Abstract

Objective:

Despite the high prevalence of blunt (i.e., hollowed-out cigars that are filled with marijuana) use among Black marijuana smokers, few studies have examined if and how blunt users differ from traditional joint users.

Method:

The current study compared the prevalence and patterns of use for those who smoked blunts in the past month (i.e., blunt users) with those who used marijuana through other methods (i.e., other marijuana users). The sample included 935 Black past-month marijuana smokers participating in the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Results:

Among past-month marijuana smokers, 73.2% were blunt users and 26.8% were other marijuana users. Overall, blunt users initiated marijuana use at an earlier age (15.9 vs. 17.3 years, p < .01) and reported more days of marijuana use in the past month (16 vs. 8 days, p < .01) than did other marijuana users. There were also differences by gender. Among females, blunt users reported a higher odds of past-year marijuana abuse or dependence (23.8%) than other marijuana users (11.2%) (adjusted odds ratio = 1.23, 95% CI [1.12, 3.17], p < .01). However, blunt-using males reported similar odds of past-year marijuana abuse or dependence (approximately 25%) as other marijuana-using males.

Conclusions:

These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions for blunt users as a subgroup of marijuana users, especially among Black females, who may be at increased risk for developing a marijuana use disorder as a result of blunt smoking.

Although the data on the health impact of marijuana use remain inconclusive, likely because of lack of standardization in methodology across studies (i.e., measurement of different types/strains of marijuana and patterns and severity of use), there is burgeoning evidence that marijuana use may increase risk of respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses and negative psychiatric and cognitive outcomes among regular users (Hall & Degenhardt, 2009, 2014). The overall public health burden of increasing marijuana use, in the context of more lenient marijuana policy (Wall et al., 2011), will likely increase.

Although decades of research has focused on the growing problem of marijuana use, many of the studies have focused on users who smoke marijuana through joints (Freeman et al., 2014; Laporte et al., 2014). Research focusing solely on joint users may not generalize to Black individuals, who are more likely to smoke marijuana through blunts (i.e., hollowed-out cigars that are filled with marijuana; Golub et al., 2006; Sinclair et al., 2012; Timberlake, 2013). Few studies have examined if and how blunt users differ from joint users (Cooper & Haney, 2009; Ream et al., 2006), and an even smaller subset of these studies focus specifically on Black adolescents or adults (Sifaneck et al., 2006). The limited research on blunt use is a barrier to progress in treating marijuana use among Blacks. The present study addresses deficiencies in the current literature by examining drug use patterns of blunt users versus other types of marijuana users (e.g., joint users) and assessing whether these patterns vary by gender among Black marijuana smokers.

Marijuana and tobacco co-use is a major health concern (Agrawal et al., 2012). A recent review found that being Black was one of the strongest predictors of marijuana and tobacco co-use among young adults, and this is likely because of the high prevalence of blunt use among Blacks (Ramo et al., 2012). The adult literature also demonstrates an association between being Black and co-use, with co-use increasing significantly in this population over the past decade (Schauer et al., 2015). Blacks may prefer blunts to joints because blunts can hold more marijuana, they burn more slowly, they are easier to transport and conceal, they help culturally distinguish young marijuana users from the older generation of marijuana users, and Blacks are more likely than other racial groups to have friends who smoke blunts (Fairman, 2015; Mariani et al., 2011; Ream et al., 2006; Sifaneck et al., 2006; Sinclair et al., 2012).

In addition, the perception of harm from cannabis use and knowledge of its health effects among Black blunt users are lower than among those who use marijuana or tobacco products alone (Sinclair et al., 2013). Blunts were introduced by the Black community and promoted through hip-hop culture (Ream et al., 2006). Although blunt smoking is common among Blacks, a limited number of studies (Cooper & Haney, 2009) have compared blunt use with the more frequent practice of joint use to determine differences relevant to clinical practice and research.

A small body of literature has revealed differences in blunt users compared with users who consume marijuana through alternative methods. Moolchan et al. (2005) found that blunt smoking was associated with increased carbon monoxide levels, thereby increasing risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases (Cheng et al., 2010) compared with non–blunt marijuana smoking among adolescents. Further, studies have found that adolescent and young adult blunt smokers had significantly greater odds of being dependent on cannabis and tobacco (Ream et al., 2008; Timberlake, 2009). In a mixed-methods ethnographic and survey investigation of marijuana use among youth in New York City, researchers found that blunt users were younger, less educated, and more likely to live at home, report legal trouble, and be involved with the distribution of illicit substances than joint users (Ream et al., 2006). Given the negative health consequences of blunts (Cooper & Haney, 2009) and high prevalence of blunt use among Blacks (Sinclair et al., 2012), more research on blunt use among Blacks is warranted.

