Abstract

Despite their inherent non-equilibrium nature1, living systems can self-organize in highly ordered collective states2,3 that share striking similarities with the thermodynamic equilibrium phases4,5 of conventional condensed matter and fluid systems. Examples range from the liquid-crystal-like arrangements of bacterial colonies6,7, microbial suspensions8,9 and tissues10 to the coherent macro-scale dynamics in schools of fish11 and flocks of birds12. Yet, the generic mathematical principles that govern the emergence of structure in such artificial13 and biological6–9,14 systems are elusive. It is not clear when, or even whether, well-established theoretical concepts describing universal thermostatistics of equilibrium systems can capture and classify ordered states of living matter. Here, we connect these two previously disparate regimes: Through microfluidic experiments and mathematical modelling, we demonstrate that lattices of hydrodynamically coupled bacterial vortices can spontaneously organize into distinct phases of ferro- and antiferromagnetic order. The preferred phase can be controlled by tuning the vortex coupling through changes of the inter-cavity gap widths. The emergence of opposing order regimes is tightly linked to the existence of geometry-induced edge currents15,16, reminiscent of those in quantum systems17–19. Our experimental observations can be rationalized in terms of a generic lattice field theory, suggesting that bacterial spin networks belong to the same universality class as a wide range of equilibrium systems.

Lattice field theories (LFTs) have been instrumental in uncovering a wide range of fundamental physical phenomena, from quark confinement in atomic nuclei20 and neutron stars21 to topologically protected states of matter22 and transport in novel magnetic23 and electronic24,25 materials. LFTs can be constructed either by discretizing the space-time20 continuum underlying classical and quantum field theories, or by approximating discrete physical quantities, such as the electron spins in a crystal lattice, through continuous variables. In equilibrium thermodynamics, LFT approaches have proved invaluable both computationally and analytically, for a single LFT often represents a broad class of microscopically distinct physical systems that exhibit the same universal scaling behaviours in the vicinity of a phase transition4,26. However, until now there has been little evidence as to whether the emergence of order in living matter can be understood within this universality framework. Our combined experimental and theoretical analysis reveals a number of striking analogies between the collective cell dynamics in bacterial fluids and known phases of condensed matter systems, thereby implying that universality concepts may be more broadly applicable than previously thought.

To realize a microbial non-equilibrium LFT, we injected dense suspensions of the rod-like swimming bacterium Bacillus subtilis into shallow polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS) chambers in which identical circular cavities are connected to form one- and two-dimensional (2D) lattice networks (Figs. 1 & 3, Supplementary Fig. 6; Methods). Each cavity is 50 μm in diameter and 18 μm deep, a geometry known to induce a stably circulating vortex when a dense bacterial suspension is confined within an isolated flattened droplet15. For each cavity i, we define the continuous vortex spin variable Vi(t) at time t as the total angular momentum of the local bacterial flow within this cavity, determined by particle imaging velocimetry (PIV) analysis (Fig. 1b,f; Supplementary Videos 1 & 2; Methods). To account for the effect of oxygenation variability on suspension motility9, flow velocities are normalized by the overall root mean square (RMS) speed measured in the corresponding experiment. Bacterial vortices in neighbouring cavities i ~ j interact through a gap of predetermined width w (Fig. 1f). To explore different interaction strengths, we performed experiments over a range of gap parameters w (Methods). For square lattices, we varied w from 4 to 25 μm and found that for all but the largest gaps, w ≤ w* ≈ 20 μm, the suspensions generally self-organize into coherent vortex lattices, exhibiting domains of correlated spin whose characteristics depend on coupling strength (Fig. 1a,e). If the gap size exceeds w*, bacteria can move freely between cavities and individual vortices cease to exist. A similar order–disorder transition is seen in triangular lattices (Fig. 3). Here, we focus exclusively on the vortex regime w < w* and quantify preferred magnetic order through the normalized mean spin–spin correlation , where denotes a sum over pairs {i, j} of adjacent cavities and 〈·〉 denotes time average.

