstream regulators of GmRCAα. We isolated and identified four bZIP proteins, GmbZIP1, GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP71, and GmbZIP07g, as interacting with the promoter sequence of GmRCAα (Figure 5). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of interaction between the RCA promoter and a TF. Furthermore, we found that it is the C-terminal conserved bZIP domain of GmbZIP07g, but not the N-terminus, that interacts with the GmRCAα promoter (Figure 5). This result suggests that the C-terminal of GmbZIP07g may play a crucial role in downstream promoter elements binding.

Expression QTL analysis can provide tremendous insight into the biology of gene regulation, indeed, measurements of gene expression of a population helps us to learn which types of SNPs are most likely to affect gene regulation (Gilad et al., 2008). Biological processes are complex networks of physical interactions between various molecules, and one type of interaction occurs between TFs and their target DNA sites, generally cis-elements in the promoter of a gene, to up-regulate or down-regulate expression. The Y1H assay used in this study is one method for detecting protein–DNA interaction (Reece-Hoyes and Marian Walhout, 2012). However, GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, GmbZIP1, and GmbZIP71 were not detected by eQTLs in our previous study (Yin et al., 2010; Chao et al., 2014); possible explanations for this might be the lower marker density (Zhao et al., 2011), a statistical reason that many distal eQTLs are missed (Gilad et al., 2008), and non-genetic factors such as environmental variation.

Plant bZIP family members regulate various processes, such as pathogen defense, light and abiotic stress signaling, hormone signaling, energy metabolism, and development, including flowering and seedling maturation (Jakoby et al., 2002; Llorca et al., 2014). Among light-regulated bZIP proteins in Arabidopsis (Jakoby et al., 2002) and rice (Nijhawan et al., 2008), AtHY5 has been well documented as a critical regulator of photomorphogenesis (Chen et al., 2008). The conserved sequence motif CACGTG, generally known as the G-box or “ABA-responsive” element (ABRE), is present in the promoter regions of many light-regulated genes (Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000; Jiao et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2014). Numerous bZIP class proteins have been isolated, and experiments have shown that these factors can interact with the ABRE or G-box both in vivo and in vitro (Huang et al., 2010; Dai et al., 2013). Previous studies have reported that many bZIP proteins bind to a G-box/ABRE element, which contains an ACGT core motif. For example, AtABF proteins 1–4 were isolated by a Y1H system using a prototypical ABRE, the Em1a element (GGACACGTGGCG) (Choi et al., 2000). In the present study, we also found that GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g and the C-terminus of GmbZIP07g interact with a 21-nt DNA sequence containing the G-box/ABRE element (Figure 5) using a Y1H assay, suggesting that GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g might directly regulate the expression of GmRCAα through this region. The bZIP TFs GmbZIP04g, and GmbZIP07g are localized in the nucleus and exhibit transactivation activity in yeast cells (Figures 6 and 7), in agreement with their homologs, such as AtABF2 and AtABF4 (Uno et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 2010).