Although literature concerning blunt use among Blacks is growing (Montgomery & Oluwoye, 2015), scant research has examined the correlates of blunt use in this population. First, the existing literature on blunt use among Blacks does not examine whether or how blunt users differ from other marijuana users (e.g., joint smokers). Second, although research has found gender differences in blunt use (Cooper & Haney, 2009), few studies have examined these differences among Black men and women. Third, few studies have used national survey data to examine blunt use among Blacks (Montgomery & Oluwoye, 2015). Fourth, some studies have suggested that marijuana and tobacco co-use are associated with an increased risk of mentholated cigarette use (Azagba & Sharaf, 2014) and heavy alcohol use (Buu et al., 2015), but this has not been examined among Blacks who use blunts.

The current study was designed to examine the following questions among Black males and females participating in the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): (a) Among past-month marijuana users, what are the prevalence rates of blunt use and other marijuana use (e.g., joints), and (b) how does age at first marijuana use and use of other substances differ among blunt users versus other marijuana users? Given the gender differences observed in the developmental trajectories of marijuana use (Buu et al., 2015) and blunt use (Cooper & Haney, 2009; Soldz et al., 2003), estimates were stratified by gender.

Method

Participants

The NSDUH is an annual survey that is designed to provide quarterly and annual estimates of substance use and health status of civilian noninstitutionalized individuals ages 12 years and older in the United States. The sample includes household residents; residents of shelters, rooming houses, college dormitories, migratory workers’ camps, and halfway houses; and civilians residing on military bases. Individuals excluded from the sample are active military personnel, residents of institutional group quarters (e.g., prisons, nursing homes, mental institutions, long-term hospitals), and homeless persons. For the current study, we used 2013 NSDUH data from the 935 males (n = 543) and females (n = 392) who (a) self-identified as African American or Black and (b) reported smoking marijuana or hashish in the past 30 days.

Procedures

The NSDUH data collection method consisted of computer-assisted personal interviews and computer-assisted self-interviews in order to increase validity. Survey questions were displayed on a computer screen and read through headphones to all respondents, who then answered the questions directly on the computer. After the interview, participants were compensated $30 in cash. Details of the sampling strategy and data collection methods are described in the 2013 NSDUH report (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2013).

The current study used data from questions that focused on (a) demographic (i.e., age, education, employment status, income, marital status, county, lived in state where medical marijuana is legal, any marijuana use recommended by doctor in past 12 months, and overall health), (b) marijuana use (i.e., past-month blunt use, age at first marijuana use, days of past-month marijuana use, and past-year rates of marijuana abuse or dependence), and (c) other substance abuse characteristics (i.e., rates of mentholated cigarette use, rates of heavy alcohol use, illegal drug use other than marijuana).

To assess marijuana use, participants were asked the following question: “Sometimes people take some tobacco out of a cigar and replace it with marijuana. This is sometimes called a ‘blunt.’ How long has it been since you last smoked part or all of a cigar with marijuana in it?” Participants were asked to select one of the following options: (a) within the past 30 days, (b) more than 30 days ago but within the past 12 months, (c) more than 12 months ago, or (d) never used blunts. The responses to this item were used to create a new variable to assess past-month blunt use and past-month other marijuana use in the current study. Participants who endorsed “within the past 30 days” were categorized as past-month “blunt users” in the current study. Participants who endorsed blunt use “more than 30 days ago but within the past 12 months,” “more than 12 months ago,” or “never used blunts” were categorized as past-month “other marijuana users.”

Participants were also asked about their age at first marijuana use and days of past-month use. Individuals who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), criteria for marijuana abuse or dependence were categorized as having a marijuana abuse or dependence disorder in the past year.

Participants were also asked if they engaged in mentholated cigarette use, heavy alcohol use, or illegal drug use other than marijuana in the past 30 days (yes or no). Heavy alcohol use was defined as drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion (i.e., at the same time or within a couple hours of each other) on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days (SAMHSA, 2013).