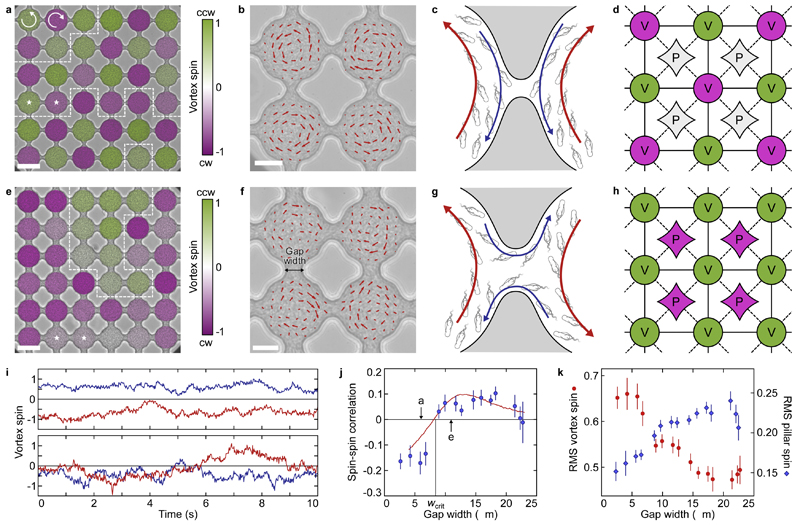

Figure 1. Edge currents determine antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic order in a square lattice of bacterial vortices.

a, Three domains of antiferromagnetic order highlighted by dashed white lines (gap width w = 6 μm). Scale bar: 50 μm. Overlaid false colour shows spin magnitude (see Supplementary Video 1 for raw data). b, Bacterial flow PIV field within an antiferromagnetic domain (Supplementary Video 1). For clarity, not all velocity vectors are shown. Largest arrows correspond to speed 40 μm/s. Scale bar: 20 μm. c, Schematic of bacterial flow circulation in the vicinity of a gap. For small gaps w < wcrit, bacteria forming the edge currents (blue arrows) swim across the gap, remaining in their original cavity. Bulk flow (red) is directed opposite to the edge current15,16 (Supplementary Video 3). d, Graph of the Union Jack double-lattice model in an antiferromagnetic state with zero net pillar circulation. Solid and dashed lines depict vortex–vortex and vortex–pillar interactions of respective strengths Jv and Jp. Vortices and pillars are colour-coded according to their spin. e, For supercritical gap widths w > wcrit, extended domains of ferromagnetic order predominate (Supplementary Video 2; w = 11 μm). Scale bar: 50 μm. f, PIV field within a ferromagnetic domain (Supplementary Video 2). Largest arrows: 36 μm/s. Scale bar: 20 μm. g, For w > wcrit, bacteria forming the edge current (blue arrows) swim along the PDMS boundary through the gap, driving bulk flows (red) in the opposite directions, thereby aligning neighbouring vortex spins. h, Ferromagnetic state of the Union Jack lattice induced by edge current loops around the pillars. i, Trajectories of neighbouring spins (*-symbols in a,e) fluctuate over time, signalling exploration of an equilibrium under a non-zero effective temperature (top: antiferromagnetic; bottom: ferromagnetic). j, The zero of the spin–spin correlation χ at wcrit ≈ 8 μm marks the phase transition. The best-fit Union Jack model (solid line) is consistent with the experimental data. k, RMS vortex spin decreases with the gap size w, showing weakening of the circulation. RMS pillar spin increases with w, reflecting enhanced bacterial circulation around pillars. Each point in j,k represents an average over ≥ 5 movies in 3 μm bins at 1.5 μm intervals; vertical bars indicate standard errors (Methods).