All of GmRCAα, GmbZIP04g, and GmbZIP07g are expressed in leaf (Figures 8A–C), suggesting a functional role in this tissue. GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g revealed a higher expression in root, while the expression of GmRCAα in root was almost undetectable, we suppose that GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g may have other interacting promoters in addition to that of GmRCAα. And a possible explanation for low expression of GmRCAα in root may be due to the function of its unknown repressors. As the ABRE is involved in abiotic stresses (Choi et al., 2000; Gao et al., 2011), it would be interesting to investigate the involvement of GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, and GmRCAα in abiotic stresses in soybean. The levels of GmbZIP04g, GmbZIP07g, and GmRCAα transcripts were examined in soybean seedlings upon abiotic stresses, and RT-PCR analysis showed that expression of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g was highly induced after ABA and NaCl treatments, whereas the transcriptional levels of GmRCAα appeared to be unchanged (Figure 9). GmRCAα mRNA expression only showed a slight change after PEG and ABA treatments. One possible explanation for the lack of an immediate effect on the transcriptional levels of GmRCAα with GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g induction may due to competition with other TFs that activate or repress the expression of GmRCAα. In addition, ABFs are extensively regulated at the post-transcriptional level (Fujita et al., 2013), and as a result, an increase in transcript levels may not always correlate directly with an increase in protein levels. Furthermore, ABFs or AREBs in Arabidopsis were shown to interact with other proteins, form homo- and/or heterodimers (Kim et al., 2004a; Choi et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2010; Yoshida et al., 2010), suggesting a potential mechanism for generating diversity in these protein regulation networks. Such interaction between the two GmbZIP proteins may be examined in the future. As RCA diurnally regulated in higher plants (Chao et al., 2014; Yin et al., 2014), we examined the expression levels of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g at different time points. Our RT-PCR analysis showed that GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g expression increased from midnight to noon, suggesting that these genes may have a diurnal expression pattern similar to that of GmRCAα, ABF3 (Seung et al., 2012) and GmbZIP1 (Marcolino-Gomes et al., 2014). However, the maximal transcript level of GmRCAα appeared at 6:00, earlier than GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g, both of which reached their peaks at 12:00; thus, we infer that other TFs may be involved in this process.

In higher plants, Arabidopsis protoplasts system was widely used to study the regulation between TFs and its binding promoter (Yi et al., 2010; Figueiredo et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015). A transient assay in Arabidopsis protoplasts was performed to investigate the effects of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g on GmRCAα promoter activity, and the LUC/REN values of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g were higher than that of the empty vector (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S3). Further studies with transgenic approaches will help to understand the precise functions of GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g on the expression of GmRCAα.

In recent years, cross-talk between light and ABA as well as sugar and ABA are being increasingly studied. The plant hormone ABA plays essential roles during many phases of the life cycle and adaptation to environmental stresses, such as stomatal closure in response to drought. It was reported that light and ABA signaling are integrated at the promoters of HY5 (Chen et al., 2008) and ABI5 (Xu et al., 2014), which are bZIP proteins, during seed germination and early seedling development. Carbohydrates are the end products of photosynthesis, and ABF proteins are also involved in sugar signaling (Kim et al., 2004b). In addition, ABA and sugar have been shown to suppress many photosynthetic genes, including RBCS and CAB (Rook et al., 2006), and bZIP TFs were found to mediate the effects of sugar signaling on gene expression and metabolite content (Hanson and Smeekens, 2009). Moreover, interaction between ABA and Rubisco was recently identified biochemically (Galka et al., 2015), and RCA is a type of chaperone that functions to promote and maintain the catalytic activity of Rubisco, which is a crucial photosynthesis protein (Portis, 2003). Our research identified two bZIP TFs, GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g, interacting with the soybean GmRCAα promoter in yeast. However, it remains largely unknown how these two TFs are involved in the regulation of GmRCAα gene expression in soybean. Further studies on the relationship between GmRCAα and the TFs, GmbZIP04g and GmbZIP07g, in soybean are necessary to fully elucidate the complex regulatory mechanism of GmRCAα expression and to help unravel the function of these proteins in the regulation of photosynthesis processes.

Author Contributions

DY, JZ, and MC conceived and designed the experiments. JZ, HD, HY, and YL performed the experiments. JZ, FH, HD, MC, and ZY wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- 4-MU

4-methylumbelliferone

- ABA

abscisic acid

- AbA

aureobasidin A

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GUS

β-glucuronidase

- RT-PCR

real-time PCR

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371644) and Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production (JCIC-MCP).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00628