Data analysis

To assess past-month prevalence rates (e.g., blunt users, other marijuana users), general descriptive statistics were conducted to determine the percentage of participants in each category. Logistic regression models were conducted to assess the relationship between independent variables (i.e., rates of mentholated cigarette use, marijuana abuse or dependence in the past year, heavy alcohol use, and illegal drug use other than marijuana) and marijuana consumption methods (blunt use vs. other marijuana use). Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to determine the differences between the continuous variables (i.e., age at first marijuana use, days of marijuana use in the past month) among blunt users and other marijuana users. The interaction effects of gender and the independent variables were also assessed in the logistic regression and ANOVA models. All analyses controlled for age. To control for multiple comparisons but allow for meaningful patterns to emerge from the data, significance level was set at .01 in each of the analyses. Weighted data were used to be representative of the U.S. population. Analyses were performed on IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 22; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Demographic characteristics of blunt users versus other marijuana users among past-month marijuana smokers

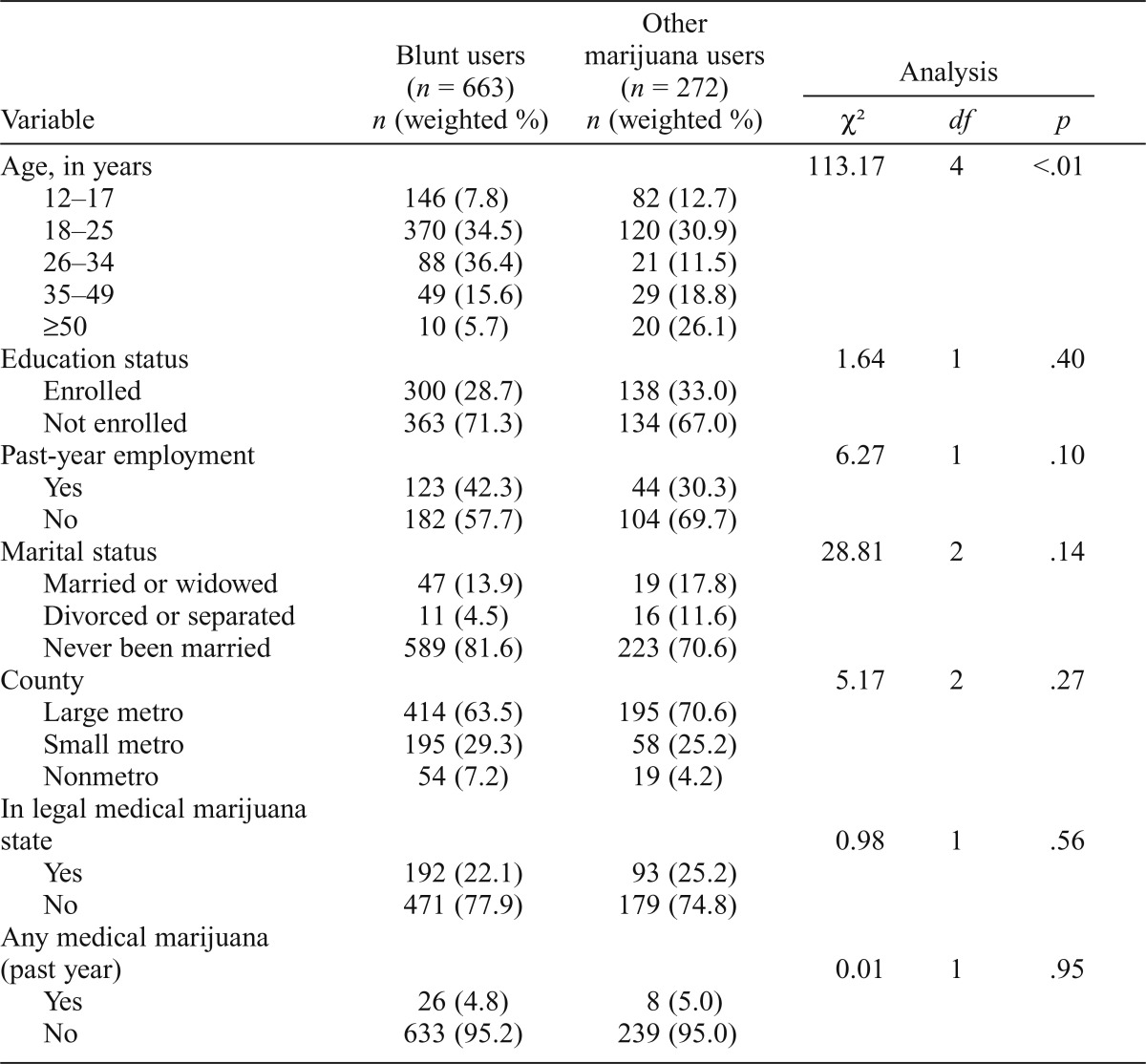

As shown in Table 1, 663 participants reported past-month blunt use, whereas only 272 reported other marijuana use. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics, with the exception of age. Rates of past-month blunt use were higher among 26- to 34-year-olds and rates of other marijuana use were highest among 18- to 25-year-olds relative to the other age groups. Subsequent analyses controlled for age. The frequency of past-month blunt use suggests that half of participants reported smoking a blunt at least 12 days in the past month. Specifically, 36.5%, 12.5%, 9.9%, 6.2%, 7.5%, and 28% of participants reported smoking blunts between 1 and 5, 6 and 10, 11 and 15, 16 and 20, 21 and 25, and 26 and 30 days in the past month, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Black past-month marijuana smokers

| Variable | Blunt users (n = 663) n (weighted %) | Other marijuana users (n = 272) n (weighted %) | Analysis |

||

| χ2 | df | P | |||

| Age, in years | 113.17 | 4 | <.01 | ||

| 12–17 | 146 (7.8) | 82 (12.7) | |||

| 18–25 | 370 (34.5) | 120 (30.9) | |||

| 26–34 | 88 (36.4) | 21 (11.5) | |||