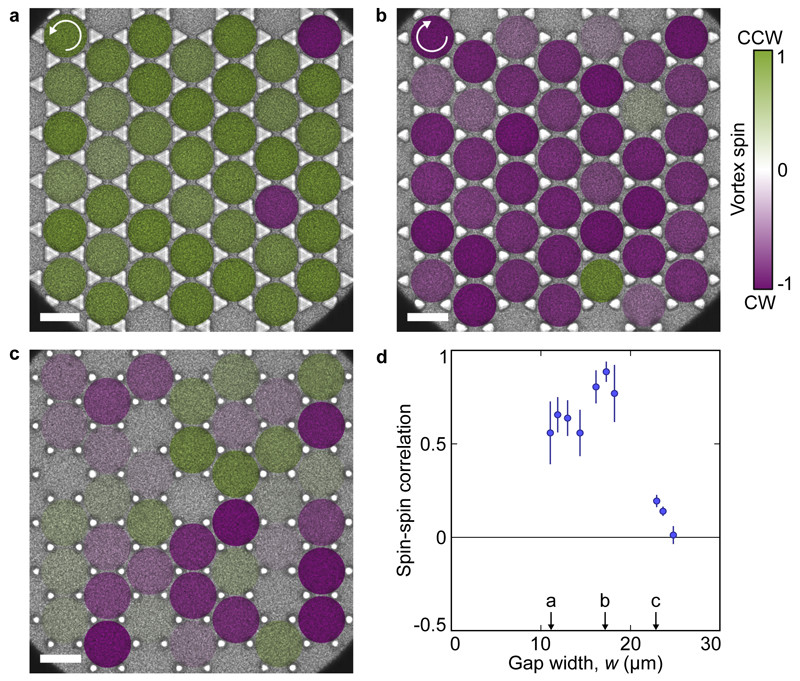

Figure 3. Frustration in triangular lattices determines the preferred order.

a,b, Triangular lattices favour ferromagnetic states of either handedness (Supplementary Video 4). Vortices are colour-coded by spin. c, At the largest gap size, bacterial circulation becomes unstable. Scale bar: 50 μ m. d, The spin–spin correlation χ shows strongly enhanced ferromagnetic order compared with the square lattice (Fig. 1j). Each point represents an average over ≥ 5 movies in 3 μm bins at 1.5 μm intervals; vertical bars indicate standard errors (Methods).

Square lattices reveal two distinct states of preferred magnetic order (Fig. 1a,e,i), one with χ < 0 and the other with χ > 0, transitioning between them at a critical gap width wcrit ≈ 8 μm (Fig. 1j). For subcritical values w < wcrit, we observe an antiferromagnetic phase with anti-correlated (χ < 0) spin orientations between neighbouring chambers on average (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Video 1). By contrast, for w > wcrit, spins are positively correlated (χ > 0) in a ferromagnetic phase (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Video 2). Noting that the RMS spin 〈Vi(t)2〉1/2 decays only slowly with increasing gap width w → w* (Fig. 1k), and that the chambers do not impose any preferred handedness on the vortex spins (Supplementary Fig. 1 & Sec. 1), we conclude that the observed phase behaviour is caused by spin–spin interactions. However, although both phases possess a well-defined average vortex–vortex correlation, the individual spins fluctuate randomly over time as ordered domains split, merge and flip (Fig. 1i, Supplementary Figs. 1 & 3) while the system explores configuration space inside a statistical steady state (Supplementary Secs. 1 & 3). Thus, although the bacterial vortex spins {Vi(t)} define a real-valued lattice field, the phenomenology of these continuous bacterial spin lattices is qualitatively similar to that of the classical 2D Ising model4 with discrete binary spin variables si ∈ {±1}, whose configurational probability at finite temperature T = (kBβ)–1 is described by a thermal Boltzmann distribution , where J > 0 corresponds to ferromagnetic and J < 0 to antiferromagnetic order. The detailed theoretical analysis below shows that the observed phases in the bacterial spin system can be understood quantitatively in terms of a generic quartic LFT comprising two dual interacting lattices. The introduction of a double lattice is necessitated by the microscopic structure of the underlying bacterial flows. By analogy with a lattice of interlocking cogs, one might have intuitively expected that the antiferromagnetic phase would be favoured, since only in this configuration does the bacterial flow along the cavity boundaries conform across the inter-cavity gap, avoiding the potentially destabilizing head-to-head collisions that would occur with opposing flows (Fig. 1b,c). However, the extent of the observed ferromagnetic phase highlights a competing biofluid-mechanical effect.