References

- Andrews T. J., Hudson G. S., Mate C. J., Voncaemmerer S., Evans J. R., Arvidsson Y. B. C. (1995). Rubisco - the consequences of altering its expression and activation in transgenic plants. J. Exp. Bot. 46 1293–1300. 10.1093/jxb/46.special_issue.1293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attaran E., Major I. T., Cruz J. A., Rosa B. A., Koo A. J., Chen J., et al. (2014). Temporal dynamics of growth and photosynthesis suppression in response to jasmonate signaling. Plant Physiol. 165 1302–1314. 10.1104/pp.114.239004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayramov S., Guliyev N. (2014). Changes in Rubisco activase gene expression and polypeptide content in Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 81 61–66. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bota J., Medrano H., Flexas J. (2004). Is photosynthesis limited by decreased Rubisco activity and RuBP content under progressive water stress? New Phytol. 162 671–681. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao M., Yin Z., Hao D., Zhang J., Song H., Ning A., et al. (2014). Variation in Rubisco activase (RCAbeta) gene promoters and expression in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr]. J. Exp. Bot. 65 47–59. 10.1093/jxb/ert346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhang J., Neff M. M., Hong S. W., Zhang H., Deng X. W., et al. (2008). Integration of light and abscisic acid signaling during seed germination and early seedling development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 4495–4500. 10.1073/pnas.0710778105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Wang X. M., Zhou L., He Y., Wang D., Qi Y. H., et al. (2015). Rubisco activase is also a multiple responder to abiotic stresses in rice. PLoS ONE 10:e0140934 10.1371/journal.pone.0140934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.-I., Hong J.-H., Ha J.-O., Kang J.-Y., Kim S. Y. (2000). ABFs, a family of ABA-responsive element binding factors. J. Biol. Chem. 275 1723–1730. 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. I., Park H. J., Park J. H., Kim S., Im M. Y., Seo H. H., et al. (2005). Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase AtCPK32 interacts with ABF4, a transcriptional regulator of abscisic acid-responsive gene expression, and modulates its activity. Plant Physiol. 139 1750–1761. 10.1104/pp.105.069757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M., Xue Q., McCray T., Margavage K., Chen F., Lee J. H., et al. (2013). The PP6 phosphatase regulates ABI5 phosphorylation and abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25 517–534. 10.1105/tpc.112.105767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejimenez E. S., Medrano L., Martinezbarajas E. (1995). Rubisco activase, a possible new member of the molecular chaperone family. Biochemistry 34 2826–2831. 10.1021/bi00009a012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirevska-Kepova K., Holzer R., Simova-Stoilova L., Feller U. (2005). Heat stress effects on ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, Rubisco binding protein and Rubisco activase in wheat leaves. Biol. Plant 49 521–525. 10.1007/s10535-005-0045-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeRidder B. P., Salvucci M. E. (2007). Modulation of Rubisco activase gene expression during heat stress in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) involves post-transcriptional mechanisms. Plant Sci. 172 246–254. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H., Meng Q., Xu J., Tang H., Tang S., Zhang H., et al. (2015). Knock-down of stress inducible OsSRFP1 encoding an E3 ubiquitin ligase with transcriptional activation activity confers abiotic stress tolerance through enhancing antioxidant protection in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 87 441–458. 10.1007/s11103-015-0294-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo D. D., Barros P. M., Cordeiro A. M., Serra T. S., Lourenco T., Chander S., et al. (2012). Seven zinc-finger transcription factors are novel regulators of the stress responsive gene OsDREB1B. J. Exp. Bot. 63 3643–3656. 10.1093/jxb/ers035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Fujita M., Satoh R., Maruyama K., Parvez M. M., Seki M., et al. (2005). AREB1 is a transcription activator of novel ABRE-dependent ABA signaling that enhances drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17 3470–3488. 10.1105/tpc.105.035659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Yoshida T., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2013). Pivotal role of the AREB/ABF-SnRK2 pathway in ABRE-mediated transcription in response to osmotic stress in plants. Physiol. Plant 147 15–27. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01635.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukayama H., Abe R., Uchida N. (2010). SDS-dependent proteases induced by ABA and its relation to Rubisco and Rubisco activase contents in rice leaves. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48 808–812. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galka M. M., Rajagopalan N., Buhrow L. M., Nelson K. M., Switala J., Cutler A. J., et al. (2015). Identification of Interactions between Abscisic Acid and Ribulose-1,5-Bisphosphate Carboxylase/Oxygenase. PLoS ONE 10:e0133033 10.1371/journal.pone.0133033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S. Q., Chen M., Xu Z. S., Zhao C. P., Li L., Xu H. J., et al. (2011). The soybean GmbZIP1 transcription factor enhances multiple abiotic stress tolerances in transgenic plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 75 537–553. 10.1007/s11103-011-9738-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad Y., Rifkin S. A., Pritchard J. K. (2008). Revealing the architecture of gene regulation: the promise of eQTL studies. Trends Genet. 24 408–415. 10.1016/j.tig.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri A. P., Wunsche H., Mitra S., Zavala J. A., Muck A., Svatos A., et al. (2006). Molecular interactions between the specialist herbivore Manduca sexta (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae) and its natural host Nicotiana attenuata. VII. Changes in the plant’s proteome. Plant Physiol. 142 1621–1641. 10.1104/pp.106.088781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson J., Smeekens S. (2009). Sugar perception and signaling–an update. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12 562–567. 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. S., Liu J. H., Chen X. J. (2010). Overexpression of PtrABF gene, a bZIP transcription factor isolated from Poncirus trifoliata, enhances dehydration and drought tolerance in tobacco via scavenging ROS and modulating expression of stress-responsive genes. BMC Plant Biol. 10:230 10.1186/1471-2229-10-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby M., Weisshaar B., Droge-Laser W., Vicente-Carbajosa J., Tiedemann J., Kroj T., et al. (2002). bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 7 106–111. 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02223-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson R. A., Kavanagh T. A., Bevan M. W. (1987). Gus Fusions - Beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher-plants. Embo J. 6 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji K., Wang Y., Sun W., Lou Q., Mei H., Shen S., et al. (2012). Drought-responsive mechanisms in rice genotypes with contrasting drought tolerance during reproductive stage. J. Plant Physiol. 169 336–344. 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Wang J., Tao X., Zhang Y. (2013). Characterization and expression of Rubisco activase genes in Ipomoea batatas. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40 6309–6321. 10.1007/s11033-013-2744-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y., Lau O. S., Deng X. W. (2007). Light-regulated transcriptional networks in higher plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8 217–230. 10.1038/nrg2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Choi H. I., Ryu H. J., Park J. H., Kim M. D., Kim S. Y. (2004a). ARIA, an Arabidopsis arm repeat protein interacting with a transcriptional regulator of abscisic acid-responsive gene expression, is a novel abscisic acid signaling component. Plant Physiol. 136 3639–3648. 10.1104/pp.104.049189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Kang J. Y., Cho D. I., Park J. H., Kim S. Y. (2004b). ABF2, an ABRE-binding bZIP factor, is an essential component of glucose signaling and its overexpression affects multiple stress tolerance. Plant J. 40 75–87. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J., Kang J. Y., Park H. J., Kim M. D., Bae M. S., Choi H. I., et al. (2010). DREB2C interacts with ABF2, a bZIP protein regulating abscisic acid-responsive gene expression, and its overexpression affects abscisic acid sensitivity. Plant Physiol. 153 716–727. 10.1104/pp.110.154617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Zou H. F., Wei W., Hao Y. J., Tian A. G., Huang J., et al. (2008). Soybean GmbZIP44, GmbZIP62 and GmbZIP78 genes function as negative regulator of ABA signaling and confer salt and freezing tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Planta 228 225–240. 10.1007/s00425-008-0731-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., White M. J., MacRae T. H. (2002). Identification of ultraviolet-B responsive genes in the pea, Pisum sativum L. Plant Cell Rep. 20 1067–1074. 10.1007/s00299-002-0440-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Taub C. C., McClung C. R. (1996). Identification of an Arabidopsis thaliana ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activase (RCA) minimal promoter regulated by light and the circadian clock. Plant Physiol. 112 43–51. 10.1104/pp.112.