| 35–49 | 49 (15.6) | 29 (18.8) | |||

| ≥50 | 10 (5.7) | 20 (26.1) | |||

| Education status | 1.64 | 1 | .40 | ||

| Enrolled | 300 (28.7) | 138 (33.0) | |||

| Not enrolled | 363 (71.3) | 134 (67.0) | |||

| Past-year employment | 6.27 | 1 | .10 | ||

| Yes | 123 (42.3) | 44 (30.3) | |||

| No | 182 (57.7) | 104 (69.7) | |||

| Marital status | 28.81 | 2 | .14 | ||

| Married or widowed | 47 (13.9) | 19 (17.8) | |||

| Divorced or separated | 11 (4.5) | 16 (11.6) | |||

| Never been married | 589 (81.6) | 223 (70.6) | |||

| County | 5.17 | 2 | .27 | ||

| Large metro | 414 (63.5) | 195 (70.6) | |||

| Small metro | 195 (29.3) | 58 (25.2) | |||

| Nonmetro | 54 (7.2) | 19 (4.2) | |||

| In legal medical marijuana state | 0.98 | 1 | .56 | ||

| Yes | 192 (22.1) | 93 (25.2) | |||

| No | 471 (77.9) | 179 (74.8) | |||

| Any medical marijuana (past year) | 0.01 | 1 | .95 | ||

| Yes | 26 (4.8) | 8 (5.0) | |||

| No | 633 (95.2) | 239 (95.0) | |||

Prevalence of blunt use versus other marijuana use among past-month marijuana smokers

Regarding the first research question, among past-month marijuana smokers (n = 935), 73.2% were blunt users and 26.8% were other marijuana users. Among male marijuana smokers (n = 543), 73.3% were blunt users and 26.7% were other marijuana users. Among female marijuana smokers (n = 392), 73.0% were blunt users and 27.0% were other marijuana users.

Marijuana and other substance use characteristics among past-month marijuana smokers

Overall, blunt users (M [SD] = 15.88 [3.42] years) reported initiating marijuana use at an earlier age than other marijuana users (17.29 [5.99] years) (p < .01). There was also a significant interaction between gender and marijuana consumption methods on age at first marijuana use (p < .01). Among males, blunt users (M [SD] = 15.3 [3.3] years) initiated marijuana use earlier than their other marijuana user counterparts (18.0 [7.3] years). However, among females, blunt users (M [SD] = 16.9 [3.4] years) and other marijuana users (16.2 [2.8] years) initiated marijuana use around the same age.

Blunt users (M [SD] = 15.96 [11.39] days) reported more days of past-month marijuana use than other marijuana users (7.99 [9.46] days), p < .01. This pattern was also found among both males and females (p < .01). Among males, blunt users (M [SD] = 14.4 [11.7]) reported more days of past-month marijuana use than other marijuana users (7.3 [9.4]). Among females, blunt users also reported more days of past-month marijuana use (M [SD] = 17.0 [11.1]) than other marijuana users (8.4 [9.4]).