Just as the quantum Hall effect17 and the transport properties of graphene18,19 arise from electric edge currents, the opposing order regimes observed here are explained by the existence of analogous bacterial edge currents. At the boundary of an isolated flattened droplet of a bacterial suspension, a single layer of cells—an edge current—can be observed swimming against the bulk circulation15,16. This narrow cell layer is key to the suspension dynamics: the hydrodynamics of the edge current circulating in one direction advects nearby cells in the opposite direction, which in turn dictate the bulk circulation by flow continuity through steric and hydrodynamic interactions16,27. Identical edge currents are present in our lattices (Supplementary Video 3) and explain both order regimes as follows. In the antiferromagnetic regime, when w < wcrit, the edge current driving a particular vortex will pass over the gap without leaving the cavity (Fig. 1c). Interaction with a neighbouring edge current through the gap favours parallel flow, inducing counter-circulation of neighbouring vortices and therefore driving antiferromagnetic order (Fig. 1d). However, when w > wcrit, the edge currents can no longer pass over the gaps and instead wind around the star-shaped pillars dividing the cavities (Fig. 1g). A clockwise (resp. counter-clockwise) edge current on a pillar induces counter-clockwise (resp. clockwise) circulation about the pillar in a thin region near its boundary. Flow continuity then induces clockwise (resp. counter-clockwise) flow in all cavities adjacent to the pillar, resulting in ferromagnetic order (Fig. 1h). Thus by viewing the system as an anti-cooperative Union Jack lattice28,29 of both bulk vortex spins Vi and near-pillar circulations Pj, we accommodate both order regimes: antiferromagnetism as indefinite circulations Pj = 0 and alternating spins Vi = ±V (Fig. 1d), and ferromagnetism as definite circulations Pj = –P and uniform spins Vi = V (Fig. 1h). To verify these considerations, we determined the net near-pillar circulation Pj(t) using PIV (Methods) and found that the RMS circulation 〈Pj(t)2〉1/2 shows the expected monotonic increase as the inter-cavity gap widens (Fig. 1k).

Competition between the vortex–vortex and vortex–pillar interactions determines the resultant order regime. Their relative strengths can be inferred by mapping each experiment onto a continuous-spin Union Jack lattice (Fig. 1d,h). In this model, the interaction energy of the time-dependent vortex spins V = {Vi} and pillar circulations P = {Pj} is defined by the LFT Hamiltonian

| (1) |

The first two sums are vortex–vortex and vortex–pillar interactions with strengths Jv, Jp < 0, where ~ denotes adjacent lattice pairs. The last two sums are individual vortex and pillar circulation potentials. Vortices must be subject to a quartic potential function with bv > 0 to allow for a potentially double-welled potential if av < 0, encoding the observed symmetry breaking into spontaneous circulation absent other interactions15,27. In contrast, our data analysis implies that pillar circulations are sufficiently described by a quadratic potential of strength ap > 0 (Supplementary Fig. 4 & Sec. 4). To account for the experimentally observed spin fluctuations (Fig. 1i, Supplementary Fig. 1), we model the dynamics of the lattice fields V and P through the coupled stochastic differential equations (SDEs)