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorca C. M., Potschin M., Zentgraf U. (2014). bZIPs and WRKYs: two large transcription factor families executing two different functional strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 5:169 10.3389/fpls.2014.00169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcolino-Gomes J., Rodrigues F. A., Fuganti-Pagliarini R., Bendix C., Nakayama T. J., Celaya B., et al. (2014). Diurnal oscillations of soybean circadian clock and drought responsive genes. PLoS ONE 9:e86402 10.1371/journal.pone.0086402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinocatt S., Ort D. R. (1992). Low-temperature interrupts circadian regulation of transcriptional activity in chilling-sensitive plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 3731–3735. 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S., Baldwin I. T. (2008). Independently silencing two photosynthetic proteins in Nicotiana attenuata has different effects on herbivore resistance. Plant Physiol. 148 1128–1138. 10.1104/pp.108.124354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S., Baldwin I. T. (2014). RuBPCase activase (RCA) mediates growth-defense trade-offs: silencing RCA redirects jasmonic acid (JA) flux from JA-isoleucine to methyl jasmonate (MeJA) to attenuate induced defense responses in Nicotiana attenuata. New Phytol. 201 1385–1395. 10.1111/nph.12591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhara I., Ugaki M., Hirochika H., Ohshima M., Murakami T., Gotoh Y., et al. (1996). Efficient promoter cassettes for enhanced expression of foregin genes in Dicotyledonous and Monocotyledonous plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 37 49–59. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhawan A., Jain M., Tyagi A. K., Khurana J. P. (2008). Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family in rice. Plant Physiol. 146 333–350. 10.1104/pp.107.112821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco B. M., Ogren W. L. (1993). Localization of light-inducible and tissue-specific regions of the spinach ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (rubisco) activase promoter in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 23 1129–1138. 10.1007/BF00042347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelloux J., Jolivet Y., Fontaine V., Banvoy J., Dizengremel P. (2001). Changes in Rubisco and Rubisco activase gene expression and polypeptide content in Pinus halepensis M. subjected to ozone and drought. Plant Cell Environ. 24 123–131. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00665.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Portis A. R. (1990). Rubisco activase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1015 15–28. 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90211-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portis A. R., Jr. (2003). Rubisco activase–Rubisco’s catalytic chaperone. Photosynth. Res. 75 11–27. 10.1023/A:1022458108678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M. (2005). Regulation of transcription: from lambda to eukaryotes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30 275–279. 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu D., Song Y., Li W. M., Pei X. W., Wang Z. X., Jia S. R., et al. (2011). Isolation and characterization of the organ-specific and light-inducible promoter of the gene encoding rubisco activase in potato (Solanum tuberosum). Genet. Mol. Res. 10 621–631. 10.4238/vol10-2gmr1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece-Hoyes J. S., Marian Walhout A. J. (2012). Yeast one-hybrid assays: a historical and technical perspective. Methods 57 441–447. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook F., Hadingham S. A., Li Y., Bevan M. W. (2006). Sugar and ABA response pathways and the control of gene expression. Plant Cell Environ. 29 426–434. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01477.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scafaro A. P., Haynes P. A., Atwell B. J. (2010). Physiological and molecular changes in Oryza meridionalis Ng., a heat-tolerant species of wild rice. J. Exp. Bot. 61 191–202. 10.1093/jxb/erp294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung D., Risopatron J. P., Jones B. J., Marc J. (2012). Circadian clock-dependent gating in ABA signalling networks. Protoplasma 249 445–457. 10.1007/s00709-011-0304-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan X., Wang J., Chua L., Jiang D., Peng W., Xie D. (2011). The role of Arabidopsis Rubisco activase in jasmonate-induced leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 155 751–764. 10.1104/pp.110.166595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer R. J., Salvucci M. E. (2002). Rubisco: structure, regulatory interactions, and possibilities for a better enzyme. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53 449–475. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stec B. (2012). Structural mechanism of RuBisCO activation by carbamylation of the active site lysine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 18785–18790. 