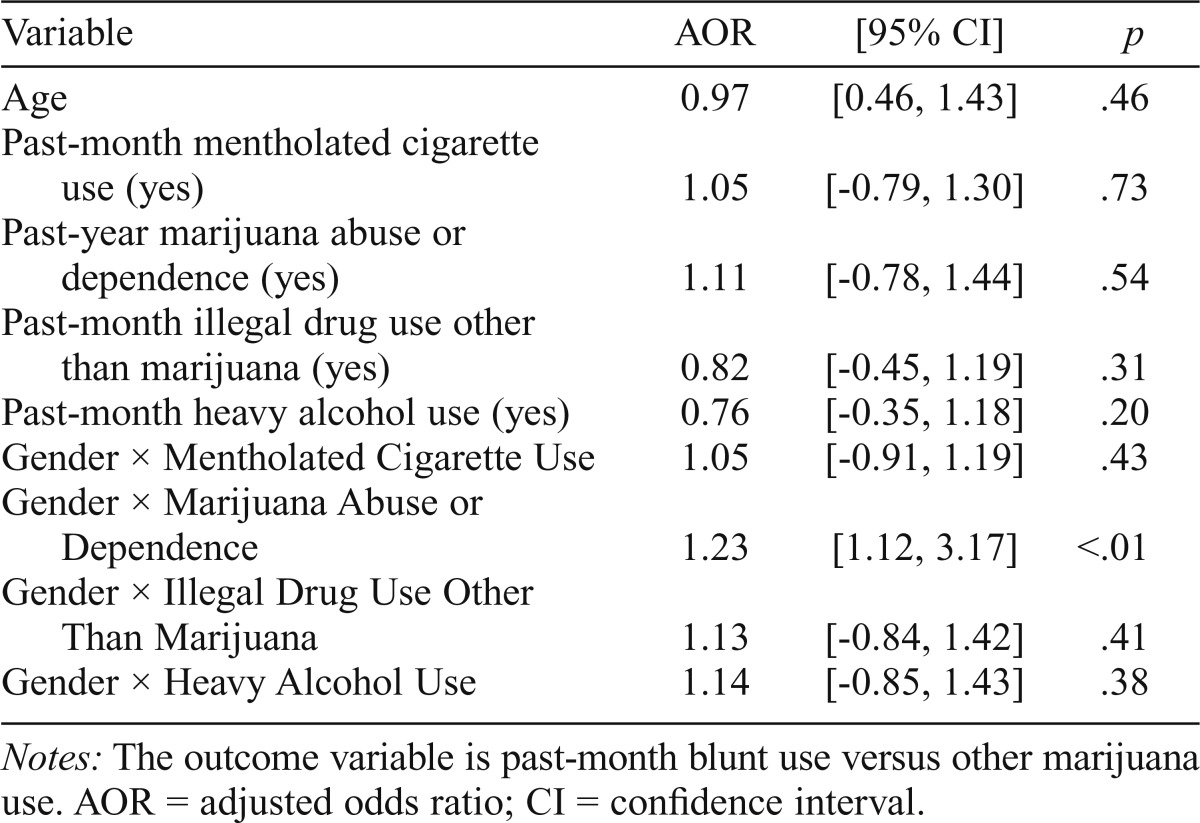

Table 2 displays results from the logistic regression models. Age was included in the model and was not a significant predictor of past-month blunt use relative to other marijuana use. Regarding the second research question, analyses revealed that blunt (87.3%) and other marijuana users (80.6%) reported similar odds of past-month mentholated cigarette use. This pattern was also observed among both males (93.4 vs. 86.3%) and females (84.0 vs. 76.8%) who reported blunt use versus other marijuana use, respectively.

Table 2.