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

where Wv and Wp are vectors of uncorrelated Wiener processes representing intrinsic and thermal fluctuations. The overdamped dynamics in Eq. (2) neglects dissipative Onsager-type cross-couplings as the dominant contribution to friction stems from the nearby no-slip PDMS boundaries (Supplementary Sec. 7). The parameters Tv and Tp set the strength of random perturbations from energy-minimizing behaviour. In the equilibrium limit when Tv = Tp = T, the stationary statistics of the solutions of Eq. (2) obey the Boltzmann distribution ∝ e–H/T. We inferred all seven parameters of the full SDE model for each experiment by linear regression on a discretization of the SDEs (Supplementary Fig. 2 & Sec. 2). The differing sublattice temperatures Tv ≠ Tp found show that the system is not in thermodynamic equilibrium due to its active microscopic constituents (Supplementary Fig. 2). Instead, the system is in a pseudo-equilibrium statistical steady state (Supplementary Sec. 1), which we will soon show can be reduced to an equilibrium-like description. As a cross-validation, we fitted appropriate functions of gap width w to these estimates and simulated the resulting SDE model over a range of w on a 6 × 6 lattice concordant with the observations (Supplementary Sec. 3). The agreement between experimental data and the numerically obtained vortex–vortex correlation χ(w) supports the validity of the double-lattice model and its underlying approximations (Fig. 1j).

To reconnect with the classical 2D Ising model and understand better the experimentally observed phase transition, we project the Hamiltonian (1) onto an effective square lattice model by making a mean-field assumption for the pillar circulations. In the experiments, Pi is linearly correlated with the average spin of its vortex neighbours , with a constant of proportionality −α < 0 only weakly dependent on gap width (Supplementary Fig. 4 & Sec. 4). Replacing effectively Pi → −α[Pi]V as a mean field variable in the model eliminates all pillar circulations, yielding a standard quartic LFT for V (see Supplementary Sec. 4 for a detailed derivation). The mean-field dynamics are then governed by the reduced SDE with effective temperature and energy

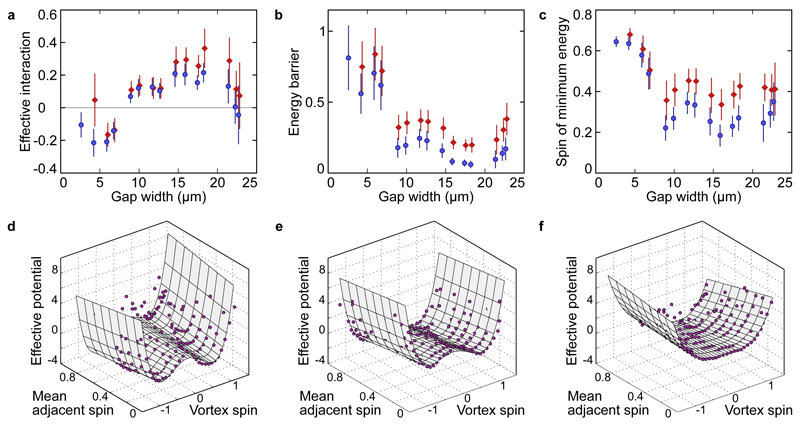

which has steady-state probability density with β = 1/T, and where and b = bv. Note that in the limit a → –∞ and b → +∞ with a/b fixed, the classical two-state Ising model is recovered by identifying . The reduced coupling constant J relates to those of the double-lattice model (Jv, Jp) in the thermodynamic limit as (Supplementary Sec. 4), making manifest how competition between Jv and Jp can result in both antiferromagnetic or ferromagnetic behaviour. We estimated βJ, βa and βb for each experiment by directly fitting the effective one-spin potential via the log-likelihood (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 5 & Sec. 5). These estimates match those obtained independently using SDE regression methods (Fig. 2a–c; Supplementary Sec. 5), and show the transition from antiferromagnetic interaction (βJ < 0) to ferromagnetic interaction (βJ > 0) at wcrit (Fig. 2a). As the gap width increases, the energy barrier to spin change falls (Fig. 2b) and the magnitude of the lowest energy spin decreases (Fig. 2c) due to weakening confinement within each cavity, visible as a flattening of the one-spin effective potential (Fig. 2d–f; Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 2. Best-fit mean-field LFT model captures the phase transition in the square lattice.