10.1073/pnas.1210754109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To K. Y., Suen D. F., Chen S. C. G. (1999). Molecular characterization of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activase in rice leaves. Planta 209 66–76. 10.1007/s004250050607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno Y., Furihata T., Abe H., Yoshida R., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2000). Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper transcription factors involved in an abscisic acid-dependent signal transduction pathway under drought and high-salinity conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 11632–11637. 10.1073/pnas.190309197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walia H., Wilson C., Condamine P., Liu X., Ismail A. M., Close T. J. (2007). Large-scale expression profiling and physiological characterization of jasmonic acid-mediated adaptation of barley to salinity stress. Plant Cell Environ. 30 410–421. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Li X. F., Zhou Z. J., Feng X. P., Yang W. J., Jiang D. A. (2010). Two Rubisco activase isoforms may play different roles in photosynthetic heat acclimation in the rice plant. Physiol. Plant 139 55–67. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01344.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang H., Ma Y., Du H., Yang Q., Yu D. (2015). Identification of transcriptional regulatory nodes in soybean defense networks using transient co-transactivation assays. Front. Plant Sci. 6:915 10.3389/fpls.2015.00915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watillon B., Kettmann R., Boxus P., Burny A. (1993). Developmental and circadian pattern of Rubisco activase mRNA accumulation in apple plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 23 501–509. 10.1007/Bf00019298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner N., Weiste C., Droge-Laser W. (2011). Molecular screening tools to study Arabidopsis transcription factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2:68 10.3389/fpls.2011.00068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Li J., Gangappa S. N., Hettiarachchi C., Lin F., Andersson M. X., et al. (2014). Convergence of light and ABA signaling on the ABI5 promoter. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004197 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Lu Q., Wen X., Chen F., Lu C. (2012). Functional analysis of the rice rubisco activase promoter in transgenic Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 418 565–570. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J., Derynck M. R., Li X., Telmer P., Marsolais F., Dhaubhadel S. (2010). A single-repeat MYB transcription factor, GmMYB176, regulates CHS8 gene expression and affects isoflavonoid biosynthesis in soybean. Plant J. 62 1019–1034. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04214.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z., Meng F., Song H., Wang X., Xu X., Yu D. (2010). Expression quantitative trait loci analysis of two genes encoding rubisco activase in soybean. Plant Physiol. 152 1625–1637. 10.1104/pp.109.148312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z., Zhang Z., Deng D., Chao M., Gao Q., Wang Y., et al. (2014). Characterization of Rubisco activase genes in maize: an alpha-isoform gene functions alongside a beta-isoform gene. Plant Physiol. 164 2096–2106. 10.1104/pp.113.230854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T., Fujita Y., Sayama H., Kidokoro S., Maruyama K., Mizoi J., et al. (2010). AREB1, AREB2, and ABF3 are master transcription factors that cooperatively regulate ABRE-dependent ABA signaling involved in drought stress tolerance and require ABA for full activation. Plant J. 61 672–685. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04092.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Portis A. R. (1999). Mechanism of light regulation of Rubisco: a specific role for the larger Rubisco activase isoform involving reductive activation by thioredoxin-f. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 9438–9443. 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Xing A., Staswick P., Clemente T. E. (1999). The use of glufosinate as a selective agent in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of soybean. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 56 37–46. 10.1023/A:1006298622969 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Tung C.-W., Eizenga G. C., Wright M. H., Ali M. L., Price A. H., et al. (2011). Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nat. Commun. 2:467 10.1038/ncomms1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M., Simons B., Zhu N., Oppenheimer D. G., Chen S. (2010). Analysis of abscisic acid responsive proteins in Brassica napus guard cells by multiplexed isobaric tagging. J. Proteomics 73 790–805. 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.