Predictors of past-month blunt use among Black past-month marijuana smokers

| Variable | AOR | [95% CI] | p |

| Age | 0.97 | [0.46, 1.43] | .46 |

| Past-month mentholated cigarette use (yes) | 1.05 | [-0.79, 1.30] | .73 |

| Past-year marijuana abuse or dependence (yes) | 1.11 | [-0.78, 1.44] | .54 |

| Past-month illegal drug use other than marijuana (yes) | 0.82 | [-0.45, 1.19] | .31 |

| Past-month heavy alcohol use (yes) | 0.76 | [-0.35, 1.18] | .20 |

| Gender × Mentholated Cigarette Use | 1.05 | [-0.91, 1.19] | .43 |

| Gender × Marijuana Abuse or Dependence | 1.23 | [1.12, 3.17] | <.01 |

| Gender × Illegal Drug Use Other Than Marijuana | 1.13 | [-0.84, 1.42] | .41 |

| Gender × Heavy Alcohol Use | 1.14 | [-0.85, 1.43] | .38 |

Notes: The outcome variable is past-month blunt use versus other marijuana use. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Logistic regression analyses also revealed that blunt users (24.7%) and other marijuana users (19.7%) reported similar odds of marijuana abuse or dependence overall. However, as shown in Table 2, there was a significant interaction between gender and past-year marijuana abuse or dependence. Specifically, female blunt users (23.8%) were more likely to report past-year marijuana abuse or dependence than their other marijuana-using (11.3%) counterparts (p < .01). However, among males, the odds of past-year marijuana abuse or dependence among blunt users (25.3%) and other users (25.3%) were similar.

Blunt users (22.3%) and other marijuana users (13.9%) reported similar odds of heavy alcohol use. As shown in Table 2, there were also no significant gender differences found in the odds of heavy alcohol use among blunt users and other marijuana users. Specifically, males (28.4 vs. 21.9%) and females (12.9 vs. 14.0%) who reported blunt use versus other marijuana use reported similar odds of heavy alcohol use, respectively.

Blunt users (17.0%) and other marijuana users (14.4%) reported similar odds of illegal drug use other than marijuana. There were no significant gender differences in the odds of illegal drug use other than marijuana among blunt and other marijuana users, as shown in Table 2. Specifically, males (20.9 vs. 14.5%) and females (11.0 vs. 14.3%) who reported blunt use versus other marijuana use reported similar odds of illegal drug use other than marijuana, respectively.

Discussion

The current study was designed to examine if prevalence and patterns of substance use differ among Black blunt users and users who consume marijuana through other methods (e.g., joints). Findings revealed several differences in drug use characteristics (e.g., age at first marijuana use, marijuana abuse or dependence) between blunt users and other marijuana users. This study also found gender differences in blunt users versus other marijuana users.

The high prevalence of blunt use among Black adolescents and adults found in this study is consistent with existing literature (Mariani et al., 2011; Montgomery, 2015; Ramo et al., 2012). One plausible explanation for the high prevalence of blunt use is the belief that blunts are less harmful or addictive than other products. For example, in an oral, face-to-face interview-administered survey among rural young adult men, blunt smokers reported believing that their product was safer than cigarettes because they are more natural and less addictive (Sinclair et al., 2013). Very few studies or antismoking campaigns specifically address the health effects of blunt use (Sinclair et al., 2013). The lack of available knowledge about blunt use is a barrier to the dissemination of accurate health information and to the development of effective prevention and treatment interventions.

Compared with other marijuana users, blunt users reported initiating marijuana use at an earlier age and reported more days of past-month marijuana use. Black adolescents and adults are more likely than those in other racial groups to report influence of community norms and perceptions and culture on substance use behaviors (Luther et al., 2006). As blunt use is associated with Black youth, the drive for cultural identification and community belonging may contribute to early initiation of blunt use among Blacks as opposed to other modes of marijuana use. Further, Blacks report lower perceptions of harm of blunt use (Sinclair et al., 2013), which has been linked to greater frequency of substance use (Heinz et al., 2013).

Black females who smoked blunts were more likely to report marijuana abuse or dependence than their counterparts who consumed marijuana through other methods. Blunt users are more likely to be dependent on marijuana than non–blunt marijuana users (Timberlake, 2009). This may be because of compensatory smoking patterns established by blunt users such that they increase consumption (number and depth of inhalations, number of blunts smoked, and frequency of use) to obtain the same or similar effects of smoking marijuana alone.

In addition, there is evidence that Black females may have a greater number of risk factors for later substance use than their male counterparts (Friedman et al., 1995). Further, females, as compared with males, have been shown to progress more rapidly from initiation of marijuana use to regular use (Schepis et al., 2011), progress to their first symptom of substance dependence faster (Thorner et al., 2007), and demonstrate a quicker progression to a dependent pattern of substance use, which likely contributes to greater rates of dependence among females.