a, A sign change of the effective interaction βJ signals the transition from antiferro- to ferromagnetic states. b, The effective energy barrier, βa2/(4b) when a < 0 and zero when a > 0 (Supplementary Sec. 5), decreases with the gap size w, reflecting increased susceptibility to fluctuations. c, The spin Vmin minimizing the single-spin potential (Supplementary Sec. 5) decreases with w in agreement with the decrease in the RMS vortex spin (Fig. 1k). Each point in a–c represents an average over ≥ 5 movies in 3 μm bins at 1.5 μm intervals; blue circles are from distribution fitting, red diamonds are from SDE regression, and vertical bars indicate standard errors (Methods). d-f, Examples of the effective single-spin potential conditional on the mean spin of adjacent vortices [V]V. Data (points) and estimated potential (surface) for three movies with gap widths 6, 10 and 17 μm.

Experiments on lattices of different symmetry groups lend further insight into the competition between edge currents and bulk flow. Unlike their square counterparts, triangular lattices cannot support antiferromagnetic states without frustration. Therefore, ferromagnetic order should be enhanced in a triangular bacterial spin lattice. This is indeed observed in our experiments: at moderate gap size , we found exclusively a highly robust ferromagnetic phase of either handedness (Fig. 3a,b,d; Supplementary Video 4), reminiscent of quantum vortex lattices in Bose–Einstein condensates30. At comparable gap size, the spin correlation is approximately 4 to 8 times larger than in the square lattice. Increasing the gap size beyond 20 μm eventually destroys the spontaneous circulation within the cavities and a disordered state prevails (Fig. 3c,d), with a sharper transition than for the square lattices (Fig. 1j). Conversely, a 1D line lattice exclusively exhibits antiferromagnetic order as the suspension is unable to maintain the very long uniform edge currents that would be necessary to sustain a ferromagnetic state (Supplementary Fig. 6 & Sec. 6). These results manifest the importance of lattice geometry and dimensionality for vortex ordering in bacterial spin lattices, in close analogy with their electromagnetic counterparts.

Understanding the ordering principles of microbial matter is a key challenge in active materials design13, quantitative biology and biomedical research. Improved prevention strategies for pathogenic biofilm formation, for example, will require detailed knowledge of how bacterial flows interact with complex porous surface structures to create the stagnation points at which biofilms can nucleate. Our study shows that collective excitations in geometrically confined bacterial suspensions can spontaneously organize in phases of magnetic order that can be robustly controlled by edge currents. These results demonstrate fundamental similarities with a broad class of widely studied quantum systems17,19,30, suggesting that theoretical concepts originally developed to describe magnetism in disordered media could potentially capture microbial behaviours in complex environments. Future studies may try to explore further the range and limits of this promising analogy.

Methods

Experiments

Wild-type Bacillus subtilis cells (strain 168) were grown in Terrific Broth (Sigma). A monoclonal colony was transferred from an agar plate to 25 mL of medium and left to grow overnight at 35°C on a shaker. The culture was diluted 200-fold into fresh medium and harvested after approximately 5 hours when more than 90% of the bacteria were swimming, as visually verified on a microscope. 10 mL of the suspension was then concentrated by centrifugation at 1500g for 10 minutes, resulting in a pellet with volume fraction approximately 20% which was used without further dilution.

The microchambers were made of polydimethyl siloxane (PDMS) bound to a glass coverslip by oxygen plasma etching. These comprised a square, triangular or linear lattice of ~ 18 μm-deep circular cavities with 60 μm between centres, each of diameter ~ 50 μm, connected by 4–25 μm-wide gaps for linear and square lattices (Fig. 1a,e; Supplementary Fig. 6) and 10–25 μm-wide gaps for triangular lattices (Fig. 3a–c). The smallest possible gap size was limited by the fidelity of the etching.