Although studies have acknowledged that blunt use is associated with an increased risk of marijuana-related problems (Fairman, 2015), this study adds to the literature by showing that among Blacks, the increased risk of marijuana abuse or dependence is largely found among females. It is also important to note that among past-month marijuana smokers, females reported using blunts at a slightly higher rate than males (17 vs. 14 days). A few of the existing studies on blunt use among Blacks have focused on men (Sinclair et al., 2012, 2013). Findings from the current study suggest that future studies on blunt smoking among Blacks should include both males and females, and the findings should be stratified by gender.

This study has several strengths, including the use of national survey data, the focus on blunt use relative to other consumption methods of marijuana, and an examination of gender differences in blunt use among Blacks. However, a few limitations should be noted. The NSDUH does not explicitly ask about other marijuana consumption methods (e.g., joints and pipes). Therefore, the exact consumption method(s) of each participant in the other category is unknown. Further, it is also plausible that blunt users also consumed marijuana via other methods (e.g., joints) in the past month. Moreover, the “blunt use” and “other marijuana use” categories do not consider the frequency of use and therefore represent a wide range of users (e.g., a participant who smoked 1 blunt vs. 30 blunts in the past month). Last, this study did not include homeless individuals and institutionalized populations that have high rates of substance use disorders and other psychiatric comorbidities. The results may not generalize to these marginalized populations. Future research should address these limitations.

Despite these limitations, this study has several implications for clinical practice and research. First, findings from this study suggest that additional research is needed on blunt use among Blacks. Approximately 73% of past-month marijuana smokers reported smoking marijuana through blunts. Further, important differences were found between blunt users and other marijuana users (e.g., more days of past-month marijuana use among blunt smokers), suggesting that clinicians and researchers should consider the consumption method when assessing and treating Black marijuana smokers. Also, as research shows that blunt users are also more likely to be nicotine dependent than their non–blunt marijuana using counterparts (Timberlake, 2009), blunt use interventions should also address potential nicotine dependence to increase success rates of marijuana cessation

In addition, the high rates of blunt use were coupled with higher rates of past-year marijuana abuse or dependence among Black females who smoked blunts. This highlights the need for more targeted cessation interventions for females, with higher levels of support during treatment, as those who demonstrate substance dependence have lower rates of successful cessation.

Previous studies have emphasized the higher rates of marijuana use especially through the use of blunts among men as compared with women (Sinclair et al., 2012), but this study supports the need for additional research on marijuana use among Black females. Although we postulate here the relationship between increased rates of blunt use and marijuana dependence among Black females, additional research is needed to understand the mechanism by which this relationship occurs. Given the high rates of blunt use among Black marijuana smokers, more research is needed to inform effective interventions to prevent and treat blunt use, especially in light of several laws and policies promoting marijuana legalization across the United States.

Footnotes

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Award Number R25DA035163. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Agrawal A., Budney A. J., Lynskey M. T. The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: A review. Addiction. 2012;107:1221–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Azagba S., Sharaf M. F. Binge drinking and marijuana use among menthol and non-menthol adolescent smokers: Findings from the youth smoking survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:740–743. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.005. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buu A., Dabrowska A., Heinze J. E., Hsieh H. F., Zimmerman M. A. Gender differences in the developmental trajectories of multiple substance use and the effect of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking in a high-risk sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;50:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.015. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Lyass A., Massaro J. M., O’Connor G. T., Keaney J. F., Jr., Vasan R. S. Exhaled carbon monoxide and risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease in the community. Circulation. 2010;122:1470–1477. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.941013. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.941013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Z. D., Haney M. Comparison of subjective, pharmacokinetic, and physiological effects of marijuana smoked as joints and blunts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.023. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairman B. J. Cannabis problem experiences among users of the tobacco-cannabis combination known as blunts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;150:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.014. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman T. P., Morgan C. J., Hindocha C., Schafer G., Das R. K., Curran H. V. Just say ‘know’: How do cannabinoid concentrations influence users’ estimates of cannabis potency and the amount they roll in joints? Addiction. 2014;109:1686–1694. doi: 10.1111/add.12634. doi:10.1111/add.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A. S., Granick S., Bransfield S., Kreisher C., Khalsa J. Gender differences in early life risk factors for substance use/abuse: A study of an African-American sample. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21:511–531. doi: 10.3109/00952999509002713. doi:10.3109/00952999509002713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A., Johnson B. D., Dunlap E. The growth in marijuana use among American youths during the 1990s and the extent of blunt smoking. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2006;4:1–21. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n03_01. doi:10.1300/J233v04n03_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W., Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374:1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A. J., Giedgowd G. E., Crane N. A., Veilleux J. C., Conrad M., Braun A. R., Kassel J. D. A comprehensive examination of hookah smoking in college students: Use patterns and contexts, social norms and attitudes, harm perception, psychological correlates and co-occurring substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:2751–2760. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.07.009. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte C., Vaillant-Roussel H., Pereira B., Blanc O., Tanguy G., Frappé P., Vorilhon P. CANABIC: CANnabis and Adolescents: Effect of a Brief Intervention on their Consumption—study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:40. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-40. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther E. J., Bagot K. S., Franken F. H., Moolchan E. T. Reasons for wanting to quit: Ethnic differences among cessation-seeking adolescent smokers. Ethnicity & Disease. 2006;16:739–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani J. J., Brooks D., Haney M., Levin F. R. Quantification and comparison of marijuana smoking practices: Blunts, joints, and pipes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113:249–251. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.008. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery L. Marijuana and tobacco use and co-use among African Americans: Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;51:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.046. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery L., Oluwoye O. The truth about marijuana use is all rolled up in a blunt: Prevalence and predictors of blunt use among young African-American adults. Journal of Substance Use. 2015 Advance online publication. doi:10.3109/14659891.2015.1037365. [Google Scholar]