Approximately 5 μL of the concentrated suspension was manually injected into the chamber using a syringe. Both inlets were then sealed to prevent external flow. We imaged the suspension on an inverted microscope (Zeiss, Axio Observer Z1) under bright field illumination, through a 40× oil-immersion objective. Movies 10 s long were recorded at 60 f.p.s. on a high-speed camera (Photron Fastcam SA3) at 4 and 8 minutes after injection. Though the PDMS lattices were typically ~ 15 cavities across, to avoid boundary effects and to attain the pixel density necessary for PIV we imaged a central subregion spanning 6 × 6 cavities for square lattices, 7 × 6 cavities for triangular lattices, and 7 cavities for linear lattices (multiple of which were captured on a single slide).

Fluorescence in Supplementary Video 3 was achieved by labelling the membranes of a cell subpopulation with fluorophore FM4-64 following the protocol of Lushi et al.16 The suspension was injected into an identical triangular lattice as in the primary experiments and imaged at 5.6 f.p.s. on a spinning-disc confocal microscope through a 63× oil-immersion objective.

Analysis

For each frame of each movie, the bacterial suspension flow field u(x, y, t) was measured by standard particle image velocimetry (PIV) without time averaging, using a customized version of mPIV (http://www.oceanwave.jp/softwares/mpiv/). PIV subwindows were 16 × 16 pixels with 50% overlap, yielding ~ 150 vectors per cavity per frame. Cavity regions were identified in each movie by manually placing the centre and radius of the bottom left cavity, measuring vectors to its immediate neighbours, and repeatedly translating to generate the full grid. Pillar edges were then calculated from the cavity grid and the gap width (measured as the minimum distance between adjacent pillars).

The spin Vi(t) of each cavity i at time t is defined as the normalized planar angular momentum

where ri(x, y) is the vector from the cavity centre to (x, y), and sums run over all PIV grid points (x, y)i inside cavity i. For each movie, we normalize velocities by the root-mean-square (RMS) suspension velocity , where the average is over all grid points (x, y) and all times t, to account for the effects of variable oxygenation on motility9; we found an ensemble average with s.d. 3.6 μm s−1 over all experiments. This definition has Vi(t) > 0 for counter-clockwise spin and Vi(t) < 0 for clockwise spin. A vortex of radially-independent speed, i.e. where is the azimuthal unit vector, has Vi(t) = ±1; conversely, randomly oriented flow has Vi(t) = 0. The average spin–spin correlation χ of a movie is then defined as

where Σi~j denotes a sum over pairs {i, j} of adjacent cavities and 〈 · 〉 denotes an average over all frames. If all vortices share the same sign, then χ = 1 (ferromagnetism); if each vortex is of opposite sign to its neighbours, then χ = –1 (antiferromagnetism); if the vortices are uniformly random, then χ = 0. Similarly, the circulation Pj (t) about pillar j at time t is defined as the normalized average tangential velocity

where is the unit vector tangential to the pillar, and sums run over PIV grid points (x, y)j closer than 5 μm to the pillar j.

Results presented are typically averaged in bins of fixed gap width. All plots with error bars use 3 μm large bins, calculated every 1.5 μm (50% overlap), and bins with fewer than 5 movies were excluded. Error bars denote standard error. Bin counts for square lattices (Fig. 1j,k; Fig. 2a–c; Supplementary Figs. 4 & 7) are 8, 8, 13, 14, 21, 27, 27, 22, 18, 22, 20, 11, 7, 13, 7; bin counts for triangular lattices (Fig. 3d) are 5, 14, 16, 13, 16, 15, 5, 5, 10, 7; and bin counts for linear lattices (Supplementary Fig. 6) are 5, 7, 8, 8, 9, 9, 6, 5, 6, 7, 6, 8, 9, 5, 6, 5, 6.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Vasily Kantsler and Enkeleida Lushi for assistance and discussions. This work was supported by European Research Council Advanced Investigator Grant 247333 (H.W. and R.E.G.), EPSRC (H.W. and R.E.G.), an MIT Solomon Buchsbaum Fund Award (J.D.) and an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship (J.D.).

Footnotes

Author contributions All authors designed the research and collaborated on theory. H.W. performed experiments and PIV analysis. H.W. and F.G.W. analysed PIV data and performed parameter inference. F.G.W. and J.D. wrote simulation code. All authors wrote the paper.

Additional information Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Competing financial interests The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Schrödinger E. What is Life. Cambridge University Press; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vicsek T, Zafeiris A. Collective motion. Phys Rep. 2012;517:71–140. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchetti MC et al. Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Rev Mod Phys. 2013;85:1143–1189. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kardar M. Statistical Physics of Fields. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mermin ND. The topological theory of defects in ordered media. Rev Mod Phys. 1979;51:591–648. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben Jacob E, Becker I, Shapira Y, Levine H. Bacterial linguistic communication and social intelligence. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volfson D, Cookson S, Hasty J, Tsimring LS. Biomechanical ordering of dense cell populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;150:15346–15351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706805105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riedel IH, Kruse K, Howard J. A self-organized vortex array of hydrodynamically entrained sperm cells. Science. 2005;309:300–303. doi: 10.1126/science.1110329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunkel J et al. Fluid dynamics of bacterial turbulence. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110:228102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.228102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu J, Roman A-C, Carvajal-Gonzalez JM, Mlodzik M. Wg and Wnt4 provide long-range directional input to planar cell polarity orientation in drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1045–1055. doi: 10.1038/ncb2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz Y, Ioannou CC, Tunstro K, Huepe C, Couzin ID. Inferring the structure and dynamics of interactions in schooling fish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18720–18725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107583108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavagna A et al. Scale-free correlations in starling flocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11865–11870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005766107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez T, Chen DTN, DeCamp SJ, Heymann M, Dogic Z. Spontaneous motion in hierarchically assembled active matter. Nature. 2012;491:431–434. doi: 10.1038/nature11591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sokolov A, Aranson IS. Physical properties of collective motion in suspensions of bacteria. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109:248109. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.248109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wioland H, Woodhouse FG, Dunkel J, Kessler JO, Goldstein RE. Confinement stabilizes a bacterial suspension into a spiral vortex. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110:268102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.268102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lushi E, Wioland H, Goldstein RE. Fluid flows created by swimming bacteria drive self-organization in confined suspensions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:9733–9738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405698111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Büttiker M. Absence of backscattering in the quantum Hall effect in multiprobe conductors. Phys Rev B. 1988;38:9375–9389. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.38.9375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kane CL, Mele EJ. Quantum spin hall effect in graphene. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95:226801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.226801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castro Neto AH, Guinea F, Peres NMR, Novoselov KS, Geim AK. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev Mod Phys. 2009;81:109–162. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson KG. Confinement of quarks. Phys Rev D. 1974;10:2445–2459. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glendenning NK. Compact Stars Nuclear Physics Particle Physics and General Relativity. Springer; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battye RA, Sutcliffe PM. Skyrmions with massive pions. Phys Rev C. 2006;73:055205. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagaosa N, Tokura Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:899–911. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novoselov KS et al. Two-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in graphene. Nature. 2005;438:197–200. doi: 10.1038/nature04233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drut JE, Lähde TA. Lattice field theory simulations of graphene. Phys Rev B. 2009;79:165425. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández R, Fröhlich J, Sokal AD. Random Walks Critical Phenomena and Triviality in Quantum Field Theory. Springer Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodhouse FG, Goldstein RE. Spontaneous circulation of confined active suspensions. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109:168105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.168105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaks VG, Larkin AI, Ovchinnikov Yu N. Ising model with interaction between non-nearest neighbors. Sov Phys JETP. 1966;22:820–826. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephenson J. Ising model with antiferromagnetic next-nearest-neighbor coupling: Spin correlations and disorder points. Phys Rev B. 1970;1:4405–4409. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abo-Shaeer JR, Raman C, Vogels JM, Ketterle W. Observation of vortex lattices in Bose-Einstein condensates. Science. 2001;292:476–479. doi: 10.1126/science.1060182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.