- Moolchan E. T., Zimmerman D., Sehnert S. S., Zimmerman D., Huestis M. A., Epstein D. H. Recent marijuana blunt smoking impacts carbon monoxide as a measure of adolescent tobacco abstinence. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40:231–240. doi: 10.1081/ja-200048461. doi:10.1081/JA-200048461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo D. E., Liu H., Prochaska J. J. Tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of their co-use. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.002. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream G. L., Benoit E., Johnson B. D., Dunlap E. Smoking tobacco along with marijuana increases symptoms of cannabis dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.011. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream G. L., Johnson B. D., Sifaneck S. J., Dunlap E. Distinguishing blunts users from joints users: A comparison of marijuana use subcultures. In: Cole S. M., editor. New research on street drugs. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2006. pp. 245–273. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer G. L., Berg C. J., Kegler M. C., Donovan D. M., Windle M. Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: Trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003-2012. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;49:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.012. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis T. S., Desai R. A., Cavallo D. A., Smith A. E., McFetridge A., Liss T. B., Krishnan-Sarin S. Gender differences in adolescent marijuana use and associated psychosocial characteristics. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2011;5:65–73. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d8dc62. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d8dc62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifaneck S. J., Johnson B. D., Dunlap E. Cigars-for-blunts: Choice of tobacco products by blunt smokers. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2006;4:23–42. doi: 10.1300/J233v04n03_02. doi:10.1300/J233v04n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair C. F., Foushee H. R., Pevear J. S., III, Scarinci I. C., Carroll W. R. Patterns of blunt use among rural young adult African-American men. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.023. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair C. F., Foushee H. R., Scarinci I., Carroll W. R. Perceptions of harm to health from cigarettes, blunts, and marijuana among young adult African American men. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2013;24:1266–1275. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0126. doi:10.1353/hpu.2013.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldz S., Huyser D. J., Dorsey E. Youth preferences for cigar brands: Rates of use and characteristics of users. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:155–160. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.155. doi:10.1136/tc.12.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4795. 2013 Retrieved from www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/NationalFindings/NSDUHresults2012.htm#AppA.

- Thorner E. D., Jaszyna-Gasior M., Epstein D. H., Moolchan E. T. Progression to daily smoking: Is there a gender difference among cessation treatment seekers? Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:829–835. doi: 10.1080/10826080701202486. doi:10.1080/10826080701202486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake D. S. A comparison of drug use and dependence between blunt smokers and other cannabis users. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:401–415. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347651. doi:10.1080/10826080802347651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake D. S. The changing demographic of blunts smokers across birth cohorts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;130:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.022. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall M. M., Poh E., Cerda M., Keyes K. M., Galea S., Hasin D. S. Adolescent marijuana use from 2002–2008: Higher in states with medical marijuana laws, cause still unclear. Annals of Epidemiology. 2011;9:714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.06.001. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]